When Labor came to power federally after almost a decade in opposition, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek pledged to turn around Australia’s worsening environmental woes, from extinctions to land clearing to climate change.

While the government has made progress on climate action, protecting biodiversity hasn’t got out of the starting blocks.

In the latest example of inaction, proposed laws to create an independent environmental regulator, Environmental Protection Australia, appear stalled in the Senate. Labor needs the backing of the Coalition or the Greens to push the reform through. At the time of writing, no deals looked likely.

This is a real problem. A stream of audits and reviews have shown Australia’s environmental laws are not fit for purpose. Change is possible – but hard. Keeping the status quo is far easier, no matter how dysfunctional it is.

Pushback in and out of parliament

The latest impasse stems from efforts to overhaul Australia’s ageing and feeble national environment laws, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act.

The failings of the law are no secret. In 2020, an independent review by Graeme Samuel delivered blunt findings: the laws were simply not protecting nature.

Labor drafted stronger laws, but developers and miners quickly pushed back.

So Labor changed tack. It pivoted to a staged reform process – with the full-scale revamp delayed indefinitely.

This week, Labor attempted to pass at least some change – a bill to create an independent environmental regulator, Environmental Protection Australia. But it ran into major roadblocks.

Mining companies such as Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting and Rio Tinto pushed for the regulator to be stripped of its powers in a private letter to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

And Coalition and Greens senators delivered stinging critiques, arguing variously that the regulator would be too strong or too weak.

Crossbenchers and the Greens say to win their support, Labor must end native forest logging nationally and require consideration of climate damage when assessing projects such as new coal mines for approvals.

How did we get into this mess?

In 2000, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act came into force, superseding a patchwork of previous laws.

The laws focused on threatened species and ecosystems but did not mention damage done by climate change.

Almost a quarter of a century later, we still have the same set of laws, described as ineffective or little enforced in audits and reviews.

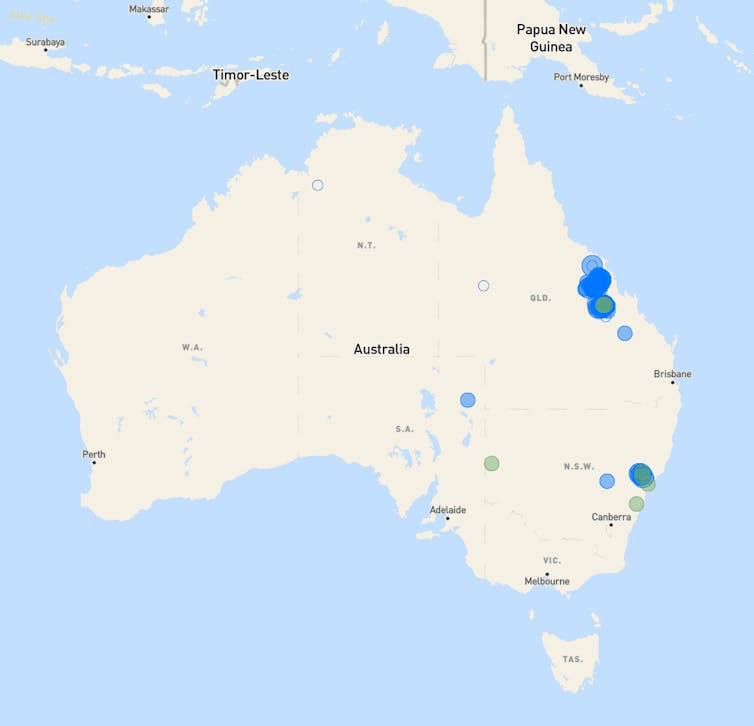

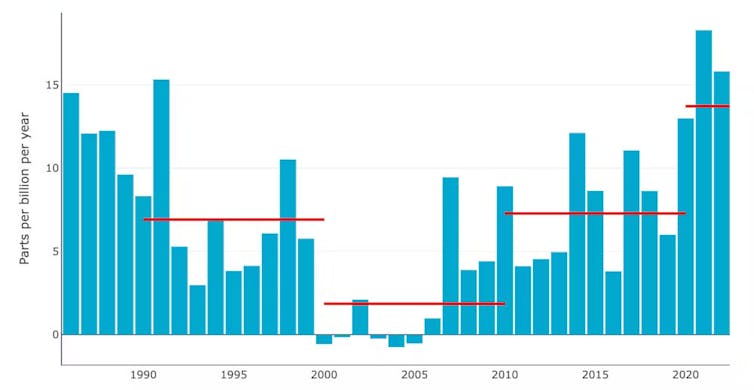

Every year since the act came into force, Austalia’s threatened species populations have actually fallen 2-3%.

When development, agriculture and infrastructure projects do get assessed under these laws, about 99% are approved.

Experts have found the laws permit ongoing destruction of critical habitat for threatened species.

Why? While the environment minister of the day is required to consider environmental impacts of a proposal, they can essentially rule any way they like – even if it goes against the opinion of independent environmental experts, or their own bureaucrats.

Why is change so hard?

The 2020 Samuel review recommended new “national environmental standards” be enforced. These would mean explicitly defining what outcomes for nature we are aiming for, and making sure a development proposal met that standard.

For example, one proposed standard would disallow “unacceptable or unsustainable impacts” on matters of national environmental significance. These matters include internationally important wetlands and nationally threatened species. Other standards include preservation of Australia’s natural world heritage sites, such as the Great Barrier Reef.

In late 2022, Plibersek released Labor’s official response in the form of the Nature Positive Plan.

The plan seemed promising. It recognised the dire state of Australia’s species and ecosystems and labelled the current laws “ineffective”. It promised national environmental standards.

Plibersek vowed to consult on further changes. This led to a proposal to replace the EPBC Act with stronger laws, and create a new regulator – Environment Protection Australia.

As initiailly proposed, this independent agency would have power to make development decisions and ensure compliance. It would only grant approval to a project if it was consistent with national environmental standards. The minister could still step in, but had to give public reasons for doing so, and take advice from the regulator.

However, major lobby groups opposed the proposed overhaul of the laws.

In response, Plibersek changed tactics. She announced environmental reform would be in three stages.

The first was the Nature Repair Market, which passed Parliament late last year. The second stage involved the laws now before the Senate: creating Environment Protection Australia in a weaker form (without the restrictions on discretion in the initial proposal) and a data and monitoring agency, Environment Information Australia.

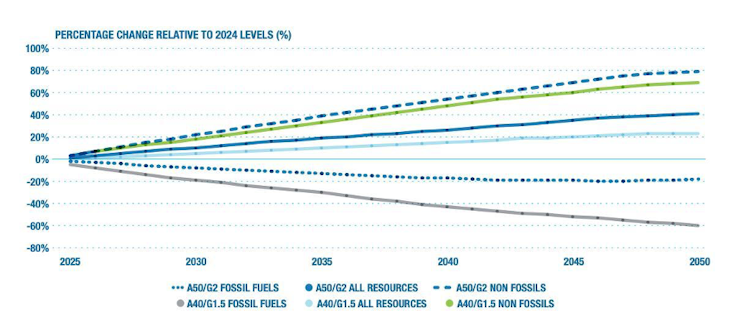

If passed, these bills would create a protection agency – but one which could only enforce the same weak approval laws and be subject to the same broad discretion for the decision-maker. For the agency to have teeth, the government would need to pass stage three, which would reduce discretion, introduce stronger environment laws and create legally binding National Environmental Standards.

Unfortunately, Labor has now deferred these indefinitely.

Stalled at stage two

The government is clearly struggling to pass its stage two reforms.

Conservationists are increasingly worried by the delays, while Western Australia’s mining companies have come out strongly against the EPA.

This is a problem for Labor. Western Australia was instrumental in the party’s election win in 2022 and it needs to shore up seats in the mining-heavy state ahead of the next federal election.

Meanwhile, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has pledged to be the mining sector’s best friend if elected, by cutting “green tape”, fast tracking resource projects and defunding the Environmental Defenders Office.

And the Greens are showing little sign of compromise on their demands.

All this is bad news for our threatened species and sick ecosystems. We know what needs to be done. But our government is showing worrying signs of letting industry and developers control their environmental agenda.![]()

Justine Bell-James, Associate Professor in Environment and Property Law, TC Beirne School of Law, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

.jpg?timestamp=1726794355421)

.jpg?timestamp=1726794383704)

At September's public meeting we're very excited to have Clara Roza of Claras Urban Mini Farm talking to us all about the various approaches to growing a wide variety of mushrooms wherever you live!

At September's public meeting we're very excited to have Clara Roza of Claras Urban Mini Farm talking to us all about the various approaches to growing a wide variety of mushrooms wherever you live!

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

.jpg.opt1498x1119o0,0s1498x1119.jpg?timestamp=1725841455431)

.jpg?timestamp=1725562614573)

.jpg?timestamp=1725564255181)

Led by Master Basket Weaver, Aunty Karleen Green, this workshop is an invitation for people of all ages to connect with the stories, traditions, and living culture of Australia's First Nations. Adults will be forming a weaving circle to learn the art of weaving, and children will be making Indigenous craft, including traditional Sand Goannas. All participants take home a unique item they've created.

Led by Master Basket Weaver, Aunty Karleen Green, this workshop is an invitation for people of all ages to connect with the stories, traditions, and living culture of Australia's First Nations. Adults will be forming a weaving circle to learn the art of weaving, and children will be making Indigenous craft, including traditional Sand Goannas. All participants take home a unique item they've created.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet