Inbox and Environment news: Issue 486

March 7 - 13, 2021: Issue 486

Wanted: Sydney's Precious Woody Elders

- A home - birds, bats, frogs, possums and gliders and reptiles will live in and on these stags

- A nursery - the hollow cavities in particular provide a place for some of our favourite creatures like owls and parrots (including some Threatened species) to lay eggs and raise young

- A snack - invertebrates, fungi, mosses and lichen will feed upon decaying wood, and so in turn provide food for our wildlife

- A safe lookout - stags often give unique vantage points for wildlife, especially raptors to look for prey

- are in Sydney

- are at least 85 to 95 cm around at chest height

- have at least one hollow/cavity of 40cm or larger at the entrance

The Coast On Radio Northern Beaches - Every Friday With Wendy Frew

- Episode 6, Season 2: Starry, Starry Night by "The Coast" - Wendy Frew

- Episode 5, Season 2: Finding Nemo by "The Coast" - Wendy Frew

- Episode 3, Season 2: Giants of the Sea by "The Coast" - Wendy Frew

- Episode 2, Season 2: Birds of a Feather by "The Coast" - Wendy Frew

- Episode 1, Season 2: An Everyday dose of nature by "The Coast" - Wendy Frew

The Coast

Radio Northern Beaches

ORRCA Autumn News: Victoria To Implement Ban On Plastic + Whales Are On The Move - Already!

BirdLife Australia Autumn Survey Time

- Breeding behaviours - If you see a bird carrying nesting materials, sitting on a nest or feeding chicks, let us know. Select the option under 'Breeding Activity' that best matches your observation (remember to keep your distance though from birds who are breeding. We don't want to disturb any nests. Be sure to limit your observations and don't get close enough to scare a bird off it's nest.)

- Aggressive interactions – Let us know if you have observed any species initiate interactions with other birds and whether this interaction could be classed as aggressive – you can do this in the sighting details tab using the specific species interactions option.

- Have you seen any birds feeding on the native plants in your garden? If so – who was dining on what? – you can tell us in the notes section when you record the species you have observed under “sighting details”

- Have any birds been dabbling in some Oscar-worthy acting? – tell us about the weird and wonderful things your backyard birds have been up to you using the notes section in the sighting details tabs.

Narrabeen Lagoon Clean Up: March 28

Weed Of The Week: Cassia - Please Pull Out And Save Our Bush

Pink Flush Across Blue Mountains

Pink flannel flowers (Actinotus forsythii) only bloom a year or so after a bushfire.

They're known as bushfire ephemerals because their seeds lay dormant for years on end without any reports. Until the right mix of fire and rain bring them back to life.

Take these flowers' recent appearance in the Blue Mountains. The 2019-20 fire season damaged 80% of the area. But rainfall in the region then enabled these flowers to bloom.

Photos taken at State Mine Gully Rd, Lithgow - by and courtesy Kerry Smith

Invasive Turtles Terrorising Sydney's Wildlife Tracked Down By Scent Detector Dogs

March 5, 2021

Scent detector dogs who ‘nose out’ invasive pests have swarmed Sydney’s parklands as the NSW Government unleashed a specially-trained squad in a calculated raid to eradicate an alien turtle species from our waterways and wetlands.

Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall said they might look harmless, but the red-eared slider turtles were introduced from North and Central America and posed a serious biosecurity threat, preying on native turtle species.

“Red-eared slider turtles are one of the world’s worst invasive alien species,” Mr Marshall said.

“These turtles are an extremely serious introduced biosecurity threat, and we need to extinguish them from our water-ways.

“Our highly trained scent detector dogs have the ability to nose out traces of these invaders above and below the water. While experts in camouflage, the red-eared slider turtles have nowhere to hide.

“These invasive turtles came from the United States and Mexico, and they prey on our native species, fish and frogs, compete for food, nesting areas and basking sites, and can even spread infectious salmonella bacteria to people, pets and other animals.

“We have already removed hundreds of red-eared slider turtles from Sydney waterways and the hands of illegal keepers, but this is just the start.”

The NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) collaborated with Greater Sydney Local Land Services, Centennial Parklands Trust, local councils and University of Canberra to develop a new range of tracking and trapping devices being trialled.

Mr Marshall said keeping red-eared slider turtles as pets was prohibited and they were an issue on the black market.

“These alien species have been smuggled into, illegally kept and illegally released in Australia which have been found across the Sydney basin, from Camden north to Woy Woy and west to Windsor,” Mr Marshall said.

“They are often illegally purchased when they are very small and attractive, but grow rapidly into large adults capable of biting their owners.

“Red-eared slider turtles might appear to be an ideal pet when small, but they are vicious. If you see one, or you have inadvertently purchased one - or have one that you no longer wish to keep – contact us immediately so we can safely remove them.”

Members of the community are advised to be on the lookout for unusual non-native animals, including turtles, snakes, lizards and other reptiles, mammals, birds and amphibians.

If you see a red-eared slider turtle or any other illegal invasive animals, please contact NSW DPI on 1800 680 244 or take a photograph and post the details on NSW DPI’s unusual animal form.

Image: “Bunya” and his handler, Bradley, tracking down a red-eared slider turtle. NSW DPI photo.

Red-eared slider Turtle. NSW DPI photo.

Orange-Bellied Parrot Breeding Success

With such a small population, the Orange-bellied Parrot is often the subject of gloomy news, but thanks to the success of recent conservation efforts, there are now some good tidings for this Critically Endangered species.

With such a small population, the Orange-bellied Parrot is often the subject of gloomy news, but thanks to the success of recent conservation efforts, there are now some good tidings for this Critically Endangered species.Design And Place State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP): Open For Feedback Until March 31

'The Design and Place SEPP puts place and design quality at the forefront of development. Our shared responsibility to care for Country and sustain healthy, thriving communities underpins the policy. The SEPP spans places of all scales, from precincts, significant developments, and buildings to infrastructure and public space. ''The public exhibition will allow us to work closely with state government, local councils, industry peak bodies and communities. This process will inform the development of the Design and Place SEPP and safeguard our shared values for future development in NSW. We will draft the policy in 2021, following the review of the formal submissions and feedback. Submissions are open from now until 31 March 2021. 'The final Design and Place SEPP will go on public exhibition later in 2021 to provide more opportunities for feedback. We will also develop supporting guidance and tools alongside the policy. These include a revision to the Apartment Design Guide, improvements to the Building Sustainability Index (BASIX) tool and the development of a new Public Space and Urban Design Guide. '

Worth Noting: Australian Car Sales Statistics 2020

- There were 1,062,867 new vehicles sold in Australia 2019

- New car sales in Australia dropped 8% down from 2018, making it the lowest since 2011

- Toyota was the top-selling car brand in 2019, with 205,766 total sales

- SUVs accounted for 45.5% of new car sales in 2019

NSW Department Of Planning Projects On Exhibition: Open For Comment

- your name and address, at the top of the letter only;

- the name of the application and the application number;

- a statement on whether you ‘support’, ‘object’ to the proposal or are only making a comment;

- the reasons why you support or object to the proposal; and

- a declaration of any reportable political donations you made in the previous two years.

- > A new 500/330 kilovolt (kV) substation located within Bago State Forest and adjacent to TransGrid’s existing Transmission Line 64 (Line 64)

- > Two 330 kV double-circuit overhead transmission lines, approximately nine kilometres long, linking the Snowy 2.0 cable yard in Kosciuszko National Park (KNP) to the new substation

- > An overhead transmission line connection between the substation and Line 64

- > Construction of new access tracks and upgrade of existing access tracks where required to facilitate the construction of the transmission lines and substation and service ongoing maintenance activities

- > Establishment of temporary sites and infrastructure needed during construction including crane pads, site compounds, a helipad, equipment laydown areas, and tensioning and pulling sites for the stringing of overhead conductors and earthwires.

- increased open cut coal extraction within the approved Mount Pleasant Project (EPBC 2011/5795) development area, including accessing deeper coal reserves in North Pit;

- staged increase in the extraction, handling and processing of ROM coal up to 21 Mtpa (i.e. progressive increase in ROM

- coal mining rate from 10.5 Mtpa over the Project life); and

- continued use of the controlled release dam and associated infrastructure that was approved through Bengalla Mine State and Federal approvals.

- Under the proposed Action, mining operations at the higher production rate would extend to 22 December 2048

Forestry Corporation Fined $33K For Failing To Keep Records: Endangering Swift Parrots

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) has issued Forestry Corporation of NSW (FCNSW) with two penalty notices for allegedly not including the critically endangered Swift Parrot records in planning for operations, and has also delivered three official cautions for an alleged failure by FCNSW to mark-up eucalypt feed trees, an essential source of food for the birds, prior to harvesting.

The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) has issued Forestry Corporation of NSW (FCNSW) with two penalty notices for allegedly not including the critically endangered Swift Parrot records in planning for operations, and has also delivered three official cautions for an alleged failure by FCNSW to mark-up eucalypt feed trees, an essential source of food for the birds, prior to harvesting.Forestry Corporation Fined For Failing To Mark Out A Prohibited Logging Zone

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Pittwater Reserves

Endangered Turtles Troop Back To Bellinger River

March 3, 2021

Over 30 critically endangered Bellinger River snapping turtles, bred at Taronga Zoo, have been returned to their Bellinger River habitat and appear to be well after recent floods.

Back to the wild for a rare Bellinger River snapping turtle (Myuchelys georgesi) - Photo courtesy Taronga Zoo

It is the only place in the world where they are found but in 2015 a devastating virus wiped out 90% of the turtles in just six weeks.

After a breeding program was rapidly developed, this release further boosts the population after earlier releases in 2018 and 2019, bringing the total number of turtles now released to 52.

Gerry McGilvray, a Department of Planning Industry and the Environment (DPIE) Threatened Species Officer, said after the Bellinger River Virus hit, a partnership led by the Saving our Species (SoS) program established a captive breeding program to ensure the species’ survival.

Gerry said: “This 3rd release of turtles since 2018 is excellent news for these animals, which are unique to the Bellinger River catchment and were declared Critically Endangered after the virus.”

Soon after the turtles were released, the Bellingen area and other parts of the north coast experienced heavy rain and flash flooding but threatened species experts and monitoring the released turtles have confirmed the turtles are safe.

Taronga Zoo staff used their expert skills to establish an insurance population to breed animals for the releases, with over 100 turtles now at the zoo’s quarantine facility. A second insurance population has also been developed at Symbio Wildlife Park.

Taronga Zoo Chief Executive and Director, Cameron Kerr, said that the release was a humbling moment following years of hard work and dedication by zoo staff.

“Bellinger River snapping turtles are considered one of Australia’s most critically endangered animals, and I am incredibly proud of the work of our dedicated keepers and scientists that has led to the release of these healthy individuals into the wild,” Mr Kerr said.

Radio transmitters attached to the turtles help locate them for regular monitoring by SoS Threatened Species Officers who also capture the turtles intermittently to measure growth rates, determine body condition, assess general health and look for signs of exposure to the virus.

The Bellinger River snapping turtle is a short-necked freshwater turtle in the family Chelidae first observed by John Cann in 1971.

The release was approved by the DPIE and Environment Animal Ethics Committee and was guided by reptile and translocation experts, wildlife disease experts and zoo professionals.

Major partners include Symbio Wildlife Park, Department of Primary Industries, Bellinger Landcare, OzGREEN, local community members and researchers.

PFAS Firefighting Foam Banned In NSW

- banning the use of any PFAS firefighting foam for training and demonstration purposes from April 2021;

- restricting the use of long-chain PFAS firefighting foam from September 2022; and,

- restricting the use and sale of PFAS firefighting foam in portable fire extinguishers from September 2022.

NSW lifts ban on Genetically Modified crops

Crab Population To Improve With Recreational Size Limit Changes

March 3rd, 2021

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) Fisheries has announced changes to recreational Blue Swimmer Crab size limits set to come into effect from 30 April 2021.

NSW Department of Primary Industries (DPI) Fisheries has announced changes to recreational Blue Swimmer Crab size limits set to come into effect from 30 April 2021.

The NSW Department of Primary Industries Deputy Director General Fisheries Sean Sloan said these changes will result in an overall improvement in the abundance of crabs.

“The small increase in the size limit for blue swimmer crabs from 6.0cm to 6.5cm will assist total egg production by protecting spawning crabs and improve the productivity of the stock over time,” Mr Sloan said.

“It will also provide consistency between the recreational and commercial fishing sectors and provide an overall improvement in the abundance of crabs.

“The changes will come into effect on 30 April this year so we wanted to give fishers as much notice as possible.

“NSW Fisheries will be out in the community over the coming weeks to speak to fishers to make sure they are aware of the changes and answer any questions they may have."

Mr Sloan said these changes have been implemented following consultation with and support from the NSW Recreational Fishing Advisory Council.

“These changes are being implemented following consultation with and support from the NSW Recreational Fishing Advisory Council who do a fantastic job representing the interest of fishers,” Mr Sloan said.

“The recreational fishing industry is worth $3.4 billion in economic activity every year so it’s critical we all work together to ensure the sustainability of this fantastic resource."

More information about the recreational fishing rule changes are available online at www.fisheries.nsw.gov.au, or by contacting your local NSW DPI Fisheries office.

New Yabby Net Give-Away

March 3, 2021

The NSW Government is giving away 5,000 yabby nets to recreational fishers as part of a comprehensive program to phase out the use of enclosed yabby traps in NSW from 30 April 2021. Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall said the government has been transitioning to open-top nets for some time, due to the risk that enclosed yabby traps can pose to native wildlife.

“We know that ‘opera house’ style yabby traps pose a risk to air breathing animals such as platypus, water rats and turtles, which can inadvertently get caught in traps,” Mr Marshall said.

“Open top nets allow mammals to exit through the top, unlike opera house traps which only have openings on the sides.

“By moving away from ‘opera’ style traps to open-top yabby nets, we will allow both our fishing resources and native animal populations to flourish.”

Mr Marshall said the changes are part of a National process, with ‘opera’ style traps having already been phased out in the ACT, Victoria and NSW waters where platypus are mostly abundant, including east of the Newell Highway as well as parts of the Edward, Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers.

“These changes have been implemented following consultation with and support from the NSW Recreational Fishing Advisory Council and we want to give fishers has much time as possible to make sure that they’re aware of the new rules and ensure they have the right equipment,” Mr Marshall said.

“By transitioning to using open top nets, fishers can keep fishing, while also continue to do their part to protect our wildlife and ensure the ongoing health of our inland river systems.”

From 30 April, up to five nets, comprised of either open pyramid lift nets, hoop / lift nets or a combination of both, can be used to catch yabbies in all inland waters where it is legal to use lift nets. For more information, visit the DPI website.

To assist with this transition, the Department of Primary Industries are giving away 5,000 open-top nets. To collect a free open-top yabby net, please phone (02) 6051 7760.

More information about the recreational fishing rule changes are available online at www.fisheries.nsw.gov.au, or by contacting your local NSW DPI Fisheries office.

NSW DPI Fisheries Officer inspecting an opera style trap

EPA Takes Legal Action Against Cleanaway For Pollution Of River

Former Truegain Director Convicted, Fined For Failing To Supply Information

NSW State Water Strategy: Have Your Say

Senate Inquiry Into Environment Protection And Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Regional Forest Agreements) Bill 2020

''This Bill will affirm and clarify the Commonwealth’s intent regarding Regional Forest Agreements to make it explicitly clear that forestry operations in a Regional Forest Agreement region are exempt from Part 3 of the EPBC Act, and that compliance matters are to be dealt with through the state regulatory framework.

Requiring native forestry operations to seek EPBC Act approval would create operationally unviable delays in planned harvesting operations that have already been subjected to significant environmental planning and approvals and create congestion in the approvals pipeline.

This is achieved by removing the ambiguity of what it means to be “undertaken in accordance with a Regional Forest Agreement” (subsection 38(1) of the EPBC Act), which a recent Federal Court decision (Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 4) [2020] FCA 704 has shown is not explicit with respect to the Commonwealth’s intended meaning.

Furthermore, the operation of subsection 38(1) is just one of several legal questions considered by Justice Mortimer’s judgment and subsequent appeal. There is no guarantee that the appeal will deal with the substantive question about the operation of subsection 38(1).

The Independent review of the EPBC Act Interim Report (Samuel 2020) recommended addressing this uncertainty:

- “During the course of this Review, the Federal Court found that an operator had breached the terms of an RFA and should therefore be subject to the ordinary controlling provisions of the EPBC Act. Legal ambiguities in the relationship between EPBC Act and the RFA Act should be clarified, so that the Commonwealth’s interests in protecting the environment interact with the RFA framework in a streamlined way.” (page 10), and

- “The EPBC Act recognises the RFA Act, and additional assessment and approvals are not required for forestry activities conducted in accordance with an RFA (except where forestry operations are in a World Heritage property or a Ramsar wetland). These settings are colloquially referred to as the 'RFA exemption', which is somewhat of a misnomer.” (page 60).

The Interim Report also made it clear that under a regional model of empowering the states, the oversight functions would be the responsibility of the states through accredited frameworks (as occurs with Regional Forest Agreements):

“For projects approved under accredited arrangements, the accredited regulator would be responsible for ensuring that projects comply with requirements, across the whole project cycle including transparent post-approval monitoring, compliance and enforcement. The Commonwealth should retain the ability to intervene in project-level compliance and enforcement where egregious breaches are not being effectively enforced by the accredited party.” (page 55).

''The Commonwealth must act urgently to resolve this uncertainty to ensure that the tens of thousands of jobs that depend on Australia’s native forestry operations are not exposed to the sort of crisis now facing Victoria’s native hardwood sector. This amendment Bill will achieve this outcome.''

- First reading: Text of the bill as introduced into the Parliament

- Third reading: Prepared if the bill is amended by the house in which it was introduced. This version of the bill is then considered by the second house.

- As passed by both houses: Final text of bill agreed to by both the House of Representatives and the Senate which is presented to the Governor-General for assent.

NSW Government Plan To Protect And Preserve Bushfire Affected Biodiversity

- developing conservation plans for threatened species and communities facing the most significant fire impacts

- establishing new breeding and propagation programs for priority threatened species

- continuing to implement comprehensive post-fire feral animal and weed control

- monitoring species, ecosystems and landscapes over the long-term

- building the capacity of the wildlife rescue and rehabilitation sector and fire combat agencies to respond to future fire events

- increasing opportunities for Aboriginal people to practice cultural fire management and manage fire-affected sites.

Look up! A powerful owl could be sleeping in your backyard after a night surveying kilometres of territory

Picture this: you’re in your backyard gardening when you get that strange, ominous feeling of being watched. You find a grey oval-shaped ball about the size of a thumb, filled with bones and fur — a pellet, or “owl vomit”.

You look up and see the bright “surprised” eyes of a powerful owl staring back at you, with half a possum in its talons.

This may be becoming a familiar story for many Australians. We strapped tracking devices to 20 powerful owls in Melbourne for our new research, and learned these apex predators are increasingly choosing to sleep in urban areas, from backyard trees to city parks.

These respite areas are critical for species to survive in challenging urban environments because, just like for humans, rest is an essential behaviour to conserve energy for the day (or night) ahead.

Our research highlights the importance of trees on both public and private land for wild animals. Without an understanding of where urban wildlife rests, we risk damaging these urban habitats with encroaching development.

One Owl, One Year, 300 Possums

Powerful owls are Australia’s largest, measuring 65 centimetres from head to tail and weighing a hefty 1.6 kilograms. They’re found in Australia’s eastern states, except for Tasmania.

These owls have traditionally been thought to live only in large old-growth forested areas. However, Victoria has lost over 65% of forest cover since European settlement, and because of this habitat loss, the owls are listed as threatened in Victoria.

Their remaining habitat is extremely fragmented. This means we’re finding owls in interesting places — from dry, open woodland to our major east coast cities. This is likely due to the high numbers of prey, such as possums, that thrive alongside exotic garden trees and house roofs.

Read more: Don't disturb the cockatoos on your lawn, they're probably doing all your weeding for free

Powerful owls usually eat one possum per night, or 250-300 possums per year — mostly common ringtail and brushtail possums in Melbourne. They’re often seen holding prey at their roosting spots, where they’ll finish eating in the evening for breakfast.

This has ecosystem-wide benefits, as powerful owls can help keep overabundant possums in check. Too many possums can strip away vegetation, causing it to die back, which stops other wildlife from nesting or finding shelter.

Tracking Their Nocturnal Haunts

But powerful owls are extremely elusive. With low populations, locating owls and researching their requirements is very difficult.

So, to help narrow down the general areas where powerful owls live in Melbourne, we used species distribution models and sought help from land management agencies and citizen scientists.

Over five years, we deployed GPS devices on 20 Melburnian owls to find how they use urban environments. These devices automatically record where the owls move at night and rest during the day.

We learned they fly, on average, 4.4 kilometers per night through golf courses, farms, reserves and backyards looking for dinner and defending their territory. One owl along the Mornington Peninsula travelled 47 km over two nights (possibly in search of a mate). Another urban owl called several golf courses in the Melbourne suburb of Alphington home.

Choosing Where To Sleep

After their nightly adventures, the owls usually return to a number of regular roosting (resting) spots, sometimes on the exact same branch. The powerful owl chooses roosts that protect them against being mobbed by aggressive daytime birds, such as the noisy miner and pied currawong.

We found the owls used 32 different tree species to roost in: 23 were native, and nine were exotic, including pine and willow trees. This shows powerful owls can adapt to use a range of species to fit their roosting requirements, such as thick foliage to hide in during the day.

Owls will generally roost in damp, dark areas during summer, and in open roosts in full or dappled sunlight during winter to help regulate their body temperature.

Read more: Urban owls are losing their homes. So we're 3D printing them new ones

Our research also shows rivers in urban environments are just as important as trees for roosting habitat.

Rivers are naturally home to a diverse range of wildlife. Using trees near rivers to rest in may be a strategic decision to reduce time and energy when travelling at night to find other resources, such as prey, mates and nests.

Rivers that constantly flow, such as the Yarra River, are a particular favourite for the owls.

The Urban Roost Risk

These resting habitats, however, are under constant pressure by urban expansion and agriculture. Suitable roosting habitat is either removed, or degraded in quality and converted to housing, roads, grass cover or bare soil.

We found potentially suitable roosting habitat in Melbourne is extremely fragmented, covering just 10% of the landscape because owls are very selective about where they sleep.

Although there might be the odd suitable patch (or tree) to roost in urban environments, what’s often lacking is natural connectivity between patches. While owls are nocturnal, they still need places to rest in the night before they settle down in another spot to sleep for the day.

Supplementing habitat with more trees on private property and enhancing the quality of habitat along river systems may encourage owls to roost in other areas of Melbourne.

Powerful owls don’t discriminate between private land and reserves for roosting. So conserving and enhancing resting habitats on public and private land will enable urban wildlife to persist alongside expanding and intensifying urbanisation.

So What Can You Do To Help?

If you want powerful owls to roost in your backyard, visit your local indigenous nursery and ask about trees local to your area.

Several favourite roost trees in Melbourne include many Eucalyptus species and wattles. If you don’t have the space for a large tree, they will also roost in the shorter, dense Kunzea and swamp paperbark (Melaleuca ericifolia).

Planting them will provide additional habitat and, if you are lucky, your neighbourhood owls may even decide to settle in for the day and have a snooze.

Read more: Hard to spot, but worth looking out for: 8 surprising tawny frogmouth facts ![]()

Nick Bradsworth, PhD Candidate, Deakin University; John White, Associate Professor in Wildlife and Conservation Biology, Deakin University, and Raylene Cooke, Associate Professor, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Birds on beaches are under attack from dogs, photographers and four-wheel drives. Here's how you can help them

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this new series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

Each year, oystercatchers, plovers and terns flock to beaches all over Australia’s coastline to lay eggs in a shallow scrape in the sand. They typically nest through spring and summer until the chicks are ready to take flight.

Spring and summer, however, are also when most people visit the beach. And human disturbances have increased breeding failure, contributing to the local contraction and decline of many beach-nesting bird populations.

Take Australian fairy terns (Sternula nereis nereis) in Western Australia, the primary focus of my research and photography, as an example. Their 2020-21 breeding season is coming to an end, and has been relatively poor.

Fox predation and flooding from tidal inundation wiped out several colonies. Unfathomably, a colony was also lost after a four-wheel drive performed bog-laps in a sign-posted nesting area. Unleashed dogs chased incubating adults from their nests, and photographers entered restricted access sites and climbed fragile dunes to photograph nesting birds.

These human-related disturbances highlight the need for ongoing education. So let’s take a closer look at the issue, and how communities and individuals can make a big difference.

Nesting On The Open Beach

Beach-nesting birds typically breed, feed and rest in coastal habitats all year round. During the breeding season, which varies between species, they establish their nests above the high-water mark (high tide), just 20 to 30 millimetres deep in the sand.

Some species, such as the fairy tern, incorporate beach shells, small stones and organic material like seaweed in and around the nest to help camouflage their eggs and chicks so predators, such as gulls and ravens, don’t detect them easily.

While nests are exposed and vulnerable on the open beach, it allows the birds to spot predators early and to remain close to productive foraging areas.

Still, beach-nesting birds live a harsh lifestyle. Breeding efforts are often characterised by low reproductive success and multiple nesting attempts may be undertaken each season.

Eggs and chicks remain vulnerable until chicks can fly. This takes around 43 days for fairy terns and about 63 days for hooded plovers (Thinornis rubricollis rubricollis).

Disturbances: One Of Their Biggest Threats

Many historically important sites are now so heavily disturbed they’re unable to support a successful breeding attempt. This includes the Leschenault Inlet in Bunbury, Western Australia, where fairy tern colonies regularly fail from disturbance and destruction by four-wheel drives.

Species like the eastern hooded plover and fairy tern have declined so much they’re now listed as “vulnerable” under national environment law. It lists human disturbance as a key threatening process.

Read more: One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

Birds see people and dogs as predators. When they approach, nesting adult birds distance themselves from the nest and chicks. For example, terns typically take flight, while plovers run ahead of the threat, “leading” it away from the area.

When eggs and chicks are left unattended, they’re vulnerable to predation by other birds, they can suffer thermal stress (overheating or cooling) or be trampled as their cryptic colouration makes them difficult to spot.

Unlike plovers and oystercatchers, fairy terns nest in groups, or “colonies”, which may contain up to several hundred breeding pairs. Breeding in colonies has its advantages. For example, collective group defence behaviour can drive off predatory birds such as silver gulls (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae).

However, this breeding strategy can also result in mass nesting failure. For example, in 2018, a cat visiting a colony at night in Mandurah, about 70 km south of Perth, killed six adults, at least 40 chicks and led to 220 adult birds abandoning the site. In other instances, entire colonies have been lost during storm surges.

Small Changes Can Make A Big Difference

Land and wildlife managers are becoming increasingly aware of fairy terns and the threats they face. Proactive and adaptive management combined with a good understanding of early breeding behaviour is helping to improve outcomes for these vulnerable birds.

Point Walter, in Bicton, WA, provides an excellent example of how recreational users and beach-nesting birds can coexist.

Point Walter, 18 km from Perth city, is a popular spot for picnicking, fishing, kite surfing, boating and kayaking. It’s also an important site for coastal birds, including three beach-nesting species: fairy terns, red-capped plovers and Australian pied oystercatchers (Haematopus longirostris).

The end of the sand bar is fenced off seasonally, and as a result the past six years has seen the number of terns increase steadily. For the 2020-2021 season, the sand bar supported at least 150 pairs.

The closure also benefits the local population of red-capped plovers and Australian pied oystercatchers, who nest at the site each year.

What’s more, strong community stewardship and management interventions by the City of Mandurah to protect a fairy tern colony meant this season saw the most successful breeding event in more than a decade — around 110 pairs at its peak.

Interventions included temporary fencing, signs, community education and increased ranger patrols. Several pairs of red-capped plovers also managed to raise chicks, adding to the success.

These examples highlight the potential for positive outcomes across their breeding range. But intervention during the early colony formation stage is critical. Temporary fencing, signage and community support are some of our most important tools to protect tern colonies.

So What Can You Do To Protect Beach-Nesting Birds?

share the space and be respectful of signage and fencing. These temporary measures help protect birds and increase their chance of breeding success

keep dogs leashed and away from known feeding and breeding areas

avoid driving four-wheel drive vehicles on the beach, particularly at high tide

keep cats indoors or in a cat run (enclosure)

if you see a bird nesting on the beach, report it to local authorities and maintain your distance

avoid walking through flocks of birds or causing them to take flight. Disturbance burns energy, which could have implications for breeding and migration.

Read more: Don't let them out: 15 ways to keep your indoor cat happy ![]()

Claire Greenwell, PhD Candidate, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Dig this: a tiny echidna moves 8 trailer-loads of soil a year, helping tackle climate change

After 200 years of European farming practices, Australian soils are in bad shape – depleted of nutrients and organic matter, including carbon. This is bad news for both soil health and efforts to address global warming.

The native Australian echidna may hold part of the solution. Echidnas dig pits, furrows and depressions in the soil while foraging for ants. Our research has revealed the significant extent to which this soil “engineering” could benefit the environment.

Echidnas’ digging traps leaves and seeds in soil. This helps improve soil health, promotes plant growth and keeps carbon in the soil, rather than the atmosphere.

The importance of this process cannot be underestimated. By improving echidna habitat, we can significantly improve soil health and boost climate action efforts.

Nature’s Excavators

Many animals improve soil health through extensive digging. These “ecosystem engineers” provide a service that benefits not only soils, but plants and other organisms.

In Australia, most of our digging animals are either extinct, restricted or threatened. But not so the echidna, which is still relatively common in most habitats across large areas of the continent.

Echidnas are prolific diggers. Our long-term monitoring at Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Scotia Sanctuary, in southwest New South Wales, suggests one echidna moves about seven tonnes – about eight trailer loads – of soil every year.

Soil depressions left by echidnas can be up to 50cm wide and 15cm deep. When ants are scarce, such as at highly degraded sites, echidnas dig deeper to find termites, making even larger pits.

This earth-moving capacity unwittingly provides another critically important function: matchmaking between seeds and water.

Playing Cupid

For seeds to germinate they must come together with water and soil nutrients. Our experiment showed how echidna digging helps make that happen.

We tested whether seeds would be trapped in echidna pits after rain. We carefully marked various seeds with different coloured dyes, and placed them on the soil surface in a semi-arid woodland near Cobar, NSW, where we’d dug pits similar to those echidnas create. We then simulated a rain event.

Most seeds washed into the pits, and those that started in the pits stayed there. The experiment showed how echidna pits encourage seeds, water and nutrients to meet, giving seeds a better chance to germinate and survive in Australia’s poor soils.

The recovering pits then become plant and soil “hotspots” from which plants can spread across the landscape.

Our research has also found pits also harbour unique microbial communities and soil invertebrates. These probably play an important role in breaking down organic matter to produce soil carbon.

It’s no wonder many human efforts to restore soil imitate the natural structures constructed by animals such as echidnas.

Read more: Curious Kids: How does an echidna breathe when digging through solid earth?

Echidnas As Carbon Farmers

Our recent research also shows how echidna digging helps boost carbon in depleted soils.

When organic matter lies on the soil surface, it’s broken down by intense ultraviolet light which releases carbon and nitrogen into the atmosphere. But when echidnas forage, the material is buried in the soil. There it is exposed to microbes, which break down the material and release carbon and nitrogen to the soil.

This does not happen immediately. Our research suggests it takes 16-18 months for carbon levels in the pits to exceed that in bare soils.

This entire process of echidna digging, capture and buildup creates a patchwork of litter, carbon, nutrients, and plant hotspots. These fertile islands drive healthy, functional ecosystems – and will become more important as the world becomes hotter and drier.

Read more: The secret life of echidnas reveals a world-class digger vital to our ecosystems

Harness The Power Of Echidnas

Soil restoration can be expensive, and impractical across vast areas of land. Soil disturbance by echidnas offers a cost-effective restoration option, and this potential should be harnessed.

Australia’s echidna populations are currently not threatened. But landscape management is needed to ensure healthy echidna populations into the future.

Echidnas often shelter in hollow logs, so removing fallen timber reduces their habitat and feeding sites. Restrictions on practices such as firewood removal are needed to prevent habitat loss.

And being slow-moving, echidnas are often killed on our roads. To address this, shrubs and ground plants should be planted between patches of native bush, creating vegetation corridors so echidnas can move safely from one spot to the next.

And while an echidna’s sharp spines give it some protection from natural predators, they’re less effective against introduced predators such as foxes and cats. So strategies to control these threats are also needed.

The health of Australia’s fragile environment is in serious decline. Echidnas are already providing a valuable ecosystem service – and they should be protected and nurtured to ensure this continues.

David John Eldridge, Professor of Dryland Ecology, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

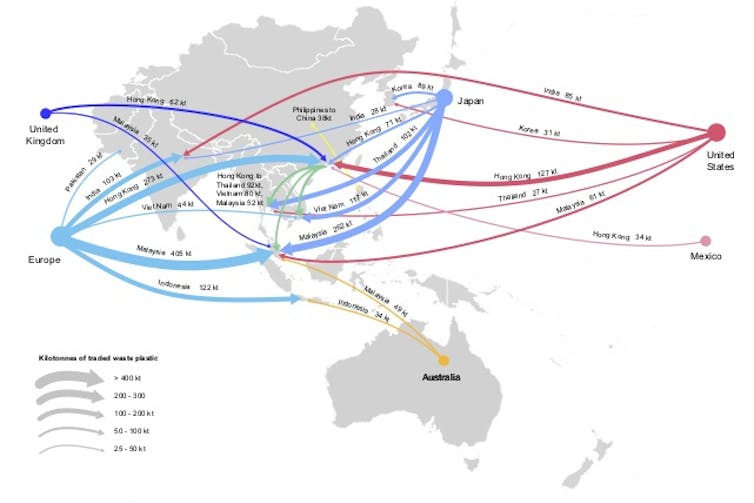

Think all your plastic is being recycled? New research shows it can end up in the ocean

We all know it’s wrong to toss your rubbish into the ocean or another natural place. But it might surprise you to learn some plastic waste ends up in the environment, even when we thought it was being recycled.

Our study, published today, investigated how the global plastic waste trade contributes to marine pollution.

We found plastic waste most commonly leaks into the environment at the country to which it’s shipped. Plastics which are of low value to recyclers, such as lids and polystyrene foam containers, are most likely to end up polluting the environment.

The export of unsorted plastic waste from Australia is being phased out – and this will help address the problem. But there’s a long way to go before our plastic is recycled in a way that does not harm nature.

Know Your Plastics

Plastic waste collected for recycling is often sold for reprocessing in Asia. There, the plastics are sorted, washed, chopped, melted and turned into flakes or pellets. These can be sold to manufacturers to create new products.

The global recycled plastics market is dominated by two major plastic types:

polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which in 2017 comprised 55% of the recyclable plastics market. It’s used in beverage bottles and takeaway food containers and features a “1” on the packaging

high-density polyethylene (HDPE), which comprises about 33% of the recyclable plastics market. HDPE is used to create pipes and packaging such as milk and shampoo bottles, and is identified by a “2”.

The next two most commonly traded types of plastics, each with 4% of the market, are:

polypropylene or “5”, used in containers for yoghurt and spreads

low-density polyethylene known as “4”, used in clear plastic films on packaging.

The remaining plastic types comprise polyvinyl chloride (3), polystyrene (6), other mixed plastics (7), unmarked plastics and “composites”. Composite plastic packaging is made from several materials not easily separated, such as long-life milk containers with layers of foil, plastic and paper.

This final group of plastics is not generally sought after as a raw material in manufacturing, so has little value to recyclers.

Read more: China's recycling 'ban' throws Australia into a very messy waste crisis

Shifting Plastic Tides

China banned the import of plastic waste in January 2018 to prevent the receipt of low-value plastics and to stimulate the domestic recycling industry.

Following the bans, the global plastic waste trade shifted towards Southeast Asian nations such as Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The largest exporters of waste plastics in 2019 were Europe, Japan and the US. Australia exported plastics primarily to Malaysia and Indonesia.

Australia’s waste export ban recently became law. From July this year, only plastics sorted into single resin types can be exported; mixed plastic bales cannot. From July next year, plastics must be sorted, cleaned and turned into flakes or pellets to be exported.

This may help address the problem of recyclables becoming marine pollution. But it will require a significant expansion of Australian plastic reprocessing capacity.

What We Found

Our study was funded by the federal Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. It involved interviews with trade experts, consultants, academics, NGOs and recyclers (in Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand) and an extensive review of existing research.

We found when it comes to the international plastic trade, plastics most often leak into the environment at the destination country, rather than at the country of origin or in transit. Low-value or “residual” plastics – those left over after more valuable plastic is recovered for recycling – are most likely to end up as pollution. So how does this happen?

In Southeast Asia, often only registered recyclers are allowed to import plastic waste. But due to high volumes, registered recyclers typically on-sell plastic bales to informal processors.

Interviewees said when plastic types were considered low value, informal processors frequently dumped them at uncontrolled landfills or into waterways. Sometimes the waste is burned.

Plastics stockpiled outdoors can be blown into the environment, including the ocean. Burning the plastic releases toxic smoke, causing harm to human health and the environment.

Interviewees also said when informal processing facilities wash plastics, small pieces end up in wastewater, which is discharged directly into waterways, and ultimately, the ocean.

However, interviewees from Southeast Asia said their own domestic waste management was a greater source of ocean pollution.

A Market Failure

The price of many recycled plastics has crashed in recent years due to oversupply, import restrictions and falling oil prices, (amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic). However clean bales of PET and HDPE are still in demand.

In Australia, material recovery facilities currently sort PET and HDPE into separate bales. But small contaminants of other materials (such as caps and plastic labels) remain, making it harder to recycle into high quality new products.

Before the price of many recycled plastics dropped, Australia baled and traded all other resin types together as “mixed plastics”. But the price for mixed plastics has fallen to zero and they’re now largely stockpiled or landfilled in Australia.

Several Australian facilities are, however, investing in technology to sort polypropylene so it can be recovered for recycling.

Doing Plastics Differently

Exporting countries can help reduce the flow of plastics to the ocean by better managing trade practices. This might include:

improving collection and sorting in export countries

checking destination processing and monitoring

checking plastic shipments at export and import

improving accountability for shipments.

But this won’t be enough. The complexities involved in the global recycling trade mean we must rethink packaging design. That means using fewer low-value plastic and composites, or better yet, replacing single-use plastic packaging with reusable options.

The authors would like to acknowledge research contributions from Asia Pacific Waste Consultants (APWC) - Dr Amardeep Wander, Jack Whelan and Anne Prince, as well as Phil Manners at CIE.

Read more: Here's what happens to our plastic recycling when it goes offshore ![]()

Monique Retamal, Research Principal, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney; Elsa Dominish, Senior Research Consultant, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney; Nick Florin, Research Director, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, and Rachael Wakefield-Rann, Research Consultant, Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Final Report Calls For Fundamental And Systemic Aged Care Reform

- A new Aged Care Act that puts older people first, enshrining their rights and providing a universal entitlement for high quality and safe care based on assessed need.

- An integrated system for the long-term support and care of older people and their ongoing community engagement.

- A System Governor to provide leadership and oversight and shape the system.

- An Inspector-General of Aged Care to identify and investigate systemic issues and to publish reports of its findings.

- A plan to deliver, measure and report on high quality aged care, including independent standard-setting, a general duty on aged care providers to ensure quality and safe care, and a comprehensive approach to quality measurement, reporting and star ratings.

- Up to date and readily accessible information about care options and services, and care finders to support older people to navigate the aged care system.

- A new aged care program that is responsive to individual circumstances and provides an intuitive care structure, including social supports, respite care, assistive technology and home modification, care at home and residential care. In particular, the new program will provide greater access to care at home, including clearing the home care waiting list.

- A more restorative and preventative approach to care, with increased access to allied health care in both home and residential aged care.

- Increased support for development of ‘small household’ models of accommodation.

- An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander aged care pathway to provide culturally safe and flexible aged care to meet the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people wherever they live.

- Improved access to health care for older people, including a new primary care model, access to multidisciplinary outreach services and a Senior Dental Benefits Scheme.

- Equity of access to services for older people with disability and measures to ensure younger people do not enter or remain in residential aged care.

- Professionalising the aged care workforce through changes to education, training, wages, labour conditions and career progression.

- Registration of personal care workers.

- A minimum quality and safety standard for staff time in residential aged care, including an appropriate skills mix and daily minimum staff time for registered nurses, enrolled nurses and personal care workers for each resident, and at least one registered nurse on site at all times.

- Strengthened provider governance arrangements to ensure independence, accountability and transparency.

- A strengthened quality regulator.

- Funding to meet the actual cost of high quality care and an independent Pricing Authority to determine the costs of delivering it.

- A simpler and fairer approach to personal contributions and means testing, including removal of co-contributions toward care, reducing the high effective marginal tax rates that apply to many people receiving residential aged care, and phasing out Refundable Accommodation Deposits.

- Financing arrangements drawing on a new aged care levy to deliver appropriate funding on a sustainable basis.

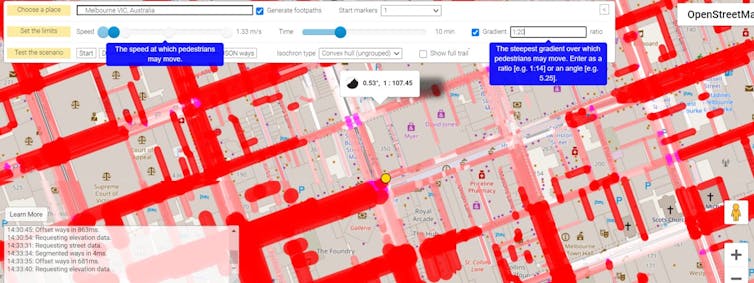

This is how we create the age-friendly smart city

Senior citizens need help and encouragement to remain active as they age in their own communities. Given the choice, that’s what most would prefer. The smart city can provide the digital infrastructure for them to find and tailor the local neighbourhood information they need to achieve this.

Australia has a growing population of older adults, the majority living in cities. The challenge, then, is to ensure city environments meet their needs and personal goals.

Our research shows senior citizens want to pursue active ageing as a positive experience. This depends on them being able to stay healthy, participate in their community and feel secure.

Read more: 'Ageing in neighbourhood': what seniors want instead of retirement villages and how to achieve it

Most city planning efforts to encourage active ageing are siloed and fragmented. Older people are too often shut away in retirement villages or nursing homes rather than living in the community. Current approaches are often based on traditional deficit models of focusing on older people’s declining health.

Another issue is that senior citizens are treated as receivers of solutions instead of creators. To achieve real benefits it’s essential to involve them in developing the solutions.

Working Towards Age-Friendly Cities

To counter a rise in urban ageism, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has been promoting age-friendly cities for nearly 15 years. Its age-friendly framework includes these goals:

equity

an accessible physical environment

an inclusive social environment.

Cities and towns around the world, including local councils in Australia, have begun working towards this.

We need to recognise the diverse demands of living in cities, where most seniors live, particularly as we age.

Read more: Retire the retirement village – the wall and what’s behind it is so 2020

Smart city approaches can make urban neighbourhoods more age-friendly. One way technology and better design do this is to improve access to the sort of information older Australians need – on the walkability of neighbourhoods, for example.

Our research has considered three factors in ensuring smart city solutions involve older Australians and work for them.

Replace Ageism With Agency

Government efforts have focused on increasing life expectancy rather than improving quality of life and independence. Ignoring quality of life leads to the perception of an ageing population as a burden to be looked after.

It would be better to bring about changes that improve older people’s health so they can participate in neighbourhood activities. Social interaction is a source of meaning and identity.

Read more: For Australians to have the choice of growing old at home, here is what needs to change

Active participation by older adults using digital devices can give them agency in their lives and reduce the risk of isolation. Bloomberg reports older adults have become empowered using technology to overcome social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Connect To Smart City Data

Cities are about infrastructure. Senior citizens need to have access to information about this infrastructure to be motivated to spend time in their neighbourhood and reduce their risk of isolation.

Growing numbers of active ageing seniors are “connected” every day using mobile phones to interact with smart city services. Many have wearable devices like smart watches that help monitor and manage their health and physical activity.

These personal devices can also be used to better connect older adults to public data about urban environments. For example, imagine an age-friendly smart city “layer” linked to a smart watch, to highlight facilities such as public toilets, water fountains and shaded rest stops along exercise routes.

Access Map Seattle is an example of an age-friendly, interactive, smart city map that shows the steepness of pedestrian footpaths and raised kerbs. The National Public Toilet Map, created by the Australian Department of Health and Ageing, and Barcelona’s smartappcity are among other mobile apps integrating city services and urban plans.

The rise of “urban observatories” has increased the gathering and analysing of complex city-related data. These data make it possible to build a digital city layer.

This information then helps us understand and improve the liveability of neighbourhoods for older adults. The data can be used for more proactive policy and city planning.

Read more: Aged care isn't working, but we can create neighbourhoods to support healthy ageing in place

Include Co-Design In Planning

Co-design processes that involve older adults, giving them agency in smart city planning, lead to greater participation and inclusion.

We need to start asking senior citizens questions like “How would you like to access this data?” and “What would you like the digital layer to tell you?” Their goals and needs must drive the information provided.

It’s not just a matter of deciding what specific data older adults want to get via their devices. They should also be able to contribute directly to the data. For example, using a mobile app they could audit their neighbourhood to identify features that help or hinder walkability.

Read more: Contested spaces: we need to see public space through older eyes too

To create truly age-friendly smart cities, it is important for older people to be co-designers of the digital layer. The co-design includes deciding both the types of data available and how the data can be usefully presented. We also need to understand what mobile apps could use the data.

If we know what information within the digital city layer motivates older adults to participate more actively in their neighbourhoods, we can plan more age-friendly cities.

Through connecting infrastructures and citizen-led approaches, we can achieve social participation and inclusion of citizens regardless of their age and recognising diversity and equity. We will create places where they feel capable and safe across a range of activities. Redesigning age-friendly and smart communities directly and collaboratively with those affected can enable them to achieve the quality of life they desire.![]()

Sonja Pedell, Associate Professor and Director, Future Self and Design Living Lab, Swinburne University of Technology and Ann Borda, Associate Professor, Centre for Digital Transformation of Health, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We all hope for a 'good death'. But many aged-care residents are denied proper end-of-life care

Death is inevitable, and in a civilised society everyone deserves a good one. It would therefore be logical to expect aged-care homes would provide superior end-of-life care. But sadly, palliative care options are often better for those living outside residential aged care than those in it.

More than a quarter of a million older Australians live in residential aged care, but few choose to be there, few consider it their “home”, and most will die there after living there for an average 2.6 years. These are vulnerable older people who have been placed in residential aged care when they can no longer be cared for at home.

The royal commission has made a forceful and sustained criticism of the quality of aged care. Its final report, released this week, and the interim report last year variously described the sector as “cruel”, “uncaring”, “harmful”, “woefully inadequate” and in need of major reform.

Quality end-of-life care, including access to specialist palliative care, is a significant part of the inadequacy highlighted by the report’s damning findings. This ranked alongside dementia, challenging behaviours and mental health as the most crucial issues facing the sector.

Longstanding Problem

In truth, we have already known about the palliative care problem for years. In 2017 the Productivity Commission reported that end-of-life care in residential aged care needs to be better resourced and delivered by skilled staff, to match the quality of care available to other Australians.

This inequality and evident discrimination against aged-care residents is all the more disappointing when we consider these residents are among those Australians most likely to find themselves in need of quality end-of-life care.

The royal commission’s final report acknowledges these inadequacies and addresses them in 12 of its 148 recommendations. Among them are recommendations to:

enshrine the right of older people to access equitable palliative and end-of-life care

include palliative care as one of a range of integrated supports available to residents

introduce multidiscpliniary outreach services including palliative care from local hospitals

require specific training for all direct care staff in palliative and end-of-life care skills.

What Is Good Palliative Care?

Palliative care is provided to someone with an active, progressive, advanced disease, who has little or no prospect of cure and who is expected to die. Its primary goal is to optimise the quality of life for that person and their family.

End-of-life care is provided by palliative care services in the final few weeks of life, in which a patient with a life-limiting illness is rapidly approaching death. This also extends to bereavement care for family and loved ones.

Unlike in other sectors of Australian society, where palliative care services are growing in line with overall population ageing, palliative care services in residential aged care have been declining.

Funding restrictions in Australian aged-care homes means palliative care is typically only recommended to residents during the final few weeks or even days of their life.

Read more: What is palliative care? A patient's journey through the system

Some 70% of Australians say they would prefer to die at home, surrounded by loved ones, with symptoms managed and comfort the only goal. So if residential aged care is truly a resident’s home, then extensive palliative and end-of-life care should be available, and not limited just to the very end.

Fortunately, the royal commission has heard the clarion call for attention to ensuring older Australians have as good a death as possible, as shown by the fact that a full dozen of the recommendations reflect the need for quality end-of-life care.

Moreover, the very first recommendation — which calls for a new Aged Care Act — will hopefully spur the drafting of legislation that endorses high-quality palliative care rather than maintaining the taboo around explicitly mentioning death.

Let’s Talk About Death

Of course, without a clear understanding of how close death is, and open conversation, planning for the final months of life cannot even begin. So providing good-quality care also means we need to get better at calculating prognosis and learn better ways to convey this information in a way that leads to being able to make a plan for comfort and support, both for the individual and their loved ones.

Advanced care planning makes a significant difference in the quality of end-of-life care by understanding and supporting individual choices through open conversation. This gives the individual the care they want, and lessens the emotional toll on family. It is simply the case that failing to plan is planning to fail.

We need to break down the discomfort around telling people they’re dying. The unpredictability of disease progression, particularly in conditions that involve frailty or dementia, makes it hard for health professionals to determine when exactly palliative care will be needed and how to talk about it with different cultural groups.

Read more: Passed away, kicked the bucket, pushing up daisies – the many ways we don't talk about death

These conversations need to be held through the aged-care sector to overcome policy and regulation issues, funding shortfalls and workforce knowledge and expertise.

We need a broader vision for how we care for vulnerable Australians coming to the end of a long life. It is not just an issue for health professionals and residential care providers, but for the whole of society. Hopefully the royal commission’s recommendations will breathe life into end-of-life care into aged care in Australia.![]()

Davina Porock, Professor of Nursing, Director of Centre for Research in Aged Care, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Respect, Care And Dignity – Aged Care Royal Commission $452 Million Immediate Response As Government Commits To Historic Reform To Deliver Respect And Care For Senior Australians

50% of Australians are prepared to pay more tax to improve aged care workers' pay, survey shows

The final report from the aged care royal commission this week was damning. Speaking of a system in crisis, it calls for an urgent overhaul.

The Morrison government has been facing difficult questions regarding which of the 148 recommendations it will adopt. It also needs to grapple with how to pay for the much-needed changes.

Read more: 4 key takeaways from the aged care royal commission's final report

On this question, the royal commissioners disagree. Commissioner Lynelle Briggs calls for a levy of 1% of taxable personal income, while commissioner Tony Pagone recommends the Productivity Commission investigate an aged care levy.

A 1% levy could cost the median person who already pays the medicare levy about $610 a year, while boosting funds for the aged care sector by almost $8 billion a year.

So far, the government has played down the idea of new taxes. There is a view this would be hard sell for a Coalition elected, at least in part, to lower taxation.

But as debate continues about how to make the changes we need to aged care (and not just talk about it), our research suggests many Australians support a levy to improve the quality and sustainability of our aged care system.

Our Research

In September 2020, we surveyed over 1,000 Australians aged 18 to 87 years, representative by age, gender and state. We wanted to find out how the pandemic influenced attitudes to health, well-being and caring for others.

Our findings indicated overwhelming public support for aged care reform, to ensure all older Australians are treated with dignity.

Read more: Paid on par with cleaners: the broader issue affecting the quality of aged care

The vast majority of our respondents (86%) either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” Australia needed more skilled and trained aged care workers. On top of this, 80% thought aged care workers should be paid more for the work that they did.

More than 80% also either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that nurses working in aged care should be paid at an equivalent rate to nurses working in the health system. Currently, nurses working in aged care are paid, on average, about 10-15% less.

The Crunch Point

Importantly, 50% of our respondents showed a willingness to pay additional tax to fund better pay and conditions for aged care workers. Of those willing to pay more tax, 70% were willing to pay 1% or more per year.

This finding supports previous larger-scale research we undertook for the royal commission, before the pandemic.

Here we found similar levels of public support for increased income tax contributions to support system-wide improvements. This suggests politicians seem to underestimate the public appetite for improvements to the system, and people’s willingness to contribute to achieve this.

Changing Ideas About Economic ‘Success’

Our survey findings also highlighted a growing recognition among Australians of the importance of a broader range of social and economic goals.

For some time, economists, academics, organisations and peak bodies have been calling for a move away from traditional economic indicators (such as economic growth and expanding gross domestic product) at any cost, towards a broader definition of success.

This would see governments focus on policies that promote a more equal distribution of wealth and well-being, where the fundamentals of community cohesion are highly valued and our natural resources are protected.

We asked our survey respondents to rank the relative importance of seven key areas of public policy in framing Australia’s pathway to recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, including:

- dignity (people have enough to live in comfort, safety and happiness)

- nature and climate (a restored natural world which supports life into the future)

- social connection (a sense of community belonging and institutions that serve the common good)

- fairness (equal opportunity for all Australians and the gap between the richest and the poorest greatly reduced)

- participation (having as much control over your daily life as you would want)

- economic growth (an increase in the amount of goods and services produced in Australia), and

- economic prosperity (full employment and low inflation levels).

The criteria ranked most important by the largest proportion of our survey respondents were dignity (20.1%) and fairness (19.3%).

Traditional economic indicators were not the highest priorities for the Australians we surveyed. Instead, economic growth and prosperity were only ranked as a top priority by 15.3% and 15.2% of our respondents respectively.

This suggests the general public recognises the importance of moving beyond the traditional markers of a successful society.

What Australians Want

Our research shows significant aged care reform is entirely consistent with the current priorities of the Australian public.

The burning question now is whether the Morrison government will step up to the challenge.![]()

Rachel Milte, Matthew Flinders Senior Research Fellow, Flinders University and Julie Ratcliffe, Professor of Health Economics and Mathew Flinders Fellow, Caring Futures Institute, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It's A Girl: Rare Black Rhino Calf Born In Dubbo

Taronga Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo is celebrating the birth of a critically endangered Black Rhino calf, born in the early hours of the morning on Wednesday February 24th 2021.

Keepers arrived at work on Wednesday to find the female calf standing beside mother Bakhita in the Zoo’s behind-the-scenes calving yard. Taronga made the announcement on Monday, March 1st, 2021.

“This is the fourth calf for experienced mother Bakhita, who is the Zoo’s most successful Black Rhino breeding female and also the first female Black Rhino born here,” said Taronga Western Plains Zoo Director, Steve Hinks.

Keepers are currently monitoring Bakhita and her calf via CCTV cameras to allow them plenty of space to develop their bond and ensure both mother and calf remain calm.