Inbox and Environment News: Issue 471

October 25 - 31, 2020: Issue 471

Thousands Of Caper White Butterflies Over Pittwater

.jpg?timestamp=1603523768072)

Thousands of Caper White Butterflies were over Pittwater at the beginning of this week, delighting residents.

The Caper White butterfly, Belenois java, mainly lives west of the Great Dividing Range, where it feeds on caper shrubs, but is sometimes blown towards Sydney while on its northward migration - usually around November. Adults are mostly white with black margins to their upper wings and yellow-orange, black and white underwings. Their caterpillars are dark brown to olive green with white and yellow dots.

They live in urban areas, forests and woodlands.

In Spring great numbers of Caper White Butterflies migrate to where caper shrubs and creepers are more common. They usually fly inland, west of the Great Dividing Range, but a westerly wind can blow them off course and they may then be seen by people living along the coast. They maintain a rapid flight about 2 m - 3 m above the ground during the day, resting on shrubs and trees at night.

Migrations in New South Wales have been observed moving in a southerly direction during November and December. However, in the Australia Capital Territory, north-easterly flights have been observed, and both northerly and southerly flights have be reported near Sydney. Numbers in migrations can be very large and, in some cases, the adult butterflies can clog car radiators, causing overheating.

What people witnessed this week may remind them of the influx of Bogan moths from the south we once used to experience early in each Spring.

An interesting feature of this species is that it regularly migrates to areas where there are no food plants for its caterpillars. It is not understood why this behaviour has evolved.

The caterpillars of the Caper White Butterfly eat only plants belonging to the caper family (Capparis spp). These include native capers and warrior bushes. In fact, the caterpillars often occur in such large numbers on their food plants that they completely strip them of edible leaves. However the plants normally recover.

Find out about more Pittwater butterflies in: Pittwater Butterfly Notes and Butterflies from around Sydney

photo by A J Guesdon, October 2020

Coastal Angophora Now In Bloom

The coastal angophora are flowering and look like they are crowned in snow. The bees are feeding with a loud droning hum. - photo and caption by Selena Griffith

Aussie Back Yard Bird Count 2020: Over Four Million Birds Counted So Far

As we go to press 4, 105, 433 birds have been counted so far by Australians in the 2020 Aussie Backyard Bird Count. This year's statistics for our area and kind will be published once available - in the meantime, you still have until 4pm today, Sunday October 25th, to get your count in.

How to get involved

The Aussie Bird Count is a great way to connect with the birds in your backyard no matter where your backyard happens to be — a suburban backyard, a local park, a patch of forest, down by the beach, or the main street of town.

You can count as many times as you like over the week, we just ask that each count is completed over a 20-minute period. The data collected assists BirdLife Australia in understanding more about the birds that live where people live.

Register here: https://aussiebirdcount.org.au

Watch Out On The Pittwater Estuary Water Zones & Beaches: Seals Are About

Residents have filmed and photographed the seals living at Barrenjoey as far south as Rowland Reserve and over at Clareville beach in recent days and ask that people keep an eye out for them and ensure they are kept safe from boat strikes and dogs are kept off the beaches they're not supposed to be on.

Local Land Services Amendment Bill Passes Lower House; Koala ‘Compromise’ May Hasten Iconic Animal Extinction

The NSW Government’s Local Land Services Amendment (Miscellaneous) Bill 2020 is not only a massive step backwards for koala protection in NSW, but also removes many other critical environmental protections on private land, according to Greens MP and Chair of the Inquiry into Koala Populations and their Habitat, Cate Faehrmann.

The bill winds back existing environmental protections and expressly prohibits the protection of any further core koala habitat from threats such as logging and land clearing on private land.

Greens MP and Environment spokesperson and Chair of the NSW Parliamentary Koala Inquiry Cate Faehrmann said “This bill isn’t a ‘compromise’ on the new koala policy. It takes koala protections back 25 years at a time when we need to be strengthening laws to protect koala habitat. We lost maybe 10,000 koalas in NSW in the black summer fires. If this bill passes, the Government may as well sign be signing their death warrant.”

“The updated Koala SEPP has been years in the making but now all that hard work has been scrapped to appease the National Party and the powerful timber and farming lobbies.

“We know the Koala is on track for extinction before 2050, we know that existing protections are not enough. How on earth can the Premier wind back koala protections and insist she wants to be the ‘Premier that saves the Koala’. With the introduction of this bill, she is about to become the Premier that kills the Koala.

“The bill ignores the recommendations of several inquiries and pre-empts the reviews into the land management framework and private native forestry. Part of me wonders if Gladys and Stokes even comprehend just how devastating these changes are, it’s that hard to fathom how they could have accepted this ‘compromise’, said Ms Faehrmann.

The bill passed the NSW lower house on Wednesday October 21st and is scheduled to be debated in the Legislative Council in November.

“If this bill passes, developers and big agribusiness will be free to destroy koala habitat in nine out of 10 council areas across NSW where koalas are likely to occur,” Nature Conservation Council Chief Executive Chris Gambian said.

“The bill not only limits koala protection laws to a tiny portion of the state, it rules out ever extending those protections into new areas where they are desperately needed.

“If passed by members of the upper house, this law will allow property developers to bulldoze koala trees and subdivide some of the best koala forests left in NSW to create hobby farms and suburbs.

“Currently, the koala SEPP only applies in six of the 88 council areas where koalas are likely to occur.

“The changes mean genuine efforts to protect koalas on private land will be limited to those areas.

Dailan Pugh, President of the North East Forest Alliance, said "At a time when Koala populations are crashing, with climate change induced droughts and fires decimating survivors, and predictions of extinction in the wild by 2050, it is reprehensible that the Berejiklian Government is changing the rules to remove protection for core Koala habitat so as to allow it to be logged and cleared indiscriminately.”

"To appease the loggers these changes are designed to wind back 25 years of protection for Koalas and other threatened species on private lands, in their hour of greatest need,” he said

Bellingen Shire Greens Mayor Dominic King said “This is the final nail for Koalas in our region. After the extreme five year drought, the catastrophic fires that destroyed vast areas of Koala habitat, the increase in post fire logging, the findings of the Parliamentary Inquiry 2020 which predicted that Koalas would be extinct by 2050, we now have a proposal that will allow the logging of core koala habitat in our shire. This effectively removes any protection afforded to core koala habitat in Bellingen despite the fact that has been endorsed by both Council and the NSW government, and baffling has not been referred in the amending bill.”

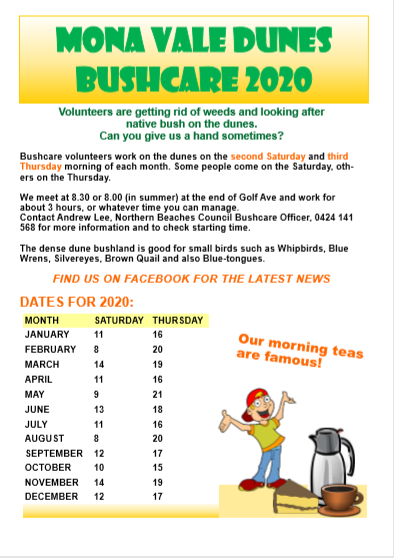

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Analysis: The Truth About The NSW Koala SEPP

In September the NSW Nationals threatened to break up the state’s governing coalition over a koala protection policy they say creates an unfair amount of “red and green” tape for farmers. But as EDO Policy and Law Reform Director Rachel Walmsley writes, the regulation is a minor update that does not do enough to protect koala habitat.

Of all the policies in the world to get upset about, this is really not one of them. There has been a lot of misinformation about the NSW Government’s planning policy on development in areas of koala habitat – the State Environmental Planning Policy (Koala Habitat Protection) 2019 (Koala SEPP) – that needs to be clarified. The current political debate appears to be triggered by assessment requirements proposed in a draft guideline being prepared under the updated SEPP – itself a subordinate regulatory instrument, which has already been in operation since March 2020. There is no change to the legislation that currently allows the clearing of koala habitat in NSW.

The new SEPP is one limited legal tool intended to help koalas, and on our expert analysis (see below) the SEPP will remain largely ineffective in addressing the exacerbated threats currently facing them. It took just weeks for almost a quarter of koala habitat in NSW to be burnt in the bushfires, while it has taken the NSW Government 10 years to update the list of relevant koala habitat trees in the SEPP and fix up the definition of core koala habitat. The need for enforceable and effective laws is now more urgent than ever. The suggestion that this limited policy should be further weakened is 100% politics and 0% evidence-based.

Here are 10 facts about the new Koala SEPP:

- The new Koala SEPP is a minor strengthening of an existing instrument. There has been a policy setting out requirements for plans and development assessments in core koala habitat since 1995.[1]

- It is standard practice for Development Application processes to require assessment of impacts on a threatened species. This is not new, not unusual, and not unreasonable for a species headed for extinction.

- The Koala SEPP does not prohibit the clearing of koala habitat. In fact, outside of national parks, no areas of koala habitat are off limits to development under NSW laws.

- The Koala SEPP only applies for development that requires development approval under planning laws – the rules for routine farming activity and rural land clearing have not changed. That is, the Koala SEPP may apply to a farmer lodging a development application to their local council to carry out development in koala habitat, but it’s highly likely that such a development would have required assessment under the previous SEPP anyway.

- The relationship between the Koala SEPP and land clearing laws has not changed. Even if areas become mapped as core koala habitat under a comprehensive koala plan of management (a mechanism in both the former and current koala policy, and one that requires consultation and approval), and subsequently code-based clearing is excluded from those sensitive regulated areas, farmers can still apply and get approval to clear koala habitat under land clearing laws.

- The definition of koala habitat has been expanded due to the fact that the list of relevant tree species has been updated to improve scientific accuracy. While there are now 123 species identified, the listings are region specific and some regions such as Riverina, only list 9 relevant species. It has taken 10 years to update the definition of koala habitat so that it is scientifically accurate.

- Both the former and new Koala SEPPs apply to specified local government areas, (excluding National Parks and State Forests), and only on land over one hectare.

- Under the new SEPP, where a proposed development has low or no impact on koala habitat, no survey is required.

- The new SEPP does not rezone land, and the option for Councils to do a Koala Plan of Management is still voluntary, and involves consultation.

- Koala populations are headed for extinction by 2050 (or sooner) unless their habitat is protected. The policy under debate is still nowhere near the standard of regulation needed to effectively protect habitat of this iconic species.

Read our detailed analysis of the SEPP reform process:

The new NSW SEPP – State Environmental Planning Policy (Koala Habitat Protection) 2019 – commenced on 1 March 2020. With koala numbers having been in decline in NSW over the past two decades, a revised Koala SEPP was highly anticipated as an opportunity to bolster legal protections for koalas. Frustratingly, the finalised Koala SEPP does little more than tinker around the edges. The fact remains that NSW laws fall far short of providing tangible protection for koalas. And with koala populations and their habitats significantly impacted by the summer’s devastating bushfires, it’s going to take more than just a few revisions to provide our koalas and their habitats the real legal protection they need.

The status of koalas in NSW

Koalas are currently listed as a vulnerable threatened species in NSW, meaning there is a high risk of extinction in the medium-term.[2] Additionally, individual populations at Hawks Nest and Tea Gardens on the lower north coast, between the Tweed and Brunswick Rivers east of the Pacific Highway in the Northern Rivers area and within the Pittwater Local Government Area in northern Sydney are listed as endangered populations.[3]

Accurately estimating koala numbers is difficult. Despite regulations, policies and community initiatives, overall koala numbers in NSW are in decline. In 2016, the NSW Chief Scientist relied on the figures of Adams-Hoskings et.al. in estimating approximately 36,000 koalas in NSW, representing a 26% decline over the past three koala generations (15-21 years).[4] We note however that other reports suggest koala numbers are even lower than this.[5]

These estimates were made before the catastrophic bushfire events of this summer, which have been devastating for koalas, with estimates showing that more than 24% of all koala habitats in eastern NSW are within fire-affected areas.[6] Many people are asking how our environmental laws can help conserve and restore vulnerable wildlife at this time – this is something that EDO continues to look at as we start to move forward from the events of this summer (see our response to Australia’s climate emergency).

A new state environmental planning policy is one legal tool intended to help koalas, but on our analysis the SEPP will remain largely ineffective in addressing the exacerbated threats currently facing them. It took just weeks for almost a quarter of koala habitat in NSW to be burnt in the bushfires, while it has taken the NSW Government 10 years to simply update the list of relevant koala habitat trees in the SEPP. The need for enforceable and effective laws is now more urgent than ever.

Key changes to the NSW Koala SEPP[7]

On 1 March 2020, the NSW State Environmental Planning Policy No 44 – Koala Habitat Protection (SEPP 44)[8], which has been in place since 1995, was repealed and replaced by a new State Environmental Planning Policy (Koala Habitat Protection) 2019 (new Koala SEPP).[9]

SEPP 44 aimed to protect koalas and their habitat, but its settings were weak and not targeted at the type or scale of projects with highest impact. Additionally, the problematic definitions of core koala habitat and potential koala habitat were adopted by other legislation (including the Local Land Services Act 2013 (LLS Act) and the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act)), where they were used as a benchmark for triggering processes and regulation relating to land clearing and development assessment.[10]

EDO has been calling for changes to SEPP 44 for the best part of a decade. In December 2010, EDO wrote to the Government on behalf of Friends of the Koala noting that SEPP 44 ‘is in urgent need of reform’.[11] In 2016, the Government announced a review of SEPP 44.[12] EDO made a submission on the Review of the Koala SEPP outlining our key concerns with its operation and making recommendations for improvement.[13] It wasn’t until fires began burning across the state late last year that the Government announced the release of the new Koala SEPP, just days before Christmas.

Despite recommendations that the Government consult on the text of a draft SEPP and any relevant guidelines or supporting material following its 2016 review, the final SEPP was made without any additional consultation; but it does address a number of stakeholder concerns. Most significantly, it updates the definition of ‘core koala habitat’ and removes the problematic concept of ‘potential koala habitat’, instead relying on mapping (a new Koala Development Application Map and new Site Investigation areas for Koala Plans of Management Map) to initially identify koala habitat. However, certain legal mechanisms still apply only to core koala habitat.[14]

The new SEPP also updates the list of feed tree species in Schedule 2, used to help identify koala habitat, from 10 species to 123 species, categorised into 9 distinct regions. Other key changes include:

- Removing the requirement for site specific plans of management (in instances where a comprehensive Koala Plan of Management is not in place), instead requiring decision-makers to take into account new standard requirements in a Koala Habitat Protection Guideline. Concerningly, the Guidelines have not yet been seen, there are no formal requirements for developing the Guidelines (e.g. no requirements for community consultation or peer review) and the standards within the Guidelines are not mandatory – the new Koala SEPP requires only that they be taken into account.

- Moving provisions relating to how local environment plans and other planning instruments should give effect to protection to koalas from the SEPP to a new Ministerial planning direction (which is yet to be made).

Ongoing concerns

There are also a number of key concerns that have not been addressed by the new Koala SEPP. For example:

- No areas of koala habitat are off-limits to clearing or offsetting – NSW laws do not prohibit the clearing of koala habitat. Despite declining koala numbers and the devastation caused by this summer’s fires, NSW laws still allow koala habitat to be cleared with approval. The new Koala SEPP simply requires decision-makers to ensure development approvals are consistent with koala plans of management (PoMs) or, if a PoM is not in place, that the (yet-to be-made) Guidelines are taken into account. If our laws are to truly protect koalas and their habitats then the approval process must not allow important koala habitat to be offset or cleared in exchange for money, in the way that the NSW Biodiversity Assessment Method does. Rather, all development that has serious or irreversible impacts on koala habitat must be refused.

- The requirement for councils to prepare Comprehensive Koala PoMs remains voluntary – Due to the slow uptake by councils (only 5 comprehensive PoMs have been finalised since SEPP 44 commenced in 1995),[15] EDO has previously recommended that the preparation of comprehensive koala PoMs (CKPoMs) be mandatory (i.e. the SEPP require that draft CKPoMs be prepared and exhibited within a particular timeframe).

- The new Koala SEPP still only applies to limited types of development – As was the case with SEPP 44, the new Koala SEPP still only applies to council-approved development. This means that the new Koala SEPP does not apply to the wide range of development and activities that can impact on koala habitat, including complying development, major projects (State significant development and State significant infrastructure), Part 5 activities (e.g. activities undertaken by public authorities) and land clearing activities requiring approval under the LLS Act.

- The 1 hectare requirement has not been removed – The arbitrary threshold of 1ha for triggering SEPP 44 has been carried over to the new Koala SEPP. Excluding sites below 1ha from the Koala SEPP leaves small koala habitat areas, particularly koala habitat in urban areas, without adequate protection. The 1 hectare requirement also contributes to cumulative impacts and can reduce connectivity across the landscape by allowing small patches to be cleared.

- Climate change considerations have been overlooked – The review of SEPP 44 provided an opportunity to incorporate requirements to identify and protect habitat and corridors that will support koalas’ resilience to more extreme heat and natural disasters, even if there is no koala population in those areas now, however there is nothing in the new Koala SEPP that specifically addresses climate change.

- Monitoring and compliance requirements have not improved – There are no new requirements relating to monitoring, review, reporting and compliance in the new Koala SEPP.

The future for NSW koalas

The new Koala SEPP highlights the overarching deficiencies in NSW laws to provide genuine protections for wildlife and nature. The way our laws are designed, very little is off limits to development or activities such as urban development, mining, and agriculture. While environmental laws provide processes for assessing environmental impacts, at the end of the day weak offsetting laws and discretionary decision-making powers allow destructive activities to go ahead to the detriment of our wildlife and natural resources. Contradictory policy settings in NSW laws mean that laws aimed at conserving biodiversity and maintaining the diversity and quality of ecosystems (such as the BC Act) are undermined by other legislation that facilitates forestry, agricultural activities and developments (such as the LLS Act, Forestry Act 2012 (Forestry Act) and Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act)).

Many of the recent initiatives by the NSW Government to address koala conservation have focused mainly on funding and policy, without substantial legislative or regulatory reform to increase legal protections for koala populations and habitat. The new Koala SEPP is no exception. While some improvements have been made, particularly in relation to the definition of core koala habitat, overall many concerns remain and the Koala SEPP is unlikely to result in improved outcomes for koalas.

Until our laws are strengthened to truly limit or prohibit the destruction of koala habitat, koala populations and their habitat will continue to be at risk and koala numbers will continue to decline in NSW, possibly to the point of local extinction.

References

- [1] The former State Environmental Planning Policy No. 44 – Koala Habitat Protection, commenced in 1995.

- [2] Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, s 4.4(3)

- [3] See www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedSpeciesApp/profile.aspx?id=20300; www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedSpeciesApp/profile.aspx?id=10615 and www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedSpeciesApp/profile.aspx?id=10614

- [4] NSW Chief Scientist & Engineer, Report of the Independent Review into the Decline of Koala Populations in Key Areas of NSW, December 2016 above no 6, citing Adams-Hosking, C, McBride, M.F, Baxter, G, Burgman, M, de Villiers, D, Kavanagh, R, Lawler, I, Lunney, D, Melzer, A, Menkhorst, P, Molsher, R, et al. (2016). Use of expert knowledge to elicit population trends for the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Diversity and Distributions, 22(3), 249-262. doi: 10.1111/ddi.12400

- [5] See, for example, Paull, D., Pugh, D., Sweeney, O., Taylor, M.,Woosnam, O. and Hawes, W. Koala habitat conservation plan. An action plan for legislative change and the identification of priority koala habitat necessary to protect and enhance koala habitat and populations in New South Wales and Queensland (2019), published by WWF-Australia, Sydney, which estimates koala numbers to be in the range of 15,000 to 25,000 animals. In 2018, the Australian Koala Foundations estimates koala numbers in NSW to be between 11,555 and 16,130 animals, see www.savethekoala.com/our-work/bobs-map-%E2%80%93-koala-populations-then-and-now

- [6] See Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, Understanding the impact of the 2019-20 fires, https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/parks-reserves-and-protected-areas/fire/park-recovery-and-rehabilitation/recovering-from-2019-20-fires/understanding-the-impact-of-the-2019-20-fires

- [7] See https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Policy-and-Legislation/Environment-and-Heritage/Koala-Habitat-Protection-SEPP

- [8]See https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/#/view/EPI/1995/5

- [9] See https://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/#/view/EPI/2019/658

- [10] As noted earlier in our submission, for example, for the purpose of the land management regime under Part 5A of the Local Land Services Act 2013, category 2-sensitive regulated land (on which clearing is more strictly regulated) is to include ‘core koala habitat’.

- [11] EDO NSW Submission on State Environmental Planning Policy No 44 – Koala Habitat, December 2010, available at https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/edonsw/pages/3547/attachments/original/1485908888/Attachment_A_-_2010_EDONSW_SEPP_44_Submission_for_FOK.pdf?1485908888

- [12] See https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Policy-and-Legislation/State-Environmental-Planning-Policies-Review/Draft-koala-habitat-protection-SEPP

- [13]See https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/edonsw/pages/3547/attachments/original/1485908884/170131_Koala_SEPP_44_Review_Submission_-_FINAL_to_DPE.pdf?1485908884

- [14] For example, under clause 9 of State Environmental Planning Policy (Koala Habitat Protection) 2019, which applies to development on land for which no PoM is in place, the Guidelines will not apply if a suitably qualified and experienced person provides information that the land is not core koala habitat. [15] There are only approved plans for five council areas, and a further nine Councils who have drafted or undertaken koala habitat studies See https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/animals-and-plants/native-animals/native-animal-facts/koala/koala-conservation

Hard to spot, but worth looking out for: 8 surprising tawny frogmouth facts

The tawny frogmouth is one of Australia’s most-loved birds. In fact, it was first runner-up in the Guardian/BirdLife Australia bird of the year poll (behind the endangered black-throated finch).

Tawny frogmouths are found throughout Australia, including cities and towns, and population numbers are healthy. We’re now in the breeding season – which runs from August to December – so you may have been lucky enough to see some pairs with chicks recently.

Here are eight fascinating things about tawny frogmouths that you might not know.

Read more: What Australian birds can teach us about choosing a partner and making it last

1. They Are Excellent Parents

Tawny frogmouths are excellent parents. Both males and females share in building the nest and incubating the eggs, generally one to three. The eggs take 30 days to hatch, with the male incubating during the day and both sexes taking turns during the night.

Once hatched, both parents are very involved in feeding the fledglings. A young bird’s wings take about 25 to 35 days to develop enough strength for flight (a process known as “fledging”).

2. They Mate For Life

Tawny frogmouths pair for life. Breeding pairs spend a great deal of time roosting together and the male often gently strokes the female with his beak. Some researchers report seeing tawny frogmouths appear to “grieve” when their partner dies.

For example, renowned bird behaviour expert Gisela Kaplan tells of rearing a male tawny frogmouth on her property then releasing it to the wild. It found a female mate and raised nestlings. One day, the female was run over on the highway; Kaplan recognised its markings.

She found the male “whimpering” on a nearby post. Kaplan reportedly said: “It sounds like a baby crying. It affects you to listen to it.” According to Kaplan, the male stayed there for four days and nights, and did not eat or drink.

3. They’re Not Owls

Although tawny frogmouths are often referred to as owls, they are not. But they do resemble owls with their large eyes, soft plumage and camouflage patterns, because both owls and frogmouths hunt at night. This phenomenon (where two species develop the same attributes, despite not being closely related) is called “convergent evolution”.

Unlike owls, tawny frogmouths do not have powerful feet and talons with which to capture prey. Instead, they prefer to catch prey with their beaks. Their soft, wide, forward-facing beaks are designed for catching insects. They will also feed on small birds, mammals and reptiles.

4. They Are Masters Of Disguise

Tawny frogmouths are extremely well camouflaged and when staying statue-still on a tree branch they appear to be part of the tree itself. They often choose to perch near a broken tree branch and thrust their head at angle, further mimicking a tree branch.

5. They Make Strange Noises

Tawny frogmouths are quite vocal at night and have a range of calls from deep grunting to soft “wooing”. When threatened, they make a loud hissing sound. Their vocalisations have also variously been described as purring, screaming and crying.

6. They Can Survive Extremes

In colder regions of Australia, tawny frogmouths are able to survive the winter months by going into torpor for a few hours. In this state, an animal slows its heart rate and metabolism and lowers its body temperature to conserve energy.

On very hot summer days tawny frogmouths will produce mucus in their mouths which cools the air they breathe in, thereby cooling their whole body.

7. They Need Old Trees

It’s not that uncommon to see tawny frogmouths dead on the road; they often flit across the road chasing insects at night and can be hit by cars.

Tawny frogmouth populations are holding relatively steady, but there is a shortage of old trees for nesting. They especially like trees with old branches as they mimic old branches and stick out like sore thumbs on young branches.

When one NSW council chopped down a suburban tree that a tawny frogmouth pair had reportedly used for years as a nesting site, one of the birds was photographed sitting on a nearby woodchipper — a poignant image.

8. They’re Not Good At Building Nests.

Tawny frogmouths are pretty slack when it comes to nest building. They simply dump twigs and leaves in a pile and that is it. Chicks and eggs have even fallen out of the nest when parents are swapping brooding duties.

Read more: Laughs, cries and deception: birds' emotional lives are just as complicated as ours ![]()

Les Christidis, Professor, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Japan plans to dump a million tonnes of radioactive water into the Pacific. But Australia has nuclear waste problems, too

Tilman Ruff, University of Melbourne and Margaret BeavisThe Japanese government recently announced plans to release into the sea more than 1 million tonnes of radioactive water from the severely damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

The move has sparked global outrage, including from UN Special Rapporteur Baskut Tuncak who recently wrote,

I urge the Japanese government to think twice about its legacy: as a true champion of human rights and the environment, or not.

Alongside our Nobel Peace Prize-winning work promoting nuclear disarmament, we have worked for decades to minimise the health harms of nuclear technology, including site visits to Fukushima since 2011. We’ve concluded Japan’s plan is unsafe, and not based on evidence.

Japan isn’t the only country with a nuclear waste problem. The Australian government wants to send nuclear waste to a site in regional South Australia — a risky plan that has been widely criticised.

Contaminated Water In Leaking Tanks

In 2011, a massive earthquake and tsunami resulted in the meltdown of four large nuclear reactors, and extensive damage to the reactor containment structures and the buildings which house them.

Water must be poured on top of the damaged reactors to keep them cool, but in the process, it becomes highly contaminated. Every day, 170 tonnes of highly contaminated water are added to storage on site.

As of last month, this totalled 1.23 million tonnes. Currently, this water is stored in more than 1,000 tanks, many hastily and poorly constructed, with a history of leaks.

How Does Radiation Harm Marine Life?

If radioactive material leaks into the sea, ocean currents can disperse it widely. The radioactivity from Fukushima has already caused widespread contamination of fish caught off the coast, and was even detected in tuna caught off California.

Read more: Four things you didn’t know about nuclear waste

Ionising radiation harms all organisms, causing genetic damage, developmental abnormalities, tumours and reduced fertility and fitness. For tens of kilometres along the coast from the damaged nuclear plant, the diversity and number of organisms have been depleted.

Of particular concern are long-lived radioisotopes (unstable chemical elements) and those which concentrate up the food chain, such as cesium-137 and strontium-90. This can lead to fish being thousands of times more radioactive than the water they swim in.

Failing Attempts To De-Contaminate The Water

In recent years, a water purification system — known as advanced liquid processing — has been used to treat the contaminated water accumulating in Fukushima to try to reduce the 62 most important contaminating radioisotopes.

But it hasn’t been very effective. To date, 72% of the treated water exceeds the regulatory standards. Some treated water has been shown to be almost 20,000 times higher than what’s allowed.

Read more: The cherry trees of Fukushima

One important radioisotope not removed in this process is tritium — a radioactive form of hydrogen with a half-life of 12.3 years. This means it takes 12.3 years for half of the radioisotope to decay.

Tritium is a carcinogenic byproduct of nuclear reactors and reprocessing plants, and is routinely released both into the water and air.

The Japanese government and the reactor operator plan to meet regulatory limits for tritium by diluting contaminated water. But this does not reduce the overall amount of radioactivity released into the environment.

How Should The Water Be Stored?

The Japanese Citizens Commission for Nuclear Energy is an independent organisation of engineers and researchers. It says once water is treated to reduce all significant isotopes other than tritium, it should be stored in 10,000-tonne tanks on land.

If the water was stored for 120 years, tritium levels would decay to less than 1,000th of the starting amount, and levels of other radioisotopes would also reduce. This is a relatively short and manageable period of time, in terms of nuclear waste.

Then, the water could be safely released into the ocean.

Nuclear Waste Storage In Australia

Australians currently face our own nuclear waste problems, stemming from our nuclear reactors and rapidly expanding nuclear medicine export business, which produces radioisotopes for medical diagnosis, some treatments, scientific and industrial purposes.

Read more: Australia should explore nuclear waste before we try domestic nuclear power

This is what happens at our national nuclear facility at Lucas Heights in Sydney. The vast majority of Australia’s nuclear waste is stored on-site in a dedicated facility, managed by those with the best expertise, and monitored 24/7 by the Australian Federal Police.

But the Australian government plans to change this. It wants to transport and temporarily store nuclear waste at a facility at Kimba, in regional South Australia, for an indeterminate period. We believe the Kimba plan involves unnecessary multiple handling, and shifts the nuclear waste problem onto future generations.

The proposed storage facilities in Kimba are less safe than disposal, and this plan is well below world’s best practice.

The infrastructure, staff and expertise to manage and monitor radioactive materials in Lucas Heights were developed over decades, with all the resources and emergency services of Australia’s largest city. These capacities cannot be quickly or easily replicated in the remote rural location of Kimba. What’s more, transporting the waste raises the risk of theft and accident.

And in recent months, the CEO of regulator ARPANSA told a senate inquiry there is capacity to store nuclear waste at Lucas Heights for several more decades. This means there’s ample time to properly plan final disposal of the waste.

The legislation before the Senate will deny interested parties the right to judicial review. The plan also disregards unanimous opposition by Barngarla Traditional Owners.

Read more: Uranium mines harm Indigenous people – so why have we approved a new one?

The Conversation contacted Resources Minister Keith Pitt who insisted the Kimba site will consolidate waste from more than 100 places into a “safe, purpose-built, state-of-the-art facility”. He said a separate, permanent disposal facility will be established for intermediate level waste in a few decades’ time.

Pitt said the government continues to seek involvement of Traditional Owners. He also said the Kimba community voted in favour of the plan. However, the voting process was criticised on a number of grounds, including that it excluded landowners living relatively close to the site, and entirely excluded Barngarla people.

Kicking The Can Down The Road

Both Australia and Japan should look to nations such as Finland, which deals with nuclear waste more responsibly and has studied potential sites for decades. It plans to spend 3.5 billion euros (A$5.8 billion) on a deep geological disposal site.

Read more: Risks, ethics and consent: Australia shouldn't become the world's nuclear wasteland

Intermediate level nuclear waste like that planned to be moved to Kimba contains extremely hazardous materials that must be strictly isolated from people and the environment for at least 10,000 years.

We should take the time needed for an open, inclusive and evidence-based planning process, rather than a quick fix that avoidably contaminates our shared environment and creates more problems than it solves.

It only kicks the can down the road for future generations, and does not constitute responsible radioactive waste management.

The following are additional comments provided by Resources Minister Keith Pitt in response to issues raised in this article (comments added after publication):

(The Kimba plan) will consolidate waste into a single, safe, purpose-built, state-of-the-art facility. It is international best practice and good common sense to do this.

Key indicators which showed the broad community support in Kimba included 62 per cent support in the local community ballot, and 100 per cent support from direct neighbours to the proposed site.

In assessing community support, the government also considered submissions received from across the country and the results of Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation’s own vote.

The vast majority of Australia’s radioactive waste stream is associated with nuclear medicine production that, on average, two in three Australians will benefit from during their lifetime.

The facility will create a new, safe industry for the Kimba community, including 45 jobs in security, operations, administration and environmental monitoring.

Tilman Ruff, Associate Professor, Education and Learning Unit, Nossal Institute for Global Health, School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne and Margaret Beavis, Tutor Principles of Clinical Practice Melbourne Medical School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tick Population Booming In Our Area

Residents from Terrey Hills and Belrose to Narrabeen and Palm Beach report a high number of ticks are still present in the landscape. Local Veterinarians are stating there has not been the usual break from ticks so far and each day they’re still getting cases, especially in treating family dogs.

To help protect yourself and your family, you should:

- Use a chemical repellent with DEET, permethrin or picaridin.

- Wear light-colored protective clothing.

- Tuck pant legs into socks.

- Avoid tick-infested areas.

- Check yourself, your children, and your pets daily for ticks and carefully remove any ticks using a freezing agent.

- If you have a reaction, contact your GP for advice.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Pittwater Reserves

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Final Hearing For Aged Care Royal Commission

- each of the 124 recommendations proposed by Counsel Assisting

- eight additional matters addressed in Counsel Assisting’s final submissions, namely:

- My Aged Care and an improved provider search function

- Care at home

- Allied health care

- Workforce: short term arrangements to increase wages

- Direct employment of care workers

- Informal carers: leave entitlement

- Financing

- Capital financing

- seven topics about which Commissioner Briggs made remarks during the hearing, namely:

- Aged care policy principles

- System design and governance

- Program management

- Restraints

- Provider leadership and culture

- Research and data governance

- Capital financing

Seniors Get Tech Savvy In Online Week

What It’s Like For People Inside The Aged Care System

A Promising New Tool In The Fight Against Melanoma

The 'Goldilocks Day': The Perfect Day For Kids' Bone Health

- 1.5 hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (sports, running around)

- 3.4 hours of light physical activity (walking, doing chores)

- 8.2 hours of sedentary time (studying, sitting at school, reading)

- 10.9 hours of sleep.

Nanogenerator 'Scavenges' Power From Their Surroundings

$200,000 Revamp For Norah Head Lighthouse

Seeing No Longer Believing: The Manipulation Of Online Images

Disclaimer: These articles are not intended to provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of Pittwater Online News or its staff.