Inbox and Environment News: Issue 495

May 23 - 29, 2021: Issue 495

Proposal To Allow Dogs Offleash On To Mona Vale Beach And Palm Beach

- completing the comment form(s) here: https://yoursay.northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au/proposed-dog-off-leash-areas

- emailing them at council@northernbeaches.nsw.gov.au

- writing to them marked 'Proposed dog off-leash areas', Northern Beaches Council, PO Box 82 Manly, NSW 1655.

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Mona Vale Dunes Planting Morning

Sydney Wildlife: Registrations For The Next Rescue And Care Course Are Now Open - Commences June 19, 2021

ORRCA News: 2021 Census Day And 2021 Art Comp.

- * Create a cetacean inspired artwork of any description

- * Like the ORRCA FB page and/or Instagram Page

- * Post artwork publicly via your Facebook or Instagram account

- WITH the hashtag #orrcacreatesasplash2021 AND the age

- category they are entering (12 years and under, 13-18 years, 19 years and over)

- * You are able to submit multiple entries

- * Posts needs to be shared publicly so that the ORRCA team can

- see artwork and hashtag

- * All entries must be submitted by 5 June 2021

ORRCA Census Day 2021: Sunday June 27 2021

- This is a FREE event for all to join in.

- From sun up to sun down.

- Record all your sightings from your favourite whale watching location using an ORRCA data sheet and sending it into the team at the end of the day.

- Email orrcacensusday@gmail.com for all the details as they unfold.

Newport Community Garden Autumn Harvest

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Next Forum

Avalon Community Garden

Avalon Community Garden’s primary purpose is to foster, encourage and facilitate community gardening in Pittwater on a not-for-profit basis.

The garden was started in 2010 by a group of locals who worked in conjunction with the support of Barrenjoey High School to develop a space that could be used by the local community, to grow

vegetables, herbs, plants and flowers, and practice sustainable gardening techniques to benefit its members and the community overall.

The garden has been very successful and has grown and developed since its inception, in terms of its footprint, infrastructure, variety of produce and diversity of members. The garden welcomes new members all year round. Levels of contribution range from multiple times a week, to once a month. Your contribution is always welcome, and it is acknowledged people will have varying levels of commitment.

We encourage you to join and start enjoying the following benefits associated with community gardening:

They provide benefits for individuals and for the community as a whole. Community gardens provide education on gardening, recycling and sustainable use of natural resources.

They develop community connections and provide a means of engaging youth, children, the elderly and the disabled and otherwise marginalised individuals in mutually enjoyable and rewarding activities, thus helping to develop more functional and resilient communities.

People involved in community gardens say they improve wellbeing by increasing physical activity and reducing stress, providing opportunities to interact meaningfully with new friends, give time for relaxation and reflection as well as an opportunity to improve their interconnectedness with nature.

To get involved take a look around the site, join the Facebook group and come along and visit on a Sunday morning between 10 and 12 at the garden within Barrenjoey High School on Tasman Road, North Avalon.

Bushfire Conference June 2021

NSW Government To Strengthen Planning For Natural Hazards: Feedback Wanted

New guidelines to help communities and councils plan for natural hazards such as bushfires, drought and floods have been released today for public feedback - until June 8, 2021.

In releasing the draft Strategic Guide to Planning for Natural Hazards in NSW, Minister for Planning and Public Spaces Rob Stokes said the recent flooding which devastated parts of the state emphasised the need to plan strategically for natural hazards.

“Our state is the best place to live in Australia but with its natural beauty comes challenges,” Mr Stokes said.

“In the last few years we’ve experienced some of the worst drought, bushfires and flooding on record so it’s important we continually learn and adapt how we plan for these hazards.

“This draft guide supports the findings of the Bushfire Royal Commission that we need to better address legacy risk in our communities by making sure that strategic land[1]use planning builds resilience to known hazards.”

Minister for Police and Emergency Services David Elliott said NSW has been hit by a series of natural disasters in recent years and the NSW Government is working to reduce the impact and costs of extreme weather events on communities where possible.

“Between 2009 and 2019, NSW was affected by 198 declared natural disasters which resulted in significant losses and cost the State approximately $3.6 billion per year,” Mr Elliott said.

“That’s why we need to future proof our regions rather than reacting to disasters when they occur – prevention and mitigation are critical.”

The draft document comprises eight guiding principles:

- Consider natural hazard risk early

- Protect vulnerable people and assets

- Adopt an all-hazards approach

- Involve the community in conversations about risk

- Plan for emergency response and evacuation

- Be information driven· Plan to rebuild the future, not the present

- Understand the relationship between natural processes and natural hazards

The NSW Government’s flood prone planning package will be finalised shortly.

For more information and to provide feedback on the draft natural hazard guide visit planning.nsw.gov.au/Natural-hazards

A Victorian logging company just won a controversial court appeal. Here’s what it means for forest wildlife

Brendan Wintle, The University of Melbourne; Laura Schuijers, The University of Melbourne, and Sarah Bekessy, RMIT UniversityAustralia’s forest-dwelling wildlife is in greater peril after last week’s court ruling that logging — even if it breaches state requirements — is exempt from the federal law that protects threatened species.

The Federal Court upheld an appeal by VicForests, Victoria’s state timber corporation, after a previous ruling in May 2020 found it razed critical habitat without taking the precautionary measures required by law.

The ruling means logging is set to resume, despite the threats it poses to wildlife. At particular risk are the Leadbeater’s possum and greater glider — mammals highly vulnerable to extinction that call the forests home.

So let’s take a look at the dramatic implications for wildlife and the law in more detail.

Why Is This Ruling So Significant?

The Federal Court agreed VicForest’s logging failed to meet its environmental legal requirements. In fact, the Federal Court dismissed every single ground of appeal but one. And it takes only one to win.

The ground that won the case was that the federal environmental law designed to protect threatened species — the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act — did not apply to the logging operations due to a forestry exemption.

To understand the significance of these issues, it’s important to know a bit about the context.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, forestry was passed to the states to regulate. So-called regional forest agreements (RFAs) were struck between federal and state governments. The idea was that forestry would be conducted under these state-led RFAs, avoiding federal scrutiny.

This was meant to streamline procedures, and offer a compromise between sometimes conflicting objectives: conservation and commercially profitable forestry.

However, states weren’t necessarily meant to have absolute control, and a check-and-balance system was put in place. If a logging operation doesn’t follow the RFA requirements, then the federal law is called in.

That way, states have control, but there’s a backup safety net for threatened species (which the federal government has an obligation to protect under international law).

This backup safety net is what the original case was testing. Friends of the Leadbeater’s Possum sued VicForests, arguing the logging operations breached the Victorian RFA, and the organisation won the case.

In response to the original decision against VicForests, Nationals Senator Bridget McKenzie introduced a private members bill, seeking to strengthen logging’s exemption from federal scrutiny.

If passed, the bill would make forestry activities within RFA areas exempt from scrutiny under the EPBC Act, regardless of whether they follow RFA rules.

Both the court decision and the bill respond to a need for industry certainty and seek to minimise opportunities for legal action against logging under the EPBC Act. But they remove any certainty for environmental protection.

What Does This Mean For Wildlife?

RFAs were established with the best of intentions. But unfortunately, they haven’t been working to protect wildlife — a point made clear in the EPBC Act’s recent ten-year independent review.

As former competition watchdog chair Professor Graeme Samuel, who led the review, said in his final report:

there are fundamental shortcomings in the interactions between RFAs and the EPBC Act.

The RFAs haven’t been updated as they were meant to be, despite dramatic changes in the environment, such as from mega-fires, and the warming and drying climate. These factors totally change the game for forestry and forest-dependent wildlife, such Leadbeater’s possum and the greater glider, which are declining dramatically.

We are currently experiencing a global mass extinction event, and Australia is a global extinction leader. Australia is responsible for 35% of all modern mammal extinctions globally and has seen an average decline of 50% in threatened bird populations since 1985.

Cutting down trees may seem insignificant to some, in the scheme of things. But small effects can accumulate into huge declines, like a death by a thousand cuts.

Both Leadbeater’s possum and the greater glider depend on large old trees with hollows (that take more than 100 years to develop) for shelter. Without many of these trees, they cannot survive.

Read more: Comic explainer: forest giants house thousands of animals (so why do we keep cutting them down?)

Logging in Victoria has led to a decline in the number and extent of these particular trees, and reduces future large tree numbers. This makes the animals more vulnerable.

To avoid extinctions, we can’t afford to lose more ground by continuing practices that damage or remove habitat.

The Writing Is On The Wall

But things could be changing soon. The Victorian government plans to ban native timber harvesting from 2030. This happens to be the same year a decades-old contract with a wood pulp and paper company expires, currently binding the state to provide pulp logs by a legislated supply agreement.

After 2030, paper, pulp, and timber products would be logged from plantations rather than native forests. The writing is already on the wall.

Whether it’s the federal or state governments in charge, forest management needs to be scientifically robust, with strong compliance, enforcement and governance. Otherwise, as we’ve seen, there’s a significant risk of slippage and loss of trust.

Even before the mega-fires of 2019-20, most Australians didn’t support native forest logging. After the fires, their worries increased, with a majority expressing concerns that Australia’s unique environment might never be the same.

And as a result of rising community expectations on how the environment is treated, some businesses have pivoted.

Read more: Logged native forests mostly end up in landfill, not in buildings and furniture

Many companies now see being associated with environmentally poor outcomes as risky. Bunnings, for example, has already banned VicForests’ native timber. The World Economic Forum places biodiversity loss in the top five risks to the global economy. And a global taskforce is being established that could eventually see environmental disclosures as a new norm.

It’s clear the status quo has led to an alarming rate of species decline. This decline will only be locked in further if legal exemptions make it impossible to hold law-breakers to account.![]()

Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Ecology, School of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne; Laura Schuijers, Research Fellow in Environmental Law, The University of Melbourne, and Sarah Bekessy, Professor in Sustainability and Urban Planning, Leader, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Federal Court Rejects 20 Of 21 Grounds Of Appeal For VicForests And Supports Original Findings Of VicForests Led Extinctions

Mountain Pygmy-Possum Conservation Effort Gets Local And International Friends Onboard

Native forest logging makes bushfires worse – and to say otherwise ignores the facts

Philip Zylstra, University of Wollongong; Grant Wardell-Johnson, Curtin University; James Watson, The University of Queensland, and Michelle Ward, The University of QueenslandThe Black Summer bushfires burned far more temperate forest than any other fire season recorded in Australia. The disaster was clearly a climate change event; however, other human activities also had consequences.

Taking timber from forests dramatically changes their structure, making them more vulnerable to bushfires. And, crucially for the Black Summer bushfires, logged forests are more likely to burn out of control.

Naturally, the drivers of the fires were widely debated during and after the disaster. Research published earlier this month, for example, claimed native forest logging did not make the fires worse.

We believe these findings are too narrowly focused and in fact, misleading. They overlook a vast body of evidence that crown fire – the most extreme type of bushfire behaviour, in which tree canopies burn – is more likely in logged native forests.

Crown Fires Vs Scorch

The Black Summer fires occurred in the 2019-20 bushfire season and burned vast swathes of Australia’s southeast. In some cases, fire spread through forests with no recorded fire, including some of the last remnants of ancient Gondwanan rainforests.

Tragically, the fires directly killed 33 people, while an estimated 417 died due to the effects of smoke inhalation. A possible three billion vertebrate animals perished and the risk of species extinctions dramatically increased.

Much of the forest that burned during Black Summer experienced crown fires. These fires burn through the canopies of trees, as well as the undergrowth. They are the most extreme form of fire behaviour and are virtually impossible to control.

Crown fires pulse with such intense heat they can form thunderstorms which generate lightning and destructive winds. This sends burning bark streamers tens of kilometres ahead of the fire, spreading it further. The Black Summer bushfires included at least 18 such storms.

Various forest industry reports have recognised logging makes bushfires harder to control.

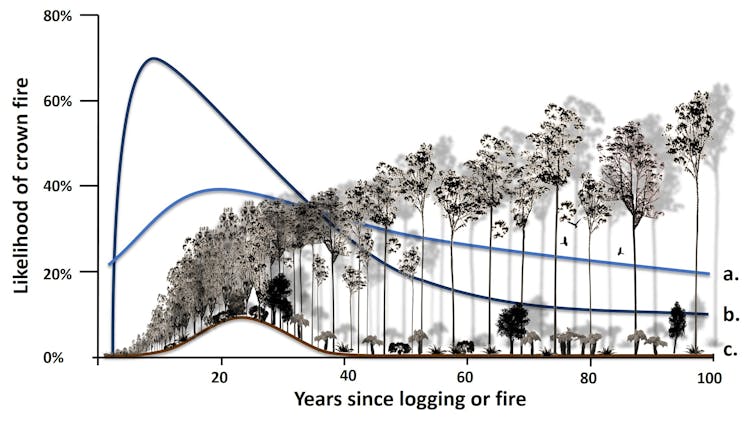

And to our knowledge, every empirical analysis so far shows logging eucalypt forests makes them far more likely to experience crown fire. The studies include:

A 2009 paper suggesting changes in forest structure and moisture make severe fire more likely in logging regrowth compared to undisturbed forest

2012 research concluding the probability of crown fires was higher in recently logged areas than in areas logged decades before

A 2013 study that showed the likelihood of crown fire halved as forests aged after a certain point

2014 findings that crown fire in the Black Saturday fires likely peaked in regrowth and fell in mature forests

2018 research into the 2003 Australian Alps fires, which found the same increase in the likelihood of crown fire during regrowth as was measured following logging.

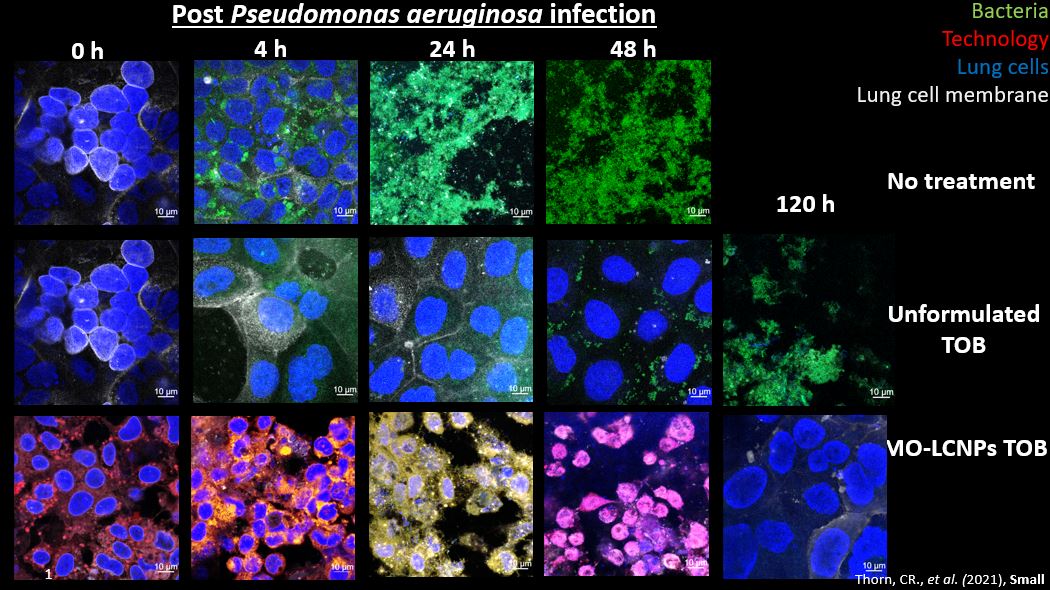

The combined findings of these studies are represented in the image below:

Crown Fires Take Lives

The presence of crown fire is a key consideration in fire supression, because crown fires are very hard to control.

However, the study released last week – which argued that logging did not worsen the Black Summer fires – focused on crown “scorch”. Crown scorch is very different to crown fire. It is not a measure of how difficult it is to contain the fire, because even quite small flames can scorch a drought-stressed canopy.

Forestry studies tend to focus more on crown scorch, which damages timber and is far more common than crown fires.

But the question of whether logging made crown scorch worse is not relevant to whether a fire was uncontrollable, and thus was able to destroy homes and lives.

Importantly, when the study said logging had a very small influence on scorch, this was referring to the average scorch over the whole fire area, not just places that had been logged. That’s like asking how a drought in the small town of Mudgee affects the national rainfall total: it may not play a large role overall, but it’s pretty important to Mudgee.

The study examined trees in previously logged areas, or areas that had been logged and burned by fires of any source. It found they were as likely to scorch on the mildest bushfire days as trees in undisturbed forests on bad days. These results simply add to the body of evidence that logging increases fire damage.

Managing Forests For All

Research shows forests became dramatically less likely to burn when they mature after a few decades. Mature forests are also less likely to carry fire into the tree tops.

For example during the Black Saturday fires in 2009, the Kilmore East fire north of Melbourne consumed all before it as a crown fire. Then it reached the old, unlogged mountain ash forests on Mount Disappointment and dropped to the ground, spreading as a slow surface fire.

The trees were scorched. But they were too tall to ignite, and instead blocked the high winds and slowed the fire down. Meanwhile, logged ash forests drove flames high into the canopy.

Despite decades of opportunity to show otherwise, the only story for eucalypt forests remains this: logging increases the impact of bushfires. This fact should inform forest management decisions on how to reduce future fire risk.

We need timber, but it must be produced in ways that don’t endanger human lives or the environment.

Philip Zylstra, Adjunct Associate Professor at Curtin University, Honorary Fellow at University of Wollongong, University of Wollongong; Grant Wardell-Johnson, Associate Professor, Environmental Biology, Curtin University; James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland, and Michelle Ward, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Koala Management Program Commences At Cape Otway

International Energy Agency warns against new fossil fuel projects. Guess what Australia did next?

Even if every country meets its current climate targets, Earth’s temperature will still rise by a dangerous 2.1℃ this century, according to sobering findings from a new International Energy Agency report.

The IEA found the route to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 was “narrow and extremely challenging”, and electricity grids in developed economies such as Australia must be zero emissions by 2053. The IEA was abundantly clear: no new fossil fuel projects should be approved.

The report couldn’t come at a worse time for the Morrison government. This week, it announced A$600 million for a major new gas-fired power plant at Kurri Kurri in New South Wales, claiming it was needed to shore up electricity supplies.

The IEA’s findings cast serious doubt on this decision, and put even more pressure on Australia ahead of crucial international climate talks in Glasgow in November. So let’s take a look at the report in more detail, and see how Australia measures up.

What The Report Said

The IEA report sets out a comprehensive roadmap to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The good news is this is still achievable. But it’ll take a lot money and enormous effort.

There must be what the report describes as a “total transformation of the energy systems that underpin our economies”. Put simply, the world’s energy economy must be grounded in solar and wind — not coal, gas and oil.

The report works from a basic principle: even if the climate pledges countries have made under the Paris agreement are fully achieved, there will still be 22 billion tonnes of global carbon dioxide emissions in 2050.

This is well short of net zero.

So the IEA set out more than 400 milestones to achieve the global energy transformation. And these absolutely must be complied with if we’re to stop catastrophic global warming and limit temperature rise to 1.5℃.

The milestones include:

Massive investment in electricity networks

Enormous amounts of money are needed to shift away from fossil fuels and meet the global electricity demand doubling over the next 30 years. Existing networks took 130 years to build — we need to build the same again in about one-sixth the time. This includes investing in hydrogen and bio-energy (energy made from organic material), which the report calls a “pillar of decarbonisation”.

Read more: The 1.5℃ global warming limit is not impossible – but without political action it soon will be

Transport

Electric vehicles need to rapidly expand to 65% of the global fleet by 2030, and 100% by 2050. This will require an enormous increase in public electric vehicle charging units and hydrogen refuelling units. To facilitate this shift, petrol and diesel will be phased out. Many countries around the world, including the United Kingdom and Japan, have already introduced a ban on new fossil fuel cars by 2030.

Building and industry

We need to urgently retrofit homes and buildings to make them more energy efficient. Steel, cement and chemical industries, primary emitters, must shift to carbon capture and sequestration and hydrogen.

But the biggest take-home message for Australia is there must be no new development in fossil fuel beyond 2021.

No New Fossil Fuel Development

The report states:

Beyond projects already committed as of 2021, there are no new oil and gas fields approved for development in our pathway, and no new coal mines or mine extensions are required.

Global demand for oil peaked in 2019, and has declined since then, largely due to COVID-19 lockdowns. Under the roadmap, this decline will continue and reach 75% by 2050. Any growth in demand during this period will be met by growing emergent markets in renewables, green hydrogen and bio-energy.

And of course, the report states no new coal plants should be financially supported unless equipped with carbon capture and sequestration. Inefficient coal plants must be phased out by 2030.

If the roadmap is followed, renewable energy will overtake coal by 2026, and oil and gas by 2030.

For this to happen, annual additions of 630 gigawatts of solar and 390 gigawatts of wind power will be required by 2030. This means the world needs to install the equivalent of “the world’s largest solar park roughly every day”, according to the report.

Australia, Are You Listening?

Australia’s gas-fired recovery plans are directly inconsistent with the IEA roadmap. The government has argued expanding fossil fuel supply is critical for energy security.

Not only did the federal government just announce over a half a billion dollars for a new gas-fired power plant in NSW, it’s also spending a further $173 million to develop the Beetaloo basin in the Northern Territory, another gas reserve.

Read more: Paying Australia’s coal-fired power stations to stay open longer is bad for consumers and the planet

Experts, advisers and Energy Security Board chair Kerry Schott have all disagreed with these moves. They argue, in line with the IEA report, that cheaper, cleaner alternatives to gas generation, such as wind and solar, can easily provide the dispatchable power required.

The government’s stubborn fossil fuel funding will make it more difficult than it already is to stop global warming beyond 1.5℃.

Australia must immediately stop investing in new fossil fuel projects. While this may be a difficult transition to accept given the enormous scope of gas reserves in Australia, there’s no point spending vast amounts of money on new infrastructure to extract a resource that will be commercially unviable in a decade.

Australia is ignoring the economic and environmental imperatives of transitioning to a low carbon framework. This is reckless, and unfair to other countries. We have the resource capacity and economic strength to transition our energy sector, unlike many developing countries. But we choose not to.

A National Embarrassment

John Kerry, the US special presidential envoy for climate, says the next round of international climate talks in Scotland is the “last best chance the world has” to avoid a climate crisis.

But Australia’s investment in new gas development stands in stark contrast to the increasingly ambitious energy commitments of other developed countries. We shouldn’t come empty-handed, with no new targets, to yet another international climate summit.

US President Joe Biden has vowed to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52% compared with 2005 levels. He has banned new oil and gas leases on federal land, removed fossil fuel subsidies and plans to double wind capacity by 2030.

Likewise, the European Commission seeks to stop funding oil and gas projects. Denmark recently implemented a ban on future gas extraction in the North Sea. And Spain has done the same.

Australia is ignoring its global responsibilities. As a result, we’ll be hit hard by the so-called “Carbon Border Adjustment” policies from the US and European Union, which tax imported goods according to their carbon footprint.

Ultimately, our actions will leave us economically and environmentally isolated in a rapidly emerging new energy world order.

Read more: The EU is considering carbon tariffs on Australian exports. Is that legal? ![]()

Samantha Hepburn, Director of the Centre for Energy and Natural Resources Law, Deakin Law School, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Government-owned firms like Snowy Hydro can do better than building $600 million gas plants

Arjuna Dibley, The University of MelbourneThe Morrison government today announced it’s building a new gas power plant in the Hunter Valley, committing up to A$600 million for the government-owned corporation Snowy Hydro to construct the project.

Critics argue the plant is inconsistent with the latest climate science. And a new report by the International Energy Agency has warned no new fossil fuel projects should be funded if we’re to avoid catastrophic climate change.

The move is also inconsistent with research showing government-owned companies can help drive clean energy innovation. Such companies are often branded as uncompetitive, stuck in the past and unable to innovate. But in fact, they’re sometimes better suited than private firms to take investment risks and test speculative technologies.

And if the investments are successful, taxpayers, the private sector and consumers share the benefits.

Lead, Not Limit

Federal energy minister Angus Taylor announced the funding on Wednesday. He said the 660-megawatt open-cycle gas turbine at Kurri Kurri will “create jobs, keep energy prices low, keep the lights on and help reduce emissions”.

Experts insist the plan doesn’t stack up economically and may operate at less than 2% capacity.

But missing from the public debate is the question of how government-owned companies such as Snowy Hydro might be used to accelerate the clean energy transition.

Australian governments (of all persuasions) have not often used the companies they own to lead in clean energy innovation. Many, such as Hydro Tasmania, still rely on decades-old hydroelectric technologies. And others, such as Queensland’s Stanwell Corporation and Western Australia’s Synergy, rely heavily on older coal and gas assets.

Asking Snowy Hydro to build a gas-fired power plant is yet another example – but it needn’t be this way.

Read more: A single mega-project exposes the Morrison government's gas plan as staggering folly

The Burning Question

Globally, more than 60% of electricity comes from wholly or partially state-owned companies. In Australia, despite the 20-year trend towards electricity privatisation, government-owned companies remain important power generators.

At the Commonwealth level, Snowy Hydro provides around 20% of capacity to New South Wales and Victoria. And most electricity in Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia is generated by state government-owned businesses.

But political considerations mean government-owned electricity companies can struggle to navigate the clean energy path.

For example in April this year, the chief executive of Stanwell Corporation, Richard Van Breda, suggested the firm would mothball its coal-powered generators before the end of their technical life, because cheap renewables were driving down power prices.

Queensland’s Labor government was reportedly unhappy with the announcement, fearing voter backlash in coal regions. Breda has since stepped down and Stanwell is reportedly backtracking on its transition plans.

Such examples beg the question: can government-owned companies ever innovate on clean energy? A growing literature in economics, as well as several real-world examples, suggest that under the right conditions, the answer is yes.

Read more: The 1.5℃ global warming limit is not impossible – but without political action it soon will be

Privatised Is Not Always Best

Economists have traditionally argued state-owned companies are not good innovators. As the argument goes, the absence of competitive market forces makes them less efficient than their private sector peers.

But recent research by academics and international policy institutions such as the OECD has shown government ownership in the electricity sector can be an asset, not a curse, for achieving technological change.

The reason runs contrary to orthodox economic thinking. While competition can lead to firm efficiency, some economists argue government-owned firms can take greater risks. Without the pressure for market-rate returns to shareholders, government enterprises may be freer to invest in more speculative technologies.

My ongoing research has shown the reality is even more complex. Whether state-owned electric companies can drive clean energy innovation depends a great deal on government interests and corporate governance rules.

For example, consider the New York Power Authority (NYPA) which, like Snowy Hydro, is wholly government owned.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has deliberately sought to use NYPA to decarbonise the state’s electricity grid. The government has managed the company in a way that enables it to take risks on new transmission and generation technologies that investor-owned peers cannot.

For instance, NYPA is investing in advanced sensors and computing systems so it can better manage distributed energy sources such as solar and wind. The technology will also simulate major catastrophic events, including those likely to ensue from climate change.

These investments are likely to contribute to greater grid stability and greater renewables use, benefiting not just NYPA but other electricity generators and ultimately, consumers.

Such innovation is nothing new. Also in the US, the state-owned Sacramento Municipal Utility District built one of the first utility-scale solar projects in the world in 1984.

The Way Forward

More could be done to ensure Australian government-owned corporations are clean energy catalysts.

Clean energy technologies can struggle to bridge the gap from invention to widespread adoption. Public investment can bring down the price of such technologies or demonstrate their efficacy.

In this regard, government-owned companies could work with private technology firms to invest in technologies in the early stages of development, and which could have significant public benefits. For instance, in 2020, the Western Australian government-owned company Synergy sought to build a 100 megawatt battery with private sector partners.

But many problems facing state-owned companies are the result of ever-changing government policy priorities. The firms should be reformed so they are owned by government, but operated at arm’s length and with other partners. This might better enable clean energy investment without the politics.

Arjuna Dibley, Visiting Researcher, Climate and Energy College, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Mouse plague: bromadialone will obliterate mice, but it'll poison eagles, snakes and owls, too

It’s the smell that hits you first. The scent of urine and decomposing bodies. Then you notice other signs: scuttles and squeaks, small dead bodies leaking blood, tails sticking out of hubcaps.

If you’ve lived through a mouse plague, you’ve seen this, and smelled the stench of mice dying of poison baits.

As a desperate measure to help combat the mouse plague devastating rural communities across New South Wales, the state government yesterday secured 5,000 litres of bromadialone. This is a bait that’s usually illegal to roll out at the proposed scale.

This is a bad idea. While bromadiolone effectively kills mice, it also travels up the food chain to poison predators who eat the mice, and other species. And these predators, from wedge-tailed eagles to goannas, are coming in out in droves to feast on their abundant prey.

When Your Prey Is Everywhere

Animal plagues in Australia are fuelled by the “boom and bust” of rainfall.

We have natural, flood-driven population explosions of the native long-haired rat, with accompanying booms of letter-winged kites, their predator. We also have locust plagues when the conditions are right, leading to antechinus or mice plagues which eat the locusts.

Since at least the late 1800s, we’ve had terrible plagues of the introduced house mouse (Mus musculus). But rarely has it been this bad, with conditions currently seeming worse than the last plague in 2011, which caused over A$200 million in crop damage alone.

High numbers of birds of prey — nankeen kestrels, black-shouldered kites and barn owls — are often reported feasting on plague mice.

Snakes, goannas, native carnivores such as quolls, and feral cats and foxes, also take advantage of the abundant food. Pets, especially cats and some dogs, are highly likely to consume mice under these conditions, too.

Poisoning The Food Web

Laying out poison baits is one way people try to end mouse infestations and plagues. So-called “anticoagulant rodenticides” are divided into first and second generations, based on when they were first synthesised and the differences in potency.

Second generation anticoagulant rodenticides have higher toxicities than first generation, and are lethal after a single feed. First generation rodenticides, on the other hand, require rodents to feed on them for consecutive days to be lethal.

But mouse-eating predators are highly exposed to second generation rodenticides. For most animal species, the lethal doses of rodenticide aren’t yet known.

A scientific review from 2018 documented the poisoning of 31 bird, five mammal and one reptile species. Second generation aniticoaugulant rodenticides were implicated in the death of these animals.

Our research from 2020 found urban reptiles are highly exposed to second generation rodenticides, too. This includes mouse-eating snakes, called dugites, which had up to five different rodent poisons in them.

We also found poisons in frog-eating tiger snakes, and in omnivorous bobtail skinks which eat fruit, vegetation and snails. This is even more concerning because it shows how second generation rodenticides can saturate the entire foodweb, affecting everything from slugs to fish.

Bromadiolone Is Particularly Dangerous, Even To Humans

The NSW government secured bromadialone baits as part of its $50 million mouse plague support package for regional communities.

Five thousand litres of the poison can treat around 95 tonnes of grain, and the government will provide it for free to primary producers once federal authorities approve its use.

Bromadiolone is usually restricted to use in and around buildings. But given the widespread impacts on wildlife, using bromadiolone at the proposed scale will do more harm than good.

Past research on bromadialone has shown residues persist for up to 135 days in the carcasses of voles (another rodent species). In international studies, bromadiolone has been found in the livers of a host of birds of prey, including a range of owl species, red kites, sparrowhawks and golden eagles.

And it’s not just a problem for wildlife, humans are also at risk of exposure. For example, we can get exposed from eating eggs from chickens that feed on poisoned mice, or more directly from eating other animals that may have ingested poisoned mice.

A 2013 study looked at chicken eggs for human consumption, and detected bromadialone in eggs between five and 14 days after the chicken ingested the poison. It’s not yet clear how many of these eggs we’d have to eat for us to get sick.

So What Are The Alternatives?

There are highly effective first generation rodenticides that provide viable solutions for managing mouse plagues. They may take a little longer to kill mice, but the upshot is they don’t stick around in the environment. A 2020 study found house mice in Perth didn’t have genetic resistance to first generation rodenticides, which suggests they’re effectively lethal.

Another approach has been to use zinc phosphide, a poison which is unlikely to secondarily poison other animals that eat the poisoned mice. However, zinc phosphide is still extremely toxic and will kill sheep, cows, pets and even humans if directly eaten.

Rolling out double-strength zinc phosphide may be the lesser of the evils in causing secondary poisoning, but only if used very carefully.

And another way to help control the mouse plague is to limit food resources for mice on farms. Farmers can minimise grain on ground, and Australia should invest in research for grain storage facilities that are less permeable to mice.

Mouse plagues are a regular cycle in Australia. Natural predators not only help create healthy, natural ecosystems, but also they help with mouse control. Second generation rodenticides will only destroy and weaken the predator populations we need to help us combat the next plague.![]()

Robert Davis, Senior Lecturer in Wildlife Ecology, Edith Cowan University; Bill Bateman, Associate professor, Curtin University; Damian Lettoof, PhD Candidate, Curtin University; Maggie J. Watson, Lecturer in Ornithology, Ecology, Conservation and Parasitology, Charles Sturt University, and Michael Lohr, Adjunct Lecturer, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New Plan To Revitalise Oldest NSW's Park By Installing Mountain Bike Trails

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park, Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Planning Considerations

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Plan of Management

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Mountain Biking Plan

Forestry Corporation Must Investigate Breaches Of Post-Fire Logging Standards In Mogo State Forest

What: Rally to Save Swift Parrots. Speakers from NCC, Birdlife Australia and local activists will be there.

When: 1:15pm, Saturday, May 22

Where: 2 Museum Pl, Batemans Bay

Why: The community will rally at Batemans Bay Forestry Corporation office to oppose native forest logging on the South Coast and destruction of swift parrot habitat.

The $600M The Federal Government Is Squandering On A Kurri Kurri Gas Plant Would Be Better Invested In Big Batteries

The story of Rum Jungle: a Cold War-era uranium mine that’s spewed acid into the environment for decades

Buried in last week’s budget was money for rehabilitating the Rum Jungle uranium mine near Darwin. The exact sum was not disclosed.

Rum Jungle used to be a household name. It was Australia’s first large-scale uranium mine and supplied the US and British nuclear weapons programs during the Cold War.

Today, the mine is better known for extensively polluting the Finniss River after it closed in 1971. Despite a major rehabilitation project by the Commonwealth in the 1980s, the damage to the local environment is ongoing.

I first visited Rum Jungle in 2004, and it was a colourful mess, to say the least. Over later years, I saw it worsen. Instead of a river bed, there were salt crusts containing heavy metals and radioactive material. Pools of water were rich reds and aqua greens — hallmarks of water pollution. Healthy aquatic species were nowhere to be found, like an ecological desert.

The government’s second rehabilitation attempt is significant, as it recognises mine rehabilitation isn’t always successful, even if it appears so at first.

Rum Jungle serves as a warning: rehabilitation shouldn’t be an afterthought, but carefully planned, invested in and monitored for many, many years. Otherwise, as we’ve seen, it’ll be left up to future taxpayers to fix.

The Quick And Dirty History

Rum Jungle produced uranium from 1954 to 1971, roughly one-third of which was exported for nuclear weapons. The rest was stockpiled, and then eventually sold in 1994 to the US.

The mine was owned by the federal government, but was operated under contract by a former subsidiary of Rio Tinto. Back then, there were no meaningful environmental regulations in place for mining, especially for a military project.

The waste rock and tailings (processed ore) at Rum Jungle contains significant amounts of iron sulfide, called “pyrite”. When mining exposes the pyrite to water and oxygen, a chemical reaction occurs generating so-called “acidic mine drainage”. This drainage is rich in acid, salts, heavy metals and radioactive material (radionuclides), such as copper, zinc and uranium.

Acid drainage seeping from waste rock, plus acidic liquid waste from the process plant, caused fish and macroinvertebrates (bugs, worms, crustaceans) to die out, and riverbank vegetation to decline. By the time the mine closed in 1971, the region was a well-known ecological wasteland.

When mines close, the modern approach is to rehabilitate them to an acceptable condition, with the aim of minimal ongoing environmental damage. But after working in environmental engineering across Australia for 26 years, I’ve seen few mines completely rehabilitated — let alone successfully.

Many Australian mines have major problems with acid mine drainage. This includes legacy mines from historical, unregulated times (Mount Morgan, Captains Flat, Mount Lyell) and modern mines built under stricter environmental requirements (Mount Todd, Redbank, McArthur River).

This is why Rum Jungle is so important: it was one of the very few mines once thought to have been rehabilitated successfully.

So What Went Wrong?

From 1983 to 1986, the government spent some A$18.6 million (about $55.5 million in 2020 value) to reduce acid drainage and restore the Finniss River ecology. Specially engineered soil covers were placed over the waste rock to reduce water and oxygen getting into the pyrite.

The engineering project was widely promoted as successful through conferences and academic studies, with water quality monitoring showing that the metals polluting the Finniss had substantially subsided. But this lasted only for a decade.

Read more: Expensive, dirty and dangerous: why we must fight miners' push to fast-track uranium mines

By the late 1990s, it became clear the engineered soil covers weren’t working effectively anymore.

First, the design was insufficient to reduce infiltration of water during the wet season (thicker covers should have been used). Second, the covers weren’t built to design in parts (they were thinner and with the wrong type of soils).

The first reason is understandable, we’d never done this before. But the second is not acceptable, as the thinner covers and wrong soils made it easier for water and oxygen to get into the waste rock and generate more polluting acid mine drainage.

The Stakes Are Higher

There are literally thousands of recent and still-operating mines around Australia, where acid mine drainage remains a minor or extreme risk. Other, now closed, acid drainage sites have taken decades to bring under control, such as Brukunga in South Australia, Captain’s Flat in NSW, and Agricola in Queensland.

We got it wrong with Rum Jungle, which generated less than 20 million tonnes of mine waste. Modern mines, such as Mount Whaleback in the Pilbara, now involve billions of tonnes — and we have dozens of them. Getting even a small part of modern mine rehabilitation wrong could, at worst, mean billions of tonnes of mine waste polluting for centuries.

So what’s the alternative? Let’s take the former Woodcutters lead-zinc mine, which operated from 1985 to 1999, as an example.

Given its acid drainage risks, the mine’s rehabilitation involved placing reactive waste into the open pit, rather than using soil covers. “Backfilling” such wastes into pits makes good sense, as the pyrite is deeper and not exposed to oxygen, substantially reducing acid drainage risks.

Backfilling isn’t commonly used because it’s widely perceived in the industry as expensive. Clearly, we need to better assess rehabilitation costs and benefits to justify long-term options, steering clear of short-term, lowest-cost approaches.

The Woodcutters experience shows such thinking can be done to improve the chances for successfully restoring the environment.

Getting It Right

The federal government funded major environmental studies of the Rum Jungle mine from 2009, including an environmental impact statement in 2020, before the commitment in this year’s federal budget.

Read more: It's not worth wiping out a species for the Yeelirrie uranium mine

The plan this time includes backfilling waste rock into the open pits, and engineering much more sophisticated soil covers. It will need to be monitored for decades.

And the cost of it? Well, that was kept confidential in the budget due to sensitive commercial negotiations.

But based on my experiences, I reckon they’d be lucky to get any change from half a billion dollars. Let’s hope we get it right this time.![]()

Gavin Mudd, Associate Professor of Environmental Engineering, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

'One sip can kill': why a highly toxic herbicide should be banned in Australia

There’s a weedkiller used in Australia that’s so toxic, one sip could kill you. It’s called paraquat and debate is brewing over whether it should be banned.

Paraquat is already outlawed in many places around the world. The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority has been reviewing paraquat’s use here for more than two decades, and its final decision is due later this year.

We are medical and environmental scientists, and have researched the harmful effects of paraquat, even when it’s used within the recommended safety range. We strongly believe the highly toxic chemical should be banned in Australia.

The potentially lethal effects on humans are well known. In Australia in 2012, for example, a farmer died after a herbicide containing paraquat accidentally sprayed into his mouth. And our research has found paraquat also causes serious environmental damage.

Paraquat: The Story So Far

Paraquat is the active ingredient in Gramoxone, among other products. It has been used since the 1950s, mostly to control grass and weeds around crops such as rice, cotton and soybeans.

Paraquat is registered as a schedule 7 poison on the national registration scheme, meaning its use is strictly regulated.

Suppliers of paraquat say it should not be banned, insisting herbicides containing it are safe for people and the environment when used for their intended purpose and according to label instructions.

Farmers have also argued against a ban, saying it would force them to use more expensive, less effective alternatives and reduce crop yield.

Paraquat has been banned in more than 50 countries, including the United Kingdom, China, Thailand and European Union nations. However, it’s still widely used by farmers in the developing world, and in Australia and the United States.

Read more: Ban on toxic mercury looms in sugar cane farming, but Australia still has a way to go

A Chemical Peril

Paraquat is a non-selective herbicide, which means it kills plants indiscriminately. It does so by inhibiting photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert sunlight into chemical energy.

Paraquat stays in the environment for a long time. It’s well known for causing collateral damage to plants and animals. For example, even at very low concentrations, paraquat has been found to harm the growth of honey bee eggs.

Exposure to living organisms can occur by spray drift or when paraquat is sprayed on crops then reaches surface and underground sources of drinking water.

Paraquat can have unintended consequences for biological organisms and the environment, particular in waterways. Our recent paper summarised the evidence of the harmful effects of paraquat at realistic field concentrations.

We found evidence that paraquat can severely inhibit healthy bacterial growth in aquatic environments, which in turn affects nutrient cycling and the decomposition of organic matter.

The research also shows paraquat can distort tropical freshwater plankton communities by negatively impacting metabolic diversity and reducing phytoplankton growth.

In fish, paraquat has been found to lead to a death rate of common carp three times higher than the weed it is used to control.

‘One Sip Can Kill’

In addition to the environmental effects, of course, paraquat is highly toxic to humans. A small accidental sip can be fatal and there is no antidote.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says paraquat is a leading cause of fatal poisoning in parts of Asia, the Pacific Islands, and South and Central Americas.

Paraquat enters the body through the skin, digestive system or lungs. If ingested in sufficient amounts, it causes lung damage, leading to pulmonary fibrosis and death through respiratory failure. The liver and kidney can also fail.

Several recent incidents in Australia demonstrate the risks of paraquat poisoning due to human error, even within the current strict regulations.

According to news reports, the Queensland farmer poisoned by paraquat in 2012 was filling a pressure pump to control weeds on his property. The unit cracked and paraquat sprayed over his body and face, entering his mouth.

In 2017, an adult with autism took a sip from a Coke bottle used to store paraquat. The bottle had been left in a disabled toilet at a sports ground in New South Wales. The man was initially given 12 hours to live, but fortunately recovered after two weeks in hospital.

Read more: Pesticides and suicide prevention – why research needs to be put into practice

Paraquat: Not Worth The Risk

There’s a growing awareness of the threats posed by global chemical use. In fact, a paper released this week suggests the potential risk to humanity is on a scale equivalent to climate change.

Paraquat is no doubt an effective herbicide. However, in our view, the risks it poses to humans and the environment outweigh the agricultural benefits.

Current regulation in Australia has not prevented harm from paraquat. It’s time for Australia to join the movement towards a global ban on this toxic chemical.

Read more: The real cost of pesticides in Australia's food boom

Editor’s note: the article has been updated to reflect the fact products other than Gramoxone also contain paraquat.![]()

Nedeljka Rosic, Senior Lecturer, Southern Cross University; Joanne Bradbury, Senior Lecturer, Evidence Based Healthcare, Faculty of Health, Southern Cross University, and Sandra Grace, Professor, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

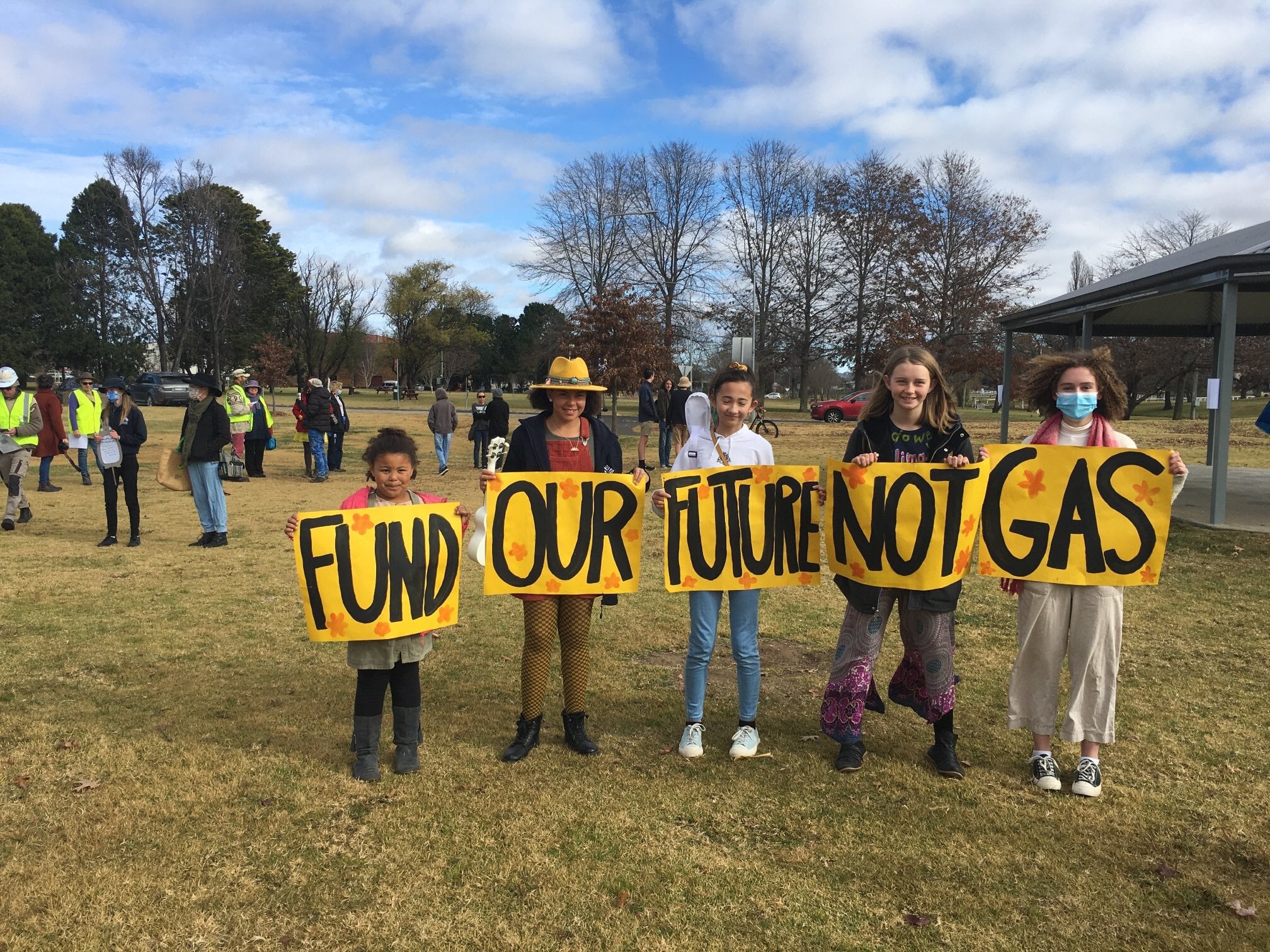

School Strike 4 Climate Change: Thousands Attend May 21st 2021 Strike

Thousands of students and their supporters joined in a School Strike 4 Climate Change on Friday May 21st.

The organisers state;

''Climate change is intensifying the risk of flooding and heavy rainfall and SS4C is calling on the Government to take our future seriously and treat climate change as what it is: a crisis.

The Morrison Government could be protecting our climate, land and water, and creating thousands of new jobs by growing Australia’s renewable energy sector and backing First Nations solutions to protect Country.

Instead, they are lining the pockets of multinational gas companies, which are fuelling the climate crisis, devastating our land and water, wrecking our health and creating very few jobs.

On May 21, we’re striking to tell the Morrison Government that if they care about our future, they must stop throwing money at gas.''

The Sydney rally was one of over 50 taking part across Australia, some quickly reaching Covid-safe capacity, with Speakers pointing out they will be eligible to vote in next year's Federal election.

''This is what democracy looks like. Not corrupt deals with companies, or billions of taxpayer dollars in expensive gas. But the congregation of citizens to protect our climate. - Sydney rally.' - SS4CC

The NSW Teachers Federation supported the strikes.

''School students, angry at the devastating effect of climate change, are once again taking to the streets and striking for change.'' the Federation said in a statement

On 21 May, students from all over Australia are participating in the School Strike 4 Climate (SS4C). They are demanding that public money be used to fund clean futures and not to expand the fossil fuel projects ''accelerating climate change.

And it’s little wonder that the students are taking matters into their own hands. In the last 18 months alone school communities across NSW have been heavily affected by catastrophic bushfires, floods, heatwaves and hazardous air quality.

In addition to no new coal, oil and gas projects, SS4C are also demanding 100 per cent renewable energy generation and exports by 2030, and funding for a just transition with job creation for all fossil fuel workers and communities.

For many students, SS4C will be their first experience of collective action and activism and Federation supports them as they call on the Morrison Government to #fundourfuturenotgas.

Federation Officers, and staff where possible, will be supporting and attending rallies in their local area. Federation also encourages members who are not working on May 21 to attend their nearest rally in support of students.''

Doctors for the Environment Australia also joined the students at strikes.

''DEA doctors and medical students are proud to march with Australia’s young people who are taking a stand against climate inaction.

Our youth have contributed least to the climate crisis but will be the most impacted.

We urge all those in power to listen to their voices and to act on their call for a safe planet now and into the future. '' the organisation posted online.

Armidale School Strike 4 Climate May 21

Coffs Harbour School Strike. Dubbo, Armidale, Port Macquarie, Lismore, the Gold Coast, & Coffs Harbour are all striking. Regional Australians are feeling the impacts of climate change THIS MINUTE and they are fighting to #FundOurFutureNotGas.- SS4CC

Today on #Worimi country, Forster, we demanded that our Governments #FundOurFutureNotGas

Super Flower Blood Moon 2021

Minister's First Student Council Meets

May 19, 2021

The NSW Minister’s Student Council met today for the very first time, giving 27 public school students the power to inform education policy in NSW.

The representative, state-wide council has a direct line to the NSW Education Minister and the Department of Education to share their education and school policy ideas.

Ms Mitchell said the council provides an opportunity for students to interact with policy and decision makers while advocating on behalf of more than 800,000 public school students.

“This initiative was born out of the COVID-19 pandemic, a year that has made us all rethink the way we do things,” Ms Mitchell said.

“Students are at the centre of everything we do in education, so it makes sense that they have a seat at the table where decisions are being made.

“They have a strong vision for the future, and we want to hear their voices when it comes to their education. The council will be a meeting place between students, the Department of Education and the NSW Government.”

The student council has been co-designed over the past six months with the help of a student steering committee, which also played a central role in interviewing and selecting successful applicants.

“I congratulate these students on being selected to advocate on behalf of the 800,000 public school students across 2,200 schools in NSW,” Ms Mitchell said.

“As the first council, they will meet each other for the first time and begin engaging in education policy – it is an enormous responsibility, and I thank them for accepting the challenge.

“I know we have very talented students with brilliant minds across our public schools. I believe students will provide invaluable insights and advice into decisions impacting NSW public students.”

NSW Department of Education photo

Eating More Fruit And Vegetables Linked To Less Stress Study Finds

What is drink spiking? How can you know if it's happened to you, and how can it be prevented?

Recent media reports suggest drink spiking at pubs and clubs may be on the rise.

“Drink spiking” is when someone puts alcohol or other drugs into another person’s drink without their knowledge.

It can include:

putting alcohol into a non-alcoholic drink

adding extra alcohol to an alcoholic drink

slipping prescription or illegal drugs into an alcoholic or non-alcholic drink.

Alcohol is actually the drug most commonly used in drink spiking.

The use of other drugs, such as benzodiazepines (like Rohypnol), GHB or ketamine is relatively rare.

These drugs are colourless and odourless so they are less easily detected. They cause drowsiness, and can cause “blackouts” and memory loss at high doses.

Perpetrators may spike victims’ drinks to commit sexual assault. But according to the data, the most common type of drink spiking is to “prank” someone or some other non-criminal motive.

So how can you know if your drink has been spiked, and as a society, how can we prevent it?

Read more: Weekly Dose: GHB, a party drug that's easy to overdose on but was once used in childbirth

How Often Does It Happen?

We don’t have very good data on how often drink spiking occurs. It’s often not reported to police because victims can’t remember what has happened.

If a perpetrator sexually assaults someone after spiking their drink, there are many complex reasons why victims may not want to report to police.

One study, published in 2004, estimated there were about 3,000 to 4,000 suspected drink spiking incidents a year in Australia. It estimated less than 15% of incidents were reported to police.

It found four out of five victims were women. About half were under 24 years old and around one-third aged 25-34. Two-thirds of the suspected incidents occurred in licensed venues like pubs and clubs.

According to an Australian study from 2006, around 3% of adult sexual assault cases occurred after perpetrators intentionally drugged victims outside of their knowledge.

It’s crucial to note that sexual assault is a moral and legal violation, whether or not the victim was intoxicated and whether or not the victim became intoxicated voluntarily.

How Can You Know If It’s Happened To You?

Some of the warning signs your drink might have been spiked include:

feeling lightheaded, or like you might faint

feeling quite sick or very tired

feeling drunk despite only having a very small amount of alcohol

passing out

feeling uncomfortable and confused when you wake up, with blanks in your memory about what happened the previous night.

If you think your drink has been spiked, you should ask someone you trust to get you to a safe place, or talk to venue staff or security if you’re at a licensed venue. If you feel very unwell you should seek medical attention.

If you believe your drink has been spiked or you have been sexually assaulted, contact the police to report the incident.

How Can Drink Spiking Be Prevented?

Most drink spiking occurs at licensed venues like pubs and clubs. Licensees and people who serve alcohol have a responsibility to provide a safe environment for patrons, and have an important role to play in preventing drink spiking.

This includes having clear procedures in place to ensure staff understand the signs of drink spiking, including with alcohol.

Preventing drink spiking is a collective responsibility, not something to be shouldered by potential victims.

Licensees can take responsible steps including:

removing unattended glasses

reporting suspicious behaviour

declining customer requests to add extra alcohol to a person’s drink

supplying water taps instead of large water jugs

promoting responsible consumption of alcohol, including discouraging rapid drinking

being aware of “red flag” drink requests, such as repeated shots, or double or triple shots, or adding vodka to beer or wine.

A few simple precautions everyone can take to reduce the risk of drink spiking include:

have your drink close to you, keep an eye on it and don’t leave it unattended

avoid sharing beverages with other people

purchase or pour your drinks yourself

if you’re offered a drink by someone you don’t know well, go to the bar with them and watch the bartender pour your drink

if you think your drink tastes weird, pour it out

keep an eye on your friends and their beverages too.

What Are The Consequences For Drink Spiking In Australia?

It’s a criminal offence to spike someone’s drink with alcohol or other drugs without their consent in all states and territories.

In some jurisdictions, there are specific drink and food spiking laws. For example, in Victoria, the punishment is up to two years imprisonment.

In other jurisdictions, such as Tasmania, drink spiking comes under broader offences such as “administering any poison or other noxious thing with intent to injure or annoy”.

Spiking someone’s drink with an intent to commit a serious criminal offence, such as sexual assault, usually comes with very severe penalties. For example, this carries a penalty of up to 14 years imprisonment in Queensland.

There are some ambiguities in the criminal law. For example, some laws aren’t clear about whether drink spiking with alcohol is an offence.

However, in all states and territories, if someone is substantially intoxicated with alcohol or other drugs it’s good evidence they aren’t able to give consent to sex. Sex with a substantially intoxicated person who’s unable to consent may constitute rape or another sexual assault offence.

Getting help

In an emergency, call triple zero (000) or the nearest police station.

For information about sexual assault, or for counselling or referral, call 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732).

If you’ve been a victim of drink spiking and want to talk to someone, the following confidential services can help:

- Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636

- Kids Helpline (5-25 year olds): 1800 55 1800

- National Alcohol and other Drug Hotline: 1800 250 015.

This article has been amended to remove a reference to blood tests for criminal prosecution which may not be available across Australia.![]()

Nicole Lee, Professor at the National Drug Research Institute (Melbourne), Curtin University and Jarryd Bartle, Sessional Lecturer, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Good riddance to boring lectures? Technology isn’t the answer – understanding good teaching is

With some universities returning to face-to-face teaching this year, ANU Vice Chancellor Brian Schmidt noted that, while his university was one of them, lectures would be much less common and not a “crutch for poor pedagogy”. Since then many have discussed the issue of lectures, including the deputy vice chancellor of University of Technology Sydney and the director of the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education in Western Australia, with ideas ranging from embracing the lecture to removing it entirely.

Condemnation of lectures is nothing new. However, the sudden, massive shift to reliance on technology due to COVID has brought increasing calls for ending the venerable lecture. Lectures will, we are told, be replaced by superior, technology-enhanced substitutes.

Underlying these messages are two tacit assumptions: that lectures make for bad teaching and that using technology improves it. But are these reliable assumptions? Rather than simply rejecting lectures and embracing technology, perhaps we should be looking more closely into both, and their relationship to each other.

Read more: COVID killed the on-campus lecture, but will unis raise it from the dead?

Our Love-Hate Relationship With Lectures

Discussions about getting rid of lectures follow predictable patterns. The most common complaints centre on lectures as didactic, learner-passive and boring. Accompanying these critiques is the oft-cited rule that students’ attention span has a limit of 10-18 minutes.

While there is little to no evidence for this claim, we can all identify with struggling to remain awake as we are droned at from a lectern. But most of us can also recall times we were spellbound by a lecture. Anyone who has attended a great TED Talk or even watched one on YouTube knows what it’s like to be captivated for that 3-18 minutes.

Can lectures hold people’s attention beyond 18 minutes, though? The late Professor Randy Pausch was well known for the power and quality of his lectures, especially his final one, “Randy Pausch’s Last Lecture”, which he delivered after receiving a terminal diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. That lecture comes in at a little over one hour and 15 minutes, and many consider it to be a masterwork of powerful teaching and communication.

Clearly, extended lectures can have great impact. Achieving that impact, however, requires understanding what makes for good lecturing and then committing to improvement.

Read more: Videos won't kill the uni lecture, but they will improve student learning and their marks

Push The Boundaries And Reflect On Your Practice

Pausch challenges the stereotype of what a lecture is. He uses physical props, multimedia and other resources to push the boundaries of the lecture beyond a typical, didactic engagement. The result is a lecture that periodically shifts how the audience is engaged and, in doing so, captures and keeps the audience’s attention.

Lecturing at this level requires more than just experience. We must reflect on our teaching practice, evaluate the quality of our lectures in relation to our intentions, and then commit to developing both our lectures and ourselves.

Professor Eric Mazur describes how, while teaching physics at Harvard in the 1990s, he came to the painful realisation that his lectures were failing to keep his students engaged or serve the educational objectives of the subject. He used this realisation as a springboard to improve his lectures and develop his pedagogical knowledge and skills.

Since then, Mazur has become a recognised expert in improving student engagement. He has created a variety of solutions for academics to keep students actively engaged in lectures, even those that go beyond the apocryphal 18-minute limit. The techniques Mazur advocates range from integrating peer instruction into lectures to using a high-tech, collaborative platform to promote students’ pre-lecture preparation.

Read more: 5 tips on how unis can do more to design online learning that works for all students

Lose The Assumptions, Not The Lectern

So then what about the claim that technology is making the lecture obsolete? This seems doubtful for a couple reasons.

Pausch and Mazur’s methods can be transferred to an online space, even if we don’t label the result a lecture. We see many examples of how this works in well-regarded online learning platforms like Khan Academy or LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda). However we label these engagements, it’s obvious technology can actually help lectures rather than just supplant them.

Now let’s turn the question around: does using technology guarantee or even increase the likelihood of good teaching? Technology can make good practices easier, like the use of polls and break-out rooms and timers. Technology can even open new possibilities and paradigms for teaching. But there are no guarantees.

The list of ed tech failures is long and dismaying. Examining what goes wrong, we see some common misunderstandings.

One of these is that adding technology equals enhancing teaching. Technology carries no inherent pedagogical value. Swapping an iPad for a lectern does not, in itself move learning from a boring, didactic experience to interactive, lively engagement.

Just like lectures, our uses of technology and the resulting impact must first come from thoughtful commitment to improving both teaching and teacher.

Be Critical, Be Reflective, Be Better

Technology can never substitute for critically reflecting on the pedagogical value of our practice. And while technology can assist a major transformation, it should never be a requirement for improving how we teach. Whether you’re a high-tech or low-tech teacher, you can give a good lecture or find useful alternatives if you remember to put the pedagogy before the technology.