Inbox and Environment News: Issue 454

June 14 - 20, 2020: Issue 454

Household Chemical CleanOuts Back

Mona Vale Beach Car Park, Surfview Road, Mona Vale

Sat 20, Sun 21 June 2020: 9am - 3:30pm

Household Chemical CleanOut events are returning to your neighbourhood after a break because of COVID-19.

The free service, run jointly by the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment and local councils, provides a safe way to dispose of potentially hazardous household items such as paint, oils and cleaning products.

The return of these events is a welcome addition to the calendar for the NSW community, with many people using their recent spare time to de-clutter the house and garage. Any problem wastes discovered while de-cluttering can now be disposed of for free at a Household Chemical CleanOut.

You can take household quantities of many chemicals and items – up to a maximum of 20 litres or 20 kilograms of a single item – to a CleanOut event, including:

- Car and household batteries

- Fire extinguishers

- Gas bottles

- Smoke detectors

- Acids and alkalis

- Pesticides and herbicides

- Paint

- Batteries

- Oils

- Pool chemicals

- Fluorescent globes and tubes, and more

The events re-start this Saturday 30 May at Glendale TAFE, followed by Meadowbank, Nowra, Mona Vale, Rutherford, Leumeah, Katoomba and Heffron Park, Matraville in coming weeks.

See the EPA website for information about individual events, for dates, times and other details including locations, with more events being added regularly.

Due to COVID-19 there are new protocols that participants need to be aware of:

Before you attend a Chemical CleanOut event, please place all materials in the rear of your vehicle. On arrival, remain in your vehicle and our contractor will collect your items. Contractors onsite will be wearing personal protective equipment and following social distancing measures.

Lookout For A Better View Of Spectacular Wollomombi Falls

June 9, 2020

A new lookout with a better view of the highest waterfall in NSW, Wollomombi Falls, has just opened, ready to wow visitors to Oxley Wild Rivers National Park.

National Parks and Wildlife Service Area Manager Aaron Simmon said the new lookout 25 minutes from Armidale, provided better accessibility for vehicles and wheelchairs.

“It is bigger and better than any other view of the gorge system and just minutes off the Waterfall Way.

“When we say its open for everyone, we mean it, the new lookout has been well designed and positioned to allow better access for all, including independent wheelchairs.

“We have increased the carpark capacity to allow for coaches and those towing caravans.

“The new lookout ensures visitors have a better view of both Wollomombi and Chandler Falls.

“Wollomombi Falls is the highest waterfall in New South Wales, with the water plummeting 260 metres into the Chandler River.

“NPWS partnered with local Aboriginal company JNC Group, who have a strong local connection, to construct the magnificent new lookout using local services and suppliers.

“The redevelopment was funded under the NSW Government’s Improving Access to National Parks program.

“The lookout opening comes as we welcome visitors back to our campgrounds, with a new online booking system in place.

“Extra COVID 19 provisions mean pre-booking is now essential for all campsites in NSW national parks via the website or by calling 1300 072757.

“As an added bonus the Wollomombi Falls are thumping again following recent rainfall.

“Book a campsite, or pack a picnic and enjoy one of the spectacles of the New England Area,” Mr Simmon said.

A new lookout with a better view of the highest waterfall in NSW, Wollomombi Falls Photo: Leah Pippos/DPIE

Weeping Paperbark Brings Hope To Richmond Valley

June 10, 2020

Endangered weeping paperbark trees in the Richmond Valley’s Bungawalbin National Park are continuing to show early recovery signs following the bushfires, NPWS North Coast Branch Acting Director Janelle Brooks said.

“This is good news following the fires. Fresh regrowth is lifting the spirits of staff assessing our parks, and they’re encouraged to see these weeping paperbarks starting to bounce back,” Ms Brooks said.

“New leaves are shooting from these trees’ bases, trunks and some branches. With 97 per cent of Bungawalbin National Park affected by fire, it is heartening to see nature reviving.”

While early monitoring of the weeping paperbark – or Melaleuca irbyana – shows leaves re-sprouting, it is too soon to know the extent of the recovery of the population.

The Saving our Species (SoS) team will monitor the site for up to two years, providing input to the NSW Flora Fire Response Database.

“Findings will feed into managing other weeping paperbark populations, as well as improving the workings of future revegetation projects,” SoS Project Officer Anna Lloyd said.

In NSW the weeping paperbark is isolated to two major coastal floodplains in north-eastern NSW, while a third population is in south-east Queensland.

“Monitoring these plants during post-fire recovery helps staff to understand how fire affects the survival and expansion of weeping paperbark populations,” Ms Lloyd said.

Already, monitoring shows these trees can withstand fires of low-to-moderate intensity, and staff are now looking to see if seedlings will follow. All data will also feed into a better understanding of fire regimes, which will help support decisions around hazard reduction burning.

Inspection of recovery of weeping paperbark (Melaleuca irbyana), Bungawalbin National Park Photo: Anna Lloyd/DPIE

NSW Government’s Support For Santos Narrabri CSG Project A Betrayal Farmers State

June 12, 2020

North west NSW farmers have today slammed the Planning Department’s decision to label the destructive and polluting Santos Narrabri coal seam gas “approvable”.

The decision was made despite the government’s failure to implement the Chief Scientist’s recommendations for managing risks from the industry and shock revelations this week that landholders affected by the gas industry may not be insured for public liability.

The decision is particularly galling because the amount of contaminated salt waste to be dumped at a location that is still unknown as a result of the project appears to have roughly doubled to 840,000 tonnes.

The department’s documents released as part of the recommendation also show about 1,000 hectares of koala habitat may be destroyed for the project.

As well, questions remain over potential contamination of underground water via unknown geological faults, with water experts unable to come to a conclusion concerning the risk.

Narrabri farmer Stuart Murray said, “This toxic project should never have reached the Independent Planning Commission simply because the NSW Chief Scientist Mary O’Kane made 16 recommendations to mitigate the risk of CSG, the government took it on board, made it policy, but has still not implemented it after almost six years.

“Our government has betrayed us.

“We don’t know where that contaminated salt waste is going to go, there is no solution. I am deeply concerned it could end up in our river systems and in our underground water systems.”

North west NSW stock and station agent and beef producer David Chadwick said, “The Liberal National Coalition has been applying immense pressure to have this project up and running against fierce opposition from the local area and broader region.

“The recent defeat of the CSG Moratorium Bill absolutely highlights how the Liberal National Coalition has betrayed rural Australia. That is why the seat of Barwon was lost after 60 years to Roy Butler of the Shooters, Fishers, and Farmers Party who went to the last election and stood true to his word, unlike the Nationals.

“It is inconceivable after the last three years of record drought and climate change being at the forefront of everyone’s minds that our government would even contemplate supporting, let alone approving, a project that puts our only secure water supply at risk.

“Santos’ history of fines and breaches at the exploration phase guarantees this will end in disaster.”

Lock the Gate NSW spokesperson Georgina Woods said “This entire process has been highly politicised and the people of New South Wales will bear the cost.

"Political slogans about gas prices are contradicted by the department’s own Assessment Report which admits that if gas prices fall by 30 per cent, the project’s economic profile would be a net negative.”

“It is the people of north west NSW that will be hurt most by this. A NSW parliamentary inquiry earlier this year described coal seam gas as “uninsurable” and it has been revealed this week that the largest insurance company in Australia is refusing to offer public liability cover to farmers who have CSG infrastructure on their properties in Queensland.

“We’re appealing to the IPC to ignore the political pressure and demonstrate its independence by refusing approval for this polluting project and safeguarding the people, water, and future of the state’s north west.”

The Planning Department’s recommendation is here.

More than 1,200 tonnes of microplastics are dumped into Aussie farmland every year from wastewater sludge

Every year, treated wastewater sludge called “biosolids” is recycled and spread over agricultural land. My recent research discovered this practice dumps thousands of tonnes of microplastics into farmlands around the world. In Australia, we estimate this amount as at least 1,241 tonnes per year.

Microplastics in soils can threaten land, freshwater and marine ecosystems by changing what they eat and their habitats. This causes some organisms to lose weight and have higher death rates.

But this is only the beginning of the problem. Microplastics are good at absorbing other pollutants – such as cadmium, lead and nickel – and can transfer these heavy metals to soils.

And while microplastics alone is an enormous issue, other contaminants have also been found in biosolids used for agriculture. This includes pharmaceutical chemicals, personal care products, pesticides and herbicides, surfactants (chemicals used in detergents) and flame retardants.

We must stop using biosolids for farmlands immediately, especially when alternative ways to recycle wastewater sludge already exist.

Where Do The Microplastics Come From?

Biosolids are mainly a mix of water and organic materials.

But many household items that contain microplastics – such as lotions, soaps, facial and body washes, and toothpaste – end up in wastewater, too. Other major sources of microplastics in wastewater are synthetic fibres from clothing, plastics in the manufacturing and processing industries, and the breakdown of larger plastic debris.

Before they’re taken to farmlands, wastewater collection systems carry all, or most, of these microplastics and other chemicals from residential, commercial and industrial sources to wastewater treatment plants.

To determine the weight of microplastics in Australia and other countries, my data analysis used the average minimum and maximum numbers of microplastics particles, per kilogram of biosolids samples, found in Germany, Ireland and the USA.

Read more: We have no idea how much microplastic is in Australia's soil (but it could be a lot)

Australia produced 371,000 tonnes of biosolids in 2019. And globally, we estimate between 50 to more than 100 million tonnes of biosolids are produced each year.

Why Microplastics Are Harmful

Microplastics in soil can accumulate in the food web. This happens when organisms consume more microplastics than they lose. This means heavy metals attached to the microplastics in soil organisms can progress further up the food chain, increasing the risk of human exposure to toxic heavy metals.

When microplastics accumulate heavy metals, they transfer these contaminants to plants and crops, such as rice and grains, as biosolids are spread over farmland.

Read more: After a storm, microplastics in Sydney's Cooks River increased 40 fold

Over time, microplastics break down and become even tinier, creating nanoplastics. Crops have also been shown to absorb nanoplastics and move them to different plant tissues.

Our research results also show that after the wastewater treatment process, the absorption potential of microplastics for metals increases.

The metal cadmium, for example, is particularly susceptible to microplastics in biosolids and can be transported to plant cells. Research from 2018 showed microplastics in biosolids can absorb cadmium ten times more than virgin microplastics (new microplastics that haven’t gone through wastewater treatment).

Biosolids Have A Cocktail Of Nasty Chemicals

It’s not just plastic – many industrial additives and chemicals have been found in wastewater and biosolids.

This means they may accumulate in soils and affect the equilibrium of biological systems, with negative effects on plant growth. For example, researchers have found pharmaceutical chemicals in particular can reduce plant growth and inhibit root elongation.

Read more: Sustainable shopping: how to stop your bathers flooding the oceans with plastic

Other chemical contaminants – such as PFCs, PFAS and BPA – have likewise been detected in biosolids.

The effects these chemicals have on plants may lead to problems further down the food chain, such as humans and other animals inadvertently consuming pharmaceuticals and harmful chemicals.

What Can We Do About It?

Given the cocktail of toxic chemicals, heavy metals and microplastics, using biosolids in agricultural soils must be stopped without delay.

The good news is there’s another way we can recycle the world’s biosolids: turning them into sustainable fired-clay bricks, called “bio-bricks”.

My team’s research from last year found bio-bricks a sustainable solution for both the wastewater treatment and brick manufacturing industries.

If 7% of all fired-clay bricks were biosolids, it would redirect all biosolids produced and stockpiled worldwide annually, including the millions of tonnes that currently end up in farmland each year.

Read more: You're eating microplastics in ways you don't even realise

We also found they’d be more energy efficient. The properties of these bio-bricks are very similar to standard bricks, but generally requires 12.5% less energy to make.

And generally, comprehensive life-cycle assessment has shown biosolid bricks are more environmentally friendly than conventional bricks. These bricks will reduce or eliminate a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions from biosolids stockpiles and will save some virgin resources, such as clay soil and water, for the brick industry.

Now, it’s up to the agriculture, wastewater and brick industries, and governments to make this important transition.![]()

Abbas Mohajerani, Associate Professor, School of Engineering, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The coastal banksia has its roots in ancient Gondwana

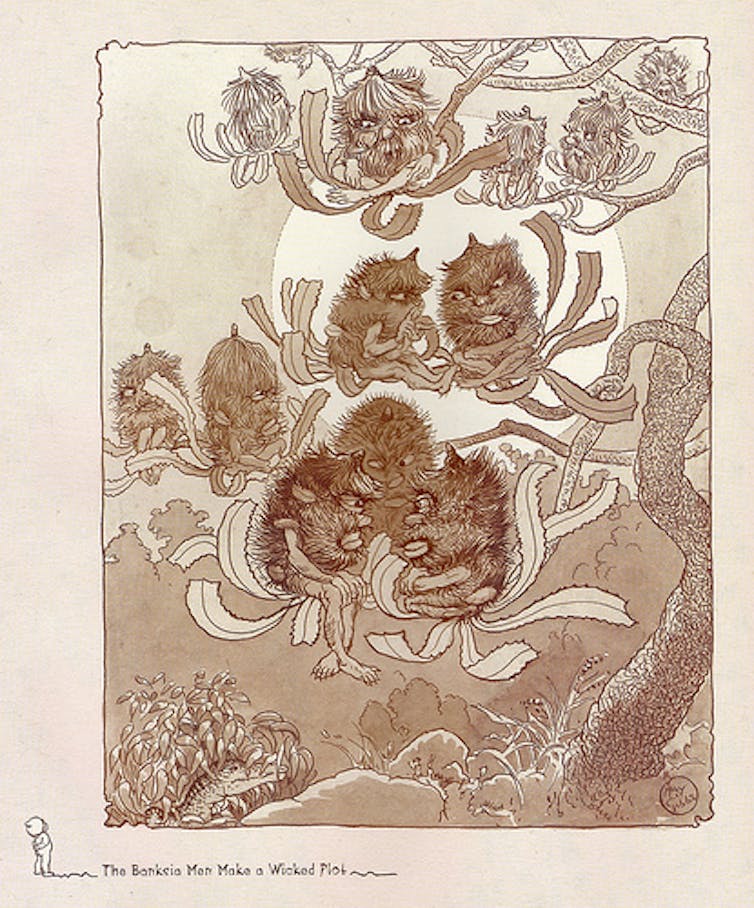

If you fondly remember May Gibbs’s Gumnut Baby stories about the adventures of Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, you may also remember the villainous Big Bad Banksia Men (perhaps you’re still having nightmares about them).

But banksias are nothing to be afraid of. They’re a marvellous group of Australian native trees and shrubs, with an ancient heritage and a vital role in Australian plant ecology, colonial history and bushfire regeneration.

The genus Banksia has about 173 native species. It takes its name from botanist Sir Joseph Banks, who collected specimens of four species in 1770 when he arrived in Australia on board Captain Cook’s Endeavour.

Read more: Botany and the colonisation of Australia in 1770

One of the four species he collected was B. integrifolia, the coastal banksia. This can be a small to medium tree about 5m to 15m tall. In the right conditions, it can be quite impressive and grow up to 35m.

It’s found naturally in coastal regions, growing on sand dunes or around coastal marshes from Queensland to Victoria. These can be quite tough environments and, while B. integrifolia tends to grow in slightly protected sites, it still copes well with sandy soils, poor soil nutrition, salt and wind.

From Ancient Origins

Coastal banksia – like all banksias – belong to the protea family (Proteaceae). But given the spectacular flowering proteas are of African origin, how did our Australian genera get here?

The members of the Proteaceae belong to an ancient group of flowering plants that evolved almost 100 million years ago on the southern supercontinent Gondwana. When Gondwana fragmented more than 80 million years ago, the proteas remained on the African plate, while the Australian genera remained here.

Read more: The firewood banksia is bursting with beauty

The spikes of woody fruits on the Australian banksia, sometimes called cones, are made up of several hundred flowers. The flower spikes are beautiful structures, soft and brush-like. But with B. integrifolia, they are pale green, similar to the foliage, and can be hard to see within the canopy at a distance.

Up close, these fruit spikes can look quite spooky, almost sinister, especially when wasps have caused extensive gall formation. Galls are swellings that develop on plant tissues as a result of fungal and insect damage, a bit like a benign tumour.

Maybe this is what led May Gibbs to cast them as the baddies in her Gumnut Baby stories. While the galls may look unsightly, they rarely do serious harm to banksias.

Indigenous Use

Given the fruit spikes of coastal banksia look like brushes, it’s not surprising Indigenous people once used them as paint brushes.

The flowers are very rich in nectar, which attracts insects and birds. If you run your hand along the flower spike you, like generations of Aboriginal people before you, can enjoy the sweet taste if you lick the nectar off your hand. You can also soak the flowers in water and collect a sweet syrup.

In the garden, B. integrifolia is wonderfully attractive to native insects, birds and ringtail possums. It’s easy to establish and, until it grows more than a few metres high, can be successfully moved and transplanted.

Unlike many other banksia species, coastal banksias don’t need fire to release their seed. For many Australian species, the woody fruits remain solid and sealed, and it’s only when fire comes through that they burn, dry, crack open and release their seed.

This can happen with B. integrifolia too, but in a garden setting the fruits will mature, dry and crack open and release the seeds, which germinate readily. This makes propagating coastal banksia easy work.

In Touch With Its Roots

Perhaps one of the more important, but less obvious, attributes of B. integrifolia are its roots. These are a special type of root possessed by members of the protea family.

The roots form a dense, branched cluster, a bit like the head of a toothbrush, that can be 2-5cm across. They greatly increase the absorbing surface area of the roots, as each root possesses thousands of very fine root hairs.

Read more: The black wattle is a boon for Australians (and a pest everywhere else)

Proteoid roots can be very handy in sandy and other poor soils, where water drains quickly and nutrients are scarce.

These roots, also described as cluster roots, are often visible in a garden bed just at the interface of the soil with the humus or mulch layer above it. They’re very light brown, almost white, in colour.

B. integrifolia, like other banksias, also has the ability to take in nitrogen and enrich the soil, which can be very handy in soils low in nitrogen. It’s like a natural living and decorative fertiliser.

Read more: After the bushfires, we helped choose the animals and plants in most need. Here's how we did it

Proteoid roots are unfortunately very well suited to the presence of Phytophthora cinnamomii (the cinnamon fungus). It causes dieback in many native plant species, but can be particularly virulent for banksias.

But B. Integrifolia is one of the more resistant species to the fungus. Promising experiments have been done on grafting susceptible species onto the roots of B. integrifolia to improve their rates of survival.

This could be important, as banksias have a role in bushfire regeneration in many parts of Australia, so the occurrence of the fungus can compromise fire recovery.![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Please Help Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Donate Your Cans And Bottles And Nominate SW As Recipient

You can Help Sydney Wildlife help Wildlife. Sydney Wildlife Rescue is now listed as a charity partner on the return and earn machines in these locations:

- Pittwater RSL Mona Vale

- Northern Beaches Indoor Sports Centre NBISC Warriewood

- Woolworths Balgowlah

- Belrose Super centre

- Coles Manly Vale

- Westfield Warringah Mall

- Strathfield Council Carpark

- Paddy's Markets Flemington Homebush West

- Woolworths Homebush West

- Bondi Campbell pde behind Beach Pavilion

- Westfield Bondi Junction car park level 2 eastern end Woolworths side under ramp

- UNSW Kensington

- Enviro Pak McEvoy street Alexandria.

Every bottle, can, or eligible container that is returned could be 10c donated to Sydney Wildlife.

Every item returned will make a difference by removing these items from landfill and raising funds for our 100% volunteer wildlife carers. All funds raised go to support wildlife.

It is easy to DONATE, just feed the items into the machine select DONATE and choose Sydney Wildlife Rescue. The SW initiative runs until August 23rd.

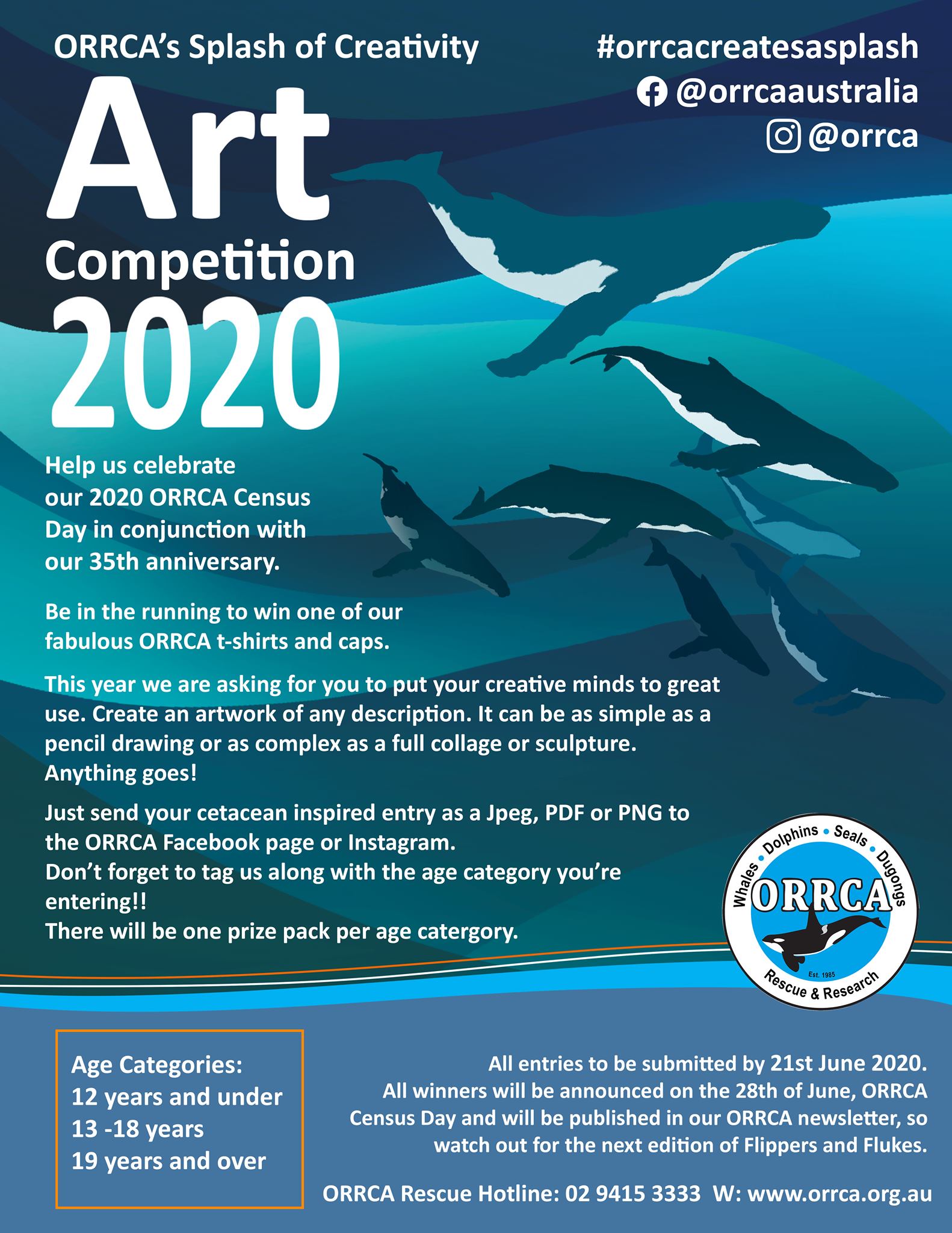

ORRCA Art Comp. 2020 And ORRCA Census Day 2020

ORRCA stands for the Organisation for the Rescue and Research of Cetaceans in Australia. Put simply, our primary focus is the rescue, preservation, conservation and welfare of Whales, Dolphins, Seals and Dugongs in Australian waters.

ORRCA operates a 24/7 Rescue Hotline for the public to report any injured or stranded whales, dolphins, seals and dugongs. Simply call 02 9415 3333.

We are the only volunteer wildlife rehabilitation group in New South Wales licensed to be involved with marine mammal rescue, rehabilitation and release. Our members come from all walks of life, age groups and nationalities.

ORRCA offers the community one of the most experienced and successful whale, dolphin, seal and dugong rescue teams in Australia. We are also proud that today, we have rescue trained teams in Western Australia and Queensland available to support local authorities should a marine mammal incident arise.

All members within ORRCA are volunteers

We operate as a non-profit organisation and have charity status.

It is because of the generosity of the public providing donations, and the love and passion of people wanting to get involved and learn about these amazing animals, that ORRCA exists on its own two flippers today.

Through our ever growing membership base of valued and dedicated volunteers and our highly commended rescue training workshops coupled with the strength and dedication of the Committee, ORRCA has achieved extraordinary things over the past 34 years.

ORRCA operates a 24/7 Rescue Hotline for the public to report any injured or stranded whales, dolphins, seals and dugongs. Simply call 02 9415 3333.

Visit: http://www.orrca.org.au/

Rat Poisons Are Killing Our Wildlife: Alternatives

BirdLife Australia is currently running a campaign highlighting the devastation being caused by poison to our wildlife. Rodentcides are an acknowledged but under-researched source of threat to many Aussie birds. If you missed BirdLife's rodenticide talk but would like to know more, share data and comment on the use of rodenticides in Australia please visit: https://www.actforbirds.org/ratpoison

Owls, kites and other birds of prey are dying from eating rats and mice that have ingested Second Generation rodent poisons. These household products – including Talon, Fast Action RatSak and The Big Cheese Fast Action brand rat and mice bait – have been banned from general public sale in the US, Canada and EU, but are available from supermarkets throughout Australia.

Australia is reviewing the use of these dangerous chemicals right now and you can make a submission to help get them off supermarket shelves and make sure only licenced operators can use them.

There are alternatives for household rodent control – find out more about the impacts of rat poison on our birds of prey and what you can do at the link above and by reading the information below.

Let’s get rat poison out of bird food chains.

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) – is currently asking Australians for their views on how rodent poisons are regulated.

Have your say by making a submission here.

Powerful Owl at Clareville - photo by Paul Wheeler

Pesticides that are designed to control pests such as mice and rats cane also kill our wildlife through either primary or secondary poisoning. Insecticides include pesticides (substances used to kill insects), rodenticides (substances used to kill rodents, such as rat poison), molluscicides (substances used to kill molluscs, such as snail baits), and herbicides (substances used to kill weeds).

Primary poisoning occurs when an animal ingests a pesticide directly – for example, a brushtail possum or antechinus eating rat bait. Secondary poisoning occurs when an animal eats another animal that has itself ingested a pesticide – for example, a greater sooty owl eating a rate that has been poisoned or an antechinus that had eaten rat bait.

Rodenticides are the most common and harmful pesticides to Australian wildlife. Though no comprehensive monitoring of non-target exposure of rodenticides has been conducted, numerous studies have documented the harm rodenticides do to native animals. In 2018, an Australian study found that anticoagulant rodenticides in particular are implicated in non-target wildlife poisoning in Australia, and warned Australia’s usage patterns and lax regulations “may increase the risk of non-target poisoning”.

Most rodenticides work by disrupting the normal coagulation (blood clotting) process, and are classified as either “first generation” / “multiple dose” or “second generation” / “single dose”, depending on how many doses are required for the poison to be lethal.

These anticoagulant rodenticides cause victims of anticoagulant rodenticides to suffer greatly before dying, as they work by inhibiting Vitamin K in the body, therefore disrupting the normal coagulation process. This results in poisoned animals suffering from uncontrolled bleeding or haemorrhaging, either spontaneously or from cuts or scratches. In the case of internally haemorrhaging, which is difficult to spot, the only sign of poisoning is that the animal is weak, or (occasionally) bleeding from the nose or mouth. Affected wildlife are also more likely to crash into structures and vehicles, and be killed by predators.

An animal has to eat a first generation rodenticide (e.g. warfarin, pindone, chlorophaninone, diphacinone) more than once in order to obtain a lethal dose. For this reason, second generation rodenticides (e.g. difenacoum, brodifacoum, bromadiolone and difethialone) are the most commonly used rodenticides. Second generation rodenticides only require a single dose to be consumed in order to be lethal, yet kill the animal slowly, meaning the animal keeps coming back. This results in the animal consuming many times more poison than a single lethal dose over the multiple days it takes them to die, during which time they are easy but lethal prey to predators. This is why second generation poisons tend to be much more acutely toxic to non-target wildlife, as they are much more likely to bioaccumulate and biomagnify, and clear very slowly from the body.

Species most at risk from poisons

Small Mammals

Small mammals including possums and bandicoots often consume poisons such as snail bait, or rat bait that has been laid out to attract and kill rats, mice, and rabbits. Poisons such as pindone are often added to oats or carrots, and lead to a slow, painful death of internal bleeding. Australian possums often consume rat bait such as warfarin, which causes extensive internal bleeding, usually resulting in death.

There is a very poor chance of survival. Possums are also known to consume slug bait, which results in a prolonged painful death mainly from neurological effects. There is no treatment.

Small mammals can also be poisoned by insecticides. Possums, for example, can ingest these poisons when consuming fruit from a tree that has been sprayed with insecticide. Rescued by a WIRES carer, the brushtail possum joey pictured below was suffering from suspected insecticide poisoning. Though coughing up blood, luckily the joey did not ingest a lethal dose as he survived in care and was later released.

Large Mammals

Despite their size, large mammals including wallabies, kangaroos and wombats can also fall victim to pesticide poisoning. Wallabies and kangaroos have been known to suffer from rodenticide poisoning, while poisons often ingested by wombats include rat bait from farm sheds, and sodium fluroacetate (1080) laid out to kill pests such as cats and foxes.

Australian mammals are also impacted by the use of insecticides. DDT, although a banned substance, has been reported as killing marsupials.

Birds

Birds have a high metabolic rate and therefore succumb quickly to poisons. Australian birds of prey – owls (such as the southern boobook) and diurnal raptors (such as kestrels) – can be killed by internal bleeding when they eat rodents that have ingested rat bait. A 2018 Western Australian study determined that 73% of southern boobook owls found dead or were found to have anticoagulant rodenticides in their systems, and that raptors with larger home ranges and more mammal-based diets may be at a greater risk of anticoagulant rodenticide exposure.

Insectivorous birds will often eat insects sprayed with insecticides, and a few different species of birds may be affected at the same time. Unfortunately little can be done and death most often results.

Organophosphates are the most widely used insecticide in Australia. Birds are very susceptible to organophosphates, which are nerve toxins that damage the nervous system, with poisoning occurring through the skin, inhalation, and ingestion. Organophosphates can cause secondary poisoning in wild birds which ingest sprayed insects. Often various species of insectivorous birds are affected at the same time as they come down to eat the dying insects. After a bird is poisoned, death usually occurs rapidly. Raptors have also been deliberately or inadvertently poisoned when organophosphates have been applied to a carcass to poison crows.

Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) are persistent, bio-accumulative pesticides that include DDT, dieldrin, heptachlor and chlordane. OPC’s have been used extensively in the agriculture industry since the 1940s. Some of the more common product names include Hortico Dieldrin Dust, Shell Dieldrex and Yates Garden Dust. Although no OCP’s are currently registered for use in the home environment in Australia, many of these products still remain in use on farms, in business premises and households. OCP poisons remain highly toxic in the environment for many years impacting on humans, animals, birds and especially aquatic life. They can have serious short-term and long-term impacts at low concentrations. In addition, non-lethal effects such as immune system and reproductive damage of some of these pesticides may also be significant. Birds are particularly sensitive to these pesticides, and there have even been occasions where the deliberate poisoning of birds has occurred. Tawny frogmouths are most often poisoned with OCP’s. The poisons are stored in fat deposits and gradually increase over time. At times of food scarcity, or during any stressful period, such as breeding season or any changes to their environment, the fat stores are metabolised, and with it, the poison load in their blood streams reaches acute levels, causing death.

Although herbicides, or weed killers, are designed to kill plants, some are toxic to birds. Common herbicide glyphosate (Roundup) will cause severe eye irritation in birds if they come into contact with the spray. Herbicides also have the impact of removing food plants that birds, or their insect food supply, rely on. Birds can also readily fall victim to snail baits, either via primary or secondary poisoning.

Reptiles and Amphibians

As vertebrate species, reptiles and amphibians are also at risk of pesticides. Though less is known about the effects of pesticides on reptiles and amphibians, these animals have been known to fall victim to pesticide poisoning. Blue-tongue lizards, for example, often consume rat bait and die of internal bleeding. A 2018 Australian study also found that reptiles may be important vectors (transporters) of rodenticides in Australia.

How to keep pests away and keep wildlife safe

Remember, pesticides are formulated to be tasty and alluring to the target species, but other species find them enticing, too. It is safest for wildlife, pets and people for us to not use any pesticides, and prevent or deter the presence of pests practically, rather than attempt to eliminate them chemically.

Tips to prevent and deter wildlife deaths from poisoning:

- Deter rats and mice around your property by simply cleaning up; removing rubbish, keeping animal feed well contained and indoors, picking up fallen fruits and vegetation, and using chicken feeders removes potential food sources.

- Seal up holes and in your walls and roof to reduce the amount of rodent-friendly habitat in your house.

- Replace palms with native trees; palm trees are a favourite hideout for black rats, while native trees provide ideal habitat for native predators like owls and hawks which help to control rodent populations.

- Set traps with care in a safe, covered spot, away from the reach of children, pets and wildlife. Two of the most effective yet safe baits are peanut butter and pumpkin seeds.

- To control slugs, terracotta or ceramic plant pots can be placed upside down in the garden or aviary. Slugs and snails will seek the dark, damp area this creates, and can be collected daily. They can then be drowned in a jar of soapy water. You can also sink a jar or dish into the soil and fill it with beer. The slugs are attracted to the yeast in the beer, fall in and then drown.

If turning to pesticides as a last resort:

- Use only animal-safe slug baits.

- Place tamper-proof bait stations out of reach of wildlife.

- Avoid using loose whether pellets or poison grain, present the highest risk, the latter being particularly attractive to seed-eating birds and to many small mammal species.

- Read the label and use as instructed.

- Avoid products containing second generation products difenacoum, brodifacoum, bromadiolone and difethialone, which are long-lasting and much more likely to unintentionally poison wildlife via secondary poisoning.

- Cover individual fruits when spraying fruit trees with insecticides.

Poisons kill dogs too

Because of their poisonous nature, pesticides pose a risk to animals and people alike, including pets and children. Roaming pets like cats and dogs are most at risk of being poisoned, with one 2016 study at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences finding that one in five dogs had rat poison in its body, and a 2011 study by the Humane Society in the United States finding that 74% of their pet poisoning cases are due to second-generation anticoagulants such as rat baits.

It is best to avoid the use of all pesticides, or otherwise use them sparingly, carefully and only after researching each poison and its correct usage. Always supervise pets and children, keep poisons locked out of their reach, and be vigilant in public spaces where pesticides may have accumulated, e.g. poisons can accumulate in streams or puddles where herbicides have recently been sprayed.

If you suspect your pet has been poisoned, seek veterinary help immediately.

If you suspect your child or another adult has been poisoned, do not induce vomiting and call the NSW Poisons Information Centre on 13 11 26 for 24/7 medical advice, Australia-wide.

References

Lohr, M. T. & Davis, R. A. 2018, Anticoagulant rodenticide use, non-target impacts and regulation: A case study from Australia, Science of The Total Environment, vol. 634, pp. 1372-1384.

Lohr, M. T. 2018, Anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in an Australian predatory bird increases with proximity to developed habitat, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 643, pp.134-144.

Lohr, M. T. 2018, Anticoagulant Rodenticides: Implications for Wildlife Rehabilitation, conference paper, Australian Wildlife Rehabiliation Conference, awrc.org.au

Olerud, S., Pedersen, J. & Kull, E. P. 2009, Prevalence of superwarfarins in dogs – a survey of background levels in liver samples of autopsied dogs. Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Life Sciences, Department of Sports and Family Animal Medicine, Section for Small Animal Diseases.

Healthy Wildlife, Healthy Lives, 2017, Rodenticides and Wildlife, healthywildlife.com.au

Society for the Preservation of Raptors Inc. 2019, Raptor Fact Sheet: Eliminate Rats and Mice, Not Wildlife!, raptor.org.au/factsheetpests.pdf

W.I.R.E.S. Poisons and baits don't just kill rats.

.jpg?timestamp=1590728675788)

Barking Owl (Ninox connivens connivens)- photo by Julie Edgley - this nocturnal animal will eat mice and so become a victim of poisons through them

Echidna Season

Echidna season has begun. As cooler days approach, our beautiful echidnas are more active during the days as they come out to forage for food and find a mate. This sadly results in a HIGH number of vehicle hits.

What to do if you find an Echidna on the road?

- Safely remove the Echidna off the road (providing its safe to do so).

- Call Sydney Wildlife or WIRES

- Search the surrounding area for a puggle (baby echidna). The impact from a vehicle incident can cause a puggle to roll long distances from mum, so please search for these babies, they can look like a pinky-grey clump of clay

What to do if you find an echidna in your yard?

- Leave the Echidna alone, remove the threat (usually a family pet) and let the Echidna move away in it's own time. It will move along when it doesn't feel threatened.

If you find an injured echidna or one in an undesirable location, please call Sydney Wildlife on 9413 4300 for advice.

www.sydneywildlife.org.au

Lynleigh Greig, Sydney Wildlife, with a rescued echidna being returned to its home

New Shorebird Identification Booklet

New Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

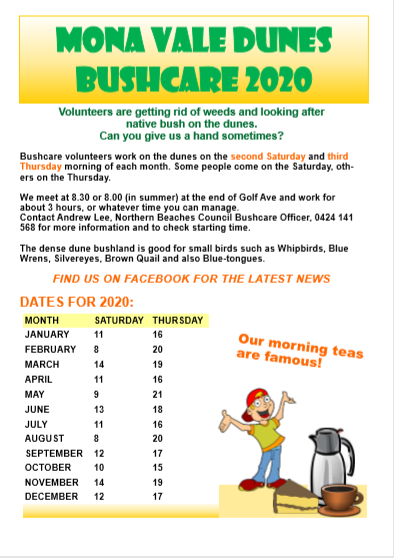

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Pittwater Reserves

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Who Says Eco-Warriors Have To Be Young?

In remembering Christo, we remember what art once was

In 1995, after the fall of the Wall, Berlin had started to be rebuilt, but was still in a state of disrepair.

There, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, two of the world’s most important land artists, wrapped the entire Reichstag, the seat of German parliament, in over 100,000 square meters of fabric.

The wrapping expressed more than words ever could about the complex and harrowing culture of guilt, forgetting and memorisation still inextricable from German identity.

It was a swaddling of old wounds. At the same time, it offered the new Germany gift-wrapped to what would soon be the European Union. And knowing of the beleaguered state of the EU, the work – in memory and reproduction – speaks to us still.

Born in Bulgaria in 1935, Christo Vladimirov Javacheff began his career as a painter. But it was in land art where he made his name, alongside wife and longtime collaborator Jeanne-Claude.

Emerging in the 1960s, land art saw artists preoccupied with bringing art outside of the house, gallery, or museum to bridge the gap between art and nature. Land art is, more often than not, heroic in size, operating on a scale of energy and logistics at which most artists would balk.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude were responsible for a number of massive works that remain burned into the memories of many in reality and in reproduction: works of effort and massive gesture. Other works had an audacity tinged with witty and poignant politicisation.

Jeanne-Claude died in 2009, and Christo continued working under the name of their partnership until his death this weekend in New York City at the age of 84.

The Starting Place Of A Legacy

Christo’s work has a particular significance for Australia: the very first wrapped work was staged in 1968-1969 at Little Bay in Sydney.

An enormous swathe of the landscape was covered in tonnes of plastic tarp, and wrapped to the coastline. It was something the Australian art community and public had never seen before or since, offering previously unseen sense of ambition and scale. It also inspired Australian artists to be more active abroad to try their own interventions there, albeit more modestly.

But too often conveniently forgotten about the work is it was devastating to the region’s wildlife and local ecosystem. Hundreds of birds who depended on the region for their sustenance and habitat died during the life of the project.

Ironically then, given the present predicament we are in, Wrapped Coast gives us more to think about than we might previously have anticipated. It is certainly a work that would not have been sanctioned today. We might remember it as an example of excesses of spectacle that have precipitated many worse consequences.

Read more: The heady sense of being at the heart of public art: 50 years of the Kaldor Foundation

This does not discredit the work – far from it. Rather, it is a work of talismanic importance standing now not only as an example of the possibilities of scale in art, but also as a corrective that may speak to our future actions and attitudes afresh much as it spoke to the generation of artists who were able to experience it in all its hubristic glory.

Bigger Than Man

Following from Sydney, Christo and Jeanne-Claude would become known around the world for their work. They wrapped walkways in Kansas City, islands in Miami’s Biscayne Bay, trees in Basel, piers in Brescia, Italy. Their work played on other scales, too: placing 7,503 fabric gates throughout New York’s Central Park, and hundreds of umbrellas placed simultaneously in Japan and California.

They encouraged the viewer to look on landscapes and buildings through new eyes. The absence of what was there causing the viewer to look deeper than they previously have. Their body of work is now firmly etched into 20th-century art.

It could be the nature and scale of their projects – given the logistics and art’s future due to the present – have receded faster into history than we had anticipated.

This may give us cause to mourn more than the man, but what art had once been.![]()

Adam Geczy, Senior Lecturer, Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

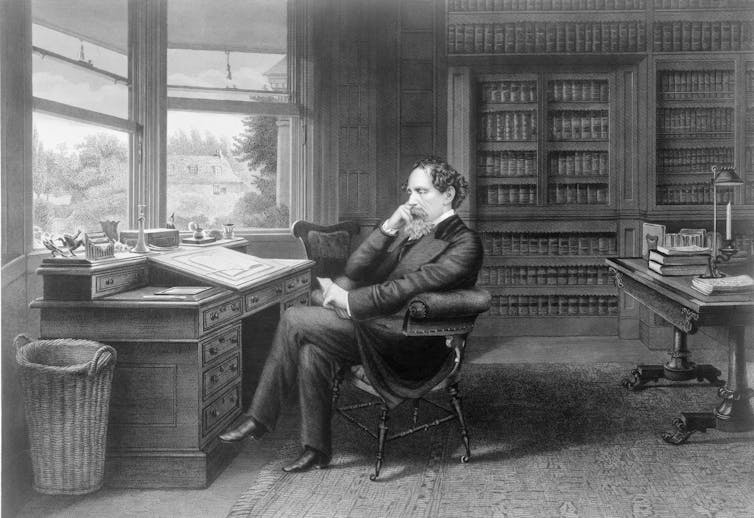

Charles Dickens: how two novelists gave Great Expectations a second life in the Pacific

Charles Dickens’ first biographer, John Forster, ended The Life of Charles Dickens in 1874 with the Dean of Westminster’s sermon. This was delivered in Westminster Abbey on June 19 1870, three days after the novelist’s funeral. Dickens’s grave in Poets’ Corner would, said the dean:

henceforward be a sacred one with both the new world and the old, as that of the representative of literature, not of this island only, but of all who speak our English tongue.

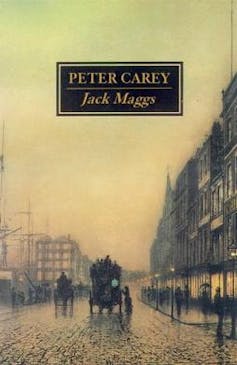

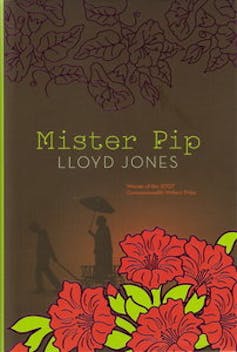

In the century and half since his death, writers from the southern hemisphere have continued to recast Dickens’s fictions in new forms. Two novels – Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs (1997) and Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip (2007) – rework Dickens’s Great Expectations (1859-60).

In so doing, they present readers with opportunities to rethink ways in which Dickens was “a representative of literature”; including the power relations around class and colonialism that have shaped the transmission of writing in “our English tongue” for the past two centuries.

Altered Expectations

In Jack Maggs, Carey – a double Booker Prize-winning Australian novelist – rewrites Great Expectations from the perspective of a convict who returns from his sentence in the new world to terrible risk: the only sure thing that old England can offer him is a noose. Dickens’s original novel sees the world from the shifting perspective of Philip Pirrip – or “Pip” – an orphan boy plucked from obscurity who thinks he has been “made” by the wealthy Miss Havisham. In fact his fortunes have been advanced by Abel Magwitch, a convict who the young Pip had helped in an escape bid.

In Carey’s pastiche, Magwitch becomes Jack Maggs, who has survived transportation to Australia and become a successful and wealthy brickmaker. He returns from the British colony of New South Wales to the London of 1837, the year during which Dickens rose to fame. Maggs wants contact with Pip – rendered here as the young man Henry Phipps, whom he has made into a gentleman.

Instead, he encounters the young, upwardly mobile novelist Tobias Oates: ambitious, anxious to hold onto the new respectability he has secured after childhood poverty, and riddled with emotional and financial insecurities. Oates is of course a version of the young Dickens prior to the consolidated public image of the respectable literary giant commemorated in Forster’s biographical portrait.

Carey reminds us, through Oates, that the Dickens of 1830s closely observed a London world of crime and sexual misdemeanour that could scarcely be rendered in the language of fiction available to him. Dickens also flirted with the new science of mesmerism, a technique which Oates applies to Maggs to exorcise him of the “phantoms” or traumas of brutalised convict life. Oates thereby appropriates Maggs’s story as a series of “burgled secrets” which are to be recast as a crime melodrama for his own literary gain.

Yet Carey reverses this invasive power relation and enables Maggs to tell his own story, restoring him to his own emotionally scarred but resilient origins. Carey concludes with the image of Maggs as redeemed Australian subject who has exorcised the phantoms of English class longings, and is restored to his family in the new world.

Pip In The Pacific

Lloyd Jones’s Mr Pip transports Great Expectations to the Pacific, the conflicted island of Bouganville in Papua New Guinea. The New Zealand novelist writes about the reading and interpretation of Dickens’s novel among a group of black children and their eccentric, self-appointed white teacher, Mr Watts, as an event punctuated by the rebel insurgence, military occupation and horrific violence experienced in the 1990s.

If Dickens wrote Great Expectations as a tale of betrayal, guilt and ambiguous origins in 1860, Jones’s novel shows how that moral and emotional frame can be adapted to new, post-colonial conditions. Matilda is Jones’s 14 year-old fatherless narrator, who comes to appreciate that Pip’s story of mobility and self remaking, which the migrant Mr Watts reads to his pupils as a source of inspiration, is powerfully apt for those whose lives are subject to displacement and migration.

But the “Pip” that Matilda venerates by writing his name, in shells, on the beach is mistaken by military occupiers as the name of a rebel who is being concealed by the villagers. In a terrible unfolding of misunderstandings, both Matilda’s mother and Mr Watts are butchered.

As Matilda escapes to a life of education and possibility, reunited with her migrant father in Australia, she comes to realise that the Great Expecations that Mr Watts read to them was in fact an abridged format for the children of empire: that Dickens’s “sacred” text existed in multiple versions.

Jones’s story casts powerful new light on the way in which Dickens can be seen as a leading “representative of literature”. In one sense, Dickens was the great author of Forster’s biography, buried in Poet’s Corner. In another, as Matilda comes to recognise, the name “Dickens” helped to drive and commodify the global transmission of Victorian literature in many different formats to many new parts of the globe.

As Regenia Gagnier’s research on the global circulation of Dickens and other Victorians shows, literature itself is always in a process of migration to and through new power relations.![]()

David Amigoni, Professor of Victorian Literature, Pro Vice-Chancellor for Research and Enterprise, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Study Of 62 Countries Finds People React Similarly To Everyday Situations

Mozart May Reduce Seizure Frequency In People With Epilepsy

Engineers Find Neat Way To Turn Waste Carbon Dioxide Into Useful Material

Media Stereotypes Confound Kids' Science Ambitions

These W.A. Plants Are Putting Ants To Work

Disclaimer: These articles are not intended to provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Pittwater Online News or its staff.