Inbox and Environment News: Issue 483

February 14 - 20, 2021: Issue 483

Time Of Burran

Gadalung Marool (hot and dry) January - March

The behaviour of the male kangaroos becomes quite aggressive in this season, and it is a sign that the eating of meat is forbidden during this time. This is a health factor; because of the heat of the day meat does not keep, and the likelihood of food poisoning is apparent. The blooming of the Weetjellan (Acacia implexa) is an important sign that fires must not be lit unless they are well away from bushland and on sand only, and that there will be violent storms and heavy rain, so camping near creeks and rivers is not recommended.

Acacia implexa, commonly known as lightwood or hickory wattle, is a fast-growing Australian tree, the timber of which was used for furniture making. The wood is prized for its finish and strength. The foliage was used to make pulp and dye cloth. The Ngunnawal people of the ACT used the bark to make rope, string, medicine and for fish poison, the timber for tools, and the seeds to make flour.

It is widespread in eastern Australia from central coastal Queensland to southern Victoria, with outlying populations on the Atherton Tableland in northern Queensland and Tasmania's King Island. The tree is commonly found on fertile plains and in hilly country it is usually part of open forest communities and grows in shallow drier sandy and clay soils.

Acacia implexa flowers - photo by Donald Hobern.

Flight2Light 2021: 'How To'

Bush Blitz, is partnering with the Australasian Dark Sky Alliance to raise awareness of the impacts of light pollution on the night time environment.

The Flight2Light event aims to educate Australians about light pollution, the impact it has on wildlife and the simple ways they can reduce light pollution.

You can get involved in Flight2Light from the 6th-19th Feb 2021

Check at Bush Blitz for information about how to register to take part in this nation wide event, receive a participation certificate and the satisfaction of helping our environment.

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Pittwater Nature #4 Is Now Available

- The Pittwater River and the Barrenjoey sandspit

- How Tumbledown Dick hill Duffys Forest endangered bushland has been moved there from a site at Belrose

- The Sydney Wildlife Mobile Unit looks after native animals

- Plant Families 101: the Solanaceae /Nightshade Family.

- Prey and Predators on Bilgola Plateau

- Two birds that nest in hollows.

- Cicadas emerge at night.

Upcoming Activities For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment:

Sun 21 February 2021: 7.30 am Walk & Weed along the Narrabeen Lagoon catchment transverse walk.

Start at Oxford Falls walk for 3 1/2 hours, weed for 30min, continue 30min walk and car pool back to start.

Bring gloves and long handled screwdriver if available.

Walk grade: medium.

Bookings essential. Conny 0432 643 295

https://www.narrabeenlagoon.org.au/

Friends of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment are pleased to announce the next forum will be held on 22 Feb 2021 at 7 pm .

Presenter: Jayden Walsh

Jayden is a keen observer of nature and has some stunning photographs and information to share.

The focus will be on wildlife that lives near the Narrabeen Lagoon and that, if you are fortunate, you may see when on the Narrabeen Lagoon walkway.

For details on how to book for this event are on the website. At: https://www.narrabeenlagoon.org.au/Forums/forums.htm

Council's Waste Reduction Events

- DIY Beeswax Food Wraps - at the Tramshed Community Centre, Narrabeen

- Living Smart Short Course; Learn about the many ways you can reduce plastic and waste in your household, business or workplace -Tramshed Community Centre, Narrabeen

- Reusable Nappies Webinar

- Avalon Car Boot Sale

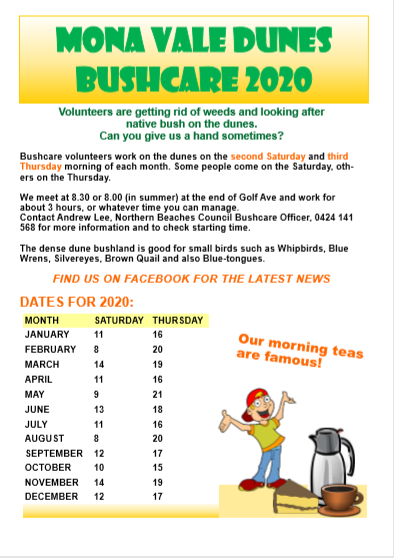

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Pittwater Reserves

Sydney Water Convicted And Fined $185,000 For Sewage Overflow

Misuse Of Mouse Baits Leads To Poisoning

Rat Poisons Are Killing Our Wildlife: Alternatives

BirdLife Australia is currently running a campaign highlighting the devastation being caused by poison to our wildlife. Rodentcides are an acknowledged but under-researched source of threat to many Aussie birds. If you missed BirdLife's rodenticide talk but would like to know more, share data and comment on the use of rodenticides in Australia please visit: https://www.actforbirds.org/ratpoison

Owls, kites and other birds of prey are dying from eating rats and mice that have ingested Second Generation rodent poisons. These household products – including Talon, Fast Action RatSak and The Big Cheese Fast Action brand rat and mice bait – have been banned from general public sale in the US, Canada and EU, but are available from supermarkets throughout Australia.

Australia is reviewing the use of these dangerous chemicals right now and you can make a submission to help get them off supermarket shelves and make sure only licenced operators can use them.

There are alternatives for household rodent control – find out more about the impacts of rat poison on our birds of prey and what you can do at the link above and by reading the information below.

Let’s get rat poison out of bird food chains.

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) – is currently asking Australians for their views on how rodent poisons are regulated.

Have your say by making a submission here.

Powerful Owl at Clareville - photo by Paul Wheeler

Pesticides that are designed to control pests such as mice and rats cane also kill our wildlife through either primary or secondary poisoning. Insecticides include pesticides (substances used to kill insects), rodenticides (substances used to kill rodents, such as rat poison), molluscicides (substances used to kill molluscs, such as snail baits), and herbicides (substances used to kill weeds).

Primary poisoning occurs when an animal ingests a pesticide directly – for example, a brushtail possum or antechinus eating rat bait. Secondary poisoning occurs when an animal eats another animal that has itself ingested a pesticide – for example, a greater sooty owl eating a rate that has been poisoned or an antechinus that had eaten rat bait.

Rodenticides are the most common and harmful pesticides to Australian wildlife. Though no comprehensive monitoring of non-target exposure of rodenticides has been conducted, numerous studies have documented the harm rodenticides do to native animals. In 2018, an Australian study found that anticoagulant rodenticides in particular are implicated in non-target wildlife poisoning in Australia, and warned Australia’s usage patterns and lax regulations “may increase the risk of non-target poisoning”.

Most rodenticides work by disrupting the normal coagulation (blood clotting) process, and are classified as either “first generation” / “multiple dose” or “second generation” / “single dose”, depending on how many doses are required for the poison to be lethal.

These anticoagulant rodenticides cause victims of anticoagulant rodenticides to suffer greatly before dying, as they work by inhibiting Vitamin K in the body, therefore disrupting the normal coagulation process. This results in poisoned animals suffering from uncontrolled bleeding or haemorrhaging, either spontaneously or from cuts or scratches. In the case of internally haemorrhaging, which is difficult to spot, the only sign of poisoning is that the animal is weak, or (occasionally) bleeding from the nose or mouth. Affected wildlife are also more likely to crash into structures and vehicles, and be killed by predators.

An animal has to eat a first generation rodenticide (e.g. warfarin, pindone, chlorophaninone, diphacinone) more than once in order to obtain a lethal dose. For this reason, second generation rodenticides (e.g. difenacoum, brodifacoum, bromadiolone and difethialone) are the most commonly used rodenticides. Second generation rodenticides only require a single dose to be consumed in order to be lethal, yet kill the animal slowly, meaning the animal keeps coming back. This results in the animal consuming many times more poison than a single lethal dose over the multiple days it takes them to die, during which time they are easy but lethal prey to predators. This is why second generation poisons tend to be much more acutely toxic to non-target wildlife, as they are much more likely to bioaccumulate and biomagnify, and clear very slowly from the body.

Species most at risk from poisons

Small Mammals

Small mammals including possums and bandicoots often consume poisons such as snail bait, or rat bait that has been laid out to attract and kill rats, mice, and rabbits. Poisons such as pindone are often added to oats or carrots, and lead to a slow, painful death of internal bleeding. Australian possums often consume rat bait such as warfarin, which causes extensive internal bleeding, usually resulting in death.

There is a very poor chance of survival. Possums are also known to consume slug bait, which results in a prolonged painful death mainly from neurological effects. There is no treatment.

Small mammals can also be poisoned by insecticides. Possums, for example, can ingest these poisons when consuming fruit from a tree that has been sprayed with insecticide. Rescued by a WIRES carer, the brushtail possum joey pictured below was suffering from suspected insecticide poisoning. Though coughing up blood, luckily the joey did not ingest a lethal dose as he survived in care and was later released.

Large Mammals

Despite their size, large mammals including wallabies, kangaroos and wombats can also fall victim to pesticide poisoning. Wallabies and kangaroos have been known to suffer from rodenticide poisoning, while poisons often ingested by wombats include rat bait from farm sheds, and sodium fluroacetate (1080) laid out to kill pests such as cats and foxes.

Australian mammals are also impacted by the use of insecticides. DDT, although a banned substance, has been reported as killing marsupials.

Birds

Birds have a high metabolic rate and therefore succumb quickly to poisons. Australian birds of prey – owls (such as the southern boobook) and diurnal raptors (such as kestrels) – can be killed by internal bleeding when they eat rodents that have ingested rat bait. A 2018 Western Australian study determined that 73% of southern boobook owls found dead or were found to have anticoagulant rodenticides in their systems, and that raptors with larger home ranges and more mammal-based diets may be at a greater risk of anticoagulant rodenticide exposure.

Insectivorous birds will often eat insects sprayed with insecticides, and a few different species of birds may be affected at the same time. Unfortunately little can be done and death most often results.

Organophosphates are the most widely used insecticide in Australia. Birds are very susceptible to organophosphates, which are nerve toxins that damage the nervous system, with poisoning occurring through the skin, inhalation, and ingestion. Organophosphates can cause secondary poisoning in wild birds which ingest sprayed insects. Often various species of insectivorous birds are affected at the same time as they come down to eat the dying insects. After a bird is poisoned, death usually occurs rapidly. Raptors have also been deliberately or inadvertently poisoned when organophosphates have been applied to a carcass to poison crows.

Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) are persistent, bio-accumulative pesticides that include DDT, dieldrin, heptachlor and chlordane. OPC’s have been used extensively in the agriculture industry since the 1940s. Some of the more common product names include Hortico Dieldrin Dust, Shell Dieldrex and Yates Garden Dust. Although no OCP’s are currently registered for use in the home environment in Australia, many of these products still remain in use on farms, in business premises and households. OCP poisons remain highly toxic in the environment for many years impacting on humans, animals, birds and especially aquatic life. They can have serious short-term and long-term impacts at low concentrations. In addition, non-lethal effects such as immune system and reproductive damage of some of these pesticides may also be significant. Birds are particularly sensitive to these pesticides, and there have even been occasions where the deliberate poisoning of birds has occurred. Tawny frogmouths are most often poisoned with OCP’s. The poisons are stored in fat deposits and gradually increase over time. At times of food scarcity, or during any stressful period, such as breeding season or any changes to their environment, the fat stores are metabolised, and with it, the poison load in their blood streams reaches acute levels, causing death.

Although herbicides, or weed killers, are designed to kill plants, some are toxic to birds. Common herbicide glyphosate (Roundup) will cause severe eye irritation in birds if they come into contact with the spray. Herbicides also have the impact of removing food plants that birds, or their insect food supply, rely on. Birds can also readily fall victim to snail baits, either via primary or secondary poisoning.

Reptiles and Amphibians

As vertebrate species, reptiles and amphibians are also at risk of pesticides. Though less is known about the effects of pesticides on reptiles and amphibians, these animals have been known to fall victim to pesticide poisoning. Blue-tongue lizards, for example, often consume rat bait and die of internal bleeding. A 2018 Australian study also found that reptiles may be important vectors (transporters) of rodenticides in Australia.

How to keep pests away and keep wildlife safe

Remember, pesticides are formulated to be tasty and alluring to the target species, but other species find them enticing, too. It is safest for wildlife, pets and people for us to not use any pesticides, and prevent or deter the presence of pests practically, rather than attempt to eliminate them chemically.

Tips to prevent and deter wildlife deaths from poisoning:

- Deter rats and mice around your property by simply cleaning up; removing rubbish, keeping animal feed well contained and indoors, picking up fallen fruits and vegetation, and using chicken feeders removes potential food sources.

- Seal up holes and in your walls and roof to reduce the amount of rodent-friendly habitat in your house.

- Replace palms with native trees; palm trees are a favourite hideout for black rats, while native trees provide ideal habitat for native predators like owls and hawks which help to control rodent populations.

- Set traps with care in a safe, covered spot, away from the reach of children, pets and wildlife. Two of the most effective yet safe baits are peanut butter and pumpkin seeds.

- To control slugs, terracotta or ceramic plant pots can be placed upside down in the garden or aviary. Slugs and snails will seek the dark, damp area this creates, and can be collected daily. They can then be drowned in a jar of soapy water. You can also sink a jar or dish into the soil and fill it with beer. The slugs are attracted to the yeast in the beer, fall in and then drown.

If turning to pesticides as a last resort:

- Use only animal-safe slug baits.

- Place tamper-proof bait stations out of reach of wildlife.

- Avoid using loose whether pellets or poison grain, present the highest risk, the latter being particularly attractive to seed-eating birds and to many small mammal species.

- Read the label and use as instructed.

- Avoid products containing second generation products difenacoum, brodifacoum, bromadiolone and difethialone, which are long-lasting and much more likely to unintentionally poison wildlife via secondary poisoning.

- Cover individual fruits when spraying fruit trees with insecticides.

Poisons kill dogs too

Because of their poisonous nature, pesticides pose a risk to animals and people alike, including pets and children. Roaming pets like cats and dogs are most at risk of being poisoned, with one 2016 study at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences finding that one in five dogs had rat poison in its body, and a 2011 study by the Humane Society in the United States finding that 74% of their pet poisoning cases are due to second-generation anticoagulants such as rat baits.

It is best to avoid the use of all pesticides, or otherwise use them sparingly, carefully and only after researching each poison and its correct usage. Always supervise pets and children, keep poisons locked out of their reach, and be vigilant in public spaces where pesticides may have accumulated, e.g. poisons can accumulate in streams or puddles where herbicides have recently been sprayed.

If you suspect your pet has been poisoned, seek veterinary help immediately.

If you suspect your child or another adult has been poisoned, do not induce vomiting and call the NSW Poisons Information Centre on 13 11 26 for 24/7 medical advice, Australia-wide.

References

Lohr, M. T. & Davis, R. A. 2018, Anticoagulant rodenticide use, non-target impacts and regulation: A case study from Australia, Science of The Total Environment, vol. 634, pp. 1372-1384.

Lohr, M. T. 2018, Anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in an Australian predatory bird increases with proximity to developed habitat, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 643, pp.134-144.

Lohr, M. T. 2018, Anticoagulant Rodenticides: Implications for Wildlife Rehabilitation, conference paper, Australian Wildlife Rehabiliation Conference, awrc.org.au

Olerud, S., Pedersen, J. & Kull, E. P. 2009, Prevalence of superwarfarins in dogs – a survey of background levels in liver samples of autopsied dogs. Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Life Sciences, Department of Sports and Family Animal Medicine, Section for Small Animal Diseases.

Healthy Wildlife, Healthy Lives, 2017, Rodenticides and Wildlife, healthywildlife.com.au

Society for the Preservation of Raptors Inc. 2019, Raptor Fact Sheet: Eliminate Rats and Mice, Not Wildlife!, raptor.org.au/factsheetpests.pdf

W.I.R.E.S. Poisons and baits don't just kill rats.

.jpg?timestamp=1590728675788)

Barking Owl (Ninox connivens connivens)- photo by Julie Edgley - this nocturnal animal will eat mice and so become a victim of poisons through them

Bents Basin State Conservation Area: Have Your Say

Closes March 7, 2021

National Parks and Wildlife Service is seeking feedback on the draft plan of management for Bents Basin State Conservation Area and Gulguer Nature Reserve.

The Bents Basin State Conservation Area and Gulguer Nature Reserve Draft Plan of Management is currently on public exhibition.

Once adopted, the plan will replace the Bents Basin State Conservation Area statement of management intent and the Gulguer Nature Reserve statement of management intent, which were approved in 2014.

Key management directions in this plan include:

- strategies for the protection of natural values

- strategies to improve the management of Aboriginal cultural heritage and shared heritage values

- strategies to improve visitor experiences and manage increasing use.

The draft visitor facilities concept plans, including details of visitor facility upgrades, are also available for comment.

You can provide your written submission in any of the following ways:

Post your written submission to:

Manager Planning

Evaluation and Assessment

Locked Bag 5022

Parramatta NSW 2124

Email your submission to: npws.parkplanning@environment.nsw.gov.au

Make a submission online by using the online form here

Volunteers Needed For Great Inland Glossy Count: February 2021

Postponed from late last year the NSW Saving our Species program is now calling for community volunteers to become 'cockatoo counters' and help be part of the Great Inland Glossy Count this February.

National Parks and Wildlife Service Senior Project Officer Adam Fawcett said the count was set to go and anyone can be a part of it.

"Bird lovers, citizen scientists or anyone with an interest in this beautiful threatened species, are needed to survey glossy black cockatoo populations at three key sites around inland NSW.

"Listed as vulnerable in New South Wales, glossies are easily spotted with their distinctive red markings and this cockatoo count will help our scientists understand more about this threatened bird," he said.

This is the second time the Great Inland Glossy Count has occurred. In 2019 seventy volunteers participated and counted over 700 glossy black cockatoos across inland NSW.

The count is part of a wider project to conserve the species at three key sites: the Pilliga Forests, Goonoo National Park and Goobang National Park and surrounding landscapes.

The dates for the 2021 surveys of what is fast becoming an annual cockatoo count are:

- 13 February – Pilliga Forests

- 20 February – Goonoo National Park

- 27 February – Goobang National Park and surrounds

"We are hoping to get 100 volunteers this year and what a great opportunity to get out to some of our amazing national parks and state forests, sit back and watch a threatened species in its natural habitat," Mr Fawcett said.

Volunteers will need to pre-register using the Department of Planning Industry and Environment's Volunteer Portal and will be required to follow COVID safety guidelines.

Family members are encouraged to register to volunteer together and will be stationed at one dam on their chosen weekend to count glossy black cockatoos as they come into known watering holes.

"We are asking volunteers to setup at their survey site an hour or so before dusk and wait as glossy black cockatoos fly in for water.

"The only requirements are the ability to make your way to a dam allocated by the Saving our Species team and to bring a pair of binoculars, a comfy chair and a notepad.

"Many of our seasoned participants make quite an event out of the evening, with cheese platters and other goodies a regular feature. It is a pretty amazing when you get a large flock of this threatened species coming into a waterhole to drink and we love that we are able to give people this opportunity to get involved in threatened species conservation," Mr Fawcett said.

The project is funded by the NSW Government's Saving our Species program and the NSW Environmental Trust, and is led by Central West Local Land Services in partnership with National Parks and Wildlife Service, NSW Forest Corporation, Dubbo Field Naturalists, Australian Wildlife Conservancy and the land owners and managers within these areas.

Shifting Attitudes To Recycling Sees 5 Billion Drink Containers Returned

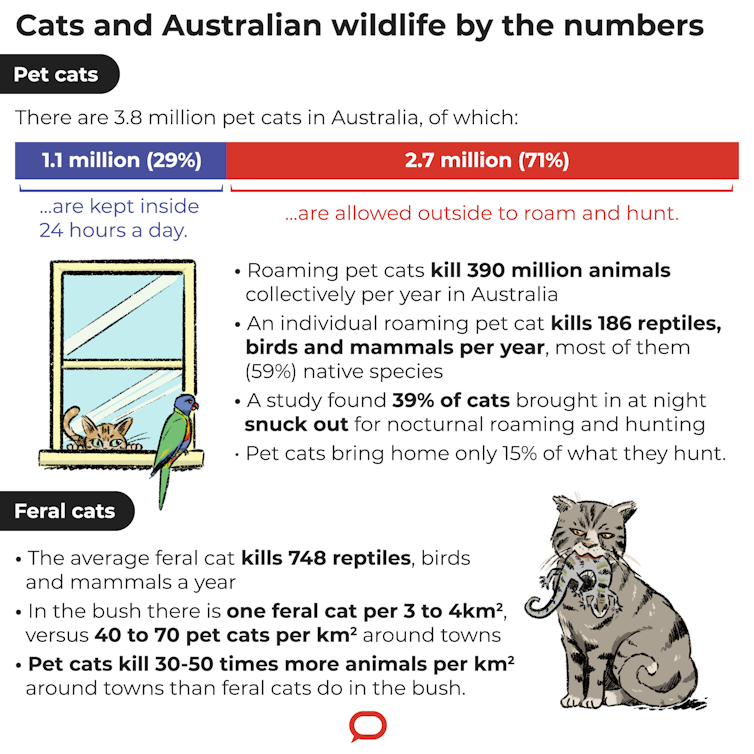

Australia must control its killer cat problem. A major new report explains how, but doesn't go far enough

Australia is teeming with cats. While cats make great pets, and can bring owners emotional, psychological and health benefits, the animals are a scourge on native wildlife.

Cats kill a staggering 1.7 billion native animals each year, and have played a major role in most of Australia’s 34 mammal extinctions. They continue to pose an extinction threat to at least another 120 species.

A recent parliamentary inquiry into the problem of feral and pet cats in Australia has affirmed the issue is indeed of national significance. The final report, released last week, calls for a heightened, more effective, multi-pronged and coordinated policy, management and research response.

As ecologists, we’ve collectively spent more than 50 years researching Australia’s cat dilemma. We welcome most of the report’s recommendations, but in some areas it doesn’t go far enough, missing major opportunities to make a difference.

Night Curfews Aren’t Good Enough

The report recommends Australia’s 3.8 million pet cats be subject to night-time curfews. This measure would benefit native nocturnal mammals, but won’t save birds and reptiles, which are primarily active during the day.

Pet cats kill 83 million native reptiles and 80 million native birds in Australia each year. From a wildlife perspective, keeping pet cats contained 24/7 is the only responsible option.

It’s clearly possible: one third of Australian pet cat owners already keep their pets contained all the time.

Stopping pet cats from roaming is also good for the cats, which live longer, safer lives when kept exclusively indoors. It would also substantially reduce the number of people falling ill from cat-dependent diseases each year.

Read more: Cats carry diseases that can be deadly to humans, and it's costing Australia $6 billion every year

Other strategies for improving pet cat management proposed in the report include pet cat registration, subsidised programs for early age desexing, public education campaigns to promote responsible pet cat ownership, and improving the consistency of rules and legislation nationally.

The report is also unambiguously opposed to “trap-neuter-release” programs, in which un-owned cats in urban areas are desexed and then released. We agree with this finding, as these programs aren’t effective at reducing the population of stray cats, nor preventing those cats from killing wildlife and spreading disease.

We Need More Wildlife Havens

One of the inquiry’s flagship recommendations is a national conservation project dubbed “Project Noah”. This would involve an ambitious expansion of Australia’s existing network of reserves free from introduced predators, both on islands and in mainland fenced areas. The reserves provide havens — or a fleet of “arks” — for vulnerable native wildlife.

This measure is vital. 2019 research found Australia has more than 65 native mammal species and subspecies that can’t persist, or struggle to persist, in places with even very low numbers of cats or foxes. This includes the bilby, numbat, quokka, dibbler and black-footed rock wallaby.

Australia already has more than 125 havens, 100 of which are islands. These have prevented 13 mammal species from going extinct, such as boodies and greater stick-nest rats. In total, these havens have protected populations of 40 mammal species susceptible to cats and foxes.

This is a good start, but we need more investment in havens to prevent extinctions. More than 25 species are highly sensitive to cat and fox predation, but aren’t yet protected in the haven network. This includes the central rock-rat, which is more likely than not to become extinct within 20 years without new action.

What’s more, some species, such as the long-nosed potoroo, exist in just one haven. To avoid issues such as inbreeding and to ensure disasters like a fire at any single haven don’t take out an entire species, each species should be represented across several havens, in reasonable population sizes.

The report didn’t specify how the havens network should be expanded. But 2019 research found to get each species needing protection into at least three havens, Australia requires at least 35 new, strategically located islands or mainland fenced areas.

What About The Rest Of The Country?

Havens cover less than 1% of Australia. So what we do in the other 99% of the landscape — including across conservation reserves like national parks — is vital.

Yet the parliamentary inquiry report lacks clear recommendations to expand cat control more broadly, including at important conservation sites such as in Kakadu National Park.

The report reaffirms the need to cull feral cats, and to set new targets for culling, without specifying what those targets are. We agree some culling is important, especially at sites with very vulnerable threatened wildlife.

But in many parts of Australia, broad-scale habitat management is a more cost-effective way to reduce cat harm. This involves making habitat less suitable for cats and more suitable for native wildlife, for example, by reducing rabbit numbers, fire frequency and grazing by feral herbivores such as cattle and horses.

Research has shown fewer rabbits leads to fewer cats. Rabbits are a favoured prey of many cats, so they boost feral cat numbers, which then also hunt native wildlife.

Read more: One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

And cats gravitate to areas with less vegetation because it’s easier to catch prey. These areas include those with frequent fires, or where feral herbivores have reduced vegetation through grazing and trampling.

Better habitat with more vegetation gives native animals places to hide from predators, and more food and shelter. It’s a bit like giving the last little pig a house of bricks instead of trying to fist-fight the wolf.

A Major Step Forward

Over the past two decades, Australia has slowly woken up to the damage cats cause to nature. This has led to more research, management and policy to address the problem.

Some state governments, environment groups and scientists have worked hard to develop feral cat control options, and the 2015 Australian Threatened Species Strategy did much to focus national attention and resourcing to the issue.

Read more: Don't let them out: 15 ways to keep your indoor cat happy

The parliamentary inquiry is a major step forward, and many recommendations are sound. But overall, its recommendations call for incremental improvement.

Australia’s laws clearly fail to provide a safety net for wildlife. The cat issue is part of a larger problem with how we manage habitat, biodiversity and threats to nature – and fixing that requires wholesale change.![]()

Sarah Legge, Professor, Australian National University; Chris Dickman, Professor in Terrestrial Ecology, University of Sydney; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; John Woinarski, Professor (conservation biology), Charles Darwin University, and Tida Nou, Project officer, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The US jumps on board the electric vehicle revolution, leaving Australia in the dust

The Morrison government on Friday released a plan to reduce carbon emissions from Australia’s road transport sector. Controversially, it ruled out consumer incentives to encourage electric vehicle uptake. The disappointing document is not the electric vehicle jump-start the country sorely needs.

In contrast, the United States has recently gone all-in on electric vehicles. Like leaders in many developed economies, President Joe Biden will offer consumer incentives to encourage uptake of the technology. The nation’s entire government vehicle fleet will also transition to electric vehicles made in the US.

Electric vehicles are crucial to delivering the substantial emissions reductions required to reach net-zero by 2050 – a goal Prime Minister Scott Morrison now says he supports.

It begs the question: when will Australian governments wake up and support the electric vehicle revolution?

A Do-Nothing Approach

In Australia in 2020, electric vehicles comprised just 0.6% of new vehicle sales – well below the global average of 4.2%.

Overseas, electric vehicle uptake has been boosted by consumer incentives such as tax exemptions, toll road discounts, rebates on charging stations and subsidies to reduce upfront purchase costs.

And past advice to government has stated financial incentives are the best way to get more electric vehicles on the road.

But government backbenchers, including Liberal MP Craig Kelly, have previously warned against any subsidies to make electric cars cost-competitive against traditional cars.

Read more: Scott Morrison has embraced net-zero emissions – now it's time to walk the talk

Releasing the government’s Future Fuels Strategy discussion paper on Friday, Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor said subsidies for electric vehicles did not represent good value for money.

(As argued here, the claim is flawed because it ignores the international emissions produced by imported vehicle fuel).

The Morrison government instead plans to encourage business fleets to transition to electric vehicles, saying businesses accounted for around 40% of new light vehicle sales in 2020.

The government has also failed to implement fuel efficiency standards, despite in 2015 establishing a ministerial forum to do so.

The approach contrasts starkly with that taken by the Biden administration.

Biden’s Electrifying Plan

Cars, buses and trucks are the largest source of emissions in the US. To tackle this, Biden has proposed to:

offer new consumer incentives to support electric vehicle purchases, beyond the existing $US7,500 tax credit

electrify the government’s 650,000-strong fleet

establish ambitious fuel economy standards

build an extra 500,000 public charging stations for electric vehicles by 2030

provide incentives for US manufacturers to build electric vehicles and parts

make all new US-built buses zero-emissions by 2030, and electrify the nation’s 500,000 school buses

invest $US5 billion into battery research to further reduce electric vehicle prices

ensure every American city with 100,000 or more residents has high-quality, zero-emissions public transport options.

And by committing to carbon-free electricity generation by 2035, the Biden administration is also ensuring renewable energy will power this electric fleet.

This combined support for electric vehicles and renewable energy is crucial if the US is to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Read more: Clean, green machines: the truth about electric vehicle emissions

Made In America

US companies are getting on board to avoid missing out on the electric vehicle revolution.

The day after Biden announced his fleet transition plan, General Motors (GM) - the largest US vehicle manufacturer and a major employer - announced it would stop selling fossil fuel vehicles by 2035 and be carbon-neutral by 2040.

This aligns with plans by the US states of California and Massachusetts to ban the sale of fossil fuel vehicles by 2035.

GM is serious about the transition, committing $US27 billion and planning at least 30 new electric vehicle models by 2025. And on Friday, the Ford Motor Company said it would double its investment in vehicle electrification to $US22 billion.

Opportunities And Challenges Abound

Using government fleets to accelerate the electric vehicle transition is smart and strategic, because it:

allows consumers to see the technology in use

creates market certainty

encourages private fleets to transition

enables the development of a future second-hand electric vehicle market, once fleet vehicles are replaced.

Biden’s fleet plan includes a clear target, ensuring it stimulates the economy and supports his broader goal to create one million new US automotive jobs. Prioritising local manufacturing of vehicles, batteries and other components is key to maximising the benefits of his electric vehicle revolution.

On face value, the Morrison government’s business fleet plan has merit. But unlike the US approach, it does not involve a clear target and funding allocated to the initiative is relatively meagre.

So it’s unlikely to make much difference or put Australia on par with its international peers.

Australian Governments Must Wake Up

Compounding the absence of consumer incentives to encourage uptake in Australia, some states are mulling taxing electric vehicles before the market has been established.

Our research shows this could not only delay electric vehicle uptake, but jeopardise Australia’s chances of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

Australia is already a world leader in building fast-charging hardware, and manufactures electric buses and trucks. We could also lead the global electric vehicle supply chain, due to our significant reserves of lithium, copper and nickel.

Despite these opportunities, the continuing lack of national leadership means the country is missing out on many economic benefits the electric vehicle revolution can bring.

Australia should adopt a Biden-inspired electric vehicle agenda. Without it, we will miss our climate targets, and the opportunity for thousands of new jobs.

Read more: Wrong way, go back: a proposed new tax on electric vehicles is a bad idea ![]()

Jake Whitehead, Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellow & Tritum E-Mobility Fellow, The University of Queensland; Dia Adhikari Smith, E-Mobility Research Fellow, The University of Queensland, and Thara Philip, E-Mobility Doctoral Researcher, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

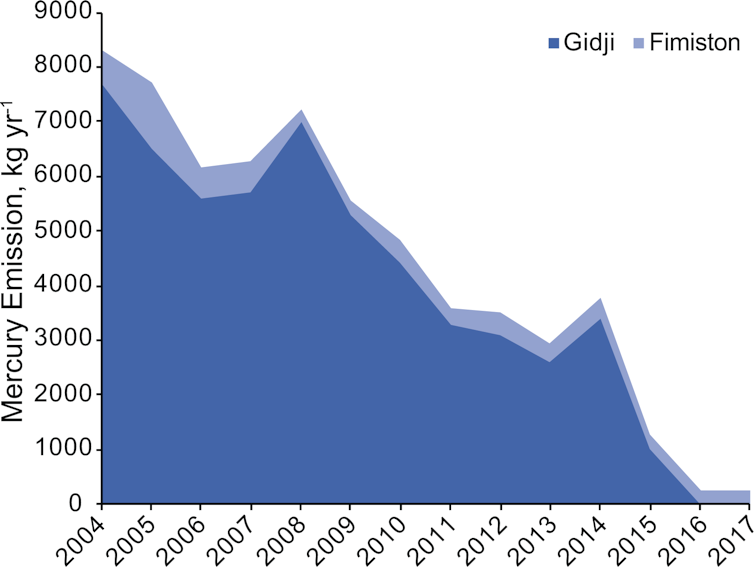

Australia’s gold industry stamped out mercury pollution — now it's coal's turn

Mercury is a nasty toxin that harms humans and ecosystems. Most human exposure comes from eating contaminated fish and other seafood. But how does mercury enter the Australian environment in the first place?

Our recent research dug into official data and past research to answer this question.

In some rare good news for the environment, it turns out one Australian industry – gold production – has brought mercury emissions down to almost zero. But more can be done about mercury emitted from coal-fired power stations.

Australia is one of the few developed countries yet to ratify the United Nations’ Minamata Convention on Mercury, which aims to reduce mercury in the environment. But once we deal with emissions from coal burning, we’ll be closer than ever to addressing the problem.

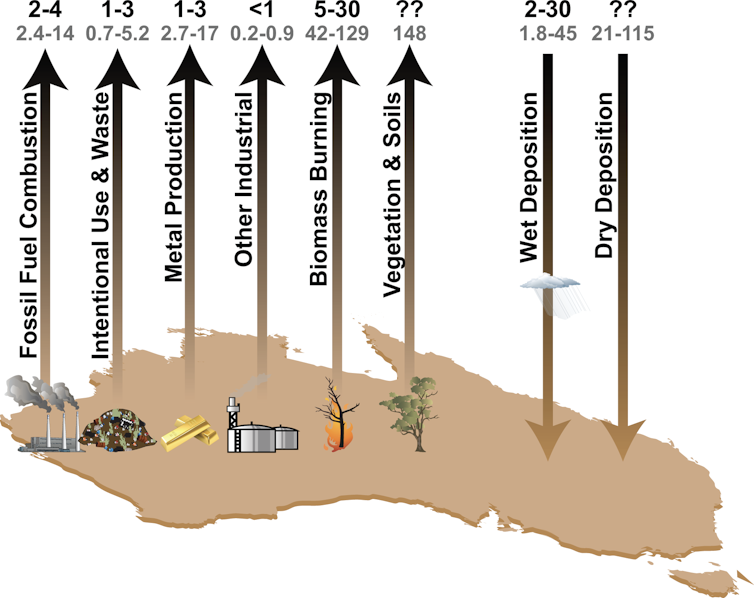

Where Does Mercury Pollution Come From?

Mercury is a heavy metal that cycles between the atmosphere, ocean and land. It occurs naturally but can be toxic to humans and wildlife.

Most human-caused mercury emissions come from the burning of fossil fuels and the mining and production of gold and other metals.

What’s more, items such as light bulbs and thermometers dumped in landfill can release mercury 30-50 years later.

Read more: Climate change and overfishing are boosting toxic mercury levels in fish

Once in the air, mercury can float around for months, crossing oceans and continents to end up back on the ground, far from where it was emitted.

It’s eventually taken up by soils, water and plants, then slowly released back to the atmosphere.

A Success Story

Estimates vary on the exact amount of mercury that Australian activities release to the air. Studies we reviewed put the figure at anywhere between 8 and 30 tonnes each year.

Our analysis shows the figure is likely at the low end of that range – largely due to a single success story.

In 2006, a gold production facility in Kalgoorlie was thought to cause half of Australia’s industrial mercury emissions. The massive operation includes the Fimiston Open Pit, or “Super Pit”, purportedly so large it can be seen from space.

Gold ore naturally contains mercury. To extract the gold, the ore is typically roasted at temperatures of up to 600℃. During this process, the mercury escapes into the atmosphere. Most mercury pollution from Australia’s gold industry came from a single roaster at the Kalgoorlie site.

But over one decade, mercury emissions from the operation dropped from more than 8 tonnes to just 250 kilograms. This was largely due to a technology upgrade in 2015, when the roaster was replaced by a grinding process.

This success means coal-fired power plants are now Australia’s largest controllable source of mercury emissions. They emit between two and four tonnes of mercury every year (along with other air pollutants).

Other Sources Of Mercury Emissions

Other natural and human activities release mercury into the air. They include:

Bushfires: Mercury is usually released to the environment over decades. But the process can be much more rapid if the vegetation burns in a bushfire.

Our research found most estimates of bushfire emissions fall between 4 and 40 tonnes each year. But this work relied on measurements from overseas. New measurements from Australian ecosystems suggests past estimates are probably too high – possibly due to lower mercury concentrations in some Australian vegetation.

Soils and unburnt vegtation: Only one study has calculated the mercury released from Australian soils and unburnt vegetation, which it put at a whopping 74 to 222 tonnes per year.

Read more: Plants safely store toxic mercury. Bushfires and climate change bring it back into our environment

When that research was published in 2012, there were no Australian data to test the model behind these numbers. We still don’t have many measurements, but most data we do have show Australian soils and vegetation take up about as much mercury as they release.

The one exception is “enriched” soils, which contain more mercury than other soils. This is because they are located over natural mineral belts and at former mining sites. At one location in northern New South Wales, enriched soils emitted more than 100 times as much mercury as nearby unenriched soils.

Mercury from elsewhere: Mercury released by other countries can travel to Australia in the air. The levels are tough to quantify, but we are currently using models to produce an estimate.

It’s Time To Act

Even with our new, lower estimates, Australia’s per capita mercury emissions remain higher than the global average, likely due to our reliance on coal burning. Technology can lower these emissions.

Some mercury emitted by power plants isn’t in the air for long before it falls to Earth. This can harm nearby people and ecosystems.

The federal government recently banned mercury-containing pesticides used in sugar cane farming. With gold production also taken care of, reducing mercury emissions from power plants is the logical next step.

It’s also time for Australia to formally commit to the Minamata Convention. Once we ratify the deal, we’ll be bound to control mercury emissions under international law – and that’s good for humans and wildlife everywhere.

Read more: Ban on toxic mercury looms in sugar cane farming, but Australia still has a way to go ![]()

Jenny Fisher, Associate Professor in Atmospheric Chemistry, University of Wollongong and Peter Nelson, Professor Emeritus of Environmental Studies, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Hundreds of fish species, including many that humans eat, are consuming plastic

Trillions of barely visible pieces of plastic are floating in the world’s oceans, from surface waters to the deep seas. These particles, known as microplastics, typically form when larger plastic objects such as shopping bags and food containers break down.

Researchers are concerned about microplastics because they are minuscule, widely distributed and easy for wildlife to consume, accidentally or intentionally. We study marine science and animal behavior, and wanted to understand the scale of this problem. In a newly published study that we conducted with ecologist Elliott Hazen, we examined how marine fish – including species consumed by humans – are ingesting synthetic particles of all sizes.

In the broadest review on this topic that has been carried out to date, we found that, so far, 386 marine fish species are known to have ingested plastic debris, including 210 species that are commercially important. But findings of fish consuming plastic are on the rise. We speculate that this could be happening both because detection methods for microplastics are improving and because ocean plastic pollution continues to increase.

Solving The Plastics Puzzle

It’s not news that wild creatures ingest plastic. The first scientific observation of this problem came from the stomach of a seabird in 1969. Three years later, scientists reported that fish off the coast of southern New England were consuming tiny plastic particles.

Since then, well over 100 scientific papers have described plastic ingestion in numerous species of fish. But each study has only contributed a small piece of a very important puzzle. To see the problem more clearly, we had to put those pieces together.

This story is part of Oceans 21

Our series on the global ocean opened with five in depth profiles. Look out for new articles on the state of our oceans in the lead up to the UN’s next climate conference, COP26. The series is brought to you by The Conversation’s international network.

We did this by creating the largest existing database on plastic ingestion by marine fish, drawing on every scientific study of the problem published from 1972 to 2019. We collected a range of information from each study, including what fish species it examined, the number of fish that had eaten plastic and when those fish were caught. Because some regions of the ocean have more plastic pollution than others, we also examined where the fish were found.

For each species in our database, we identified its diet, habitat and feeding behaviors – for example, whether it preyed on other fish or grazed on algae. By analyzing this data as a whole, we wanted to understand not only how many fish were eating plastic, but also what factors might cause them to do so. The trends that we found were surprising and concerning.

A Global Problem

Our research revealed that marine fish are ingesting plastic around the globe. According to the 129 scientific papers in our database, researchers have studied this problem in 555 fish species worldwide. We were alarmed to find that more than two-thirds of those species had ingested plastic.

One important caveat is that not all of these studies looked for microplastics. This is likely because finding microplastics requires specialized equipment, like microscopes, or use of more complex techniques. But when researchers did look for microplastics, they found five times more plastic per individual fish than when they only looked for larger pieces. Studies that were able to detect this previously invisible threat revealed that plastic ingestion was higher than we had originally anticipated.

Our review of four decades of research indicates that fish consumption of plastic is increasing. Just since an international assessment conducted for the United Nations in 2016, the number of marine fish species found with plastic has quadrupled.

Similarly, in the last decade alone, the proportion of fish consuming plastic has doubled across all species. Studies published from 2010-2013 found that an average of 15% of the fish sampled contained plastic; in studies published from 2017-2019, that share rose to 33%.

We think there are two reasons for this trend. First, scientific techniques for detecting microplastics have improved substantially in the past five years. Many of the earlier studies we examined may not have found microplastics because researchers couldn’t see them.

Second, it is also likely that fish are actually consuming more plastic over time as ocean plastic pollution increases globally. If this is true, we expect the situation to worsen. Multiple studies that have sought to quantify plastic waste project that the amount of plastic pollution in the ocean will continue to increase over the next several decades.

Risk Factors

While our findings may make it seem as though fish in the ocean are stuffed to the gills with plastic, the situation is more complex. In our review, almost one-third of the species studied were not found to have consumed plastic. And even in studies that did report plastic ingestion, researchers did not find plastic in every individual fish. Across studies and species, about one in four fish contained plastics – a fraction that seems to be growing with time. Fish that did consume plastic typically had only one or two pieces in their stomachs.

In our view, this indicates that plastic ingestion by fish may be widespread, but it does not seem to be universal. Nor does it appear random. On the contrary, we were able to predict which species were more likely to eat plastic based on their environment, habitat and feeding behavior.

For example, fishes such as sharks, grouper and tuna that hunt other fishes or marine organisms as food were more likely to ingest plastic. Consequently, species higher on the food chain were at greater risk.

We were not surprised that the amount of plastic that fish consumed also seemed to depend on how much plastic was in their environment. Species that live in ocean regions known to have a lot of plastic pollution, such as the Mediterranean Sea and the coasts of East Asia, were found with more plastic in their stomachs.

Effects Of A Plastic Diet

This is not just a wildlife conservation issue. Researchers don’t know very much about the effects of ingesting plastic on fish or humans. However, there is evidence that that microplastics and even smaller particles called nanoplastics can move from a fish’s stomach to its muscle tissue, which is the part that humans typically eat. Our findings highlight the need for studies analyzing how frequently plastics transfer from fish to humans, and their potential effects on the human body.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Our review is a step toward understanding the global problem of ocean plastic pollution. Of more than 20,000 marine fish species, only roughly 2% have been tested for plastic consumption. And many reaches of the ocean remain to be examined. Nonetheless, what’s now clear to us is that “out of sight, out of mind” is not an effective response to ocean pollution – especially when it may end up on our plates.![]()

Alexandra McInturf, PhD Candidate in Animal Behavior, University of California, Davis and Matthew Savoca, Postdoctoral researcher, Stanford University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Cicadas And Crickets Still Singing In Pittwater: Late Summer Bush Songs

Have you noticed that the deafening noise of a million million Black Prince cicadas we had just a few weeks ago is not so noisy now? We had so many at our place as we have a lot of spotted gum trees - it was so LOUD some days I had to close the doors to stop my ears ringing. Durinmg the past few weeks they're a lot quieter though - I think it may be because all the currawongs and magpies are feeding them to their newly fledged youngsters - they LOVE cicadas.

This year we have seen:

Yellow Monday Cicada

Black Prince Cicada

Have you heard all the crickets singing at night?

There seems to be a lot of crickets this year, so many so that this one came onto my desk here one night during this week and then spent about 10 minutes jumping around all over the place.

Crickets live all over Australia and you have probably heard them - but maybe not seen one. The most common is the Black Field Cricket. Only the male of this species 'chirp' by rubbing their wings together. They do it to attract females, to woo them, and to warn off other male competitors. They grow to about 2.5cm long. Black Field Crickets lay their eggs around April. A female can lay up to 1,500 to 2,000 eggs and she lays them from late Summer to late Autumn. These eggs remain dormant over the Winter and hatch in Spring.

Young crickets, known as nymphs, grow slowly through 9 to 10 nymph stages as they gradually develop into adults. Juvenile Black Field Crickets are similar in appearance to adults but lack wings and have a distinctive white band around their middle.

Normally, Black Field Crickets are mostly a ground living insect, but will take to the air when numbers are too great and food becomes scarce. Crickets usually live outside but may come inside to get away from waterlogged ground after rains, or when the weather turns very cold.

Normally, crickets feed on decaying plant material and insect remains, and are prey to birds, mice, frogs, possums and many other creatures. They are an important animal in the food chain. You can tell a Short-Horned grasshopper from a cricket by the size of their antennae. Crickets have longer antennae than these grasshoppers. Most grasshoppers also feed on plant material, whereas crickets are omnivores. Also crickets are mainly nocturnal, whereas Short-Horned grasshoppers are active during the day.

Black Field Crickets are good buddies to have in your garden as they will help aerate your soil, which helps water penetrate into it.

Did you know?; Crickets have 'ears' in their legs just below their knees. The ear drums, one on each foreleg, are sensitive membranes which act as receivers of differences in pressure and can help crickets find a mate, be forewarned about predators or locate prey.

The most common crickets in backyards are the House Cricket, Mole Cricket and Black Field Cricket. The King cricket is large and flightless and can devour funnel web spiders with its enormous, terrifying-looking mouth parts. It's usually only found in rainforests. You can recognise crickets and grasshoppers by their 'song' which they make by rubbing parts of each wing together.

Photos by A J Guesdon, information courtesy of Backyard Buddies - more great stuff at: www.backyardbuddies.org.au

THE CICADA ORCHESTRA. When the gum leaves all hang drooping,

When the gum leaves all hang drooping,

And every bird is still,

There comes from each leafy covert,

A droning loud and shrill.

'Zum, zum, zum, I'm a Floury Baker!

Hark to my double-drum;

I can drone by the hour with ceaseless power,

And a zum, zum, zum, zum, zum.'

The hot air seems to quiver

Beneath that steady drone,

And aching heads grow wearier,

With that ceaseless monotone;

"Zum, zum, zum, I'm a real Greengrocer!

Hark to my double drum;

I can make it go for an hour or so,

With a zum, zum, zum, zum."

When the still, hot day is over,

And the west wind drops at length,

The loud cicada chorus Wakens to double strength:

"Zum, zum, zum, I'm a Yellow Monday!

Hark to my double drum;

I can make it drone in its monotone,

With a zum, zum, zum, zum, zum.'

As the slow, slow hours are dragging

Through the hush of a still, hot night;

The full bush band keeps playing,

Right up to the morning light.

"Zum, zum, zum, I'm a Black Prince gorgeous!

Hark to my double drum;

All the long night through I shall play to you,

With a zum, zum, zum, zum, zum."

From the first grey light of the morning,

Till the sun sinks down in the west,

And all through the long night-watches,

The droning knows no rest:

"Zum, zum, zum, I'm a Floury Baker;

Zum, zum, zum, I'm a fat Greengrocer;

Zum, zum, zum, I'm a Yellow Monday;

Zum, zum, zum,

I'm a Black Prince gorgeous.

And each has a double drum.

So with ceaseless tone we just drone, drone, drone,

With a zum, zum, zum, zum, zum."

The Children's Page. (1926, November 18). The Catholic Press(NSW : 1895 - 1942), p. 46. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106276154

Bird Bath Visitors

Do you have a bird bath in your yard? We do - they're great for seeing all the birds come to have a drink or have a bath. We also hear frogs at night as there is a little pond we sat the bird bath in - lovely watery sounds of feathers and splish- splashing - we have to give it a clean at the end of every day and fill it back up with fresh cool water.

This is what we've seen in our bird bath the past few weeks and months:

Dementia Care In Australia "Does Not Meet Human Rights"

- have an overarching objective to maintain positive health and wellbeing of people with dementia, their care partners and families;

- recognise dementia as a disability, consistent with the World Health Organization Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and promotes autonomy, social participation and rehabilitation;

- take into account the cognitive disability of people with dementia in accessing support and being a partner (along with their families) in planning care through supported decision making;

- be delivered by a multidisciplinary workforce with knowledge and skills around dementia;

- be accessible for all people with dementia and care partners;

- be ongoing, cost-effective and economically sustainable;

- be needs-based, not capped according to central budgets;

- be integrated for seamless experience for people with dementia and care partners, within and across primary, acute and subacute health care, aged care and social services; and

- be evidence-based.

2021 Australian Masters Games Entries Now Open

Retirement Income Review Under The Spotlight

- A keynote address by Treasurer John Frydenberg

- A lunchtime debate between Minister for Superannuation Jane Hume and Shadow Minister Stephen Jones

- Be the first appearance of the entire Retirement Income Review panel since its findings were released, with Chair Mike Callaghan AM and members Carolyn Kay and Dr Deborah Ralston

- Other expert speakers include Professor John Piggott AO, Director, Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research; Professor Hazel Bateman, UNSW; David Knox from the Mercer Retirement Index; and Jeremy Cooper, Challenger and former Chair of the Superannuation Review

Elizabeth Farm - The Old And The New

Surfing In The Sixties - Mona Boys

Construction Apprentice Began Her Studies During HSC

February 10, 2021

A Chester Hill local is gearing up to work on major infrastructure projects across Sydney after landing an apprenticeship with international construction company Multiplex straight after graduating from high school.

Kaitlyn Doan, 18, used her final years of high school to launch her career in the construction industry by studying a Certificate II in Construction Pathways at TAFE NSW Miller while she completed the HSC at Prairiewood High School.

She will now begin working on the $1 billion Westmead Redevelopment precinct, which is set to be the state’s largest hospital redevelopment project in history.

Kaitlyn said she was excited to help cement western Sydney’s future by working on some of the region’s biggest infrastructure projects.

“My TAFE NSW teachers were able to connect me to people at Multiplex when they delivered a talk in one of our classes. I was thrilled to find out I had been offered an apprenticeship with them all thanks to the support of my teachers,” Kaitlyn said.

“The course helped me build practical skills and industry-specific knowledge so now I am able to take a year off my apprenticeship,” Kaitlyn said.

With carpentry currently facing a major skills shortage and wage subsidy funding by the federal government designed to help more apprentices into jobs, there has never been a better time to enrol in a construction course at TAFE NSW.

Multiplex Construction Manager Troy Rakecki said the Multiplex program is geared towards forging a career pathway for apprentices.

“Our apprentices are trained as future site supervisors so as well as being supported to develop in their chosen trade, they are given exposure to a variety of other trades and come away with a really well-rounded understanding of the different components that make up a construction site.”

TAFE NSW Carpentry teacher, Rodney Watts, said now was the time for school leavers to consider taking on a trade apprenticeship.

“TAFE NSW has over 25,000 employer connections, which allows our students to not only connect with industry but be well-positioned for job opportunities as soon as they graduate,” Mr Watts said.

“Western Sydney is currently facing a construction boom with various housing developments, the airport and hospital redevelopments well underway. It’s the perfect time to secure an apprenticeship.”

To enrol in a construction course at TAFE NSW, visit www.tafensw.edu.au, or call 131 601.

Picture: Kaitlyn Doan completed a Certificate II in Construction Pathways at TAFE NSW Miller

Online Courses Added To Summer Skills Program

The Summer Skills program has been expanded to include seven TAFE NSW online short courses targeting school leavers from last year.

An expansion of fee-free Summer Skills training courses is now available for school leavers with new online courses on offer, as part of the JobTrainer initiative.

Minister for Skills and Tertiary Education Geoff Lee said the Summer Skills program, launched in November 2020, has expanded to include seven TAFE NSW online short courses targeting school leavers from last year.

“In designing the Summer Skills program, the NSW Government has ensured the training on offer is aligned to local industry needs,” he said.

“We need to provide the opportunities that help school leavers find their feet in these uncertain times. That’s why we’re delivering practical and fee-free training opportunities commencing this summer. Online learning is a terrific way to upskill at your own pace,”

Mr Lee said all the courses come from the $320 million committed to delivering 100,000 fee-free training places as part of the NSW Government’s contribution to the JobTrainer initiative.

“There are more than 100,000 fee-free training places available through TAFE NSW and approved providers for people across NSW to reskill, retrain and redeploy to growth areas in a post COVID-19 economy.

“I encourage anyone impacted by the pandemic to see what training options are available in 2021.”

Enrolments are open for Summer Skills training in:

- Cyber Concepts;

- Introduction to working in the health industry;

- Construction materials and Work Health and Safety;

- Mental health;

- Business administration skills;

- Introductory to business skills; and

- Digital security basics.

Visit the NSW Summer Skills webpage for full details on all available fee-free courses on offer and their eligibility as part of the NSW Summer Skills program, and visit the JobTrainer webpage for more information.

NSW JobTrainer provides fee-free* training courses for young people, job seekers and school leavers to gain skills in Australia's growing industries. Explore hundreds of qualifications and register your interest today.

T.Rex: 20th Century Boy

"20th Century Boy" is a song by T. Rex, written by Marc Bolan, released as a stand-alone single. The song was recorded on 3 December 1972 in Toshiba Recording Studios in Tokyo, Japan at a session that ran between 3:00 p.m. and 1:30 a.m., according to biographers. The backing vocals, hand claps, acoustic guitar and saxophones were recorded in England when T. Rex returned to the country after their tour. The single version of the track fades out at three minutes and thirty-nine seconds; however, the multi-track master reveals that the song ended in nearly a full three minutes' worth of jamming. A rough mix of the full-length version can be found on the Bump 'n' Grind compilation.

"20th Century Boy"'s lyrics are, according to Marc Bolan, based on quotes taken from notable celebrities such as Muhammad Ali. This can be seen through the inclusion of the line "sting like a bee", which is taken from one of Ali's 1969 speeches.

Although the lyrical content of a lot of Marc Bolan's songs is ambiguous, analysis of the multi-track recordings of "20th Century Boy" reveals the first line of the song to be "Friends say it's fine, friends say it's good/Everybody says it's just like Robin Hood," and not the often misquoted "...just like rock 'n' roll."

Marc Bolan, songwriter, musician, record producer, and poet, was the lead singer of the band T. Rex and was one of the pioneers of the glam rock movement of the 1970s. He first played guitar in sc hool as part of "Susie and the Hula Hoops", a trio whose vocalist was a 12-year-old Helen Shapiro. During lunch breaks at school, he would play his guitar in the playground to a small audience of friends.

The familiar riff the song opens with you may have heard in the 2010 film Get Him to the Greek, as well as the films, Rocksmith, Guitar Hero 5 and Rock Band 3 and in the movies Lords of Dogtown, The Truman Show, Velvet Goldmine, Somewhere, and Drift. His music still sells and this song, along with 'Children of the Revolution' remains a favourite for many.

This is T.Rex / Marc Bolan performing 20th Century Boy live in Germany. NB: it's LOUD!

For those who prefer produced non-live sounds, a remastered versions run below this.

States housed 40,000 people for the COVID emergency. Now rough sleeper numbers are back on the up

Hal Pawson, UNSW and Chris Martin, UNSWAustralian governments acted to protect homeless people from COVID-19 in 2020 on an even larger scale than previously thought. In the first six months of the pandemic, the four states that launched emergency programs housed more than 40,000 rough sleepers and others.

The states were anxious about rough sleepers’ extreme vulnerability to virus infection and the resulting public health risk to the wider community. New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia acted fast to provide safe temporary housing, mainly in otherwise empty hotels.

Read more: The need to house everyone has never been clearer. Here's a 2-step strategy to get it done

Drawing on previously unreleased official statistics, our newly published international comparative research reveals the people these programs helped in Australia outnumbered the 33,000 rough sleepers and others housed in England by the equivalent Everyone In initiative. Australia’s population is less than half that of England.

What Happens When Emergency Housing Ends?

The numbers Australia’s emergency housing program needed to shelter showed our homelessness problem is much larger than often imagined. The 8,200 people counted as sleeping rough on census night 2016 were only the tip of the iceberg.

Attempts to transfer people from emergency accommodation to longer-term tenancies have also generally been far less successful than in England. By the end of 2020, England’s local authorities had moved two-thirds of their former rough sleepers from temporary placements to more stable housing. As our research shows, despite determined efforts, Australian state governments managed this for less than a third of rough sleepers departing emergency hotel stays in 2020.

Many will have returned to the streets or to homeless shelters. Rough sleeper numbers once again increased in Adelaide and Sydney after mid-year.

To a great extent Australia’s poor showing reflects our growing social housing deficit, as well as inadequate rent assistance and other social security benefits (at their standard rates). All of these factors are barriers to helping low-income Australians into stable long-term housing.

Read more: Coronavirus lays bare 5 big housing system flaws to be fixed

Eviction Bans And Rent Variations Defer Problems

Alongside protecting rough sleepers, Australian government actions to shield vulnerable renters who lost jobs and incomes in the pandemic were also relatively effective. These efforts include federal income protection (JobKeeper and Coronavirus Supplement) and state and territory restrictions on evictions.

The short-term success of these measures is clear. Despite a substantial rise in unemployment, there has been – as yet – no sign of any up-tick in homelessness.

At the same time, though, ministerial advice that tenants with COVID-triggered income losses should negotiate rent reductions with landlords came with few ground rules on how to reach such settlements.

Survey evidence shows many property owners refused to reduce rents. At least one in four renters lost income during the pandemic, but no more than 16% (and possibly as few as 8%) got a rent variation. And many variations were only in the form of rent deferrals, not reductions.

The survey data imply at least 75,000 tenants, and possibly as many as 175,000, have been accumulating deferral-generated arrears. These mounting debts could put some at risk of losing their home when eviction moratoriums end. That’s early in 2021 in most states and territories.

Read more: Cutting JobSeeker payments will cause crippling rental stress in our cities

Hands-Off Commonwealth Makes Things Worse

Our research also highlights the unusually small direct contribution of the Australian government to protecting homeless people during the pandemic. Even in other federations – Canada and the United States – national governments played a significant role.

In Australia, the Commonwealth government made no direct input to covering the substantial costs involved. Nor did it play any part in even monitoring, let alone co-ordinating, the remarkable efforts of the active states.

Canberra has also steadfastly rejected calls for a social housing stimulus program for national economic recovery. This disengagement fits with a now-familiar refrain from federal ministers. Housing and homelessness, they repeat time and again, are constitutional obligations of state and territory governments.

Read more: Why the focus of stimulus plans has to be construction that puts social housing first

Read more: Why more housing stimulus will be needed to sustain recovery

Granted, that’s an accurate statement for housing and homelessness service delivery. But, especially given the Commonwealth’s control of the vital policy levers of tax and social security, the two levels of government must in reality share responsibility for housing outcomes.

The Victorian government’s A$5.4 billion Big Housing Build shows states may commit to investment in social rental housing on a scale far beyond what had been thought possible. But the fact remains that state and territory governments have much less financial firepower than our national government. It’s fanciful to imagine significant programs being widely initiated or maintained without hefty federal backing.

Read more: Victoria's $5.4bn Big Housing Build: it is big, but the social housing challenge is even bigger

For all of these reasons, when the pandemic has finally subsided, it’s only with federal government leadership that we can effectively tackle the fundamental flaws in Australia’s housing system. These have been glaringly exposed by the public health crisis of the past 12 months. Without purposeful re-engagement by our national government, Australia’s housing policy challenges will only continue to intensify.

Read more: Australia's housing system needs a big shake-up: here's how we can crack this ![]()

Hal Pawson, Professor of Housing Research and Policy, and Associate Director, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW and Chris Martin, Senior Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

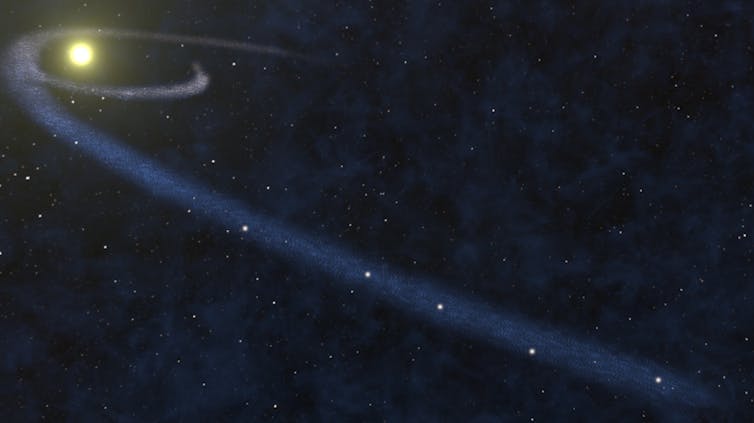

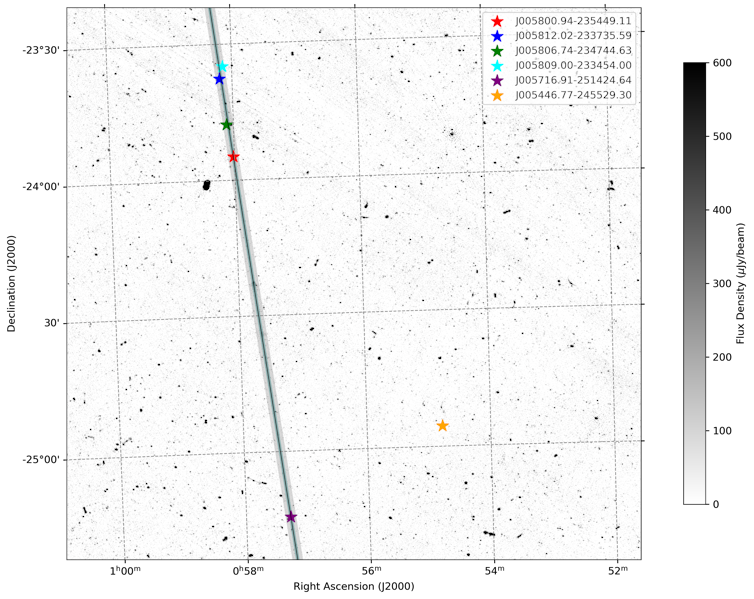

5 twinkling galaxies help us uncover the mystery of the Milky Way's missing matter

We’ve all looked up at night and admired the brightly shining stars. Beyond making a gorgeous spectacle, measuring that light helps us learn about matter in our galaxy, the Milky Way.

When astronomers add up all the ordinary matter detectable around us (such as in galaxies, stars and planets), they find only half the amount expected to exist, based on predictions. This normal matter is “baryonic”, which means it’s made up of baryon particles such as protons and neutrons.

But about half of this matter in our galaxy is too dark to be detected by even the most powerful telescopes. It takes the form of cold, dark clumps of gas. In this dark gas is the Milky Way’s “missing” baryonic matter.

In a paper published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, we detail the discovery of five twinkling far-away galaxies that point to the presence of an unusually shaped gas cloud in the Milky Way. We think this cloud may be linked to the missing matter.

Finding What We Can’t See