Inbox and Environment News: Issue 447

April 26 - May 2, 2020: Issue 447

BIG TREES, BIG PROBLEMS

Cleaning Up Our Act: Redirecting The Future Of Plastic In NSW

- Phase out key single-use plastics

- Triple the proportion of plastic recycled in NSW across all sectors and streams by 2030

- Reduce plastic litter items by 25% by 2025

- Make NSW a leader in national and international research on plastics

20-Year Waste Strategy For NSW

- Generate less waste

- Improve collection and sorting

- Plan for future infrastructure

- Create end markets

Mining Sector Key To Recovery From Drought, Bushfires And COVID-19 In Regional NSW

Planning Changes To Support Growth In Renewable Energy Projects

Online Action - Stop Adani

Birding At Home In Pittwater: April 2020

Thank you to everyone for staying at home as much as possible to stop the spread of the virus and save lives. We know self-isolation can be challenging and stressful at times so what we need right now is nature.

We can be so grateful that no matter where you live, you can still see birds and take comfort from them.

Please visit their new Birding at Home page to find out how you and your household can continue to enjoy the beauty of our feathered friends.

You'll find activities to occupy kids while our movements are restricted, links to our Autumn Birds in Backyards survey and Bird Finder, and information on how you can act to protect birds forever.

To help everyone who is now Birding at Home, they are also kicking off a regular live series on Facebook where our bird experts will be taking questions and talking about what we love best - birds.

Even if you are an expert birder, we encourage you to join in for a chat – and please spread the word to all the bird and nature lovers in your life.

P.S. They'll be having new bird experts every week to talk about a new topic, including Amanda Lilleyman in the NT on shorebirds and Holly Parsons to talk about bird friendly gardens. Make sure you have liked them on Facebook to get notifications and join in the talks.

Curious Sulphur Crested Cockatoo Visits Pittwater Spotted Gum Tree Hollow

The Kookaburra Family: Mid To Late April 2020

Lorikeet Feasting On Flowering Pittwater Spotted Gums And Palm Blossoms

Port Kembla Gas Terminal Modification Approved

Stronger Protection For Sydney's Water Catchment Following Extensive Review

- Ensuring there is a net gain for the metropolitan water supply by requiring more offsetting from mining companies;

- Establishing a new independent expert panel to advise on future mining applications in the catchment;

- Strengthening surface and groundwater monitoring;Improving access to and transparency of environmental data;

- Adopting a more stringent approach to the assessment and conditioning of future mining proposals to minimise subsidence impacts;

- Reviewing and updating current and potential future water losses from mining in line with the best available science;

- Introducing a licensing regime to properly account for any water losses; and

- Undertaking further research into mine closure planning to reduce potential long-term impacts.

NSW Decarbonisation Innovation Study

- Technologies and services to reduce carbon emissions, adapt to or mitigate the impact of climate change in which NSW could have a competitive advantage

- The net value of these technologies and services for NSW in terms of both emissions reduction and economic growth

- Any barriers to the development of the technologies and services in NSW

- The role of the NSW Government in:

a.Addressing any of the identified barriersb. Supporting the acceleration of the development/commercialisation of these opportunities, andc. Ensuring that NSW takes advantage of carbon emission reduction technologies to maximise economic opportunities.

- Professor Hugh Durrant-Whyte (Chair)

- Professor Michael Dureau

- Professor Frank Jotzo

- Ms Meg McDonald

- Mr Roger Swinbourne

- Scoping Paper (March 2020) - © State of New South Wales through NSW Trade & Investment

Troubled Waters: WaterNSW Doubles Down On Criticism Of Dendrobium Expansion

- The additional surface water losses from the expansion would be up to 5.2 ML/day. WaterNSW is concerned that these predictions by the company may be underestimating the full extent of surface water losses from the catchment.

- Nine major watercourses and approximately 100 smaller tributaries are expected to experience fracturing as a result of the expansion, including the Avon and Cordeaux Rivers, which are downstream of the reservoirs and feed into Pheasants Nest Weir - a major component of the water supply system.

- Potential water quality impacts from the extensive stream fracturing that is predicted.

- Setbacks from the two dam walls (Cordeaux and Avon) should be increased to at least 1,500 metres due to potential far-field differential movements. “Should any impacts occur to these dams, there is the potential that the risks and consequences could be extreme.”

Sydney Councils Vote To Send Anti-Fracking Message To Origin Energy

Keelty Report Is A Balanced Response To Basin Dilemmas

Palaszczuk Government’s Arrow Energy Admiration Misses The Mark; Condemns Farmers

COVID-19 No Excuse To Open New Hope's Coal Mine

W.A. EPA Congratulated After Announcing Public Review For Gas-Seeking Seismic Surveys

These 5 images show how air pollution changed over Australia’s major cities before and after lockdown

Have you recently come across photos of cities around the world with clear skies and more visibility?

In an unexpected silver lining to this tragic crisis, urban centres, such as around Wuhan in China, northern Italy and Spain, have recorded a vastly lower concentration of air pollution since confinement measures began to fight the spread of COVID-19.

Likewise, the Himalayas have been visible from northern India for the first time in 30 years.

But what about Australia?

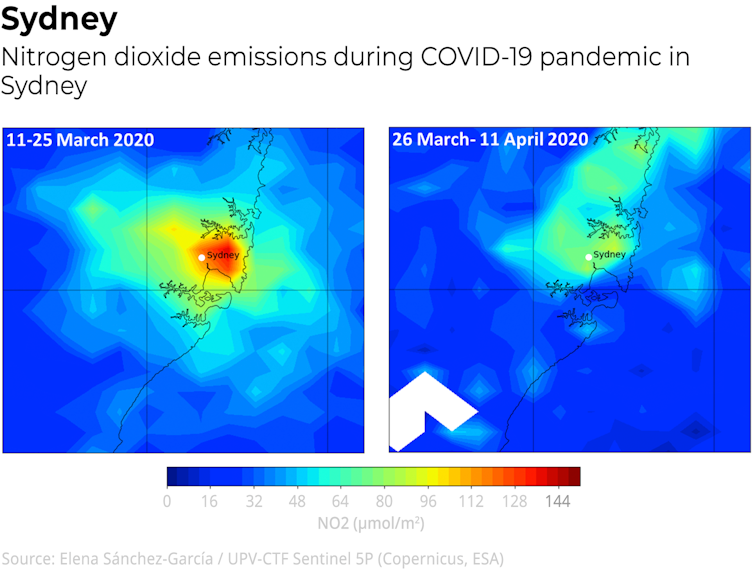

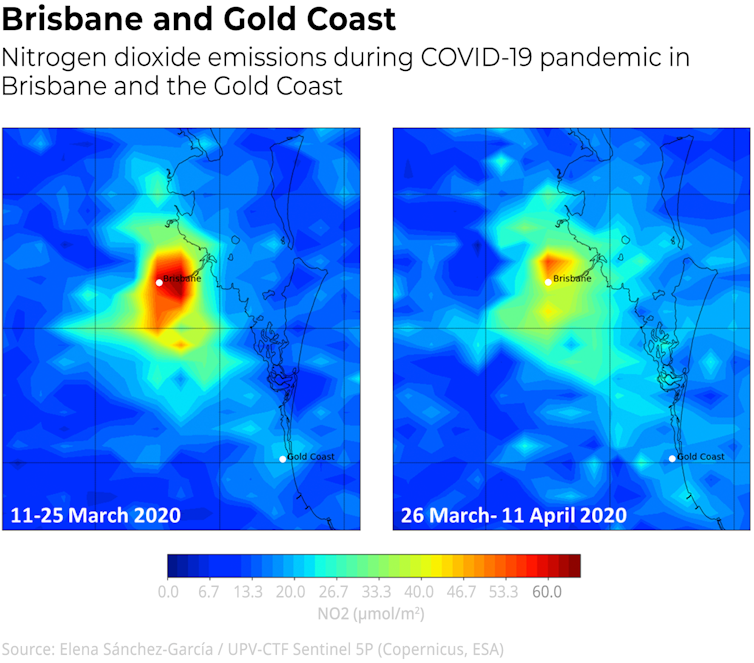

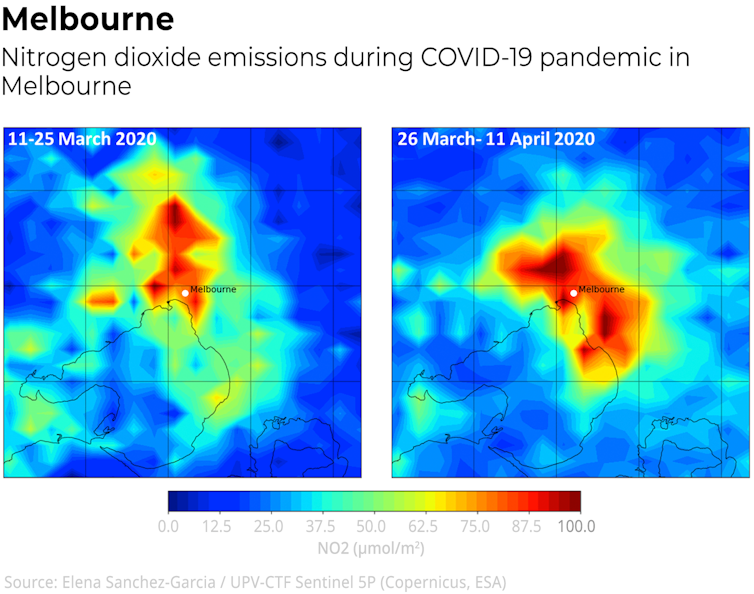

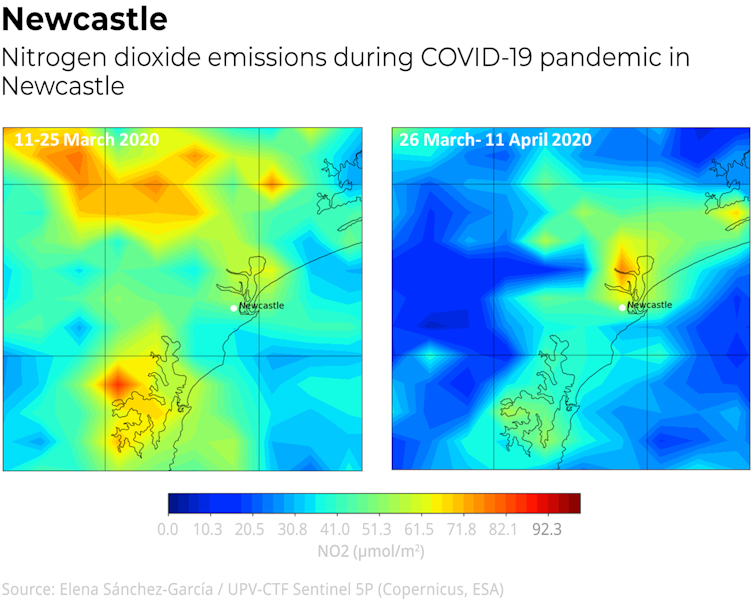

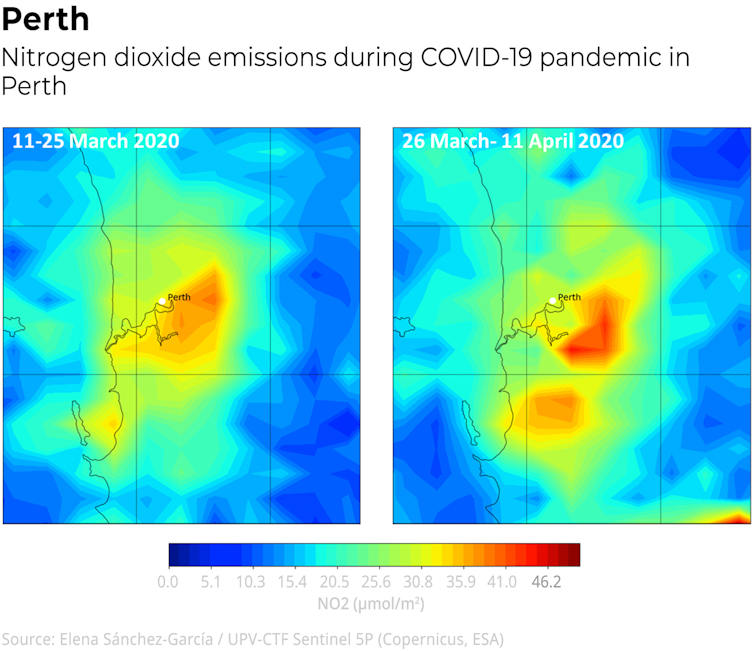

Researchers from the Land and Atmosphere Remote Sensing group at the Physical Technology Center in the Polytechnic University of Valencia – Elena Sánchez García, Itziar Irakulis Loitxate and Luis Guanter – have analysed satellite data from the new Sentinel-5P satellite mission of the Copernicus program of the European Space Agency.

The data shows a big improvement to pollution levels over some of our major cities – but in others, pollution has, perhaps surprisingly, increased.

These images measure level of nitrogen dioxide in the atmosphere, an important indicator of air quality. They show changes in nitrogen dioxide concentrations between March 11 to March 25 (before lockdown effectively began) and March 26 to April 11 (after lockdown).

Why Nitrogen Dioxide?

Nitrogen dioxide in urban air originates from combustion reactions at high temperatures. It’s mainly produced from coal in power plants and from vehicles.

High concentrations of this gas can affect the respiratory system and aggravate certain medical conditions, such as asthma. At extreme levels, this gas helps form acid rain.

Declining nitrogen dioxide concentrations across Europe in the northern hemisphere are normally expected around this time – between the end of winter and beginning of spring – due to increased air motion.

But the observed decreases in many metropolises across Europe, India and China since partial and full lockdowns began seem to be unprecedented.

Nitrogen Dioxide Levels Across Australia

Preliminary results of the satellite data analysis are a mixed bag. Some urban centres such as Brisbane and Sydney are indeed showing an expected decrease in nitrogen dioxide concentrations that correlates with the containment measures to fight COVID-19.

On average, pollution in both cities fell by 30% after the containment measures.

Like a heat map, the red in the images shows a higher concentration of nitrogen dioxide, while the green and yellow show less.

On the other hand, nitrogen dioxide concentrations have actually increased by 20% for Newcastle, the country’s largest concentration of coal-burning heavy industry, and by 40% for Melbourne, a sprawling city with a high level of car dependency. Perth does not show a significant change.

We don’t know why pollution has increased in these cities across this time period, as 75% of Melbourne’s pollution normally comes from vehicle emissions and most people are travelling less.

It could be because the autumn hazard reduction burns have begun in Melbourne. Or it may be due to other human activities, such as more people using electricity and gas while they stay home.

Pollution Changes With The Weather

Understanding how air pollution changes is challenging, and requires thorough research because of its variable nature.

We know atmospheric conditions, especially strong winds and rain, are a big influence to pollution patterns – wind and rain can scatter pollution, so it’s less concentrated.

Other factors, such as the presence of additional gases and particles lingering in the atmosphere – like those resulting from the recent bushfires – also can change air pollution levels, but their persistence and extent aren’t clear.

Read more: Even for an air pollution historian like me, these past weeks have been a shock

Changes Should Be Permanent

If the decrease in nitrogen dioxide concentration across cities such as Brisbane and Sydney is from containment measures to fight COVID-19, it’s important we try to keep pollution from increasing again.

We know air pollution kills. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates around 3,000 deaths per year in Australia can be attributed to urban air pollution.

Yet, Australia lags on policies to reduce air pollution.

Read more: Australia needs stricter rules to curb air pollution, but there's a lot we could all do now

COVID-19 has given us the rare opportunity to empirically observe the positive effects of changing our behaviours and slowing down industry and transport.

But to make it last, we need permanent changes. We can do this by improving public transport to reduce the number of cars on the road; electrifying mass transit; and, most importantly, replacing fossil fuel generation with renewable energy and other low-carbon sources. These changes would bring us immediate health benefits.![]()

Elena Sánchez-García, Postdoctoral researcher at LARS group, Universitat Politècnica de València and Javier Leon, Senior lecturer, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

While towns run dry, cotton extracts 5 Sydney Harbours' worth of Murray Darling water a year. It's time to reset the balance

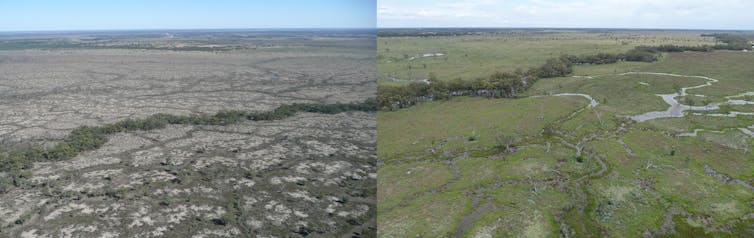

The rains have finally arrived in the Northern Murray Darling Basin. Hopefully, this drought-easing water will flow all the way down to the parched communities and degraded habitats of the lower Darling.

How much water goes downstream, however, does not just depend on how much it has rained.

It also greatly depends on how much is extracted and consumed upstream, and the rules and enforcement around these water extractions.

Simplistic or knee-jerk responses to water insecurity, such as banning irrigation for “thirsty crops” such as cotton, will not fix the water woes of the basin.

The harder and longer path is to deliver real water reform as was agreed to by all governments in the 2004 National Water Initiative and that includes transparent water planning enshrined in law.

Read more: The sweet relief of rain after bushfires threatens disaster for our rivers

Basin Cotton Irrigators Extract About Five Sydney Harbours’ Worth A Year

Irrigation accounts for about 70% of all surface water extracted in the basin.

Australia’s water accounts tell us that in 2017-18, basin cotton irrigators extracted some 2,500 billion litres (about five Sydney Harbours’ worth) or equivalent to about 35% of all the water extracted for irrigation.

Most of this water was extracted in the Northern Basin (covering southern Queensland and northern New South Wales). But increasingly cotton is becoming a preferred crop in the Southern Basin (southern NSW to South Australia).

Overall, the area of land in cotton and the water extracted for cotton increased by 4% in 2017-18 relative to 2016-17.

Cotton is a thirsty crop. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics cotton uses, on average, more than 7 million litres (or about three Olympic-sized swimming pools) per hectare.

At a global scale, the volume of water extracted by cotton irrigators to produce one kilogram of cotton fabric averages more than 3,000 litres.

Increased Water Efficiency: Good News For Some, Bad News For Others

Concerns over how much water cotton uses, and the high price of water in the basin, has incentivised cotton farmers to increase their cotton yield (in tonnes) per million litres of water extracted.

This has been achieved with improved genetics, management and more high-tech irrigation methods. According to Cotton Australia, much less water (only 19%) is flowing back into streams and groundwater from water applied to cotton fields than two decades ago, when the return flows were 43% of the water applied.

Increased irrigation efficiency is good news for cotton irrigators, especially those that received some of the A$4 billion in public money already spent to increase irrigation efficiency in the basin. But it is bad news for downstream irrigators, communities and the environment.

This is because a much greater proportion of the water extracted by cotton farmers now gets consumed as evapo-transpiration, and thus is unavailable for anyone or anything else.

We Need To Change The Rules Of The Game

Given these cotton facts, would banning the growing of cotton in Australia increase the water available? No – because the problem is not cotton irrigation per se, but rather the “rules of the game” of the who, how, and when water is extracted. These water sharing rules are determined at a state level in what are called Water Sharing Plans.

Proper water planning is the only way to ensure a fair deal, deliver on the intent of the 2012 Basin Plan and keep levels of water extraction at sustainable levels.

Water sharing plans are supposed to be consistent with the 2012 Basin Plan. But NSW has, so far, failed to provide its plans for auditing by the Murray-Darling Basin Authority, missing the key July 1, 2019 deadline.

Following an expose of alleged water theft in July 2017, the NSW government created a specialised agency, the Natural Resources Access Regulator, that has greatly helped water monitoring and compliance in NSW. Despite its best efforts, there is still inadequate metering in the Northern Basin. And across the basin as a whole, most groundwater extractions are not properly monitored.

The actual rules about how much water can be extracted are substantially influenced by some irrigators in the consultation process before plans are implemented.

Such influence has resulted in some water sharing plans favouring upstream irrigators at the expense of downstream communities, such as Walgett and Wilcannia. These towns have been left high and dry despite the fact NSW law gives priority to town water supplies over other water uses.

According to the NSW Natural Resources Commission, the current Barwon-Darling Water Sharing Plan “effectively prioritises upstream water users” and also does not provide protection for environmental water from extraction.

The Natural Resources Commission also observed that extraction permitted under the plan:

has affected those communities and landholders reliant on the river for domestic and stock water supplies, town water supply, community and social needs.

A consultant’s report from 2019, written for the NSW government, also found no evidence in the Barwon-Darling water planning processes of reporting on performance indicators such as changes in stream flow regimes, ecological values of key water sources or water utility (for town supply) access requirements.

Sadly, the problem of poor water planning is not exclusive to the Barwon-Darling, but exists in other basin catchments in NSW, and beyond.

Holding Governments Responsible

Any effective solution to the water emergency in the basin must, therefore, hold governments responsible for their water plans and decisions. This requires that a “who, what, how and when” of water be made transparent through an independent water auditing, monitoring and compliance process.

Simplistic responses to water insecurity, such as banning irrigation for cotton, will not fix the water woes of the basin. The harder and longer path is to deliver real water reform as was agreed to by all governments in the 2004 National Water Initiative and that included transparent water planning enshrined in law.

Read more: Fish kills and undrinkable water: here's what to expect for the Murray Darling this summer

Three Things That Would Make A Difference

As a nation we must hold decisionmakers accountable so the rules of the game do not favour the big end of town at the expense, and even the existence, of towns.

We also need to:

- stop wasting billions on irrigation subsidies that reduce flows to streams and rivers

- monitor, measure and audit what is happening to the water extracted and in streams

- actually deliver on the key objects of the federal Water Act and state water acts.

Enforcing the law of the land would ensure those who have the legal right to get the water first (such as town water supplies) are prioritised in the implementation of water sharing plans. It would mean state water plans are audited and actually deliver environmentally sustainable levels of water extraction.![]()

Quentin Grafton, Director of the Centre for Water Economics, Environment and Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s inland rivers are the pulse of the outback. By 2070, they’ll be unrecognisable

Inland Australia’s complex system of winding rivers, extensive wetlands, ancient waterholes and seemingly endless parched floodplains are rarely given more than a passing thought by many Australians who live on the coastal fringes.

Yet these waterways are lifelines along which communities, agriculture and trade have flourished.

Etched into the psyche of regional Australia, these river systems are the pulse of the outback. Before asking a local how things are going, peek over the bridge in town for an indication.

Read more: Sure, save furry animals after the bushfires – but our river creatures are suffering too

When relaxing in the shade of an old river red gum alongside one of Australia’s lazy inland rivers, it’s natural to think of them as timeless and resilient to environmental change.

Yet, these rivers evolved over millennia and continue to change over years and decades.

And we already know from previous studies that future climate change is likely to reduce stream flow and water availability in drylands around the world.

But what our new research has shown, for the first time, is that these declines in stream flow may trigger a dramatic change in the physical structure and function (the geomorphology) of Australia’s inland rivers.

Meandering Rivers And Flat, Wide Floodplains

The physical structure of a river depends on how much water flows through it, and the sediment that water carries.

Reductions in water flow – as expected due to climate change – can lead to a build-up of sediment downstream. In extreme cases, this “silting up” can cause complete disintegration of river channels, where water flows out across the floodplain.

Not all rivers are alike, and the rivers of the Murray-Darling and Lake Eyre basins (covering 1.8 million square kilometres) are particularly diverse. Many of these rivers and wetlands are internationally recognised for their hydrological and ecological importance.

Read more: No water, no leadership: new Murray Darling Basin report reveals states' climate gamble

They range from large meandering rivers swollen by seasonal spring flows (the Upper Murray, Mitta Mitta, Kiewa, and Ovens rivers), to rivers that progressively get smaller until they become exhausted on flat, wide floodplains and disintegrate into large, boom-and-bust wetlands (the Lachlan, Macquarie, and Gwydir rivers).

In the drier areas of central Australia, rivers typically persist as a string of isolated waterholes for years at a time, occasionally punctuated by very large floods (Warrego, Paroo, Diamantina, and Cooper Creek).

A Sobering Future

For Australia’s inland rivers, the average dryness, or “aridity”, of the catchment is the best predictor of what the overall structure and function of the rivers within look like.

Compiling a range of climatic data, we modelled aridity for the Australian continent in 2070 under a relatively moderate climate change scenario.

The results are sobering. Over the next 50 years, the arid zone – containing the areas of true desert – is projected to expand well into the Murray-Darling Basin and almost entirely envelope the Lake Eyre Basin.

At the same time, the humid and dry subhumid fringes around the Great Dividing Range and coastal areas are expected to contract.

This is concerning because the relatively wet western slopes of the Great Dividing Range are where many inland Australian rivers begin, with most of their water sourced in these smaller sub-catchments.

Evolution Of Our Inland Rivers

The impact of this projected drying pattern on Australia’s inland rivers is expected to be profound.

Despite only occupying around 3.8% of the Murray-Darling Basin, the Upper Murray, Mitta Mitta, Kiewa, and Ovens rivers presently provide a large amount of flow within the lower Basin (33% of average annual flows).

These rivers flow out of the southeastern highlands towards the Murray River, but over the next 50 years they’re expected to experience declining downstream flows. This leads to less efficient flushing of sediment downstream, which, in turn, will increase sediment deposition within these rivers, reducing their size.

Other rivers – such as the Murrumbidgee and Macintyre rivers – are expected to undergo even more dramatic changes to their structure and behaviour.

Right now these rivers maintain a winding course to the central Murray and Barwon rivers, respectively. But our projections suggest these continuous channels won’t be supported, and are likely to be interrupted by sections of channel breakdown.

Under a drier climate, rivers such as the Lachlan and Macquarie may come to resemble present-day central Australian rivers – only persisting as disconnected waterholes for long periods of time, with internationally important wetlands (Great Cumbung Swamp and Macquarie Marshes) much less frequently inundated.

Read more: The sweet relief of rain after bushfires threatens disaster for our rivers

Such changes to river structure and function will have long-lasting impacts on water, sediment, and nutrient distribution. This will likely change the dynamics of the river ecosystem, as well as the way we manage and use these rivers.

A Parched Future

While our research hasn’t investigated the potential ecological, socio-economic or cultural effects of structural changes, we can expect them to be very significant, and potentially irreversible.

Read more: Don't blame the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. It's climate and economic change driving farmers out

Many of Australia’s native aquatic and dryland flora and fauna are adapted to a highly variable climate regime, but there are limits beyond which these ecosystems cannot recover or survive. For example, seeds and invertebrate eggs can survive many years buried in dry soil waiting for a flood, but if water doesn’t come, eventually they won’t be viable.

What’s more, extracting too much water from our inland river systems for agriculture or other uses will exacerbate the threats posed by a drying climate.

Given the complexity and tensions surrounding water use and water sharing in Australia’s inland rivers, particularly in the Murray-Darling Basin, understanding how these critical systems might respond in the future is now more important than ever.

Water is one of the most contested resources in Australia, and it’s the fundamentally important river and wetland ecosystems and agricultural industries that will bear the brunt of a drying climate.

To make sure outback communities can continue to survive, it’s vital we protect their lifeline. Water resource planning must include consideration of climate change, as the projected changes will likely increase pressure on already vulnerable systems.![]()

Zacchary Larkin, Postdoctoral Researcher in Environmental Sciences, Macquarie University; Stephen Tooth, Professor of Physical Geography, Aberystwyth University, and Timothy J. Ralph, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

I travelled Australia looking for peacock spiders, and collected 7 new species (and named one after the starry night sky)

After I found my first peacock spider in the wild in 2016, I was hooked. Three years later, I was travelling across Australia on a month-long expedition to document and name new species of peacock spiders.

Peacock spiders are a unique group of tiny, colourful, dancing spiders native to Australia. They’re roughly between 2.5 and 6 millimetres, depending on the species. Adult male peacock spiders are usually colourful, while female and juvenile peacock spiders are usually dull brown or grey.

Read more: The spectacular peacock spider dance and its strange evolutionary roots

Like peacocks, the mature male peacock spiders display their vibrant colours in elegant courtship displays to impress females. They often elevate and wave their third pair of legs and lift their brilliantly coloured abdomens – like dancing.

Up until 2011, there were only seven known species of them. But since then, the rate of scientific discovery has skyrocketed with upwards of 80 species being discovered in the last decade.

Thanks to my trip across Australia and the help from citizen scientists, I’ve recently scientifically described and named seven more species from Western Australia, South Australia and Victoria. This brings the total number of peacock spider species known to science up to 86.

Spider Hunting: A Game Of Luck

Citizen scientists – other peacock spider enthusiasts – shared photographs and locations of potentially undocumented species with me. I pulled these together to create a list of places in Australia to visit.

I usually find spider hunting to be a relaxing pastime, but this trip was incredibly stressful (albeit amazing).

The thing about peacock spiders is they’re mainly active during spring, which is when they breed. Colourful adult males are difficult – if not impossible – to find at other times of year, as they usually die shortly after the mating season. This meant I had a very short window to find what I needed to, or I had to wait another year.

Even when they’re active, they can be difficult to come across unless weather conditions are ideal. Not too cold. Not too rainy. Not too hot. Not too sunny. Not too shady. Not too windy. As you can imagine, it’s largely a game of luck.

The Wild West

I arrived in Perth, picked up my hire car and bought a foam mattress that fitted in the back of my car – my bed for half of the trip. I stocked up on tinned food, bread and water, and I headed north in search of these tiny eight-legged gems.

My first destination: Jurien Bay. I spent the whole day under the hot sun searching for a peculiar, scientifically unknown species that Western Australian photographer Su RamMohan had sent me photographs of. I was in the exact spot it had been photographed, but I just couldn’t find it!

The sun began to lower and I was using up precious time. I made what I now believe was the right decision and abandoned the Jurien Bay species for another time.

I spent days travelling between dramatic coastal landscapes, the rugged inland outback, and old, mysterious woodlands.

I hunted tirelessly with my eyes fixed on the ground searching for movement. In a massive change of luck from the beginning of my trip, it seemed conditions were (mostly) on my side.

With the much-appreciated help of some of my field companions from the University of Hamburg and volunteers from the public, a total of five new species were discovered and scientifically named from Western Australia.

The Little Desert

Two days after returning from Western Australia, I headed to the Little Desert National Park in Victoria on a Bush Blitz expedition, joined by several of my colleagues from Museums Victoria.

I’d thought the landscape’s harsh, dry conditions were unsuitable for peacock spiders, as most described species are known to live in temperate regions.

To my surprise, we found a massive diversity of them, including two species with a bigger range than we thought, and the discovery of another species unknown to science.

This is the first time two known species – Maratus robinsoni and Maratus vultus – had been found in Victoria. Previously, they had only been known to live in eastern New South Wales and southern Western Australia respectively.

Read more: Don't like spiders? Here are 10 reasons to change your mind

Our findings suggest other known species may have much bigger geographic ranges than we previously thought, and may occur in a much larger variety of habitats.

And our discovery of the unknown species (Maratus inaquosus), along with another collected by another wildlife photographer Nick Volpe from South Australia (Maratus volpei) brought the tally of discoveries to seven.

What’s In A Name?

Writing scientific descriptions, documenting, and naming species is a crucial part in conserving our wildlife.

Read more: Spiders are a treasure trove of scientific wonder

With global extinction rates at an unprecedented high, species conservation is more important than ever. But the only way we can know if we’re losing species is to show and understand they exist in the first place.

- Maratus azureus: “Deep blue” in Latin, referring to the colour of the male.

- Maratus constellatus: “Starry” in Latin, referring to the markings on the male’s abdomen which look like a starry night sky.

- Maratus inaquosus: “Dry” or “arid” in Latin, for the dry landscape in Little Desert National Park this species was found in.

- Maratus laurenae: Named in honour of my partner, Lauren Marcianti, who has supported my research with enthusiasm over the past few years.

- Maratus noggerup: Named after the location where this species was found: Noggerup, Western Australia.

- Maratus suae: Named in honour of photographer Su RamMohan who discovered this species and provided useful information about their locations in Western Australia.

- Maratus volpei: Named in honour of photographer Nick Volpe who discovered and collected specimens of this species to be examined in my paper.

These names allow us to communicate important information about these animals to other scientists, as well as to build legislation around them in the case there are risks to their conservation status.

I plan on visiting some more remote parts of Australia in hopes of finding more new peacock spider species. I strongly suspect there’s more work to be done, and more peacock spiders to discover.![]()

Joseph Schubert, Entomology/Arachnology Registration Officer, Museums Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The green gig economy: precarious workers are on the frontline of climate change fight

Sango Mahanty, Australian National University and Benjamin Neimark, Lancaster UniversityPoliticians and business people are fond of making promises to plant thousands of trees to slow climate change. But who actually plants those trees, and who tends them as they grow?

The hard and dirty work of restoring ecosystems will be invaluable in coming decades, to soak up carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, ease the impact of storms and flooding and harbour embattled wildlife. But this work – where it currently exists – is carried out by people who are often poorly paid, or not compensated at all.

Most often, these aren’t recognised workers, but instead, volunteers. This is not only the case for conservation workers in rural areas of Madagascar and Cambodia, but also in cities where waste collectors and people who recycle electronic waste work in abject poverty.

The situation is more dire for those battling the natural disasters that are proliferating in the warming climate. The 2018 wildfire season in California was the deadliest in the state’s history, but much of the fire fighting relied on 2,000 prison inmates who earned just USD$1 a day.

During Australia’s “black summer” of 2019-20, Prime Minister Scott Morrison rejected calls for support payments to 195,000 volunteer firefighters because, in his words, “they want to be there”.

The UK is braced for a future in which flooding is more frequent and severe. But the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) relies heavily on volunteer labour to manage these floods when they occur, and that’s set to remain the case.

These workers lack the proper pay and protections of an organised workforce, yet their services are increasingly in demand. Collectively, they form an emerging “eco-precariat” that bears little resemblance to the labour movement that’s urgently needed to mitigate the climate and ecological crisis.

Read more: Unions can – and will – play a leading role in tackling the climate crisis

Precarity In The Green Economy

The modern “gig economy” sells independence to workers by allowing them to decide their own work hours. For taxi drivers or couriers, this may sound appealing, but in practice it can mean a precarious existence, trapped with a variable income and permanently on call in zero-hour contracts. Those with an uncertain immigration status can fall into forms of modern day slavery.

Our research studied labour practices in the green economy and in particular, the schemes in which people and organisations “buy” green services, like ecosystem conservation and tree planting.

These projects range from direct payments to governments for forest and mangrove protection, to carbon markets, in which credits are sold to finance conservation work. A growing number of corporations pay to offset the local environmental damage they cause this way - enabling them to neglect action to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions. There’s even a smartphone app that will “plant a tree” at the touch of a button.

The idea of trees being planted at the touch of a screen sounds revolutionary. But this work tends to draw on a flexible labour pool – a sort of “green gig economy”. While private sector donations are funnelled through charities and NGOs overseeing the tree planting, the work itself is offered on a temporary basis, often to unpaid volunteers – including school children - who are deployed to plant and care for the trees.

Even as local people are enlisted to manage tree planting, they find their access to these areas restricted. In some cases, tree planting initiatives have uprooted communities and repossessed their land.

Read more: Greenwashing: corporate tree planting generates goodwill but may sometimes harm the planet

Essential Workers

As the pandemic has shown, volunteers and community groups can hold the social fabric together in times of crisis. Whether it’s ordinary people creating medical equipment or caring for neighbours in quarantine, community action can save lives where years of austerity have starved emergency services of the necessary resources for dealing with disasters.

The same can be said of volunteer fire fighters and foresters, but cheering on their selflessness isn’t enough. We should recognise where labour arrangements have created precarious working conditions, or enabled governments to shift their responsibilities onto the public.

Will volunteer fire fighters continue to go without compensation, even as their work becomes more dangerous in Australia’s increasingly fierce wildfire seasons? As governments consider how to revive the global economy after the COVID-19 pandemic, what legal protections can workers in new environmental projects depend on?

Now more than ever, it’s time for a frank discussion about what essential workers deserve in return for the invaluable work they do.![]()

Sango Mahanty, Associate Professor, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University and Benjamin Neimark, Senior Lecturer, Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A decade after the Deepwater Horizon explosion, offshore drilling is still unsafe

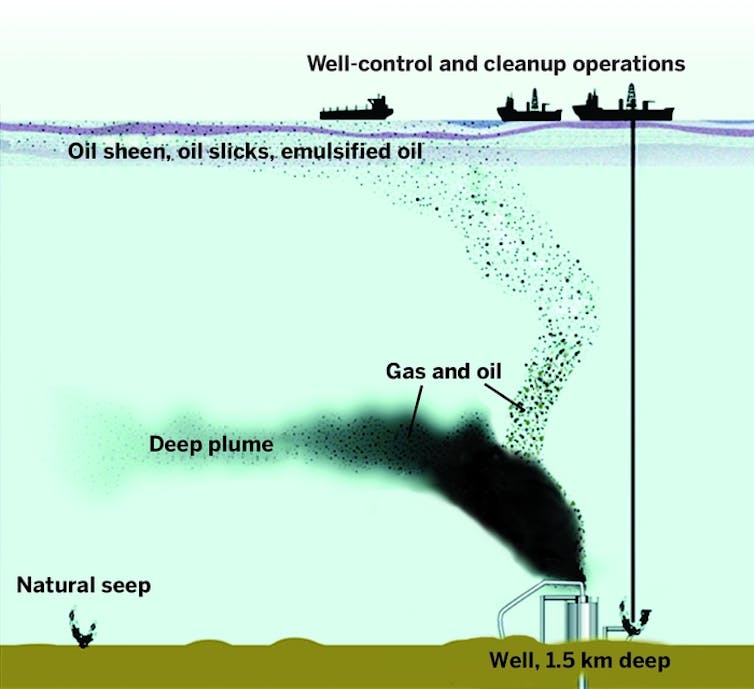

Ten years ago, on April 20, 2010, the BP Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded, killing 11 crew members and starting the largest ocean oil spill in history. Over the next three months, between 4 million and 5 million barrels of oil spewed into the Gulf of Mexico.

I was a member of the oil spill commission appointed by President Obama to investigate the causes of the disaster. Later, I served as a courtroom witness for the government on the effects of the spill. While scientists now know more about these effects, risks of deepwater blowouts remain, and the energy industry and government responders still have only very limited ability to control where the oil goes once it’s released from the well.

The spill commission found that multiple identifiable mistakes caused the blowout. Our report cast doubt over how safety was addressed across the offshore oil industry and the government’s ability to regulate it.

As the oil spill commission’s report showed, drilling ever deeper into the Gulf involved risks for which neither industry nor government was adequately prepared. The industry had felt so sure that a blowout would not happen that it lacked the capacity to contain it. Neither BP nor the government could do much to control or clean up the spill.

Safety Improvements Are Threatened

The presidential commission recommended numerous reforms to reduce the risks and environmental damages from offshore oil and gas development. The industry developed systems to contain blowouts in deep water and has deployed them worldwide. Improvements in operational safety were made within companies and across the industry.

The Department of the Interior acted quickly to reorganize its units. It created a Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement to avoid conflicts of interests with its leasing, development and revenue collection responsibilities. After four years in development, the bureau issued new well control rules in 2016 governing drilling safety.

But despite progress on a number of fronts, Congress has not enacted legislation to improve safety or even raise energy companies’ ridiculously low liability limits for oil spills – currently just US$134 million for offshore facilities like the Deepwater Horizon. The Trump administration has reversed or relaxed safety reforms. It has loosened the safe pressure margins allowed in a well, dispensed with independent inspections of blowout protectors and removed requirements for continuous onshore monitoring of offshore drilling.

Some of these changes were ordered by political appointees over the recommendations of the safety bureau’s technical experts. While the bureau is charged with focusing singularly on safety and the environment, its director, Scott Angelle, has been a prominent proponent of the administration’s aggressive “energy dominance” strategy, ordering expanded oil production and elimination of costly regulations. Imagine the message this sends about priorities to people in government and industry who are responsible for ensuring safety.

Where Contamination Lingers

Before the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the deep Gulf of Mexico ecosystem was egregiously understudied in all respects, while a multi-billion-dollar industry. intruded into it. Now scientists know much more about what happens when large quantities of oil and gas are released in a seafloor blowout.

Scientists learned much about the effects of the spill through monitoring the blowout, assessing damages to natural resources and investigating the fate and effects of escaping oil. More has been spent on these studies and more results published than for any previous oil spill.

A substantial portion of oil released from the mile-deep well was entrained in a plume of droplets spreading out 3,000 feet below the Gulf’s surface. Footprints of contamination and effects extended far beyond the area where oil slicks were observed.

Nearly all of the oil released has since degraded. Populations of most affected organisms have recovered. But contamination lingers in sediments in the deep Gulf, and in some marshes and beaches where oil came ashore. Populations of long-lived animals the oil killed might not recover for decades. These include sea turtles, bottlenose dolphins, seabirds and deepwater corals.

And yet, as scientists synthesize results from this 10-year research initiative, very little practical advice is emerging about what can be done to respond more effectively to future blowouts from ever-deeper drilling in the Gulf.

Surely, we can more rapidly contain blowouts. The effectiveness of injecting chemical dispersants into the plume gushing from the well remains in debate. How much oil do dispersants keep from reaching the surface, where it threatens those working to stanch the blowout, as well as birds, sea turtles and coastal ecosystems? But the research has not revealed more effective approaches in controlling released oil.

Safety First Is The Big Lesson

As I see it, the essential lesson from Deepwater Horizon is that industry and government should be putting their greatest energies into preventing operational accidents, blowouts and releases. Yet the Trump administration emphasizes increasing production and reducing regulations. This undermines safety improvements made over the past 10 years.

Furthermore, the price of crude oil – already low because of high fracked oil production in the U.S. – has declined drastically since the beginning of 2020. Saudi and Russian oil had already glutted the market when the coronavirus pandemic reduced oil consumption.

The federal government’s March 2020 oil and gas lease sale for the Gulf of Mexico yielded the lowest response in four years – $93 million in high bids, compared to $159 million in the previous round. To prop up the industry and maintain production, the Trump administration is seeking to lower royalty rates and store excess production in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

But as industry acts to cut its expenditures and downsize staff, will safety costs be a priority?

National energy policy was beyond the charge of the 2010 commission, but 10 years later, it is impossible to consider the future of offshore oil and gas without factoring in the need to eliminate net greenhouse gas emission within 30 years to limit climate change. Why would the United States consider expanding offshore exploration and drilling that might yield fossil fuels only 20 years from now?

Even in the historically developed Gulf of Mexico, rather than just “drill, baby, drill,” I believe the U.S. should be developing a realistic transition plan for phasing out offshore fossil fuel production. Such a strategy should encompass not only ensuring high standards for safety and industry responsibility for abandoned infrastructure during the drawdown, but also an economic evolution for the region, including opportunities for carbon sequestration and renewable energy production. We need to ensure that there will be a vibrant and productive Gulf long after we cease removing its oil.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]![]()

Donald Boesch, Professor of Marine Science, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Even If The Parks Are Closed You Can Still Go Google Trekking

A few years ago Pittwater Online shared some great news about the state government working with Google in what is called 'Google Trekker' - our own local MP, Rob Stokes, Member for Pittwater was the State Environment Minister at that time, so it was great to hear about this first-hand from him - he loves the great outdoors!

Back in June 2014 the work began of mapping our National Parks - by actually walking through them with a camera - this is what the ranger walking with the camera looked like - they started with doing 16 parks to begin with:

OEH - NPWS photo

Then in November 2014 Environment Minister Rob Stokes launched Google Street View imagery of some of the most picturesque and visited national parks in NSW.

Mr Stokes said the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service is the first organisation in Australia to be part of the Google program, which sees organisations borrow the Trekker technology to collect imagery of hard to reach places and help map the world.

“NPWS have captured 360-degree imagery of 25 parks from Kosciuszko to Cape Byron, covering over 400 kilometres of walking tracks and 700 kilometres of roads and trails,” Mr Stokes said then.

“This new service means people can scope out walks before they travel, or get a glimpse of places they would otherwise find inaccessible.

“People who have been unable to make it to the bottom of that gorge or the top of that ridge can now see all the sites our national parks have to offer.

"In conjunction with the NSW National Parks website, this imagery will give people another great way to plan their park visits, check walking tracks for suitability and learn about the area beforehand.

“We have a lot to be proud of in NSW with some of the most beautiful and remote places on the planet.

“These maps will ensure people who may not have the ability to walk in some of these popular locations will still have the opportunity to experience our vast natural beauty from their lounge rooms on the other side of the world.”

Basically, Google Trekker allows you to explore our National Parks as though you were on their bush tracks. You can Discover new places with a virtual tour of walking tracks, lookouts and campgrounds on the coast, deep within rainforests, and even in Outback NSW. You can get 360 degree views of these incredible landscapes and go on your own virtual adventure.

Working in partnership with Google, NSW National Parks (NPWS) has captured imagery in over 50 national parks using Google's special backpack-mounted trekker. With more than 1350km of Google Trekker footage, there are hundreds of experiences to discover.

You can also visit beautiful and historic places all over the world via Google Trekker - but let's start with places around us to begin with.

Where would you like to visit today?: Here are some of our favourite Street View virtual tours - just click on the links to take a look around for yourself

Sydney and Surrounds

- Aboriginal Heritage walk in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

- Barrenjoey Lighthouse and Headland in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

- Bouddi Coastal walk in Bouddi National Park

- Bradleys Head to Chowder Bay walking track in Sydney Harbour National Park

- Cliff Top walking track in Blue Mountains National Park

- Henry Head walking track in Kamay Botany Bay National Park

- O'Hares Creek lookout in Dharawal National Park

- The Coast track in Royal National Park

North Coast NSW

- Barrington trail in Barrington Tops National Park

- Cape Byron walking track in Cape Byron State Conservation Area

- Crowdy Gap campground in Crowdy Bay National Park

- Pinnacle walk and lookout in Border Ranges National Park

- Tomaree Head summit walk in Tomaree National Park

- Sea Acres Boardwalk in Sea Acres National Park

- Yuraygir coastal walk in Yuraygir National Park

South Coast NSW

- Light to Light walk in Ben Boyd National Park

- Montague Island walking track in Montague Island Nature Reserve

- Pigeon House Mountain Didthul walking track in Morton National Park

- Pretty Beach to Snake Bay walking track in Murramarang National Park

- Robertson lookout in Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area

- White Sands walk and Scribbly Gum track in Jervis Bay National Park

Country NSW

- Belougery Split Rock walking track in Warrumbungle National Park

- Breadknife and Grand High Tops walking track in Warrumbungle National Park

- Kanangra Boyd lookout in Kanangra-Boyd National Park

- The Lookdown lookout in Bungonia National Park

- West Rim walking track in Morton National Park

Snowy Mountains- Kosciuszko National Park

- Jillabenan Cave at Yarrangobilly Caves

- Kosciuszko walk - Thredbo to Mount Kosciuszko

- Mount Kosciuszko summit walk

- Perisher

- Snow Gums Boardwalk

- South Glory Cave at Yarrangobilly Caves

- Thredbo Alpine Village

Outback NSW and Murray-Riverina

- Mungo self-guided drive tour in Mungo National Park

- Valley of the Eagles walk in Gundabooka National Park

- Walls of China in Mungo National Park

Please note: The backpack-mounted trekker has been specifically designed to go off the grid. Occasionally, trained NPWS staff take Google Trekker into ecologically sensitive areas so we can give you a peek of places you would otherwise never see.

When you explore these walking tracks for yourself, remember to always to stay on marked tracks, so we can continue to protect these special places for generations to come.

Weed Cassia Now Flowering: Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

Please Help Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Donate Your Cans And Bottles And Nominate SW As Recipient

You can Help Sydney Wildlife help Wildlife. Sydney Wildlife Rescue is now listed as a charity partner on the return and earn machines in these locations:

- Pittwater RSL Mona Vale

- Northern Beaches Indoor Sports Centre NBISC Warriewood

- Woolworths Balgowlah

- Belrose Super centre

- Coles Manly Vale

- Westfield Warringah Mall

- Strathfield Council Carpark

- Paddy's Markets Flemington Homebush West

- Woolworths Homebush West

- Caltex Concord road Concord West

- Bondi Campbell pde behind Beach Pavilion

- Westfield Bondi Junction car park level 2 eastern end Woolworths side under ramp

- UNSW Kensington

- Enviro Pak McEvoy street Alexandria.

Every bottle, can, or eligible container that is returned could be 10c donated to Sydney Wildlife.

Every item returned will make a difference by removing these items from landfill and raising funds for our 100% volunteer wildlife carers. All funds raised go to support wildlife.

It is easy to DONATE, just feed the items into the machine select DONATE and choose Sydney Wildlife Rescue.

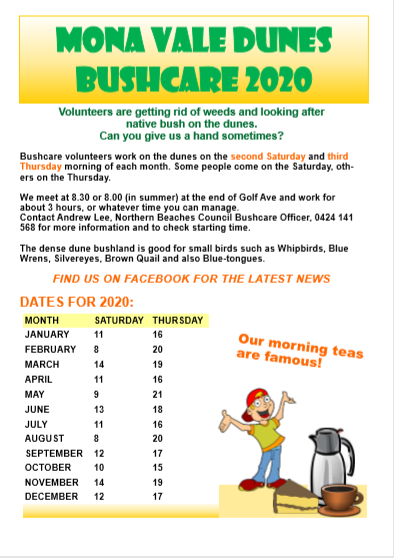

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Pittwater Reserves

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Sparkling dolphins swim off our coast, but humans are threatening these natural light shows

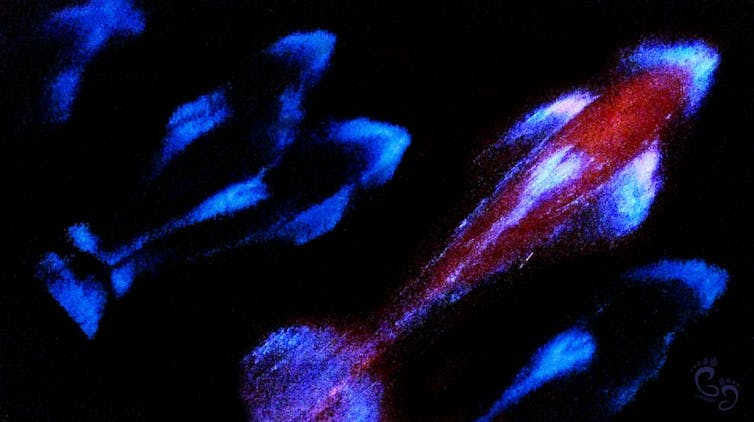

It was 2 am on a humid summer’s night on Sydney’s coast. Something in the distance caught my eye – a pod of glowing dolphins darted towards the bow of the boat. I had never seen anything like it before. They were electric blue, trailing swaths of light as they rode the bow wave.

It was a stunning example of “bioluminescence”. The phenomenon is the result of a chemical reaction in billions of single-celled organisms called dinoflagellates congregating at the sea surface. These organisms are a type of phytoplankton – tiny microscopic organisms many sea creatures eat.

Read more: Framing the fearful symmetry of nature: the year's best photos of landscapes and living things

Dinoflagellates switch on their bioluminescence as a warning signal to predators, but it can also be triggered when they’re disturbed in the water – in this case, by the dolphins.

You can see marine bioluminescence from land in Australia. Places like Jervis Bay and Tasmania are renowned for such spectacles.

But this dazzling night-time show is under threat. Light pollution creates brighter nights and disrupts ecological rhythms along the coast, such as breeding and feeding patterns. With so much human activity close to the shore and at sea, how much longer can we continue to enjoy this natural light show?

Lighting Up The World Has An Ecological Price

Light pollution is a well-known problem for inland ecosystems, particularly for nocturnal species.

In fact, a global study published earlier this year identified light pollution as an extinction threat to land bioluminescent species. The study surveyed firefly experts, who considered artificial light to be the second greatest threat to fireflies after habitat destruction.

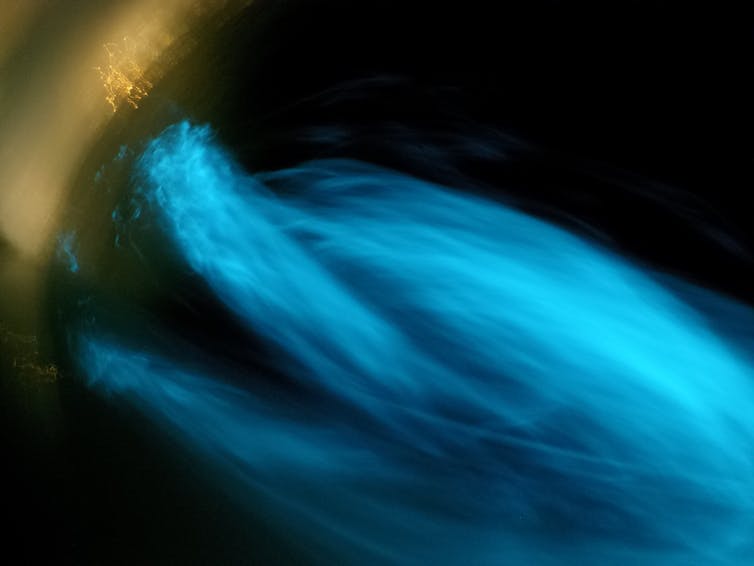

At sea, artificial light pollution enters the marine environment temporarily (lights from ships and fishing activities) and permanently (coastal towns and offshore oil platforms). To make matters worse, light from cities can extend further offshore by scattering into the atmosphere and reflecting off clouds. This is known as artificial sky glow.

For organisms with circadian clocks (day-night sleep cycles), this loss of darkness can have damaging effects.

For example it can disrupt animal metabolism, which can lead to weight gain. Artificial light can also change sea turtle nesting behaviour and can disorientate turtle hatchlings when trying to get to sea, lowering their chances of survival.

Read more: Lights out! Clownfish can only hatch in the dark – which light pollution is taking away

It can also disorientate the foraging of fish communities; alter predatory fish behaviour (such as in Yellowfin Bream and Leatherjacks) leading to increased predation in artificial light at night; cause reproductive failure in clownfish; and change the structural composition of marine invertebrate communities.

For zooplankton – a vital species for a range of bigger animals – artificial light disrupts their “diel vertical migration”. This term refers to the movement of zooplankton from the depths of the ocean where they spend the day to reduce fish predation, rising to the surface at night to feed.

What Does This Mean For Bioluminescent Species?

Increased exposure to artificial light due to human activities, such as growing cities and increased global shipping movement, may disrupt when and where bioluminescent species hang out.

In turn, this may influence where predators move, leading to disruptions in the marine food web, potentially changing the dynamics of energy transfer efficiency between marine species.

Bioluminescence usually serves as a communication function, such as to warn off predators, attract a mate or lure prey. For many species, light pollution in the ocean may compromise this biological communication strategy.

And for light-producing organisms such as dinoflagellates, excess artificial light may reduce the effectiveness of their bioluminescence because they won’t shine as bright, potentially increasing their risk of being eaten.

A 2016 study in the Arctic revealed the critical depth where atmospheric light dims to darkness, and bioluminescence from organisms becomes dominant, was approximately 30 metres below the sea surface.

This means any change to light in the Arctic influences when marine organisms rise to the surface. If there is too much light, these organisms remain deeper for longer where it’s safe – reducing their potential feeding time.

Read more: Bright city lights are keeping ocean predators awake and hungry

What Can We Do?

Understanding the level at which artificial light penetrates the ocean is tricky, especially so when dealing with mobile sources of light pollution such as ships, which are becoming an almost permanent fixture in some areas of the ocean.

Pockets of darkness still remain in our oceans. But they are becoming rarer, making light pollution a serious global threat to marine life.

Read more: The glowing ghost mushroom looks like it comes from a fungal netherworld

The spectacle of glowing dolphins should serve as a timely reminder of our need to conserve the darkness we have left.

Simple steps at home such as switching off lights and reducing unnecessary outdoor lighting, especially if you live near the ocean, is a step in the right direction to doing your bit for nocturnal species.![]()

Dr Vanessa Pirotta, Marine scientist and science communicator, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

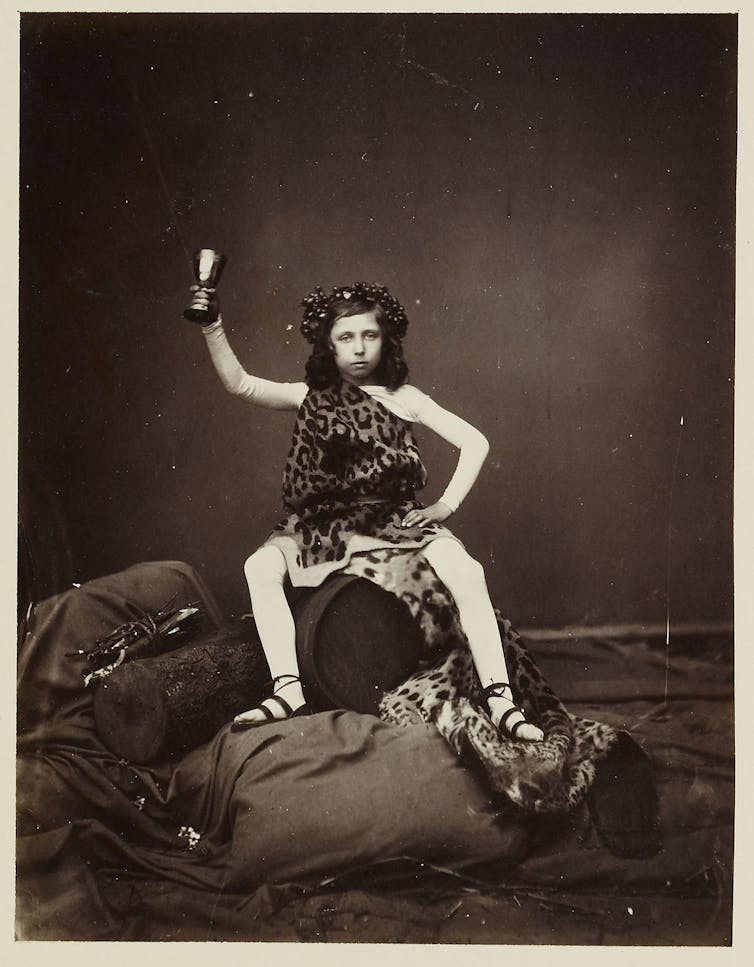

Recreating masterpieces at home? People have been doing it for centuries

Famous paintings are flooding the internet – but not as we are accustomed to seeing them. These are not just reproductions. Literally coming to life, paintings are being re-enacted at home with art lovers posing their way into everything from Girl with a Pearl Earring to American Gothic.

Given social distancing, it’s not surprising portraits are the favoured genre. Being home-bound also means using what is available: a bath towel in the place of a luxurious Renaissance dress; pots and pans instead of medieval headgear; pets taking on surprising roles.

These images invoke a humorous game of spot the difference. One especially cheeky example shows a couple recreating a detail from Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, with Bosch’s bizarre and whimsical world matched by contemporary verve.

These recreations are not just rooted in the boredom of quarantine. The impulse to recreate paintings has a long history that speaks to a need for shared cultural touchstones – and their subversion.

Parlour Games

The recreation of famous paintings, or tableaux vivants (literally “living pictures”), was a party game in aristocratic circles in 18th-century France. The phenomenon then spread throughout Britain, Europe and America.

In Australia, there are records of these tableaux being enacted in theatres and households from the 1830s.

An 1871 American publication, Parlor Tableaux and Amateur Theatricals, capitalises on “the great desire among the rising generation to participate in this simple and elegant amusement”. It includes painstaking instructions for an evening of entertainment, including the number of tableaux (five to ten), types (classical and contemporary) and genres (serious and comic).

Curtains would roll up to the spectacle of costumed figures posing with props and backgrounds from paintings by artists such as Titian, Michelangelo and Rembrandt. Shouts of appreciation or guessing games would ensue, with guests showing their knowledge of art history (or lack thereof).

The game was like charades, but silent and immobile. Part of the trick was the act of physical control needed to maintain the pose until the curtains rolled down and the actors prepared for another tableau.

Cultural Touchstones

Dress-up and posing have been documented as far back as classical antiquity. In festive pageantry of medieval and Renaissance Europe, parades and processions by rulers featured tableaux that were charged with important political and didactic functions.

Perhaps the most spectacular example of a tableau occurred in 1458 on the entry of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, into Ghent. A contemporary account describes how over a hundred citizens greeted Philip the Good and his entourage in a recreation of the city’s celebrated altarpiece, Jan and Hubert van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (The Ghent Altarpiece), painted in 1432.

This brilliant and complex polyptych presents a summation of Christian theology; its recreation would have been an incredibly ambitious undertaking.

The Ghent Altarpiece functioned as a shared cultural touchstone that its citizens could relate to. Only the nude figures of Adam and Eve would have been exempt from the recreation.

Controversy And Subversion

This was unlike the later tableaux of Victorian societies, when female nudes were acceptable and even encouraged. During the late 19th century, morality laws were evaded by the stillness of the models: as long as the women weren’t moving, they could present the tableaux as art education, rather than titillation.

In defence of these displays, the American poet Walt Whitman wrote if the sight of these tableux is considered “indecent” then:

the sight of nearly all the great works of painting and sculpture […] is, likewise, indecent. It is a sickly prudishness that bars all appreciation of the divine beauty evidenced in Nature’s cunningest work – the human frame, form and face.

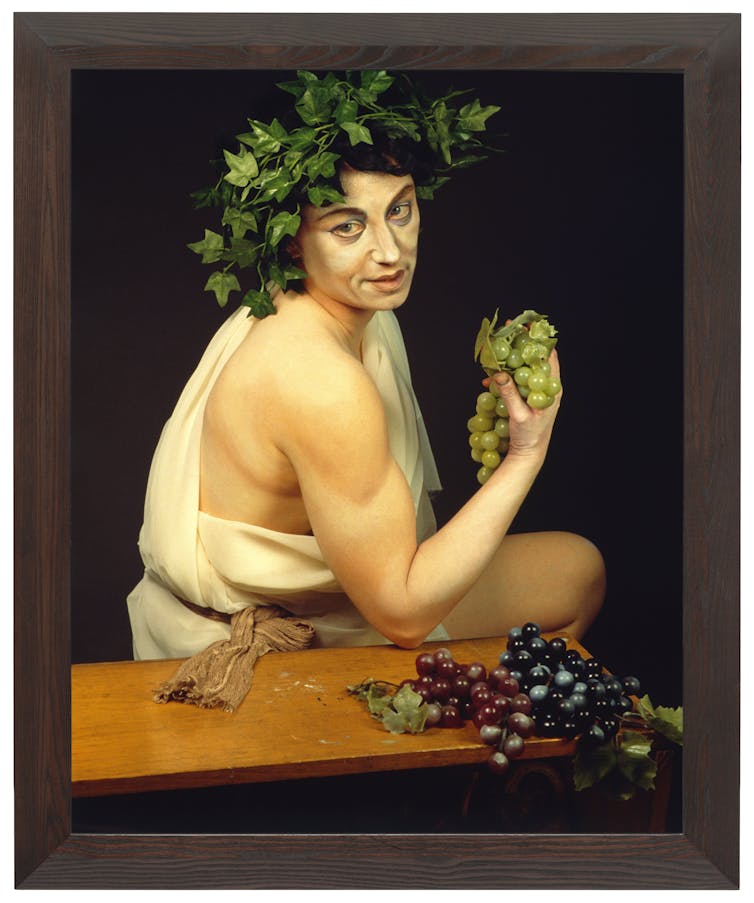

Later tableaux created by well-known artists stem from very different motivations, from satire to critique.

Pier Paolo Passolini’s La Ricotta shows the making of several tableaux of mannerist paintings for comic effect. Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #224 from 1990 is an appropriation of Caravaggio’s Young Sick Bacchus created four centuries earlier.

In her re-enactment, Sherman uses make-up, prosthetics and props – yet there is never any doubt that we are looking at Sherman. Her appropriation raises important questions about identity, feminism and the status of images.

Art Matters

In our era of self-isolation, institutions like the Getty are requesting recreations of works from their collections.

From homage to subversion, these recreations incite in us that jolt of recognition, nods of appreciation and boisterous laughter.

Most of all, tableaux vivants highlight an interest in shared cultural knowledge: an assumption that icons of art matter; that looking at and thinking about art is an essential activity.

As we face down weeks and even months in our homes, there also is a compelling participatory element: why just look at a masterpiece when you can be one?![]()

Andrea Bubenik, Senior Lecturer in Art History, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

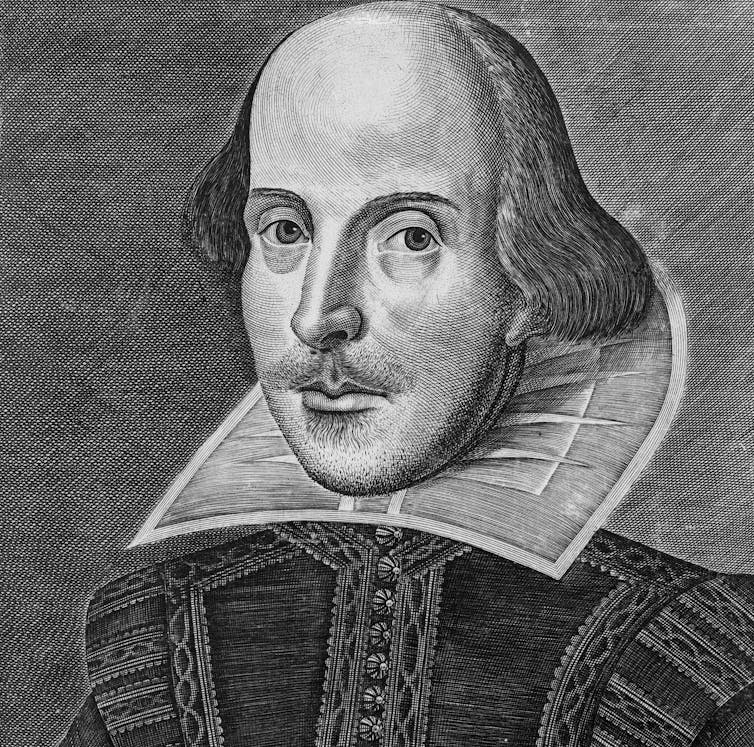

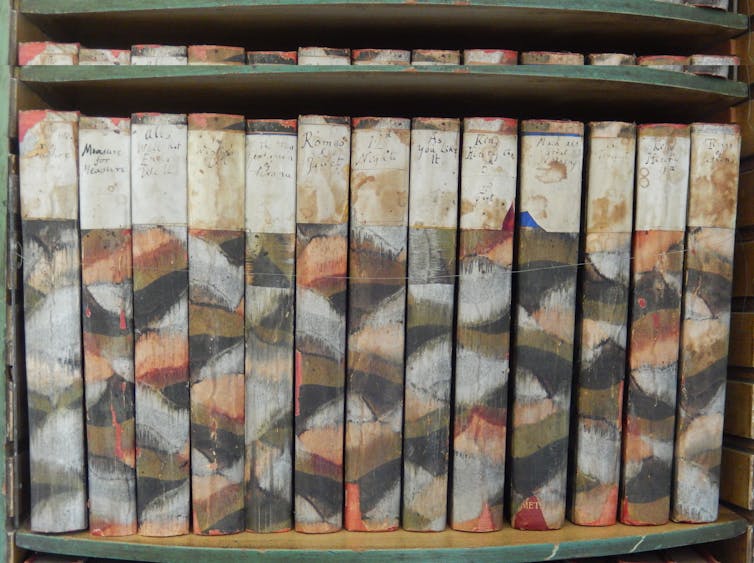

How to read Shakespeare for pleasure

In recent years the orthodoxy that Shakespeare can only be truly appreciated on stage has become widespread. But, as with many of our habits and assumptions, lockdown gives us a chance to think differently. Now could be the time to dust off the old collected works, and read some Shakespeare, just as people have been doing for more than 400 years.

Many people have said they find reading Shakespeare a bit daunting, so here are five tips for how to make it simpler and more pleasurable.

1. Ignore The Footnotes

If your edition has footnotes, pay no attention to them. They distract you from your reading and de-skill you, so that you begin to check everything even when you actually know what it means.

It’s useful to remember that nobody ever understood all this stuff – have a look at Macbeth’s knotty “If it were done when ‘tis done” speech in Act 1 Scene 7 for an example (and nobody ever spoke in these long, fancy speeches either – Macbeth’s speech is again a case in point). Footnotes are just the editor’s attempt to deny this.

Try to keep going and get the gist – and remember, when Shakespeare uses very long or esoteric words, or highly involved sentences, it’s often a deliberate sign that the character is trying to deceive himself or others (the psychotic jealousy of Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, for instance, expresses itself in unusual vocabulary and contorted syntax).

2. Pay Attention To The Shape Of The Lines

The layout of speeches on the page is like a kind of musical notation or choreography. Long speeches slow things down – and, if all the speeches end at the end of a complete line, that gives proceedings a stately, hierarchical feel – as if the characters are all giving speeches rather than interacting.

Short speeches quicken the pace and enmesh characters in relationships, particularly when they start to share lines (you can see this when one line is indented so it completes the half line above), a sign of real intimacy in Shakespeare’s soundscape.

Blank verse, the unrhymed ten-beat iambic pentamenter structure of the Shakespearean line, varies across his career. Early plays – the histories and comedies – tend to end each line with a piece of punctuation, so that the shape of the verse is audible. John of Gaunt’s famous speech from Richard II is a good example.

This royal throne of kings, this sceptered isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars.

Later plays – the tragedies and the romances – tend towards a more flexible form of blank verse, with the sense of the phrase often running over the line break. What tends to be significant is contrast, between and within the speech rhythms of scenes or characters (have a look at Henry IV Part 1 and you’ll see what I mean).

3. Read Small Sections

Shakespeare’s plays aren’t novels and – let’s face it – we’re not usually in much doubt about how things will work out. Reading for the plot, or reading from start to finish, isn’t necessarily the way to get the most out of the experience. Theatre performances are linear and in real time, but reading allows you the freedom to pace yourself, to flick back and forwards, to give some passages more attention and some less.

Shakespeare’s first readers probably did exactly this, zeroing in on the bits they liked best, or reading selectively for the passages that caught their eye or that they remembered from performance, and we should do the same. Look up where a famous quotation comes: “All the world’s a stage”, “To be or not to be”, “I was adored once too” – and read either side of that. Read the ending, look at one long speech or at a piece of dialogue – cherry pick.

One great liberation of reading Shakespeare for fun is just that: skip the bits that don’t work, or move on to another play. Nobody is going to set you an exam.

4. Think Like A Director

On the other hand, thinking about how these plays might work on stage can be engaging and creative for some readers. Shakespeare’s plays tended to have minimal stage directions, so most indications of action in modern editions of the plays have been added in by editors.

Most directors begin work on the play by throwing all these instructions away and working them out afresh by asking questions about what’s happening and why. Stage directions – whether original or editorial – are rarely descriptive, so adding in your chosen adverbs or adjectives to flesh out what’s happening on your paper stage can help clarify your interpretations of character and action.

One good tip is to try to remember characters who are not speaking. What’s happening on the faces of the other characters while Katherine delivers her long, controversial speech of apparent wifely subjugation at the end of The Taming of the Shrew?

5. Don’t Worry

The biggest obstacle to enjoying Shakespeare is that niggling sense that understanding the works is a kind of literary IQ test. But understanding Shakespeare means accepting his open-endedness and ambiguity. It’s not that there’s a right meaning hidden away as a reward for intelligence or tenacity – these plays prompt questions rather than supplying answers.

Would Macbeth have killed the king without the witches’ prophecy? Exactly – that’s the question the play wants us to debate, and it gives us evidence to argue on both sides. Was it right for the conspirators to assassinate Julius Caesar? Good question, the play says: I’ve been wondering that myself.

Returning to Shakespeare outside the dutiful contexts of the classroom and the theatre can liberate something you might not immediately associate with his works: pleasure.![]()

Emma Smith, Professor of Shakespeare Studies, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Estuaries Are Warming At Twice The Rate Of Oceans And Atmosphere

"Estuaries provide services of immense ecological and economic value. The rates of change observed in this study may also jeopardise the viability of coastal vegetation such as mangroves and saltmarsh in the coming decades and reduce their capacity to mitigate storm damage and sea-level rise."

Origins Of Human Language Pathway In The Brain At Least 25 Million Years Old

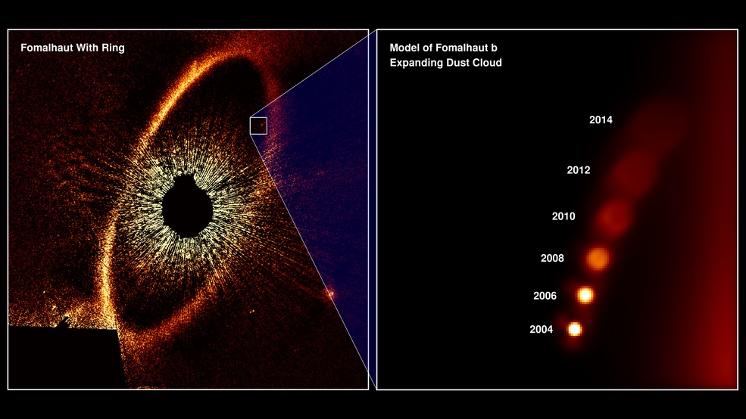

Exoplanet Apparently Disappears In Latest Hubble Observations

First Look Under Central Station

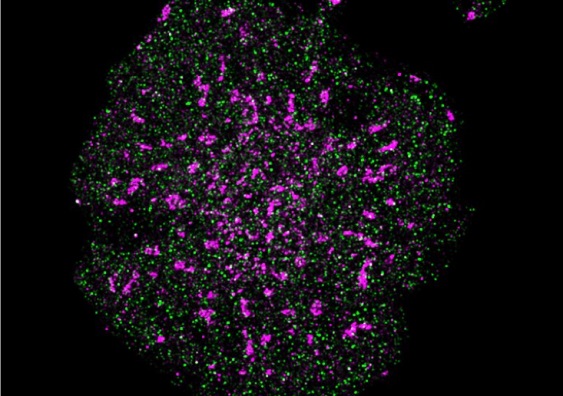

Self-Aligning Microscope Smashes Limits Of Super-Resolution Microscopy

Australia As A Renewable Energy Exporting Powerhouse

Disclaimer: These articles are not intended to provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Pittwater Online News or its staff.