Inbox and Environment News: Issue 430

November 24 - 30, 2019: Issue 430

Spring Becomes Summer In Pittwater

Save Grevillea Caleyi With PNHA's Baha'i Bushcare This Monday: November 25th

First Christmas Beetle Spotted At Elanora Heights/ Ingleside

On Hot Days Please Keep Your Bird Baths Topped Up Or Put Out Dishes Of Water For Local Fauna

PNHA Christmas Cards Of Local Beauties

PNHA Christmas Cards with local trees, flowers, insects, birds, scenery are now ready - write your own message. $2.00 each. Contact us on pnhainfo@gmail.com to select from our big range. A few of the images available on their covers sampled here:

NSW Christmas Bush

Sleepy Eastern Pygmy Possum

Christmas Bells

Native Fuchsia

Male Variegated Wren, one of Pittwater's two Fairy Wrens. Image: Neil Fifer

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

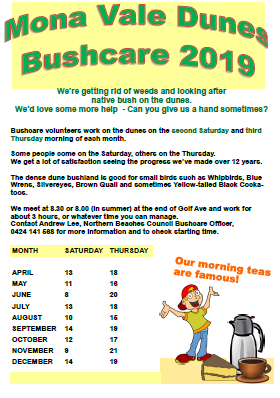

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday+3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Affordable Reliable Power For NSW

Our land is burning, and western science does not have all the answers

Last week’s catastrophic fires on Australia’s east coast – and warnings of more soon to come – will become all too common as climate change gathers pace. And as the challenges of modern hazard reduction become clear, there is much to learn from the ancient Aboriginal practice of burning country.

Indigenous people learnt to use fire skillfully and to their advantage, including to moderate bushfires. Most of the fires were small and set at dry times of the year, resulting in a fine-scale mosaic of different vegetation types and fuel ages. This made intense bushfires uncommon and made plant and animal foods more abundant.

Read more: A surprising answer to a hot question: controlled burns often fail to slow a bushfire

Contemporary fire managers also attempt to lower bushfire risk by reducing fuel loads through hazard reduction burning. To minimise costs, this is often achieved by dropping incendiaries from aircraft.

Concern is growing that such methods exacerbate biodiversity declines and often do not prevent a subsequent bushfire. As climate change makes bushfires more ferocious and extreme, now is the time to better understand how our First Peoples used fire.

A Slow, Ancient Craft

Traditional Aboriginal fire practices are based on local knowledge and spiritual connection to country.

Before white settlement, Aboriginal people were a constant presence in the landscape, and traditionally burnt country by walking the land. This meant they could control the timing and spread of fire, as well as its ecological effects.

By contrast, most modern fire programs are far less flexible and responsive. They usually take place on weekdays in specific seasons and weather conditions. Many fires are ignited from the air – especially those in remote areas where vast areas of burning is desired. This technique results in bigger, more intense fires than those conducted by Aboriginal people.

Read more: Grattan on Friday: When the firies call him out on climate change, Scott Morrison should listen

Contemporary fire managers do reduce fuel in small areas, through ground crews working on foot. These crews often work in specific weather windows such as fog, and at cooler times of day such as the evening, to keep fires controlled and protect sensitive areas.

This method is reminiscent of Aboriginal fire practice and leads to smaller, less intense fires than aerial ignition. But it also differs from traditional techniques. Modern ground crews use “drip torches” – hand-held devices filled with fuel – and burn in a box pattern. By contrast, Indigenous people use a slower technique such as dragging a smouldering stick through the bush, and burn in spiral or strip patterns to achieve a mosaic effect.

Taking Lessons From The Past

Aboriginal fire practice across Australia was severely disrupted by European invasion. The practice is being reinvigorated through initiatives such as the Firesticks Alliance, an Indigenous-led network involving training, on-ground works and scientific monitoring to better understand the ecological effects of cultural burning.

But there is a huge opportunity to further develop traditional fire management alongside western science. Our project on a farm in Tasmania offers a good example. Since 2017, University of Tasmania scientists have worked with a farmer and the Aboriginal community to reintroduce Indigenous burning to native grasslands (see video below).

This project began as straightforward research into fire management in an endangered eucalypt woodland community. It took a novel turn when the landowner asked that the Tasmanian Aboriginal community be involved. We then employed Aboriginal rangers to burn experimental plots.

Importantly, this research does not take the old-school anthropological approach of solely studying Aboriginal burning practices. Instead, it is a true collaboration where all parties learn from each other.

As a consequence, the project design changed in the course of the experiment. For example its original “efficient” approach involved burning predetermined units of a set size. But in the second year, Aboriginal rangers selected the areas burnt, resulting in a patchy and varied burning pattern.

Read more: Bushfires can make kids scared and anxious: here are 5 steps to help them cope

The project is still being monitored and results are not finalised. However it has already achieved an important goal: stronger cross-cultural partnerships.

Such initiatives should not be rushed. Genuine engagement of the Aboriginal community requires time, allowing trust to build between groups that don’t have a long history of working together.

The project took place on private property, at the request of a landowner who took responsibility for approvals and compliance. Such small-scale projects are excellent for building skills and allowing Aboriginal people to reconnect with country. Upscaling such projects to public lands such as national parks requires more complex negotiation and agreement, but this will be easier if a record of successful smaller programs exists.

Looking To The Future

There are profound cultural differences between traditional and modern fire management, stemming from different understanding of belonging, place, history, values and metaphysics.

The growing fire crisis means it’s vital western science and Aboriginal knowledge are brought together to make communities as fire-safe as possible.

This includes a sustainable funding model for Indigenous-led fire management programs, as well as cross-cultural training for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous fire managers to better work together.![]()

David Bowman, Professor of Pyrogeography and Fire Science, University of Tasmania and Ben J. French, PhD student in Environmental Change Biology, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Grants Available To Reduce Climate Change Impacts

New report shows the world is awash with fossil fuels. It's time to cut off supply

A new United Nations report shows the world’s major fossil fuel producing countries, including Australia, plan to dig up far more coal, oil and gas than can be burned if the world is to prevent serious harm from climate change.

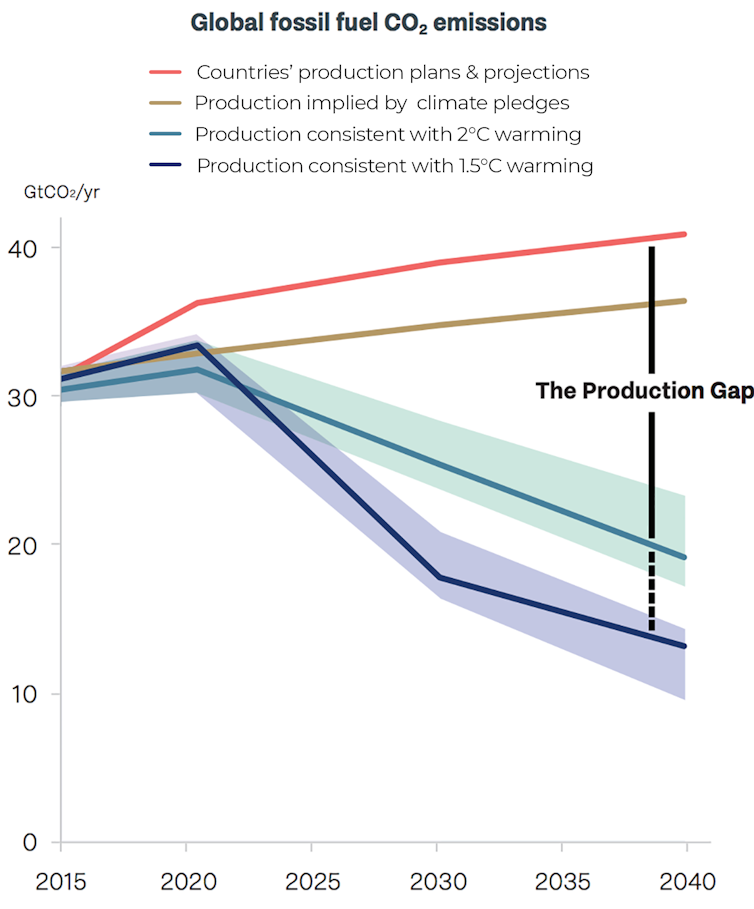

The report found fossil fuel production in 2030 is on track to be 50% more than is consistent with the 2℃ warming limit agreed under the Paris climate agreement. Production is set to be 120% more than is consistent with holding warming to 1.5℃ – the ambitious end of the Paris goals.

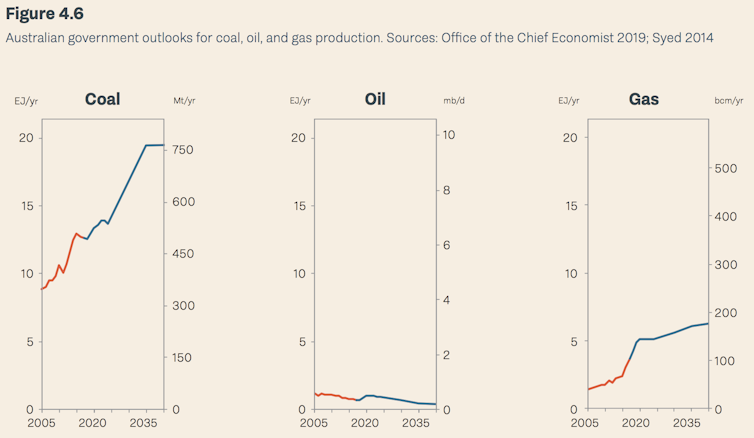

Australia is strongly implicated in these findings. In the same decade we are supposed to be cutting emissions under the Paris goals, our coal production is set to increase by 34%. This trend is undercutting our success in renewables deployment and mitigation elsewhere.

Mind The Production Gap

The United Nations Environment Program’s Production Gap report, to which I contributed, is the first to assess whether current and projected fossil fuel extraction is consistent with meeting the Paris goals.

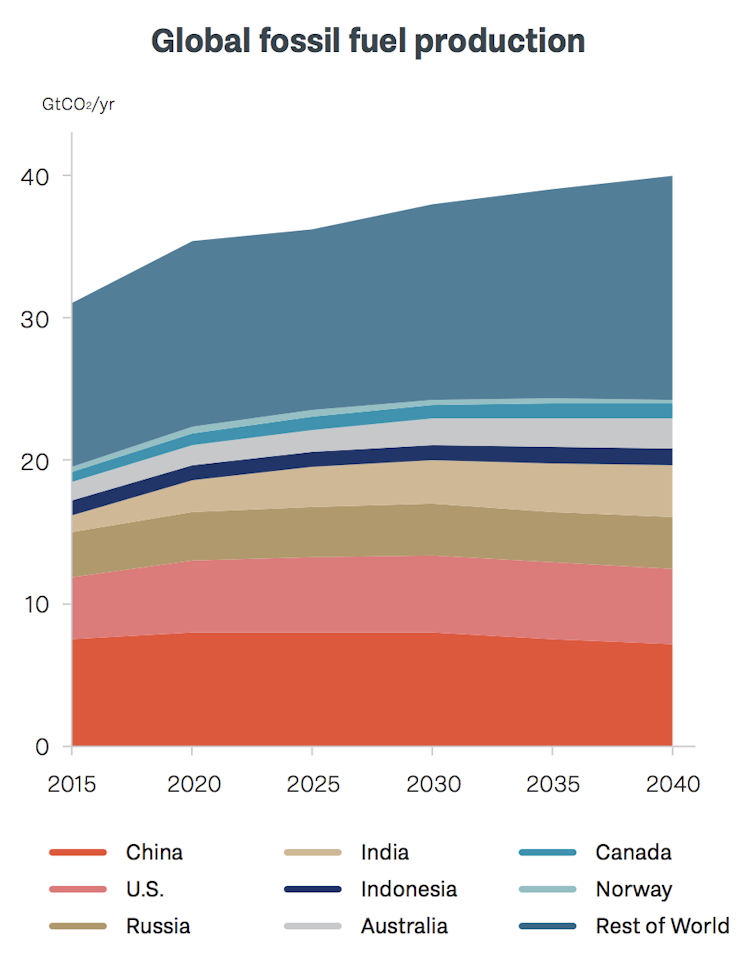

It reviewed seven top fossil fuel producers (China, the United States, Russia, India, Australia, Indonesia, and Canada) and three significant producers with strong climate ambitions (Germany, Norway, and the UK).

Read more: Drought and climate change were the kindling, and now the east coast is ablaze

The production gap is largest for coal, of which Australia is the world’s biggest exporter. By 2030, countries plan to produce 150% more coal than is consistent with a 2℃ pathway, and 280% more than is consistent with a 1.5℃ pathway.

The gap is also substantial for oil and gas. Countries are projected to produce 43% more oil and 47% more gas by 2040 than is consistent with a 2℃ pathway.

Keeping Bad Company

Nine countries, including Australia, are responsible for more than two-thirds of fossil fuel carbon emissions – a calculation based on how much fuel nations extract, regardless of where it is burned.

China is the world’s largest coal producer, accounting for nearly half of global production in 2017. The US produces more oil and gas than any other country and is the second-largest producer of coal.

Australia is the sixth-largest extractor of fossil fuels , the world’s leading exporter of coal, and the second-largest exporter of liquefied natural gas.

Read more: The good, the bad and the ugly: the nations leading and failing on climate action

Prospects for improvement are poor. As countries continue to invest in fossil fuel infrastructure, this “locks in” future coal, oil and gas use.

US oil and gas production are each projected to increase by 30% to 2030, as is Canada’s oil production.

Australia’s coal production is projected to jump by 34%, the report says. Proposed large coal mines and ports, if completed, would represent one of the world’s largest fossil fuel expansions - around 300 megatonnes of extra coal capacity each year.

The expansion is underpinned by a combination of ambitious national plans, government subsidies to producers and other public finance.

In Australia, tax-based fossil fuel subsidies total more than A$12 billion each year. Governments also encourage coal production by fast-tracking approvals, constructing roads and reducing royalty requirements, such as for Adani’s recently approved Carmichael coal mine in the Galilee Basin.

Ongoing global production loads the energy market with cheap fossil fuels – often artificially cheapened by government subsidies. This greatly slows the transition to renewables by distorting markets, locking in investment and deepening community dependency on related employment.

In Australia, this policy failure is driven by deliberate political avoidance of our national responsibilities for the harm caused by our exports. There are good grounds for arguing this breaches our moral and legal obligations under the United Nations climate treaty.

Cutting Off Supply

So what to do about it? As our report states, governments frequently recognise that simultaneously tackling supply and demand for a product is the best way to limit its use.

For decades, efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have focused almost solely on decreasing demand for fossil fuels, and their consumption – through energy efficiency, deployment of renewable technologies and carbon pricing – rather than slowing supply.

While the emphasis on demand is important, policies and actions to reduce fossil fuels use have not been sufficient.

It is now essential we address supply, by introducing measures to avoid carbon lock-in, limit financial risks to lenders and governments, promote policy coherence and end government dependency on fossil fuel-related revenues.

Policy options include ending fossil fuel subsidies and taxing production and export. Government can use regulation to limit extraction and set goals to wind it down, while offering support for workers and communities in the transition.

Read more: Australia could fall apart under climate change. But there's a way to avoid it

Several governments have already restricted fossil fuel production. France, Denmark and New Zealand have partially or totally banned or suspended oil and gas exploration and extraction, and Germany and Spain are phasing out coal mining.

Australia is clearly a major contributor in the world’s fossil fuel supply problem. We must urgently set targets, and take actions, that align our future fossil fuel production with global climate goals.![]()

Peter Christoff, Associate Professor, School of Geography, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Rain Cloak

Transpiration Is How Plants Help Make Rain

Greedy Wild Hamster Stuffs In More Than He Can Chew!

Students Join Lions In Protecting Koalas

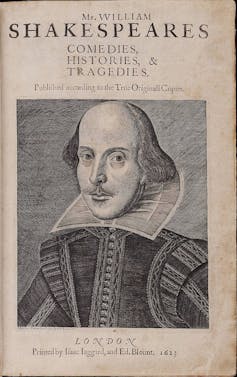

Why do teachers make us read old stories?

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Why do teachers make us read old stories? Nathan, 12, Chicago, Illinois

There are probably as many reasons to read old stories as there are teachers.

Old stories are sometimes strange. They display beliefs, values and ways of life that the reader may not recognize.

As an English professor, I believe that there is value in reading stories from decades or even centuries ago.

Teachers have their students read old stories to connect with the past and to learn about the present. They also have their students read old stories because they build students’ brains, help them develop empathy and are true, strange, delightful or fun.

Connecting With The Past And Present

In Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” for example, teenagers speak a language that’s almost completely unfamiliar to modern readers. They fight duels. They get married. So that might seem to be really different from today.

And yet, Romeo and Juliet fall in love and make their parents mad, very much like many teens today. Ultimately, they commit suicide, something that far too many teens do today. So Shakespeare’s play may be more relevant than it first seems.

Additionally, many modern stories are based on older stories. To name only one, Charlotte Brontë’s “Jane Eyre” has turned up in so many novels since its original publication in 1848 that there are entire articles and book chapters about its influence and importance.

For example, I found references to “Jane Eyre” lurking in “The Princess Diaries,” the “Twilight” series and a variety of other novels. So reading the old story can enrich the experience of the new.

Building Brain And Empathy

Reading specialist Maryanne Wolf writes about the “special vocabulary in books that doesn’t appear in spoken language” in “Proust and the Squid.” This vocabulary – often more complex in older books – is a big part of what helps build brains.

The sentence structure of older books can also make them difficult. Consider the opening of almost any fairy tale: “Once upon a time, in a very far-off country, there lived …”

None of us would actually speak like that, but older stories put the words in a different order, which makes the brain work harder. That kind of exercise builds brain capacity.

Stories also make us feel. Indeed, they teach us empathy. Readers get scared when they realize Harry Potter is in danger, excited when he learns to fly and happy, relieved or delighted when Harry and his friends defeat Voldemort.

Older stories, then, can provide a rich depth of feeling, by exposing readers to a broad range of experiences. Stories featuring characters from a diverse range of backgrounds or set in unfamiliar places can have a similar effect.

Reading Can Be Fun

Old stories are sometimes just so weird that you can’t help but enjoy them. Or I can’t, anyway.

In Charles Dickens’ “Great Expectations,” there’s a character whose last name is “Pumblechook.” Can you say it without smiling?

In Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” a cat disappears bit by bit, eventually leaving only its smile hanging in the air. Again, new stories are also lots of fun, but the fun in the older stories may turn up in those new stories.

For example, that cat returns in many newer tales that aren’t even related to Alice in Wonderland, so knowing the cat’s history can make reading that new story more pleasurable.

I won’t deny that some old stories contain offensive language or reflect attitudes that we may not want to embrace. But even those stories can teach readers to think critically.

Not every old story is good, but when your teacher asks you to read one, consider the possibility that you might build your brain, grow your feelings or have some fun. It’s worth a try, at least.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]![]()

Elisabeth Gruner, Associate Professor of English, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Queen's Album: The NSW State Archives And The State Archives Collection

UNSW Law Student Named As A Finalist For Human Rights Award

Four Ways To Curb Light Pollution And Save Insects

November 18, 2019: Washington University in St. Louis

Artificial light at night negatively impacts thousands of species: beetles, moths, wasps and other insects that have evolved to use light levels as cues for courtship, foraging and navigation.

Writing in the scientific journal Biological Conservation, Brett Seymoure, the Grossman Family Postdoctoral Fellow of the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University in St. Louis, and his collaborators reviewed 229 studies to document the myriad ways that light alters the living environment such that insects are unable to carry out crucial biological functions.

"Artificial light at night is human-caused lighting -- ranging from streetlights to gas flares from oil extraction," Seymoure said. "It can affect insects in pretty much every imaginable part of their lives."

Insects and spiders have experienced global declines in abundance over the past few decades -- and it's only going to get worse. Some researchers have even coined a term for it: the insect apocalypse.

"Most of our crops -- and crops that feed the animals that we eat -- need to be pollinated, and most pollinators are insects," Seymoure said. "So as insects continue to decline, this should be a huge red flag. As a society of over 7 billion people, we are in trouble for our food supply."

Unlike other drivers of insect declines, artificial light at night is relatively straightforward to reverse. To address this problem, here are four things that Seymoure recommends:

1. Turn off lights that aren't needed

The evidence on this one is clear.

"Light pollution is relatively easy to solve, as once you turn off a light, it is gone. You don't have to go and clean up light like you do with most pollutants," Seymoure said.

"Obviously, we aren't going to turn off all lights at night," he said. "However, we can and must have better lighting practices. Right now, our lighting policy is not managed in a way to reduce energy use and have minimal impacts on ecosystem and human health. This is not OK, and there are simple solutions that can remedy the problem."

Four characteristics of electrical light matter the most for insects: intensity (or overall brightness); spectral composition (how colourful and what colour it is); polarisation; and flicker.

"Depending on the insect species, its sex, its behavior and the timing of its activity, all four of these light characteristics can be very important," Seymoure said.

"For example, overall intensity can be harmful for attracting insects to light. Or many insects rely upon polarisation to find water bodies, as water polarises light. So polarised light can indicate water, and many insects will crash into hoods of cars, plastic sheeting, etc., as they believe they are landing on water."

Because it is impossible to narrow down one component that is most harmful, the best solution is often to just shut off lights when they are not needed, he said.

2. Make lights motion-activated

This is related to the first recommendation: If a light is only necessary on occasion, then put it on a sensor instead of always keeping it on.

3. Put fixtures on lights to cover up bulbs and direct light where it is needed

"A big contributor to attraction of light sources for most animals is seeing the actual bulb, as this could be mistaken as the moon or sun," Seymoure said. "We can use full cut-off filters that cover the actual bulb and direct light to where it is needed and nowhere else.

"When you see a lightbulb outside, that is problematic, as that means animals also see that light bulb," he said. "More importantly, that light bulb is illuminating in directions all over the place, including up toward the sky, where the atmosphere will scatter that light up to hundreds of miles away resulting in skyglow. So the easiest solution is to simply put fixtures on light to cover the light bulb and direct the light where it is needed -- such as on the sidewalk and not up toward the sky."

4. Use different colors of lights

"The general rule is that blue and white light are the most attractive to insects," Seymoure said. "However, there are hundreds of species that are attracted to yellows, oranges and reds."

Seymoure has previously studied how different colours of light sources -- including the blue-white colour of LEDs and the amber colour of high pressure sodium lamps -- affect predation rates on moths in an urban setting.

"Right now, I suggest people stick with amber lights near their houses, as we know that blue lights can have greater health consequences for humans and ecosystems," Seymoure said. "We may learn more about the consequences of amber lights. And make sure these lights are properly enclosed in a full cut-off fixture."

Avalon C.S. Owens, Précillia Cochard, Joanna Durrant, Bridgette Farnworth, Elizabeth K. Perkin, Brett Seymoure. Light pollution is a driver of insect declines. Biological Conservation, 2019; 108259 DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108259

Uncovering The Pathway To Wine's Acidity

November 19, 2019: University of Adelaide

University of Adelaide wine researchers say their latest discovery may one day lead to winemakers being able to manipulate the acidity of wines without the costly addition of tartaric acid.

The team of researchers has uncovered a key step in the synthesis of natural tartaric acid in wine grapes -- identifying and determining the structure of an enzyme that helps make tartaric acid in the grapes.

"Tartaric acid is important in all wines -- red, white and sparkling -- providing the finished wine with the vital acid taste to balance the sweetness of alcohol," says project leader Associate Professor Chris Ford, Interim Head of the University of Adelaide's School of Agriculture, Food and Wine.

"For example, in white wines such as a dry Riesling from the Eden Valley, the liveliness of the wine on the palate and the delicate balance of fruit flavours is due to careful management of acid levels in the grapes and during winemaking.

"However, it is often the case that natural levels of acidity in grapes are not enough for winemakers' requirements, requiring the addition of more tartaric acid."

Estimates have suggested that this costs over $10 million to the Australian wine industry each vintage, so understanding what controls the natural levels of acids like tartaric in the grape berry has the potential to save the industry significant sums of money.

"For this to become a reality, we need first to understand the details of the biochemical pathway that produces tartaric acid in the grape," says Associate Professor Ford.

This recent discovery follows an earlier collaboration with University of California Davis, when in 2006 the first enzyme in the six-step pathway that leads from vitamin C (ascorbic acid) to tartaric acid was discovered. Now a second enzyme has been identified and its structure determined and results published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Associate Professor Chris Ford and Dr John Bruning, a protein crystallographer and enzymologist from the School of Biological Sciences and Institute for Photonics and Advanced Sensing, worked with researchers at Flinders University, the James Hutton Institute, Dundee, and postgraduate students Crista Burbidge, Emi Schutz and Yong Jia. They identified the enzyme based on its similarity to a bacterial enzyme with the same properties.

The enzyme was confirmed on the basis of its biochemical activity, and crystals of the enzyme grown so that its structure could be determined to atomic resolution using high-powered X-rays.

"Now that we understanding the 3D structure of this enzyme we can define its function and therefore its chemical mechanism and how it carries out its job in the grape," says Dr Bruning.

"That means we can modify the structure for biotechnological purposes down the line, such as altering the protein to change tartaric acid levels in the plant, instead of directly adding the acid at huge cost to winemakers."

Associate Professor Ford says: "As each piece of this intriguing puzzle falls in to place, our understanding of the metabolism of this critical grape acid increases. We now need to get to grips with the genetic, environmental and viticultural factors we may be able to manipulate to modulate the natural levels of tartaric acid in the grape."

Yong Jia, Crista A. Burbidge, Crystal Sweetman, Emi Schutz, Kathy Soole, Colin Jenkins, Robert D. Hancock, John B. Bruning, Christopher M. Ford. An aldo-keto reductase with 2-keto-l-gulonate reductase activity functions in l-tartaric acid biosynthesis from vitamin C in Vitis vinifera. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2019; 294 (44): 15932 DOI: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010196

Early Season Heatwave Alert

AUSTRAC Applies For Civil Penalty Orders Against Westpac

- appropriately assess and monitor the ongoing money laundering and terrorism financing risks associated with the movement of money into and out of Australia through correspondent banking relationships. Westpac has allowed correspondent banks to access its banking environment and the Australian Payments System without conducting appropriate due diligence on those correspondent banks and without appropriate risk assessments and controls on the products and channels offered as part of that relationship.

- report over 19.5 million International Funds Transfer Instructions (IFTIs) to AUSTRAC over nearly five years for transfers both into and out of Australia. The late incoming IFTIs received from four correspondent banks alone represent over 72% of all incoming IFTIs received by Westpac in the period November 2013 to September 2018 and amounts to over $11 billion dollars. IFTIs are a key source of information from the financial services sector that provides vital information into AUSTRAC’s financial intelligence to protect Australia’s financial system and the community from harm.

- pass on information about the source of funds to other banks in the transfer chain. This conduct deprived the other banks of information they needed to understand the source of funds to manage their own AML/CTF risks.

- keep records relating to the origin of some of these international funds transfers.

- carry out appropriate customer due diligence on transactions to the Philippines and South East Asia that have known financial indicators relating to potential child exploitation risks. Westpac failed to introduce appropriate detection scenarios to detect known child exploitation typologies, consistent with AUSTRAC guidance and their own risk assessments.

Differences In Sensory Brainwaves Of Autistic Teenagers Could Assist In Earlier Diagnosis And Support

Watch Out For 'Feather Duvet Lung' Caution Doctors

November 18, 2019

Watch out for 'feather duvet lung' doctors have warned in the journal BMJ Case Reports after treating a middle aged man with severe lung inflammation that developed soon after he bought feather-filled bedding.

The 43 year old was referred to respiratory specialists after 3 months of malaise, fatigue and increasing breathlessness which affected the simplest of activities, such as going from room to room and walking up the stairs at home.

His symptoms worsened to the point where he could only stand or walk for a few minutes without feeling as if he were about to pass out. He was signed off work and managed to do little more than sleep all day.

He was quizzed about possible triggers for his symptoms: there was a small amount of mould in the bathroom, and he owned a cat and a dog, but no birds, so the doctors concluded that these factors were unlikely to be responsible.

But he had recently swapped a synthetic duvet and pillows for feather filled bedding, he said.

Blood tests revealed antibodies to bird feather dust, and his chest x-ray was consistent with hypersensitivity pneumonitis -- a condition in which the air sacs and airways in the lungs become severely inflamed as a result of the body's exaggerated immune response to a particular trigger.

The man was diagnosed with a variant of hypersensitivity pneumonitis -- feather duvet lung -- which is caused by breathing in organic dust from the duck or goose feathers found in duvets and pillows.

He was given a course of steroids to quell the inflammation and told to revert to synthetic bedding. After 12 months his symptoms had cleared up and his life had returned to normal.

This is just one case, and it's not known how common feather duvet lung is, say the authors, precisely because it is often missed as doctors rarely ask patients about feather bedding.

But in the first four months of 2015 alone, 7 million duvets were sold in the UK, they point out. And repeated exposure to the culprit trigger in hypersensitivity pneumonitis can lead to irreversible scarring of the lung tissue, so it's important to identify this promptly, they say.

Patrick Liu-Shiu-Cheong, Chris RuiWen Kuo, Struan WA Wilkie, Owen Dempsey. Feather duvet lung. BMJ Case Reports, 2019; 12 (11): e231237 DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2019-231237

Beyond The Green Revolution

November 19, 2019

There has been a substantial increase in food production over the last 50 years, but it has been accompanied by a narrowing in the diversity of cultivated crops. New research shows that diversifying crop production can make food supply more nutritious, reduce resource demand and greenhouse gas emissions, and enhance climate resilience without reducing calorie production or requiring more land.

The Green Revolution -- or Third Agricultural Revolution -- entailed a set of research technology transfer initiatives introduced between 1950 and the late 1960s. This markedly increased agricultural production across the globe, and particularly in the developing world, and promoted the use of high-yielding seed varieties, irrigation, fertilizers, and machinery, while emphasising maximising food calorie production, often at the expense of nutritional and environmental considerations. Since then, the diversity of cultivated crops has narrowed considerably, with many producers opting to shift away from more nutritious cereals to high-yielding crops like rice. This has in turn led to a triple burden of malnutrition, in which one in nine people in the world are undernourished, one in eight adults are obese, and one in five people are affected by some kind of micronutrient deficiency. According to the authors of a new study, strategies to enhance the sustainability of food systems require the quantification and assessment of tradeoffs and benefits across multiple dimensions.

In their paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers from IIASA, and several institutions across the US and India, quantitatively assessed the outcomes of alternative production decisions across multiple objectives using India's rice dominated monsoon cereal production as an example, as India was one of the major beneficiaries of Green Revolution technologies.

Using a series of optimisations to maximise nutrient production (i.e., protein and iron), minimise greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and resource use (i.e., water and energy), or maximise resilience to climate extremes, the researchers found that diversifying crop production in India would make the nation's food supply more nutritious, while reducing irrigation demand, energy use, and greenhouse gas emissions. The authors specifically recommend replacing some of the rice crops that is currently being cultivated in the country with nutritious coarse cereals like millets and sorghum, and argue that such diversification would also enhance the country's climate resilience without reducing calorie production or requiring more land. Researchers from IIASA contributed the design of the optimisation model and the energy and GHG intensity assessments.

"To make agriculture more sustainable, it's important that we think beyond just increasing food supply and also find solutions that can benefit nutrition, farmers, and the environment. This study shows that there are real opportunities to do just that. India can sustainably enhance its food supply if farmers plant less rice and more nutritious and environmentally friendly crops such as finger millet, pearl millet, and sorghum," explains study lead author Kyle Davis, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Data Science Institute at Columbia University, New York.

The authors found that planting more coarse cereals could on average increase available protein by 1% to 5%; increase iron supply by between 5% and 49%; increase climate resilience (1% to 13% fewer calories would be lost during times of drought); and reduce GHG emissions by 2% to 13%. The diversification of crops would also decrease the demand for irrigation water by 3% to 21% and reduce energy use by 2% to 12%, while maintaining calorie production and using the same amount of cropland.

"One key insight from this study was that despite coarse grains having lower yields on average, there are enough regions where this is not the case. A non-trivial shift away from rice can therefore occur without reducing overall production," says study coauthor Narasimha Rao, a researcher in the IIASA Energy Program, who is also on the faculty of the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

The authors point out that the Indian Government is currently promoting the increased production and consumption of these nutri-cereals -- efforts that they say will be important to protect farmers' livelihoods and increase the cultural acceptability of these grains. With nearly 200 million undernourished people in India, alongside widespread groundwater depletion and the need to adapt to climate change, increasing the supply of nutri-cereals may be an important part of improving the country's food security.

Davis K, Chhatre A, Rao N, Singh D, Ghosh-Jerath S, Mriduli A, Poblete-Cazenave M, Pradhan N, & DeFries R. Beyond the Green Revolution: Balancing multiple objectives for sustainable cereal production. PNAS, 2019 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1910935116

Disclaimer: These articles are not intended to provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Pittwater Online News or its staff.