The Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2023-24 Annual Performance Report was released late Thursday August 1st and records a total of 255 marine animals were caught in the SMP during the 2023/24 meshing season, comprised of 15 target sharks and 240 non-target animals. Ninety-two animals (36%) were released alive.

The 15 target sharks comprised 12 White Sharks and 3 Tiger Sharks.

The 240 interactions with non-target animals consisted of:

- 109 non-target sharks, including 57 Smooth Hammerhead Sharks; 14 Greynurse Sharks; 11 Dusky Whaler Sharks; 10 Bronze Whaler Sharks*; 3 Great Hammerhead Sharks; 3 Broadnose Sevengill Sharks*; 3 Common Blacktip Sharks*; 3 Shortfin Mako Sharks*; 2 Silky Sharks*; and 1 of each of Australian Angel Shark, Spinner Shark*, and an unidentified hammerhead shark (* reported as target sharks prior to 2017).

- 90 rays, including 52 Southern Eagle Rays; 33 Australian Cownose Rays; 4 Smooth Stingrays, and a White Spotted Eagle Ray.

- 29 marine reptiles comprised of: 11 Leatherback Turtles; 3 Loggerhead Turtles; 13 Green Turtles; 1 Hawksbill Turtle; and 1 Olive Ridley Turtle.

- 7 marine mammals comprised of: 5 Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins; 1 Common Dolphin; and 1 Humpback Whale; and

- 5 interactions with finfish (Australian Bonito, Longtail Tuna, and Mulloway).

56 (22%) of the interactions were with threatened species comprised of: 14 Greynurse Sharks; 13 Green Turtles; 12 White Sharks; 11 Leatherback Turtles; 3 Loggerhead Turtles; and 3 Great Hammerhead Sharks.

Nine (3.5%) of the interactions were with protected species comprised of: 5 Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins; 1 Humpback Whale; 1 Common Dolphin; 1 Olive Ridley Turtle; and 1 Hawksbill Turtle.

Those listed under 'Sydney North'- our region, and which now omits for the first time where, specifically, each animals died - records 44 non-target species were caught in local nets:

- White Shark 1

- Bronze Whaler 2

- Dusky Whaler 2

- Smooth Hammerhead Shark 10 - 56 of the 57 caught in all nets were found dead. 26 were caught in the nets at Central Coast north and 17 at Central Coast south.

- Greynurse Shark 3. 6 of the 14 caught died. 157 of these species have been caught in the nets dating from the 2013/14 program onwards according to the report (Threatened species entanglements for 2013/14 to 2023/24 - page 30.)

- Southern Eagle Ray 4

- Australian Cownose Ray 15 - the highest amount caught in any of the nets

- Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin - 3 - 4 out of he 5 caught in all nets were found dead

- Green Turtle - 1. 8 of the 13 caught died.

- Leatherback Turtle - 2. 5 of the 11 caught overall were found dead.

- Longtail Tuna - 1

Aerial surveys Summer 23/24 - northern beaches

- 1403 flights - 394.33 hours - sharks seen: 3

Aerial surveys Autumn 2024 - northern beaches

- 955 flights - 300.68 hours - sharks seen:1

There were eleven reports of nets being damaged during the 2023/24 season, all of them in the Central Coast and Sydney North region, all of them mentioning suspected whale damage as these are in place when whales beginning their southern migration to Antarctica waters, often with calves alongside mums. Details of the where and when of the eleven incidents are:

- 23 September 2023 – Central Coast North contractor and shark meshing observer reported a large hole in the nets at Caves and Catherine Hill Bay. Suspected whale damage on both nets due to size of the damage/hole and the mesh appearing to have been snapped. All ropes, floats and mesh recovered;

- 26 September 2023 – Sydney North contractor and shark meshing observer reported a large amount of damage to the net at Bilgola. All ropes, floats and mesh recovered. Suspected whale damage;

- 29 September 2023 – Sydney North contractor reported a large hole in the shark net at Warriewood. Mesh appeared to be torn so suspected to be from a large animal. All ropes and mesh recovered;

- 01 October 2023 – Sydney North contractor reported suspected whale damage to the shark net at Mona Vale. All ropes, floats and mesh recovered;

- 06 October 2023 – Sydney North contractor reported suspected whale damage to the shark net at Whale Beach. All ropes, floats and mesh recovered;

- 06 October 2023 – Central Coast North contractor reported suspected whale damage to the shark net at Soldiers beach. All ropes and mesh recovered;

- 08 October 2023 – Central Coast North contractor reported suspected whale damage to the shark net at Shelly beach. All ropes and mesh recovered;

- 11 October 2023 – Central Coast North contractor reported a large hole in the net at Caves beach. Suspected whale damage due to size of the hole and the mesh appearing to have been snapped. All ropes, floats and mesh recovered;

- 23 October 2023 – Sydney North contractor and shark meshing observer reported extensive damage to the shark net at Palm beach. Suspected whale damage due the amount of damage to the net. All ropes, floats and mesh recovered;

- 03 November 2023 – Sydney North contractor reported a large hole in the shark net at Warriewood; Suspected whale damage. All ropes, floats and mesh recovered;

- 17 March 2024 – Central Coast North contractor reported that the net at Shelly beach had the top and bottom hangers broken off at the southern end of the net. All parts of net retrieved but the damage would suggest something large went through the net.

* Contractors report ‘suspected whale damage’ to nets when it is obvious that the net mesh and/or ropes have been torn, snapped, or broken under strain, as opposed to being cut. These reports also coincide with the whale migration season.

The NSW Department of Primary Industries, which is in charge of the Shark Meshing Program in NSW, states;

'Shark meshing is undertaken along certain beaches in NSW for bather protection, unfortunately the nets used also catch non-targeted species, such as grey nurse shark and other threatened marine mammals. For this reason the shark meshing program is listed as a key threatening process.'

'The program involves using specially designed nets along 51 beaches from Newcastle to Wollongong, where the majority of people in NSW swim and surf. The nets do not stretch from one end of a beach to the other. They are not designed to create a total barrier between bathers and sharks they are designed to deter sharks from establishing territories, thereby reducing the odds of a shark encounter.'

On Wednesday July 31 the NSW Government announced it will 'continue to prioritise the safety of beach goers this summer, while increasing protections for marine life, with the release of the state’s 2024-25 Shark Management Program'.

'Over the 2024-25 season the Government will work to ensure the Shark Management Program is striking the right balance and meeting community expectations.' the government stated

The Government will further engage with local councils on shark management with a focus on the future use of shark nets, and the exploration of local decision making on the removal or use of nets, it was stated.

In April 2021 the Council called on the NSW government to remove shark nets on beaches in the Northern Beaches Council area and replace them with a combination of modern and effective alternative shark mitigation strategies that maintain or improve swimmer safety and reduce unwanted by-catch of non-target species.

Council made the call in response to Department of Primary Industries – Fisheries (DPI Fisheries) request for input from stakeholders on their preferred shark mitigation measures, following a five-year project considering the benefits and impacts of a range of mitigation measures.

A number of residents addressed Council’s meeting in support of shark net removal, including surfing champion Layne Beachley.

Cr. Bingham said Council considered both the need to maintain or improve swimmer safety as well as the negative impacts on non-target marine species in reaching their decision.

“The effectiveness of shark nets has been questioned by many, yet their impact on other marine species is devastating,” Cr Bingham said.

“We have an aquatic reserve in Manly where turtles and rays are regularly seen by snorkelers, and up and down the beaches dolphins surf the waves alongside local board riders.

“The research conducted by DPI Fisheries found that 90% of marine species caught in nets were non-target species and that sharks can in fact swim over, under and around the nets anyhow.

“If the evidence is that there are other just as, or more, effective ways to mitigate shark risk, such as drone and helicopter surveillance, listening stations and deterrent devices, then we owe it to those non-target species to remove the nets.

‘We will be providing that feedback through this consultation process and look forward to the government implementing effective shark mitigation measures while protecting other important marine species.

The 2024-2025 (SMP) Shark Meshing Program includes a suite of new measures to be trialled, which the government states will increase protections for marine life whilst shark nets remain in use, including:

- Removing shark nets one month earlier, on 31 March 2025, to respond to increased turtle activity in April.

- Increasing the frequency of net inspections by contractors during March from every 3rd day to every 2nd day.

- SLS drone surveillance increased over nets during March to scout for turtles on the days contractors aren’t inspecting

- Trial of lights on nets to deter turtles and prevent their entanglement during February and March.

Shark nets across NSW are also fitted with acoustic warning devices, such as dolphin pingers and whale alarms, to deter and minimise the risks to those marine mammals.

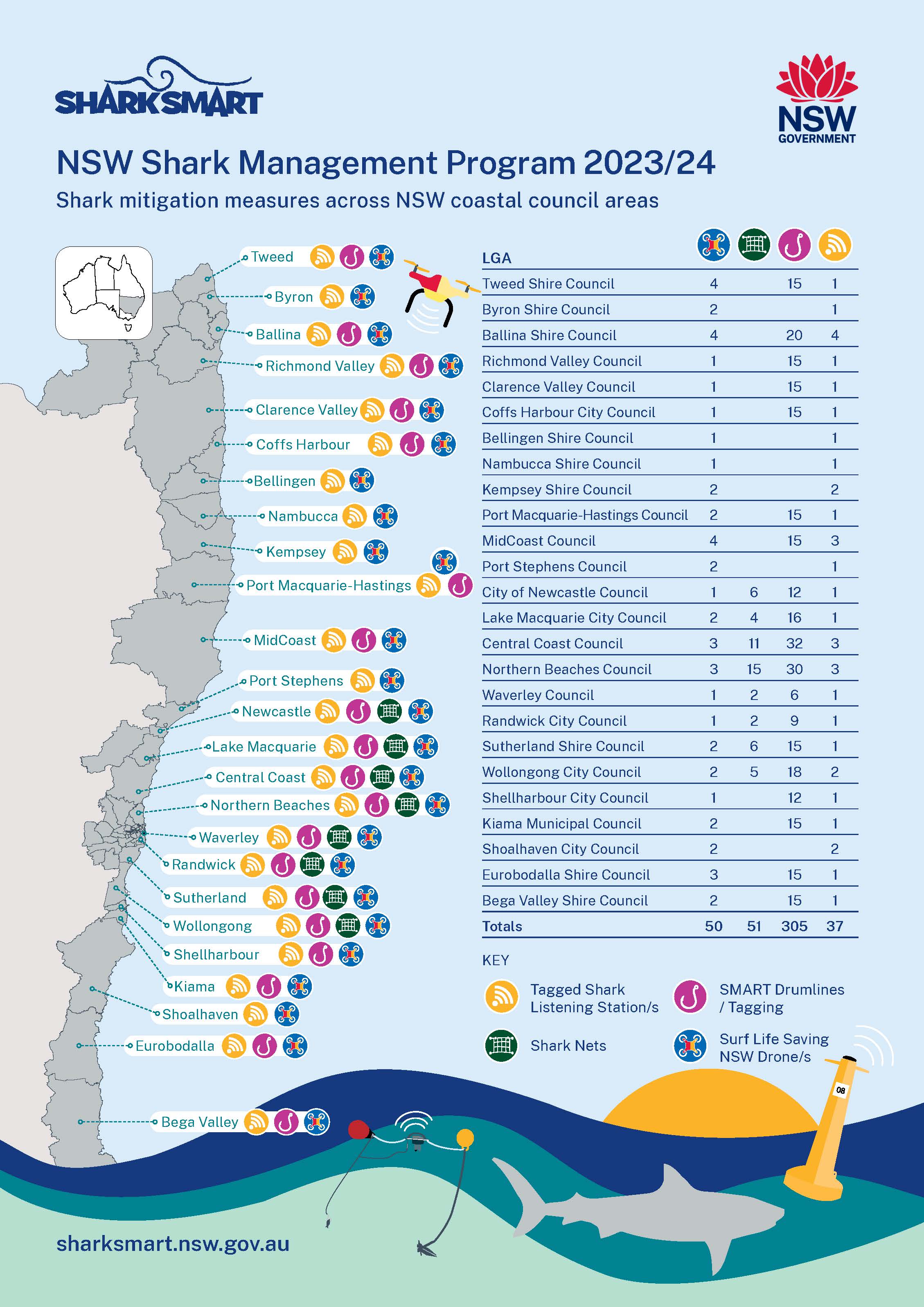

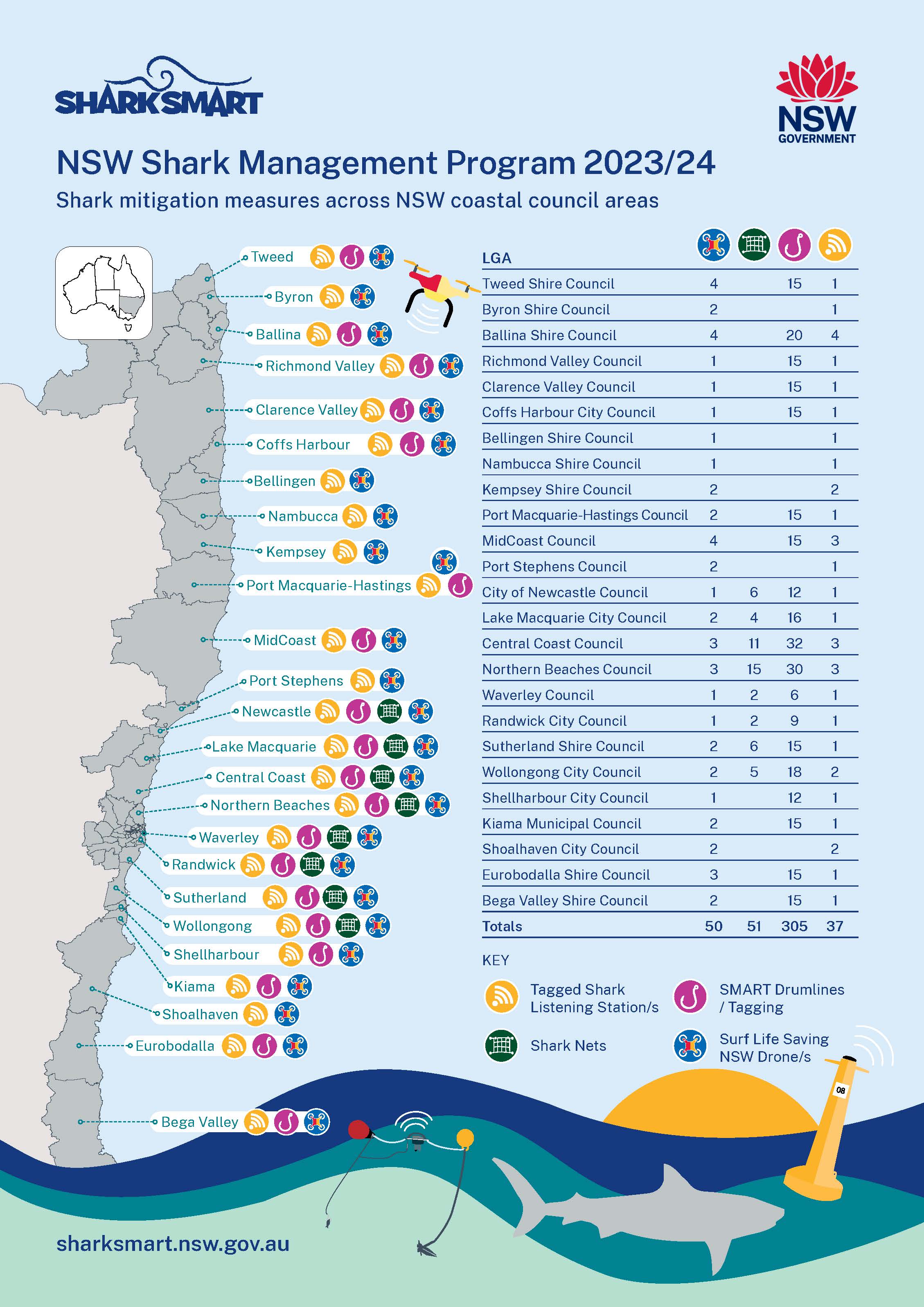

The $21.5 million Shark Management Program for 2024-25 is designed to protect the safety of beach users from the across 25 local government areas from Tweed to Bega, by reducing interactions with sharks, whilst minimising the impact on other marine life.

A range of techniques will be used in 2024-25 to achieve this objective, such as:

- Drone surveillance program using 50 drones, partnering with Surf Life Saving NSW

- 37 tagged shark listening stations, all year round along the NSW coast

- 305 SMART (Shark-Management-Alert-in-Real-Time) drumlines across 19 LGAs, all year

- Shark nets at 51 beaches across eight LGAs, 1 September 2024 to 31 March 25

- Funding Surfing NSW $500,000 to provide mitigation support and services including trauma response kits, drones and training

- SharkSmart community education program, including shark and social research.

Over the 2023-24 season 400 drone pilots for Surf Life Saving NSW were trained, who flew more than 36,000 flights across nearly 10,000 hours. Through this use of drones 362 sharks were observed.

SMART drumlines have also been used as an effective tool to keep swimmers safe on New South Wales Beaches, allowing over 413 target sharks such as white, tiger and bull sharks, to be caught, tagged and released last year, the government states.

Once tagged, the state’s 37 coastal tagged shark listening stations can track these sharks near the beaches where the device is based – with this information available to anyone with the SharkSmart app, website of on X (Twitter).

Over 2,000 target sharks have been tagged over the 12-year life of the program, the government stated, and are monitored by listening stations.

For more information visit www.sharksmart.nsw.gov.au

Minister for Agriculture Tara Moriarty said:

“The NSW Government’s priority is the safety of beach goers, at the same time we are committed to protecting our states marine life.

“We will be working closely with local governments, SLSNSW and Surfing NSW over this season to ensure the future of this program works for the communities it operates in.

“Importantly, this year we have responded to community feedback and taken significant steps to increase the program’s safeguards for marine animals.

“As we map the future of this program we will listen to local communities, and consider the best available evidence to ensure we are striking the right balance at our beaches.”

However, the non-targeted species impacted remains a problem for numerous animal welfare and conservation groups and locals.

Valerie Taylor AM, then 88, and Bailey Mason, the not yet 20, attended the Shark Nets Out Now protest at Manly on Saturday December 3rd, 2022. Photo supplied.

Valerie Taylor AM, then 88, and Bailey Mason, the not yet 20, attended the Shark Nets Out Now protest at Manly on Saturday December 3rd, 2022. Photo supplied.

In a statement released the same day the RSPCA NSW said:

Shark Nets in NSW: Time for Humane and Effective Alternatives

Shark nets are installed at 51 beaches between Newcastle and Wollongong annually from September to April. The nets are removed between May to August to allow for the [northern] migration of whales.

Their effectiveness in successful shark management has been scientifically disproven. They not only pose a danger to sharks, a species under great threat, but also to a multitude of other marine life and even the swimmers and surfers they are intended to protect.

In the SMP 22/23, 90% of the marine life caught in shark nets in NSW were non-target animals. This means that 204 harmless sharks, rays, turtles, dolphins, and seals were trapped, injured or killed.

RSPCA NSW fully supports the NSW Government’s election commitment to phasing out this archaic and cruel program and welcomes this change as soon as possible.

The Shark Meshing Program (SMP) in NSW was established in the 1930s as a response to increasing concerns about shark incidents along the state’s coastline. The program aimed to protect beachgoers and reduce the risk of shark encounters by reducing shark populations through the use of nets along selected beaches.

SMP involves the installation of mesh nets approximately 150 meters in length, extending 6m high from the ocean floor. The nets are designed to catch and kill sharks swimming near popular beaches, therefore reducing the shark population and in turn attempting to reduce the risk of a shark bite incident.

Despite positive public perception, scientific evidence and expert advice show that the SMP negatively impacts, and is an ongoing threat to, marine animals and the marine environment. There is no scientific evidence that supports the SMP as an effective strategy to keep beachgoers, swimmers, and surfers safe – with 80% of shark encounters in Sydney occurring at netted beaches.

Humane and effective alternatives for shark management

RSPCA NSW supports the implementation of justified, humane and effective methods to prevent shark incidents. When evaluating potential mitigation methods, welfare aspects relating to target and non-target species must be considered in addition to environmental assessment.

It is recommended that non-lethal methods informed by an understanding of shark biology, behaviour, and ecology be further developed and implemented, including (but not limited to) tagging and tracking alert systems, patrols and surveillance, active and passive electrical repellents, innovative sonar systems, and eco-barriers.

Shark mitigation strategies such as ‘shark spotting’ using beach surveillance and shark awareness programs that educate the public about risk factors that can potentially influence the likelihood of being attacked by sharks also play an important role.

Beach pools are an excellent option for those seeking a safe ocean swimming environment that mitigates the risk of shark encounters. They provide a secure space for swimming while allowing beachgoers to enjoy the beauty and benefits of the ocean without the worry of interactions with sharks and other dangerous wildlife.

Shark nets are scheduled to be reinstalled in NSW on 1 September 2024.

RSPCA NSW supports a complete phase out of the Shark Meshing Program. The NSW Government’s recent Summer Shark Management Plan announcement is a step in the right direction, and we are eager to assist in whatever way we can to expedite this process.

Implementing this commitment will allow us to collectively protect and improve the welfare of all sea creatures, large and small, and ensure that public funds are used more effectively to keep our beaches safe and free from harm.

The Human Society International (Australia) and the Australian Marine Conservation Society said:

Today’s announcement by Minister for Agriculture, Tara Moriarty, to remove NSW shark nets one month earlier than usual and consult with local councils on permanent removal is a ‘positive step’ but not nearly enough and will still leave destructive nets in place for seven months.

Humane Society International Australia and the Australian Marine Conservation Society say the community has nothing to fear from the removal of the shark nets because they simply don’t work.

There is ample evidence that the modern shark mitigation technology—that is already in place at all of the netted beaches—is more effective at providing beach safety.

“While we welcome the announcement to shorten the meshing season, we can’t ignore the fact that the nets will still be in place for six months,” said Lawrence Chlebeck, marine biologist with Humane Society International (HSI) Australia.

“We strongly urge local councils and the Minns Government to work quickly on permanent removal of the ineffective shark nets. They know shark nets don’t stop shark bites, and they know nets are killing marine animals.”

“This decision is a positive step, and was made following consistent pressure regarding turtle migration, but turtles are just one of the threatened marine animals that end up in the nets every year.”

“Critically Endangered grey nurse sharks are dying in the nets in alarming numbers, hastening their extinction on the east coast. Six months is simply too long, and we stand by our call to have the nets removed completely and permanently,” he said.

“More frequent net-checks and improved drone surveillance are also positive, but the government is beating around the bush. Lights on nets will do nothing to reduce turtle catch and may even increase the risk to birds like Manly’s little penguins.”

Figures being released by the Department of Primary Industries (DPI) will show that 255 marine animals were caught in the NSW Shark Meshing Program (SMP) during the 2023/24 season.

Only 15 of them were the targeted species of great white, tiger, or bull shark.

Furthermore, almost one quarter (24 per cent) of the marine animals caught in the SMP were classified as a threatened or protected species, including a migrating humpback whale that became entangled in a shark net off Catherine Hill Bay in September.

“Every year we see the same story: a miniscule number of targeted sharks caught compared to an overwhelming number of other marine animals,” said Lawrence Chlebeck, a marine biologist with Humane Society International (HSI) Australia.

“The collateral damage caused by these nets is unbelievable: for every targeted shark caught last season, 17 other marine animals become entangled in the nets. Many of them were dead when found or would have died soon after, and what’s most upsetting is knowing just how many of those animals were threatened and protected species,” he said.

“When you start adding up the figures, year after year, it is horrifying to realise how many threatened animals are being taken out of the marine ecosystem by an ineffective government program, he said”

HSI Australia and the Australian Marine Conservation Society (AMCS) have long called for the nets to be removed permanently, citing the sheer inefficiency of the nets in capturing the targeted animals.

“The use of shark nets are redundant when for nearly a decade, successive NSW Governments have been using modern, evidence-based solutions including drones, community education programs, and the tagging and tracking of sharks,” said Dr Leonardo Guida, a shark scientist with AMCS.

“Successive NSW Governments have operated the world’s longest marine culling program for nearly 90 years and on 1 September, the Minns Government has the opportunity to retire the nets for good, and fully transition NSW beach safety to the modern era for the benefit of bathers and wildlife alike,” he said.

The figures released this year bring the total number of marine animals caught in the nets since 2012 to 4,121. Of those, 2,396 died – most were non-targeted marine animals.

“Since 2012, we’ve seen an average of more than 90 per cent of the marine animals caught being non-target species,” Chlebeck said.

“Yet every year, the government blindly ignores the data and puts the nets back in. And every year, those nets kill more and more marine animals and drive threatened and protected species closer to local extinction.”

“The proof is there: shark nets do not prevent shark attacks. There have been 35 bites at netted beaches. It is absolutely time the nets were removed permanently,” he said.

Catch statistics for NSW 2023/24

- 255 marine animals caught in NSW shark nets in 2023/24

- 163 (64%) were killed

- Only 15 targeted sharks (Great White, Tiger, Bull) were caught

- 62 marine animals (24%) were threatened or protected under the EPBC Act

- Those include

- 29 turtles (Endangered) were caught, 16 killed

- 14 grey nurse sharks (Critically Endangered), 6 killed

A migrating humpback whale was also entangled in the shark net off Catherine Hill Bay in September 2023 and a juvenile humpback caught in the Whale Beach net in October 2021.

However, communities are still calling for the an end to shark nets due to their impact on non-target endangered species, along with migrating whales. Others have stated the statistics recorded are not accurate.

See:

Minns Government’s weak move on shark nets means hundreds of threatened marine animals to be killed in NSW this summer: Greens

Premier Chris Minns’ announcement that shark nets will be taken out of the oceans just one month earlier is pathetic and weak and means hundreds of threatened marine animals will be killed once again in NSW waters this summer, says Greens NSW MP and Healthy Oceans spokesperson Cate Faehrmann.

Shark nets are currently placed annually along 51 beaches between Newcastle and Wollongong from 1 September to 30 April. The Premier has said today that they’ll now be removed at the end of March 2025 as a means of avoiding the leatherback turtle migration season.

The Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program 2023/24 Annual Performance Report is due to be released tomorrow and will show that yet again shark nets have caused irreversible harm to our marine species. Turtle deaths, as a result of being caught in nets, have increased.

Greens NSW spokesperson for Healthy Oceans, Cate Faehrmann stated:

“This announcement is an attempt to gloss over the fact that this government has totally failed to respond to community calls to remove shark nets for good," Cate Faehrmann MP said.

“It’s a weak and pathetic response to genuine community concern about just how much marine life these nets kill.

“Threatened species that cause no threat to human life are being caught in the nets at an alarming rate.

“It has just been revealed that last summer alone 13 green turtles, five bottlenose dolphins and one humpback whale were caught in shark nets off the NSW coast - and only 36 percent of all animals caught were released alive.

“21 out of 25 coastal councils have said that they do not want shark nets at all. They do not keep swimmers safe - sharks can swim under, over and around them.

“The government is also talking of shifting decision making for shark netting to local councils. This is just another example of a shirking of responsibility from a government too afraid to make difficult decisions.”

Greens spokesperson for Healthy Oceans, Senator Peter Whish-Wilson said:

“We know that shark nets are not effective at removing the risk of shark bites to humans and the community shares this view," Senator Whish-Wilson said.

“The NSW Government is cherry-picking community sentiment and completely ignoring the call for shark nets to be removed altogether.

“The Greens are pushing for the removal of federal exemptions that allow the use of shark nets to continue without proper environmental assessment under the EPBC Act.

“The upcoming review of Australia’s EPBC laws is an opportunity for the Labor Government to remove existing exemptions to state-controlled lethal shark net programs that risk federally protected species.

“These lethal shark nets and drumlines entangle and kill sharks, put other nationally threatened species at risk, and provide a false sense of security to ocean goers. It is long overdue that these outdated methods are assessed under our national environment laws."

![]()