The first modern, self-igniting match was invented in 1805 by Jean Chancel, assistant to Professor Louis Jacques Thénard of Paris. The head of the match consisted of a mixture of potassium chlorate, sulfur, sugar, and rubber. The match was ignited by dipping its tip in a small asbestos bottle filled with sulfuric acid. This kind of match was quite expensive, however, and its usage was also relatively very dangerous, so Chancel's matches never really became widely adopted or in commonplace use.

This approach to match making was further refined in the proceeding decades, culminating with the 'Promethean Match' that was patented by Samuel Jones of London in 1828. His match consisted of a small glass capsule containing a chemical composition of sulfuric acid colored with indigo and coated on the exterior with potassium chlorate, all of which was wrapped up in rolls of paper. The immediate ignition of this particular form of a match was achieved by crushing the capsule with a pair of pliers, mixing and releasing the ingredients in order for it to become alight.

In 1832, William Newton patented the "wax vesta" in England. It consisted of a wax stem that embedded cotton threads and had a tip of phosphorus. Variants known as "candle matches" were made by Savaresse and Merckel in 1836. John Hucks Stevens also patented a safety version of the friction match in 1839.

Friction or Chemical matches were unable to make the leap into mass production, due to the expense, their cumbersome nature and inherent danger. An alternative method was to produce the ignition through friction produced by rubbing two rough surfaces together. An early example was made by François Derosne in 1816. His crude match was called a briquet phosphorique and it used a sulfur-tipped match to scrape inside a tube coated internally with phosphorus. It was both inconvenient and unsafe.

The first successful friction match was invented in 1826 by English chemist John Walker, a chemist and druggist from Stockton-on-Tees, County Durham. He developed a keen interest in trying to find a means of obtaining fire easily. Several chemical mixtures were already known which would ignite by a sudden explosion, but it had not been found possible to transmit the flame to a slow-burning substance like wood. While Walker was preparing a lighting mixture on one occasion, a match which had been dipped in it took fire by an accidental friction upon the hearth. He at once appreciated the practical value of the discovery, and started making friction matches. They consisted of wooden splints or sticks of cardboard coated with sulphur and tipped with a mixture of sulphide of antimony, chlorate of potash, and gum. The treatment with sulphur helped the splints to catch fire, and the odor was improved by the addition of camphor.

The price of a box of 50 matches was one shilling. With each box was supplied a piece of sandpaper, folded double, through which the match had to be drawn to ignite it. He named the matches "Congreves" in honour of the inventor and rocket pioneer, Sir William Congreve. He did not divulge the exact composition of his matches. Between 1827 and 1829, Walker made about 168 sales of his matches. It was however dangerous and flaming balls sometimes fell to the floor burning carpets and dresses, leading to their ban in France and Germany. Walker either did not consider his invention important enough to patent or neglected it.

In 1829, Scots inventor Sir Isaac Holden invented an improved version of Walker's match and demonstrated it to his class at Castle Academy in Reading, Berkshire. Holden did not patent his invention and claimed that one of his pupils wrote to his father Samuel Jones, a chemist in London who commercialised his process. A version of Holden's match was patented by Samuel Jones, and these were sold as lucifer matches. These early matches had a number of problems - an initial violent reaction, an unsteady flame and unpleasant odor and fumes. Lucifers could ignite explosively, sometimes throwing sparks a considerable distance. Lucifers were manufactured in the United States by Ezekial Byam. The term "lucifer" persisted as slang in the 20th century (for example in the First World War song Pack Up Your Troubles) and matches are still called lucifers in Dutch.

Lucifers were however quickly replaced after 1830 by matches made according to the process devised by Frenchman Charles Sauria who substituted the antimony sulfide with white phosphorus. These new phosphorus matches had to be kept in airtight metal boxes but became popular. In England, these phosphorus matches were called "Congreves" after Sir William Congreve while they went by the name of loco foco in the United States.

From 1830 to 1890, the composition of these matches remained largely unchanged, although some improvements were made. In 1843 William Ashgard replaced the sulfur with beeswax, reducing the pungency of the fumes. This was replaced by paraffin in 1862 by Charles W. Smith, resulting in what were called "parlor matches". From 1870 the end of the splint was fireproofed by impregnation with fire-retardant chemicals such as alum, sodium silicate, and other salts resulting in what was commonly called a "drunkard's match" that prevented the accidental burning of the user's fingers. Other advances were made for the mass manufacture of matches. Early matches were made from blocks of woods with cuts separating the splints but leaving their bases attached. Later versions were made in the form of thin combs. The splints would be broken away from the comb when required.

Those involved in the manufacture of the new phosphorus matches were afflicted with phossy jaw and other bone disorders, and there was enough white phosphorus in one pack to kill a person. Deaths and suicides from eating the heads of matches became frequent. The earliest report of phosphorus necrosis was made in 1845 by Lorinser in Vienna, and a New York surgeon published a pamphlet with notes on nine cases.

The

conditions of working class women at the Bryant & May factories led to the

London matchgirls strike of 1888. The strike was focused on the severe health complications of working with white phosphorus, such as

phossy jaw. Social activist

Annie Besant published an article in her halfpenny weekly paper

The Link on 23 June 1888. A strike fund was set up and some newspapers collected donations from readers. The women and girls also solicited contributions. Members of the Fabian Society, including George Bernard Shaw, Sidney Webb, and Graham Wallas, were involved in the distribution of the cash collected. The strike and negative publicity led to changes being made to limit the health effects of the inhalation of white phosphorus.

Photo of matchgirls participating in a strike against Bryant & May, London 1888

Bryant and May's take on this:

Bryant and May's Matches.

At the fifth annual meeting of Messrs. Bryant and May (Limited), the report submitted to the shareholders showed that the net profit amounted to £72,794. The directors recommended a further dividend of 10s per share, which, with that already paid made 17 per cent. for the year. Mr. W. Bryant, in moving the adaption of the report, stated that in the middle of the year they were annoyed by outsiders with reference to their work people, which for a time dieorganised the works, involving extra worry to the management, and causing a slight. diminution of business. Matters were now settling down, and there was very little at the present time to complain of...would take that opportunity of repeating that the women employed by them received 16, to 25 per cent. more wages than the same class of hands could earn in other factories in East London on similar kind of work. He had been told by a gentleman who was acquainted with the operatives of the north of England, that the money Bryant and May's hands received was at least 10 percent, higher than the same class of hands got in several of the large towns in the north of England. The report was adopted.

It's worth noting that, according to some reports, if the operatives worked form 5 a.m. until midnight 7 days a week they could earn between 5 and 7 shillings - those 'others in other factories' - 16 to 25% less.

The 'annoyance' persisted:

MORE ABOUT ' PHOSSY JAW.'' Bryant and May's Matches.

The intelligence that Bryant and May, the big London match-making firm, have been recently fined heavily for not reporting cases of phosphorous poisoning calls to mind once more the terrible lives led by the poor match girls of London. In this instance 11 cases of poisoning were hidden from the authorities, and the poor tortured victims bribed into silence. Unfortunately it pays Bryant and May to pay the fines and continue the poisoning, for the smoker wants his wax vestas, and does not stop to consider the cost to the white slaves who furnish them. Ignorance is responsible for most of the trouble. The general public are unaware of the terrible risks run by the operatives. But as a matter of fact the girls and women directly engaged in the manufacture of ordinary matches are practically certain to become sooner or later victims of a loathsome form of leprosy, known as "phossy jaw,'' phosphor poisoning or necrosis. Most frequently it attacks the jaw— first, the teeth decay and fall out, then, it proceeds to honeycomb the jawbone till it can be taken away in pieces. If the lower jawbone is not surgically removed, the hideous leprosy travels to the upper jaw, and the victim is doomed. The next dread step is a discharging wound under the eye, which soon destroys the sight, and ultimately, after a season of purgatory, kills the poor sufferer. The most appalling feature of the scourge is the loathsome stench, which makes it impossible for any other person to occupy; the same room.

As ' safety' matches are made of red phosphorus, which carries with it no danger from this dread disease, the public have the opportunity of doing a little towards putting a stop to this cruelty by refusing to use wax vestas, 'wait-a-bits,' or any free matches, confining themselves to the harmless 'safties.' Safe to the maker and to the user. MORE ABOUT "PHOSSY JAW." (1898, June 23). The Tocsin (Melbourne, Vic. : 1897 - 1906), p. 6. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197530452

Attempts were made to reduce the ill-effects on workers through the introduction of inspections and regulations. Anton Schrötter von Kristelli discovered in 1850 that heating white phosphorus at 250 °C in an inert atmosphere produced a red allotropic form, which did not fume in contact with air. Arthur Albright developed the industrial process for large-scale manufacture of red phosphorus after Schrötter’s discoveries became known. By 1851, his company was producing the substance by heating white phosphorus in a sealed pot at a specific temperature. He exhibited his red phosphorus in 1851, at The Great Exhibition in London. It was suggested that this would make a suitable substitute in match manufacture although it was slightly more expensive. Two French chemists, Henri Savene and Emile David Cahen, proved in 1898 that the addition of phosphorus sesquisulfide meant that the substance was not poisonous, that it could be used in a "strike-anywhere" match, and that the match heads were not explosive.

British company Albright and Wilson, was the first company to produce phosphorus sesquisulfide matches commercially. The company developed a safe means of making commercial quantities of phosphorus sesquisulfide in 1899 and started selling it to match manufacturers.White phosphorus however continued to be used, and its serious effects led many countries to ban its use.

Finland prohibited the use of white phosphorus in 1872, followed by Denmark in 1874, France in 1897, Switzerland in 1898, and the Netherlands in 1901. An agreement, the Berne Convention, was reached at Bern, Switzerland, in September 1906, which banned the use of white phosphorus in matches. This required each country to pass laws prohibiting the use of white phosphorus in matches. The United Kingdom passed a law in 1908 prohibiting its use in matches after 31 December 1910. The United States did not pass a law, but instead placed a "punitive tax" in 1913 on white phosphorus–based matches, one so high as to render their manufacture financially impractical, and Canada banned them in 1914. India and Japan banned them in 1919; China followed, banning them in 1925.

The dangers of white phosphorus in the manufacture of matches led to the development of the "hygienic" or safety match. The major innovation in its development was the use of red phosphorus, not on the head of the match but instead on a specially designed striking surface.

The idea of creating a specially designed striking surface was developed in 1844 by the Swede Gustaf Erik Pasch. Pasch patented the use of red phosphorus in the striking surface. He found that this could ignite heads that did not need to contain white phosphorus. Johan Edvard and his younger brother Carl Frans Lundström (1823–1917) started a large-scale match industry in Jönköping, Sweden around 1847, but the improved safety match was not introduced until around 1850–55. The Lundström brothers had obtained a sample of red phosphorus matches from Arthur Albright at The Great Exhibition, held at The Crystal Palace in 1851, but had misplaced it and therefore they did not try the matches until just before the Paris Exhibition of 1855 when they found that the matches were still usable. In 1858 their company produced around 12 million matchboxes.

Jönköpings safety match industry 1872 - sv:Jönköping Tändsticksfabriks AB, lithography from 1872.

Some sources state British match manufacturer Bryant and May visited Jönköping in 1858 to try to obtain a supply of safety matches, but it was unsuccessful. In 1862 it established its own factory and bought the rights for the British safety match patent from the Lundström brothers. The persistence of making and selling of the other product, which killed, is ascribed to pursuit of higher profits by some historians.

The safety of true "safety matches" is derived from the separation of the reactive ingredients between a match head on the end of a paraffin-impregnated splint and the special striking surface (in addition to the safety aspect of replacing the white phosphorus with red phosphorus). The idea for separating the chemicals had been introduced in 1859 in the form of two-headed matches known in France as Allumettes Androgynes. These were sticks with one end made of potassium chlorate and the other of red phosphorus. They had to be broken and the heads rubbed together. There was however a risk of the heads rubbing each other accidentally in their box. Such dangers were removed when the striking surface was moved to the outside of the box. The development of a specialised matchbook with both matches and a striking surface occurred in the 1890s with the American Joshua Pusey, who sold his patent to the Diamond Match Company.

The striking surface on modern matchboxes is typically composed of 25% powdered glass or other abrasive material, 50% red phosphorus, 5% neutralizer, 4% carbon black, and 16% binder; and the match head is typically composed of 45–55% potassium chlorate, with a little sulfur and starch, a neutralizer (ZnO or CaCO3), 20–40% of siliceous filler, diatomite, and glue. Some heads contain antimony(III) sulfide to make them burn more vigorously. Safety matches ignite due to the extreme reactivity of phosphorus with the potassium chlorate in the match head. When the match is struck the phosphorus and chlorate mix in a small amount forming something akin to the explosive Armstrong's mixture which ignites due to the friction.

The Swedes long held a virtual worldwide monopoly on safety matches, with the industry mainly situated in Jönköping, by 1903 called Jönköpings & Vulcans Tändsticksfabriks AB. In France, they sold the rights to their safety match patent to Coigent Père & Fils of Lyon, but Coigent contested the payment in the French courts, on the basis that the invention was known in Vienna before the Lundström brothers patented it.

WOODEN MATCHES.

NEW AUSTRALIAN INDUSTRY.

BRYANT AND MAYS TO START.

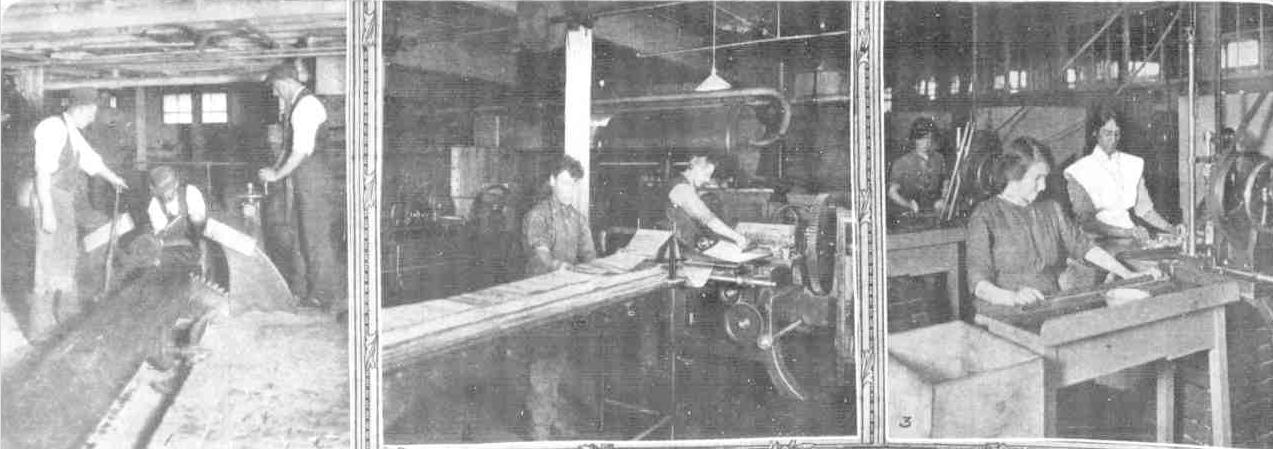

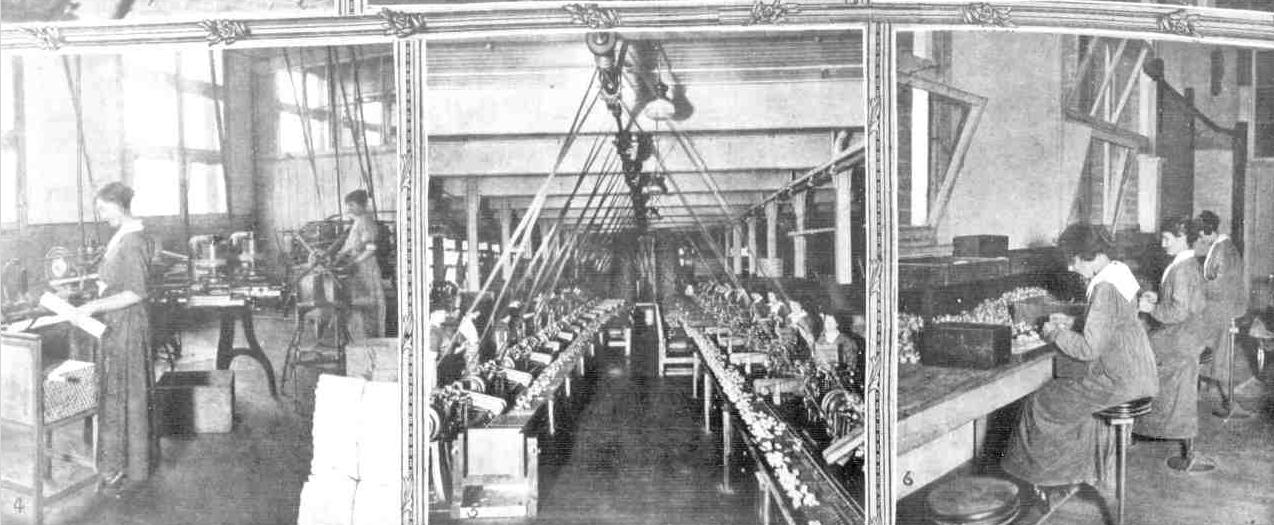

The great English firm of Bryant and Mays, match-makers, are to begin manufacturing la Melbourne. Mr. Bartholomew, one of the directors, who passed through Sydney yesterday, said that tho architect was now at work, and they hoped to begin building In March. The first wooden safety matches ever made in Australia would probably be manufactured about the end of the year or the beginning of 1910.

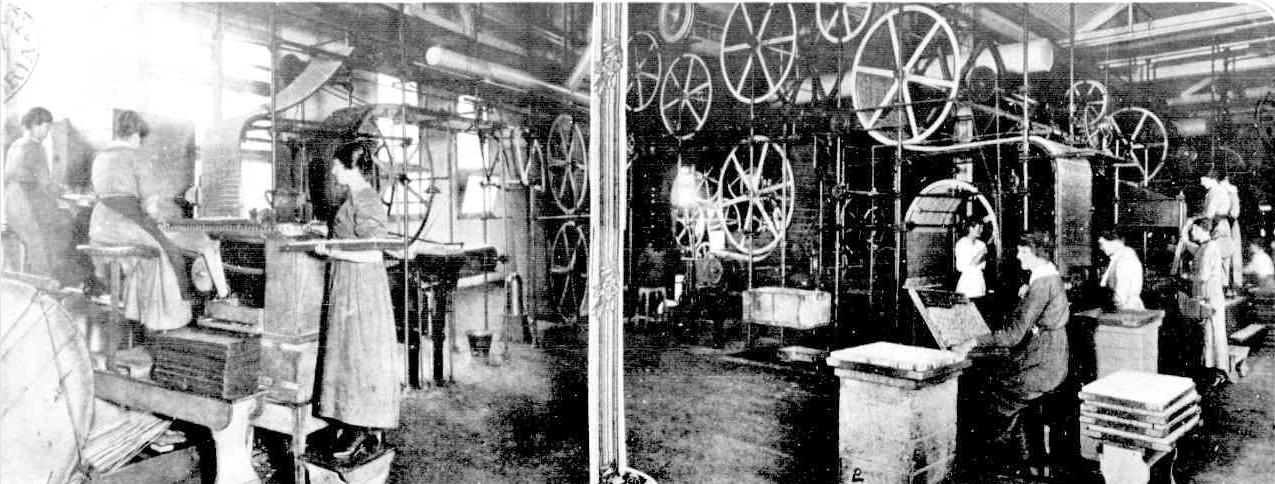

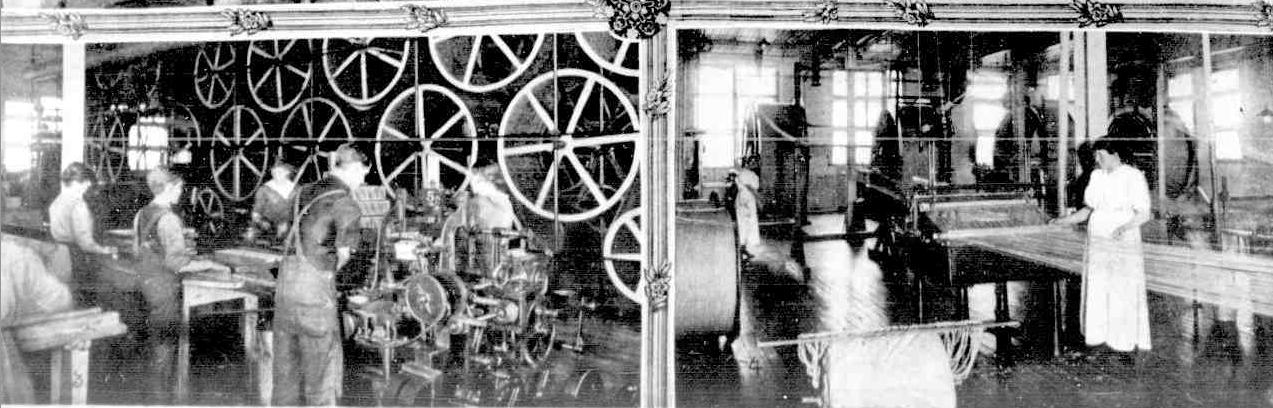

"We are not going to build a separate factory of our own," said Mr. Bartholomew yesterday. "We have come to an arrangement With Messrs. R. Bell and Co., at Richmond, Melbourne, to join with them In making a great extension of their present factory. It will amount to rebuilding the factory, and will Immensely increase' it. About 170 hands are employed there now. We expect to begin with about 300 girls and from 50 to 60 men. In the end, when things can be made in Australia which cannot be made here at present, we shall employ very many more.

"Only wax matches have been made In Australia as yet; wooden matches-safety matches-have so far been imported. We used to export from England a great amount of wooden matches to Australia. But first tho cheap Swedish and Belgian matches, and afterwards the Japanese, filled the market. The preferential tariff-1s a gross on plaid boxes and small safeties when made abroad, and 6d when made in England-helped us a bit. But we decided that we should rather pay that 6d in wages than In Customs duties, and decided to manufacture our own wooden matches In Australia.

"So the new factory will introduce tho new industry of wooden match-making; and we have also determined to manufacture all our wax matches out of non-poisonous phosphorus, instead of the poisonous white phosphorus. With our full support, the Premier of Victoria intends to bring in a bill prohibiting the use of matches made from poisonous phosphorus; and the Federal Government Is going to prohibit their Importation from June 1. The firm of Brynat and May voluntarily gave up the use of poisonous phosphorus in England nearly ten years ago. It did so before the result of the inquiry which was going on In England was made known. And it Is the only firm that ever voluntarily gave It up. It becomes illegal in England next January, The phosphorus out of which we make our matches hurts neither those who make nor those who use them. People will not be able to commit suicide with them, though drinking the heads would hardly be healthy as a practice.

"We expect some day to be able to make even our tin boxes in Australia. We shall use a good deal of stéarine, which is produced here, and I suppose glue and gum. Anything we can get here we shall get here-even the skilled labour If we can. We already have a factory in South Africa. We intend to make our factory most comfortable for our hands. We have always been on good terms with them in England, where we employ 2500 In our own factories, and goodness knows how many In the factories we have an Interest In."WOODEN MATCHES. (

1909, February 24).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 9. Retrieved from

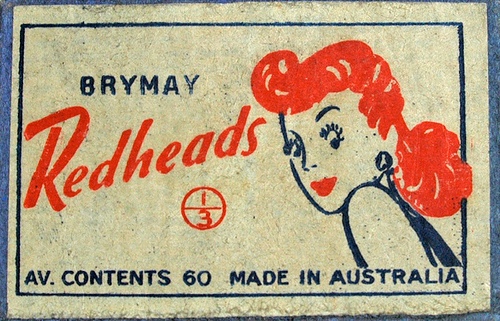

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15038416 Here in Australia they became and remain well known for their 'Redhead' brand matches - a good way to indicate a turn around - but now made in Sweden once again.

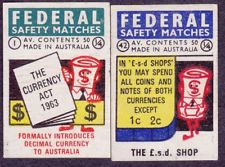

We've put together a little about matches and two local makers - Bryant & May,and Federal, to get you inspired to find out more. These two local makers had series of matches they ran to meet the times - even commissioning artworks for their covers in the case of Bryant and May or changing the 'hairstyle' of the lovely redhead on their Brymay Redhead matches.

We've put together a little about matches and two local makers - Bryant & May,and Federal, to get you inspired to find out more. These two local makers had series of matches they ran to meet the times - even commissioning artworks for their covers in the case of Bryant and May or changing the 'hairstyle' of the lovely redhead on their Brymay Redhead matches.  Those that are rare and in great condition will always fetch more than those that are not. Although many older matchboxes and covers will sell for a few dollars, those that haven't been seen for a few generations have fetched a thousand dollars!

Those that are rare and in great condition will always fetch more than those that are not. Although many older matchboxes and covers will sell for a few dollars, those that haven't been seen for a few generations have fetched a thousand dollars! To flatten a matchbook, use the knife edge to gently pry open and remove the staple from the book. The matches may be glued inside the book, so slide the knife down the front and back of the card of matches to loosen them and pry out of the book. It is ready to open up and press.

To flatten a matchbook, use the knife edge to gently pry open and remove the staple from the book. The matches may be glued inside the book, so slide the knife down the front and back of the card of matches to loosen them and pry out of the book. It is ready to open up and press.