October 13 - 19, 2019: Issue 424

Cattle Prods And Welfare Cuts: Mounting Threats To Extinction Rebellion Show Demands Are Being Heard, But Ignored

''Our politicians have their heads stuck in the sand over climate change and extinctions - we have the highest rate of them in the world. #ExtinctionRebellion at Manly Beach...''

October 11, 2019

by Piero Moraro, Lecturer in Criminal Justice, Charles Sturt University

Scores of arrests have been made across Australia as the Extinction Rebellion enters its fifth day of protests.

The activists are desperately trying to force the Australian government to take serious and effective action against climate change. And their brand of civil disobedience has caused major inconveniences, from hanging off bridges to locking themselves to gates, vehicles or cement blocks.

But while inconvenient, their protests are still non-violent. This is an important point to stress, as the members of state and federal government peddle the view that they are criminals and anarchists.

In fact, as the movement grows stronger, so do the governments’ attempt to stop it. It shows the Extinction Rebellion’s demands are actually being heard, but at the same time, the drastic responses make it clear policy-makers will still choose to ignore them.

Draconian responses to social protest

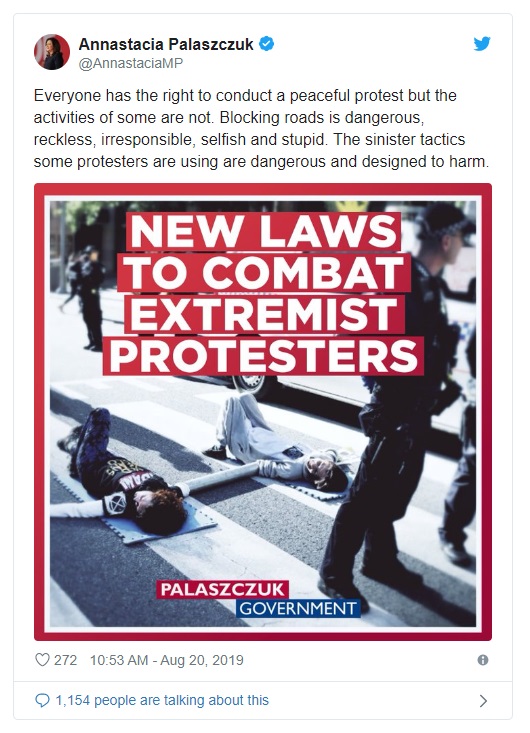

Queensland premier Annastacia Palaszczuk last month used social media to denounce the “sinister” tactics of “stupid” protesters. She claims the current XR protests are “absolutely ridiculous” and are endangering people’s lives.

Her government is now fast-tracking new legislation that would mean possessing a locking device could lead to a jail term of up to two years, or a fine of up to $6,000.

Pauline Hanson has said Queenslanders should use cattle prods on climate change activists, whom she labelled “unwashed idiots”. And a few days ago, Studio 10 host Kerri-Anne Kennerley said motorists should run over XR protesters.

Peter Dutton and Michaelia Cash added fuel to the fire. The Home Affairs minister labelled the XR protesters “fringe-dwellers”, and claimed they should face mandatory jail sentences and welfare cuts.

Senator Cash added: “taxpayers should not be expected to subsidise the protests of others”, since protesting is not an exemption from a welfare recipient’s obligation to look for a job.

What’s more, NSW Police have imposed stringent bail conditions on protesters, traditionally used with members of bikie gangs. The bail conditions prevent them from “going near, or contacting or trying to go near or contact (except through a legal representative) any members of the group Extinction Rebellion”. They’re also not allowed to be within 2.5 kilometres of Sydney’s CBD.

These conditions had the curious result of also preventing defendants from attending court in the Sydney CBD.

Ad hoc laws

Yesterday, former Greens Senator Scott Ludlam had his bail conditions revoked by deputy chief magistrate Jane Mottley, who said they were not necessary given the low seriousness of the offences. It’s expected many more cases will be dismissed on the same ground.

Nevertheless, this use of bail conditions against XR activists raises serious concerns, as citizens are threatened with jail if they insist on partaking in political activism.

The conditions appear to violate basic democratic rights, namely, freedom of opinion, movement and assembly, according to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

But it’s not the first time we see these kinds of ad hoc responses to social protest. Earlier this year, the federal government introduced The Criminal Code Amendment (Agricultural Protection) Bill 2019, specifically targeting the growing animal rights movement in Australia.

Before then, the NSW government introduced the Inclosed Lands, Crimes and Law Enforcement Legislation Amendment (Interference) Bill 2016, targeting anti-mining protests.

And some have expressed concerns that Palaszczuk’s efforts to crack down on civil disobedience are reminiscent of the authoritarian Bjelke-Petersen era, when the QLD government allowed extreme police violence against peaceful protesters.

But it’s worth remembering these XR protests have so far only caused traffic disruptions. While it constitutes a punishable offence, they are fine-only offences at most, as the judge noticed in Ludlam’s case.

Laws already exist to sanction those who breach traffic regulation. With reference to Queensland’s proposed anti-protest legislation, the Human Rights Law Centre noticed:

devices such as sleeping dragons, monopoles and tripods are commonly used in peaceful protest across Australia — our criminal laws already adequately cover their use when they cause major disruption.

The new laws may allow the police to search and arrest anyone who engages in a peaceful protest.

Communicative nature of protest

As I argue in my recent book on civil disobedience, this form of illegal protest has an inherent communicative nature. It seeks to elicit a reply from governments concerning the necessity of changing a law or policy.

From this standpoint, the tough, and seemingly unnecessary, responses to the XR movement are, paradoxically, encouraging. They reveal governments cannot continue to ignore the voices of environmental activists.

On the other hand, the way state and federal governments have chosen to respond show their unwillingness to entertain the activists’ demands.

Besides the mere goal of deterring people from engaging in further protest, governments are also following a familiar strategy involving the use of patronising language, aiming to dismiss XR activists as not worthy of its attention. For instance, the millions of young people who took part in the School Strike for Climate were just “skipping school”.

These are all ways for governments to avoid having to answer for the legitimate questions about its controversial policies and careless attitude about scientists’ warning about rising global temperatures.

As they strive to come up with more demeaning labels for the XR movement, we are left to hope they may eventually apply their creative skills towards finding ways to finally cut Australia’s carbon emissions.

This Article was originally published in The Conversation.