Inbox and Environment News Issue 459

July 26 - August 1, 2020: Issue 459

Proposal To Allow Off Leash Dogs On Pittwater's Ocean Beaches Tabled For Next Council Meeting

Those who have expressed disappointment that council is unable to respond to requests to stop the rise of unleashed dogs in our area and the subsequent dog attacks, children being rushed at by these and the environmental, wildlife and birdlife destruction that follows may be interested in what is submitted by Crs McTaggart, Ferguson and White for the coming council Meeting of Tuesday July 28, 2020, wherein they have tabled a Motion to have off-leash areas at North Palm Beach and South Mona Vale Beach, to begin with.

See: ITEM 14.3 NOTICE OF MOTION NO 33/2020 - ACTIVATION OF BEACH SPACE FOR DOG EXERCISE - Submitted by: Councillor Alex McTaggart, Ian White, and Kylie Ferguson

Community Warned To Beware Of Suspect Tree Operators

Council is warning the community to be wary of unscrupulous tree lopping operators who are again active on the Northern Beaches, flouting the law and making residents liable for thousands of dollars of fines for their illegal work.

CEO Ray Brownlee said Council is aware of rogue tree tradesmen recently in the Avalon area, offering to cheaply remove or trim large trees without Council permission. This follows a spate of similar incidents early in 2019 and also in 2017.

“Our community is passionate about trees and at Council we are committed to protecting as much of our tree canopy as possible,” Mr Brownlee said.

“Most trees over 5m high are protected and residents need Council approval to prune more than 10 percent of the tree or remove it. This ensures we maintain the green environment that is so valued by our community.

“Without consent to prune or remove the trees, residents can attract thousands of dollars in fines.

“If in doubt, residents should contact Council to ensure they, or those they contract, are working within the law.”

Mr Brownlee said that a good tree operator will be knowledgeable about what is permitted, be appropriately insured and qualified to undertake the work.

“If an operator can’t demonstrate they meet these requirements residents should think twice about employing them to do the job in case they end up being liable for their illegal activities.”

Property owners who are approached by contractors should contact Council first, to check that the work complies with Council’s tree controls or visit our website.

Residents can also contact NSW Department of Fair Trading on 13 32 20.

Please Help Sydney Wildlife Rescue: Donate Your Cans And Bottles And Nominate SW As Recipient

You can Help Sydney Wildlife help Wildlife. Sydney Wildlife Rescue is now listed as a charity partner on the return and earn machines in these locations:

- Pittwater RSL Mona Vale

- Northern Beaches Indoor Sports Centre NBISC Warriewood

- Woolworths Balgowlah

- Belrose Super centre

- Coles Manly Vale

- Westfield Warringah Mall

- Strathfield Council Carpark

- Paddy's Markets Flemington Homebush West

- Woolworths Homebush West

- Bondi Campbell pde behind Beach Pavilion

- Westfield Bondi Junction car park level 2 eastern end Woolworths side under ramp

- UNSW Kensington

- Enviro Pak McEvoy street Alexandria.

Every bottle, can, or eligible container that is returned could be 10c donated to Sydney Wildlife.

Every item returned will make a difference by removing these items from landfill and raising funds for our 100% volunteer wildlife carers. All funds raised go to support wildlife.

It is easy to DONATE, just feed the items into the machine select DONATE and choose Sydney Wildlife Rescue. The SW initiative runs until August 23rd.

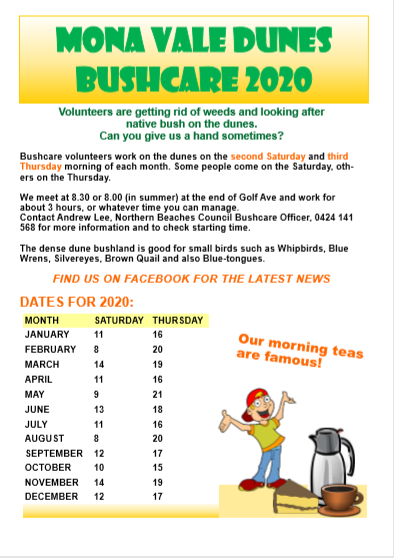

Tick Population Booming In Our Area

Residents from Terrey Hills and Belrose to Narrabeen and Palm Beach report a high number of ticks are still present in the landscape. Local Veterinarians are stating there has not been the usual break from ticks so far and each day they’re still getting cases, especially in treating family dogs.

To help protect yourself and your family, you should:

- Use a chemical repellent with DEET, permethrin or picaridin.

- Wear light-colored protective clothing.

- Tuck pant legs into socks.

- Avoid tick-infested areas.

- Check yourself, your children, and your pets daily for ticks and carefully remove any ticks using a freezing agent.

- If you have a reaction, contact your GP for advice.

Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park Precinct The Basin Closures Update

Many COVID-19 restrictions have now been lifted from visitor precincts and facilities In Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. However, several tracks and trails will remain closed while upgrades and remediation works are completed. These closures include:

- Bobbin Head playground

- Warrimoo walking track - public access may be restricted on Wednesday 17 and Thursday 18 June.

- The Basin trail

- The Basin campground and picnic area

- Mackerel service trail

- Salvation Loop and Wallaroo trails

Berowra track, between Apple Tree Bay and the intersection of Mount Ku-ring-gai track, has now reopened. However if you plan to visit, walk with caution as some sections of the track remain uneven.

Closed areas: The Basin campground, Basin trail and Mackerel service trail closed

The following areas will be closed from Monday 1 June until Monday 3 August 2020 while upgrade works and maintenance are underway:

- The Basin trail

- The Basin campground and picnic area

- Mackerel service trail

No public access is permitted. There will be no access to The Basin Aboriginal Engraving Site, Mackerel Beach to The Basin trail, West Head Road or The Basin campground.

For further information call 02 9451 3479 or 02 9472 8949.

EPA Orders Stop Work On Forestry Corporation Of NSW Operations In South Brooman State Forest

July 23, 2020

The NSW Environment Protection Authority has issued Forestry Corporation of NSW with a Stop Work Order to cease tree harvesting in part of South Brooman State Forest near Batemans Bay.

It is the second time in less than a week that a Stop Work Order has been issued to Forestry Corporation.

EPA Executive Director Regulatory Operations Carmen Dwyer said EPA investigations into operations in Compartment 58a of the forest had revealed serious alleged breaches of the rules that govern native forestry operations, in relation to the protection of trees that must be permanently retained.

“Officers allegedly found 26 hollow bearing trees that were either felled or damaged, with many of these trees also not identified and mapped in the planning phase.

“This area is known to be home to several threatened species that use hollow bearing trees. The Yellow-bellied Glider, the Glossy-Black Cockatoo and the Powerful, Masked and Sooty Owls are all listed as vulnerable species and may use hollow bearing trees for habitat,” Ms Dwyer said.

“The importance of identifying, mapping and protecting these vital trees is a key requirement and there should be proper processes in place to ensure compliance.”

After the recent Black Summer bushfires, the EPA imposed additional site-specific conditions on the existing strict environmental controls – called the Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval (IFOA) – to mitigate the specific environmental risks caused by the bushfires at each site, including impacts on plants, animals and their habitats, soils and waterways.

The site-specific conditions include the requirement to identify, map and permanently retain all trees with hollows, whether alive or dead.

As a result of the seriousness of the alleged breaches, the EPA has issued a Stop Work Order under the Biodiversity Conservation Act to stop Forestry Corporation logging in the relevant compartment. The order ensures that no further tree harvesting takes place in the area where the trees were felled for 40 days, or until the EPA is confident that Forestry Corporation can meet its obligations to comply with the IFOA including the site-specific conditions.

It follows a Stop Work Order issued for Wild Cattle Creek State Forest near Coffs Harbour on Saturday for felling two protected giant trees.

“This is the first Stop Work Order the EPA has issued for breaches of the site-specific conditions put in place for burnt forests and is necessary because failure to properly map and retain hollow bearing trees could result in irreparable environmental harm,” Ms Dwyer said.

The investigation into the matter is ongoing and non-compliance with the Coastal IFOA can attract a maximum penalty as high as $5 million.

Stop Work Orders and penalty notices are examples of a number of tools the EPA can use to achieve environmental compliance including formal warnings, official cautions, licence conditions, notices and directions and prosecutions. A recipient can appeal and elect to have the matter determined by a court.

For more information about the EPA’s regulatory tools, see the EPA Compliance Policy at www.epa.nsw.gov.au/legislation/prosguid.htm

EPA Orders Stop Work On Forestry Corporation Of NSW Operations In Wild Cattle Creek State Forest

July 18, 2020

The NSW Environment Protection Authority has today issued Forestry Corporation of NSW with a Stop Work Order to cease tree harvesting at Wild Cattle Creek State Forest inland from Coffs Harbour.

EPA Executive Director Regulatory Operations Carmen Dwyer said EPA investigations into operations in Compartments 32, 33 and 34 of the forest had revealed serious alleged breaches of the rules that govern native forestry operations, set out in the Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval (IFOA), in relation to the protection of trees that must not be felled.

“To maintain biodiversity in the forest, the Coastal IFOA rules require loggers to identify giant trees (over 140cm stump diameter) and ensure they are protected and not logged. The EPA alleges that during an inspection on 9 July 2020 EPA officers observed two giant trees which had been felled.

“Any trees except Blackbutt and Alpine Ash with a diameter of more than 140cm are defined as giant trees and must be retained under the Coastal IFOA,” Ms Dwyer said.

“As a result, the EPA has issued a Stop Work Order under the Biodiversity Conservation Act to stop Forestry Corporation logging in the forest. The order ensures that no further tree harvesting takes place in the area where the trees were felled for 40 days, or until the EPA is confident that Forestry Corporation can meet its obligations to comply with the Coastal IFOA conditions to protect giant trees.”

This is the first time the EPA has issued Forestry Corporation with a Stop Work Order under new laws which came into effect in 2018.

“These two old, giant trees have provided significant habitat and biodiversity value and are irreplaceable. Their removal points to serious failures in the planning and identification of trees that must be retained in the forest.

“These are serious allegations and strong action is required to prevent any further harm to giant or other protected trees which help maintain biodiversity and provide habitat for threatened species like koalas.”

This action follows the recent issue of two Penalty Notices totalling $2,200 to Forestry Corporation for non-compliances associated with an alleged failure to correctly identify protection zones for trees around streams and for felling four trees within those protected zones in Orara East State Forest near Coffs Harbour. The penalties were issued under previous rules when the penalties were lower.

“The EPA continues to closely monitor forestry operations despite the current COVID-19 restrictions, to ensure compliance with the regulations,” Ms Dwyer said.

“The community can be confident that any alleged non-compliance during forestry operations will be investigated by the EPA and action taken if the evidence confirms a breach.”

Stop Work Orders and penalty notices are examples of a number of tools the EPA can use to achieve environmental compliance including formal warnings, official cautions, licence conditions, notices and directions and prosecutions. A recipient can appeal and elect to have the matter determined by a court.

For more information about the EPA’s regulatory tools, see the EPA Compliance Policy at www.epa.nsw.gov.au/legislation/prosguid.htm

Professor Graeme Samuel AC Releases Interim Report For The Independent Review Of The Environment Protection And Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

July 20, 2020

Media statement from Professor Graeme Samuel AC: Release of Interim Report for the Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999

Today the Interim Report of the Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) has been released.

The Interim Report sets out preliminary views on the EPBC Act and how it operates. It focuses on the fundamental problems of the legislation and proposes reform directions that are needed to address these.

The Independent Reviewer, Professor Graeme Samuel AC, said “the Interim Report has been released part way through the Review as an opportunity to share and test thinking.

“The EPBC Act is ineffective. It does not enable the Commonwealth to protect and conserve environmental matters that are important for the nation. It is not fit to address current or future environmental challenges.

“The EPBC Act results in duplication with state and territory environment laws. The Commonwealth process for assessing and approving developments is slow, complex to navigate and costly for business. Slow and cumbersome regulation results in significant additional costs for business, with little appreciable benefit for the environment.”

Professor Samuel said “New, legally enforceable National Environmental Standards should be the centrepiece of reform—setting clear and concise rules that deliver outcomes for the environment and enable development to continue in a sustainable way.

“The development of National Environment Standards should be a priority reform measure. Interim Standards could be developed immediately, followed by an iterative development process as more sophisticated data becomes accessible. Standards should focus on detailed prescription of outcomes, not process.”

“National Environmental Standards will mean that the community and business can know what to expect. Standards support clear and consistent decisions, regardless of who makes them. Where states and territories can demonstrate their systems can deliver environmental outcomes consistent with the Standards, responsibilities should be devolved, providing faster and lower cost development assessments and approvals.”

“Community trust in the EPBC Act and its administration is low. To build confidence, the Interim Report proposes that an independent cop on the beat is required to deliver rigorous, transparent compliance and enforcement.”

Professor Samuel emphasised that “the EPBC Act had failed to fulfil its objectives as they relate to Indigenous Australians.

“Sustained engagement with Indigenous Australians is needed to properly co-design reforms that are important to them.

“Much more needs to be done to respectfully incorporate valuable Traditional Knowledge of Country in how the environment is managed.

“Indigenous Australians seek, and are entitled to expect, greater protection of their heritage,” Professor Samuel said.

“Extra effort is needed to invest in improving the condition of the environment. This means the EPBC Act needs a firmer focus on avoiding impacts where possible and increasing the area of nationally important habitats. This will allow future development to be sustainable.

Given contested views of how Australia can best achieve ecologically sustainable development, Professor Samuel said it is “unlikely that everyone will agree on all the issues identified in the Interim Report or support all the proposed reform directions.

“The Review encourages consideration of the overall reform direction proposed, rather than its component parts,” Professor Samuel said.

“The proposed reforms seek to build community trust that Australia’s national environmental laws are delivering effective environment and heritage protection, while regulating businesses efficiently.

“The proposed reforms enable the Commonwealth to show national leadership, while working more closely with the states and territories to deliver a joined-up approach to environmental management.

“Reform of the EPBC Act is well overdue and necessary to ensure current and future generations can enjoy Australia’s unique environment and iconic places.” Professor Samuel said.

Next steps in the Review

All Australians are invited to have a say about the reform directions in the Interim Report. To read the Interim Report and have your say visit the website epbcactreview.environment.gov.au.

Professor Samuel now intends to engage in targeted consultations with stakeholders. throughout July, August and September. These consultations will focus on progressing the key reform directions proposed in the Interim Report, including refining the National Environmental Standards.

Professor Samuel intends to convene collaborative discussions with environment, indigenous, agriculture and business groups, and leading academics. These discussions will involve stakeholders who had provided substantive contributions to the Review and have indicated a willingness to collaborate to shape a reform pathway. Consultation with state and territory governments will also be undertaken.

Professor Samuel’s Final Report, including recommendations to government, is due to be delivered to the Minister for the Environment by 31 October 2020.

Proposed key reform directions

- The Commonwealth should continue to focus on existing areas of responsibility with no expansion to regulate new environmental matters.

- New, legally enforceable National Environmental Standards should be established to deliver ecologically sustainable development. Focused on outcomes rather than process.

- Streamlining and greater efficiency through devolution in a way that provides community confidence, with National Environmental Standards as the foundation to set the outcomes needed regardless of who the decision maker is.

- Strong and transparent assurance to ensure devolved decisions deliver the intended outcomes.

- Australia’s Indigenous cultural heritage laws need to be reviewed and more work is needed to support better engagement with Indigenous Australians and to respectfully incorporate Traditional Knowledge of Country in how the environment is managed.

- Build trust in the system through increased transparency of information and decision-making to reduce the need to resort to court processes to discover information. Legal challenges should be limited to matters of outcome, not process.

- A quantum shift in the quality of information is needed, so that the right information is available at the right time for the community, proponents and decision-makers. This will deliver better decisions, and faster and lower cost assessments and approvals.

- A coherent framework to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of the EPBC Act is needed, including revamped State of the Environment reporting.

- Restoration of the environment must be a focus. Available habitat needs to grow to be able to support both development and a healthy environment. Explore ways to accelerate environmental restoration such as markets and co-investing with the philanthropic and private sectors.

- An independent compliance and enforcement regulator that is not subject to actual or implied political direction. It should be properly resourced and have a full toolkit of powers.

Reform For Australia's Environment Laws

July 20, 2020

Minister for the Environment Sussan Ley will prioritise the development of new national environmental standards, further streamlining approval processes with State governments and national engagement on indigenous cultural heritage, following the release of an interim report into Australia’s environmental laws.

Professor Graeme Samuel’s interim report established that the existing Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 has become cumbersome and does not serve the interests of the environment or business.

“Not surprisingly, the statutory review is finding that 20-year-old legislation is struggling to meet the changing needs of the environment, agriculture, community planners and business,” Minister Ley said.

“This is our chance to ensure the right protection for our environment while also unlocking job-creating projects to strengthen our economy and improve the livelihoods of every-day Australians. We can do both as part of the Australian Government’s COVID recovery plan.

The Commonwealth will commit to the following priority areas on the basis of the interim report:

- Develop Commonwealth led national environmental standards which will underpin new bilateral agreements with State Governments.

- Commence discussions with willing states to enter agreements for single touch approvals (removing duplication by accrediting states to carry out environmental assessments and approvals on the Commonwealth’s behalf).

- Commence a national engagement process for modernising the protection of indigenous cultural heritage, commencing with a round table meeting of state indigenous and environment ministers. This will be jointly chaired by Minister Ley and the Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt.

- Explore market based solutions for better habitat restoration that will significantly improve environmental outcomes while providing greater certainty for business. The Minister will establish an environmental markets expert advisory group.

In line with the interim report findings, the Commonwealth will maintain its existing framework for regulating greenhouse gas and other emissions, and would not propose any expansion of the EPBC Act in this area.

The Commonwealth will take steps to strengthen compliance functions and ensure that all bilateral agreements with States and Territories are subject to rigorous assurance monitoring.

It will not, however, support additional layers of bureaucracy such as the establishment of an independent regulator.

The report raises a range of other issues and reform directions. Further consultation will be undertaken regarding these.

“I thank Professor Samuel for his work and for his very clear message that we need to act,” Minister Ley said.

“As he works towards his final report, we will monitor its progress closely, while we continue to improve existing processes as much as possible.

“It is time to find a way past an adversarial approach and work together to create genuine reform that will protect our environment, while keeping our economy strong.”

Link to Interim Report: https://epbcactreview.environment.gov.au

Environment Minister Sussan Ley is in a tearing hurry to embrace nature law reform – and that's a worry

The Morrison government on Monday released a long-awaited interim review into Australia’s federal environment law. The ten-year review found Australia’s natural environment is declining and under increasing threat. The current environmental trajectory is “unsustainable” and the law “ineffective”.

The report, by businessman Graeme Samuel, called for fundamental reform of the law, know as the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. The Act, Samuel says:

[…] does not enable the Commonwealth to play its role in protecting and conserving environmental matters that are important for the nation. It is not fit to address current or future environmental challenges.

Samuel confirmed the health of Australia’s environment is in dire straits, and proposes many good ways to address this.

Worryingly though, Environment Minister Sussan Ley immediately seized on proposed reforms that seem to suit her government’s agenda – notably, streamlining the environmental approvals process – and will start working towards them. This is before the review has been finalised, and before public comment on the draft has been received.

This rushed response is very concerning. I was a federal environment official for 13 years, and from 2007 to 2012 was responsible for administering and reforming the Act. I know the huge undertaking involved in reform of the scale Samuel suggests. The stakes are far too high to risk squandering this once-a-decade reform opportunity for quick wins.

‘Fundamental Reform’ Needed: Samuel

The EPBC Act is designed to protect and conserve Australia’s most important environmental and heritage assets – most commonly, threatened plant and animal species.

Samuel’s diagnosis is on the money: the current trajectory of environmental decline is clearly unsustainable. And reform is long overdue – although unlike Samuel, I would put the blame less on the Act itself and more on government failings, such as a badly under-resourced federal environment department.

Samuel also hits the sweet spot in terms of a solution, at least in principle. National environmental standards, legally binding on the states and others, would switch the focus from the development approvals process to environmental outcomes. In essence, the Commonwealth would regulate the states for environmental results, rather than proponents for (mostly) process.

Read more: A major scorecard gives the health of Australia's environment less than 1 out of 10

Samuel’s recommendation for a quantum shift to a “single source of truth” for environmental data and information is also welcome. Effective administration of the Act requires good information, but this has proven hard to deliver. For example the much-needed National Plan for Environmental Information, established in 2010, was never properly resourced and later abolished.

Importantly, Samuel also called for a new standard for “best practice Indigenous engagement”, ensuring traditional knowledge and views are fully valued in decision-making. The lack of protection of Indigenous cultural assets has been under scrutiny of late following Rio Tinto’s destruction of the ancient Indigenous site Juukan caves. Reform in this area is long overdue.

And notably, Samuel says environmental restoration is required to enable future development to be sustainable. Habitat, he says “needs to grow to be able to support both development and a healthy environment”.

Streamlined Approvals

Samuel pointed to duplication between the EPBC Act and state and territory regulations. He said efforts have been made to streamline these laws but they “have not gone far enough”. The result, he says, is “slow and cumbersome regulation” resulting in significant costs for business, with little environmental benefit.

This finding would have been music to the ears of the Morrison government. From the outset, the government framed Samuel’s review around a narrative of cutting the “green tape” that it believed unnecessarily held up development.

In June the government announced fast-tracked approvals for 15 major infrastructure projects in response to the COVID-19 economic slowdown. And on Monday, Ley indicated the government will prioritise the new national environmental standards, including further streamlining approval processes.

Read more: Environment laws have failed to tackle the extinction emergency. Here's the proof

Here’s where the danger lies. The government wants to introduce legislation in August. Ley said “prototype” environmental standards proposed by Samuel will be introduced at the same time. This is well before Samuel’s final report, due in October.

I believe this timeframe is unwise, and wildly ambitious.

Even though Samuel proposes a two-stage process, with interim standards as the first step, these initial standards risk being too vague. And once they’re in place, states may resist moving to a stricter second stage.

To take one example, the prototype standards in Samuel’s report say approved development projects must not have unacceptable impacts on on matters of national environmental significance. He says more work is needed on the definition of “unacceptable”, adding this requires “granular and specific guidance”.

I believe this requires standards being tailored to different ecosystems across our wide and diverse landscapes, and being specific enough to usefully guide the assessment of any given project. This is an enormous task which cannot be rushed. And if Samuel’s prototype were adopted on an interim basis, states would be free, within some limits, to decide what is “unacceptable”.

It’s also worth noting that the national standards model will need significant financial resources. Samuel’s model would see the Commonwealth doing fewer individual project approvals and less on-ground compliance. However, it would enter a new and complex world of developing environmental standards.

More Haste, Less Speed

Samuel’s interim report will go out for public comment before the final report is delivered in October. Ley concedes further consultation is needed on some issues. But in other areas, the government is not willing to wait. After years of substantive policy inaction it seems the government wants to set a new land-speed record for environmental reform.

The government’s fixation with cutting “green tape” should not unduly colour its reform direction. By rushing efforts to streamline approvals, the government risks creating a jumbled process with, once again, poor environmental outcomes.![]()

Peter Burnett, Honorary Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

National cabinet just agreed to big changes to environment law. Here's why the process shouldn't be rushed

Federal and state governments on Friday resolved to streamline environment approvals and fast-track 15 major projects to help stimulate Australia’s pandemic-stricken economy.

The move follows the release this week of Professor Graeme Samuel’s preliminary review of the law, the 20-year-old Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. Samuel described the law as “ineffective” and “inefficient” and called for wholesale reform.

At the centrepiece of Samuel’s recommendations are “national environmental standards” that are consistent and legally enforceable, and set clear rules for decision-making. Samuel provides a set of “prototype” standards as a starting point. He recommends replacing the prototypes with more refined standards over time.

By the end of August, the Morrison government wants Parliament to consider implementing the prototype standards.

But rushing in the new law is a huge concern, and further threatens the future of Australia’s irreplaceable natural and cultural heritage. Here, we explain why.

Semantics Matter

Samuel’s review said legally enforceable national standards would help ensure development is sustainable over the long term, and reduce the time it takes to have development proposals assessed.

We’ve identified a number of problems with his prototype standards.

First, they introduce new terms that will require interpretation by decision-makers, which could lead the government into the courts. This occurred in Queensland’s Nathan dam case when conservation groups successfully argued the term environmental “impacts” should extend to “indirect effects” of development.

Second, there’s a difference in wording between the prototype standards and the EPBC Act itself, which might lead to uncertainty and delay. Samuel suggested a “no net loss” national standard for vulnerable and endangered species habitat, and “net gain” for critically endangered species habitat. But this departs from current federal policy, under which environmental offsets must “improve or maintain” the environmental outcome compared to “what is likely to have occurred under the status quo”.

Third, the outcomes proposed under the prototype standards might themselves cause confusion. The standards say, overall, the environment should be “protected”, but rare wetlands protected under the Ramsar Convention should be “maintained”. The status of threatened species should “improve over time” and Commonwealth marine waters should be “maintained or enhanced”, but the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park needs to be “sustained for current and future generations”.

And fourth, the standards don’t rule out development in habitat critical to threatened species, but require that “no detrimental change” occurs. But in reality, can there be development in critical habitat without detrimental change?

Mind The Gap

The escape clause in the prototype standards presents another problem. A small, yet critical recommendation in the appendix of Samuel’s report says:

These amendments should include a requirement that the Standards be applied unless the decision-maker can demonstrate that the public interest and the national interest is best served otherwise.

Which decision maker is he referring to here – federal or state? If it’s the former, will there be a constant stream of requests to the federal environment minister for a “public interest” exemption on the basis of jobs and economic development? If the latter, can a state decision-maker judge the “national interest”, especially for species found in several states, such as the koala?

Samuel says the “legally enforceable” nature of national standards are the foundation of effective regulation. But both he and Auditor-General Grant Hehir in his recent report found existing enforcement provisions are rarely applied, and penalties are low.

Federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley has already ruled out Samuel’s recommendation that an independent regulator take responsibility for enforcement. But the record to date does not give confidence that government officials will enforce the standards.

Temporary Forever?

Both Ley and Samuel suggested the interim standards would be temporary and updated later. But history shows “draft” and “interim” policies have a tendency to become long-term, or permanent.

For example, federal authorities often allow a proponent to cause environmental damage, and compensate by improving the environment elsewhere - a process known as “offsetting”. A so-called “draft” offset policy drawn up in 2007 actually remained in place for five years until 2012, when it was finally replaced. And the federal environment department recently accepted offsets based on the 2007 “draft” rather than the current policy.

The best antidote is to ensure the first tranche of national standards is comprehensive, precise and strong. This can only occur if genuine consultation occurs, legislation is not rushed, and the government commits to improving the “antiquated” data and information systems the standards rely on.

Negotiation To The Lowest Bar

According to the Samuel report, the proposed standards “provide a clear pathway for greater devolution in decision-making” that will enable states and territories to conduct federal environmental assessments and approvals. This proposed change has been strongly and consistently criticised by scientists and environmental lawyers.

Ley also appears to be wildly underestimating the time and effort required to negotiate the standards with the states and territories.

Take the Gillard government’s attempts to overcome duplication between state and federal law by establishing a “one-stop-shop” approvals process. Prime Minister Julia Gillard pulled the plug on negotiations after a year, declaring the myriad agreements being sought by various states was the “regulatory equivalent of a Dalmatian dog”.

The Abbott government’s negotiations for a similar policy lasted twice as long but suffered a similar fate, lapsing with the dissolution of Parliament in 2016.

Samuel warned refining the standards should not involve “negotiated agreement with rules set at the lowest bar”. But vested interests will inevitably seek to influence the process.

Proceed With Caution

We have identified significant problems with the prototype standards, and more may emerge.

Ley’s rush to amend the Act appears motivated more by wanting to cut so-called “green tape” than by evidence or environmental outcomes.

Prototypes are meant to be stress-tested. But if the defects are not corrected before hurrying into negotiations and legislative change, Australia might go another 20 years without effective environment laws.

Update: This article has been amended to reflect the national cabinet decision.

Read more: Environment laws have failed to tackle the extinction emergency. Here's the proof ![]()

Megan C Evans, Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW and Peter Burnett, Honorary Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

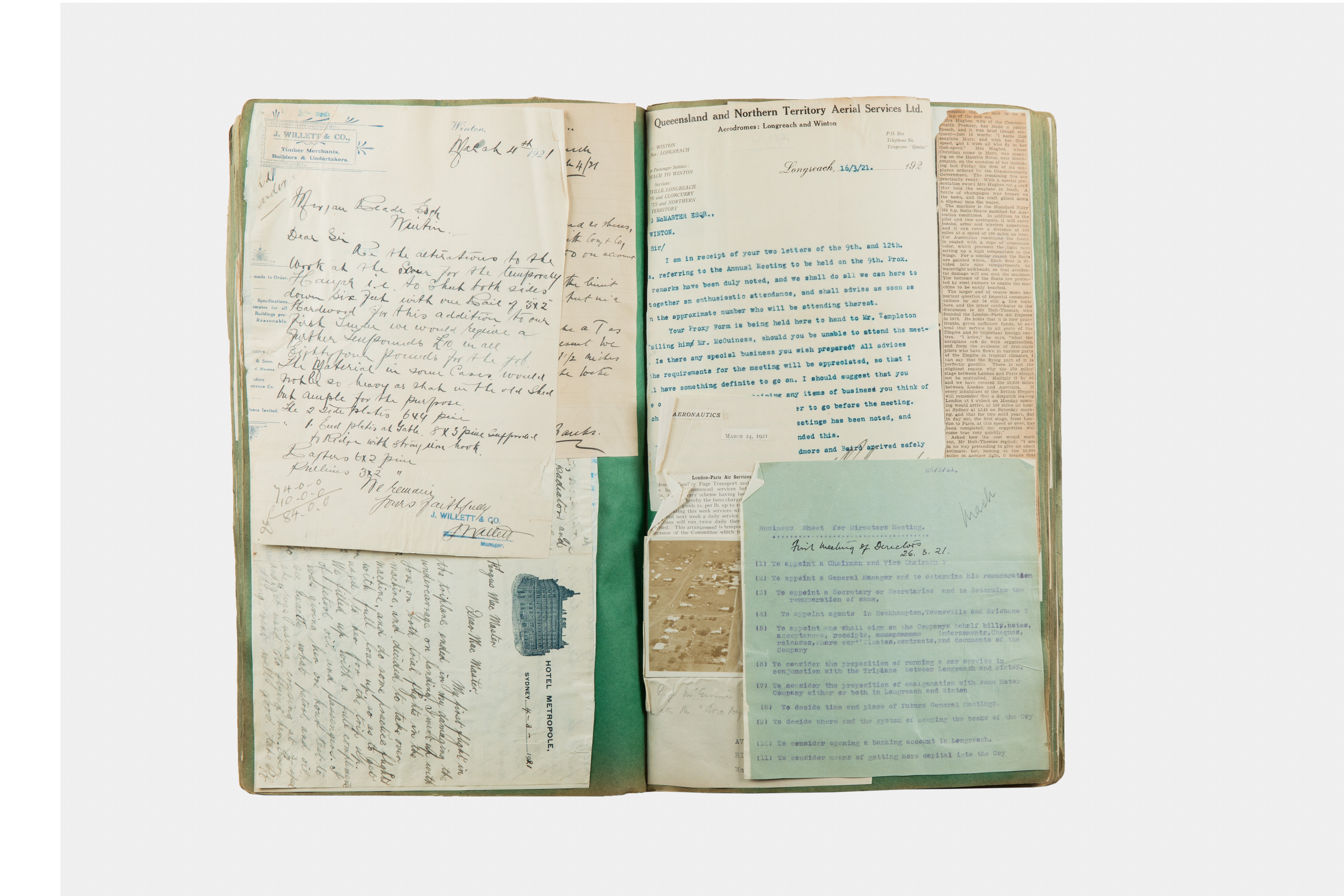

New research reveals how Australia and other nations play politics with World Heritage sites

Some places are considered so special they’re valuable to all humanity and must be preserved for future generations. These irreplaceable gems – such as Machu Picchu, Stonehenge, Yosemite National Park and the Great Barrier Reef – are known as World Heritage sites.

When these places are threatened, they can officially be placed on the “List of World Heritage in Danger”. This action brings global attention to the natural or human causes of the threats. It can encourage emergency conservation action and mobilise international assistance.

However, our research released today shows the process of In Danger listings is being manipulated for political gain. National governments and other groups try to keep sites off the list, with strategies such as lobbying, or partial efforts to protect a site. Australian government actions to keep the Great Barrier Reef off the list are a prime example.

These practices are a problem for many reasons – not least because they enable further damage to threatened ecosystems.

What Is The In Danger List?

World Heritage sites represent outstanding socioeconomic, natural and cultural values. Nations vie to have their sites included on the World Heritage list, which can attract tourist dollars and international prestige. In return, the nations are responsible for protecting the sites.

World Heritage sites are protected by an international convention, overseen by the United Nations body UNESCO and its World Heritage Committee. The committee consists of representatives from 21 of the 193 nations signed up to the convention.

Read more: We just spent two weeks surveying the Great Barrier Reef. What we saw was an utter tragedy

When a site comes under threat, the World Heritage Committee can list the site as in danger of losing its heritage status. In 2014 for example, the committee threatened to list the Great Barrier Reef as In Danger – in part due to a plan to dump dredged sediment from a port development near the reef, as well as poor water quality, climate change and other threats. This listing did not eventuate.

An In Danger listing can attract help to protect a site. For example, the Galápagos Islands were placed on the list in 2007. The World Heritage Fund provided the Ecuadorian government with technical and financial assistance to restore the site’s World Heritage status. The work is not yet complete, but the islands were removed from the In Danger list in 2010.

Political Games

Our study shows political manipulation appears to be compromising the process that determines if a site is listed as In Danger.

We examined interactions between UNESCO and 102 national governments, from 1972 until 2019. We interviewed experts from the World Heritage Committee, government agencies and elsewhere, and combined this with global site threat data, UNESCO and government records, and economic and governance data.

We found at least 41 World Heritage sites, including the Great Barrier Reef, were at least once considered by the World Heritage Committee for the In Danger list, but weren’t put on it. This is despite these sites being reported by UNESCO as threatened, or more threatened, than those already on the In Danger list. And 27 of the 41 sites were considered for an In Danger listing more than once.

The number of sites on the In Danger list declined by 31.6% between 2001 and 2008, and has plateaued since. By 2019, only 16 of 238 ecosystems were certified as In Danger. In contrast, the number of ecosystems on the World Heritage list has increased steadily over the past 20 years.

Read more: Explainer: what is the List of World Heritage in Danger?

So why is this happening? Our analysis showed the threat of an In Danger listing drives a range of government responses.

This includes governments complying only partially with World Heritage Committee recommendations or making only symbolic commitments. Such “rhetorical” adoption of recommendations has been seen in relation to the Three Parallel Rivers in China’s Yunnan province, the Western Caucasus in Russia and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef (explored in more detail below).

In other cases, threats to a site are high but attract limited attention and effort from either the national government or UNESCO. These sites include Halong Bay in Vietnam and the remote Tubbataha Reefs in the Philippines.

A 2004 amendment to the way the World Heritage Committee assesses In Danger listings means sites can be “considered” for inclusion rather than just listed, retained or removed. This has allowed governments to use delay tactics, such as in the case of Cameroon’s Dja Faunal Reserve. It has been considered for the In Danger list five times since 2011, but never listed.

Case In Point: The Great Barrier Reef

In 2014 and 2015, the Australian government spent more than A$400,000 on overseas lobbying trips to keep the Great Barrier Reef off the In Danger list. The environment minister and senior bureaucrats travelled to most of the 21 countries on the committee, plus other nations, to argue against the listing. The mining industry also contributed to the lobbying effort.

The World Heritage Committee had asked Australia to develop a long-term plan to protect the reef. The Australian and Queensland governments appeared to comply, by releasing the Reef 2050 Plan in 2015.

But in 2018, a national audit and Senate inquiry found a substantial portion of finance for the plan was delivered – in a non-competitive and hidden process – to the private Great Barrier Reef Foundation, which had limited capacity and expertise. This casts doubt over whether the aims of the reef plan can be achieved.

Real World Damage

Our study makes no recommendation on which World Heritage sites should be listed as In Danger. But it uncovered political manipulation that has real-world consequences. Had the Great Barrier Reef been listed as In Danger, for example, developments potentially harmful to the reef, such as the Adani coal mine, may have struggled to get approval.

Last year, an outlook report gave the reef a “very poor” prognosis and last summer the reef suffered its third mass bleaching in five years. There are grave concerns for the ecosystem’s ability to recover before yet another bleaching event.

Political manipulation of the World Heritage process undermines the usefulness of the In Danger list as a policy tool. Given the global investment in World Heritage over the past 50 years, it is essential to address the hidden threats to good governance and to safeguard all ecosystems.

Read more: Australia reprieved – now it must prove it can care for the Reef ![]()

Tiffany Morrison, Professorial Research Fellow, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University; Katrina Brown, Professor of Social Sciences, University of Exeter; Maria Lemos, Professor of Environmental Justice, Environmental Policy and Planning, Climate + Energy,, University of Michigan, and Neil Adger, Professor of Human Geography, University of Exeter

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

M1 Rubble Reused On Central Coast Fire Trails

July 20 2020

More than 30,000 tonnes of rubble that was once part of the M1 Pacific Motorway has been used to rebuild fire trails across the Central Coast – and there are plans to roll out the initiative statewide.

Minister for Regional Transport and Roads Paul Toole said Transport for NSW had partnered with Central Coast Council to donate excess rubble and rocks from the upgrade to help reinforce council’s fire trail network, saving money and time for both parties.

“This truly was a win-win situation because Transport for NSW saved on transportation and processing costs, while Central Coast Council tripled its fire trail reinforcement program at no extra cost,” Mr Toole said.

“Hundreds of local homes are still standing because fire fighters were able to hold back the inferno that swept through the area on New Year’s Eve while standing on a reinforced trail.

“The huge success of this project means the initiative could be used right across the state, so that we can forge ahead with vital infrastructure projects while doing our bit for the environment and local communities.”

Parliamentary Secretary for the Central Coast and Member for Terrigal Adam Crouch praised Transport for NSW and Central Coast Council for their role in helping local Rural Fire Service brigades save homes during the bushfires.

“In the past three years, Central Coast Council has been using excess material provided at no cost by Transport for NSW for fire trail construction on existing road reserves,” Mr Crouch said.

“Rural Fire Service volunteers were truly heroic in their successful efforts to save homes and lives here on Arizona Road in Charmhaven, but the reinforcement of this trail in the months beforehand played a key role in that outcome.”

Rural Fire Service Superintendent Viki Campbell said the strength of the upgraded trails gave local brigades a firm foundation for holding back the fire that swept through on New Year’s Eve.

“Fire trails play a very important role in accessing fires and bringing them under control,” Superintendent Campbell said.

“Last fire season, the local network of trails assisted firefighters in protecting hundreds of homes in the area.”

Central Coast Council Environmental Unit Manager Luke Sulkowski said the program increased capacity to maintain the local fire trail network.

“This saving on material supply has meant Central Coast Council has completed about three times the quantity of improvements we would have normally achieved within our budget,” Mr Sulkowski said.

“Rough estimates on cost savings over three years would be $930,000 for material and about $500,000 for rock reuse.”

For more information on the M1 Pacific Motorway Upgrades, go to M1 Pacific Motorway.

Fish Reef Domes A Boon For Environment And Recreational Fishing In New South Wales Estuaries

An amazing site to see - a very large school of yellowtail kingfish spiral around the towers of the Sydney offshore recreational fishing reef in March 2014.

Video by NSW DPI Fisheries

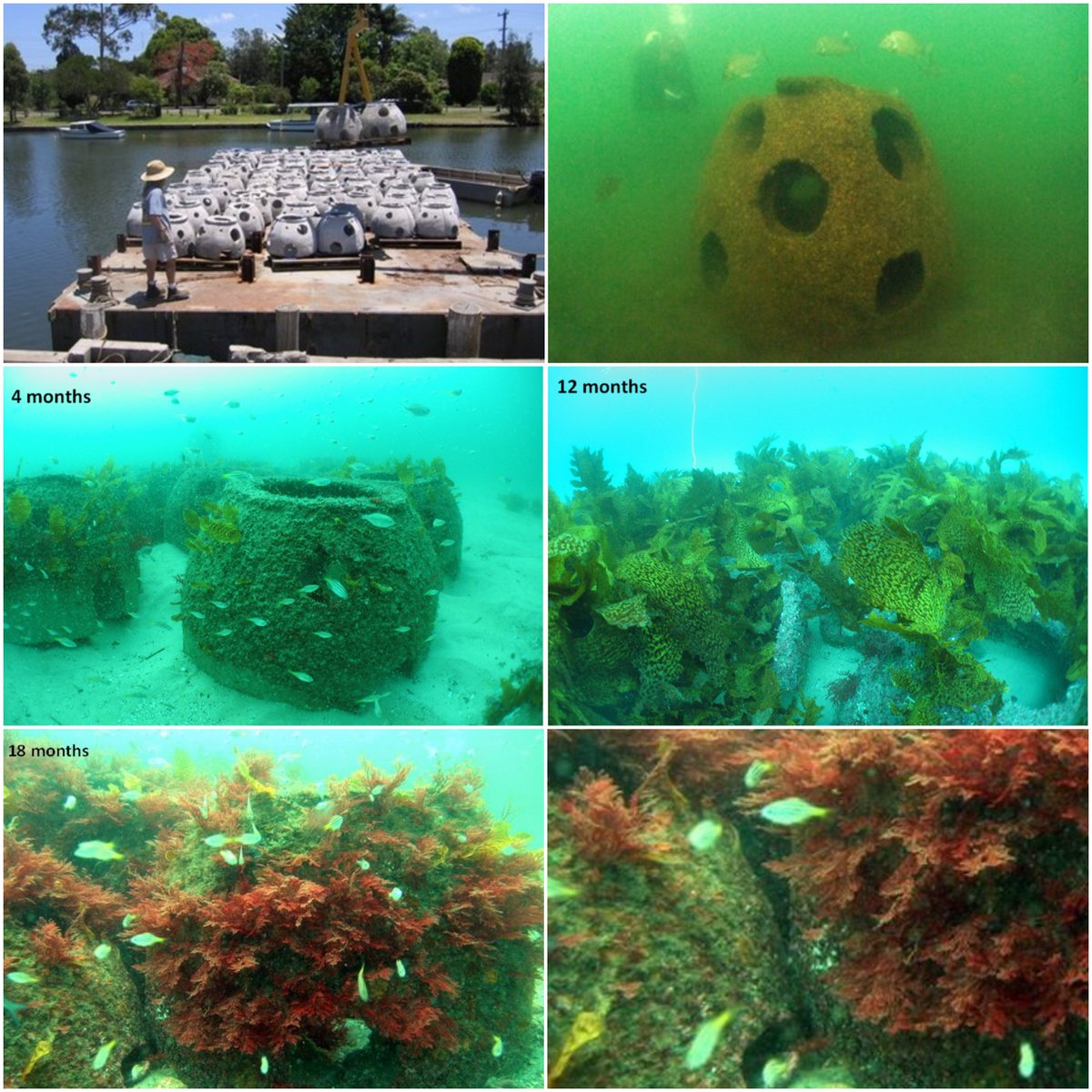

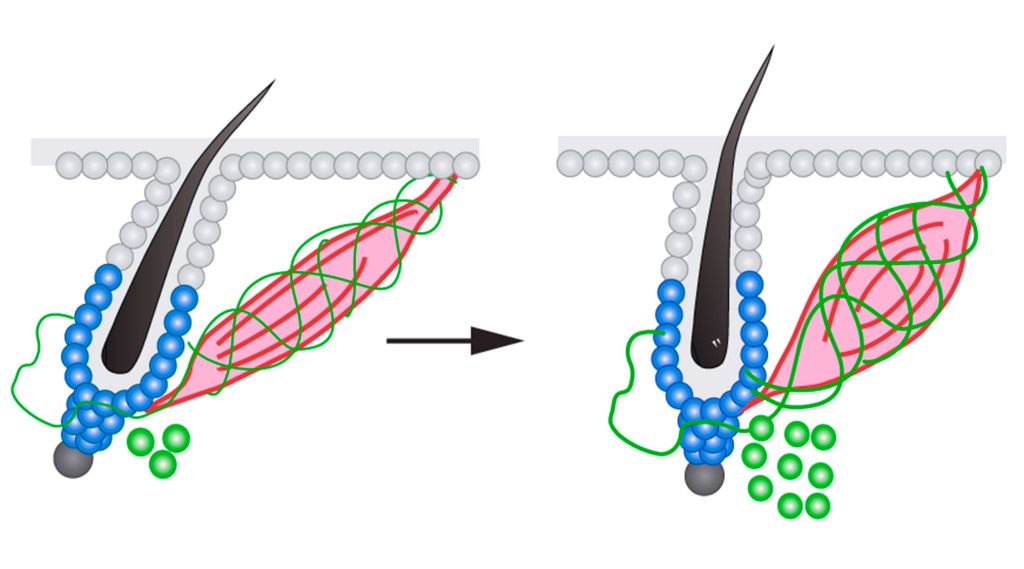

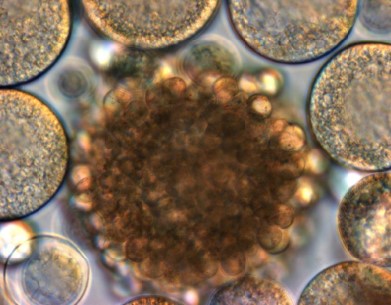

In a boost for both recreational fishing and the environment, new UNSW research shows that artificial reefs can increase fish abundance in estuaries with little natural reef.

Researchers installed six humanmade reefs per estuary studied and found overall fish abundance increased up to 20 times in each reef across a two-year period.

The study, published in the Journal of Applied Ecology recently, was funded by the NSW Recreational Fishing Trust.

The research was a collaboration between UNSW Sydney, NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) Fisheries and the Sydney Institute of Marine Science (SIMS).

Professor Iain Suthers, of UNSW and SIMS, led the research, while UNSW alumnus Dr Heath Folpp, of NSW DPI Fisheries, was lead author.

Co-author Dr Hayden Schilling, SIMS researcher and Conjoint Associate Lecturer at UNSW, said the study was part of a larger investigation into the use of artificial reefs for recreational fisheries improvement in estuaries along Australia's southeast coast.

"Lake Macquarie, Botany Bay and St Georges Basin were chosen to install the artificial reefs because they had commercial fishing removed in 2002 and are designated specifically as recreational fishing havens," Dr Schilling said.

"Also, these estuaries don't have much natural reef because they are created from sand. So, we wanted to find out what would happen to fish abundance if we installed new reef habitat on bare sand.

"Previous research has been inconclusive about whether artificial reefs increased the amount of fish in an area, or if they simply attracted fish from other areas nearby."

Fish reef domes boost abundance

In each estuary, the scientists installed 180 "Mini-Bay Reef Balls" -- commercially made concrete domes with holes -- divided into six artificial reefs with 30 units each.

Each unit measures 0.7m in diameter and is 0.5m tall, and rests on top of bare sand.

Professor Suthers said artificial reefs were becoming more common around the world and many were tailored to specific locations.

Since the study was completed, many more larger units -- up to 1.5m in diameter -- have been installed in NSW estuaries.

"Fish find the reef balls attractive compared to the bare sand: the holes provide protection for fish and help with water flowing around the reefs," Prof Suthers said.

"We monitored fish populations for about three months before installing the reefs and then we monitored each reef one year and then two years afterwards.

"We also monitored three representative natural reef control sites in each estuary."

Prof. Suthers said the researchers observed a wide variety of fish using the artificial reefs.

"But the ones we were specifically monitoring for were the species popular with recreational fishermen: snapper, bream and tarwhine," he said.

"These species increased up to five times and, compared to the bare sand habitat before the reefs were installed, we found up to 20 times more fish overall in those locations.

"What was really exciting was to see that on the nearby natural reefs, fish abundance went up two to five times overall."

Photo: UNSW Science

Dr Schilling said that importantly, their study found no evidence that fish had been attracted from neighbouring natural reefs to the artificial reefs.

"There was no evidence of declines in abundance at nearby natural reefs. To the contrary, we found abundance increased in the natural reefs and at the reef balls, suggesting that fish numbers were actually increasing in the estuary overall," he said.

"The artificial reefs create ideal rocky habitat for juveniles -- so, the fish reproduce in the ocean and then the juveniles come into the estuaries, where there is now more habitat than there used to be, enabling more fish to survive."

The researchers acknowledged, however, that while the artificial reefs had an overall positive influence on fish abundance in estuaries with limited natural reef, there might also be species-specific effects.

For example, they cited research on yellowfin bream which showed the species favoured artificial reefs while also foraging in nearby seagrass beds in Lake Macquarie, one of the estuaries in the current study.

NSW DPI Fisheries conducted an impact assessment prior to installation to account for potential issues with using artificial reefs, including the possibility of attracting non-native species or removing soft substrate.

Artificial reef project validated

Dr Schilling said their findings provided strong evidence that purpose-built artificial reefs could be used in conjunction with the restoration or protection of existing natural habitat to increase fish abundance, for the benefit of recreational fishing and estuarine restoration of urbanised estuaries.

"Our results validate NSW Fisheries' artificial reef program to enhance recreational fishing, which includes artificial reefs in estuarine and offshore locations," he said.

"The artificial reefs in our study became permanent and NSW Fisheries rolled out many more in the years since we completed the study.

"About 90 per cent of the artificial reefs are still sitting there and we now have an Honours student researching the reefs' 10-year impact." Dr Schilling said the artificial reefs were installed between 2005 and 2007, but the research was only peer-reviewed recently.

Heath R. Folpp, Hayden T. Schilling, Graeme F. Clark, Michael B. Lowry, Ben Maslen, Marcus Gregson, Iain M. Suthers. Artificial reefs increase fish abundance in habitat‐limited estuaries. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2020; DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.13666

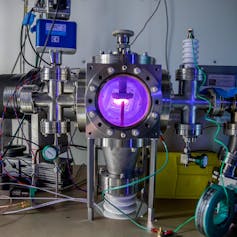

In a world first, Australian university builds own solar farm to offset 100% of its electricity use

Limiting global warming to well below 2℃ this century requires carbon emissions to reach net zero by around 2050. Australian households have done much to support the transition via rooftop solar investments. Now it’s time for organisations to take a more serious role.

The University of Queensland’s efforts to reduce its electricity emissions provides one blueprint. Last week UQ opened a 64 megawatt solar farm at Warwick in the state’s southeast. It’s the first major university in the world to offset 100% of its electricity use with renewable power produced from its own assets. In fact, UQ will generate more renewable electricity than it uses.

The Warwick Solar farm shows businesses and other organisations that the renewables transition is doable, and makes economic sense.

A Model For The Future

UQ’s electricity decarbonisation journey started a decade ago when it installed a 1.2MW rooftop solar array across buildings at the St Lucia campus. At the time, it was the largest rooftop solar array in Australia.

In 2015 UQ launched the 3.3MW solar farm at Gatton – part of a world-class solar research facility open to researchers from around the world.

Building on this, last week UQ opened the Warwick solar farm, primarily funded through a A$125 million loan from the Queensland Government. The output – about 160 gigawatt-hours a year – is equal to powering about 27,000 homes or reducing coal consumption by more than 60,000 tonnes. This generation will more than offset the total amount of energy UQ’s sites use each year.

Read more: Really Australia, it's not that hard: 10 reasons why renewable energy is the future

Money that would previously have been spent paying the university’s electricity bills will instead now pay off this loan, over about a decade. This shows how an organisation can redirect operating expenditure to invest in emissions reduction.

Three months ago, UQ also installed a 1.1MW Tesla battery at its St Lucia campus. As Queensland’s largest on-site battery, it saved UQ almost A$75,000 in electricity costs during the first three months of operation. It did this by buying power when it was cheap and selling it during peak demand periods, as well as helping support the grid during faults.

These projects provide a “living laboratory” for teaching and research. They also give crucial insights into how organisations can invest in renewable generation and energy storage assets today, to increase their commercial viability.

UQ has made data generated by its solar and battery assets publicly available so other organisations can learn from its efforts.

Why Organisations Must Act

About 2,000 companies are jointly responsible for more than half the world’s emissions. In many cases, investors are now calling on companies to demonstrate how their activities are compatible with a net-zero emissions target.

Organisations generate greenhouse gas emissions in different ways. “Scope 1” emissions come from assets owned or controlled by the organisation, such as company-owned vehicles or power plants. “Scope 2” emissions come from electricity consumed, and “Scope 3” involves a wide range of indirect emissions such as staff commuting or waste disposal.

Read more: A pretty good start but room for improvement: 3 experts rate Australia's emissions technology plan

Companies can also contribute to emissions produced overseas, but these are generally not captured by standard national emissions accounts.

A 2015 study was the first to translate global climate targets to a company level. Since then, more than 900 companies have committed to climate action through the Science Based Targets initiative.

Typically, companies are not yet evaluated in terms of their performance against climate goals. However, attention from investors on climate risk and impact is increasing. It’s only a matter of time before lagging companies will face greater scrutiny from investors, governments and the broader public. All the more reason to start acting today.

Over To You

An organisation must take a holistic view of all its activities, to fully understand the emissions it creates. From this they can develop a sustainability “action plan” which includes setting science-based targets . UQ is currently finalising a ten-year Sustainability Strategy based on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Other ways organisations can reduce emissions include:

entering into power purchase agreements with renewable energy generators – basically a contract for the sale and supply of renewable energy

investing in energy efficient equipment such as LED lighting and modern air conditioners

transitioning to a low-emission vehicle fleet and supporting sustainable transport alternatives such as electric scooters, bikes, cars and buses

minimising waste and recycling more

The time for talk is over. Organisations must now actively play their part in achieving global net-zero emissions. The University of Queensland shows how it can be done.

Read more: Climate explained: could the world stop using fossil fuels today? ![]()

Jake Whitehead, Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellow & Tritum E-Mobility Fellow, The University of Queensland; Andrew Wilson, Project Director - Warwick Solar Farm, The University of Queensland; Peta Ashworth, Professor and Chair in Sustrainable Energy Futures, The University of Queensland; Saphira Rekker, Lecturer Finance, The University of Queensland, and Tapan K Saha, Professor, Leader-UQ Solar, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

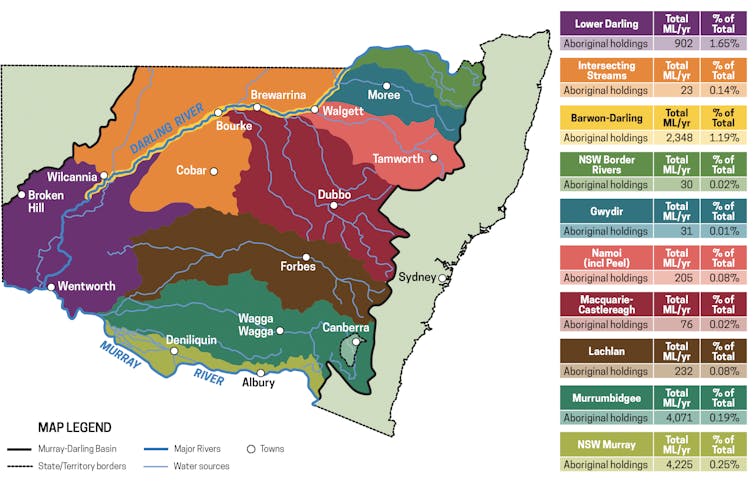

Australia has an ugly legacy of denying water rights to Aboriginal people. Not much has changed

Water management in the Murray-Darling Basin has radically changed over the past 30 years. But none of the changes have addressed a glaring injustice: Aboriginal people’s share of water rights is minute, and in New South Wales it is diminishing.

In the 1990s, governments tried to restore the health of rivers in the basin by limiting how much water could be extracted. They also separated land and water titles to enable farmers to trade water.

Read more: Aboriginal voices are missing from the Murray-Darling Basin crisis

This allowed the recovery of water for the environment and led to the world’s biggest water market, now worth billions of dollars. For a range of reasons, Aboriginal people have largely been shut out of this valuable water market.

Our research, the first of its kind, shows Aboriginal water entitlements in the Murray-Darling Basin are declining, and further losses are likely under current policies. This water injustice is an ongoing legacy of colonisation.

An Unjust Distribution Of Water

A water use right, also called a licence or entitlement, grants its holder a share of available water in a particular waterway. Governments allocate water against these entitlements periodically, depending on rainfall and water storage. Entitlement holders choose how to use this water. Typically, they extract it for purposes such as irrigation, or sell it on the temporary market.

We mapped Aboriginal water access and rights in NSW over more than 200 years, including the current scale of Aboriginal-held water entitlements.

Read more: Water in northern Australia: a history of Aboriginal exclusion

Across ten catchments in the NSW portion of the Murray-Darling Basin, Aboriginal people collectively hold just 12.1 gigalitres of water. This is a mere 0.2% of all available surface water (as of October 2018).

By comparison, Aboriginal people make up 9.3% of this area’s population.

The value of water held by Aboriginal organisations was A$16.5 million in 2015-16 terms, equating to just 0.1% of the value of the Murray-Darling Basin’s water market.

We wanted to understand how these limited water rights affect Aboriginal people today, and the challenges, if any, they face in holding onto these entitlements. This required examining Australia’s water history and its systems of water rights distribution.

Read more: No water, no leadership: new Murray Darling Basin report reveals states' climate gamble

What we found were key moments when governments denied Aboriginal people water rights and, by extension, the benefits that now flow from water access. This includes the ability to use water for an agricultural enterprise, or to temporarily trade water as many other entitlement holders do. We describe these moments as waves of dispossession.

The First Wave Of Dispossession

Under colonial water law, rights to use water, for example for farming, were granted to whoever owned the land where rivers flowed. This link between water use and land-holding remained in place until the end of the 20th century.

As a result, Aboriginal people, whose traditional ownership of land (native title) was only recognised by the Australian High Court in 1992, were largely denied legal rights to water.

The Second Wave

During the last quarter of the 20th century, governments introduced land restitution measures, such as the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act (1983), to redress or compensate Indigenous peoples for colonial acts of dispossession.

We found water entitlements were attached to some of the land parcels that were transferred to Aboriginal ownership under these processes – but this was the exception.

Read more: 5 ways the government can clean up the Murray-Darling Basin Plan

Land restitution processes intentionally restricted what land Aboriginal people could claim. They were biased against properties with agricultural potential and, therefore, very few of the properties that were returned to Aboriginal ownership came with water entitlements.

At this crucial juncture in land rights reform, federal and state governments entrenched the inequity of water rights distribution by increasing the security of the water rights of those who historically held entitlements. Governments have yet to pay serious attention to the claims of Aboriginal people who see a clear connection between the past and the present in the distribution of water entitlements.

The native title framework has not helped the situation either. Native title is the recognition that Indigenous peoples have rights to land and water according to their own laws and customs.

But it’s difficult for those making a native title claim to get substantial interests in land and waters. The Native Title Act 1993 defined native title to include rights to water for customary purposes and courts are yet to recognise a commercial right to water.

The Third Wave

We also identified a third wave of dispossession, now underway. From 2009 to 2018, the water rights held by Aboriginal people in the NSW portion of the Murray-Darling Basin shrunk by at least 17.2% (2.0 gigalitres of water per year). No new entitlements were acquired during this decade.

The decline is attributable to several factors, the most significant being forced permanent water (and land) sales arising from the liquidation of Aboriginal enterprises.

Read more: Australia’s inland rivers are the pulse of the outback. By 2070, they’ll be unrecognisable

With water rights held by Aboriginal people vulnerable to further decline, the options for Aboriginal communities to enjoy the wide-ranging benefits of water access may further diminish.

We expect rates of Aboriginal water ownership to be even smaller in other parts of the Murray-Darling Basin (and in jurisdictions beyond the Basin). Research is underway to explore this.

Australia Urgently Needs A Fair National Water Policy

The Productivity Commission is now reviewing Australian water policy, and must urgently address the injustices faced by Aboriginal people.

In developing a just water policy, governments must work with First Nations towards the twin goals of redressing historical inequities in water access and stemming further loss of water rights. Treaty negotiations may offer another avenue for water reform.

Over recent decades, Australia has been coming to terms with its colonial history of land management, returning more than a third of the continent to some form of Indigenous control under a “land titling revolution”.

But a water titling revolution that reconnects water law and policy to the social justice agenda of land restitution is long overdue. Indigenous peoples must have the opportunity to care for their land and waters holistically, and share more equitably in the benefits of water use.![]()

Lana D. Hartwig, Research Fellow, Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University; Natalie Osborne, Lecturer, School of Environment and Science, Griffith University, and Sue Jackson, Professor, ARC Future Fellow, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Blue Mountains National Park Plan Of Management Proposed Amendment: Public Consultation

The Proposed Amendment to the Blue Mountains National Park Plan of Management and Govetts Leap Draft Visitor Precinct Plan are available for public review and comment. View Blue Mountains National Park Proposed Amendment to Plan of Management - PDF, 978kb

Public exhibition of the proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan provides members of the community with an opportunity to have a say in planned improved accessibility works in Blue Mountains National Park. Comments close 17 August 2020.

What is a plan of management?

Parks and reserves established under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 must have a plan of management. The plan includes information on important park values and provides directions for future management. The plan of management is a legal document, and after the plan is adopted all operations and activities in the park must be in line with the plan. From time to time plans of management are amended to support changes to park management or proposed works.

Why is the plan being amended now?

Blue Mountains National Park is the most visited park in New South Wales, receiving more than 8 million visits in 2018. Visitor infrastructure improvements will enhance and disperse the visitor experience and improve protection of the park's values. The improvements to Govetts Leap visitor precinct will elevate the quality of interpretation and promotion of the park's World Heritage values.

The amendment relates to visitor facility upgrades to support both increased and better-dispersed visitation and includes:

- upgraded and increased capacity parking areas at Govetts Leap

- upgraded facilities to allow improved access for people with disabilities and/or restricted mobility

- enable pre-existing overnight stay facilities at Green Gully visitor precinct including a camping area and cabins.

What opportunities will the community have to comment?

The proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan are on public exhibition until Monday 17 August 2020. Everyone is invited to review the amendment and draft visitor precinct plan and provide comments.

When will the amended plan of management and visitor precinct plan be finalised?

At the close of the public exhibition period, we consider all submissions on the plan amendment and prepare a submissions report. We provide the Blue Mountains Regional Advisory Committee and the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council with the proposed amendment, all the submissions and the submissions report. They consider the documents, make comments on the amendment or suggest changes, and the Council provides advice to the Minister for Energy and Environment.

The Minister considers the amendment, submissions and advice, makes any necessary changes and decides whether to adopt the amendment under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. Once an amendment is adopted, it is published on the Department's website and key stakeholders, including those who made a submission on the draft plan, will be notified.

Submissions on the draft visitor precinct plan will be reviewed in conjunction with the Blue Mountains Regional Advisory Committee. The finalised Govetts Leap visitor precinct plan will be published on the Department's website.

How can I get more information about the proposed amendment?

For further information on the plan of management please contact the NPWS Park Management Planning Team at npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Where can I see a printed copy of the proposed amendment?

Copies are available at the following locations:

- National Parks and Wildlife Service Heritage Centre, Blackheath – end of Govetts Leap Road

- Blue Mountains City Council, Katoomba – Ground floor foyer, 2-6 Civic Place

How can I comment on the proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan?

Public exhibition of the proposed amendment and draft visitor precinct plan is from Friday 26 June until Monday 17 August 2020. You are invited to comment on the amendment by sending a written submission during this time.

To help us make the best use of your feedback:

- Please tell us what issue or part of the plan you are talking about. One way you can do this is to include the section heading and/or page number from the amendment in your submission.

- Tell us how we can make the plan better. You may want to tell us what you know about the park or how you or other people use and value it.

We are happy to hear any ideas or comments and will consider them all, but please be aware that we can't always include all information or ideas in the final plan.

Your privacy

Your submission will be provided to two advisory bodies. Your comments on the draft plan may include 'personal information'. The Department complies with the NSW Privacy and Personal Information Protection Act 1998, which regulates the collection, storage, quality, use and disclosure of personal information. For details see our privacy page. Information that in some way identifies you may be gathered when you use our website or send us an email.

If you indicate in your written submission that you object to your submission being made public, we will ask you before releasing your submission in response to any access applications under the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009.

Have your say

Public exhibition is from 26 June 2020 to 17 August 2020.

You can provide your written submission in any of the following ways:

Post your written submission to:

Manager Planning Evaluation and Assessment

Locked Bag 5022

Parramatta NSW 2124

Email your submission to: npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Make a submission online by using the online form here

Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan Of Management: Public Consultation

The Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management is available for review and comment.

Public exhibition of the draft plan provides an important opportunity for members of the community to have a say in the future management of Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve. Comments close 28 September 2020.

This plan has been prepared using a new format and presented as 2 separate documents:

- The plan of management which is the 'legal' document that will be provided to the Minister for formal adoption. This is the document we are seeking your feedback on.

- The planning considerations document supports the plan of management. It includes detailed information on park values (e.g. threatened species and cultural heritage) and threats to these values. A summary of this information is in the plan of management.

Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve encompasses about half of the Doodle Comer Swamp, an ephemeral wetland listed in the National Directory of Important Wetlands and the largest wetland of its type in southern NSW. The catchment for Doodle Comer Swamp is unregulated and the wetland has an unaltered water flow regime, now uncommon in New South Wales inland wetlands and of high conservation value.

When inundated, Doodle Comer Swamp attracts large numbers of waterbirds that use the swamp for breeding and foraging. When dry, the wetland provides habitat for the threatened bush stone-curlew, listed as endangered in New South Wales. Other threatened animals found include brolga and superb parrot. The reserve contains several threatened ecological communities such as Inland Grey Box Woodland and Sandhill Pine Woodland.

Doodle Comer Swamp is part of the Country of the Wiradjuri speaking nation and is part of a larger network of swamps and lagoons across the Riverina that formed a significant part of the cultural landscape, sustaining the Wiradjuri with an extensive range of resources for thousands of years. A diverse range of Aboriginal sites exist in the reserve and surrounding area and in 2016 Doodle Comer was declared an Aboriginal place recognising these values and the wetland's special significance to Aboriginal culture.

What is a plan of management?

Parks and reserves established under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 need to have a plan of management. The plan includes information on important park values and provides directions for future management. The plan of management is a legal document, and after the plan is adopted all operations and activities in the park must be in line with the plan. From time to time plans of management are amended to support changes to park management. Visit: Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management - PDF, 2.3MB

The National Parks and Wildlife Act sets out the matters that need to be considered when preparing a plan of management. These matters are addressed in the supporting Doodle Comer Swamp Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management: Planning considerations document.

Why is a plan being prepared now?

Since the park`s reservation in 2011, it has been managed according to a statement of management intent. After a park's reservation and before the release of its plan of management, a statement of management intent is prepared outlining the management principles and priorities for the park's management. This statement documents the key values, threats and management directions for the park. It is not a statutory document and a plan of management will still need to be prepared according to the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974.

Publication of a draft or final plan will replace the statement of management intent for the relevant parks covered.

What opportunities will the community have to comment?

The draft plan of management is on public exhibition until 28 September 2020 and anyone can review the plan of management and provide comments.

When will the plan of management be finalised?

At the end of the public exhibition period in September 2020 we will review all submissions, prepare a submissions report and make any necessary changes to the draft plan of management. The Far West Regional Advisory Committee and the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council will then review the plan along with the submissions and report, as required by the National Parks and Wildlife Act.

Once their input has been considered and any further changes made to the plan of management, we provide the plan to the Minister for Energy and Environment. The plan of management is finalised when the Minister formally adopts the plan under the National Parks and Wildlife Act. Once a plan is adopted it is published on the Department website and a public notice is advertised in the NSW Government Gazette.

How can I get more information about the draft plan?

For further information on the plan of management please contact the Park Management Planning Team at npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au.

How can I comment on the draft plan?

Public exhibition for the plan of management is from 26 June 2020 until 28 September 2020. You are invited to comment on the draft plan by sending a written submission during this time.

Have your say

Public exhibition is from 26 June 2020 to 28 September 2020.

You can provide your written submission in any of the following ways:

Post your written submission to:

Manager Planning Evaluation and Assessment

Locked Bag 5022

Parramatta NSW 2124

Email your submission to: npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Make a submission online by using the online form here

Tollingo Nature Reserve And Woggoon Nature Reserve Draft Plan Of Management: Public Consultation

The Tollingo Nature Reserve and Woggoon Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management is available for review and comment.

Public exhibition of the draft plan provides an important opportunity for members of the community to have a say in the future management of Tollingo Nature Reserve and Woggoon Nature Reserve. Comments close 28 September 2020.

This plan has been prepared using a new format which is presented as two separate documents: