The Australian authority that regulates pesticides has finally released its long-delayed review of the rodenticide poisons used by millions of Australians to combat rat and mice infestations.

As researchers who study Australia’s amazing native owls (and more recently, the rodenticide poisoning of wildlife), we were extremely hopeful about its findings. We thought this review would make world-leading recommendations that would protect wildlife and set the global standard for regulating these toxic compounds.

Instead, the recommendations from the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) leave Australians still reliant on rodent poisons that are responsible for most of the documented impacts on wildlife globally.

Why these poisons are a wildlife problem

Second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs) which include brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difethialone, difenacoum and flocoumafen, are the core problem. These extremely potent poisons prevent normal blood clotting processes and ultimately lead to death, often via uncontrollable internal bleeding.

When a rat or mouse eats a SGAR-based bait, the poison remains in its body for up to a year. This is how it ultimately passes to predators and scavengers such as owls, frogmouths, raptors, quolls and goannas that eat the poisoned animal.

These native animals die slowly and painfully. This process, known as secondary poisoning, is well documented in predators in Australia and globally.

What the review found

The review acknowledges the science and highlights the risks that SGARs pose, not only to our wildlife and fragile ecosystems but also potentially to humans.

However, despite the risks and advice from scientists to ban SGARs, the review proposes keeping SGARs as the primary tool for Australia’s war on rodents. It described them as an “unacceptable risk”, but stopped short of recommending a blanket ban.

The review argues SGARs remain essential for rodent control, especially with rodents developing some resistance to older poisons. The proposed changes focus on mitigating exposure risk to non-rodents. These include changes to labels and the way bait is delivered, and packaging controls. Under these changes, SGARs will remain widely available to the public.

Ultimately the real difficulty – not adequately addressed – is broader than simply preventing non-rodents from consuming baits. The real issue lies with the nature of the toxins themselves.

These poisons are highly effective at killing rodents, but they do not kill them quickly. After eating poisoned bait, a doomed “zombie” rodent will remain alive for several days, potentially up to a week. During this time, their behaviour changes. Normally cautious, these nocturnal animals become slower, disoriented and far more likely to be eaten by predators such as owls (or even your pet cat or dog).

Crucially, these poisoned “zombie” rodents can continue to eat more poisoned bait. By the time they die, they may contain very high concentrations of rodenticide.

Secondary poisoning is a predictable outcome

When a predator eats a poisoned rodent (or any other poisoned species), it also ingests its poison. This is unlikely to cause immediate death, but SGARs accumulate in the liver and remain there for up to a year. With repeated consumption of poisoned animals, the predator reaches a toxic threshold and dies.

Unfortunately, secondary poisoning is not an accidental or a misuse scenario. It is a highly predictable outcome of allowing the use of poisons in our ecosystems that accumulate in the body.

Paradoxically, the animals most affected by SGARs are the very species that help control mice and rat populations naturally. Predators such as owls breed more slowly than rodents. When rodenticides kill predators in urban and agricultural landscapes, rodent problems often worsen and spur further reliance on poisons. This creates a damaging feedback loop that Australia has been reinforcing for decades, one not addressed by the proposed changes.

Many researchers, including our colleagues and ourselves, argued during this review that meaningful reform requires either banning SGARs in Australia completely or severely restricting access so they are not available to the public. Other countries such as Switzerland and Canada have reached similar conclusions, and responded by significantly limiting access to these compounds with the intent of banning them.

Australia’s proposed changes move in the wrong direction, and leave us considerably behind much of the developed world. Australia will continue using rodenticides that cause the greatest harm, such as SGARs. And lower-risk alternatives that use the First Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticide (FGAR), such as Warfarin, face cancellation because they do not contain chemicals that make them bitter – an aspect to try and make them less attractive to non-rodent species.

Warfarin-based baits are safer as they do not accumulate in the body of poisoned animals to the same extent and they are expelled from the body more quickly, reducing the risk of secondary poisoning.

Restriction will protect wildlife

This review could have broken the cycle of poisoning native Australian predators in the name of rodent control. Instead, it preserves a system that does not work here, or anywhere else in the world.

If Australia is serious about protecting its wildlife while managing rodents effectively, it must confront the role of SGARs directly. Adjusting labels and packaging cannot solve a problem driven by the chemistry of the poisons themselves.

We simply must do better. Until access to these compounds is meaningfully restricted, secondary poisoning will remain an inevitable – and entirely preventable – outcome. Many native animals will continue to die slow and painful deaths.![]()

John White, Associate Professor in Wildlife and Conservation Biology, Deakin University and Raylene Cooke, Professor in wildlife and conservation biology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

%20smaller.jpg?timestamp=1770340203705)

This is not the same as when plants are named after the people who ‘discovered’ them. This ‘naming’ is in English and is a person paying tribute to a grower of roses for example ‘Mrs Partridge’s blue rose’ or a ‘Granny Smith’ which was named after a lady in Eastwood (now one of Sydney’s suburbs) called Maria Ann Smith who developed this yummy green apple by chance when a wild apple and a domestic one accidentally seeded a new apple. Every year now the granny smith apple is celebrated as the Granny Smith Festival and will be again this year on October 20th, 2013. See

This is not the same as when plants are named after the people who ‘discovered’ them. This ‘naming’ is in English and is a person paying tribute to a grower of roses for example ‘Mrs Partridge’s blue rose’ or a ‘Granny Smith’ which was named after a lady in Eastwood (now one of Sydney’s suburbs) called Maria Ann Smith who developed this yummy green apple by chance when a wild apple and a domestic one accidentally seeded a new apple. Every year now the granny smith apple is celebrated as the Granny Smith Festival and will be again this year on October 20th, 2013. See

crowns may help you to make up your own dance!

crowns may help you to make up your own dance!

(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

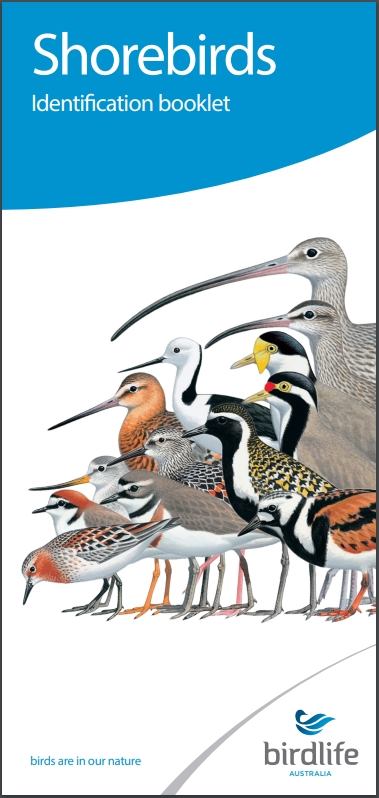

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Avalon Preservation Association, also known as Avalon Preservation Trust. We are a not for profit volunteer community group incorporated under the NSW Associations Act, established 50 years ago. We are committed to protecting your interests – to keeping guard over our natural and built environment throughout the Avalon area.

The Avalon Preservation Association, also known as Avalon Preservation Trust. We are a not for profit volunteer community group incorporated under the NSW Associations Act, established 50 years ago. We are committed to protecting your interests – to keeping guard over our natural and built environment throughout the Avalon area.

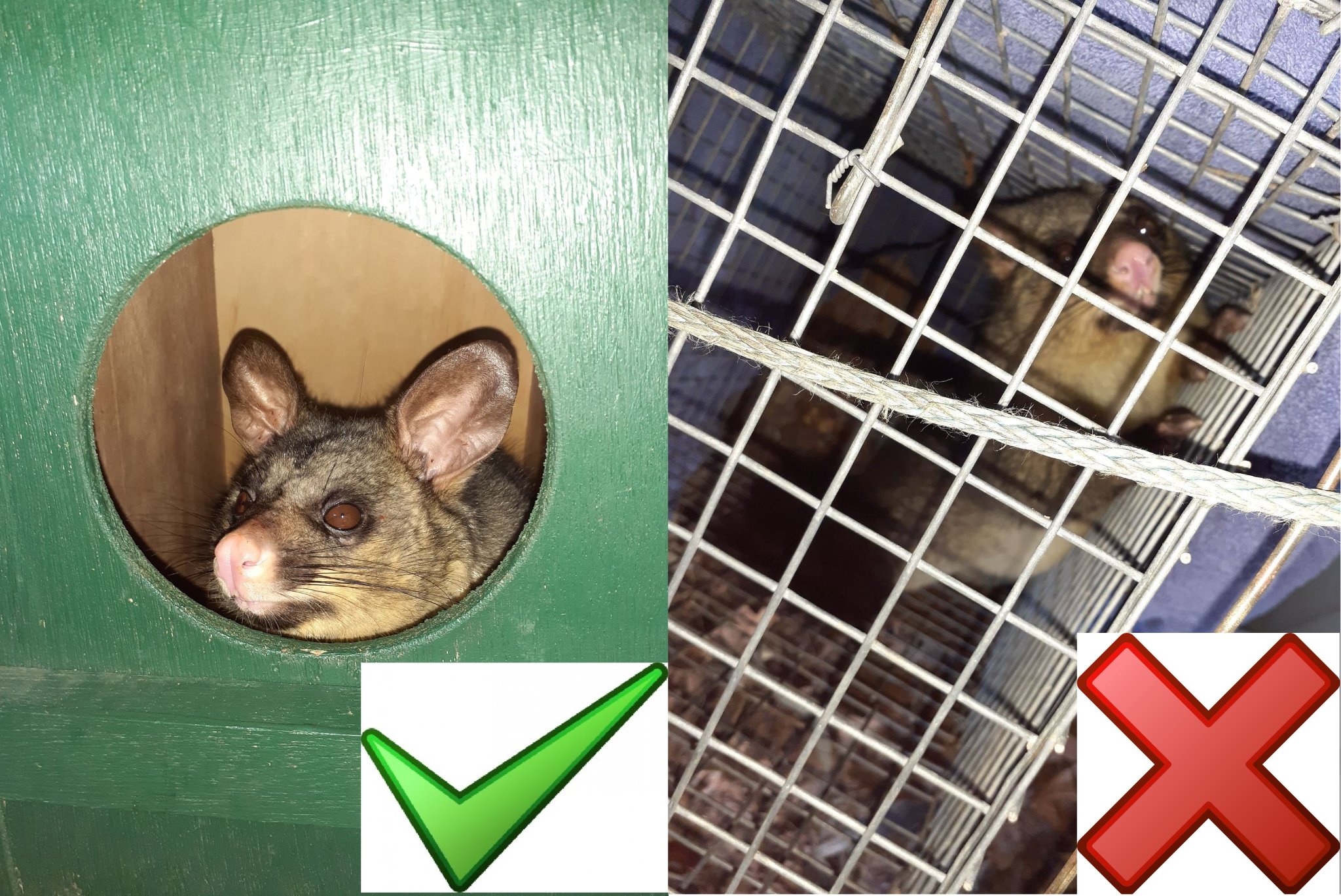

Sydney Wildlife rescues, rehabilitates and releases sick, injured and orphaned native wildlife. From penguins, to possums and parrots, native wildlife of all descriptions passes through the caring hands of Sydney Wildlife rescuers and carers on a daily basis. We provide a genuine 24 hour, 7 day per week emergency advice, rescue and care service.

Sydney Wildlife rescues, rehabilitates and releases sick, injured and orphaned native wildlife. From penguins, to possums and parrots, native wildlife of all descriptions passes through the caring hands of Sydney Wildlife rescuers and carers on a daily basis. We provide a genuine 24 hour, 7 day per week emergency advice, rescue and care service. Southern Cross Wildlife Care was launched over 6 years ago. It is the brainchild of Dr Howard Ralph, the founder and chief veterinarian. SCWC was established solely for the purpose of treating injured, sick and orphaned wildlife. No wild creature in need that passes through our doors is ever rejected.

Southern Cross Wildlife Care was launched over 6 years ago. It is the brainchild of Dr Howard Ralph, the founder and chief veterinarian. SCWC was established solely for the purpose of treating injured, sick and orphaned wildlife. No wild creature in need that passes through our doors is ever rejected.  Avalon Community Garden

Avalon Community Garden

Living Ocean was born in Whale Beach, on the Northern Beaches of Sydney, surrounded by water and set in an area of incredible beauty.

Living Ocean was born in Whale Beach, on the Northern Beaches of Sydney, surrounded by water and set in an area of incredible beauty.

Want to know where your food is coming from?

Want to know where your food is coming from?

Pittwater Environmental Foundation was established in 2006 to conserve and enhance the natural environment of the Pittwater local government area through the application of tax deductible donations, gifts and bequests. The Directors were appointed by Pittwater Council.

Pittwater Environmental Foundation was established in 2006 to conserve and enhance the natural environment of the Pittwater local government area through the application of tax deductible donations, gifts and bequests. The Directors were appointed by Pittwater Council.

"I bind myself today to the power of Heaven, the light of the sun, the brightness of the moon, the splendour of fire, the flashing of lightning, the swiftness of wind, the depth of the sea, the stability of the earth, the compactness of rocks." - from the Prayer of Saint Patrick

"I bind myself today to the power of Heaven, the light of the sun, the brightness of the moon, the splendour of fire, the flashing of lightning, the swiftness of wind, the depth of the sea, the stability of the earth, the compactness of rocks." - from the Prayer of Saint Patrick