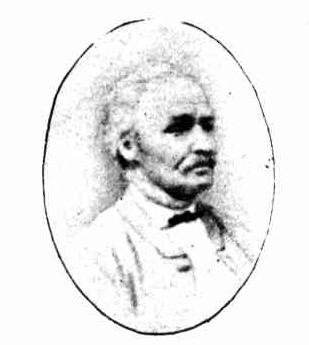

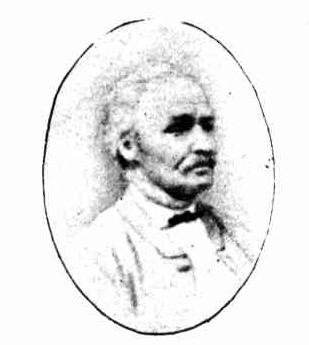

Emile Theodore ARGLES Timeline

Born in 1851 to Charles Douglas Argles and Anna Mlle* - sic(nee Samson)

His Birth was registered at St. George Hanover Square, London - St. George Hanover Square District. There is also a birth registration for Emila Theodore Argles, County: Middlesex, in 1851

His father was born in 1824 to Charles Argles and Elizabeth Thomasine Gibbs. The Alfred Argles that appears in some references was a younger brother of his father who came to Australia, had a son who was named 'Alfred' (born 1850 in South Australia), who also had a son called Alfred Henry. The Alfred Argles that funds the publishing of 'Society' is the first Australian born Alfred Argles, and Emile's cousin. Alfred lived at Neutral Bay - more on him anon...

Emile Theodores parents married on the 7th of April 1845, at St Margaret’s, Westminster, London. His father, a clerk by 17, and then solicitor, died in 1899, his mother in 1913:

August 10, 1913, Thames, Anna Argles, widow of Charles Argles, solicitor, London, 86th year. In Saturday 23 August 1913, Weekly Freeman's Journal, Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Page 9

The Argles had at least five sons and four daughters - Napoleon Fredrick Argles, Arthur Felix Argles, Theodore Emil Argles, Julia Alex Argles

Frank William Argles, Josephine Argles, Celeste Argles, Augustus Charles Argles, Charles Argles. His father was a solicitor whose chambers were in Jerusalem Court, off Gracechurch St, London - John Edgar Byrne (QLD), who later published some of Emile's early works here, had brothers working as stockbrokers - hinting a link between these may have sent Emile north months after landing in Australia.

*Abbreviation: Mlle. (often initial capital letter) a French title of respect equivalent to “Miss”, used in speaking to or of a girl or unmarried woman: Mademoiselle Lafitte.

Gracechurch Street in Norwood’s 1799 map

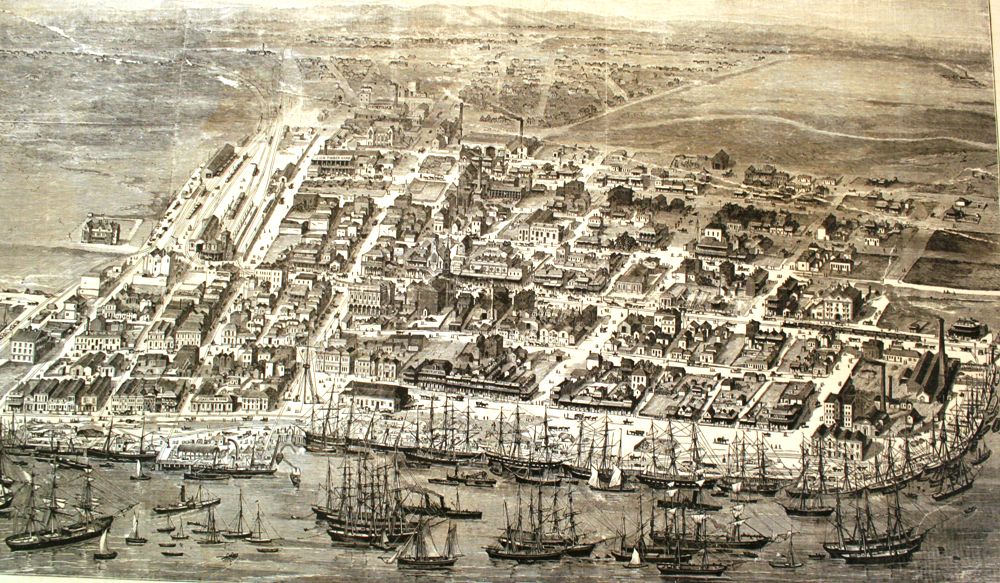

In December 1872, aboard the Hampshire, from London, Theordore Emile Argles lands in Australia.

Family Name Given Name Age Month Year Ship

ARGLES THEODORE 21 DEC 1872 HAMPSHIRE B 315 001

London papers and those in surrounds were advertising options the year:

EMIGRATION TO QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA. ' Queensland Government Offices, 32, Charing-cross, London By Authority of ..

... EMIGRATION TO QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA. ' Queensland Government Offices, 32, Charing-cross, London By Authority of the Agent-General for Queensland. Land Order Warrants for 40 acres per adult issued to persons paying their own passage. Homestead selections ...

Saturday 25 May 1872, Hampshire Advertiser, Hampshire, England

Miscellaneous Intelligence

... by nearly £700,000. Above seven millions of gold arrived in this country from the United States; the import of gold from Australia declined from five millions in the first three quarters of 1871 to four millions and a half in the corresponding period of ...

Saturday 19 October 1872, Tamworth Herald, Staffordshire, England

SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE.

"(BY ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH)

Queenscliff, December 21. -

He alighted at Adelaide unless is among the second and thirds class passengers (100) aboard still and heading for Melbourne: ENGLISH SHIPPING. (1872, November 22).The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199376681

Although in his first few years here Emile Theodore caught ships in short leaps between towns and 'cities', most of his travel appears to have been via trains between states - a hearkening back to his English upbringing.

On Monday a tea meeting was held at the Town Hall Exchange Boom, in connection with the Young-street Mutual Improvement Society. The tea; which passed off successfully, was followed by an entertainment of. a miscellaneous character. . It, comprised .songs, glees, recitations, readings, and an instructive and enjoyable lecture in two parts,-entitled “Flatterers and Fault-finders," delivered by the Rev. O. Lake. The lecture was attentively listened to, and at its conclusion the appreciation of the audience was shown by loud, applause. The Rev. gentleman gave some most amusing illustrations of " Flattery "and Ridicule " In course of his remarks he referred to the excellence of Geoffrey Crabthorne, spoke of the harmlessness of Portonian, and expressed his gladness that Pasquin's "dirty rag" was no more. The rest of the entertainment was much enjoyed, almost every individual selection being excellent. At, one end of the room there was a table bearing various articles—useful and ' ornamental –in which a small trade was done during the evening. GENERAL NEWS. (1873, January 14). The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, SA : 1867 - 1922), p. 2 (SECOND EDITION.). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207743729

The first 'Pasquin' of South Australia:

THE LATE MR. E. R. MITFORD.

THE LATE MR. E. R. MITFORD.The late Mr. Eustace Revely Mitford was a near relative of the famous authoress of that name. He came to South Australia in the early days, and for many years conducted a witty satirical paper styled "Pasquin." He was remarkable for his keen wit, caustic humour, and the originality of his style; also for his caricatures, which were drawn in a daring fashion peculiarly his own, and are highly valued by those who are fortunate enough to possess them. He keenly satirised and caricatured the South Australian Government of his day with pen and pencil. He died on October 24, 1869, aged fifty-eight, and was buried in the cemetery of St. Mary's, Sturt, where his friends erected a monument to his memory. THE LATE MR. E. R. MITFORD. (

1899, January 7).

Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 - 1904), p. 3 (Illustrated Supplement to the Adelaide Observer.). Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article162353873

This book was bought for all libraries in SA by the local communities and reading societies:

PASQUIN. PASQUIN.

Reissue in one volume, with Portrait of the late Mr. E. R. Mitford, now ready, price £2 2s. The publication is for the benefit of Mrs. Mitford, the Editor's Widow. Old Colonists and others desiring copies are requested to apply to the undersigned.

LAWRANCE & BROOK,

These items, published in newspapers Emile would have had access to, underline that though the 'Bohemianism' that was to become a creed among Sydney writers may have owed much to Emile, his French mother and heritage (and his own 'pilgrimmage') he was surrounded from the outset of his time in his new home by people with a similar mindset:

ODD NOTES.—BY A BOHEMIAN.

I LIKE to hear Lilley pronounce an eulogium on the legal profession. He is easily drawn into doing it, and, once he starts, the listener gets a rare intellectual treat—my word! I have heard him several times, and would go a long way to hear him do it again. He warms up to that work, all his sympathies are enlisted, and the floodgates of hit eloquence are unlocked. The unsullied purity, lofty patriotism, high-toned morality, and universal philanthropy that hare in all ages distinguished lawyers from the rest of mankind, are set forth with such clearness and force that for days after hearing him I can scarcely refrain from taking off my hat to every lawyer's clerk I meet. I hare long had such a profound respect for the whole legal fraternity that I never approach any member of it without a feeling of awe. There is no doubt that they are all Mr. Lilley thinks them to be —and something more. They are above all things the defenders of the liberty of the subject. Give them an adequate fee and they will rack their brains, twist and torture statutes and precedents, browbeat and frighten witnesses, mystify Judges, and bamboozle juries into believing that their clients are at liberty to do any mortal thing they feel inclined to do. That under the peculiar circumstances- in which their clients are always placed they could not possibly hare, committed the offence with which they are charged; or if they did, that it was deserving of praise rather than punishment. We had a fine illustration the other day of the valuable services lawyers can render a man at a critical time. A tradesman of Melbourne felt dissatisfied with the way things were going on at home, so he made up his mind to clear out with as much cash as he could lay his bands on, leaving his business partner to make the best arrangement he could with his creditors. He landed in Brisbane with over two thousand pounds ready cash in his pocket, and was going to settle down quietly in some snug retreat to enjoy himself.

The Brisbane detectives were informed by telegram from Melbourne that a warrant was on its way here for his arrest, so they took the man into custody directly he attempted to leave the city. The lawyers heard of the two thousand odd pounds, and their hearts yearned for that man, and so ready were they to assist him that be had the greatest difficulty to decide who should undertake the task. There was no time to lose. The warrant was close at hand, hot had not actually arrived, so a Judge of the Supreme Court was appealed to, and the man was released. Not only released, but a scheme was devised and carried into effect, by means of which the detectives were baffled, and their prey spirited away into safe hiding. Now, the Government are offering a reward of £25 for his apprehension—but they will have to offer. He is worth more than £25, and will not be bought for such a paltry sum. I call it great triumph for the lawyers, and a splendid illustration of their value in a community. The ends of justice have been signally defeated, and the liberty of the subject secured in spite of detectives, warrants, and the whole machinery of the law "in that case made and provided"—and nobody but the lawyers and their clerks know exactly how it was managed. My erring brethren, whenever you make up tout minds to break the law, be sure and reserve sufficient cash to buy up the lawyers—and they make the rest all right.

We used to hear a great deal about Ipswich influence in the councils of this great colony, and I believe that influence was and still great; but it's nothing in comparison to the Kangaroo Point influence in appointments to the Civil Service. My present ambition is to get an appointment as National School teacher under my friend Randal Macdonnell, as I feel persuaded we could get on well together, but if he can't make room for me I shall have another try for the Civil Service. I won't depend on Palmer this time—it's no me. I shall take a house at Kangaroo Point, and secure that influence, and then I shall be right. An old friend of mine, by a lucky chance, got into a snug little billet the other day, but he did not feel at all safe until he had set up his lares and penates at “the Point," so he did it in a hurry, and now he breathes freely. It was touch and go with him until he had completed his flitting. I expect when my friends Dickson or Cameron have real estate at the Point to dispose of in future, they will make this a prominent feature among the advantages and attractions the property possesses to intending purchasers. If they can say, "this valuable site or eligible allotment overlooks two reaches of the river the whole of North Brisbane, and a magnificent panorama of hill and volley, with the wood crowned heights of Taylor's Range in the distance," and then wind up, you know, by saying that "it is in the very centre of Civil Service patronage, being bounded on the east, south, and west by the properties of Messrs. Lands and Works, Post-office, Audit, Customs, Ac, &c."

Depend upon it such a description would send the price of that land op to a very high figure indeed. Ambitions heads of families and aspiring young gentlemen would compete for it to the utmost extent of their borrowing powers, while that friend of auctioneers, "the speculator on the look-rut for an eligible investment," would not let it pass him for a trifle. I do not anticipate great results from the Intercolonial Conference. When six Australian Premiers lay their heads together it will be a strange thing if they cannot decide upon something for the general good. But my fear is that our own Premier will allow himself to be talked over by the others, and that be will not secure the recognition of his own dignity and importance as the principal representative of this wonderful colony. He is such an excessively modest and retiring young man and so amiable and yielding, that anybody can get over him. The feet of his being a Good Templar is, you see, all against him at a. meeting of this sort. He frequently imbibes ginger beer until he brings himself down to such a flabby mental condition that he would let a child persuade him, and, when in this state, his elaborate courtesy and refined language are apt to lead strangers to form a wrong impression of the man, and take advantage of his weakness. I hope Thompson will see. that his chief does not go into the ginger beer so extensively down in Sydney as he is in the habit of doing here. We are used to it, end don't notice the thing, except to laugh over and feel rather proud of it. That affair on board the Basilisk the other day, for instance, is still talked over with delight at all the public-house bars in Brisbane, and the popularity of the Premier is becoming as great in the metropolis as Sandy Fyfe's is at Rockhampton. We all feel honored in having such a man at the head of our Government, for the little failing before alluded to only endears him to us the more. But at a conference of hotheaded, overbearing, and hard mouthed Premier! from other colonies he will be snubbed and sat upon to any extent, unless Thompson can proceed in spurring him up a little—which is doubtful. ODD NOTES.—BY A BOHEMIAN. (

1873, January 18).

The Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld. : 1866 - 1939), p. 4. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27274389

Death, of " Bohemian.'

A wire was received in town at noon the 8th instant conveying information of the death, at half-past 11 that day, at Saudgate, of Mr. George Hall, who, for many years, occupied the editorial chair of this journal. The deceased gentleman was upwards of 60 years of age. He came out to Queensland in 1864 to join the staff of the Guardian. When that journal stopped issuing he became connected with the literary staff of the Courier, and in 1874 he was appointed editor of the Telegraph, from which position he temporarily retired in 1878. Early in 1880 he again assumed the editorship, eventually retiring from that position in June, 1885. Under the nom deplume, “Bohemian," he was known throughout Australia, and "Odd Notes" from his pen appeared for several years in the Queenslander and then in the Week, their first appearance in the last named paper being in January, 1876. Those who knew him will remember him as one of the truest souls in friendship. Though not brought up to journalism, Mr. Hall had the true spirit of a journalist. He was scrupulously regardful of facts and truth; painstaking and plodding to a degree. He had singular powers of observation, a ready faculty of generalising facts, an easy style of writing, a humour dry and apt in its use, which gave an admirable tone to his articles. A little more than three years ago he, on account of failing health, retired from the editorship of this journal and took a trip to England. The cold weather there nearly lolled him; he was glad to hasten back; but his health never rallied sufficiently to enable him to do constant work. After his return from England he joined the leader staff of the Telegraph, and held that position till his death. The Bread of Queensland is the poorer for the death of George Hall, and no man ever had a kinder-hearted or truer friend. The funeral took place on the 9th instant, the cortege leaving the Permanent Building and Banking Society's Office, Adelaide street, shortly after 2 o'clock for the South Brisbane Cemetery. Amongst those present were the Hons. J. B. Dickson and .J. Swan, Messrs. H. Wakefield, B. B. Bale, .Alderman Byram, who represented the building society of which Mr. Hall was one of the founders; the editor of the Telegraph, and Mr. C. Mills, and other accredited representatives of that paper's several departmonts; the city editor of the Courier; the editor of the Observer; Archdeacon Matthews, Mr. T. W. Hill, Mr. 8. W. Brooks, and others; and Mr. Loader representing the Moreton Mail and the South Brisbane Times. The burial service was conducted by the Rev. J. Welsh, Baptist minister of Sandgate and pastor of the church of which the deceased was a member. The last resting place of our departed colleague is beside that of his parents. Several wreaths were placed on the coffin, one of them being from the Telegraph standing as a last tribute to him who was for so long their chief and comrade. Death, of "Bohemian." (

1888, November 17).

The Week(Brisbane, Qld. : 1876 - 1934), p. 13. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article183937950

THE SUM OF LIFE.

By a Kangaroo Point Admirer of Longfellow.

Tell me not in scornful numbers

That the Point can’t boost 'the cream' ; .

For the Civil Service numbers ? !

All its sweep from stream to stream.

Civil Service life is earnest ;

In the race to gain the goal

Screw-love in each bosom burnest ;

Pay delights the Pointer's soul.

Much to get, without much bother,

Is our destined end and way ;

All outside our 'ring' to smother,

Who aspire to place and pay.

Palmer's strong ; no need for bleating,

'Cause our billets we can't save,

And the state milch cow is meeting

All the bills we cannot waive.

In the struggle after office,

In the rush for place and pay,

We but think how great the muff is

Who to berths can't find his way.

Trust no promise, however pleasant,

Till you see your name in print ;

The Gazette's no welcome present, :

If our circle is not in't.

Civil Servants all remind us,

That an easy life's sublime ;

That when we go, we'll leave behind us, -

Footprints on the path we climb.

Footprints that some unborn brother;

Seeking place, and hoping gain,

May travel safely, and not bother '

Friends or ministers in vain.

Let us then, one course pursuing,

Strive to make the Point the gate

To preferment — aye eschewing !

How to labor, how to wait. —

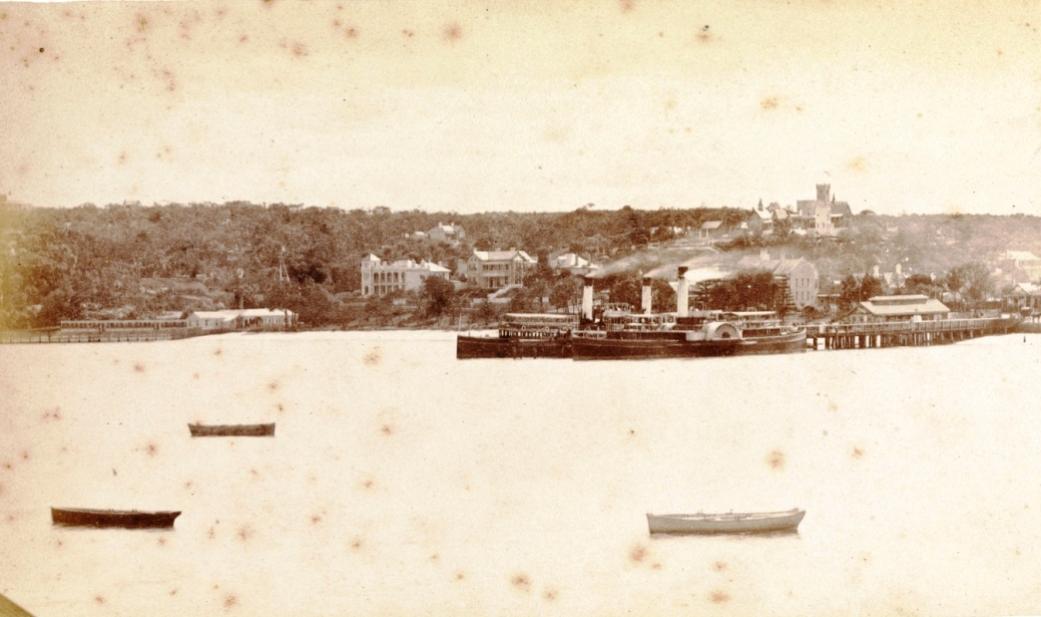

Brisbane River below Kangaroo Point Cliffs, ca. 1885 [John Oxley Library, State Library of QLD.

His forerunner, in Eustace Revely Mitford, had a similar subject matter:

Abuse or Patronage.—In an old number of Pasquin we find the following remarks made about the then recent appointment of Mr. Bellhouse to the office of Accountant in the Railway Department:—"A vacancy lately occurred in the office of Accountant in the Railway Department by the resignation of Mr. Paqualin. The Assistant-Accountant (Mr. Overbury), an efficient officer, very properly succeeded Mr. Paqualin ; but Mr. Overbury's vacancy—How was that to be disposed of ? Why if was conferred on the next most deserving and of course competent officer in the department. Eh! Oh, no! gentle reader, nothing of the kind; it was in the gift of the Hon. the Commissioner of Public Works (Mr. English), and by that gentleman disposed of to one of the clerks in the office of Messrs. Brown & Thomson's timber yard. This is a most unjust way of disposing of the appointments of the province, and will only lead—as in all cases it does—to inefficiency, discontent, and 'disorganization' See what the Police Force has come to through this vicious system, and its effects may be traced throughout all the departments of the Civil Service." THE RABBIT NUISANCE. (1873, February 11). Kapunda Herald and Northern Intelligencer (SA : 1864 - 1878), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108271228

THE CIVIL SERVICE.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE BRISBANE COURIER

Sir-Some attention is being drawn at present to the Civil Service, and to the unequal favour shown towards the members of it by those in power.

Unless what the Toowoomba gentleman says is true, viz , that the Opposition is in the pay of the Ministry, I have a remedy to propose to which I respectfully call the attention of all honest men interested in such of the Civil Servants as are underpaid , and I call upon all such honest men to do their duty towards their neighbor.

Let, then, a member of the Opposition move for a return of the following -

A list of Civil Servants who have had their salaries raised since 1871, the same since 1870, the same since 1869, and so back to 1864, we will say , giving the amount as well as increase in each case

Also a return of tho Civil Servants who have not had their salaries increased since 1870,1869, and so back to 1861, or further giving the names, offices, and the amount of salary paid.

This return would make the hair of honest kindly men stand on end at the iniquity of the heads of departments, and fill all hearts with pity for those who toil on in summer heat and winter cold, with families to keep, and without a hope of promotion, and all because they don't "move" in Kangaroo Point "circles"

Even when Ministers do bring up nu old toiler for increase of salary, they take care to tack on to him a bunch of drones for increase at the same time And if the Assembly vote the lot, then their favorites reap the benefit, and if the Assembly (happening to detect the drones' names) refuse to grant the increases, poor toiler has to go without as well, and the Ministry shrug their shoulders, and say to him, "It is the Assembly's fault."

Let the Assembly then vote each man's increase separately, and see that drones and working bees are not brought up together in a bunch for a rise, and so let them spoil this stale, old, game of the Ministry.-Yours, Coker Brisbane, May 2. THE CIVIL SERVICE. (1873, May 5). The Brisbane Courier(Qld. : 1864 - 1933), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1315980

The " Maryborough Advertiser " has a heavy down" on " parsons," and chronicles in the following paragraph the visit of the Rev. Mr. Backhouse, who is raising funds for the British and Foreign Bible Society :—" An ecclesiastical tramp will go round with the hat this evening in the Independent Church. He is begging badge is 'Bibles.' This self-constituted and ignorant man is one of a gang of men who lead a lazy life, roaming about sponging on the public, and when they have wheedled all they can out of adults, they coax the poor children to give up their half-pence, while they themselves live on the fat of the land." Surely the mantle of Pasquin has fallen upon this uncharitable scribe. SUMMARY OF NEWS. (

1873, August 12).

Yorke's Peninsula Advertiser and Miners' News (SA : 1872 - 1874), p. 1 (Supplement to the Yorke's Peninsula Advertiser). Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article215903751

Departures September 25;— Queen of the Bay,' barque' 391 tons, Wale; master, for Brisbane. Passengers : Anna Maria Canning, . Emma 'Winlo, Robert Winlo, William Jen-am, Ann Jerram, Eliza Chadwick, Henry,; Cornwall, Edwin Taylor, A. Joslin, Emile Argles, and J. Ellen White. SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE. (

1873, November 21).

The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 - 1947), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169484627

Per Messrs. Taylor, Bethell, and Roberts' Queen of the Bay, from London, September 22. For Brisbane-Anna Maria Canning, Emma Winlo, Robert Winlo, William Jet-ram, Ann Jerrara, Eliza Chadwick, Henry Cornwall, Edwin Taylor, A. Josling, Emile Argles, and J, Ellen White. ENGLISH SHIPPING. (

1873, November 25).

Rockhampton Bulletin (Qld. : 1871 - 1878), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article51805206

PRIVY COUNCIL DECISION.

TO THE EDITOR.

Sir—You would not represent me> I have never had any interest in nor communication with the North Australian Company." "I have stood alone, and never identified - myself with any other land-order-holders. I am the last man in the colony to conceive a studied insult to it. My action is precisely the reverse. I have been very jealous for its honour. I Know, and successive Governments have known that, owing to this vexed question of breach of contract, the fair fame of South Australia suffered in the City of London, and it is only reasonable that-as a colonist I. should exult on the majesty of the law, as pronounced unanimouely by all our Judges, being upheld by the highest and purest legal tribunal; in the world. I did my best, when I was permitted at the bar of the House of Assembly to address it, to prevent litigation, its enormous cost, and the present mortifying result, but what can one man do against the wrongheadedness of a Parliamentary majority backed up by the Press— penetrating Pasquin excepted. Together they beat even Government itself when it attempted to make the settlement with the land-order- holders which is now inevitable. Although I have borne the-brunt of odium for the stand I have made in what I firmly believe to be the interests of the colony, I feel convinced that public opinion will some day admit that right and justice to be on the side of the Legislative Council, the judges and, Your obedient servant,

SAMUEL TOMKINSON November 17, 1873

As Mr.- Tomkinson has shown a deep interest in the - North - Australian Company; against Blackmore and a strong sympathy with the plaintiffs in the case, it JaJi mere quibble; about terms to say that he has not identified himself-with the Company. As to the effect of "the Privy Councal decision”, our Correspondent has in his letter taken up more intelligible ground than that which we understood him to assume in procuring the ringing of the bells on Saturday last. Then this judgment was said to be a vindication of the fame of South Australia in London., Now it is spoken of as the "mortifying result" of "the wrongheadedness of a Parliament majority backed up by the Press"—and it, might have been added, of the public too. It is in the "majesty of the law" that Mr. Tomkinson now exults a very different thing from the vindication of She-colony's honour. And, referring to the points we should particularly like to know the extent to which the fair fame of South Australia has suffered in the City of London" through her honest attempt to resist what she regarded as ungracious and unjustifiable demand have our securities been depreciated, have our loan operations been affected in the slightest degree-by; the vexed question of breach of contract. We have the best possible evidence that they have not, and this, in spite; of the determined t attempts of men, who owe everything to the colony, to lower her in the estimation of 'the capitalists' of London. One word for Mr. Tomkinson himself .No one can have the least objection to his exultation in "the majesty of the law," and his delight at the discomfiture of the South Australian Government so long as he rejoices in private but it is really too bad that the whole town should be disturbed by the; ringing of the 'Albert Bells because; of the idiosyncrasies of one citizen. [Ed.] PRIVY COUNCIL DECISION. (

1873, November 17).

Evening Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1869 - 1912), p. 2 (THIRD EDITION). Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197671130

1874

Arrivals

January 14. — Queen of the Bay, barque, 391) tons, Captain Wales from London. passengers : Mr and Mrs Jeram, Miss J. E. White, Miss Eliza Chadwick, Miss A. M. Cunmmings, Miss Emma Winto. Messrs A. Gosling, Edwin Taylor, Henry Cornwall, Robert Winto, Horace Fennell, and Emillie Argles. SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE (

1874, January 21).

The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld. : 1858 - 1880), p. 5. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75468462

Many of these ships travelled from Perth to Adelaide to Melbourne then Sydney before disembarking passengers who had boarded at nay of these along the way at Brisbane – the Queen of the Bay also picked up and bore passengers south from Rockhampton and was later caught south by Emile.

In other Ships Lists for arrivals this arrival is reported as

“Miss Emile Argles", Miss Eliza Chadwick, Miss-A. M. Cummings, Miss Emma Winto, Messrs A. Gosling, Edwin Taylor, Henry Cornwall, Robert Winlo, and Horace Fennell. SHIPPING SUMMARY. (

1874, January 21).

The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 - 1933), p. 4. Retrieved, from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1378164

The Queen of the Bay, from London, was towed up to Messrs. Harris's wharf this morning .by the Francis Cadell. She brings the following passengers : — Mr. and Mrs. Jerram, Miss J. E. White, Miss E. Argles, Mrs. A. M. Cummings, Miss E. Chadwick, Miss E. Winto, Messrs. R. Winto, A. .Gosling, E. Taylor, H. Cornwell, II. Fennell. We could not procure her' manifest in time for publication in this issue. SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE. (

1874, January 14).

The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 - 1947), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169516719

SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE.

ARRIVALS.

January 1.--Queen of the Bay, barque, 390 tons,

Captain Wale, from London. Passengers : Mr. and Mrs. Jerram, Miss J. E. White, Miss Emile Argles, Miss Elisa Chadwick, Miss A. M. Cummings, Miss Emma Winto, Messrs. A. Gosling, Edwin Taylor, Henry Cornwall, Robert Winto, and Horace Fennell. SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE. (

1874, January 17).

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld. : 1861 - 1908), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article130759402

ANYBODY having Communications for EMILE ARGLES, please address A.S.N. Hotel, Brisbane, WITHOUT DELAY. Classified Advertising (1874, January 16).The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 - 1933), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1378036

Same month 464 Government immigrants. J. and G. Harris agents arriving January 10th per Winefred, ship of 1359 tons, Captain Fawkes – from London on October 4th. This also seems to be a sentiment Emile had - although only 21 it seems he may not have expected to ever go home:

THE EMIGRANT

[ORIGINAL.]

After forty years of toil

Before the furnace red,

A workman was forc’d from Albion

To earn his children bread

To earn his children bread

Had he striven hard to live

Alas! that a country should be so rich

And have so little to give!

He gaz'd o'er the vessel's side,

Upon the waters deep;

And though his heart was sad and full

He did not dare to weep;

He did not dare to weep

His mother was standing by —

A woman of three score years and ten

Who’d bid her land good-bye

His wife was ailing and sick,

Her limbs were racked and sore;

But far better he thought to sail away

Than starve on England's shore:

Than starve on England's shore!

That land of plenty and waste,

Where the rich man revels in earthly Joys'.

The poor can never taste.

One last and longing look

At the fast receding shore,

For the emigrant knew that dim outline

He ne'er should gaze on more;

He ne'er should gaze on more

For his locks were turning gray

Twas a painful sight for that man to see

His country pass away.

O Albion great and brave!

O country of glory and fame !

Dids't thou heed thy crying poverty more' '

How brighter far thy name!

How brighter far thy name — ;

Which yet sends loving thrill

Through our hearts ; for spite of all thy fault!

England! we love thee still.

EMILE ARGLES.

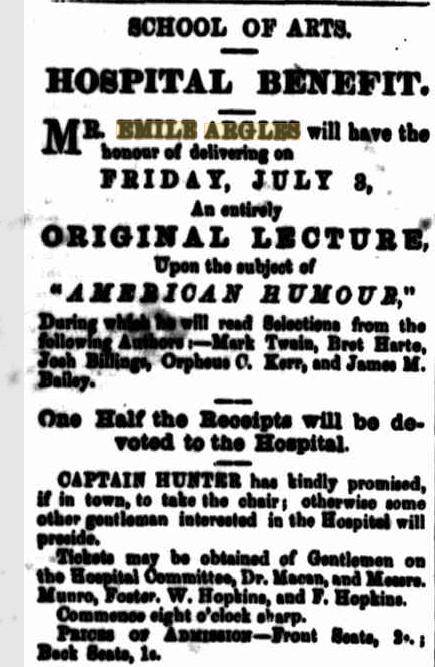

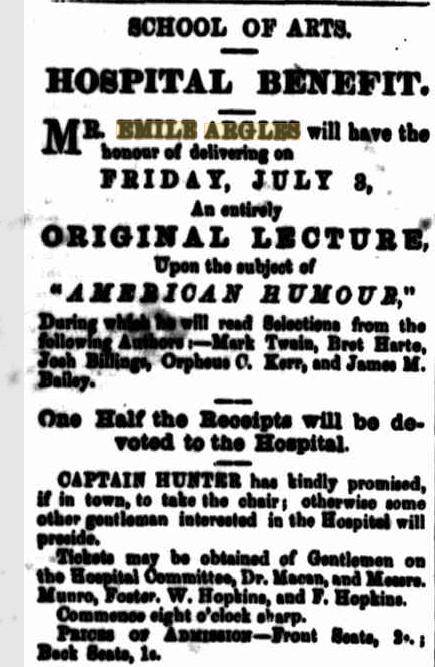

We notice by advertisement in another column that Mr Emile Argles will deliver a lecture on Friday evening next, in the School of Arts, Bolsover-street, and that half of the proceeds will be given in aid of the Port Curtis and Leichhardt District Hospital fund. The subject chosen is the popular one of "American Humour,"and the lecturer proposes to read during the evening some selections from the works of Mark Twain, Josh Billings, Bret Harte, Orpheus C. Kerr, and James M. Bailey. There is plenty of scope in such a subject for the lecturer to instruct as well as amuse, and to show us as Sam Slick once said, "the effect of soft sawdur and human natur." A very pleasant evening is anticipated. PRINCESS BEATRCE. (1874, July 1).Rockhampton Bulletin(Qld. : 1871 - 1878), p. 2 (DAILY.). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92156682

We notice by advertisement in another column that Mr Emile Argles will deliver a lecture on Friday evening next, in the School of Arts, Bolsover-street, and that half of the proceeds will be given in aid of the Port Curtis and Leichhardt District Hospital fund. The subject chosen is the popular one of "American Humour,"and the lecturer proposes to read during the evening some selections from the works of Mark Twain, Josh Billings, Bret Harte, Orpheus C. Kerr, and James M. Bailey. There is plenty of scope in such a subject for the lecturer to instruct as well as amuse, and to show us as Sam Slick once said, "the effect of soft sawdur and human natur." A very pleasant evening is anticipated. PRINCESS BEATRCE. (1874, July 1).Rockhampton Bulletin(Qld. : 1871 - 1878), p. 2 (DAILY.). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article92156682

THE HOSPITAL LECTURE.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE BULLETIN.

Sir,-Would you kindly allow me, through the medium of your valuable journal, to make my excuses to my ticket-holders for the nonfulfilment of my promise to deliver my lecture, “American Humour," at the School of Arts, on Saturday, which had been postponed from the night before ; but the weather was so very bad, that I could not have done so excepting at a heavy pecuniary loss; which, as half the proceeds were to revert to the Hospital, would not have benefited that institution in the slightest degree.

Miss. Gougenheim has done mc the honour to request me to lecture for her, at the Theatre, to-morrow evening, but I will take the first opportunity of giving the lecture at the School of Arts in a few days, when all outstanding tickets will be available.

My sincere and heartfelt thanks are due to his Worship the Mayor, Mr. Hendriok, Mr. Dibdin, and other members of the School of Arts committee, for their kindness on Friday evening, which lessened the heavy disappointment the inclemency of the weather naturally caused me.

I am, etc.,

E. ARGLES. — Mr. Argles requests that the Person or Firm in Brisbane, to whom money was remitted for him, will oblige by communicating with his Solicitor, Mr. Melbourne, at Rockhampton, as Mr. Argles' advices do not mention the name of the Agent or Firm. Advertising (

1874, September 25).

The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 - 1947), p. 1. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169513702

LIST of Unclaimed Letters at the Post office, Rockhampton ; if not claimed on or before 14th December, 1874, will be forwarded to the Dead Letter Office, Brisbane.

DANIEL PETERSON, Postmaster.

Post-office, Rockhampton,

23rd November, 1874.

1875

At Theatre Royal

In Operatic Selections, Overtures, &c.

The Entertainment to conclude. with a New Local Musical Burlesque Sketch, written especially for Mr. and Mrs. Griggs by Emile Argles, Esq., entitled — The nautical Lover. Advertising (1875, November 6). The Daily Northern Argus (Rockhampton, Qld. : 1875 - 1896), p. 3. Retrieved fromhttp://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article213421791

Emile then heads south again - whatever had brought him to Queensland is not to bring him there, to reside, again.

1876

As Harold Grey 1876 – translator of a Belot work as he was not only raised to speak French, as were all well-educated young men and women then, but had a French mother

Adolphe Belot, French novelist and dramatist (1829–90); traveled extensively and settled at Nancy as a lawyer. He won reputation with a witty comedy, ‘The Testament of César Girodot’ (1859, with Villetard); and being less successful with his following dramatic efforts, devoted himself to fiction. Of his novels may be mentioned: ‘The Venus of Gordes’ (1867, with Ernest Daudet), ‘The Drama of the Rue de la Paix’ (1868); ‘Article 47’ (1870); all of which were dramatized. Born in France, at the college of Sainte-Barbe , Belot graduated from the Faculty of Law in Paris, and in 1854 he enrolled in the Nancy Board of Lawyers. After several trips to the two Americas , he devoted himself to letters, publishing the Punishment in 1855 , before approaching the theater with a comedy entitled À la campagne ( 1857 ). In 1859 , in collaboration withPierre Villetard , he gave the Testament of César Girodot , one of the best pieces in the repertoire of theOdeon , a play that counted more than 500 performances.

Belot wrote popular literature of character, if not erotic, at least a "rascal," like Mademoiselle Giraud, my wife , an original, bizarre, immoral work, according to some, moral according to others, which obtained an immense success of curiosity and a circulation of 33 editions, or 66,000 copies ( 1870 ). He was named Knight of the Legion of Honor in 1867. Adolphe Belot. From: (2017, January 1). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Adolphe_Belot&oldid=133211023 .

THE STORY - TELLER.

LAURENT'S VOW.

ADAPTED FROM THE FRENCH OF A. BELOT FOR "THE WEEKLY TIMES,"

BY HAROLD GREY.

Part I. THE BATIGNOLLES TRAGEDY. Chapter III.

The detective bent his steps in the direction of Mariette's room. Notwithstanding the exertions of the doctor, the girl still continued in a deep swoon. On finding her in much the same condition in which he had left her, Moule uttered an exclamation of impatience. Everything depended on the revelations this girl would make on regaining the power of speech. At length the police-agent who had been sent in search of Laurent Dalissier returned. The detective glanced at his subordinate. The man was alone. “Well ?" demanded Moule briefly. " M. Dalissier was not at home," answered the agent. " Cannot they tell you where to find him ?" ' No, nor when he is likely to return." 4 Go on. I am listening." " He went out at 9 o'clock this morning ; he returned for a few moments in the afternoon to dress, and he has not since been seen." Moule frowned ominously ; time was being lost when every moment was precious. ... THE STORY - TELLER. (1876, February 26). Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 - 1954), p. 9. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article219429097

THE STORY - TELLER.

LAURENT'S VOW.

adapted from the french of a. belot for "the weekly times,"

BY HAROLD GREY.

— w Part I. THE BATIGNOLLES TRADEGY.

Chapter VI. — ( Continued. )

At this point Laurent was interrupted by the entrance of an usher, who handed the magistrate a large sheet of paper folded in two. M. Thurier glanced carelessly at the document, and placed it in a corner of his bureau.

"That will do," said he to the usher ; and then, turning to Laurent, motioned him to proceed. "A week passed," continued the young man, "and I had almost forgotten the fatal soiree, when I received another invitation from Suchapt. The remembrance of my humiliation returned a thousandfold. I longed to revenge myself, and now an occasion offered, why should I not accept it ?... (TO BE CONTINUED). THE STORY-TELLER. (

1876, March 11).

Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 - 1954), p. 9. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article219428260

THE STORY-TELLER.

LAURENT'S VOW.

ADAPTED FROM THE FRENCH OF A. BELOT FOR "THE WEEKLY TIMES,"

BY HAROLD GREY.

Past I. THE BATIGNOLLES TRADEGY.

Chapter YII. — (Continued.)

At length all the rooms of the apartment having been visited, the commissary's explanatory discourse came to an end. " But, monsieur," said Laurent, to the magistrate. "in all this I can see nothing by which

you conld gain a clue to the assassin — no trace —no indication." M Thnrie crave an anoTV shudder. "He is...

The work he has translated bears resemblance to a play published shortly before he came to Australia, but would also have been available here through imports of books and publications - Le Parricide - written by Belot in collaboration with Jules Dautin, Dentu, Paris. Ulm le Parricide (1872),

Le Parricide, drama in 5 acts and 7 tables, by M. Adolphe Belot.Paris, Ambigu-Comique, October 6, 1873. Unknown Binding - 1874

By Adolphe Belot (Author);

Parricide , a term derived from the Latin parricidia (assassin of a close relative), means:

1. The act of murdering his father, his mother (in the latter case, we speak more specifically of matricide ) or another of his ancestors, or even any close relationship. 2. The act of murdering an established person in a relationship comparable to that of a parent (for example, the leader of a country).

3. The author of this act.

Amid much that is nasty, Adolphe Belot has produced one or two excellent police novels; Le parricide and Les etrangleurs rank with, if not above, Gaboriau in their careful elaboration of the avenging processes of the law. Alexis Bouvier, again, has concentrated some of his best efforts upon the chase and discovery of malefactors. Detective Fiction in France, article in The Saturday Review 1886

And then:

AUSTRALIAN TELEGRAMS.

from our own correspondents,

Albury, 15th March.

Harold Grey, alias Emile Argel, was remanded to-day, at the police court, on a charge of forging a cheque, and uttering the same, to John Cleeland, Albion Hotel, Melbourne. AUSTRALIAN TELEGRAMS. (

1876, March 16).

The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202160197

The Border Post reports that on Thursday morning Detective Foster appeared at the Albury Police Court and produced a warrant for the arrest of Emile Argle, alias Harold Grey, alias Russell, who was in the custody of the local police. The accused was charged with having forged the name of Mr. Howard Willoughby to a cheque for £3, drawn on the Colonial Bank, Melbourne, and passed to the bar-tender at Mr. J. Cleeland's Albion Hotel, Melbourne, on the 28th February ult. 'When Foster went into prisoner's cell on the previous day he said "Good evening, Foster, expected you would come. What did Charley the barman say? What did Cleeland think ? I suppose Mr. Clarke is put about? Foster told him that Mr. Mark Clark was very angry at his conduct and showed prisoner the forged cheques and he acknowledged to that produced in the warrant. " Prisoner : Here Foster old man, draw it mild ! draw it mild ! But it does not much matter, I suppose." The remand was granted, and the accused was escorted to Melbourne by the afternoon train from Wodonga on Thursday. He is charged with having forged the name of Mr. Howard Willoughby to a cheque for £40. NEWS OF THE DAY. (

1876, March 20).

The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202162860

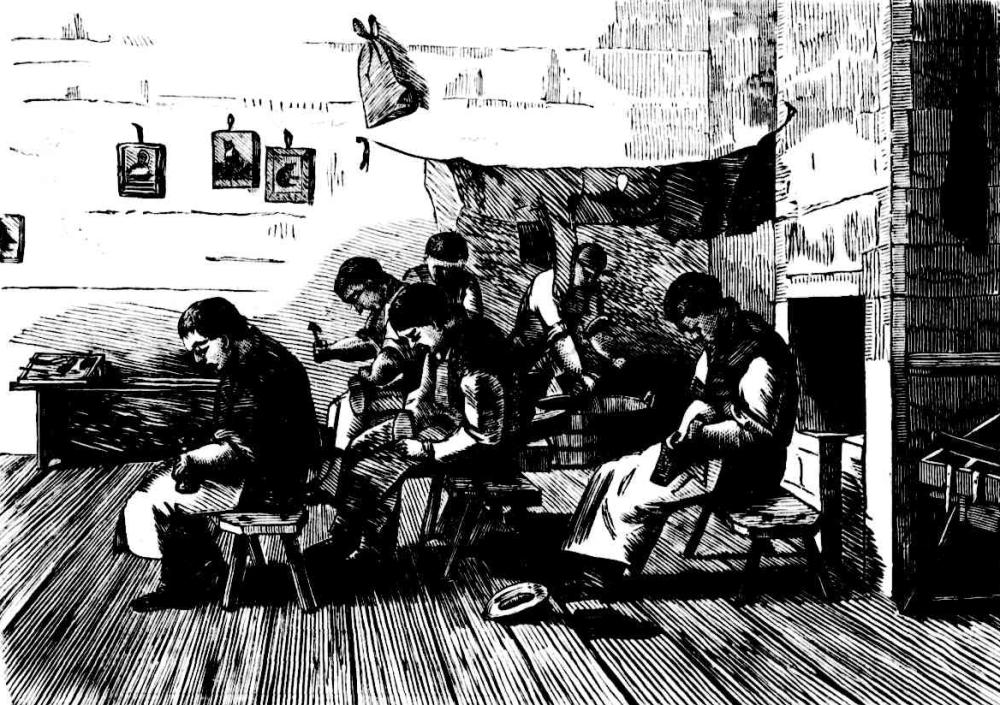

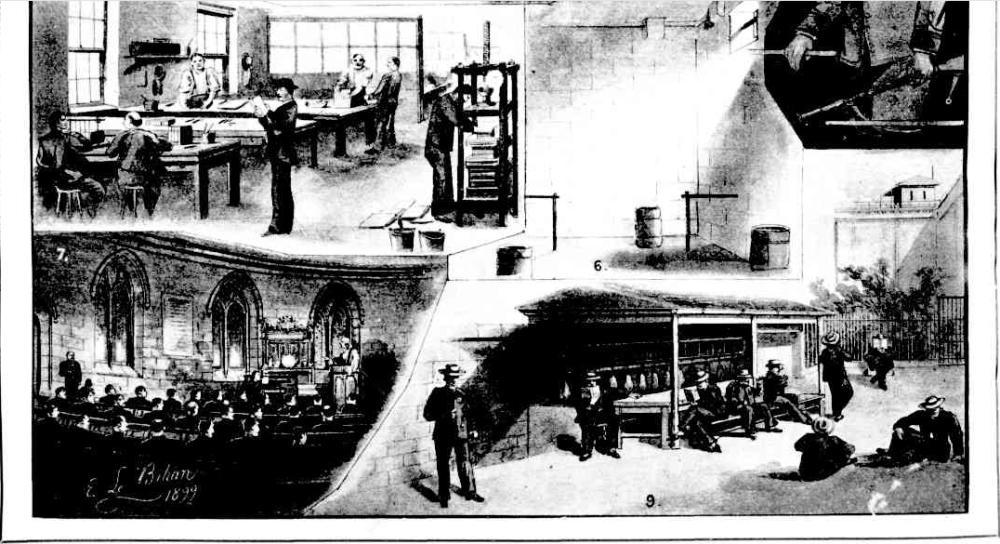

Emile Argle, also known as Harold Grey, was placed in the dock at the City Court last Friday, on a charge of forging and uttering a valueless cheque for £3 to Mr. Cleeland, of the Albion Hotel. It appeared that the prisoner had been employed by Mr. Howard Willoughby to translate a French novel for publication. He was paid for his work at various times by cheques on the Colonial Bank, but at the conclusion of his literary work he asked Mr. Willoughby for a loan of £3, which, however, that gentleman declined to grant, he then wrote out a cheque for the amount, and having placed Mr. Willoughby's signature to it, obtained cash for it at the Albion Hotel. He then took his departure for Albury, New South Wales, |where he was arrested by the local police, and subsequently handed over to the custody of Detective Foster. It was stated that the amount of the cheque had been paid by the prisoner's friends, but the magistrates declined to deal with the case, and committed the prisoner for trial. GENERAL NEWS. (

1876, March 29).

Hamilton Spectator (Vic. : 1870 - 1918), p. 4. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article226036816

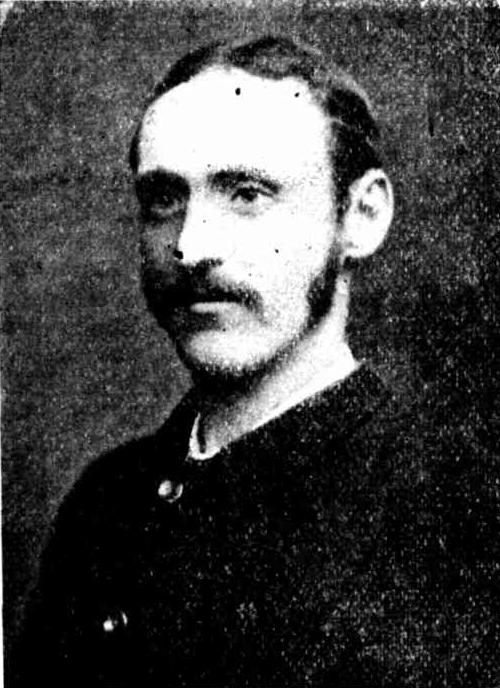

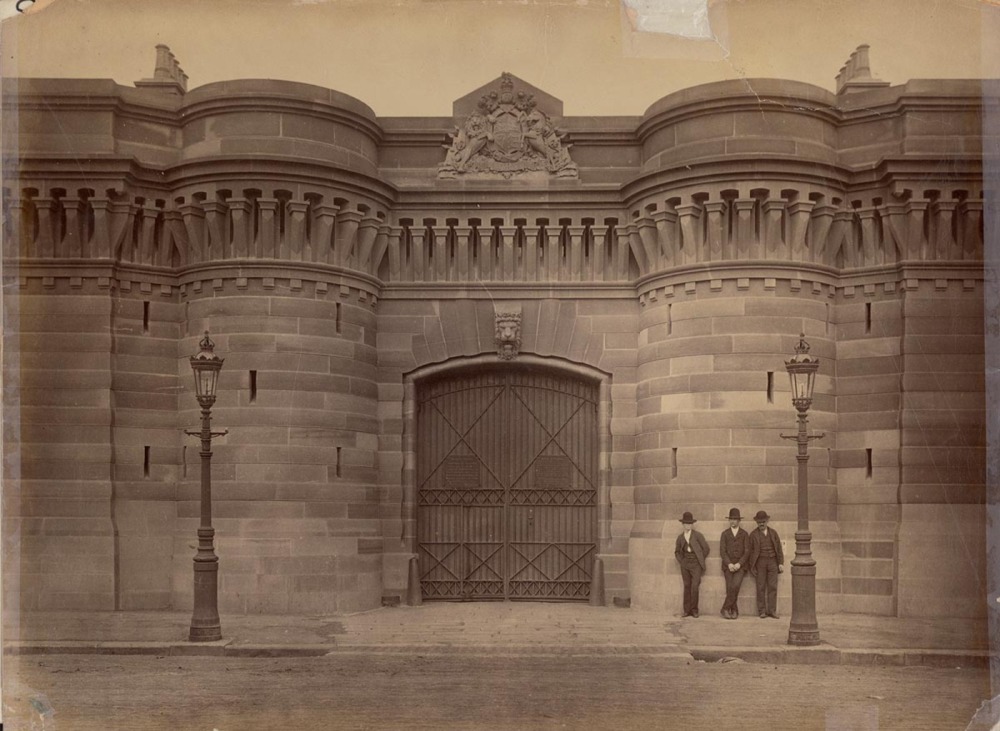

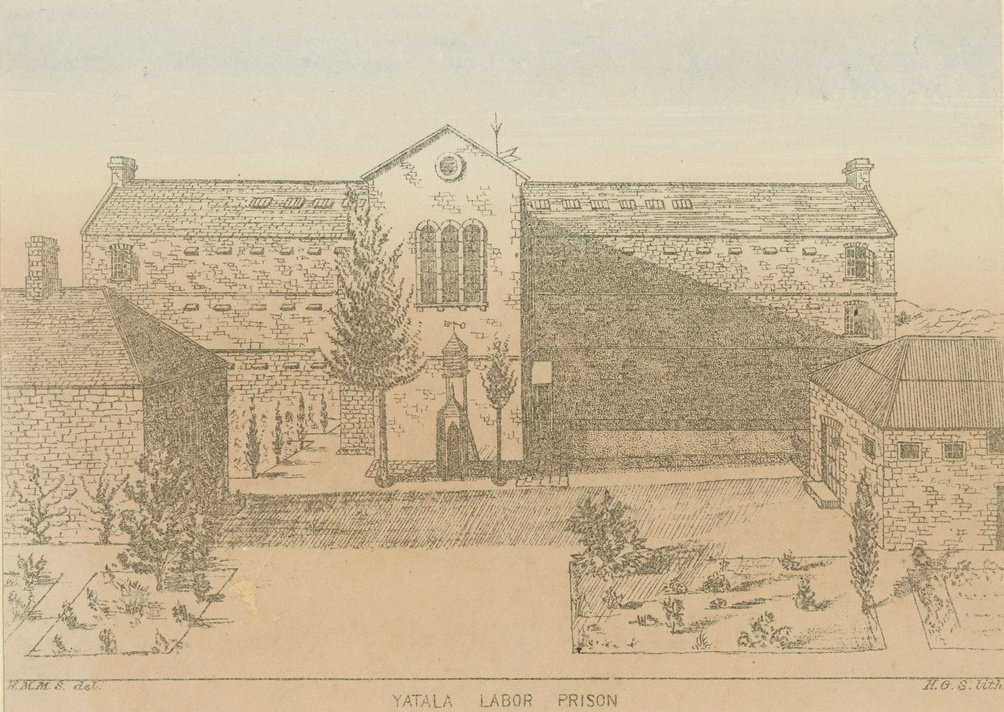

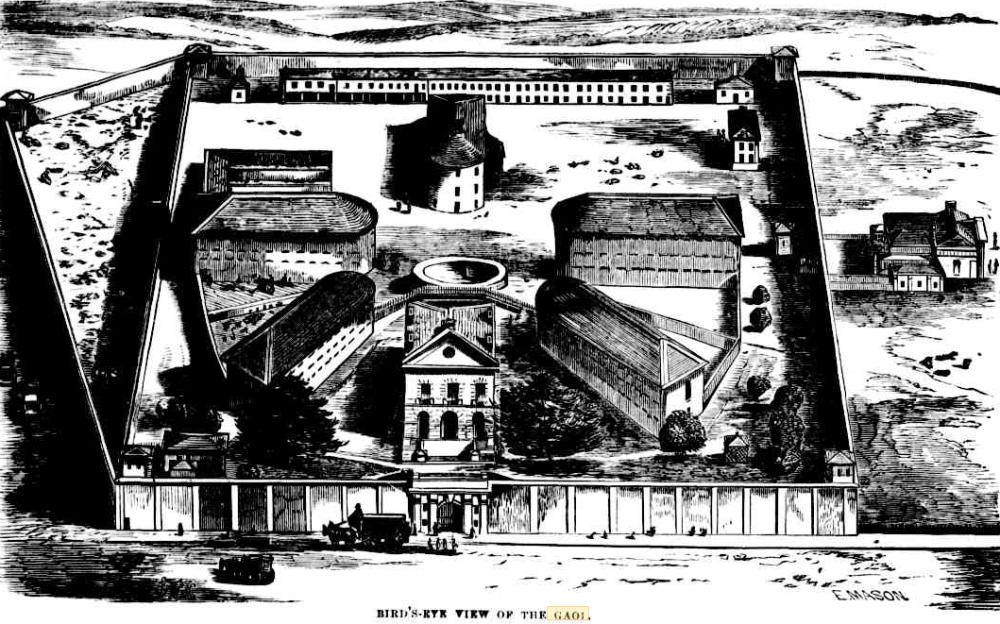

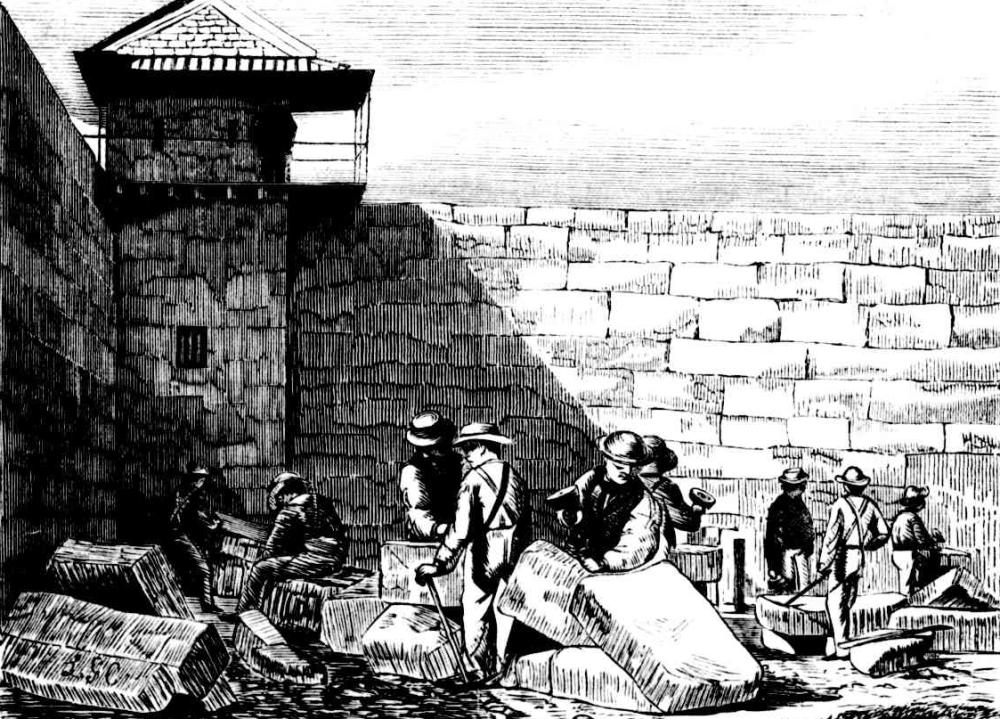

Emile Argle a young man who for some time past has been earning a living by literary work in Melbourne, under the name of Harold Grey, pleaded not guilty to forging the name of Mr. Howard Willoughly to a cheque for £3 on the Colonial Bank, The prisoner obtained cash for the cheque at the Albion Hotel, and was subsequently arrested at Albury. He was found guilty, and sentenced to twelve months' hard labour. GENERAL ; (

1876, April 8).

Advocate (Melbourne, Vic. : 1868 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article170431535

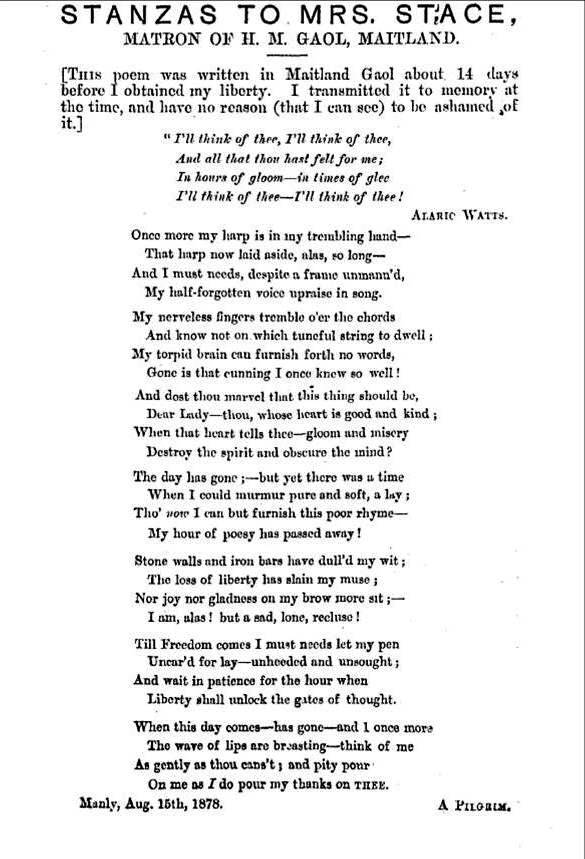

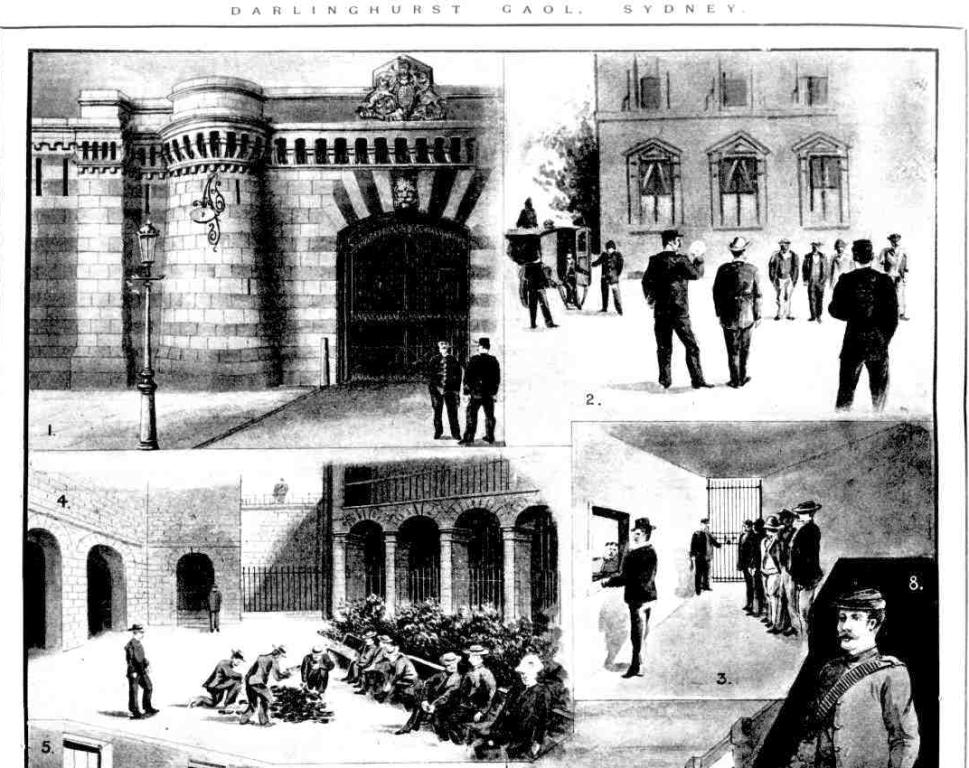

He was sent to Pentridge according to later reports, which he vehemently refutes in My unnatural life / by H. Grey. Harold Grey 1878-1879 - 30 pages

Our attention has been called to a printer's error in the passenger list of the City of Agra, as published in our issue of -Tuesday. A saloon passenger, whose name is Frank Argles, is therein represented as Frank Ayles. We understand that Mr. Argles has friends in the colony who will be glad to be apprised of his arrival, and we trust that this correction will be seen by them. (From the Gympie Times.) (1876, July 20).Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld. : 1860 - 1947), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article148510984

ARRIVALS-NOVEMBER 28.

. Florence Irving (s ), OOO tons, Captain Phillips, from Cooktown via intermediate ports. …F. Argles SHIPPING. ARRIVALS.—NOVEMBER 28. (

1876, November 29).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13384334

FATHER NICEPHORUS, whom Byron immortalised in “Childe Harolde" as the “Caloyer," died recently at the age of 117 years. ORIGINAL POETRY. (

1875, December 4).Advocate (Melbourne, Vic. : 1868 - 1954), p. 14. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article170308038

Arrived December 3

You Yangs, S.S., 800 tons, Charles Ashford, from Sydney. Passengers-saIoon: Mr. and Mrs. Wardle, Mrs. Levy and two children, Mrs. Parker, Miss Parker, Miss Crawford, Mr. F. Argles, ARRIVED. (

1876, December 9).

The Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 - 1946), p. 13. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article142995544

1877

ENGLAND. THE ALLEGED DETENTION OF AN ORPHAN GIRL IN A CONVENT.

The following is a complete exposure of a slander, originated by the London Standard, which has gone the rounds of the Protestant press— Sir,— Marie Jackson, the orphan girl referred to in the recent articles in the Standard, has made a declaration at the British Consulate in Paris and before six disinterested witnesses, traversing the sensational paragraphs and correspondence published by you. This she has done of her free will, and we are instructed to forward her statement; for insertion. We enclose a certified copy thereof; the original will be produced to you by our London agents in the course of to-morrow. — We are, Sir, your obedient servants, ANDERSON and ARGLES. 17, Boulevard de la Madeleine, Paris, December 1.

'I, Marie Jackson, now residing at the Convent of the Assumption, at Auteuil, in France, wish to state, as I have already done by three letters which were (? not) believed to have emanated from me, because they were not attested, and as I think it necessary for my own reputation and that of the convent in which I am, to relate the calumnies published about me in the Standard newspaper, I find it necessary to make the following declaration :—? ' As to the suicide of which so much has been said, it is true that I once put in my mouth a little piece of Haytian money for a minute. The second time I put some little berries, which were in the garden into my mouth, and I was not even indisposed after so doing. As to my evasion, I can only say that I ran one day into the convent yard which leads into the street, but I came back immediately. If I had wished to run away I could easily gave done so since then, for during the summer holidays I went out several times with a very respectable lady, and I could have rncdo say er.capo ao easily oa possible. I should neves.'1 have thought that such a ehildioh action could have been ascribed to a wish to commit; suicide. It is true that I imprudently told all this to my aunt, but with out thinking she would make such fuss of my trust in her, and I bitterly regret, and from the bottom of my heart, that my light words could have made any one believe that I seriously wished to commit suicide. After Easter I wrote home. The things which are made to appear so odious now were not induced by any hatred against the convent and the nuns, who have always been extremely good to me, but merely to chow my aunt how very grieved I wan at being again, separated from her. The words I employed were, I feel, far too violent; and I sincerely regret having written them, since it is by means of these letters that attacks have been made on persons to whom I commenced to be attached, particularly since my illness. It is true that I said I did not like the convent ; the school life was extremely disagreeable to me, but I never said the same as to the nuns, and I can prove this, because at Easter I came to see them, and even supposing that I did not like them of that, time, can I not have changed my mind since ? No pressure either moral or physical, was ever used to make me a Catholic, and during several months the Roman Catholic doctrines made little or no impression upon me, but at last I saw clearly, by studying and examining them myself, that the Roman Catholic religion was the only true one. Yet I still hesitated, for I knew that my Protestant relations would be severely displeased if I took any such step. This is why I made my first communion only in July, although convinced of the truth before. I was confirmed at the end of July, and since then I have followed the practices of the Roman Catholic religion, and by no means regret having done so. I hope, by God's grace, to remain in these sentiments till the day of my death. 'No cruel treatment was ever exercised upon me on any occasion. On the contrary, the nuns (and one in particular, who has always been to me like a real mother) have always treated me with the greatest kindness, particularly since my illness. When my aunt came to see me I was already better, and certainly not on the verge of death, unless I had had a relapse, and am now in perfect health. ' I wish also to affirm that the letters printed in the Standard under my name were written by me and o£ my own' free will 17, Boulevard de la Madeleine, this day of December, 1876. ' Marie Jackson.' ' Signed by the above-named Marie Jackson in the presence of Napoleon Argles, Solicitor, 17, Boulevard de la Madeleine, Paris. ' W. G. A. Draee, gentleman 80, Broadway, New York, U. S. A., C. S.-Wasok, Student, Boston, Mass., U. S. A. ' J. Mtjllee, Regociant, 12, Hue pevdonnet, Paris.' ' A. Brocarii, Regociant, 7, Iluo de Provence, Paris. ' F. Anderson, Solicitor, 17, Boulevard de la Madeleine, Paris. 'Declared afc ths British Consulate, at Paris, by the above-written Maria Jackson, this 1st day of December, before me The ' (Signed) Henry Willoughby, Consular British Vice Consul at Paris. Seal. ' We declare the above to be a true copy of the original declaration before us, ' Anderson and Argles, Solicitors. ' 17, Boulevard de la Madeleine, Paris.' Home and Foreign. (

1877, February 24).

Freeman's Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1932), p. 5. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115375130

General Post Office,

Sydney, 15th March, 1877.

No. 6.

LIST OF LETTERS RETURNED FROM THE COUNTRY, AND NOW LYING AT THIS OFFICE UNCLAIMED.

PARTIES applying for Unclaimed Letters at the General Post Office, are requested to give the correct number of the Letter, with the date and number of the List in which they may hare observed their names, as such reference will materially facilitate delivery. Parties in the Country making written applications, in addition to the former particulars, are requested to state where they expect their Letters from, and any other information tending to prevent an unnecessary transmission of Letters.

Ship Letters.

10 Argles —, Esq., Deniliquin

11 Argles Frank, Deniliquin. No. 6. LIST OF LETTERS RETURNED FROM THE COUNTRY, AND NOW LYING AT THIS OFFICE UNCLAIMED. (

1877, April 23).

New South Wales Government Gazette (Sydney, NSW : 1832 - 1900), p. 1631. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223759239

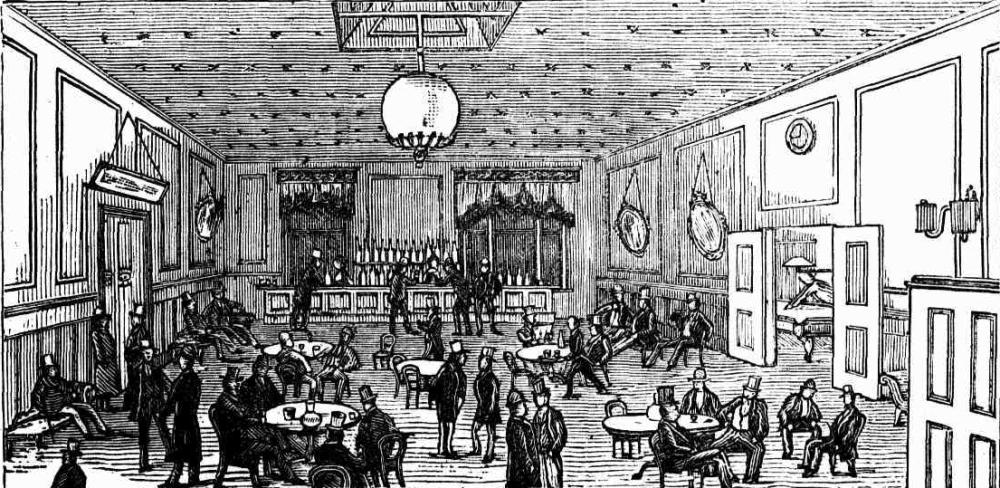

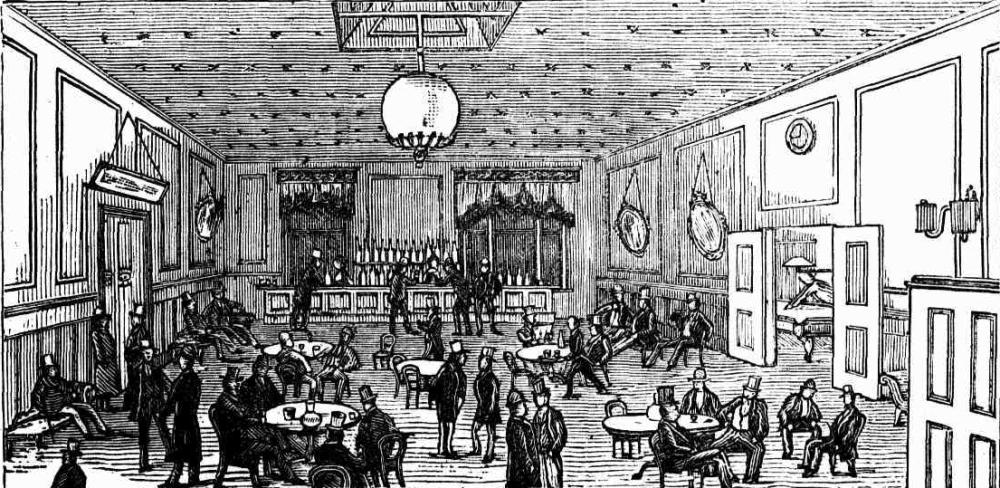

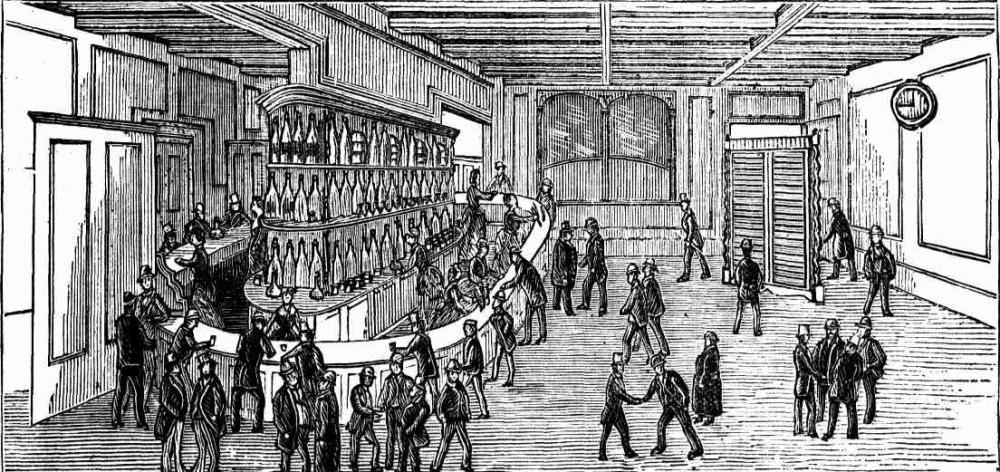

UNORTHODOX SYDNEY.

By a Pilgrim

No. 2, A NIGHT IN THE CITY REFUGE.

UNORTHODOX SYDNEY.

By a Pilgrim

A SLY GROG SHOP

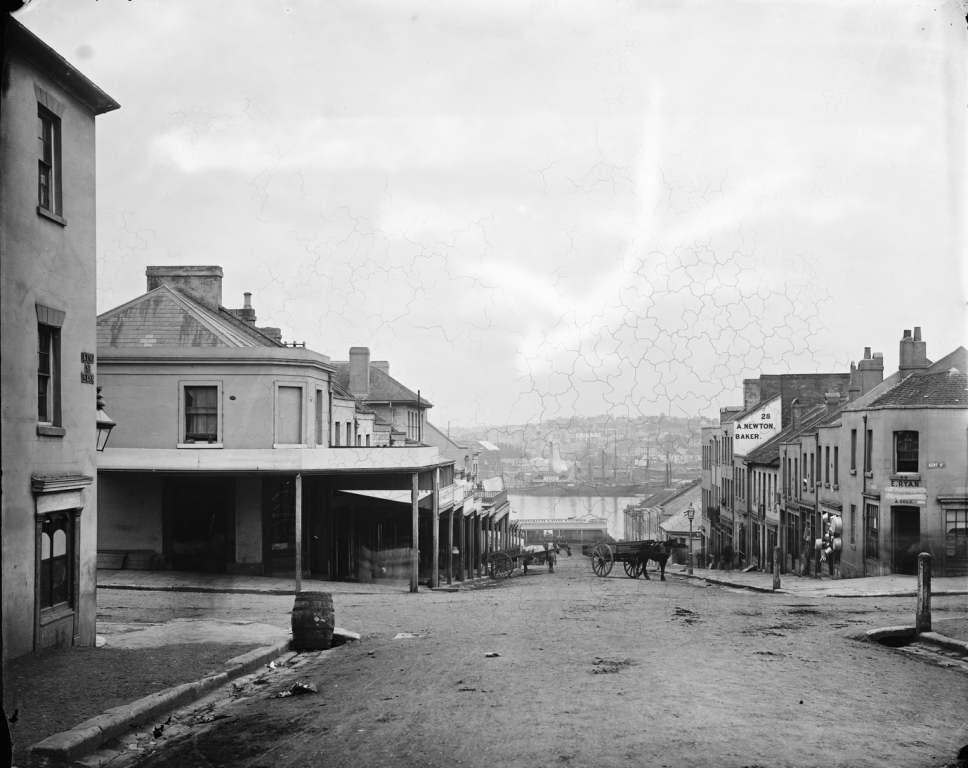

ONE — two— three ! Three o'clock, ye shades of departed Charlies !— three o'clock and a cloudy morning. As I gaze around, a sense of this virtuous city’s somewhat oppressive morality lies heavily upon me. Save a few swiftly flitting night birds, there in scarcely a soul stirring. The rich but honest merchant slumbers tranquilly upon his couch of down; the conscientious and long-suffering publican peacefully reposes beside the wife of his bosom ; and even the humble baked potato-man has retired to his chaste though lowly dwelling, and, happy in the possession of a pure conscience, has successfully courted the balmy God, and his genial soul is wafted upwards into Dreamland.

The classic province of Kent-street is clothed in the dusky garb of night, and the ghostly silence which envelopes that mysterious neighbourhood is broken only by the muffled clink of the coffee cups, containing the choice beverage dispensed by a wandering purveyor Moka of Araby, at the modest— not to say insignificant— price of one penny the half-pint. I stand pensive at a short distance from the stall of one of these enterprising tradesmen. Stand pensive because I am contemplating human nature in one of its most interesting forms. Let me endeavour to make a pen-and ink sketch of the motley assemblage before me.

Place aux Dames! Phyrne and Chloe, sauce in hand, are placidly lapping up the dark brown fluid. They are brilliantly attired in light purple gowns, the fronts of which are ornamented with a bizarre tracery suggestive of the stains of malt liquor. These charming creatures are engaged in carrying on an animated conversation with a tall emaciated youth who, to judge from the disordered condition of his dress has been ‘making a night of it,' and is now apparently endeavouring to manufacture a morning also. This roystering blade, whose clothes are the counterpart of the garments we see marked ' very chaste' in the windows of cheap tailors, has pushed his ‘Champagne-Charlie's hat as far on the back of his head as the laws of gravity will permit; and the knot of his thunder-and-lightning cravat has worked round beneath his left ear in a manner strongly suggestive of the hang man. To the right of this trio stands an individual, the filthiness of whose garb is only paralleled by the hideousness of his phyziognomy. The man’s face, which is of that putty whiteness so peculiar to the criminal classes, is garnished by a beard of ten days' growth; his eyes, like deeply-sunken beads, possess the steely glare of hereditary villainy, and he glances here and there uneasily, as though in fear of being 'wanted' by some active end intelligent officer. In order, I suppose, to exhibit the muscular proportions of his manly chest to their best advantage, the gentleman wears his grimy shirt unbuttoned at the neck, while around his dusky throat is entwined an eel-like 'belcher' handkerchief, after the most approved pugilistic fashion. His hat, which in form resembles an inverted pudding basin, is garnished, as though in ghostly mockery of the prevailing mode, with a dingy wisp of some unknown fabric twisted to resemble a puggaree. His trousers, which are composed of a material known to the initiated as dungaree, fall in a series of graceful folds over a pair of dilapidated high lows, the uppers of which appear to have no connection whatever with the soles. The group is completed by a couple of sailors, who are in that condition known as ''three sheets in the wind,' and who occasionally vary the monotony of coffee drinking by exchanging mortal defences and vows of eternal friendship. As I approach the stall for the purpose of observing the company more closely, Chloe takes exception to my appearance in a remark in which she stigmatizes me as 'the bloke in the fentail banger !' while such miscellaneous epithits as, ' swell out o' luck,' ' barber's clerk,' and 'the bloomin' dock' are freely bandied about. Strange to say, my advent appears to be a source of annoyance to the company. Even the coffee stall keeper, whom I endeavour to propitate by the expenditure of sixpence, gazes upon me with an evil eye. My endeavour to draw him out is a signal failure. To my modest inquiry d~' How is business?’ He replies gruffly ? — 'Well not so good, but wot I'm willin' to sell out to yon fur a thousn' pun.'

Not having any repartee handy, I turn to the gentleman in the dungaree pantaloons, and inquire if ho can give the current quotation of laborers' wages. This apparently inoffensive question appeared to give great offence to that individual; for, turning upon me with an oath, he says savagely,

' Seventy four pound two and tuppence farden and find your own kerosene!' The sally received with great applause by the company generally, and I walk away from the coffee stall amid a derisive howl from the whole party.

About five minutes later I stand at the outer section of Kent and King streets musing on the scene I had just witnessed, when I see my picturesque friend making in my direction. Strolling up, he touches me on the shoulder. I involuntarily recede a few paces, when he thus addresses me:' 'Say, mate, could yer do a nip?'

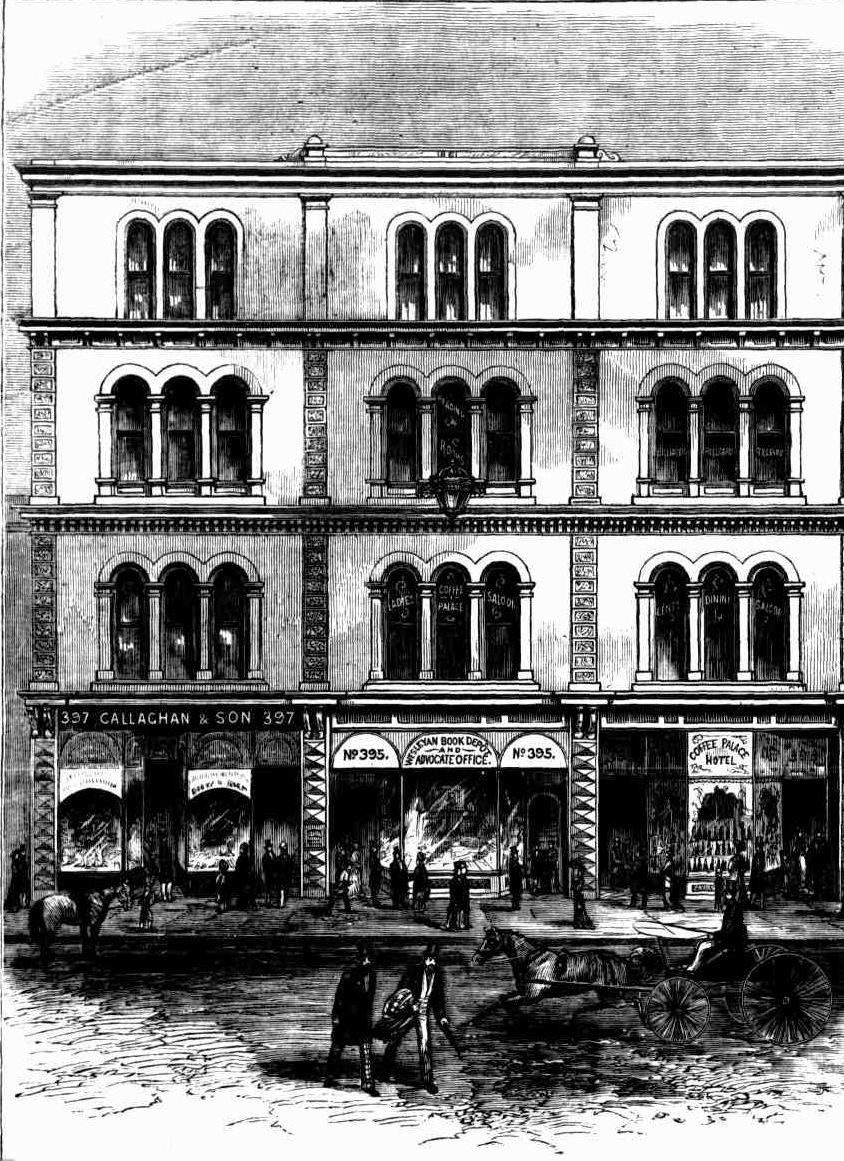

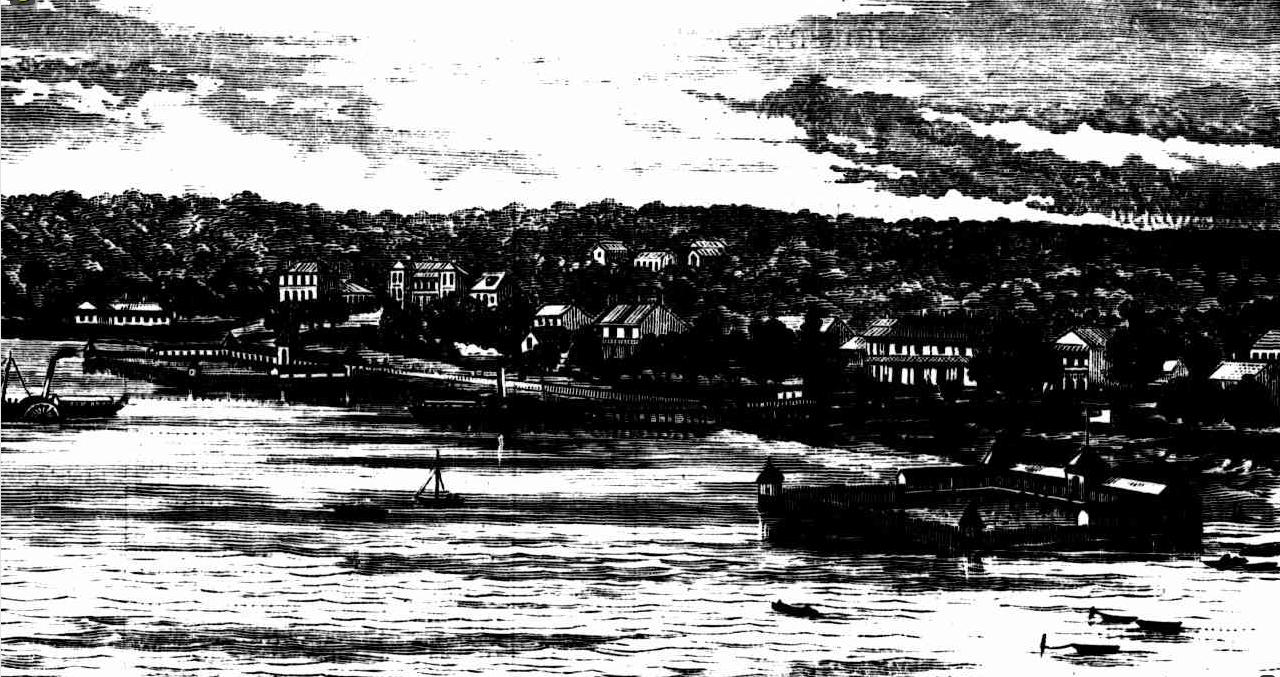

Looking west down King Street from Kent Street (showing A.Newton's bakery at no.28-30, Star of Peace Hotel and E.Ryan's store), Sydney by American & Australasian Photographic Company. Image No.: a2825050, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Scenting an opportunity for the manufacture of copy, I replied that nothing could give me greater pleasure, but that unfortunately an arbitrary Licensing Act precluded all possibility of alcoholic refreshment at that hour. But he is equal to the emergency. ' I know a crib,’ he says, hoarsely, ' where there's some slap up tipple.' Then he adds hastily, 'But you’re right, ain't yer — you won't put a bloke away ? I hasten to assure him that if by 'putting away' he implied giving information to the police, I shall certainly do no such thing. This reply pleases my interlocutor so much that he laughs inwardly in a manner extremely unpleasant to behold, and says, ' Well you ain't a bad sort of a swell, in spite of yer plug hat: so come along er me.'

With this he dives across the road, and we proceed at a rapid pace in the direction of the shipping.

Treading several evil smelling thoroughfares, we cross a small yard, in which it seemed some person had years before, sowed a crop of second-hand slabs and old kerosene tins, which in the course of time have yielded fruit one hundred fold, we arrive at the back door of a brick cottage in the last stage of dilapidation. Motioning me to keep close to him, my companion murmurs some (to me), unintelligible words through a chink in the door, ;- No answer. Unintelligible phrase repeated, garnished with a shower of highly annoyed ' adjectives, and a richly worded anathema upon I some unseen person's eyes, limbs, and anatomy generally. This apparently has the desired effect, for the bolt is slowly withdrawn from its socket, and we enter.

Hardly have we crossed the threshold than the door is closed by some ; invisible agent, and all is darkness. As I stand alone a feeling of the insecurity of my position comes rather unpleasantly upon me. I try to recall the articles which I have in my possession. Money — a pound and some loose silver — a meerschaum pipe, part of canto I of an epic poem ; a silver watch, a present from a confiding uncle; and a couple of letters, beginning ' My darling duck,' from— no matter- whom, are all that I can recollect on the spur of the moment. Besides these articles, however, I possess a little plaything, whose component parts are lead, whipcord and whalebone —a trifle that would stand me in good need, did my friend contemplate violence. Any slight uneasiness I may entertain is soon dissipated by his requesting 'a strike.' Interpreting this into a demand for a match, I hand him my box on which he promises to 'show a glim' after that mystic interval which is comprised within a ' brace of shakes.' The first object that meets my gaze on the candle being lighted is an exceedingly diminutive boy, who stands by the door, and who is looking up into my face with a strange mixture of surprise and dislike. He is a pretty child, with an abundance of fair hair, and quite an angelic expression of countenance. His attire airily consists of a little garment that barely reaches to his fifth ribs and, on the whole, he presents rather a comical appearance. I nod pleasantly at the little fellow to encourage him, but instead of responding to my overtures, he trots up to my needy mentor, and exclaims shrilly — ' So you've rose a splodger, Sladdy, hav you .? Oh, lamb him down tilt he ain't gob a caag — lomb him down !' and dances about the damp floor with an appearance of great relish. '

What does he mean by a aplodger ?'' I ask of 'Sladdy,' as soon as that worthy'a mirth had subsided. The man laughed. ' The little warmint !' says he admiringly. ' ' Splodger is a cant term for a bushman on the apree. But come, yo'll have the liquor now. You're good for half a bull ?' As I do not appear to be quite clear with regard to this, he puts his question in an amended form. 'Half-a-crown won't break yer?' I reply that the sum he mentions lies within the compass of my means ; on which he nods and says when he has filled his 'gift' he will bring out the spirits. He thereupon produces the blackened stump of a clay pipe, and proceeds leisurely to cut up some tobacco, while I take the opportunity of looking around me; having previously seated myself upon an empty gin case. Faintly illumined by the flickering light of a common tallow candle, the room appeared to be a small place, some fifteen feet square. Not a vestiage of paper-hanging is on the wall or ceiling; and not a particle of furniture of any description is to be seen. The two windows at the farther end cannot boast a single pane of ill glass ; to counterbalance which, the frames are completely blocked up by squares of tin, pieces of paling, and bunches of rag. In one corner of the den a few sheepskins are opened upon the dirty ground, upon which the little boy has stretched a himself; and a few feet from the child lies an object which resembles a heap of rags. The whole place— floor, wall, and ceiling — is blackened by a thick coating of smoke af and grease ; and the poisonous cbse-e neas of the atmosphere is almost unbearable. I have hardly completed my survey of the apartment when my host rises, and we walking towards the heap of rags I have mentioned, gives it a kick. A groan follows, and slowly from the horrible bed there rises a woman, yes, a woman ! a creature enveloped in a ragged skirt with a fragment of blanket drawn over her shoulders; a blear-eyed, diseased, and drunken creature— but yet a woman. Shading her eyes with her shrunken arm, she leans against the wall and contemplates me ' Now then,' says the man, shaking her roughly 'where's the stuff?' A faint gleam of intelligence comes into the woman’s eyes as she kneels in dorm upon her bed and drawn out a square glass bottle together with two tin pannikins Pushing the drinking vessels she comes towards me. 'Part thagreod, mate,' says he; whereupon I hand him the stipulated half-a-crown, requesting him, however, to fetch me a little water. Murmuring something I could not quite catch, the feHor/ tossed off his own portion of the spirit;, and taking up his pannikin, passed out into the yard. Quick as thought the woman approaches me. ‘For God's sake, sir, can you help a poor wretched creature?' she murmurs; 'take pity on me ! I'm dying, and shall never get out of this.' My answer is to place some silver in

' her trembling palm. As I am doing so, the woman, in her haste to conceal the money, steps sharply brick, and accidentally treading upon the bottle, which lies upon the brick flooring, it is overturned and broken into twenty pieces,, while the spirit (whose odour is a compound of vitriol, banzine, and carbolic acid) trickles in a small rivulets towards the door. At this juncture Sladdy reappears, bearing the water. Catching eight of the broken bottle, however, he drops the pannikin, rushes at the woman, and they roll upon the bed of rags fighting and tearing at one another.

The little boy, who is awakened by the noise, sits up upon his sheep skins, and cries : ' Go it, mother! land him a cuffer! let him have it !' and is to all appearance vastly entertained by the proceedings. I tarry a moment to assure myself that no harm will ensue, then softly opening the door of the den, I flee swiftly out into the fresh air.

BIRTHS. . _ ARGLES.— 18th, at 17, Boulevard de la Madeleine, Paris, the wife of Napoleon Argles, solicitor, of a daughter. Friday 22 June 1877, London Evening Standard, London, England

Fiction Story By 'Harold Grey' – 1877, reflective of what he may have been doing while in Queensland

After this follows just one example of the kind of articles he was then writing in Sydney(they were all alike this) and which led, some of his contemporaries later stated, to him ending up in gaol again

TALES AND SKETCHES.

-A STORY OF CENTRAL QUEENSLAND.

BY HAROLD GREY.

Author of Votarica of Thespis, &c.

PART II.

Three weeks have elapsed since Percy Graham's arrival at the Sirius Downs Hotel. The fever has left him, but he is prostrated with weakness.Comfortably reclining on a canvas chair, in the shady verandah of the house, Percy is gazing dreamily at the landscape before him, and listening to the gurgling of the adjacent creek, which winds like a hue of silver far away across the distant plains. Some books and papers are strewn about the floor at his feet, and a handsome dressing case, filled with every'necessity, lies on a stool near him ; while on a small table to his right are fruits and cooling drinks, all evidently provided by some loving hand.

" Well !" soliloquised Graham, "it seems strange for the so-called muscular human frame to be reduced to a state of such unconscionable torpor. A child of six could knock me out of time in as many minutes. This bout will teach me to have some regard for the constitution with which nature has endowed me. However, I might be worse off, that is -one comfort.-Hullo ! who's this ? Jack Bowring, by all that's good !"

As he spoke a horseman cantered up to the house, and dismounting, strode up to Percy, and shook him by the hand.

" Well, old man, how goes it?" said the new arrival, who was none other than John Bowring, Esq., M.L.A., proprietor of the adjacent station of Tulgarra.

" Pooh ! you're looking quite rosy. You'll be kangarooing .at Tulgarra in another week. By-the-bye, you must be getting tired of this crib."

" Oh, I don't know. I'm not up to much excitement, you know. As for leaving this before another fortnight, it is, I fear, out of the question."

A long whistle was Mr. Bowring's rejoinder.

"Don't make that hideous noise, Jack," said Graham, irritably ; " it goes right through a fellow's head."

The young squatter glanced earnestly at his companion, .and th eh sitting himself down on the edge of the verandah, placed his hand on Graham's arm.

"Look here, old fellow," said he; "I want to speak ^seriously to you."

"Oh, don't, please," said Percy, plaintively: "I'm not -strolls enough for gravity."

"Well, then, I'll be serio-comic."

"That will be worse; for it reminds one of the music

?halls."

"No ; but listen. There is a certain little bird--"

" Come ! no natural history, I'm not up to ib in my present

.emaciated condition."

"A rumour then," continued Bowring; "there is a rumour that you are am petits soins with the charming Polly."

A flush came into Graham's pale, thin cheeks.

" And supposing I were, what theu ?" asked he, sharply. Bowring tapped his boot meditatively with his riding

whip.

" Then you admit it?" he asked, after a pause. " 1 never was great at admissions."

"Look here, Percy," said his friend earnestly ; "I have known you now a long time. We were college friends together, and are even related by marriage. I have thus a right to speak my mind to you. I therefore implore you to leave this place at once, and not get' yourself into an entanglement with any of the people here. The father, yon .know, is little better than a cattle stealer-"

" But I'm not in love with the father."

" Come ! do not split straws about the matter. Say you will leave to-night ; and I will have the buggy sent, with cushions, and all I can think of to make the drive easy. Say you will come.?"

" I cannot say that," replied Graham, slowly. "Besides, it would be a pity not to allow ' rumour' full swing. No, dear boy, I shall certainly stop here two weeks more-perhaps longer."

Bowring gave vent to an expression of annoyance. " In that case," said he, "I had better be off. Can I send you anything?"

"Nothing but your good wishes, dear boy."

"So long, then : I'll look round in a few days," and shaking hands with the invalid, Jack Bowring cantered away.

Left to himself, Graham smiled sadly.

"So it is even here," he said, "here in this semi-wilderness, as in the lands of the civilized. Scandal floats upon the tropical air of the antipodes, and is wafted twenty miles in as many hours. Poor Polly, poor little girl !"

At this moment the weird form of Jack the Butcher, who by the way fulfilled the duties of groom, nurse to the young children, and general "knock-about hand" to Kelly's establishment, walked on to the verandah, and stood eyeing the invalid with attention. At length he said-"My word, captin, you're malting flesh in no mistake."

" I’m not a captain, neither have I made flesh." Jack the Butcher growled. "Sorry I spoke," said he.

"So am I," rejoined Graham, imperturbably.

A perplexed look came over the man's features, and he scratched his shaggy red head for a few moments, then he said-"You're mighty civil."

" You seemed to make me out military just now." The man stamped his huge foot impatiently.

" Now listen here," said he ; " the sooner you are out of this the better. Dy'e hear me ?"

Graham looked up languidly.

"I hear you," he murmured ; "but I don't understand you."

" Well, then," cried Jack the Butcher ; "strike me blind ! but I'll speak plain. I've known that gal-"

"Whom are you alluding to?-Miss Kelly?"

" Aye, Polly as we calls her, and as you calls her too, cl-n you."

Graham winced, in spite of himself ; but he still preserved his outward appearance of sangfroid, although his hands itched to be at the bony throat of his torturer.

" Now mark me," continued the man, "I've loved that gal for fifteen long years. I've nursed her as a child, and I've watched her growin' up day by day ; and I've said to my-self-"Jack, that gal shall be your wife, when she's old enough."

"That was kind of you. But did you consult the young lady or her parents ?"

" Not I! but I saved her life when the floods was up, and I'm not a'goin' to have a swell like you a comin' in between me and her, I can tell you that ! " And he bent over the sick man, and shook his fist in his face.

Percy Graham looked steadily up into the hideous countenance of his interlocutor, and mentally shuddered as he pictured to himself, in his imagination, the hideous result

that would ensue if the man's dreams were ever realized.

"My good fellow," said Percy, calmly; "were I not prostrated with illness I should certainly thrash you ; as it is, however, I must request you not to approach me until I have regained my strength. If you do so, I shall be forced to complain to your master, since I cannot take the law into my own hands."

A short silence succeeded this speech. Then drawing a long breath, Jack the Butcher said-" So be it, then ; I will wait until you are well again; and then we will see if you are man enough to be as good as your word."

So saying he slouched away in the direction of the paddock.

*****

They were seated upon a fallen tree, that lay before a disused shepherd's hut, about half a mile from the Sirius Downs Hotel. Cheek to cheek and hand in hand, they gazed in to each other's eyes, and drank in long draughts of intoxicating love. Yes, it had come to this. Percy Graham, the blase man of fashion, had succumbed to the fascinations of a simple bush beauty ; he had surrendered his heart to a girl who had but compassed the very rudiments of education, and who had never been fifty miles from her father's house. He did not think of this as he sat by her side, running his fingers through her golden tresses, he did not remember that his father was a peer of England ; and that there flowed through his veins, some of the noblest blood in the three kingdoms. No thought of the derisive scorn with which his " set " would receive the intelligence of his marriage with the daughter of a drunken bush publican troubled his brain at that moment. And why ? He had delivered himself up wholly to the intoxication of the present, and shut out the future resolutely from his mind's eye.

"I must get back now, Percy," she murmured ; " I shall be wanted."

" And are you not wanted by me ?" I " But I must look after the little ones ; they have no mother to tend them, you know."

" Remember, Polly, I am an invalid, and require nursing," said he playfully, "and if you leave me I might be seized with a sudden giddiness, or-or-goodness knows what might happen. Prescribe for me, little doctor."

The prescription was a kiss, of which both physician and patient; partook.

"Before you go, Polly, darling, tell me that you love me," said he.

She nestled her fair head against his breast ; then looking into his eyes, as though she would read his very soul, said in half-broken tones-"Yes, Percy, I love you. if I am wrong in doing so, I hope I may be forgiven. Love you !-ah, the word seems too cold, too prosaic, there is no word for love like mine ; it is an inward burning of the heart, whose flame must be fed by your love alone. Iam yours"; do what you will with me, say but 'come,' and t follow ; lead me whither you list-to the world's end, Ï care not. But Percy, darling, I am not fit to be your wife, I know it. I am poor, illiterate, and have naught but my love to offer you ; yet you would not have the heart'to-'

He caught her in his arms, and pressing his lips to hers, passionately exclaimed, "No, though I had tea thousand fathers I would not give ray darling up. In a month from this, you shall be my wife."

As they stood together for a moment she looked up at him, but did not speak. Her heart was full to bursting. No word, passed her lips, yet silence is sometimes more eloquent than the most impassioned phrases.

And so in the warm glow of the noonday sun, they walked away together.

* * * *

Two weeks had passed quickly by since the above interview, and Percy Graham, no longer having the excuse of illness to prolong his stay at Kelly's, has taken up his quarters at Tulgarra. He rode over to the hotel frequently, however, and on these occasions the lovers had long interviews together. Nor were these the only ones. On Wednesday and Friday evenings, the shepherd's hut was their trysting place, and many were the sweet moments the young couple passed seated in the moonlight, outside that ruined humpy. One morning, as Graham rode up to the hotel, he was surprised to hear that two days before, a strange incident had occurred; Jack the Butcher had disappeared. He had taken nothing with him beyond, (it was surmised) a little bread, 'tea and sugar, and an old gun, usually regarded as worthless. In reply to Percy's questions, Kelly remarked that his henchman's disappearancedid not give him (Kelly) much uneasiness, as Jack had always been "a little touched in the upper story." " He'd come back fast enough," said the landlord " when his flour was done ; until then he was welcome to stay away." In fact Mr. Kelly went so far as to intimate that if Jack the Butcher never returned, he should not expend anything considerable it* mourning, inasmuch as the man had drawn no wages for upwards of seven years, and furthermore had of late "bin; worriting about that gal."

Another two days elasped, and still no signs of the missing man. On the evening of the second day it had been arranged that Percy should ride over at 9 o'clock, and have a five minutes' interview with Polly, who could escape at that hour, on pretence of looking round the premises. It was, however, agreed between them that, should it be wet, Graham was to ride back to the inn, and the love making; was to be accomplished at the paternal residence. At a few moments before the appointed time, therefore, Graham rode, slowly up to the ruined hut, and tying his horse to a tree» sat down to meditate. The sky had been overcast since sun-down, and hardly was he seated than the rain began slowly to descend. Rising to his feet Percy glanced at the hut,, and seeing that a few sheets of bark still adhered to the roof, resolved to enter and seek shelter until the shower should have abated. " Confound the rain!" he muttered, as he swung open the ricketty door ; " there will be no Polly here to night, I'm afraid."

Hardly had he uttered the words than he felt himself: seized from behind, and thrown violently to the ground, hair head striking against a piece of jagged timber, which completely stunned him for a moment. On recovering consciousness he looked up, and beheld the gaunt form of Jack the; Butcher standing over him, with fierce and terrible hatred, written in every line of his countenance. The ruffian was.

armed with a heavy fowling piece, which he pointed straight at the prostrate man's head.

" At last, Mr. Graham," cried Jack the Butcher, " at last we are face to face, where nobody can come between us."