References, Notes And Extras

Also available:

LAWSON

THE MAN AND HIS COUNTRY

By T. D. Mutch, M.L.A.

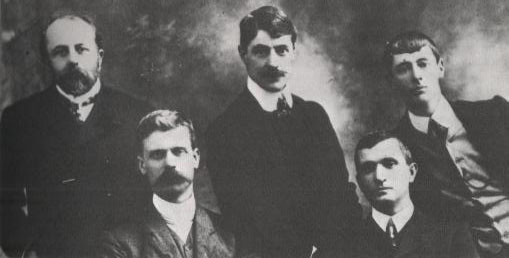

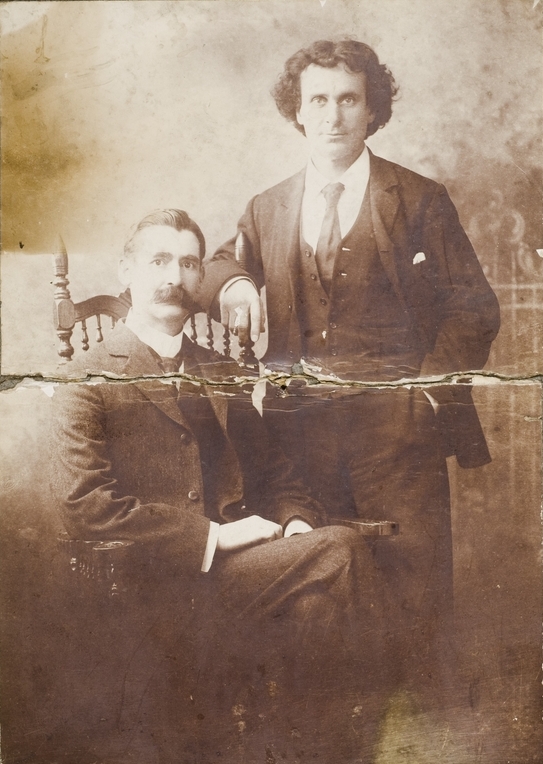

ONE day in nineteen hundred and— was it two?. ("Damn the date," as he used to write sometimes at the head of his letters), a tall, lean, dark man came to the counter at the old "Worker" office in Kent Street, Sydney, stood, smiled, saluted (recognising in me a new employee), and then impulsively came round the counter, placed his hands on my shoulders, looked long with the deepest eyes I have seen in a man, and said, "You'll do." That was my introduction to Henry Lawson. I was a boy then. He left me wondering why or what or how I would do, and he never told me, but you will allow me to cherish the thought that on that day he enrolled me in the list of his friends. Fifteen years after — 1917 — I stood for Parliament, and Henry, who was then at Leeton — although he disliked politicians, a dislike arising out of a Governmental injustice done to his mother, who had invented a patent mail-bag fastener, and was robbed of the fruits of her labour— wrote a letter to the electors of Botany, wherein he said: "But he has carried his swag with me, and was, and is, the straightest mate I ever had; and made him smoke a pipe — and once got two medium beers into him consecutively. It took me three years to do these things, and now I reckon I ought to have a say in his affairs...."

Back To The Bush

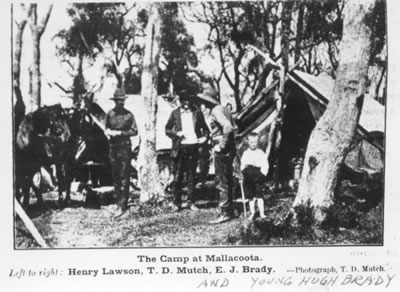

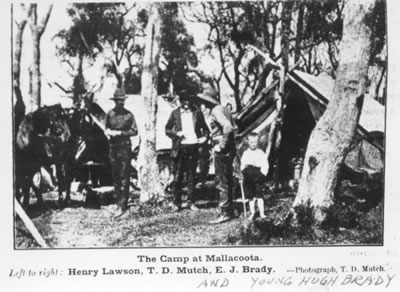

That letter is probably the most unique piece of election literature ever published in Australia, but is too long to be reprinted here. But, long before that, in 1910, a group of his friends gathered together, and decided that Henry should go back to the bush again. We wanted to get him away from the city. We wanted him to rekindle the fire that burned then but fitfully, and with "less flame than ashes." And always Lawson wanted someone to take charge of his affairs. The principal members of that committee were (the late) Bertram Stevens, J Le Gay Brereton, Norman Lilley, Roderic Quinn, J. S. Ryan ("Narranghi Boori"), Fred Brown, Bernard Shaw, Hector Lamond (now M.H.R.), and myself. We arranged for him to go to two or three stations, hoping he would write another "While the Billy Boils", or another "On the Track and Over the Sliprails." but always, at the last moment, he disappointed us. For some time I had been corresponding with E. J. Brady, then, as now, camped at Mallacoota, Victoria, fifteen miles south of Cape Howe, and probably the most beautiful place in Australia. Brady had often invited me to go down and camp there awhile. A happy idea came into my head (a somewhat rare occurrence). I put it to Henry, and he agreed to come away with me. Real Mateship And so, on Friday, February. 25, 1910, I shanghaied him on to the s.s. "Sydney," and at 7 p.m. or thereabouts he and I were standing at the bow as the vessel dipped and ploughed through Sydney Heads and turned on her south-ward course. Somewhat seedy, he said, "I think I'll turn in.” The good ship sailed on Friday, with thirteen men aboard." I can take a hint, and made him as comfortable as anyone can make anyone who wants to be seasick and can't. At Eden, we put up at the Commercial Hotel. Henry promptly made friends with Cooper, who kept it, but I had got in early; he had to drink lemonade, and he enjoyed the joke. Shortly after, I missed him, but I had been to the other hotel, too, and he had to have a second lemonade. I met him half-way up the. street; he put out his arm, more seriously this time, and shook hands without saying a word. From that on everything was in order. Brady met us at Merrimingo, on the Genoa River, with a pulling boat, and insisted on rowing all the way.

We camped with Brady at Mallacoota — swam, fished, shot ducks, rabbits and jam tins. We ate schnapper and wild duck until we 'tired of it, so one day We decided to walk to New South Wales. Brady couldn't come— he was finishing some work — so we rolled our swags, filled our pipes and tucker bags, and set out for Gabo and Cape Howe.

While The Billy Boils '

On that trip, I think I got close to Lawson's heart. He was keen on camping, insisted on rigging the tent, making the fire, and calling baking-powder "saleratus" (after Bret Harte). We had an argument about that, be cause lie. spilt the soda and spoiled the johnny cakes, and blamed ' me. But he forgave me when I shot, and told him I would show him, a brand of snake he had never seen before. Lawson's sense of humour was his personal saving grace. I can remember him building a fire. He had his own ideas about it, and would tolerate no interference. Six years afterwards, I made him wild by telling him that' :he ought to take lessons in making a fire from the actors who produced "While the Billy ' Boils" at the Theatre Royal. They had in the prologue two bushmen boiling a billy; suspended under a cross-piece between two forked sticks. He reckoned the play would' be ruined, because every bushman who went to the theatre would laugh at -that fire. Well, we built our camp at Cape Howe from wreckage and the bones of a stranded whale. When night descended we coiled up on our mattresses of sand, "lulled b. the ocean's rune and wild birds' song." As a man will under those conditions, I woke once or twice in the night. Lawson was standing with his back to the fire, making passes with a pannikin of- tea and a johnny-cake sandwich. Before dawn, we were awakened by Venus, low in the sky, blazing brightly through the open tent door'. ' "Do You Mind The Tent?' ' Oh that lonely trip, Lawson revealed himself to me, and I to him.

Last year, in some verses written to me, and published in "Aussie," he recalled; it. - Do you mind the tent and. camp-fire in the moonlight by Cape Howe? Do you ever pause and ponder were we happier then than now? Yes, of course, we were, 'Twas only one new shore and. one new sea, Marked to meet us and to pass us as THESE times were marked to be. We had both had bitter boyhoods with no tender light or touch ; And you told me half your story— I had lived the rest, 'Tom Mutch, ' Yes, I mind the tent and camp-fire. I mind, too, his story — the first fifteen years in the Roaring Days on Pipeclay; Gulgong, Home Rule; his mother, Louisa Lawson— he called her "the Chieftainess"; his -. father, Peter Hertzberg Larsen worked with father in the bush, At splitting rails and palings, He never was unkind to me, although he had his failings. He left a tidy sum to me, But I'd give all the. Money to hear him say, 'Will you get up? ' And boil the billy, Sonny?"

His sister, Annetta (he called, her Henrietta sometimes), whose death inspired his mother to write her first published lines; his sister, Gertrude, his brothers, Peter arid Charlie; his old home at' the foot of Golden Gully — the drought and the "poorer" that drove his father from it; house building and painting at Mount Victorian—where his father died; his struggles In the city in the eighties — the haggard- group out side the "Herald" office at 4. o'clock' in the morning, striking matches to scan the "Wanted" columns; his excitement when his first verse was published; the guinea he got for "Faces, in the. Street"; his job on the Brisbane "Boomerang" (You'll read his story in "The Cambaroora Star"), his trip to Bourke— he "picked up", at Toorale shearing shed, and humped his drum to Hungerford ; "Mitchell" — there was a man named Mitchell, but the character, in his books covers many men;, his first book, "Short Stories in Prose and: Verse," published by his mother, price one shilling (he was very excited when I told him I had a copy; it was printed at the "Dawn"; office— which his mother founded and ran for 20 years — and on the way to the binders the best part of the edition was blown- out of the cart into -York Street, which had just been watered, and only 300 copies were saved); his trip to New Zealand, where his son, Jim, was . born. Yes, I mind the tent and camp-fire, and I wish I could remember it all. Back to Boyhood And then , there was the time (1914) when, he went with me to revisit " the scenes of his boyhood at Eurunderee, little changed in the passage of years: The creek, that I can ne'er , forget, Its destiny fulfils; . The glow of sunrise purples yet, Along, the Mudgee hills; The flats and sidings seem to be ' Unchanged by "Mudgee town. And with the same old song and sigh The Cudgegong goes down. We wandered over the mullock heaps in Golden Gully, discovered by Henry Hill and John Wurth, who were stripping wattle and who, dipping a billy in a water-hole, noticed the yellow glint of gold in the red clay. They stripped no more bark for many a day. This discovery attracted Pater Larsen, a miner-carpenter, who had been working on the goldfields in Victoria, and Henry Albury, a sawyer-bushman from Guntawang. And Peter met Henry's daughter, Louisa— he was about 20 years older than she — married her, and, with that fickleness characteristic of the alluvial diggers in the early days, took her to the new rush at the Weddin Mountains, Grenfell, where, in a tent, Henry was born. What Should Be Done? He was christened. Henry Archibald, not Hertzberg, Larsen. It was In tended to call him Hertzberg, after his father, but the clergyman made a mistake, and his mother let it go at that. Back again, later,by Gulgong, when Gulgong "broke out," and then, after many wanderings, to settle down in a home his father had built at Eurunderee."

Well, I went over all that ground with Lawson; went over Log Paddock; Ross Farm, Buckholt's Gate, Pipeclay, Home, Rule (When he revisited the old dilapidated town, he scratched his head and said, "They ought to have given it to Ireland., long ago."), Reedy River, Mount Buckaroo and. all the rest of them- — immortalised in his best work. I knew him twenty years, lived with him in bush and .town, and in those years spent as much time with', him as any other man has ever, done— and now I reckon I ought to have a say in his affairs. And what I have to say is this:

We want no sham nor shoddy biography of the greatest literary .genius Australia has produced. We want no half lies and legends about him. Most of those who knew Lawson still live; what they know can, and should, be written now. If the stories told in the coaches as we followed Henry to his grave could be gathered into a volume we'd have a more truthful story of Lawson, the man, than all the literary rubbish yet to be written by men who never saw the bottom of a long beer with him. What I would ask is that the Mitchell Library should acquire, by gift or purchase, all the Lawsonia available — notes, letters, manuscripts, unpublished and unrevised reminiscences written by those who know, so that at a suitable time Lawson's relatives, friends, and old mates may meet together and decide upon his biographer. This much should be done for Lawson's and Australia's sake. What do you say? LAWSON (1922, September 16). Smith's Weekly (Sydney, NSW : 1919 - 1950), p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article234281754

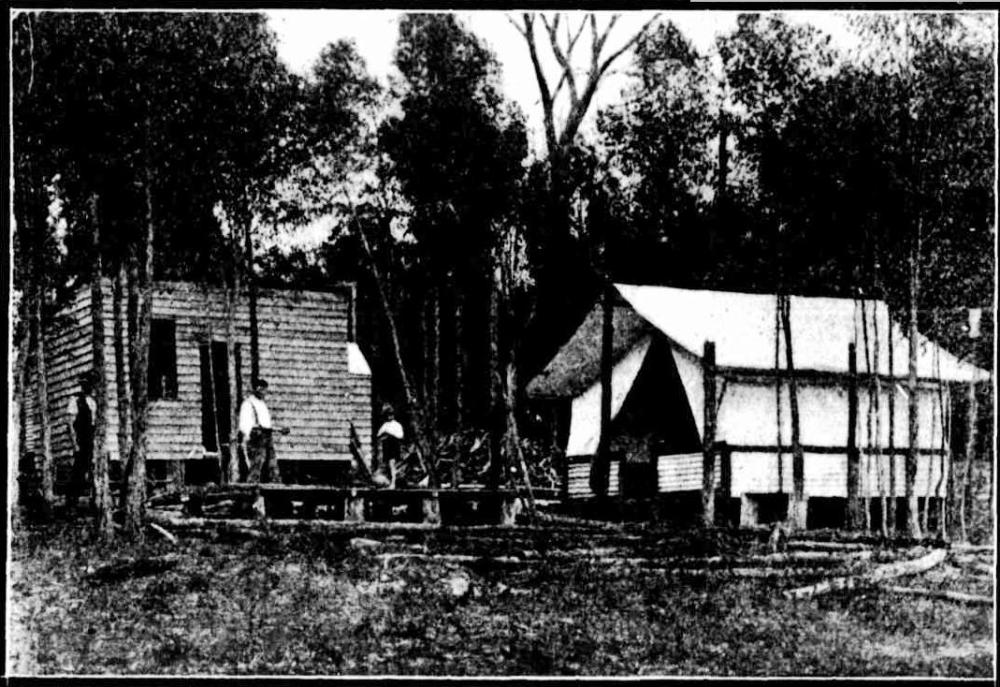

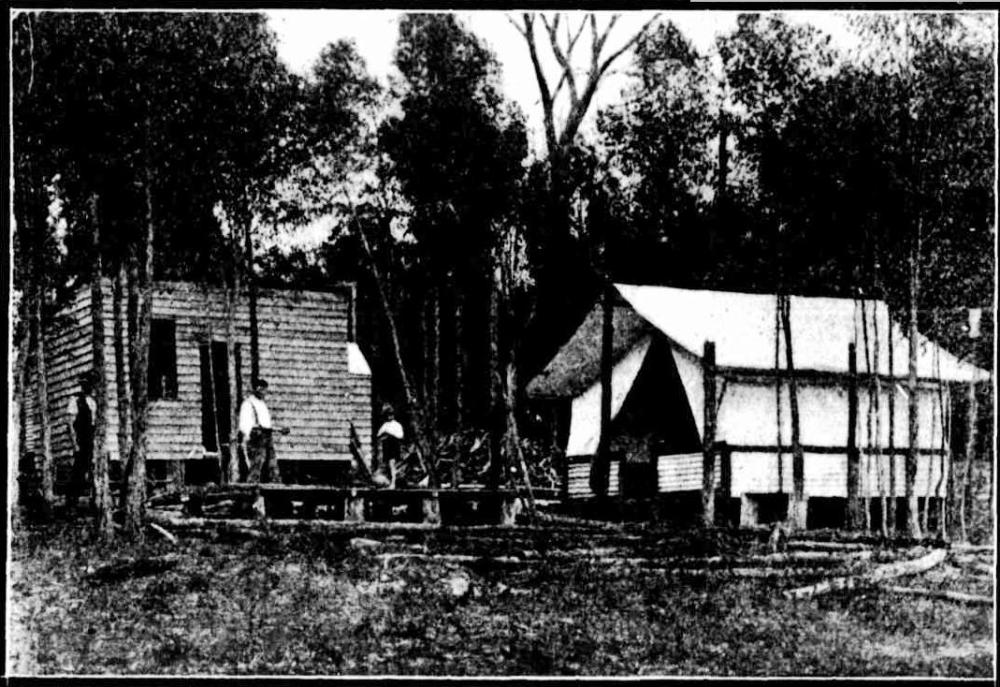

Practical Poetry. E. J. Grady building his home at Mallacoota West. THE WITCHERY OF MALLACOOTA. (1919, March 26). Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article159656523

Mallacoota Bar

Henry Lawson, 1910

Curve of beaches like a horse-shoe, with a glimpse of grazing stock,

To the left the Gabo Lighthouse, to the right the Bastion Rock;

Upper Lake where no one dwelleth — scenery like Italy,

Lower Lake of seven islets and six houses near the sea;

'Twixt the lake and sea a sandbank, where the shifting channels are,

And a break where white-capped rollers bow to Mallacoota Bar.

Gabo, of the reddist granite, cut off from the mainland now —

"Gabo", nearest that the black tongue ever could get round "Cape Howe";

Gabo Island, name suggestive of a wild cape far away,

And a morning gale by sunlight, or a sea and sky of grey;

Gabo, where cold chiselled letters on the obelisk record

How the Monumental City sank with forty souls on board.

To the west the lonely forests, on the levels dense and dark

Native apple tree and bloodwood, wattle, box, and stringybark;

Land of tree-marked tracks and hunters — to their glory or their shame —

For a law makes Mallacoota sanctuary for native game;

To the east the rugged Howe Range, running down without a scar

To the mighty moving sandhills — close to Mallacoota Bar.

And the folk are like their fathers — bushmen-sailors, fishermen —

And they live on fish and tan-bark, with a tourist now and then;

And of hunting? Well, I know not. And what matter if we know

That they did a bit o' smugglin' or o' wreckin' years ago?

For I love these kindly people, and 'twill give my heart a jar

When I see the figures fading on the sandbank by the bar.

There's the old grey house of hardwood that seems built for mighty floods,

With the broad thick slabs laid lengthwise 'twixt the great round tree-trunk studs

That are slotted to receive them - and with shingles six foot long!

There's the house of hand-dressed timber that is nearly half as strong,

There's the rather modern cottage — but, as far as one can see

Everything in Mallacoota is as clean as it can be.

There are pictures in the parlour for three generations back:

There are Grandfather and Granny, there are Syd, and Dave, and Jack;

There is father, that is mother, one each side the mantel hung,

And the girls, and bridal parties - mother, too, when she was young;

That is all. Is that sufficient? 'Tis for yourself to decide —

And the girls ride after cattle, and they always ride astride.

All is blue and gold this morning — green and gold and "Bar all right",

And three blurred sticks under Gabo to the sunlight show the white,

Bringing groceries from Eden, bringing all that we require —

Bringing flour and tea and sugar, roofing iron, and barbed wire,

Copper nails, and small inventions in machinery from afar,

And the little fleet of cutters run for Mallacoota Bar.

And we see the green, transparent light show through the heaving brine —

Waiting with two oars stuck upright on the sand "to give 'em line".

Comes the S.E.A. and, rising, pauses, swan-like, half in doubt,

While her skipper from the ratlines spies the bar and goes about;

"Now she comes," and "now she's coming," and, ere we know where we are,

She is snug beside the sandbank inside Mallacoota Bar.

Warren brings the water with him on the cutter Clara next

(When he doesn't, then his language speaks a sinful spirit vext);

Next the little lugger Lightning darts and misses, grounds and floats,

Finds the channel with a flutter of her draggled petticoats,

Snuggles up beside the Clara, clattering down her little spar,

Like a naughty drab that scrambles over Mallacoota Bar.

But the days are not all sunny — there are anxious times on decks,

When the cutters run for shelter to the graves of ancient wrecks,

Round "the Cape," or under Gabo, Tamboon, or Disaster Bay,

For they won't insure the hulls that cross the 'Coota Bar to-day.

But the elders of the people sadly think in days like these

Of the days when strange things happened to Ike Warren's enemies;

In the days of border duties there was glory to his name,

Who is well liked — and mistrusted — from Green Cape to Cunninghame,

Twenty years by stormy "shelters", where the festive porpoise frisks,

Sailin' out of Mallacoota, buildin' trade, an' takin' risks.

Risks from Acts of God — and monarchs — risks that were (and maybe are)

Altogether unconnected with the weather or the bar;

Wrecks were left where it was lonely; things would float, and things would strand —

Out of sight of Custom Houses, out of sight of sea or land —

To be found — or drift convenient under light of moon and star —

For the most erratic currents ran by Mallacoota Bar.

No, the Bar's not always playful, nor the weather always clear,

And the little Orme with six men has been overdue a year;

Oh the Gippsland Lakes are kindly, and the Gippsland people good,

And the widows and the orphans never shall want clothes nor food;

But the Government are fossils, slow to mend and sure to mar,

And the widows and the orphans blame the Mallacoota Bar.

Half a mile, or rather more, from Captain's Point and Brady's Camp,

Backed by rotten "native apple trees" and coast scrub, dark and damp,

With a garden filled with thistles — haunted on the brightest day —

Stands a little match-board cottage, empty, going to decay

(Like they build in western places — towns that end in 'gar and 'dar),

With its two black, sightless windows turned to Mallacoota Bar.

There's a little cliff before it, with a level verge and straight,

Topped by sunny grass and shady, and a rustic fence and gate,

Framed by trees that frame "the Entrance", where the white-capped rollers pour

'Tis a picture for an artist from the closed-up cottage door;

From a sandbank by the "landing", looking back, the poet sees

How one broken window's hidden by a handkerchief of trees.

It may be a bit o' wreckin' or of smugglin' you'd prefer,

But I write of young Lin Lawson and of Captain Mortimer;

There the Captain built his cottage, fitting it with everything

In the days when roofing iron was a costly thing to bring.

The brick chimney came as ballast, and he laid the hearth with pride,

And, when all was finished neatly, there the Captain brought his bride.

Trading out of Mallacoota — there he bore an honoured name —

Taking wattle bark to Eden, taking fish to Cunninghame,

He would venture out in weather when the others dared not go,

Bring flour and tea and sugar when the Lakes' supply was low;

When the back country was flooded, and the tracks were worse than bad,

Captain Mortimer and Warren were the only hopes they had.

Mortimer was two years married, though he didn't think it two,

When he sailed for Eden taking young Lin Lawson for a crew;

Young Lin Lawson — sailor-bushman, bushman-sailor like the rest

On the Lakes. They would be new to my own bushmen of the west.

Ah, those careless sailor-bushmen seem endowed with pluck sublime,

For they can't imagine danger - when it comes they haven't time.

One I know who trusts the devil, one I know who trusts the Lord,

With the hatches on and battened, and the dinghy hauled on board;

Both have sailed long years in safety where the Green Cape boomers break

In such boxes as you'd scarcely trust your wife in on a lake.

It would set you dumbly praying, if a passenger you be,

Just to hear Ike Warren cursing out of Gabo in a sea.

Captain Mortimer (the Em'ly) whistling some old Scottish tune,

Sailed again for Mallacoota on an autumn afternoon,

Rather later than was usual. He had been a deep-sea tar,

And the skippers take their chances down by Mallacoota Bar.

He was warned about the weather, but he always stood alone,

So the Captain sailed from Eden to an Eden of his own.

And the dread nor'-easter struck him, somewhere off Cape Howe, they say,

And he ran for under Gabo, but let that be as it may;

'Twas a wild dark night for autumn, and it blew as it can blow;

There's a rock above the Entrance, and the Bastion Rock below,

And they found the Em'ly's dinghy, and some decking and a spar

Some days later, on the sandbank, outside the Mallacoota Bar.

He had brought a little brother from a southern town to stay,

As a comfort to his young wife when the Em'ly was away;

All that day they watched and waited, all that day they watched in vain,

For a small white sail off Gabo that would never gleam again;

All night long, white-faced and staring, she who was the sailor's star

Watched the hellish phosphorescence leap on Mallacoota Bar.

And next day a strange thing happened. Strange! It cannot be denied:

For they saw a black speck tossing through the Entrance on the tide,

Drifting in between the sandbanks, and it drifted sure as fate,

Till it stranded on the shingle just below the rustic gate;

And the wife ran down and seized it — it was Hope's death sign to her —

'Twas her husband's cap — a cloth cap worn by Captain Mortimer.

She is dead maybe, or married, there seemed nothing then on earth,

So they bought her goods and chattels for much more than they were worth,

And they drove her round to Eden, to go home to Castlemaine.

And the driver says he wouldn't like to have that job again.

And the sight for days thereafter that brought pain to all and each

Was, each tide, Lin Lawson's father riding up and down the beach.

There's the Howe Range, steep and rugged, running down to granite red,

There's sunny slopes and shady, where the fishing nets are spread;

There are channel posts and net poles by the sea-weed thick and strong,

Where the silly shags sit watching, watching nothing all day long;

There's the story of a cottage, growing ever faint and far,

With its two black windows watching, watching Mallacoota Bar.

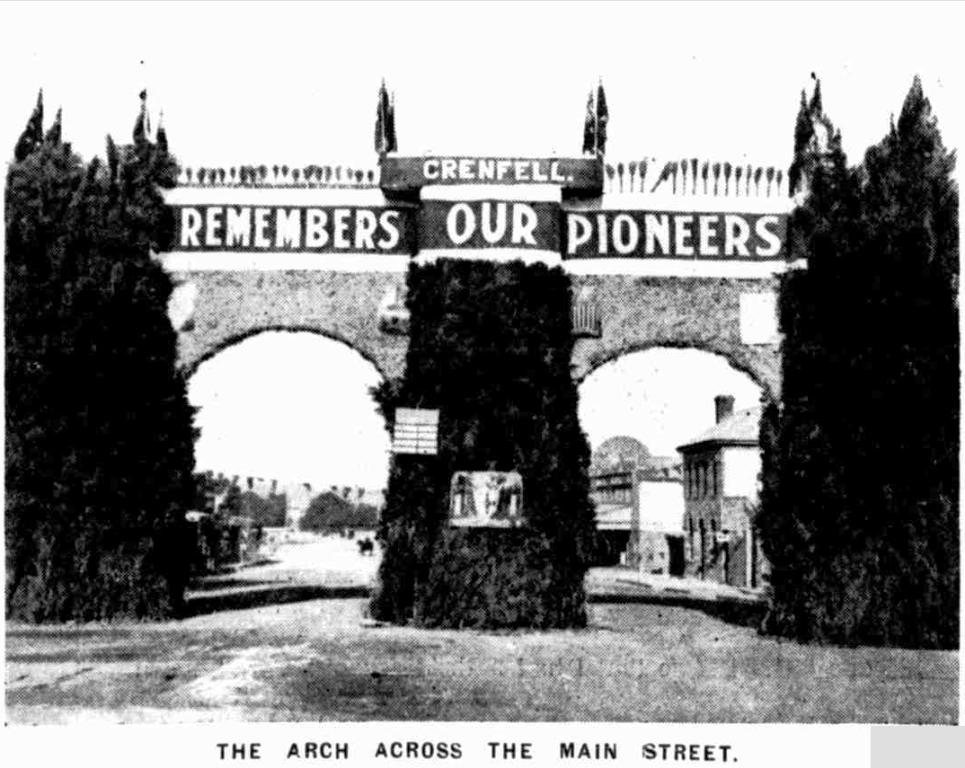

HENRY LAWSON MEMORIAL. Obelisk Unveiled.

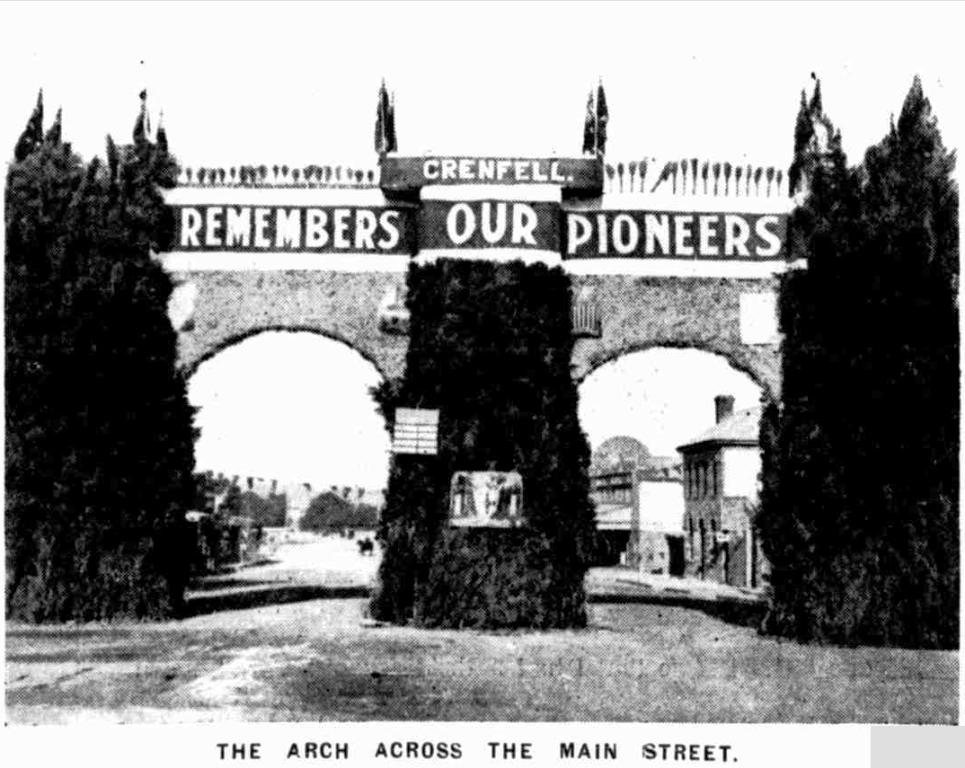

GRENFELL, (N.S.W.), Friday. — The unveiling of a memorial to the late Henry Lawson, erected on the spot where he was born, 57 years ago, was performed before a very large gathering of people, including 400 school children. Mr. Grimm, M.L.A., who unveiled the memorial, said that he had been acquainted with the poet at the age of 17. He asked the school children to learn Lawson's poems because they were Australia's history, the history of the bush. Mr. Grimm quoted poem after poem. Great cheering fol-lowed the unveiling, the band played "Home, Sweet Home," and a trumpeter sounded the "Last Post."

Mrs. Lawson, widow of the poet, and Miss Lawson, daughter, thanked the Grenfell folk of their kindness. Old residents who knew Henry Lawson's father were introduced to Mrs. Lawson. Five gum trees were planted around the obelisk which is 14ft. 6in. in height, and 2,000 photographs of Henry Lawson were distributed.

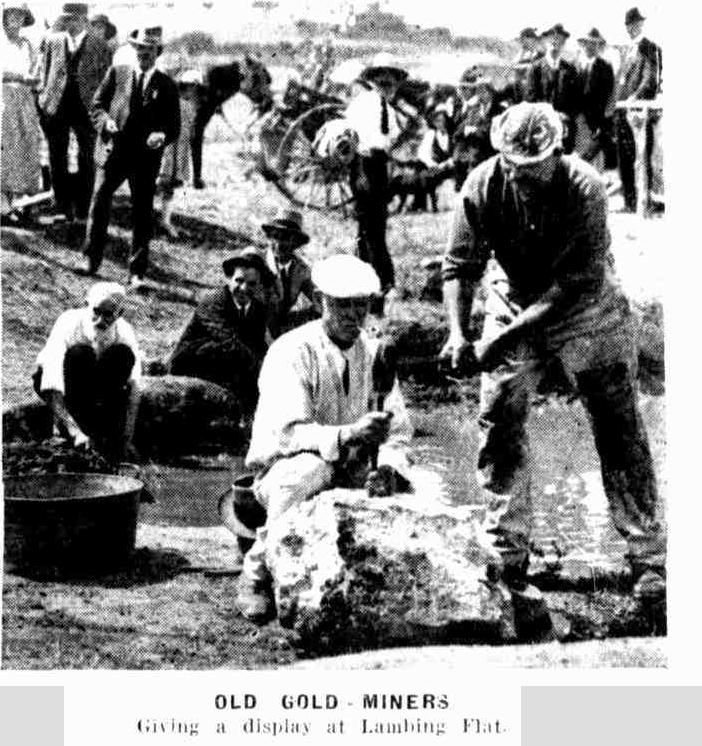

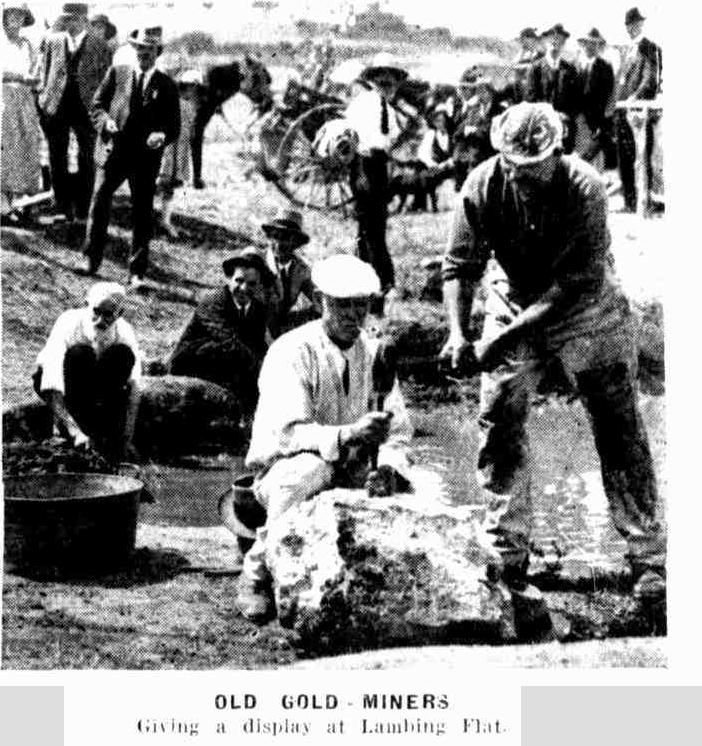

The miners' display which followed was highly interesting. Shafts were sunk and "wash dirt" obtained. The white prospectors flag was changed to the reg flag of gold, and 50 miners scrambled to "peg out," just as the rushers did 60 years ago. Dishes and cradles were worked, and the results showed a reef, which was uncovered and specimens "dollied." Old miners revelled in the work. HENRY LAWSON MEMORIAL. (1924, March 22). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), p. 30. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1907273

THE HENRY LAWSON MEMORIAL

Which was unveiled in the presence of a large gathering, including the poet's wife (right) and daughter (left of monument). "Back to Grenfell":

Back to Grenfell - A Week of Celebrations (1924, March 26). Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), p. 16. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article166151284

LAWSON'S BIRTH

Sister Writes History DIGGERS DAYS

Over half a century ago, a tent was pitched at Grenfell, and in it Henry Lawson was born. It is "Back to Grenfell" Week, and today a splendid obelisk on the site of the little camp will be unveiled to mark the poet's birthplace. Lawson's sister Gertrude (Mrs. O'Connor) wrote the following narrative of her brother's ancestry and of his birth. Three years ago she could not read or write, but set out to learn so that she may be able to record all the circumstances relating to the poet's life.

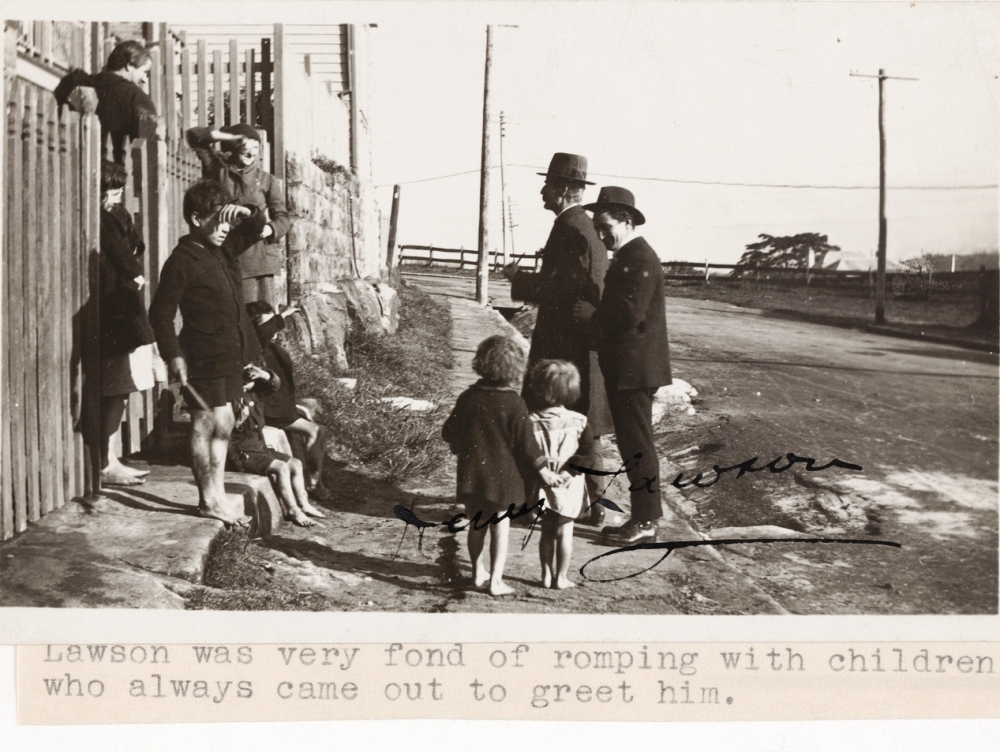

My brother loved Australia; he loved its people; but he loved its bush people best. He loved its little children. He saw Australia's destiny in each little face, and furthermore, he had confidence in them. Mateship was ever the theme of his Verse and his prose. Mateship he ever endeavored to inculcate into the hearts of his readers. It was his second nature. Indelibly It was stamped upon him prenatally by the girl-mother, who was the one woman among 7000 gold diggers at Grenfell. She was the first woman of that rush. The men were a motley throng from the four corners of the earth. There was no social law recognised there — only the pledge of mateship. To them Henry's mother was sacred.

MATES FROM NORWAY

Henry Lawson was the son of one of four lifelong mates. They sailed together as boys from Norway — shipmates — and braved the early gold rushes as digger mates. They were William Henry Slee, Hermin Jansen, Peter Peterson, arid Peter Lawson. Peter Lawson was destined for the sea. His father conducted a school of navigation in Norway. His three eldest sons were sea captains, and young Peter, after his education, was sent on his first long sea voyage to Australia.

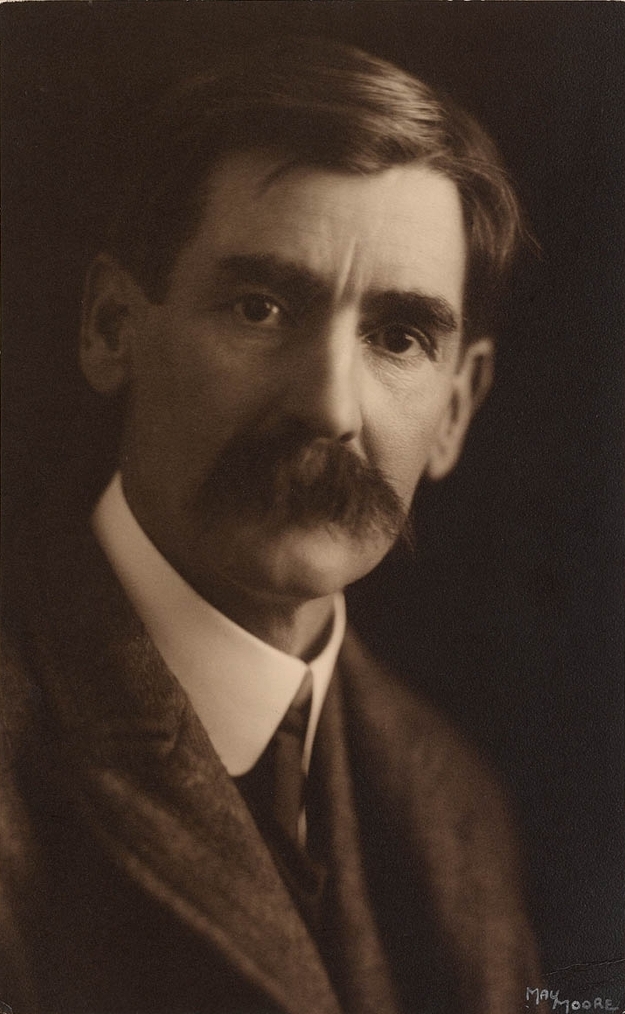

HENRY LAWSON

PETER LAWSON

Hermin Jansen and William Slee married sisters, who were daughters of John Nelson, a timber merchant of Grenfell. Jansen's wife was only 16. Peter Lawson married Louisa AIbury, of Golden Gully. She was the daughter of Henry Albury and Harriet Winnorphan, daughter of a minster who migrated to Australia. Louisa Lawson received her education at Mudgee, at the public school, under Mr. Alpress, a scholar in classics and at one time chief inspector. She was his brightest pupil, and he took a keen interest in her, lending her his books from his private library and encouraging her to write verse and study prose. Louisa Albury wrote poetry at a very early age, but published little until late in life. Henry, who commenced his work when he was 11, was inspired by her efforts. She controlled his inspiration until he was 21. "My Literary Friend" referred to her.

LOUISA LAWSON

She, herself, published a Journal as far back as 1888. This year is a memorable one in Henry's work, because of "Faces In the Street." Peter Lawson had been married only a few months when he packed his household upon a dray, and, with his girl wife, faced towards Grenfell. The journey from Golden Gully — which is five miles beyond Mudgee — across country to Grenfell, over unmade roads, 53 years ago, can scarcely be imagined in these days of good roads. Just where they are going to unveil the obelisk today Peter pitched his camp, and here the poet was born. According to mother, he was the "crossest baby ever born" — a thin weakling, who did not enjoy robust health until he was 20. LAWSON'S BIRTH (1924, March 20). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 10 (FINAL EXTRA). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article224574330

HOSPITAL'S MEMORIAL TO POET.

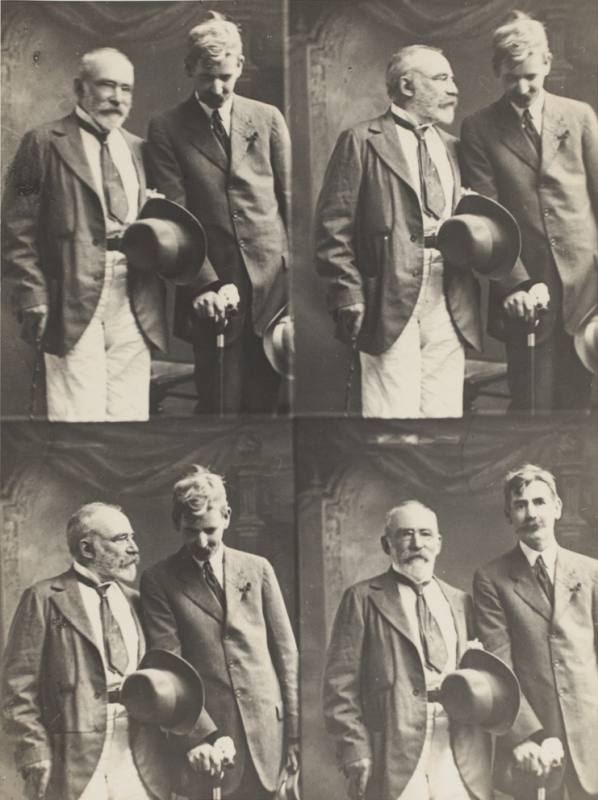

The Minister for Health, Mr. Ely (right), unveiled a memorial to Henry Lawson yesterday at the Coast Hospital. Left: Mr. Roderic Quinn, the poet. HOSPITAL'S MEMORIAL TO POET. (1931, December 10). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 12. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16803999

The Bard of Grenfell

(Henry Lawson.: 1867-1922)

On a day reminiscent of the cold wet and windy, night on which Australia’s bard was born near the old diggers' cemetery at Grenfell, there was a pilgrimage to the birthplace where, in 1924 a memorial was unveiled in honor of the Grenfell poet. This pilgrimage was on Friday last.

Writing to us some years prior to the unveiling ceremony Henry Lawson informed the writer that in some verse which appeared in 'The Buletin' about nine years previously, appeared these lines — 'You were born on Grenfell goldfield— And you can't get over that.' . The letter now is in the Mitchell Library, but we have a photostat, and Lawsons' signature to that, and the one which appeared on the stamp issues appropriately on Friday are exact. In his opening remarks the Mayor stated that he had been informed that Lawson came back to Grenfell when he was about thirteen years of age and worked on the Bimbi road about three miles out. It is the first time, we have heard that Lawson ever came back to the district of his birth, and an authentic statement to this effect would be of local and historical importance. ..

MESSAGE FROM BERTHA LAWSON.

It is most gratifying to know that the memory of my late husband, Henry Lawson is being honored by the citizens of Grenfell on the 82nd anniversary of his birth. In honoring Henry Lawson you are honoring Australian literature which is steadily becoming a strong influence in this country. In this connection I am delighted to know that the children are participating in these ceremonies, as it is through them that the torch of Australian art will be carried into the future. The pioneering days of Australia are passing, but they will always be kept alive as vivid memories through the work's of Henry Lawson and other writers who are following in the track which he blazed so long ago. I congratulate you in honoring Australia's writer, and my greatest regret is that owing to indifferent health I am unable to be present on this great occasion. I have happy memories of the schools which I visited on the unveiling of the obelisk in Grenfell to Lawson's memory, and I feel that just as Stratford-on-Avon has become a shrine to lovers, of William Shakespeare, so will Grenfell be the shrine to Henry Lawson’s memory. The Bard of Grenfell (1949, June 20). The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser (NSW : 1876 - 1951), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113436912

Henry Lawson Memorial: Unveiled in Outer Domain

HENRY LAWSON.

In the presence of about 3000 people, at 3 p.m. on Tuesday, 28th ult., his Excellency the Governor, Sir Philip Game, unveiled in the Outer Domain the statue (or, to be accurate, the group) which his admirers (chiefly the school children) caused to be erected to the memory of Henry Lawson.

The Lord Mayor of Sydney, Alderman Jackson, M.L.A., presided, and with him on the platform was a gathering of representative citizens, including the Minister for Agriculture (Mr. Dunn), Mr. T. E. Bavin (leader of the Opposition), Sir Daniel Levy, M.L.A., Dean Talbot, Mr. Ifould (Government Librarian), and other members of the Lawson Memorial Committee; Mrs. Lawson (widow), Miss Bertha Lawson and Mr. Jim Lawson (daughter and son), and Mrs. J. T. Lang (wife of the Premier, and Lawson's sister-in-law). His Parliamentary duties prevented the Premier himself from being present. Seated round the platform were many members of the Fellowship of Australian Writers, among them being Mrs. Gilmore, Bod. Quinn, Steele Kudd (A. B. Davis), Jim Grahame, and other old-time friends and companions of the poet, not a few of them from the bush, including Mr. James Dooley, who was Premier of N.S.W. when Lawson died. Official Addresses. When introducing his Excellency the Governor, the Lord Mayor, commenting on the gifts of vivid depiction of everyday life which Lawson possessed, said it was a vexed question whether Lawson would be remembered by his prose (short stories) or his poetry. Time alone would tell. Adverting to the newspaper controversy over the choice of the site for tho monument, the temptation to compare Lawson with Burns could not be resisted. The palpable invidiousness of such comparisons did not seem apparent to the Lord Mayor.

Except insofar as 'The colonel's lady and Judy O'Grady are sisters under the skin, as a pioneer Australian writer, Lawson worked in totally different media from that of Bums. And either in quality or quantity of achievement, the bard of Mudgee was not comparable with Scotland's poet. So why compare them at all? Lawson was big enough to stand on his own merits as a writer; and to compare him with Burns or any other Olympian is manifestly unfair to Lawson. If they could not appreciate him for his own intrinsic worth, better to leave him unread. When declaring the statue unveiled, the blustery wind having anticipated him and unrobed the group, a circumstance to which he humorously referred, his Excellency said it was well that Australians, and especially the children, commemorated our gifted men. The life that Lawson knew and so admirably depicted was fast disappearing; and it was gratifying to know that in his verse and in his prose Lawson had left a legacy which future generations would find pleasure and profit in.

Unveiling Lawson statue, 1931,by Sam Hood. Image No.: a215027, from Hood Collection part II : [City streets and scenes: including streetscapes, labour processions, military parades and memorials, statues and Cenotaph], courtesy State Library of NSW. The Statue was designed by George Lambert and is of the poet, a swagman and his dog and a fencepost. Lawson’s son Jim posed for the figure of Lawson, and the model for the swagman was Conrad von Hagen with alliterating, according to some sources, to St John in Rodin’s St John the Baptist preaching 1878–80, in Lawson's pose by the creator, and Rodin’s best known work, The thinker 1880, in the swagman.

Commenting on the beauty of the site, which is indeed a happy choice, the Governor said that if the shade of Lawson ever descended from Elysium to visit the Domain, it would be so charmed with the location — the thickly-foliaged surrounding trees, the lovely harbour view and all — that it would be reluctant to return. A youth named Hauptmann recited Lawson 's fine verses, 'Waratah and Wattle,' and after relating the difficulties which, the committee had to overcome, and paying a compliment to the memory of Lambert, the sculptor, Mr. Ifould, who had taken the chair on the departure of the Lord Mayor on civic business, thanked the Governor for his presence and his interest. The proceedings then closed.

HENRY LAWSON: IN MEMORIAM.

Now, who may tell as he with skill

The story of bush days,

Bring back to us the memories

Of strange, yet homely, ways,

In book to which the perfume cleaves

From spray of gum between the leaves?

Where'er the billy boils to-day,

A man awaits his mate,

And wonders, watching by the fire,

What keeps that mate so late;

Thinks he must soon a footstep hear

Come down the rough track running near.

The furthest outback settlement

To him lays friendly claim.

He wrote about its daily life,

And so it shares his fame;

Bid Harry Lawson time o' day.

His portrait, for Australia's sake,

Hangs on Art Gall'ry's wall,

And bush folk, coming down to town,

Are free to make a call,

In spirit speak with him again

By Wombat Creek, or One-Tree Plain.

An Appreciation. BY M.P.T. Australia's best-loved poet was born in 18*7, he was 55 years old at the time of his death, and except for a short time spent in England and New Zealand, he lived all his life in the land of his birth. His father was a Norseman, and his mother an Englishwoman, of Gipsy extraction. To her he owed his love of literature and his poetical inspiration. He was born in a tent at Grenfell (N.S.W.) , and spent his boyhood days on the goldfields with his father. He was afterwards stockrider, rouseabout, boundary-rider, shearer, swaggie, and coachbuilder.

Sang With the Soul of an Australian.

He was the first poet to sing of his land with tho soul of an Australian. Kendall, whom he loved, was an Australian by birth, but borrowed much from England and other lands. Gordon was not an Australian. Both missed by an aggravating margin the atmosphere of Australian life, but Lawson, with the inspiration of genius, caught it, and held it fast. Not one word by Lawaon is un-Australian, and every picture he painted and every character he drew can be seen to-day in the backblocks. He communed with the soul of our nation, and her whisperings he delivered to the world. He will never die, though we are too close to his time to view his worth in true perspective. That much of his verse is crude is true, but, like the Australian character, it is frank, direct, and soul-stirring. His gems he often failed to polish, but they are true gems for all that. The cruder his words, the truer they are, for he wrote of crude things, and fitted his pen for its task. He commenced writing about the age of 21, and had his poems published in many Australian papers. At the suggestion of Angus and Robertson, he collected his works into book form, both prose and poetry — 'On the Track and Over the Sliprails,' 'Verses Popular and Humorous,' 'When the World Was Wide,' 'Joe Wilson and His Mates,' 'When I Was King,' 'Children of the Bush,' &c. What He Looked lake. In later times Henry might be met in the streets of Sydney, a tall, lank figure, smoking a long, lank pipe, with stray lank wisps of hair under an old brown hat. Ho was a child of nature, as gentle as ho ought to be. His soft, brown eyes invited you to talk to him, and his low-pitched, mellow voice won you. He had the quiet, subdued speech of the very deaf, but his eyes twinkled like stars. The writer recalls many a conversation with Henry at his Latin quarters in Bathurst-street and Sussex-street, and left him always with a great love. On one occasion, Henry was unsteadily lighting his pipe, and a Chinese fruiterer, standing by, held a match in his cupped hands for him. 'Ah,' said Henry, looking up at him with soft, beaming eyes, 'the light of Asia.'

His Humour and Pathos.

On a more recent occasion, two Sydney priests, friends of his, met him on a street corner, and engaged in familiar chat with him. In the interval of lighting his pipe, they talked to each other of the possibility of securing a pension for him. It must have been the roar and rattle of the trams that made his deafness cease for an instant. Looking up over the lighted match, he murmured: Three men met at the corner of a street, As three men often do; One was a priest, the other a priest, And tho third had no money, too. The humour of his writings is irresistible, and the pathos clutches the heart. His first effort was 'Faces in tho Street,' sent to the 'Bulletin,' when, he was 21 years old. Its immediate success astonished him. He was surprised to think that he could write verse that interested readers. The following is an extract from that first poem:

They lie, the men who tell us, for reasons of their own,

That want is here a stranger, and that misery's unknown,

For where the nearest suburb and the city proper meet

My window sill is level with the faces in the street,

Drifting past, drifting past,

To the beat of weary feet —

While I sorrow for the owners of those faces in the street.

'I Have Starved in the Trenches These Forty Long Years.'

Many predicted that his inspiration was morbid and meteoric. It could not last, they said. As recent as 1915 a pathetic figure presented itself at a military depot to enlist for the war. It was Henry Lawson. He was rejected, of course, but wrote pathetically:

They say in all kindness, I'm out of the hunt, Too old and too deaf to be sent to the front. A scribbler of stories, a maker of songs, To the fireside and armchair my valour belongs, Yet in hopeless campaigns and in bitterest strife I have been at the front all the days of my life. Oh, your girl feels a princess, your people are proud, As you march down the street to the cheers of the crowd ; And the nation's behind you and cloudless your sky, And you come back to honour or gloriously die; But for each thing that brightens, and each thing that cheers, I have starved in the trenches these forty long years.

The Poet of the Shearing Shed.

He is the poet of the shearing shed. Nobody can paint a scene as Lawson painted it. Not a word too many, not a word too few. But you must have seen the shearing shed to realise all this if with eyes of the body you have never seen the fleece clipped off the sheep huddled in the pens, the shorn sheep shoved down the shoots, then with the eyes of the imagination the scene is yours. It would not be truer to life than the words of Lawson make it:

Roof of corrugated iron, six foot above the shoots; Whiz and rattle and vibration, like an endless chain of trams, Blasphemy of five and forty — prickly heat and stink of rams I Barcoo leaves his pen-door open, and the sheep come bucking out; When the rouser goes to pen them Barcoo blasts the rouseabout; Injury with insult added, trial of our cursing powers— Cursed and cursing back enough to damn a dozen worlds like ours; 'Take my combs down to the grinder,' 'Seen my (something) cattle pup I' 'There's a crawler down in my shoot — just slip through and pick it up.' 'Give the office when the boss comes,' 'catch that gory ram, old man;' 'Count the sheep in my pen, will you!' 'Fetch my combs back when you can,' 'When you get a chance, old fellow, will you pop down to the hut? Fetch my pipe — the cook'll show you — and I'll lot you have a cut.' Have you ever been in a shearing shod before the ladies come down from the house, and while the ladies are there? You can appreciate Lawson 's humour when he tells you about it: 'The ladies are coming,' the super said To the shearers sweltering there, And 'the ladies' mean in the shearing shed: 'Don't cut 'em too bad. Don't swear.' The ghost of a pause in the shed's rough heart, And lower is bowed each head; And nothing is heard save a whispered word And the roar of the shearing shed. They are girls from tho city (our hearts rebel As we squint at their dainty feet) ; And they gush and say in a girly way That 'the dear little lambs are sweet.' And Bill the ringer who'd scorn the use Of a childish word like damn, Would give a pound that his tongue were loose As he tackles a lively lamb.

THE LAWSON MEMORIAL.

Verses to His Children. To his two children, Jim and Bertha, he wrote most touching verses:

But in those dreamy eyes of him

There is no hint of doubt —

I wish that you could tell me, Jim,

The things you dream about.

You are a child of field and flood,

For with the Gypsy strain

A strong Norwegian sailor's blood

Runs red through every vein.

These lines I write with bitter tears

And failing heart and hand,

But you will read in after years,

And you will understand;

You'll hear the slander of the crowd,

They'll whisper tales of shame;

But days will come when you'll be proud

To bear your father's name.

To Bertha.

When I was good I dreamed that when

The snow showed in my hair,

A household angel in her teens

Would flit about my chair

To comfort me as I grew old;

But that shall never be —

Ah! baby girl, you don't know how

You break the heart in me

But one shall love me while I live,

And smooths my troubled head.

And never brook an unkind word

Of me when I am dead.

Her eyes shall light to hear my name,

Howe'er disgraced it be—

Ah!baby girl, you don't know how

You help the heart in me

............... Henry Lawson Memorial: Unveiled in Outer Domain (1931, August 6). The Catholic Press (Sydney, NSW : 1895 - 1942), , p. 16. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article103850564

HENRY LAWSON MEMORIAL.

A Florentine bronze tablet, unveiled in the Henry Lawson Reserve, Abbotsford, on Saturday afternoon by Mr. Roderic Quinn, a life-long friend of Lawson, commemorated the dedication of the park and the planting of a flowering gum in September by Mrs. Lawson as a token of devotion to her late husband. HENRY LAWSON MEMORIAL. (1939, March 27). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 6. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17587677

Honour to Henry Lawson.

THE fact that the Australian poet, Henry Lawson, gained much inspiration for his work at the rugged and splendid look-outs at Mt. Victoria was referred to at the last meeting of Mt. Victoria Group of the Sights Reserves Trustees. It was decided to make an effort to commemorate the poet's memory by constructing a pathway and lookout at the place where he was so often to be found enjoying the quiet solitude of the mountain ramparts.

The site referred to was Marrara residence, Mt. Victoria, and its surrounding cliff walk. It was resolved to construct a walk to be known as ' 'Henry Lawson Walk," to extend from this property to Engineers' Cascade. Mt. Victoria, and to name the point "Henry Lawson Lookout." The Shire Council is to be asked to invite the relatives of Henry Lawson to the official opening of this site when it is completed. Honour to Henry Lawson. (1941, December 25). Nepean Times (Penrith, NSW : 1882 - 1962), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108731200

HENRY LAWSON

When on September 2, 1922, Henry Lawson died, he left behind him little of this world's goods. A pen to one literary mate, a favourite pipe to another, an inkstand to another. Little else. But these things were Lawson's greatest possessions — the pen, the pipe and the inkstand were all that he required to give to Australia greater wealth than ever can be expressed in terms of money. His wealth lay in the merit of his work, in- the new appreciation be expressed of Australia and of Australians. Some men leave much money wherewith to create works and institutions for the good of humanity. Money played no great part in Henry Lawson's world. He left printed words of far greater value — and a pen that had framed those words; a pipe in whose smoke he had dreamed his literary dreams [ writes "C.E.S.." in the Melbourne Age"].

Henry Lawson was born at the Weddin Mountain gold diggings, near Grenfell, in New South Wales, on June 17, 1867. His father was Peter Hertberg Larsen, a Norwegian who came to Australia as quarter-master on a Norwegian ship, which he deserted to go to the gold fields. His mother was Louisa Albury, a woman as remarkable as her son. A native of Mudgee New South Wales, and a daughter of a man of Kent, with gipsy blood in his veins, she married Peter Larsen at the age of 18, and after living some years on the goldfields, settled with him in a selection near Mudgee. In the early eighties the family was driven to Sydney, because of the hardships and poverty of the land. For a while she kept a boarding-house but in 1887 bought a journal named the 'Republican,', which young Henry edited under her guidance. The following year she founded the 'Dawn", edited, printed and published by women, and for about seventeen years she prosecuted the feminine cause in this journal. She died in 1920 a remarkable woman to whom Henry Lawson owed much. Henry's early impressions were those of the poor selection, near Mudgee.

When the family came to Sydney , in 1883 he became a coach painter, at which trade he worked, very irregularly. In 1887 his first verses, 'The Song of the Republican' were published in the 'Bulletin,' They immediately attracted notice, and at the age of 21 he was the most remarkable verse writer in Australia. The Lawson of this period echoed the unrest of the country, industrially and politically; there was in his songs the surge of rebellion. This unrest surged through the young Lawson. In the years that followed his first appearance in literature he became a wanderer over the face of Australia. Victoria, Queensland, West Australia, the trackless plains of north-west New South Wales knew him. Of this period in his life David McKee Wright has written :— 'He has lived the life that he sings, and seen the places of which he writes ; there is not a word in all his work which is not instantly recognised as honest Australian. The drover, the stockman, the shearer , the rider far on the sky line, the girl waiting at the sliprails, the big bush funeral the coach with the flashing lamps passing the night along the ranges the man to whom home is a bit memory and his future a long despair, the troops marching to the sel- struggling through blinding gales the great grey plain, the wilderness of the Never Never— in long procession the pictures pass, and every picture is a true one, because Henry Lawson has been there to see with the eyes of his heart. Critics of the young Lawson shook their heads, and said he was prematurely developed; that his work would fade away. But Lawson, continuing to live his nomadic life, stayed on. As the years passed so his work gained in strength. He continued his wanderings, and he continued to write.

New Zealand claimed him for a spell, and while there has for a time made a pretence of working as a clerk in the Government statistician's office! Poor Lawson. One can imagine him cooped up in an office of a public service department trying to give attention to figures, while outside the track called!

For a time he edited the 'Worker' in Sydney, but the urge of the track was too strong for him. He went to West Australia; then again to New Zealand, where for a time he was a teacher in a Maori school. Then to London, where for two years he suffered the crampedness of London. Back again to Sydney and out on the tracks— the nomad, living and writing on the track appearing only at intervals in the cities.

Lawson was the man who could not get away from the life of outback; the men he wrote of were also this type. Paterson wrote at this time of the drover who sees the vision splendid of the sun-light plains extended, And at night the wondrous glory of the everlasting stars.

Lawson made the drover say : Shrivelled leather, rusty buckles, and the rot is in our knuckles; Scorched for months upon the pommel, while the brittle rein hung free. Lawson wrote thus because he knew. He continued to write thus because he lived the life— and could not get away from; it. Not one who has come since has written as Lawson wrote. It seems none ever will. He was the vagabond poet, composing as he tramped the outback. Rock me hard in steerage cabins, Rock me soft in first saloons, Lay me on the sandhill lonely, Under waning western moons; But wherever night may find me— Till I rest for evermore— I shall dream that I am happy In the shakedown on the floor. The 'shakedown on the floor' expresses Lawsons philosophy of life as he saw it, as he felt it. He could have led a gentler life; he could have had wealth. Had he chosen thus he would not have been Lawson, and to-day we would not he realising the heritage we have gained from him. HENRY LAWSON (1927, September 9).Kalgoorlie Miner (WA : 1895 - 1950), p. 5. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article93997024

Nelson Illingworth made the death mask of Lawson which is in the Mitchell Library, Sydney (though there is still debate whether the mask was made in the writer's life or death). He was also something of a composer.

Born in Portsmouth, England, son of Thomas Illingworth, plasterer, and his wife Sarah, née Harvey, he studied at the Lambeth art school and worked as a modeller at the Royal Doulton potteries. He emigrated to Sydney in 1892, and in 1895 his head of an Australian aboriginal was bought for the National Art Gallery in Sydney. Other busts were purchased for the same gallery in 1896 and 1900. It was also in 1900 that chronic rheumatism hampered his work and he was declared bankrupt.

MR. NELSON ILLINGWORTH.

Sir Jospeh Abbott presided at a meeting held at the Hotel Australia yesterday afternoon with the object of assisting Mr Nelson Illingworth the well known sculptor, whose illness has caused his family and friends anxiety during the last few weeks. The chairman, in introducing the subject to the many people present, referred to his own connection with the Art society la days past, to his sympathy with every branch of art, and to the excellence of the work which had recommended Mr Illingworth to his notice All who knew that estimable sculptor would regret to learn that he had been struck down by illness under circumstances which had led to the assemblage of that afternoon Mr Bruce Smith, who moved the first resolution, uieuuouod that he had known Mr Illingworth for years, and could testify to his sterling worth or character, and to the fervour for his ait which ni« ays mspited him Mr Illingworth s busts of Mr Barton and Cardinal Moran demonstrated his capacity for work of the highest quality, and in regard to the latter, at any rate, Mr Toohey and a few gentlemen were endeavouring to arrange for the acquisition of such a fine example of his style Mr Illingworth had always been ready to help others, and that fact pleaded strongly for him during his present illness.

As the result of these and other kindly speeches, resolutions were pased with enthusiasm to the effect that a fund should be formed upon lines to he determined by the following committee -Sir Joseph Abbott (chairman), Messrs B R Wise and Bruce Smith (hon treasurers), Messrs George Taylor and Alexander Knox (hon secretaries), the Hon E W O'faulhum (Mininster for Works), Mr D O'Connor, Q C , Messrs. W M' Leod, Livets, Allpress, H Weir, L Hopkins, W Martin, J Barlow, ...Fred Broomfield, W Listet Lister, A Collingridge, D Gray Ogden, E Lewis Scott, T A Philp, E Bollier, J W Turner, ... V J Daley, Moorhouse, Lcnst btaedtgeu, N J Gehde, W Harper,... MR. NELSON ILLINGWORTH. (

1900, July 10).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14323028

Illingworth did some architectural sculpture for buildings in Sydney, and a large number of portrait busts of notable men of his time such as Australia's first Prime Minister Sir Edmund Barton and 'Father of Federation' Sir Henry Parkes. He also went to New Zealand and modelled some busts of Maori chiefs for the government. At Papawai pa, New Zealand, he erected a monument in 1911, to the memory of Hamuera Tamahau Mahupuku, a distinguished chief of Ngati-Kahungunu.

MR NELSON ILLINGWORTH.

Mr. Nelson Illingworth, the well-known Sydney sculptor, died suddenly at Harbord, near Manly, early on Saturday morning, aged 63 years.

At the time of his death, Mr Illingworth was engaged on plans for the Henry Lawson competition statue. He was spending a few days with some friends at his cottage at Harbord, and intended to return to Sydney on Tuesday morning. When he retired on Friday night he was in good health, but just after 2 a.m. on Saturday he awoke, feeling ill, and died half an hour later.

The important works executed by Mr. Illingworth Included busts of Archbishop Saumnrez-Smith, Sir Dension Miller, Cardinal Moran, Lord Hopetoun, Sir Thomas Hughes, Sir Edmund Barton, Mr, R. B. Wise, Sir Julian Salomons, Sir Henry Parkes, Messrs. Victor Daley, Henry Lawson, and General Birdwood. He had almost completed a portrait of the State Governor (Sir Dudley de Chair). Mr. Illingworth's studio In Margaret-street was a recognised visiting place for artists and writers.

The late Mr. Illingworth's son was formerly a teacher at the Conservatorium of music and recently went to the United States.

The funeral will leave the home of his family, Hakone, Badham-avenue, Mosman, for the Northern Suburbs Cemetery, at 2.30 p.m. to-day. MR NELSON ILLINGWORTH. (

1926, June 28).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 17. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16301613

The latest cable news states that Lady Mary Lygon will accompany our newly-appointed Governor, Earl Beauchamp, and will remain in Sydney about three months.

Mr. Samuel Hordern is entertaining a few friends on board his yacht Bronzewing up the Hawkesbury River. SOCIAL. (

1899, February 11).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 7. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14199844

Henry Lawson

Mr. M. C. Butchart writes from 39 Addison road, Manly: — Your welcome paper comes regularly to hand, and reading references to Henry Lawson brings back to mind many pleasant meetings with Henry Lawson down here in days gone by. I would meet him often and stroll round Manly and enjoy his companionship. He was not by any means a boisterous companion — far from it; staid, steady, deep thinking man and genial in every way. He had steady, dark, piercing eyes — one could not but be struck by them; they were a feature about him that could not be but noticed. Many a quiet, genial pot we quaffed together, and when he would start to talk — it was difficult to get him going — he was more than interesting. These meetings took place some little time before his death — how time flies — now dead some seven years; long may his memory remain, and his writings bring back many pleasant memories. I attach several, principally 'Here's Luck,' which at present is very applicable to the happenings to-day (Aug. 30): Henry Lawson (

1929, September 5).

The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser (NSW : 1876 - 1951), p. 6. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115894031

The Marmaduke Constable Butchart and his wife were residents of Manly for decades, one son being born at 'Hindoo' in 1901, a daughter, Harriet, passing away as a two month old in 1906 at 'Surbiton', Manly.

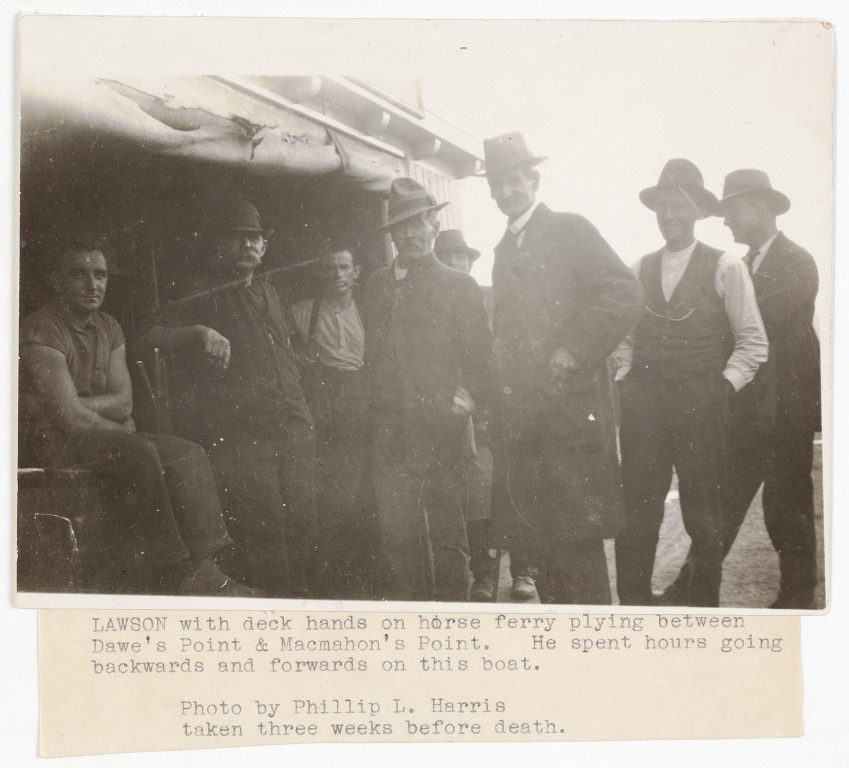

The death occurred on Saturday morning of Henry Hertzberg Lawson, Australia's national writer, and one of the outstanding figures in our literature. A remarkable career was his — a career packed to the full with life and movement, with little light and much shad^. He was born on the Grenfell Goldfields on June 7, 1867. The name of his father — a sailor who had run away at Melbourne and taken to the bush, was originally Larsen; but before the poet was born the name had been Anglicized to Lawson. His mother, Mrs. Louisa Lawson, a native of New South Wales, also produced a good deal of prose and verse, and is best known as the founder and editress of 'The Dawn.' It was in the real, old-time bush that the youngster spent his early years. This environment left a mark on his character which was never effaced; gave birth to a love that blossomed forth into some of the loveliest of our verse. A shy, sensitive boy, threatened with deafness, he was often given to melancholy. His schooling was so scanty as to hardly justify the name and at an early age he started work. He tried his hand at shearing, splitting, droving, and at all manner of country work. On one visit to Sydney he took up coach painting. About nine months ago Lawson suffered a paralytic stroke, and after a long stay in hospital he showed signs of breaking up.

A few weeks ago he prevailed on an old friend to have a day's outing with him among his old haunts at North Shore, where he had lived for many years. Here, with well-known associations about him, he sparkled out into his old self, and next day wrote some prose that was quite in keeping with his best standards. About a week ago he went to live in the Great Northern -road, Abbotsford, and here he produced a good deal of verse and prose, most, of the latter being biographical in character. He was taken ill on Saturday morning, and although a doctor was called immediately he died within a quarter of an hour. He is survived by a widow and two children, Bertha and Jim. DEATH OF HENRY LAWSON. (

1922, September 6).

The Don Dorrigo Gazette and Guy Fawkes Advocate (NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article171991474

Henry Lawson waiting for horse ferry at Dawes Point, Sydney, 1922- Photographs of Henry Lawson in North Sydney including his former residence, 1922(three weeks prior to him passing away) - photographed by Phillip Harris. Image No.: a6161001h, courtesy State Library of NSW.

Soldier's Letter.

Driver Norman Butchart writing to his father, Mr. M. C. Butchart, from France, under date 11th September, says : — Have not written you for some little time, haying been kept going a lot, but thank goodness now we are well out of things and miles and miles from the fighting line, back out for months and months. It's great to get back around these parts, everything seems so peaceful ; no bombs or shells to worry about. Had rather a rough time the last six months or so, but now, thank goodness, have finished for some little time, and from the look of things I honestly think we may not see much more fighting. Have received all your letters. . . . . To-day we were officially told that our Battalion, owing to lack of reinforcements, would be broken up ; its mighty hard to see the old regiment pass out, and everybody feels things very badly; I felt real downhearted myself ; we will go to other battalions and units of the Brigade, but what unit I am going to so far I do not know, but in all probability will be transferred in the course of the next week or so. It is promised that when hostilities cease, those of us that are left will be re-organised again and return to Australia as the 19th Battalion, and thank goodness the 19th so far has yielded not one inch of ground, and every time we've been in action we came out with colours flying ; I don't think there are any battalions in the A.I. F. with a better record — anyhow am positive we are second to none. Our chaps have fought and died in all countries, and always facing the enemy and heads in the air for dear old "Aussie." I've been' through continuously with the Battalion — mighty lucky, thank God. Great news these days, dad, and now think its coming our turn, and hope the Hun gets everything that's coming to him, and feel sure he will. Everything is going splendidly — couldn't be better.Soldier's Letter. (1918, December 24). The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser (NSW : 1876 - 1951), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article111955942

LOCAL NEWS

WEDDING. Butchart—McCarthy,.

Mr. Norman Butchart and Miss Kathleen McCarthy, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. McCarthy, late of Grenfell, were married on Friday at St. Mary's Church, Manly, Father McGovern performing the ceremony. After leaving the church the wedding party adjourned to "Dungowan," where a prettily laid out and sumptuous wedding breakfast was partaken of, all thoroughly enjoying themselves, passing a real merry and happy time. The usual speeches were made, felicitating the bride and bridegroom, and dancing was indulged in, terminating shortly after 5 o'clock. Among the friends present were Mr. and Mrs. Perdriau, Mr. and Mrs. Erwin, Mrs. Bell, Miss Howley, Mrs. Tarlby, Miss G. Butchart, Mr. Boy Perdriau, Mr. Colin Butchart, Misses Jean McCarthy, Biddy Perdriau, Billee Cooper, E. McCarthy, D. McCarthy, Mr. Tom Roberts, Mr. and Mrs. Lea Hogan, Misses Jill and Judy Hogan, Mr. and Mrs. Speirs, Mr. W. F. McCarthy and Mr. M. C. Butchart. The week prior to the wedding Mrs Lea Hogan, sister of Mr. Norman Butchart, entertained at a shower afternoon tea, at her home in Manly, over forty friends of the happy couple, at which many handsome presents were made, and a very pleasant and happy time was spent. LOCAL NEWS (1928, June 25). The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser (NSW : 1876 - 1951), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115900526

GREETINGS.

In forwarding season's -greetings, Mr. M. C. Butchart encloses the following from his book of cuttings: — ' 'IF I HAD MY WAY.'

If I had my way, I should sow in my garden the seeds of loving kindness, and take care that some fell in my neighbor's garden also. I would plant the herbs of sweet temper, and the shrubs of unselfishness. In another corner I would plant the' bulbs of sweet content, and the sturdy trees of truth. ?I would sow the seeds of patience and the plants of forgiveness and forbearance. I would plant a border of happiness, intermingled with joy. I would plant a hedge of love and a trellis of true friendship. If I had such a garden, I should ask my friends to come and take cuttings of the plants with them, and so endeavor to do a little good in the world. GREETINGS. (

1928, December 20).

The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser (NSW : 1876 - 1951), p. 5. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115904033

Reminiscences

by M C Butchart

Reminiscences.

When Haddon Chambers (a nephew of the late Mrs. W. B. Howarth) visited Grenfell no one would have believed that he would become one of the most successful playwrights of his time. His sense of comedy was unerring, although his treatment of dramas as a rule was also sure. Beginning with 'Captain Swift,' which part was played by Maurice Barrymore, he wrote 'Passers-by,' 'The Tyranny of Tears,' 'Tante,' 'A Modern Magdalene,' 'John a Dreams,' 'The Idler' and so on. A more delightful companion that Chambers could not be found. He was universally popular. No matter what his income might be he always lived up to it. When he was down in his luck only those who enjoyed lending him money ever guessed it. His clothes were perfect, his appearance ifuaculate. No one could equal him in the art of ordering a lunch or a dinner. He was never a prolific writer. He indulged himself in long intervals of relaxation between plays. Trips to the Riviera and to. St. Moritz he took as a matter of coursed

In later years I met 'Banjo' Patterson at Grenfell when he was interested in some portion of the Weddin Mountains. I had not seen him since I had left the Sydney Grammar School when we had both been to school under the headmastership of the late grand A. B. Weigall. Patterson was not a frequent visitor to Grenfell, and eventually gave up his Weddin Mountains property. He was at the South African war as ' war correspondent, and went to China as special correspondent. Editor Sydney 'Evening Newg, also 'Town and Country Journal.' His poems will keep his' memory evergreen, not forgetting 'The Man from Snowy River,' 'Clancy of the Overflow,' 'Rio Grande's Last Race,' and many others.

...

Excerpts from a letter written by Lawson to his friend 'Benno,' who at the time was in Harefield Hospital in England, having been wounded in the, war. (At the time he was on a small block of land at Leeton. He said he would hold it down until some of his crippled mates returned who knew more about fruit trees than he did).

It's hot here in February — he says — and last Saturday was the limit. It was a corker. It's so hot here just now that you can wash out your pants and hang' them on the line, and run round the house and take them down dry. It's a prohibition area, and the driest and thirstiest I've ever struck. . . . We can only get together in the alleged cool of, the evening and sing 'The Gate's Ajar for Me,' 'and hope for a demijohn. . . . He concludes a long and interesting letter. 'And if Allah does not forbid, and I DO get away after all — as doctor's orderly (or disorderly) mascot, or Regimental Goat, or something — and we pass each other on the water, I'll get a wireless to you somehow. And if a submarine gets us I'll get a wireless to you all the same. And if when that message comes to you, you feel a chilly breath on your cheek and may be faintly catch the faint and mournful strains of a harp at the same time, you'll know I've been elected;, but you'll be sure I'll be doing my best under those depressing circumstances and keeping up a fire for you.

IF, on the other hand, you feel a hot breath and get a whiff of something like sulphur at the same time, you'll know that I'm among friends and old pals, and looking out for a cool and shady corner against your arrival. But we'll meet before that. 'Come Back.' I watch .the track on the redsoil plain, To the East when the day is late, For one who will surely come again, In summer heat or in winter rain, Limping under his swag in pain — For a crippled Anzac mate. — Henry Lawson. _ With your paper's kind assistance and generous indulgence I have endeavoured in my small way to pay a tribute to a kind and generous friend —a .friendship all too short for me. I found him to be, a man ever ready to assist his poor struggling fellows. He was a friend to all but himself.

As before stated — and memory revived by the late pilgrimage to his grave. I also met and knew the late Henry Lawson many years ago while living at Manly, and spent some very pleasant times in his company. We would meet of an evening, stroll round, and stop one occasionally. I found him a genial boon companion., inclined to be reserved, enjoying himself in his own quiet way. He and the late Phil May were great friends, and both very much attached to each other. Both now have gone the way of all flesh. He, as is well known, was born at Grenfell, being the son of the late Peter Hertzberg Larsen, a Norwegian, his mother being Louisa Albury, a native of New South Wales. He worked with his father as a boy and went to Sydney at the age of 17, learning the trade of a coach painter. He commenced writing verses when he was 20, and was on the staff of several papers. He travelled extensively in New South Wales, West Australia and New Zealand, engaging in various occupations, and died in Sydney in poor circumstances, being accorded a State funeral. It is mooted to erect a statue of him in the Sydney Domain near that of Bobbie Burns. The Sydney 'Bulletin' is a great supporter. The late Mr. Archibald, of that paper, was one of Lawson's best friends. A Norwegian has just lately completed a version of Lawson's poems into Norwegian for circulation in that country. I quote a verse or two from here and there:

'The Drover.'

Our Andy's gone to battle now

'Gainst drought, the red marauder,

Our Andy's gone with, cattle now

Across the Queensland border. '

Oh, may the showers in torrents

fall,

And all the tanks run over,

And may the grass grow green and

tall

In pathways of the Drover.

And may good angels send the rain

On desert stretches sandy,

And when the summer comes again

God grant 'twill bring us Andy.

'Out Back.'

For time means tucker, and tramp

you must where the scrubs and

plains are wide,

With seldom a track that a man

can trust, or a mountain peak to

guide,

All day long in the dust ami heat—

,When summer is on the track,

With stinted stomachs and blistered

feet,

They carry their swags Out Back

'The Vagabond.'

A rolling stone! — 'tis a saw for

slaves —

Philosophy false as old,

Wear out or break 'n-eath the feet of

knaves,

Or rot in your bed of mould.

Cleave to your country, home and

friend,

Die in a sordid strife,

You can count your friends oil your

finger ends,

In the critical hours of life.

Sacrifice all for the family's sake,

Bow to their selfish rule!

Slave till your soft heart they break

The heart of the family fool.

OBITUARY.

The death occurred at Manly last week of Mr. M. C. Butchart, at the age of 83 years. 'Butch.', as he was known to old friends, came to Grenfell about sixty years ago, and was manager at different times of the Oriental, Union Bank, and Bank of Australasia. He took a great interest in all matters for the good of the district, and was a first-class amateur entertainer, especially as a corner man (with the late Jack O'Brien) in ....minstrel shows. He was a man who enjoyed life to the full, and was very popular. He married Miss Jane Rich (daughter of the late Joseph Rich, who built the Royal Hotel), who predeceased him. After leaving Grenfell. the late Mr. Butchart joined the firm of Dalgety and Co. and later returned to Grenfell and opened a stock and station agency business in partnership with his son Norman. Later he went to reside at Manly, and remained there till the time of his death. The late gentleman was also for some years a member of the Western Lands Commission. A daughter (Nan) and two sons (Messrs. Norman and Colin) survive. The funeral was on Friday, the interment being in the Church of England cemetery, Manly. OBITUARY. (

1939, June 26).

The Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser (NSW : 1876 - 1951), p. 2. Retrieved from

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article115434312

THEY BURIED HARRY LIKE A LORD.

INSIDE POLITICS

by Jack Lang

No one else could have written the story as he would have written it. A State funeral for a down-and-out scribbler of verses and short stories.

The poet who hated sham and pretence. The lover of the underdog. Then in death, to receive the homage of leading citizens.

A week before they would have dodged by on the other side to avoid him. Now they wanted to bask in his reflected glory. Henry Lawson with his delicate touch of irony would have done full justice to the story. It was September 4, 1922. The setting was in all the awe of St. Andrew's Cathedral. Vice-Royalty was there with Lieut.-Gov. Sir William Cullen, the Prime Minister (W. M. Hughes), the Treasurer (Stanley Melbourne Bruce), Cabinet Ministers in striped pants. High functionaries of State. Representatives of all kinds of public bodies busily engaged in thrusting their cards into the hands of reporters so that they would be mentioned in next morning's papers as "among those present." There were a few of his old mates. Roderic Quinn, Tom Mutch, George Robertson (of Angus and Robertson) and members of his own family. But they were nearly all strangers.

HIS OLD MATES WERE MISSING

His old mates were missing. They would have been too shabby for such an occasion. There had been a lying-in-state before the funeral service. Hundreds had filed past. Many came from curiosity, others to pay tribute to a man of genius. How incongruous it would all have seemed to him. There is something about State funerals that always rings false. None could have been more hollow than this for Harry the Poet. Two days previously, at the age of 55, he had died in a small cottage at Abbotsford from a stroke. He had just about reached the end of a bitter, long road. His enemy through-out life had been drink. It had won in the end. He was broke to the wide, wide world. They couldn't even find a pair of pyjamas amongst his shabby possessions. The Premier Sir George Fuller, had brushed aside earlier requests for a Government funeral, but some newspaper reporters talked to Billy Hughes. He quickly realised that it was an occasion when he could go back to the memories of his own early days. So Billy ordered a State funeral and issued a long statement full of rhetoric. That was why they were burying Harry like a lord of the realm. The destitute poet was being carried in State down the nave of the Cathedral. It was the first time he had been in any Church for as long as I could recall. A sculptor was even commissioned to take a death mask for posterity. There were a few touches that he would have appre-ciated. The small bunch of native rose, the gum leaves, the bush ferns and the cluster of wattle blossoms that they found for the casket. There were also ornate, magnificent wreaths. The cost of any one of them would have kept him for a week. The Commonwealth Government had been paying him a munificent pension of £1 a week from the Commonwealth Literary Fund. It didn't go far. Not the way that Harry spent it.

THEY PLAYED FUNERAL MARCH

Archdeacon D'Arcy Irvine preached a very eloquent sermon. He took as his theme the lines . . . They'll take the golden sliprails down And let poor Corney in". Lawson, himself, might have chosen a few lines from "Past Carin''. But the service was most impressive. Then they played Chopin's Funeral March, and the choir sang "Rock of Ages". My own thoughts could not but go back over the years, thinking of Lawson as I had known him. Law-son the scraggy, always untidy figure with those burning brown eyes, always trying to escape from the world and himself. We had first met at Wm. Henry MacNamara's bookshop in Castlereagh St., between Bathurst and Liver-pool St. where the fire station now stands. It was next door to the old Opera House. Opposite was the Protestant Hall where Georgie Reid and Holman had some of their great en-counters and Rev. Moses held his Pleasant Sunday services. Mac's book shop was the meeting place for the anarchists, the intellectuals and the politicians of the period. MacNamara and Sam Rosa found them-selves in strife with the law over their story about the run on the Savings Bank in "Hard Cash."

CUSTOMERS AT BOOK SHOP

Holman and Hughes could be seen browsing among the books. They seldom bought any. The best customers were the parsons. Mac would some-times display a few saucy pictures, and they were his best selling line. The atheists said the parsons bought them. Andrews the Anarchist and Joe Schellenberg the atheist came to argue politics and philosophy. J. C Fitzgerald would drop in to test out his latest ideas; The poets would be there browsing. Upstairs Mac had fitted up a reading room. That was where I first met Lawson. His mother, Louisa Albury or Lawson, was a poetess. She was also editing a women's paper called "Dawn." She was a great feminist. She was as aggressive as Henry was re-tiring. She encouraged him to write.

EXCITED WHEN VERSE APPEARED

EXCITED WHEN VERSE APPEARED Lawson was not interested in serious works. While others browsed through Ingersoll, or waited eagerly for the latest book by Emile Zola, Lawson was more interested in the daily papers or any works of light fiction. Bret Harte was one of his favorites. Dickens was another. He was just making his way with the Bulletin. He would be around the book-shop then disappear for months at a time. On his return he would tell us about how he had humped his bluey outback. For a time he had a job on a Brisbane paper. He was highly excited when his verses appeared. Right from the start he was a drifter. He drifted in and out again. He said that he had Gypsy blood. But he was really a vagabond by nature, always trying to escape from the ordinary problems of life. That was what made him so sympathetic to other people. Eventually the shy Lawson plucked up enough courage to marry one of Mrs. MacNamara's daughters. I married another, so we saw quite a lot of each other. Shortly after they were married, Harry brought his young bride to stay, with us out at Dulwich Hill. I was working in an accountant's office. He was writing "In the Days When the World Was Wide" and "While the Billy Boils." He would go into the city and collect a few shillings at the Bulletin or get an advance from Angus and Robertson against future royalties. He would then forget all about writing, and start shouting for anyone who happened to come along. On one occasion he came home in a shocking condition. If he had been drinking spirits, he would be-come belligerent. If he had been on beer, he was morose and sentimental. On this occasion, it had been brandy. So we locked him in a room with a table and chair, and a candle.

Next morning he emerged triumphant. He had written "They Wait on the Wharf in Black." On another such occasion it was "Klondyke and Back." "Faces in the Street" also came into being in an attack of deep personal depression. They always say that genius is erratic. Well Harry was a genius.

MADE FRIENDS WITH AN EARL