Monitoring the Common Murre Mass Mortality in Coastal Alaska

by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Sentinels of ocean health: counting a climate catastrophe

Common murres help us understand the health of Alaska's marine ecosystems – and sound a warning when there is trouble below the waves.

Murres are especially sensitive to changes in their food supply because they must eat a significant portion of their body weight each day to survive and respond quickly to changes in food availability. These seabirds dive up to 200 meters deep to catch small schooling fish like capelin and sand lance. When schooling fish become scarce or scattered, common murres struggle to meet their high energy demands, making them good indicators of broader changes in ocean conditions.

Working with partners, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, has recently published a comprehensive study of the Alaska death toll in common murres that resulted from a significant marine heatwave in 2014-16.

Through an analysis of long-term monitoring data covering two large Alaska ecosystems, we found that the mass mortality event was several times greater than initially estimated. About half of Alaska’s common murre population – around four million birds – perished, the largest single-species wildlife die-off ever documented in modern history.

This is the first study to show that the impacts of rising temperatures, due to climate change , can be swift, intense, and long-lasting, with no recovery in sight and potentially permanent ecosystem changes.

A common murre feeds a small fish to a chick. Photo By/Credit: Cornelius Nelo Schlawe/USFWS

Documenting an unprecedented event

A healthy murre colony overwhelms the senses. Thousands of black-and-white bodies crowd the cliffs, their constant cooing and grumbling creating a wall of sound. Birds move continuously — flying to and from fishing grounds, trading nest duties with mates, or bringing fish to chicks. But during the summers of 2015 and 2016, these typically bustling cliffs fell eerily quiet.

In late 2014, a major marine heatwave—a period of abnormally warm ocean temperatures—began in Alaska's waters. Known as “The Blob,” this warming persisted for two years, disrupting marine food webs. The impact became visible as more than 62,000 emaciated common murre carcasses washed ashore from California to Alaska – most washing up within the Gulf of Alaska. At the same time, biologists also recorded severely reduced numbers at every nesting colony they visited across the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea, including 22 complete reproductive failures at colony sites between 2015 and 2017.

Biologists could only guess whether the birds had died, relocated, or simply lacked the energy to breed. In the years immediately following the heatwave, the murres did return and began to breed again – but in much lower numbers.

Studies show that only a fraction of birds that die at sea typically wash ashore. Biologists estimated in a 2020 paper that total mortality from the heatwave was 500,000 to approaching 1 million birds.

“We knew right away this was a big, unprecedented die-off,” says Heather Renner, supervisory biologist, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. “However, we had no confident way to make a final estimate based on the carcasses alone. We needed colony population count data over several years to be able to determine how many birds were really lost.”

*Read more: "Extreme Mortality and Reproductive Failure of Common Murres Resulting from the Northeast Pacific Marine Heatwave of 2014-2016." PLOS ONE 15, no. 1 (January 15, 2020).

The network of warning signs

The staff at Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge work with partners to maintain a seabird monitoring network with more than 50 years of continuous data collection. Together, these sites span colonies ranging from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of birds across an enormous geographical area. This baseline data allows us to assess fluctuations as normal or unusual, and proved critical in understanding the dramatic loss of common murres.

In the years before the heatwave, common murre populations increased at some colonies and decreased at others. During the heatwave, all colonies suffered major losses. It was a remarkably clear, consistent signal at all monitored colonies within both the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea ecosystems.

In subsequent years, information collected by the monitoring network suggested that something fundamental had changed for common murres, and perhaps for the larger ecosystem.

Before and after comparison of a common murre colony in the Semidi Islands. The top photo shows the colony in 2014, the bottom photo shows the colony in 2021. Photo By/Credit: USFWS

Missing murres: studying the impacts

“We were waiting for the birds to show back up.” Heather Renner

During the seven years of monitoring after the heatwave, biologists expected to see some recovery for the murres as ocean conditions stabilised and nest success could improve. Instead, their numbers have remained far lower than before across all colonies.

In response to the continued low populations at all of the known monitoring sites, refuge staff began working with a team of collaborators to analyse the monitoring data collected over the past 14 years. Research collaborators included:

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Region Inventory and Monitoring Program

- University of Washington

- U.S. Geological Survey

- Tern Again Consulting

The team looked at data from 13 colony sites spread over two large ecosystems in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea. Monitoring and data collection contributors included:

- Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge

- Alaska Peninsula and Becharof National Wildlife Refuges

- Togiak National Wildlife Refuge

- Round Island, monitored by the State of Alaska, Department of Fish and Game

- Middleton Island, supported by GulfWatch and the Institute for Seabird Research and Conservation

A climate tragedy emerges: four million murres lost

This research and analysis, recently published in the journal, Science, in December 2024 as "Catastrophic and persistent loss of common murres after a marine heatwave," details the full extent of the loss, a mortality four to eight times worse than the initial estimate.

About half of Alaska’s common murre population – around four million birds – died during the marine heatwave.

To understand the magnitude of this event: the murre die-off was approximately fifteen times larger than the number of seabirds killed during the Exxon Valdez oil spill, making it the largest single-species wildlife die-off ever documented.

This is the first study to show that impacts of rising temperatures, due to climate change, can be swift, intense, and long-lasting, with no recovery in sight and potentially permanent ecosystem changes. The sustained reduction in murre populations suggests a fundamental shift in carrying capacity—the ability to support healthy seabird populations. Smaller murre colonies may now face increased vulnerability to predators and environmental stresses, further complicating their recovery.

Common murre with a small fish perched with other murres on a cliff ledge. Photo By/Credit: Brie Drummond/USFWS

Falling dominoes: disrupting the marine ecosystem

The murre die-off was part of a larger disruption in the marine food web. Pacific cod populations crashed by 80%, leading to fishery closures, while other forage fish like capelin—a crucial prey species—declined dramatically. These cascading effects rippled through the ecosystem, impacting both wildlife and the fishing communities that depend on healthy marine resources.

For Alaska Native communities, massive die-offs like this one may also disrupt a centuries-old cultural relationship with marine life. Murres have traditionally been an important subsistence resource in many coastal communities, both for meat and eggs, making their sustained low numbers a potential challenge for traditional harvesting practices and cultural connections.

However, the monitoring data also showed that some marine species, such as thick-billed murres, were more resilient during the die-off. The 2024 study theorizes that the heatwave affected the food web at pinch points critical to some species, rather than impacting all marine life consistently.

Looking Forward

The lasting loss of Alaska's common murres demonstrates both the vulnerability of marine ecosystems, due to climate change, and the critical importance of long-term monitoring in understanding these changes.

Species populations naturally fluctuate over time. Our 50-year dataset allows us to distinguish between normal variations and significant changes that require action. While long-term monitoring may have long gaps between major discoveries like this one, without it, these critical ecological changes might go undetected and unexplained.

The refuge staff will continue to work with partners to maintain the long-term monitoring for key seabird species across coastal Alaska. With this information, we can provide:

- Early warning of marine ecosystem changes

- Data for wildlife management decisions

- Understanding of climate impacts on marine systems

- Support for coastal community planning

- Context for fisheries management

Through careful and rigorous analysis of monitoring information, such as the recent study documenting the murre die-off, we strive to better understand and protect the ocean ecosystems that support both wildlife and human communities.

More about common murres

Monitoring:

During the summer months, common murres nest directly on cliff ledges, laying distinctively pointed eggs that resist rolling off—often alongside thick-billed murres and other seabird species. Common murres are ideal for long-term monitoring because they return to the same nesting sites each year and can be studied across an enormous geographic range. They are the only seabird species we can consistently monitor at all of our refuge study sites, making them invaluable for understanding broad-scale changes in ocean conditions.

Our core sites:

Eight long-term seabird monitoring locations across the expanse of the refuge, staffed seasonally by 2-3 field researchers who conduct systematic data collection over 3.5-month periods each summer. To monitor common murres, teams follow nest statuses and conduct counts on designated cliff plots using binoculars and spotting scopes throughout breeding season. They document population numbers, reproductive timing, nest survival rates, and chick diet composition.

Extended Network:

The refuge also conducts shorter boat-based surveys intermittently at 10-15 additional locations interspersed between long-term monitoring sites throughout the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea.

More about the 2014-16 marine heatwave event:

The 2014-2016 marine heat wave was an underwater heat dome—a vast area of unusually warm ocean temperatures that broke records dating back three decades. It was like having a heatwave on land that covered the entire West Coast and lasted for two years without reprieve. As climate change progresses, these marine heatwaves will likely increase in frequency, duration, and intensity.

_________________________________

Related: Shearwaters washing up on local beaches for third year in a row: Mass mortalities of Starving Birds attributed to Australia's Lose-Lose Policy on the Australian Environment - October 2024, Issue 636 of Pittwater Online News

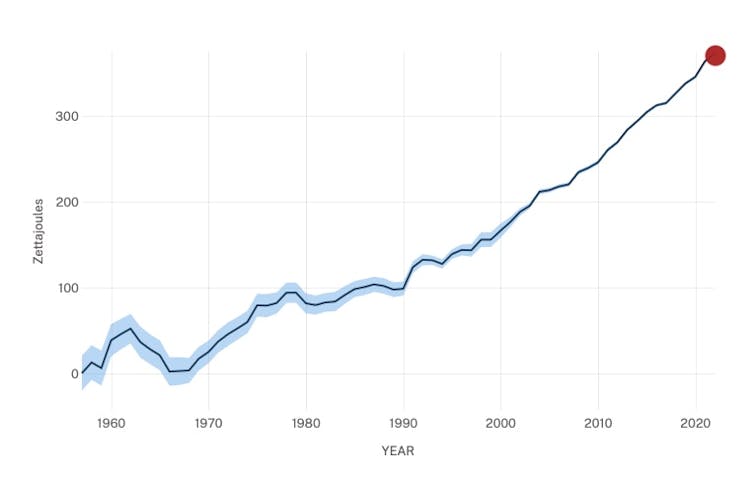

Cheeseman T, Barlow J, Acebes JM, Audley K, Bejder L, Birdsall C, Bracamontes OS, Bradford AL, Byington J, Calambokidis J, Cartwright R, Cedarleaf J, Chavez AJG, Currie J, De Castro RC, De Weerdt J, Doe N, Doniol-Valcroze T, Dracott K, Filatova O, Finn R, Flynn KR, Ford J, Frisch-Jordán A, Gabriele C, Goodwin B, Hayslip C, Hildering J, Hill MC, Jacobsen JK, Jiménez-López ME, Jones M, Kobayashi N, Lammers M, Lyman E, Malleson M, Mamaev E, Loustalot PM, Masterman A, Matkin CO, McMillan C, Moore J, Moran J, Neilson JL, Newell H, Okabe H, Olio M, Ortega-Ortiz CD, Pack AA, Palacios DM, Pearson H, Quintana-Rizzo E, Barragán RR, Ransome N, Rosales-Nanduca H, Sharpe F, Shaw T, Southerland K, Stack S, Staniland I, Straley J, Szabo A, Teerlink S, Titova O, Urban-Ramirez J, van Aswegen M, Vinicius M, von Ziegesar O, Witteveen B, Wray J, Yano K, Yegin I, Zwiefelhofer D, Clapham P. Bellwethers of change: population modelling of North Pacific humpback whales from 2002 through 2021 reveals shift from recovery to climate response. Royal Society Open Science. 2024 Feb 28;11(2):231462. doi: 10.1098/rsos.231462. PMID: 38420629; PMCID: PMC10898971.

![]()