Inbox and Environment News: Issue 493

May 9 - 15, 2021: Issue 493

Osprey Nest At Palm Beach

Another Local Tawny Frogmouth Road Death: Bird Strike Project

Tuesday May 4, 2021

A resident of Elanora tried to save a Tawny Frogmouth that had been hit by a car and left on the road earlier this week. The bird, with differing size in pupils, indicating head trauma with associated neurological issues, also had a badly broken wing and unfortunately had to be euthanised after the gentleman who found it, cycling, took it to a local vet.

The loss is a reminder that with increased housing targets, poor transport options and more people driving cars on these roads, our local wildlife is at risk if commuters continue to speed in these areas. If you want to keep seeing these other residents the message is - slow down in these poorly lit road channels, particularly along Powder Works road which seems to be claiming more wildlife than other thoroughfares at present.

Owls and nightjars frequent roads to hunt easily obtainable rodents that feed next to the road. Also busy roads fragmenting owl habitat can be also a mortality factor, especially for juveniles either searching for an easy prey, or dispersing from a nesting site.

Nocturnal bird habitat is increasingly at risk from rapidly expanding urbanisation and development pressure. Deforestation and habitat fragmentation continues to escalate in both urban and rural areas in Australia, with only 16% of Australia now forested and the 2019/2020 bushfires have significantly impacted the distribution of many of our nocturnal birds. In urban areas, large hollow-bearing trees, which are used annually by most nocturnal birds to nest, are often removed for safety and to reduce risk to infrastructure. For many nocturnal birds these old, hollow-bearing trees take several hundred years to develop and are now critical habitat in urban environments - further, there is fierce competition from native and introduced animals for the remaining hollows. Whilst retaining hollow-bearing trees is essential for many owl species, understorey vegetation is important for many other night birds. Grass owls nest on the ground in open grassy areas under tussocks or sedges, whilst Nightjars often nest in scrapes on the ground amongst leaf litter.

The urban environment does impact nocturnal species differently. Some, such as the Powerful Owl seem to be more common in our cities now. These owls can do well in forested urban green spaces due to a ready source of prey (e.g. possums, birds and fruit bats), however increasing rates of development pressure are threatening key habitat features like tree hollows and roosts and collisions with cars and windows are significantly impacting the population of many nocturnal species. If we wish to keep owls and other nocturnal birds in our urban neighbourhoods, targeted management practices that work to retain or rebuild key habitat features and mitigate threats are essential.

Owls can be killed by ingesting poisoned rodents. Insectivorous nocturnal birds, such as Frogmouths and Nightjars are also highly susceptible to secondary poisoning, particularly from termiticides. To avoid secondary poisoning pest control needs to use poisons that have no secondary transfer, and that are single dose rather than multi dose.

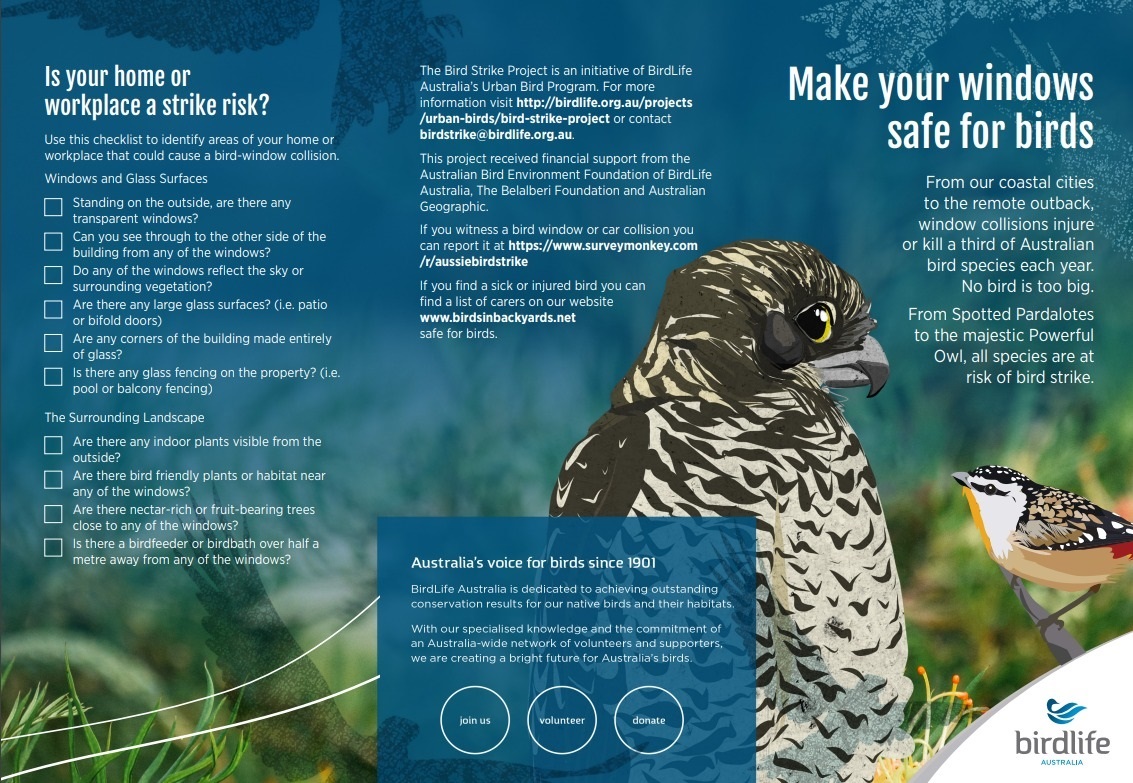

Bird Strike Project: BirdLife Australia

Up to one billion birds strike glass in North America each year, and millions more hit windows each year around the globe. This is an enormous and heart-breaking number - although we don't know much about bird strike in Australia, the loss of birds through car strikes and glass strikes is happening here on a daily basis. With your help, BirdLife Australia can learn more about where and why it's happening, and work together to prevent one of the highest causes of bird injury and mortality.

The Bird Strike Project aims to provide a single management point for our partners in data collection, solutions, and eventually go beyond simple solutions and work across industry to get bird-friendly technology into buildings and other infrastructure. Bird strike has also been assessed as a major threat to Australia’s urban bird communities by a panel of experts during stakeholder workshops for BirdLife Australia’s Urban Bird Conservation Action Plan (UBCAP).

How can you get involved?

You can report any bird window/car strikes using our online survey at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/aussiebirdstrike

What do we know about window strike?

- Migratory species are some of the most vulnerable to window collisions

- Collisions are more frequent during autumn migrations and spring breeding seasons

- Species who exhibit fast, agile and direct flying patterns are more susceptible to window collisions

- Flocking species are less likely to collide with windows

- Large areas of transparent or reflective glass increased the risk of window collisions

- Windows that reflect sky or vegetation may appear as an available flight path or habitat and can cause a bird to collide with a window

- Individual buildings can have their own unique set of characteristics that influence the risk of window collisions

- Collisions are more of a risk in older neighbourhoods with complex vegetation

- Landscaping features such as birdbaths, birdfeeders, resource-rich trees and water features bring birds closer to windows and increase the risk of a collision.

- Low-rise buildings close to urban greenspaces are hotspots for window collisions

- Suburban and rural areas have a higher collision risk

How can you make your windows safe for birds?

Download our brochure below to undertake the strike risk checklist and read about ways to strike proof your home and office

.jpg?timestamp=1620168775147)

What should you do if you find an injured bird?

Please see our FAQ on sick or injured birds, including contacts for wildlife rescue groups around the country or download a pdf:

PDF - What should you do if you find a sick or injured bird?

Tawny Frogmouth, NSW - photo by JJ Harrison

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association's (PNHA) Pittwater Nature #5

now on our website: http://pnha.org.au/.../2021/04/Issue-5-Pittwater-Nature.pdf

What's inside: Trad (Wandering Jew) biocontrol smut is becoming established in Trad in Ingleside Chase Reserve, where it was released last October. Gary rears a Common Crow butterfly from an egg, Lynleigh Greig tells us what happens to native animals taken into care, young Powerful Owl in Katandra Reserve, the secret to Bill Nicholson's longevity, Plateau Park and the Cryptostylis orchid wasp, and lots more. Let us know what you think about Pittwater Nature.

Common Crow Butterfly Euploea core. Photo: Gary Harris

Newport Community Garden Autumn Harvest

North Turimetta

photo by Joe Mills

Locally Extinct Fish Return To Macquarie River After 70 Years

May 4, 2021

More than 70 years after the species were last recorded in the catchment, 7,500 juvenile Macquarie Perch have been released back into the Macquarie River catchment at Winburndale Dam, Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall announced today.

Mr Marshall said the Macquarie Perch species had been named after the very river near Bathurst it had been released back into.

“After a 70-year hiatus from the local waterway, it is very special to see more than 7,500 of these Macquarie Perch return home,” Mr Marshall said.

“We are very excited to be reintroducing this species here after they were bred at the NSW Government’s flagship fish hatchery at Narrandera.

“It is our hope these fingerlings will grow up to establish a new population here and once again become abundant in the Macquarie River catchment from which they derive their name.

“We have seen some of the most challenging conditions for native fish over the last few years, with drought and then bushfire runoff causing considerable harm to local populations, so restocking initiatives like this are vital in supporting their recovery.”

Member for Bathurst Paul Toole hailed the release a significant moment for the local community.

“While it is always fantastic to see fish returned to our local waterways, this is an extra special release of more than 7,500 Macquarie Perch,” Mr Toole said.

“They were last recorded in this catchment more than 70 years ago, and I know our region’s passionate fishos will welcome their return.

“Conditions are now ideal for these fish to flourish in and it’s expected their populations will be able to thrive over the coming years.”

Mr Marshall said the project was funded under the Government’s $10 million 2019/20 NSW Native Fish Rescue Program.

“Our native fish species and our aquatic environment are precious resources that we must protect for future generations,” Mr Marshall said.

“That’s why the Government launched this large-scale effort to create a ‘Noah’s Ark’ program to conserve native fish after the devastating drought.

“This stocking is one of many across the state this season that has seen us deliver on our promise to do everything we can to keep these species healthy and sustainable well into the future.”

(L-R) Stewart Fielder, Dean Gilligan and Abagail Elizur releasing Macquarie Perch into the Macquarie River catchment. Image courtesy NSW DPI

Waste Levy Exemption Extended For Waste Facilities Transitioning To Organics

May 3, 2021

The waste levy exemption on mixed waste organic outputs has been extended for four Alternative Waste Treatment facilities that are transitioning to other sustainable resource recovery methods using organics waste.

Mixed waste organic outputs (also known as MWOO) are the end-product of a practice which aims to separate the organic waste in household red-lid bins from other waste for re-use, rather than sending it to landfill.

The levy exemption extension has been approved for a further 12 months for mixed waste organic outputs produced at the following four licensed waste facilities:

- Suez Kemps Creek facility

- Suez Port Stephens facility at Raymond Terrace

- Veolia facility at Tarago, and

- Eastern Creek Operations facility.

Environment Protection Authority (EPA) CEO Tracy Mackey said the extension will waive the waste levy on mixed waste organic outputs processed at the sites during their transition away from the material and moving to organics recycling, until 1 May 2022.

“A waste levy exemption for mixed waste organic outputs has been in place since October 2018 when the EPA revoked the resource recovery exemption for the application of this material to land, due to risks associated with chemical and physical contaminants, such as glass and plastics,” Ms Mackey said.

“This additional 12-month extension was based on these sites being able to demonstrate that they are transitioning to more sustainable resource recovery outcomes. It is great to see these four operators are adopting new practices.

“To help affected local councils and industry operators adopt more sustainable management measures for their organic waste, following the ban, the NSW Government announced a $24 million alternative waste treatment transition package in March 2020.”

The exemption for the Biomass Solutions facility in Coffs Harbour has not been extended meaning the waste levy will apply to mixed waste organic material processed at the facility.

“Unlike the other facilities that have been approved for the purposes of the MWOO levy exemption, Biomass has not demonstrated sufficient progress or intent to transition to more sustainable resource recovery outcomes, which are necessary to achieving a positive long-term environmental outcome,” Ms Mackey said.

More information about mixed waste organic outputs is available on the EPA website here

North Head National Park Uprgrade: Give Your Feedback

The National Parks and Wildlife Service is pleased to release the concept plans for the North Head Scenic Area upgrade.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service is pleased to release the concept plans for the North Head Scenic Area upgrade.- - reconfiguring the car parks to provide more accessible parking spaces and overflow parking.

- · extended landscaped space for visitors to enjoy views across the harbour.

- · installation of pedestrian crossings and a pedestrian path to improve safety, access and circulation.

- · installation of a new bus stop to the east of the Bella Vista Café.

- · improvements to the entry of the Fairfax Walking Track (currently closed).

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Next Forum + May Activities

Avalon Community Garden

Avalon Community Garden’s primary purpose is to foster, encourage and facilitate community gardening in Pittwater on a not-for-profit basis.

The garden was started in 2010 by a group of locals who worked in conjunction with the support of Barrenjoey High School to develop a space that could be used by the local community, to grow

vegetables, herbs, plants and flowers, and practice sustainable gardening techniques to benefit its members and the community overall.

The garden has been very successful and has grown and developed since its inception, in terms of its footprint, infrastructure, variety of produce and diversity of members. The garden welcomes new members all year round. Levels of contribution range from multiple times a week, to once a month. Your contribution is always welcome, and it is acknowledged people will have varying levels of commitment.

We encourage you to join and start enjoying the following benefits associated with community gardening:

They provide benefits for individuals and for the community as a whole. Community gardens provide education on gardening, recycling and sustainable use of natural resources.

They develop community connections and provide a means of engaging youth, children, the elderly and the disabled and otherwise marginalised individuals in mutually enjoyable and rewarding activities, thus helping to develop more functional and resilient communities.

People involved in community gardens say they improve wellbeing by increasing physical activity and reducing stress, providing opportunities to interact meaningfully with new friends, give time for relaxation and reflection as well as an opportunity to improve their interconnectedness with nature.

To get involved take a look around the site, join the Facebook group and come along and visit on a Sunday morning between 10 and 12 at the garden within Barrenjoey High School on Tasman Road, North Avalon.

Bushfire Conference June 2021

NSW Floodplain Harvesting

- Set out the process for determining license entitlements and provide consistency in this process across the state;

- Specify how floodplain harvesting will be measured and monitored and sets out metering requirements for water users;

- Provide an exemption for rainfall runoff into an irrigation tailwater drain in certain locations, during specified times.

New Floodplain Harvesting Regulations Are A ‘Death Warrant’ For The Darling River

Five Projects Set To Accelerate Murray Darling Basin Plan

- Sustainable Diversion Limit offsets in the Lower Murray: Locks 8 & 9 Project

- Yanco Creek Modernisation Project (Modernising Supply Systems for Effluent Creeks Project)

- Murrumbidgee & Murray National Park Project

- Koondrook-Perricoota Flow Enabling Works (part of the Constraints Measures Program)

- Mid-Murray Anabranches Constraints Demonstration Reach (part of the Constraints Measures Program)

Western Slopes Gas Pipeline Demise Welcome; Spells Further Uncertainty For Santos

Dear Committee Members,It has been sometime since I last contacted you - November 2018 in fact. At that time APA advised that it intended to delay lodgement of the EIS for the pipeline project until the application for the Narrabri Gas Project had been determined.The SEARs for the Westerrn Slopes Pipeline Project required the project application and EIS to be lodged with the DPIE by 4 May 2021. APA has advised today that it did not lodge the application and EIS yesterday (Tuesday). I understand APA is now considering its options in relation to the project.I will keep you advised of any developments in respect of the pipeline project.

EDO To Give Evidence At Another Hearing Into EPBC Act Amendment Bills

Fox scents are so potent they can force a building evacuation. Understanding them may save our wildlife

Foxes, like other animals, use scent to communicate and survive. They urinate to leave their mark, depositing a complex mix of chemicals to send messages to other foxes. Research by myself and colleagues has uncovered new information about these scents that could help control fox numbers.

Urine scent marking behaviour has long been known in foxes, but there has not been a recent study of the chemical composition of fox urine.

We found foxes produce a set of chemicals unknown in other animals. Some of these chemicals are also found in flowers or skunk sprays. One is so potent, a tiny leak was enough to force the evacuation of a building we were working in.

The results suggest a highly evolved language of chemical communication underlying foxes’ social structure and behaviour. Our research could help improve these methods and protect vulnerable native wildlife from one of Australia’s worst feral pests.

The Fox Problem

The European red fox was introduced into Australia in the 1870s for recreational hunting, and within 20 years had expanded to pest proportions. The animals are now found in all states and territories except Tasmania.

Foxes hunt and kill native wildlife and have helped drive several species of small mammals and birds to extinction. They also kill livestock, spread weeds and can threaten the health of humans and pets by transmitting disease.

Current fox control methods mainly depend on lethal baits, which can also kill other animals, and trapping and shooting which alone cannot reduce the large fox populations now present.

Knowledge of the chemistry of fox society could help develop new, better methods of population control.

Read more: When introduced species are cute and loveable, culling them is a tricky proposition

Making Sense Of Smell

Mammals, including humans and foxes, smell airborne substances when molecules enter the nose and bind to receptors in the lining of the nasal cavity. The receptors send a signal to the brain’s olfactory cortex, leading to the sensation of smell.

Foxes have an acute sense of smell. They rely on scents to communicate with each other, find food, avoid predators and locate breeding partners. This ability is beneficial for animals active at night when visibility is low, and enables them to avoid dangerous encounters.

Messages can also be deposited as scent marks to be “read” after the marker has departed. This is useful for claiming and defending territory.

Foxes have two glands from which they emit scents. These comprise:

a patch on the tail known as the “violet gland” because of its floral odour

a pair of sacs either side of the anus.

Fox scents are also present in the animal’s urine.

Read more: Invasive predators are eating the world's animals to extinction – and the worst is close to home

On The Scent

My colleagues and I have investigated fox scents in the violet gland. More recently, we also investigated the scent chemicals in fox urine, assisted by hunting groups in Victoria.

We analysed the urine of 15 free-ranging wild foxes living in farmlands and bush in Victoria. Foxes there are routinely culled as feral pests, and the urine was collected by bladder puncture soon after death.

Among our key findings were a group of 16 sulfur-containing chemicals which, taken together, are unique to foxes. Some are also found in skunk defensive sprays.

Fox scents are mostly very potent, and have been described as unpleasant and “musty”. They are also persistent – if you get fox scent on your skin it’s very hard to wash off.

One incident demonstrates the smelliness of these chemicals. We’d purchased two drops of a compound to compare against our own samples. Unfortunately, the container leaked and the resulting bad odour, while not dangerous, led to our university building being evacuated.

In contrast, another group of chemicals in fox scents are normally found in flowers. These were present in fox urine but more abundant in the tail gland. They are derivatives of carotenoids, the red and yellow pigments in fruits and flowers.

Foxes eat a lot of plants. The presence of plant-derived scents may signal good nutrition, and research suggests dietary carotenoids are particularly important for the general health of mammals.

Read more: Killing cats, rats and foxes is no silver bullet for saving wildlife

Chemical Communicators

The chemistry of fox scents is rich and unique. This suggests foxes have evolved a complex language of chemical communication.

Just as modern drug therapies are based on knowledge of the human body’s internal chemical signalling, an understanding of chemical communication between foxes could lead to novel methods of fox management.

For example, scents signifying a dominant fox could be used to deter subordinate foxes. Conversely, scents that attract foxes could be used to overcome bait shyness.

This could be combined with the non-lethal baiting agent cabergoline, which inhibits the fertility of vixens. And mating could be disrupted if mate choice is found to be determined by chemical signals.

Such new methods may lead to longer-term and more effective control of fox numbers, bringing huge benefits to agriculture and biodiversity in Australia.

The author would like to acknowledge advice on this article from Dr Duncan Sutherland of Phillip Island Nature Parks, Victoria, and the generous assistance of Victorian fox hunting groups which helped collect urine samples.![]()

Stuart McLean, Professor Emeritus, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The 1.5℃ global warming limit is not impossible – but without political action it soon will be

Limiting global warming to 1.5℃ this century is a central goal of the Paris Agreement. In recent months, climate experts and others, including in Australia, have suggested the target is now impossible.

Whether Earth can stay within 1.5℃ warming involves two distinct questions. First, is it physically, technically and economically feasible, considering the physics of the Earth system and possible rates of societal change? Science indicates the answer is “yes” – although it will be very difficult and the best opportunities for success lie in the past.

The second question is whether governments will take sufficient action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This answer depends on the ambition of governments, and the effectiveness of campaigning by non-government organisations and others.

So scientifically speaking, humanity can still limit global warming to 1.5°C this century. But political action will determine whether it actually does. Conflating the two questions amounts to misplaced punditry, and is dangerous.

1.5℃ Wasn’t Plucked From Thin Air

The Paris Agreement was adopted by 195 countries in 2015. The inclusion of the 1.5℃ warming limit came after a long push by vulnerable, small-island and least developed countries for whom reaching that goal is their best chance for survival. The were backed by other climate-vulnerable nations and a coalition of high-ambition countries.

The 1.5℃ limit wasn’t plucked from thin air – it was informed by the best available science. Between 2013 and 2015, an extensive United Nations review process determined that limiting warming to 2℃ this century cannot avoid dangerous climate change.

Since Paris, the science on 1.5℃ has expanded rapidly. An Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 2018 synthesised hundreds of studies and found rapidly escalating risks in global warming between 1.5℃ and 2℃.

The landmark report also changed the climate risk narrative away from a somewhat unimaginable hothouse world in 2100, to a very real threat within most of our lifetimes – one which climate action now could help avoid.

The message was not lost on a world experiencing ever more climate impacts firsthand. It galvanised an unprecedented global youth and activist movement demanding action compatible with the 1.5℃ limit.

The near-term benefits of stringent emissions reduction are becoming ever clearer. It can significantly reduce near-term warming rates and increase the prospects for climate resilient development.

A Matter Of Probabilities

The IPCC looked extensively at emission reductions required to pursue the 1.5℃ limit. It found getting on a 1.5℃ track is feasible but would require halving global emissions by 2030 compared to 2010 and reaching net-zero emissions by mid-century.

It found no published emission reduction pathways giving the world a likely (more than 66%) chance of limiting peak warming this century to 1.5℃. But it identified a range of pathways with about a one-in-two chance of achieving this, with no or limited overshoot.

Having about a one-in-two chance of limiting warming to 1.5℃ is not ideal. But these pathways typically have a greater than 90% chance of limiting warming to well below 2℃, and so are fully compatible with the overall Paris goal.

Don’t Rely On Carbon Budgets

Carbon budgets show the amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted for a given level of global warming. Some point to carbon budgets to argue the 1.5℃ goal is now impossible.

But carbon budget estimates are nuanced, and not a suitable way to conclude a temperature level is no longer possible.

The carbon budget for 1.5℃ depends on several factors, including:

- the likelihood with which warming will be be halted at 1.5℃

- the extent to which non-CO₂ greenhouse emissions such as methane are reduced

- uncertainties in how the climate responds these emissions.

These uncertainties mean strong conclusions cannot be drawn based on single carbon budget estimate. And, at present, carbon budgets and other estimates do not support any argument that limiting warming to 1.5℃ is impossible.

Keeping temperature rises below 1.5℃ cannot be guaranteed, given the history of action to date, but the goal is certainly not impossible. As any doctor embarking on a critical surgery would say about a one-in-two survival chance is certainly no reason not to do their utmost.

Closer Than We’ve Ever Been

It’s important to remember the special role the 1.5℃ goal plays in how governments respond to climate change. Five years on from Paris, and the gains of including that upper ambition in the agreement are showing.

Some 127 countries aim to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century at the latest – something considered unrealistic just a few years ago. If achieved globally and accompanied by stringent near-term reductions, the actions could be in line with 1.5℃.

If all these countries were to deliver on these targets in line with the best-available science on net zero, we may have a one-in-two chance of limiting warming this century to 2.1℃ (but a meagre one-in-ten that it is kept to 1.5°C). Much more work is needed and more countries need to step up. But for the first time, current ambition brings the 1.5℃ limit within striking distance.

The next ten years are crucial, and the focus now must be on governments’ 2030 targets for emissions reduction. If these are not set close enough to a 1.5℃-compatible emissions pathway, it will be increasingly difficult to reach net-zero by 2050.

The United Kingdom and European Union are getting close to this pathway. The United States’ new climate targets are a major step forward, and China is moving in the right direction. Australia is now under heavy scrutiny as it prepares to update its inadequate 2030 target.

The UN wants a 1.5℃ pathway to be the focus at this year’s COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. The stakes could not be higher.

Read more: More reasons for optimism on climate change than we've seen for decades: 2 climate experts explain ![]()

Bill Hare, Director, Climate Analytics, Adjunct Professor, Murdoch University (Perth), Visiting scientist, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research; Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, Research Group Leader, Humboldt University of Berlin; Joeri Rogelj, Director of Research and Lecturer - Grantham Institute Climate Change & the Environment, Imperial College London, and Piers Forster, Professor of Physical Climate Change; Director of the Priestley International Centre for Climate, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Feral desert donkeys are digging wells, giving water to parched wildlife

Erick Lundgren, University of Technology Sydney; Arian Wallach, University of Technology Sydney, and Daniel Ramp, University of Technology SydneyIn the heart of the world’s deserts – some of the most expansive wild places left on Earth – roam herds of feral donkeys and horses. These are the descendants of a once-essential but now-obsolete labour force.

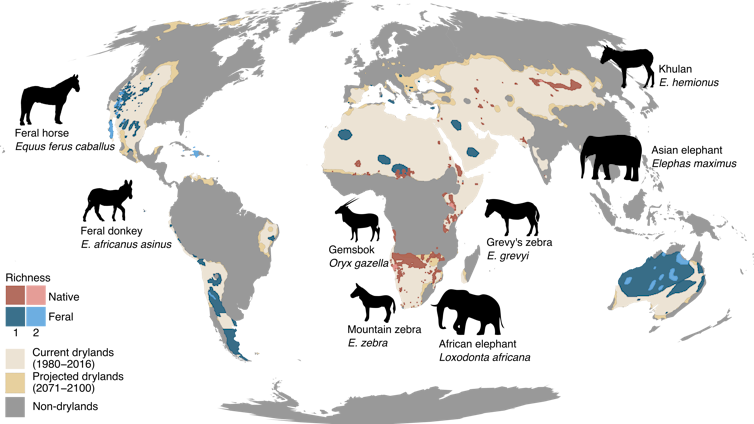

These wild animals are generally considered a threat to the natural environment, and have been the target of mass eradication and lethal control programs in Australia. However, as we show in a new research paper in Science, these animals do something amazing that has long been overlooked: they dig wells — or “ass holes”.

In fact, we found that ass holes in North America — where feral donkeys and horses are widespread — dramatically increased water availability in desert streams, particularly during the height of summer when temperatures reached near 50℃. At some sites, the wells were the only sources of water.

The wells didn’t just provide water for the donkeys and horses, but were also used by more than 57 other species, including numerous birds, other herbivores such as mule deer, and even mountain lions. (The lions are also predators of feral donkeys and horses.)

Incredibly, once the wells dried up some became nurseries for the germination and establishment of wetland trees.

Ass Holes In Australia

Our research didn’t evaluate the impact of donkey-dug wells in arid Australia. But Australia is home to most of the world’s feral donkeys, and it’s likely their wells support wildlife in similar ways.

Across the Kimberley in Western Australia, helicopter pilots regularly saw strings of wells in dry streambeds. However, these all but disappeared as mass shootings since the late 1970s have driven donkeys near local extinction. Only on Kachana Station, where the last of the Kimberley’s feral donkeys are protected, are these wells still to be found.

In Queensland, brumbies (feral horses) have been observed digging wells deeper than their own height to reach groundwater.

Feral horses and donkeys are not alone in this ability to maintain water availability through well digging.

Other equids — including mountain zebras, Grevy’s zebras and the kulan — dig wells. African and Asian elephants dig wells, too. These wells provide resources for other animal species, including the near-threatened argali and the mysterious Gobi desert grizzly bear in Mongolia.

These animals, like most of the world’s remaining megafauna, are threatened by human hunting and habitat loss.

Digging Wells Has Ancient Origins

These declines are the modern continuation of an ancient pattern visible since humans left Africa during the late Pleistocene, beginning around 100,000 years ago. As our ancestors stepped foot on new lands, the largest animals disappeared, most likely from human hunting, with contributions from climate change.

Read more: Giant marsupials once migrated across an Australian Ice Age landscape

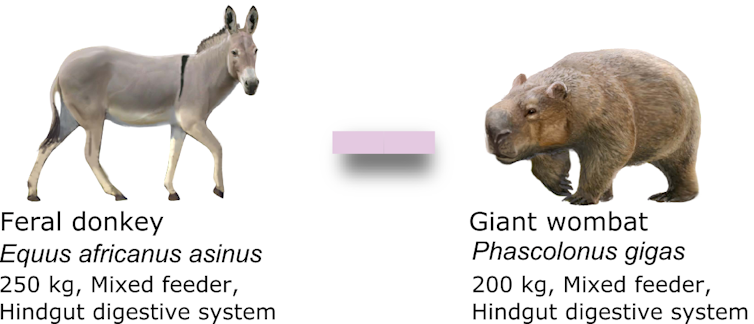

If their modern relatives dig wells, we presume many of these extinct megafauna may have also dug wells. In Australia, for example, a pair of common wombats were recently documented digging a 4m-deep well, which was used by numerous species, such as wallabies, emus, goannas and various birds, during a severe drought. This means ancient giant wombats (Phascolonus gigas) may have dug wells across the arid interior, too.

Likewise, a diversity of equids and elephant-like proboscideans that once roamed other parts of world, may have dug wells like their surviving relatives.

Indeed, these animals have left riddles in the soils of the Earth, such as the preserved remnants of a 13,500-year-old, 2m-deep well in western North America, perhaps dug by a mammoth during an ancient drought, as a 2012 research paper proposes.

Read more: From feral camels to 'cocaine hippos', large animals are rewilding the world

Acting Like Long-Lost Megafauna

Feral equids are resurrecting this ancient way of life. While donkeys and horses were introduced to places like Australia, it’s clear they hold some curious resemblances to some of its great lost beasts.

Our previous research published in PNAS showed introduced megafauna actually make Australia overall more functionally similar to the ancient past, prior to widespread human-caused extinctions.

For example, donkeys and feral horses have trait combinations (including diet, body mass, and digestive systems) that mirror those of the giant wombat. This suggests — in addition to potentially restoring well-digging capacities to arid Australia — they may also influence vegetation in similar ways.

Water is a limited resource, made even scarcer by farming, mining, climate change, and other human activities. With deserts predicted to spread, feral animals may provide unexpected gifts of life in drying lands.

Despite these ecological benefits in desert environments, feral animals have long been denied the care, curiosity and respect native species deservedly receive. Instead, these animals are targeted by culling programs for conservation and the meat industry.

However, there are signs of change. New fields such as compassionate conservation and multispecies justice are expanding conservation’s moral world, and challenging the idea that only native species matter.![]()

Erick Lundgren, PhD Student, Centre for Compassionate Conservation, University of Technology Sydney; Arian Wallach, Lecturer, Centre for Compassionate Conservation, University of Technology Sydney, and Daniel Ramp, Associate Professor and Director, Centre for Compassionate Conservation, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW Government To Strengthen Planning For Natural Hazards: Feedback Wanted

May 3, 2021

New guidelines to help communities and councils plan for natural hazards such as bushfires, drought and floods have been released today for public feedback - until June 8, 2021.

In releasing the draft Strategic Guide to Planning for Natural Hazards in NSW, Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Rob Stokes said the recent flooding which devastated parts of the state emphasised the need to plan strategically for natural hazards.

“Our state is the best place to live in Australia but with its natural beauty comes challenges,” Mr Stokes said.

“In the last few years we’ve experienced some of the worst drought, bushfires and flooding on record so it’s important we continually learn and adapt how we plan for these hazards.

“This draft guide supports the findings of the Bushfire Royal Commission that we need to better address legacy risk in our communities by making sure that strategic land[1]use planning builds resilience to known hazards.”

Minister for Police and Emergency Services David Elliott said NSW has been hit by a series of natural disasters in recent years and the NSW Government is working to reduce the impact and costs of extreme weather events on communities where possible.

“Between 2009 and 2019, NSW was affected by 198 declared natural disasters which resulted in significant losses and cost the State approximately $3.6 billion per year,” Mr Elliott said.

“That’s why we need to future proof our regions rather than reacting to disasters when they occur – prevention and mitigation are critical.”

The draft document comprises eight guiding principles:

- Consider natural hazard risk early

- Protect vulnerable people and assets

- Adopt an all-hazards approach

- Involve the community in conversations about risk

- Plan for emergency response and evacuation

- Be information driven· Plan to rebuild the future, not the present

- Understand the relationship between natural processes and natural hazards

The NSW Government’s flood prone planning package will be finalised shortly.

For more information and to provide feedback on the draft natural hazard guide visit planning.nsw.gov.au/Natural-hazards

Maules Creek Case Discontinued After Minister Finally Acknowledges The Need For Additional Offset Areas

Life’s No Beach For Beach Energy But Limestone Coast Locals Welcome Gas Plant Mothballing

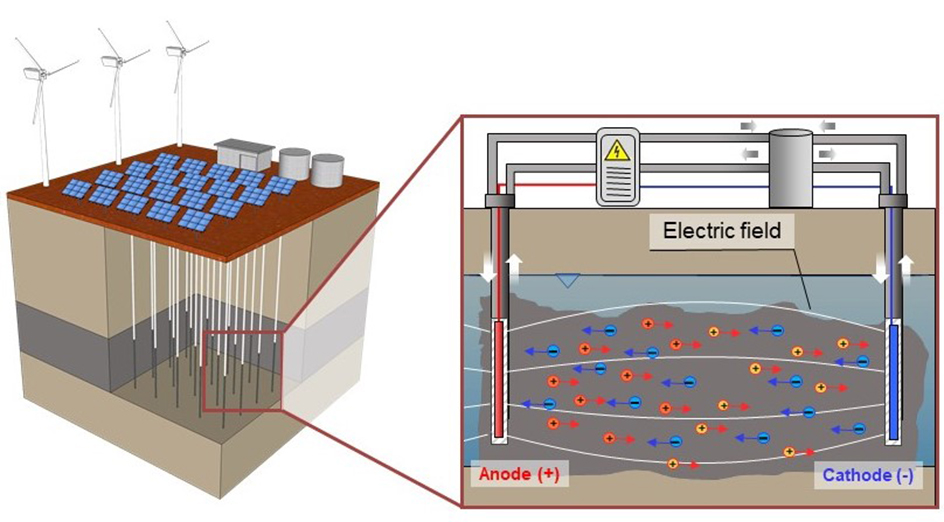

Australia's First Green Hydrogen/Gas Power Plant

May 4, 2021

New South Wales is set to become home to Australia's first dual fuel capable hydrogen/gas power plant following an $83 million funding agreement for the Tallawarra B project in the Illawarra.

Tallawarra B project in the Illawarra. Credit: DPIE

Deputy Premier John Barilaro said the project is vital infrastructure needed to provide dispatchable electricity capacity to replace the Liddell Power Station and create the industries and jobs of the future.

"Delivering enough electricity to power around 150,000 homes at times of peak demand, the project is expected to deliver a $300 million boost to the economy and support about 250 jobs during construction," Mr Barilaro said.

"NSW has an enormous opportunity to lead the world in the production of green hydrogen. Fast-tracking new projects like these will ensure we continue to remain at the forefront of developing new technology while supporting our existing industries."

Treasurer Dominic Perrottet said investing in this cutting-edge technology will help secure power generation and put our State in a prime position to capitalise on an export industry that is predicted to be worth $1.7 billion annually by 2030.

"As we recover from the pandemic, embracing emerging industries will help recharge our economy by creating new jobs and opening up new opportunities that will secure our economic prosperity well into the future," Mr Perrottet said.

"Hydrogen is quickly emerging as a major economic opportunity for our State and this investment will keep us ahead of the curve by positioning New South Wales as a world-leader in hydrogen production."

Minister for Energy Matt Kean said that the Tallawarra B project would help keep the lights on following the closure of the Liddell Power Station in 2023.

"NSW's Energy Security Target is the tightest reliability target in the country and this project will help make sure that we achieve that even after Liddell has closed," Mr Kean said.

"Tallawarra B will provide over 300 megawatts of dispatchable capacity for NSW customers in time for the summer after Liddell retires.

"This project sets a new benchmark for how gas generators can be consistent with NSW's plan to be net zero by 2050 by using green hydrogen and offsetting residual emissions."

Under the funding agreement, Energy Australia will offer to buy enough green hydrogen equivalent to over 5% of the plant's fuel use from 2025 (200,000kg of green hydrogen per year) and will offset direct carbon emissions from the project over its operational life.

EnergyAustralia will also invest in engineering studies on the potential to upgrade Tallawarra B so it can use more green hydrogen in its fuel mix in the future.

The Tallawarra B project is the latest in a series of steps the NSW Government has taken to ensure reliable electricity supply following the closure of Liddell, including:

- jointly underwriting the Queensland-NSW transmission interconnector upgrade with the Australian Government

- the $75 million Emerging Energy Program which provides capital grants for new dispatchable generation

- seeking offers for new dispatchable plant to power the state's schools and hospitals as part of the NSW Government's electricity contract.

Managing Director, Catherine Tanna, said Tallawarra B will be Australia’s first net zero emissions hydrogen and gas capable power plant, with direct carbon emissions from the project offset over its operational life. EnergyAustralia will offer to buy 200,000kg of green hydrogen per year from 2025.

“We thank the New South Wales Government for its support for Tallawarra B. It means the station will be operating in time for the summer of 2023-24, following the closure of the Liddell power station, and it will help to kick start the green hydrogen industry,” said Ms Tanna.

“We are leading the sector by building the first net zero emissions hydrogen and gas capable power plant in New South Wales,” she said.

“What’s particularly exciting is that further engineering studies will see if the amount of green hydrogen can increase, which will further support the Port Kembla Hydrogen Hub.”

Ms Tanna said Tallawarra B will provide New South Wales with improved energy security, reliability and flexibility options.

“Our new open-cycle, hydrogen and gas capable turbine will provide firm capacity on a continuous basis and paves the way for additional cleaner energy sources to enter the system.

“EnergyAustralia has a goal of being carbon neutral by 2050. Today we provide further evidence of another energy project that can help keep the lights on for customers with reliable, affordable, and cleaner energy.”

Green hydrogen is a cheap, reliable type of energy that is made using 100% renewable sources.

NSW Government Failing Citizens By Funding Gas

Paying Australia’s coal-fired power stations to stay open longer is bad for consumers and the planet

Australian governments are busy designing the nation’s transition to a clean energy future. Unfortunately, in a misguided effort to ensure electricity supplies remain affordable and reliable, governments are considering a move that would effectively pay Australia’s old, polluting coal-fired power stations to stay open longer.

The measure is one of several options proposed by the Energy Security Board (ESB), the chief energy advisor to Australian governments on electricity market reform. The board on Friday released a vision to redesign the National Electricity Market as it transitions to clean energy.

The key challenges of the transition are ensuring it is smooth (without blackouts) and affordable, as coal and gas generators close and are replaced by renewable energy.

The redesign has been two years in the making. The ESB has done a very good job of identifying key issues, and most of its recommendations are sound. But its option to change the way electricity generators and retailers strike contracts for electricity, if adopted, would be highly counterproductive – bad both for consumers and for climate action.

The Energy Market Dilemma

The National Electricity Market (NEM) covers every Australian jurisdiction except Western Australia and the Northern Territory. It comprises electricity generators, transmission and distribution networks, electricity retailers, customers and a financial market where electricity is traded.

Electricity generators in the NEM comprise older, polluting technology such as gas- and coal-fired power, and newer, clean forms of generation such as wind and solar. Renewable energy, which makes up about 23% of our electricity mix, is now cheaper than energy from coal and gas.

Wind and solar energy is “variable” – only produced when the sun is shining and the wind is blowing. Technology such as battery storage is needed to smooth out renewable energy supplies and make it “dispatchable”, meaning it can be delivered on demand.

Some say coal generators, which supply dispatchable electricity, are the best way to ensure reliable and affordable electricity. But Australia’s coal-fired power stations, some of which are more than 40 years old, are becoming more prone to breakdowns – and so less reliable and more expensive – as they age. This has led to some closing suddenly.

Without a clear national approach to emissions targets, there’s a risk these sudden closures will occur again.

Read more: Explainer: what is the electricity transmission system, and why does it need fixing?

So What’s Proposed?

To address reliability concerns, the ESB has proposed an option known as the “physical retailer reliability obligation”.

In a nutshell, the change would require electricity retailers to negotiate contracts for a certain amount of “dispatchable” electricity from specific generators for times of the year when reliability is a concern, such as the peak weeks of summer when lots of people use air conditioning.

Currently, the Australian Energy Market Operator has reserve electricity measures it can deploy when market supply falls short.

But under the new obligation, all retailers would also have to enter contracts for dispatchable supply. This would likely require buying electricity from the coal generators that dominate the market. This provides a revenue source enabling these coal plants to remain open even when cheaper renewable energy makes them unprofitable.

The ESB says without the change, the closure of coal generators will be unpredictable or “disorderly”, creating price shocks and reliability risks.

A Big Risk

Even the ESB concedes the recommendation comes with considerable risks. In particular, the board says it may:

- impose increased barriers to retail competition and product innovation

- lead to possible overcompensation of existing coal and gas generators.

In short, the policy could potentially lock in increasingly unreliable, ageing coal assets, stall new investment in new renewable energy storage such as batteries and pumped hydro and increase market concentration.

It could also push up electricity prices. Electricity retailers are likely to pass on the cost of these new electricity contracts to consumers, no matter how much energy that household or business actually used.

The existing market already encourages generators to provide reliable supply – and applies strong penalties if they don’t. And in fact, the NEM experiences reliability issues for an average of just one minute per year. It would appear little could be added to the existing market design to make generators more reliable than they are.

Finally, the market is dominated by three large “gentailers” - AGL, Energy Australia and Origin – which own both generators and the retail companies that sell electricity. The proposed change would disadvantage smaller electricity retailers, which in many cases would be forced to buy electricity from generators owned by their competitors.

Australia’s gentailers are heavily invested in coal power stations. The proposed change would further concentrate their market power while propping up coal.

Read more: 'Failure is not an option': after a lost decade on climate action, the 2020s offer one last chance

What Governments Should Do

If coal-fired power stations are protected from competition, it will deter investment in cleaner alternatives. The recommendation, if adopted, would delay decarbonisation and put Australia further at odds with our international peers on climate policy.

The federal and state governments must work together to develop a plan for electricity that facilitates clean energy investment while controlling costs for consumers.

The plan should be coordinated across the states. Without this, we risk creating a sharper shock later, when climate diplomacy requires the planned retirement of coal plants. Other nations have acknowledged the likely demise of coal, and it’s time Australia caught up.

Daniel J Cass, Research Affiliate, Sydney Business School, University of Sydney; Joel Gilmore, Associate Professor, Griffith University, and Tim Nelson, Associate Professor of Economics, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cayman Islands Sea Turtles Back From The Brink

May 4, 2021

Sea turtles in the Cayman Islands are recovering from the brink of local extinction, new research shows. Monitoring from 1998-2019 shows loggerhead and green turtle nest numbers increased dramatically, though hawksbill turtle nest numbers remain low. In the first counts in 1998-99, just 39 sea turtle nests were found in total on the three islands. By 2019, the figure was 675.

Captive breeding of green turtles and inactivity of a traditional turtle fishery due to tightening of restrictions in 2008 contributed to this -- but populations remain far below historical levels and still face threats including illegal hunting.

The study was carried out by the Cayman Islands Department of Environment and the University of Exeter.

.jpg?timestamp=1620162537659)

A green turtle hatchling (credit Cayman Islands Department of Environment)

"Our findings demonstrate a remarkable recovery for sea turtle populations that were once thought to be locally extinct," said Dr Janice Blumenthal, of the Cayman Islands Department of Environment.

"A combination of factors is thought to have led to this conservation success story.

"It is likely that a captive breeding operation by the Cayman Turtle Farm (now the Cayman Turtle Centre) drove the increase in Grand Cayman's green turtle population in the early years of monitoring.

"For loggerhead turtles, the most important factor was the restrictions placed on the legal turtle fishery in 2008."

Dr Jane Hardwick, also of the Cayman Islands Department of Environment, added: "For both species, the recovery was assisted by protection efforts by the Cayman Islands Department of Environment on nesting beaches, including patrols by conservation officers to reduce illegal hunting.

"However, our study finds that illegal take is an ongoing threat, with a minimum of 24 turtles taken from 2015-19, many of which were nesting females.

"Artificial lighting on nesting beaches, which can direct hatchlings away from the sea, increased over the period of our study.

"Additionally, as highly migratory endangered species, sea turtles are influenced by threats and conservation efforts outside of the Cayman Islands, showing a need for international co-operation in sea turtle management."

Historically, the Cayman Islands had among the world's largest sea turtle nesting populations, with turtles numbering in the millions. By the early 1800s, the populations had collapsed due to human overexploitation.

The new study shows that, despite reaching critically low levels, nesting populations of green and loggerhead turtles have recovered significantly.

Hawksbill turtle nest numbers have not increased in tandem with loggerhead and green turtles -- with a maximum of 13 hawksbill nests recorded in a single monitoring season.

Information on turtle nests is being used by the Cayman Islands authorities to target management efforts.

This includes "turtle-friendly lighting" initiatives, and a greater level of habitat protection for key areas has been proposed under the National Conservation Law of the Cayman Islands.

Professor Brendan Godley, of the University of Exeter, said: "I was fortunate to have been involved in establishing the turtle monitoring programme with the Department of Environment in the Cayman Islands back in 1998 and it is fantastic to see how protection and awareness has resulted in an increase in nesting turtles.

"The wonderful team and leadership of the Department of Environment have been instrumental in driving the monitoring and conservation."

Department of Environment Director Gina Ebanks-Petrie said: "We are extremely grateful to the many volunteers, interns, property owners, businesses, organisations and members of the public who have assisted with sea turtle conservation efforts over the past two decades.

"Sea turtles are a national symbol of the Cayman Islands and our community has come together to demonstrate our commitment to their protection. This research gives us essential information for strategically targeted management efforts to secure future survival of these populations."

Janice M. Blumenthal, Jane L. Hardwick, Timothy J. Austin, Annette C. Broderick, Paul Chin, Lucy Collyer, Gina Ebanks-Petrie, Leah Grant, Lorri D. Lamb, Jeremy Olynik, Lucy C. M. Omeyer, Alejandro Prat-Varela, Brendan J. Godley. Cayman Islands Sea Turtle Nesting Population Increases Over 22 Years of Monitoring. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2021; 8 DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2021.663856

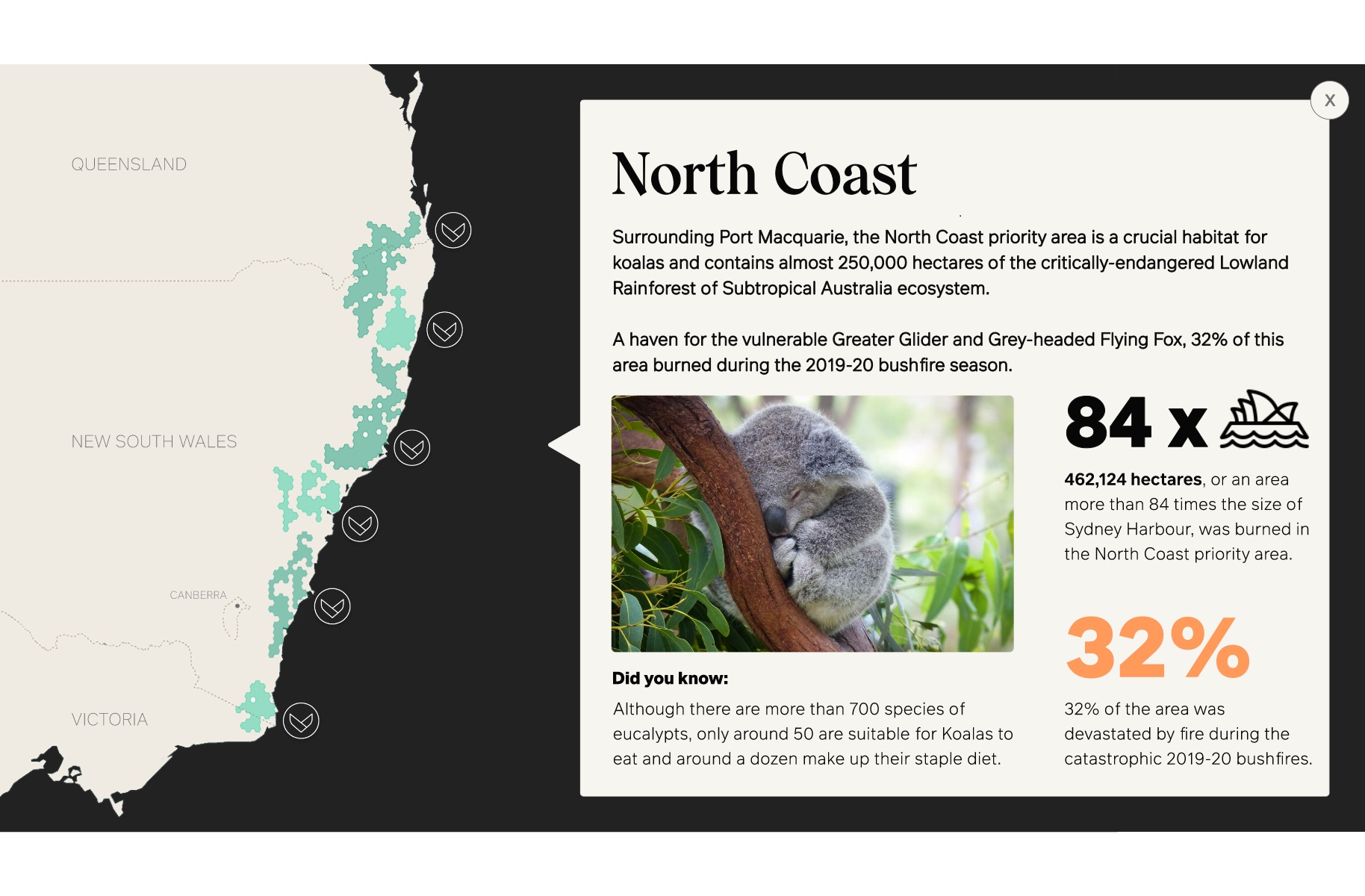

Defending The Unburnt: EDO Launches Landmark Legal Initiative

- 14 million hectares burned. Nearly 3 billion native animals impacted. Entire communities all but destroyed.

- We have a plan to defend what remains.

Hanson Tweed Sand Plant Expansion: Feedback

- a maximum of 950, 000 tonnes of sand extracted annually

- operate 24hours/7 days a week

- quarry life - 30 years

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

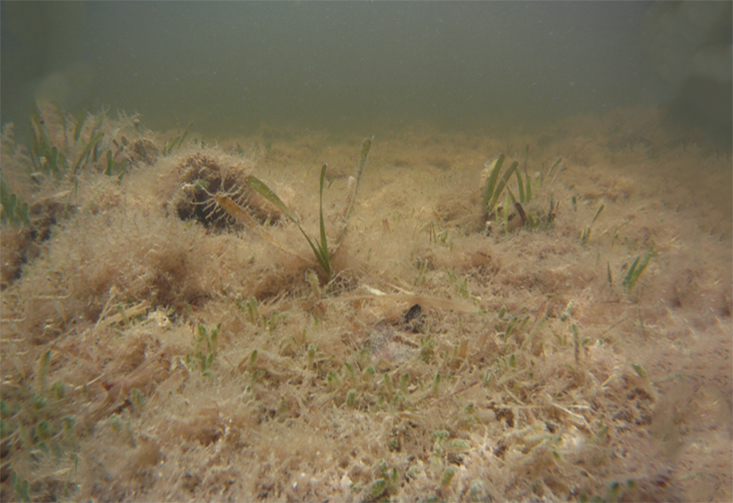

Mangroves And Seagrasses Absorb Microplastics

May 4, 2021

Mangroves and seagrasses grow in many places along the coasts of the world, and these 'blue forests' constitute an important environment for a large number of animals. Here, juvenile fish can hide until they are big enough to take care of themselves; crabs and mussels live on the bottom; and birds come to feed on the plants.

However, the plant-covered coastal zones do not only attract animals but also microplastics, a new study shows.

- The denser the vegetation, the more plastic is captured, says Professor and expert in coastal ecology, Marianne Holmer, from the University of Southern Denmark.

She is concerned about how the accumulated microplastics affect animal and plant life.

- We know from other studies that animals can ingest microplastics and that this may affect their organism.

Animals ingest microplastics with the food they seek in the blue forests. They may suffocate, die of starvation, or the small plastic particles can get stuck different places in the body and do damage.

Another problem with microplastics is that they may be covered with microorganisms, environmental toxins or other health hazardous/disease-promoting substances that are transferred to the animal or plant that absorbs the microplastics.

- When microplastics are concentrated in an ecosystem, the animals are exposed to very high concentrations, Marianne Holmer explains.

She points out that microplastics concentrated in, for example, a seagrass bed are impossible to remove again.

The study is based on examinations of three coastal areas in China, where mangroves, Japanese eelgrass (Z. japonica) and the paddle weed Halophila ovalis grow. All samples taken in blue forests had more microplastics than samples from control sites without vegetation.

The concentrations were up to 17.6 times higher, and they were highest in the mangrove forest. The concentrations were up to 4.1 times higher in the seagrass beds.

Mangrove trees probably capture more microplastics, as the capture of particles is greater in mangrove forests than in seagrass beds.

Researchers also believe that microplastics bind in these ecosystems in the same way as carbon; the particles are captured between leaves and roots, and the microplastics are buried in the seabed.

- Carbon capture binds carbon dioxide in the seabed, and the blue forests are really good at that, but it's worrying if the same thing happens to microplastics, says Marianne Holmer.

Although the study was conducted along Chinese coasts, it may be relevant to similar ecosystems in the rest of the world, including Denmark, where eelgrass beds are widespread.

- It's my expectation that we will also find higher concentrations of microplastics in Danish and global seagrasses, she says.

The study was conducted in collaboration with colleagues from the Zhejiang University in China, among others, and is published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

The blue forests: Lots of plants grow in or below sea level; mangroves, seaweed, seagrass and marsh plants. Especially mangroves and seagrasses absorb and store carbon like plants on land and are thus extremely important for the planet's carbon footprint.

Yuzhou Huang, Xi Xiao, Kokoette Effiong, Caicai Xu, Zhinan Su, Jing Hu, Shaojun Jiao, Marianne Holmer. New Insights into the Microplastic Enrichment in the Blue Carbon Ecosystem: Evidence from Seagrass Meadows and Mangrove Forests in Coastal South China Sea. Environmental Science & Technology, 2021; 55 (8): 4804 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c07289

Open Letter To The Australian Prime Minister Advocating For Climate Action To Protect Australia's Health

Dear Prime Minister,

We write to you as a coalition of climate concerned health organisations in Australia that wish to see the threat to health from climate change addressed by the Australian Government.

Climate change is described by the World Health Organization as “the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century.”

Yet, climate action could be the greatest public health opportunity to prevent premature deaths, address climate and health inequity, slow down or reverse a decrease in life expectancy, and unlock substantial health and economic co-benefits.

To ensure that the health of all Australians is protected from the threat of climate change, we call on the Australian Government to:

1. Prioritise health in the context of Australia’s Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris Agreement

A stable climate is a fundamental determinant of health and the aim to limit warming to 1.5°C is a critically important public health goal. The current emissions reductions target set by Australia is not sufficient to keep warming to 2°C. This threatens the health of Australians, and people around the world. Significantly increasing ambition by Australia in its Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement is needed to have a chance of avoiding the further disastrous health, economic, and environmental impacts of climate change. This would best be achieved by the creation of a body that will appropriately prioritise the setting of targets to meet those agreed to under the Paris Agreement.

2. Commit to the decarbonisation of the healthcare sector by 2040, and to the establishment of an Australian Sustainable Healthcare Unit

The health sector is responsible for 7% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. Achieving net-zero healthcare will significantly contribute to emissions reductions in Australia and will lead to economic and health co-benefits.

A target of net-zero emissions by 2040 for healthcare in Australia, with an interim emissions reduction target of 80% by 2030, is in line with similar commitments by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom - and is broadly consistent with the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C.

Establishing an Australian Sustainable Healthcare Unit in the Australian Government Department of Health is necessary to ensure standardised and consistent measurement of health sector emissions, mapping evidence-based approaches to emissions reductions, and achieving nation-wide health sector outcomes.

3. Implement a National Strategy on Climate, Health and Wellbeing for Australia

A key recommendation from the 2020 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Policy Brief for Australia is the implementation of a national climate change and health strategy. A Framework for a National Strategy on Climate, Health and Wellbeing has already been developed as guidance by the health sector and health experts, and is supported by more than 50 health organisations.

By implementing the systematic and ambitious actions on climate change and health described above, the Australian Government will demonstrate its commitment to the health and wellbeing of Australians, the economy, and the environment. This will deliver a decrease in climate change associated morbidity and mortality and the associated economic costs, and unlock substantial benefits from a healthier and more prosperous society.

Many Australian Frogs Don’t Tolerate Human Impacts On The Environment

May 4, 2021

A UNSW and Australian Museum study using data from a citizen science project finds 70 per cent are vulnerable to housing, agriculture, roads and recreation.

We urgently need to consider human impacts on the environment, say UNSW Sydney and Australian Museum scientists, whose study of 87 Australian frog species found almost three-quarters were intolerant of modified habitats.

The findings, published in the journal Global Change Biology, are particularly concerning as more than 40 of Australia’s 243 frog species are already threatened with extinction.

“Frogs need to be prioritised in urban planning and conservation decisions,” lead author and PhD candidate Gracie Liu from UNSW Science’s School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences says.

“By studying how species respond to human-driven habitat modification, and ranking them based on their tolerance, we can prioritise the most vulnerable species and take appropriate conservation measures to mitigate the risk to biodiversity.”

Frogs are the sign of a healthy environment, but they are one of the most threatened groups of animals on earth. Humans have played a large part in their decline by clearing and modifying native vegetation for housing, agriculture, roads, and recreation. In Australia, cities and agriculture already account for more than half of the country’s land use.

With this in mind, the researchers developed a tolerance index to measure these effects on frogs, accounting for the multiple stressors such as roads, built up areas, farms, mines, and light pollution.

The index was based on over 126,000 frog observations from the Australian Museum’s citizen science project FrogID, which was set up to monitor frog populations and help better understand and conserve Australia’s frog species.

“Thanks to thousands of people across Australia recording frogs on their mobile phones using the FrogID app, we had access to a huge number of frog observations,” study UNSW co-author and lead scientist of FrogID, Dr Jodi Rowley says.

Dr Rowley is also curator of Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Biology at the Australian Museum.

“A dataset of this size grants us the ability to study broad trends in terms of what makes a frog tolerant or intolerant.”

Alarmingly, 70 per cent of frogs studied were intolerant of human modified habitats.

“Frogs that are so called ‘habitat specialists’ are particularly vulnerable to human impacts,” Ms Liu says.

“These frogs, including the Crawling Toadlet (Pseudophryne guentheri) and the Bleating Froglet (Crinia pseudinsignifera), have specific habitat requirements that backyards, gardens and other human modified habitats just can’t provide.

“Frogs that lay their eggs on land are also intolerant of habitat modification due to their strong dependence on forest resources, so there is a clear need to preserve natural habitat.”

But other species, the ‘tolerators’, regularly turn up in people’s backyards and may actually be perfectly content living there, the scientists say.

“Generalists species like the Striped Marsh Frog (Limnodynastes peronii), White-lipped Tree Frog (Litoria infrafrenata) and Motorbike Frog (Litoria moorei) can make use of a variety of resources and environmental conditions and can thrive in human modified habitats,” Ms Liu says.

The findings were optimistic for some frog species, with species that call from vegetation often tolerant of modified habitats.

“This suggests that in addition to preserving native habitat, frog diversity can be supported by creating green spaces and ‘frog-friendly’ gardens in modified areas,” Dr Rowley says.

The scientists say many more species may be hard hit if stronger conservation measures are not taken.

Ms Liu’s next research will explore how habitat modification affects frog breeding seasons, movements and habitat use.

The public is being encouraged to continue the count of Australia's frogs using FrogID so UNSW and Australian Museum scientists can continue to better understand Australia’s frogs, the health of our ecosystems and biodiversity in general.

“We are also using FrogID to understand basic but vital things like how many frog species we have and even discover species currently unknown to science,” Dr Rowley says.

Examples of Australia’s least tolerant frog species

Of all the studied species, the Crawling Toadlet (Pseudophryne guentheri) was the least tolerant of human modified habitats. “This is a small ground-dwelling frog, no more than 4cm in body length, from southwest Western Australia,” Ms Liu says.

The second most intolerant species was the Bleating Froglet (Crinia pseudinsignifera), another small frog, reaching 3cm in body length, from southwest Western Australia. It lives in temporary swamps in granite areas.

The Ticking Frog (Geocrinia leai) from Western Australia’s jarrah forest was also amongst Australia’s least tolerant frogs.

“The males – the sex that makes advertisement calls – live up to their name, wooing females with a continuous ticking call. The females will then lay their eggs in a cluster on land under wet leaf litter, logs, or waterside vegetation,” Dr Rowley says.

There were species that did not have enough data for the scientists to study.

“Most of these were habitat specialists, secretive species, or species that live in very remote parts of Australia – those that are likely to be even more intolerant of habitat modification,” Ms Liu says.

Examples of Australia’s most tolerant frog species

Australia’s most modification tolerant frog was the Striped Marsh Frog (Limnodynastes peronii). Not only does this frog occupy human modified habitats, but the researchers say that it may even prefer them to natural habitats.

“This is a frog that is likely to be familiar to many of those living along Australia’s eastern coastline,” Ms Liu says. “It has a distinctive call that sounds a lot like a dripping tap, or a tennis ball being hit.”

Coming in second was the White-lipped Tree Frog (Litoria infrafrenata), a northern Queensland species and Australia’s largest frog, reaching 13.5cm in body length.

This frog inhabits rainforest and Melaleuca swamps, but it is not unusual for them to appear on farms and in suburban gardens.

Third place went to Western Australia’s Motorbike Frog (Litoria moorei). Its mating call, as the name suggests, resembles the rumble of a motorbike.

“If you had one of these frogs in your backyard, you’d be forgiven for thinking that someone was doing burnouts on a motorbike outside your house,” Ms Liu says.

Momentum Builds For Southern Ocean Protection

April 29, 2021

The creation of a network of protected areas in the Southern Ocean that properly represents and conserves its ecological diversity is a step closer.

Last night a Ministerial Declaration from a high-level meeting hosted by the European Union called for urgent international action “to conserve the Southern Ocean’s unique biodiversity and ecosystems for present and future generations.”

Wandering albatross Photo: Mike Double

15 nations and the European Union met in an online conference on 28 April to affirm their commitment to protecting the Southern Ocean from climate change and other human impacts.

Australia’s Minister for the Environment Sussan Ley was the first speaker in the meeting that included senior representatives from France, Germany, Norway, United Kingdom, Uruguay, Chile, Argentina and the Presidential Envoy for Climate of the United States of America.

The 15 nations, and the European Union, are members of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, known as CCAMLR.

Australia's Commissioner to CCAMLR, Gillian Slocum, said that the meeting built momentum to establish a representative system of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the Southern Ocean.

“The meeting, initiated by the EU, agreed to encourage all 26 members of CCAMLR to engage constructively on MPA proposals currently under consideration.”

“Australia will continue to play a lead role in establishing a representative system of MPAs in the Southern Ocean, including in East Antarctica and the Weddell Sea,” Ms Slocum said.

Antarctic network of marine protected areas

In 2009, CCAMLR established its first MPA, the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf Marine Protected Area, a region covering 94,000 square kilometres in the southern Atlantic Ocean.

In 2016, CCAMLR members agreed to establish a new MPA in the Ross Sea region. Covering 1.55 million square kilometres, the Ross Sea region MPA is the world’s largest. Nearly three-quarters of the area is a 'no-take' zone that forbids all fishing.

Since 2012, Australia, together with the European Union, has advocated for the adoption of an East Antarctic MPA. Norway, the United Kingdom, and Uruguay are now co-proponents of the proposal.

“The East Antarctic MPA would protect distinctive deep-water reefs and feeding areas for marine mammals, penguins and other seabirds,” said Ms Slocum.

It would also provide scientific reference zones to assist with understanding the effects of fishing outside protected areas, and the consequences of climate change for Southern Ocean ecosystems.

Large-scale MPAs are also an important tool to build ocean and ecosystem resilience to impacts of climate change.

Australia is also a co-sponsor of the Weddell Sea MPA, and supports Argentina and Chile in the establishment of an MPA in the Antarctic Peninsula region.

Australian Antarctic science an enabler

Director of the Australian Antarctic Division, Kim Ellis, said that CCAMLR is an excellent example of applying science to deliver evidence-based environmental protection.

“Our science has a direct impact on policy outcomes for a range of management issues in the Southern Ocean, from setting catch limits for krill fisheries to informing the design of Marine Protected Areas.”

“It’s important that CCAMLR’s proposals are based on the best available science, and that’s what the Australian Antarctic Program provides,” Mr Ellis said.

The AAD’s Deputy Chief Scientist, Dr Dirk Welsford, is currently the Chair of CCAMLR’s Scientific Committee.

Emperor penguins dive in search of prey Photo: Lincoln Mainsbridge

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Friday essay: 3 ways philosophy can help us understand love

Love can seem a primal force, an intoxicating mix of desire, care, ecstasy and jealousy hard-wired into our hearts. The polar opposite of philosophy’s measured rationality and theoretical speculations.

Yet if you take any topic in the world, and keeping asking deep questions of it, you will ultimately wind up doing philosophy. Love is no different.

Indeed, many famous philosophers— Kant, Aristotle, De Bouvier — wrote about love and how it fitted into their larger theories of human reason, excellence and freedom.