December 16, 2018 - January 12, 2019: Issue 388

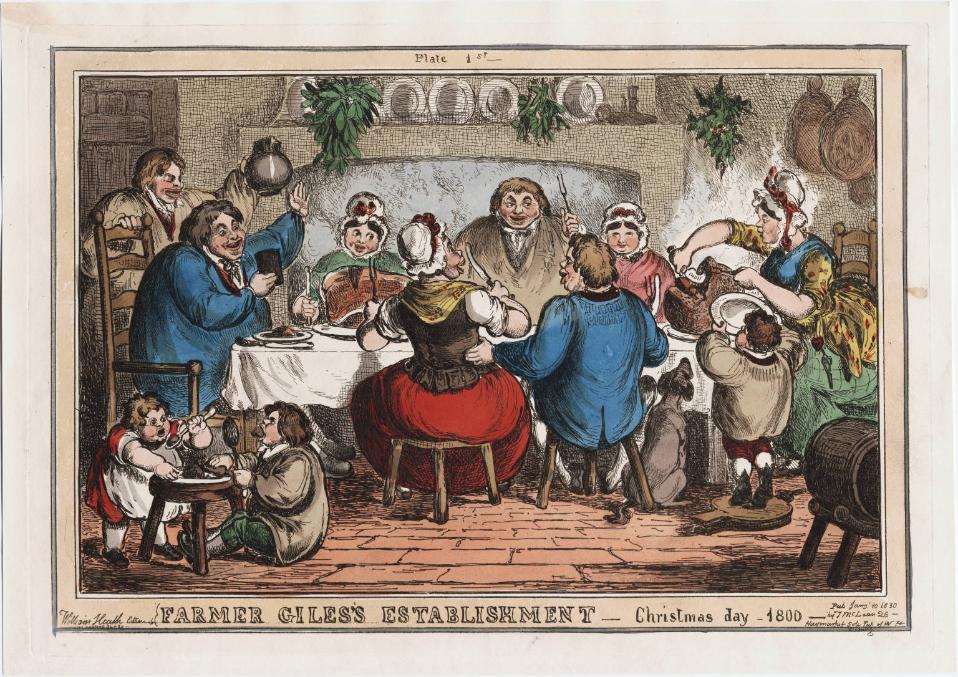

An Old-Time Christmas Feast

Courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library

There are so many great free magazines filled with ideas for an Australian Christmas Feast, ones that take into account eating hot food on a hot day is not always going to appeal, although nor is a bag of prawns that's been sitting in the esky quietly melting for a few hours, that offering any ideas would be similar to 'taking snow to an Eskimo'.

In a place where so many cultures live side by side everything can end up on the table from fish to meatballs to lamb, and that's before we get near those vegetarian specialities or all those traditional breads, cakes and tarts or fruits and nuts and everyone's variation on the egg-nog recipe or even a spiced mead.

So instead of offering the thousands of choices that may take place this year - a look into yesteryear.

AN OLD CHRISTMAS FEAST.

Here is the menu of a Christmas feast served up at an English dinner-table in the reign of Charles I. :

"A soup, of snails, a powdered goose, a joli of salmon, a dish of green fish buttered with eggs." This was the first course.

Then came: "A Lombard pie," "a cow's udder roasted," "a grand boiled meat," "a hedgehog pudding," "a rabbit stuffed with oysters," "Polonian sausages," "a mallard, with cabbages," and "a pair of boiled cocks."

To these succeeded "A spinnage tart," "a carbonadoed hen, :" "a pie of aloes." ,"eggs in moonshine," "christal jelly," . "jumballs,'! "quidany," "bragget," and "walnut suckets."

Cock-ale. surfeit waters, canarysack, and Gascony wines formed the liquors wherewith to wash down this strange repast. AN OLD CHRISTMAS FEAST. (1903, February 7). Western Mail (Perth, WA : 1885 - 1954), p. 53. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33268653

Yule or Yuletide ("Yule time") is a festival observed by the historical Germanic peoples. Scholars have connected the celebration to the Wild Hunt, the god Odin, and the pagan Anglo-Saxon Mōdraniht. It later underwent Christianized reformulation resulting in the term Christmastide.

Terms with an etymological equivalent to Yule are used in the Nordic countries for Christmas with its religious rites, but also for the holidays of this season. Today Yule is also used to a lesser extent in the English-speaking world as a synonym for Christmas. Present-day Christmas customs and traditions such as the Yule log, Yule goat, Yule boar, Yule singing, and others stem from pagan Yule.

Yule is the modern English representation of the Old English words ġéol or ġéohol and ġéola or ġéoli, with the former indicating the 12-day festival of "Yule" (later: "Christmastide") and the latter indicating the month of "Yule", whereby ǽrra ġéola referred to the period before the Yule festival (December) and æftera ġéola referred to the period after Yule (January). Both words are thought to be derived from Common Germanic *jeχʷla-, and are cognate with Gothic (fruma) jiuleis; Old Norse, Icelandic, Faroese and Norwegian Nynorsk jól, jol, ýlir; Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian Bokmål jul. The etymological pedigree of the word, however, remains uncertain, though numerous speculative attempts have been made to find Indo-European cognates outside the Germanic group, too. The noun Yuletide is first attested from around 1475.

The word is attested in an explicitly pre-Christian context primarily in Old Norse. Among many others (see List of names of Odin), the long-bearded god Odin bears the names jólfaðr (Old Norse for "Yule father") and jólnir ("the Yule one"). In plural (Old Norse jólnar, "the Yule ones") may refer to the Norse gods in general. In Old Norse poetry, the word is often employed as a synonym for 'feast', such as in the kenning hugins jól (Old Norse "Huginn's Yule" → "a raven's feast").

Jolly may share the same etymology,[6] but was borrowed from Old French jolif (→ French joli), itself from Old Norse jól + Old French suffix -if (compare Old French aisif "easy", Modern French festif = fest "feast" + -if). The word was first mentioned by the Anglo-Norman chronicler Geoffrey Gaimar in his Estoire des Engleis, or "History of the English People", written between 1136–40.

THE YULETIDE FEAST

Origin of Christmas Customs.

By "Mareotis."

CHRISTMAS! Is there any other word in the world which brings to us so many pleasant thoughts? Yet how many know the history of many of the customs of the Festival of Yule which we observe today. They come down to us from a time when ritual played an important part in the lives of peoples who were ready with appropriate rites throughout the year, which were practised well into the nineteenth century, and traces of them still survive in folk customs.

Here is a fourteenth-century recipe for cooking the peacock:

To roste a pecokke take and flee off the skvnne, with the fedure, tayle and nekke and the hed thereon: then take the skynne with all the fedure and lay hit on a tfable abrode and straw thereon grounden comyn. Now take the pecokke and roste hym, endore hym with raw yolks of eggs and when he is rosted take hym off and let hym cool awhile. Now take hym and sowe hym in his skynne, gild his combe and so serve hym forthe with the last cours.

Feast Nine Hours Long.

Although turkey had found its way to the royal Christmas table as early as the reign of Henry VIII, who was the first Englishman to taste it at a Feast of the Field of the Cloth of Gold given by Francis I, for long it was considered in England but a preliminary to the roast boar which was washed down with copious draughts of ale to the accompaniment of bibulous songs, and only within the last century has it taken the place of honour as the main dish. At one of the famous and lavish banquets of Henry VIII at Hampton Court the course took nine hours to complete. This gargantuan meal consisted of a shield of brawn, roasted neat's tongue, boiled capon, boiled beef, minced meat pies flavoured with hock, sherry, lemon and orange juice spiced, haunch of venison, stuffed kid, olive pie, goose, turkey and peacock. Some of the chroniclers report that after a meal of this kind Bluff King Hal behaved himself in an unseemly manner and sat the Lady Jane Seymour on his knee to the exasperation of his spouse.

The First Plum Pudding.

A stimulating old English beverage was made with ale, eggs, nutmegs, raisins, sugar, cloves, roasted apples and spices. which went back. to Saxon times, from which our plum pudding evolved through raisin gravies of the Middle Ages when fruits and spices were made into liquid pastes to be served with boar's head. Christmas pudding was at the beginning a breakfast dish eaten in the form of porridge with plums in it, but by 1731 it had become a savoury pottage which one Thomas North in his account of the Christmas festivities in London in that year described as "a thing they call plumb pottage, which may be good for ought I know. though it seems to me to have fifty different tastes."

Two centuries ago during Cromwell's parliamentary reign the plum pudding as we know it was a matter for newspaper controversy and little known; indeed it was an indictable offence to indulge in what was considered a heathenish man-made practice.

James I detested boar's head, which had been used from ancient times, taking the place of the sacramental character of the harvest supper: it was believed to be an embodiment of the cornspirit.

Even in the modern world this superstition is not entirely lost sight of, for when the corn sways in the wind in Thuringen there are still some who say "The boar is rushing through the corn." The Esthonians of the island of Oesel call the last sheaf of the harvest the Rye-boar, from which a long cake called the Christmas boar is made. In Denmark at Yule a loaf is baked in the shape of a boar and at one time was made from the last sheaf. This is called the Yule boar and is not eaten but kept till spring when the new seed is sown, when part of it is used as a quickening influence on the seed as a charm for a good harvest.

Beginning of the Cracker.

Our modern crackers had their origin in the large cake made for Twelfth Night, the end of the festive season. Two emblems were hidden in it for a lady and a gentleman. Whoever received them became king and queen of the feast and held a mock court, placing verses and motoes into a hat which was handed round, from which emerged the motto in our present cracker.

The decorated fir tree with candles, hung with holly, was of German origin, and emerged from an earlier belief in sylvan sprites for whom evergreens were hung inside the home that they might shelter from the cold winters. Charlotte, consort of George III, attempted to introduce this custom into England, but it was considered exotic and not quite the thing and was not incorporated in the festivities of Britons till the second Christmas of the late Queen Victoria in 1841 at Windsor Castle, who re-introduced it after her marriage to the Prince Consort. There is a quaint legend about the holly. The smooth variety is said to be the male and the prickly the female. and according to which was brought into the house the husband or the wife would have the upper hand during the coming year. The holly is the greenwood tree of Robin Hood; it grows well in the open and has a very long life, but does not grow well in the shadows of larger trees. Pliny recorded a holly tree in his day which tradition said was older than the Eternal City itself.

THE YULETIDE FEAST (1936, December 19). The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article41261836