October 21 - 27, 2018: Issue 380

Aussie Backyard Bird Count 2018 - Our Annual 'What Bird Is That?' Week Is Here!

Pittwater is one of those places fortunate to have birds that thrive because of an Aquatic environment as much as a tall treed Bush environment and areas set aside for those that dwell closer to the ground, in a coastal scrub earth environment.

You see them along our creeks, on the beaches and foreshores of the lagoon and estuary when they come into rest or nest, and having a quick dip further out on the Pittwater estuary or cavorting in ocean breezes off our coasts. At night you can hear the ‘mopoke’ call of the Nightjars or the calls of Powerful owls. In fact Spring is a great time to hear many a local bird as they call to each other as the new pair up and the old couples feed this year’s newborns. Many a keen birdwatcher finds their birds by song alone.

We see them on our windowsills, we see them perched on wharf posts, amongst seagrass, saltmarsh, and scrub. They feed from the mangroves, intertidal mudflats and native flora. They ensure we don’t get covered by flies each November. They spread seeds for more and more trees.

Some live here year round, others are seasonal visitors. When you find out about their habits and habitats you see they have similarities to the species named 'human' - some pair up for life, build homes at ground level or up high and raise their children together.

There are the shy among them, the garrulous, the fierce, the spectacular to look at and spectacular song imitators such as the Butcher Bird - just as it is among human beings. They do their work, feast on what Nature provides, defend their young with their own lives.

They bring delight to the mind, heart and eye – just by being, by flitting by, by a wink and a nod – by a song that wakes with the earliest part of the day and makes a song rise up in your own heart.

We also have a history of Bird Lovers in living in our area and contributing to the knowledge of Australian Birds, Avalon Beach resident Neville Cayley being one great example. In fact, Mr. Cayley, author of ‘What Bird Is That?’, is a great example of our long love affair with all feathered creatures.

Neville W. Cayley

Above: at 'Ideal View', Marine Parade, Avalon, May 2012, Vera, wife of Neville Cayley (grandson) and sister Joan.

This week the annual Aussie Backyard Bird Count runs from 22-28 October 2018.

The #AussieBirdCount is a great way to connect with the birds in your backyard, no matter where your backyard might be — a suburban backyard, a local park, a patch of forest, a farm, down by the beach, or the main street of town.

To take part all you need is 20 minutes and your favourite outdoor space. Not only will you be contributing to BirdLife Australia's knowledge of Aussie birds, but there are also some great prizes on offer. Head to the website and register as a Counter today!

If you’ve taken part before and are registered for this year why not introduce someone else to the wonderful world of birding through this easy, fun, all-ages event? And if you're a teacher, check out BirdLife Australia's Bird Count curriculum-based lesson plans to get your students (or the whole school!) involved.

If you have questions about the Aussie Backyard Bird Count, please head to BirdLife Australia’s FAQ page, where you’ll find more information about registering, participating, and troubleshooting.

Below run a few of those you may spot this week – our celebrated other local residents and very welcome Summer visitors who bring home the fact that we are very fortunate to live in a place that could well be called 'Birdland'!

Birds That Live On The Ground In The Bush And On The Foreshores And Creeks

A rescued Painted Button-quail - photo by Lynleigh Greig

Painted Button Quail are active during the evening, night and early morning, feeding on the ground. They are usually seen in pairs or small family parties, searching for seeds, fruit, leaves and insects. A ground living in our bush and scrub bird.

Mangrove or Striated Heron Butorides striata - Careel Creek - photo by A J Guesdon

Their breeding habitat is small wetlands in the Old World tropics from west Africa to Japan and Australia, and in South America.

They nest in a platform of sticks measuring between 20–40 cm long and 0.5–5 mm thick. The entire nest measures some 40–50 cm wide and 8–10 cm high outside, with an inner depression 20 cm wide and 4–5 cm deep. It is usually built in not too high off the ground in shrubs or trees but sometimes in sheltered locations on the ground, and often near water.

The Striated Heron is probably the least obtrusive of Australia’s herons. It lives quietly among the mangrove forests, mudflats and oyster-beds of eastern, northern and north-western Australia.

Buff-banded rail Gallirallus philippensis, Careel Creek - photo by A J Guesdon.

A largely terrestrial bird the size of a small domestic chicken, with mainly brown upperparts, finely banded black and white underparts, a white eyebrow, chestnut band running from the bill round the nape, with a buff band on the breast. It utilises a range of moist or wetland habitats with low, dense vegetation for cover. It is usually quite shy.

Dusky Moorhen, Gallinula tenebrosa - in Warriewood wetlands - photo by A J Guesdon

The Dusky Moorhen is found in wetlands, including swamps, rivers, and artificial waterways. It prefers open water and water margins with reeds, rushes and waterlilies, but may be found on grasses close to water such as parks, pastures and lawns.

During breeding season, the Dusky Moorhen forms breeding groups of two to seven birds, with all members defending territory, building nests and looking after young. The shallow platform nests are made of reeds and other water plants over water, among reeds or on floating platforms in open water. Two or more females will lay their eggs in the same nest and all members of the group help to incubate the eggs and feed the young.

Ducklings.

Australian Wood Duck - Male.

Australian Wood Duck - Female. Australian Wood Duck Chenonetta jubata - found at Careel Creek, Careel Bay foreshores, Station Beach (P.B.), Newport Foreshores, etc. etc photos by A J Guesdon

They form monogamous breeding pairs that stay together year round. Nests can be found in tree holes, above or near water, often re-using the same site. These nests are lined with down. The female incubates 9-11 creamy white eggs while the male stands guard.

Eastern Curlew, Numenius madagascariensis at Careel Bay foreshore, Spring, 2011 - photo by A J Guesdon.

Eastern Curlews are the largest of all the world’s shorebirds, and call their call, a mournful ‘Cuuuurrlew’, ringing out beautifully across vast coastal wetlands. Their impressive bill, which is characteristic of the species, is used to probe the mud and dig up crabs, their main food source in Australia.

Sadly, its down-curved shape also mimics the decline of Australia’s migratory shorebirds. The Eastern Curlew occurs only in our flyway, and about 75 per cent of the world’s curlews winter in Australia, so we have a particular responsibility to protect coastal wetlands for them and the smaller shorebirds that live in their shadow.' - BirdLife Australia

Habitat and distribution

The eastern curlew is found on sheltered coasts, mangrove swamps, bays, harbours and lagoons that contain mudflats and sandflats, often with beds of seagrass. At high tide, when their feeding habitat becomes inundated, they move to saltpans, sand dunes and other open areas where they roost above the high water. For this reason, the eastern curlew needs two types of habitat in order to survive, one within the tidal zone, and one above it.

The eastern curlew is found in coastal regions in the north-east and south of Australia, including Tasmania, and is scattered in other coastal areas. On route from their Northern Hemisphere breeding grounds, they are commonly seen in Japan, Korea and Borneo with small numbers visiting New Zealand.

Life history and behaviour

The eastern curlew is a migratory species, moving south by day and night, usually along coastlines, departing breeding areas in the Northern Hemisphere from mid-July to late September. The eastern curlew flies along the East Asian Australasian Flyway arriving in north-western and eastern Australia mostly in August. Large numbers arrive on the east coast from September to November. Most leave again from late February to March.

Commonwealth status: Critically Endangered -

Another now Endangered bird that dwells at our feet with a Pittwater Connection:

DONATIONS TO THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM DURING APRIL, 1855.

A fine specimen of the male gigantic crane, Mycteria Australis, shot at a lagoon, near Pittwater. Mr. George Lamont, Pittwater.DONATIONS TO THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM DURING APRIL, 1855. (1855, May 7). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12968963

DONATIONS TO THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM. JULY, 1855.

A mysteria Australis, or gigantic crane (female), shot at Pittwater-by Mr. George Mills, Bathurst-street. DONATIONS TO THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM. (1855, August 6). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12972574

John Gould MYCTERIA AUSTRALIS: Vol 6 plate 51 of The Birds of Australia. Published date: 1848. Digital ID: IE4644479, courtesy State Library of NSW

One male and one female slaughtered - possibly a breeding pair.

The largest population of this species occurs in Australia, where it is found from the Ashburton River, near Onslow, Western Australia, across northern Australia to north-east New South Wales. It extends inland in the Kimberley area to south of Halls Creek; in the Northern Territory to Hooker Creek and Daly Waters; and in Queensland inland to the Boulia area and the New South Wales border, with some records as far south as the north-west plains of New South Wales, along the coast of Sydney and formerly bred near the Shoalhaven River.

The Shoalhaven River is a perennial river that rises from the Southern Tablelands and flows into an open mature wave dominated barrier estuary near Nowra on the South Coast of New South Wales, Australia.

The combined South and South-east Asian population is placed at less than 1000 birds. A 2011 study found the population in south-western Uttar Pradesh to be stable, although population growth rates may decline with an increase in the number of dry years or land use changes that permanently remove the number of breeding pairs. The Australian population has been optimistically estimated at about 20,000 birds while a more conservative estimate suggests about 10,000 birds. They are threatened by habitat destruction, the draining of shallow wetlands, overfishing, pollution, collision with electricity wires and hunting. Few breeding populations with high breeding success are known primarily due to lack of field work. It is evaluated as near threatened on the IUCN Red List.

The New South Wales Dept. of Environment & Heritage webpages on this magnificent bird (Profile and Listing for being gazetted 'endangered') state:

Conservation status in NSW: Endangered

Gazetted date: 30 Jan 1998 - Profile last updated: 01 Dec 2017

Description

The Black-necked Stork is the only species of stork found in Australia. The distinctive black-and-white waterbird stands an impressive 1.3m tall and has a wingspan of around 2m. The head and neck are black with an iridescent green and purple sheen. The massive bill, short tail and parts of the wings are also black and the long legs are a conspicuous orange-red to bright red. The rest of the body is white. Females have a yellow eye, the males dark-brown. Juvenile birds are generally brown. Black-necked Storks are usually seen singly or in pairs in NSW, occasionally in loose family groups. In flight, they may intersperse their slow, heavy wingbeats with short glides, or soar on thermals. Storks are generally silent.

Distribution

The species Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus comprises two subspecies, E. a. asiaticus in India and south-east Asia, and E. a. australis in Australia and New Guinea. In Australia, Black-necked Storks are widespread in coastal and subcoastal northern and eastern Australia, as far south as central NSW (although vagrants may occur further south or inland, well away from breeding areas). In NSW, the species becomes increasingly uncommon south of the Clarence Valley, and rarely occurs south of Sydney. Since 1995, breeding has been recorded as far south as Buladelah.

Habitat and ecology

- Floodplain wetlands (swamps, billabongs, watercourses and dams) of the major coastal rivers are the key habitat in NSW for the Black-necked Stork. Secondary habitat includes minor floodplains, coastal sandplain wetlands and estuaries.

- Storks usually forage in water 5-30cm deep for vertebrate and invertebrate prey. Eels regularly contribute the greatest biomass to their diet, but they feed on a wide variety of animals, including other fish, frogs and invertebrates (such as beetles, grasshoppers, crickets and crayfish).

- Black-necked Storks build large nests high in tall trees close to water. Trees usually provide clear observation of the surroundings and are at low elevation (reflecting the floodplain habitat).

- In NSW, breeding activity occurs May - January; incubation May - October; nestlings July - January; fledging from September. Parents share nest duties and in one study about 1.3-1.7 birds were fledged per nest.

- The NSW breeding population has been estimated at about 75 pairs. Territories are large and variable in size. They have been estimated to average about 9,000ha, ranging from 3,000-6,000ha in high quality habitat and 10,000-15,000ha in areas where habitat is poor or dispersed.

Black-necked stork - endangered species listing

NSW Scientific Committee - final determination

The Scientific Committee, established under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995, has made a Final Determination to list Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus(Latham, 1790), Black-necked Stork as an ENDANGERED SPECIES in Part 1 of Schedule 1 of that Act and, as a consequence, to omit reference to that species as a vulnerable species from Schedule 2 of that Act.

The Scientific Committee has found that:

1. The Black-necked Stork is a large glossy black and white stork with very long red legs and a large straight black bill. Its core distribution is northern Australia, although it does not occur in enormous numbers anywhere within Australia.

2. In eastern Australia the Black-necked Stork has been recorded as far south as Victoria and inland to the Macquarie Marshes and Griffith. Since European colonisation the range of this species has declined slightly to the north and east. The number of individual birds recorded on the southern and western limits of this range has declined significantly, with only occasional individuals recorded on the South Coast or west of the Great Dividing Range during favourable conditions.

3. Until the 1970s Black-necked Storks bred regularly, although in small numbers, as far south as Shoalhaven Heads. No breeding observations have been recorded south of Port Stephens for a number of years.

4. Black-necked Storks continue to breed in the northern NSW river valleys, however few nests occur within each valley. Most are located in less accessible locations or where disturbance is minimal. The species is thought to have a low tolerance of disturbance.

5. Clearance of remnant vegetation patches and individual trees constitute one of the major threats to the Black-necked Stork in NSW. The difficulty in detecting nests means that some are destroyed before their presence is detected. The scarcity of nest sites has resulted in competition for those that are available with other bird species.

6. Wetland modification also threatens this species and although artificial water sources can provide areas of new habitat these are often suboptimal for the Black-necked Stork.

7. Powerlines constitute a considerable threat to the Black-necked Stork, and several birds are killed or injured as a result of collisions with the lines each year. The few birds actually affected comprise a high percentage of the total population within each river valley.

8. In view of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 & 7 above the Scientific Committee is of the opinion that the Black-necked Stork Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus is likely to become extinct in nature in NSW unless the circumstances and factors threatening its survival cease to operate, and that transfer from Schedule 2 to Part 1 of Schedule 1 is justified.

It was extinct in Pittwater after July 1855; no other records of one, or a pair being sighted, have been found as yet. A pair of these great birds will bond for many years and sometimes may stay together for life. As we humans now know a little more about the breeding cycle of this bird; if the female shot in July 1855 was nesting her eggs would not have hatched, or if there was already one of two chicks in this pairs' nest, they would have starved to death.

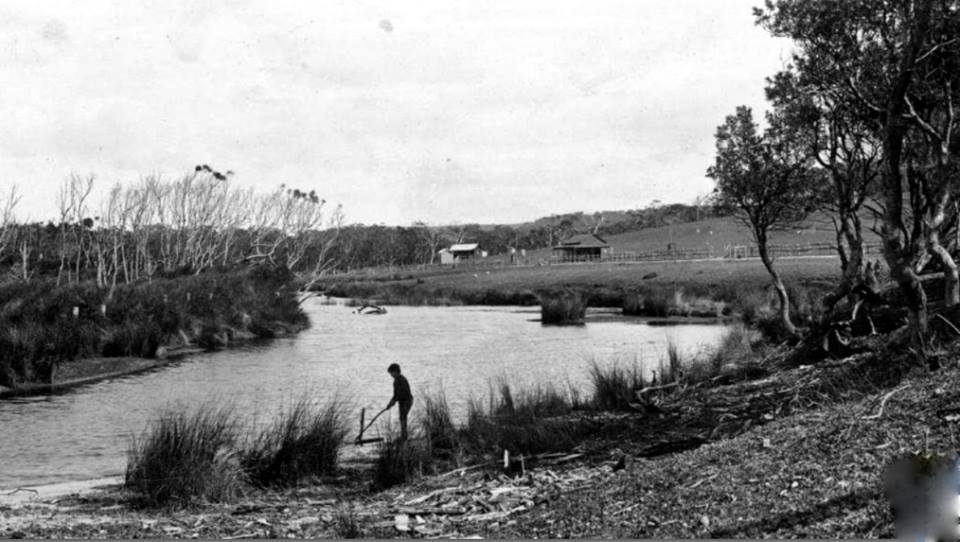

The location of 'a lagoon near Pittwater' is either Narrabeen or perhaps was the verges of Bayview/Winnermerrey when that was still more wetland than filled in land. It may even have been the Black Swamp at Mona Vale, a remnant of which you can see as a bird-attracting pond mid fairway at Mona Vale golf course, or even further along at Newport which also once had its own lagoon. As it was 'near Pittwater' and Narrabeen lagoon was known of by then and named as such, the description points towards water bodies once here that have also, through human design, disappeared from our landscapes.

Farrells Beach and Bungan Head, 1912 - Government Printing Office 1 - 12148. Image No.: d1_12148h, courtesy the State Library of New South Wales.

Adult female in flight at the McArthur River in the Northern Territory of Australia. Photo by and courtesy Djambalawa

by John Shaw Neilson

(FOR MARY GILMORE.)

(FOR MARY GILMORE.)In the far days, when every day was long,

Fear was upon me and the fear was strong,

Ere I had learned the recompense of song.

In the dim days I trembled, for I knew

God was above me, always frowning through,

And God was terrible and thunder-blue.

Creeds the discoloured awed my opening mind,

Perils, perplexities-what could I find?-

All the old terror waiting on mankind.

Even the gentle flowers of white and cream,

The rainbow with its treasury of dream,

Trembled because of God's ungracious scheme.

And in the night the many stars would say

Dark things unaltered in the light of day;

Fear was upon me ever in my play.

There was a lake I loved in gentle rain;

One day there fell a bird, a courtly crane;

Wisely he walked, as one who knows of pain.

Gracious he was and lofty as a king;

Silent he was, and yet he seemed to sing

Always of little children and the Spring.

God? Did he know him? It was far he flew-

God was not terrible and thunder-blue;-

It was a gentle water-bird I knew.

Pity was in him for the weak and strong,

All who have suffered when the days were long,

And he was deep and gentle as a song.

As a calm soldier in a cloak of grey

He did commune with me for many a day

Till the dark fear was lifted far away.

Sober-apparelled, yet he caught the glow;

Always of heaven would he speak, and low,

And he did tell me where the wishes go.

Kinsfolk of his it was who long before

Came from the mist (and no one knows the shore)

Came with the little children to the door.

Was he less wise than those birds long ago

Who flew from God (He surely willed it so)

Bearing great happiness to all below?

Long have I learned that all his speech was true:

I cannot reason it-how far he flew

God is not terrible nor thunder-blue.

Sometimes, when watching in the white sunshine,

Someone approaches-I can half define

All the calm beauty of that friend of mine.

Nothing of hatred will about him cling,

Silent-how silent-but his heart will sing

Always of little children and the Spring.

SHAW NEILSON.

THE GENTLE WATER BIRD. (1926, April 10). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28060046

Birds That Live Up High

Nankeen Kestral, Falco cenchroides - photo by A J Guesdon.

Laughing Kookaburra, Dacelo novaeguineae, Halcyonidae - photo by A J Guesdon.

Dollarbird, Eurystomus orientalis - photo by A J Guesdon

The origin of the Dollardbird's name stems from the silvery, circular patches on the underside of the wings, thought to resemble the American silver dollar coin. The Dollarbird, Eurystomus orientalis, is the sole Australian representative of the Roller family, so named because of their rolling courtship display flight. The Dollarbird visits Australia each year to breed. It has mostly dark brown upperparts, washed heavily with blue-green on the back and wing coverts. The breast is brown, while the belly and undertail coverts are light, and the throat and undertail glossed with bright blue. The flight feathers of the wing and tail are dark blue. The short, thick-set bill is orange-red, tipped with black. In flight, the pale blue coin-shaped patches towards the tips of its wings, that gave the bird its name, are clearly visible. Both sexes are similar, although the female is slightly duller. Young Dollarbirds are duller than the adults and lack the bright blue gloss on the throat. The bill and feet are brownish in colour instead of red. The distinctive, harsh 'kak-kak-kak' call is repeated several times, and is often given in flight.

Juvenile White-bellied Sea Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster - at Church Point - photo by A J Guesdon

Glossy black-cockatoos are one of the more threatened species of cockatoo in Australia and are listed as a vulnerable in NSW.

The glossy black-cockatoo lives in coastal woodlands and drier forest areas, open inland woodlands, or timbered watercourses where its main food source, the casuarina (she-oak) is common.

The glossy black-cockatoo has a patchy distribution in Australia, having once been widespread across most of the south-eastern part of the country. It is now distributed throughout an area which extends from the coast near Eungella in eastern Queensland to Mallacoota in Victoria. An isolated population of glossy black-cockatoos is also known to live on Kangaroo Island in South Australia. The species has become regionally extinct in parts of western Victoria and south-eastern South Australia.

What you can do to help glossy black-cockatoos

- As the glossy black-cockatoo feeds mostly on casuarinas and nests in eucalypts, try to retain existing stands of casuarina/eucalypt and extend this habitat where possible.

- Many casuarinas and eucalypts have previously been removed due to land clearing, for grazing and crops. Try to encourage regeneration and re-establish stands of casuarinas and eucalypts. Casuarinas and other suitable trees can also be planted in rural areas and on urban fringes to provide feeding habitat and breeding sites.

- As the glossy black-cockatoo nests in both living and dead trees, removing dead trees for firewood and other uses is harmful. Glossy black-cockatoos cannot nest without suitable tree hollows. Consider using fallen, dry, green wood and allocate areas for wood collection on your property.

- Watch out for suspicious situations which may indicate illegal trapping or poaching. If you suspect any illegal activities, report them to Wildlife Watch, freecall 1800 819 375.

- If you find an injured or displaced glossy black-cockatoo, contact your local OEH office or a registered wildlife rehabilitation group as soon as possible.

- Don't let your pets wander unsupervised at night. Domestic dogs and cats can kill glossy black-cockatoos.

From/By NSW Office of Environment and Heritage

Birds That Live In The Low Scrub And Bushes

Willy Wagtail Rhipidura leucophrys

Willy Wagtail, Rhipidura leucophrys, lives at Careel Bay Playing Fields photo by A J Guesdon

One of the most delightful birdsongs you hear when strolling over the green open spaces or alongside the creeks of Pittwater is that of the Willy Wagtail. They can sometimes get quite noisy, especially this time of the year as they head into their breeding season, when disputes over territory, from which humans are not immune, cause their sweet twitters to get a little more raucous, insistent and even scolding. When not scolding they have a pleasant melodious range of songs communicating or calling to their mate. In his book What Bird is That?(1935), Neville Cayley writes that it has "a pleasant call resembling sweet pretty little creature, frequently uttered during the day or night, especially on moonlight nights"

Willie Wagtails are found in most open habitats, especially open forests and woodlands, tending to be absent from wet sclerophyll forests and rainforests. They are often associated with water-courses and wetlands.

The Willie Wagtail's nest is a neatly woven cup of grasses, covered with spider's web on the outside and lined internally with soft grasses, hair or fur. The soft lining of the nest, if not readily available, is often taken directly from an animal. The nest of the Willie Wagtail may be re-used in successive years, or an old nest is often destroyed and the materials used in the construction of a new nest. Nests are normally placed on a horizontal branch of a tree, or other similar structure. - BirdLife Australia

Brown Thornbill, Acanthiza pusilla - Careel Creek where trees/green has been restored through Bush Regeneration works - A J Guesdon photo

The Brown Thornbill (Acanthiza pusilla) is a passerine bird usually found in eastern and south-eastern Australia, including Tasmania. It can grow up to 10 cm long, and feeds on insects but may sometimes eat seeds, nectar or fruit. They feed, mainly in pairs, at all levels from the ground up, but mostly in understorey shrubs and low trees. Will feed in mixed flocks with other thornbills out of breeding season.

Breeding pairs of Brown Thornbills hold territories all year round for feeding and breeding purposes, and the bonds between pairs are long-lasting. Their breeding season last from July to January. Females build a small oval, domed nest with a partially hooded entrance near the top out of grasses, bark and other materials, lining it with feathers, fur or soft plant down. The nest is usually low down, in low, prickly bushes, grass clumps, or ferns. The female incubates the eggs, usually 2-4, and both parents feed the young, who stay with the parents until early autumn, before being driven out of the parental territory.

Variegated Fairy-wren, Malurus lamberti, - male with breeding plumage - Bangalley Headland. Photo by A J Guesdon

Variegated Fairy-wren, Malurus lamberti, - female - Bangalley Headland. Photo by A J Guesdon

Found in forest, woodland and shrub land habitats.

The male Variegated Fairy-wren is often mistakenly believed to have a harem of females. The small groups actually consist of an adult female with younger or non-breeding birds. As they have a wide range, Variegated Fairy-wrens have been recorded breeding in almost every month of the year. The nest is an oval-shaped dome, constructed of grasses, and placed in a low shrub.

Birds That Live On Our Beaches, Creek Waters, Lagoon And Aquatic Rockshelfs

Sooty oystercatcher Haematopus fuliginosus - Narrabeen rockshelf - photo by A J Guesdon

The sooty oystercatcher forages in the intertidal zone, for the two hours either side of low tide. A field study published in 2011 showed that prey items differed markedly between the sexes with only a 36% overlap. Females focussed on soft-bodied prey which they could swallow whole such as fish, crabs, bluebottle jellyfish and various worm-like creatures such as cunjevoi, while males preferred hard-shelled prey such as mussels (Mytilus planulatus), sea urchins, turban shells (Turbo undulatus and Turbo torquata), and black periwinkle (Nerita atramentosa).

A clutch of two to three eggs is laid in a crevice in rocks or small hollow or flat on the ground, often on an island or high place where parent birds can keep watch.

Conservation status in NSW: Vulnerable

Australasian Darter, Anhinga novaehollandiae, (Snake Bird), Narrabeen Lagoon (near the main bridge) - photo by A J Guesdon.

The Darter is found in wetlands and sheltered coastal waters, mainly in the Tropics and Subtropics. It prefers smooth, open waters, for feeding, with tree trunks, branches, stumps or posts fringing the water, for resting and drying its wings. Most often seen inland, around permanent and temporary water bodies at least half a metre deep, but may be seen in calm seas near shore, fishing. The Darter is not affected by salinity or murky waters, but does require waters with sparse vegetation that allow it to swim and dive easily. It builds its nests in trees standing in water, and will move to deeper waters if the waters begin to dry up. - BirdLife Australia

Chestnut teal - Anas castanea - Warriewood Wetland, Station Beach, Careel Creek and Careel Bay foreshore - photo by A J Guesdon

Great egret Ardea alba and Royal spoonbill Platalea regia - photo by A J Guesdon

This Royal Spoonbill (below) spotted in Careel Creek in September 2018 displays the signs of being in its breeding season.

The Royal Spoonbill (Platalea regiais) is a large white waterbird with black, spatulate (spoon-shaped) bill, facial skin, legs and feet. During the breeding season, it has a distinctive nuchal (back of head or nape of neck) crest, which can be up to 20 cm long in male birds (usually shorter in females). The crest can be erected during mating displays to reveal bright pink skin underneath. Breeding adults also have a creamy-yellow wash across the lower neck and upper breast and a strip of bright pink skin along the edge of the underwings which is obvious when the bird opens its wings. The facial skin is black with a yellow patch above the eye and a red patch in the middle of the forehead, in front of the crest feathers.

The Royal Spoonbill is found in shallow freshwater and saltwater wetlands, intertidal mud flats and wet grasslands.

The Royal Spoonbill forms monogamous pairs for the duration of the breeding season and nest in colonies alongside many other waterbirds, including Yellow-billed Spoonbills, ibises, herons and cormorants. A solid bowl-shaped nest is built of sticks and twigs lined with leaves and water plants, and is usually placed in the crown of a tree over water or among high reeds and rushes. Nest sites may be reused year after year. Both sexes incubate the eggs and feed the young. When threatened at the nest, the adult birds will raise all their feathers to appear much larger and crouch down low over the nest. The young are often fed by both parents for several weeks after fledging and young birds will forage alongside their parents for some time before the family group disperses. - BirdLife Australia

Be great if we could all be a bit mindful that we live in an environment populated with other animals of the furred, feathered and scaled kind this season and give them a bit of space and respect.

Great Egret – Ardea alba - fishing at Careel Creek - photo by A J Guesdon

Black Swans, Cygnus atratus, on Narrabeen Lagoon - Photos by Michael Mannington, Volunteer Phootgraphy.