March 14 - 20, 2021: Issue 487

Bobbie Squire

DOREEN MAVIS "BOBBY" SQUIRE

I was part of Victorian Line of Communications, which was headquartered in the building next door to where they housed all the Rolls Royce’s at Tishler’s Garage. I was christened two other names (Doreen Mavis) which are on my War Records but I’ve been married twice and at one stage I had seven names; so as soon as I could get rid of them I did; so I scrubbed the lot, paid $176.00 to have it done, and I’m just Bobbie Squire.

Vale Doreen Mavis 'Bobby' Squire

I was among the first ten to join up. We didn’t have officers, no such thing as an officer; they didn’t know what to do with us so they put us in a driver/mechanics job. We had to know how to take a car to pieces, the engine, and put it back together again. We did our training in West Circus which was there then, and not now, and I came second in my class; my bridesmaid came first and I came second. I had to have had my licence for two years before I could become a driver....

My officer, Colonel…. he thought I was his best, so if a General came down to Melbourne I got to drive them. You’re supposed to have stripes up and to fly a flag to drive a General. I drove them, no stripes, but I flew the flag.

...the chap from the British, that I drove was General Dewing. The other General I remember driving was General Vasey; he’s the one who went down in the plane off the coast of Queensland. I drove them to the plane; I used to drive them quite a lot.

I drove Lady Blamey, General Blamey wouldn’t have me, he wanted a man, and he had to have his Rolls Royce or Bentley or whatever it was. I didn’t drive him but I drove Lady Blamey and all the other Generals.

And I drove the very secluded men ... They had the little boat they called the 'Krait'. I didn’t know who they were, I didn’t know where they came from or where they were going.

Bobby's path, in her own words, runs this Issue as the History page because of her extraordinary experiences during this conflict and the insights she shared, and so that we may all remember her, Honour and Celebrate her, and her lovely spirit.

Apparently Bobby was thrilled with her page, shrugging off the gift she had given to us all in sharing these few insights in her own inimitable way. Still, this week we will hold her in our thoughts and say, again, Thank You For Your Service.

Where were you born?

Melbourne. In a place called Parkdale on the 2nd of April 1922. I am now coming up to my 91st birthday.

Where did you grow up and go to school?

Melbourne. I’m a Melbournian. I went to Mordialloc; I had a nursemaid and then I went to Mordialloc. My brother was dux of the school, he was a Maths genius. If I gave you 20 numbers, pounds, shillings and pence, he’d add them up just like that. If he’d been alive, the war killed him, he would have done so much with computers and things like that. We’d have never caught up. He was one of those geniuses. I had an aunt who was the same with the piano. She learnt it from 7 until 10 years of age and she could play all the Masters note perfect without the music. I had a genius with music, a genius with Math. Now my mother, the encyclopaedia; she could spell every word in it and tell you the meaning of every word in it.

What were you attracted to when growing up?

I tried everything. I couldn’t keep up with anyone. I tried the piano, and music; I loved listening. I knew I wasn’t up to mummy with the other thing. I knew I couldn’t do maths, so I went in for sports. I’ve been a ‘champion of champions’ a number of times. When my brother was dux of school they took me from school and I went to my paternal grandmother’s who started me in South Street Elocution, which was and is the leading place in elocution in the world, not just Australia, and she started that. So I went there. Straight from Infant’s School, into speech and all the rest of it. Mummy would dress me so I could get on with the boys, have fun and play all the sports, and we had some contests, I could jump better, I could ride my bike better, my horse better. But she was a Victorian lady, brought up by a lady to the manor born, she was known as Lady Jane, a real lady and she brought her daughter up as a lady so she brought me up the same way. I was swimming with Goff Vockler when the war started, Dee Why have a garden that’s dedicated to Mr Vockler by all the swimming people. If you could get his papers you would see that my training time in speed swimming was better then Dawn Fraser’s. She came after the war, I came on the war and lost the lot. It made a difference to my life though.

HOW'S YOUR LEG ACTION? Next week In "The Junior Argus" begins a series of Interviews with Goff Vockler by Mervyn Weston. Goff is a former Australian and Victorian champion, and is now official coach to the Victorian Amateur Swimming Association. He will tell you all you want to know about swimming and he begins by describing leg action. HOW'S YOUR LEG ACTION?. (1940, February 22). The Argus(Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1956), p. 15. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11281759

Well-known sports men at Unarmed Combat Training School, Contributor: Argus (Melbourne, Vic.) , ca. 1942: Shows Bobby Brown (Boxer), Harold Rixon (Footballer), Leo Monaghan (Footballer), Claude Hooper (Rugby player), Goff Vockler (Swimmer) and Lionel Brodie (Tennis player). Courtesy State Library of Victoria.

You must have seen a few changes in Melbourne since then?

So many; nothing stays the same. The first time to went to Korea I went to Texas street, I bought lovely shoes there, that was on a container ship. The next time I went I was on a cruise ship and there was no Texas street. The land that was there when I was there, must have been a mile, mile and a half, had been taken into the water. Been there but not the same. The same with Singapore; the first time I went to Singapore I went there before they took that mile off; I think I’d have killed them if I had a waterfront.

How old were you when you signed up?

I was among the first ten to join up. We didn’t have officers, no such thing as an officer; they didn’t know what to do with us so they put us in a driver/mechanics job. We had to know how to take a car to pieces, the engine, and put it back together again. We did our training in West Circus which was there then, and not now, and I came second in my class; my bridesmaid came first and I came second. I had to have had my licence for two years before I could become a driver.

I was among the first ten to join up. We didn’t have officers, no such thing as an officer; they didn’t know what to do with us so they put us in a driver/mechanics job. We had to know how to take a car to pieces, the engine, and put it back together again. We did our training in West Circus which was there then, and not now, and I came second in my class; my bridesmaid came first and I came second. I had to have had my licence for two years before I could become a driver.

I was passed to go on ambulances but at that time mummy was home alone, my brother was overseas, my father was overseas, and I wasn’t with her and she was alone. So I asked them if I could stay home. They said, if you can find anybody who would like to take on the ambulance work we’ll give you Staff Cars. Well, I was lucky; there was a lass there who was a country girl and she wanted ambulances. So she took my place and I took the Staff Cars position.

My officer, Colonel…., he thought I was his best, so if a General came down to Melbourne I got to drive them. You’re supposed to have stripes up and to fly a flag to drive a General. I drove them, no stripes, but I flew the flag.

Left: MELBOURNE, VIC. 1942-09. DRIVER CHERRY WALKER AND DRIVER KIT PEEL OF THE AUSTRALIAN WOMEN'S ARMY SERVICE AT WORK ON A MILITARY STAFF CAR AT TISHLER'S GARAGE, ST. KILDA ROAD.

Who were some of the Generals you drove…Americans?

Oh no, but I was stationed with the Americans for two months, as a driver. I was stationed with the Brits. for two months. They had taken over different places like the big Motel in St Kilda road…the Americans took that over. They took over Westleigh School in St Kilda road, they took over the big Church of England school in St Kilda road, they just moved in and took over.

Now the chap from the British, that I drove was General Dewing. The other General I remember driving was General Vasey; he’s the one who went down in the plane off the coast of Queensland. I drove them to the plane; I used to drive them quite a lot. They were in the original Victoria Barracks, not the one in Sydney, the proper original ones which were in the side of the hospital, that was where Vasey was. I drove General Vasey. Would you believe, I had the ex-servicewomen going up in Forster and I ran up against a Vasey. She had married General Vasey’s grandson and about a month ago I got hold of certain particulars from AWA’s headquarters and sent them to Forster for her. There’s quite a write up on the Vasey family; and do you know the wife, after she lost her husband, she started Vasey House. She was responsible for that, for looking after all the war widows.

Major General George Alan Vasey CB, CBE, DSO and Bar (29 March 1895 – 5 March 1945) was an Australian soldier. He rose to the rank of Major General during the Second World War, before being killed in a plane crash near Cairns in 1945. A professional soldier, Vasey graduated from Royal Military College, Duntroon in 1915 and served on the Western Front with the First AIF, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and twice Mentioned in Despatches. For nearly twenty years, Vasey remained in the rank of major, serving on staff posts in Australia and with the Indian Army. Shortly after the outbreak of Second World War in September 1939,Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Blamey appointed Vasey to the staff of the 6th Division. In March 1941, Vasey took command of 19th Infantry Brigade which he led in the Battle of Greece and Battle of Crete. Returning to Australia in 1942, Vasey was promoted to major general and became Deputy Chief of the General Staff. In September 1942, he assumed command of the7th Division, fighting the Japanese in the Kokoda Track campaign and the Battle of Buna-Gona. In 1943, he embarked on his second campaign in New Guinea, leading the 7th Division in the Landing at Nadzab and the subsequent Finisterre Range campaign. By mid-1944, his health had deteriorated to the extent that he was evacuated to Australia, and for a time was not expected to live. By early 1945 he had recovered sufficiently to be appointed to command the 6th Division. While flying to assume this new command, the RAAF Lockheed Hudson aircraft he was travelling in crashed into the sea, killing all on board.

Major General George Alan Vasey CB, CBE, DSO and Bar (29 March 1895 – 5 March 1945) was an Australian soldier. He rose to the rank of Major General during the Second World War, before being killed in a plane crash near Cairns in 1945. A professional soldier, Vasey graduated from Royal Military College, Duntroon in 1915 and served on the Western Front with the First AIF, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and twice Mentioned in Despatches. For nearly twenty years, Vasey remained in the rank of major, serving on staff posts in Australia and with the Indian Army. Shortly after the outbreak of Second World War in September 1939,Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Blamey appointed Vasey to the staff of the 6th Division. In March 1941, Vasey took command of 19th Infantry Brigade which he led in the Battle of Greece and Battle of Crete. Returning to Australia in 1942, Vasey was promoted to major general and became Deputy Chief of the General Staff. In September 1942, he assumed command of the7th Division, fighting the Japanese in the Kokoda Track campaign and the Battle of Buna-Gona. In 1943, he embarked on his second campaign in New Guinea, leading the 7th Division in the Landing at Nadzab and the subsequent Finisterre Range campaign. By mid-1944, his health had deteriorated to the extent that he was evacuated to Australia, and for a time was not expected to live. By early 1945 he had recovered sufficiently to be appointed to command the 6th Division. While flying to assume this new command, the RAAF Lockheed Hudson aircraft he was travelling in crashed into the sea, killing all on board.

Vasey's concern for his men outlived him. He married Jessie Mary Halbert at St Matthew's Church of England, Glenroy, Victoria on 17 May 1921. They bought a house in Kew, Victoria with a War Service Loan. Jessie would go on to found the War Widow's Guild, serving as its president until her death in 1966. Thus, "the legacy of George Vasey's war was a more compassionate Australian society."

What was it like driving Generals?

Absolutely nothing to it at all. They sat in the back seat. I drove Lady Blamey, General Blamey wouldn’t have me, he wanted a man, and he had to have his Rolls Royce or Bentley or whatever it was. I didn’t drive him but I drove Lady Blamey and all the other Generals.

I was the only one allowed to drive with an open worksheet; there was nothing on it. I was told where to go; I knew where to go, I was a Melbournian. At the Barracks there was a button over there so I pressed the button and got in the car and waited; sometimes two, usually three men came out, dressed any which way, it didn’t matter. Wherever they told me to go, whatever they told me to do I did then they’d sign me off, wherever I was, and I’d come home.

And I drove the very secluded men who had the duty of Coast Watching. Do you know anything about the Coast Watchers that were referenced in the musical the South Pacific? I didn’t know who they were, I didn’t know where they came from or where they were going. They had the little boat they called the 'Krait'.

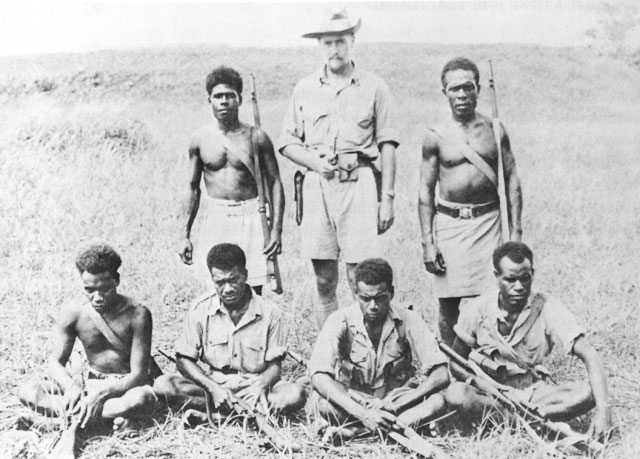

Left: one 'coast watcher', Martin Clemens and his Solomon scouts

Left: one 'coast watcher', Martin Clemens and his Solomon scouts

Major Warren Frederick Martin Clemens CBE, MC, AM (17 April 1915 – 31 May 2009) was a British colonial administrator and soldier. After a short leave in Australia in late 1941, Martin Clemens returned to the Solomons on a ship sent to evacuate European and Chinese residents from Guadalcanal. In late 1941 and early 1942, while serving as a District Officer in the Solomon Islands, he helped prepare the area for eventual resistance to Japanese occupation. His additional duties as coastwatcher alerted the Allies to Japanese plans to build an airstrip on Guadalcanal. Martin Clemens married Australian Anne Turnbull in 1948. They had four children. Clemens became an Australian citizen in 1961 and was involved in numerous public service and charity efforts.

The coast watcher - Only when the war was over I thought, ‘that such and such married the daughter of one of our Colonels who lived in Toorak. Anyway, that’s how I knew they were the people I’d been driving, and I was the only one who ever did it.

Did it give you a bit of a shiver realising that?

Yes, it did. I was at Pittwater (RSL) and they had a chap come to speak to us about that one day at a Sub-Branch Meeting. And I was able to tell them yes, I drove those gentlemen while they were here. And another time I was up at Kempsey and I went to the Maritime Museum there, and I told them who I was and what I’d done and they allowed me to put my foot on the Krait, it was in Kempsey then, and then it came here, to Darling Harbour.

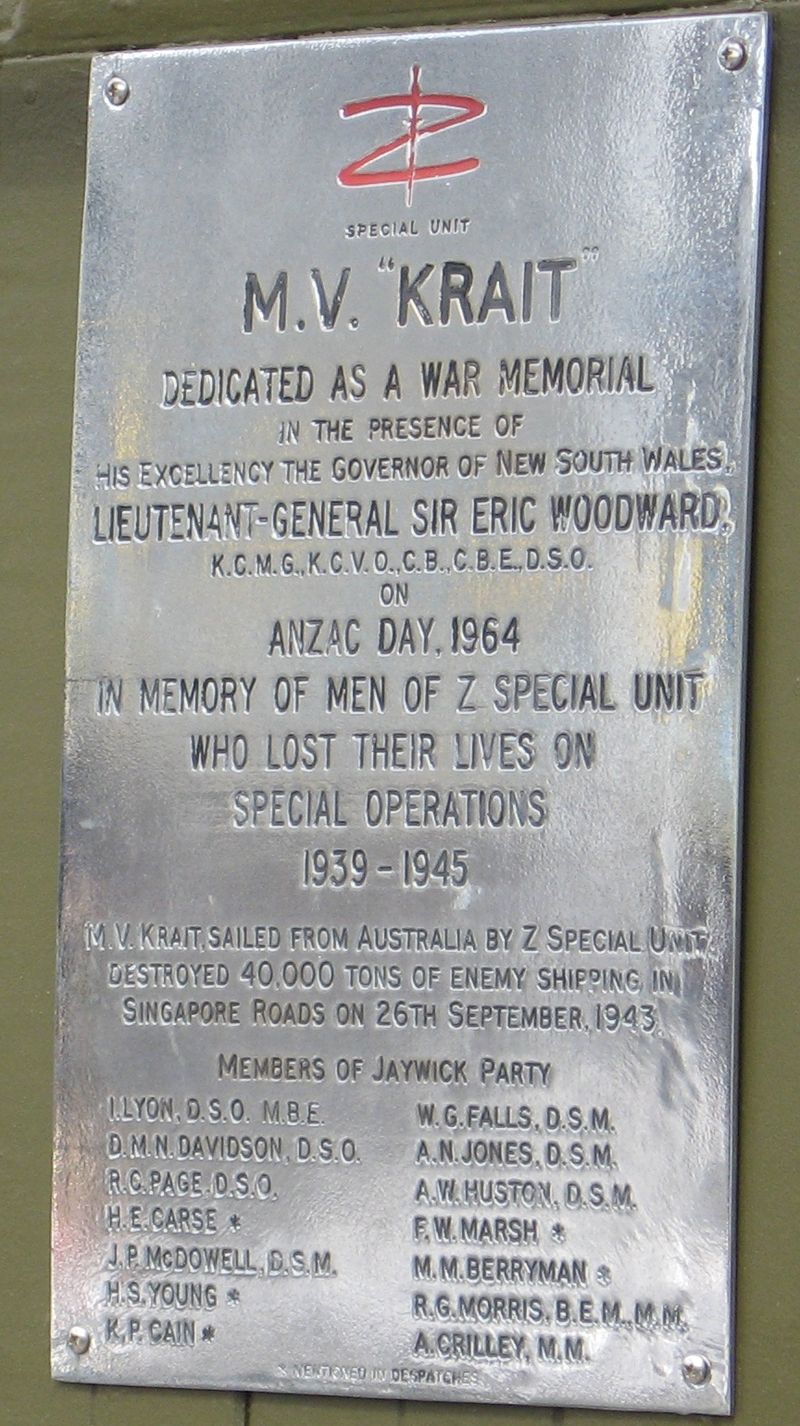

The MV Krait is a wooden-hulled vessel famous for its use during World War II by the Z Special Unit (Z Force) of Australia during the raid against Japanese ships anchored in Singapore Harbour. The raid was known as Operation Jaywick. The Krait was originally a Japanese fishing vessel based in Singapore named Kofuku Maru. Following the outbreak of war, the ship was taken over by Allied forces and used to evacuate over 1,100 people from ships sunk along the east coast of Sumatra. The ship eventually reached Australia via Ceylon and India in 1942, and was handed over to the Australian military. In Australian service, she was renamed Krait after the small but deadly snake.

Predominantly Australian, Z Special Unit was a specialist reconnaissance and sabotage unit that included British, Dutch, New Zealand, Timorese and Indonesian members, predominantly operating on Borneo and the islands of the former Dutch East Indies.

The Inter-Allied Services Department (IASD), was an Allied military intelligence unit, established in March 1942. The unit was created at the suggestion of the commander of Allied land forces in the South West Pacific area, General Thomas Blamey, and was modelled on the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) in London. It was renamed Special Operations Australia (SOA) and in 1943 became known as the Services Reconnaissance Department (SRD).

It contained several British SOE officers who had escaped from Singapore, and they formed the nucleus of the Inter-Allied Services Department (ISD) which was based in Melbourne. In June 1942, an ISD raiding/commando unit was organised—designated Z Special Unit.

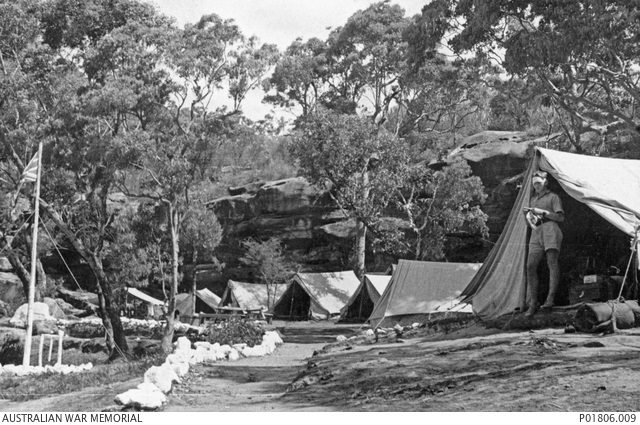

Several training schools were established in various locations across Australia, the most notable being Camp Z in Refuge Bay, an offshoot of Broken Bay.

Jaywick’s Camp X, Refuge Bay

Refuge Bay, Hawkesbury River, NSW. c.1943-01-17. Two members of SOE-Australia, code named Inter Allied Services Department, prepare to enter the water with a two man canoe known as "HMAS Lyon". It was a home made, experimental canoe made by Lt Donald Montague Noel Davidson, RNVR, and B3666 A B Frederick (Fred) Walter Lota Marsh, RAN, to fill in time at the Refuge Bay camp while waiting for MV Krait to arrive. It was hard to manoeuvre and christened it HMAS LYON as a joke. The Governor General, on a visit to the camp, 'launched' it for them - again, as a joke. They were preparing for Operation `Jaywick' in which operatives carried out a successful raid in MV Krait

Leading Seaman Frederick W. L. 'Boof' Marsh and Ordinary Seaman L. K. `Tiny') Hage, members of Z Special unit, Australian Services Reconnaissance Department, paddling a home-made experimental two man canoe "HMAS LYON" a hard-to-steer craft christened with this name as a joke and "launched" by the Governor General, also as a joke during a visit to Refuge Bay on the Hawkesbury. The canoe was made by Lt Donald Montague Noel Davidson, RNVR, and B3666 AB Frederick (Fred) Walter Lota Marsh, RAN, to fill in time at the Refuge Bay camp while waiting for MV Krait to arrive. The men were at Refuge Bay on the Hawkesbury River before leaving aboard MV Krait on Operation Jaywick. Date of photo: January 17, 1943

The Krait, the vessel which carried the men of Z Special Unit on Operation Jaywick

In mid-1943, Krait travelled from a training camp at Broken Bay, New South Wales to Thursday Island. Aboard was a complement from Z Special Unit of three British and eleven Australian personnel, comprising:

Major Ivan Lyon (Mission Commander)

Lieutenant Hubert Edward Carse (Krait's captain)

Lieutenant Donald Montague Noel Davidson

Lieutenant Robert Charles Page

Corporal Andrew Anthony Crilly

Corporal R.G. Morris

Leading Seaman Kevin Patrick Cain

Leading Stoker James Patrick McDowell

Leading Telegraphist Horace Stewart Young

Able Seaman Walter Gordon Falls

Able Seaman Mostyn Berryman

Able Seaman Frederick Walter Lota Marsh

Able Seaman Arthur Walter Jones

Able Seaman Andrew William George Huston

On 13 August 13th, 1943, Krait left Thursday Island for Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia, where it was refuelled and repairs were undertaken. Not only did the repairs cause delays in departure, but the folboats, manufactured by Harris Lebus and designated as model MKI**, which had been specially ordered for the attack by Lyon from England only arrived at the last minute. They were found to be faulty, lacked some important parts and were not according to the design that Davidson had specified. They had to undergo many on-the-spot changes simply to make each framework fit together and then fit correctly into the outer skins. This left the crew little time to get accustomed to them before being loaded on to Krait.

On September 2nd1943, Krait left Exmouth Gulf and departed for Singapore. The team's safety depended on maintaining the disguise of a local fishing boat. The men stained their skin brown with dye to appear more Asiatic and were meticulous in what sort of rubbish they threw overboard, lest a trail of European garbage arouse suspicion. After a relatively uneventful voyage, Krait arrived off Singapore on September 24th. That night, six men left the boat and paddled 50 kilometres (31 miles) with folboats (collapsible canoes) to establish a forward base in a cave on a small island near the harbour. On the night of September 26th 1943, they paddled into the harbour and placed limpet mines on several Japanese ships before returning to their hiding spot. They returned to Australia, reaching home on October 19th.

She was purchased for use as an Australian Royal Volunteer Coastal Patrol vessel in 1964 and returned to our area, being used as a training vessel on Pittwater. On ANZAC Day 1964 the MV Krait was dedicated a War Memorial; this plaque was affixed to its wheelhouse:

She was then acquired by the Australian War Memorial in 1985 and was lent to the Australian National Maritime Museum, where she has been displayed to the public since 1988.

Where did you meet your husband?

Where did you meet your husband?

I was at home, standing on my head, in my shorts. Mummy was sitting out on the grass reading, I had nothing to do; I had the day off, and I had my head down and I happened to look up and I saw a beret and I saw brown skin and I saw brown eyes and I said ‘mummy.’ And she looked up and promptly put her head down. And the next thing I knew was he stopped a bit further down and said ‘Oh excuse me, are you Mrs Kirkpatrick?’ and mummy said ‘Yes, you must be Jim.’

That was it?

What had happened was my brother was one of the first people to sail out in the Queen Mary. His number was 937, and that’s just after the officers, 937, and he was posted to Cowra. Just below it is a little place called Goolagong and a little log cabin which back then had only just been built, and the log cabin had boarders every now and again and Mrs Squire always ran the boys and of course the boys always asked if there was a dance. So he got them and brought them down, brought them from Cowra and Mrs Squire had to of course make friends with the head man, and it transpired that she had a son and my brother had a sister and wouldn’t it be nice if they met. They exchanged addresses. Jim came down to Melbourne to Seymour to get his Officer’s training, for a lieutenant, and he came to this address he’d been given and that was it!

SQUIRE-KIRKPATRICK.-On May 31, at St. Augustine's C. of E., Mentone, Doreen (Bobbie), only daughter of Lieut. R. H. Kirkpatrick, 1st and 2nd A.I.F., and Mrs. Kirkpatrick, of 17 Moorabbin road. Mentone, to Lieut Jim, A.I.F., elder son of Mr. and Mrs. Stan. Squire, of Talyalya, Gooloogong, N.S.W. Family Notices. (1943, June 12). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1956), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11348350

Love at first sight?

Absolutely. I’d never seen anything so gorgeous in my life.

Was he tall, dark and handsome?

Was he ever. I thought he was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen in my life. The only trouble was when he came back from the war he was not the same man I sent away. He wasn’t the same man, he couldn’t stop eyeing the girls once he came back from Papua New Guinea. I had the twins and he didn’t see them until they were a year old. We got married in May 1943, the children were born in 1944 and he didn’t see them, for the first time, until the end of that year. That was a marriage during the war.

We were young then, we hadn’t really started to live. By the time he came back I had moved up onto the family place. Which was 5000 acres then, the Squire family are big frogs in a little pond up there, even now, there’s a park at Cowra for the Squire family. They had the biggest shop; we kept the shop, I didn’t know about it then, but the shop kept Sydney supplied with hardware when the war came. That’s how big their store was. It was bought by Western Stores and Myers as time went on. I went and lived up there in a farm shed to be there when my husband came home from the war.

Your brother… he was sent to Cowra for training?

No; he was in transit from one place to another. You see we never knew or asked where they were going. We were never told where they were going. He was sent on the Queen Mary over to Tobruk but wasn’t in Tobruk when it was besieged. He had left Tobruk; he had gone from Lieutenant to a Captain and was freelancing; he got himself a Geraldine camera, that’s so big, (holds up hands) and he got himself into Tobruk while it was under siege, took photos of what the troops were doing there to try and keep safe, got himself out, taking his photos back to our lines and the Brits caught him. He was very tall, very straight, and handsome my brother, and they took him for a German. They were going to shoot him. And one officer, Boyd told me this, intervened and said, ‘Let’s ask a question just to be sure.’ And my brother didn’t drink, he didn’t smoke, didn’t go out at all; he was a brain, he didn’t exist like we do. So they said, ‘Alright, where is Chloe?’ Could you answer that?

Who is Chloe?

You’re not meant to say that, you’re meant to say where is Chloe?

Oh; Chloe to me is a girl’s name; is it a place also?

Chloe is a painting of a naked lady on the wall in Young and Jackson’s pub on the corner of Swanston and Flinders streets in Melbourne. You would have been shot.

Definitely.

He knew the answer because his father was a real rogue during the first World War, he knew it, and Dickie knew it because he’d been there and was always talking about the fun of life because Boy didn’t do that, he looked after the finances for the family, and but for the fact that Boy had listened to Dickie he knew who Chloe was and where Chloe was.

Can you remember the day peace was declared?

Yes. My husband left me with the twins and went up and spent the day with his mum and dad. From that day on I was not second fiddle I was third or fourth. It was just going downhill when he came home. On the farm, after the war, I learnt how to crutch sheep, I learned how to do the fly blow, I knew how to bring twins lambs into the world; I knew how to stand them up. What there was to learn on a property I learned in self defence. I was a city girl and they were all laughing at me because I didn’t understand. By the time I finished I knew more then they ever knew.

We went from Goolagong down to Victoria to live for a while because Peter was allergic to cows, pigs, sheep and horses (one of Bobbie’s twins) and he picked up dramatically, he wouldn’t have lived if we’d stayed on the farm. We went back to the sea and Peter picked up, he just grew, and I’d promised Mrs Squire that if ever Peter picked up we’d send them off to school if we could afford it and come back to live on the property. So we came back to live on the property but it still didn’t work so I said to Jim, give the bit of land back to your family, sell up what we’ve got here and we went to Forster and bought ourselves…a caravan park is what we set out to get…and we got talked into a brand new Motel. The Golden Sands Motor Inn, just as the bridge was built, so was this big brick Motel. This was ok until he got his eyes on the swinging hips, and I left.

I started travelling the world in 1960 and took him with me the first time I went, I’d saved up my money but I got my divorce in 1969. I went to Expo 1970 in Japan.

You didn’t have any aversion to going to Japan after your experiences of WWII?

No. My idea was everybody can be a savage given the right reason. When Jim came home and told his uncle what they were doing to our men, the men who got shot, that they were carving them up to eat as steak because they were starving, I thought, ‘They wouldn’t be doing that unless they had to.’ ..and there’s a chance our boys would have done the same. So I just thought ‘It’s over, let’s try and forget it.’

I went to the Expo ’70 on a Chinese boat. The Cathay was run by China Navigation, and the Tittorol, her sister ship, was the second one I went on.

Expo '70 was a World's Fair held in Suita, Osaka, Japan between March 15 and September 13, 1970. The theme of the Expo was "Progress and Harmony for Mankind." ?

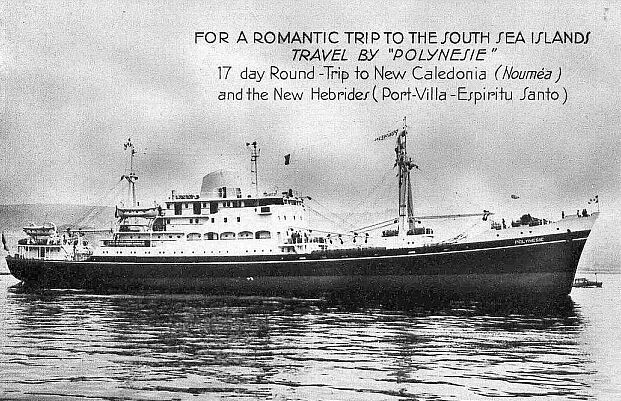

Yes. The first trip I was on we hit bad weather, that was the little Polynesie going out of Sydney to Noumea and the elements got us; we couldn’t take a load of tuna on because our chap doing the refrigeration was so badly sick. So we had to leave the tuna behind and came home empty. On one particular morning, my bunk was under my husband’s bunk and we had a window, which was square, and it had not stop rocking from the time we left Sydney and it usually didn’t worry me…but this time something was happening; things were moving and it thought I’ve got to get up and fix them, something’s wrong. I was lying on the super structure of the boat; the boat was at that angle (sideways) for me to be on the superstructure. The window was green. I knew we were under the water but then slowly, because we were like a cork; we didn’t have our load of tuna on board, slowly she came up. And everything down that side of the vessel; the deck equipment, the portholes, all gone..the davits, the whole lot, gone.

We had five French ambulances waiting for us when we got there. There were broken ribs…I was on the superstructure, as was Jim. But the ones on the other side of the ship, when she rolled, they fell on top of each other; broken ribs, legs and arms. When we arrived the French Officers were dressed in their whites coming along the coast and our seating in the dining room, big chairs like that, like armchairs and pink and white, and also on the deck; you had to put your feet up because the water was full of glass. When we’d see it was about to roll back again, we’d lift up our feet again. The captain came out with a pot on his head and soil dripping down.

We had five French ambulances waiting for us when we got there. There were broken ribs…I was on the superstructure, as was Jim. But the ones on the other side of the ship, when she rolled, they fell on top of each other; broken ribs, legs and arms. When we arrived the French Officers were dressed in their whites coming along the coast and our seating in the dining room, big chairs like that, like armchairs and pink and white, and also on the deck; you had to put your feet up because the water was full of glass. When we’d see it was about to roll back again, we’d lift up our feet again. The captain came out with a pot on his head and soil dripping down.

That wave hit three other big ships all the way around the world. It was a big wave. He’d seen it at six o’clock, just enough to pull the little Poly almost into it but not quite. That was my first trip by ship. But I had us booked in another one before we docked.

I said to Jim, ‘Well how did you enjoy that?’

He said, ‘Well, that was an experience!’. I said, ‘I hope you enjoyed it because you’ve got another ship coming next year.’. I thought he’d kill me but he went with me the next time and we ran into when they’d had a discussion, a debate in Hong Kong and Star Ferries got mixed up in it too, and going to catch our plane we had to have a police guard so we didn’t get caught up in it. They had all the windows boxed in; so the first time I went out we nearly went under, the second time we had a revolt with the Star Ferry and all the rest of them.

“people took to the streets in 1966 to protest about the increased fares of the Star Ferry (passenger ferry between Honk Kong island and Kowloon); violent confrontations with police ensued.” From, Chinese National Cinema, By Yingjin Zhang, 2004. Routledge. New York. A petition was created with 20,000 signatures in protest against any increases in transportation costs. The result led to the arrest of 1,800 people.

The next time I decided we’d go away it was the coldest Winter they’d had in New Zealand for decades. The entrance to Milford Sound was just about iced in. we were the first bus allowed in and when we got in we found the rest of the buses had been left in there so we tried to tow that bus up and out and the packed ice all around the entrance, I thought, some fool’s gong to go ‘cooee’ and bring the whole lot down. Anyway, they didn’t, and it came down about an hour after we’d left. So we got out of that one. Anytime I’ve been away there has been something outstanding or hair raising happened. Oh, I’ve had fun wherever I’ve been.

In 1971 I went on the Women’s Weekly cruise around the world.

What was that like?

Out of this world. I was the mother of 37 kids; they were from 18 to 29, 30 years of age. They were all musical, all having fun, and of course I carry on and have fun with anybody. One day I was asked to go up and see the Captain and he put me in charge of all the kids when they wanted to have fun. We put a concert on and they had first and second sitting near Malaya; and we put the show on on the first night and the second night. We took over the boat, the ship. It was wonderful. We had a ball, all dressed up; I was doing ‘Diamonds are a Girls Best friend’ but I got out of that one, gave it to the younger ones to do and was just sitting there telling them what to do. We had fun with that, and would you believe forty years later, last year or the year before, I got a letter and a phone call as I’ve kept in touch with a few of them, saying that we’re going to have a 47th get-together, how are you, are you going to come? So they came and picked me up and there I was, once again grandmother of the kids. Not mother, grandmother!

So after you left Forster where did you go?

I went down to Melbourne to look after my father and when Dickie and Co said we don’t want you anymore, I said, righto, I packed up within five minutes and was gone and came back and lived at Queenscliff and got a job as a Teller in the Commonwealth Bank. I’d never handled money before, I could barely look after my own, and I had to slicker along with the rest of them and what I found with money is you’ve got to balance at the end of the day. I looked at it as you have to have x amount of nails, or pins, and if you look at it as money then you’re lost. I worked there until I had my tumour removed from my face, and then I couldn’t go back. This was 1975. I had a palsy, it was paralysed, for nine months; I hung down here. (indicates chin) I worked on it for nine months. I still can’t taste or smell.

What sort of tumour was it?

A tumour caused by passive smoking.

Was this from all those in the cars you used to drive puffing away?

Yes, I loved the smell of cigars and the pipes were really delightful. I didn’t smoke while I was in the Army, I took my supply home to mummy but I did learn how to roll your own and I did that for some of the troops, the troop ships I saw off; I rolled them for them, they were too drunk to roll them for themselves.

Were they getting gumption from a bottle? Too many terrifying stories?

In World War II they didn’t carry on like they did with the first (WWI). You see when Dickie came home from the first it was wonderful, he told us everything; that’s why I could tell the story of My Fighting Family, which is in the archives in Canberra now, ‘My Fighting Family’; which I could do because my father was still alive and could tell me the facts, he was in the artillery, and the Furphy, that the water truck didn’t turn up, and I decided I’m going to call it a Gilliard, not a Furhpy; I got looked at the last time I said that…and Aceh and Adina and all those events; that’s what brought the First World War out so that what we knew didn’t die with us or them.

Of course when my brother came back, he had a wound from India, he joined the British Army when he came back. He had an honourable discharge from the Australian Army so he could join as a Major the British Army. His idea was that you did not lead them, you told them where you were going and how you were going to do it. That’s how he and his troops could stay alive. Not like the Brits do it; they led, and nobody knew where they were going and what they were going to do.

How long did it take you to rehabilitate yourself from the tumour? How did you get through that?

There’s something there I wish the medical staff would listen to and take to heart. I wish I could let them know that that is what is happening because that was what is happening. People just won’t stand still and listen, the attitude is ‘dear old souls, they’ve got marvellous imaginations.’

While I was going up and down during this operation the ear is taking all this in and transferring it to the brain. And as soon as I heard that same noise calling that officer who was then beside me I got the pain I was going through; I just passed out. A ten hour job (operation) from there right around to here (from under eye to jawline); they peeled the face back, the tumour was too large to cut, so they had to remove my whole ear and put it down on the pillow beside me and get the garrotted tumour out and then they had to put it all back. When he (the surgeon) got me back to bed he had a meal coming for me and I couldn’t open my mouth. He sat down on the side of the bed and two tears rolled down his face; he said ‘I tried so hard not to hit nerves. I did try.’

I feel now, if you go in for a big Op’., anywhere where it’s near an ear, either block the ear or do something. The pain that came out when I heard that bell, triggering it off. How could I make that up? I came back out of that and wasn’t allowed outside because I couldn’t close my eye; it was always open; I had to tape it shut when I went to bed so I didn’t cut it on a pillow or something. They kept me in hospital for three weeks with this thing that vibrated on top and then went deep, this was to try and get the nerves working.

When I had the tumour itself I had to have the cobalt and they would sit me in a little room, three times a week. I had to catch the first ferry from Queenscliff over and I would try to sit on that side so no one could see my face. So for months I had to go through town three times a week to get the cobalt done sitting in this little room. I’m claustrophobic by the way; oh I did hate sitting in that room by myself, I really did. It was a case of ‘don’t panic, they’ll come back.’

At the end of nine months I had got rid of it all except a little movement here (points to side of nose). I would stand in front of a mirror and I’d say ‘move that brow, move that brow,’ now, ‘move that nostril’ and then ‘move that lip.’. I got to the stage where I thought I’d scream, and nine months it took me; no going out or going anywhere or doing anything other then that. As soon as they did the cobalt that, and that’s the only place, did not improve. It couldn’t improve after the cobalt (indicates side of nose again). So it killed my taste, it killed my smell, it killed my saliva; it killed everything.

If you could say something to our younger generation about what it is like to go through a war to them, an insight into what it is like to experience war and to get out the other side, what would you say? Is there some message you would communicate?

Yes. If they weren’t satisfied with the lives they were leading, try and change their own outlook on life before they help the world to make a mess of the way things are going; that’s all I can say is; you’re only one person, and you only think as one person, you can listen to the fun side of war, you can read about and see the destruction, but you can’t ever realise the pain and hurt the people who are in it or are left behind are going through. So, try and think before you even consider this; think; is there a peaceful way we can change this world without another war? Is there some way we can help?

What is your favourite place in Pittwater and why?

On the beaches in the sun; any beach and in the sun.

What is your motto for life or a favourite phrase you try to live by?

Rather then being irreligious; I’ve tried living by the Ten Commandments but I know it’s a sheer impossibility because I will tell a white lie so I won’t hurt anyone’s feelings; but it is still a lie and that’s the first commandment; That Shalt Not Lie! So, I can’t live by my Ten Commandments, so the next thing is ''Don’t ever say anything to hurt anybody. Never hurt anybody or do anything to anybody that you wouldn’t have them do to you.''

It’s the truest thing anybody could ever say.

Bobbie Squire in 2013. Photo - interview by A J Guesdon.