Inbox and environment news: Issue 458

July 19 - 25, 2020: Issue 458

North Avalon Beach Headland Changes Again: Storm Swell July 2020

The low-pressure system sent powerful surf onto the coastlines, arriving on Tuesday, and has been the cause of the Bureau of Meteorology issuing Hazardous Surf Warning all week. By Saturday the unrideable waves became smoother, causing experienced surfers to find and ride the swell as the waves hollowed out on some beaches.

More photos from along our stretch of beaches in this week's Pictorial.

Mona Vale Photography Competition

Blue Cinema Ep 1: SURFACE

Guide to the classics: The War of the Worlds

Spoiler alert: this story details how The War of the Worlds ends.

The latest screen adaption of H. G. Wells’ 1898 modern masterwork The War of the Worlds will hit our screens this week. Continuously in print since its first publication, the book is a literary gift that keeps on giving for producers and screenwriters. They recognise the story’s unerring capacity to find its mark with each generation.

Wells – who also wrote The Time Machine (1895) and The Invisible Man (1897) – helped pioneer the science fiction genre when he conceived this astonishing book. With an eyewitness narration that reads grippingly still, it tells of a Martian invasion of Earth.

Shock And Awe

Set in London, Wells depicts a complacent world; of men “serene in their assurance” of their dominion over the planet. But humans get the shock of another reality when suddenly visited upon by blood-feeding and squid-like creatures possessed of “intellects vast and cool” that are “unsympathetic” to Earthlings whose planet they had long “regarded with envious eyes”.

An advance party arrives inside metal cylinders shot from giant cannons stationed on Mars. From the cylinders come dozens of Martians, each operating a three-legged metal “fighting-machine” that attacks London’s helpless population by means of a “heat ray”. From these “whatever is combustible flashes into flame”, metal liquifies, glass melts and water “explodes into steam”.

Fleeing like rats from a burning ship, panic spreads like a contagion. The narrator describes a breakdown of law and order, and undergoes something of a breakdown himself.

Upper-class women arm themselves as they cross the country, because traditional deference has gone up in smoke. The “social body” of organisation – police, army, government – suffers “swift liquefaction”.

The Martians, however, had become too intelligent for their own good. They had made the Red Planet disease-free but forgotten about germ theory. And so while laying waste to London, they inhale a bug; a simple bacteria “against which their systems were unprepared” and so suffered a “death that must have seemed to them as incomprehensible as any death could be”.

London will rise again. The world has been spared. Humanity gets lucky — this time.

Read more: Science fiction helps us deal with science fact: a lesson from Terminator's killer robots

A Wider War

In the new Anglo-French television series, La Guerre Des Mondes, the action takes place in both London and France. Martian devastation is given wider latitude.

Why does this now-familiar story have such a hold on successive generations? Iterations include the Orson Welles’ radio broadcast of “fake news” bulletins about Martian invasion, to the 1978 contemporary music version with Richard Burton narration, to Steven Spielberg’s film blockbuster starring Tom Cruise. Last year also saw a BBC production set in Edwardian London.

One response is to consider our attraction to sci-fi. It sees the laws of science upended. Technology seems to make anything possible and to minds already accustomed to real technological transformation, sci-fi literature brings the now-thinkable future into the present.

But there’re less obvious elements to think about: themes that were important in 1898 and resonate still.

Invasion And Imperialism

Wells’ book touched something existentially British during their Pax Britannica period of relative peace. Across the Channel, Europe seethed with diplomatic intrigue and tensions culminating in the first world war.

The new sci-fi genre connected to an older “invasion literature” genre; a long-standing British apprehension of the Continent, especially its renascent German threat. Wells hints at this when he writes that the arrival of the cylinders (before the Martians emerged from them) “did not [initially] make the sensation that an ultimatum to Germany would have done”.

Then there’s the imperialism angle. Was Wells tapping a source of late-Victorian shame at the true source of British wealth and power? Then, a quarter of the world map was coloured British Empire pink. London was the epicentre of modern imperialism — the coordination point for the suffering of millions and the plunder of their lands.

Moreover, Belgium, Germany, France, and also the USA, were engaged in the “scramble for colonies” in Africa and Asia. Under the veneer of sci-fi, Wells describes what it’s like to be a people facing a powerful invader.

Fear Is The Contagion

A very different perspective says something about our species and our idealised self-conception. In 1908 the Russian novelist and revolutionary Alexander Bogdanov, drew on WOTW for inspiration. In his novel Red Star protagonist Leonid travels to Mars to learn about communism from Martians who had made their own revolution and now lived in peace. Leonid despairs of the congenitally “unstable and fragile” nature of human relationships and looks to another planet for guidance.

The Earth-bound communist project of the 20th century ended badly, to say the least. But our human vulnerability to invasion, to tyranny, to economic catastrophe, and even to the bacteriological danger from microbes resistant to antibiotics, continues to haunt us.

The latest adaptation is set in our time with smartphones and the internet. Here again our 21st-century complacency is shattered, and our vulnerability laid bare.

Fear is a contagion in WOTW, and its Londoners show little heroism in the face of an alien invader.

Read more: Science fiction builds mental resiliency in young readers

A New Battle

Bacteria did in Wells’ Martians and might do for us too – unless drugs to overcome resistance are developed. Through sci-fi, we can explore our fear of the invisible foe.

Global warming might be our other enemy – the red skies of Australia’s last bushfire season fresh in our memory and reminiscent of Well’s novel.

The narrative provides a hugely enjoyable fantasy. But we need to think about what science fiction might be doing to our relationship with science fact, especially if we consume it as a tranquilliser to displace and sublimate our fears of invisible threats.

If we do, then the incomprehensibility felt by Wells’ Martians may add that little bit more to our discord regarding the sources and solutions to global warming. Humans got lucky in The War of the Worlds. They didn’t need to do anything to survive. We can’t count on luck to save us or our planet.

War of the Worlds double episode will premiere July 9 on SBS and continue weekly from July 16. Episodes will be available on SBS On Demand on the same day as broadcast.![]()

Robert Hassan, Professor, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A rare discovery: we found the sugar glider is actually three species, but one is disappearing fast

Most Australians are familiar with the cute, nectar-loving sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps), a marsupial denizen of forests in eastern and northern Australia.

However, our new study shows the sugar glider is actually three genetically and physically distinct species: Petaurus breviceps and two new species, Krefft’s glider (Petaurus notatus) and the savanna glider (Petaurus ariel).

This discovery has meant the distribution of the sugar glider has substantially reduced, and it’s now limited only to coastal regions in southeastern Australia. The devastating bushfires last summer hit this part of Australia hard.

Read more: Summer bushfires: how are the plant and animal survivors 6 months on? We mapped their recovery

Our new species from northern Australia, the savanna glider, is particularly at risk, living in a region that’s suffering ongoing small mammal declines. We must urgently assess the conservation status of both the sugar glider and savanna glider before they’re lost.

Nature’s BASE-Jumpers

Our discovery of new Australian mammal species is rare and exciting. That’s because while Australia is filled with hidden and undiscovered animal and plant diversity, our mammal fauna is considered relatively well known, with more than 99% of all species scientifically described.

Perhaps Australia’s most graceful mammals, species of the genus Petaurus (meaning “rope-dancer”) have the unique ability to expand the skin between wrist and ankle to glide from tree to tree – they are nature’s BASE-jumpers. It’s believed these gliding capabilities evolved as a way to adapt to the open forests of Australia.

The palm-sized sugar glider, named after its insatiable appetite for all things sweet, is the most widely known member of the genus and is commonly kept and bred in captivity around the world.

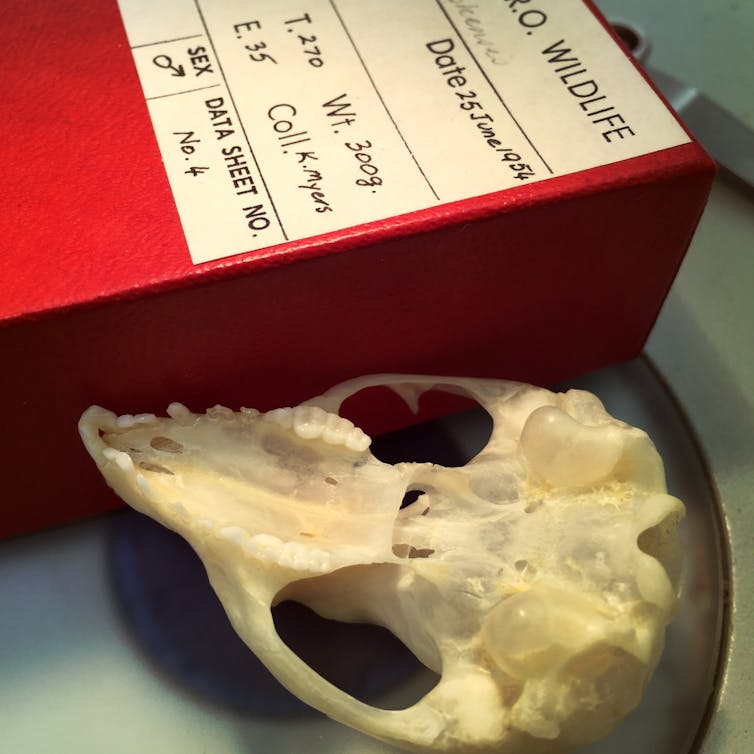

From The Aussie Outback To London’s Natural History Museum

An investigation into sugar glider genetics a decade ago highlighted two divergent groups within the species, suggesting sugar gliders may represent more than one species.

In that study, scientists also unexpectedly found that one glider from Melville Island in the Northern Territory was genetically distinct from sugar gliders. Instead, this Melville Island glider showed a close relationship with two larger existing species, the squirrel glider (Petaurus norfolcensis) and mahogany glider (Petaurus gracilis).

Prompted by this unusual finding, we investigated the mysterious glider’s identity.

From some of the most remote areas of outback Australia to our vast national museum collections, and ultimately the hallowed halls of London’s Natural History Museum, we captured, measured and compared every glider we could find to evaluate their relationships.

Indigenous knowledge of the savanna glider Petaurus ariel and the contributions of local Aboriginal people were also invaluable to our investigation.

The savanna glider is culturally significant and valued across multiple language groups in northern Australia and we are grateful to the Traditional Owners for sharing their knowledge of the species and its habitat.

In the end, we assessed more than 300 live and preserved specimens and established three species where once there was one.

Meet The New Gliders

The savanna glider lives in the woodland savannas of northern Australia and looks a bit like a squirrel glider with a more pointed nose, but much smaller. The remaining two species look similar to each other and may overlap in some areas of southeastern Australia.

Krefft’s glider has a clearly defined dorsal stripe and fluffy tail. It is widespread in eastern Australia and has been introduced to Tasmania.

The sugar glider, with a less-defined dorsal stripe, is apparently restricted to forests east of the Great Dividing Range, extending from southeast Queensland to around the border of New South Wales and Victoria.

What Does This Mean For Sugar Gliders?

Despite ongoing debate about the role of taxonomy (the science of classifying species) in conservation, it is clear from our work that species definitions provide an essential foundation for effective conservation.

When considered as one species, sugar gliders were widespread, abundant and officially classified as “least concern”.

The distinction of these three species has resulted in a substantially smaller distribution for the sugar glider, making the species vulnerable to large scale habitat destruction, such as the recent bushfires.

And sadly, the bushfires have incinerated a large proportion of the sugar glider’s updated range. Given they are tree hollow users and require a diverse habitat with a variety of foods, the bushfires have most likely had a devastating effect on this much-loved species.

The Savanna Glider Is Disappearing

Our work has shown urgent intervention is needed to save this important plant pollinator and icon of the Australian bush.

The savanna glider in particular is facing its own conservation concerns in the ongoing northern Australian small mammal declines. Tree-dwelling mammals are among those worst affected there, and it appears the savanna glider is no exception.

An earlier study of ours showed the species has undergone a 35% range reduction over the last 30 years, and is slowly disappearing from the inland areas it once inhabited. It’s likely feral cats, changed fire regimes and feral herbivores have played a significant role in the savanna glider’s vanishing range.

It would be a tragedy if this species is lost to the world just as it was discovered, especially with Australia’s appalling track record of human-induced mammal extinctions.

Read more: Scientists and national park managers are failing northern Australia’s vanishing mammals

More scientific work is urgently needed. We must define the distinct ecology of each species and determine their distribution in more detail.

This will enable us to effectively assess the conservation status of each species and determine what management efforts are required to ensure their protection as they face an uncertain future.![]()

Teigan Cremona, Research Associate, Charles Darwin University; Alyson Stobo-Wilson, Postdoctoral Research Associate, Charles Darwin University; Andrew Baker, Senior Lecturer, Queensland University of Technology; Steve Cooper, Principal Researcher , South Australian Museum, and Sue Carthew, Provost and Vice President, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

1 in 5 PhD students could drop out. Here are some tips for how to keep going

Doctoral students show high levels of stress in comparison to other students, and ongoing uncertainty in terms of graduate career outcomes can make matters worse.

Before the pandemic, one in five research students were expected to disengage from their PhD. Disengagement includes taking extended leave, suspending their studies or dropping out entirely.

COVID-19 has made those statistics far worse. In a recent study, 45% of PhD students surveyed reported they expected to be disengaged from their research within six months, due to the financial effects of the pandemic.

Many factors influence whether a student completes their doctorate. They include supervision support (intellectual and pastoral), peer support (colleagues, friends and family), financial stability and good mental health.

In our recently published book The Doctoral Experience Student Stories from the Creative Arts and Humanities – which we edited with contributions from PhD students – students outlined their experiences of doing a doctorate and shared some useful strategies for how to keep going, and ultimately succeed, in the doctoral journey.

A Deeply Personal Journey

Completing a doctorate involves much more than generating knowledge in a specific discipline. It is a profoundly transformational process evolving over a period of at least four years — and often longer.

This entails personal questioning, development in many areas of life, and often a quite significant personal and intellectual reorientation. The PhD brings with it high expectations, which in turn creates high emotional stakes that can both inspire and derail students. This is coupled with coming to see and think about the world very differently — which for some can be a daunting prospect, as all previously held assumptions are thrown into disarray.

Such a profoundly existential process can itself engender anxiety, depression and trauma if students are not equipped with the self-care strategies that enable resilience.

Read more: PhD completion: an evidence-based guide for students, supervisors and universities

Every chapter in our book, written by a different student, emphasises the need to engage in deep thinking and planning regarding their personal goals, strengths and weaknesses, and ways of working before starting the PhD.

This is important preparatory work to ensure any challenges that arise are surmountable.

In her chapter, Making Time (and Space) for the Journey, AK Milroy writes she learnt to

[…] analyse and break down the complicated doctoral journey into a manageable, achievable process with clear tasks and an imaginable destination.

She writes this includes involving family and friends in the process because

[…] it is paramount to ensure these people understand the work that lies ahead, and also that they too are being respected by being included in the planning.

Relationships were, above all, a critical component of the experience for many of the student writers. The supervisory relationship is the most obvious one, which Margaret Cook describes as the student undertaking a form of academic apprenticeship.

Read more: Ten types of PhD supervisor relationships – which is yours?

The student authors also identify strategies for the “thinking” part of the research process once enrolled. These include acknowledging that the free and creative element of mind-wandering and downtime are as legitimate as the focused, task-oriented work of project management, such as preparing checklists and calendars.

AK Milroy calls these “strategic side-steps”.

Peter Mackenzie, who researched regional jazz musicians, went a step further to connect with his participants.

I felt like an outsider but once I started to play with the guys on the bandstand that night at the Casino, I sensed a different level of appreciation from them. After playing and taking on some improvisations, I could feel the group relax. I was no longer an outside musician. Even better, I wasn’t seen as an academic. I was one of them.

Struggling With Self Doubt

The task of writing, of course, cannot be ignored in the long doctoral journey.

Drafting and redrafting, jettisoning ideas and arguments along the way, is acknowledged as a core component of the doctoral learning process itself, and the many attempts are not proof of failure.

Gail Pittaway writes about extending networks beyond one’s supervisors and university to collaborate with those in the discipline nationally and internationally.

This can be productive and lead to co-written articles and editing special issues of journals, which can positively influence the PhD thesis.

[…] by developing confidence in sharing ideas, seeking peer review feedback and editorial advice from a wider range of readers as some of these sections are submitted for publication, the writing of the thesis is encouraged and energised.

Many of the student authors acknowledge questioning, self-doubt and fear of the unknown are central to creating and performing research. While this might be frightening, they say it should be embraced as this is where innovation and novelty can arise.

Charmaine O'Brien writes about how transformative learning is dependent on this period of complexity and not-knowing. While “failure to make experience conform to what we already know is threatening because it destabilises a sense of how we know the world, and ourselves in it, resulting in psychological ‘dis-ease’”, staying with it – and having supportive supervisors – ensures the student becomes a doctoral-level thinker.

Read more: Mindfulness can help PhD students shift from surviving to thriving

Lisa Brummel writes of extending requirements of occupational health and safety into her own life. This takes forms such as family, friends and exercise, assisting with work-life balance and good mental health.

After all, two of the most significant resources PhD students possess to do the work required are their physical and mental capacity.

Finally, students must love their topic. Without an innate fascination for the field in which they are researching, this often tumultuous intellectual, emotional and personal journey may derail.

In the four-plus years spent doing a doctoral degree, any range of major life events can occur. Births, deaths, marriages, separations and divorces, illnesses and recovery, are all possible. Being willing to seek help and knowing who to ask can be the difference between completing and collapsing.

There is no pleasure without pain in the doctoral journey, but with the right frame of mind and supportive supervisors, the joys certainly outweigh the suffering.![]()

Craig Batty, Professor of Creative Writing, University of Technology Sydney; Alison Owens, Senior Lecturer, Learning and Teaching Centre, Australian Catholic University; Donna Lee Brien, Professor, Creative Industries, CQUniversity Australia, and Elizabeth Ellison, Senior Lecturer, Creative Industries, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Gang-Gang Cockatoos – Capertee Valley

Stay Healthy During The HSC

In any ‘normal’ year the HSC requires dedication and focus as well as the support of friends and family.

This year hasn’t exactly panned out to be a ‘normal’ year, with announcements about changes to the HSC due to COVID-19.

Despite all the goings-on, students across NSW are continuing to study for their HSC with focus and determination, and we at NESA are here to help.

This year we are partnering with mental health organisation ReachOut to deliver news, information, guidance and advice to support all HSC students.

You’ll hear from experts, teachers, parents and other students as well as some inspiring spokespeople. This year we are planning to lighten your mental load with practical tips and tricks for staying active, connected and in charge of your wellbeing.

ReachOut’s Study Hub has heaps of info about taking a proactive approach to your mental health or where to go if you need more support. ReachOut’s Forums are great for sharing what’s going on for you and get ideas about the best ways to feel happy and well.

So follow and use #StayHealthyHSC for regular health and wellbeing updates and information.

View our range of social media images, posters and flyer to help you get involved and share the Stay Healthy HSC message with your community.

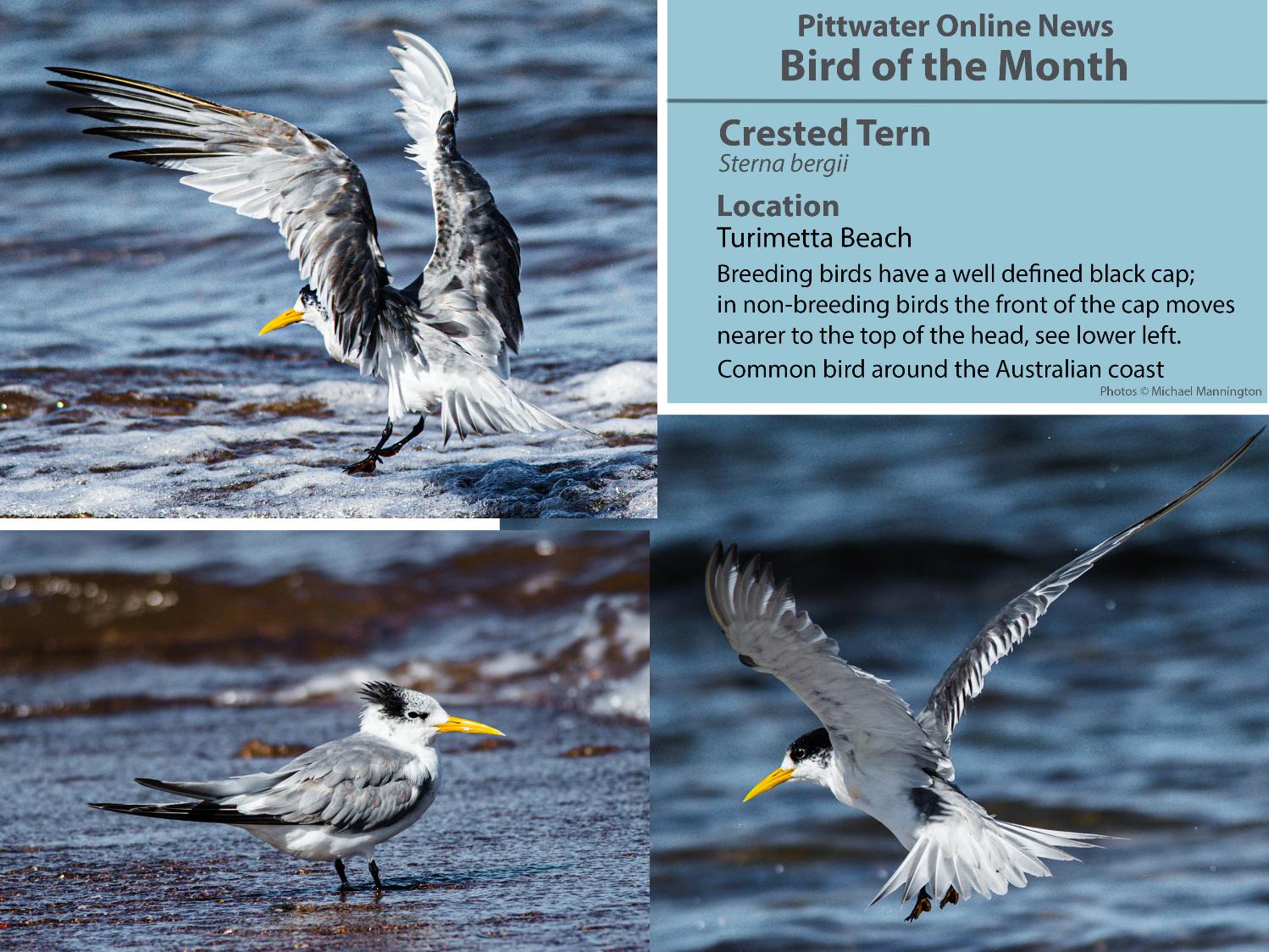

BirdLife Australia 2020 Photo Comp

Tick Population Booming In Our Area

Residents from Terrey Hills and Belrose to Narrabeen and Palm Beach report a high number of ticks are still present in the landscape. Local Veterinarians are stating there has not been the usual break from ticks so far and each day they’re still getting cases, especially in treating family dogs.

To help protect yourself and your family, you should:

- Use a chemical repellent with DEET, permethrin or picaridin.

- Wear light-colored protective clothing.

- Tuck pant legs into socks.

- Avoid tick-infested areas.

- Check yourself, your children, and your pets daily for ticks and carefully remove any ticks using a freezing agent.

- If you have a reaction, contact your GP for advice.

Pittwater Powerful Owl Nesting Site Razed: Chicks No Longer Present

Sad news as another action of bad land management in the Northern Beaches LGA causes one Powerful Owl family to abandon the nest hollow on Friday June 26th, along with the chicks that would have been inside the hollow. This pair are known to be regularly having chicks at this time of year (Winter is breeding season for Powerful Owls) and the site is in Pittwater.

There are 30 registered with Council Powerful Owl sites across the northern beaches. It has been suggested a process whereby landowners are notified they are buying or have bought a block in a sensitive area, with endangered species present, form part of Council’s processes. This site was cleared not only of weeds but native species and all understorey as well parts of the council and community owned reserve adjacent to it.

Although Council officers ordered a stop work, the contractors ceased then returned the very next day to complete their razing of the site.

The Council Reserve cleared by contractors employed by private landowners - photo supplied

Pittwater Online News will run more on the Powerful Owl Project and what we can do to help look after these other local residents after the Winter School holidays.

If you are noticing the loss of your resident POs through fire, nest site vegetation removal, dog-walking, bike riding or visitation/photography, you are not alone. This season the Powerful Owl Project have already recorded three owl families moving away from nest trees in response to these activities. In one case the first nesting was early enough that the owls have made a second attempt at breeding, but for our Pittwater owl family - there will be no chicks that survive this year. You may have read about them here in December 2019:

Powerful owls: the reason to protect remnant bushland in our cities by Andrew Gregory. Australian Geographic, December 29, 2019.

Powerful Owl at Clareville - photographed by Paul Wheeler in June 2014

Mona Vale-Warriewood-Turimetta Headland Views On A Winter's Afternoon

Photos taken July 13, 2020 - by A J Guesdon.

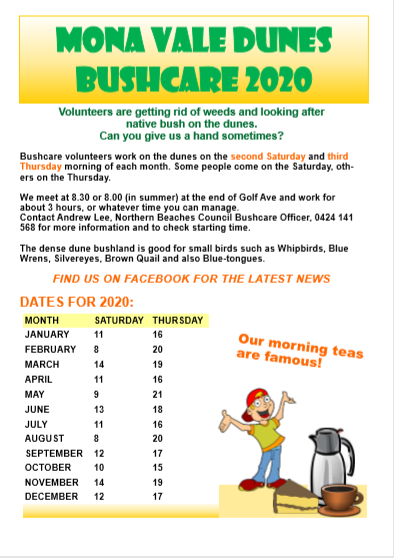

Bushcare Is Back!

Protocols are now in place so you can get involved in your local bushcare group again or sign up to help out to see your investment in your community grow - literally!

Find out how in: Bushcare is Back

Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park Precinct Closures Update

Many COVID-19 restrictions have now been lifted from visitor precincts and facilities In Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. However, several tracks and trails will remain closed while upgrades and remediation works are completed. These closures include:

- Bobbin Head playground

- Warrimoo walking track - public access may be restricted on Wednesday 17 and Thursday 18 June.

- The Basin trail

- The Basin campground and picnic area

- Mackerel service trail

- Salvation Loop and Wallaroo trails

Berowra track, between Apple Tree Bay and the intersection of Mount Ku-ring-gai track, has now reopened. However if you plan to visit, walk with caution as some sections of the track remain uneven.

Closed areas: The Basin campground, Basin trail and Mackerel service trail closed

The following areas will be closed from Monday 1 June until Monday 3 August 2020 while upgrade works and maintenance are underway:

- The Basin trail

- The Basin campground and picnic area

- Mackerel service trail

No public access is permitted. There will be no access to The Basin Aboriginal Engraving Site, Mackerel Beach to The Basin trail, West Head Road or The Basin campground.

For further information call 02 9451 3479 or 02 9472 8949.

Closed areas: Salvation Loop and Wallaroo Trails closed for maintenance.

The Salvation Loop Trail and Wallaroo Trail at West Head will be closed from 2 June 2020 until early July 2020 for maintenance. Machinery will be on the trails so no public access is permitted for safety reasons.

For further information contact; (02) 9451 3479 or (02) 9472 8949

Please remember to practice appropriate social distancing requirements and good hygiene. From Saturday 13 June, the maximum group size for an outdoor gathering will be increasing from 10 to 20 people. Groups are still expected to maintain social distancing. If you arrive at a national park or other public space and it is too crowded to practice social distancing, it is your responsibility to leave the area. Do not wait to be instructed by NPWS staff or police.

The closure of toilets and other facilities will be decided on a case-by-case basis. Necessary site assessments will take place to consider the management of health and safety risk to visitors and staff, and available resourcing to maintain facilities. Access to sanitation products and running water cannot be guaranteed. We recommend bringing hand soap, hand wipes and toilet paper with you to maintain good hygiene as advised by the NSW Government.

If you're visiting the park, please bring a card to pay vehicle entry fees.

For more information about closures, call the NPWS Contact Centre on 1300 072 757, the NPWS North Western Sydney area office on 02 8448 0400 or the NPWS Sydney North area office on 02 9451 3479.

Penalties apply for non-compliance.

Hope For Endangered Butterfly As Central Tablelands Caterpillars Dig Deep To Survive Fires

July 8, 2020

There’s hope for an endangered species of butterfly found only in the Central Tablelands, as scientists confirm clever caterpillars of the purple copper butterfly may have buried themselves underground to shelter from last summer’s bushfires.

“The purple copper butterfly is found only in the central tablelands of NSW and as the fires passed through Lithgow, we were concerned about the impacts of the fire on both the butterfly and its habitat,” said Jess Peterie, Threatened Species Officer, Department of Planning, Industry and the Environment.

The NSW Government’s Saving our Species program recently surveyed 12 fire affected sites around Lithgow, and the results were more positive than first thought.

“Some sites had unburnt patches of habitat that we think gave shelter for the caterpillar life stage of the butterfly.

“We suspect the larvae dug deep into ant nests to survive the fire,” Ms Peterie said.

“Blackthorn bushes, the butterfly larvaes' main food source, were also regrowing in significant numbers, meaning the larvae has the food needed to grow and develop.

“Because the butterfly is so rare and only active for a few months each year, we won’t know the exact impact on adult butterfly numbers until spring this year when we do more surveys.”

Just before the bushfires hit, the purple copper butterfly was spotted for the first time in 10 years on a private property near Mt David, just outside of Bathurst, where it was thought to be locally extinct. The butterfly was also found at a new site not too far away from the Mt David population.

“Given the findings from last year’s survey, undertaken in partnership with the Central Tablelands Local Land Services (LLS), and the positive post-fire habitat surveys, we are hopeful for the future of this species,” Ms Peterie said.

Community awareness and involvement is one of the key priorities in the purple copper butterfly conservation effort.

The butterfly's habitat is a subspecies of Blackthorn often found in open eucalypt woodland. Land managers with this habitat can help protect this species by letting Saving our Species know if there are signs of the purple copper butterfly living on the property.

The purple copper butterfly is smaller than a lot of people imagine, with a wingspan of about 2 cm. It can be identified by its collage of colours - bronze, green, blue, deep brown and of course purple undertones.

Butterflies are not only a beautiful insect but play several roles in the environment. They act as a pollinator; as a food source for other species; and are an important indicator of a healthy ecosystem.

To contact Saving our Species with any information or queries about the purple copper butterfly, please email savingourspecies@environment.nsw.gov.au.

To find out more visit: Purple copper butterfly

Paralucia spinifera (Purple Copper Butterfly, Bathurst Copper Butterfly) Photo: Stuart Cohen/DPIE

Emergency Actions As Drought Hits Critically Endangered Plant In Mount Kaputar National Park

July 7, 2020

The National Parks and Wildlife Service and the Australian Institute of Botanical Science recently took emergency action after drought severely impacted a critically endangered plant in Mount Kaputar National Park.

National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) Project Officer James Faris said emergency measures were enacted under the NSW Government’s Saving our Species program, when it was discovered just three adult plants of Zieria odorifera ssp. copelandii remained.

“Zieria odorifera ssp. copelandii is a small shrub growing to 20 centimetres high on hard rock faces.

“This is an extremely rare plant species that is only found in the western part of Mount Kaputar National Park.

“This species was so badly impacted by the drought, I personally carried water up the mountain on the weekends during the worst of the dry and watered each of the plants.

“Despite our best efforts, drastic measures had to be taken, when their numbers fell to just three adult plants.

Zieria odorifera ssp. copelandii - Photo: NSW DPIE

“Surveys were immediately undertaken across the site to locate any additional plants. As part of this work, approximately 300 seedlings were located within the site. This has given us some hope that the population will increase,” Mr Faris said.

Scientists based at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan have now harvested a small amount of genetic material for propagation from two of the adult plants plus removing 20 seedlings from the site in the hope of securing its survival.

Dr Peter Cuneo is the Manager of Seedbank and Restoration Research at the Australian Institute of Botanical Science and is based at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan.

“25 healthy seedlings are currently growing at the Nursery at the Australian Botanic Garden Mount Annan, which will help provide an insurance policy against the extinction of these native plants in the wild,” said Dr Cuneo.

Mr Faris said other measures were also underway to protect the remaining plants on site.

“While not impacted by fires which hit parts of Mount Kaputar National Park recently, the plants are susceptible to trampling by visitors and from browsing by macropods and feral animals.

“Cages have now been constructed around the plants to protect them from this kind of disturbance,” Mr Faris said, “these measures are being undertaken alongside pest management in the park.

“Reducing the number of goats and other feral animals reduces the browsing pressure on all flora species.

“We will also be undertaking further follow up surveys within likely habitat to try and find any additional populations of the species.

“The more information we can gather on this species will help us to better understand, manage and monitor the threats it faces.

“There has been some good rainfall in the area since the beginning of the year and we are continuing to monitor the population. Hopefully they will flower and set seed in spring,” Mr Faris said.

The Saving our Species program is the NSW Government's commitment to securing the future of the State's threatened plants and animals. To find out more, or to get involved with Saving our Species visit Help save our threatened species.

Mount Kaputar National, Project Officer James Faris Photo: Media/DPIE

New Bridge Open At Warrumbungle National Park

July 9, 2020

Access to campgrounds at Warrumbungle National Park has been improved by a new pedestrian bridge, completed as part of one of the state’s largest park infrastructure projects.

NPWS Area Manager John Whittall, said the Mopra Creek Pedestrian Bridge would provide greater accessibility for seniors, families, and those with special needs or reduced mobility.

“I’m proud to announce the opening of this bridge, which signifies a long-term commitment to improving access to national parks in NSW,” Mr Whittall said.

“It’s great to see the project come to fruition in time for the July school holidays, and I hope many visitors will make use of it over the coming weeks.

“The bridge will allow for safer and easier pedestrian access between campgrounds, which is particularly important as we’ve seen a rise in campers since travel restrictions eased.

“With overseas travel off the table a lot of people seem to be holidaying and adventuring locally, which is really great for the local economy and encouraging for these communities.”

The Mopra Creek Pedestrian Bridge was completed in just 40 days and was funded by the state government’s Improving Access to National Parks Program (IANPP).

The IANPP is the largest ever investment in visitor infrastructure within NSW’s national parks, with $150 million provided to improve access and visitation over 4 years.

NPWS reminds all campers that bookings are essential in order to meet the current public health guidelines.

For more information visit: Camping safety

Mopra Creek Pedestrian Bridge, Warrumbungle National Park Photo: Media/DPIE

Cudgen Nature Reserve Expanded To Protect More Koala Habitat

July 9, 2020

The NSW Government has acquired an additional 89 hectares of land to expand Cudgen Nature Reserve and aid the recovery of the Tweed koala population.

Environment Minister Matt Kean said the addition would help to provide long-term habitat protection for native plants and animals on the Tweed Coast, including the endangered Tweed and Brunswick Rivers koala colony.

“Securing land for koala habitat conservation is one of my priorities as Environment Minister as well as a core pillar of the NSW Koala Strategy, which aims to secure the future of koalas in the wild,” Mr Kean said.

“This addition is a significant boost for koala conservation on the Tweed Coast. It will protect core koala habitat and reduce the potential for fragmentation.

By working with Tweed Shire Council on a mutually beneficial land exchange, we’ve managed to increase the area of koala habitat protected in Cudgen Nature Reserve and also provide a site that council can use as a koala holding and soft release site to aid sick and injured koalas.

Member for Tweed Geoff Provest said, “By adding this land to national parks system, we’re building a better connected reserve for Tweed Coast koalas, ensuring there will be a safe home for the colony in perpetuity.”

“Cudgen Nature Reserve is part of the largest remaining stand of native vegetation on the Tweed Coast. It is home to an exceptionally high diversity of native animal and plant species.

“In addition to koalas, the reserve is home a number of threatened and endangered animal species, including the long-nosed potoroo, the glossy black cockatoo and the little bent-wing bat.

The Cudgen Nature Reserve, is located on the Tweed Coast in far north-eastern NSW, has a total area of 897.4 hectares. The reserve is considered to be of regional and state significance for the conservation of native fauna.

Koala between the Tweed and Brunswick Rivers east of the Pacific Highway - Credit Scott Hetherington DPIE

Koalas, Birds And Boardwalks - Coffs Coast National Parks Booming

July 9, 2020

With a $275,000 boardwalk project planned for Muttonbird Island and more than 3500 new koala feed trees growing in Bongil Bongil National Park, the Coffs Coast’s national parks are flourishing.

Environment Minister Matt Kean announced the 330 metre raised boardwalk project for Muttonbird Island during his visit to the Coffs Coast today.

“The elevated boardwalk will improve visitor access to the spectacular nature reserve while also benefiting the island’s most important inhabitants – the muttonbirds,” Mr Kean said.

Member for Coffs Harbour Gurmesh Singh said more than 150,000 people visit Muttonbird Island every year to take in the reserve’s unforgettable views, enjoy whale watching and experience the spectacularly raucous nesting site of the migratory wedge-tailed shearwater.

“The elevated, fibreglass mesh walkway will enhance the views for visitors as they traverse the island as well as lessening the disturbance to shearwaters’ nesting burrows and potentially opening up new areas as nesting habitat,” Mr Singh said.

During his visit to the Coffs Coast, Minister Kean also visited the site of the unique and innovative ‘Tree Parents Project’, which has seen more than 3500 primary koala food trees planted and nurtured in Bongil Bongil National Park thanks to the commitment of the program’s 140 volunteers.

“This innovative community partnership has restored over 50 hectares of degraded koala habitat and is a fantastic example of a rewarding and highly productive partnership between a NSW Government agency and the local community.

As part of the ‘Tree Parents Project’, teams of local volunteers were trained, tooled-up and then offered a two-hectare plot of land within Bongil Bongil National Park to cultivate 60 koala food trees each.

“A total of 3500 food trees, including Tallowwoods, Grey Gums, Swamp Mahoganies and Forest Oaks have been planted on the site,” Mr Kean said.

New England To Light Up With Second NSW Renewable Energy Zone

July 10, 2020

New England will become a NSW powerhouse, with the NSW Government today announcing a $79 million plan to develop a second, massive 8,000 MW Renewable Energy Zone (REZ) in the region.

Deputy Premier John Barilaro said the Government was forging ahead with its plans to deliver new energy infrastructure that will lower electricity bills, create jobs and make regional NSW the home of renewable energy investment.

“The New England REZ is expected to attract $12.7 billion in investment, support 2,000 construction jobs and 1,300 ongoing jobs – all while lowering energy prices and future-proofing the regions,” Mr Barilaro said.

“Regional NSW is the best place in Australia for renewable energy investment and the jobs it creates, and this funding allows us to unlock that potential.”

Energy Minister Matt Kean said the massive 8,000 MW New England REZ was the biggest commitment to cheap, clean energy in the State’s history.

“The nine-fold level of interest in the Central-West Orana REZ was astounding, so it makes absolute sense to go even bigger with the New England REZ,” Mr Kean said.

“The New England REZ will be able to power 3.5 million homes and, when coupled with Central-West Orana REZ, sets the State up to become the number one destination across Australia for renewable energy investment.”

Member for Northern Tablelands Adam Marshall said the REZ represented an excellent opportunity for the region to create jobs, diversify its local economy and improve local roads and telecommunications infrastructure.

“Our region is fast becoming the renewables capital of NSW and we’re home to some of the best renewable energy resources in the country, with flagship wind and solar projects at Glen Innes and Armidale living proof of this potential,” Mr Marshall said.

“Today’s official declaration of New England as an 8,000 MW REZ is a long-awaited milestone for the future of the region and I am determined to see community-wide benefits flow from this announcement.”

REZs involve making strategic transmission upgrades to bring multiple new generators online in areas with strong renewable resources and community support.

The New England REZ is the second Renewable Energy Zone planned for NSW and will be built in stages, with the delivery timetable to be developed throughout the detailed planning process.

For more information go to: Renewable Energy Zones

Blue Mountains National Park Plan Of Management Proposed Amendment: Public Consultation

The Proposed Amendment to the Blue Mountains National Park Plan of Management and Govetts Leap Draft Visitor Precinct Plan are available for public review and comment. View Blue Mountains National Park Proposed Amendment to Plan of Management - PDF, 978kb

Public exhibition of the proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan provides members of the community with an opportunity to have a say in planned improved accessibility works in Blue Mountains National Park. Comments close 17 August 2020.

What is a plan of management?

Parks and reserves established under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 must have a plan of management. The plan includes information on important park values and provides directions for future management. The plan of management is a legal document, and after the plan is adopted all operations and activities in the park must be in line with the plan. From time to time plans of management are amended to support changes to park management or proposed works.

Why is the plan being amended now?

Blue Mountains National Park is the most visited park in New South Wales, receiving more than 8 million visits in 2018. Visitor infrastructure improvements will enhance and disperse the visitor experience and improve protection of the park's values. The improvements to Govetts Leap visitor precinct will elevate the quality of interpretation and promotion of the park's World Heritage values.

The amendment relates to visitor facility upgrades to support both increased and better-dispersed visitation and includes:

- upgraded and increased capacity parking areas at Govetts Leap

- upgraded facilities to allow improved access for people with disabilities and/or restricted mobility

- enable pre-existing overnight stay facilities at Green Gully visitor precinct including a camping area and cabins.

What opportunities will the community have to comment?

The proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan are on public exhibition until Monday 17 August 2020. Everyone is invited to review the amendment and draft visitor precinct plan and provide comments.

When will the amended plan of management and visitor precinct plan be finalised?

At the close of the public exhibition period, we consider all submissions on the plan amendment and prepare a submissions report. We provide the Blue Mountains Regional Advisory Committee and the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council with the proposed amendment, all the submissions and the submissions report. They consider the documents, make comments on the amendment or suggest changes, and the Council provides advice to the Minister for Energy and Environment.

The Minister considers the amendment, submissions and advice, makes any necessary changes and decides whether to adopt the amendment under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. Once an amendment is adopted, it is published on the Department's website and key stakeholders, including those who made a submission on the draft plan, will be notified.

Submissions on the draft visitor precinct plan will be reviewed in conjunction with the Blue Mountains Regional Advisory Committee. The finalised Govetts Leap visitor precinct plan will be published on the Department's website.

How can I get more information about the proposed amendment?

For further information on the plan of management please contact the NPWS Park Management Planning Team at npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Where can I see a printed copy of the proposed amendment?

Copies are available at the following locations:

- National Parks and Wildlife Service Heritage Centre, Blackheath – end of Govetts Leap Road

- Blue Mountains City Council, Katoomba – Ground floor foyer, 2-6 Civic Place

How can I comment on the proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan?

Public exhibition of the proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan is from Friday 26 June until Monday 17 August 2020. You are invited to comment on the amendment by sending a written submission during this time.

To help us make the best use of your feedback:

- Please tell us what issue or part of the plan you are talking about. One way you can do this is to include the section heading and/or page number from the amendment in your submission.

- Tell us how we can make the plan better. You may want to tell us what you know about the park or how you or other people use and value it.

We are happy to hear any ideas or comments and will consider them all, but please be aware that we can't always include all information or ideas in the final plan.

Your privacy

Your submission will be provided to two advisory bodies. Your comments on the draft plan may include 'personal information'. The Department complies with the NSW Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998, which regulates the collection, storage, quality, use and disclosure of personal information. For details see our privacy page. Information that in some way identifies you may be gathered when you use our website or send us an email.

If you indicate in your written submission that you object to your submission being made public, we will ask you before releasing your submission in response to any access applications under the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009.

Have your say

Public exhibition is from 26 June 2020 to 17 August 2020.

You can provide your written submission in any of the following ways:

Post your written submission to:

Manager Planning Evaluation and Assessment

Locked Bag 5022

Parramatta NSW 2124

Email your submission to: npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Make a submission online by using the online form here

Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan Of Management: Public Consultation

The Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management is available for review and comment.

Public exhibition of the draft plan provides an important opportunity for members of the community to have a say in the future management of Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve. Comments close 28 September 2020.

This plan has been prepared using a new format and presented as 2 separate documents:

- The plan of management which is the 'legal' document that will be provided to the Minister for formal adoption. This is the document we are seeking your feedback on.

- The planning considerations document supports the plan of management. It includes detailed information on park values (e.g. threatened species and cultural heritage) and threats to these values. A summary of this information is in the plan of management.

Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve encompasses about half of the Doodle Comer Swamp, an ephemeral wetland listed in the National Directory of Important Wetlands and the largest wetland of its type in southern NSW. The catchment for Doodle Comer Swamp is unregulated and the wetland has an unaltered water flow regime, now uncommon in New South Wales inland wetlands and of high conservation value.

When inundated, Doodle Comer Swamp attracts large numbers of waterbirds that use the swamp for breeding and foraging. When dry, the wetland provides habitat for the threatened bush stone-curlew, listed as endangered in New South Wales. Other threatened animals found include brolga and superb parrot. The reserve contains several threatened ecological communities such as Inland Grey Box Woodland and Sandhill Pine Woodland.

Doodle Comer Swamp is part of the Country of the Wiradjuri speaking nation and is part of a larger network of swamps and lagoons across the Riverina that formed a significant part of the cultural landscape, sustaining the Wiradjuri with an extensive range of resources for thousands of years. A diverse range of Aboriginal sites exist in the reserve and surrounding area and in 2016 Doodle Comer was declared an Aboriginal place recognising these values and the wetland's special significance to Aboriginal culture.

What is a plan of management?

Parks and reserves established under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 need to have a plan of management. The plan includes information on important park values and provides directions for future management. The plan of management is a legal document, and after the plan is adopted all operations and activities in the park must be in line with the plan. From time to time plans of management are amended to support changes to park management. Visit: Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management - PDF, 2.3MB

The National Parks and Wildlife Act sets out the matters that need to be considered when preparing a plan of management. These matters are addressed in the supporting Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management: Planning considerations document.

Why is a plan being prepared now?

Since the park`s reservation in 2011, it has been managed according to a statement of management intent. After a park's reservation and before the release of its plan of management, a statement of management intent is prepared outlining the management principles and priorities for the park's management. This statement documents the key values, threats and management directions for the park. It is not a statutory document and a plan of management will still need to be prepared according to the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974.

Publication of a draft or final plan will replace the statement of management intent for the relevant parks covered.

What opportunities will the community have to comment?

The draft plan of management is on public exhibition until 28 September 2020 and anyone can review the plan of management and provide comments.

When will the plan of management be finalised?

At the end of the public exhibition period in September 2020 we will review all submissions, prepare a submissions report and make any necessary changes to the draft plan of management. The Far West Regional Advisory Committee and the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council will then review the plan along with the submissions and report, as required by the National Parks and Wildlife Act.

Once their input has been considered and any further changes made to the plan of management, we provide the plan to the Minister for Energy and Environment. The plan of management is finalised when the Minister formally adopts the plan under the National Parks and Wildlife Act. Once a plan is adopted it is published on the Department website and a public notice is advertised in the NSW Government Gazette.

How can I get more information about the draft plan?

For further information on the plan of management please contact the Park Management Planning Team at npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au.

How can I comment on the draft plan?

Public exhibition for the plan of management is from 26 June 2020 until 28 September 2020. You are invited to comment on the draft plan by sending a written submission during this time.

Have your say

Public exhibition is from 26 June 2020 to 28 September 2020.

You can provide your written submission in any of the following ways:

Post your written submission to:

Manager Planning Evaluation and Assessment

Locked Bag 5022

Parramatta NSW 2124

Email your submission to: npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Make a submission online by using the online form here

Tollingo Nature Reserve And Woggoon Nature Reserve Draft Plan Of Management: Public Consultation

The Tollingo Nature Reserve and Woggoon Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management is available for review and comment.

Public exhibition of the draft plan provides an important opportunity for members of the community to have a say in the future management of Tollingo Nature Reserve and Woggoon Nature Reserve. Comments close 28 September 2020.

This plan has been prepared using a new format which is presented as two separate documents:

- The plan of management which is the legal document that will be provided to the Minister for formal adoption. This is the document we are seeking your feedback on.

- The planning considerations document supports the plan of management. It includes detailed information on park values (e.g. threatened species and cultural heritage) and threats to these values. A summary of this information is provided in the plan of management.

Tollingo Nature Reserve and Woggoon Nature Reserve are significant as two of the largest remaining mallee remnants in New South Wales. The largely intact old-age mallee vegetation is rare in the Central West, which is mostly used for agriculture. The reserves provide habitat for the endangered malleefowl and other native animals.

Tollingo Nature Reserve is shared Country for the Ngiyampaa and Wiradjuri people, while Woggoon Nature Reserve is within Wiradjuri traditional Country.

What is a plan of management?

Parks and reserves established under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 need to have a plan of management. The plan includes information on important park values and provides directions for future management. The plan of management is a legal document, and after the plan is adopted all operations and activities in the park must be in line with the plan. From time to time plans of management are amended to support changes to park management.

The National Parks and Wildlife Act sets out the matters that need to be considered when preparing a plan of management. These matters are addressed in the supporting Tollingo Nature Reserve and Woggoon Nature Reserve Draft Planning Considerations document. This document may be updated from time to time, for example, to include new information on the values of the park (e.g. new threatened species), new management approaches (e.g. a new pest management technique) or new park programs. Visit Tollingo Nature Reserve and Woggoon Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management - PDF 2.3MB

Why is a plan being prepared now?

This plan of management will replace the statement of management intent which was approved in 2014. Statements of management intent are non-statutory documents which summarise the key values and management directions for a park.

Since reservation in 1988 and 1974 respectively, Tollingo and Woggoon nature reserves have been managed according to a statement of management intent. After a park's reservation and before the release of its plan of management, a statement of management intent is prepared outlining the management principles and priorities for the park's management. This statement documents the key values, threats and management directions for the park. It is not a statutory document and a plan of management will still need to be prepared according to the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. Publication of a draft or final plan will replace the statements of management intent for the relevant parks covered.

What opportunities will the community have to comment?

The draft plan of management and planning considerations are on public exhibition until 28 September 2020 and anyone can provide comments.

When will the plan of management be finalised?

At the end of the public exhibition period in September 2020, National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) will review all submissions, prepare a submissions report and make any necessary changes to the draft plan of management. The West Regional Advisory Committee and the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council will then review the plan along with the submissions and report, as required by the National Parks and Wildlife Act.

Once their input has been considered and any further changes made to the plan of management, we provide the plan to the Minister for Energy and Environment. The plan of management is finalised when the Minister adopts the plan under the National Parks and Wildlife Act. Once a plan is adopted it is published on the Department's website.

How can I get more information about the draft plan?

For further information on the plan of management please contact the NPWS Park Management Planning Team at npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Where can I see a printed copy of the draft plan?

Hard copies are available for viewing at the following locations:

- National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) office, Camp Street, Forbes

- Condobolin Library, 130 Bathurst Street, Condobolin

How can I comment on the draft plan?

Public exhibition for the plan of management is from 26 June until 28 September 2020. You are invited to comment on the draft plan by sending a written submission during this time.

Your privacy

Your submission will be provided to a number of statutory advisory bodies (including the relevant regional advisory committee and the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council). Your comments on the draft plan may include 'personal information'. the Department complies with the NSW Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998 which regulates the collection, storage, access, amendment, use and disclosure of personal information. See our privacy webpage for details. Information that in some way identifies you may be gathered when you use our website or send us correspondence.

If an application to access information under the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 requests access to your submission, your views about release will be sought if you have indicated that you object to your submission being made public.

While all submissions count, they are most effective when we understand your ideas and the outcomes you want for park management. Some suggestions to help you write your submission are:

- Write clearly and be specific about the issues that are of concern to you.

- Note which part or section of the plan your comments relate to.

- Give reasoning in support of your points – this makes it easier for us to consider your ideas and will help avoid misinterpretation.

- Tell us specifically what you agree/disagree with and why you agree/disagree.

- Suggest solutions or alternatives to managing the issue if you can.

Have your say

Public exhibition is from 26 June 2020 to 28 September 2020.

You can provide your written submission in any of the following ways:

Post your written submission to:

Manager Planning Evaluation and Assessment

Locked Bag 5022

Parramatta NSW 2124

Email your submission to: npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Make a submission online by using the online form here

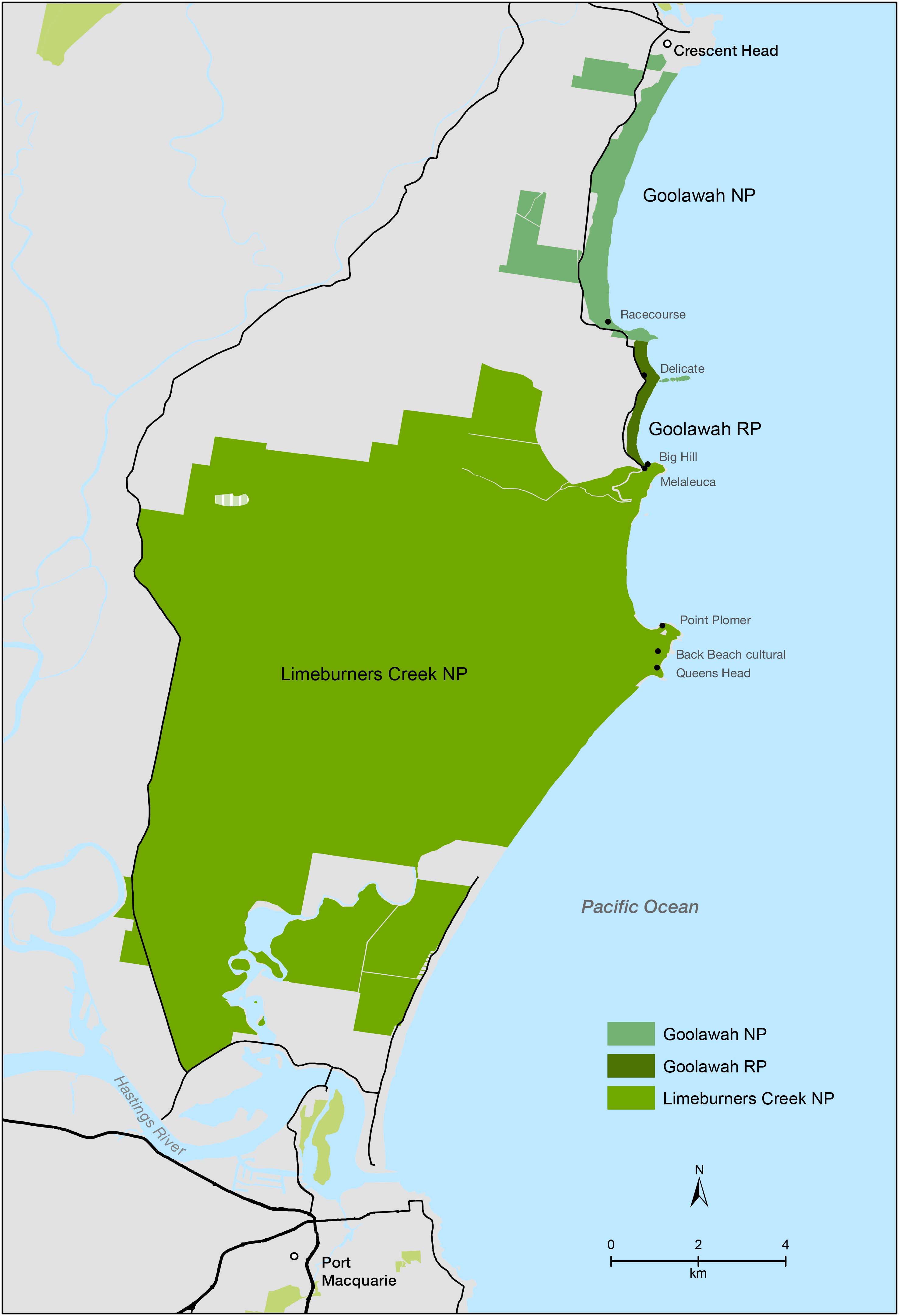

Limeburners Creek National Park, Goolawah National Park And Goolawah Regional Park: Public Consultation

Planning for the future –NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service is preparing a new plan of management for Limeburners Creek National Park, Goolawah National Park and Goolawah Regional Park.

These parks are in the traditional Country of the Dunghutti and Birpai Aboriginal Peoples. The parks play a fundamental role in the lives of local Aboriginal people, helping to maintain a tangible link to the past and enabling continued connections to Country.

The existing plan of management for Limeburners Creek National Park was written in 1998. The areas that are now Goolawah National Park and Goolawah Regional Park were formerly Goolawah State Park and Crown land. Initial community consultation about the Goolawah parks was undertaken in 2012, soon after they were transferred to National Parks and Wildlife Service.

Since this time large new areas have been added to the parks, including the intertidal zone on some of the beaches. There has also been a steady increase in visitors, and new recreational uses have become popular. Information about the values of the park has improved and new approaches to managing fire, pests and weeds have been developed.

Accommodating all of these visitors, maintaining the unique visitor experience and protecting the environment is challenging. Good planning is essential to manage increasing demand and provide sustainable visitor facilities and opportunities while minimising impacts and retaining the natural and low key nature of this beautiful stretch of coast. The development of a new combined plan of management will help to protect the parks' unique values and improve the effectiveness of how we manage the parks.

What opportunities will the community have to contribute to the development of a new plan of management?

Previous consultation, including a community forum, identified a range of issues important to the local community which will be considered in the new plan. It is now time to reach out and reconnect with our neighbours, stakeholders and local communities, as well as extending the invitation to the wider community of park users.

There are now 2 opportunities to be involved in the development of the plan of management for Goolawah Regional Park and Goolawah and Limeburners Creek national parks:

- During the development of the draft plan - register your interest below to receive updates and be notified of further consultation dates. Complete the form to provide your ideas on what you believe are the most important values of the parks and how they should be managed in the future. Your input will be used to draft a plan that reflects community values and aspirations.

- During public exhibition of the draft plan - there will be another opportunity to have your say when the draft plan of management is completed and put on public exhibition for 90 days. Anyone can submit comments on the draft plan during this time.

Register your interest

Complete the online form here to register your interest, provide initial input and be notified of further consultation dates. Tell us what is important to you about the parks and what you would like to see in the future. Comments close 30 October 2020.

Limeburners Creek National Park, Goolawah National Park and Goolawah Regional Park engagement map Photo: DPIE

Where are they now? The stories of the 119 species still in danger after the bushfires, and how to help

Anthea Batsakis, The Conversation; Nicole Hasham, The Conversation, and Wes Mountain, The ConversationThis article is part of Flora, Fauna, Fire, a special project by The Conversation that tracks the recovery of Australia’s native plants and animals after last summer’s bushfire tragedy. Explore the project here and read more articles here.

Before the summer bushfires destroyed vast expanses of habitat, Australia was already in the midst of a biodiversity crisis. Now, some threatened species have been reduced to a handful of individuals – and extinctions are a real possibility.

The Kangaroo Island dunnart, a small marsupial, was listed as critically endangered before the bushfires. Then the inferno destroyed 95% of its habitat.

Prospects for the Banksia Montana mealybug are similarly grim. This flightless insect lives only on one species of critically endangered plant, at a high altitude national park in Western Australia. The fires destroyed 100% of the plant’s habitat.

Read more: After the bushfires, we helped choose the animals and plants in most need. Here's how we did it

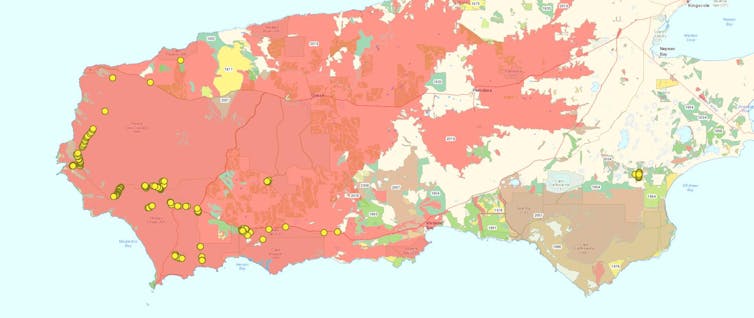

And fewer than 100 western ground parrots remained in the wild before last summer, on Western Australia’s south coast. Last summer’s fires destroyed 40% of its habitat.

Fish, crayfish and some frogs are also struggling. After the fires, heavy rain washed ash, fire retardants and dirt into waterways. This can clog and damage gills, and reduces the water’s oxygen levels. Some animals are thought to have suffocated.

Here, dozens of experts tell the stories of the 119 species most in need of help after our Black Summer.

How Can I Help?

Recovery from Australia’s bushfire catastrophe will be a long road. If you want to help, here are a few places to start.

Donate

Australian Wildlife Conservancy

Also see this list of registered bushfire charities

Volunteer

NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

Conservation Volunteers Australia

Anthea Batsakis, Deputy Editor: Environment + Energy, The Conversation; Nicole Hasham, Section Editor: Energy + Environment, The Conversation, and Wes Mountain, Multimedia Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our helicopter rescue may seem a lot of effort for a plain little bird, but it was worth it

This article is part of Flora, Fauna, Fire, a special project by The Conversation that tracks the recovery of Australia’s native plants and animals after last summer’s bushfire tragedy. Explore the project here and read more articles here.

As we stepped out of a military helicopter on Victoria’s east coast in February, smoke towered into the sky. We’d just flown over a blackened landscape extending as far as the eye could see. Now we were standing in an active fireground, and the stakes were high.

Emergency helicopter rescues aren’t usually part of a day’s work for conservation scientists. But for eastern bristlebirds, a potential disaster loomed.

Our mission was to catch 15-20 bristlebirds and evacuate them to Melbourne Zoo. This would provide an insurance population of this globally endangered species if their habitat was razed by the approaching fire.

As climate change grows ever worse, such rescues will be more common. Ours showed how it can be done.

The Plight Of The Eastern Bristlebird

Such a rescue may seem like a lot of effort for a small, plain brown bird. But eastern bristlebirds are important to Australia’s biodiversity.

They continue an ancient lineage of songbirds that dates back to the Gondwanan supercontinent millions of years ago. They’re reminders of wild places that used to exist, unchanged by humans.

Read more: Yes, the Australian bush is recovering from bushfires – but it may never be the same

These days, coastal development has shrunk the eastern bristlebird’s habitat. The birds are feeble flyers, and so populations die out when their habitat patches become too small.

Fewer than 2,500 individuals remain, spread across three locations on Australia’s east coast including a 400-strong population that straddles the Victoria-New South Wales border at Cape Howe. Losing them would be a huge blow to the species’ long term prospects.

A Rollercoaster Ride

On the day of our rescue, bushfires had been raging on Australia’s east coast for several months. The so-called Snowy complex fire that started in late December had razed parts of Mallacoota on New Year’s Eve then burnt into NSW. Now, more than a month later, that same fire had crossed back over the state border and was burning into Cape Howe.

Our 11-person field team had two chances over consecutive mornings. Using special nets, we caught nine eastern bristlebirds on one morning, and six the next. As we worked, burnt leaves caught in our nets – a tangible reminder of how close the fire was.

The captured birds were health-checked then whisked – first by 4WD, then boat and car – to a waiting flight to Melbourne. From there they were driven to special enclosures at Melbourne Zoo.

On the second day a wind change intensified the bushfire and cut short our time. As we evacuated under a darkening sky, it seemed unlikely Cape Howe would escape the flames.

In the ensuing days, the fire moved agonisingly close to the site until a favourable wind change spared it.

But tragedy struck days later when fire tore through eastern bristlebird habitat on the NSW side of Cape Howe. Many of the 250 individuals that lived there are presumed dead.

And despite the best efforts of vets and expert keepers at Melbourne Zoo, six of our captive birds succumbed to a fungal respiratory infection in the weeks after their arrival, which they were all likely carrying when captured.

Return To Cape Howe

Against the odds, bristlebird habitat on the Victorian side of Cape Howe remained unburnt. So in early April, we released a little flock of seven back into the wild.

We’d initially planned to attach tiny transmitters to some released bristlebirds to monitor how they settled back into their home. But COVID-19 restrictions forced us to cancel this intensive fieldwork.

Instead, each bristlebird was fitted with a uniquely coloured leg band. As restrictions ease, our team will return to Cape Howe to see how the colour-banded birds have fared.

A Model For The Future

The evacuation involved collaboration between government agencies and non-government organisations, with especially important coordination and oversight by Zoos Victoria, the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, and Parks Victoria.

This team moved mountains of logistical hurdles. A rescue mission that would ordinarily take more than a year to plan was completed in weeks.

Read more: After the bushfires, we helped choose the animals and plants in most need. Here's how we did it

So was it all worth it? We strongly believe the answer is yes. The team did what was needed for the worst-case scenario; ultimately that scenario was avoided by a mere whisker.

But climate change is heightening fire danger and increasing the frequency of extreme weather events. Soberingly, further emergency wildlife evacuations will probably be needed to prevent extinctions in future. Our mission will serve as a model for these interventions.

Rohan Clarke, Director, Monash Drone Discovery Platform, and Senior Lecturer in Ecology, Monash University; Katherine Selwood, Threatened Species Biologist, Wildlife Conservation & Science, Zoos Victoria and Honorary Research Fellow, Biosciences, University of Melbourne, and Rowan Mott, Biologist, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Summer bushfires: how are the plant and animal survivors 6 months on? We mapped their recovery

Anthea Batsakis, The Conversation; Nicole Hasham, The Conversation, and Wes Mountain, The ConversationAustralia roared into 2020 as a land on fire. The human and property loss was staggering, but the damage to nature was equally hard to fathom. By the end of the fire season 18.6 million hectares of land was destroyed.

So what’s become of animal and plant survivors in the months since?

Click through below to explore the impact Australia’s summer of fires had on an already drought-ravaged landscape and the work being done to rescue and recover habitats.

Anthea Batsakis, Deputy Editor: Environment + Energy, The Conversation; Nicole Hasham, Section Editor: Energy + Environment, The Conversation, and Wes Mountain, Multimedia Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

'Jewel of nature': scientists fight to save a glittering green bee after the summer fires

This article is part of Flora, Fauna, Fire, a special project by The Conversation that tracks the recovery of Australia’s native plants and animals after last summer’s bushfire tragedy. Explore the project here and read more articles here.

The green carpenter bee (Xylocopa aerata) is an iconic, beautiful native species described as a “jewel of nature” for its metallic green and gold colouring. Carpenter bees are so named because they excavate their own nests in wood, as opposed to using existing holes.

With a body length of about 2 centimetres, it is among the largest native bees in southern Australia. While not used in honey farming, it is an important pollinator for several species of Australian native plants.

Last summer’s catastrophic bushfires significantly increased the risk of local extinctions of this magnificent species. We have studied the green carpenter bee for decades. For example, after the 2007 fires on Kangaroo Island, we bolstered the remaining population by providing nesting materials.

To see our efforts - and more importantly, most of the habitat these bees rely on - destroyed by the 2020 fire was utterly devastating.

A Crucial Pollinator On The Brink

The green carpenter bee is a buzz-pollinating species. Buzz pollinators are specialist bees that vibrate the pollen out of the flowers of buzz-pollinated plants.

Many native plants, such as guinea flowers, velvet bushes, Senna, fringe, chocolate and flax lilies, rely completely on buzz-pollinating bees for seed production. Introduced honey bees do not pollinate these plants.

Read more: Our field cameras melted in the bushfires. When we opened them, the results were startling

The green carpenter bee went extinct on mainland South Australia in 1906 and in Victoria in 1938. It still occurs on the relatively uncleared western half of Kangaroo Island in South Australia, in conservation areas around Sydney, and in the Great Dividing Range in New South Wales.

Local extinctions were probably due to habitat clearing and large, intense bushfires. The last time the green carpenter bee was seen in Victoria was early December 1938 in the Grampians, which burnt completely during the Black Friday fires of January 1939.

There are several reasons green carpenter bees are vulnerable to fire, including:

- the species uses dead wood for nesting, which burns easily

- if the nest burns before the offspring matures in late summer, the adult female might fly away but won’t live long enough to reproduce again, and

- the bees need floral resources throughout the year.

Nowhere To Nest

The bees mainly dig their nests in two types of soft wood: dry flowering stalks of grass trees and, crucially important, large dead Banksia trunks. The availability of both nesting materials is intricately connected with fire.

Grass trees flower prolifically after fire, but the dry stalks are only abundant between two and five years after fire. Banksia species don’t survive fire, and need to grow for at least 30 years to become large enough for the bees to use.

With increasingly frequent and intense fires, there’s not enough time for Banksia trunks to grow big enough, before they’re wiped out by the next fire.

A Helping Hand After The 2007 Fires

In 2007, Flinders Chase National Park on Kangaroo Island burnt almost entirely.

However, in long-unburnt areas adjacent to the park, carpenter bee nests were still present. From there, they colonised the many dry grass tree stalks that resulted from the fire in the park.

In 2012, most flowering stalks had decayed. In an attempt to bolster population size, we successfully developed artificial nesting stalks to tide the bees over until new Banksia, suitable for nesting, would become available.