Inbox and Environment News: Issue 473

November 8 - 14, 2020: Issue 473

Parra'dowee Time

November-December

Goray'murrai—Warm and wet, do not camp near rivers

This season begins with the Great Eel Spirit calling his children to him, and the eels which are ready to mate make their way down the rivers and creeks to the ocean.

It is the time of the blooming of the Kai'arrewan (Acacia binervia) which announces the occurrence of fish in the bays and estuaries.

Acacia binervia, commonly known as the coast myall, is a wattle native to New South Wales and Victoria.

Bark Shedding Time - Pittwater Spotted Gums

.jpg?timestamp=1604150614681)

photo taken this week - by A J Guesdon.

Watch Out On The Pittwater Estuary Water Zones & Beaches: Seals Are About

Residents have filmed and photographed the seals living at Barrenjoey as far south as Rowland Reserve and over at Clareville beach in recent days and ask that people keep an eye out for them and ensure they are kept safe from boat strikes and dogs are kept off the beaches they're not supposed to be on.

.jpg?timestamp=1604732571870)

.jpg?timestamp=1604732604972)

.jpg?timestamp=1604732642700)

This slug (Triboniophorus graeffei) feeds on microscopic algae on smooth bark eucalypts, and algae on other smooth surfaces, leaving a narrow wiggly track. The Red Triangle Slug is Australia's largest native land slug. The distinctive red triangle on its back contains the breathing pore. This one was photographed in the Pittwater Online backyard this week amid all the rain we've had.

More at: australianmuseum.net.au/learn/animals/molluscs/red-triangle-slug

First Christmas Bells Of The Year

photo by Selena Griffith, November 7, 2020

Blandfordia nobilis, commonly known as Christmas bells or gadigalbudyari in Cadigal language, is a flowering plant endemic to New South Wales. It is a tufted, perennial herbs with narrow, linear leaves and between three and twenty large, drooping, cylindrical to bell-shaped flowers. The flowers are brownish red with yellow tips. It is one of four species of Blandfordia known as Christmas bells.

Blandfordia nobilis was first formally described in 1804 by English botanist James Edward Smith who published the description in Exotic Botany from dried specimens sent from Sydney by the colonial surgeon, John White. The type specimen was collected from Port Jackson about the year 1800. Blandfordia nobilis was first published in 1804 by English botanist James Edward Smith, and it still bears its original name. The specific epithet (nobilis) is a Latin word meaning "well-known", "celebrated" or "noble".

This photo of a stem of Christmas Bells was taken by a lady who lives here and loves to go for long walks through the bush in our area - bright, aren't they?

2020 BirdLife Australia Photography Awards Winners

Earlier this week an email from BirdLife Australia announced the results of the 2020 BirdLife Australia Photography Awards are now live on the official Awards website.

A huge congratulations to prize winners and short-listed entrants! All the entries were outstanding. With a record smashing 6207 entries the judges didn’t have an easy task!

Most importantly, thanks to the volume of entries BirdLife Australia will be able to donate a sizeable amount of the funds raised by the Awards to support BirdLife Australia's Preventing Extinctions Grey Range Thick-billed Grasswren project to help bring this critically endangered bird back from the brink.

Great news!

The 2021 Awards will open again mid-year with a new special theme: Plovers! So get those cameras and get some gorgeous photos for your chance to win.

Happy Birding!

The Coast

Radio Northern Beaches

Draft Bush Fire Management Policy

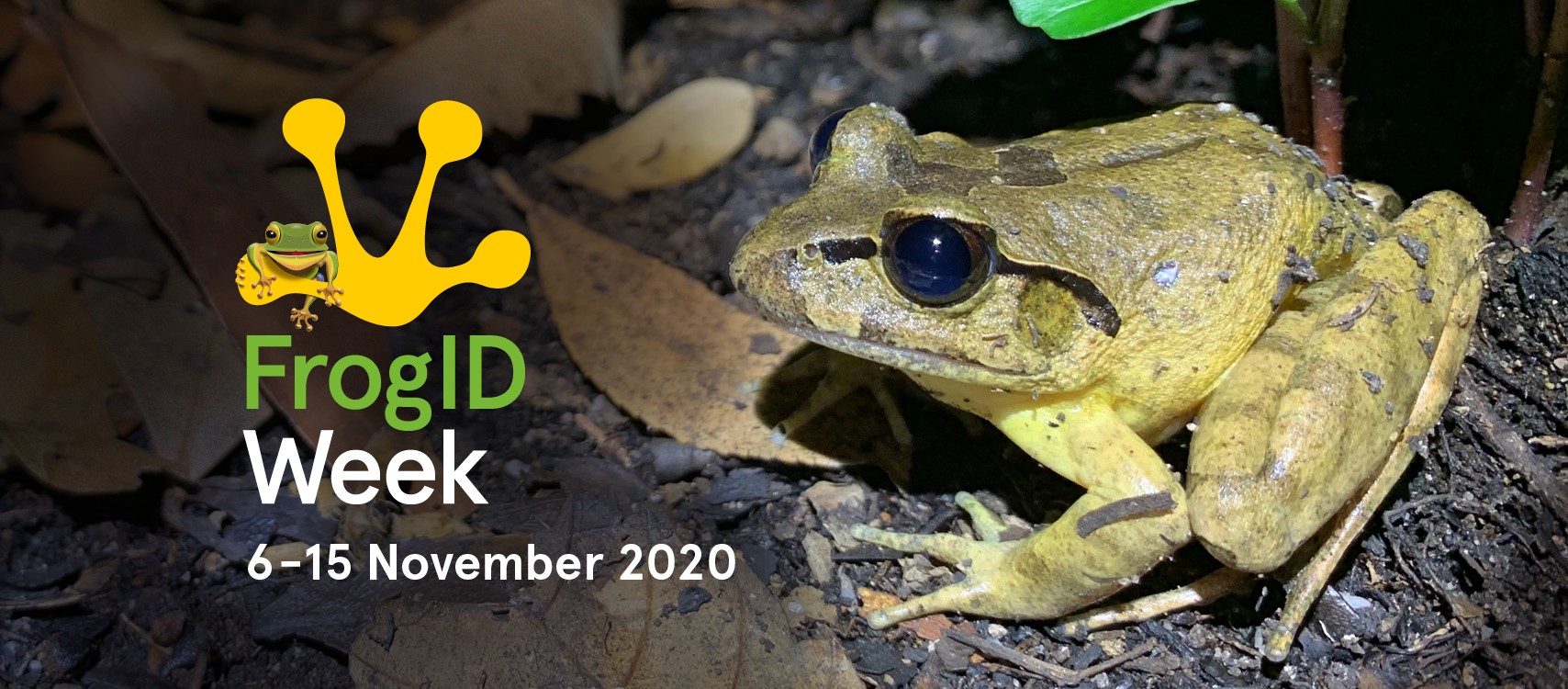

FrogID Week

Can You Help Restore Our Environment? R&R Grants Open

The Serpentine Bilgola Shared Space Consult

- more space for cycling with cycle lanes on the uphill sections of The Serpentine

- a 10 km/h posted speed limit

- planter boxes, pavement paintings and marked parking bays.

Newport - Avalon Pedestrian & Cycle Link Section 1

Newport - Avalon Pedestrian & Cycle Link

- 2.5 meter wide shared path from The Serpentine to Surfside Avenue (originally 3.5 meters wide)

- new path on Surfside Avenue (Eastern side) crossing to the western side and continuing into Avalon Parade

Wild Idea Incubator 2021: Do You Have A Great Idea?

- Majell Backhausen, Simon Harris and Hilary McAllister: For Wild Places

- Georgi and Bruce Ivers: Trees for Australia

- David Flood and Kate Torgernsen: Beyond the Fairway – Golf Embracing Nature

- Mark Gardener: Farm Level Environmental Profit and Loss Reporting

- Aimee Bowman and Holly Newman: Planet Warrior Education

- Camille Goldstone-Henry: Xylo Systems, a collaborative conservation reporting tool.

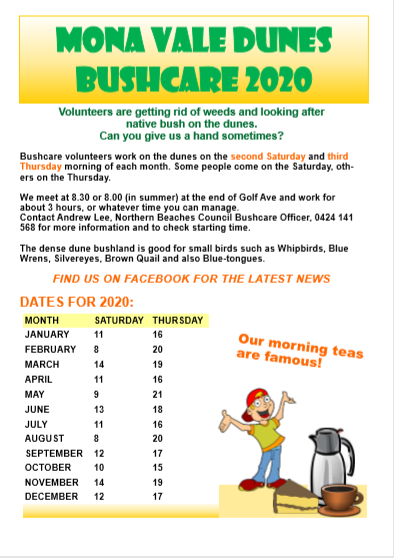

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

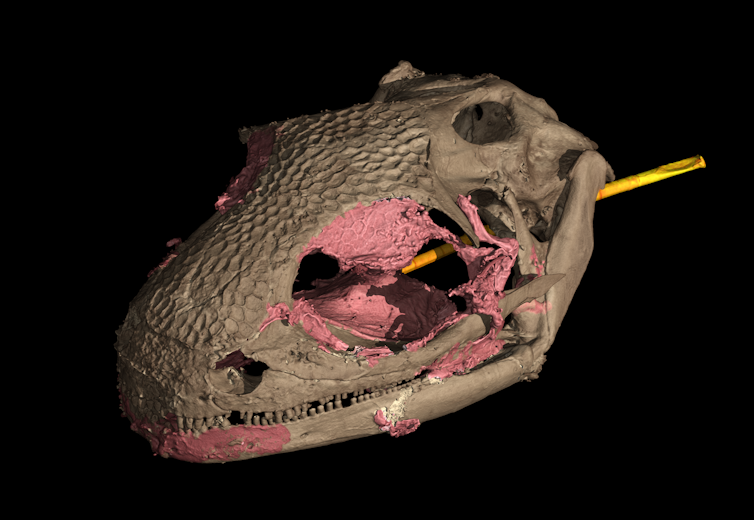

Discovery Triples Greater Glider Species In Australia

November 6, 2020

Australian scientists have discovered one of Australia's best-loved animals is actually three different species.

A team of researchers from James Cook University (JCU), The Australian National University (ANU), the University of Canberra and CSIRO analysed the genetic make-up of the greater glider - a possum-sized marsupial that can glide up to 100 metres.

A team of researchers from James Cook University (JCU), The Australian National University (ANU), the University of Canberra and CSIRO analysed the genetic make-up of the greater glider - a possum-sized marsupial that can glide up to 100 metres.

JCU's PhD student Denise McGregor and Professor Andrew Krockenberger were part of a team that confirmed a long-held theory that the greater glider is actually multiple species.

As a part of her PhD project to understand why greater gliders varied so much across their range, Ms McGregor discovered that the genetic differences between the populations she was looking at were profound.

"There has been speculation for a while that there was more than one species of greater glider, but now we have proof from the DNA. It changes the whole way we think about them," she said.

"Australia's biodiversity just got a lot richer. It's not every day that new mammals are confirmed, let alone two new mammals," Professor Krockenberger said.

"Differences in size and physiology gave us hints that the one accepted species was actually three. For the first time, we were able to use Diversity Arrays (DArT) sequencing to provide genetic support for multiple species."

Greater gliders, much larger than the more well-known sugar gliders, eat only eucalyptus leaves and live in forests along the Great Dividing Range from northern Queensland to southern Victoria. Once common, they are now listed as 'vulnerable', with their numbers declining.

Dr Kara Youngentob, a co-author from ANU, said the identification and classification of species are essential for effective conservation management.

"This year Australia experienced a bushfire season of unprecedented severity, resulting in widespread habitat loss and mortality. As a result, there's been an increased focus on understanding genetic diversity and structure of species to protect resilience in the face of climate change," she said.

"The division of the greater glider into multiple species reduces the previous widespread distribution of the original species, further increasing conservation concern for that animal and highlighting the lack of information about the other greater glider species."

She said there have been alarming declines in greater glider populations in the Blue Mountains, NSW and Central Highlands, Victoria and localised extinctions in other areas.

"The knowledge that there is now genetic support for multiple species, with distributions that are much smaller than the range of the previously recognised single species, should be a consideration in future conservation status decisions and management legislation," Dr Youngentob said.

The research is published in Scientific Reports.

Greater Glider photo by Denise Taylor

An open letter from 1,200 Australian academics on the Djab Wurrung trees

In an open letter, more than 1,200 academics from universities and institutes across Australia have written to the Victorian government to protest against the destruction of Djab Wurrung country as part of a highway duplication in the west of the state.

The letter follows the removal of the Directions Tree last week. The signatories listed below are both Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

We are Australian academics* writing to condemn the destruction of the 350 year-old sacred Djab Wurrung Directions Tree at the hands of the Victorian government. We call on the government to urgently halt works and protect the remaining Djab Wurrung trees and land from destruction.

We are historians, geographers, lawyers, criminologists, sociologists, scientists, anthropologists, social workers, linguists, archaeologists, artists, architects, philosophers, psychologists and other academics from universities around Australia. We have come together in our sorrow and anger at the colonial violence currently being perpetrated by the Victorian government against the Djab Wurrung people, and against all First Nations people in Australia.

While all trees hold value, especially in a climate crisis, the Djab Wurrung trees are so much more than “just trees”; they are living entities with significant historical, cultural and spiritual value and meaning. They are part of an important songline, and have been physically shaped by hundreds of years of First Nations culture and ceremonial practice.

Read more: Churches have legal rights in Australia. Why not sacred trees?

Take the Directions Tree, for example, which was cut down with a chainsaw last week, and carted away unceremoniously on the back of a dump truck. This massive and strikingly beautiful 350-year-old Yellowbox tree with distinctive swirling bark, had been planted as a seed with the placenta from a Djab Wurrung child’s birth and its branches actively shaped and directed over time.

It would have been difficult to look at this tree — to truly bear witness to it — without forever changing the way one understands trees, our interconnectedness with nature, and the strength, depth, beauty and longevity of First Nations culture.

Consider too, the Birthing Tree, also known as a Grandmother Tree, estimated to be 800 years old and currently under imminent threat of destruction. She has a hollow at her base where over 50 generations of Djab Wurrung babies have been born, the fluids from their births merging with the root system and literally becoming part of the tree.

Nearby, and leaning towards it, is the Grandfather Tree, believed to have been planted at the same time and connected via underground root systems. And surrounding them both are hundreds of other significant trees and artefacts, many of which are yet to be formally documented.

The Victorian government’s decision to clear this sacred Djab Wurrung land to make way for a particular version of highway re-routing that will save drivers two minutes travel time, is completely unnecessary. It represents the ongoing violence of our colonial state and its contempt for First Nations culture and people. It makes any talk of a Treaty with First Nations Victorians completely disingenuous.

We, as academics, therefore condemn the cutting down of the Directions Tree and the planned destruction of further sacred trees and artefacts. We condemn the timing of the destruction, under the cover of ongoing COVID rules, preventing defenders from traveling to the site, and under the cover of media and public focus on Melbourne’s long-awaited easing of lockdown.

Read more: What kind of state values a freeway's heritage above the heritage of our oldest living culture?

We condemn the Victorian government’s apparent attempts to create doubt about which tree was destroyed and its significance, and to imply agreements with one group of government-recognised stakeholders amounted to respectful consultation. And we condemn the use of police and security to violently evict the peaceful Djab Wurrung Embassy, which was established by local elders to protect the site.

We urge the Victorian government to take up one of the other options for highway improvements that do not involve further destruction of this significant site, to urgently have these trees recognised as the culturally significant entities they are, and to enable the Djab Wurrung people to continue protecting them for future generations.

*The views expressed in this letter are those of the signatories and not their universities or institutions.![]()

Open Letter Signatories

- Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Indigenous Studies, RMIT University

- Professor Irene Watson, Law, University of SA

- Professor Bronwyn Fredericks, Education and Health, University of Queensland

- Dr Vicki L Couzens, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Gary Foley, History, Victoria University

- Tiriki Onus, Fine Arts and Music, University of Melbourne

- Dr Lou Bennett AM, Social and Political Science, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Chelsea Bond, Social Sciences and Health, University of Queensland

- Alison Whittaker, Law, University of Technology Sydney

- Amanda Porter, Law, University of Queensland

- Kim Kruger, Moondani Balluk Academic Centre, Victoria University

- Professor Bronwyn Carlson, Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University

- Professor Gregory Phillips, Indigenous Health, Griffith University

- Professor Peter Anderson, Education, Queensland University of Technology

- Professor Yin Paradies, Sociology, Deakin University

- Dr Ali Gumillya Baker, Indigenous and Australian Studies, Flinders University

- Associate Professor Leesa Watego, Business, Queensland University of Technology

- Associate Professor Sana Nakata, Political Science, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Sandy O'Sullivan, Indigenous Studies, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Nikki Moodie, Sociology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Sharlene Leroy-Dyer, Aboriginal Studies, University of Queensland

- Dr Anthony McKnight, Education, University of Wollongong

- Dr Summer May Finlay, Public Health, University of Wollongong

- Dr Suzi Hutchings, Anthropology, RMIT University

- Dr Tess Ryan, Leadership and Research Pathways, Australian Catholic University

- Dr Danièle Hromek, Indigenous Design, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Crystal McKinnon, Social and Global Studies, RMIT University

- Dr Jessa Rogers, Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University

- Dr Julia Hurst, Aboriginal History, University of Melbourne

- Aleryk Fricker, Indigenous Education, RMIT University

- Ashley Perry, Indigenous Culture and Visual Art, University of Melbourne

- Brett Biles, Indigenous Health, University of NSW

- Cammi Murrup-Stewart, Aboriginal Wellbeing, Monash University

- Catherine Doe, Indigenous Studies, RMIT University

- Charlotte Franks, Indigenous Education, RMIT University

- Dale Rowland, Psychology, Griffith University

- Dominique Chen, Indigenous Studies, University of Queensland

- Eddie Synot, Law, Griffith University

- Emma Gavin, Indigenous Knowledges, Swinburne University

- Aileen Marwung Walsh, History, Australian National University

- Eugenia Flynn, Literary Studies, Queensland University of Technology

- Holly Charles, Law, RMIT University

- Jacynta Krakouer, Social Work, University of Melbourne

- Jason Brailey, Indigenous Education, RMIT University

- Latoya Rule, Social Work and Social Planning, Flinders University

- Lewis Brown, Indigenous Education, RMIT University

- Luke Williams, Science, RMIT University

- Maddee Clark, Literature, University of Melbourne

- Michael Colbung, Education, University of Adelaide

- Mykaela Saunders, Indigenous Studies, University of Sydney

- Natasha Ward, Indigenous Education and Research, RMIT University

- Nicole Shanahan, Indigenous Education, RMIT University

- Robyn Oxley, Criminology, Western Sydney University

- Stacey Campton, Indigenous Engagement, RMIT University

- Natalie Ironfield, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Neika Lehman, Film and Media, Anthropology, RMIT University

- Dr Aaron Collins, Medicine, University of Melbourne

- Aaron Magro, History, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Abby Mellick Lopes, Design, University of Technology Sydney

- Adam Crowe, Geography, Curtin University

- Adam Spellicy, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Adam Starr, Music, Melbourne Polytechnic

- Associate Professor Adele Wessell, History, Southern Cross University

- Dr Adrian Farrugia, Sociology, La Trobe University

- Agata Pukiewicz, Legal Studies, Australian National University

- Dr Aidan Craney, Anthropology, La Trobe University

- Ainslee Meredith, Conservation, University of Melbourne

- Dr Ainslie Meiklejohn, Humanities, Griffith University

- Aisha Malik, Humanities, University of Sydney

- Emeritus Professor Alan Rumsey, Anthropology, Australian National University

- Associate Professor Alana Lentin, Humanities, Western Sydney University

- Dr Alana Piper, History, University of Technology Sydney

- Alana West, Sociology, University of Technology Sydney

- Professor Alex Broom, Sociology, University of Sydney

- Alex Cain, Philosophy, Monash University

- Dr Alex Gawronski, Art, University of Sydney

- Dr Alex Hansford-Smith, Physiotherapy, University of Melbourne

- Dr Alex Kusmanoff, Conservation, RMIT University

- Dr Alexandra Crosby, Design, University of Technology Sydney

- Alexandra Haschek, Psychology, La Trobe University

- Alexandre da Silva Faustino, Geography, RMIT University

- Alexia Adhikari, Development, University of Adelaide

- Alice Bellette, Literature, Deakin University

- Associate Professor Alice Gaby, Linguistics, Monash University

- Dr Alice Jones, Ecology, University of Adelaide

- Alice Wighton, Anthropology, Australian National University

- Alicia Flynn, Education, University of Melbourne

- Alisa Yuko Bernhard, Musicology, University of Sydney

- Alison Burns, International Studies, Deakin University

- Dr Alison Holland, History, Macquarie University

- Dr Alison Lullfitz, Ethnobiology, University of WA

- Dr Alison Peel, Science, Griffith University

- Alison Winning, Social Science, James Cook University

- Professor Alison Young, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Alissa Flatley, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Alissa Macoun, Politics, Queensland University of Technology

- Professor Alistair McCulloch, Education, University of SA

- Dr Alistair Sisson, Geography, University of NSW

- Allison Larmour, Politics, University of Sydney

- Alys Young, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Alyssa Choat, Design, University of Technology Sydney

- Alyssa Sigamoney, Criminology, RMIT University

- Dr Amal Osman, Health, Flinders University

- Dr Amanda Coles, Employment Relations, Deakin University

- Professor Amanda Kearney, Anthropology, Flinders University

- Dr Amelia Hine, Geography, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Amelia Johns, Media, University of Technology Sydney

- Amélie Scalercio, Fine Arts, Monash University

- Dr Amie O'Shea, Health, Deakin University

- Dr Amy Barrow, Law, Macquarie University

- Dr Amy Carrad, Public Health, University of Wollongong

- Amy Cleland, Social Science, University of SA

- Amy Hampson, Neuroscience, University of Melbourne

- Dr Amy McKernan, Education, University of Melbourne

- Dr Amy McPherson, Education, Australian Catholic University

- Dr Amy Prendergast, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Amy Thomas, Education, University of Technology Sydney

- Amy-Jo Jory, Art, Swinburne University

- Dr Ana Maria Ducasse, Languages, RMIT University

- Ananya Majumdar, Social Science, RMIT University

- Dr Anastasia Kanjere, Humanities, La Trobe University

- Dr Anastasia Powell, Criminology, RMIT University

- Professor Andrea Lamont-Mills, Psychology, University of Southern Queensland

- Professor Andrea Durbach, Law, University of NSW

- Associate Professor Andrea Rizzi, Arts, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Andrew Bonnell, History, University of Queensland

- Dr Andrew Brooks, Humanities, University of NSW

- Associate Professor Andrew Butt, Urban Planning, RMIT University

- Dr Andrew Lapworth, Geography, University of NSW

- Dr Andrew Miller, Art, Flinders University

- Associate Professor Andrew Murphie, Media, University of NSW

- Andrew Murray, Architecture, University of Melbourne

- Professor Andrew Scholey, Psychopharmacology, Swinburne University

- Andrew Treloar, Art, University of Melbourne

- Professor Andrew Vallely, Public Health, University of NSW

- Dr Andrew Whelan, Sociology, University of Wollongong

- Andy Bates, Design, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Andy Kaladelfos, Criminology, University of NSW

- Andy White, Music, Melbourne Polytechnic

- Dr Angela Dean, Environment Studies, Queensland University of Technology

- Associate Professor Angela Kelly-Hanku, Anthropology, University of NSW

- Angela Kintominas, Law, University of NSW

- Angela Osborne, Communication, Deakin University

- Dr Angelika Papadopoulos, Social Work, RMIT University

- Angus Burns, Psychology, Monash University

- Ani Landsu-Ward, Social Science, RMIT University

- Professor Anina Rich, Neuroscience, Macquarie University

- Dr Anita Trezona, Public Health, Deakin University

- Associate Professor Anitra Nelson, Social Science, University of Melbourne

- Anja Dickel, Pharmacy, University of SA

- Dr Anja Kanngieser, Geography, University of Wollongong

- Dr Anna Bowring, Public Health, Burnet Institute

- Anna Dunn, Anthropology, University of Sydney

- Anna Gross, Resources, University of Newcastle

- Dr Anna Hermkens, Anthropology, Macquarie University

- Dr Anna Hopkins, Ecology, Edith Cowan University

- Anna Krohn, Education, University of Melbourne

- Anna Loewendahl, Arts, University of Melbourne

- Anna Nervegna, Architecture, University of Melbourne

- Anna Tweeddale, Architecture, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Anna Willis, Archaeology, James Cook University

- Dr Annalea Beattie, Writing, RMIT University

- Dr Anne Décobert, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Anne Elvey, Theology, Monash University

- Associate Professor Anne Junor, Employment Relations, University of NSW

- Dr Anne Marie Ross, Education, University of Newcastle

- Dr Annette Kroen, Urban Planning, RMIT University

- Dr Annie Delaney, Industrial Relations, RMIT university

- Dr Annie Gowing, Education, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Anthony Hopkins, Law, Australian National University

- Dr Anthony Kent, Social Science, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Anthony Langlois, International Relations, Flinders University

- Anthony Schulx, Music, Melbourne Polytechnic

- Anthony Smith, Sociology, University of NSW

- Antoine Mangion, Education, Australian Catholic University

- Anwar Hossain, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Dr April Reside, Ecology, University of Queensland

- Arden Haar, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Arlo Mountford, Arts, RMIT University

- Dr Ascelin Gordon, Conservation, RMIT University

- Ash Johnstone, Humanities, University of Wollongong

- Ashley Barnwell, Sociology, University of Melbourne

- Ashley Thomson, Anthropology, Australian National University

- Dr Astrida Neimanis, Cultural Studies, University of Sydney

- Badrul Hyder, Urban Studies, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Barbara Kelly, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Dr Barry Morris, Anthropology, Newcastle University

- Associate Professor Bastien Llamas, Evolutionary Genomics, University of Adelaide

- Dr Bek Christensen, Ecology, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Ben Silverstein, History, Australian National University

- Associate Professor Ben Spies-Butcher, Sociology, Macquarie University

- Dr Ben Vezina, Biology, Monash University

- Dr Benjamin Cooke, Geography, RMIT University

- Dr Benjamin Habib, International Relations, La Trobe University

- Dr Benjamin Hegarty, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Bernard Keo, History, Monash University

- Dr Beth Cardier, Communications, Griffith University

- Beth Marsden, History, La Trobe University

- Bethany Kenyon, Social Sciences, RMIT University

- Bethia Burgess, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Betty Luu, Psychology, University of Sydney

- Dr Bianca Fileborn, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Bianca Hennessy, Pacific Studies, Australian National University

- Professor Billie Giles-Corti, Public Health, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Bina Fernandez, Development Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr Bindi Bennett, Social Work, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Blair Williams, Political Science, Australian National University

- Dr Blue Mahy, Education, Monash University

- Professor Bob Hodge, Communication studies, Western Sydney University

- Dr Bonny Cassidy, Writing, RMIT University

- Dr Brian Cuddy, History, Macquarie University

- Dr Bridget Harris, Criminology, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Bridget Lewis, Law, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Brigid Magner, Literature, RMIT University

- Briony Neilson, History, University of Sydney

- Dr Briony Towers, Psychology, RMIT University

- Dr Brodie Evans, Social Justice, Queensland University of Technology

- Bronwyn Ann Sutton, Education, Deakin University

- Dr Bronwyn Cumbo, Education, Monash University

- Dr Brooke Wilmsen, Geography, La Trobe University

- Associate Professor Cai Wilkinson, International Studies, Deakin University

- Professor Callum Morton, Fine Art, Monash University

- Cally Mills, Nursing, Australian Catholic University

- Cameron Coventry, History, Federation University

- Professor Cameron Tonkinwise, Design, University of Technology Sydney

- Dr Can Yalcinkaya, Media, Macquarie University

- Dr Candice Boyd, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Professor Carey Curtis, Planning, Curtin University

- Professor Carla Treloar, Social Science, University of NSW

- Dr Carly Monks, Archaeology, University of WA

- Carmen Jacques, Anthropology, Edith Cowan University

- Carol Que, Arts, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Carol Warren, Anthropology, Murdoch University

- Dr Caroline Mahoney, Education, Deakin University

- Dr Caroline Wake, Theatre, University of NSW

- Carolyn D'Cruz, Gender Studies, La Trobe University

- Dr Carolyn Eskdale, Art, RMIT University

- Professor Carolyn Whitzman, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

- Casey Hosking, Psychology, La Trobe University

- Cat Macleod, Architecture, Melbourne Polytechnic

- Professor Catherine Althaus, Public Administration, University of NSW

- Professor Catherine Greenhill, Mathematics, University of NSW

- Dr Catherine Hartung, Education, Swinburne University

- Dr Catherine Innes Clover, Fine Art, Swinburne University

- Professor Catherine McMahon, Health, Macquarie University

- Dr Catherine Phillips, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Catherine Townsend, Architecture, University of Melbourne

- Catherine Weiss, Philosophy, RMIT University

- Dr Cayne Layton, Ecology, University of Tasmania

- Associate Professor Cecily Maller, Geography, RMIT University

- Dr Chantel Carr, Geography, University of Wollongong

- Charity Edwards, Architecture, Monash University

- Associate Professor Charles Livingstone, Public Health, Monash University

- Dr Charles Robb, Visual Arts, Queensland University of Technology

- Professor Charles Sowerwine, History, University of Melbourne

- Charlie Cooper, Psychology, University of Melbourne

- Charlie Sofo, Visual Art, Monash University

- Charlotte Day, Art, Monash University

- Dr Chin Jou, History, University of Sydney

- Dr Chloe Ward, European Studies, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Chris Healy, Cultural Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr Chris Maylea, Social Work, RMIT University

- Dr Chris Pam, Anthropology, James Cook University

- Dr Chris Peers, Education, Monash University

- Dr Chris Urwin, Archaeology, Monash University

- Christel Antonites, Humanities, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Christina David, Social Work, RMIT University

- Dr Christine Agius, Politics, Swinburne University

- Dr Christo Bester, Neuroscience, University of Melbourne

- Christopher Cordner, Philosophy, University of Melbourne

- Christopher Hallam, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Christopher McCaw, Education, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Christy Newman, Sociology, University of NSW

- Professor Ciaran O'Faircheallaigh, Politics, Griffith University

- Dr Ciemon Caballes, Ecology, James Cook University

- Claire Akhbari, Indigenous Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr Claire Loughnan, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Claire Nettle, Politics, Flinders University

- Dr Claire Spivakovsky, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Clare Cooper, Design, University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Clare Corbould, History, Deakin University

- Dr Clare Land, History, Victoria University

- Clare Rae, Fine Art, University of Melbourne

- Dr Clare Southerton, Sociology, University of NSW

- Dr Clare Weeden, Medicine, University of Melbourne

- Professor Clare Wright, History, La Trobe University

- Dr Claudia Marck, Public Health, University of Melbourne

- Dr Clemence Due, Psychology, University of Adelaide

- Connor Jolley, Geography, RMIT University

- Dr Coralie Boulet, Microbiology, La Trobe University

- Professor Corey Bradshaw, Ecology, Flinders University

- Dr Corrinne Sullivan, Geography, Western Sydney University

- Dr Courtney Babb, Urban Planning, Curtin University

- Dr Courtney Morgans, Ecology, University of Queensland

- Dr Courtney Pedersen, Visual Arts, Queensland University of Technology

- Craig Lyons, Geography, University of Wollongong

- Dr Cristy Clark, Law, University of Canberra

- Dr Crystal Legacy, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

- Dr Cullan Joyce, Philosophy, University of Divinity

- Dr Cynthia Hunter, Anthropology, University of Sydney

- Daisy Bailey, History, Monash University

- Daisy Gibbs, Public Health, University of NSW

- Dr Dallas Rogers, Urbanism, University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Damien Cahill, Politics, University of Sydney

- Dr Dan Golding, Media, Swinburne University

- Dr Daniel Brennan, Philosophy, Bond University

- Dr Daniel Lopez, Philosophy, La Trobe University

- Dr Daniel Ohlsen, Botany, University of Melbourne

- Professor Daniel Palmer, Art, RMIT University

- Daniel Reeders, Regulation and Governance, Australian National University

- Associate Professor Daniel von Sturmer, Fine Art, Monash University

- Dr Daniella Forster, Education, University of Newcastle

- Professor Danielle Celermajer, Sociology, University of Sydney

- Dr Dara Conduit, Politics, Deakin University

- Professor Darryl Jones, Environmental Science, Griffith University

- Dr Dave McDonald, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr David Brophy, History, University of Sydney

- Professor David Carlin, Writing, RMIT University

- Dr David Coombs, Public Policy, University of NSW

- Dr David Hurwood, Ecology, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr David Kelly, Geography, RMIT University

- Dr David Pollock, Politics, RMIT University

- Dr David Ripley, Philosophy, Monash University

- Dr David Rousell, Education, RMIT University

- Emeritus Professor David Rowe, Sociology, Western Sydney University

- Dr David Singh, Sociology, University of Queensland

- Associate Professor David Slucki, Sociology, Monash University

- Dr David Smith, Politics, University of Sydney

- Dr David Spencer, Communication, University of Canberra

- Associate Professor Dawn Darlaston-Jones, Behavioural Science, University of Notre Dame

- Dr Deb Batterham, Social Science, Swinburne University of Technology

- Dr Debbi Long, Anthropology, RMIT University

- Dr Deborah Apthorp, Psychology, University of New England

- Dr Deborah Cleland, Governance, Australian National University

- Deborah Lee-Talbot, History, Deakin University

- Dr Deborah Moore, Education, Deakin University

- Dr Debra McDougall, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Declan Martin, Urban Planning, Monash University

- Professor Deirdre Coleman, English, University of Melbourne

- Dr Deirdre Hayes, Australian Studies, University of SA

- Professor Devleena Ghosh, Social Science, University of Technology Sydney

- Dr Diana Johns, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Diana Shahinyan, English, Sydney University

- Dimity Hawkins, History, Swinburne University

- Dion Tuckwell, Design, Monash University

- Dr Dolly Kikon, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Dominic De Nardo, Medicine, Monash University

- Dr Dominique Moritz, Law, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Dominique Potvin, Ecology, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Associate Professor Donna Houston, Geography, Macquarie University

- Dr Duc Dau, Humanities, University of WA

- Dr Eden Smith, History, University of Melbourne

- Dr Eduardo Jordan, Journalism, Griffith University

- Dr Effie Karageorgos, History, University of Newcastle

- Dr Elena Benthaus, Humanities, Deakin University

- Dr Elena Prieto, Education, University of Newcastle

- Elena Tjandra, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Elese Dowden, Philosophy, University of Queensland

- Dr Elise Klein, Public Policy, Australian National University

- Dr Elizabeth Branigan, Anthropology, La Trobe University

- Elizabeth Culhane, Philosophy, University of Queensland

- Elizabeth Duncan, Geography, Sydney University

- Elizabeth King, English, Macquarie University

- Dr Elizabeth Orr, Social Work, University of Melbourne

- Professor Elizabeth Povinelli, Anthropology, Charles Darwin University

- Dr Elke Emerald, Education, Griffith University

- Ellen Corrick, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Elliot Gould, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Ellyse Fenton, Politics, University of Queensland

- Dr Emily Brayshaw, History, University of Technology Sydney

- Emily Corbett, Gender Studies, La Trobe University

- Dr Emily Gray, Education, RMIT University

- Emily McColl-Gausden, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Emily Miller, Justice Studies, University of SA

- Emily Miller, Archaeology, Griffith University

- Dr Emily O'Gorman, Geography, Macquarie University

- Associate Professor Emily Potter, Literature, Deakin University

- Dr Emily Rugel, Epidemiology, University of Sydney

- Emily Toome, Social Sciences, RMIT University

- Dr Emily van der Nagel, Communication, Monash University

- Emma Barnes, Social Science, University of NSW

- Dr Emma Colvin, Criminology, Charles Sturt University

- Emma George, Occupational Therapy, University of Adelaide

- Professor Emma Kowal, Anthropology, Deakin University

- Dr Emma Rehn, Environmental Science, James Cook University

- Dr Emma Robertson, History, La Trobe University

- Dr Emma Russell, Legal Studies, La Trobe University

- Dr Emma Whatman, Gender Studies, Deakin University

- Emmalee Ford, Biochemistry, University of Newcastle

- Emmeline Kildea, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Emmett Stinson, Literature, Deakin University

- Epperly Zhang, Translation and Interpreting, RMIT University

- Dr Erica Millar, Legal Studies, La Trobe University

- Professor Erik Eklund, History, Federation University

- Dr Erin Fitz-Henry, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Erin O'Donnell, Law, University of Melbourne

- Erina McCann, Conservation, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Euan Ritchie, Ecology, Deakin University

- Associate Professor Eva Alisic, Social Science, University of Melbourne

- Dr Eve Mayes, Education, Deakin University

- Dr Eve Vincent, Anthropology, Macquarie University

- Dr Ewan McDonald, Nursing, La Trobe University

- Dr Fabian Kong, Epidemiology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Faith Valencia-Forrester, Education, Griffith University

- Felicia Jaremus, Education, University of Newcastle

- Felicity Gray, Governance, Australian National University

- Associate Professor Felicity Meakins, Linguistics, University of Queensland

- Fernanda Quilici Mola, Fashion, RMIT University

- Fernanda Soares, International Relations, RMIT University

- Dr Fincina Hopgood, Screen Studies, University of New England

- Dr Fiona Cameron, Heritage studies, Western Sydney University

- Professor Fiona Haines, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Fiona Lee, English, University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Fiona Miller, Geography, Macquarie University

- Professor Fiona Paisley, History, Griffith University

- Professor Fiona Probyn-Rapsey, Humanities, University of Wollongong

- Fran van Riemsdyk, Fine Art, RMIT University

- Dr Francesca Dominello, Law, Macquarie University

- Dr Francis Markham, Geography, Australian National University

- Dr Freya Higgins-Desbiolles, Tourism, University of SA

- Freya McLachlan, Justice, Queensland University of Technology

- Freya Scott, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Gabriel Caluzzi, Public Health, La Trobe University

- Dr Gabriel da Silva, Engineering, University of Melbourne

- Gabriela Franich, Criminology, RMIT University

- Dr Garrity Hill, Sociology, Swinburne University

- Dr Gemma Hamilton, Criminology, RMIT University

- Dr Geoff Browne, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

- Dr Geoffrey Brown, Humanities, La Trobe University

- Emeritus Professor Geoffrey Samuel, Anthropology, University of Sydney

- George Burdon, Geography, University of NSW

- Dr George Dertadian, Criminology, University of NSW

- George Hatvani, Social Sciences, Swinburne University

- Associate Professor George Newhouse, Law, Macquarie University

- Georgia Carr, Linguistics, University of Sydney

- Dr Georgia Garrard, Conservation, RMIT University

- Dr Gerald Roche, Anthropology, La Trobe University

- Gerard Ryan, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Gerlinde Koeglreiter, Information Systems, Australian National University

- Gerry McLoughlin, eUrbanism, Swinburne University

- Professor Ghassan Hage, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Gilad Bino, Science, University of NSW

- Dr Giles Fielke, Art History, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Gillian Kidman, Education, Monash University

- Professor Gillian Wigglesworth, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Giselle Newton, Sociology, University of NSW

- Gisselle Vila Benites, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Giulia Torello-Hill, Languages, University of New England

- Dr Glenda Mejia, Global Studies, RMIT University

- Glenn Abblitt, Education, RMIT University

- Dr Glenn Althor, Environmental Science, Australian National University

- Dr Graham Fulton, Biology, University of Queensland

- Associate Professor Grant Hamilton, Ecology, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Greg Giannis, Education, La Trobe University

- Professor Greg Hainge, Languages, University of Queensland

- Professor Greg Restall, Philosophy, University of Melbourne

- Guy Webster, Literature, University of Melbourne

- Dr Hanna Torsh, Linguistics, Macquarie University

- Dr Hannah McCann, Cultural Studies, University of Melbourne

- Hannah Reardon-Smith, Music, Griffith University

- Dr Hannah Robert, Law, La Trobe University

- Hannah Weeramanthri, Social Work, University of Melbourne

- Hanne Worsoe, Anthropology, University of Queensland

- Associate Professor Hans Baer, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Haripriya Rangan, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Harriette Richards, Cultural Studies, University of Melbourne

- Harrison Spratling, Education, Deakin University

- Adjunct Professor Hartmut Fünfgeld, Geography, RMIT University

- Hayden Moon, Theatre, Sydney University

- Dr Hayley Henderson, Urban Planning, Australian National University

- Dr Heather Francis, Neuropsychology, Macquarie University

- Heather Jarvis, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Helen Corney, Urban Studies, RMIT University

- Professor Helen Dickinson, Public Administration, University of NSW

- Dr Helen Grimmett, Education, Monash University

- Dr Helen Johnson, Fine Art, Monash University

- Dr Helen Keane, Sociology, Australian National University

- Dr Helen Mayfield, Conservation, University of Queensland

- Dr Helen Ngo, Philosophy, Deakin University

- Dr Helen Pringle, Politics, University of NSW

- Helen Rowe, Urban Policy, RMIT University

- Helen South, Education, Charles Sturt University

- Helen Taylor, Management, University of Technology Sydney

- Dr Henk Huijser, Education, Queensland University of Technology

- Hiranya Anderson, Health, Macquarie University

- Dr Hoda Afshar, Humanities, University of Melbourne

- Dr Holly Doel-Mckaway, Law, Macquarie Law School

- Associate Professor Holly High, Anthropology, University of Sydney

- Dr Holly Sitters, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Holly Smith, Palaeontology, Griffith University

- Dr Honni van Rijswijk, Law, University of Technology Sydney

- Dr Hugh Davies, Ecology, Charles Darwin University

- Professor Hugh Possingham, Ecology, University of Queensland

- Dr Ibolya Losoncz, Governance, Australian National University

- Associate Professor Ilana Mushin, Linguistics, University of Queensland

- Dr Imogen Bell, Mental health, University of Melbourne

- Imogen Carr, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Imogen Richards, Criminology, Deakin University

- Dr Indigo Willing, Sociology, Griffith University

- Associate Professor Iris Duhn, Education, Monash University

- Dr Iris Levin, Urban Planning, Swinburne University

- Isabel Mudford, Sociology, Australian National University

- Dr Isabel O'Keeffe, Linguistics, University of Sydney

- Isabella Capezio, Photography, RMIT University

- Isabella Saunders, Social science, University of NSW

- Ishita Chatterjee, Architecture, University of Melbourne

- Ivy Scurr, Anthropology, University of Newcastle

- Associate Professor Jaap Timmer, Anthropology, Macquarie University

- Dr Jack Noone, Psychology, University of NSW

- Jackson Holloway, Philosophy, La Trobe University

- Jaclyn Hopkins, History, La Trobe University

- Dr Jacqueline Bradley, Visual Arts, National Art School

- Dr Jacqueline Gothe, Design, University of Technology Sydney

- Dr Jacqui Shelton, Fine Art, Monash University

- Dr Jacquie Tinkler, Education, Charles Sturt University

- Professor Jago Dodson, Urban Policy, RMIT University

- Dr Jamee Newland, Health, University of NSW

- James Barker, Ecology, University of Wollongong

- James Blackwell, Politics, University of NSW

- Dr James Bradley, History, University of Melbourne

- Dr James Cleverley, Cultural Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr James Dunk, History, University of Sydney

- Dr James Findlay, History, University of Sydney

- Dr James Flexner, Archaeology, University of Sydney

- Dr James Lesh, Heritage Studies, University of Melbourne

- Professor James McCaw, Science, University of Melbourne

- James Meese, Communications, RMIT University

- Associate Professor James Oliver, Design, RMIT University

- Dr James Radford, Ecology, La Trobe University

- James Upjohn, Science, Monash University

- Dr Jan-Hendrik, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jane Carey, History, University of Wollongong

- Professor Jane Wilkinson, Education, Monash University

- Associate Professor Janet Hunt, Development Studies, Australian National University

- Associate Professor Janet Stanley, Interdisciplinary, University of Melbourne

- Janice Wright, Social Sciences, University of Wollongong

- Janine Gertz, Sociology, James Cook University

- Jannett Nieves, Social Studies, RMIT University

- Dr Jarrod Hore, History, University of NSW

- Jasmin McAleer, Archaeology, Australian National University

- Dr Jasmine Westendorf, Politics, La Trobe University

- Rev/Dr Jason Goroncy, Theology, University of Divinity

- Javed Anwar, Education, RMIT University

- Professor Javier Alvarez-Mon, Archaeology, Macquarie University

- Dr Jay Daniel Thompson, Communications, RMIT University

- Dr Jaye Early, Art, University of SA

- Jaye Hayes, Arts Therapy, MIECAT Institute

- Dr Jayne Rantall, History, La Trobe University

- Professor Jayne White, Education, RMIT University

- Dr Jayne Wilkins, Archaeology, Griffith University

- Dr Jaz Hee-jeong Choi, Design, RMIT University

- Professor Jeanette Kennett, Philosophy, Macquarie University

- Jeanine Hourani, Public Health, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jeannette Walsh, Social work, University of Wollongong

- Associate Professor Jeannie Rea, Planetary Health, Victoria University

- Associate Professor Jeff Babon, Biologist, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

- Jen Hocking, Midwifery, Australian Catholic University

- Dr Jen Martin, Science, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jenna Mead, English, University of WA

- Jenna Mikus, Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Jennifer Audsley, Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Jennifer Balint, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Jennifer Biddle, Visual Anthropology, University of NSW

- Dr Jennifer Bleazby, Education, Monash University

- Jennifer Campbell, Engineering, Griffith University

- Dr Jennifer Caruso, History, University of Adelaide

- Dr Jennifer Dowling, Languages, University of Sydney

- Professor Jennifer Firn, Ecology, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Jennifer McConachy, Social Work, University of Melbourne

- Jennifer Newsome, Musicology, Australian National University

- Dr Jennifer Seevinck, Design, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Jennifer Silcock, Ecology, University of Queensland

- Jennifer Witheridge, Urban Studies, Swinburne University

- Dr Jeremiah Brown, Financial Wellbeing, University of NSW

- Jeremy Eaton, Visual Art, University of Melbourne

- Jeremy Gay, Social Science, RMIT University

- Dr Jess Coyle, Indigenous Australian Studies, Charles Sturt University

- Jess Hardley, Media, Murdoch University

- Dr Jess Reeves, Environmental Science, Federation University

- Dr Jessica Birnie-Smith, Linguistics, La Trobe University

- Dr Jessica Campbell, Speech Pathology, University of Queensland

- Dr Jessica Edwards, Health, University of Adelaide

- Dr Jessica Gannaway, Languages, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jessica Gerrard, Education, University of Melbourne

- Jessica Gibbs, Archaeology, University of Queensland

- Dr Jessica Hazel Horton, History, La Trobe University

- Dr Jessica Kean, Gender Studies, University of Sydney

- Jessica Lea Dunn, Design, University of Sydney

- Dr Jessica Manousakis, Neuroscience, Monash University

- Dr Jessica Megarry, Political Science, University of Melbourne

- Jessica Priemus, Design, Curtin University

- Dr Jessica Roberts, Ecology, Monash University

- Associate Professor Jessica Wilkinson, Creative Writing, RMIT University

- Dr Jessie Wells, Environmental Science, University of Queensland

- Jidde Jacobi, Cognitive Sciences, Macquarie University

- Dr Jill Fielding-Wells, Education, Australian Catholic University

- Jill Pope, Anthropology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jill Vaughan, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jillian Healy, Biological Science, Deakin University

- Dr Jing Qi, Education, RMIT University

- Jo Grant, Medical Anthropology, University of Newcastle

- Dr Joanna Cruickshank, History, Deakin University

- Dr Joanna Kyriakakis, Law, Monash University

- Dr Joanne Dawson, Astronomy, Macquarie University

- Dr Joanne Faulkner, Cultural Studies, Macquarie University

- Dr Joanne Quick, Languages, Deakin University

- Dr Joanne Watson, Disability and Inclusion, Deakin University

- Jocelyn Bosse, Law, University of Queensland

- Dr Jodi McAlister, Writing, Deakin University

- Dr Joe Fontaine, Environmental Science, Murdoch University

- Dr Joe Hurley, Urban Planning, RMIT University

- Joe MacFarlane, Criminology, RMIT University

- Dr Joel Barnes, History, University of Technology Sydney

- Dr John Cox, Anthropology, La Trobe University

- John Cumming, Creative Arts, Deakin University

- Professor John Frow, English, University of Sydney

- Professor John Langmore, Politics, University of Melbourne

- Professor John Sinclair, Sociology, University of Melbourne

- Dr John Taylor, Anthropology, La Trobe University

- Professor Jon Barnett, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jon Roffe, Philosophy, Melbourne School of Continental Philosophy

- Jonas Ropponen, Fine Art, Monash University

- Dr Jonathan Dimond, Arts, Melbourne Polytechnic

- Dr Jonathan Symons, Politics, Macquarie University

- Dr Joni Meenagh, Criminology, RMIT University

- Jordan Hinton, Psychology, Australian Catholic University

- Dr Jordana Silverstein, History, La Trobe University

- Professor Joseph Pugliese, Cultural Studies, Macquarie University

- Dr Josephine Browne, Sociology, Griffith University

- Joshua Badge, Philosophy, Deakin University

- Joshua Hernandez, Philosophy, La Trobe University

- Joshua Hodges, Ecology, Charles Sturt University

- Dr Jovana Mastilovic, Law, Griffith University

- Judy Annear, Art History, University of Melbourne

- Dr Judy Bush, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

- Dr Judy Taylor, Health, James Cook University

- Dr Julia Dehm, Law, La Trobe University

- Julia Hartelius, International Studies, RMIT University

- Julia Lane, Cultural Studies, Edith Cowan University

- Julian Aubrey Smith, Fine Arts, RMIT University

- Julian McKinlay King, Political Science, University of Wollongong

- Dr Julie Dean, Health, University of Queensland

- Professor Julie Fitness, Psychology, Macquarie University

- Dr Julie Healer, Science, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

- Dr Julie Kimber, Politics, Swinburne University of Technology

- Dr Julie Moreau, Biology, Monash University

- Associate Professor Julie Rudner, Community Development, La Trobe University

- Juliet Gunning, Performing Arts, Swinburne University

- Associate Professor Juliet Rogers, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Jumana Bayeh, Arts, Macquarie University

- Dr June Rubis, Geography, University of Sydney

- Justin McCulloch, Geography, University of SA

- Dr Justine Shih Pearson, Literature, University of Sydney

- Jutta Beher, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Kai Tanter, Philosophy, University of Melbourne

- Professor Kama Maclean, History, University of NSW

- Professor Kane Race, Humanities, University of Sydney

- Kara Sandri, Social Science, RMIT University

- Karen Carlisle, Health, James Cook University

- Dr Karen Cheer, Health, James Cook University

- Dr Karen Crawley, Law, Griffith University

- Associate Professor Karen Jones, Philosophy, University of Melbourne

- Dr Karen Marangio, Education, Monash University

- Professor Karen Trimmer, Education, University of Southern Queensland

- Dr Kari Lancaster, Social Science, University of NSW

- Karly Cini, Health, University of Melbourne

- Dr Kassel Hingee, Statistics, Australian National University

- Kate Barber, Art, Monash University

- Kate Brody, Medicine, University of Melbourne

- Kate Clark, Cultural Studies, Monash University

- Dr Kate Davison, History, University of Melbourne

- Dr Kate Dooley, Political science, University of Melbourne

- Dr Kate Helmstedt, Mathematics, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Kate Howell, Food Systems, University of Melbourne

- Kate Hume, Environmental Sciences, University of Melbourne

- Dr Kate Johnston-Ataata, Sociology, RMIT University

- Dr Kate Just, Art, University of Melbourne

- Dr Kate O'Connor, Education, La Trobe University

- Professor Kate Sweetapple, Design, University of Technology Sydney

- Associate Professor Kate Thompson, Education, Queensland University of Technology

- Kate Toone, Social work, Flinders University

- Dr Kate Young, Public Health, Queensland University of Technology

- Katerina Kokkinos-Kennedy, Performing Arts, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Katerina Teaiwa, Pacific Studies, Australian National University

- Professor Kath Gelber, Political Science, University of Queensland

- Katherine Berthon, Ecology, RMIT University

- Dr Katherine Curchin, Public Policy, Australian National University

- Associate Professor Katherine Ellinghaus, History, La Trobe University

- Dr Katherine Giljohann, Science, University of Melbourne

- Professor Katherine Johnson, Community Psychology, RMIT University

- Dr Kathleen Aikens, Education, Monash University

- Dr Kathleen Flanagan, Sociology, University of Tasmania

- Dr Kathleen Neal, History, Monash University

- Kathleen Pleasants, Education, La Trobe University

- Kathleen Smithers, Education, University of Newcastle

- Dr Kathleen Tait, Education, Macquarie University

- Dr Kathryn Coleman, Visual Art, University of Melbourne

- Kathryn Knights, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Kathryn Reardon-Smith, Ecology, University of Southern Queensland

- Dr Kathryn Sellick, Social Work, University of Melbourne

- Professor Kathryn Williams, Psychology, University of Melbourne

- Professor Kathy Bowrey, Law, University of NSW

- Associate Professor Katie Barclay, History, University of Adelaide

- Professor Katie Holmes, History, La Trobe University

- Dr Katie O'Bryan, Law, Monash University

- Dr Katie Woolaston, Law, Queensland University of Technology

- Katitza Marinkovic, Health, University of Melbourne

- Katrin Koenning, Visual Art, RMIT University

- Dr Katrina Raynor, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

- Kavita Gonsalves, Urban Studies, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Kaya Barry, Geography, Griffith University

- Keagan Ó Guaire, Social Science, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Keely Macarow, Art, RMIT University

- Dr Keith Armstrong, Visual Arts, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Kelly Donati, Food studies, William Angliss Institute

- Dr Kelly Gardiner, English, La Trobe University

- Dr Kelly Hussey-Smith, Art, RMIT University

- Dr Kelsie Long, Palaeoenvironments, Australian National University

- Dr Kerrie Saville, Management, Deakin University

- Dr Kerryn Drysdale, Health, University of NSW

- Dr Kevin Lowe, Education, University of NSW

- Kia Zand, Art, University of Melbourne

- Kieran Stevenson, Writing, Deakin University

- Dr Kim Davies, Education, Deakin University

- Kim Newman, Archaeology, Griffith University

- Kimberley de la Motte, Science, University of Queensland

- Dr Kirrily Jordan, Politics, Australian National University

- Dr Kirsten Small, Health, Griffith University

- Kirstin Kreyscher, Humanities, Deakin University

- Kirsty Howey, Cultural Studies, University of Sydney

- Kris Vine, Health, James Cook University

- Dr Kristal Cain, Biology, Australian National University

- Kristen Bell, Urban Planning, RMIT University

- Kristina Tsoulis-Reay, Fine Art, Monash University

- Associate Professor Kurt Iveson, Geography, University of Sydney

- Dr Kyle Harvey, History, University of Tasmania

- Associate Professor Kym Rae, Indigenous Health, University of Queensland

- Kymberly Louise, Disability Studies, Flinders University

- Dr Lana Hartwig, Geography, Griffith University

- Lanie Stockman, Social Policy, RMIT University

- Dr Lara Palombo, Cultural Studies, Macquarie University

- Dr Laresa Kosloff, Art, RMIT University

- Larissa Fogden, Social Work, University of Melbourne

- Dr Larissa Sandy, Criminology, RMIT University

- Dr Laura Alfrey, Education, Monash University

- Dr Laura Henderson, Cultural Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr Lauren Gawne, Linguistics, La Trobe University

- Lauren Gower, Fine Art, University of Melbourne

- Dr Lauren Istvandity, Cultural Studies, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Lauren Pikó, History, University of Melbourne

- Dr Leah Barclay, Design, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Leah Lui-Chivizhe, History, University of Sydney

- Dr Leah Williams Veazey, Sociology, University of Sydney

- Dr Leanne Morrison, Accounting, RMIT University

- Lee Valentine, Health, University of Melbourne

- Dr Lenise Prater, Literary Studies, Monash University

- Lenka Thompson, Social Science, University of Technology Sydney

- Leonetta Leopardi, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Dr Leonie Brialey, Creative Writing, University of Melbourne

- Professor Lesley Head, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Professor Lesley Hughes, Ecology, Macquarie University

- Professor Lesley Stirling, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Dr Leslie Eastman, Fine Art, RMIT University

- Dr Leslie Roberson, Conservation, University of Queensland

- Letitia Robertson, Finance, University of Southern Queensland

- Dr Lew Zipin, Education, Victoria University

- Dr Liam Ward, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Libby Kruse, Medical Biology, University of Melbourne

- Professor Libby Porter, Urban Planning, RMIT University

- Dr Ligia Lopez Lopez, Education, University of Melbourne

- Dr Lila Moosad, Public Health, University of Melbourne

- Lina Koleilat, Ethnography, Australian National University

- Lindall Kidd, Ecology, RMIT University

- Dr Lindy Orthia, Science Communication, Australian National University

- Dr Lisa Carson, Politics, University of NSW

- Lisa de Kleyn, Social Science, RMIT University

- Dr Lisa Hunter, Education, Monash University

- Lisa Siegel, Education, Southern Cross University

- Lisa Theiler, Anthropology, La Trobe University

- Dr Lisa Vallely, Public Health, University of NSW

- Associate Professor Lisa Wynn, Anthropology, Macquarie University

- Dr Liz Barber, Public Health, University of SA

- Dr Liz Brogden, Architecture, Queensland University of Technology

- Associate Professor Liz Conor, History, La Trobe University

- Liz Dearn, Mental Health, RMIT University

- Liz McGrath, Social Work, RMIT University

- Dr Lizzil Gay, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Llewellyn Wishart, Education, Deakin University

- Dr Lloyd White, Anatomy, La Trobe University

- Dr Lobna Yassine, Social Work, Australian Catholic University

- Professor Lorana Bartels, Criminology, Australian National University

- Loretta Bellato, Social Sciences, Swinburne University

- Dr Lorna Peters, Psychology, Macquarie University

- Dr Louisa Willoughby, Linguistics, Monash University

- Professor Louise D'Arcens, English, Macquarie University

- Dr Louise Dorignon, Geography, RMIT University

- Louise Weaver, Fine Art, RMIT University

- Lu Lin, Cultural Studies, RMIT University

- Luara Karlson, English, University of Melbourne

- Dr Luci Pangrazio, Education, Deakin University

- Lucinda Strahan, Writing, RMIT University

- Dr Lucy Buzacott, Arts, University of Melbourne

- Dr Lucy Gunn, Urban Studies, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Lucy Nicholas, Sociology, Western Sydney University

- Dr Lucy Van, Literature, University of Melbourne

- Dr Luigi Gussago, Languages, La Trobe University

- Professor Luke McNamara, Law, University of NSW

- Luke Stafford, Biology, La Trobe University

- Lydia Pearson, Fashion, Queensland University of Technology

- Lyndall Murray, Cognitive Science, Macquarie University

- Professor Lyndsey Nickels, Cognitive Science, Macquarie University

- Dr Lyrian Daniel, Architecture, University of Adelaide

- Madeline Dans, Biomedics, Burnet Institute

- Dr Madeline Mitchell, Plant Sciences, RMIT University

- Madeline Taylor, Design, University of Melbourne

- Dr Maia Gunn Watkinson, Cultural Studies, University of NSW

- Dr Maia Raymundo, Ecology, James Cook University

- Dr Mandy Truong, Public Health, Monash University

- Dr Marc Mierowsky, English, University of Melbourne

- Dr Marc Pruyn, Education, Monash University

- Dr Marcelo Svirsky, Politics, University of Wollongong

- Marco Gutierrez, Environmental Policy, RMIT University

- Dr Marcus Banks, Economics, RMIT University

- Professor Marcus Foth, Design, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Maree Pardy, International Studies, Deakin University

- Margareta Windisch, Social Work, RMIT University

- Dr Margot Ford, Education, University of Newcastle

- Dr Maria Giannacopoulos, Law, Flinders University

- Dr Maria Karidakis, Linguistics, The University Of Melbourne

- Maria Korochkina, Cognitive Science, Macquarie University

- Dr Mariana Dias Baptista, Forest Science, RMIT University

- Professor Marie Brennan, Education, University of SA

- Dr Mariko Smith, Museum Studies, University of Sydney

- Marita McGuirk, Ecologist, University of Melbourne

- Dr Mark Bahnisch, Sociology, International College of Management

- Associate Professor Mark Kelly, Philosophy, Western Sydney University

- Mark Parfitt, Humanities, Curtin University

- Dr Mark Shorter, Fine Arts, University of Melbourne

- Dr Markela Panegyres, Visual Arts, University of Sydney

- Dr Marnee Watkins, Education, University of Melbourne

- Dr Marnie Badham, Creative Arts, RMIT University

- Dr Martin Breed, Ecology, Flinders University

- Associate Professor Martin Porr, Archaeology, University of WA

- Professor Mary Lou Rasmussen, Sociology, Australian National University

- Dr Mary Tomsic, History, Australian Catholic University

- Dr Mathew Abbott, Philosophy, Federation University

- Matt Novacevski, Planning, University of Melbourne

- Dr Matthew Champion, History, Australian Catholic University

- Professor Matthew Fitzpatrick, History, Flinders University

- Dr Matthew Harrison, Education, Melbourne Graduate School of Education

- Matthew Mitchell, Criminology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Matthew Selinske, Conservation, RMIT University

- Dr Max Kaiser, History, University of Melbourne

- Dr Meagan Dewar, Biology, Federation University

- Dr Meagan Tyler, Industrial Relations, RMIT University

- Professor Meaghan Morris, Cultural Studies, University of Sydney

- Dr Meera Varadharajan, Education, University of NSW

- Dr Meg Foster, History, University of NSW

- Dr Megan Evans, Environmental Policy, University of NSW

- Dr Megan Good, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Megan McPherson, Creative Arts, University of Melbourne

- Megan Tighe, Politics, University of Tasmania

- Dr Megan Weier, Social Policy, University of NSW

- Mel Campbell, Media, University of Melbourne

- Melanie Ashe, Media, Monash University

- Dr Melanie Baak, Education, University of SA

- Dr Melanie Davern, Public Health, RMIT University

- Dr Melinda Mann, Education, Central Queensland University

- Dr Melissa Hardie, English, University of Sydney

- Professor Melissa Haswell, Health, University of Sydney

- Melissa Laing, Social work, RMIT University

- Dr Melissa Lovell, Political Science, Australian National University

- Dr Melissa Neave, Urban Planning, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Melissa Norberg, Psychology, Macquarie University

- Dr Melissa Wolfe, Education, Monash University

- Mercedes Zanker, Philosophy, La Trobe University

- Dr Meredith Turnbull, Fine Art, Monash University

- Dr Mia Martin Hobbs, History, University of Melbourne

- Dr Micaela Pattison, History, University of Sydney

- Dr Micaela Sahhar, Palestine Studies, University of Melbourne

- Michael Bojkowski, Communications, RMIT University

- Dr Michael Callaghan, Ethics, Deakin University

- Professor Michael Gard, Human Movement, University of Queensland

- Dr Michael Griffiths, English, University of Wollongong

- Michael Julian, Indigenous Arts, University of Melbourne

- Professor Michael McCarthy, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Michael McNally, Education, University of Queensland

- Michael Pearson, History, Australian Catholic University

- Dr Michael Richardson, Cultural Studies, University of NSW

- Dr Michael Savic, Sociology, Monash University

- Professor Michael Stumpf, Biology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Michal Glikson, Visual Arts, Charles Darwin University

- Michel Gerencir, Visual Language, Griffith Film School

- Professor Michele Acuto, Politics, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Michele Ruyters, Legal Studies, RMIT University

- Professor Michelle Arrow, History, Macquarie University

- Dr Michelle Carmody, Latin American Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr Michelle Langley, Archaeology, Griffith University

- Dr Michelle Ludecke, Education, Monash University

- Dr Michelle Redman-MacLaren, Public Health, James Cook University

- Michelle Toy, Law, University of Technology Sydney

- Professor Miguel Vatter, Politics, Flinders University

- Dr Mike Jones, History, Australian National University

- Dr Millicent Churcher, Philosophy, University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Miranda Forsyth, Law, Australian National University

- Dr Miranda Smith, Infectious Diseases, University of Melbourne

- Dr Miri Forbes, Psychology, Macquarie University

- Mittul Vahanvati, Urban Planning, RMIT University

- Dr Moira Williams, Biology, University of Sydney

- Dr Monica Barratt, Social Sciences, RMIT University

- Dr Monica Behrend, Research Education, University of SA

- Dr Monica Campo, Sociology, University of Melbourne

- Monica Sestito, Italian Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr Monika Barthwal-Datta, International Relations, University of NSW

- Monique Moffa, Criminology, RMIT University

- Dr Morgan Harrington, Anthropology, Australian National University

- Dr Morgan Tear, Psychology, Monash University

- Morganna Magee, Design, Swinburne University

- Muhammad Ali, Education, University of Queensland

- Dr Nadia Rhook, Indigenous Studies, University of WA

- Nahum McLean, Design, University of Technology Sydney

- Naimah Talib, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Professor Nan Seuffert, Law, University of Wollongong

- Dr Naomi Indigp, Science, University of Queensland

- Dr Naomi Parry, History, University of Tasmania

- Dr Natalie Hendry, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Natalie Osborne, Geography, Griffith University

- Dr Natalya Turkina, Business, RMIT University

- Natasha Cadenhead, Conservation, University of Melbourne

- Natasha Heenan, Politics, University of Sydney

- Dr Natasha Pauli, Geography, University of WA

- Natasha Ufer, Ecology, University of Queensland

- Dr Nathalie Butt, Ecology, University of Queensland

- Nathan Pittman, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

- Dr Neil Maclean, Anthropology, University of Sydney

- Nicholas Carson, Sociology, RMIT University

- Dr Nicholas Hill, Sociology, RMIT University

- Dr Nicholas Mangan, Fine Art, Monash University

- Nicholas Ross, Politics, Australian National University

- Dr Nicholas Tochka, Music, University of Melbourne

- Dr Nick Brancazio, Philosophy, University of Wollongong

- Dr Nick Kelly, Design, Queensland University of Technology

- Dr Nick Schultz, Ecology, Federation University

- Associate Professor Nick Thieberger, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Dr Nicky Dulfer, Education, University of Melbourne

- Dr Nicola Carr, Education, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Nicola Henry, Social Sciences, RMIT University

- Nicola Laurent, Archives, University of Melbourne

- Nicole Davis, History, University of Melbourne

- Professor Nicole Gurran, Urban Planning, University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Nicole Rogers, Law, Southern Cross University

- Dr Nikita Vanderbyl, Indigenous Studies, University of Melbourne

- Professor Nikos Papastergiadis, Media, University of Melbourne

- Dr Nikos Thomacos, Psychology, Monash University

- Dr Nilmini Fernando, Sociology, Griffith University

- Dr Nina Williams, Geography, University of NSW

- Dr Niro Kandasamy, History, University of Melbourne

- Olivia Price, Public Health, University of NSW

- Dr Olwyn Stewart, Philosophy, University of Auckland

- Dr Orana Sandri, Environmental Studies, RMIT University

- Padraic Gibson, History, University of Technology Sydney

- Pamela Buena, Education, University of NSW

- Paris Hadfield, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Pashew Nuri, Education, Monash University

- Emeritus Professor Patricia Grimshaw, History, University of Melbourne

- Dr Patrick Kelly, Media, RMIT University

- Dr Paul Munro, Geography, University of NSW

- Professor Paul Patton, Philosophy, Flinders University

- Professor Paul Tacon, Archaeology, Griffith University

- Dr Paula Satizabal, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Payal Bal, Ecology, University of Melbourne

- Dr Peta Malins, Criminology, RMIT University

- Peta Phelan, Health, University of Melbourne

- Dr Peta White, Education, Deakin University

- Dr Peter Balint, Politics, University of NSW

- Dr Peter Chambers, Criminology, RMIT University

- Associate Professor Peter Christoff, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Peter Ellis, Fine Art, RMIT University

- Peter Hogg, Architecture, Melbourne Polytechnic

- Professor Peter Marius Veth, Archaeology, University of WA

- Professor Peter Otto, Literary Studies, University of Melbourne

- Dr Philippa Chandler, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Phillipa Bellemore, Sociology, Macquarie University

- Dr Phoebe Everingham, Geography, University of Newcastle

- Dr Phoebe Smithies, Physiotherapy, University of Melbourne

- Pia Treichel, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Pip Henderson, Public Health, Flinders University

- Dr Piper Rodd, History, Deakin University

- Polly Bennett, Sociology, Deakin University

- Dr Poppy de Souza, Media, University of NSW

- Dr Prashanti Mayfield, Geography, RMIT University

- Priya Kunjan, Politics, University of Melbourne

- Dr Quah Ee Ling Sharon, Sociology, University of Wollongong

- Dr Rachael Burgin, Criminology, Swinburne University

- Dr Rachael Dwyer, Education, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Rachael Fernald, Social Work, RMIT University

- Dr Rachel Buchanan, Education, University of Newcastle

- Dr Rachel Burke, Linguistics, University of Newcastle

- Dr Rachel Busbridge, Sociology, Australian Catholic University

- Dr Rachel Chapman, Education, Melbourne Polytechnic

- Dr Rachel Deacon, Health, University of Sydney

- Rachel England, Environmental Studies, Australian National University

- Dr Rachel Forgasz, Education, Monash University

- Associate Professor Rachel Heath, Psychology, University of Newcastle

- Rachel Iampolski, Geography, RMIT University

- Dr Rachel Joy, Criminology, Australian College of Applied Psychology

- Dr Rachel Loney-Howes, Criminology, University of Wollongong

- Professor Rachel Nordlinger, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Dr Rachel Thompson, Public Health, University of Sydney

- Dr Rachel Toovey, Physiotherapy, University of Melbourne

- Rachele Gore, Microbiology, RMIT University

- Dr Radha O’Meara, Creative Writing, University of Melbourne

- Radha Pathy, Psychology, Macquarie University

- Associate Professor Raimondo Bruno, Psychology, University of Tasmania

- Dr Randa Abdel-Fattah, Sociology, Macquarie University

- Dr Rea Saunders, Indigenous Studies, University of Queensland

- Dr Rebecca Ananian-Welsh, Law, University of Queensland

- Rebecca Clements, Urban Planning, University of Melbourne

- Dr Rebecca Colvin, Social Science, Australian National University

- Dr Rebecca Defina, Linguistics, University of Melbourne

- Rebecca Hiscock, Criminology, RMIT University

- Dr Rebecca Olive, Cultural Studies, University of Queensland

- Dr Rebecca Runting, Geography, University of Melbourne

- Dr Rebecca Wheatley, Ecology, University of Tasmania

- Dr Renae Fomiatti, Sociology, La Trobe University

- Renee Cosgrave, Fine Art, Monash University

- Dr Rhian Morgan, Anthropology, James Cook University

- Dr Riccarda Peters, Neuroscience, University of Melbourne

- Associate Professor Richard McDermid, Science, Macquarie University

- Rifaie Tammas, Politics, University of Sydney

- Dr Rimi Khan, Cultural Studies, RMIT University

- Ritika Skand Vohra, Fashion, RMIT University

- Professor Rob Moodie, Public Health, University of Melbourne

- Dr Robert Boncardo, European Studies, University of Sydney

- Associate Professor Robert Parkes, Education, University of Newcastle

- Robert Polglase, Urban Studies, RMIT University

- Dr Robin Bellingham, Education, Deakin University

- Dr Robin Torrence, Archaeology, Australian Museum

- Dr Robyn Babaeff, Education, Monash University

- Robyn Boldy, Environmental Science, University of Queensland

- Dr Robyn Schofield, Environmental Science, University of Melbourne

- Dr Robyn Williams, Indigenous Health, Charles Sturt University