inbox and environment news: Issue 484

February 21 - 27, 2021: Issue 484

Time Of Burran

Gadalung Marool (hot and dry) January - March

The behaviour of the male kangaroos becomes quite aggressive in this season, and it is a sign that the eating of meat is forbidden during this time. This is a health factor; because of the heat of the day meat does not keep, and the likelihood of food poisoning is apparent. The blooming of the Weetjellan (Acacia implexa) is an important sign that fires must not be lit unless they are well away from bushland and on sand only, and that there will be violent storms and heavy rain, so camping near creeks and rivers is not recommended.

Acacia implexa, commonly known as lightwood or hickory wattle, is a fast-growing Australian tree, the timber of which was used for furniture making. The wood is prized for its finish and strength. The foliage was used to make pulp and dye cloth. The Ngunnawal people of the ACT used the bark to make rope, string, medicine and for fish poison, the timber for tools, and the seeds to make flour.

It is widespread in eastern Australia from central coastal Queensland to southern Victoria, with outlying populations on the Atherton Tableland in northern Queensland and Tasmania's King Island. The tree is commonly found on fertile plains and in hilly country it is usually part of open forest communities and grows in shallow drier sandy and clay soils.

Acacia implexa flowers - photo by Donald Hobern.

Bangalley Head Landcare Bushcare Neglect Resolved

Newport Beach Clean Up: Sunday February 28th, 2021

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Pittwater Nature #4 Is Now Available

- The Pittwater River and the Barrenjoey sandspit

- How Tumbledown Dick hill Duffys Forest endangered bushland has been moved there from a site at Belrose

- The Sydney Wildlife Mobile Unit looks after native animals

- Plant Families 101: the Solanaceae /Nightshade Family.

- Prey and Predators on Bilgola Plateau

- Two birds that nest in hollows.

- Cicadas emerge at night.

Upcoming Activities For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment:

Sun 21 February 2021: 7.30 am Walk & Weed along the Narrabeen Lagoon catchment transverse walk.

Start at Oxford Falls walk for 3 1/2 hours, weed for 30min, continue 30min walk and car pool back to start.

Bring gloves and long handled screwdriver if available.

Walk grade: medium.

Bookings essential. Conny 0432 643 295

https://www.narrabeenlagoon.org.au/

Friends of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment are pleased to announce the next forum will be held on 22 Feb 2021 at 7 pm .

Presenter: Jayden Walsh

Jayden is a keen observer of nature and has some stunning photographs and information to share.

The focus will be on wildlife that lives near the Narrabeen Lagoon and that, if you are fortunate, you may see when on the Narrabeen Lagoon walkway.

For details on how to book for this event are on the website. At: https://www.narrabeenlagoon.org.au/Forums/forums.htm

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Pittwater Reserves

Senate Inquiry Into Environment Protection And Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Regional Forest Agreements) Bill 2020

''This Bill will affirm and clarify the Commonwealth’s intent regarding Regional Forest Agreements to make it explicitly clear that forestry operations in a Regional Forest Agreement region are exempt from Part 3 of the EPBC Act, and that compliance matters are to be dealt with through the state regulatory framework.

Requiring native forestry operations to seek EPBC Act approval would create operationally unviable delays in planned harvesting operations that have already been subjected to significant environmental planning and approvals and create congestion in the approvals pipeline.

This is achieved by removing the ambiguity of what it means to be “undertaken in accordance with a Regional Forest Agreement” (subsection 38(1) of the EPBC Act), which a recent Federal Court decision (Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 4) [2020] FCA 704 has shown is not explicit with respect to the Commonwealth’s intended meaning.

Furthermore, the operation of subsection 38(1) is just one of several legal questions considered by Justice Mortimer’s judgment and subsequent appeal. There is no guarantee that the appeal will deal with the substantive question about the operation of subsection 38(1).

The Independent review of the EPBC Act Interim Report (Samuel 2020) recommended addressing this uncertainty:

- “During the course of this Review, the Federal Court found that an operator had breached the terms of an RFA and should therefore be subject to the ordinary controlling provisions of the EPBC Act. Legal ambiguities in the relationship between EPBC Act and the RFA Act should be clarified, so that the Commonwealth’s interests in protecting the environment interact with the RFA framework in a streamlined way.” (page 10), and

- “The EPBC Act recognises the RFA Act, and additional assessment and approvals are not required for forestry activities conducted in accordance with an RFA (except where forestry operations are in a World Heritage property or a Ramsar wetland). These settings are colloquially referred to as the 'RFA exemption', which is somewhat of a misnomer.” (page 60).

The Interim Report also made it clear that under a regional model of empowering the states, the oversight functions would be the responsibility of the states through accredited frameworks (as occurs with Regional Forest Agreements):

“For projects approved under accredited arrangements, the accredited regulator would be responsible for ensuring that projects comply with requirements, across the whole project cycle including transparent post-approval monitoring, compliance and enforcement. The Commonwealth should retain the ability to intervene in project-level compliance and enforcement where egregious breaches are not being effectively enforced by the accredited party.” (page 55).

''The Commonwealth must act urgently to resolve this uncertainty to ensure that the tens of thousands of jobs that depend on Australia’s native forestry operations are not exposed to the sort of crisis now facing Victoria’s native hardwood sector. This amendment Bill will achieve this outcome.''

- First reading: Text of the bill as introduced into the Parliament

- Third reading: Prepared if the bill is amended by the house in which it was introduced. This version of the bill is then considered by the second house.

- As passed by both houses: Final text of bill agreed to by both the House of Representatives and the Senate which is presented to the Governor-General for assent.

EPA Statement-Update On Forestry Regulation: FCNSW Set To Log Bushfire Devastated South Coast

Media Statement – Update On Vales Point Power Station

$16.5 Million For More Green Space

- $2 million to upgrade the Hungry Point walking track at Cronulla including construction of a coastal viewing platform;

- $1.5 million towards restoration of a former railway tunnel at Glenbrook in the Blue Mountains so it can be reactivated as a recreational trail;

- $1.5 million to help Penrith City Council restore a historic former police cottage at Emu Plains;

- $1.5 million to undertake essential maintenance work on the historic Meadowbank Bridge and its pedestrian path and cycleway;

- $1.5 million to remove dilapidated cottages from the Georges River foreshore at Illawong to restore the land to public open space;

- $1.135 million for maintenance and repair work at the former Prince Henry Hospital site at Little Bay including heritage-listed structures;

- $1 million to restore the heritage-listed South Head Signal Station at Vaucluse;

- $500,000 for improvement works at Bidjigal Reserve in Baulkham Hills including bushland restoration and upgrades to walking trails, signage and stormwater infrastructure;

- $250,000 to clean up and assess land at Northmead for contamination on the site of a mechanical workshop.

Contamination Assessment For Empire Bay Marina

NRAR Responds To Incident In Lake Albert

World First Gene Program To Help Koalas

Don't disturb the cockatoos on your lawn, they're probably doing all your weeding for free

Australians have a love-hate relationship with sulphur-crested cockatoos, Cacatua galerita. For some, the noisy parrots are pests that destroy crops or the garden, damage homes and pull up turf at sports ovals.

For others, they’re a bunch of larrikins who love to play and are quintessentially Australian.

Along with other scientists, I had a unique opportunity during the COVID-19 lockdowns to study things that had intrigued me closer to home, perhaps for years. While isolating in the suburbs of Melbourne, I wanted to find out why cockatoos return to the same places, and what they’re after.

The answer? Onion grass, reams of it.

Onion grass is a significant weed, and I estimated in a recent paper that one bird gorges on about 200 plants per hour. A flock of about 50 birds can consume 20,000 plants in a couple of hours.

This significantly reduces the weed level and may make expensive herbicide use unnecessary. So if you have a large amount of onion grass on your property and are regularly visited by sulphur-crested cockatoos, it would be wise to let them do their weeding first.

When Play Verges On Vandalism

Most of us see cockies whether we live in rural communities or major cities, but how much do you really know about them?

In late winter and early spring in many parts of Australia, flocks of sulphur–crested cockatoos can be seen grazing on the ground. They’re usually found close to water, nesting in woodlands with old hollow trees, such as river red gums, Eucalyptus camaldulensis.

Where these forests and trees are being cleared, the number of cockies falls. But they are resilient and adaptable birds, and have spread their range to cities and the urban fringe, where numbers are increasing.

Read more: Birds that play with others have the biggest brains - and the same may go for humans

The birds are known to play with fruits, hang upside down on branches or perform flying cartwheels by holding a small branch or powerline with their feet, flapping their wings as they do loop after loop.

Sometimes their play verges on vandalism as they follow tree planters, deftly pulling up just-planted trees and laying them neatly beside the hole.

While cockatoos feed on the fruits and seed of native species, they’ve adapted very quickly to the introduction of exotic species, such as onion grass from South Africa, which is plentiful and easy to harvest.

I observed flocks ranging from nine to 63 cockatoos at seven sites along the Maribyrnong River in Keilor last July and August. Onion grass was the only item on their menu.

A Pest For Humans, A Feast For Birds

Onion grass (Romulea rosea) is small and usually inconspicuous with grass-like leaves. It’s typically only noticed when it flowers in spring, producing pretty, pink and yellow-throated flowers.

Onion grass can be a serious weed that’s very difficult to control. It’s not only a problem for agricultural land, but also for recreational turf and native grasslands.

In some areas, there are nearly 5,000 onion grass plants per square metre. This is a massive number requiring costly control measures, such as spraying or scraping away the upper layer of top soil.

Read more: The river red gum is an icon of the driest continent

Onion grass gets its name from its onion-like leaves. At the base is a small bulb, which works as a modified underground stem called a “corm”. The corm is what cockatoos will travel many kilometres for, to dig up and return to for days on end.

Their Super Weeding Effort

Like other native parrots, sulphur-crested cockatoos are famously left-footed. So it was interesting to observe them primarily use their powerful beaks to pull onion grass plants from the ground and dig up corms, using their left foot only occasionally to manipulate the plant.

The cockatoos fed for between 30 minutes and two and a half hours. At each feed, one or two sentry (or sentinel) birds, depending on the flock size, would keep watch and give raucous warning should danger threaten.

The cockies could remove a plant and corm from the ground in as little as six seconds, but sometimes it could take up to 30 seconds. They then removed and consumed a corm every 14 seconds on average in wet soil and every 18 seconds from harder, dry soil.

This means a flock of 63 birds could remove more than 35,400 onion grass plants in a feeding session lasting two and half hours. This is a super weeding effort by any standard!

Future Partnerships

My further investigation revealed most of the corms were within 20 millimetres of the soil surface, so the holes left in the soil by the birds extracting the onion grass were shallow and quite small. This shouldn’t give seeds from onion grass any great advantage.

And they’re very efficient: the birds eat over 87% of the corms they lift, which then won’t get a chance to generate in future years. So, if we’re going to try to eradicate onion grass, it may be better to let the cockies do their work first before we humans take a turn.

We have a lot to learn about how our native species interact with introduced weeds, and more research might reveal some very useful future partnerships. They might be birdbrains, but sulphur-crested cockatoos really know their onions when it comes to, well, onion grass.

Read more: Running out of things to do in isolation? Get back in the garden with these ideas from 4 experts ![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Water injustice runs deep in Australia. Fixing it means handing control to First Nations

It’s widely understood that rivers, wetlands and other waterways hold particular significance for First Nations people. It’s less well understood that Indigenous peoples are denied effective rights in Australia’s water economy.

Australia’s laws and policies prevent First Nations from fully participating in, and benefiting from, decisions about water. In fact, Indigenous peoples hold less than 1% of Australia’s water rights.

A Productivity Commission report into national water policy released last week acknowledged the demands of First Nations, noting “Traditional Owners aspire to much greater access to, and control over, water resources”.

The commission suggested a suite of policy reforms. While the recommendations go further than previous official reports, they show a lack of ambition and would ensure water justice continues to be denied to First Nations.

No Voice, No Justice

First Nations people have almost no say in how water is used in Australia. This denies them the power to prevent water extraction that will damage communities and landscapes, and in many cases means they’re unable to fulfil their responsibilities to care for Country.

It also means First Nations are excluded from much of Australia’s agricultural wealth, which is tied to access to water for irrigation.

In the New South Wales portion of the Murray-Darling Basin, for example, our research found Indigenous peoples are almost 10% of the population yet comprise only 3.5% of the agricultural workforce. First Nations also own just 0.5% of agricultural businesses and receive less than 0.1% of agricultural revenue.

Read more: Aboriginal voices are missing from the Murray-Darling Basin crisis

Piecemeal Water Reform

The National Water Initiative – a blueprint for water reform signed by all Australian governments in 2004 – committed to consulting with Traditional Owners in water planning, accounting for native title rights to water and including cultural values in water plans.

The Productivity Commission report said progress towards these commitments “has been slow and objectives have not been fully achieved”.

The report contains several welcome recommendations, including that:

a new water policy be devised, with a dedicated objective and targets to improve First Nations access to water and involvement in water management

the recently formed Committee on Aboriginal Water Interests “co-design” new provisions relating to First Nations’ water interests, and have direct dialogue with water ministers

a First Nations-led model of water reform be adopted, centred on the concept of “cultural flows”. This concept calls for substantial increases to First Nations’ water access and more control in decision-making.

Cause Of Injustice Ignored

Sadly, the Productivity Commission does not address the structural problems underlying inequities in Indigenous water rights.

In particular, it wrongly assumes policy success should be measured in terms of efficiency and the integrity of water markets, rather than justice for First Nations.

Water sold on markets goes to the highest bidder. This rewards large agricultural enterprises and others who historically held land and water rights, gained through the dispossession of First Nations people. And it penalises First Nations peoples who are unlikely to own productive farming land, or who don’t always wish to use water for irrigated agriculture.

In some cases, poorly funded Indigenous organisations have traded away their water rights to keep afloat, and will find it near-impossible to buy the water back. Our research shows this pattern drove a 17% decline in Indigenous water holdings in the Murray-Darling Basin over the past decade.

Read more: Australia has an ugly legacy of denying water rights to Aboriginal people. Not much has changed

The commission’s recommendations rely heavily on policy architecture and legal foundations that fail First Nations.

For example, in 1998 the Howard Government legislated to exclude water infrastructure and entitlements from parts of the Native Title Act. This means that infrastructure and licensing can proceed without negotiation with native title holders.

The Productivity Commission overlooked ways to correct this injustice – such as the Law Reform Commission’s proposal to change the law so native title holders can benefit from commercial use of water.

The commission’s response to conflict over developments such as dams is also inadequate. Rather than transfer final decision-making power to First Nations groups, it proposes that developments be more “culturally responsive”.

This will not protect cultural heritage. Case in point is the NSW government’s plan to raise the Warragamba Dam wall, creating a flood that threatens more than 1200 Indigenous cultural sites. Statutory protections are needed to head off such proposals.

Stronger Models For Reform

The United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is clear: Indigenous peoples should have the power to decide on development proposed on their lands and waters.

An agreement between the Ngarrindjeri nation and the South Australian government in the lower Murray River region shows how even modest rights can both empower Traditional Owners and lead to successful environmental management.

The agreement enables a co-management approach where authority in developing natural resource management policy is shared. Unfortunately, reforms of this type are beyond the ambition of the Productivity Commission report.

Addressing water injustice also requires returning water to First Nations, such as by buying back water entitlements and guaranteeing cultural flows in water plans. The Productivity Commission outlines how this might occur, but falls short of recommending this vital measure.

The current policy framework has allowed some advances. But if water justice to Indigenous peoples is to be realised, changes to policy and laws must go far deeper.

Sue Jackson, Professor, Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University; Francis Markham, Research Fellow, College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University; Fred Hooper, Indigenous knowledge holder, Indigenous Knowledge; Grant Rigney, Indigenous knowledge holder, Indigenous Knowledge; Lana D. Hartwig, Research Fellow, Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University, and Rene Woods, Indigenous Knowledge Holder, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Blind shrimps, translucent snails: the 11 mysterious new species we found in potential fracking sites

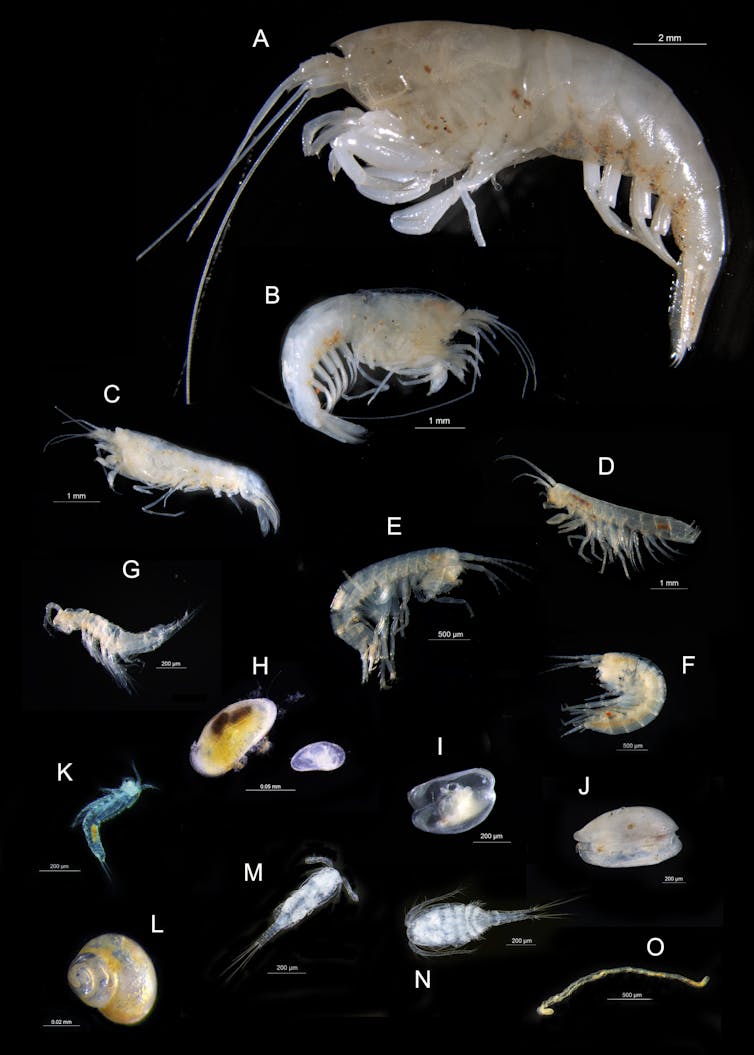

There aren’t many parts of the world where you can discover a completely new assemblage of living creatures. But after sampling underground water in a remote, arid region of northern Australia, we discovered at least 11, and probably more, new species of stygofauna.

Stygofauna are invertebrates that have evolved exclusively in underground water. A life in complete darkness means these animals are often blind, beautifully translucent and often extremely localised – rarely living anywhere else but the patch they’re found in.

The species we discovered live in a region earmarked for fracking by the Northern Territory and federal government. As with any mining activity, it’s important future gas extraction doesn’t harm groundwater habitats or the water that sustains them.

Our findings, published today, show the importance of conducting comprehensive environmental assessments before extraction projects begin. These assessments are especially critical in Australia’s north, where many plants and animals living in surface and groundwater have not yet been documented.

When The Going Gets Tough, Go Underground

Stygofauna were first discovered in Western Australia in 1991. Since then, these underground, aquatic organisms have been recorded across the continent. Today, more than 400 Australian species have been formally recognised by scientists.

Stygofauna are the ultimate climate change refugees. They would have inhabited surface water when inland Australia was much wetter. But as the continent started drying around 14 million years ago, they moved underground to the relatively stable environmental conditions of subterranean aquifers.

Read more: Hidden depths: why groundwater is our most important water source

Today, stygofauna help maintain the integrity of groundwater food webs. They mostly graze on fungal and microbial films created by organic material leaching from the surface.

In 2018, the final report of an independent inquiry called for a critical knowledge gap regarding groundwater to be filled, to ensure fracking could be done safely in the Northern Territory. We wanted to determine where stygofauna and microbial assemblages occurred, and in what numbers.

Our project started in 2019, when we carried out a pilot survey of groundwater wells (bores) in the Beetaloo Sub-basin and Roper River region. The Beetaloo Sub-basin is potentially one of the most important areas for shale gas in Australia.

What We Found

The stygofauna we found range in size from centimetres to millimetres and include:

two new species of ostracod: small crustaceans enclosed within mussel-like shells

a new species of amphipod: this crustacean acts as a natural vacuum cleaner, feeding on decomposing material

multiple new species of copepods: tiny crustaceans which form a major component of the zooplankton in marine and freshwater systems

a new syncarid: another crustacean entirely restricted to groundwater habitats

a new snail and a new worm.

These species were living in groundwater 400 to 900 kilometres south of Darwin. We found them mostly in limestone karst habitats, which contain many channels and underground caverns.

Perhaps most exciting, we also found a relatively large, colourless, blind shrimp (Parisia unguis) previously known only from the Cutta Cutta caves near Katherine. This shrimp is an “apex” predator, feeding on other stygofauna — a rare find for these kinds of ecosystems.

Protecting Groundwater And The Animals That Live There

The Beetaloo Sub-basin in located beneath a major freshwater resource, the Cambrian Limestone Aquifer. It supplies water for domestic use, cattle stations and horticulture.

Surface water in this dry region is scarce, and it’s important natural gas development does not harm groundwater.

The stygofauna we found are not the first to potentially be affected by a resource project. Stygofauna have also been found at the Yeelirrie uranium mine in Western Australia, approved by the federal government in 2019. More research will be required to understand risks to the stygofauna we found at the NT site.

Read more: It's not worth wiping out a species for the Yeelirrie uranium mine

The discovery of these new NT species has implications for all extractive industries affecting groundwater. It shows the importance of thorough assessment and monitoring before work begins, to ensure damage to groundwater and associated ecosystems is detected and mitigated.

Where To From Here

Groundwater is vital to inland Australia. Underground ecosystems must be protected – and not considered “out of sight, out of mind”.

Our study provides the direction to reduce risks to stygofauna, ensuring their ecosystems and groundwater quality is maintained.

Comprehensive environmental surveys are needed to properly document the distribution of these underground assemblages. The new stygofauna we found must also be formally recognised as a new species in science, and their DNA sequence established to support monitoring programs.

Many new tools and approaches are available to support environmental assessment, monitoring and management of resource extraction projects. These include remote sensing and molecular analyses.

Deploying the necessary tools and methods will help ensure development in northern Australia is sustainable. It will also inform efforts to protect groundwater habitats and stygofauna across the continent.

Jenny Davis, Professor, Research Institute for Environment & Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Charles Darwin University; Daryl Nielsen, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO; Gavin Rees, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO, and Stefanie Oberprieler, Research associate, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No point complaining about it, Australia will face carbon levies unless it changes course

John Quiggin, The University of QueenslandReports that Britain’s prime minister Boris Johnson is considering calling for carbon border levies at the G7 summit to be held in London in June have produced a predictable reaction from the Australian government.

The levies would impose tariffs on carbon-intensive goods from countries such as Australia that haven’t adopted a carbon price or a 2050 net-zero emissions target.

Appearing to be shocked by the news, Energy Minister Angus Taylor declared that Australia is “dead against” carbon tariffs.

They were a “new form of protectionism designed to shield local industries from free trade”.

In fact they are already the policy of the European Union and the US, where President Joe Biden calls them a “carbon adjustment fee against countries that are failing to meet their climate and environmental obligations”. Canada, which has an economy-wide price on carbon, isn’t worried.

Saying you’re dead against something doesn’t stop it, and nor does asserting that it is anti free trade, when it is just as arguable that it is pro fair trade because it denies exporters from countries that aren’t taking action against climate change an unfair advantage.

Australia Not The Primary Target

The mining industry itself made this point during the Gillard government’s introduction of Australia’s short-lived carbon price.

It would leave Australian exporters at a “disadvantage compared with international competitors”.

Australia isn’t the primary target in any event. The main aim of carbon tariffs would be to encourage China’s leader Xi Jinping to shift his country’s zero emissions date from 2060 to 2050, benefiting the rest of the world.

Read more: Vital Signs: a global carbon price could soon be a reality – Australia should prepare

If Xi Jinping does it, he’ll be on a level playing field with much of the world, although not with Australia, whose fate, like that of Britain’s Admiral Byng in 1757 would be used “to encourage the others”.

Complaining won’t much help. The International Monetary Fund has endorsed the idea, saying

in the absence of an agreement on carbon pricing – which would be by far preferable – applying the same carbon prices on the same products irrespective of where they are produced could help avoid shifting emissions out of the EU to countries with different standards

The World Trade Organisation, which has in the past has pushed back against environmental considerations in trade, is neutered.

World Trade Organisation Powerless

In the late 1990s the WTO struck down a range of environmental restrictions imposed by the United States that required imported tuna to be labelled “dolphin safe” and required shrimp catchers to take action to protect turtles.

These decisions proved disastrous for the WTO, producing bitter hostility from the environmental movement and contributing to mass protests at the 1999 WTO meeting, which became known as the Battle of Seattle and ultimately killed the Doha round of trade negotiations.

Right now the WTO is in the organisational equivalent of an induced coma. By refusing to fill vacancies as they arose, the Trump Administration denied its appellate panel a quorum, forcing it to stop hearing cases.

The result is that any appeal to the WTO against carbon border tariffs would be left in limbo. US President Joe Biden has agreed to the appointment of a new WTO director general, stalled by Trump, but is in no hurry to re-establish the appellate body.

Instead, he will first try to refashion the WTO into an organisation that supports his own policies, among them stronger environmental measures, carbon tariffs and “Buy American” provisions. When reformed, the appellate body will give complaints from Australia’s government short shrift.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has shown some signs of recognising these realities, making baby steps towards announcing a 2050 zero emissions target.

But time is short. Morrison will have to either face down the denialists and do-nothingists on his own side of politics, or set himself, and Australia, up for a series of humiliations on the international stage, with real and damaging consequences.![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Plastic in the ocean kills more threatened albatrosses than we thought

Plastic in the ocean can be deadly for marine wildlife and seabirds around the globe, but our latest study shows single-use plastics are a bigger threat to endangered albatrosses in the southern hemisphere than we previously thought.

You may have heard of the Great Pacific garbage patch in the northern Pacific, but plastic pollution in the southern hemisphere’s oceans has increased by orders of magnitude in recent years.

We examined the causes of death of 107 albatrosses received by wildlife hospitals and pathology services in Australia and New Zealand and found ocean plastic is an underestimated threat.

Plastic drink bottles, disposable utensils and balloons are among the most deadly items.

Albatrosses are some the world’s most imperiled seabirds, with 73% of species threatened with extinction. Most species live in the southern hemisphere.

We estimate plastic ingestion causes up to 17.5% of near-shore albatross deaths in the southern hemisphere and should be considered a substantial threat to albatross populations.

Read more: These are the plastic items that most kill whales, dolphins, turtles and seabirds

Magnificent Ocean Wanderers

Albatrosses spend their entire lives at sea and can live for more than 70 years. They return to land only to reunite with their mate and raise a single chick during the warmer months.

Although the world’s largest flying birds are rarely seen from land, human activities are driving nearly three quarters of albatross species to extinction.

Each year, thousands of albatrosses are caught as unintended bycatch and killed by fishing boats. Introduced rats and mice eat their chicks alive on remote islands and the ocean where they spend their lives is becoming increasingly warmer and filled with plastic.

Young Laysan albatrosses with their bellies full of plastic are not just a tragic tale from the remote northern Pacific. Albatrosses are dying from plastic in the southern oceans, too.

When a Royal albatross recently died in care at Wildbase Hospital after eating a plastic bottle, it was not an isolated incident.

Single-Use Plastics Hit Albatrosses Close To Home

Eighteen of the world’s 22 albatross species live in the southern hemisphere, where plastic is currently considered a lesser threat. But the amount of discarded plastic is increasing every year, mostly leaked from towns and cities and accumulating near the shore.

Single-use items make up most of the trash found on coastlines around the world. Seven of the ten most common items — drink bottles, food wrappers and grocery bags — are made of plastic.

When albatrosses are found struggling near the shore in New Zealand, they are delivered to wildlife hospitals such as Wildbase Hospital and The Nest Te Kōhanga. A recent spate of plastic-linked deaths spurred us to dig a little deeper into the risk of plastic pollution to these magnificent ocean wanderers.

A Thousand Cuts: Plastic And Other Threats

Of the 107 albatrosses of 12 species we examined, plastic was the cause of death in half of the birds that had ingested it. In the cases we examined, plastic deaths were more common than fisheries-related deaths or oiling.

We compared these cases with data on plastic ingestion and fishery interaction rates from other studies. Based on our findings, we used statistical methods to estimate how many albatrosses were likely to eat plastic and might die from ingesting it, and how these figures compared to other major threats such as fisheries bycatch.

We found that in the near-shore areas of Australia and New Zealand, the ingestion of plastic is likely to cause about 3.4% of albatross deaths. In more polluted near-shore areas, such as those off Brazil, we estimate plastic ingestion causes 17.5% of all albatross deaths.

Read more: Plastic poses biggest threat to seabirds in New Zealand waters, where more breed than elsewhere

Because albatrosses are highly migratory, even those birds that live in less polluted areas are at risk as they wander the global ocean, travelling to polluted waters. Our results suggest the ingestion of plastic is at least of equivalent concern as long-line fishing in near-shore areas.

For threatened and declining albatross species, these rates of additional mortality are a serious concern and could result in further population losses.

Deadly Junk Food For Marine Life

Not all types of plastic are equally deadly when eaten. Albatrosses can regurgitate many of the indigestible items they eat.

Soft plastic and rubber items (such as latex balloons), in particular, can be deadly for marine animals because they often become trapped in the gut and cause fatal blockages, leading to a long, slow death by starvation. Plastic is difficult to see with common scanning techniques, and gut blockages often remain undetected.

Albatrosses like to eat squid, and inexperienced young birds are especially prone to mistaking balloons and other plastic for food, with potentially lethal consequences.

We recommend that wildlife hospitals, carers and biologists consider gastric obstruction when sick albatrosses are presented. Our publication includes a checklist to help in the detection of gastric blockages.

Global cooperation to reduce leakage of plastic items into the ocean — such as the Basel Convention and the recommendations by the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy — are first steps towards preventing unnecessary deaths of marine animals.

Read more: We need a legally binding treaty to make plastic pollution history

Stronger adherence to multilateral agreements, such as the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels which aims to reduce the impact of activities known to kill albatrosses, would help prevent the decline of breeding populations to unsustainably low levels.

If populations fall to critically endangered levels, intensive remediation including the expansion of chick and nest protection programmes, invasive species eradication and seabird translocations, may be required to prevent species extinction.

We would like to acknowledge our New Zealand and Australian colleagues who contributed to this research project. Veterinarians Baukje Lenting and Phil Kowalski care for injured seabirds and other wildlife at The Nest Te Kōhanga at Wellington Zoo. Veterinarian Megan Jolly cares for injured wildlife at Wildbase Hospital and vet pathologist Stuart Hunter provides a nationwide wildlife pathology service at Wildbase pathology at Massey University. David Stewart conducts threatened species research and monitoring at the Queensland state government’s Department of Environment and Science.

Richelle Butcher, Veterinary Resident at Wildbase, Massey University; Britta Denise Hardesty, Principal Research Scientist, Oceans and Atmosphere Flagship, CSIRO, and Lauren Roman, Postdoctoral Researcher, Oceans and Atmosphere, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

'Everyone else does it, so I can too': how the false consensus effect drives environmental damage

There’s a useful concept from psychology that helps explain why good people do things that harm the environment: the false consensus effect. That’s where we overestimate how acceptable and prevalent our own behaviour is in society.

Put simply, if you’re doing something (even if you secretly know you probably shouldn’t), you’re more likely to think plenty of other people do it too. What’s more, you likely overestimate how much other people think that behaviour is broadly OK.

This bias allows people to justify socially unacceptable or illegal behaviours.

Researchers have observed the false consensus effect in drug use, how well nurses follow certain procedures at work, and illegal hunting in Africa.

More recently, conservationists and environmental researchers are beginning to reveal how the false consensus effect contributes to environmental damage.

Read more: The majority of people who see poaching in marine parks say nothing

From Illegal Fishing To Climate Change

In previous research, my colleagues and I showed how the false consensus effect supports ongoing poaching (meaning fishing in no-take zones) by recreational fishers on the Great Barrier Reef.

In particular, we found people who admitted to poaching thought it was much more prevalent in society than it really was, and had higher estimates than fishers who complied with the law.

The poachers also believed others viewed poaching as socially acceptable; however, in reality, more than 90% of fishers viewed poaching as both socially and personally unacceptable.

Beyond poaching, the false consensus effect can help explain other behaviours.

One study examined students living on campus who were told not to shower while an emergency water ban was in place. It found those who showered in breach of the rules vastly overestimated how many other students were doing the same thing.

In a different study, researchers surveyed Australians about climate change and asked them what opinions they thought most other people held about the topic. The researchers found:

…opinions about climate change are subject to strong false consensus effects, that people grossly overestimate the numbers of people who reject the existence of climate change in the broader community.

The false consensus effect has also shown up in studies examining support for nuclear energy and offshore wind farms.

Using Psychology To Understand And Address Environmental Damage

As a growing body of research has shown, humans are shockingly bad at making accurate social judgements about the actual attitudes of others.

This gets even more problematic when we unwittingly project our own internal attitudes and beliefs onto others in an attempt to seek confirmation and reassurance.

Just as concepts from psychology can help explain some forms of environmental damage, so too can psychological concepts help address it. For example, research shows people are more likely to litter in areas where there’s already a lot of trash strewn around; so making sure the ground around a bin is not covered in rubbish may help.

But interventions that work in one culture to encourage environmentally friendly behaviour may not work in a different culture.

In Germany, for example, a campaign aimed at increasing consumption of sustainable seafood actually led to a decline in sustainable choices compared to baseline levels, likely because the messages were seen as manipulative and ended up driving shoppers away from choosing sustainable options.

Campaigns to reduce consumption of shark fin soup, buying pangolin meat or scales, and single-use plastic water bottles aim to counter the idea that these environmentally damaging behaviours are widespread and socially acceptable.

Factual information on how other people think and behave can be very powerful. Energy companies have substantially reduced energy consumption simply by showing people how their electricity use compares to their neighbors and conscientious consumers.

Encouragingly, activating people’s inherent desire for status has also been successful in getting people to “go green to be seen”, or to publicly buy eco-friendly products.

As the research evidence shows, social norms can be a powerful force in encouraging and popularising environmentally friendly behaviours. Perhaps you can do your bit by sharing this article!

Read more: How to deal with the Craig Kelly in your life: a guide to tackling coronavirus contrarians ![]()

Brock Bergseth, Postdoctoral research fellow, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

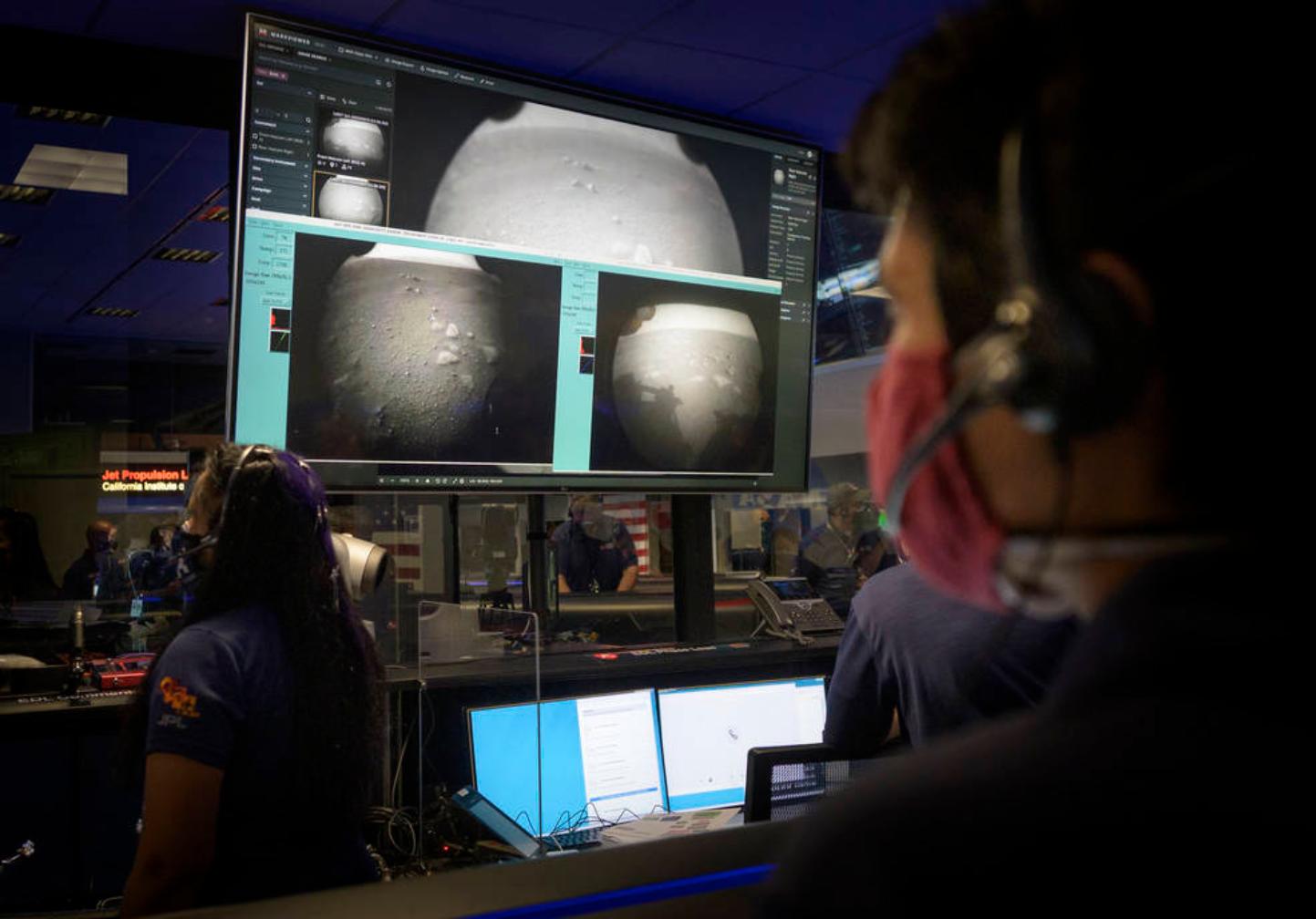

Touchdown! NASA's Mars Perseverance Rover Safely Lands On Red Planet

David Bowie – Life On Mars? (Official Video)

Council Receives 44.5K Grant For Events For Youth By Youth

'Events for Youth by Youth is an opportunity for young people to learn project management and be mentored by industry professionals and the Library and Youth team. Mentorship will upskill, inspire and empower young people to run events to improve access, inclusion, and subsequent wellbeing.'

NSW Youth Advisory Council 2021 Applications Now Open

- Question: What do you think are the important issues affecting children and young people in NSW? Please explain why you think these issues are important. (As a guide, your answers should be no more than 250 words.)

- Question: What life experiences have you had which would assist you in contributing to the Council’s work?

- Question: Details of any current or past voluntary or community activities you have been involved in.

- We'll ask a few questions about you and your background.

Applications Now Open For Y NSW Youth Parliament

NSW Youth Week 2021: 16 To 24 April

- share ideas

- attend live events

- have their voices heard on issues of concern to them

- showcase their talents

- celebrate their contribution to the community

- take part in competitions

- have fun!

High Schoolers To Study Skills Of The Future

Online Courses Added To Summer Skills Program

The Summer Skills program has been expanded to include seven TAFE NSW online short courses targeting school leavers from last year.

An expansion of fee-free Summer Skills training courses is now available for school leavers with new online courses on offer, as part of the JobTrainer initiative.

Minister for Skills and Tertiary Education Geoff Lee said the Summer Skills program, launched in November 2020, has expanded to include seven TAFE NSW online short courses targeting school leavers from last year.

“In designing the Summer Skills program, the NSW Government has ensured the training on offer is aligned to local industry needs,” he said.

“We need to provide the opportunities that help school leavers find their feet in these uncertain times. That’s why we’re delivering practical and fee-free training opportunities commencing this summer. Online learning is a terrific way to upskill at your own pace,”

Mr Lee said all the courses come from the $320 million committed to delivering 100,000 fee-free training places as part of the NSW Government’s contribution to the JobTrainer initiative.

“There are more than 100,000 fee-free training places available through TAFE NSW and approved providers for people across NSW to reskill, retrain and redeploy to growth areas in a post COVID-19 economy.

“I encourage anyone impacted by the pandemic to see what training options are available in 2021.”

Enrolments are open for Summer Skills training in:

- Cyber Concepts;

- Introduction to working in the health industry;

- Construction materials and Work Health and Safety;

- Mental health;

- Business administration skills;

- Introductory to business skills; and

- Digital security basics.

Visit the NSW Summer Skills webpage for full details on all available fee-free courses on offer and their eligibility as part of the NSW Summer Skills program, and visit the JobTrainer webpage for more information.

NSW JobTrainer provides fee-free* training courses for young people, job seekers and school leavers to gain skills in Australia's growing industries. Explore hundreds of qualifications and register your interest today.

Express Yourself Exhibition 2021

The talent and creativity of more than 40 HSC Visual Art students on the Northern Beaches will be on display for the annual Express Yourself exhibition at the Manly Art Gallery & Museum (MAG&M) from February 19th until March 28th 2021.

The winners of the $3,000 Manly Art Gallery & Museum Society Youth Art Award and $5,000 Theo Batten Bequest Youth Art Award will be announced on Friday 19th of February. These two awards are granted annually to students featured in the exhibition.

Artist statements will be displayed alongside the artworks describing the inspirations and influences that informed the works and the students’ creative journeys.

Visitors are encouraged to vote for their favourite artwork in the KALOF People’s Choice Award which is announced at the end of the exhibition period.

Express Yourself is also part of Art Month Sydney, March 2021.

Exhibition: 19 February - Sunday 28 March 2021, 10am - 4pm daily (excluding Mondays)

Teachers' preview: Friday 19 February, 5 - 6pm. Bookings essential via Council’s website

Art Walk and Talk: Saturday 27 February, 3 – 4pm: Artists walk through the exhibition and discuss their works with the curator. Bookings essential via Council’s website.

Here And There

The Dark Side Of Mobile Living Movements

21 times the Sun's mass: heaviest stellar black hole in the Milky Way is more massive than we thought

When one of us (Ilya Mandel) started grad school at the California Institute of Technology 20 years ago, he was greeted with a series of bets hanging on the wall outside the office of his PhD advisor, Kip Thorne.

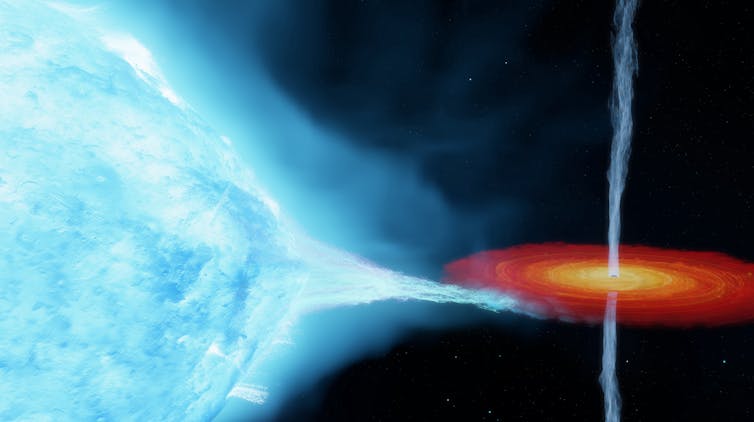

One bet from 1974 was a wager with theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, on whether an observed galactic X-ray source known as “Cygnus X-1” was actually a black hole feeding on hot gas.

Hawking bet it wasn’t, as a consolation prize in case black holes turned out not to exist (since this would mean a lot of the work he had done would be wasted).

At the time, black holes were exclusively theoretical predictions of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity: singularities in the fabric of space-time that prevented anything (including light) from escaping.

By 1990, astronomers were convinced Cygnus X-1, a binary star system, indeed hosted a black hole. Hawking conceded his bet against Thorne.

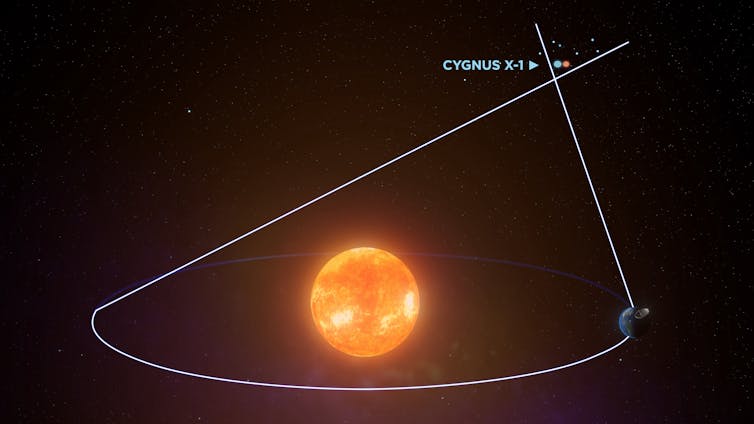

Three decades later, Cygnus X-1 is a gift that keeps on giving. In a paper published today in Science, our team reports the Cygnus X-1 black hole is heavier than previously thought, weighing about 21 times the mass of the Sun.

This makes it the heaviest stellar black hole — formed from the collapse of a star — ever detected without the use of gravitational waves. As it turns out, perhaps in line with a black hole not wanting to divulge its secrets, Cygnus X-1 still contains many mysteries.

Updated measurements from it are forcing us to revise our understanding of the most massive stars — particularly the rate at which they lose mass in stellar winds.

Introducing Cygnus X-1

Cygnus X-1 is located inside the Milky Way about 7,200 light years from Earth. It comprises what we now know to be a black hole in a 5.6-day orbit around a massive supergiant companion star.

Some of the gas blown off the surface of the star by its strong stellar wind is captured by the black hole. The gas spirals in towards the black hole, forming what’s known as an “accretion disk”.

Powerful jets (the contents of which are still debated) are also launched outwards from near the black hole, travelling close to the speed of light.

We wanted to measure the mass of the black hole. But to do so, we first needed to know how far away it was from Earth.

How Do You Weigh A Black Hole?

As Earth moves around the Sun, we see Cygnus X-1 from different vantage points. It appears to move back and forth very slightly against stationary background objects, in an effect we call “parallax”.

The amount of this tiny motion lets us calculate the distance between us and Cygnus X-1. But for an accurate measurement, we also had to take into account the orbital motion of the black hole around its companion star.

With a network of radio telescopes, we mapped out the black hole’s orbit, with a positional accuracy the equivalent of localising an object on the Moon to within ten centimetres.

By using our distance to Cygnus X-1 and the brightness and temperature of the star, we computed the size of the star. With this knowledge and the measured motion of the star during its orbit around the black hole, we could determine the black hole’s mass.

It is almost 50% more massive than previously thought, with a mass that’s 21 times that of the Sun.

Why Do We Care About Its Mass?

Seeing a stellar remnant this heavy in our own galaxy offers insight into how much mass stars can lose to stellar winds. In general, the larger and more luminous a star is, the faster its rate of mass loss.

Some stars lose the equivalent of an Earth’s mass of gas (or more) each day. Mass is lost faster if the star has a high concentration of heavy elements, particularly iron.

Black holes are created when massive stars collapse in on themselves. Thus, the heaviest black holes are expected to form from the deaths of massive stars with the lowest iron concentrations, as these would have retained the most mass up until death.

The current iron concentration in our Milky Way galaxy suggests even stars that weigh hundreds of times the mass of the Sun at birth could lose enough of it to leave behind a fairly pedestrian remnant — only a few times the mass of the Sun.

Now, finding a black hole with a mass that’s 21 times the Sun’s tells us these stellar winds can’t be that strong, after all. So it means we need to slightly retune our models of how stars lose mass through their winds.

Likely Not A Gravitational Wave Source

Cygnus X-1 is also interesting because it could potentially be a frame from a film showing the formation of pairs of black holes, which later merge to produce gravitational-wave signals.

These waves can be observed using advanced instruments, such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) in the United States.

According to our new measurements, the star in Cygnus X-1 weighs more than 40 times the mass of the Sun. It’s therefore massive enough to one day form a black hole in its own right.

Read more: Gravitational waves are helping us crack the mystery of how pairs of black holes form

However, while it’s tempting to say Cygnus X-1 provides a link between pairs of stars and merging black holes, that would come with its own challenges.

For example, as described in a companion paper to our Science paper, published in the Astrophysical Journal, the Cygnus X-1 black hole is spinning on its own axis almost as rapidly as general relativity allows.

By comparison, the merging black holes in LIGO sources have far slower spins. This suggests the pathway by which those black holes formed may have been somewhat different.

In another companion paper we argue Cygnus X-1 won’t make a gravitational-wave source because, after the collapse of the companion star, the resulting two black holes would be too far apart to merge.

Still, many questions remain regarding the history and the formation of Cygnus X-1, as well as its future. There may be a few more bets to be made and resolved, yet.![]()

James Miller-Jones, Professor, Curtin University and Ilya Mandel, Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The politics of the necktie — 'colonial noose', masculine marker or silk status symbol?

Lorinda Cramer, Australian Catholic UniversityNeckties made global news last week when Maori MP, Rawiri Waititi, was ejected from the debating chamber of New Zealand Parliament. He refused to wear a tie, evocatively describing it as a “colonial noose”.

It wasn’t that Mr Waititi eschewed neckwear. Rather, he explained that the traditional hei tiki — the greenstone pendant he wore instead — represented for him both a necktie and a tie to his people, culture and Maori rights.

In the intense debate that followed, ideas around acceptable business attire — long based on Western dress codes — were questioned against the expression of Indigenous cultural identity. Ties are now no longer required as part of men’s “appropriate business attire” in the NZ Parliament.

In Australia, Members of Parliament were allowed to ditch the necktie in 1977 when safari suits were officially considered business attire. Since then, however, Parliament House dress standards have informally shifted, with our male politicians uniformly donning ties in the chamber.

Ties have been tangled up in controversy here as in New Zealand. This narrow strip of fabric has many meanings for its wearers.

Read more: The tie that binds: unravelling the knotty issue of political sideshows and Māori cultural identity

From Throat To Groin

Shells, feathers, gold and fabrics have adorned people’s necks for millenia. The origin of the necktie is most commonly traced to 17th century Croatian mercenaries who wore cloth around their necks. One purpose was to protect the neck from the sword’s blade.

Cravats, draped or tied in bows, and “stocks” — a stiffened cloth that tied at the back of the neck — were worn in Europe for subsequent centuries, and by Australia’s early colonial administrators. They were made from lace, linen, silk and muslin.

The bow tie and the necktie — in a form recognisable today — were increasingly visible in the 19th century.

The tie’s symbolism attracts especially heated discussion around the styling of the masculine body. While the suit jacket creates a v-shape from the shoulders to the waist, the tie draws the eye from the throat to the groin — in the same way, some argue, as the codpiece did.

It has been suggested that this “overcompensation” explains former US President Donald Trump’s preference for long neckties, with one observer comparing them to the codpiece.

Read more: Research Check: do neckties reduce blood supply to the brain?

Tie-Wearing In Australia

When Captain James Cook landed on Australian shores, he was dressed in uniform with linen tied at his neck — or so many paintings suggest.

Early administrators, too, wore crisp, clean neckwear, while convicts had a neckerchief issued as part of their uniform.

Influential Aboriginal people, meanwhile, were sometimes presented with a breastplate to be worn around the neck.

Artist S. T. Gill illustrated life on the Victorian goldfields in the 1850s, with some of his hard-working diggers tying handkerchiefs around their necks. But the wastrels and dandies he drew splurged on flash clothing including vividly-coloured silk cravats worn with gold pins in the style of gentlemen.

In the early 20th century, as manual workers removed their jackets and ties, wearing a three-piece suit and necktie become shorthand for authority and professionalism.

As the business suit became a menswear staple at the turn of the 20th century, the popularity of ties skyrocketed. In 1950, when Sydney’s Sun newspaper published the Everyman’s Ideal Wardrobe, the extensive list recommended 18 ties alone.

However suits and ties were hot, if not oppressive, as Australia’s climate “dress reformers” insisted. When Ray Olson photographed David Jones’ new season fashions in 1939, he captured two men in contrasting attire walking along a city street.

One wore a fashionable double-breasted suit, jaunty hat and close-fitting tie. The other was dressed in a short-sleeved shirt — without a necktie — and tailored shorts. Radical for the time, this look was adopted decades later, with South Australian Premier Don Dunstan leading the charge on relaxed dress standards.

In 1967, The Bulletin described Dunstan’s ensemble of shorts, long socks and a short-sleeved shirt worn without a tie as a “summertime example” for government and bank employees.

Skinny, Wide, Loud Or Patterned

As attitudes to ties have transformed across decades, styles have gone in and out of fashion. The skinny tie popularised by bands such as the Beatles in the 1960s was favoured by young Australian mods.

The wide tie, too, has had its moments. In the 1970s, loud, wide patterned ties were the height of fashion. For flamboyant politician Al Grassby, wearing wide colorful ties signalled a move to “a new colorful Australia”.

Read more: A scarf can mean many things – but above all, prestige

These days politicians might wear certain colours to mark their allegiance: the coalition has a widely commented on preference for blue, for example, though this isn’t always evident.

Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt often chooses a necktie with an Indigenous design to signal his heritage.

Ties do many things. Though they express identity, they can just as readily act as a “uniform” for their wearers. They give power to some, while taking it from others. Does Rawiri Waititi’s criticism of the “colonial noose” suggest Australia, too, might be heading towards a reckoning with the tie’s place in our history?![]()

Lorinda Cramer, Postdoctoral Research Associate, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Guide to the classics: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland — still for the heretics, dreamers and rebels

Alice! A childish story take

And with a gentle hand

Lay it where Childhood’s dreams are twined

In Memory’s mystic band,

Like pilgrim’s withered wreath of flowers

Plucked in a far-off land.

What is it that draws us back to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Alice for short), both individually and collectively? What is it that makes Alice, in the words of literary critic, Harold Bloom, “a kind of Scripture for us” — like Shakespeare?

For we are drawn back. Since the publication of Lewis Carroll’s story, in England in 1865, it has never been out of print and has been translated into around 100 languages.

There have been numerous movie adaptations and many other works inspired by the story. Perhaps the greatest is a little-known, 1971 short film by the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare encouraging children not to do drugs.

One fears the film might not have had the desired effect: while the speed-addicted March Hare provides a salutary example of how poorly things can go on his drug of choice, the Mad Hatter’s performance on LSD is a little too compelling.

Beyond the page and screen, a quick Google search reveals Alice-inspired art — from graffiti to Dali — tattoos, music, video games and shops.

Alice has strong mainstream appeal; this was entrenched by Disney’s 1951 movie Alice in Wonderland (which is also responsible for people getting the title of the book wrong). However, Alice has become iconic for many subcultures, especially those with darker proclivities. Try exploring “zombie Alice” or “goth Alice”, or watching the new Netflix series, Alice in Borderland, which is set in Tokyo. (Alice is big in Japan).

And this brings us again to the beginning of the conversation (Alice reference here for the boffins): What draws us back?

Read more: Guide to the Classics: The Secret Garden and the healing power of nature

Striking A Blow Against The Adult World

The story begins with bored, seven-year-old Alice sitting on a riverbank with her older sister. Alice doesn’t care for the book her sister is reading because it doesn’t have pictures. She falls asleep and follows a dapper but flustered rabbit down a rabbit hole and into Wonderland.

In Wonderland she moves through a series of surreal vignettes in which she verbally tussles, but struggles to connect with, a stream of characters, such as the hookah-smoking Caterpillar, the Duchess, the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat and the Queen of Hearts.

We are drawn back to the book by the first-rate banter between Alice and these memorable characters. Consider the following from the Mad Hatter’s tea party:

“Then you should say what you mean,” the March Hare went on.

“I do,” Alice hastily replied; “at least — at least I mean what I say — that’s the same thing, you know.”

“Not the same thing a bit!” said the Hatter. “You might just as well say that ‘I see what I eat’ is the same thing as ‘I eat what I see’!”

“You might just as well say,” added the March Hare, “that ‘I like what I get’ is the same thing as ‘I get what I like’!”

“You might just as well say,” added the Dormouse, who seemed to be talking in his sleep, “that ‘I breathe when I sleep’ is the same thing as ‘I sleep when I breathe’!”

“It is the same thing with you,” said the Hatter[.]

Notably, many of the creatures Alice meets stand for the real adults in her life, in that they scold her, order her about, try to teach her morals and make her recite poetry.

It is this transformation of the adult world into a mad place and the elevation of the viewpoint of the child that also draw us back. When we read Alice, not as children, but as adults, we strike a blow against the adult world, which some of us, at least, have never quite adjusted to.

The Cheshire Cat provides the greatest indictment of Wonderland-as-adult-world when he says to Alice, “we’re all mad here”. The cat is the only creature in the book who connects with Alice. Mark this, reader: It is the one who can connect with children who is also able to see the world for what it is — mad!

A Champion Of Childhood

The West does have a long history of romanticising childhood. Wordsworth, in his 1807 Immortality Ode, writes:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

Upon the growing Boy.

But even if the “romantic childhood” is a creation of bourgeois 19th century England — of the likes of Wordsworth and Carroll — it is a powerful and arguably noble notion. So let us follow it a little farther down the rabbit hole.

While Alice is the child-hero of the story because she pushes back against the mad adults in Wonderland, she herself is on the cusp of adulthood.

This tragedy is alluded to in the poem, dedicated to the real Alice — Alice Liddell — with which the book begins (the key stanza appears at the start of this article).

Liddell was, in her childhood, Carroll’s friend. The first version of Alice was told to Liddell and her two sisters in 1862 on a boat ride along the Thames in Oxford.

The tragedy of growing up is reinforced in the story itself. While Alice’s imagination is able to create Wonderland, it cannot sustain it. In the final scene in Wonderland, Alice is watching a trial where many of the characters are playing cards. Frustrated by the illogical trial, she shouts, “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!” and is transported back to the real world.

This leads us to think Wonderland itself is the hero of Alice: the champion of childhood. It is in Wonderland that time has stopped — as we learn at the Mad Hatter’s tea party — and where authority is impotent. Despite the Queen’s repeated edict, “Off with her/his head”, no one ever really dies.

‘The Carroll Myth’

However, beyond Alice and Wonderland is Carroll himself. As Karoline Leach writes, in her remarkable book about “the Carroll myth”, at the centre of Alice lies, “the image of Carroll; a haunting presence in the story, a shifting dreamy impression of golden afternoons, fustiness, mystery, oars dripping in sun-rippling water.”

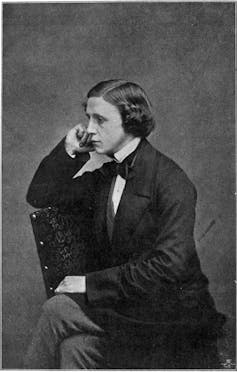

Lewis Carroll is the pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (not easy to say quickly, unlike “Lewis Carroll”), who taught mathematics at Oxford.

The “Carroll myth”, which was as appealing in the 19th century as it is now, is that Dodgson, through his alter ego Carroll, and his many (chaste) relationships with children, in particular, Alice Liddell, found a way back to the immortality of childhood that Wordsworth spoke about.

So, when we read Alice, we are ultimately communing with this mythical Carroll, and this is no small thing.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Orwell's 1984 and how it helps us understand tyrannical power today

Trolling Pieties

Beyond the banter and the homage to childhood, we are drawn back to Alice because it contains a timeless contribution to the 1860s version of our own culture wars. Where we have political correctness, the 19th century Anglophone world had its own buzz-killing piety, at times foisted upon children — and adults — through verse.

David Bates, a 19th century American poet, is likely responsible for the now thankfully forgotten poem, Speak Gently (“Speak gently to the little child!/Its love be sure to gain/Teach it in accents soft and mild:/It may not long remain.)

Carroll’s glorious parody, which is spoken in Chapter 6 by the Duchess, a negligent mother, is:

Speak roughly to your little boy,

And beat him when he sneezes:

He only does it to annoy,

Because he knows it teases.

Here, and in other Alice poems such as "You Are Old Father William”, Carroll is trolling all those for whom piety is a mask for power. And like the pious, the politically correct are more concerned with their own superiority than with doing good.

To cement the link between then and now, it is worth quoting from Stephen Fry’s recent objection to political correctness. It is as if Fry is providing us with the key to Alice and even to Carroll himself. “I wouldn’t class myself as a classical libertarian,” Fry says,

but I do relish transgression, and I deeply and instinctively distrust conformity and orthodoxy. Progress is not achieved by preachers and guardians of morality but […] by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels and sceptics.

We are drawn back to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland because when we read it, we become the heretics, dreamers and rebels who would change the world.![]()

Dr Jamie Q Roberts, Lecturer in Politics and International Relations, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Firestarter — the Story of Bangarra is a film of national and personal tragedies, with light in the dark

Review: Firestarter – the Story of Bangarra, directed by Wayne Blair and Nel Minchin

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

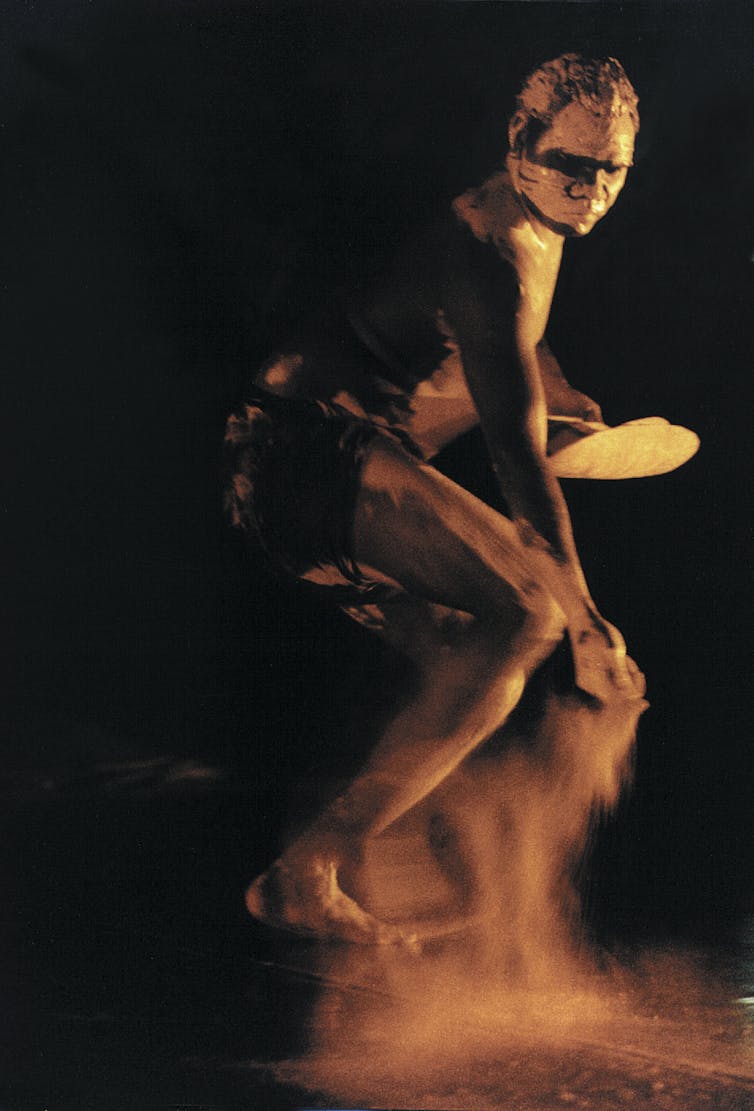

Watching Firestarter is like being immersed in a Knowledge Story. A story that contains deep, secret knowledge at its heart, while sharing an outside, public version. If I had to sum up the outside layer of this story, I would say it is one about energy transformation.

The film gives insight into the emergence of contemporary Indigenous dance in 1970s Australia. It’s a story about embodied activism birthed by founding figures such as Carole Y Johnson and Cheryl Stone through the fusion of contemporary dance forms with ancient living ones.

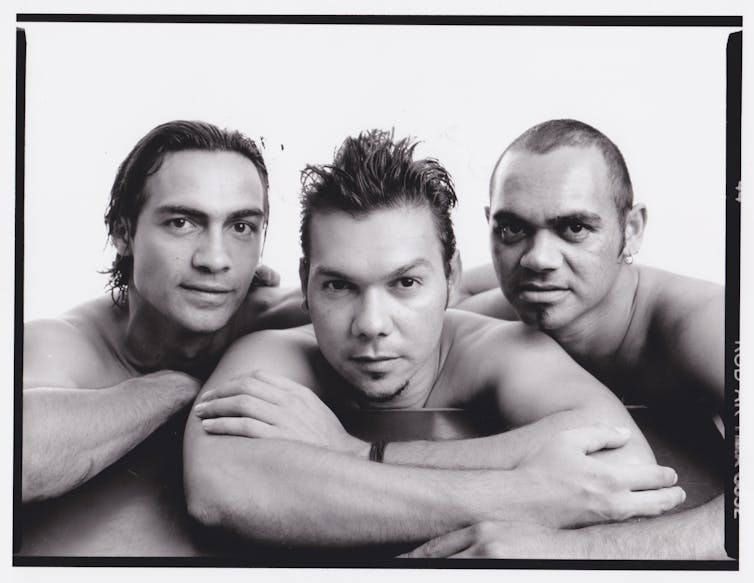

And it’s the story of three Page brothers — choreographer Stephen, composer David and dancer Russell — who established the iconic style that is Bangarra movement.

Since 1989, Bangarra Dance Theatre has used dance to craft spaces in important national moments. The opening ceremony of the 2000 Olympics, for example, allowed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge of movement, music and song to be seen, heard and felt.

And just as a public version of a Knowledge Story helps make connections to deeper meanings, Firestarter gives you access to stories containing ancient wisdom fused with contemporary colonial trauma.

Read more: What are message sticks? Senator Lidia Thorpe continues a long and powerful diplomatic tradition

Dreaming To Today

If you’ve ever seen a Bangarra performance you will know that dance is a thread straight to the Dreaming. A ceremonial form with physical and metaphysical knowledge embodied by, and shared with, movement.

Watching the documentary, like watching a Bangarra performance, requires you to pay attention, make connections, explore possible interpretations and potentially be transformed by the telling of it.

The founding of the Aboriginal Islander Dance Theatre in 1975 was a moment in this nation-state’s history that saw the hearts, minds and bodies of mobs of different Blackfellas merge together to begin to shape what would become Australia’s leading Indigenous dance movement.

The dance theatre’s transition into the National Aboriginal and Islander Skills Development Association — better known as Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Dance College — cemented the fusion of cultural knowledges, dance forms, political activism and historical events that would lead to the birth of Bangarra, a Wiradjuri word meaning “to make fire”.

Bangarra has always been both a mirror and a portal. It reflects the aliveness and sentience of stories that come from different mobs and their Countries across Australia while at the same time navigating ongoing colonial trauma.

Through the sharing of stories — the dilemma of how we remember Bennelong, a long history of cultivation through Dark Emu (based on Bruce Pascoe’s book), the yearning for cultural connection in Blak, of the Stolen Generation in Mathinna — the company allows moments of moving through the traumatic to access glimpses of love, healing, transformation and possibilities.

Contemporary Indigenous dance speaks to and of survival, despite 200-odd years of colonial policies aimed at ensuring cultural disconnection.

As the association’s co-founder Carole Y Johnson says in the film: