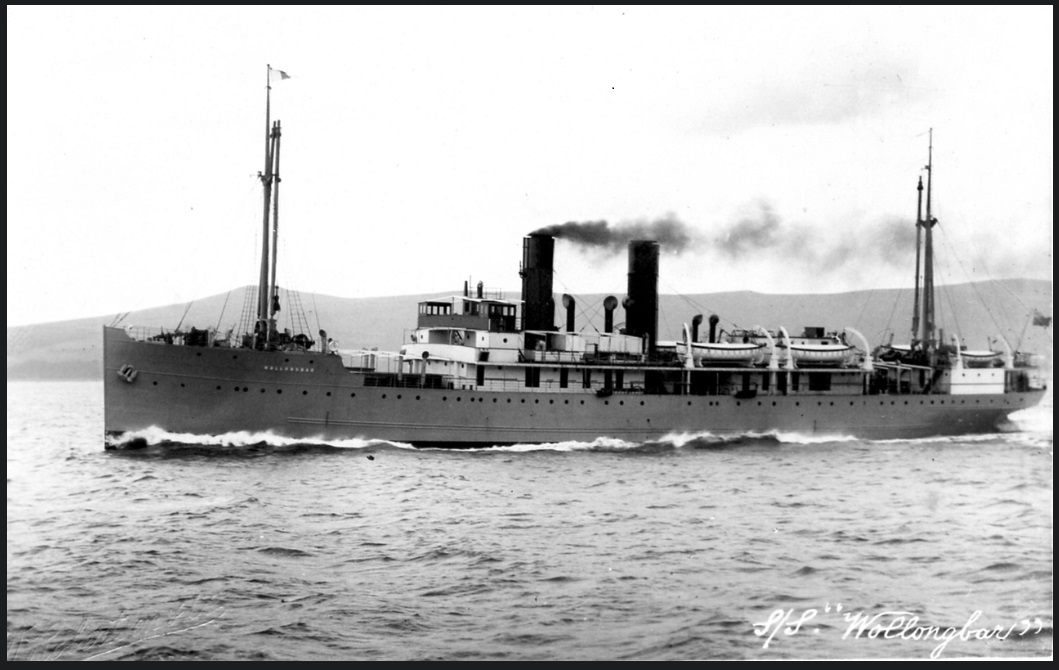

Historic Shipwreck SS Wollongbar II

A coastal freighter torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in WWII has been discovered off Crescent Head in the state’s Mid North Coast.

In 2019, the wreck’s accurate location was reported by Port Macquarie mariners although had been generally known of years prior. Heritage NSW, Department of Premier and Cabinet, undertook the first-ever archaeological inspection of the site in late 2019. This included cutting-edge multibeam and side scan surveys, and the deployment of a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) to inspect and photograph the deep site. The survey confirmed the wreck as Wollongbar II. Survey operations were assisted by AUS ROV and Fish Port Macquarie.

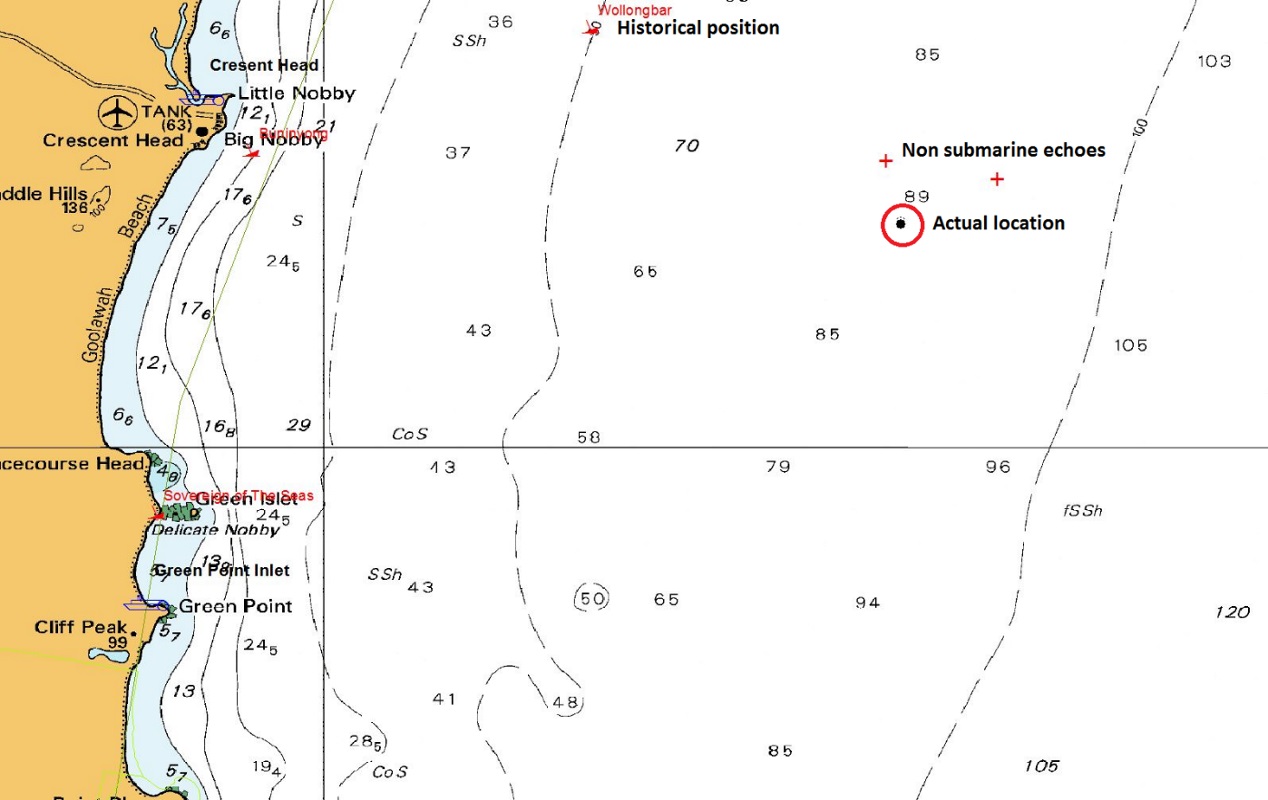

Wollongbar II, location of the wreck chart - supplied, NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment

When the vessel sank, it was carrying boxes of butter and bacon which eventually washed up on the shore resulting in a boom in cake making, which was normally restricted by wartime food rationing.

Director of Heritage Operations at Heritage NSW Tim Smith OAM said the discovery will reveal some amazing stories.

“We want relatives of those who sailed on the SS Wollongbar II to get in contact, so we can share findings of the survey conducted by our archaeologists,” Mr Smith said.

Acting Minister for Veterans Geoff Lee said the SS Wollongbar II was confirmed by archaeologists from Heritage NSW after it was reported by the local community.

“In 1943 a Japanese submarine, the I-180, destroyed the freight vessel with two torpedos killing 32 people on board,” said Mr Lee.

“The ship sank in minutes with only five crew surviving the attack.”

The SS Wollongbar II was one of many vessels lost to enemy assault along the eastern coastline during WWII.

“We have just commemorated our brave veterans on Anzac Day but it’s also important to remember the toll of war for everyday Australians,” said Mr Lee.

“This secret has been hidden at the bottom of the deep sea for decades and the find will give some closure for descendants and relatives of the 32 people who lost their lives.”

Member for Oxley Melinda Pavey said a significant part of the Mid North Coast’s wartime history has been solved with the shipwreck’s discovery.

“The Crescent Head and Port Macquarie fishing industry cooperated brilliantly to help solve this mystery and I want to congratulate Heritage NSW for its important leadership,” said Ms Pavey.

Although there were many ships sunk along our coasts during this conflict, with only minimal coverage in local newspapers as a security measure, snippets of this event through the formalities of Notices of members of the families who lost loved ones, and after peace reigned, recollections by one survivor, the story was shared through regional papers.

James Alfred Knight, late of s.s. "Wollongbar" and Vaucluse, in the State of New South Wales, donkeyman, who became missing on 29th April, 1943, and is for official purposes presumed to be dead, intestate. RE the estates of the undermentioned deceased per (1943, September 3). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 1571. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article225081786

An example of the story being shared by a survivor:

S.S. Wollongbar Sunk By Torpedoes

(BY W. J. MASON, CHIEF OFFICER OF S.S. WOLLONGBAR.)

S.S. Wollongbar left Byron Bay, New South Wales, for Sydney about 9 p.m. on Wednesday, April 28, 1943. We had a cargo of butter, sugar and bacon.

It was 10.15 a.m. when I poured myself a cup of tea in the wireless room, but instead of sitting down and having it in comfort I went out on the bridge and joined the skipper. I never got a chance to drink the tea as a voice in Scotch accent bawled out, "Look out, sub."

We gazed seaward and saw a conning tower in a big swirl of water, not more than 500 yards away. A torpedo was already on its way. You could both hear and see it, as it appeared to be coming at us very erratically, jumping and zig-zagging.

The skipper bawled, "Look out for yourselves, boys."

He went down the port ladder. The look-out man also left the bridge. Roy Brown, A.B., remained at the wheel.

I tried to push the automatic alarm in the wheel house, but as I did so the torpedo struck us just forward of the bridge with a terrific thud. Roy Brown hurried down the starboard ladder. I hung on to the bridge dodger ridge rope to see what was going to happen. I then noticed another torpedo coming from the same angle.

I moved across the bridge holding on to the ridge rope, thinking starboard would be the high side, when the ship suddenly exploded with a thunderous crash.

I came to swimming in the water, but it seemed to be getting darker instead of lighter, when all of a sudden I was breathing fresh air and seeing daylight again.

One of the survivors informed me later on in hospital that I shot out of the water like a jack-in-the-box.

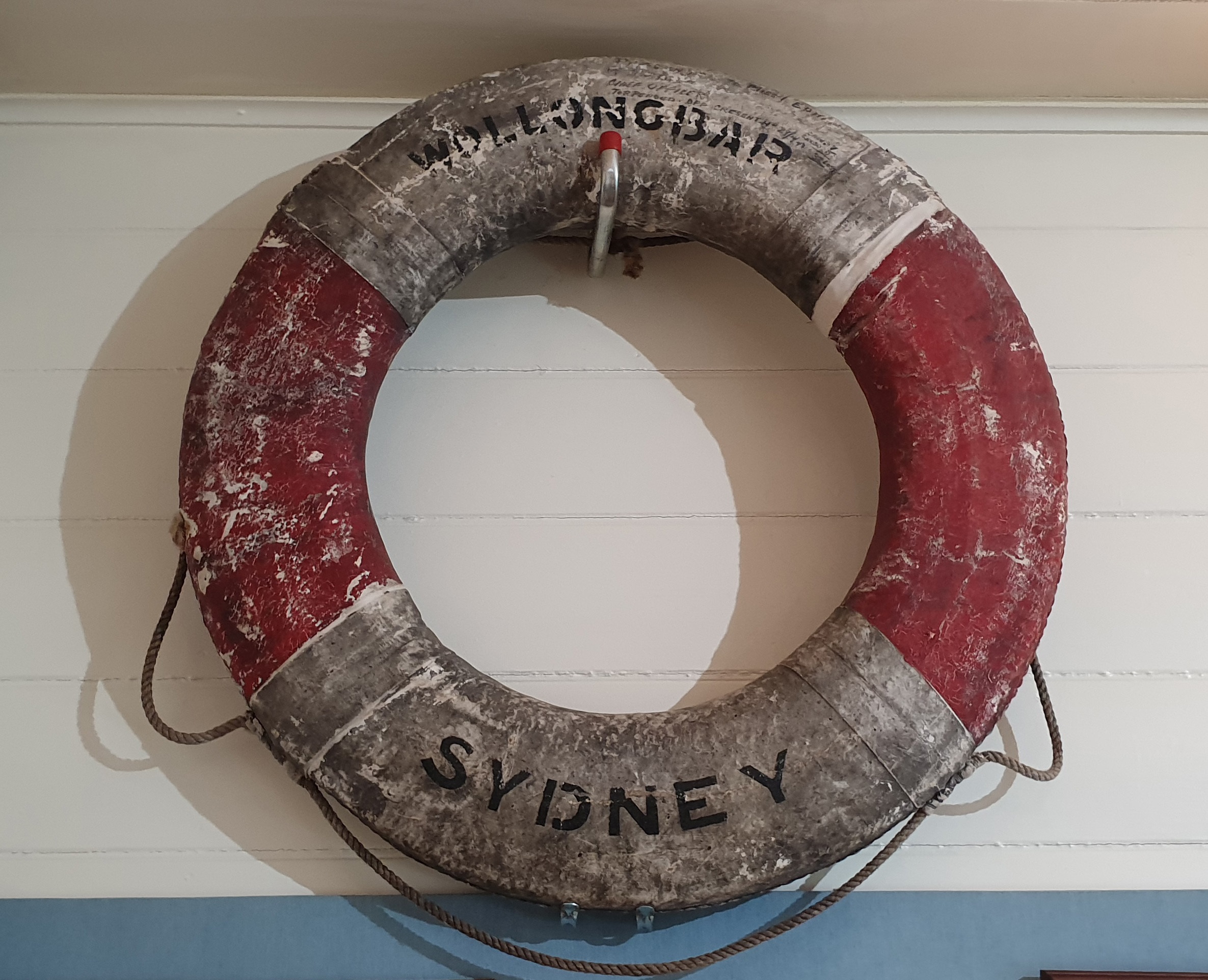

I endeavoured to secure a piece of flotsam, which I remember, was a case of butter. With its aid I reached a lifebuoy, but if some one had offered me the first prize in a lottery I could not get into it by the right method. I was scared stiff to sink under it, and had not strength to put my arms over it and throw it over my head. So I just put one arm around it, treaded water for a while and hoped for the best.

Lifering from wreck of Wollongbar II at Mid-North Coast Maritime Museum (Image: B. Duncan, Heritage NSW)

Fortunately, I was not far away from one of the lifeboats. I made my way to it and held with grim determination on to the beckets below its broken gunwale, having a fair rest before attempting to pull myself into the boat, which was full of water.

I recognised Frank Emson, greaser, laying across the bow. He murmured, "I cannot help you." I well knew that he could not. If ever a chap fought to live, it was Emson. The skin was hanging from his hands and fingers. He wanted a drink, but his lips were swollen. His eyes were closed most of the time.

The smoke and mist were slowly rolling away. A Yank bomber was flying low.

Much to my delight I noticed a raft paddling towards us. On it I recognised the only two sailors saved, Roy Brown, who had been at the wheel, and Pat Tehan. They were hale and hearty.

"Where do we go from here?" they asked. But when they saw Frank Emson I noticed a depressed feeling getting hold of them. We decided to lift Emson from the boat and place him on the raft, which was in perfect condition.

There was no life visible anywhere. We came across several rafts, but they did not appear to have anyone aboard. The raft with Emson was tied astern. Soon we sighted a man on a raft waving a piece of white wood. We shipped the oars the best way possible and went after him.

He proved to be Fireman Blinkhorn, of Lane Cove. This man had a miraculous escape. When we picked him up his clothes were still dry. He told us that he was thrown by the explosion out of a bunker and landed on a raft in the condition we found him, quite happy and unhurt. Blinkhorn was put on the raft to look after Emson, and his own raft cast adrift.

As we had frequent visits from various types of planes we knew that our position was known and that assistance would come. One plane kept signalling us to that effect, and we answered O.K. by semaphore. We searched two other rafts which were near at hand for survivors, and kept in the middle of thousands of cases of butter floating about, but because of a slight swell with an occasional white rip or break the chances were very small, for after searching in vain for about an hour and a half, I suggested to my companions that if they were satisfied there were no more men alive or dead to be seen we should endeavour to reach land before dark.

We thus pulled for the shore in a boat which had several damaged planks missing. We considered our chances of getting ashore before dark were very poor, although our pull was less than six miles.

We still had another two miles to go when we were picked up at 3.45 p.m. by Tom and Claude Radleigh, fishermen, with their launch X.L.C R.

Emson was taken from the raft and put to bed.

No time was to be lost if we were to reach port before dark. No cup of tea ever tasted better than the one the crew of the fishing launch made us.

It was just sunset when we crossed the bar at Port Macquarie.

The Red Cross had made arrangements to receive a far bigger complement than five survivors. Emson was rushed to hospital, and the remaining four were given a bath and dry clothes, and then examined by a doctor. The V.A.D.'s were wonderful to us.

I soon joined Emson in hospital, suffering minor injuries and shock. The two sailors and one fireman were allowed to return to Sydney after a good night's rest. Before leaving hospital ten days later, I had the pleasure of knowing that Emson's sight would not be effected, and that he was well on the way to recovery. No bodies were ever recovered of the other 34 men of the ship's complement.

S.S. Wollongbar Sunk By Torpedoes (1945, November 22). Daily Examiner (Grafton, NSW : 1915 - 1954), p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article195748467

One survivor apparently remarked that “I knew the XLCR would come to rescue us”, as they also operated as the town’s rescue boat [3. Radley 2019].

This vessel still operates today out of Port Macquarie and is used as a training vessel for the Newman Senior Technical College.

The XLCR at Port Macquarie (Image B Duncan)

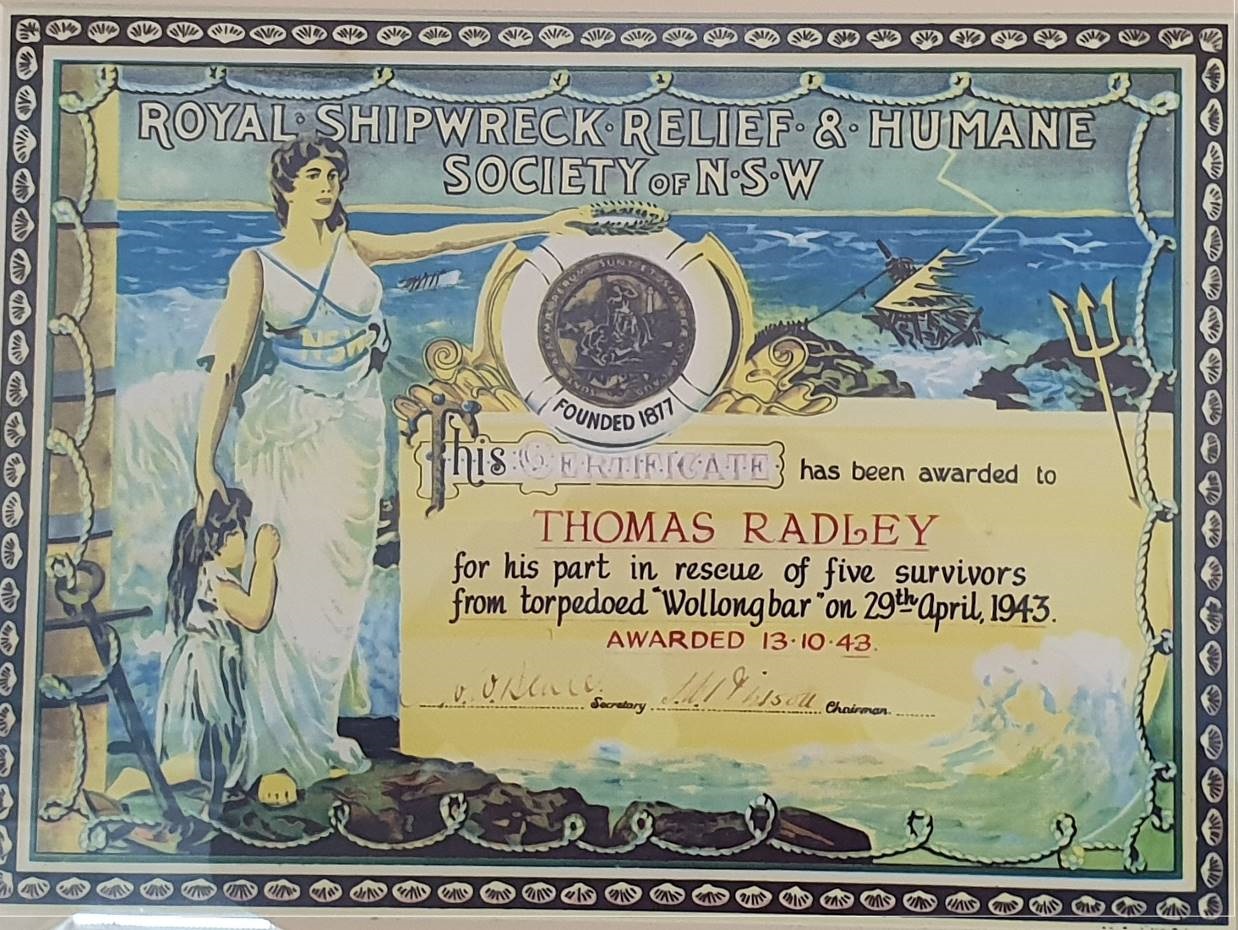

The Captain and crew of the vessel (father Capt. Thomas Radley and brothers’ Claude, Mervyn and Russell, along with Arthur Beattie and Raymond Smith) were all awarded Bravery Certificates by the Royal Shipwreck Relief and Humane Society of NSW for their efforts in rescuing the survivors despite the grave peril they placed themselves in by doing so [2.].

LOSS OF WOLLONGBAR

AWARDS FOR FISHERMEN Port Macquarie Men

Connected with the sinking of the steamer Wollongbar off the mid-rivers coast recently, the enclosed copy of a letter received by Major J. B. Shand, MLA, representing Major G. D. Mitchell. MLA, during his absence on active service, relates to a resolution presented to His Excellency the Governor, Lord Wakehurst, during his visit to the electorate on July 4 last, who forwarded to the Premier an account of the action of Mr. Thos. Radley and his crew and their courageous effort in rescuing five members of the crew of a steamer torpedoed off Port Macquarie.

"Following upon my letter of 6th August regarding your personal representations on behalf of Mr. Thomas Radley and the members of his boat's crew who were reported to have performed a courageous act, I desire to advise you that, following the completion of the necessary inquiries, the Premier forwarded all available particulars to the Prime Minister of the Commonwealth with the view of consideration being given to the question of taking action for the appropriate recognition of the above mentioned act. The Premier has now been advised by the Prime Minister that he will be glad to consider the cases of the boat's crew with a view to recording their names in the register kept in his Department, or granting some form of award, if such is found to he justified, in recognition of their brave conduct. Particulars of the above case have been forwarded to the secretary of the Royal Shipwreck Relief and Humane So-ciety of NSW, who has advised that the matter will receive the attention of the council of the Society at its October meeting.— Yours faithfully, J. W. Ferguson, Under Secretary, Premier's Department.'' LOSS OF W0LLONGBAR (1943, October 5). Macleay Argus (Kempsey, NSW : 1885 - 1907; 1909 - 1910; 1912 - 1913; 1915 - 1916; 1918 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article234408968

Bravery certificate presented to the Master of the XLCR Thomas Radley

Wreck site description

[2.]

The wreck shows signs of extensive torpedo damage forward of the bridge and at the stern just aft of the steam engine (behind the aft funnel). The stern section appears to be lying in pieces at a 90-degree angle to the rest of the vessel. The upper decks appear to have been blown upwards as a result of the blast and collapsed back into the hull of the vessel.

The wreck is in very poor condition, with only sections of the midships and bow remaining partially intact. It is home to a previously unknown colony of critically endangered Grey Nurse Sharks.

Bow and Grey Nurse Shark (Image: AUS ROV)

Protection

The wreck and any associated human remains are protected by the Commonwealth Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018, with the wreck site managed by Heritage NSW, Sydney. The remains of any human remains are also protected under the NSW Coroners Act 2009.

The site is a significant place of loss and should be treated with respect for those killed in the incident.

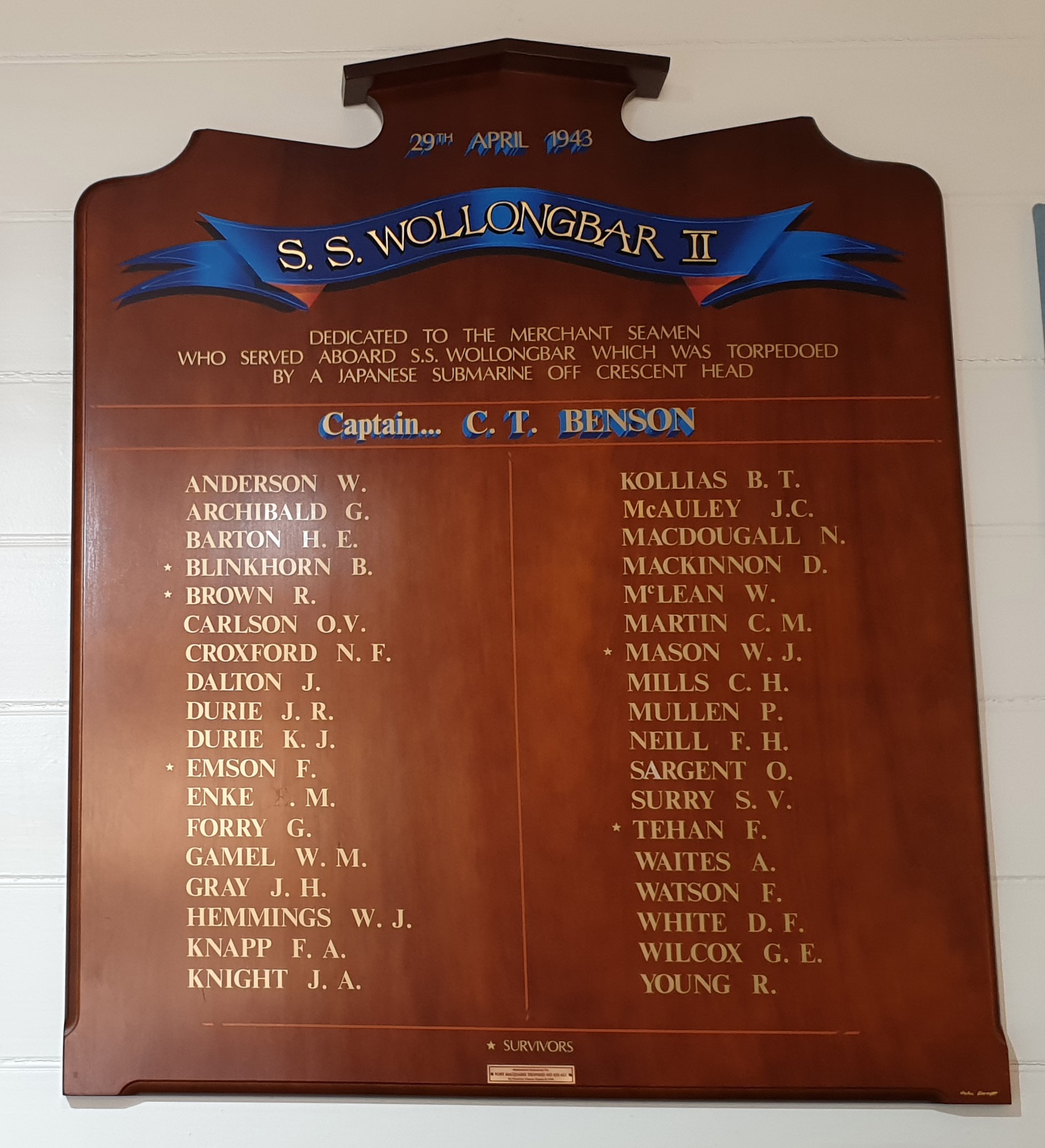

SS Wollongbar II Honour Roll - image supplied

Wollongbar II. Wreck Footage

Discovery of historic shipwreck SS Wollongbar II.

A coastal freighter torpedoed by a Japanese submarine in WWII has been discovered off Crescent Head in the state’s Mid North Coast. Acting NSW Minister for Veterans Geoff Lee said the SS Wollongbar II was confirmed by archaeologists from Heritage NSW after it was reported by the local community.

In 2019, the wreck’s accurate location was reported by Port Macquarie mariners although had been generally known of years prior. Heritage NSW, Department of Premier and Cabinet, undertook the first-ever archaeological inspection of the site in late 2019. This included cutting-edge multibeam and side scan surveys, and the deployment of a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) to inspect and photograph the deep site. The survey confirmed the wreck as Wollongbar II. Survey operations were assisted by AUS ROV and Fish Port Macquarie.

References And Extras

- The sinking of the Wollongbar II. AWM. At: https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/stories-service/australians-war-stories/sinking-wollongbar-ii

- Wollongbar II (1922-1943). Shipwreck information Sheet. Tim Smith OAM and Dr Brad Duncan, Heritage NSW, Sydney. From: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/-OEH/ wollongbar-2-shipwreck-information

- Radley, Cec, 2019, Interview by Brad Duncan 26 Sept 2019, Port Macquarie.

- Port Macquarie Historical Society and Port Macquarie Museum.

James Alfred Knight, late of s.s. "Wollongbar" and Vaucluse, in the State of New South Wales, donkeyman, who became missing on 29th April, 1943, and is for official purposes presumed to be dead, intestate. RE the estates of the undermentioned deceased per (1943, September 3). Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 2001), p. 1571. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article225081786

CARLSON - In loving memory or my darling husband, William, who lost his life on S.S. Wollongbar. April 29. 1943. Gone, but not forgotten by his loving wife, Helen, sons, Hughie, Peter, Ken, and daughter, Lea.

KNAPP.-In loving memory of our dear husband and father. Frederick Arthur Knapp. (M.N.), who lost his life at sea through enemy action. April '29, 1943. Also his shipmates. Inserted by his loving wife, son, and relatives.

KNIGHT.—In loving memory of my darling husband, (Jim), James Alfred (Merchant Navy), who was lost at sea by enemy action, April 29, 1943. Ever remembered by his loving wife, Mary, and devoted daughters, Patricia, Georgina.

KNIGHT.—Sad thoughts to-day for Jimmy, who lost his life at sea April 29, 1943, S.S. Wollongbar. Always remembered by his loving mother, brothers, and sisters. Also a tribute to his shipmates.

KOLLIAS.-Deep in my heart a memory is kept of my beloved and adored youngest son, Brian M.N.. lost at sea April 29. 1943. Never to be forgotten by his loving mother.

KOLLIAS.-Cherished memories of our beloved youngest brother. Brian (M.N.), lost April 29. 1943. Deeply mourned by Norm and Edna (Perth), Jack and Leonie.

KOLLIAS.-Treasured memories of our beloved brother, Brian, M.N., lost April 29, 1943. Deeply mcurncd by Murielle and Harry

McLEAN.-In loving memory or our dear brother-in-law. William, who lost his life on the S.S. Wollongbar April 29, 1943. Always remembered by Mary and Nell and family. Family Notices (1946, April 29). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 14. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17978173

ROLL OF HONOUR

DURIE.— In loving memory of James Durie and son, Kenneth, lost on S.S. "Wollongbar," 29th April. 1943.

"Too dearly loved ever to be forgotten."

Inserted by Charles and Rona, Mrs. Dartnell and Betty.

GAMEL. — In loving memory of Bill, lost on S.S. "Wollongbar," 29th April, 1943.

"I shall never lose sweet memories of the one I loved so much."

Inserted by Betty.

Family Notices (1948, April 30). Northern Star (Lismore, NSW : 1876 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article225790162

Butter from the Sea after 11 Years: — When the North Coast S. S. Co's Wollongbar was torpedoed off Port Macquarie during the war nearly 11 years ago, great quantities of butter came ashore and local residents retrieved numbers of cases up and down the coast.

Another case came ashore at Point Plomer in the heavy seas recently.

The weather had apparently freed the butter from the ill-fated ship or from the sea bottom. The pine casing had disappeared and in place was a particularly hard shell like marine growth, and the butter was 'as hard as a rock'. Though it had a slight smell, the butter was in an excellent state of preservation. HERE AND THERE (1954, March 11). Raymond Terrace Examiner and Lower Hunter and Port Stephens Advertiser (NSW : 1912 - 1955), p. 1. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article134641405

HISTORY

The end of a pocket liner

It was a wartime sinking on the NSW coast kept secret from, the enemy and the general public.

By. J. H. ADAMS

AUSTRALIANS heard many vague rumors about ship sinkings off the coast during the earlier, tense years of World War II. Some were false, some were true and one of the latter was that concerning the popular coastal passenger ship Wollongbar.

The Wollongbar went down about 10.30 am on April 29. 1943, after being hit by two torpedoes fired from a Japanese submarine, almost on the front doorstep of Sydney. The ship sank 10 miles off Crescent Head, on the NSW North Coast with heavy loss of life. Censorship was so tight at the time, that even today few know the details of the tragic loss of this well-known "pocket liner".

The Wollongbar went down on a route she had traversed a thousand times. That her sinking occurred after she had diverted from her course earlier to assist another torpedoed ship only added to the tragedy of the loss, only live out of 37 surviving.

The other torpedoed ship was the big motor vessel Limerick, which had been in dock in Sydney undergoing extensive alterations to fit her for more important war service. Her refrigerated space had been expanded at a cost of £130,000. The Limerick was the rear ship in a northbound convoy when hit by a Japanese torpedo at 1 am on April 25. 1943. while between 20 and 30 miles off Evans Head on the North Coast.

Those were dark days off the eastern coast of Australia, with the enemy on the rampage and our protective naval screen still thin.

The Japanese torpedo started a fire on the Limerick. At first there was a chance of saving her but a heavy sea and a strong wind sprang up. After four hours the fire spread so alarmingly that most of the men had to jump for it. Of a crew of 71, two were lost and the survivors, after eight hours in the water, were picked up by a corvette.

A distress call

When the Limerick was hit, she succeeded in sending out a radio distress call. At the time the Wollongbar was on her way from Sydney to Byron Bay and diverged from her course to search for survivors from the Limerick. She spent some time on the search and was delayed in arriving at Byron Bay, where she was to load cargo at the jetty in the open road stead.

Had she ignored the distress call, the submarine might have missed her and it is probable that she would have steamed through the danger area in the dark.

The Wollongbar left Byron Bay on the night of April 28. The next morning broke fine and clear and the trim vessel was making good speed.

At 10.30 am the enemy struck eight to 10 miles off Crescent Head, north of Port Macquarie.

Crew men saw the first torpedo speeding toward them but they could do nothing about it. It exploded just forward of the bridge followed by a second just abaft the engine-room. The steamer broke in two and sank in two minutes.

Captain Charles Benson, who had been in command for nine years, was on the bridge. He was lost. A survivor, Royston Browne, 37, of Riley St., East Sydney, was at the wheel. He said that the look-out man was standing by him. Suddenly he yelled: "Look" and pointed seaward.

Browne and Captain Benson followed his gaze and saw the white, streaking wake of the torpedo. There was not time to swing the Wollongbar clear and as the captain shouted to them to look after themselves, the first explosion shook the ship.

Browne said he saw Captain Benson grab a lifebuoy and dive down the bridge ladder.

"It was the second explosion almost immediately afterward that shook me up," said Browne. "I just went over the side and when I came up I sighted a piece of wreckage and clung to it. I saw one of the seamen on a raft about 30 yards away and swam to it.

"About 300 yards further inshore we noticed two men, one of them the chief officer, Mr. Mason, in a half filled lifeboat.

"On another raft we saw F. Simpson, a greaser from Sydney with two paddles. He beckoned and we began paddling. We pulled toward him and then discovered that he was badly scalded about the face, legs and chest. He had been standing by a steampipe when it had fractured.

Raft in tow

"The raft was more comfortable for him as he could stretch out. We did not attempt to move him but took his raft in tow. Our lifeboat was taking in water and was so low down in the water that we could not hoist sail and had to row.

"I was lucky to be alive in the water. As I went over the side the two sections of the Wollongbar reared on their ends into the air and I was terrified that the bow would strike me as it came down."

Able Seaman F. Teahan, of Sydney, another of the five survivors, was off watch and in his bunk. Seconds before the torpedoing he climbed out to get himself a drink of water.

As his feet hit the deck there was a violent explosion and the forecastle was filled with smoke and fumes.

He dragged off his trousers, for he knew that he would have to swim for it. As soon as he dropped into the sea he felt himself being dragged under by the suction of the sinking ship but fighting against it desperately he reached a raft.

The escape of Fireman B. Blinkhorn, also of Sydney, was amazing. He was in the stokehold and above him was a closed steel hatch cover with a steel ladder leading up to it. The odds were loaded against him.

A powerful upsurge of air from the explosion blew off the hatch cover and Blinkhorn scrambled up the ladder, through the open hatchway, up another ladder to the boat deck and the lifeboats.

The ship was going down so rapidly that he, too, had to jump for it.

Chief Officer Mason, relieving the regular chief officer who was on holidays, was in the chief engineer's cabin, talking. He ran on deck and jumped into the sea, just missing a mass of tangled wreckage.

The second Wollongbar, the pocket coastal liner sunk during World War II

After the Wollongbar was hit, Mason said he saw the periscope and portion of the conning tower of the submarine about half a mile away on the port side for a few seconds.

Third Engineer Drury and his 16 year-old son, signed on as a deckboy, were lost. The lad had been keen to go to sea and his father, though opposed to the idea, had relented before the lad's persistent requests. The lad had not long been in the Wollongbar.

Port Macquarie residents on the beach saw the columns of spray sent up by the explosions, heard the boom-boom of the torpedoes and then saw the Wollongbar swiftly disappearing. They raised the alarm and the pilot tug in the port tried to go to the rescue. The tug made repeated efforts to cross over the bar but the seas were too heavy and it was forced back.

Five men in a motor trawler, of shallower draught than the pilot tug, succeeded in getting to sea. Although they had no great distance to travel, perhaps a little over 10 miles, they did not sight the five survivors until 4 pm on the afternoon of April 29.

The rafts and the lifeboat were low in the ocean swell and like the motor trawler, were close to water level.

End of a ship

The rescuers on the trawler were tossing cigarettes and tobacco to the survivors even before they began to haul them aboard. They had the kettle boiling and poured them steaming mugs of tea and took off some of their dry clothing to warm the wet, shivering men.

They even offered to cook meals, despite the briefness of the run Into Port Macquarie.

So ended the life of a famous little ship. She took her name from an earlier Wollongbar that had broken away from her moorings in the dangerous roadstead at Byron Bay and had run on the beach. The sands closed about her and she could not be refloated.

The second Wollongbar attracted many tourists who wanted an unusual journey to Brisbane. She used to make the passage from Sydney to Byron Bay in about 36 hours. There the tourists transshipped to cars and motor coaches for the drive through Tweed Heads, Murwillumbah, Surfers' Paradise and Southport, to Brisbane.

A surge alongside the landing jetty at Byron Bay could make life exciting for the passengers. Heavy mooring lines had to be used to hold the Wollongbar alongside and one moment her bridge would be level with the jetty's decking, and the next it would be high in the air.

When this happened the passengers would be landed or embarked, half a dozen at a time, in a big basket by an electric crane on the wharf. From the basket they often obtained an excellent bird's eye view down the funnel before being landed on the jetty or gently on the deck in front of the bridge.

The Wollongbar had a great turn of speed for a coaster. By using the warm current that runs southwards down the New South Wales coast at varying distance from the land, she was able to maintain 17 knots on most of her southbound voyages—no mean speed for a coaster.

Her chief engineer would take water temperatures after leaving Byron Bay and indicate to the captain whether he was "warm or cold" When the temperature rose the steamer was in the current and receiving assistance from it. When it dropped the captain altered course until the water temperature rose again.

She made one round voyage a week clearing Sydney Heads late on Tuesday nights.

She was a well-known identity to the crowds on Manly Beach late on Sunday afternoons as she sped southward toward the Heads, a pretty picture against summer sea and sky.

The Wollongbar had two red funnels with black tops—the traditional colors of the North Coast S.N. Co. looked much bigger than her tonnage—a fact which earned her the title "pocket liner".

It was thought, after her loss, that the Japanese believed her to be a big ship and that it was probably this belief that prompted them to expend two torpedoes upon her.

The torpedoing of the Wollongbar ended en era of comfortable sea travel along the New South Wales coast.

The Wollongbar (2239 gross tons, built in 1922) with the smaller Orara and sometimes the Pulfianbar, both older vessels, maintained the service between Byron Bay and Sydney. .

Trade decline

Coastal sea travel was on the way out before the war but the loss of the Wollongbar hastened it. At the end of the war the trade was in such a poor state that the steamer was never replaced.

Travel from Sydney up and down the North and South Coasts had existed from the days when New South Wales was merely a small colony. It reached its peak in the years before World War I and during the years between then and the outbreak of World War II.

In the few years before World War II the decline started. It was more rapid on the South Coast, but the new railway line to Brisbane was running right up the North Coast and was competing strongly in the passenger field; motor traffic was increasing and roads were improving.

The steamers of the North Coast S.N. Co. Ltd., which owned the Wollongbar, ceased carrying passengers to the river ports south of Byron Bay and new ships were cargo carriers only and had no passenger accommodation.

But they were fighting for trade, freight as well as passengers. It has proved to be a losing battle. The railway has cut into the volume of cargo of butter, cheese and farm produce. So the sinking of the Wollongbar not only sounded the knell of a picturesque and gallant little ship but also that of the once lucrative coastal trade that had grown from sluggish sailing craft to speedy steamers. HISTORY The end of a pocket liner (1954, July 31). The World's News (Sydney, NSW : 1901 - 1955), p. 19. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article133913482

DRAMATIC STORY OF WOLLONGBAR SINKING

A DRAMATIC, but little known episode of the war at sea along the Australian coast, was unfolded at the last meeting of Grafton Rotarians by Captain W. J. Mason, master of the "Uki."

It was the story of the torpedoing of the steamer Wollongbar on April 29, 1942, six miles off Crescent Head.

Of the crew of 39, only five survived. Captain Mason was one of them.

In the same fateful week, seven ships were sunk, apparently by the same Japanese submarine.

After breakfast on the day of the sinking, Captain Mason was on the bridge with the Master, Captain C. E. Benson, well-known on the Clarence River, and the Chief Engineer.

"There's a cup of tea for you in the wireless room" said the Master. Captain Mason went to get it, thinking at the time "what a shame it was that there were no biscuits.'' He had just returned to the bridge when the Chief Engineer yelled out "Look to port."

There they saw a huge splash made by a submarine as it crash-dived 300 yards away. And coming towards them were two wobbling torpedoes.

Next moment there was a violent explosion.

"Look after yourselves, boys," 'shouted the Master as he went to discharge his main responsibility—the destruction of the code. He was never seen again. Nor was the Chief Engineer.

Captain Mason clung to a sup port as the ship went down.

The next he remembers was swimming in what appeared semi darkness towards a butter box, of which 18,000 were scattered over the sea. He saw a life belt and grabbed it, but for the life of him, was unable to get into it. He had to be content with putting an arm over it.

A little later he saw a boat with what appeared to be a dead figure spreadeagled across it. He made towards it and scrambled in. The figure was that of a greaser, dreadfully burnt from the explosion of the ammonia out of the refrigeration system.

"Water, water," mumbled the greaser through his thickened lips.

A little later a huge eighteen-stone man, clad in only a singlet, and a very small companion, were seen on a raft. They joined the boat.

The party started to search for other survivors. All they could see was floating butter boxes. They then saw a man on a raft paddling slowly towards them. He was perfectly dry, apparently having been blown from the stoke-hold on to a raft. He was bewildered and semi-stunned, and he did not see the oars right in front of him.

They searched around for more survivors. An R.A.A.F. bomber circled overhead. Captain Mason made signs with his fingers and mouth for cigarettes.

At last, in exasperation, the midget survivor exclaimed: "Damn fool, he thinks we're throwing him kisses.''

The little fellow then climbed on to the shoulders of the eighteen-stoner to see if he could spot any more of their mates.

"It was a queer sight," Captain Mason said.

Then they started to row towards the beaches of Port Macquarie.

At 4.30 p.m., a launch came across them. The bomber had sent out a message for help.

The crew gave them a cup of tea.

"It was the finest drink I had in my life," said Captain Mason.

All Port Macquarie was out to see them arrive.

"Where are the rest of them," was the constant question.

The injured man was immediately taken by ambulance to hospital; the rest to a hotel.

Captain Mason spoke feelingly of the wonderful spirit of helpfulness of the women who provided them with clothing and other necessities, and of the Greek who rang up and said, "Give them every things they want and charge it up o me."

Captain Mason recalls with the utmost admiration the work of the doctor and nurses who worked ceaselessly to save the burnt man. He eventually recovered with a skin "better than, his original one."

Captain Mason was put in hospital, apparently suffering from a terrific reaction, but on June 14, he was "in harness again.''

DRAMATIC STORY OF WOLLONGBAR SINKING (1948, September 16). Daily Examiner (Grafton, NSW : 1915 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article194974914