The Early History of Bilgola Plateau Public School

by Susan Peacock

SCHOOL ORIGINS

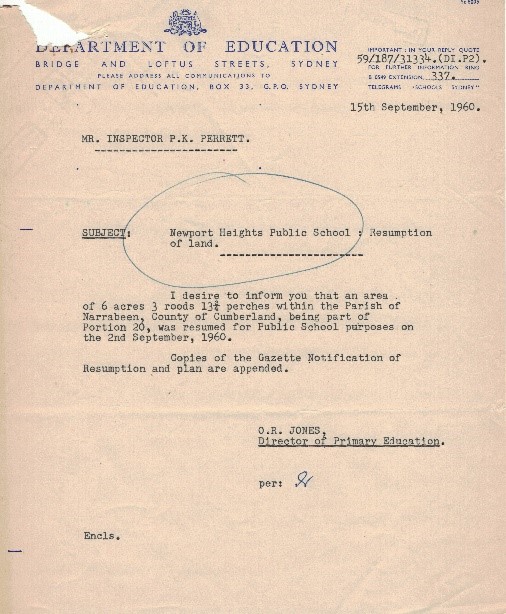

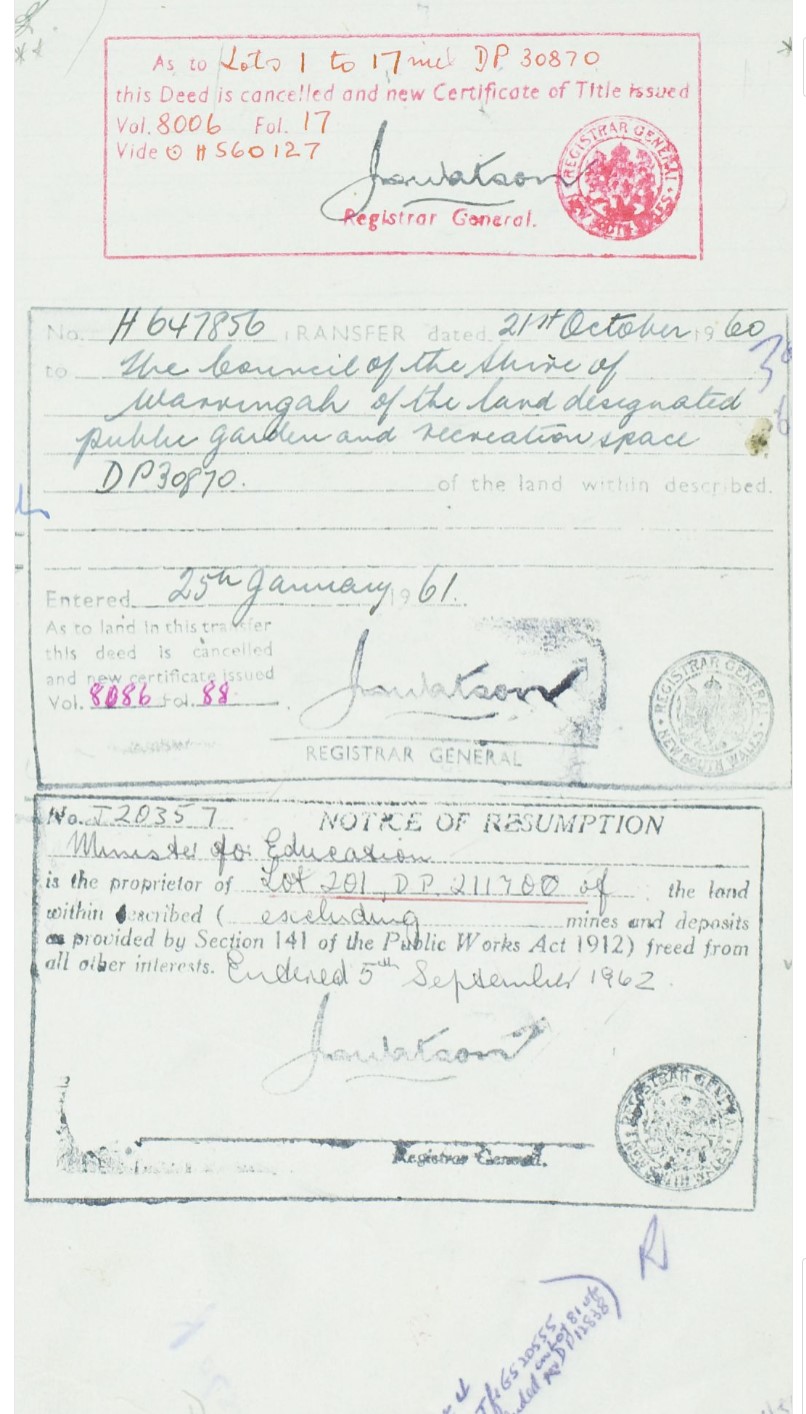

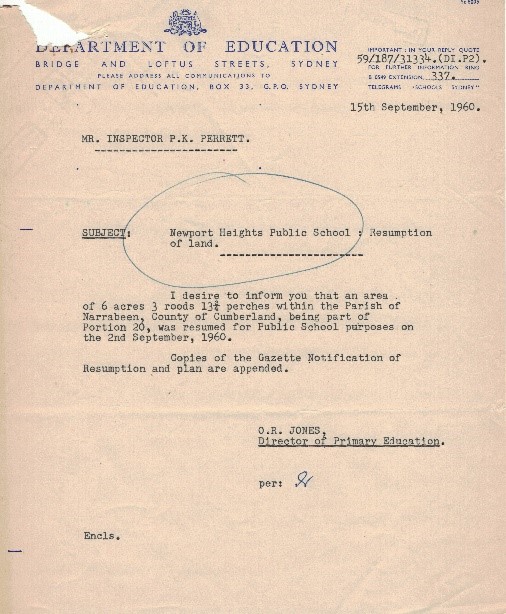

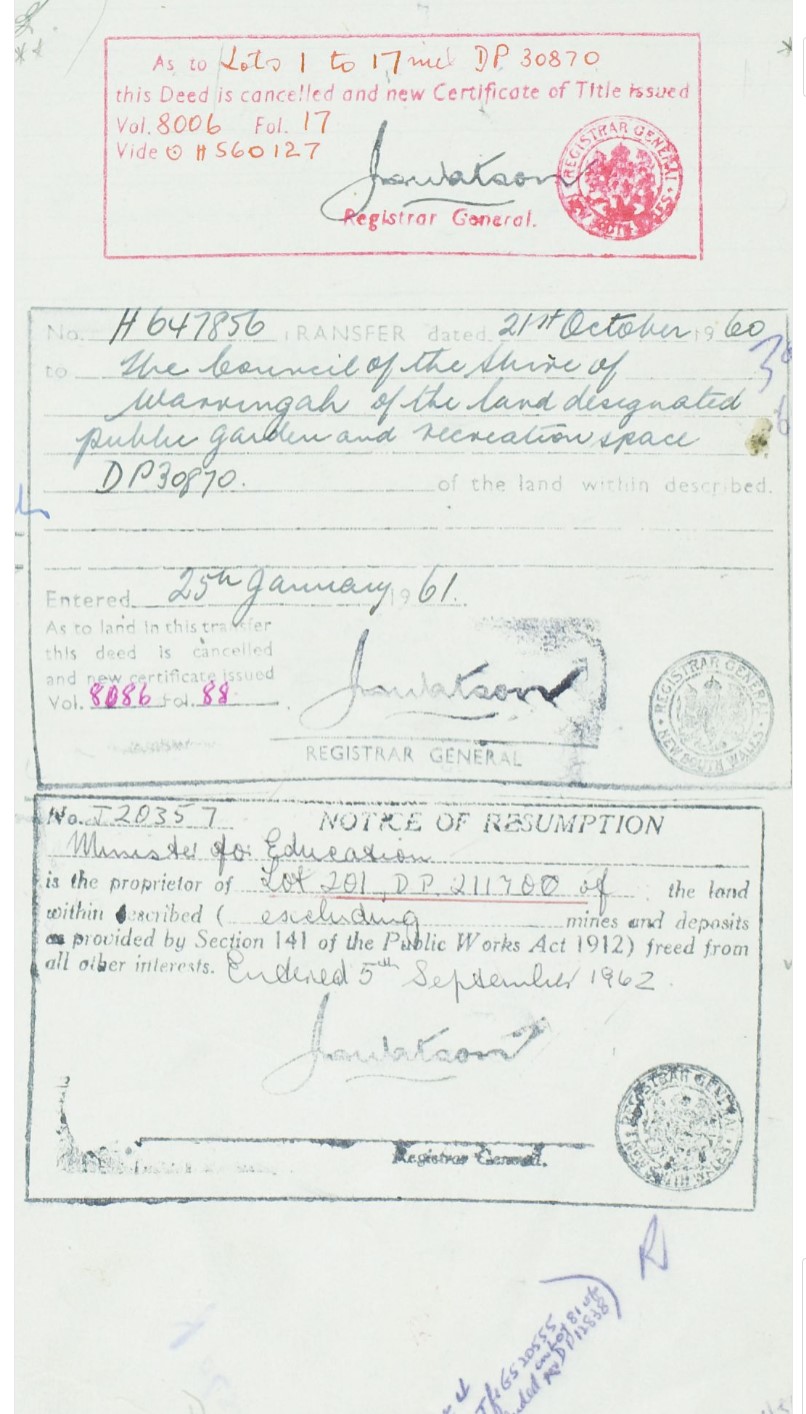

The sleepy holiday villages of the northern beaches began to be more permanently populated during the 1950’s, putting pressure on schools in Avalon and Newport. In September 1959 the Director of Primary Education advised the Valuer General to acquire land for the future Newport Heights Primary School. This purchase was formally completed in September 1960, and an area of “6 acres 3 roods 13 ¾ perches within the Parish of Narrabeen” was resumed for the proposed school.

Letter 15 Sep, 1960 – Newport Height Public School: Resumption of Land; And Map 12.8.60

NOTIFICATION OF RESUMPTION OF LAND UNDER

THE PUBLIC WORKS ACT, 1912, AS AMENDED

IT is hereby notified and declared by His Excellency the Governor, acting with the advice of the Executive Council, that so much of the land described in the Schedule hereto as is Crown land is hereby appropriated, and so much of the said land as is private property is hereby resumed, under the Public Works Act, 1912, as amended, for the following public purpose, namely, a Public School at NEWPORT HEIGHTS and that the said land is vested in the Minister for Education as Constructing Authority on behalf of Her Majesty the Queen.

Dated this 24th day of August, 1960.

K. W. STREET,

by Deputation from His Excellency the Governor.

By His Excellency's Command,

ERN WETHERELL, Minister for Education.

The Schedule

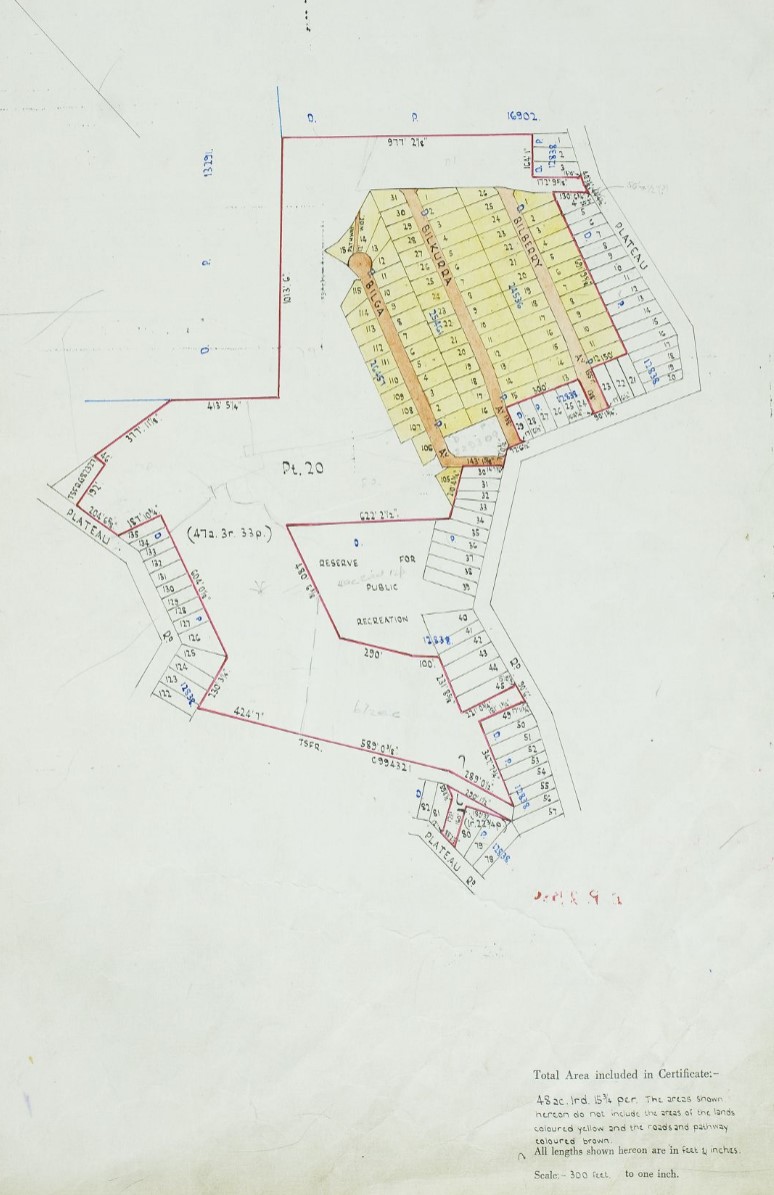

All that piece or parcel of land situate in the Shire of Warringah, parish of Narrabeen and county of Cumberland, being part of the land comprised in Certificate of Title, volume 7,148, folio 94 and also being part of portion 20: Commencing at a point in a north-western side of Plateau-road being also the north-eastern extremity of a south-eastern boundary of lot 45 in deposited plan 12,838; and bounded thence on part of the south-east by that side of that road bearing 190 degrees 47 minutes 30 seconds, 90 feet 6 inches to the south-eastern extremity of a north-eastern boundary of lot 49 in said deposited plan 12,838; on parts of the southwest by the said and another, north-eastern boundary of that lot bearing successively 329 degrees 18 minutes 30 seconds, 17 feet 111 inches and 287 degrees 49 minutes 30 seconds, 181 feet If inches; again on the south-east by the northwestern boundaries of lots 49 to 55 inclusive in said deposited plan 12,838 bearing 197 degrees 49 minutes 30 seconds, 347 feet 7 ½ inches; again on parts of the south-west by northeastern boundaries and part of a north-eastern boundary of lot 7 in deposited plan 28,117 bearing successively 335 degrees 45 minutes 40 seconds, 289 feet 0£ inch 324 degrees 43 minutes 30 seconds, 589 feet 0 inches and 324 degrees 47 minutes 30 seconds, 40 feet; on part of the north-west by a line bearing 54 degrees 30 minutes 10 seconds, 530 feet Of inch to a point in the north-western boundary of a Reserve for Public Recreation of 5 acres 0 roods 211 perches, as shown in said deposited plan 12,838; again on the south-east and on parts of the north-east by the said north-western and by southwestern boundaries of that Reserve bearing successively 197 degrees 49 minutes 30 seconds, 198 feet, 144 degrees 43 minutes 30 seconds 290 feet and 107 degrees 49 minutes 30 seconds, 100 feet; again on the south-east by the north-western boundaries of lots 42 to 45 inclusive in said deposited plan 12,838 bearing 197 degrees 49 minutes 30 seconds, 231 feet 8 1/2 inches; again on the north-east by the south-western boundary of said lot 45 bearing 107 degrees 49 minutes 30 seconds, 221 feet 05 inches; and again on the north-west by the said south-eastern boundary of that lot bearing 59 degrees 18 minutes 30 seconds, 15 feet 10 1/2inches to the point of commencement; having an area of 6 acres 3 roods 13 ½ perches or thereabouts and said to be in the possession of Bilgola Plateau Pty. Limited. (833) NOTIFICATION OF RESUMPTION OF LAND UNDER THE PUBLIC WORKS ACT, 1912, AS AMENDED (1960, September 2). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 2764. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220315750

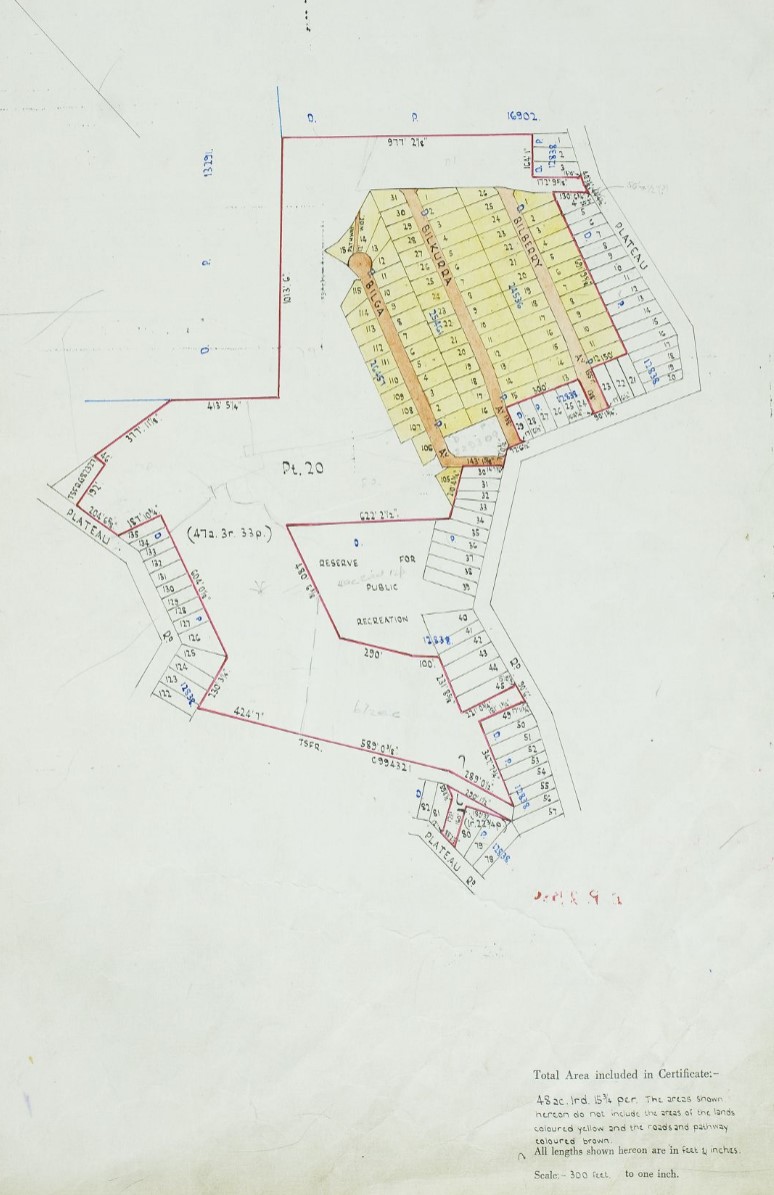

Certificate of Title, volume 7,148, folio 94: map showing acreage (excluding that coloured yellow) - this had been bought by Rose Ana Phillipson originally from the Therry land grant

The resumption for the school notification within Certificate of Title, volume 7,148, folio 94

Changes:

PUBLIC INSTRUCTION ACT OF 1880, AS AMENDED

Notification of Rescission of Resumption

Rescission of Resumption of Land Acquired for Public School

Purposes at Newport Heights, New South Wales

IN pursuance of the provisions contained in subsection (1) of section 4 a of the Public Instruction Act of 1880, as amended, His Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, doth by this notification rescind the notification of resumption of land under die Public Works Act, 1912, as amended, dated the 24th August, 1960, and published in the Government Gazette No. 102 of the 2nd September, 1960, insofar as such notification relates to the land described in the Schedule hereunder.

The Schedule

All that piece or parcel of land situate in the Shire of Warringah, parish of Narrabeen and county of Cumberland, being part of the 6 acres 3 roods 131/2 perches parcel of land resumed for Newport Heights Public School by notification in Gazette of 2nd September, 1960, shown in plan catalogued Ms. 17,712 Sy.: Commencing at the northernmost corner of the said 6 acres 3 roods 13£ perches parcel of land; and bounded thence on the south-east by the northernmost south-eastern boundary of that land bearing 197 degrees 49 minutes 30 seconds 198 feet; again on the south-east by a line bearing 238 degrees 14 minutes 372 feet 51 inches to the westernmost south-western boundary of the said 6 acres 3 roods 13 perches parcel of land; on the south-west by part of that boundary bearing successively 324 degrees 43 minutes 30 seconds 54 feet £ inch and 324 degrees 47 minutes 30 seconds 40 feet to the westernmost corner of that land; and on the north-west by the northernmost north-western boundary of that land bearing 54 degrees 30 minutes 10 seconds 530 feet 1 inch to the point of commencement,—and having an area of 1 acre 19 ½ perches or thereabouts.

Dated at Sydney, this twenty-seventh day of June, 1962.

E. W. WOODWARD, Governor.

By His Excellency's Command,

(4828) ERN WETHERELL, Minister for Education. PUBLIC INSTRUCTION ACT OF 1880, AS AMENDED (1962, July 13). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 2024. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220322926

GETTING STARTED

By 1963 District Inspector, C. S. Clayton, began exploring options to take the growing enrolment pressure from Avalon Public School. In October of that year he wrote to the Director of Primary Education recommending the establishment of an Infants school for the beginning of 1965 on the site purchased in 1960.

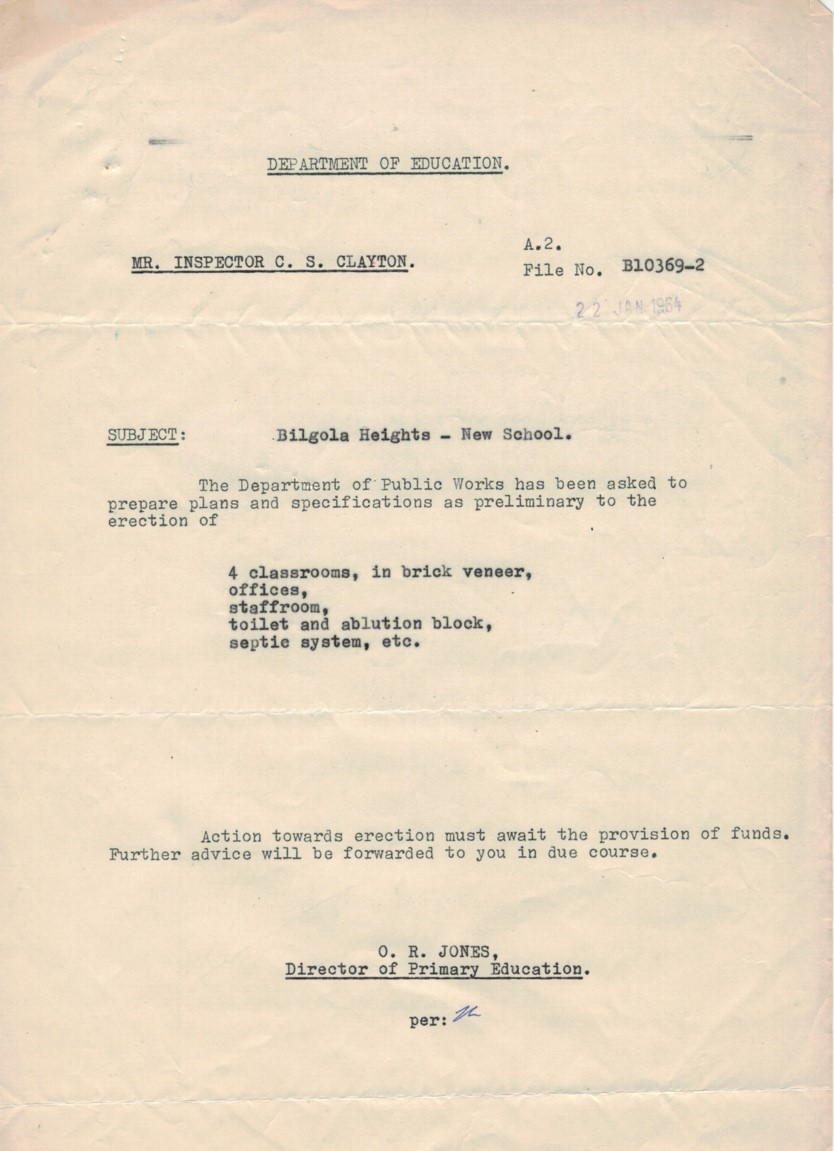

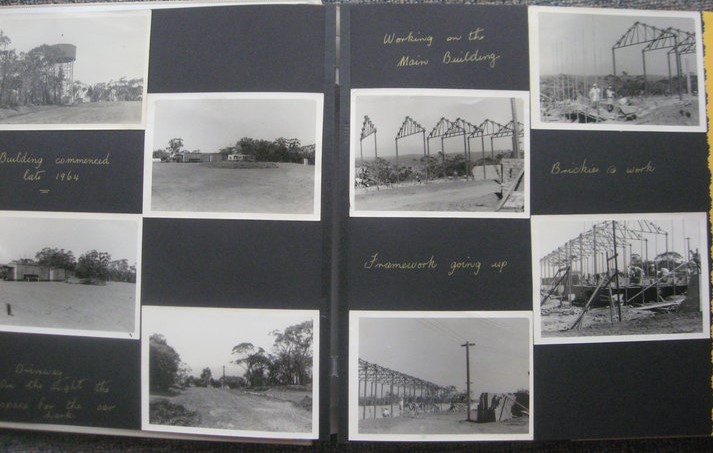

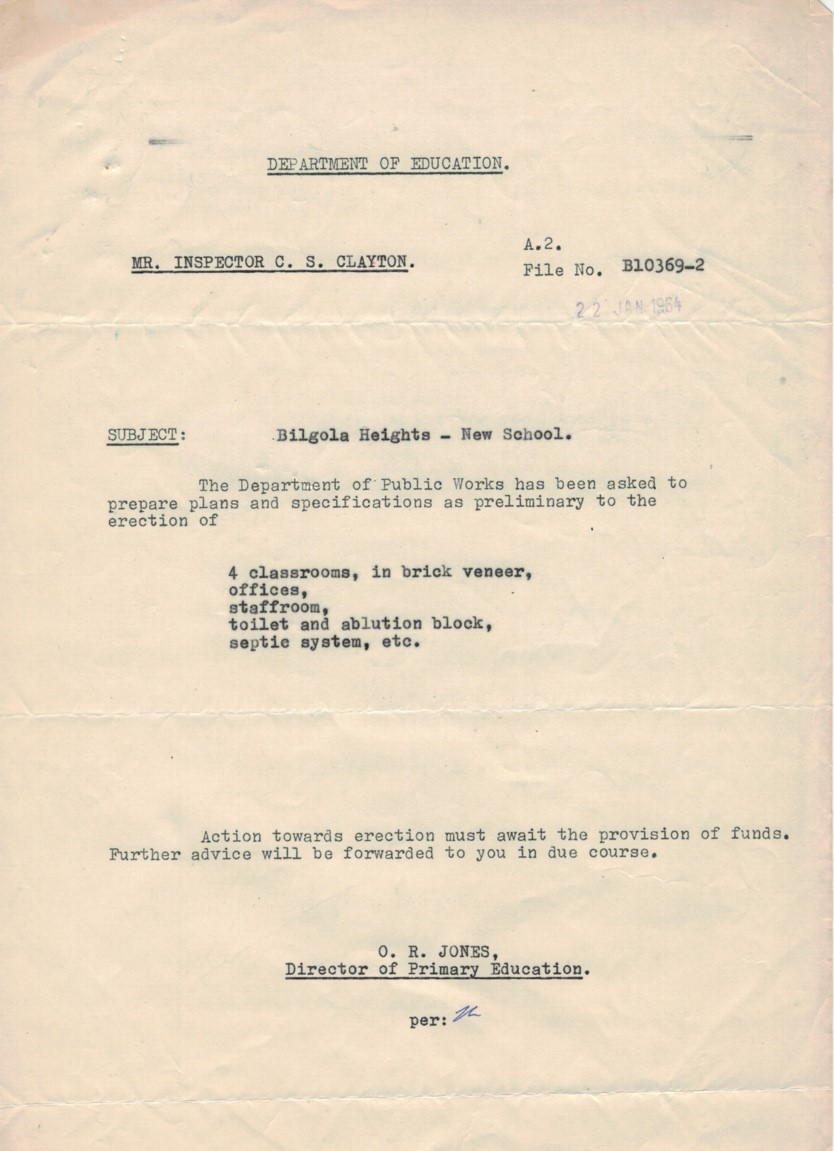

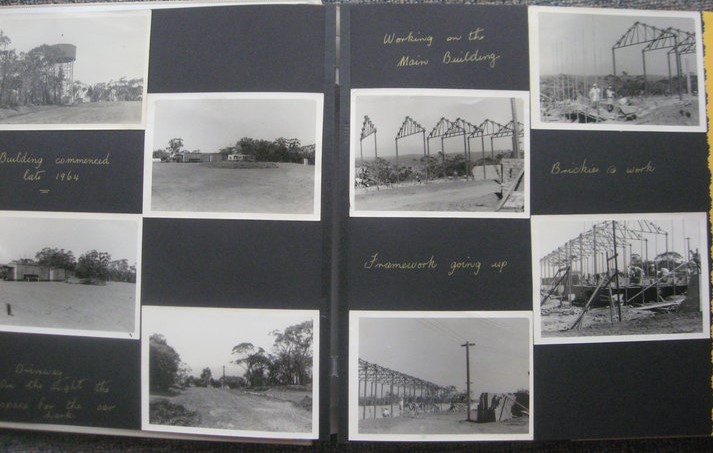

Significantly he wrote that “the Postmaster-General’s Department estimated that the area the school would serve would have space for 1000 homes”. He also advised that although the department refers to the site as Newport Heights Public School the area is more commonly referred to by locals as Avalon Plateau or Bilgola Plateau, and as the land was purchased from Bilgola Plateau Pty Ltd that name seemed appropriate. In January 1964 the Department of Public Works was asked to prepare plans and specifications for “4 classrooms in brick veneer, offices, staffroom, toilet and ablution block “.

Bilgola Heights Plateau School officially announced:

Sydney, 10th January, 1964.

NEW PUBLIC SCHOOL

IT is hereby notified for general information in accordance with the provisions of the 34th section of the Public Instruction Act of 1880, as amended, that it has been decided to establish a school on the Bilgola-Avalon Plateau to be known as BILGOLA HEIGHTS PUBLIC SCHOOL.

E. WETHERELL, Minister for Education.

NEW PUBLIC SCHOOL (1964, January 10). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 26. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220393857

By September 1964 Tenders for work were being advertised:

Bilgola Heights Public School—Levelling and preparation of site. (Specifications available, £1 each.) Department of Public Works—Tenders for Works (1964, September 25). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 3034. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220343176

Bilgola Heights Public School—Supply and Laying of Asphaltic Concrete. - Department of Public Works—Tenders for Works (1965, April 15). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 1267. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220391226

THE INTAKE BOUNDARIES DEFINED

At a conference of Principals held in February 1965 the following boundaries were recommended for Bilgola Plateau Public School.

“Starting at the eastern extremity of the recreation area opening off Kanimbla Crescent, take a line northerly to the junction of Palmgrove and Plateau Roads, thence along the eastern side of Plateau Road, around The Pinnacle, thence in a line to the intersection of Stromboli Place and Bilwarra Road, thence along the western side of Lower Plateau Road, the western side of Argyle Road, the southern side of Raymond Road, the eastern side of York Terrace to its intersection with Grand View Drive, thence easterly to the starting point.”

This boundary was to apply to all new enrolments in 1965 up to the end and including Grade 3, all pupils who were enrolled in 1964 in the grades Kindergarten, first and second grade who were currently at Avalon Public School. Many families from this intake area with children at Avalon Public School were concerned about the transfer of their children to the new school on the hill. The Minister for Education, Ern Wetheral, wrote “local children transferring to Bilgola Plateau are not likely indefinitely to experience any disadvantages”.

MOVING DAY

At the commencement of the new school year in 1965 construction of the school was not yet complete. To ensure a smooth transition when the site was ready to be occupied, the 49 Infants students enrolled in Bilgola Plateau Public School and staff commenced their year in an outbuilding on the grounds of Avalon Public School (present day Avalon OOSH). Their morning recess and lunch times were staggered with those of Avalon Public School to create better cohesion among its small population.

At last, the Director of Primary Education, C.S. Clayton, advised that the premises could be occupied on Monday 28th June 1965. On that day the Principal, Mrs Rita Reid, assembled the only other member of staff Mrs Janette Drabwell, and students at their temporary accommodation in Avalon Public School and together they walked up Plateau Road and onto their new campus.

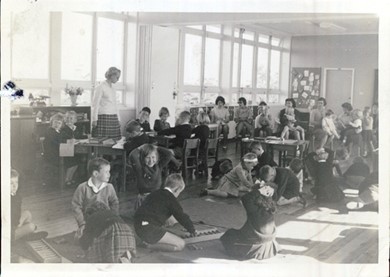

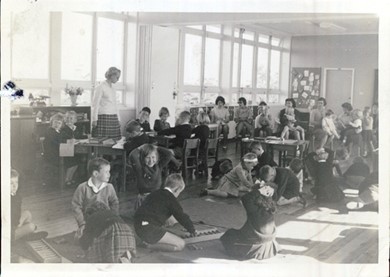

At that time it was not uncommon for class sizes to be 40 or 45 children, so two teachers and 49 children was considered “teacher’s Heaven”. There was no telephone on site. The Education Department suggested that Mrs Reid and Mrs Drabwell use the public telephone on the corner near the shops if a child were unwell, leaving the other teacher to teach their class while they ran down the road.

Principal, Mrs Rita Reid, with Third Grade students. From Left – Karen Steilberg, Deborah Wood, Andrew Carnell, Doris Groenendyk, Rosalind Agar; Front row – Sarah Buchanan, Jane Buchanan, Diana Page.

Principal, Mrs Rita Reid, with Second Grade students. Backrow: Mark Gonsalves, Eric Drabwell, Ross Montague, David Watson, David Gray, John Gray, David Coxon, Simon Page. Front row - Debra Gains, Quentyn Jacobs, :Lesley Swan, Jacqueline Simpson, Lynne Johnstone, Vicki Parker.

Mrs Drabwell with First Grade students. From left – Christopher Capel, John Buchanan, Mark Culverson, Geoffrey Fisher, Stephen Michelson, Grant Dawkins; Front row – Robyn Armsworth, Kerry Wardle, Lisa Culverson, Christine Shulz, Susan Light.

SCHOOL WARMING

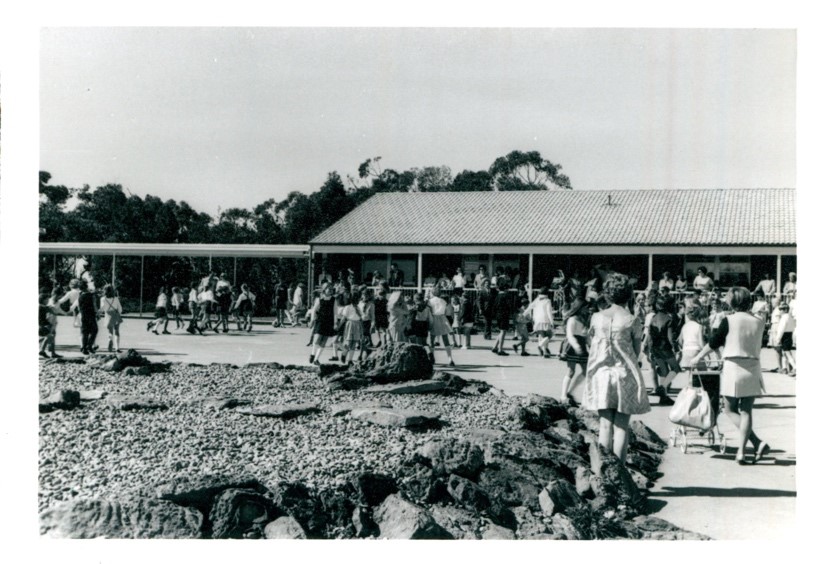

On Saturday 10th July, 1965 school families were invited to bring a plate and the children were able to proudly show their parents through the new school. The day ended with a party for the children and afternoon tea for parents and other family members.

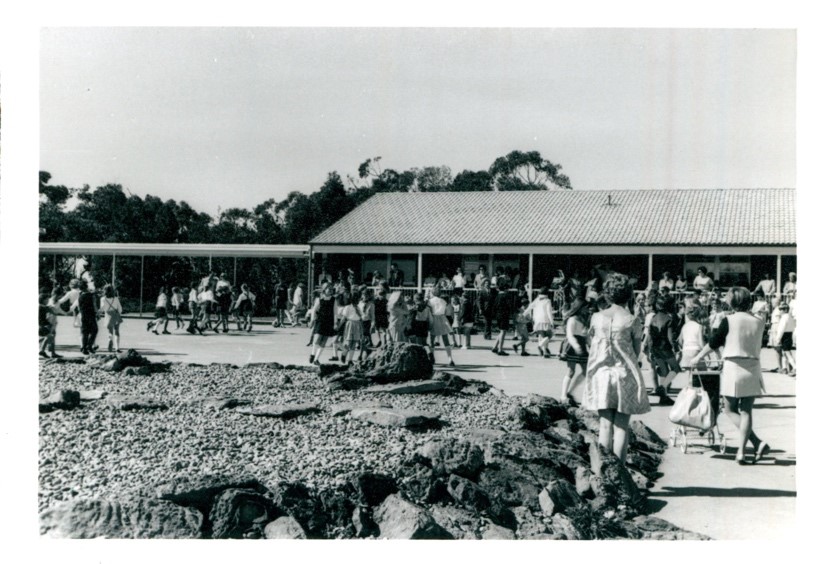

In that first year the school premises consisted of two buildings. These were today’s Administration block with its four classrooms, and the toilet and ablution block on the opposite side of the unpaved quadrangle. An additional classroom block with four more classrooms was built on the eastern side of the quadrangle in 1966. The library and present-day infants buildings were constructed ten years later in 1976. The original ‘tuckshop’ was an open breeze-block space which stood where the library now stands.

On the Open Day in 1965

SCHOOL SONG

There have been three school songs since the school opened in 1965. Each refers to the beautiful environment which surrounds us, and to the importance BPPS has always placed on social responsibility, community values and caring for others.

1969

Set high on a plateau is our lovely school

Where we learn to live by the great Golden Rule

We see sparkling waters of inlet and sea

While deep in the blue above birds fly so free.

Bilgola, Bilgola, the school of our childhood

Oh we are so proud of your beautiful name,

And so dear Bilgola, we’ll work for your glory,

We’ll always do our best for you,

Bilgola, our school.

Words T.P. Hackett. Sung to tune of “The Bells of St Mary’s”

1988

Bilgola’s our school

School to be proud of

Shaping our future

Enjoying our school days

Teachers and students

All do their best

Hoping each new day

Brings us more joy.

Kindness and knowledge

Courtesy- always

This is our motto

This our guide.

Let’s hear our voices

We are the children

We make the choices

That shape the world.

Building and learning

Forming our friendships

Working together

Aiming for goals.

Ours is the sharing

Ours is the caring

Ours is the striving

To reach for the stars.

Words by Carter Family, sung to the tune of “Morning has Broken

2012

Bilgola is our school upon the plateau

High above the glistening seas

Between Pittwater and the ocean

Among the eucalyptus trees

We care for our wildlife and bushland

For the food that we love to grow and share

At Bilgola we can make a difference

At Bilgola we show that we care

Bilgola Plateau, our school by the sea

Bilgola Plateau you are the school for me

Kindness, courtesy and knowledge

This is our motto and our guide

To be responsible and respectful

These are our values held with pride

To aim for success in all our learning

And strive hard in each and every way

At Bilgola we will work together

In our learning, our friendship and play

Bilgola Plateau, our school by the sea

Bilgola Plateau you are the school for me

Bilgola Plateau, our school by the sea

Bilgola Plateau you are the school for me

Words and music Rhonda Mawer, Music teacher, with collaboration of Assistant Principal Jackson.

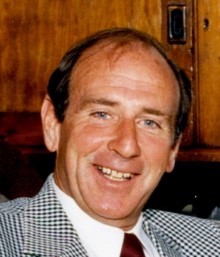

PRINCIPALS

1965 Rita Reid

1966 - 1970 Pat Hackett

1971 – 1976 Myra Thomas

1977 - 1979 Tom Wilkins

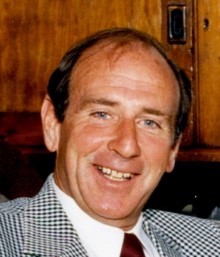

1980 - 1992 David Moxon

1993 – 1994 Phyllis Richards

1995 - 1999 Dennis Marks

2000 - 2009 Sharon Sands

2010 - 2012 Vicki Johnson

2013 - Present Cindy Gardiner

![]()

Ingleside Riders Group Inc. (IRG) is a not for profit incorporated association and is run solely by volunteers. It was formed in 2003 and provides a facility known as “Ingleside Equestrian Park” which is approximately 9 acres of land between Wattle St and McLean St, Ingleside.

Ingleside Riders Group Inc. (IRG) is a not for profit incorporated association and is run solely by volunteers. It was formed in 2003 and provides a facility known as “Ingleside Equestrian Park” which is approximately 9 acres of land between Wattle St and McLean St, Ingleside.