Inbox and environment News: Issue 597

September 3 - 9, 2023: Issue 597

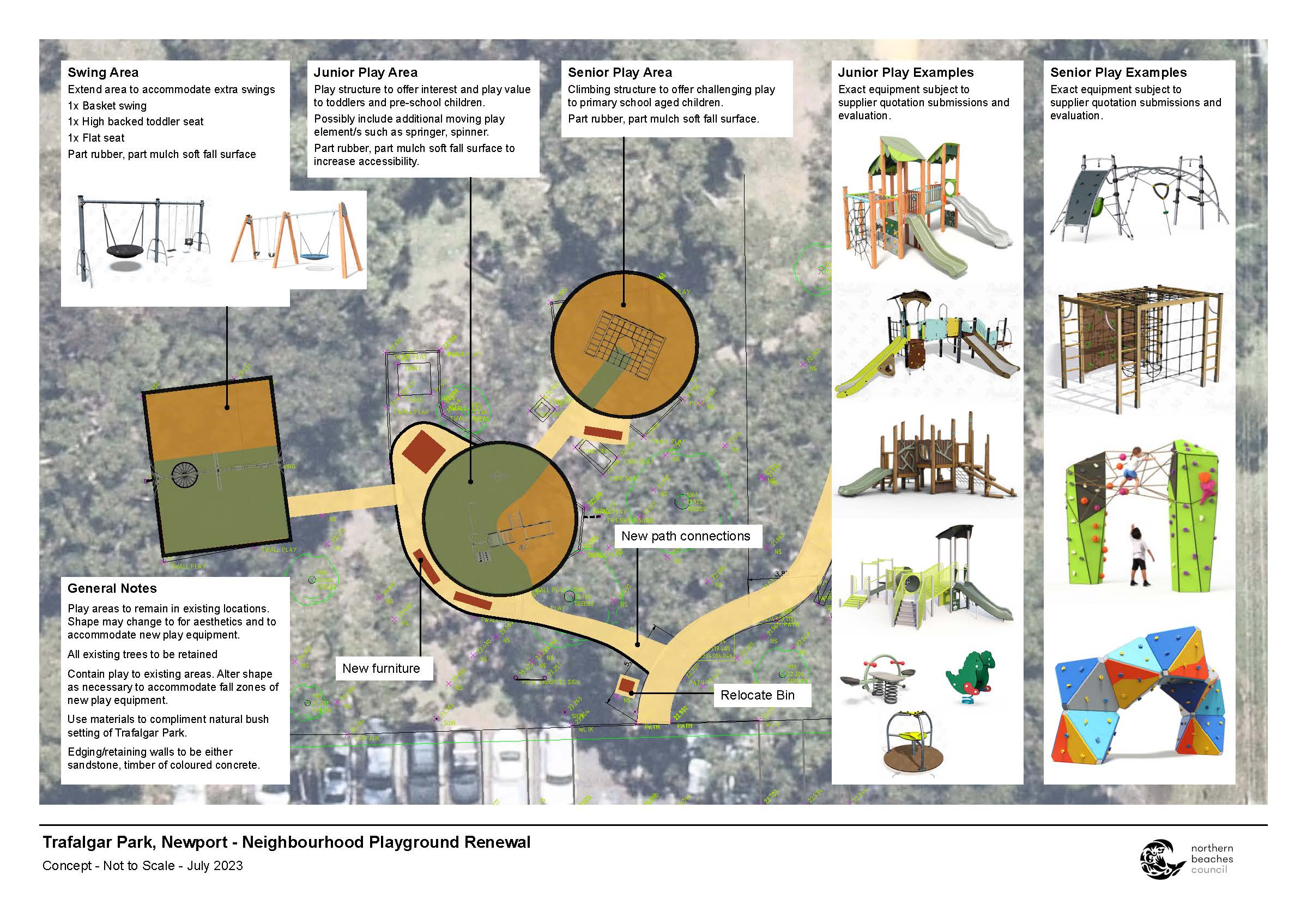

Trafalgar Park Newport: Playground Renewal - Feedback Invited

- completing the comment form here

- emailing council@northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au

- writing to council marked 'Playground renewal - Trafalgar Park, Newport’ to Northern Beaches Council, PO Box 82, Manly NSW 1655.

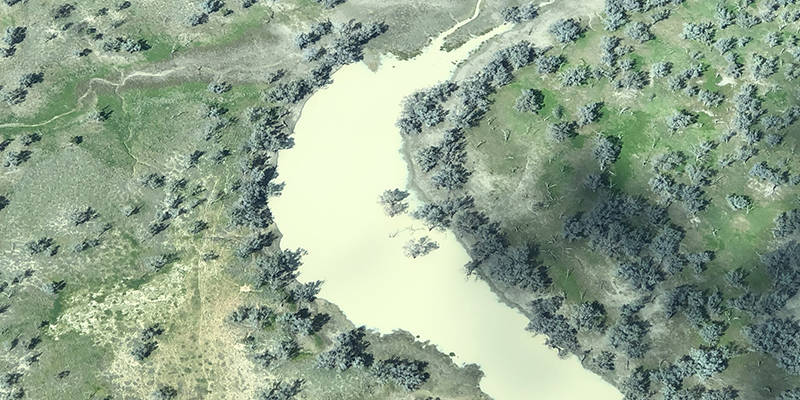

New Planting Along Careel Creek

September Is Biodiversity Month: Time To Repair, Restore, Respect Our Plants And Wildlife

- go on a Bush walk in your area,

- look out for and after our wildlife and plants

- keep a nature journal or connect with nature,

- share your observations with the iNaturalistAU community.

The Powerful Owl Project: It’s Fledging Time!

Northern Beaches Clean Up Crew: Newport Beach Clean Up - Sunday September 24

Chief Scientist Report On Mass Fish Deaths At Darling-Baaka River Near Menindee

- Explicit environmental protections in existing water management legislation are neither enforced nor reflected in current policy and operations. Water policy and operations focus largely on water volume, not water quality. This failure in policy implementation is the root cause of the decline in the river ecosystem and the consequent fish deaths.

- Low dissolved oxygen in the water column was driven by a confluence of factors, including high biomass (particularly carp and algae), poor water quality, reduced inflows and high temperature. The area around the Menindee Lakes is particularly susceptible to fish deaths events.

- Hypoxia – resulting from low dissolved oxygen in the water column - was the most likely proximate cause of fish death.

- While limited, observations and monitoring data indicated compromised water quality and potential for fish deaths prior to the March 2023 event. However, the scale of any potential event was underestimated.

- continuing our active management of flows from the Menindee Lakes to maintain dissolved oxygen at good levels for fish;

- upgrading water quality monitoring including additional remote dissolved oxygen sensors;

- exploring funding options with the Commonwealth for fish passage projects;

- improving river connectivity through actions identified in the Western Regional Water Strategy;

- updated water sharing plans and

- established an Expert Panel on connectivity in the Barwon Darling River (see below)

Video posted on FB by Graeme McCrabb, who stated; ''Unbelievable!! Menindee NSW! 17/03/2023. Nearly all native dead fish. - Bonnie Bream, Golden perch, Silver Perch, Carp but not many.

EPA Issues Stop Work Order On Forestry Operations In Tallaganda State Forest

'The Environment Protection Authority has issued Forestry Corporation a Stop Work Order for forestry operations in Tallaganda State Forest.Protecting Greater Glider habitat is crucial, and Forestry Corporation has spent many months preparing for these operations through intensive pre-harvest surveys to identify and map sensitive habitat and ecological features.During the harvesting operation Forestry Corporation ensures the habitat for gliders such as hollow bearing trees and retention clumps are protected.Forestry Corporation is fully complying with the Stop Work Order and its compliance team is on site investigating.We are fully committed to investigating what has occurred and finding out what the circumstances are around the greater glider found dead in the forest.Forestry Corporation monitors Greater Glider populations in Tallaganda State Forest and has completed over 40 kilometres of spotlight transects and identified almost 400 greater gliders across the whole forest.The Greater Gliders are occupying the range of forest landscapes across Tallaganda - areas affected by the 2019-20 bushfires and the unburnt forest, plus areas of forest which are unharvested and areas which have previously been harvested for timber.'

Logging Continues Within So-Called 'Great Koala Park' - 20% To Be Destroyed Before Koala Park Even Established Under RFA's That Run Until 2048 In NSW: Local MP's Visit, Call For Ban On Logging In NSW Forests

From 'Proposed multi-scale landscape approach – download the Multi Scale Approach Factsheet here' Doc.;COASTAL IFOA SCALE• Includes all public coastal forests in NSW and consists of over 5.2 million hectares.• Across this area of public forests is a patchwork of State Forests and forest protected in National Parks and State Flora Reserves.• State Forests make up around 30% of the public forests in the Coastal IFOA area. Native timber production forests cover around 16% of this area.Environmental protections include:• An established network of protected public land conserving important habitat and ecosystems across coastal NSW.• The broad landscape-based habitat protection network includes National parks, Flora Reserves and special management zones.• Annual timber volume caps are also set to ensure a long term ecologically sustainable supply of timber.• Reporting requirements apply and monitoring to evaluate and ensure environmental outcomes are being achieved.

MANAGEMENT ZONE SCALE• A defined geographic region with an average size of 50,000 hectares.• Multiple timber production forests occur within each management area.• These areas will be fixed and mapped at the commencement of the proposed IFOA.• On average 50% of the management zone of state forests is protected.Environmental protections include:• Annual limits on the amount of harvesting in each management area to distribute harvesting across the landscape.• A maximum of 10% of a management area can be harvested per year.• If the management area is zoned for intensive harvesting, then a maximum of only 5% of that management area can be intensively harvested per year

LOCAL LANDSCAPE AREA SCALE• A defined area of timber production forests no larger than 1500 hectares.• On average there are four local landscape areas in each State Forest.• These areas will be mapped out progressively over time.• An average of 38% is protected before the new wildlife habitat clump requirements are considered. This will increase to an average of 41%.Environmental protections include:• A minimum of 5% of the harvest area to be permanently protected as a wildlife habitat clump to maintain habitat diversity and connectivity.• Rainforest, high conservation value old growth, habitat corridors and owl habitat will continue to be protected.• Threatened ecological communities have been mapped and will be excluded from harvesting.• Streams are more accurately mapped and exclusion zones apply to provide landscape connectivity and protect waterways.• Distributes intensive harvesting across the landscape and over a minimum 21 year period.• Improved koala mapping to retain koala browse trees to support movement between areas and food resources.

SITE• A site is the area where harvesting is taking place. Sites vary in size from about 45 to 250 hectares.• There are many sites, called coupes or compartments, within each local landscape area.• An average of 41% of State Forests at a site scale will be protected, increasing to 45% with added tree retention clumps.

Environmental protections include:• Areas will be permanently protected to provide short term refuge, maintain forest structure, and protect important habitat features.• Additional areas no less than 5 – 8% of the harvest area will be permanently set aside as new tree retention clumps.• Hollow-bearing trees, nest and roost trees and giant trees will be permanently protected to provide ongoing shelter and food resources.• Some target surveys will be retained for unique species of plants and animals that require protection.• Sites will now be measured, mapped and monitored with mobile and desktop devices.

Visit: Proposed changes to timber harvesting in NSW's coastal forests - NSW Government; 'Once approved, the new Coastal IFOA will set the rules for how we use and harvest these forests so it’s important that you have your say.'In November 2018 the National Parks Association stated Freedom of information documents reveal damning assessment of Berejiklian government’s proposed new logging laws.''As the NSW and federal governments are poised to sign off on 20-year extensions to controversial Regional Forest Agreements, documents acquired by the North East Forest Alliance under freedom of information show deep concerns within the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) about the impact of new logging laws on protected old-growth, rainforest and koalas.'' NPA stated

''OEH’s concerns echo those of environment groups and illustrate clearly that the laws will destroy the natural values of our forests. Reminiscent of when Environment Minister Upton signed off on new land clearing laws despite departmental advice that 99% of koala habitat was at risk from clearing, the government is again ignoring OEH advice that koala deaths will increase and habitat quality decrease as a result of the new laws.

''Further, the documents reveal that the recommendation by the Natural Resources Commission to allow logging of forest protected as oldgrowth forest, rainforest and stream buffers for the past 20 years was contrary to the recommendations of the Expert Fauna Panel and that the Panel’s considerations of required protections were based on the erroneous assumption that all these important fauna habitats would be protected. OEH recommends many of the panel’s recommendations for threatened species need to be revisited in light of the new logging proposals..

On top of recent revelations about the deep unpopularity of native forest logging in the broader community, the National Parks Association (NPA) and North East Forest Alliance (NEFA) are calling for the government to scrap the new laws (called Integrated Forestry Operations Approvals) and chart an exit out of native forest logging.

“The documents show that a keystone of Premier Berejiklian’s draconian changes to the logging rules for public forests is that some 58,600 ha of High Conservation Value Oldgrowth and 50,600 ha of rainforest in north-east NSW may be made available for logging”, said Dailan Pugh of the North East Forest Alliance.

“These forests were protected over 20 years ago as part of NSW’s reserve system because they are the best and most intact forest remnants left on state forests. As logging intensity has increased around them their environmental importance has escalated.

“North East NSW’s forests are one of the world’s centres of biodiversity and now Premier Berejiklian wants to extend her increased logging intensity into the jewels that the community saved.”

Dr Oisín Sweeney, Senior Ecologist with the National Parks Association of NSW (NPA) said: “It’s no wonder the public is sick of native forest logging and that it has lost its social license.

“Here we have clear warnings from OEH that more koalas will die and more koala habitat will be lost. Yet the government’s determined to plough on regardless.

“It’s past time the federal government intervened to stop NSW knowingly driving koalas further towards extinction.”

________________

Extracts from NSW Office of Environment and Heritage Conservation and Regional Delivery Division North East Branch (NEB) ‘Submission to the NSW Environmental Protection Agency on the Draft Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval remake’ obtained through freedom of information

The Draft Coastal IFOA appears to enable boundaries separating the CAR reserve system and the harvest area to be amended by inter‐agency agreement with no public consultation. Further, amendments to the boundaries could occur at the scale of the local landscape or even individual compartment. Areas would be assessed in isolation, rather than at a regional scale, and thereby be susceptible to the incremental ecological impact that regional assessments were originally introduced to prevent. This is expected to significantly compromise the CAR reserve system over time.…

The NEB therefore reiterates the recommendation from the Expert Fauna Panel for the ‘permanent protection of current exclusion zones’ (State of NSW and the Environmental Protection Agency 2018, p.8) and recommends that the Draft Coastal IFOA include specific provisions that protect all areas that have been protected by the FA, RFA and current IFOA over the last 20 years.

Intensive and selective harvest areas

The CAR reserve system was established in conjunction with selective logging regimes that maintained structurally diverse forest throughout the harvest area. The Draft Coastal IFOA appears to increase the area of public forests on the north coast that would be legally available for intensive harvest, with the risk that large areas of forest will be reduced to a uniform young age class that would take many decades for full ecological function to be restored.

In the intensive harvesting zone (the Coastal Blackbutt forests of the north coast hinterland), the Draft Coastal IFOA proposes to allow coupes of up to 45 ha to be logged with no lower limits on the number of trees retained in the harvest area.

…

This proposed minimum basal area retention of trees in the harvest areas is below the minimum threshold required to maintain habitat values advised by the majority of the Expert Fauna Panel.

The Draft Coastal IFOA proposes removing the existing requirement to protect habitat ‘recruitment trees’. Over time, this will reduce the number of large habitat trees retained for ecological purposes in harvest areas, as trees die and are not replaced. Recruitment trees identified previously will now be available for harvesting, further reducing the persistent availability of larger trees as a critical habitat element for threatened and protected fauna.

High Conservation Value (HCV) Old Growth

HCV old growth was identified for protection as part of the CAR reserve in 1998. It was comprised of older forest (mapped as ‘candidate’ old growth) that also scored highly for irreplaceability (a measure of significance to biodiversity conservation) and threatened species habitat value. Under the Draft Coastal IFOA, biodiversity values of harvest area will be reduced as the area becomes progressively younger (potentially 21 years old or less). For threatened species, this places greater significance on adequately protecting existing HCV old growth areas.…

The NEB recommends that areas of HCV old growth that have been protected for at least 20 years (NRC 2018) are not made available for logging. This will minimise impacts on threatened species.

Rainforest

The concerns raised above in relation to the treatment of old growth under the Draft Coastal IFOA also apply to protected rainforest. Combined, HCV old growth and rainforest form the cornerstone of the CAR reserve system on State forest. Adequate retention of these vegetation types is considered particularly critical in the context of proposed increased logging intensities.

Specific threatened species conditions

Identifying the species that required species‐specific conditions was a major task for the Expert Fauna Panel. However, the Panel’s deliberations occurred prior to the proposals to allow logging access to HCV old growth and rainforest (NRC 2018). Therefore, many of the panel’s recommendations need to be revisited in light of the new logging proposals. For example, some of the old growth dependent species (such as those that require hollows) were considered not to require species‐specific conditions because the existing HCV old growth was protected. Similarly, for many rainforest‐dependent species, and those dependent upon riparian habitats, species‐specific conditions were not proposed on the assumption that the habitat of these species was considered sufficiently protected.

Koala protection

There appears to be a reduction in protections offered to koalas under the Draft Coastal IFOA. Koalas are selective both in their choice of food tree species and in their choice of individual trees. The scientific basis for proposed tree retention rates in the Draft Coastal IFOA is not clear, and the rates are less than half those originally proposed by the Expert Fauna Panel.

While Koalas will use small trees, research has shown that they selectively prefer larger trees. In our experience, the proposed minimum tree retention size of 20cm dbh will be inadequate to support koala populations and should be increased to a minimum of 30cm dbh. Many Koala food trees are also desired timber species, so there is a high likelihood that larger trees will be favoured for harvesting, leaving small retained trees subject to the elevated mortality rates experienced in exposed, intensively‐logged coupes.

Koalas require large areas of connected habitat for long‐term viability. The increased logging intensity proposed under the draft Coastal IFOA is expected to impact Koalas through diminished feed and shelter tree resources. Animals will need to spend more time traversing the ground as they move between suitable trees that remain, which is likely to increase koala mortality.

At the same time this video was released:

''As the NSW and federal governments are poised to sign off on 20-year extensions to controversial Regional Forest Agreements, documents acquired by the North East Forest Alliance under freedom of information show deep concerns within the Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) about the impact of new logging laws on protected old-growth, rainforest and koalas.'' NPA stated

''OEH’s concerns echo those of environment groups and illustrate clearly that the laws will destroy the natural values of our forests. Reminiscent of when Environment Minister Upton signed off on new land clearing laws despite departmental advice that 99% of koala habitat was at risk from clearing, the government is again ignoring OEH advice that koala deaths will increase and habitat quality decrease as a result of the new laws.

''Further, the documents reveal that the recommendation by the Natural Resources Commission to allow logging of forest protected as oldgrowth forest, rainforest and stream buffers for the past 20 years was contrary to the recommendations of the Expert Fauna Panel and that the Panel’s considerations of required protections were based on the erroneous assumption that all these important fauna habitats would be protected. OEH recommends many of the panel’s recommendations for threatened species need to be revisited in light of the new logging proposals..

On top of recent revelations about the deep unpopularity of native forest logging in the broader community, the National Parks Association (NPA) and North East Forest Alliance (NEFA) are calling for the government to scrap the new laws (called Integrated Forestry Operations Approvals) and chart an exit out of native forest logging.

“The documents show that a keystone of Premier Berejiklian’s draconian changes to the logging rules for public forests is that some 58,600 ha of High Conservation Value Oldgrowth and 50,600 ha of rainforest in north-east NSW may be made available for logging”, said Dailan Pugh of the North East Forest Alliance.

“These forests were protected over 20 years ago as part of NSW’s reserve system because they are the best and most intact forest remnants left on state forests. As logging intensity has increased around them their environmental importance has escalated.

“North East NSW’s forests are one of the world’s centres of biodiversity and now Premier Berejiklian wants to extend her increased logging intensity into the jewels that the community saved.”

Dr Oisín Sweeney, Senior Ecologist with the National Parks Association of NSW (NPA) said: “It’s no wonder the public is sick of native forest logging and that it has lost its social license.

“Here we have clear warnings from OEH that more koalas will die and more koala habitat will be lost. Yet the government’s determined to plough on regardless.

“It’s past time the federal government intervened to stop NSW knowingly driving koalas further towards extinction.”

________________

Extracts from NSW Office of Environment and Heritage Conservation and Regional Delivery Division North East Branch (NEB) ‘Submission to the NSW Environmental Protection Agency on the Draft Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval remake’ obtained through freedom of information

The Draft Coastal IFOA appears to enable boundaries separating the CAR reserve system and the harvest area to be amended by inter‐agency agreement with no public consultation. Further, amendments to the boundaries could occur at the scale of the local landscape or even individual compartment. Areas would be assessed in isolation, rather than at a regional scale, and thereby be susceptible to the incremental ecological impact that regional assessments were originally introduced to prevent. This is expected to significantly compromise the CAR reserve system over time.…

The NEB therefore reiterates the recommendation from the Expert Fauna Panel for the ‘permanent protection of current exclusion zones’ (State of NSW and the Environmental Protection Agency 2018, p.8) and recommends that the Draft Coastal IFOA include specific provisions that protect all areas that have been protected by the FA, RFA and current IFOA over the last 20 years.

Intensive and selective harvest areas

The CAR reserve system was established in conjunction with selective logging regimes that maintained structurally diverse forest throughout the harvest area. The Draft Coastal IFOA appears to increase the area of public forests on the north coast that would be legally available for intensive harvest, with the risk that large areas of forest will be reduced to a uniform young age class that would take many decades for full ecological function to be restored.

In the intensive harvesting zone (the Coastal Blackbutt forests of the north coast hinterland), the Draft Coastal IFOA proposes to allow coupes of up to 45 ha to be logged with no lower limits on the number of trees retained in the harvest area.

…

This proposed minimum basal area retention of trees in the harvest areas is below the minimum threshold required to maintain habitat values advised by the majority of the Expert Fauna Panel.

The Draft Coastal IFOA proposes removing the existing requirement to protect habitat ‘recruitment trees’. Over time, this will reduce the number of large habitat trees retained for ecological purposes in harvest areas, as trees die and are not replaced. Recruitment trees identified previously will now be available for harvesting, further reducing the persistent availability of larger trees as a critical habitat element for threatened and protected fauna.

High Conservation Value (HCV) Old Growth

HCV old growth was identified for protection as part of the CAR reserve in 1998. It was comprised of older forest (mapped as ‘candidate’ old growth) that also scored highly for irreplaceability (a measure of significance to biodiversity conservation) and threatened species habitat value. Under the Draft Coastal IFOA, biodiversity values of harvest area will be reduced as the area becomes progressively younger (potentially 21 years old or less). For threatened species, this places greater significance on adequately protecting existing HCV old growth areas.…

The NEB recommends that areas of HCV old growth that have been protected for at least 20 years (NRC 2018) are not made available for logging. This will minimise impacts on threatened species.

Rainforest

The concerns raised above in relation to the treatment of old growth under the Draft Coastal IFOA also apply to protected rainforest. Combined, HCV old growth and rainforest form the cornerstone of the CAR reserve system on State forest. Adequate retention of these vegetation types is considered particularly critical in the context of proposed increased logging intensities.

Specific threatened species conditions

Identifying the species that required species‐specific conditions was a major task for the Expert Fauna Panel. However, the Panel’s deliberations occurred prior to the proposals to allow logging access to HCV old growth and rainforest (NRC 2018). Therefore, many of the panel’s recommendations need to be revisited in light of the new logging proposals. For example, some of the old growth dependent species (such as those that require hollows) were considered not to require species‐specific conditions because the existing HCV old growth was protected. Similarly, for many rainforest‐dependent species, and those dependent upon riparian habitats, species‐specific conditions were not proposed on the assumption that the habitat of these species was considered sufficiently protected.

Koala protection

There appears to be a reduction in protections offered to koalas under the Draft Coastal IFOA. Koalas are selective both in their choice of food tree species and in their choice of individual trees. The scientific basis for proposed tree retention rates in the Draft Coastal IFOA is not clear, and the rates are less than half those originally proposed by the Expert Fauna Panel.

While Koalas will use small trees, research has shown that they selectively prefer larger trees. In our experience, the proposed minimum tree retention size of 20cm dbh will be inadequate to support koala populations and should be increased to a minimum of 30cm dbh. Many Koala food trees are also desired timber species, so there is a high likelihood that larger trees will be favoured for harvesting, leaving small retained trees subject to the elevated mortality rates experienced in exposed, intensively‐logged coupes.

Koalas require large areas of connected habitat for long‐term viability. The increased logging intensity proposed under the draft Coastal IFOA is expected to impact Koalas through diminished feed and shelter tree resources. Animals will need to spend more time traversing the ground as they move between suitable trees that remain, which is likely to increase koala mortality.

At the same time this video was released:

These Two Koalas Lost Their Mothers To Deforestation

The 20 year extension was approved months before the July 2019 bushfires which, by January 2020, had consumed thousands of hectares of bushland and killed an estimated 2 billion native animals.

The licence to persist in logging habitat, until 2048, is now viewed as a licence for extinction.

However the new and current State Government has already signalled it has no intention of making any changes to logging practices in the state.

Forestry Corporation NSW plans show that over the next 12 months it intends to log 30,813 hectares of a total 175,000 hectares of state forests that fall within the boundaries of the proposed Great Koala National Park, home to one in five of the state’s surviving koalas.

This would include areas identified by the government as the most important koala habitat in the state at Wild Cattle Creek, Clouds Creek, Pine Creek and in the Boambee State Forests.

“[Forestry Corporation NSW] knows this national park is coming, and they are deliberately ramping up operations within its boundaries to extract as much timber from it as possible,” NSW Nature Conservation Council chief executive Jacqui Mumford said earlier this year.

“The NSW government committed to protecting koalas by creating the [Great Koala National Park], but before the assessment process even begins, Forestry Corporation plans to log nearly 20 per cent of the park.”

The calls for a moratorium on logging by the state-owned enterprise come as Victoria announced it will bring forward an end to all logging in its state forests to 2024 from 2030, bringing that state into line with Western Australia.

“Victoria and Western Australia are now both ending native forest logging by 2024, while Queensland is stopping logging south of Noosa by next year. NSW is now the laggard in this space, and it’s time for the NSW government to step up,” Mumford said.

Both major parties in NSW have long resisted calls to end logging in native forests despite the industry running at a loss.

The proposed national park would link together and protect existing national parks and state forests and add other critical habitats from South West Rocks, north of Coffs Harbour, to Woy Woy, in the south, and areas inland over parts of the Great Dividing Range.

Responding to questions from the Sydney Morning Herald, NSW Environment Minister Penny Sharpe did not address calls for a moratorium but reiterated her government’s commitment to create the Great Koala National Park during its first term.

“We were very clear at the election that the process to establish the park will involve seeking scientific advice, consulting with all stakeholders, and will include an independent economic assessment of the park’s impact on local jobs and communities,” she said.

“The park will include 140,000ha of existing reserves and the assessment of 176,000ha of state forest for inclusion in the park.”

Mumford said it was “ridiculous” that the government was spending $29 million of taxpayers’ money to log koala habitat at a loss while spending additional taxpayer funds to protect the koala.

During the 2021-22 financial year, the hardwood division of Forestry Corporation NSW, which is responsible for native forest logging, ran at a loss of $9 million, following a loss of $20 million the previous year, according to an analysis by the Nature Conservation Council.

A report published in April by conservative think tank The Blueprint Institute also found native forest logging in NSW ran at a loss and said the government would save taxpayers $45 million by shutting down that sector of the industry in the forthcoming year rather than when current forestry agreements expire, or whenever there is no single tree left standing - whichever comes first.

It is a requirement of the NSW Regional Forest Agreements (RFAs) that its performance is reviewed every five years.

On 23 November 2022, officials from the Australian and New South Wales governments held their fourth annual meeting since the signing of the 20-year extension to the NSW RFAs. The governments issued the following communique:- Officials discussed the Long-term Ecologically Sustainable Yield review in response to the 2019-20 bushfires, the impact on wood supply, and the upcoming Sustainable Yield review due in 2024.

- Officials discussed research priorities and recent developments for forest-related monitoring, evaluation and reporting in NSW. An update was provided by the NSW Natural Resources Commission on the progress of the NSW Forest Monitoring and Improvement Program – 2019 – 2024. An update was also provided by NSW officials on the Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting (MER) Plan as required under the RFAs, as well as the development of a MER framework for PNF. Officials also discussed identifying future research gaps for RFA 5-yearly review reporting.

- Officials discussed conservation advice and recovery plans, particularly for species listed as Matters of National Environmental Significance and an update was provided on federal koala conservation programs. Officials discussed compliance activities for a range of forest management matters including for the Integrated Forestry Operations Approvals and for the PNF Codes.

- Officials considered preparations for the five yearly review in 2024, as required by clauses 8A and 8B of the NSW RFAs. This included a proposed structure for the outcomes focused Progress Report, arrangements to finalise the draft Scoping Agreement, a draft Joint Communications Plan and a proposed timeline for the review through to the end of 2024.

- Officials noted that the next annual meeting is required to be held no later than 28 November 2023 and agreed to meet before that date.

- Officials discussed the Long-term Ecologically Sustainable Yield review in response to the 2019-20 bushfires, the impact on wood supply, and the upcoming Sustainable Yield review due in 2024.

- Officials discussed research priorities and recent developments for forest-related monitoring, evaluation and reporting in NSW. An update was provided by the NSW Natural Resources Commission on the progress of the NSW Forest Monitoring and Improvement Program – 2019 – 2024. An update was also provided by NSW officials on the Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting (MER) Plan as required under the RFAs, as well as the development of a MER framework for PNF. Officials also discussed identifying future research gaps for RFA 5-yearly review reporting.

- Officials discussed conservation advice and recovery plans, particularly for species listed as Matters of National Environmental Significance and an update was provided on federal koala conservation programs. Officials discussed compliance activities for a range of forest management matters including for the Integrated Forestry Operations Approvals and for the PNF Codes.

- Officials considered preparations for the five yearly review in 2024, as required by clauses 8A and 8B of the NSW RFAs. This included a proposed structure for the outcomes focused Progress Report, arrangements to finalise the draft Scoping Agreement, a draft Joint Communications Plan and a proposed timeline for the review through to the end of 2024.

- Officials noted that the next annual meeting is required to be held no later than 28 November 2023 and agreed to meet before that date.

Investigation Underway Into Vandalism At Pelican Island Nature Reserve: Brisbane Water

$6.7 Million Tomaree Coastal Walk To Showcase Port Stephens' Natural Beauty And Boost Regional Tourism

September 1, 2023

September 1, 2023Water Careers Showcase To Lure Bright Minds

Panel To Review Barwon Darling Connectivity

The NSW Government has set up an independent expert panel to provide feedback on work being carried out to improve connectivity and flows in the Barwon Darling.

The NSW Government has set up an independent expert panel to provide feedback on work being carried out to improve connectivity and flows in the Barwon Darling.- Ms Amy Dula - Chair (Director of Programs Natural Resources Commission)

- Professor Phil Duncan (First Nations representative, Galambany Professional Fellow, Acting CEO, EPIC CRC)

- Dr Mark Southwell (Principal River Scientist, 2rog Consulting)

- Dr Phil Townsend (Senior Economic Analyst)

- Mr Cameron Smith (Principal Water Engineer, Cleah Consulting)

- Professor Fran Sheldon (Head of the School of Environment and Science at Griffith University).

Smoke In Air-On Horizon - Red Sunsets Already: August 23-24, 2023

- Keep doors and windows closed to prevent smoke entering homes

- Keep outdoor furniture under cover to prevent ember burns

- Retract pool covers to prevent ember damage

- Remove washing from clotheslines

- Ensure pets have a protected area

- Vehicles must slow down, keep windows up, turn headlights on

- Sightseers must keep away from burns for their own safety

- If you have asthma or a lung condition, reduce outdoor activities if smoke levels are high and if shortness of breath or coughing develops, take your reliever medicine or seek medical advice

Get Ready Weekend 2023: Know Your Risk This Bush Fire Season

Murray Cod And Murray Crayfish Season Comes To A Close For 2023

Australian Bass And Estuary Perch Open Season Now Officially Underway

NSW EPA Invites Feedback On How Biosolids Are Managed

Sydney To Host World's First Global Nature Positive Summit

- transparency and reporting – you can’t manage what you don’t measure

- investment in nature – growing business demand

- partnerships and capacity development – increasing landholder participation

Integrating Displaced Populations Into National Climate Change Policy And Planning - Policy Brief

August 30, 2023: UN

August 30, 2023: UN- Integrating human mobility, including displacement, in the policies and plans of ministries and agencies responsible for climate, environment, energy and development.

- Integrating climate, environment and development, in human mobility and displacement policies, planning and implementation.

‘Coastal Residents United’ Launched: New Alliance Of Community Groups Fighting Inappropriate Development

- Bonny Hills Progress Association

- Broulee Mossy Point Community Association

- Burradise - Don’t go changin’

- Byron Bay Vision

- Byron Residents’ Group

- Callala Environmental Alliance

- Chinderah District Residents Association Inc

- Clarence Environment Centre

- Clearency Valley Conservation Coalition

- Clarence Valley Watch Inc

- Concerned Citizens of Harrington

- Culburra Residents and Ratepayers Action Group

- Dalmeny Matters

- Friends of CRUNCH

- Hallidays Point Community Action Group

- Iluka DA Have Your Say

- Keep Yamba Country

- Kingscliff Ratepayers and Progress Association Inc

- Lake Wollumboola Protection Association

- Manyana Matters

- Our Future Shoalhaven

- Protect Coila Lake’s fragile ecosystem

- Red Rock Preservation Society

- Red Rock Village Community Association

- Save Callala Beach

- Stop the Fill Yamba

- Tumbulgum Community Association Inc

- Tura Beach Biodiversity Group

- Tuross Head Progress Association

- Valla Beach Community Association

- Valley Watch - Yamba

- Voices of South West Rocks

- Yamba Community Action Network

- Save Myall Road Bushland

NSW Government Adds Additional Housing Supply In Former Bega TAFE Site

- Implemented planning reforms to expedite the delivery of more housing as building more homes is essential to reducing homelessness;

- Extended temporary accommodation from an initial period of two days to seven days;

- Removed the 28-day cap ensuring vulnerable people are able to access support when they need it most;

- Increased the cash assets limit from $1,000 to $5,000 when assessing eligibility for Temporary Accommodation;

- Removed the cash asset limit assessment entirely for people escaping domestic and family violence;

- Extended Specialist Homelessness Services contracts for two years, to 30 June 2026;

- Appointed a Rental Commissioner to work with us in designing and implementing changes that rebalance the rental market, making it fairer and more modern; and

- Put a 12-month freeze on the requirement for people in temporary accommodation to complete a Rental Diary, while the scheme is reviewed.

Have Your Say On Harbourside Redevelopment At Darling Harbour

- Widening and upgrades to the Waterfront Promenade;

- Embellishments to the building’s interface with Darling Drive;

- Fit-out and use of public elements of the building, including the Bunn Street Steps through- site link, Waterfront Steps, Pyrmont Bridge Steps, and Waterfront Garden;

- Embellishment of the North and South Walks;

- Construction and operation of the new Bunn Street pedestrian bridge, and embellishments to the existing Murray Street pedestrian bridge; and

- Opportunities for heritage interpretation and public art.

New Immersive 'Digital Doorway' Makes The Border Ranges Accessible From Home

One-Year Ban For Bulk Coal Carrier For Appalling Treatment Of Seafarers

Saving Native Species Grants

- 22 Birds

- 21 Mammals

- 9 Fish

- 6 Frogs

- 11 Reptiles

- 11 Invertebrates

- 30 Plants

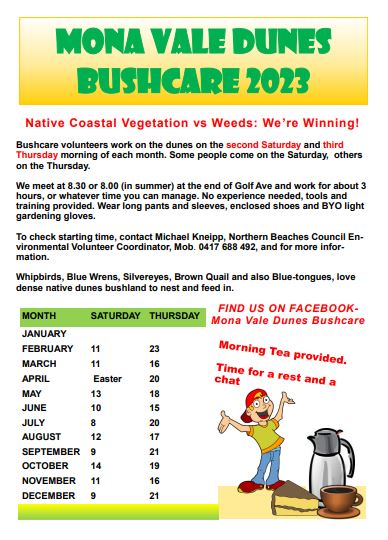

Bushcare Training Day At North Narrabeen

- Weed identification and best practice removal techniques

- Native plant identification and weed species including lookalikes

- Hands-on weed removal

- Bring along your unknown plant species for identification

Palmgrove Park Avalon: New Bushcare Group Begins

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

Palmgrove Park Avalon is a remnant of the Spotted Gum forest that was once widespread on the lower slopes of the Pittwater peninsula. This bushland’s official name and forest type is Pittwater and Wagstaffe Endangered Ecological Community, endangered because so much has been cleared for suburban development. Canopy trees, smaller trees and shrubs, and ground layer plants make up this community. Though scattered remnant Spotted Gums remain on private land, there is little chance of seedlings surviving in gardens and lawns. More information HERE

2023 Banksia Foundation NSW Sustainability Awards Open For Nominations

Stony Range Spring Festival 2023: Sunday September 10

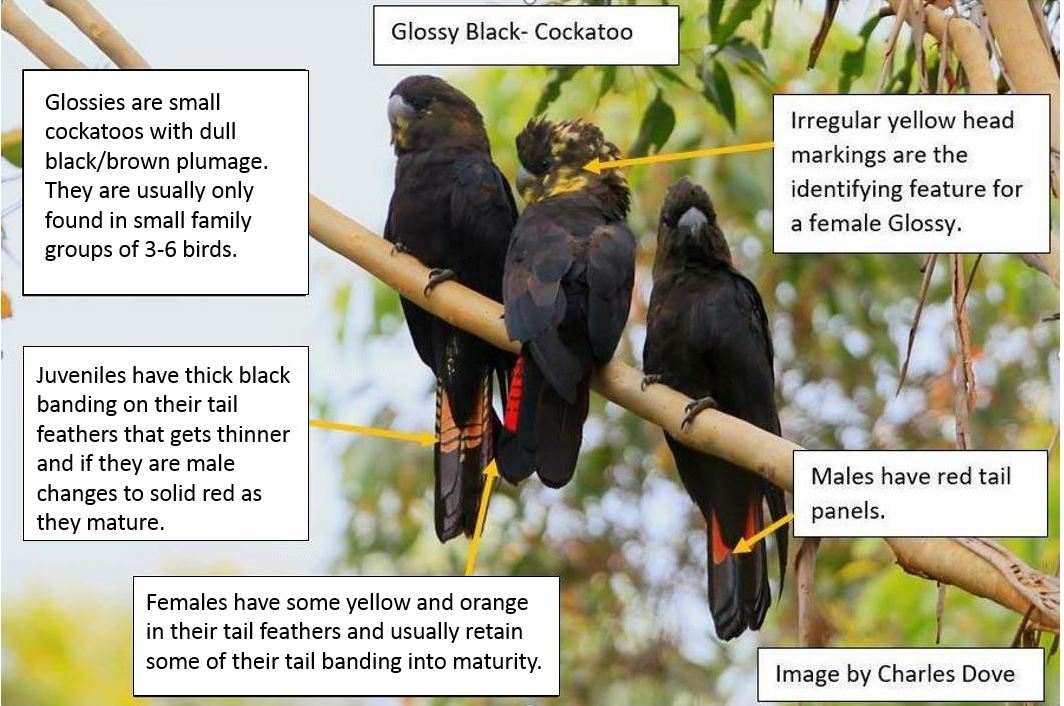

Seen Any Glossies Drinking Around Nambucca, Bellingen, Coffs Or Clarence? Want To Help?: Join The Glossy Squad

- a female bird (identifiable by yellow on her head) begging and/or being fed by a male (with plain black/brown head and body and unbarred red tail feathers)

- a lone adult male, or a male with a begging female, flying purposefully after drinking at the end of the day.

Loss Of Antarctic Sea Ice Causes Catastrophic Breeding Failure For Emperor Penguins: 'There Is No Time Left'

$850,000 In Funding Open To Improve Fish Habitat

- removal or modification of barriers to fish passage

- rehabilitation of riparian lands (riverbanks, wetlands, mangrove forests, saltmarsh)

- re-snagging waterways with timber structure

- the removal of exotic vegetation from waterways and replacement with native plants

- bank stabilisation works

- fencing to exclude livestock.

Blue Mountains National Park And Kanangra-Boyd National Park Draft Plan Of Management: Public Consultation

- improving recognition of the parks significant values, including World and National Heritage values, and providing for adaptive management to protect the values

- recognising and supporting the continuation of partnerships with Aboriginal communities

- providing outstanding nature-based experiences for visitors through improvements to visitor facilities - including:

- Opportunities for supported or serviced camping, where tents and services are provided by commercial tour operators, may be offered at some camping areas in the parks

- Jamison Creek, Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Leura Amphitheatre Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Mount Solitary Jamison Valley Walk-in camping Potential new camping

- Maxwell’s HuC Kedumba Valley Cabin/hut Potential new accommodation

- Kedumba Valley Maxwell’s Hut (historic slab hut) - Building restoration in progress; potential new Accommodation for bushwalkers

- Government Town Police station; courthouse - Potential new Visitor accommodation

- write clearly and be specific about the issues that are of concern to you

- note which part or section of the document your comments relate to

- give reasoning in support of your points - this makes it easier for us to consider your ideas and will help avoid misinterpretation

- tell us specifically what you agree/disagree with and why you agree or disagree

- suggest solutions or alternatives to managing the issue if you can.

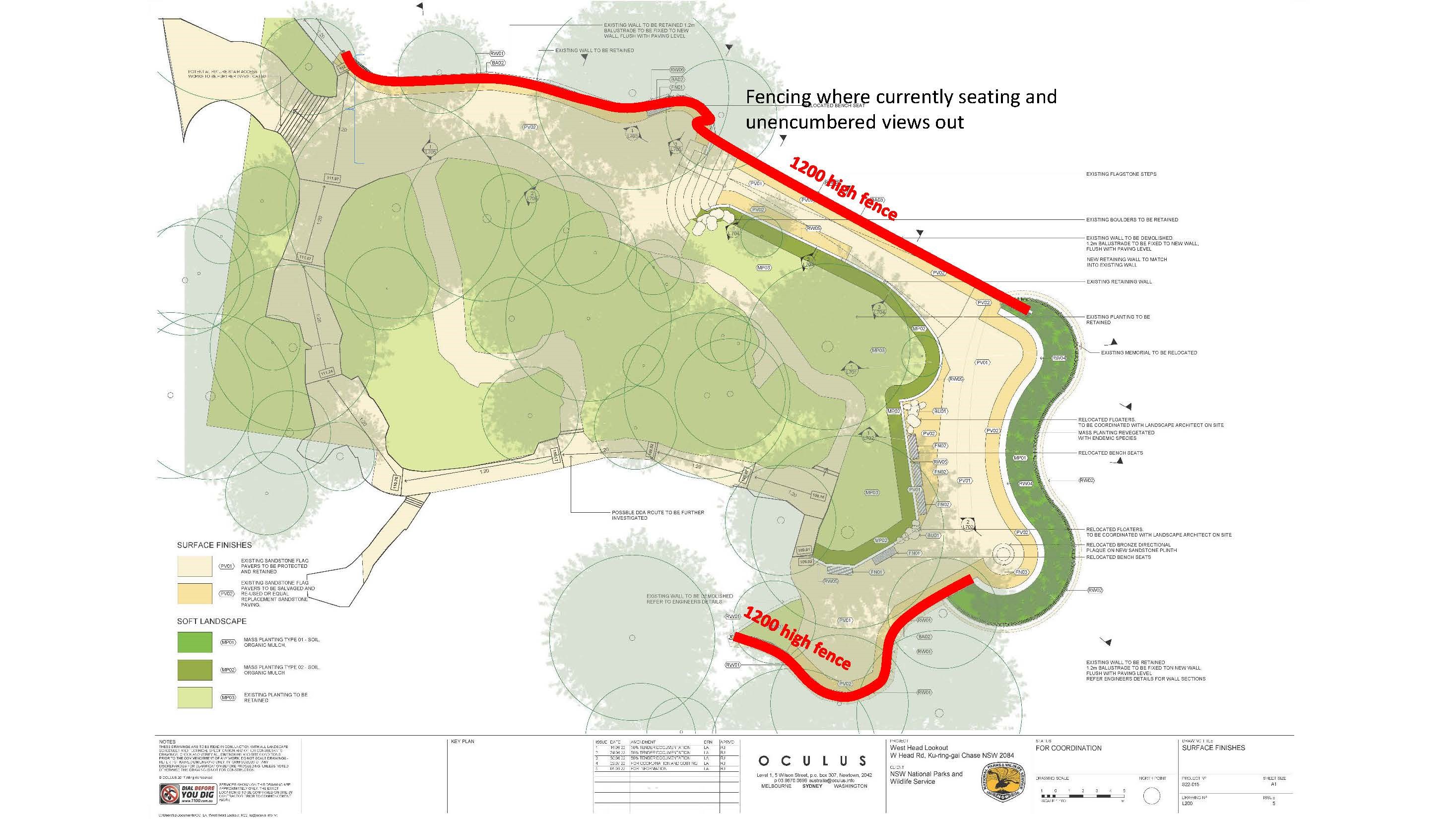

Areas Closed For West Head Lookout Upgrades

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

NPWS advise that the following areas are closed from Monday 22 May to Thursday 30 November 2023 while West Head lookout upgrades are underway:

- West Head lookout

- The loop section of West Head Road

- West Head Army track.

Vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians will have access to the Resolute picnic area and public toilets. Access is restricted past this point.

The following walking tracks remain open:

- Red Hands track

- Aboriginal Heritage track

- Resolute track, including access to Resolute Beach and West Head Beach

- Mackeral Beach track

- Koolewong track.

The West Head lookout cannot be accessed from any of these tracks.

Image: Visualisation of upcoming works, looking east from the ramp towards Barrenjoey Head Credit: DPE

PNHA Guided Nature Walks 2023

Our walks are gentle strolls, enjoying and learning about the bush rather than aiming for destinations. Wear enclosed shoes. We welcome interested children over about 8 years old with carers. All Welcome.

So we know you’re coming please book by emailing: pnhainfo@gmail.com and include your phone number so we can contact you if weather is doubtful.

The whole PNHA 2023 Guided Nature Walks Program is available at: http://pnha.org.au/test-walks-and-talks/

Red-browed finch (Neochmia temporalis). Photo: J J Harrison

Report Fox Sightings

%20(1).jpg?timestamp=1675893929686)

Marine Wildlife Rescue Group On The Central Coast

A new wildlife group was launched on the Central Coast on Saturday, December 10, 2022.

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast (MWRCC) had its official launch at The Entrance Boat Shed at 10am.

The group comprises current and former members of ASTR, ORRCA, Sea Shepherd, Greenpeace, WIRES and Wildlife ARC, as well as vets, academics, and people from all walks of life.

Well known marine wildlife advocate and activist Cathy Gilmore is spearheading the organisation.

“We believe that it is time the Central Coast looked after its own marine wildlife, and not be under the control or directed by groups that aren’t based locally,” Gilmore said.

“We have the local knowledge and are set up to respond and help injured animals more quickly.

“This also means that donations and money fundraised will go directly into helping our local marine creatures, and not get tied up elsewhere in the state.”

The organisation plans to have rehabilitation facilities and rescue kits placed in strategic locations around the region.

MWRCC will also be in touch with Indigenous groups to learn the traditional importance of the local marine environment and its inhabitants.

“We want to work with these groups and share knowledge between us,” Gilmore said.

“This is an opportunity to help save and protect our local marine wildlife, so if you have passion and commitment, then you are more than welcome to join us.”

Marine Wildlife Rescue Central Coast has a Facebook page where you may contact members. Visit: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100076317431064

- Ph: 0478 439 965

- Email: marinewildlifecc@gmail.com

- Instagram: marinewildliferescuecc

Watch Out - Shorebirds About

.JPG.opt1460x973o0,0s1460x973.jpg?timestamp=1663629195339)

Possums In Your Roof?: Do The Right Thing

Aviaries + Possum Release Sites Needed

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment Activities

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

We studied more than 1,500 coastal ecosystems - they will drown if we let the world warm above 2℃

Much of the world’s natural coastline is protected by living habitats, most notably mangroves in warmer waters and tidal marshes closer to the poles. These ecosystems support fisheries and wildlife, absorb the impact of crashing waves and clean up pollutants. But these vital services are threatened by global warming and rising sea levels.

Recent research has shown wetlands can respond to sea level rise by building up their root systems, pulling carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in the process. Growing recognition of the potential for this “blue” carbon sequestration is driving mangrove and tidal marsh restoration projects.

While the resilience of these ecosystems is impressive, it is not without limits. Defining the upper limits to mangrove and marsh resilience under accelerating sea level rise is a topic of great interest and considerable debate.

Our new research, published today in the journal Nature, analyses the vulnerability and exposure of mangroves, marshes and coral islands to sea level rise. The results underscore the critical importance of keeping global warming within 2 degrees of the pre-industrial baseline.

What We Did

We pulled together all the available evidence on how mangroves, tidal marshes and coral islands respond to sea level rise. That included:

delving into the geological record to study how coastal systems responded to past sea level rise, following the last Ice Age

tapping into a global network of survey benchmarks in mangroves and tidal marshes

analysing satellite imagery for changes in the extent of wetlands and coral islands at varying rates of sea level rise.

Altogether, our international team assessed 190 mangroves, 477 tidal marshes and 872 coral reef islands around the world.

We then used computer modelling to work out how much these coastal ecosystems would be exposed to rapid sea level rise under projected warming scenarios.

What We Found

Mangroves, tidal marshes and coral islands can cope with low rates of sea-level rise. They remain stable and healthy.

We found most tidal marshes and mangroves are keeping pace with current rates of sea level rise, around 2–4mm per year. Coral islands also appear stable under these conditions.

In some locations, land is sinking, so the relative rate of sea level rise is greater. It may be double this 2–4mm figure or more, comparable to rates expected under future climate change. In these situations, we found marshes failing to keep up with sea level rise. They are slowly drowning and in some cases, breaking up. What’s more, these are the same rates of sea level rise under which marshes and mangrove drown in the geological record.

These cases give us a glimpse of the future in a warming world.

So if the rate of sea level rise doubles to 7 or 8 millimetres a year, it becomes “very likely” (90% probability) mangroves and tidal marshes will no longer keep pace, and “likely” (about 67% probability) coral islands will undergo rapid changes. These rates will be reached when the 2.0℃ warming threshold is exceeded.

Even at the lower rates of sea level rise we would have between 1.5℃ and 2.0℃ of warming (4 or 5mm a year), extensive loss of mangrove and tidal marsh is likely.

Tidal marshes are less exposed to these rates of sea level rise than mangroves because they occur in regions where the land is rising, reducing the relative rate of sea level rise.

Let’s Give Coastal Ecosystems A Fighting Chance

We know mangroves and tidal marshes have survived rapid sea level rise before, at rates even higher than those projected under extreme climate change.

They won’t have long enough to build up root systems or trap sediment in order to stay in place, so they will seek higher ground by shifting landward into newly flooded coastal lowlands.

But this time, they will be competing with other land uses and increasingly trapped behind coastal levees and hard barriers such as roads and buildings.

If the global temperature rise is limited to 2℃, coastal ecosystems have a fighting chance. But if this threshold is exceeded, they will need more help.

Intervention is needed to enable the retreat of mangroves and tidal marshes across our coastal landscapes. There is a role for governments in designating retreat pathways, controlling coastal development, and expanding coastal nature reserves into higher ground.

The future of the world’s living coastlines is in our hands. If we work to restore mangroves and tidal marshes to their former extent, they can help us tackle climate change. ![]()

Neil Saintilan, Professor, School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

They sense electric fields, tolerate snow and have ‘mating trains’: 4 reasons echidnas really are remarkable

Many of us love seeing an echidna. Their shuffling walk, inquisitive gaze and protective spines are unmistakable, coupled with the coarse hair and stubby beak.

They look like a quirky blend of hedgehog and anteater. But they’re not related to these creatures at all. They’re even more mysterious and unusual than commonly assumed.

Australia has just one species, the short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus), which roams virtually the entire continent. But it has five subspecies, which are often markedly different. Tasmanian echidnas are much hairier and Kangaroo Island echidnas join long mating trains.

Here are four things that make echidnas remarkable.

1: They’re Ancient Egg-Laying Mammals

Short-beaked echidnas are one of just five species of monotreme surviving in the world, alongside the platypus and three worm-eating long-beaked echidna species found on the island of New Guinea.

Our familiar short-beaked echidnas can weigh up to six kilograms – but the Western long-beaked echidna can get much larger at up to 16kg.

These ancient mammals lay eggs through their cloacas (monotreme means one opening) and incubate them in a pouch-like skin fold, nurturing their tiny, jellybean-sized young after hatching.

Scientists believe echidnas began as platypuses who left the water and evolved spines. That’s because platypus fossils go back about 60 million years and echidnas only a quarter of that.

Remarkably, the echidna still has rudimentary electroreception. It makes sense the platypus relies on its ability to sense electric fields when it’s hunting at the bottom of dark rivers, given electric fields spread more easily through water. But on land? It’s likely echidnas use this ability to sense ants and termites moving through moist soil.

It probably got its English name in homage to the Greek mythological figure Echidna, who was half-woman, half-snake, and the mother of Cerberus and Sphinx. This was to denote the animal’s mix of half-reptilian, half-mammal traits. First Nations groups knew the echidna by many other names, such as bigibila (Gamilaraay) and yinarlingi (Warlpiri).

2: From Deserts To Snow, Echidnas Are Remarkably Adaptable

There are few other creatures able to tolerate climate ranges as broad. You can find echidnas on northern tropical savannah amid intense humidity, on coastal heaths and forests, in arid deserts and even on snowy mountains.

The five subspecies of short-beaked echidna have distinct geographic regions. The one most of us will be familiar with is Tachyglossus aculeatus aculeatus, widespread across Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria. You can think of this as “echidna classic”.

Then there’s Kangaroo Island’s T. aculeatus multiaculeatus, Tasmania’s T. aculeatus setosus, the Northern Territory and Western Australia’s T. aculeatus acanthion and the tropical subspecies T. aculeatus lawesii found in Northern Queensland and Papua New Guinea.

You might think subspecies wouldn’t be too different – otherwise they’d be different species, right? In fact, subspecies can be markedly different, with variations to hairiness and the length and width of spines.

Kangaroo Island echidnas have longer, thinner, and paler spines – and more of them, compared to the mainland species. Tasmanian echidnas are well adapted to the cold, boasting a lushness of extra hair. Sometimes you can’t even see their spines amidst their hair.

3: Mating Trains And Hibernation Games

Remarkably, the subspecies have very different approaches to mating. You might have seen videos of Kangaroo Island mating trains, a spectacle where up to 11 males fervently pursue a single female during the breeding season. Other subspecies do this, but it’s most common on Kangaroo Island. Scientists believe this is due to population density.

Pregnancy usually lasts about three weeks after mating for Kangaroo Island echidnas, followed by a long lactation period of 30 weeks for the baby puggle.

But Tasmanian echidnas behave very differently. During the winter mating season, males seek out hibernating females and wake them up to mate. Intriguingly, females can put their pregnancy on hold and go back into hibernation. They also have a shorter lactation period, of only 21 weeks.

What about the echidna subspecies we’re most familiar with? T. aculeatus aculeatus has a similarly short lactation period (23 weeks), but rarely engages in mating train situations. After watching the pregnancies of 20 of these echidnas, my colleagues and I discovered this subspecies takes just 16–17 days to go from mating to egg laying.

4: What Do Marsupials And Monotremes Have In Common?

Marsupials bear live young when they’re very small and let them complete their development in a pouch. Despite this key difference with monotremes, there’s a fascinating similarity between Australia’s two most famous mammal families.

At 17 days after conception, the embryo of the tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii) hits almost exactly the same developmental milestone as echidna embryos. Both are in the somite stage, where paired blocks of tissue form along the notochord, the temporary precursor to the spinal cord, and each have around 20 somites.

What’s remarkable about this? Monotremes branched off from other mammals early on, between 160 and 217 million years ago. Marsupials branched off later, at around 143–178 million years ago.

Yet despite millions of years of evolutionary pressure and change, these very different animals still hit a key embryo milestone at the same time. This striking parallel suggests the intricate process has been conserved for over 184 million years.

In echidnas, this milestone is tied to egg-laying – the embryo is packaged up in a leathery egg the size of a grape and laid into the mother’s pouch. The baby puggle hatches 10–11 days later. In tammar wallabies, the embryo continues to develop in-utero for another 9–10 days before being born.

So the next time you spot the humble echidna, take a moment to appreciate what a remarkable creature it is. ![]()

Kate Dutton-Regester, Lecturer, Veterinary Science, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

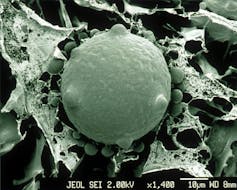

How a lethal fungus is shrinking living space for our frogs

Geoffrey Heard, The University of Queensland; Benjamin Scheele, Australian National University; Conrad Hoskin, James Cook University; Jarrod Sopniewski, The University of Western Australia, and Jodi Rowley, UNSW SydneyIn 1993, frogs were found dying en masse in Far North Queensland. When scientists analysed their bodies, they found something weird. Their small bodies were covered in spores.

It was an epidemic. An aquatic fungus had eaten the keratin in their skin, compromising its function and leading to cardiac arrest. And worse, the amphibian chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) had been quietly spreading around the world, from South America to Europe, killing frogs wherever it went.

Likely native to the Korean Peninsula, it was first detected in Australia in the late 1970s. As it spread, it caused the extinction of at least four Australian frog species and probably three others.

This lethal pathogen is a selective killer. As our new research shows, it effectively makes some areas a no-go zone for susceptible frog species. The fungus doesn’t like hot conditions. But in cooler environments – such as in southern Australia and higher up in mountain ranges – it flourishes. Mortality rates in these environments can approach 100% for some frog species.

Pushed From The Highlands

Australia is rich in frogs, with 247 surviving species at last count. Most are endemic to the continent – and many are spectacularly beautiful or, like the turtle frog, bizarre.

The gorgeous Australian lace-lid treefrog was once widespread across the rainforests of Queensland’s Wet Tropics, which run from Townsville to Cooktown, stretching from sea level up to Queensland’s highest mountain, the 1,622 metre Mt Bartle Frere.

Lace-lid treefrogs once lived throughout these forests, whether on mountains or down near sea level. But they have been driven from rainforests above 400 metres. Down lower, the heat makes it harder for chytrid to kill, and the frog’s higher breeding rate can outpace deaths from the disease.

No-Go Zones

Australians know full well about the damage introduced species can do. Cane toads kill native predators like quolls who aren’t used to their toxin. Cats and foxes have driven many small mammals to extinction.

But even when a species survives contact with an introduced species, it can be forever changed.

That’s because of less visible effects introduced species like chytrid fungus can have, such as shrinking the areas where native species can survive. When this happens, our species can be pushed into smaller parts of their original range, known as environmental refuges.

As our research shows, it’s not just geographic range that changes. It also changes their niche – the set of environmental conditions where species can survive. Introduced species can actually force much larger contractions to a native species’ niche than to its geographic range.

You might wonder how that can be. It’s because the damage done by introduced species can vary a lot depending on the environment. Introduced species have their own niche – climates and environments where they thrive, and areas where they don’t.

Frog species that survived the initial epidemics don’t just persist in random parts of their old range. Hotter, wetter areas or those with less temperature variability become refuges. Chytrid is still widespread here, but it’s less lethal.

Part of the puzzle is also the fact these refuge areas are naturally easier places for frogs to survive and reproduce. Where populations thrive, they have greater resilience and stand a better chance of surviving the fungus.

Pushed Into Refuges

The pattern we document isn’t just seen in frogs. Researchers suspect similar changes have been forced on many native species impacted by introduced species.

Consider the bush-stone curlew – a long-legged, endearing bird with eerie night cries. Many of us will have seen them haunting parks and beer gardens across northern Australia. But the same bird is now extinct or critically endangered in southern Australia, where it used to roam. Why?

Habitat loss has played a role, but this species is highly susceptible to foxes. Foxes don’t much like the humidity of tropical and subtropical Australia. As a result, the curlew has been pushed out of the drier parts of its niche.

Niche contractions due to introduced species are likely to be widespread but little-studied.

If a species has a shrinking niche, it may change where conservationists direct their efforts. To give threatened species the best chance of survival, we might have to direct our energies to safeguarding them in their environmental refuges, safe from introduced predators or diseases.

When scientists assess how a species is going, we often look at changes in geographic range to gauge the level of risk to the species, from vulnerable through to extinct in the wild.

But this can have limitations. What our work has shown is that the survivable niche for species can shrink much more than its geographic range, reducing resilience to new environmental challenges. If frog species are forced out of upland areas, they may be at more risk from climate change, given higher elevations are likely to be most resilient to climate change.

There’s a silver lining here, though. Species can be more resilient than we assume in the face of new threats. Some populations may be hard hit, while others escape. Understanding why that is will be key to give our native species the best chance of surviving an uncertain future. ![]()

Geoffrey Heard, Research fellow, Australian National University and, The University of Queensland; Benjamin Scheele, Research Fellow in Ecology, Australian National University; Conrad Hoskin, Senior Lecturer, College of Science & Engineering, James Cook University; Jarrod Sopniewski, PhD student, The University of Western Australia, and Jodi Rowley, Curator, Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Biology, Australian Museum, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The humble spotted gum is a world class urban tree. Here’s why

Most of us find it very difficult to identify different species of eucalypt. You often hear people say they all look the same.

Of course, they don’t. There are over 700 species of the iconic tree genus, and they can be very different in form, height, flowers and colours.

With all this variety, it’s nice to have a few species we can identify from metres away, just from looking at the colours and patterns of the bark on the trunk. The spotted gum is one of these instantly recognisable eucalypts.

You may well have seen a spotted gum growing happily on an urban street. These smooth-barked eucalypts have been planted up and down many suburban streets.

In fact, if the spotted gum has a secret superpower, it would be the ability to fit into our cities with a minimum of fuss. They’re big trees, and produce vast quantities of blossoms, attracting nectar-eaters like rainbow lorikeets in droves. They grow easily, grow straight and grow tall.

Why Are Spotted Gums Special?

Spotted gum used to be called Eucalyptus maculata. Now it’s officially Corymbia maculata after a name change about 25 years ago. Some people still debate this.

It was probably the trunk and bark of these trees which first caught your eye. These trees replace their bark seasonally, but not all at once. Instead, bits of the bark are shed and new bark grows at different rates. That leaves the famous spots on their trunks (maculatus is Latin for spotted).

Early in the growing season some of these spots can be a bright green before fading to tans and greys over the coming months. Many patterns can be stunningly beautiful.

These trees are loved by many. But there are sceptics. Some feel the trees can be a nuisance, and even dangerous because of the bark and branches they shed. There is some truth to it, as they can drop branches during droughts. Interestingly, these hardwood trees are actually considered fire resistant.

But there are very good reasons our city planners and councils turn to the spotted gum. Their wonderfully straight, light coloured and spotted trunks are impressive whether trees are planted singly, in avenues (meaning two rows of trees) or in boulevards (four rows of trees).

They often get to an impressive 30–45 metres in height. Old trees can get over 60m.

During profuse flowering, anthers (the pollen-bearing part of the stamen) shed from a single tree can cover the ground, paths, homes, roads and vehicles in a white snow-like frosting.

In nature, the spotted gum and close relatives, the lemon scented gum (C. citriodora) and large leafed spotted gum (C. henryii) grow along the east coast of Australia, from far eastern Victoria to southern Queensland. In New South Wales forests, you might be lucky enough to spot the pairing of spotted gums and native cycads (Macrozamia), ancient plants resembling palms.

Spotted gums are quick growing and hardy, if a little frost-sensitive when young. They can tolerate periods of waterlogged soil. These traits make the species well suited to urban use, where disturbed and low-oxygen soils are common due to paving, compaction and waterlogging.

Urban trees have to be able to establish quickly and with relatively little care. They need to cope with environmental stresses and very poor quality urban soils. They need tall straight trunks so people and vehicles can pass under them, and so our cities keep their clear sight lines.

But we also want street trees to have broad, spreading canopies with a dense green foliage, to give shade, privacy and beauty.

As you can see, it’s a tough set of requirements. The spotted gum meets all of these. In fact, it has the potential to be one of the great urban tree species, not just in Australia but internationally.

Resilient Trees For The Future Climate

Spotted gums are tough. On urban streets in many parts of Australia, they will endure as the climate changes – possibly for decades or even centuries. They possess both lignotubers, the protective swelling at the base of the trunk, and epicormic buds, which lie dormant under the bark in readiness for fire and other stresses. These let the trees cope well with the abuses urban life can throw at them.

Horticulturalists have been working to make the tree even better suited to urban use. Careful selection has created spotted gum varieties geared towards dense, spreading canopies and with reduced risk of dropping branches.

But not all spotted gums you see are like this. These varieties were uncommon or didn’t exist 50 years ago, which means old urban trees might be more likely to shed limbs or have less attractive forms.

These trees are survivors. Near Batemans Bay in New South Wales lives Old Blotchy, the oldest known spotted gum. It’s estimated to be 500 years old.

Some urban trees are already 150 years old and in fine condition. Planting good quality spotted gums in a good position is a way to leave a lasting legacy.

As climate change intensifies, city planners are looking for resilient street trees able to provide cooling shade in a hotter climate. They could do a lot worse than choosing C. maculata.![]()

Gregory Moore, Senior Research Associate, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

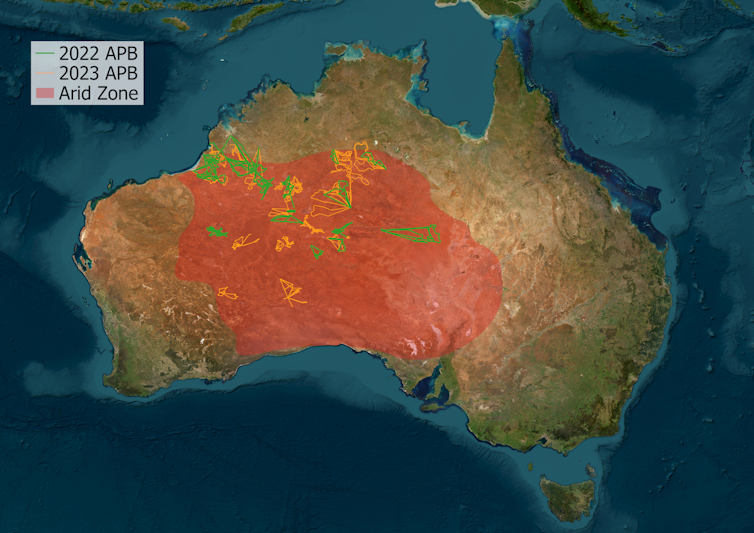

Indigenous rangers are burning the desert the right way – to stop the wrong kind of intense fires from raging

Even though it’s still winter, the fire season has already started in Australia’s arid centre. About half of the Tjoritja West MacDonnell National Park west of Alice Springs has burnt this year.

The spread of buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) has been seen as a key factor. This invasive grass has been ranked the highest environmental threat to Indigenous cultures and communities because of the damage it can do to desert Country.

Widespread rains associated with the La Niña climate cycle trigger a boom in plant growth. When the dry times come again, plants and grasses dry out and become potential fuel for massive desert fires.

These fires often don’t get much notice because nearly all Australians live near the coast. But they can be huge. In 2011, over 400,000 square kilometres burnt – about half the size of New South Wales.

After three years of La Niña rains, we’re in a similar situation – or potentially worse. Fire authorities are warning up to 80% of the Northern Territory could burn this fire season.

That’s why dozens of Indigenous ranger groups across 12 Indigenous Protected Areas have been hard at work in an unprecedented collaboration, burning to reduce the fuel load before the summer’s heat. So far, they’ve burned 23,000 square kilometres across the Great Sandy, Tanami, Gibson and Great Victoria Deserts.

Burning The Arid Lands

Australia now has 82 Indigenous Protected Areas, covering over 87 million hectares of land. That’s half of the entire reserve of protected lands, and they’re growing fast as part of efforts to protect 30% of Australia’s lands and waters by 2030. These areas are managed by Indigenous groups – and fire is a vital part of management.

The goal is to protect against devastating summer bushfires, which are more destructive. Without Indigenous rangers expertly managing the deserts through landscape-scale fire management, these protected lands would be at risk of decline.

As Braeden Taylor, Karajarri Ranger Coordinator, says:

A big wildfire just destroys everything, it destroys Country. The first aim is to do a bit of ground burning and then aerial burning, that way we know everything is protected. Using the helicopter and plane, we can access Country that’s hard to get to in a vehicle. It might not have been burnt in a long time and we can break it up

It’s good working with other groups. Fires that start on their side might come over to us and fires on ours might go to them. Working together we protect each other, looking after neighbours.

So how do the rangers cover such distances? These protected areas are extremely remote. There is often no or very limited road access. So rangers work from the sky – and, where possible, the ground. The ranger fire program relies on helicopters and incendiaries [fire starting devices]. This year, rangers have spent 448 hours in the air, covering 58,457 kilometres and dropping 299,059 incendiaries.

When the incendiaries hit the ground, they begin burning. Not every incendiary hits the right spot, so it takes time to guarantee a good burn is under way. These arid lands tend to have more grass than trees, so the fires move along the ground and don’t get too intense.

Rangers couple aerial burning with fine-scale ground burning using drip torches around sensitive areas. That’s to ensure protection of cultural sites and threatened species like the bilby, night parrot and great desert skink.

This is vitally important, given about 60% of desert mammal species have already gone extinct over the last 250 years, while many others have seen their range reduce. Changes to fire regimes are a major factor in these declines.

Fire Can Forge Community

These desert-spanning fire projects give Traditional Owners the ability to see remote Country, practice culture and transfer knowledge down the generations.

As Ronald Hunt, Ngaanyatjarra Ranger, says:

When we burn it cleans up all the spinifex grass and when the rain comes it all grows up fresh. It’s good for the animals, the bushfood and all. Its good using the helicopter, going places that it’s hard to get to. It’s good to work together with other groups, sharing stories and looking after the Country. They have their stories, and we have ours, and then we come together to work.

In recent years, there has been a surge of interest in Indigenous fire management – especially after the devastation of the Black Summer fires of 2019–2020.

The goal is to shift from wrong-way fire – where fuel builds up until large, damaging bushfires ignite – to right-way fire, culturally informed fire regimes led by Traditional Owners.

These fires are done regularly, with small fires of varying intensity producing a fine-scale mosaic of vegetation at different stages of recovery and maintaining long-unburned vegetation as safe harbours for wildlife and plants.

Recent research shows the return to these right-way fire regimes at a landscape scale is having a real effect. In areas where this is done, the desert landscape is returning to a complex, pre-colonisation pattern of mosaic burns.

These large-scale efforts should make Country healthier and bring reprieve from dangerous fire. ![]()

Rohan Fisher, Information Technology for Development Researcher, Charles Darwin University and Boyd Elston, Co-Chairperson of the Indigenous Desert Alliance and a Regional Land Management Coordinator at the Central Land Council, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Labor’s new Murray-Darling Basin Plan deal entrenches water injustice for First Nations

The federal government has struck a new deal with most of the states in the nation’s largest river system. The agreement, announced last week, extends the $13 billion 2012 Murray-Darling Basin Plan to rebalance water allocated to the environment, irrigators and other uses.

Environment and Water Minister Tanya Plibersek said the government has:

negotiated a way to ensure there is secure and reliable water for communities, agriculture, industry, First Nations and the environment.

But there is no mention of water for First Nations in the agreement. This follows a history of Indigenous peoples being shortchanged by Murray-Darling Basin planning. Yet again, this latest deal ignores First Nations’ interests, despite millennia of custodianship.

Shortchanged In Reforms