inbox and environment news: Issue 476

November 29 - December 5, 2020: Issue 476

Parra'dowee Time

November-December

Goray'murrai—Warm and wet, do not camp near rivers

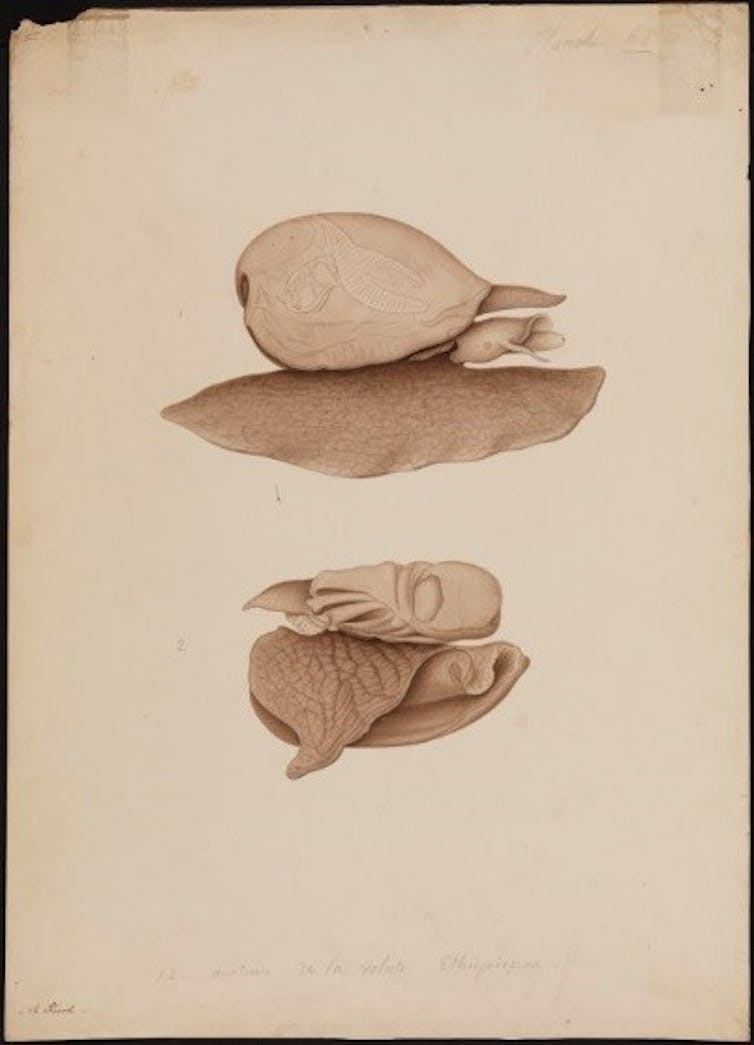

This season begins with the Great Eel Spirit calling his children to him, and the eels which are ready to mate make their way down the rivers and creeks to the ocean.

It is the time of the blooming of the Kai'arrewan (Acacia binervia) which announces the occurrence of fish in the bays and estuaries.

Acacia binervia, commonly known as the coast myall, is a wattle native to New South Wales and Victoria.

Cockatoo: Birds In Our Back Yard

.jpg?timestamp=1606544200648)

.jpg?timestamp=1606544243122)

Watch Out On The Pittwater Estuary Water Zones & Beaches: Seals Are About

Residents have filmed and photographed the seals living at Barrenjoey as far south as Rowland Reserve and over at Clareville beach in recent days and ask that people keep an eye out for them and ensure they are kept safe from boat strikes and dogs are kept off the beaches they're not supposed to be on.

Can You Help Restore Our Environment? R&R Grants Open

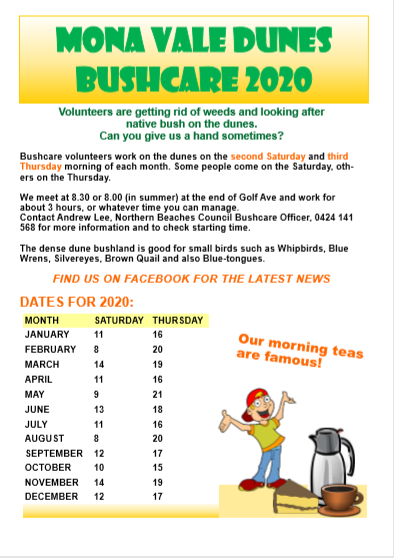

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Grants To Fund Innovative Re-Use And Recycling Projects

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) is calling for innovative and new projects looking for ways to re-use discarded materials to make new products or for new uses, and for construction projects that want to re-use materials like construction waste, glass or plastic, to apply for new grants to help create a circular economy.

New intakes for the EPA’s Circulate and Civil Construction Market Programs are now open and aiming to divert valuable materials from landfill for re-use, recycling and industrial ecology projects.

The grant funding helps organisations including businesses, councils, not-for-profits, waste service providers and industry bodies, among others, design projects that promote the circular economy, instead of a disposable culture.

EPA Director Circular Economy Programs Kathy Giunta said these programs will provide grant funding to support industry to respond to the decision by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) this year to ban the export of certain wastes that have not been processed into value-added material.

“One of the ways to mitigate the effects of China’s National Sword policy and to prepare NSW for the waste export ban is to invest in projects that demonstrate innovative uses of recyclables,” Ms Giunta said.

“The Circulate Program provides grants of up to $150,000 for innovative, commercially-oriented industrial ecology projects. Circulate supports projects that will recover materials that would otherwise be sent to landfill, and to instead use them as feedstock for other commercial, industrial or construction processes.

“The Civil Construction Market Program provides grants of up to $250,000 for civil construction projects that re-use construction and demolition waste or recyclables from households and businesses such as glass, plastic and paper.”

Previous projects in the Circulate Program include Cross Connections’ Plastic Police, which supplied soft plastics to the Downer Group’s Reconophalt project, the first road surfacing material in Australia to contain high recycled content from waste streams, also including glass and toner, which would otherwise be bound for landfill or stockpiled.

Previous projects in the Civil Construction Market Program include supporting Lendlease’s use of recycled glass from Lismore Council in pavement concrete on three trial sites as part of the Woolgoolga to Ballina Pacific Highway Upgrade.

Applications will be open until Friday 12 February 2021.

For details of the grants and how to apply, visit epa.nsw.gov.au/circulate and epa.nsw.gov.au/working-together/grants/business-recycling/civil-construction-market-program-grants

ICAC Recommends Changes To Government Water Management In NSW After Years Of Focus On Irrigation Industry Interests

Friday 27 November 2020

The NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) has made 15 recommendations to the NSW Government to improve the management of the state’s water resources, after the undermining of the governing legislation’s priorities over the past decade by the responsible department’s repeated tendency to adopt an approach that was unduly focused on the interests of the irrigation industry.

In a report released today, Investigation into complaints of corruption in the management of water in NSW and systemic non-compliance with the Water Management Act 2000, the ICAC examined multiple allegations, over almost a decade, in two related investigations (Operation Avon and Operation Mezzo), concerning complaints of corruption involving the management of water, particularly in the Barwon-Darling area of the Murray-Darling Basin. Ultimately the Commission was not satisfied in relation to any of the matters it investigated that the evidence established that any person had engaged in corrupt conduct for the purposes of the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988.

However, it did form an opinion that in many of the matters it investigated the evidence established that certain decisions and approaches taken by the NSW Government department with responsibility for water management over the last decade were inconsistent with the object, principles and duties of the Water Management Act 2000 (WMA) and failed to give effect to legislated priorities for water sharing.

The report notes that at a policy level, the investigation found that the development and implementation of the 2012 Barwon-Darling Water Sharing Plan represented a failure to adhere to the priorities set out in the WMA.

Specific failures in the administrative arrangements concerning water regulation and compliance also created an atmosphere that was overly favourable to irrigators. This was largely due to chronic underfunding, organisational dysfunction and a lack of commitment to compliance.

More generally, the irrigator focus of the Department of Primary Industries – Water (DPI-W) was entrenched in its approach towards stakeholder consultation, which focused on the irrigation industry, while restricting information available to other stakeholders, such as environmental agencies. As a result, the policy-making process became vulnerable to improper favouritism, as environmental perspectives were sidelined from policy discussions.

The Commission has made 15 recommendations to address these issues and to promote the integrity and good repute of public administration in relation to water management. Specifically, the recommendations concern the undue focus on irrigators' interests within water agencies and deal with the:

- lengthy history of failure in giving proper and full effect to the objects, principles and duties of the WMA, and its priorities for water sharing

- failure to fully implement water sharing plans and ensure they are audited

- need to fund independent scientific audits to determine the ecological health of rivers

- lack of transparency, balance and fairness in consultation processes undertaken by water agencies in relation to external stakeholders

- sidelining of public officials undertaking environmental roles within the NSW Government

- control weaknesses in the classification and handling of confidential and sensitive information

- flaws in the recruitment procedures used to engage a director of intergovernmental strategic stakeholder relations at DPI-W

- regulatory failures in the state’s water market

- lack of transparency and accountability in water account information.

The Commission is not of the opinion that consideration should be given to obtaining the advice of the Director of Public Prosecutions with respect to the prosecution of any individual.

The ICAC determined that it was not in the public interest to conduct a public inquiry in this matter. Instead, the Commission was satisfied that the matters investigated could be satisfactorily addressed by way of a public report pursuant to section 74(1) of the ICAC Act.

In making that determination, the Commission had regard to the following considerations:

- the Commission obtained and reviewed a significant amount of cogent evidence in the course of the investigation that indicated the possibility of corrupt conduct

- careful review of this evidence and of the submissions received from affected persons led to the conclusion that no corrupt conduct findings could be made

- a public inquiry would only duplicate the evidence already obtained and would not materially assist the investigation

- a public inquiry would risk undue prejudice to peoples’ reputations, given the Commission’s findings in relation to the majority of the allegations investigated

- a public inquiry would involve an unnecessary use of Commission resources.

Download the report, Investigation into complaints of corruption in the management of water in NSW and systemic non-compliance with the Water Management Act 2000

Basin Plan Delays Are Killing Our Rivers

November 26, 2020

New Queensland and ACT water ministers must hold firm against NSW and Victorian attempts to delay water recovery at tomorrow’s Murray-Darling Basin Ministerial Council meeting Conservationists have stated this week.

“NSW continues to drag its feet on proper measurement, metering and monitoring of irrigation in the northern basin, while downstream communities, traditional owners and native fish continue to suffer,” Nature Conservation Council Chief Executive Chris Gambian said.

“There are too many straws in the glass. The river ecosystems simply cannot sustain increasing extraction.”

Mr Gambian said regulation of floodplain harvesting in NSW must ensure environmental impacts of diversion works are assessed.

“If water cannot get to rivers, or too much water is taken from rivers, downstream communities will suffer. Rivers die from the bottom up,” he said.

”Minco must decide whether NSW floodplain harvesting licences will exceed statutory limits in the Basin Plan. Licensing water that doesn’t exist will only exacerbate the problems with the Basin Plan.

“Environmental ‘offsets’ of projects like the Menindee Lakes water-saving project will not deliver real water savings and will kill the largest living wetland in the middle of the Murray-Darling Basin, contravening several international conventions.

“Minco ministers must put more emphasis on preservation of ecosystems under threat of changing climate and unbridled growth in extraction.

“We are facing extinction level events across multiple species and unless we support our lifeblood, keep our rivers healthy, we will create a basin which no longer supports life.

“We also have a duty to protect our environment for all our futures. We will be watching very closely and hoping the Ministers choose action, not more delays.”

100 Experts To Shape Design Across NSW

November 26, 2020

A panel of 100 leading design experts will be charged with improving the quality of the built environment across NSW.

Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Rob Stokes said the new State Design Review Panel pool has been appointed to provide independent expert advice on State Significant development and infrastructure projects and precincts.

“Iconic buildings and structures like the Sydney Opera House and Harbour Bridge put Sydney on the map and it’s so important that we maintain design excellence with our new projects,” Mr Stokes said.

“The new State Design Review Panel will build on the great work of the pilot program launched in 2018, which guided the development of more than 100 public and private projects worth almost $9 billion.

“A survey of participants in the pilot program found the Panel provided greater certainty, stronger design outcomes and in many cases sped up the process. This panel, alongside the soon-to-be-released Design and Place SEPP, will ensure strong design principles are considered every step of the way.

“NSW residents will also be relieved to note that the Treasurer Dom Perrottet has not been selected for the Design Review Panel.”

NSW Government Architect Abbie Galvin said the expanded panel will play a vital role in shaping the design of the State at a critical time.

“The unprecedented investment in infrastructure and the Government’s commitment to create greener places and great public spaces create an exciting climate for panel members to play a role,” Ms Galvin said.

“It’s fantastic to see such a diverse panel with a wide range of skills and expertise, including six Aboriginal design and cultural experts who will help ensure Aboriginal culture and heritage are integral to the design of places in NSW.”

The panel is made up of 88 independent members with expertise across a range of areas including architecture, landscape architecture, urban design, Aboriginal and European heritage and sustainability, and 12 State Government design champions.

For more information visit www.governmentarchitect.nsw.gov.au

Battle To Save The Pilliga Is Not Over Yet

November 25, 2020

Conservation groups have vowed to continue the campaign to stop the Narrabri gas project despoiling the largest temperate forest in NSW.

Federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley yesterday approved the project that will convert the Pilliga into an industrial gas field.

Nature Conservation Chief Executive Chris Gambian said: “This is a terrible project at a terrible time. It will cause carbon emissions in a world that urgently needs to decarbonise.

“It will also wreck the rare and precious Pilliga forest and the farms around it.

“The Federal Government’s approval is short sighted and opportunistic at a time when we desperately need thoughtful leadership.”

Santos proposes to sink 850 coal-seam gas wells in the Pilliga forest and surrounding farmland despite significant environmental risks and more than 20,000 public submissions in opposition to the project.

“The Pilliga is the largest temperate forest we have left in the state and is home to many threatened plants and animals,” Mr Gambian said.

“Turning this priceless wilderness into an industrial gas field will poison groundwater, carve up the forest with roads and pipelines, endanger koalas and other threatened species, and increase the risk of wildfires.

“It will also release millions of tonnes of potent climate pollution during mining and when the gas is finally burned.

“More than 23,000 people have already made submissions opposing this project. It has virtually no public support and we will not rest until it is stopped.

“It is hard to think of a more iconic environmental battle in our times than the campaign to protect the Pilliga.”

Narrabri Precinct Investigation

November 24, 2020

The NSW Government has today released a strategic statement outlining its ongoing support for the domestic gas industry, as a driver of new jobs and industry opportunities in regional NSW.

The release of the Strategic Opportunities for Gas in Regional NSW statement coincides with the government’s commitment to investigate a potential Narrabri Special Activation Precinct (SAP), which would streamline planning processes, create new jobs and fuel regional economic development.

Deputy Premier John Barilaro said with the recent Independent Planning Commission’s approval of the Narrabri Gas Project and investment around the Narrabri Inland Port, now is the right time to investigate a Narrabri precinct.

“Today we are releasing the NSW Government’s statement of support for the future growth of the gas industry, backing investments like the Narrabri Gas Project that will provide a $3.6 billion economic boost and create around 1500 new jobs,” Mr Barilaro said.

“This gas project opens up a wide range of industry growth opportunities in manufacturing everything from plastics to fertiliser and construction materials.

“This is great news for the local economy, and it is why the government will now start investigating a potential Special Activation Precinct in Narrabri.

“We want to create a thriving energy hub in Narrabri focused on value-added production and manufacturing to power long-term job opportunities across the region.”

The NSW Government will work closely with Narrabri Shire Council and local stakeholders on its investigations into a potential Narrabri precinct.

Narrabri Shire Council Mayor, Cr Ron Campbell, said the Narrabri Gas Project gives the potential Narrabri precinct a clear point of difference.

“This commitment is a great win for our region – a Special Activation Precinct would give potential investors confidence to commit to Narrabri and be innovative with the opportunities available here to do business with the world,” Cr Campbell said.

The NSW Government’s Strategic Opportunities for Gas in Regional NSW statement outlines the government’s support for the domestic gas industry, with a comprehensive Future of Gas Strategy to be delivered in 2021.

Find out more about the Gas statement and SAP

More Foreign Workers Approved As First Flight Arrives From Fiji

November 25, 2020

The NSW Government has provided approval for a further 160 critical workers to arrive from either the Soloman Islands, Tonga or Vanuatu to assist the labour-intensive tomato industry, Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall announced today.

The 160 workers are in addition to the 350 skilled workers announced last month to help fill a labour shortage in the State’s abattoirs.

Mr Marshall said the NSW Government was doing everything it could to help facilitate the arrival of foreign workers to minimise supply chain disruption caused by labour shortages due to COVID-19 international travel restrictions.

“The first group of foreign workers arrives today from Fiji and will immediately enter strict hotel quarantine,” Mr Marshall said.

“Once they have completed quarantine, they will be able to travel to our regional centres and take up their roles in our abattoirs.

“As we come into the festive season, we know there will be strong demand for fantastic NSW meats.

“By helping to facilitate the arrival of these foreign workers, we are helping to take pressure off the supply chain to make sure everyone can enjoy a Christmas roast.

“Similarly, once Commonwealth approval is secured, the extra 160 foreign workers will be able to give us a hand to harvest our tomato crop.

“The tomato industry is worth more than $50 million to the State’s economy, so by providing support to the sector we also give also our rural communities that rely on its success a boost.

“We will continue to work hand in glove with the agriculture sector to explore other opportunities,” Mr Marshall said.

The facilitation of foreign workers is in addition to implementing the National Agricultural Workers’ Code and launching the Help Harvest NSW portal to connect domestic labour supply with demand.

The charter flights and quarantine arrangements are funded by industry.

Fishers Given Greater Input Into Harvest Strategies

November 24, 2020

The State’s fishing industries will benefit from greater certainty and transparency in fisheries management decisions, with the NSW Government today launching a draft policy and guidelines to steer the development of harvest strategies.

Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall today encouraged commercial fishers, industry members and stakeholders to review and provide their feedback on the draft policy and guidelines.

“The NSW Government wants to work in direct partnership with the fishing industry to provide commercial, recreational and Aboriginal fishers what they need to be sustainable and profitable into the future,” Mr Marshall said.

“In June this year I announced the NSW Government would provide fishers greater certainty and transparency in fisheries management decisions, through the development of tailored harvest strategies, and today is the first step towards that.

“This is a critical part in the development of tailored harvest strategies for each fishery, and for giving all stakeholders a clear understanding of how, when and why fisheries management decisions are made.

“This approach is world’s best-practice, and I’m pleased to see it jointly driven and adopted by the industry and government in partnership for the benefit of our commercial fishers, consumers of NSW seafood and the wider community.”

The NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) has developed the draft policy and guidelines, supported by the Ministerial Fisheries Advisory Council, NSW CommFish, RecFishNSW and the Aboriginal Fisheries Advisory Council.

Harvest strategies will be drafted by working groups comprised of an independent chair, independent scientist and independent economist, along with representatives from the commercial, recreational and Aboriginal fishing sectors, as well as DPI.

Working groups for the Trawl Whiting and Rock Lobster fisheries have already been established.

Harvest strategies are a key deliverable under the NSW Marine Estate Management Strategy 2018-2028.

The draft policy and guidelines are available for review on the NSW DPI website.

Humans are changing fire patterns, and it's threatening 4,403 species with extinction

Last summer, many Australians were shocked to see fires sweep through the wet tropical rainforests of Queensland, where large and severe fires are almost unheard of. This is just one example of how human activities are changing fire patterns around the world, with huge consequences for wildlife.

In a major new paper published in Science, we reveal how changes in fire activity threaten more than 4,400 species across the globe with extinction. This includes 19% of birds, 16% of mammals, 17% of dragonflies and 19% of legumes that are classified as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable.

But, we also highlight the emerging ways we can help promote biodiversity and stop extinctions in this new era of fire. It starts with understanding what’s causing these changes and what we can do to promote the “right” kind of fire.

How Is Fire Activity Changing?

Recent fires have burned ecosystems where wildfire has historically been rare or absent, from the tropical forests of Queensland, Southeast Asia and South America to the tundra of the Arctic Circle.

Exceptionally large and severe fires have also been observed in areas with a long history of fire. For example, the 12.6 million hectares that burnt in eastern Australia during last summer’s devastating bushfires was unprecedented in scale.

This extreme event came at a time when fire seasons are getting longer, with more extreme wildfires predicted in forests and shrublands in Australia, southern Europe and western United States.

But fire activity isn’t increasing everywhere. Grasslands in countries such as Brazil, Tanzania, and the United States have had fire activity reduced.

Extinction Risk In A Fiery World

Fire enables many plants to complete their life cycles, creates habitats for a wide range of animals and maintains a diversity of ecosystems. Many species are adapted to particular patterns of fire, such as banksias — plants that release seeds into the resource-rich ash covering the ground after fire.

But changing how often fires occur and in what seasons can harm populations of species like these, and transform the ecosystems they rely on.

We reviewed data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and found that of the 29,304 land-based and freshwater species listed as threatened, modified fire regimes are a threat to more than 4,403.

Most are categorised as threatened by an increase in fire frequency or intensity.

For example, the endangered mallee emu-wren in semi-arid Australia is confined to isolated patches of habitat, which makes them vulnerable to large bushfires that can destroy entire local populations.

Likewise, the Kangaroo Island dunnart was listed as critically endangered before it lost 95% of its habitat in the devastating 2019-2020 bushfires.

However, some species and ecosystems are threatened when fire doesn’t occur. Frequent fires are an important part of African savanna ecosystems and less fire activity can lead to shrub encroachment. This can displace wild herbivores such as wildebeest that prefer open areas.

How Humans Change Fire Regimes

There are three main ways humans are transforming fire activity: global climate change, land-use and the introduction of pest species.

Global climate change modifies fire regimes by changing fuels such as dry vegetation, ignitions such as lightning, and creating more extreme fire weather.

What’s more, climate-induced fires can occur before the dominant tree species are old enough to produce seed, and this is reshaping forests in Australia, Canada and the United States.

Humans also alter fire regimes through farming, forestry, urbanisation and by intentionally starting or suppressing fires.

Introduced species can also change fire activity and ecosystems. For example, in savanna landscapes of Northern Australia, invasive gamba grass increases flammability and fire frequency. And invasive animals, such as red foxes and feral cats, prey on native animals exposed in recently burnt areas.

Read more: Fire-ravaged Kangaroo Island is teeming with feral cats. It's bad news for this little marsupial

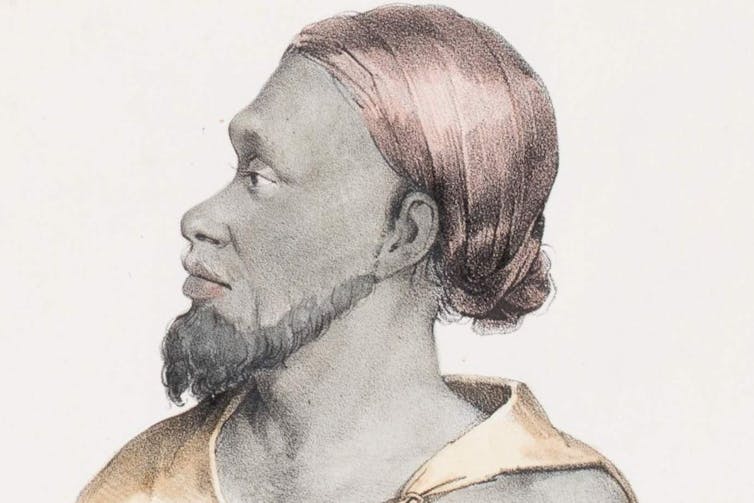

Importantly, cultural, social and economic changes underpin these drivers. In Australia, the displacement of Indigenous peoples and their nuanced and purposeful use of fire has been linked with extinctions of mammals and is transforming vegetation.

We Need Bolder Conservation Strategies

A suite of emerging actions — some established but receiving increasing attention, others new — could help us navigate this new fire era and save species from extinction. They include:

managed wildfire — let some fires burn naturally in fire-prone ecosystems where fire has been absent for too long, suppressing only under specific conditions

deployment of rapid response teams to enact targeted fire suppression and emergency conservation management, including providing animal refuges, reseeding to promote plant regeneration and large-scale habitat restoration

reintroduction of grazing and digging animals that regulate fire regimes by reducing fuel loads, for the benefit of whole ecosystems

Indigenous fire stewardship, and continuing and reinstating cultural burning in a modern context. This boosts biodiversity, ecosystems and human well-being

green firebreaks or greenbelts, which comprises low-flammability land uses such as parkland and open vegetation to help reduce fire spread, while providing refuges for wildlife.

Where To From Here?

The input of scientists will be valuable in helping navigate big decisions about new and changing ecosystems.

Empirical data and models can monitor and forecast changes in biodiversity. For example, new modelling has allowed University of Melbourne researchers to identify alternative strategies for introducing planned or prescribed burning that reduces the risk of large bushfires to koalas.

New partnerships are also needed to meet the challenges ahead.

At the local and regional scale, Indigenous-led fire stewardship is an important approach for fostering relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous organisations and communities around the world.

And international efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming are crucial to reduce the risk of extreme fire events. With more extreme fire events ahead of us, learning to understand and adapt to changes in fire regimes has never been more important.

Luke Kelly, Senior Lecturer in Ecology and Centenary Research Fellow, University of Melbourne; Annabel Smith, Lecturer in Wildlife Management, The University of Queensland; Katherine Giljohann, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Melbourne, and Michael Clarke, Professor of Zoology, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

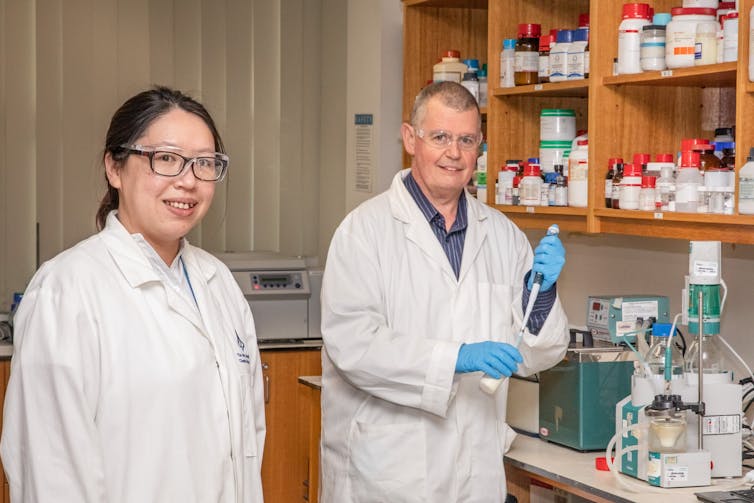

Humans are polluting the environment with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and I'm finding them everywhere

Many of us are aware of the enormous threat of antibiotic- (or “antimicrobial”) resistant bacteria on human health. But few realise just how pervasive these superbugs are — antimicrobial-resistant bacteria have jumped from humans and are running rampant across wildlife and the environment.

My research is revealing the enormous breadth of wildlife species with superbugs in their gut bacterial communities (“microbiome”). Affected wildlife includes little penguins, sea lions, brushtailed possums, Tassie devils, flying foxes, echidnas, and a range of kangaroo and wallaby species.

Read more: Speaking with: Dr Mark Blaskovich on antibiotic-resistant bacteria and the threat of superbugs

To combat antibiotic resistance, we need to use “One Health” — an approach to public health that recognises the interconnectedness of people, animals and the environment.

And this week’s appointment of federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley to the world’s first One Health Global Leaders Group on Antimicrobial Resistance, brings me confidence we’re finally heading in the right direction.

Where We’ve Found Superbugs

Tackling antimicrobial resistance with One Health requires studying resistance in bacteria from people, domesticated animals, wildlife and the environment.

Humans have solely driven the emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, mainly through the overuse, and often misuse, of antibiotics.

The spread of superbugs to the environment has mainly occurred through human wastewater. Medical and industrial waste, which pollute the environment with the antibiotics themselves, worsen the issue. And the ability for antibiotic-resistant genes to be shared between bacteria in the environment has propelled antimicrobial resistance even further.

Read more: How antibiotic pollution of waterways creates superbugs

Generally, wildlife closer to people in urban areas are more likely to carry antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, because we share our homes, food waste and water with them.

For example, our recent research showed 48% of 664 brushtail possums around Sydney and Melbourne tested positive for antibiotic-resistant genes.

Whether animals are in captivity or the wild also plays a role in their levels of antimicrobial resistance.

For example, we found only 5.3% of grey-headed flying-foxes in the wild were carrying resistance traits. This jumps to 41% when flying-foxes are in wildlife care or captivity.

Likewise, less than 2% of wild Australian sea lions we tested had antibiotic-resistant bacteria, compared to more than 40% of those in captivity. We’ve found similar trends between captive and wild little penguins, too.

And more than 40% of brush-tailed rock wallabies in a captive breeding program were carrying antibiotic resistance genes compared to none from the wild.

So Why Is This A Problem?

An animal with antibiotic-resistant bacteria may be harder to treat with antibiotics if it’s injured or sick and ends up in care. But generally, we’re yet to understand their full impact – though we can speculate.

For wildlife, resistant bacteria are essentially “weeds” in their microbiomes. These microbial weeds may disrupt the microbiomes, impairing immunity or increasing the risk of infection by other agents.

Another problem relates to how antimicrobial-resistant bacteria can spread their resistant genes to other bacteria. Sharing genes between bacteria is a major driver for new resistant bacterial strains.

We’ve been finding more types of resistant genes in an animal’s microbiome than we do in comparison to commonly studied bacteria, such as Escherichia coli. This means some wildlife bacteria may have acquired resistance genes, but we don’t know which.

Many of the wildlife species we’ve examined also carry human-associated bacterial strains — strains known to cause, for instance, diarrhoeal disease in humans. In wildlife, these bacteria could potentially acquire novel resistance genes making them harder to treat if they spread back to people.

This is something we found in grey-headed flying-fox microbiomes, which had new combinations of resistant genes. These, we concluded, originated from the outside environment.

How Do We Mitigate This Threat?

Antimicrobial stewardship — using the best antibiotic when a bacterial infection is diagnosed, and using it appropriately — is a big part of tackling this global health issue.

This is what’s outlined in Australia’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy: 2020 & Beyond, which the federal government released in March this year.

The 2020 strategy builds on a previous strategy by better incorporating the environment, in what should be a true “One Health” approach. The World Health Organisation’s appointment of Ley supports this.

Antimicrobial stewardship is equally important for those in veterinary fields as well as medical doctors. As Australia leads the world in wildlife rehabilitation, antimicrobial stewardship should be a major part of wildlife care.

For the rest of us, preventing our superbugs from spilling over to wildlife also starts with taking antibiotics appropriately, and recognising antibiotics work only for bacterial infections. It’s also worth noting you should find a toilet if you’re out in the bush (and not “go naturally”), and not leave your food scraps behind for wild animals to find.

The 2020 strategy recognises the need for better communication to strengthen stewardship and awareness. This should include education on the issues of antimicrobial resistance, what it means for wildlife health, and how to mitigate it.

This is something my colleagues and I are tackling through our citizen science project, Scoop a Poop, where we work with school children, community groups and wildlife carers who collect possum poo around the country to help us better understand antimicrobial resistance in the wild.

The power of working with citizens to better the health of our environment cannot be overstated.

Read more: Explainer: what are superbugs and how can we control them? ![]()

Michelle Power, Associate Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Not just hot air: turning Sydney's wastewater into green gas could be a climate boon

Biomethane technology is no longer on the backburner in Australia after an announcement this week that gas from Sydney’s Malabar wastewater plant will be used to power up to 24,000 homes.

Biomethane, also known as renewable natural gas, is produced when bacteria break down organic material such as human waste.

The demonstration project is the first of its kind in Australia. But many may soon follow: New South Wales’ gas pipelines are reportedly close to more than 30,000 terajoules (TJs) of potential biogas, enough to supply 1.4 million homes.

Critics say the project will do little to dent Australia’s greenhouse emissions. But if deployed at scale, gas captured from wastewater can help decarbonise our gas grid and bolster energy supplies. The trial represents the chance to demonstrate an internationally proven technology on Australian soil.

What’s The Project All About?

Biomethane is a clean form of biogas. Biogas is about 60% methane and 40% carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other contaminants. Turning biogas into biomethane requires technology that scrubs out the contaminants – a process called upgrading.

The resulting biomethane is 98% methane. While methane produces CO₂ when burned at the point of use, biomethane is considered “zero emissions” – it does not add to greenhouse gas emissions. This is because:

it captures methane produced from anaerobic digestion, in which microorganisms break down organic material. This methane would otherwise have been released to the atmosphere

it is used in place of fossil fuels, displacing those CO₂ emissions.

Biomethane can also produce negative emissions if the CO₂ produced from upgrading it is used in other processes, such as industry and manufacturing.

Biomethane is indistinguishable from natural gas, so can be used in existing gas infrastructure.

Read more: Biogas: smells like a solution to our energy and waste problems

The Malabar project, in southeast Sydney, is a joint venture between gas infrastructure giant Jemena and utility company Sydney Water. The A$13.8 million trial is partly funded by the federal government’s Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA).

Sydney Water, which runs the Malabar wastewater plant, will install gas-purifying equipment at the site. Biogas produced from sewage sludge will be cleaned and upgraded – removing contaminants such as CO₂ – then injected into Jemena’s gas pipelines.

Sydney Water will initially supply 95TJ of biomethane a year from early 2022, equivalent to the gas demand of about 13,300 homes. Production is expected to scale up to 200TJ a year.

Biomethane: The Benefits And Challenges For Australia

A report by the International Energy Agency earlier this year said biogas and biomethane could cover 20% of global natural gas demand while reducing greenhouse emissions.

As well as creating zero-emissions energy from wastewater, biomethane can be produced from waste created by agriculture and food production, and from methane released at landfill sites.

The industry is a potential economic opportunity for regional areas, and would generate skilled jobs in planning, engineering, operating and maintenance of biogas and biomethane plants.

Methane emitted from organic waste at facilities such as Malabar is 28 times more potent than CO₂. So using it to replace fossil-fuel natural gas is a win for the environment.

Read more: Emissions of methane – a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide – are rising dangerously

It’s also a win for Jemena, and all energy users. Many of Jemena’s gas customers, such as the City of Sydney, want to decarbonise their existing energy supplies. Some say they will stop using gas if renewable alternatives are not found. Jemena calculates losing these customers would lose it A$2.1 million each year by 2050, and ultimately, lead to higher costs for remaining customers.

The challenge for Australia will be the large scale roll out of biomethane. Historically, this phase has been a costly exercise for renewable technologies entering the market.

The Global Picture

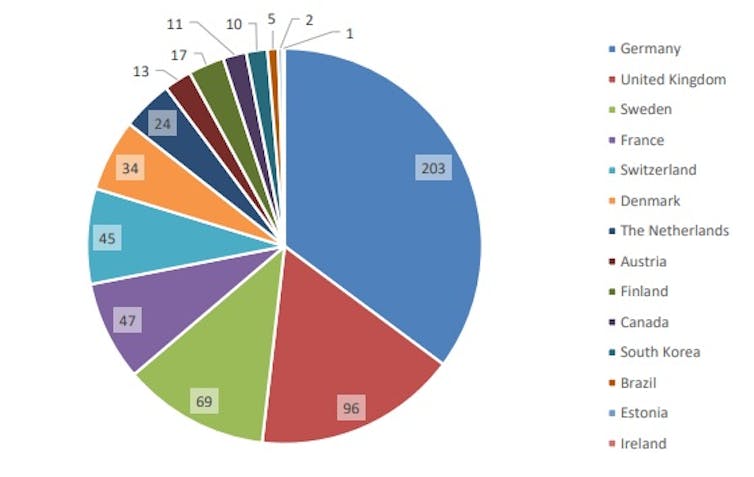

Worldwide, the top biomethane-producers include Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden, France and the United States.

The international market for biomethane is growing. Global clean energy policies, such as the European Green Deal, will help create extra demand for biomethane. The largest opportunities lie in the Asia-Pacific region, where natural gas consumption and imports have grown rapidly in recent years.

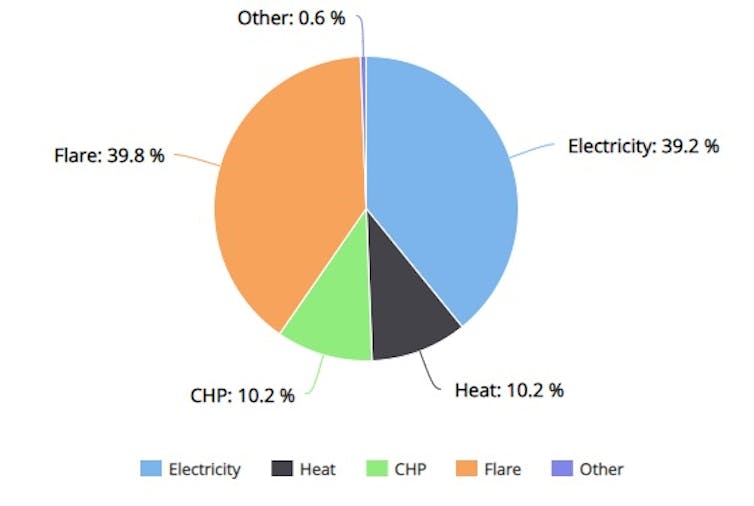

Australia is lagging behind the rest of the world on biomethane use. But more broadly, it does have a biogas sector, comprising than 240 plants associated with landfill gas power units and wastewater treatment.

In Australia, biogas is already used to produce electricity and heat. The step to grid injection is sensible, given the logistics of injecting biomethane into existing gas infrastructure works well overseas. But the industry needs government support.

Last year, a landmark report into biogas opportunities for Australia put potential production at 103 terawatt hours. This is equivalent to almost 9% of Australia’s total energy consumption, and comparable to current biogas production in Germany.

A Clean Way To A Gas-Led Recovery

While the scale of the Malabar project will only reduce emissions in a small way initially, the trial will bring renewable gas into the Australia’s renewable energy family. Industry group Bioenergy Australia is now working to ensure gas standards and specifications are understood, to safeguard its smooth and safe introduction into the energy mix.

The Morrison government has been spruiking a gas-led recovery from the COVID-19 recession, which it says would make energy more affordable for families and businesses and support jobs. Using greenhouse gases produced by wastewater in Australia’s biggest city is an important – and green – first step.

Bernadette McCabe, Professor and Principal Scientist, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Drones, detection dogs, poo spotting: what’s the best way to conduct Australia’s Great Koala Count?

Federal environment minister Sussan Ley this week announced A$2 million for a national audit of Australia’s koalas, as part of an A$18 million package to protect the vulnerable species.

The funding might seem like a lot – and, truth be told, it is more than most threatened species receive. But the national distribution of koalas is vast, so the funding equates to about A$1.40 to survey a square kilometre. That means the way koalas are counted in the audit must be carefully considered.

Koalas are notoriously difficult to detect, and counts so far have been fairly unreliable. That can make it hard to get an accurate picture of how koalas are faring, and to know where intensive conservation effort is needed – especially after devastating events such as last summer’s bushfires.

Methods for counting koalas range from the traditional – people at ground level looking up into the trees – to the high-tech, such as heat-seeking drones. So let’s look at each method, and how we can best get a handle on Australia’s koala numbers.

Why We Need To Know Koala Numbers

Gathering data about species distribution and population size is crucial, because governments use it to assess a species’ status and decide what protection it needs.

In announcing the funding, Ley said the new audit aims to fill data gaps, identify where koala habitat can be expanded, and establish an annual monitoring program.

Read more: Koala-detecting dogs sniff out flaws in Australia's threatened species protection

So far, population estimates for koalas at the state and national level are rare and highly uncertain. For example, the last national koala count in 2012 estimated 33,000-153,000 in Queensland, 14,000–73,000 in NSW and 96,000-378,000 in the southern states.

This uncertainty can make it hard to detect changes in population trends quickly enough to do something about the threat, such as by limiting development or logging. However, the new audit can use methods not available in 2012, which should help with accuracy.

So How Do You Actually Count Koalas?

Finding a koala can be difficult. There may be few individuals spread over large areas. And koalas are well camouflaged and quiet, unless bellowing. Finally, they can sit high in the tree canopy.

In numerous research and management programs, we have observed that even the most experienced koala spotter may only see 20–80% of koalas present at a site, especially if the vegetation is thick or the terrain difficult to move through.

Traditional surveys involve multiple people independently searching the same area, and correcting counts based on the number of koalas each observer sees. This helps account for the difficulties in koala counting, but it’s hard, slow and costly work.Making the job even harder, existing koala habitat maps can be highly inaccurate and miss unexpected hotspots. However, computer modelling using the latest methods, if carefully validated on the ground, can produce more accurate maps.

Searching for koala scat (poo) also is a common method of determining koala habitat – wherever koalas spend time, they will leave scats. However, the small brown pellets are easily missed, and large surveys for scats are time consuming.

Detection dogs have been trained to locate koala scats: in one study, dogs were shown to be 150% more accurate and 20 times quicker than humans.

And because male koalas bellow during the breeding season, koalas can also be detected with acoustic surveys. Audio recorders are left at a survey sites and the recordings scanned for bellows to determine whether koalas are present.

Recently, heat-seeking drones have also been used to detect koalas. This method can be accurate and effective, especially in difficult terrain. We used them extensively to find surviving koalas after the 2019-20 bushfires.

Citizen scientists can also collect important data about koalas. Smartphone apps allow the community to report sightings around Australia, helping to build a picture of where koalas have been seen. However, these sightings are often limited to areas commonly traversed by people, such as in suburbia, near walking tracks and on private property.

Getting The Koala Count Right

All these methods involve a complex mix of strengths and weaknesses, which means the audit will need input from koala ecologists if it’s to be successful. Survey methods and sites must be chosen strategically to maximise the benefits of the funding.

Robust research data exists, but is patchy across the koala’s entire range. The first step could include collating all current data, including community sightings, to determine where additional surveys are needed. This will allow for funding to be prioritised to fill data gaps.

It is promising that the announcement includes monitoring over the long term. This will help identify population trends and better understand the response of koalas to ongoing threats. It will also reveal whether actions to address koala threats are working.

Finally, while threats to koalas are generally well understood, they can vary between populations. So the audit should allow for “threat mapping” – identifying threats and looking for ways to mitigate them.

Saving An Iconic Species

Last summer’s bushfires highlighted how koalas, and other native species, are vulnerable to climate change. And the clearing of koala habitat continues, at times illegally.

Government inquiries and reviews have shown state and federal environment laws are not preventing the decline of koalas and other wildlife. The federal laws are still under review.

However, the new funding underpins an important step - accurate mapping of koalas and their habitat for protection and restoration. This is a crucial task in protecting the future of this iconic Australian species.

Read more: Stopping koala extinction is agonisingly simple. But here's why I'm not optimistic ![]()

Romane H. Cristescu, Posdoc in Ecology, University of the Sunshine Coast; Celine Frere, Senior lecturer, University of the Sunshine Coast, and Desley Whisson, Senior Lecturer in Wildlife and Conservation Biology, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tick Population Booming In Our Area

Residents from Terrey Hills and Belrose to Narrabeen and Palm Beach report a high number of ticks are still present in the landscape. Local Veterinarians are stating there has not been the usual break from ticks so far and each day they’re still getting cases, especially in treating family dogs.

To help protect yourself and your family, you should:

- Use a chemical repellent with DEET, permethrin or picaridin.

- Wear light-colored protective clothing.

- Tuck pant legs into socks.

- Avoid tick-infested areas.

- Check yourself, your children, and your pets daily for ticks and carefully remove any ticks using a freezing agent.

- If you have a reaction, contact your GP for advice.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Pittwater Reserves

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Truffle Munching Wallabies Shed New Light On Forest Conservation

Alliance Of Four NSW Universities To Deliver Game Changer In Education

Changes In Fire Activity Are Threatening More Than 4,400 Species Globally

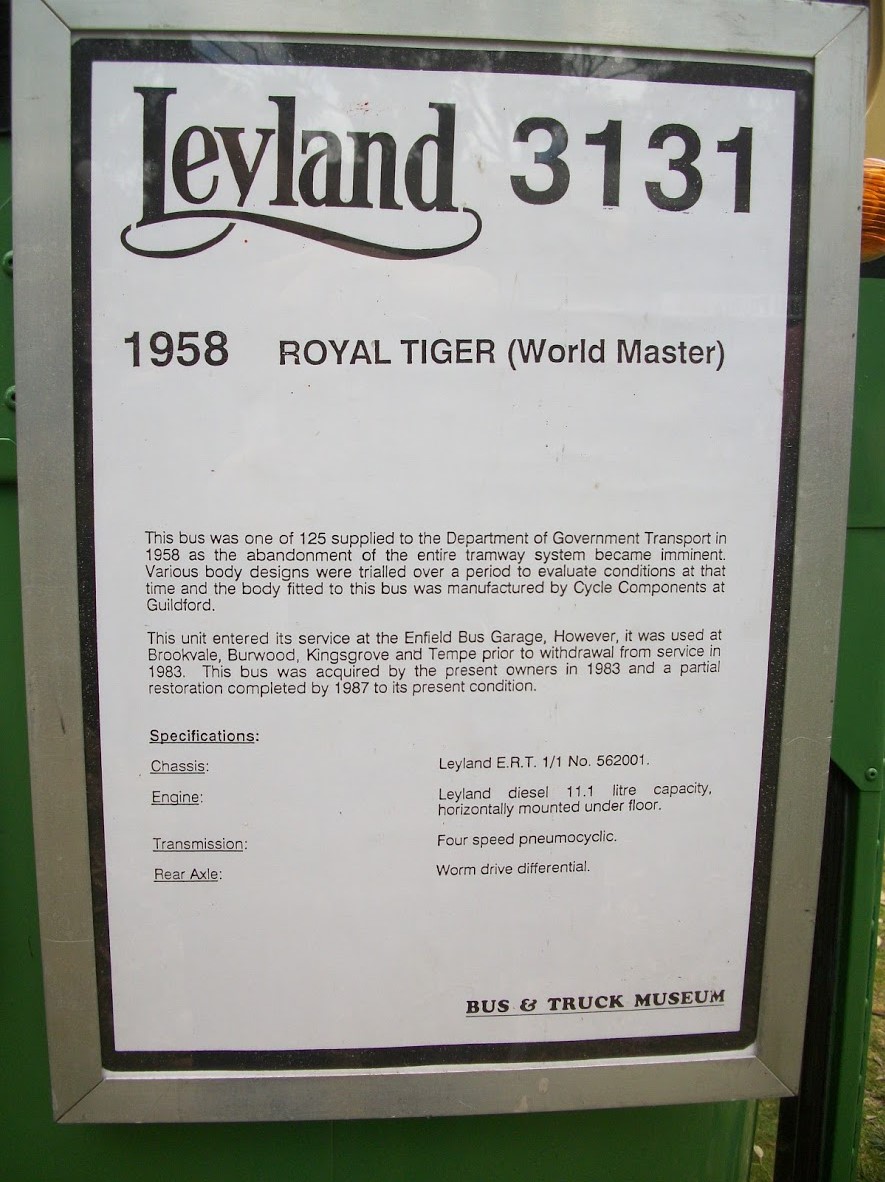

Old Buses At Mona Vale Public School 100 Years Celebrations In 2012

Curious Kids: could dinosaurs evolve back into existence?

Will there ever be dinosaurs again? — Anonymous

What an interesting question! Well, technically dinosaurs are still here in the form of birds. Just like you’re a direct descendant of your grandparents, birds are the only remaining direct descendants of dinosaurs.

But I suppose what you’re really asking is whether dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus or Triceratops could ever exist again. Although that would be fascinating, the answer is almost definitely no.

While there’s only one generation between you and your grandparents – that is, your parents – there are many millions of generations between today’s birds and their ancient dinosaurs ancestors.

This is why today’s birds look, sound and behave so differently to the prehistoric beasts that once roamed Earth.

Animals Evolve To Change, But Can’t Choose How

To understand this, we have to understand “evolution”. This is a process that explains how every living thing (including humans) evolved from past living things over millions, or even billions, of years.

Different animals evolve their own differences to help them survive in the world. For example, 66 million years ago, birds survived the catastrophic event that killed all other dinosaurs and marked the end of the Mesozoic era.

After this, a blanket of ash wrapped around the world, cooling it and blocking out the sunlight plants need to survive. Plant-eating animals would have struggled to stay alive.

But birds did, perhaps because they were small even then. They likely ate seeds and insects and took shelter in small spaces. And being able to fly would have helped them explore far and wide for food and shelter.

That said, if the conditions that came after the dinosaur extinction event returned today, no modern animal would evolve back into a dinosaur. This is because animals today have a very different evolutionary past to dinosaurs.

They evolved to have features that help them survive in today’s world, rather than a prehistoric one. And these features limit the ways they can evolve in the future.

Which Came First, The Chicken Or The Dinosaur?

For an animal to be an actual “dinosaur”, it must belong to a group of animals known by scientists as Dinosauria. These all descended from a common ancestor shared by Triceratops and modern birds.

Other than birds, Dinosauria doesn’t include any living creature. So for a dinosaur to re-evolve in the future, it would have to come from a bird.

Dinosauria’s extinct members included sauropods, stegosaurs, ankylosaurs, ornithopods, ceratopsians and non-bird theropods. Modern birds evolved from a small group of theropods. However, since so much time has passed, this link is limited.

Specifically, birds have a very different collection of “genes”. These are the same built-in “rules” your parents passed down to you that decide, for example, what colour your eyes will be.

The more generations that pass between an ancestor and their descendant, the more different their genes will be.

Even If It Could Happen, What Would This Take?

Think of how much a bird would need to change to look like Tyrannosaurus rex or Triceratops. A lot.

Dinosaurs had long tails with bones all along them. Birds’ tails are stumpy and have been for more than 100 million years. It’s unlikely this would ever be reversed.

Also, modern birds walk on their back legs only and (in most cases) have four toes and three “fingers” in their wings.

Compare that with Triceratops, which walked on all four limbs, had five fingers on its front feet (the inner three of which were weight-bearing) and four toes on its back feet.

It may not be impossible for birds to gain two more fingers to have five like Triceratops; some people with a condition called “polydactyly” have more than five fingers, but this is very rare.

There aren’t really any situations where an extra finger (or one less) would be necessary for a bird’s survival. Thus, there’s little to no chance birds will evolve to change in this way.

Even if birds did eventually start to walk on all four limbs (legs and wings), they wouldn’t move the same way a Triceratops did because the purpose of a bird’s wings is very different to that of a Triceratops’s legs.

Dinosaurs Are History

We know from fossil discoveries that Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus had scaly skin covering most of their bodies. Most modern birds have scaly feet, but none are scaly all over.

It’s hard to imagine what would force any bird to naturally replace its feathers with scales. Birds need feathers to fly, to save energy (by staying warm) and to put on special displays to attract mates.

Triceratops did have a “beak” at the front of its mouth, but this evolved completely separately to the beaks of birds and had two extra bones — something no living animal has.

What’s more, behind its beak and jaws, Triceratops had rows of teeth. While some birds such as geese have spiky beaks. No bird in the past 66 million years has ever had teeth.

Considering these huge differences, it’s really unlikely birds will ever evolve to look more like their extinct dinosaur relatives. And no extinct dinosaur will ever come back to life either — except maybe in movies!![]()

Stephen Poropat, Postdoctoral Researcher (Palaeontology), Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Curious Kids: Why do adults think video games are bad?

This is an article from Curious Kids, a new series for children. The Conversation is asking kids to send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. All questions are welcome – serious, weird or wacky!

I want to know why adults think video games are bad because the adults around my neighbourhood are ANNOYING me by saying “READ A BOOK! NO VIDEO GAMES”. Why can’t they say “it’s time to play video games now”? – Bo, aged 9, Melbourne.

Parents and children can have different ideas when it comes to video games.

Children like video games because they are fun and because they can be challenging. You have to solve problems, work out the best moves for your character, and decide how to use your equipment and supplies in the best possible way. Making all these decisions can be exciting.

Parents want to make sure that their children are safe and healthy. Because of this, they notice different things about video games.

Many worry that playing video games might have a bad effect on the way their child behaves. For example, if a video game has lots of fighting in it, they worry that playing it will encourage their child to be violent.

They are concerned that their child might always choose to play a video game instead of playing outside and getting exercise. Even though you sit still when you read a book, they know that kids can develop good reading skills and learn a lot. Many adults aren’t so sure that kids can learn anything educational from video games.

Sometimes adults think that spending too much time with animated characters is unhealthy for kids. They know it’s important for kids to spend time with “real” people and learn good social skills needed for the real world.

What Do Experts Say?

Experts think playing video games can have good and bad effects on kids. New research shows that there are lots of benefits.

One good thing is the video games that children play today often encourage them to work in teams, cooperate, and to help each other. This is because games today are often designed for multiple players, not like old-fashioned video games that were mostly designed for one player.

However, children who are obsessed with video games and play them for a long time can get really competitive and can often try to win at all costs. Experts aren’t sure yet, but they have real concerns that this might lead to kids acting like this in real life too.

One thing you also might like to know is that kids who regularly play video games often get higher grades in maths, science, and reading tests. This is because games require players to solve puzzles. You won’t get higher marks playing any video games, just those that require the player to solve these kinds of puzzles.

Doing More Of The Good And Less Of The Bad

It’s important for kids to think about what types of games they pick.

Make sure all of your games aren’t fighting games. Instead, choose more games where you need to solve puzzles. These are fun and can also help with your schoolwork. Your parents will be much happier about that!

Also, think about whether the fighting games you play are affecting how you play with your friends in real life. Only you will really know if they are having a bad effect. If they are, you might want to change the games you play.

Why not ask your parents to play a problem-solving video game with you? This will help your parents see that video games are not all bad.

It’s also important that kids and adults don’t spend too much time using a screen. That means kids not spending all their time on technology, and parents not always checking their phone and screens.

What we want to aim for is adults and kids who can spend some of their time on their screens, but also enjoying other kinds of interests and spending time with family and friends.

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. They can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

* Tell us on Twitter by tagging @ConversationEDU with the hashtag #curiouskids, or

* Tell us on Facebook

Please tell us your name and age (and, if you want to, which city you live in). You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.![]()

Joanne Orlando, Researcher: Technology and Learning, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Older Australians Locked Out Of The Workforce Rely On Covid-19 JobSeeker Supplement

Digital Disconnection

- Be Connected website: www.beconnected.esafety.gov.au

- Be Connected Helpline: 1300 795 897

Anxiety Associated With Faster Alzheimer's Disease Onset

The Conquest Of The Prickly Pear: 1936

COVID-19 Support Line Extended And Expanded

- wellbeing checks

- information about COVID-19

- advice to vulnerable people

- travel restrictions

- access to new, or queries about existing, home care services.

Free General Admission To Upgraded Australian Museum

'Schoolies 2020 - But We Must Be COVID-Safe': Police Warn School Leavers Ahead Of End Of School Celebrations

‘This year is different, this is not schoolies as you know it’ – that’s the message from senior officers at Tweed/Byron Police District ahead of 2020 end of school celebrations.

School leavers from across NSW and interstate are due to arrive in Byron Bay and other parts of Northern NSW from today (Friday 20 November 2020), and are expected to stay into December.

While there are no formal events associated with ‘Schoolies 2020’ occurring in the Byron Bay area, police are expecting thousands of school leavers to descend on the coastal town to mark the end of their 13 years of schooling.

In anticipation for the large crowds, Tweed/Byron Police District will conduct an extensive and high-visibility operation for the duration of the ‘schoolies’ period, assisted by the Richmond Police District and other Northern Region commands, the Public Order and Riot Squad, Northern Operational Support Group officers, the Mounted Unit, the Police Dog Unit, Traffic and Highway Patrol, and the Youth Command and PCYC.

Tweed/Byron Police District Commander, Superintendent Dave Roptell, said this year’s celebrations must be conducted in a COVID-safe environment, with officers to enforce all current Public Health Orders and conduct regular business compliance checks.

“We know this has been an extremely tough year for HSC students, and we appreciate that school leavers want to have a memorable time. However, these are not normal times, so we ask anyone coming to the far North Coast to be respectful – we have come this far in managing COVID-19 in our regional communities, let’s not undo all our hard work now,” Supt. Roptell said.

“With the NSW and Queensland border now re-open to regional NSW, Byron Bay is included in that zone. And with the border between NSW and Victoria to re-open early next week, we are expecting thousands of school leavers to come to our area.

“The NSW Police Force continues to work closely with health officials and other government agencies, businesses and the community to manage the COVID-19 crisis and minimise the spread of the virus.

“In saying that, we have a very clear message to those choosing to come to Byron in 2020 – this year is very different, there will be no large gatherings, no dance parties in the park. Social distancing is the new normal, and we all have to do our bit to stop the spread.

“The risk of community transmission is still present here in Australia, and with people from interstate expected to come to Byron, school leavers need to be extremely aware of the dangers of COVID-19.

“Public Health Orders currently state that no more than 20 persons can be inside a home at any one time – this includes short-stay accommodation. The orders also state that up to 30 people can be gathered in a public space at any one time, this includes places such as parks, beaches, etc.

“While we will be enforcing the Public Health Orders, police want to remind school leavers that we aren’t here to ruin the fun – our officers are here to protect you and keep you safe; approach police or authorities if you are in danger, if you feel threatened or you are a victim of any type of crime.

“Not only will police be ensuring Public Health Orders are being followed, but officers will be targeting drug and alcohol-related crime, as well as anti-social behaviour.

“Drugs and alcohol impairs your judgement and can lead to risky behaviours or choices which can impact the rest of your life. Know your limits and look out for your mates.

“With the increase in activity in the Byron town centre, we are urging all visitors and locals alike to plan ahead; those not joining in the celebrations are asked to watch out for increased pedestrian activity and keep an eye out on the roads.

“As always, if you’re planning on drinking – you need a Plan B to get yourself home,” Supt. Roptell said.

The NSW Police Force continues to work closely with the Schoolies Safety Response agencies, which include Byron Youth Service and Red Frog volunteers, alongside all health officials and other government agencies, businesses and the community to minimise disruption and maintain a COVID-Safe environment.

For all information related to schoolies during COVID-19, visit the website: https://www.schoolies.com/covid-19-faq

Anyone who has information regarding individuals or businesses in contravention of a COVID-19-related ministerial direction is urged to contact Crime Stoppers: https://nsw.crimestoppers.com.au. Information is treated in strict confidence. The public is reminded not to report crime via NSW Police social media pages.

Byron Bay Lighthouse, Beach and Hinterland Aerial Shot by K Pravin

Program Helps Skill Up School Leavers Over Summer

The NSW Government's Skilling for Recovery program offers fee-free training places for school leavers, young people and job seekers.

Hundreds of fee-free training courses are now available for school leavers, young people and job seekers, as part of the NSW Government’s Skilling for Recovery initiative.

Premier Gladys Berejiklian said the courses came from the $320 million committed to delivering 100,000 fee-free training places across the state.

“There are more than 100,000 fee-free training places available for people in NSW as the workforce looks to reskill, retrain and redeploy in a post-COVID-19 economy,” Ms Berejiklian said.

“It doesn’t matter if you are a school leaver or looking for a new career path, I encourage everyone impacted by the pandemic to see what training options are available to them.”

Minister for Skills and Tertiary Education Geoff Lee said enrolments were now open for in-demand skills leading to career pathways in areas such as aged care, nursing, trades, IT, community services, logistics and accounting.

“We are not training for the sake of training, we are training for real jobs with real futures and equipping the people of NSW with the skills they need to thrive in a post-pandemic economy,” Mr Lee said.

“There are hundreds of providers right around NSW who are ready to deliver this important training.”

As part of this Skilling for Recovery initiative, school leavers have the unique opportunity to experience a range of skills to find out what suits their passions using the Summer Skills program.

Minister for Education Sarah Mitchell said some Year 12 school leavers were still deciding what they wanted to do next.

“In designing the Summer Skills program, the NSW Government has ensured the training on offer is aligned to local industry needs,” Ms Mitchell said.

“We need to provide opportunities that help the 2020 Year 12 school leaver cohort to find their feet during these uncertain times. That’s why we’re delivering practical, bite-sized and fee-free training opportunities this summer.”

The Summer Skills offered will cover a range of industries including agriculture, construction, conservation, fitness, engineering, coding, communication and digital literacy.

You can find further details of the courses on offer as part of Skilling for Recovery and the Department of Education Summer Skills program on the respective websites.

Sydney Harbour Bridge 80th Anniversary (2012)

Video depicting the journey through the ages covering the highlights, major events and milestones of the iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Green front gardens reduce physiological and psychological stress

There is growing evidence that being in natural spaces – whether while gardening or listening to bird song – has a positive effect on mental health. Being in nature is also linked to improved cognitive function, greater relaxation, coping with trauma, and alleviating certain attention deficit disorder symptoms in children.

However, most of these studies have specifically looked at the effect of public green spaces, rather than private gardens. During a time when many people are at home due to COVID-19 restrictions, private garden spaces have been the most accessible green spaces for those who have them. But do these small green spaces have the same benefits for our mental health?

Although conducted prior to the current pandemic, my recently published study has shown that having plants in domestic front gardens (front yards) is associated with lower signs of stress. Given that front gardens are increasingly being paved over by developers, we wanted to chose to look at front gardens specifically to understand what their value and impact was both mentally, socially, and culturally. Front gardens are also a bridge between private and public life. Because they’re visible to neighbours and passersby, they may be able to contribute to the wellbeing of the community, too.

Our experiment evaluated physiological and psychological stress levels before and after adding plants to previously bare front gardens in Salford, Greater Manchester. We took measures of participants’ cortisol concentrations (sometimes referred to as “the stress hormone”) in their saliva, as well as self-reported perceived stress. Participants ranged in age from 21 to 86 and 64% of them were women.

We added two planters with ornamental plants – including petunias, violas, rosemary, lavender, azaleas, clematis, and either an amelanchier (snowy mespilus) tree or a dwarf juniper tree. These were chosen for their ease of maintenance and familiarity to most people in the UK. We also provided the 42 residents with compost, self-watering containers, a watering can and a trellis. The research team did all the planting to ensure that all the gardens were similar. Participants were given advice on how to maintain and water their plants and were permitted to add further plants or features. The new additions were as low maintenance as possible.

Lower Stress

Over a period of one year, we found that having plants in previously bare front gardens resulted in a 6% drop in residents’ perceived stress levels. This scale measures the degree to which situations in life are considered to be stressful by taking into account feelings of control and the ability to cope with stressors. The 6% decrease is equivalent to the long-term impact of eight weekly mindfulness sessions.

We also found statistically significant changes in participants’ salivary cortisol patterns. Cortisol is the body’s main stress response hormone, which can activate our “fight or flight” response, and can regulate sleep and energy levels. We need cortisol every day to be healthy, and typically concentrations peak as we wake up, and taper down to their lowest level at night. Disturbances to this pattern indicate that our bodies are under stress. We found that 24% of residents had a healthy daily cortisol pattern at the beginning of the study. This increased to 53% three months after adding the plants, suggesting better mental health in these participants.

Reasons for these changes can be explained by what participants told us during interviews. Residents found that the gardens had a positive influence on their outlook on life, with strong themes developing around more positive attitudes in general, a sense of pride, and greater motivation to improve the local environment. The gardens were also valued as a place to relax.

These aspects are likely to contribute to people’s personal resilience to stressful situations – and over time, have had an effect on their physiological response to stress, as measured by the cortisol concentrations. A small addition of a few plants in the front garden was a positive change to their home environment and the street.

All these wellbeing benefits of green spaces are understood to be based on two environmental psychology theories: attention restoration theory and stress reduction theory. Both psycho-evolutionary theories are based on Wilson’s biophilia hypothesis that humans have an innate affinity with the natural environment.

Attention restoration theory proposes that exposure to natural environments restores our ability to concentrate on tasks that require effort and directed attention. Spending time in natural environments demands less “brain power” so to speak, as we don’t need to focus as much on specific stimuli or tasks nor on suppressing distractions. Nature also provides us opportunities for reflection. Stress reduction theory proposes that natural environments provoke instantaneous emotional responses and fewer negative feelings than non-natural environments.

Our study’s results show the importance of even small green spaces for reducing stress, and may be important considerations in local planning, urban development, and health and social care. Integrated thinking between the built environment, environmental and health sectors is necessary.

The findings from this project also support the social case for more street-facing gardens and green spaces. For example, biophilic building standards, environmentally focused urban strategies, and walkable street initiatives could be significant ways of achieving this. Importantly for landscape architects and other professionals working with designed green spaces, there is scope for considerable impact on human perceptions, health and wellbeing.