This Fish Serving was bought in the U.K. in 1957 and dates from the 1800's. These are large implements from a time when there was a fish course, or fish was served regularly. In Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management, chapter 40, bills of fare for a grand dinner for eighteen, January 1887, 'follow two kinds of fish and two kinds of soup with four entrées: Ris de Veau, Poulet à la Marengo, Côtelettes de Porc and a Ragoût of Lobster. Entrées were followed by a Second Course and a Third Course, of game and fruit.'

Measuring 32.5cm for the knife and 25.5 cm for the fork, practical elegance and an Artisan's craft is shown in the finish of these two implements.Engraved with two men wearing Chinese hats fishing from a boat with pagodas in the background, and a dragon or sea serpent of some description at the base of the blade, it sparks the curious to try and work out who made it, where and when they did, and who is the Artisan of this fine work…of such cutlery.

Cutlers are the makers of Cutlery, and now the word is also extended to those who sell cutlery. The word cutler derives from the Middle English word 'cuteler' and this in turn derives from Old French 'coutelier' which comes from 'coutel'; meaning knife (modern French: couteau).

The first documented use of the term "cutler" in Sheffield appeared in a 1297 tax return. A Sheffield knife was listed in the King's possession in the Tower of London fifty years later. Several knives dating from the 14th century are on display at the Cutlers' Hall in Sheffield.

The Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire is a trade guild of metalworkers based in Sheffield, England. It was incorporated in 1624 by an Act of Parliament. The head is called the Master Cutler. Its motto is Pour Y Parvenir a Bonne Foi (To Succeed through Honest Endeavour).

In the original act of Parliament, the company was given jurisdiction over:

"all persons using to make Knives, Blades, Scissers, Sheeres, Sickles, Cutlery wares and all other wares and manufacture made or wrought of yron and steele, dwelling or inhabiting within the said Lordship and Liberty of Hallamshire, or within six miles compasse of the same".

This was expanded to include other trades by later acts, most notably steelmakers in 1860. In the same year the Company was given the right to veto any proposed name of a limited company anywhere in the United Kingdom which contains the word "Sheffield". They also supply marks to approved cutlers and promote Sheffield steelware.

The company has been based at Cutlers' Hall (opposite the cathedral on Church Street) since 1638. The current hall is the third to have been built on the site. The second was built in 1725 and the third in 1832. It was extended in 1867 and 1888.

The city of Sheffield in England has been famous for the production of cutlery since the 17th century and a train – the Master Cutler – running from Sheffield to London was named after the industry.

The vast majority of English, Scottish and Irish silver produced in the last 500 years is stamped with either 4, 5 or 6 symbols, known as hallmarks. The prime purpose of these marks is to show that the metal of the item upon which they are stamped is of a certain level of purity. The metal is tested and marked at special offices, regulated by the government, known as assay offices. Only metal of the required standard will be marked. It is a form of consumer protection, whose origin goes back almost 1000 years.

The components of silver hallmarks

There are up to six elements of a hallmark, of which four are most common. They are: the town mark, the makers mark, the date or annual letter, the lion passant, the Britannia mark and the sovereign’s head.

Historically, hallmarks were applied by a trusted party: the 'guardians of the craft'. Hallmarks are often confused with "trademarks" or "maker's marks". A hallmark is not the mark of a manufacturer to distinguish his products from other manufacturers' products: that is the function of trademarks or makers' marks. To be a true hallmark, it must be the guarantee of an independent body or authority that the contents are as marked. Thus, a stamp of '925' by itself is not, strictly speaking, a hallmark, but is rather an unattested fineness mark.

Precious metals are rarely used in their pure form, as they are too soft. Gold, silver, platinum and palladium are generally mixed (alloyed) with copper or other metals to create an alloy that is more suitable to the requirements of the jeweller or silversmith. The hallmark indicates the amount of precious metal in the alloy in parts per thousand (the millesimal fineness).

In 1300 King Edward I of England enacted a statute requiring that all silver articles must meet the sterling silver standard (92.5% pure silver) and must be assayed in this regard by 'guardians of the craft' who would then mark the item with a leopard's head.

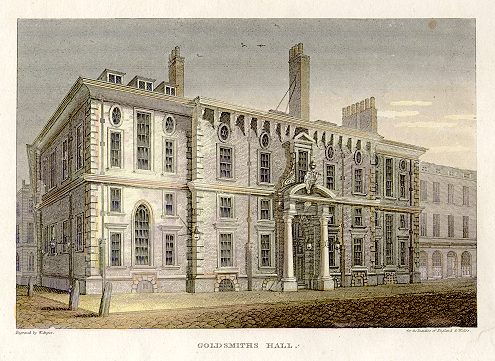

Right: The second Goldsmiths' Hall c.1814 Engraved by W Angus.

In 1327 King Edward III of England granted a charter to the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths (more commonly known as the Goldsmiths' Company), marking the beginning of the Company's formal existence. This entity was headquartered in London at Goldsmiths' Hall, from whence the English term "hallmark" is derived. (In the UK the use of the term "hallmark" was first recorded in this sense in 1721 and in the more general sense as a "mark of quality" in 1864.)

Step 1 - Look for the standard mark

There are 5 standard marks found on British Silver

The walking lion for all sterling silver made in England

The standing lion for all sterling silver made in Edinburgh

The thistle for all sterling silver made in Glasgow

The crowned harp for all sterling silver made in Dublin

The image of Britannia for Britannia standard silver

Step 2 - Look for the town mark

Step 3 - Look for the duty mark

Step 4 - Look for the date letter

Step 5 - Look for the Maker’s Mark

The Maker’s mark was initially a picture, but this practice was superseded by using the first two letters of the maker’s surname and later the initials.

The marks on the Fish knife and fork server set

'EP' is a generic mark for Electro Plated, often used together with a "crown".

Sheffield Plate is a cheaper substitute for sterling, produced by fusing sheets of silver to the top and bottom of a sheet of copper or base metal. This 'silver sandwich' was then worked into finished pieces. At first it was only put on one side and later was on top and bottom.

Modern electroplating was invented by Italian chemist Luigi V. Brugnatelli in 1805. Brugnatelli used his colleague Alessandro Volta's invention of five years earlier, the voltaic pile, to facilitate the first electro-deposition. Unfortunately, Brugnatelli's inventions were repressed by the French Academy of Sciences and did not become used in general industry for the following thirty years.

Silver plate or electroplate is formed when a thin layer of pure or sterling silver is deposited electrolytically on the surface of a base metal. By 1839, scientists in Britain and Russia had independently devised metal deposition processes similar to Brugnatelli's for the copper electroplating of printing press plates.

Soon after, John Wright of Birmingham, England, discovered that potassium cyanide was a suitable electrolyte for gold and silver electroplating.

Wright's associates, George Elkington and Henry Elkington were awarded the first patents for electroplating in 1840. These two then founded the electroplating industry in Birmingham England from where it spread around the world.

Common base metals include copper, brass, nickel silver - an alloy of copper, zinc and nickel - and Britannia metal - a tin alloy with 5-10% antimony.

The marks of electroplated silver were often inspired to the hallmarking used for sterling silver and the maker was identified by its initials inside a series of squares, circles, shields, etc.

In trying to work out what we have here, without going blind, we identified marks that could mean Dublin, Glasgow, and letters that could be a Maker with initials DPYRR or RR, RP or a few other variations. Probably best to leave such things to the experts, but if you have a few days to spare, and a good magnifying glass to hand, there’s a great website that lists many EP silver marks:

http://www.silvercollection.it/SILVERPLATEHALLMARKSJJ.html

How to Date Your Silverplate

From centuries British silver is protected by the stamping of symbols and letters identifying the maker, the Assay Office and the date in which the quality of the silver piece was verified. Thanks to the "date letter" any piece of British sterling silver can be exactly dated.

Old Sheffield Plate and Electroplated silver are not subject to this practice and the regulation issued by the authorities had the main objective of preventing possible frauds by unscrupulous sellers of plated ware. The best-known initiative is the prohibition (effective from c. 1896) of stamping plated wares with the "crown", to avoid misunderstanding with the symbol identifying the Sheffield Assay Office.

The absence of an official dating system makes it difficult to date silver plated wares. An approximate date can be determined by examining:

- the style of the object

- the presence or absence of the crown (before or after c. 1896)

- the date of registration of the pattern at the Patent Office

- the presence of a dated dedication

- the date of the event (example: King/Queen Coronation or Jubilee commemorative spoons)

- "Ltd" or "Ld" on the mark denotes a date after 1861 (but in most cases not before 1890)

- a registered number (Rd followed by a number) denotes a date after 1883

- "England" denotes a date after 1891 (mandatory for export in the USA - McKinley Tariff Act of 1890-)

- "Made in England" denotes a 20th century date (mandatory after 1921 for export in the USA)

The largest manufacturers introduced, on a voluntary basis, a dating system of their silver plate based on series of letters of various style contained into shields or geometric figures. The first was Elkington (1841), followed by Walker & Hall (1884) and Mappin & Webb (but other less known makers tried to do something similar).

So our set is old – pre 1896.

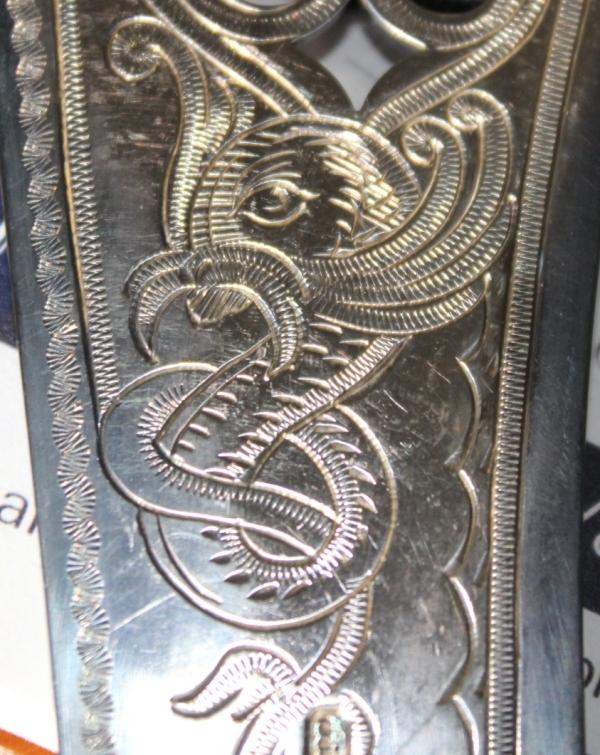

The Engraving on knife is two men with Chinese hats and pagoda in background and on the lower part of the blade, what may be a whale, dolphin, manatee or dragon. Incorporating such engravings and filigree work was also popular during the 1800’s in the U.K. though – so spending more days scruntising anything similar has proven to be of no avail.

Engraving on blade of knife

Engraving at Base of Knife blade

So, to the handle pattern – this is what is defined as ‘the Kings Pattern’. The ‘Kings Pattern’ was the most popular of English patterns, featuring the honeysuckle flowers and shell motif. Credited to the silversmithing brothers John and Henry Lias, the pattern dates from around 1820 (some sources state 1836) and was heavily influenced by the decor and ornamentation of the period.

The cutlery handle pattern

So perhaps poring over the History of Fish Servers may bring us closer to who made this gorgeous set.

The earliest examples of the fish slice were made around 1735. They were shaped as a triangular pointed trowel, often with round corners with pierced decorations. Their use was to drain and serve small fishes directly from the pan. After 1745 the outline became symmetrically elliptical as they were used to separate and serve portions of a larger fish.

The scimitar blade was introduced c. 1780 and was highly popular until around 1800. To this was added the large broad fork and the two became Fish Serving Sets. Often a wide piercing covered the blade, presenting examples in baroque or rococo style where the removed metal was more than that retained.

The piercing was often enhanced by bright-cutting, with one or more fish forming a central motif. In the case of our set, that wonderful duo of fishermen (?) upon a river somewhere and that manatee or dolphin or sea serpent or whale on the lower part of the blade.

Presentation boxes with velvet and satin-lined interiors are quite common with the Victorian versions.

‘Unusual examples with finely pierced and engraved decoration are sought after, especially with fish motifs. Carved ivory or mother-of-pearl handles were often works of art in themselves.

If the service consists of a knife and fork then the hallmarks must match. If the set has knife-handles (i.e. they have a separately made handle as opposed to a contiguous piece of silver) then there should be a corresponding mark as well.’– Bryan Douglas, Antique Silver, U.K.

This places our scimitar shaped blade and its fork with the same hallmarks into the late 1800’s then, but still no closer to finding the Artisan who engraved this blade.

Unfortunately the box it came in has disappeared along the ways. This Fish Server set won’t though – we’re looking forward to hearing a few other shared insights of the Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England of 1957 every time this set is used in family fish feasts.

The only query left now – why a Leopard for London?

In the reign of Edward I it was decided that the fineness of silver for both coin and wrought plate should be standardised and thus the statute of 1300, titled "Vessels of Gold shall be essayed, touched, and marked. The King’s Prerogative shall be saved" , was enacted making sterling (11oz 2dwt in the troy pound) that standard for all English silver. This statute was originally written in old Norman French, in which language the following directive is given: "E qe nul manere de vessele de argent ne parte hors des meins as overers tant qe ele soit assaie par les gardiens du mester e qu ele soit signee de une teste de Leopart".

As ‘teste’ translates as head this passage therefore translates as: "......and that no manner of vessel of silver depart out of the hands of the workers until it be essayed by the Gardiens ( Wardens) of the craft, and further that it be marked with the Leopard’s Head,........")

The statute went on to say: ".....and that all the good towns of England, where any goldsmith be dwelling, shall be ordered according to this statute as they of London be;....." and ".....and that one shall come from every good town for all the residue that be dwelling in the same unto London; for to be ascertained of their touch."). A passage in the Goldsmiths’ Company’s charter of 1327 contains similar wording, although the word "fetch" instead of "ascertained" is used, with the addition of the sentence ("….also the punch with the leopard’s head with which to mark their work as was ordained in times past….").

It can be seen from this that not only was the leopard’s head a standard mark but also that its use applied to all goldsmiths throughout the land and not just those working in London. It was not until 1856, when the statute of 1300 was repealed by the statute 19 & 20 Vict. c. 64, that the leopard’s head mark could have been used for any purpose other than a fineness mark.

There appears to be no evidence that representatives from any town did go to London to receive a punch of the Leopard’s head or that any Royal Commissioners, "responsible for assaying and marking in cities throughout the realm" in accordance with a statute of 1363 and an ordinance of 1379, were ever appointed. This has caused some authorities to attribute, quite erroneously, a dual purpose to this mark. Although it was designated as a standard mark and applied rigorously at the London Assay Office it appears not to have been so at other towns until the 18th century and has thus been said to be the London mark whereas, in fact, London had no distinguishing mark of its own at this time. This has led to some confusion since, in its capacity as the standard mark, it was later required to be stamped on plate assayed at the offices at Bristol, Chester, Exeter, Norwich, York and Newcastle when these were established at the beginning of the 18th century.

The Leopard's head hallmark over time

With the exception of Chester and Exeter, both of which offices had already ceased to use the leopard’s head by 1856 and Norwich and Bristol which had gone into decline by then, these towns continued to strike this mark on their plate throughout the 19th century. The last of these was Newcastle which closed its office in 1883.

London continued to use the leopard’s head on both gold and silver of sterling standard into the 20th century and by then was the only office so doing. It was not until 1975 however that they first struck this mark on silver of Britannia standard so that technically it is from that year that the leopard’s head can be truly said to be the London mark although, of course, it can be treated as if it were the London mark for the period between 1300 and 1697 and again between 1883 and 1975. - the author of the information about Leopard's Head is David McKinley.

References

In 1300 King Edward I of England enacted a statute requiring that all silver articles must meet the sterling silver standard (92.5% pure silver) and must be assayed in this regard by 'guardians of the craft' who would then mark the item with a leopard's head.

In 1300 King Edward I of England enacted a statute requiring that all silver articles must meet the sterling silver standard (92.5% pure silver) and must be assayed in this regard by 'guardians of the craft' who would then mark the item with a leopard's head.