UN Secretary-General's special address on climate action "A Moment of Truth" [as delivered]

June 5, 2024

Dear friends of the planet,

Today is World Environment Day.

It is also the day that the European Commission’s Copernicus Climate Change Service officially reports May 2024 as the hottest May in recorded history.

This marks twelve straight months of the hottest months ever.

For the past year, every turn of the calendar has turned up the heat.

Our planet is trying to tell us something. But we don't seem to be listening.

Dear Friends,

The American Museum of Natural History is the ideal place to make the point.

This great Museum tells the amazing story of our natural world. Of the vast forces that have shaped life on earth over billions of years.

Humanity is just one small blip on the radar.

But like the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs, we’re having an outsized impact.

In the case of climate, we are not the dinosaurs.

We are the meteor.

We are not only in danger.

We are the danger.

But we are also the solution.

So, dear friends,

We are at a moment of truth.

The truth is … almost ten years since the Paris Agreement was adopted, the target of limiting long-term global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is hanging by a thread.

The truth is … the world is spewing emissions so fast that by 2030, a far higher temperature rise would be all but guaranteed.

Brand new data from leading climate scientists released today show the remaining carbon budget to limit long-term warming to 1.5 degrees is now around 200 billion tonnes.

That is the maximum amount of carbon dioxide that the earth’s atmosphere can take if we are to have a fighting chance of staying within the limit.

The truth is… we are burning through the budget at reckless speed – spewing out around 40 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide a year.

We can all do the math.

At this rate, the entire carbon budget will be busted before 2030.

The truth is … global emissions need to fall nine per cent every year until 2030 to keep the 1.5 degree limit alive.

But they are heading in the wrong direction.

Last year they rose by one per cent.

The truth is… we already face incursions into 1.5-degree territory.

The World Meteorological Organisation reports today that there is an eighty per cent chance the global annual average temperature will exceed the 1.5 degree limit in at least one of the next five years.

In 2015, the chance of such a breach was near zero.

And there’s a fifty-fifty chance that the average temperature for the entire next five-year period will be 1.5 degrees higher than pre-industrial times.

We are playing Russian roulette with our planet.

We need an exit ramp off the highway to climate hell.

And the truth is… we have control of the wheel.

The 1.5 degree limit is still just about possible.

Let’s remember – it’s a limit for the long-term – measured over decades, not months or years.

So, stepping over the threshold 1.5 for a short time does not mean the long-term goal is shot.

It means we need to fight harder.

Now.

The truth is… the battle for 1.5 degrees will be won or lost in the 2020s – under the watch of leaders today.

All depends on the decisions those leaders take – or fail to take – especially in the next eighteen months.

It’s climate crunch time.

The need for action is unprecedented but so is the opportunity – not just to deliver on climate, but on economic prosperity and sustainable development.

Climate action cannot be captive to geo-political divisions.

So, as the world meets in Bonn for climate talks, and gears up for the G7 and G20 Summits, the United Nations General Assembly, and COP29, we need maximum ambition, maximum acceleration, maximum cooperation - in a word maximum action.

So dear friends,

Why all this fuss about 1.5 degrees?

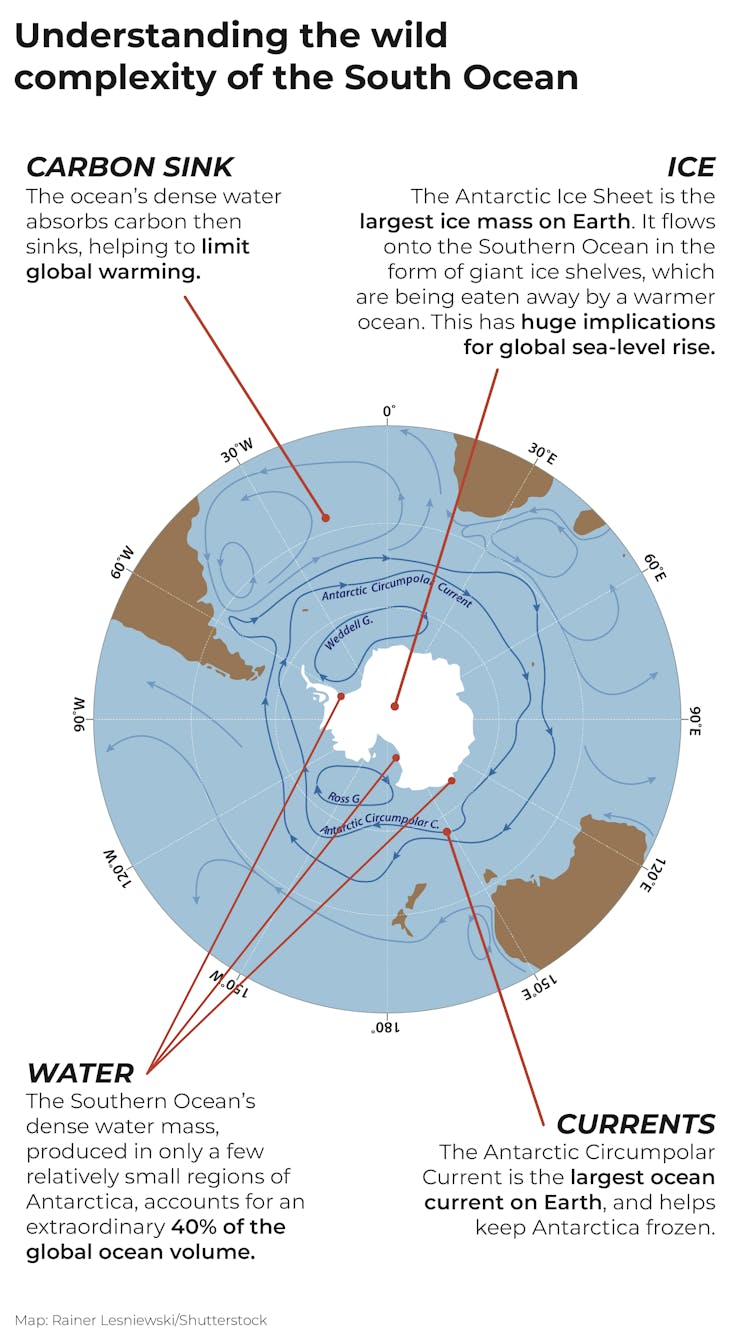

Because our planet is a mass of complex, connected systems. And every fraction of a degree of global heating counts.

The difference between 1.5 and two degrees could be the difference between extinction and survival for some small island states and coastal communities.

The difference between minimizing climate chaos or crossing dangerous tipping points.

1.5 degrees is not a target. It is not a goal. It is a physical limit.

Scientists have alerted us that temperatures rising higher would likely mean:

The collapse of the Greenland Ice Sheet and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet with catastrophic sea level rise;

The destruction of tropical coral reef systems and the livelihoods of 300 million people;

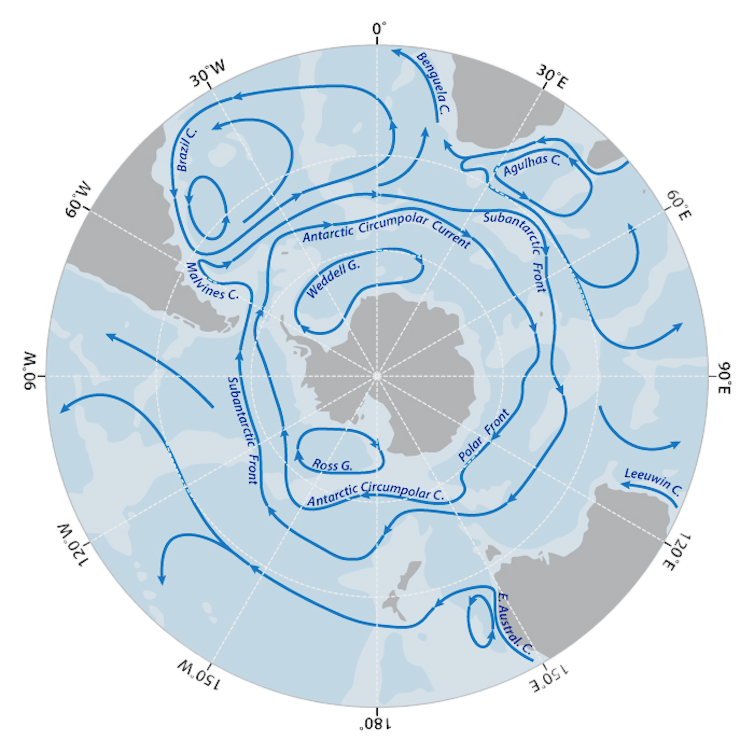

The collapse of the Labrador Sea Current that would further disrupt weather patterns in Europe;

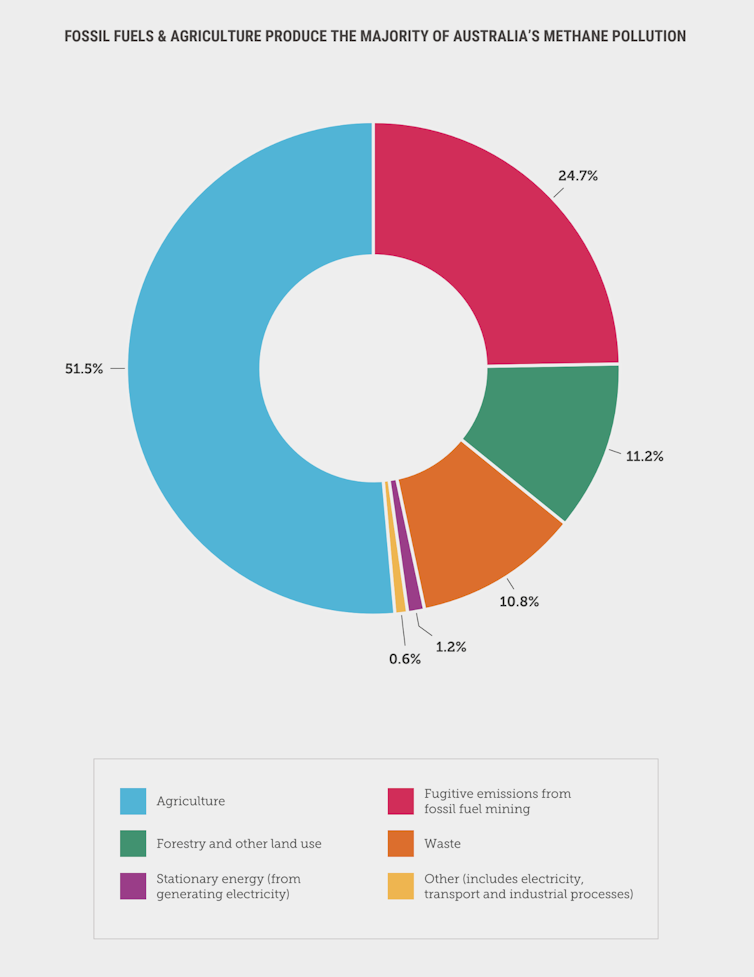

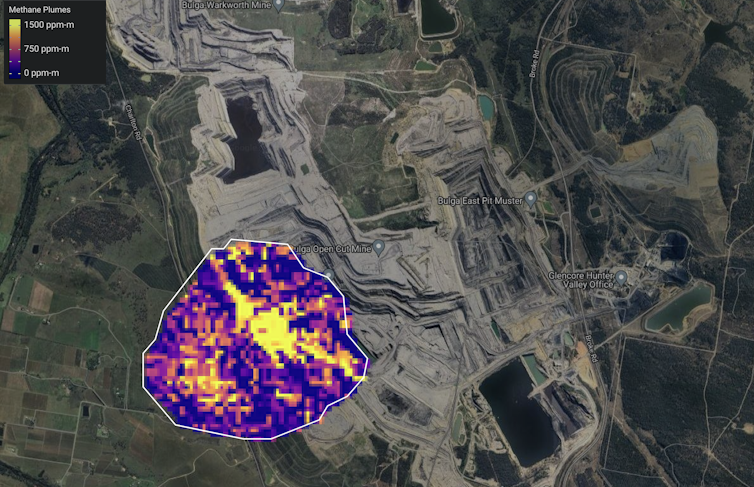

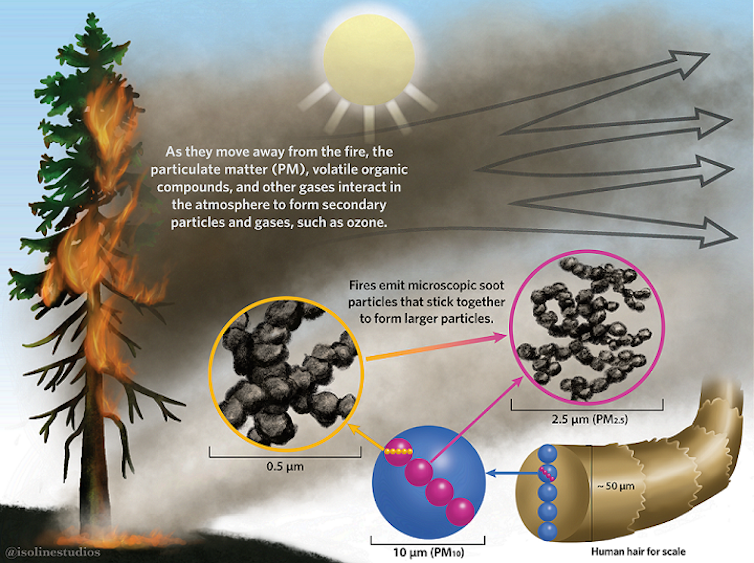

And widespread permafrost melt that would release devastating levels of methane, one of the most potent heat-trapping gasses.

Even today, we’re pushing planetary boundaries to the brink – shattering global temperature records and reaping the whirlwind.

And it is a travesty of climate justice that those least responsible for the crisis are hardest hit: the poorest people; the most vulnerable countries; Indigenous Peoples; women and girls.

The richest one per cent emit as much as two-thirds of humanity.

And extreme events turbocharged by climate chaos are piling up:

Destroying lives, pummelling economies, and hammering health;

Wrecking sustainable development; forcing people from their homes; and rocking the foundations of peace and security – as people are displaced and vital resources depleted.

Already this year, a brutal heatwave has baked Asia with record temperatures – shrivelling crops, closing schools, and killing people.

Cities from New Delhi, to Bamako, to Mexico City are scorching.

Here in the US, savage storms have destroyed communities and lives.

We’ve seen drought disasters declared across southern Africa;

Extreme rains flood the Arabian Peninsula, East Africa and Brazil;

And a mass global coral bleaching caused by unprecedented ocean temperatures, soaring past the worst predictions of scientists.

The cost of all this chaos is hitting people where it hurts:

From supply-chains severed, to rising prices, mounting food insecurity, and uninsurable homes and businesses.

That bill will keep growing. Even if emissions hit zero tomorrow, a recent study found that climate chaos will still cost at least $38 trillion a year by 2050.

Climate change is the mother of all stealth taxes paid by everyday people and vulnerable countries and communities.

Meanwhile, the Godfathers of climate chaos – the fossil fuel industry – rake in record profits and feast off trillions in taxpayer-funded subsidies.

Dear friends,

We have what we need to save ourselves.

Our forests, our wetlands, and our oceans absorb carbon from the atmosphere. They are vital to keeping 1.5 alive, or pulling us back if we do overshoot that limit. We must protect them.

And we have the technologies we need to slash emissions.

Renewables are booming as costs plummet and governments realise the benefits of cleaner air, good jobs, energy security, and increased access to power.

Onshore wind and solar are the cheapest source of new electricity in most of the world – and have been for years.

Renewables already make up thirty percent of the world’s electricity supply.

And clean energy investments reached a record high last year – almost doubling in the last ten [years].

Wind and solar are now growing faster than any electricity source in history.

Economic logic makes the end of the fossil fuel age inevitable.

The only questions are: Will that end come in time? And will the transition be just?

Dear friends,

We must ensure the answer to both questions is: yes.

And we must secure the safest possible future for people and planet.

That means taking urgent action, particularly over the next eighteen months:

To slash emissions;

To protect people and nature from climate extremes;

To boost climate finance;

And to clamp down on the fossil fuel industry.

Let me take each element in turn.

First, huge cuts in emissions. Led by the huge emitters.

The G20 countries produce eighty percent of global emissions – they have the responsibility, and the capacity, to be out in front.

Advanced G20 economies should go furthest, fastest;

And show climate solidarity by providing technological and financial support to emerging G20 economies and other developing countries.

Next year, governments must submit so-called nationally determined contributions – in other words, national climate action plans. And these will determine emissions for the coming years.

At COP28, countries agreed to align those plans with the 1.5 degree limit.

These national plans must include absolute emission reduction targets for 2030 and 2035.

They must cover all sectors, all greenhouse gases, and the whole economy.

And they must show how countries will contribute to the global transitions essential to 1.5 degrees – putting us on a path to global net zero by 2050; to phase out fossil fuels; and to hit global milestones along the way, year after year, and decade after decade.

That includes, by 2030, contributing to cutting global production and consumption of all fossil fuels by at least thirty percent; and making good on commitments made at COP28 – on ending deforestation, doubling energy efficiency and tripling renewables.

Every country must deliver and play their rightful part.

That means that G20 leaders working in solidarity to accelerate a just global energy transition aligned with the 1.5 degree limit. They must assume their responsibilities.

We need cooperation, not finger-pointing.

It means the G20 aligning their national climate action plans, their energy strategies, and their plans for fossil fuel production and consumption, within a 1.5 degree future.

It means the G20 pledging to reallocate subsidies from fossil fuels to renewables, storage, and grid modernisation, and support for vulnerable communities.

It means the G7 and other OECD countries committing: to end coal by 2030; and to create fossil-fuel free power systems, and reduce oil and gas supply and demand by sixty percent – by 2035.

It means all countries ending new coal projects – now. Particularly in Asia, home to ninety-five percent of planned new coal power capacity.

It means non-OECD countries creating climate action plans to put them on a path to ending coal power by 2040.

And it means developing countries creating national climate action plans that double as investment plans, spurring sustainable development, and meeting soaring energy demand with renewables.

The United Nations is mobilizing our entire system to help developing countries to achieve this through our Climate Promise initiative.

Every city, region, industry, financial institution, and company must also be part of the solution.

They must present robust transition plans by COP30 next year in Brazil – at the latest:

Plans aligned with 1.5 degrees, and the recommendations of the UN High-Level Expert Group on Net Zero.

Plans that cover emissions across the entire value chain;

That include interim targets and transparent verification processes;

And that steer clear of the dubious carbon offsets that erode public trust while doing little or nothing to help the climate.

We can’t fool nature. False solutions will backfire. We need high integrity carbon markets that are credible and with rules consistent with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees.

I also encourage scientists and engineers to focus urgently on carbon dioxide removal and storage – to deal safely and sustainably with final emissions from the heavy industries hardest to clean.

And I urge governments to support them.

But let me be clear: These technologies are not a silver bullet; they cannot be a substitute for drastic emissions cuts or an excuse to delay fossil fuel phase-out.

But we need to act on every front.

Dear Friends,

The second area for action is ramping up protection from the climate chaos of today and tomorrow.

It is a disgrace that the most vulnerable are being left stranded, struggling desperately to deal with a climate crisis they did nothing to create.

We cannot accept a future where the rich are protected in air-conditioned bubbles, while the rest of humanity is lashed by lethal weather in unliveable lands.

We must safeguard people and economies.

Every person on Earth must be protected by an early warning system by 2027. I urge all partners to boost support for the United Nations Early Warnings for All action plan.

In April, the G7 launched the Adaptation Accelerator Hub.

By COP29, this initiative must be translated into concrete action – to support developing countries in creating adaptation investment plans, and putting them into practice.

And I urge all countries to set out their adaptation and investment needs clearly in their new national climate plans.

But change on the ground depends on money on the table.

For every dollar needed to adapt to extreme weather, only about five cents is available.

As a first step, all developed countries must honour their commitment to double adaptation finance to at least $40 billion a year by 2025.

And they must set out a clear plan to close the adaptation finance gap by COP29 in November.

But we also need more fundamental reform.

That leads me onto my third point: finance.

Dear friends,

If money makes the world go round, today’s unequal financial flows are sending us spinning towards disaster.

The global financial system must be part of the climate solution.

Eye-watering debt repayments are drying up funds for climate action.

Extortion-level capital costs are putting renewables virtually out of reach for most developing and emerging economies.

Astoundingly – and despite the renewables boom of recent years – clean energy investments in developing and emerging economies outside of China have been stuck at the same levels since 2015.

Last year, just fifteen per cent of new clean energy investment went to emerging markets and developing economies outside China – countries representing nearly two-thirds of the world’s population.

And Africa was home to less than one percent of last year’s renewables installations, despite its wealth of natural resources and vast renewables potential.

The International Energy Agency reports that clean energy investments in developing and emerging economies beyond China need to reach up to $1.7 trillion a year by the early 2030s.

In short, we need a massive expansion of affordable public and private finance to fuel ambitious new climate plans and deliver clean, affordable energy for all.

This September’s Summit of the Future is an opportunity to push reform of the international financial architecture and action on debt. I urge countries to take it.

And I urge the G7 and G20 Summits to commit to using their influence within Multilateral Development Banks to make them better, bigger, and bolder. And able to leverage far more private finance at reasonable cost.

Countries must make significant contributions to the new Loss and Damage Fund. And ensure that it is open for business by COP29.

And they must come together to secure a strong finance outcome from COP this year – one that builds trust and confidence, catalyses the trillions needed, and generates momentum for reform of the international financial architecture.

But none of this will be enough without new, innovative sources of funds.

It is [high] time to put an effective price on carbon and tax the windfall profits of fossil fuel companies.

By COP29, we need early movers to go from exploring to implementing solidarity levies on sectors such as shipping, aviation, and fossil fuel extraction – to help fund climate action.

These should be scalable, fair, and easy to collect and administer.

None of this is charity.

It is enlightened self-interest.

Climate finance is not a favour. It is fundamental element to a liveable future for all.

Dear friends,

Fourth and finally, we must directly confront those in the fossil fuel industry who have shown relentless zeal for obstructing progress – over decades.

Billions of dollars have been thrown at distorting the truth, deceiving the public, and sowing doubt.

I thank the academics and the activists, the journalists and the whistleblowers, who have exposed those tactics – often at great personal and professional risk.

I call on leaders in the fossil fuel industry to understand that if you are not in the fast lane to clean energy transformation, you are driving your business into a dead end – and taking us all with you.

Last year, the oil and gas industry invested a measly 2.5 percent of its total capital spending on clean energy.

Doubling down on fossil fuels in the twenty-first century, is like doubling down on horse-shoes and carriage-wheels in the nineteenth.

So, to fossil fuel executives, I say: your massive profits give you the chance to lead the energy transition. Don’t miss it.

Financial institutions are also critical because money talks.

It must be a voice for change.

I urge financial institutions to stop bankrolling fossil fuel destruction and start investing in a global renewables revolution;

To present public, credible and detailed plans to transition [funding] from fossil fuels to clean energy with clear targets for 2025 and 2030;

And to disclose your climate risks – both physical and transitional – to your shareholders and regulators. Ultimately such disclosure should be mandatory.

Dear friends,

Many in the fossil fuel industry have shamelessly greenwashed, even as they have sought to delay climate action – with lobbying, legal threats, and massive ad campaigns.

They have been aided and abetted by advertising and PR companies – Mad Men – remember the TV series - fuelling the madness.

I call on these companies to stop acting as enablers to planetary destruction.

Stop taking on new fossil fuel clients, from today, and set out plans to drop your existing ones.

Fossil fuels are not only poisoning our planet – they’re toxic for your brand.

Your sector is full of creative minds who are already mobilising around this cause.

They are gravitating towards companies that are fighting for our planet – not trashing it.

I also call on countries to act.

Many governments restrict or prohibit advertising for products that harm human health – like tobacco.

Some are now doing the same with fossil fuels.

I urge every country to ban advertising from fossil fuel companies.

And I urge news media and tech companies to stop taking fossil fuel advertising.

We must all deal also with the demand side. All of us can make a difference, by embracing clean technologies, phasing down fossil fuels in our own lives, and using our power as citizens to push for systemic change.

In the fight for a liveable future, people everywhere are far ahead of politicians.

Make your voices heard and your choices count.

Dear friends,

We do have a choice.

Creating tipping points for climate progress – or careening to tipping points for climate disaster.

No country can solve the climate crisis in isolation.

This is an all-in moment.

The United Nations is all-in – working to build trust, find solutions, and inspire the cooperation our world so desperately needs.

And to young people, to civil society, to cities, regions, businesses and others who have been leading the charge towards a safer, cleaner world, I say: Thank you.

You are on the right side of history.

You speak for the majority.

Keep it up.

Don’t lose courage. Don’t lose hope.

It is we the Peoples versus the polluters and the profiteers. Together, we can win.

But it’s time for leaders to decide whose side they’re on.

Tomorrow it will be too late.

Now is the time to mobilise, now is the time to act, now is the time to deliver.

This is our moment of truth.

And I thank you.

![]()

_Scottsdale_4.jpg?timestamp=1724445994142)

.jpg?timestamp=1724454711323)

Our August public meeting is focused on the Permaculture ethos of People Care. We’ll hear from two very special speakers, Leigh McGaghey and Guy Morel.

Our August public meeting is focused on the Permaculture ethos of People Care. We’ll hear from two very special speakers, Leigh McGaghey and Guy Morel. Led by Master Basket Weaver, Aunty Karleen Green, this workshop is an invitation for people of all ages to connect with the stories, traditions, and living culture of Australia's First Nations. Adults will be forming a weaving circle to learn the art of weaving, and children will be making Indigenous craft, including traditional Sand Goannas. All participants take home a unique item they've created.

Led by Master Basket Weaver, Aunty Karleen Green, this workshop is an invitation for people of all ages to connect with the stories, traditions, and living culture of Australia's First Nations. Adults will be forming a weaving circle to learn the art of weaving, and children will be making Indigenous craft, including traditional Sand Goannas. All participants take home a unique item they've created. At September's public meeting we're very excited to have Clara Roza of Claras Urban Mini Farm talking to us all about the various approaches to growing a wide variety of mushrooms wherever you live!

At September's public meeting we're very excited to have Clara Roza of Claras Urban Mini Farm talking to us all about the various approaches to growing a wide variety of mushrooms wherever you live!

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet