In the 2024–25 financial year alone, the Australian Centre to Counter Child Exploitation received nearly 83,000 reports of online child sexual abuse material (CSAM), primarily on mainstream platforms. This was a 41% increase from the year before.

It is in this context of child abuse occurring in plain sight, on mainstream platforms, that the eSafety Commissioner, Julie Inman Grant, requires transparency notices every six months from Google, Apple, Microsoft, Meta and other big tech firms.

The latest report, published today, shows some progress in detecting known abuse material – including material that is generated by artificial intelligence (AI), live-streamed abuse, online grooming, and sexual extortion of children and adults – and reducing moderation times.

However, the report also reveals ongoing and serious safety gaps that still put users, especially children, at risk. It makes clear that transparency is not enough. Consistent with existing calls for a legally mandated Digital Duty of Care, we need to move from merely recording harms to preventing them through better design.

What the reports tell us

These transparency reports are important for companies to meet regulatory requirements.

But the new eSafety “snapshot” shows an ongoing gap between what technology can do and what companies are actually doing to tackle online harms.

One of the positive findings is that Snap, which owns SnapChat, has reduced its child sexual exploitation and abuse moderation response time from 90 minutes to 11 minutes.

Microsoft has also expanded its detection of known abuse material within Outlook.

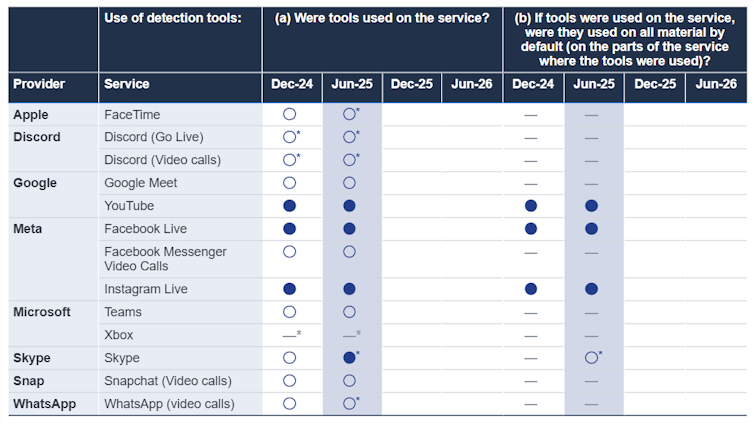

However, Meta and Google continue to leave video calling services such as Messenger and Google Meet unmonitored for live-streamed abuse. This is despite them using detection tools on their other platforms.

The eSafety report highlights that Apple and Discord are failing to implement proactive detection, with Apple relying almost entirely on user reports rather than automated safety technology.

Apple, Discord, Google’s Chat, Meet and Messages, Microsoft Teams, and Snap are not currently using available software to detect the sexual extortion of children.

The biggest areas of concern identified by the commissioner are live video and encrypted environments. There is still insufficient investment in tools to detect live online child sexual exploitation and abuse. Despite Skype (owned by Microsoft) historically implementing such protections before its closure, Microsoft Teams and other providers still fail to do so.

Alongside the report, eSafety launched a new dashboard that tracks the progress of technology companies.

The dashboard highlights key metrics. These include the technologies and data sources used to detect harmful content, the amount of content that is user reported (which indicates automated systems did not catch it), and the size of the trust and safety workforce within the companies.

How can we improve safety?

The ongoing gaps identified by the eSafety Commissioner show that current reporting requirements are insufficient to make platforms safe.

The industry should put safety before profit. But this rarely happens unless laws require it.

A legislated digital duty of care, as proposed by the review of the Online Safety Act, is part of the answer.

This would make tech companies legally responsible for showing their systems are safe by design before launch. Instead of waiting for reports to reveal long-standing safety gaps, a duty of care would require platforms to identify risks early and implement already available solutions, such as language analysis software and deterrence messaging.

Beyond detection: the need for safety

To stop people from sharing or accessing harmful and illegal material, we also need to focus on deterrence and encourage them to seek help.

This is a key focus of the CSAM Deterrence Centre, a collaboration between Jesuit Social Services and the University of Tasmania.

Working with major tech platforms, we have found proactive safety measures can reduce harmful behaviours.

Evidence shows a key tool, which is underused, is warning messages that deter and disrupt offending behaviours in real time.

Such messages can be triggered when new or previously known abuse material is shared, or a conversation is detected as sexual extortion or grooming. In addition to blocking the behaviour, platforms can guide users to seek help.

This includes directing people to support services such as Australia’s Stop It Now! helpline. This is a child sexual abuse prevention service for adults who have concerns about their own (or someone else’s) sexual thoughts or behaviours towards children.

Safety by design should not be a choice

The eSafety Commissioner continues to urge companies to take a more comprehensive approach to addressing child sexual exploitation and abuse on their platforms. The technology is already available. But companies often lack the will to use it if it might slow user growth and affect profits.

Transparency reports show us the real state of the industry.

Right now, they reveal a sector that knows how to solve its problems but is moving too slowly.

We need to go beyond reports and strengthen legislation that makes safety the standard, not just an extra feature.

The author acknowledges the contribution of Matt Tyler and Georgia Naldrett from Jesuit Social Services, which operates the Stop It Now! Helpline in Australia, and partners with the University of Tasmania in the CSAM Deterrence Centre.![]()

Joel Scanlan, Adjunct Associate Professor, School of Law; Academic Co-Lead, CSAM Deterrence Centre, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.