March 13 - 19, 2022: Issue 530

Wreck Of Shackleton's Endurance Found: First Images After Frank Hurley's Last Photos Of This Ship Published

The stern of the Endurance with the name and emblematic polestar. Photo Credit: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and National Geographic

Taffrail and ship's wheel, aft well deck. Photo Credit: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and National Geographic.

The wreck of Endurance was discovered on March 5th 2022 and the announcement of her discovery was made on Wednesday, March 9. She was found 107 years after the ship sank sank (and the 100th anniversary of Shackleton's funeral), by the search team Endurance22 organised by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust. Endurance lies 3,008 metres (9,869 ft) deep, in the Weddell Sea and is in good condition, now located 4 miles (6.4 km) from the location where it was lost.

The team worked from the South African polar research and logistics vessel, S.A. Agulhas II, owned by the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment and under Master, Capt. Knowledge Bengu, using Saab’s Sabertooth hybrid underwater search vehicles. The wreck is protected as a Historic Site and Monument under the Antarctic Treaty, ensuring that whilst the wreck is being surveyed and filmed it will not be touched or disturbed in any way.

Donald Lamont, Chairman of the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust, said:

“Our objectives for Endurance22 were to locate, survey and film the wreck, but also to conduct important scientific research, and to run an exceptional outreach programme. Today’s celebrations are naturally tempered by world events, and everybody involved in Endurance22 keeps those affected by these continuing shocking events in their thoughts and prayers.

“The spotlight falls today on Mensun Bound, the Director of Exploration, and Nico Vincent, Subsea Project Manager. Under the outstanding leadership of Dr John Shears, they have found Endurance. But this success has been the result of impressive cooperation among many people, both on board the remarkable S.A. Agulhas II with its outstanding Master and crew, a skilled and committed expedition team and many on whose support we have depended in the UK, South Africa, Germany, France, the United States and elsewhere. The Trustees extend to them all our warmest thanks and congratulations on this historic achievement.”

Mensun Bound, Director of Exploration on the expedition, said:

“We are overwhelmed by our good fortune in having located and captured images of Endurance. This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen. It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation. You can even see “Endurance” arced across the stern, directly below the taffrail. This is a milestone in polar history. However, it is not all about the past; we are bringing the story of Shackleton and Endurance to new audiences, and to the next generation, who will be entrusted with the essential safeguarding of our polar regions and our planet. We hope our discovery will engage young people and inspire them with the pioneering spirit, courage and fortitude of those who sailed Endurance to Antarctica. We pay tribute to the navigational skills of Captain Frank Worsley, the Captain of the Endurance, whose detailed records were invaluable in our quest to locate the wreck. I would like to thank my colleagues of The Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust for enabling this extraordinary expedition to take place, as well as Saab for their technology, and the whole team of dedicated experts who have been involved in this monumental discovery.”

The Endurance22 expedition brought together world-leading marine archaeologists, engineers, technicians, and sea-ice scientists on S.A. Agulhas II, one of the largest and most modern polar research vessels in the world.

Organised and funded by The Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust (FMHT), its aims were to attempt to locate, survey and film the wreck of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance, which was trapped and crushed by the ice and sank in the Weddell Sea in 1915. This unprecedented 35-day mission had to navigate its way through the heavy sea ice, freezing temperatures and harsh weather of this extreme and forbidding environment, in a quest to be the first to successfully find the Endurance and survey the wreck using state of the art technology.

By uncovering vital new sub-sea data, the expedition hopes to improve our understanding of the Endurance, the sea ice in the Weddell Sea, and to use that knowledge to contribute towards the protection of the wreck. By telling the stories of this expedition and Shackleton’s expedition over one hundred years ago, it hopes to inspire young people about science, engineering, technology and exploration.

Under the leadership of Dr Lasse Rabenstein, Endurance22’s Chief Scientist, a world leading team of scientists from research and educational institutions successfully conducted hundreds of hours of climate change related studies over the duration of the expedition. Representatives from the South African Weather Service, German firm Drift & Noise, Germany’s Alfred-Wegener-Institute, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Aalto University in Finland and South Africa’s Stellenbosch University researched the ice drifts, weather conditions of the Weddell Sea, studies of sea ice thickness, and were able to map the sea ice from space. Combined, these important studies will materially help our understanding of this remote region and how it influences our changing climate.

Since the expedition was conceived, educational outreach was a key objective. The FMHT partnered with Reach the World, the US-based education organisation, and the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) who have successfully connected with tens of thousands of children throughout the expedition via regular live stream interviews and material produced for classroom use.

Endurance was the three-masted barquentine in which Sir Ernest Shackleton and a crew of 27 men and one cat sailed for the Antarctic on the 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. The ship was launched in 1912 from Sandefjord in Norway. Three years later, she was crushed by pack ice and sank in the Weddell Sea off Antarctica. All of the crew survived.

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. After Roald Amundsen's South Pole expedition in 1911, this crossing remained, in Shackleton's words, the "one great main object of Antarctic journeyings". Shackleton's expedition failed to accomplish this objective, but became recognised instead as an epic feat of endurance.

Shackleton had served in the Antarctic on the Discovery expedition of 1901–1904, and had led the Nimrod expedition of 1907–1909. In this new venture he proposed to sail to the Weddell Sea and to land a shore party near Vahsel Bay, in preparation for a transcontinental march via the South Pole to the Ross Sea. A supporting group, the Ross Sea party, would meanwhile establish camp in McMurdo Sound, and from there lay a series of supply depots across the Ross Ice Shelf to the foot of the Beardmore Glacier. These depots would be essential for the transcontinental party's survival, as the group would not be able to carry enough provisions for the entire crossing.

The Ross Sea party and SY Aurora

The expedition required two ships: Endurance under Shackleton for the Weddell Sea party, and Aurora, under Aeneas Mackintosh, for the Ross Sea party. The Ross Sea party was tasked to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the polar route established by earlier Antarctic expeditions. The expedition's main party, under Shackleton, was to land near Vahsel Bay on the Weddell Sea on the opposite coast of Antarctica, and to march across the continent via the South Pole to the Ross Sea. As the main party would be unable to carry sufficient fuel and supplies for the whole distance, their survival depended on the Ross Sea party setting up supply depots, which would cover the final quarter of their journey.

To lead the Ross Sea party Shackleton chose Aeneas Mackintosh, having first attempted to persuade the Admiralty to provide him with a naval crew. Mackintosh, like Shackleton, was a former Merchant Navy officer, who had been on the Nimrod Expedition until his participation was cut short by an accident that resulted in the loss of his right eye. Another Nimrod veteran, Ernest Joyce, whose Antarctic experiences had begun with Captain Robert Falcon Scott's Discovery Expedition, was appointed to take charge of sledging and dogs. Joyce was described by Shackleton's biographer, Roland Huntford, as "a strange mixture of fraud, flamboyance and ability", but his depot-laying work during the Nimrod Expedition had impressed Shackleton.

Shackleton set sail from London on his ship Endurance, bound for the Weddell Sea in August 1914. Meanwhile, the Ross Sea party personnel gathered in Australia, prior to departure for the Ross Sea in the second expedition ship, SY Aurora.

SY Aurora was a 580-ton barque-rigged steam yacht built by Alexander Stephen and Sons Ltd. in Dundee, Scotland, in 1876, for the Dundee Seal and Whale Fishing Company. It was 165 feet (50 m) long with a 30-foot (9.1 m) beam. The hull was made of oak, sheathed with greenheart and lined with fir. The bow was a mass of solid wood reinforced with steel-plate armour. The heavy side frames were braced by two levels of horizontal oak beams. Her primary use was whaling in the northern seas, and she was built sturdily enough to withstand the heavy weather and ice that would be encountered there. In 1910, she was bought by Douglas Mawson's deputy, Captain John King Davis, for £6,000 for his Australasian Antarctic Expedition. She was used for Antarctic exploration between 1911 and 1917 and made five trips to the continent, both for exploration and rescue missions.

The Aurora anchored to floe-ice off the West Base during the Australasian Antarctic Expedition of 1911–1914. Photo by Frank Hurley

Mackintosh and the nucleus of the party arrived in Sydney, late in October 1914. They found that Aurora was in no condition for an Antarctic voyage, and required an extensive overhaul. The registration of the ship in Shackleton's name had not been properly completed, and Shackleton had evidently misunderstood the terms under which he had acquired the vessel from Mawson. Mawson had reclaimed much of the equipment and stores that had been aboard, all of which needed replacing. To compound the problem, Shackleton had reduced the funds available to Mackintosh from £2,000 to £1,000, expecting him to bridge the difference by soliciting for supplies as free gifts and by mortgaging the ship. There was no cash available to cover the wages and living expenses for the party.

ANTARCTICA.

SHACKLETON'S EXPEDITION.

THE AURORA ARRIVES.

The auxiliary barquentine Aurora, which was used by Sir Douglas Mawson to convey his expedition to the Antarctic, and which a to take the Ross Sea division of Sir Ernest Shackleton's expedition to the far south, arrived in Sydney from Hobart yesterday to undergo an overhaul at the Cockatoo Island docks.

The overhaul is expected to take about three weeks at the end of which time the Aurora will, return to Hobart before finally setting out on her journey to the Antarctic early next month Exploration and scientific works will be carried out in Ross Sea, and a basis established for Sir Ernest Shackleton's main party, which is already on its way in the Endurance, to Weddell Sea, and is to cross the Ant at the continent and return home via Ross Sea

The Aurora will winter in the ice, and probably not get back to Hobart till April, MI The scientific staff of the greater part of the Aurora's equipment are coming out on the RMS Ionic, which is expected to arrive at Hobart next Saturday Motor sleighs and 25 dogs are aboard that liner.

The Aurora will be the second vessel to winter in the Antarctic, the Discovery being the first The Belgica was also interested in the Ice, but it was not intended that she should, having merely got there by accident. ANTARCTICA. (1914, November 2). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15555965

Shackleton was now beyond reach, aboard Endurance en route for Antarctica. Supporters of the expedition in Australia, notably Edgeworth David who had served as chief scientist on the Nimrod Expedition, were concerned at the plight in which Mackintosh's party had been placed. They helped to raise sufficient funds to keep the expedition alive, but several members of the party resigned or abandoned the venture. Some of the last-minute replacements were raw recruits; Adrian Donnelly, a locomotive engineer with no sea experience, signed as second engineer, while wireless operator Lionel Hooke was an 18-year-old electrical apprentice. The Aurora set out from Sydney on December 15 1914, bound for Hobart, where she arrived on December 20 to take on final stores and fuel. On December 24, three weeks later than the original target sailing date, the Aurora finally sailed for the Antarctic, arriving off Ross Island on January 16 1915.

When Mackintosh departed to lead the depot-laying parties he left the Aurora under the command of First Officer Joseph Stenhouse. The priority task for Stenhouse was to find a winter anchorage in accordance with Shackleton's instructions not to attempt to anchor south of the Glacier Tongue, an icy protrusion midway between Cape Evans and Hut Point. This search proved a long and hazardous process. Stenhouse manoeuvred in the Sound for several weeks before eventually deciding to winter close to the Cape Evans shore headquarters. After a final visit to Hut Point on March 11 to pick up four early returners from the depot-laying parties, he brought the ship to Cape Evans and made it fast with anchors and hawsers, thereafter allowing it to become frozen into the shore ice.

On the night of May 7, a severe gale erupted, tearing the Aurora from its moorings and carrying it out to sea attached to a large ice floe. Attempts to contact the shore party by wireless failed. Held fast, and with its engines out of commission, the Aurora began a long drift northward away from Cape Evans, out of McMurdo Sound, into the Ross Sea and eventually into the Southern Ocean. Ten men were left stranded ashore at Cape Evans. Aurora finally broke free from the ice on February 12 1916, and managed to reach New Zealand on April 2.

The Endurance

Endurance was the three-masted barquentine in which Sir Ernest Shackleton and a crew of 27 men and one cat sailed for the Antarctic on the 1914–1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. The ship was launched in 1912 from Sandefjord in Norway. Designed by Ole Aanderud Larsen, Endurance was built at the Framnæs shipyard in Sandefjord, Norway. She was built under the supervision of master wood shipbuilder Christian Jacobsen, who was renowned for insisting that all men in his employment were not just skilled shipwrights but also be experienced in seafaring aboard whaling or sealing ships. Every detail of her construction had been scrupulously planned to ensure maximum durability: for example, every joint and fitting was cross-braced for maximum strength.

The ship was launched on December 17 1912 and was initially christened Polaris after the North Star. She was 144 feet (44 m) long, with a 25 feet (7.6 m) beam, and measured 348 tons gross. Her original purpose was to provide luxurious accommodation for small tourist and hunting parties in the Arctic as an ice-capable steam yacht. As launched she had 10 passenger cabins, a spacious dining saloon and galley (with accommodation for two cooks), a smoking room, a darkroom to allow passengers to develop photographs, electric lighting and even a small bathroom.

Though her hull looked from the outside like that of any other vessel of a comparable size, it was not. She was designed for polar conditions with a very sturdy construction. Her keel members were four pieces of solid oak, one above the other, adding up to a thickness of 85 inches (2,200 mm), while its sides were between 30 inches (760 mm) and 18 inches (460 mm) thick, with twice as many frames as normal and the frames being of double thickness. She was built of planks of oak and Norwegian fir up to 30 inches (760 mm) thick, sheathed in greenheart, an exceptionally strong and heavy wood. The bow, which would meet the ice head-on, had been given special attention. Each timber had been made from a single oak tree chosen for its shape so that its natural shape followed the curve of the ship's design. When put together, these pieces had a thickness of 52 inches (1,300 mm).

Of her three masts, the forward one was square-rigged, while the after two carried fore and aft sails, like a schooner. As well as sails, Endurance had a 350 horsepower (260 kW) coal-fired steam engine capable of speeds up to 10.2 knots (18.9 km/h; 11.7 mph).

At the time of her launch in 1912, Endurance was arguably the strongest wooden ship ever built, with the possible exception of Fram, the vessel used by Fridtjof Nansen and later by Roald Amundsen. There was one major difference between the ships. Fram was bowl-bottomed, which meant that if the ice closed in against her, the ship would be squeezed up and out and not be subject to the pressure of the ice compressing around her. Endurance, on the other hand, was designed with great inherent strength in her hull in order to resist collision with ice floes and to break through pack ice by ramming and crushing; she was therefore not intended to be frozen into heavy pack ice, and so was not designed to rise out of a crush. In such a situation, she was dependent on the ultimate strength of her hull alone.

Financial problems led to Gerlache pulling out of their partnership, leaving Christensen unable to pay the Framnæs yard the final amounts to hand over and outfit the ship. For over a year Christensen attempted unsuccessfully to sell the ship, since her unique design as an ice-capable passenger-carrying ship, with relatively little space for stores and no cargo hold, made her useless to the whaling industry. As she was too big, slow and uncomfortable to be a private steam yacht, Christensen was happy to sell the ship to Ernest Shackleton for GB£11,600, which represented a significant loss to Christensen as it barely covered the outstanding payments to Framnæs, let alone the ship's total build costs. He is reported to have said he was happy to take the loss in order to further the plans of an explorer of Shackleton's stature. After Shackleton purchased the ship, she was rechristened Endurance after the Shackleton family motto, Fortitudine vincimus ("By endurance we conquer").

Shackleton had the ship relocated from Norway to London. She arrived at the Millwall Dock in the spring of 1914, where she was refitted and modified for expedition purposes. She was stripped of most of her luxurious accommodation and fittings. This included removing many of the passenger cabins to make room for space for stores and equipment, while the crew cabins on the lower deck were removed and converted into a cargo hold—the reduced crew of sailors that Shackleton would take on the expedition would make their quarters in the cramped forecastle. The darkroom remained in its original location ahead of the boiler. The refit also saw the ship repainted from her original white colour to a more austere black, which was more visible amongst the ice, and features such as gilt scrollwork on the bow and stern were painted over. Despite her change of name, she retained a large badge in the shape of a five-pointed star on her stern, which originally symbolised her name after the pole star.

Her new equipment included four ship's boats. Two were 21-foot (6.4 m) transom-built rowing cutters purchased secondhand from the whaling industry. The third was a larger 22.5-foot (6.9 m) double-ended rowing whaleboat built for the expedition to specifications drawn up by Frank Worsley, Endurance's new captain. The fourth was a smaller motorboat. After her refit, Endurance made the short coastal journey to Plymouth.

Endurance sailed from Plymouth on August 6 1914 and set course for Buenos Aires, Argentina, under Worsley's command. Shackleton remained in Britain, finalising the expedition's organization and attending to some last-minute fundraising. This was Endurance's first major voyage following its completion and amounted to a shakedown voyage. The trip across the Atlantic took more than two months. Built for the ice, her hull was considered by many of her crew too rounded for the open ocean. Shackleton took a steamer to Buenos Aires and caught up with his expedition a few days after Endurance's arrival.

On October 26 1914, Endurance sailed from Buenos Aires to what would be her last port of call, the whaling station at Grytviken on the island of South Georgia, where she arrived on November 5. She left Grytviken on December 5 1914, heading for the southern regions of the Weddell Sea.

Two days after leaving South Georgia, Endurance encountered polar pack ice and progress slowed to a crawl. For weeks Endurance worked its way through the pack, averaging less than 30 miles (48 km) per day. By January 15 1915, Endurance was within 200 miles (320 km) of her destination, Vahsel Bay. By the following morning, heavy pack ice was sighted and in the afternoon a gale developed. Under these conditions it was soon evident progress could not be made, and Endurance took shelter under the lee of a large grounded iceberg. During the next two days, Endurance moved back and forth under the sheltering protection of the berg.

On January 18, the gale began to moderate and Endurance set the topsail with the engine at slow. The pack had blown away. Progress was made slowly until hours later Endurance encountered the pack once more. It was decided to move forward and work through the pack, and at 5:00 pm Endurance entered it. This ice was different from what had been encountered before, and the ship was soon amongst thick but soft brash ice, and became beset. The gale increased in intensity and kept blowing for another six days from a northerly direction towards land. By January 24 the wind had completely compressed the ice in the Weddell Sea against the land, leaving Endurance icebound as far as the eye could see in every direction. All that could be done was to wait for a southerly gale to start pushing in the other direction, which would decompress and open the ice.

In the early morning of January 24, a wide crack appeared in the ice 50 yards (46 m) ahead of the ship. Initially 15 feet (4.6 m) across, by mid-morning the break was over a quarter of a mile (0.4 km) wide, giving the men on the Endurance hope that the ice was breaking up. But the break never reached the ship itself, and despite three hours under full sail and full speed on the engine, the ship did not budge. Over the next days, the crew waited for the southerly gale to release the pressure on the ice, but while the wind backed to the hoped-for south/southwest direction, it remained light and erratic. Occasional breaks in the ice were spotted, but none reached the ship and all closed up within a few hours. Trials were made on January 27 with cutting and breaking the ice around the ship by manual labour, but this proved futile.

On February 14, an open channel of water opened up a quarter of a mile (0.4 km) ahead of the ship and dawn showed the Endurance was afloat in a pool of soft, young ice no more than 2 feet (0.61 m) thick, but the pool was surrounded by solid pack ice of 12–18 feet (3.7–5.5 m) in thickness, blocking the path to the open lead. A day's continual work by the crew saw them hack a clear channel 150 yards (140 m) long. This work continued through the following day, February 15, and, with steam raised, the Endurance was backed up within her pool as far as possible to allow the ship to ram her way through the channel. As the ship went astern for successive attempts, lines were attached from the bow to loosened blocks of ice, estimated to weigh 20 tons (18 tonnes), in order to clear the path. The pool proved too small for the ship to gain enough momentum to successfully ram her way clear and by the end of the day the ice began to freeze up again. By 3:00 pm, the Endurance had made 200 yards (180 m) of distance through the ice, with 400 yards (370 m) still to go to clear water. Shackleton decided that the consumption of coal and manpower, and the risk of damage to the ship, was too great and called a halt.

The Endurance's boilers were extinguished, committing the ship to drift with the ice until released naturally. On February 17, the sun dipped below the horizon at midnight, showing the end of the Antarctic summer. On 24 February, regular watches on the ship were cancelled, with the Endurance now functioning as a shore station. The ship had slowly drifted south and at this point was within 60 miles (97 km) of the intended landing point at Vahsel Bay. But the icy terrain between the ship and the shore was too arduous to travel while carrying the materials and supplies needed for the overland expedition.

By March, navigational observation showed that the ship (and the mass of pack ice that contained it) was still moving, but now swinging towards the west-northwest and increasing in the speed of its drift, moving 130 miles (210 km) between the start of March and May 2, when the sun disappeared below the horizon and the dark Antarctic winter began. Still, the men on the ship hoped for either a change in the weather which would break up the pack or that, by the spring, the warmer weather and the ship's northward drift would mean it was released.

On July 1915 14, Endurance was swept by a southwest gale, with wind speeds of 112 km/h (31 m/s; 70 mph), a barometer reading of 28.88 inches of mercury (978 hPa) and temperatures falling to −33 °F (−36 °C). The blizzard continued until July 16. This broke up the pack ice into smaller, individual floes, each of which began to move semi-independently under the force of the weather, while also clearing water in the north of the Weddell Sea. This provided a long fetch for the south-setting wind to blow over and then for the broken ice to pile up against itself while individual parts moved in different directions. This caused regions of intense localised pressure in the ice field. The ice began "working", with sounds of breaking and colliding ice audible to those on the ship through the next day. Breaks in the ice were spotted but none approached the ice holding the Endurance.

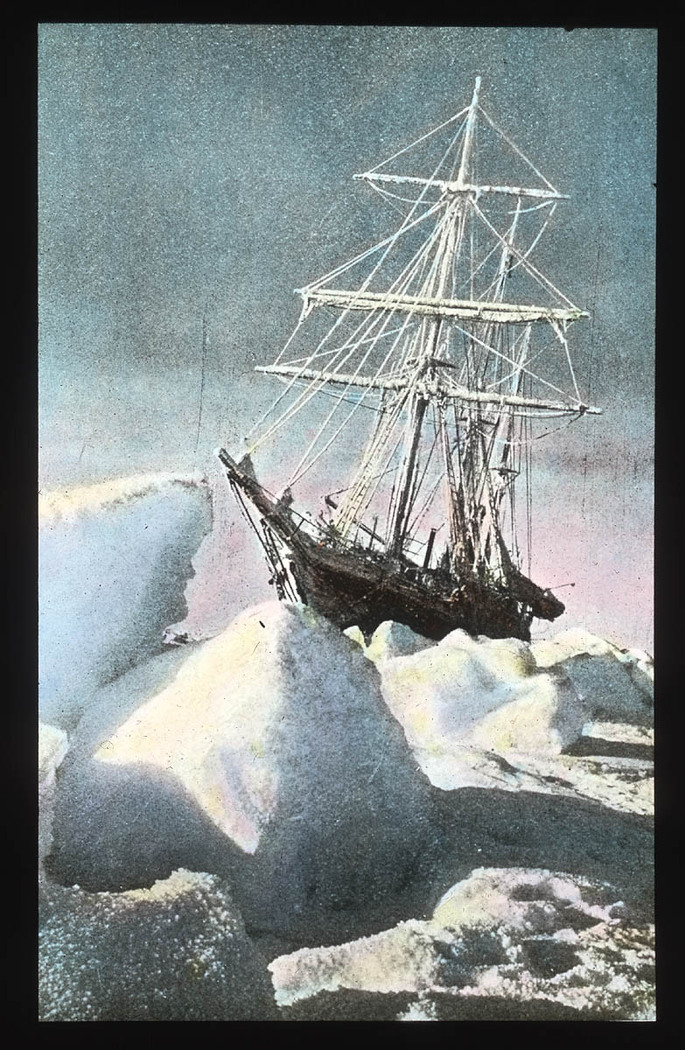

Endurance under sail trying to break through pack ice, Weddell Sea, Antarctica, 1915, by Frank Hurley, from original Paget Plate, Photo by Frank Hurley, courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

During July the ship drifted a further 160 miles (260 km) to the north. On the morning of August 1, a pressure wave passed through the floe holding the ship, lifting the 400-ton Endurance bodily upwards and heeling the ship sharply to its port side before it dropped into a pool of water, afloat again for the first time in nearly six months. The broken sections of floe closed in around the ship on all sides, jarring the Endurance forward, backwards and sideways in violent fashion against the other slabs of ice. After over a quarter of an hour, a force from astern pushed the ship's bow up onto the floe, lifting the hull out of the pressure and with a list of five degrees to her port side. A gale overnight further disturbed the floe, driving it against the starboard side of the hull and forcing a sheet of ice upwards at a 45-degree angle until it reached the level of the scuppers. Despite the ordeal of the past few days, the ship remained undamaged.

Two pressure waves struck the ship on August 29 without incident. On the evening of August 31, a slow-building pressure gripped the Endurance, causing her hull and timbers to creak and shudder continuously. The ice around the ship moved and broke throughout the night, battering the port side of the hull. All was quiet again until the afternoon of September 30, by which time there were signs of spring with ten hours of sunlight per day and occasional temperature readings above freezing. A large floe was swept against the Endurance's port bow and then gripped that side of the ship against the built-up ice and snow on her starboard beam. The ship's structure groaned and wracked under the strain. Carpenter Harry McNish noted that the solid oak beams supporting the upper deck were being visibly bent "like a piece of cane". On deck the ship's masts were whipping back and forth as their stepping points on the keel were distorted. Despite these disconcerting signs, Captain Frank Worsley noted that the strength of the ship's structure was causing the ice itself to break up as it piled against the hull—"just as it appears she can stand no more, the huge floe weighing possibly a million tons or more yields to our little ship by cracking across ... and so relieves the pressure. The behaviour of our ship in the ice has been magnificent. Undoubtedly she is the finest little wooden vessel ever built". Despite this, the ship's decks were permanently buckled.

By October, temperatures of nearly 42 °F (6 °C) were recorded and the ice showed further signs of opening up. The floe which had been jammed against the ship's starboard side since July broke up on October 14, casting the Endurance afloat in a pool of open water for the first time in nine months.

On October 16, Shackleton ordered steam to be raised so the ship could take advantage of any openings in the ice. It took nearly four hours for the boilers to be filled with freshwater melted from ice, and then a leak was discovered in one of the fittings and they had to be pumped out, repaired and then refilled. The following day a lead of open water was seen ahead of the ship. Only one boiler had been lit and there was insufficient steam to use the engine, so all the sails were set to try to force the ship into the loosening pack ice, but without success.

In the late afternoon of October 18, the ice closed in around the Endurance once again. In just five seconds the ship was canted over to port by 20 degrees, and the list continued until she rested at 30 degrees, with the port bulwark resting on the pack and the boats on that side nearly touching the ice as they hung in their davits. This put the ship in a seemingly safe position—instead of being pinched between two opposing masses of ice the Endurance had been pushed from starboard to port and further pressure from starboard would push her bodily upwards over the top of the port-side floe, which had actually collided with its counterpart under the ship's bilge. In any case, after four hours in this position, the ice drew apart and the ship returned to a level keel.

The ice was relatively still for the rest of the month. On October 20, steam was raised again and the engines tested. On October 22, the temperature dropped sharply from 42 °F (6 °C) to −14 °F (−26 °C) and the wind veered from southwest to northeast. This caused the loosening pack to compress against the Antarctic coast once again. On October 23, pressure ridges could be seen forming in the ice and moving near the ship. The next day a series of pressure waves struck the Endurance, causing the ice around the ship to fracture into separate large pieces which were then tumbled and turned in all directions. The ship was shunted back and forth before being pinched against two floes on her starboard side, one at her bow and one at her stern, while on the port side a floe impacted amidships, setting up a huge bending force on the hull. Parts of the rigging were snapped under the strain.

A large mass of ice slammed into the stern, tearing the sternpost away from the hull planking. Around the same time, the bow planking was stove in, causing simultaneous flooding in the engine room and the forward hold. Despite using both the portable manual pumps and getting up steam to drive the main bilge pumps, the water level continued to rise. The main man-powered deck pumps did not work as their intakes had frozen and could only be restored by pouring buckets of boiling water onto the pump pipes from inside the coal bunkers and then playing a blowtorch over the intake valve. McNish constructed a cofferdam in the shaft tunnel to seal off the damaged stern area while the crew were arranged in spells of 15 minutes on, 15 minutes off on the main pump. After 28 hours of continuous work, the inflow of water had only been arrested—the ship was still badly flooded though.

On October 24, the damaged ship was wracked by further pressure waves. The port-side floe was pressed more heavily against the side, warping the keel along its length and causing near-continual creaks, groans, cracks and "screams" from the ship's timbers. The footplates in the engine room were pushed up and would no longer sit in place as the compartment was compressed. The planking of the ship's port side was bowing inwards by up to 6 inches (15 cm). At 10:00 pm, Shackleton ordered the ship's boats, stores and essential equipment to be moved onto the surrounding ice.

In the afternoon of October 25, the pressure of the ice increased further. The main deck of the Endurance buckled upwards amidships and the beams sheared. As the ice moved against her stern, the aft part of the ship was lifted up and the damaged sternpost and the rudder were torn away. This angle caused all the water in the ship to run forward, collecting in the bow where it then began to freeze. The action of the ice in the stern and the excessive weight in the bow caused the ship to sink into the ice bow-first. Under its own pressure, the ice then broke over the forecastle and piled up onto the deck in the forward part of the ship, further weighing this end of the ship down. Through all of this, the pumping operations had continued, but by the end of the day Shackleton ordered this to stop and for the men to take to the ice.

During the course of the next day, parties were sent back to the ship to recover more supplies and stores. They found that the entire port side of the Endurance had been driven inwards and compressed, and the ice had entirely filled the bow and stern sections. The ship's Blue Ensign was hoisted up her mizzen mast so that she would, in Shackleton's word's, "go down with colours flying."

After a failed attempt to man-haul the boats and stores overland on sledges, Shackleton realised the effort was much too intense and that the party would have to camp on the ice until it carried them to the north and broke up. More parties were sent back to the Endurance, still with her masts and rigging intact and all but her bow above the ice, to salvage any remaining items. A large portion of provisions had been left on the submerged lower deck. The only way to retrieve them was to cut through the main deck, which was more than a foot thick in places and itself under three feet of water. Some crates and boxes floated up once a hole had been cut, while others were retrieved with a grapple. In total, nearly 3.5 tons of stores were recovered from the wrecked ship.

The party was still camped under 2 miles (3.2 km) from the remains of the Endurance on November 8 when Shackleton returned to the ship to consider further salvage. By now the ship had sunk a further 18 inches (46 cm) into the ice and the upper deck was now almost level with the ice. The interior of the ship was almost full of compacted ice and snow, making further work impossible. The damage to the bow and stern, and the force of the ice against the port side, had caused a large portion of the hull on that side of the ship to break free of the rest of the ship and, under the force of the ice, be moved bodily inwards in a telescoping effect. In some places, the outer hull planks were now in line with the keel. A stash of empty fuel oil cans placed against the port side wall of the deckhouse had been pushed through the wall and then the cans and the wall had come to rest against its counterpart on the starboard side of the deckhouse. The row of five cabins that had been on the port side of the main deck above the engine room and their contents had been compressed into the space of a single cabin.

On November 13, a new pressure wave swept through the pack ice. The forward topgallant mast and topmasts collapsed as the bow was finally crushed. These moments were recorded on film by expedition photographer Frank Hurley. The mainmast was split near its base and shortly afterwards the mainmast and the mizzen mast broke and collapsed together, with this also filmed by Hurley. The ensign was re-rigged on the tip of one of the foremast yardarms which, constrained by the rigging, was now hanging vertically from the remains of the foremast and was the highest point of the wreck.

Endurance sinks trapped in the ice of the Weddell Sea in November 1915. Photos by Frank Hurley, courtesy of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, item a423110h.

In the late afternoon of November 21, movement of the remaining wreckage was noticed as another pressure wave hit. Within the space of a minute, the stern of the Endurance was lifted clear of the ice as the floes moved together and then, as the pressure passed and they moved apart, the entire wreck fell into the ocean. By daylight the following day, the ice surrounding the spot where the Endurance had sunk had moved together again, obliterating any trace of the wreck. Worsley fixed the position as 68° 38.5'S 52° 58'W.

The end of Endurance - filmed by Frank Hurley

For almost two months, Shackleton and his party camped on a large, flat floe, hoping that it would drift towards Paulet Island, approximately 250 miles (402 km) away, where it was known that stores were cached. After failed attempts to march across the ice to this island, Shackleton decided to set up another more permanent camp (Patience Camp) on another floe, and trust to the drift of the ice to take them towards a safe landing.

At home, no one knew what was going on to either Shackleton's party or those sent as the Ross Sea Party:

Shackleton.

Captain Davis, who navigated the Aurora for Sir Douglas Mawson on his scientific mission to Antarctic, recently declared that there was no reason for alarm because Australia has not heard by wireless of the safety of the party which went down in connection with Shackleton's present expedition to Ross Sea. Considerable light is thrown on the reason of this silence by Mr. A. C. Tulloch, of the Government Meteorological Staff, who went in November, 1914, to take charge of the wireless station at Macquarie Island, Mr. Tulloch, by the way, went to the island in the Endeavour, and it was on her way back that the trawler was lost, with all hands. The reason that those on the Aurora have not communicated with the Island is because the wireless plant is not capable of sending across the distance. The engine was put in in Sydney, and it was said to have had a range of 2,000 miles, but on its way to the island it was found that the dynamo had worked loose on its bearings, but this, not only reduced the range, but the time for which the machine could be operated. Added to this, the aerials were supplied by the masts of the Aurora, and these declares Mr. Tulloch, were certainly not high enough to send for 2,000 miles, except under freak conditions. The wireless mast at Macquarie Island, which has a 2,000-mile range, is a 100 feet high; and stands on a ridge 300 feet above sea-level. The height of aerial makes all the difference in sending. Besides these two reasons for failures, the anchorage in Ross Sea will be behind the lofty range of hills in Victoria Land. These hills are over 1,500 feet in height, and would interfere considerably with the radius of transmission. These things considered, Mr. Tulloch thinks that it would be nothing short of a miracle is the Aurora's wireless engine could transmit a message for the 1500 miles from the Ross Sea to the Island, or the greater distance to the Bluff. Shackleton. (1916, January 7). Cootamundra Herald (NSW : 1877 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article139526320

By March 17, their ice camp was within 60 miles (97 km) of Paulet Island; however, separated by impassable ice, they were unable to reach it. On April 9, their ice floe broke into two, and Shackleton ordered the crew into the lifeboats and to head for the nearest land.

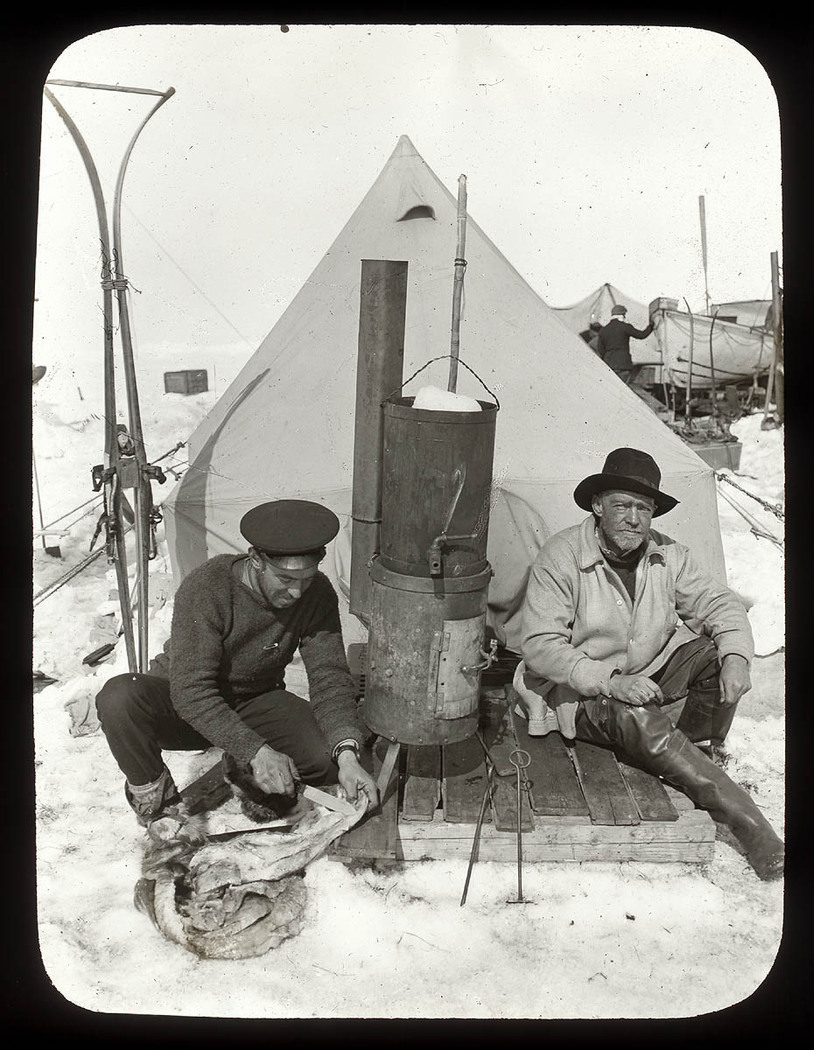

After five harrowing days at sea, the exhausted men landed their three lifeboats at Elephant Island, 346 miles (557 km) from where the Endurance sank. This was the first time they had stood on solid ground for 497 days. Shackleton's concern for his men was such that he gave his mittens to photographer Frank Hurley, who had lost his during the boat journey. Shackleton suffered frostbitten fingers as a result.

Elephant Island was an inhospitable place, far from any shipping routes; rescue by means of chance discovery was very unlikely. Consequently, Shackleton decided to risk an open-boat journey to the 720-nautical-mile-distant South Georgia whaling stations, where he knew help was available. The strongest of the tiny 20-foot (6.1 m) lifeboats, christened James Caird after the expedition's chief sponsor, was chosen for the trip. Ship's carpenter Harry McNish made various improvements, including raising the sides, strengthening the keel, building a makeshift deck of wood and canvas, and sealing the work with oil paint and seal blood.

Shackleton chose five companions for the journey: Frank Worsley, Endurance's captain, who would be responsible for navigation; Tom Crean, who had "begged to go"; two strong sailors in John Vincent and Timothy McCarthy, and finally the carpenter McNish. Shackleton had clashed with McNish during the time when the party was stranded on the ice, but, while he did not forgive the carpenter's earlier insubordination, Shackleton recognised his value for this particular job. Not only did Shackleton recognize their value for the job but also because he knew the potential risk they were to morale. This allowed for Shackleton to remain in control of the morale of his crew members. The attitudes of his men were a point of emphasis in leading his men back to safety.

Shackleton refused to pack supplies for more than four weeks, knowing that if they did not reach South Georgia within that time, the boat and its crew would be lost. The James Caird was launched on April 24 1916. During the next fifteen days, it sailed through the waters of the southern ocean, at the mercy of the stormy seas, in constant peril of capsizing. On May 8, thanks to Worsley's navigational skills, the cliffs of South Georgia came into sight, but hurricane-force winds prevented the possibility of landing. The party was forced to ride out the storm offshore, in constant danger of being dashed against the rocks. They later learned that the same hurricane had sunk a 500-ton steamer bound for South Georgia from Buenos Aires.

On the following day, they were able, finally, to land on the unoccupied southern shore. After a period of rest and recuperation, rather than risk putting to sea again to reach the whaling stations on the northern coast, Shackleton decided to attempt a land crossing of the island. Although it is likely that Norwegian whalers had previously crossed at other points on ski, no one had attempted this particular route before. For their journey, the survivors were only equipped with boots they had pushed screws into to act as climbing boots, a carpenter's adze, and 50 feet of rope. Leaving McNish, Vincent and McCarthy at the landing point on South Georgia, Shackleton travelled 32 miles (51 km) with Worsley and Crean over extremely dangerous mountainous terrain for 36 hours to reach the whaling station at Stromness on May 20.

Shackleton.

At last a message has come from Shackleton that he is safe at Falk-land Islands off the South Coast of South America. He sent the following message:

'I have arrived here (Falkland Islands). The Endurance was crushed in the ice in the middle of Weddel Sea on October 7, 1915, and drifted 700 miles in the ice until April 9, 1916.

"We landed on Elephant Island on April 16.

"I left on the 24th, leaving 22 men in a hole in the ice-cliffs, and proceeded to South Georgia, with five men in a 22ft boat.

"At the time of leaving the island all were well, but they are in urgent need of rescue."

It will be remembered that Shackleton was going to cross the Antarctic from the American side and come out on the Australian side. The Aurora was to meet him and bring him to New Zealand. However he did not cross as the difficulties began in the Weddel Sea, on the American side of the Antarctic continent. The Endurance left South Georgia on December 6, 1914, and was caught in the ice in Weddel Sea about February. After a long drift of nearly 600 miles, full of eventful happenings (one of which being the crushing of the ship by the ice on Nov. 20), the party made for Elephant Island, which is 600 miles south east of Cape Horn. From there a volunteer party set out for South Georgia for assistance. The whole party was nearly done, some on the verge of physical and mental collapse. The trip to South Georgia was full of serious crisis. The party landed, weak and frost bitten. Two were unfit to march. The other three, including Shackleton, marched across the island to the whaling station after a three days tramp. It was the first time the island had been crossed. Assistance was obtained and the two men left behind were rescued and a whaling boat set out for those on Elephant Island. So far, owing to the ice and shortage of coal they have not been rescued. Shackleton. (1916, June 6). Dungog Chronicle : Durham and Gloucester Advertiser (NSW : 1894 - 1954), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article136015362

The next successful crossing of South Georgia was in October 1955, by the British explorer Duncan Carse, who travelled much of the same route as Shackleton's party. In tribute to their achievement, he wrote: "I do not know how they did it, except that they had to—three men of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration with 50 feet of rope between them—and a carpenter's adze".

Shackleton immediately sent a boat to pick up the three men from the other side of South Georgia while he set to work to organise the rescue of the Elephant Island men. His first three attempts were foiled by sea ice, which blocked the approaches to the island. He appealed to the Chilean government, which offered the use of the Yelcho, a small seagoing tug from its navy. Yelcho, commanded by Captain Luis Pardo, and the British whaler Southern Sky reached Elephant Island on 30 August 1916, at which point the men had been isolated there for four and a half months, and Shackleton quickly evacuated all 22 men. The Yelcho took the crew first to Punta Arenas and after some days to Valparaiso in Chile where crowds warmly welcomed them back to civilisation.

There remained the men of the Ross Sea Party, who were stranded at Cape Evans in McMurdo Sound, after Aurora had been blown from its anchorage and driven out to sea, unable to return. The ship, after a drift of many months, had returned to New Zealand. Shackleton travelled there to join Aurora, and sailed with her to the rescue of the Ross Sea party. This group, despite many hardships, had carried out its depot-laying mission to the full, but three lives had been lost, including that of its commander, Aeneas Mackintosh.

The Aurora survived for less than a year after her final return from the Ross Sea. Shackleton had sold her for £10,000, and her new role was as a coal-carrier between Australia and South America. After leaving Newcastle on June 20 1917, Aurora disappeared in the Pacific Ocean. On January 2 1918, she was listed as missing by Lloyd's of London and presumed lost, having either foundered in a storm or been sunk by an enemy raider. Aboard her was James Paton of the Ross Sea ship's party, who was still serving as her boatswain.

THE AURORA.

Many people visited the Shackleton Antarctic exploration vessel lying at Stockton wharf yesterday, the silver coin collection being in aid of the funds of the Newcastle branch of the Red Cross Society. The Newcastle Ferries Company announces a service for to-day for those visiting the vessel. THE AURORA. (1917, April 13). Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (NSW : 1876 - 1954), p. 6. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article133759846

In 1927, a Mr. G. Bressington was walking along the beach near Tuggerah and noticed an old wine bottle partly buried in the sand. Upon examining the bottle he saw an engraving of the picture of a ship and on the other side the following message: "Midwinter's Day, 1912, Shackleton Glacier, Antarctica. 'Frank Wild, A. L. Kennedy, S. Evan Jones, C. Arch. Hoadley, Charles T. Harrisson, George Dovers, A. L. Watson and Morton H. Moyes".

RELIC OF AURORA EXPEDITION.

Found at Tuggerah.

Mr. W. Barnett, Tumbi, forwards the following notes of a find on Tuggerah Beach, which connects our district with a famous southern expedition: — A remarkable story of the sea is unfolded by the recent finding on the beach at Tuggerah, by Mr. G. Bressington, of a wine bottle which had been cast up by the sea. When discovered, the bottle was half buried in the wet sand. On it was engraved: —

'Midwinter's Day, 1912. Shackleton Glacier, Antarctica. Frank Wild, A. L.. Kennedy, S. Evan Jones, C. Arch. Hoadley, Chas. T. Harrison, Geo. Do vers, A.'L. Watson and Merton H. Moyes. ' '

Sir Douglas Mawson's Aurora left England in 1911 to explore Adelie Land; the expedition was presented by Mr. J. Y. Buchanan with three bottles of Madeira, which came from the stock of wine carried in H.M.S. Challenger, survey ship, when that vessel made her famous cruise round the world in the seventies. In the course of the voyage she anchored off Sandridge, now Port Melbourne. These three bottles were given, to Mawson's expedition, with the idea that the wine should be drunk at the explorers' great festival, Midwinter's Day, wherever they might happen to be.

One of the bottles was given by Mawson to Frank Wild, the leader of a second party which pushed along the coast past Adelie Land in the Aurora, which was commanded by Captain J. K. Davis, now Director of Navigation. In accordance with the wishes of the donor, the wine was duly drunk at a farewell party in the Aurora, before she left them. Harrison, the artist of the party, engraved one side of the bottle with a picture of the Aurora and the names of the party on the other side. Wild then took possession of the bottle to return it to the donor, and that was the last known of the bottle until it was found by Mr. Bressington recently on the beach at Tuggerah, 16 years afterwards. The Aurora herself, after many years buffeting as an exploring ship, was sold during the war and fitted up as a tramp steamer. RELIC OF AURORA EXPEDITION. (1927, July 14). The Gosford Times and Wyong District Advocate (NSW : 1906 - 1954), p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161286489

The story of the bottle is that it was one of three given to Sir Douglas Mawson when his expedition left England in 1911. The bottles were given by Mr J. T. Buchanan who had them left over from the Challenger expedition and wished the party to drink them on Explorer Day. Mawson passed one bottle on to Frank Wild, who led the Western Base Party whilst Aurora was under the command of John King Davis. When the wine was drunk on the day, the party's artist Harrisson engraved a picture of Aurora on one side and the names of the party on the other. It is thought the bottle was still aboard Aurora when it left Newcastle in 1917.

Shackleton returned to England in May 1917 when Britain was fighting WWI. He volunteered for the army, requesting to be sent to the front in France but was sent to Buenos Aires to boost British propaganda in South America. He was unsuccessful in persuading Argentina and Chile to enter the war on the Allied side and returned home in April 1918.

From October 1918, he served with the North Russia Expeditionary Force in the Russian Civil War under the command of Major-General Edmund Ironside, with the role of advising on the equipment and training of British forces in arctic conditions. He returned to England in early March 1919, full of plans for the economic development of Northern Russia. In the midst of seeking capital, his plans foundered when Northern Russia fell to Bolshevik control. He was finally discharged from the army in October 1919, retaining his rank of major.

Shackleton returned to the lecture circuit and published his own account of the Endurance expedition, South, in December 1919. In 1920, tired of the lecture circuit, Shackleton began to consider the possibility of a last expedition. He thought seriously of going to the Beaufort Sea area of the Arctic, a largely unexplored region, and raised some interest in this idea from the Canadian government. With funds supplied by former schoolfriend John Quiller Rowett, he acquired a 125-ton Norwegian sealer, named Foca I, which he renamed Quest.

The plan changed; the destination became the Antarctic, and the project was defined by Shackleton as an "oceanographic and sub-antarctic expedition". The goals of the venture were imprecise, but a circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent and investigation of some "lost" sub-Antarctic islands, such as Tuanaki, were mentioned as objectives. Rowett agreed to finance the entire expedition, which became known as the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition. On September 16 1921, Shackleton recorded a farewell address on a sound-on-film system created by Harry Grindell Matthews, who claimed it was the first "talking picture" ever made. The expedition left England on September 24 1921.

Although some of his former crew members had not received all their pay from the Endurance expedition, many of them signed on with their former "Boss". When the party arrived in Rio de Janeiro, Shackleton suffered a suspected heart attack. He refused a proper medical examination, so Quest continued south, and on 4 January 1922, arrived at South Georgia.

In the early hours of the next morning, Shackleton summoned the expedition's physician, Alexander Macklin, to his cabin, complaining of back pains and other discomfort. According to Macklin's own account, Macklin told him he had been overdoing things and should try to "lead a more regular life", to which Shackleton answered: "You are always wanting me to give up things, what is it I ought to give up?" "Chiefly alcohol, Boss," replied Macklin. A few moments later, at 2:50 a.m. on January 5 1922, Shackleton suffered a fatal heart attack.

Macklin, who conducted the postmortem, concluded that the cause of death was atheroma of the coronary arteries exacerbated by "overstrain during a period of debility". Leonard Hussey, a veteran of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic expedition, offered to accompany the body back to Britain; while he was in Montevideo en route to England, a message was received from his wife Emily Shackleton asking that her husband be buried in South Georgia. Hussey returned to South Georgia with the body on the steamer Woodville, and on March 5 1922, Shackleton was buried in the Grytviken cemetery, South Georgia, after a short service in the Lutheran church, with Edward Binnie officiating. Macklin wrote in his diary: "I think this is as 'the Boss' would have had it himself, standing lonely in an island far from civilisation, surrounded by stormy tempestuous seas, & in the vicinity of one of his greatest exploits."

Study of diaries kept by Eric Marshall, medical officer to the 1907–09 expedition, suggests that Shackleton suffered from an atrial septal defect ("hole in the heart"), a congenital heart defect, which may have been a cause of his health problems.

Shackleton's grave at Grytviken. Photo: Lexaxis7

The S.A. Agulhas II left the site on Tuesday and plans to call in at the abandoned whaling station at Grytviken in South Georgia to visit Shackleton’s grave and pay tribute to “The Boss” before heading back to South Africa. You can read the full story in the May-June 2022 edition of Australian Geographic.

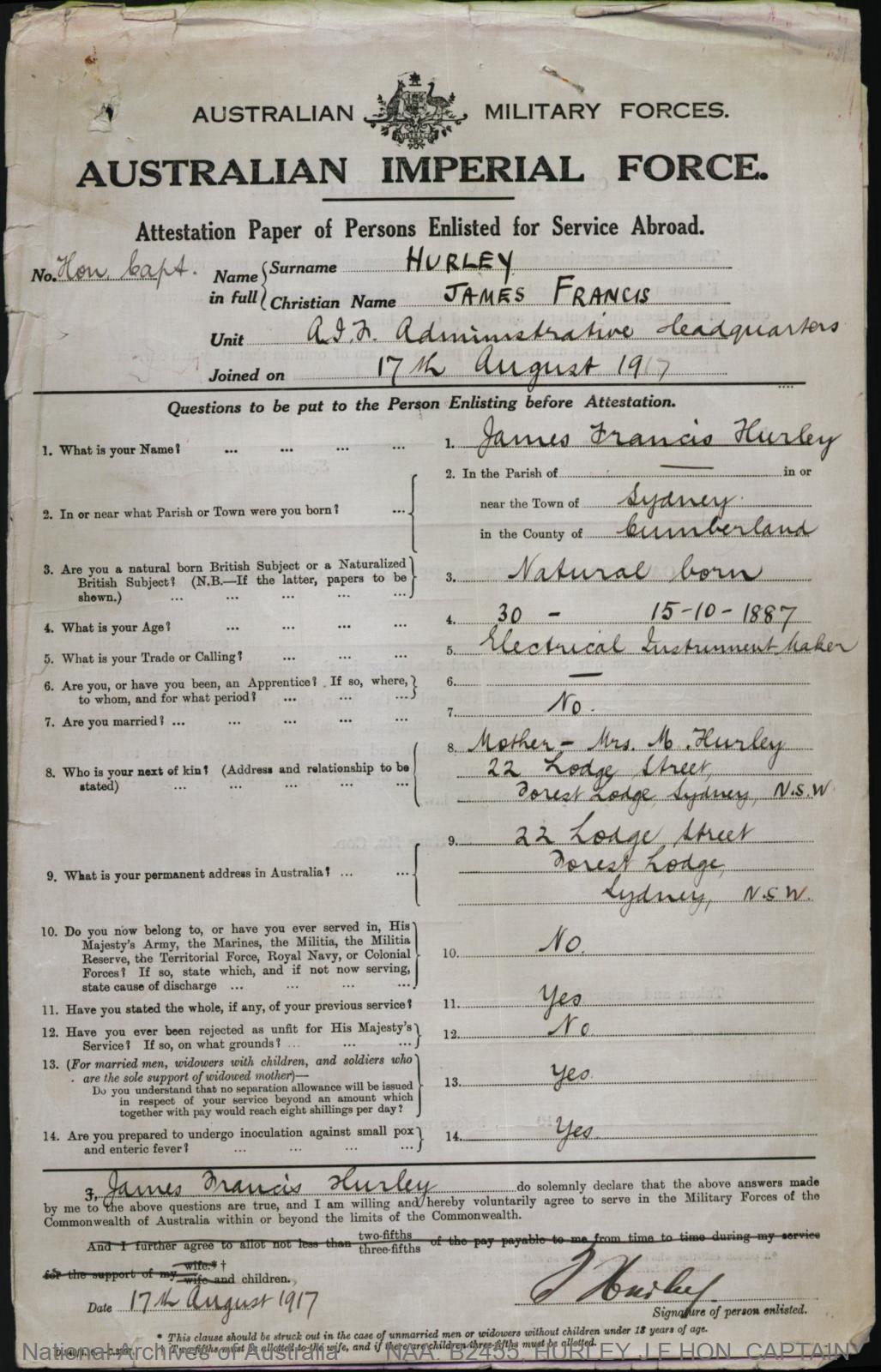

The local connection: Frank Hurley, photographer

During his lifetime Frank Hurley spent more than four years in Antarctica. At the age of 23, in 1908, Hurley learned that Australian explorer Douglas Mawson was planning an expedition to Antarctica; fellow Sydney-sider Henri Mallard in 1911, recommended Hurley for the position of official photographer to Mawson's Australasian Antarctic Expedition, ahead of himself. Hurley asserts in his biography that he then cornered Mawson as he was making his way to their interview on a train, using the advantage to talk his way into the job. Mawson was persuaded, while Mallard, who was the manager of Harringtons—a local Kodak franchise—to which Hurley was in debt, provided photographic equipment. The expedition departed in 1911, returning in 1914. On his return, he edited and released a documentary, Home of the Blizzard, using his footage from the expedition.

Hurley was also the official photographer on Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition which set out in 1914 and was marooned until August 1916. Hurley produced many pioneering colour images of the expedition using the then-popular Paget process of colour photography. He photographed in South Georgia in 1917. He later compiled his records into the documentary film South in 1919. His footage was also used in the 2001 IMAX film Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure. He returned to the Antarctic in 1929 and 1931, on Mawson's British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition.

Frank Hurley has a few connections with our area. When finally he decided to dwell for any length of time in one place, it was Collaroy Plateau he settled in, leaving this world in 1962 from there. During the 1930’s he utilised Loggon Rock an original log cabin, complete with twig windows and a wooden floor at Whale Beach, the quaint weekender built by Alexander Stewart Jolly for Franks’ uncle and friend of Jolly, Colonel Lionel Hurley, (who was film censor, designed 1929)in 1931.

Hurley was the third of five children to 1880 married Edward Harrison and Margaret Hurley (nee Bouffier) sister-in-law to Catherine Bouffier, mother-in-law of Herbert Fitzpatrick, the man who subdivided Scotland Island in the 1920s and the lady after whom Catherine Park on the island is named. Born in 1889 at Waterloo to Richard and Elizabeth Fitzpatrick (nee Finneran), Herbert James Fitzpatrick would meet Agnes Florence Bouffier in the early 1920's and then marry her - their honeymoon was spent on the island.

BOUFFIER—GATTENHOF.— May 4, by special license, at St. Mary's Pro-Cathedral, by the Rev. P. J. Mahony, Frank James, the youngest son of Henry Joseph Bouffier, of Marcobrunner Estate, Hunter River, N.S.W., to Kate, second daughter of Stephen Gattenhof, Eltville, Potts Point, Sydney.

HURLEY—BOUFFIER.— April 20, at St. Patrick's, Cessnock, N. S. Wales, by the Rev. M. Foran, Edward Harrison Hurley, eldest son of James Hurley, Esq., Glebe Road, Sydney, to Margaret Agnes Bouffier, youngest daughter of H. J. Bouffier, Esq., Marcobrunner Vineyard, Cessnock, N. S. Wales. Family Notices (1880, May 15). Freeman's Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1932), p. 11. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article133488996

Fitzpatrick's parents, living at Manly in 1916, and a tragedy in her own family which brought Florence Bouffier to Manly, the loss of her sister Elvina (married name Noonan)who had lived at 'Wonga', Darley Road, Manly, had at least one happy outcome:

Miss Florence Bouffier, youngest daughter of the late Mr. Frank Bouffier, and Mrs. Bouffier, of 'The Briars,' Randwick, was married recently at the Sacred Heart Church, Randwick. The bridegroom was Herbert Fitzpatrick, son of Mr. and Mrs. Richard Fitzpatrick, of Tower-street, Manly. Rev. Father Flemming, assisted by Rev. Father. Carroll, solemnised the marriage, during which Mr. Cottingham sang an 'Ave Maria.' The bride, who was escorted to the altar by Mr. T. Roarty, wore a charming gown of white crepe morocain, finished at the ceinture with a diamond buckle. A Limerick lace veil, held in place by a couplet of silver leaves and orange blossom, entirely covered the gown, and a shower bouquet of white watsonias and carnations was carried. The bride's sister Hilda was in attendance, wearing a frock of heliotrope morocain and white georgette, and a black picture hat adorned with white ospreys. Her bouquet was of pink and mauve carnations. Mr. Harold Fitzpatrick attended his brother as best man. A reception was held in the white and gold room of the Mary Elizabeth, where Mrs. Bouffier received the guests. The bride's travelling dress was of nattier blue georgette, worn with a plain brule hat, trimmed with French posies. The guests included the Misses Hilda and Pat Noonan, May and Vonnie Frost, Mr. and Mrs. McCoy, Mr. Ducker, Mr. and Mrs. Ash, Mr. and Mrs. Duggan, Mr. and Mrs. Parker, Mr. and Mrs. Henderson, Mr. and Mrs. Ledger, Miss Vera Fitzpatrick, Mrs. Hermanson, the Misses Kate and Ivy Carroll, Miss Kathleen Roarty, Miss Mitchell, Mr. Fox, Mr. Blaxland and Mr. Butcher. SOCIAL NEWS AND GOSSIP. (1924, January 17). The Catholic Press (NSW : 1895 - 1942), p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106403779

Florence Bouffier, born in Sydney in 1890 was the daughter of Frank James Bouffier and Catherine (Kate), and one of the sons of Joseph H, whose father, Henry Joseph brought wine to 'Cessnock':

Messrs. Bouffier Brothers' Exhibit. (See illustration on next page.) Messrs. Bouffier Brothers had a very fine wine trophy at the show. The artistic blending of the various colors, the numerous gold and silver prize cups, trophies, and medals, and other attractions made the whole display most attractive, and the firm was warmly congratulated on the excellence of their exhibits. Some twenty different varieties of wines were shown by the Messrs. Bouffier Brothers, including ports, sherries, hocks, chablis, sauterne, clarets, burgundies, etc., of various qualities and vintages, which, upon being submitted for examination, were considered to compare favorably with the choicest vintages of the old world. This speaks well for the future wine-growing industry of Australia, and it is much to be lamented that vineyards are not being more rapidly extended. Much has been done by the firm of Messrs. Bouffier Brothers towards popularising Australian wines in the colonies, as also in the old world, their consignments to Berlin of red and white wines having received the highest commendation from German experts appointed for their examination.

Messrs. Bouffier Brothers' Exhibit. (See illustration on next page.) Messrs. Bouffier Brothers had a very fine wine trophy at the show. The artistic blending of the various colors, the numerous gold and silver prize cups, trophies, and medals, and other attractions made the whole display most attractive, and the firm was warmly congratulated on the excellence of their exhibits. Some twenty different varieties of wines were shown by the Messrs. Bouffier Brothers, including ports, sherries, hocks, chablis, sauterne, clarets, burgundies, etc., of various qualities and vintages, which, upon being submitted for examination, were considered to compare favorably with the choicest vintages of the old world. This speaks well for the future wine-growing industry of Australia, and it is much to be lamented that vineyards are not being more rapidly extended. Much has been done by the firm of Messrs. Bouffier Brothers towards popularising Australian wines in the colonies, as also in the old world, their consignments to Berlin of red and white wines having received the highest commendation from German experts appointed for their examination.

In Sydney the firm has three establishments: the retail and single bottle department, is situated at 97 Oxford street, which is one of the most replete establishments of the kind in the Australian colonies, the requirements of both rich and poor being alike supplied, the prices by the single bottle ranging from le per quartto 7s 6d per bottle for choice old vintages the cheaper wine being in such demand hy the working classes, the firm experience a positive difficulty in keeping up the supply, as may be judged from the fact that nearly 100 dozen bottles of this wine alone have been sold in one day; the bulk store, where the wines are received from the vineyard and given the finishing polish by Mr. F.J. Bouffier, one of the most eminent wine experts of the day, previous to being bottled; the boiled wine store, where recently-bottled wines are binned for, at least a year before being placed on the market. It will be seen the principle upon which the business of Messrs.Bouffier Brothers is founded brings the every-day use of wine within the reach of all classes, and that the facilities thus offered should be freely availed of is not surprising, which is clearly demonstrated by the increasing demand for the firm's wines. Mr. "Jack" Moses, who has become quite an institution at the western and southern shows, is the firm's representative in those districts; whilst Mr. W. M. Hania m is the northern representative. Messrs. Bouffier Brothers' Wine Trophy. (See letterpress on previous page.) Messrs. Bouffier Brothers' Exhibit. (1897, May 1). Australian Town and Country Journal (NSW : 1870 - 1907), p. 20. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71292693

Australian Wines. At the Commonwealth State Banquet A First-class Native Product. The name of Bouffier Bros., Vignerons and Wine Merchants, of the Hunter River, and 97Oxford-street Sydney, is a household word throughout these districts, and, in fact throughout Australasia. They make a first-class wine, which advertises itself wherever used. The firm has been established over 50 years, for it was in the early forties when the father of_ the present Messrs. Bouffier Bros, planted his vineyard in the valley, of the Hunter. This business has grown wonderfully since then, and is now the largest in the Southern Hemisphere. These wines have secured numerous prizes in all parts of the world, inside and outside of Australia, and have gained much favor among consumers in : the land where they are produced. At therecent Commonwealth State banquet the wines were supplied by Messrs. Bouffier Bros— a fact that speaks fur itself. Their sampling kiosk will be at the ensuing Maclean Show, in charge of Mr. S. V. Bouffier, who will be pleased to receive orders on behalf of the firm. Australian Wines. (1901, March 26). The Clarence River Advocate (NSW : 1898 - 1949), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article121368083 - 'SV' is F J's son Stephen V

MRS. GRACE BOUFFIER The death took place last Friday evening of a well-known resident of Cessnock in the person of Mrs Grace Mary Bouffier, aged 72 years. The deceased had only been ill a fortnight, and a week before had been operated upon In the Cessnock Hospital. Her condition became so low that she gradually sank and died. The deceased lady resided In Cessnock nearly all her life coming here with her father, the late, Mr Bernard McGrane, when a child. Her remains were laid to rest in the Roman Catholic portion of the Sandgate cemetery alongside those of her son. The late Mrs. Bouffler was one of the oldest of Cessnock district residents . She is survived by three daughters, Mrs. Grant Pentland (Cessnock), Mrs. J. Osborne (Brisbane) and Miss Kitty Bouffier. 'The death of Mrs. Bouffier recalls the interesting fact that both her husbands' and her family(McGrane's) are connected with the earlier history of the pioneering days of the Cessnock district. The Bouffier family came to Cessnock in the early 60's, and settled on the land facing the Wollombi Road known for years as Bouffier's Estate, but later on becoming known as Shedden's Estate, when it was purchased for sub-division. It is a matter of history that Henry Joseph Bouffier planted the first vineyard in the Cessnock district, the date being given as 1866. The vineyard will be well remembered by residents of fifteen years back.- Henry Joseph Bouffier was found dead having been thrown from his horse on the Pokolbin road on November,1882, the site of the finding of his body being marked by a wooden cross— which is a landmark today. Joseph Bouffier was a son of the old pioneer, and married the deceased at Cessnock.

The original Bernard MacGrane arrived in the Wollombi district as a young man, subsequently, after keeping an hotel at Millfield in the early 50's, moved to Cessnock where he had acquired portions of the original Cessnock Estate, subdivided in 1853. He built the original stone building licensed as the first, and for 48 years, the only hotel in Cessnock, known as the Cessnock Inn, but now the Cessnock Hotel. He, however did not secure the license, that being issued to his. brother-in-law, Michael Carroll who at that time had a carriers Business in Sydney, but sold out, to takeover the newly erected hotel. He at that time was living in the old Cessnock homestead, in the vicinity of' the present modern Cessnock District Hospital. The late Mrs. Bouffier was one of his daughters. Another daughter, Nora, married another son of the pioneer Bouffier, so that the pioneer families were doubly connected. Mr. Bernard ('Bun') McGrane is a brother of the deceased, Mrs. Bouffier. In connection with the reference to the death of the late Henry Joseph Bouffier, the following is taken from a file of the Maitland Mail November 25th 1882. On Tuesday last Mr H J Bouffier of Marcobruner Vineyard, Cessnock, was found lying dead on the Pokolbin Road. He had been out riding and it is supposed that his horse had either stumbled or thrown him. The horse was found quietly grazing a short distance away from where the deceased was found. In-formation was given to Constable O'Brien and the body was removed to the Cessnock Inn where the Coroner (Mr. A. Vindin), held an inquest on Wednesday morning. From Dr Powers Evidence it was elicited that there was a fracture at the base of the skull which was in itself sufficient to cause death. The jury found in accordance with the Testimony of Dr. Power. The deceased had been a resident of this district for a considerable time and was greatly respected. MRS. MEANS. (1932, January 12). The Cessnock Eagle and South Maitland Recorder (NSW : 1913 - 1954), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article99482634

Frank Hurley's father died in 1907 and he apparently ran away soon after, aged 13, to take on work in the Lithgow steel mill, returning home two years later.

HURLEY.— The Friends of Mrs. MARGARET A. HURLEY are kindly invited to attend the Funeral her late beloved HUSBAND, Edward Harrison ; which will leave her residence, No. 2 Lodge-street, Forest Lodge, THIS (Thursday) AFTERNOON, at 2 o'clock, for Waverley Cemetery. WOOD and COMPANY.

HURLEY.— The friends of Mr. and Mrs. C. MURPHY are kindly invited to attend the Funeral of their late beloved FATHER, Edward Harrison Hurley ; which will move from his late residence No. 22 Lodge-st., Forest Lodge, THIS (Thursday) AFTERNOON, at 2 o'clock, for Waverley Cemetery. WOOD and CO.

HURLEY.— The Friends of Messrs. HENRY E., EDWIN D., JAMES F., and Miss DOROTHY HURLEY are kindly invited to attend the Funeral of their late beloved FATHER, Edward Harrison Hurley, which will leave his late residence, No. 22 Lodge-st, Forest Lodge, THIS (Thursdav) AFTFRNOON, at 2 o'clock.

HURLEY.— The Members of the Printing Trades Federation Council are respectfully invited to at-tend the Funeral of their late Secretary, Mr. E. HAR-RISON HURLEY ; to move from 22 Lodge-street, Forest Lodge, THIS AFTERNOON, at 2 o'clock, for Waverley Cemetery.

JAMES W. SPICER,

President. N.S.W. TYPOGRAPHICAL ASSOCIATION.— The Members are respectfully invited to attend the Funeral of their late Secretary, Mr. E. HARRISON HURLEY; to move from his late residence, 22 Lodge-street, Forest Lodge, THIS AFTERNOON, at 2 o'clock, for Waverley Cemetery.

W. J. RATCLIFFE, President

ROBT. H. YORK, Secretary pro tem. Family Notices (1907, November 14). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14904202

According to Vivianne Byrnes, Catherine’s great-granddaughter, Catherine kindled Frank's love of photography. Vivianne tells of how, upon Frank’s return from his first wayward adventure, Catherine let him sell the empty bottles from her Sydney wine bar. Frank then used the money to buy his first camera. Apparently the family, including Catherine’s daughter Florence (after whom Florence Terrace is named) used to picnic on South Head and Bondi so that young Frank could spend ‘endless hours’ photographing waves. [1.]

Catherine and Frank Bouffier, 1887 Catherine Bouffier, wearing a ‘grape motif’ lace, 1897

(photos supplied by Vivianne Byrnes), visit: The Two Catherines Café by Robyn Iredale

Mr. Hurley was also one of the first to use aerial photography, commencing with his coverage of World War One and, later, provided us with much used images of our own area from 1945's on. He engaged in aerial photography with Brud Rees on his Piper Cub float plane. The Hurley's had settled in Edgecliffe Boulevard, Collaroy Plateau after WWII, where Frank, a lover of local wildflowers, built a substantial garden.

Of his part in the Shackleton venture, Hurley outlined his own experience in this report, apparently taken from a letter to his mother when he returned to South Georgia island to get additional scenes to complete his film, In the Grip of Polar Ice:

WITH SHACKLETON'S MEN

FRANK HURLEY'S THRILLING STORY SIX MONTHS ON ICE FLOE

Ship Crushed to Pieces by Pack LIFE ON ELEPHANT ISLAND

Over two years ago, an Antarctic expedition, under the command of Sir Ernest Shackleton, left South Georgia for the Weddell Sea. The ship used was the Endurance. This was her last voyage. Mr. Frank Hurley, the official photographer of the expedition, has a thrilling story to tell of his experiences. In a letter to his mother, who resides at Forest Lodge, he makes little of his own work, but glories In the work of the other members.

"After two years wandering in unknown seas and unexplored lands," Mr. Hurley wrote from Patagonia, "we have all arrived safely within the spheres of civilisation. We have had no news from the outside world during the course of our wanderings, and now learn for the first time of the continuance of the terrible war.: "For ourselves, we., have successfully emerged from the most extraordinary series of mishaps and adventures that has ever befell voyagers to these seas. Most of the principal events you will no doubt have learned through the press, so I will give you an insight into the way we have spent our time during the past few years, and leave the details till I return home, and recount them personally.

"We left Buenos Ayres In the Endurance on October 26, 1914, and arrived at the island of South Georgia just short of a week later. Here we were surprised to find many large whaling stations in full operation. We spent a month engaged In various scientific work and waiting for the season to advance, so that the ice conditions might be more navigable to the south with the approach of summer. South Georgia is an island of magnificent scenery, rugged and mountainous, the ranges always mantled with snows and glaciers. It has the reputation of having atrocious weather, which reputation it maintained during our stay, fierce gales and incessant snow falling.

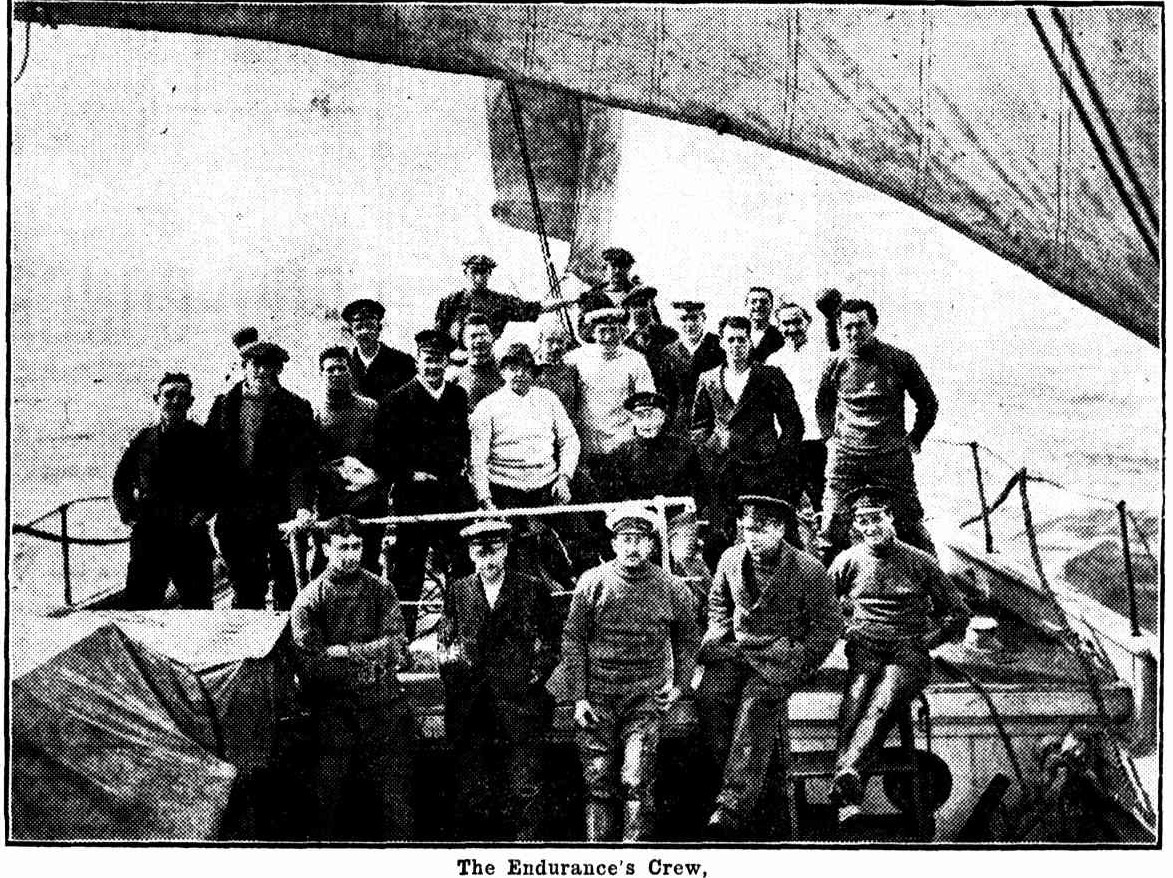

The Endurance's Crew, Taken after she had left South Georgia, and just before she encountered the pack-ice. Shackleton is seen seated in the centre of the second row. He is wearing a white coat and a cloth hat. Frank Hurley is on his left at the extreme end of the same row. He is standing, and is wearing a dark jersey.

SHIP'S FIGHT WITH PACK ICE

"At the beginning of December the Endurance headed for the south, and two days later met with the first pack ice. The ice was much further north than we expected, so that wo apprehended a severe season, a state of affairs eloquently borne out by the congested nature of- the ice in the Weddell Sea and the subsequent loss of our ship. "For six weeks we did nothing but ram and force a passage through the densely-packed ice, until on ' July 16, 1916, our further progress, to the south, was barred by impenetrable pack ice. Wo had rammed our way through a sea of ice so dense that at times no ocean was visible, except a few 'lanes' of water that wound like threads among the immense floes.

"We had passed through 1500 miles of Ice, and there in front of us lay our destination only 40 miles away! This it was impossible to reach owing to the treacherous nature of the ice, which occasionally would break up and so render all attempts to reach the land across the sea-loo suicidal. "To add to this exasperating circumstance, '.the temperature fell so that we were the helpless spectators of the floes freezing together and consolidating around the ship.

PRISONERS FOR FIFTEEN MONTHS.

"We were the prisoners of the ice, and our gaoler did not free us from frozen captivity until fifteen months later!