Michelle Grattan,

University of CanberraPrime Minister Anthony Albanese has dumped – for the second time – the government’s controversial “Nature Positive” legislation, which had run into strong opposition from the Western Australian Labor government.

Albanese, speaking on The Conversation’s Politics podcast ahead of a fortnight parliamentary sitting starting next week, said there was not enough support for the legislation, which had been on the draft list of bills for next week, circulated by the government.

This is the second time the Prime Minister has pulled back from the legislation. Late last year he also said it did not have enough support, despite Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek believing she had a deal with the Greens and crossbench for its passage.

The legislation would set up a federal Environment Protection Agency, which has riled miners who claim it would add to bureaucracy and delay approvals.

In recent days WA premier Roger Cook, who was instrumental in heading off the legislation last year, has been lobbying the federal government again. WA faces an election on March 8.

In an interview on Saturday, Albanese told The Conversation: “I can’t see that it has a path to success. So at this stage, I can say that we won’t be proceeding with it this term. There simply isn’t a [Senate] majority, as there wasn’t last year.

"The Greens Party on one hand have changed their views”, making another demand during the week, he said. While the Liberals – who began the review of the present Environment Protection Act – “have chosen an obstructionist path,” he said.

Albanese said the government would continue to discuss the issue with stakeholders in the next term of parliament.

“Does the environment and protection act need revision from where it was last century? Quite clearly it does. Everyone says that that’s the case. It’s a matter of working to, in a practical way, a commonsense reform that delivers something that supports industry.

"I want to see faster approvals. We in fact have speeded up approvals substantially.

"But we also want proper sustainability as well.”

Albanese also flagged the government might cut back its legislation to reform rules covering electoral donations and spending in order to get a deal to pass it.

Special Minister of State Don Farrell and the Liberals had been on the brink of a deal in the final week of parliament last year, but negotiations imploded at the eleventh hour.

Albanese told The Conversation he hoped the legislation could still be passed. “I spoke with [Farrell] today, he is consulting with people across the parliament.

"What I would say is that we are looking to get reform through. Now whether that is a bigger, broader reform or whether it needs to be narrowed down, we’ll wait and see.

"But we’re very serious about the reform which would lower the donation declarations, that would put a cap on donations, a cap on expenditure, that would lead to more transparency as well. It’s an important part of supporting our democracy.

"We see overseas and we’ve seen people like Clive Palmer here spend over $100 million on a campaign. That’s a distortion of democracy – if one person can spend that much money to try to influence an election and we don’t find out all of that information till much later on.”

The reforms would not start operating until the next term of parliament.

Albanese said he thought the reform would have “overwhelming support” with the public “and I hope that it receives overwhelming support in the Senate as well”.

Podcast E&OE TRANSCRIPT

MICHELLE GRATTAN, HOST: The date for the election isn’t announced yet, but the contestants have been running at full tilt for months. Many voters, however, hard pressed by the cost of living, are just starting to tune in, and their mood is often sour and certainly impatient. The polls at present are showing the election battle is finally balanced, with observers speculating on a hung parliament. But there’s a lot to play out in coming weeks before the result is decided. Today, in our first podcast for 2025, we sit down with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to talk about current issues and his pitch for a second term. Prime Minister, thank you for joining the podcast. Let’s start with the antisemitism wave that we’re seeing. Now, I know that you won’t comment on the recent incident involving the caravan full of explosives, about which, reportedly, you weren’t told initially. But more generally, are you satisfied with the performance of federal and state agencies in dealing with this wave generally, and are you satisfied that your Government and the states are doing everything they can to try to bring this under control?

ANTHONY ALBANESE, PRIME MINISTER: I am satisfied that we are doing everything within our powers, and that every single request by the Australian Federal Police or by state jurisdictions or by the intelligence agencies, including ASIO, is met with one word: yes. So they are being provided with all of the resources and support. My focus is two things. The first focus is on safety. The second is on providing those intelligence and police agencies with support so that people can be rounded up, and I want to see people hunted down. I want to see them jailed.

GRATTAN: This whole wave, though, seems quite extraordinary, to me, at least. Have you any explanation or theory about how this could be happening? So much violence, so many incidents.

PRIME MINISTER: Well, the police have outlined, themselves, some of their views about what the motivation is, and one of those is that some of the perpetrators of these violent acts have been paid to do so. Now, they are engaged in an operation to not just find the perpetrators, but find who’s paying them. Who are the actors behind this? Which is why some of the calls for more of that information to be out there, whilst understandable from one perspective, what you can’t do is undermine an investigation. And I’m about outcomes here, I want to make sure that that the people responsible, not just up front, but behind this, are held to account.

GRATTAN: But are you surprised that we’ve seen this enormous outbreak?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, of course, I was surprised as well by last week the vision of up to 30 men in black gear from head to toe, marching through Adelaide and Adelaide Park – trying to march through – and Adelaide city, to disrupt Australia Day festivities. That’s not who Australia – it’s not what we are. We’re a tolerant, multicultural, harmonious nation, and some of clearly the motivation of some of this is about causing social division. Is about disruption. And it is – it is shocking. It has caused enormous distress in particularly, of course, in the Jewish community, who’ve been targeted. But more broadly, it’s caused distress as well.

GRATTAN: Obviously, over its history, since the 1970s, multiculturalism has come under pressure at times. Do you think it is now seriously under pressure because of what’s happened in the wake of the Middle East conflict, and do you think more action has to be taken by governments, by organisations, by community leaders, to really put more glue in our multiculturalism?

PRIME MINISTER: We can’t take our social cohesion for granted. It needs to be nurtured, it needs to be cherished. That’s why I’ve appointed Peter Khalil as the Special Envoy on Social Cohesion to work with communities to that end. So I think quite clearly with some of the challenges that are there – and this isn’t just an Australian phenomenon. We see this in the United States, the United Kingdom, in other nations as well. We need to make sure that we do what we can to, as you put it, provide that glue that brings us together. I’ve always thought that Australia can be a microcosm for the world that can show people of different faiths, different backgrounds, can come together, living in harmony, strengthened by our diversity. And it certainly is one of the things that I find fantastic about living in Australia, is that diversity that’s there. I’ve just been celebrating the Year of the Snake in the Lunar New Year, with tens of thousands of people in the Chinese community gathered at Box Hill. They’re expecting today, over the day, over 150,000 people to participate there in Melbourne, and that’s a great privilege. It’s one of the great things about being Australian.

GRATTAN: Let’s turn to cost of living, which, of course, will be at the heart of the election battle. We’ve been in a per capita recession for some time now. And you told the Fin Review a day or so ago that Australians will be better off in three years’ time than they are now. How soon do you anticipate we might be out of this per capita recession?

PRIME MINISTER: We can see already from the figures that inflation is down to 2.4 per cent, the headline rate. Underlying down to 3.2 per cent from 3.6 per cent. So it’s been heading in the right direction. It peaked above seven. When we came to office, it had a six in front of it, so it’s almost a third. So that’s part of the equation. The second part, of course, is the inputs, which is people’s wages and real wages have risen four quarters in a row. Unemployment is low, relatively. It’s at 4 per cent and indeed the average unemployment rate during my Government is lower than any government in the last 50 years, and that’s a remarkable achievement given global inflationary pressures. So we want to see living standards rise. We see the purpose of an economy being working for people, not the other way around. And there are positive signs there. If you look at consumer confidence, those figures have been heading in the right direction as well. So I am very hopeful that what we’ve managed to do – I say, it’s like landing a 747 on a helicopter pad – to try to land lower inflation, whilst providing cost of living, relief and support, whilst making sure you don’t have a negative impact in which there’s spike in unemployment. That’s been our task, and the figures show that it has been the right strategy going forward, compared with New Zealand which is in a significant recession. Unemployment has hit double digits amongst many of our competitors, and we have the fastest employment growth, faster than any G7 country.

GRATTAN: So could we get out of this per capita recession this calendar year, do you think?

PRIME MINISTER: Look, things are heading positive, and when you have real wages increasing and you have inflation heading in the right direction down to 2.4 per cent. So the Reserve Bank band that they seek is between two and three, so it’s in the bottom half. Now the Reserve Bank will make independent decisions, but obviously interest rates have a major impact on people’s quality of life as well, and so I am positive that what we have done is to come through some of the hardest economic times that we’ve seen globally, which was a product, in part, of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But also, people can’t underestimate the impact that the tail of COVID, which is still with us, has had.

GRATTAN: So without pre-empting the Reserve Bank, do you think we can expect interest rates will come down in the next few months?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, all of the economic commentators are saying that that is the most likely prediction of markets. It’s not up to me as Prime Minister to tell the independent Reserve Bank what to do, but I’m certain that we’ve created the conditions through, as well, our responsible economic management. Producing two Budget surpluses, the massive turnaround that we have seen, compared with what the March 2022 Budget handed down by the Coalition by Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg, was predicting. That turnaround is around $200 billion. That is a big turnaround, the biggest ever fiscal turnaround, in any term of government.

GRATTAN: I’m sure you’ll have your fingers crossed mid-month when the Bank meets.

PRIME MINISTER: February 18 is the meeting, and I’m certainly conscious of that date.

GRATTAN: Incidentally, in the interview that I referred to, I noticed you said the election date is fluid. That is your position? No final decision on that?

PRIME MINISTER: Yeah, no, we make decisions when we finalise them and I’ll consult. But I’ve always said, I’ve been asked this now for some time. One of the problems with three year terms is they are too short, and this time last year, Peter Dutton was calling for an election to stop tax cuts going forward, it’s important to remember. And then various publications were predicting an election in August. Then it was September, October, etc. I think three years is too short, so we’ll make an assessment at an appropriate time. But Parliament will be sitting next week, as I said last year that it would.

GRATTAN: Maybe you really do want that Budget in March?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, we certainly are working to hand down a budget in March. The ERC will be meeting this week as it met last week, and we’ve done a lot of work, obviously, with the March Budget proposed, a lot of work is done in advance in MYEFO, more so than if it was a May budget. So a lot of work has been done.

GRATTAN: You often say that you don’t want people held back or people left behind. At this point, who is left behind? In other words, who do you see as the most, as the people most needing urgent help?

PRIME MINISTER: One of the issues that brings up, I think, is intergenerational equity. I think that young people feel like they’ve got the rough end of the pineapple compared with previous generations. So something I’m really conscious of, that’s one of the reasons why we’ll cancel 20 per cent of student debt on top of the $3 billion we’ve already cancelled. That’s one of the reasons why we’re concentrating so hard on housing and on making sure that we increase supply. That’s one of the reasons why, as well, I’ve done so much hard work with Jason Clare, not just on early childhood education that we’ve done with Anne Aly, but on school education at the moment, trying to finally deliver on David Gonski’s vision of 14 years ago. We’ve now got six of the states and territories signed up to that. But while also we’re delivering Free TAFE, more than 600,000 Australians, largely young people, have benefited from that, as well as the Universities Accord. So all the way through, we think education is really important. Housing is important and giving people that opportunity.

GRATTAN: So do you want to do more in the way of promises and so on this term for young people? Or do you think you’ve reached the limit of what you can do?

PRIME MINISTER: We’ll have more policies being announced for them and and in other areas as well. I mean Labor will always want to do more to strengthen the economy and for that to create the conditions to do more in education and health and creating opportunity. And what I mean by no one left behind is that during these difficult economic times, we’ve provided substantial income support for people who’ve needed it. We changed the Single Parenting Payment. We’ve increased Rental Assistance by 45 per cent with two consecutive support increases, the first time that’s ever happened. So we’ve done that to target particularly disadvantaged groups. We’re reforming the NDIS to make sure that it’s sustainable in the long term. We’ve got aged care reform to make sure that older Australians get the dignity and respect they deserve in their later years. Now, all of that is designed by making sure that people aren’t left behind. But no one held back is about opportunity as well, seizing the opportunity that’s there from new industries with the shift to net zero, seizing the opportunity to train Australians for those jobs of the future. That is what I mean by those two phrases, and that, I think, is a pretty useful frame I have found for government as well. Are we achieving either of those objectives with what we’re putting forward?

GRATTAN: Now, looking abroad, Donald Trump is set to have a major influence way beyond the United States. What do you think the implications will be for Australia? Firstly, in terms of the economy, do you think will be hit with tariffs? And secondly, in terms of the region, and thirdly, in terms of climate change policy internationally?

PRIME MINISTER: On the former, the direct impact on us, I can say that the first discussion I had with President Trump to congratulate him on his election was very positive. That when it comes to decisions about tariffs, I believe that the world benefits from free trade. We do have a free trade agreement with the United States. The United States has a trade surplus with us, so it is in their interest for that relationship to continue.

GRATTAN: You think they’ll see that?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, we will put our arguments forward very clearly. With regard to the impact of a Trump Administration on the region, part of what we will be saying and doing is there’s a recognition that Australia punches above our weight in this region. We are a significant power when it comes to the Pacific, and we exercise that in a range of ways – soft power, diplomatic power, economic influence, support for infrastructure and programs in the Pacific, but also ASEAN. I hosted last year every ASEAN leader in Melbourne, that was extremely successful. And that relationship with the growing economies in our region, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and more is very important, and we play that role. We’re important alliance partners with the United States, but we’re also important partners in the Quad together with Japan and India in this region. So we play an important role going forward. I think that is very much recognised.

GRATTAN: And you would be stressing that. And what about climate change?

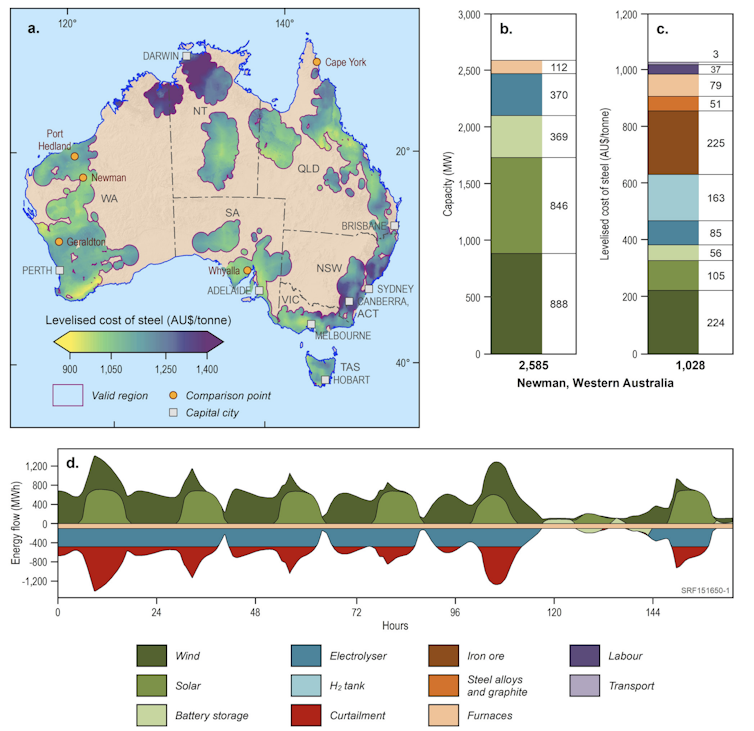

PRIME MINISTER: Climate change – we believe very firmly that climate change action isn’t just about the environment. It’s also about strengthening our economy. That we have an economic advantage by developing green aluminium, green steel, these new industries. So, largely, the impact of the US and their relationship to the Paris Accord shouldn’t be overemphasised, the impact on what we do domestically. And I also think that some of what occurs in the United States – the Inflation Reduction Act – Members of Congress and the Senate, whether they’re Republicans or Democrats, will be, I think, reluctant to unwind some of the support for industry which is there because it’s about jobs in their local constituency, and it’s that same motivation that we have of jobs and where does future economic growth come from. I truly believe that action taken this decade can set Australia up for the many decades ahead.

GRATTAN: Do you have any idea, incidentally, when you might have your first face to face meeting with the new President?

PRIME MINISTER: The President, at this stage, hasn’t had international visitors, bilaterals, and that’s understandable. The Administration is being established. The Quad meeting is expected to take place in the second quarter of this year, perhaps around about June, so perhaps then, if not beforehand. But we will wait and see. We’ll certainly continue to have engagement. And it’s been very positive the engagement that ministers have had, I think the fact that Penny Wong, as our Foreign Minister, was one of the few international guests at the inauguration was a very positive sign.

GRATTAN: Now coming back closer to home, I know you’re pitching for majority government, but are you confident that if the election delivered you minority government, you could still deliver your program effectively? Now you do have, of course, experience in this area from the previous Labor Government.

PRIME MINISTER: I’m confident that we can achieve an ongoing majority government at this election. I think there are seats that we currently hold that we have good prospects in and indeed in recent days, today, I was in Menzies. Yesterday, I was in Deakin. I think there are seats where Labor can win –

GRATTAN: Menzies and Deakin?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, Menzies, absolutely we can win and Deakin, we have the same candidate that we had last time, Mr Gregg. So that that’s an advantage when you have a second crack. In Gabriel Ng in Menzies, he’s an outstanding candidate as well. And on the pendulum with the redistribution it has, I think it’s slightly in our corner, but basically 50/50, but it’s slightly towards us. And we’ll be campaigning hard across seats to retain seats that we currently hold, but to win seats off the Coalition and in a range of areas they have particular problems with sitting or former sitting Liberal members who’ve defected, or National Party members who are running as independents. You have as well, the opportunity for us to succeed in seats that are held in Queensland by the Greens party, and we certainly have fantastic candidates in seats, like Renee Coffey in Griffith is campaigning very hard. As is Rebecca Hack in Ryan and Madonna Jarrett in Brisbane.

GRATTAN: Talking about independents, do you think you could get Fowler back?

PRIME MINISTER: We certainly have a fantastic candidate in Tu Le in Fowler, she’s an accomplished lawyer. She is the daughter of quite prominent people who came to Australia by boat as refugees. She’s articulate, she’s smart, she’s accomplished. She’s from that area. She has lived there her whole life, and she’s having a real crack.

GRATTAN: And you think you can?

PRIME MINISTER: I think we are certainly in with a big opportunity, because it has historically been a Labor seat, and clearly there was backlash last time round by a perception that Kristina Keneally was not from the area. Tu Le is a great candidate, and she’s campaigning very hard.

GRATTAN: The Government this term didn’t introduce what was expected or hoped for, legislation on restricting gambling advertising, and many people were disappointed at that. Do you commit to doing this if you’re re-elected?

PRIME MINISTER: We are going to do more, but we’ve already done a lot. We’ve done more than any government since Federation on problem gambling. The BetStop Register was an important reform, banning credit cards from use, making sure that we get much stronger regulation. And one of the things that has also happened as a result of pressure from the Government as well, there’s been a reduction, a bit of self-regulation, if you like, as well, from some of the betting companies in terms of advertising. We also are very conscious that when it comes to problem gambling, it’s not just about betting on football, indeed, overwhelmingly, it’s poker machines is where most losses occur, with problem gamblers. But there are other forms as well, and so we want to make sure – one of the things we did as well was to change the ads from the benign ‘gamble responsibly’ that didn’t really say anything, to have very direct messages to people who are adults, to say, if you bet you will lose, to make that very clear as well. But we acknowledge that there’s more to do, and we’ll continue –

GRATTAN: And so you’ll do something on the advertising?

PRIME MINISTER: We will continue to consult with stakeholders and continue to take measures.

GRATTAN: Now the Parliament is about to meet for a fortnight, and I just want to ask you about a couple of important pieces of legislation that will go to the Senate. Do you think we will see the passage of the legislation for the changes in political donations and election spending, and how important are these changes?

PRIME MINISTER: I hope so. And Don Farrell, I spoke with today, as I speak to regularly. He is consulting with people across the Parliament to try to get reforms through –

GRATTAN: Is he confident?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, the Parliament, we spoke before about the prospect of getting legislation through. Labor has 25 out of 76 senators. So we need a large group of people, either the Coalition or the minor parties – a whole section of them, not just one or two – to support legislation. What I would say is that we are looking to get reform through now, whether that is a bigger, broader reform, or whether it needs to be narrowed down, we’ll wait and see. But we’re very serious about the reforms, which would lower the donation declaration, that would put a cap on donations, a cap on expenditure that would lead to more transparency as well. It’s an important part of supporting our democracy. We see overseas, and we’ve seen people like Clive Palmer here spend over $100 million on a campaign. That’s a distortion of democracy, if one person can spend that much money to try to influence an election, and we don’t find out all that information until much later on. So I want to see greater transparency. This term we said we would have a NACC – a National Anti-Corruption Commission. We’ve delivered that. It’s up and running. It’s operating, and I would like to see this. It wouldn’t begin, of course, until the next election, because of time factors of where we’re at with the Electoral Commission. But I think this would have overwhelming support, and I hope that it receives overwhelming support in the Senate as well.

GRATTAN: Now what about the nature positive legislation? It’s also listed. But the Western Australian Government, which is facing an election very soon, is very much against this legislation which sets up a new environmental watchdog. Are you – what is your position on this now? You did pull back from the bill late last year.

PRIME MINISTER: Well, I can’t see that it has a path to success. So at this stage, I can say that we won’t be proceeding with it this term. There simply isn’t a majority as there wasn’t last year. The Greens Party, on one hand, have changed their views with a series of demands. They had another one during the week. Said they wouldn’t without linking it to native forestry and linking it to other things. The Liberal Party that, of course, this process began under them. They are the ones who commissioned the Samuel Report that showed that for neither industry or for environmental groups, the current legislation was working. But they have chosen an obstructionist path, which is what they have tended to do on a range of things. So at this point in time, given there is no prospect of it passing, we’ll continue to discuss with stakeholders in the next term, but at this –

GRATTAN: It will remain your policy?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, what we’ve got, of course, it will be, does the Environment and Protection Act need revision from where it was last century? Quite clearly, it does. Everyone says that that’s the case. It’s a matter of working to, in a practical way, a common sense reform that delivers something that supports industry. I want to see faster approvals. We, in fact, have speeded up approvals substantially, under my Government compared with what was there. But we also want proper sustainability as well.

GRATTAN: Now, looking at the polls, you do better with female voters than with male voters. Why do you think your polling with men is lagging, and how will you try and change that?

PRIME MINISTER: We know that this is a reversal of what historically has occurred. You wrote a piece on this, Michelle, that I read just a while ago. I think there’s a range of factors to it. One, I think, is a concern that many women have, that the Coalition don’t represent them. They certainly, if you look at the Parliament, they don’t reflect the general population. My Government is now majority women in the Caucus, and that plays through to a policy focus as well. So the gender pay gap is the lowest it’s ever been. We want to do even more, Paid Parental Leave, Single Parenting Payment, superannuation on Paid Parental Leave, the child care policy and women’s workforce participation. All of these measures are important, I think, for some men, there is the impact of social media is a major impact. One of the things, though, that we will be really campaigning very hard on is the impact on blue collar workers of the Coalition promises to get rid of Same Job, Same Pay. The definition of casual in employment, their plan to essentially go back to wages going backwards, not forwards, and that, I think, will have an impact as well.

GRATTAN: Now you hoped, of course, that the Voice would be your legacy achievement for this term, but that didn’t come to pass. So what would you nominate as your number one achievement?

PRIME MINISTER: Turning around the economy when people were under real pressure on cost of living. If we had followed the path that Peter Dutton’s actions suggest – that is, no tax cuts for every taxpayer, no Energy Bill Relief, no Cheaper Child Care, no Cheaper Medicines, no Free TAFE, you would have seen in a $78 billion deficit rather than what we produced, a $22 billion surplus. Then having those economic circumstances would have meant that you couldn’t do the measures that we wanted to put in place. You would have been under real pressure to do Paid Parental Leave, to do child care reform as we have. Now, we know there is more to do, but I said before the last election that a long term Labor government builds foundations, and one of the things that we’ve done – child care is a good example. I said before the last election, we’d have a change to the child care subsidy. We know that the average family has benefited by around about $2,700 as a result of that subsidy. Now, next term, we’re saying, if you like, phase two is three days guaranteed child care and a billion dollar fund for child care infrastructure. Particularly that we want to link up with schools, so you have that seamless – avoid the double drop off, all of that. And we know that this is good for productivity, workforce participation and population, the three Ps of economic growth. So this is good economic policy, but it’s also good equity policy as well. But it takes time. Had you tried to do all of that measure in one step, I’m sure it would not be successful. So we’re phasing in that reform, as I said, first tranche done. Second tranche committed to in December last year. But we continue to work on reform. Taking climate change seriously. We have turned that around. Not just having a target of 43 per cent but a mechanism to get there, through the Safeguard Mechanism. The Capacity Investment Scheme is about what you need to do, and doing it in partnership with industry, unions and mainstream conservation groups as well, all on one page with that announcement. That’s a significant achievement, given the climate wars that have occurred over a period of time. Now Peter Dutton wants to reconnect them by stopping all of that and going down this nuclear fantasy road. But we have, I think, set up the process with the mechanisms in place to drive that through the economy.

GRATTAN: So when you’ve got these foundations in, can you be more radical in the second term, and more adventurous, if you like, on issues such as tax or other economic reforms or some other front?

PRIME MINISTER: I think what you can do, the job of reform, of course, is never done. And mine has been a busy Government across economic, social and environmental policy, but we do want to do more. But the economic transformation that the transition to net zero represents is a very significant one. Essentially, we’re seeing globally a transition that is as significant as the Industrial Revolution. This is a new shift in the whole way that the economy functions. And connected up with that, of course, is how do we produce new energy that drives the industries for the future? Be it data centres, for example. I met with Microsoft at their headquarters in Sydney just this week. The prospect that’s there for Australia to be a hub throughout the Indo-Pacific Asian region, is enormous. The prospect that we have when – just a couple weeks ago, we were at Tomago in Newcastle in the Hunter for green aluminium – is exciting for Australia. We are positioned better than anywhere else in the world to benefit, in my view, from this transition that’s occurring. We can be a renewable energy superpower that can be about making more things here, the Future Made in Australia agenda is really significant for us, and if we don’t do that, the alternative isn’t standing still and staying the same, because we’ll go backwards. And it’s significant that Peter Dutton, the first word of his slogan, is ‘back’, and that’s exactly right. He’s promising a smaller economy. His energy plan is for 40 per cent less energy use in 2050. That means making less things here, less industry, less jobs. It’s a myopic vision for Australia, making us smaller. I want Australia to be more successful, to be enlarged in our optimism and our vision, and I want to lead a Government that does that, and I believe I’ve got the capacity, by the amazing talents of people in my Ministry. We’ve had to rebuild the public service during this term. Frankly, they were in a spot of bother, I think. They hadn’t been listened to. Cabinet processes been abandoned. My predecessor, appointed to multiple ministries, and the chaos that was ensuing, there weren’t proper Cabinet processes. You had a Cabinet committee with one member – himself. That that sort of dysfunction that occurred needs to never be returned to.

GRATTAN: So just finally, would we see if you are re-elected, any differences in your own style, your own way of governing? Is there anything that you’ve learned that would bring changes in the way you go about things?

PRIME MINISTER: One of the things that my mentor, Tom Uren, who you knew well, used to say to me was ‘you’ve got to learn something new every day, and you’ve got to get better every day.’ Better, not just professionally, but as a person grow. And I believe that I do learn something new every day, and I continue to analyse how things are going. How can we do things better? And of course, you can. One of the things that we’ve done is, as I say, value the public service, that takes time to bring that forward. There were billions of dollars being spent on outsourcing government roles. We had to turn that around. Aged care was in crisis. The NDIS was headed for real issues which would have undermined support for it. We, I think, had government processes that had effectively broken down. Our relations with the world, not just with China, obviously with the $20 billion of disruption to trade, but with the Pacific, our Pacific neighbours, had broken down. We were in the naughty corner when we attended climate change conferences around the world as well. We have rebuilt those relationships internationally, but we’ve rebuilt relationships domestically as well. There are things that we will do.

GRATTAN: What about your own work style, though? Will you make any changes from what you’ve learned over this last two and a half years?

PRIME MINISTER: I make changes as I’m going as well. The idea that you’re just static over a term –

GRATTAN: What sort of changes have you made?

PRIME MINISTER: I think in some of the processes that we’ve established, continue to work on getting better and better in terms of the office. People that –

GRATTAN: Your office, you mean?

PRIME MINISTER: Yeah, the people that we’ve brought in, the way that we engage with the community, the way that we function and make decisions as well is important. I think some of the advice that we get as well. Robodebt had an impact on the public service as well that needs to be addressed. Governments need to function and need to be able to make decisions as well.

GRATTAN: Is it a harder job than you expected? Because, after all, for a long time, you were close to the top job, as it were, in various roles. But have you found it something of a shock when you actually experienced it over these past two and a half years?

PRIME MINISTER: Well, I think preparing for the job, the fact that I’d served as Acting Prime Minister in 2013 and served as Deputy Prime Minister –

GRATTAN: Not the same, though.

PRIME MINISTER: No, it’s not. But also, being Leader of the House and chairing the Parliamentary Business Committee meant you have access and oversight of every single piece of legislation that’s before the Parliament, every single one. And particularly in the minority Parliament, of course, that was more acute. But I think people underestimate the time that is involved. The international conversations that you have to have. Australia has to be represented at the G20, at the Pacific Island Forum, at ASEAN, at the Quad meetings, at APEC.

GRATTAN: You mean the time that the job that takes up?

PRIME MINISTER: Yeah, yeah. And that, though, is an incredible honour and a privilege. I mean, I am enjoying the job each and every day –

GRATTAN: Do you get exhausted, sometimes?

PRIME MINISTER: Oh, of course you do. You’re human. But one of the things I’ve got – you spoke about what I would do differently. I’ve got much better, I’ve always been pretty good, I think, at time management. But I think I’ve got even better than I was as a Minister or Leader of the Opposition, because you have to. So you get better at knowing you have to make a decision. And you also, though – every day when the car drops me off here, we’re speaking here in my Parliament House office, it’s an incredible privilege that I don’t take for granted on any day. Every time I drive through into that courtyard, I feel lifted up and enthused, and the adrenaline kicks in. I think it can keep you going. My staff sometimes say to me, I don’t know how you do it when they see the diary and how busy you can be. But you know, this opportunity to serve and to make a difference to people’s lives is an incredible one, and I feel honoured to have it. I feel humbled that someone who, when I came into this Parliament, and would have been when we first met a long time ago now. You know, I didn’t come here to be Prime Minister with any expectation at all. But I’m here, and I’m very much enjoying it, and I really will be working each and every day as well to make sure that we’re in a position to continue to build in a second term. Not because of wanting to sit in this office, but because of what you can do for people in this office. And I get as well, some fuel in the tank, if you like, by when I’m out and about, like this morning in Box Hill, or last night at a function, people coming up and just saying, “thank you, you did this decision that made a difference to me,” and that to me, is really important.

GRATTAN: Well, there’ll be plenty of adrenaline flowing through you and through Peter Dutton in the weeks to come. Prime Minister, thank you very much for talking with us today.

PRIME MINISTER: Thanks very much, Michelle.

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

%20by%20ecosystem.jpeg?timestamp=1740694094967)

%20by%20ecosystem.jpeg?timestamp=1740694392033)

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

The Government stated it is working to deliver better environmental outcomes for regional NSW and to deliver on its election commitments for recreational fishers who consider the Trout Cod a popular fish for angling.

The Government stated it is working to deliver better environmental outcomes for regional NSW and to deliver on its election commitments for recreational fishers who consider the Trout Cod a popular fish for angling.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet