August 15 - 21, 2021: Issue 506

The Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History + The Local Government Act Sections And POM That Protect This Place

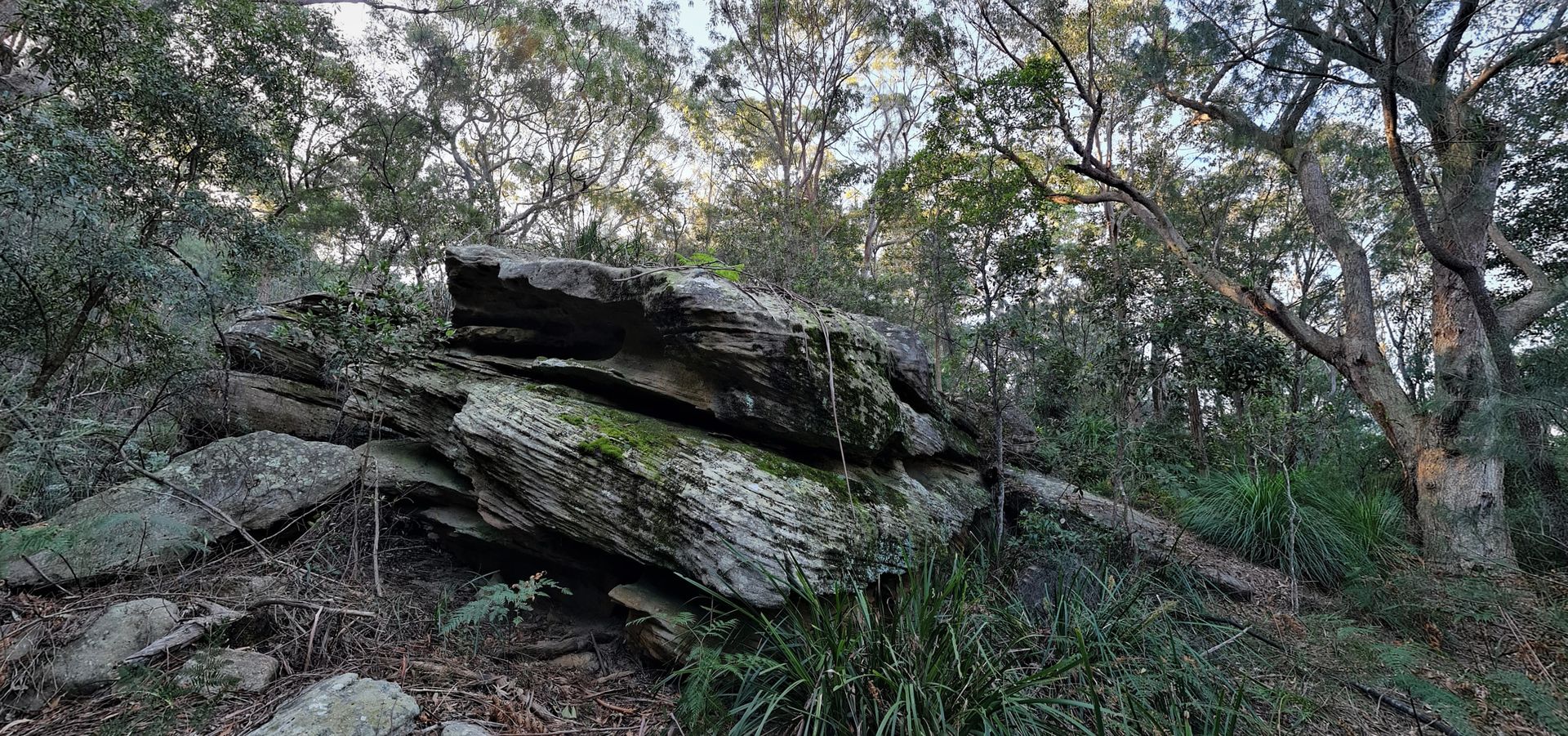

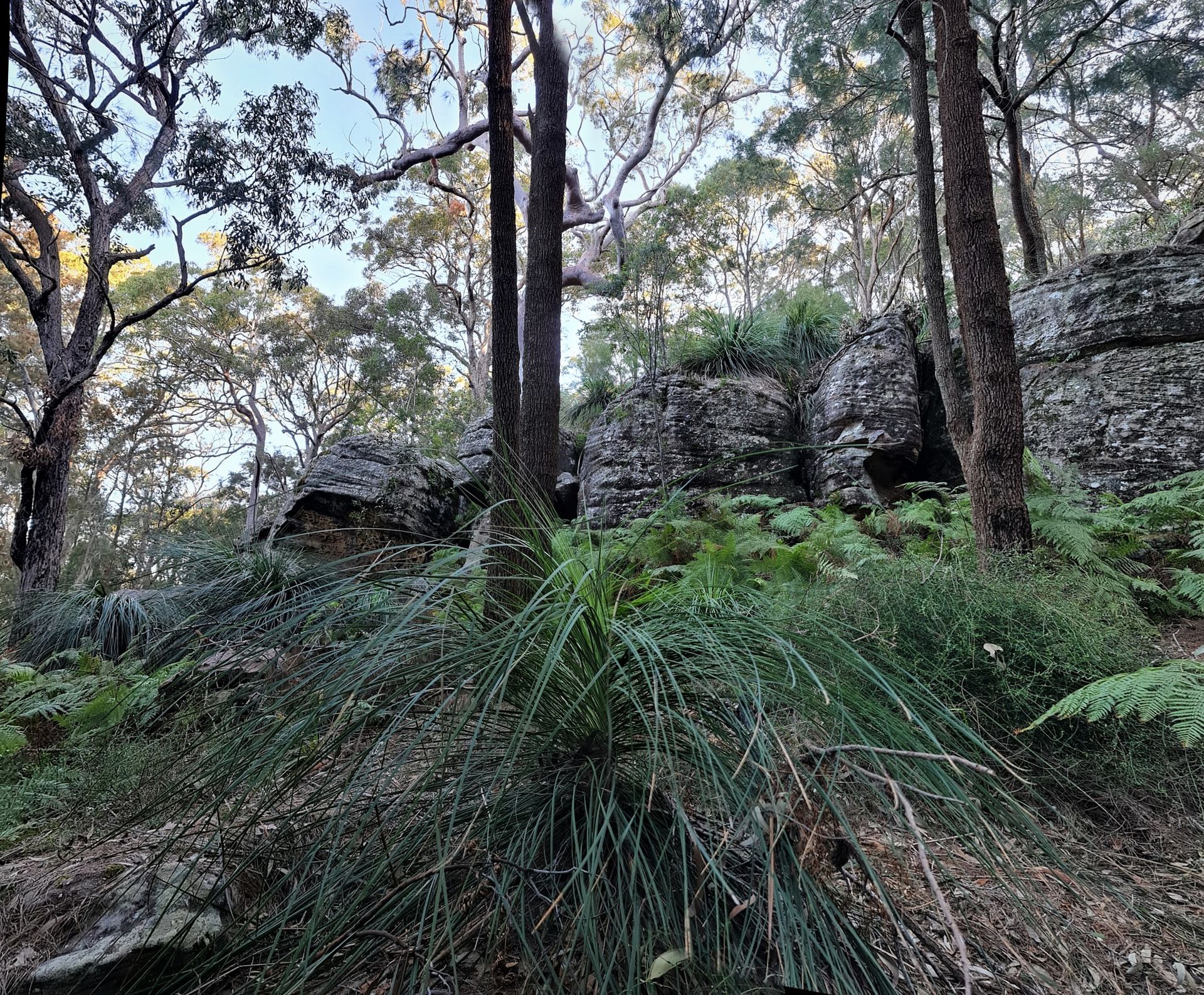

photos by Joe Mills, Winter 2021

Lots 35//11784 and D//337891 (Ingleside Park)

Lot 11 to Lot 16, DP 131704 (former Healesville Estate)

Lot 2 DP 1093237 (former Heydon Estate)

This walk begins by following boardwalks through the Warriewood wetlands. For a while it follows Fern Creek and climbs up the escarpment to Ingleside on steep bush tracks. On the way down the track and steps follow a part of Mullet creek, passing the Irrawong waterfall, before taking boardwalks and paths to finish at Narrabeen. It can be slippery in parts, with creek crossings.

In November 2020 Joe Mills did this loop and shared those images as Issue 472's Pictorial. Joe included parts of the Warriewood Wetlands end as well as an image of the pink boronias found in the upper escarpment area. This time he has again taken photos of the Boronia - with one showing variegated flowers; usually a sign of plant stress or disease or poison. Pittwater Online News has sought input from experts in this field as to why this may be occurring in this location - something has changed between November 2020 and today, the end of Winter 2021.

The Ingleside Chase Reserve covers approximately 70 ha (hectares) within Pittwater. The reserve is largely located within Ingleside but crosses the boundaries of Warriewood in the east and Elanora Heights in the south. The reserve forms part of a significant vegetated link which connects Ku-ring-gai and Garigal National Parks with the Irrawong Reserve, Warriewood Wetlands and Narrabeen Lagoon. This corridor has been recognised as one of the most important habitat areas in the greater Sydney region.

The Ingleside Chase Reserve protects a wide diversity of vegetation communities including a number of communities which are both rare within Pittwater and the region. This includes Coachwood Warm Temperate Rainforest and Sandstone Heath which are both rare within Pittwater, and Ingleside Escarpment Wet Sclerophyll Forest which is rare in a local and regional context. A degraded patch of Swamp Sclerophyll Forest, an Endangered Ecological Community listed under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 occurs in the reserve adjacent to Irrawong Reserve.

The reserve provides known habitat for at least one plant species on the Rare or Threatened Plants (ROTAP) list, nine species which are considered threatened in northern Sydney and eight species considered locally rare and being of significance in the Pittwater area.

Twelve threatened mammals, six bats, two frogs and twelve birds, including critically endangered species, have been recorded or are expected to occur or utilise habitats within the Ingleside Chase Reserve. This is in addition to the entire corridor being recognised as being significant habitat for 207 terrestrial species including 166 birds, 20 mammals, 15 reptiles and 5 frogs.

It's a wildlife nursery and home!

An abundance of Aboriginal heritage exists on the escarpment and surrounding land including many rock carvings depicting people and animals, information relating to hunting and water sources. In addition there are paintings in rock overhangs and other signs of the importance of the area to Aboriginal peoples.

Ingleside Chase Reserve is considered a significant resource to the local community with a range of informal access tracks offering opportunities for passive recreation such as nature walks and bird watching. The reserve also forms a naturally vegetated backdrop to the Warriewood Valley which enhances the leafy character of the Pittwater area.

Ingleside Chase Reserve is also one of the best remaining examples of high quality urban bushland in Sydney. The vast majority of the reserve is in good condition or 'high quality' and requires only minimal maintenance.

A large section of vegetation upslope and to the north west of the reserve is currently functioning as a buffer and it is essential that any future development in this area is undertaken in a sympathetic manner to minimise potential impacts on this reserve. Considering the high ecological value of the land and the potential impacts its’ development will have on the reserve and biodiversity, it was recommended in the Pittwater Council POM, adopted January 2011 that the land be permanently set aside for conservation.

The years of work undertaken to conserve this area for current and future generations may be read of in A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by Angus Gordon and David Palmer.

An overview of this entailed Keeping the biodiversity of the Ingleside escarpment that was initially conserved over approximately 11.9 ha in the central portion of the current reserve at Ingleside Park.

As part of the planning process for the Ingleside and Warriewood urban release areas, a number of environmental studies were conducted including land capability, visual impact and ecology. This research found that the majority of the Ingleside escarpment was physically and ecological constrained and any form of urban development on the escarpment was not recommended [Gondwana Consulting 2005]. In response Pittwater Council sought to protect and conserve the Ingleside escarpment through the acquisition of as much privately owned escarpment bushland as practicable. To achieve this Pittwater Council proposed an environmental levy on rate income to fund the public purchase of such land which the Minister for Local Government subsequently approved on June 20th 2000 with approximately $5M in funds raised over a five year period.

Negotiations by Pittwater Council allowed for the acquisition of approximately 28 ha of the former Healesville Estate on September 6th 2002 following a land exchange for Pittwater Council’s Ingleside Depot. The Healesville Estate section of the Ingleside escarpment constitutes the most northern section of the reserve and consists of open woodland on the upper slopes that transitions into taller forest on the lower slopes and around creeklines. A small section of the Ingleside escarpment totalling 4 ha was acquired from Mater Maria Catholic College in 2005 by Pittwater Council, completing the northern section of the current reserve.

Then negotiations with the State Government and the Uniting Church allowed for the incorporation of a further 27 ha of remnant bushland, including the former Heydon Estate, into the Ingleside Chase Reserve [Ingleside Chase Reserve - Plan of Management, 2011] - Under the Local Government Act, 1993.

Under the Local Government Act 1993, current as at August 15 2021, LGA Section 36J the Core objectives for management of community land categorised as bushland

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as bushland are—

(a) to ensure the ongoing ecological viability of the land by protecting the ecological biodiversity and habitat values of the land, the flora and fauna (including invertebrates, fungi and micro-organisms) of the land and other ecological values of the land, and

(b) to protect the aesthetic, heritage, recreational, educational and scientific values of the land, and

(c) to promote the management of the land in a manner that protects and enhances the values and quality of the land and facilitates public enjoyment of the land, and to implement measures directed to minimising or mitigating any disturbance caused by human intrusion, and

(d) to restore degraded bushland, and

(e) to protect existing landforms such as natural drainage lines, watercourses and foreshores, and

(f) to retain bushland in parcels of a size and configuration that will enable the existing plant and animal communities to survive in the long term, and

(g) to protect bushland as a natural stabiliser of the soil surface.

Section 36K lists the Core objectives for management of community land categorised as wetland as

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as wetland are—

(a) to protect the biodiversity and ecological values of wetlands, with particular reference to their hydrological environment (including water quality and water flow), and to the flora, fauna and habitat values of the wetlands, and

(b) to restore and regenerate degraded wetlands, and

(c) to facilitate community education in relation to wetlands, and the community use of wetlands, without compromising the ecological values of wetlands.

Section 36L states the Core objectives for management of community land categorised as an escarpment

The Core objectives for management of community land categorised as an escarpment are—

(a) to protect any important geological, geomorphological or scenic features of the escarpment, and

(b) to facilitate safe community use and enjoyment of the escarpment.

Section 36M, the Core objectives for management of community land categorised as a watercourse

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as a watercourse are—

(a) to manage watercourses so as to protect the biodiversity and ecological values of the instream environment, particularly in relation to water quality and water flows, and

(b) to manage watercourses so as to protect the riparian environment, particularly in relation to riparian vegetation and habitats and bank stability, and

(c) to restore degraded watercourses, and

(d) to promote community education, and community access to and use of the watercourse, without compromising the other core objectives of the category.

Section 36N states the Core objectives for management of community land categorised as foreshore

The core objectives for management of community land categorised as foreshore are—

(a) to maintain the foreshore as a transition area between the aquatic and the terrestrial environment, and to protect and enhance all functions associated with the foreshore’s role as a transition area, and

(b) to facilitate the ecologically sustainable use of the foreshore, and to mitigate impact on the foreshore by community use.

Under Section 38 Public notice of draft plans of management

(1) A council must give public notice of a draft plan of management.

(2) The period of public exhibition of the draft plan must be not less than 28 days.

(3) The public notice must also specify a period of not less than 42 days after the date on which the draft plan is placed on public exhibition during which submissions may be made to the council.

(4) The council must, in accordance with its notice, publicly exhibit the draft plan together with any other matter which it considers appropriate or necessary to better enable the draft plan and its implications to be understood.

A long way from the objectives of the Municipalities Act of 1858, or even the Local Government (Shires) Act 1905, that divided the State of NSW, exclusive of existing municipalities, into shires for the purpose of local administration. This 1905 Act was quickly followed up by the subsequent Local Government Act 1906 which laid the basic foundations for the way local government operates in NSW today. The Local Government Act 1906 only included the most basic structure of local government for operational simplicity and left detail of the machinery and administrative nature of the regime to later ordinances and regulations. It was designed to allow for maximum flexibility in ensuring that the interests of different regions could be regulated separately and appropriately rather than a ‘one size fits all’ approach.

As can be seen in the Pittwater Roads: Streets Have Your Name history series, it was also about shifting the burden of development of roads and their build cost to access these places to the local shires who in turn, shifted that responsibility and cost to the developers - in whole, no 'contribution' scheme then!

A great local aspect of this 'development of suburban areas' was Warringah Shire Council's policy of requiring, in addition to building roads to lots of land for sale, lots of land as reserves to be set aside, whether on hills or beside bays and beaches, and the great network of connective public pathways that wend over all hills, alongside creeks, beaches and bays. This Council also set about buying the then privately owned beaches access along our coasts, that above the Crown Land marker. These beach resumptions costs, outside the one third granted by state government, they levied on the various 'Ridings' (Pittwater was 'A Riding') through special rates made payable by the residents of those eras. It is solely due to them and this 'policy' and its vision that what is still enjoyed by generations today, and those to come, that these areas have been retained as public owned land in such an excellent way.

This 'contribution' required by the residents and ratepayers of then should not go unmarked - many of the 'land buyers' of then bought here because it was what they could afford; they were not all Macquarie street doctors - so extra shillings and pounds levied would have had a real impact on the food on the table regime. This community spirit in the individual and whole shows up time and time again - if the community wanted a rockpool, the community had to come up with half the cost. If the community wanted a community hall, they had to come up with half the cost. Warringah Shire Council simply was not given the taxpayer funded grants announced by state government and bestowed to build community infrastructure today; they had to take out loans for which another 'special rate variation' was announced and extracted.

In 1919, the legislation of 1906 was repealed and new measures were set up in the Local Government Act 1919. Major features of the 1906 Act were retained, but the 1919 extended the electoral franchise, introduced compulsory voting and encouraged amalgamations so that municipalities were fewer in number and larger in area. The Act also removed the requirement to have the Governor approve many measures passed by councils.

In 1973, the ''Committee of Inquiry into Local Government Areas and Administration'', the 'Barnett Committee', reviewed local government. This Committee found that a number of council areas (at the time, there were 233 in NSW) were too small and the result was duplication of services and poor asset management. Despite the findings of this Committee, a complete overhaul of local government did not take place.

By the end of the 20th century, it was apparent that the Local Government Act 1919 was no longer adequate for the demands of 20th century local governance. Councils had evolved from being more than just providers of basic amenities to central players in community life and public expectations about the functions of local government had shifted. A comprehensive review of the 1919 Act commenced with the release of a white paper in 1990. The white paper sought to lay new foundations for local government in New South Wales. It required that the proposed new legislation be designed to do three things:

- To work effectively for small, rural councils as well as for large, urban councils and for those in between. The legislation should not be predicated on the performance of the lowest common denominator of councils. It should allow all councils to perform to the best of their abilities.

- This Act should create mechanisms for appropriate balances to be struck between State and local responsibility and accountability and be capable of accommodating changes in emphasis without complex amendments.

- It also sought to articulate in words to allow councils to be free to get on with the business of running their operations with minimal intervention, and with accountability to the local electorate.

The process that began in August 1991, under the Fahey government, seeking public input, resulted in the Local Government Act 1993. Although this Act has been the subject of numerous amendments, the core features have been largely untouched and guided the work of Pittwater Council in articulating a Plan of Management for this beautiful place, with State Government being the partnership custodians along with the Federal Government.

All residents are the on the ground custodians of course - and guardians of this Keep; the plants and wildlife whose home we visit through the notion of this being part of 'our backyard'.

Go placidly amid this place.

This week, a stroll amid the green cathedrals and lichen patterned escarpment of this place 10 years after this POM was enshrined in Pittwater.