Inbox and environment News: Issue 497

June 6 - 12, 2021: Issue 497

Proposal To Allow Dogs Offleash On To Mona Vale Beach And Palm Beach

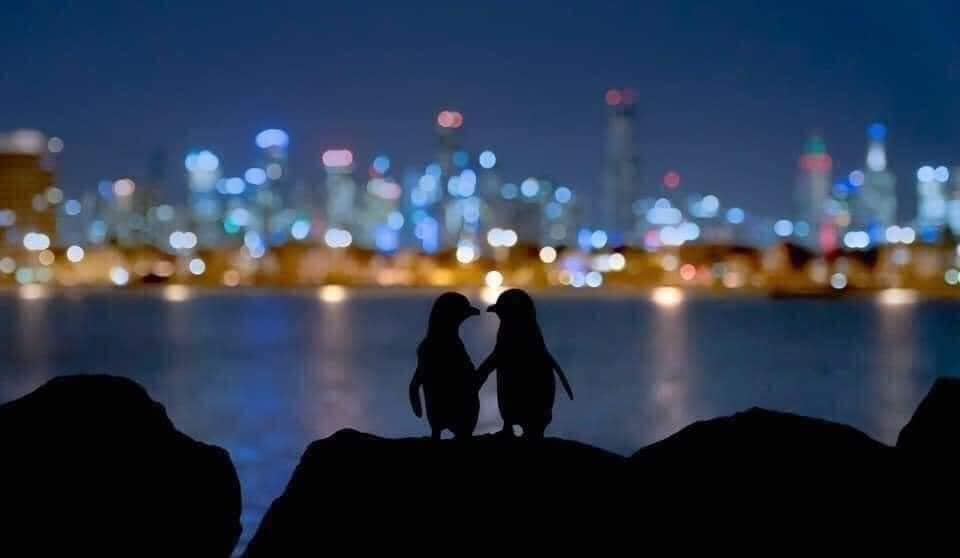

Our Local Wildlife Feels Too

Ocean Photography Awards 2021

Our Own Local Fairy Penguins: World Oceans Day 2021 - June 8th

Here's some more insights to get you in the mood for celebrating where we live. This year the theme of World Oceans Day is The Ocean: Life and Livelihoods. Around 80% of Australians live on the coast, so our lives are intrinsically linked to the ocean – it provides us food, livelihood and a wonderful playground that brings joy and relaxation. We also share this place with many other animals - turtles, all kinds of shorebirds, seals, the whales you will see passing on their migration north at present and Fairy Penguins. Their lives and them getting to live in peace and safety are important too and we are now, between June and August, into their breeding season.

In June 2019 we brought you some news about a project to put fireproof burrows on Lion Island for the colony that lives there - these penguins are seen in the Pittwater estuary and right along the coastal beaches. They used to have nests and colonies on the beaches all along our coast as well - at Turimetta Beach, Narrabeen and Long Reef in particular.

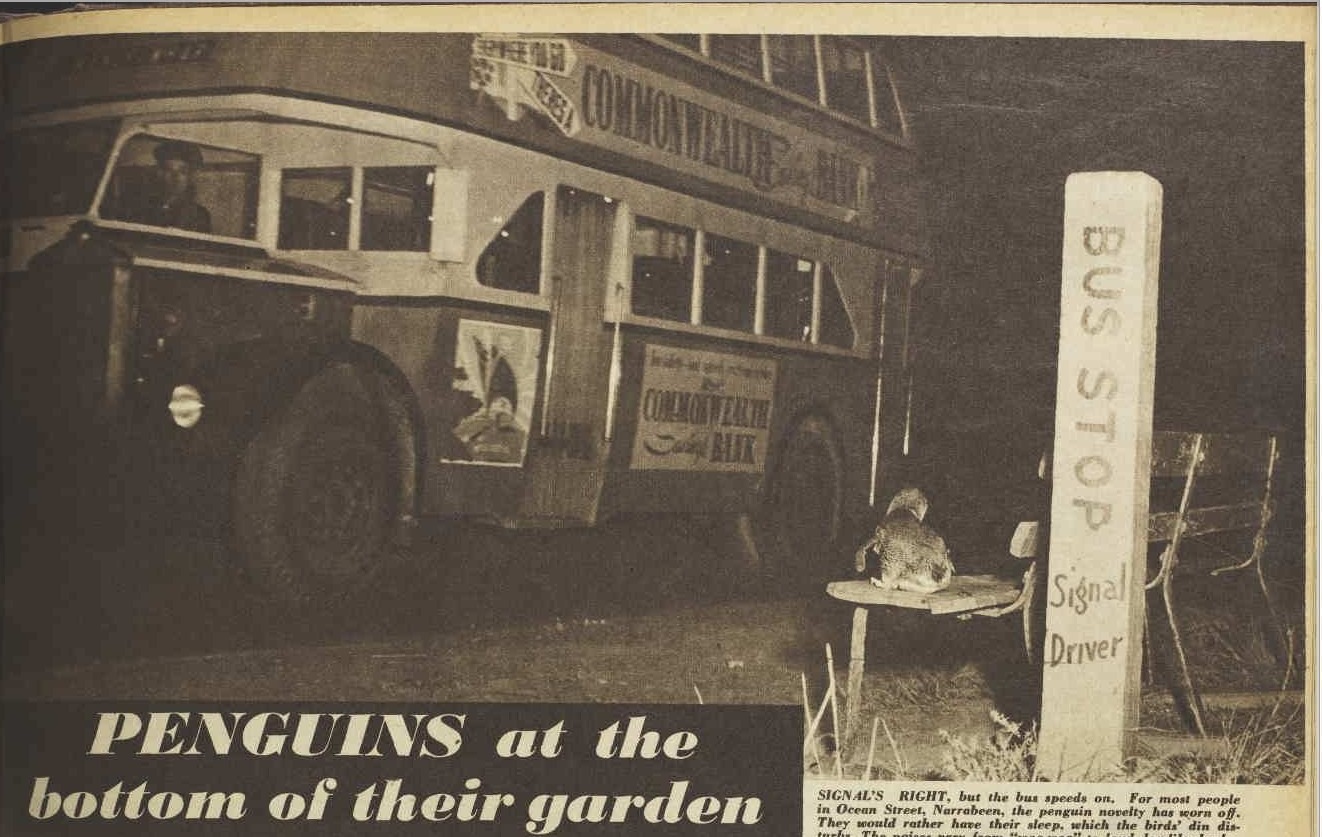

Here's some at Narrabeen in 1955 - and reports of them at Long Reef as well:

When summer comes . . .

.jpg?timestamp=1619878281381)

HE MUST go down to the sea again, the lonely sea and the sky- but only for dinner. This hungry little chap couldn't wait for the rest of the flock that gathers for a nightly 3 a.m. party on the beach. Then they return to their nests to sleep all day.

.jpg?timestamp=1619878349216)

HOUSING TROUBLES begin, at Mrs. E. Whittaker warns off a mother bird for squatting with its young beside her shed. But (inset) the penguin family sits tight till ready to vacate.

PENGUINS at the bottom of their garden

Spring comes with a difference to the gardens of waterfront homes in Ocean Street, Narrabeen, north of Sydney. It brings flocks of fairy penguins-the smallest of the breed-sauntering in from the sea to take up residence for their nesting season. As daytime guests they're welcome, but at nightfall they head down to the sea for food-making noises that keen everyone else awake, too. They stay for a few months.

HUNTING for invaders under the house, this family is helped by neighbors. Householders have M tried fencing and boarding around their houses, but still the penguins come to nest each year.

SIGNAL'S RIGHT, but the bus speeds on. For most people in Ocean Street, Narrabeen, the penguin novelty has worn off. They would rather have their sleep, which the birds' din disturbs. The noises vary from "woo-woo" to loud dog-like barks.

.jpg?timestamp=1619878478650)

THE MAN who came to dinner takes it for granted he's welcome as Mr. W. Gillanty greets him. Residents, particularly light sleepers, now have to resign themselves to a trying time while the penguins, which are protected, are in charge.

PENGUINS at the bottom of their garden (1956, December 12). The Australian Women's Weekly (1933 - 1982), p. 23. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article41852332

Marine Parade North Avalon resident and ornithologist Neville Cayley is mentioned in this one:

Two Little Penguins

AS Mr. Neville Cayley mentions in the 'Mail' that there is very little known regarding the length of time these penguins care for their young before turning them out, I thought the following account would be of especial interest to readers of 'Outdoor Australia.'

At a crowded Museum lecture Mr. Kinghorn told us this unusual incident. One morning towards the end of August, 1921, the peace and serenity of some dwellers at Collaroy Beach were disturbed by extraordinary noises and weird cries at the back door. When the astonished owner of the house opened the door in rushed two little penguins, which with loud voices announced their intentions of staying. Then they danced about and waved their little wings in a most ingratiating way. After a short time these noisy visitors were shown the door, and they disappeared for a while. But, having chosen their home, Mr. and Mrs. Penguin returned later, and as they could not get inside the house they went underneath as far as they could get, and there made their nest of seaweed. The noise every night was almost unbearable; they would scream and cackle, and later, after about six weeks their songs of joy were terrific, for two youngsters were hatched.

About four months after their arrival the penguin family suddenly departed. Where they wintered is their own secret: but late in the following August a terrible cackling outside advised these householders that they were back. When the door was opened Mr. and Mrs. Penguin marched triumphantly in, followed by two grown chicks, which were inquisitive and rather shy. Then followed extravagant dances of greeting and vociferous songs of 'Here we are again,' etc., in which the young ones also joined.

They could not be quietened, and the neighbours hastened across to see if someone had gone mad. The owners of the house put the whole family down on the beach and drove them away. It was then that the parents sent off the chicks to fend for themselves, and they themselves returned later and went under the house to their old nest. The celebrations were so overpowering that the householders took down some boards next day, got the noisy pair out, and drove them at night by car to Palm Beach, about twelve miles distant, and there left them. But next morning saw them back.

They were taken a second time, but returned, and were allowed lo stay; but a home was made for them in the far corner of the garden. The house side was netted off and a hole cut in the fence to allow them free access to the beach. They made a nest of seaweed, and later two eggs were laid. The birds look it in turn to sit on them, and there was always much shouting and scolding when one returned from the sea at night.

After about six weeks two sooty-brown chicks appeared, and the noise that night and the next few days while the celebrations lasted was tremendous. The parents took it in turn to fish and swim during the day that followed, but at night they often went out together to find a suitable supper, and about 9 p.m. would return, arguing together as they came up the beach. The following summer my father saw a young penguin land on the rocks at Coogee. I think it quite likely that it was one of the young ones turned out at Collaroy. It was evidently not very used to fending for itself, for a patch of feathers was torn from its shoulder, possibly through not being an adept at landing.

At the time of the lecture these queer visitors were still in residence at Collaroy, and what became of them I do not know. It is likely enough that the nesting-place on North Head mentioned by Mr. Cayley is occupied by these little penguins or their descendants. Outdoor Australia (1925, March 18).Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), , p. 10. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article159721727

It is recorded that two Fairy penguins for a number of years made seasonal visitations to Collaroy, near Sydney, and often laid their eggs under the floor of one of the houses there. — F.J.B. Quaint and Beautiful Sea Birds (1934, October 31). Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938), , p. 56. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article166107257

The Lion Island colony was officially first protected 65 years ago - although they had been protected decades prior to then:

PROTECTION OF PENGUINS.

Mr. Oakes (Chief Secretary), who is in charge of the Act relating to wild life, desires it to be generally known that all species of penguins are absolutely protected by law, and that anyone interfering with the birds is liable to a penalty. Apart from this he says citizens are requested to refrain from molesting this interesting bird, or driving it back to the sea, as, naturally, no water fowl liked getting wet when half-feathered.

Mr. Oakes remarked yesterday that fairy penguins, which were frequently seen off the coast, came ashore at this period of the year for moulting purposes for about three weeks. During that time they had not been observed to feed or enter the water. Many persons had offered specimens of the birds as exhibits to the Taronga Zoological Gardens, while others had made inquiries how to keep them alive in captivity. As this species of penguin only lived on live fish they could not be kept alive away from the sea. PROTECTION OF PENGUINS. (1923, December 18). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 8. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16127509

PENGUINS ON COAST ARE PROTECTED

A penguin caught to-day near Palm Beach v/as refused' by Zoo authorities. The birds are common along the coast at present, are protected by law, and do not live in captivity.

The secretary of the Zoo (Mr. H. B. Brown) said today that the public had been warned against molesting the birds. PENGUINS ON COAST ARE PROTECTED (1936, December 30). The Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 - 1954), p. 12 (COUNTRY EDITION). Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230907746

Surfers and people on boats report seeing them on an almost daily basis in our area. There is also a Fairy Penguin Colony at Manly.

The ladies from the Fix It Sisters community group have extended their project beyond Lion Island to the South Coast of NSW. In March 2021 they reported that:

Success at Snapper Island!

(This is part of the Eurobodalla Shire Council - which is on the South Coast of NSW)

Update on our Penguin Burrow project. Since installation of the first burrows at Snapper Island (Batemans Bay), some of the penguins have taken up residence and in 2020, gave birth to chicks. Exciting development for our burrow project.

In the meantime, FiS has been working hard in partnership with Pink Cactus on improving the design of the original burrows.

Fix It Sisters photo, March 16, 2021

Fix It Sisters photos, March 16, 2021

In 2019 the Eurobodalla Shire Council said:

The Snapper and the Tollgate Islands add scenic beauty to the idyllic seascape of Batemans Bay. Aside from their aesthetic value they hold another surprise which even locals are often unaware – breeding colonies of little penguins.

Eurobodalla Council’s invasive species supervisor Paul Martin said little penguins were the world’s smallest, up to 30cm tall, with an iridescent blue back, snow-white belly, and pink legs and feet.

Paul said the birds could spend days or even weeks at sea before returning to recover and enjoy island time between fishing trips.

“The penguins scrape out their love pads among the low-lying vegetation in early September. Mating, laying eggs, hatching chicks and teaching young penguins the way of the ocean takes until the end of summer,” Paul said.

“Because the eggs and chicks, hidden in vegetation, are so vulnerable to being stepped on, there is a no landing policy on these islands.”

Paul said the penguins local to Batemans Bay were found only on islands, where there were no cats, foxes, dogs or humans.

“About 15 percent of the this population live on Snapper Island, just a stone throw away from the Batemans Bay CBD, so we’re putting a lot of our efforts there,” he said.

“It’s not only the penguins at risk from visiting humans. Sooty oystercatchers – with their black plumage and bright orange bills – also nest on Snapper Island.

Paul said the ‘sooties’ were a threatened species that typically lay two eggs on a flat area just above the high water mark.

“The eggs look exactly like surrounding rocks and are easily stepped on when people walk the tideline around the island,” Paul said.

“The other big risk to both penguins and other shorebirds is entrapment; by plastic pollution like fishing line and drinking bottles or by weeds like kikuyu and turkey rhubarb. These vine-like weeds form loops and birds get entangled and eventually starve to death. That’s not a good way to go in anyone’s book.”

Paul said Council’s sustainability team and Landcare volunteers had commenced work on Snapper Island, clearing environmental weeds and plastic pollution and providing additional nesting opportunities for the little penguins.

“During the summer months, there is nothing better than a kayak paddle around Snapper Island,” Paul said. “However, to ensure our penguins and oystercatchers continue to breed here, Snapper Island is definitely a look but don’t land affair – take your binoculars for a closer view.”

Below runs a video this Council has put together on their Fairy Penguins. Just one of the birds we share our home with!

World Albatross Day Is June 19th

Black-browed Albatross (Thalassarche melanophrys) - pictures by A J Guesdon - taken while off the Pittwater shores

Why Fishing Club Has Been Wound Up.

The "curse” of an offended albatross is held responsible for the end of a deep-sea fishing club at Gosford, New South Wales. It began when the 24 men were fishing out at sea. One of them accidentally hooked a large albatross, the bird which is reputed to bring disaster if harmed as it did to the Ancient Mariner in Coleridge's poem. The bird fought savagely for half an hour before it could be brought aboard to have the hook extracted. Then it battled its way loose, and for three hours refused to leave the launch. Instead it viciously attacked first one and then another of the 24 men. At length it flew away, and the anglers sighed in relief. Their troubles, however, were only beginning.

An hour later, one of the men suffered agonies when a large fish hook became embedded deep in the palm of his hand. As the launch raced for the shore, the hook had to be prised out in an effort to reduce the man's suffering. Soon afterwards the launch grounded on a mudbank, and the men were marooned for three hours until the tide rose. Bad luck continued to dog every outing arranged by the club. Terrific storms prevented several trips. Club membership waned, and all efforts to revive interest failed. At the annual meeting the three remaining members of the original 120 have decided to wind up the club in an effort to avert the albatross “curse”. ALBATROSS “CURSE”. (1936, June 6). Shepparton Advertiser(Vic. : 1914 - 1953), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article176993041

The wise and lucky Black-browed Albatross (Thalassarche melanophrys) - Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds allied to the procellariids, storm petrelsand diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific. They are absent from the North Atlantic, although fossil remains show they once occurred there and occasional vagrants are found. Albatrosses are among the largest of flying birds, and the great albatrosses (genus Diomedea) have the largest wingspans of any extant birds, reaching up to 12 feet (3.7 m). The albatrosses are usually regarded as falling into four genera, but there is disagreement over the number of species.

The wise and lucky Black-browed Albatross (Thalassarche melanophrys) - Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds allied to the procellariids, storm petrelsand diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific. They are absent from the North Atlantic, although fossil remains show they once occurred there and occasional vagrants are found. Albatrosses are among the largest of flying birds, and the great albatrosses (genus Diomedea) have the largest wingspans of any extant birds, reaching up to 12 feet (3.7 m). The albatrosses are usually regarded as falling into four genera, but there is disagreement over the number of species.Albatrosses are highly efficient in the air, using dynamic soaring and slope soaring to cover great distances with little exertion. They feed on squid, fish and krill by either scavenging, surface seizing or diving. Albatrosses are colonial, nesting for the most part on remote oceanic islands, often with several species nesting together. Pair bonds between males and females form over several years, with the use of "ritualised dances", and will last for the life of the pair. A breeding season can take over a year from laying to fledging, with a single egg laid in each breeding attempt. A Laysan albatross, named Wisdom, on Midway Island is recognised as the oldest wild bird in the world; she was first banded in 1956 by Chandler Robbins.

Of the 22 species of albatrosses recognised by the IUCN, all are listed as at some level of concern; 3 species are Critically Endangered, 5 species are Endangered, 7 species are Near Threatened, and 7 species are Vulnerable. Numbers of albatrosses have declined in the past due to harvesting for feathers, but today the albatrosses are threatened by introduced species, such as rats and feral cats that attack eggs, chicks and nesting adults; by pollution; by a serious decline in fish stocks in many regions largely due to overfishing; and bylongline fishing. Longline fisheries pose the greatest threat, as feeding birds are attracted to the bait, become hooked on the lines, and drown. Stakeholders such as governments, conservation organisations and people in the fishing industry are all working toward reducing this bycatch.

In culture Albatrosses have been described as "the most legendary of all birds". An albatross is a central emblem in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge; a captive albatross is also a metaphor for the poète maudit in a poem of Charles Baudelaire. It is from the Coleridge poem that the usage of albatross as a metaphor is derived; someone with a burden or obstacle is said to have "an albatross around their neck", the punishment given in the poem to the mariner who killed the albatross. In part due to the poem, there is a widespread myth that (all) sailors believe it disastrous to shoot or harm an albatross; in truth, sailors regularly killed and ate them, e.g., as reported by James Cook in 1772. On the other hand, it has been reported that sailors caught the birds, but supposedly let them free again; the possible reason is that albatrosses were often regarded as the souls of lost sailors, so that killing them was supposedly viewed as bringing bad luck.

Birdwatching

Albatrosses are popular birds for birdwatchers and their colonies are popular destinations for ecotourists. Regular birdwatching trips are taken out of many coastal towns and cities, like Monterey, Kaikoura, Wollongong, Sydney, Port Fairy, Hobart and Cape Town, to see pelagic seabirds. Albatrosses are easily attracted to these sightseeing boats by the deployment of fish oil and burley into the sea. Visits to colonies can be very popular; the northern royal albatross colony at Taiaroa Head in New Zealand attracts 40,000 visitors a year, and more isolated colonies are regular attractions on cruises to subantarctic islands.

The black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), also known as the black-browed mollymawk, is a large seabird of the albatross family Diomedeidae; it is the most widespread and common member of its family. The origin of the name melanophris comes from two Greek words melas or melanos, meaning "black", and ophris, meaning "eyebrow", referring to dark feathering around the eyes.

The word mollymawk dates to the late 17th century, comes from the Dutch mallemok, which means mal – foolish and mok – gull.

The black-browed albatross is a medium-sized albatross, at 80 to 95 cm (31–37 in) long with a 200 to 240 cm wingspan and an average weight of 2.9 to 4.7 kg (6.4–10.4 lb). They can have a natural lifespan of over 70 years. It has a dark grey saddle and upperwings that contrast with the white rump, and underparts. The underwing is predominantly white with broad, irregular, black margins. It has a dark eyebrow and a yellow-orange bill with a darker reddish-orange tip. Juveniles have dark horn-colored bills with dark tips, and a grey head and collar. They also have dark underwings. The features that distinguish it from other mollymawks (except the closely related Campbell albatross) are the dark eyestripe which gives it its name, a broad black edging to the white underside of its wings, white head and orange bill, tipped darker orange. The Campbell albatross is very similar but with a pale eye. Immature birds are similar to grey-headed albatrosses but the latter have wholly dark bills and more complete dark head markings.

WRITTEN AT SEA, ABOARD THE "ANNE MILNE," OF DUNDEE.

With an eye as sedate as the eye of a sage,

And quick to discern what is passing below ;

With a pinion to cope with the hurricanes rage,

See the Albatross come, with his bosom of snow.

He comes where the bark, o'er the blue wave is bounding,

All music below, and all beauty above,

The emigrant's song, o'er the bright waters sounding,

The sails all a-breast to the breeze which they love !

He comes with the dawn, when the emigrant dreaming.

Is still with the friends of his heart and his home,

He leaves with the sun, when his golden rays streaming

O'er ocean and sky, make it rapture to roam.

He glides with a motion, majestic and grand,

The air never stirr'd by the wave of his wing,

And looks as if, born each bird to command,

As he sits on the ocean, enthroned like a king.

But in doubling the Cape, should the winds in their might,

Make the waves in the strength of their terror appear,

How sublime in the storm is the Albatross flight,

Like the spirit of faith, in the region of fear !

Around and across, o'er the wild breaking wave,

Where the Petrel, in hollows, shoots under his wing,

He soars undismayed, while the hearts of the brave,

Grow faint, as to perishing objects they cling !

The whale bird, in vigour, in habits and size,

Comes nearest the Albatross, but in the gale,

He shrinks from the contest, resigning the skies,

To his mightier rival, the great leathered whale.

J. G.

Original Poetry. (1849, February 24). Bathurst Advocate (NSW : 1848 - 1849), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62045380

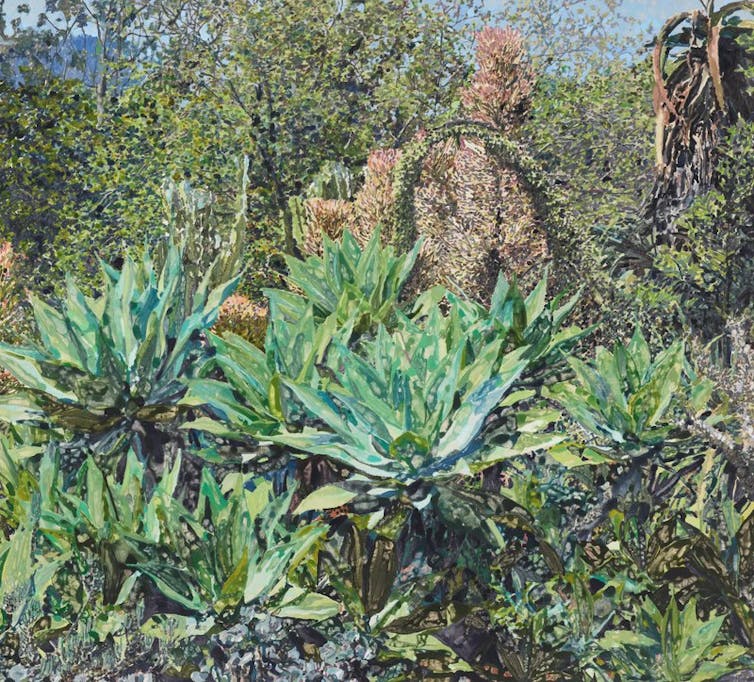

Logging Continues In The Areas The Swift Parrot Is Migrating To In NSW For Winter Feeding: Pittwater's Swamp Mahogany Tree A Food Source

Right now, Swift Parrots are migrating from Tasmania to mainland Australia.

Right now, Swift Parrots are migrating from Tasmania to mainland Australia. Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Mona Vale Dunes Planting Morning

Sydney Wildlife: Registrations For The Next Rescue And Care Course Are Now Open - Commences June 19, 2021

ORRCA News: 2021 Census Day - Sunday June 27

- This is a FREE event for all to join in.

- From sun up to sun down.

- Record all your sightings from your favourite whale watching location using an ORRCA data sheet and sending it into the team at the end of the day.

- Email orrcacensusday@gmail.com for all the details as they unfold.

Powering Ahead With Community Batteries

June 1, 2021

Community-scale batteries are already achievable in Australia, will complement existing household batteries and will allow more solar energy to be stored in our suburbs, analysis from The Australian National University (ANU) shows.

With the move towards community-scale batteries gathering pace across the nation, two new reports from ANU show the best way forward when it comes to their rollout.

The batteries have power capacity of around one megawatt (MW), or enough to power around 100 houses. They help "soak up" solar power generated during the day, improving reliability.

"They have the potential to play an integral role in Australia's transition to a decentralised grid by keeping generated energy close to where it will be used," project lead Dr Marnie Shaw from the ANU Battery Storage and Grid Integration Program (BSGIP) said.

"A key finding of our research is that current regulations could do more to encourage local management of rooftop solar and community battery uptake.

"As such, we propose a tariff that incentivises the use of energy, close to where that energy is produced.

"This 'Local Use of Service tariff' is essentially a price signal to customers, allowing them to benefit monetarily for storing and using energy locally."

The reports examined social aspects that drive the uptake of community batteries - including why people are either willing or unwilling to us them.

"We weighed up potential benefits and drawbacks of community-scale batteries," co-author Dr Hedda Ransan-Cooper said.

"Some risks are relatively easy to overcome, like ensuring safety measures in the event of a fire, while others, such as ensuring the benefits are fairly distributed, are more complicated."

Several community-scale battery projects are already underway across Australia.

The guidelines set out in the ANU reports will be applied in the Melbourne CBD as part of a partnership with the Yarra Energy Foundation and electricity network CitiPower. ANU will also be delivering tailored software for this trial.

"This will enable a trial of community batteries, or 'solar sponges' to be established in the CBD and inner-city suburbs of Melbourne," Dr Shaw said.

"It's clear that complex challenges around transitioning from a centralised to a decentralised energy system can really benefit from engineers and social scientists working together."

The ANU reports are available here and here.

.jpg?timestamp=1622607917640)

Port Kennedy community battery will enable residents to store their excess power. Photo: Western Power.

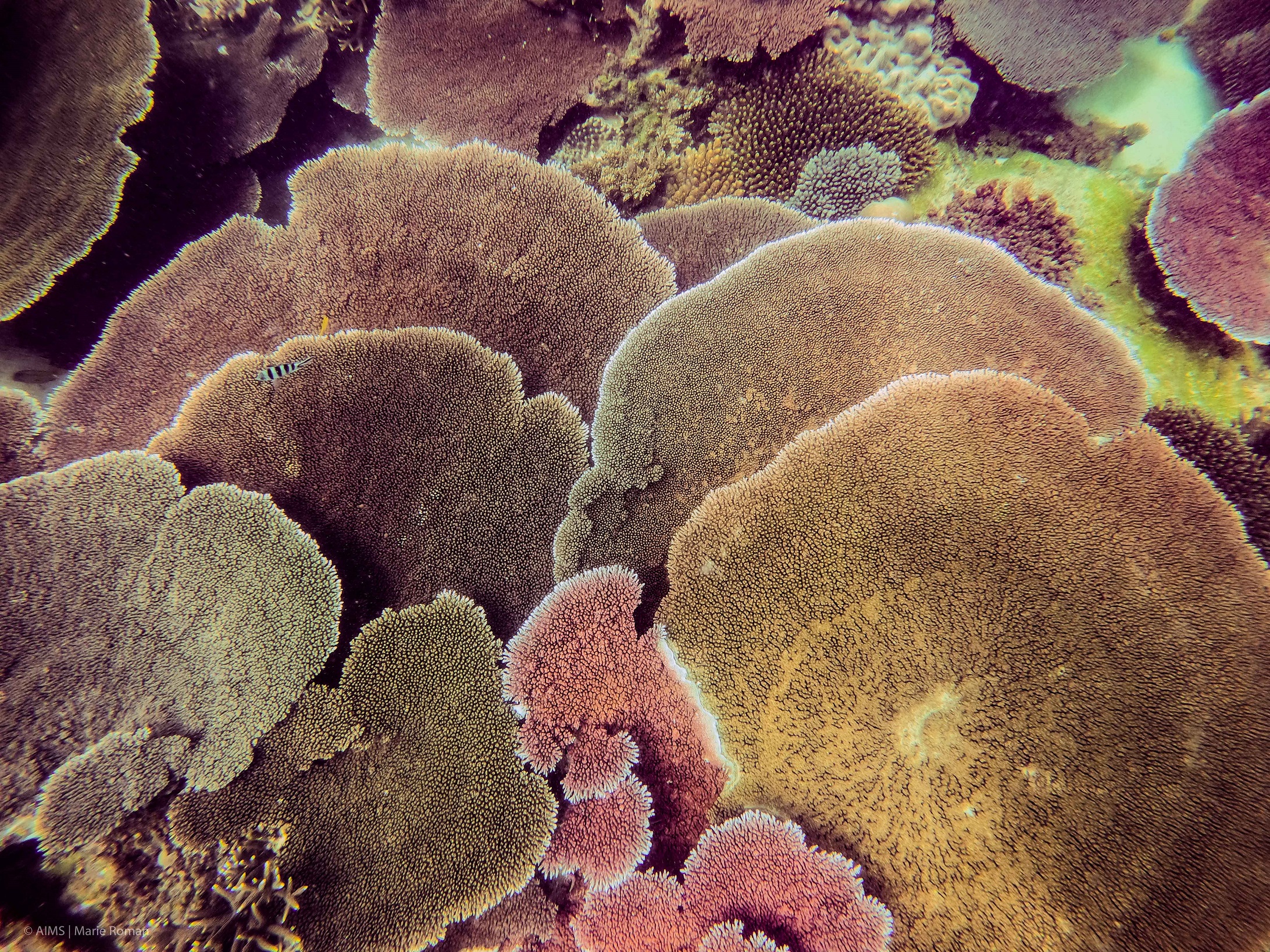

Turning The Tables - How Table Corals Are Regenerating Reefs

June 1, 2021

New research shows table corals can regenerate coral reef habitats on the Great Barrier Reef decades faster than any other coral type. The research suggests overall reef recovery would slow considerably if table corals declined or disappeared on the Great Barrier Reef. Table corals have been dubbed as "extraordinary ecosystem engineers" -- with new research showing these unique corals can regenerate coral reef habitats on the Great Barrier Reef faster than any other coral type.

The study highlights the importance of tabular Acropora, and is led by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) in collaboration with the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, the University of Queensland and The Nature Conservancy.

AIMS scientist and lead author Dr Juan Carlos Ortiz said the research showed overall reef recovery would slow considerably if table corals declined or disappeared on the Great Barrier Reef.

"Table corals are incredibly fast growing. Habitats in exposed reef slopes recover from disturbances at a rate 14 times higher -- that's more than two decades faster -- when table corals are abundant," he said.

"Their large, flat plate-like shape provides vital protection for large fish in shallow reef areas and serves as a shelter for small fishes, with some species almost entirely dependent on table corals.

"Even after death these corals provide value, as their skeletons are the preferred place for young corals of all types to settle."

Table corals, also known as plate corals, are mostly found in upper reef slopes exposed to wave action, at most mid-shelf and offshore reefs in the Great Barrier Reef.

The study found table corals to have unique combination of characteristics: they provided valuable ecological functions, are among the most sensitive coral types and, most importantly, their role was threatened by a low diversity of species which have this growth form.

The authors suggest protecting table corals could be an additional management focus. Targeting management to a particular coral type based on its ecosystem function -- rather than their risk of extinction alone -- would be ground-breaking in terms of ecosystem-based management.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority's Assistant Director and study co-author Dr Rachel Pears said table corals were fast growing and sensitive species.

"Table corals are still frequently seen on outer reefs, but their presence shouldn't be taken for granted as they are vulnerable to combined impacts," she said.

"These corals do not handle intensifying thermal stress well, are easily killed by anchor damage, highly susceptible to diseases, and are the preferred meal for crown-of-thorns starfish.

"The good news is there are tangible actions we can take to protect these corals such as targeted crown-of-thorns starfish control and anchoring restrictions."

University of Queensland's scientist and study co-author Professor Peter Mumby said while table corals promoted high rates of recovery, they did not necessarily bring high biodiversity.

"We know table corals do a big service for these reefs, but it's not a silver bullet for recovery," he said.

"Protecting table corals could be part of a suite of actions that look at reef recovery, with other management focused more specifically on protecting biodiversity."

Professor Mumby said it was also important to remember the biggest threat to the reef was climate change, and effective global action to reduce emissions significantly was paramount to protecting coral reefs.

The research drew on decades of data from AIMS long term monitoring program, revealing coral reef habitats took up to 32 years to recover, from 5% coral cover to 30% coral cover, where table corals had not recolonised after disturbances.

These low recovery rates were in stark contrast to reefs where table corals returned and recolonised, with these habitats recovering to 30% coral cover in just seven and a half years.

Given their extraordinary ecosystem function, the research indicated table corals should also be considered in restoration initiatives, like coral enhancement or assisted colonisation.

"Anyone who has been on the mid-shelf or offshore areas of the Great Barrier Reef would have seen table corals," Dr Ortiz said.

"We can think of table corals as the iconic charismatic 'mega coral' of the Great Barrier Reef, just like whales, turtles and dolphins are the Reef's iconic charismatic megafauna."

Juan C. Ortiz, Rachel J. Pears, Roger Beeden, Jen Dryden, Nicholas H. Wolff, Maria del C. Gomez Cabrera, Peter J Mumby. Important ecosystem function, low redundancy and high vulnerability: The trifecta argument for protecting the Great Barrier Reef's tabular Acropora. Conservation Letters, 2021 DOI: 10.1111/conl.12817

Image copyright: Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS)

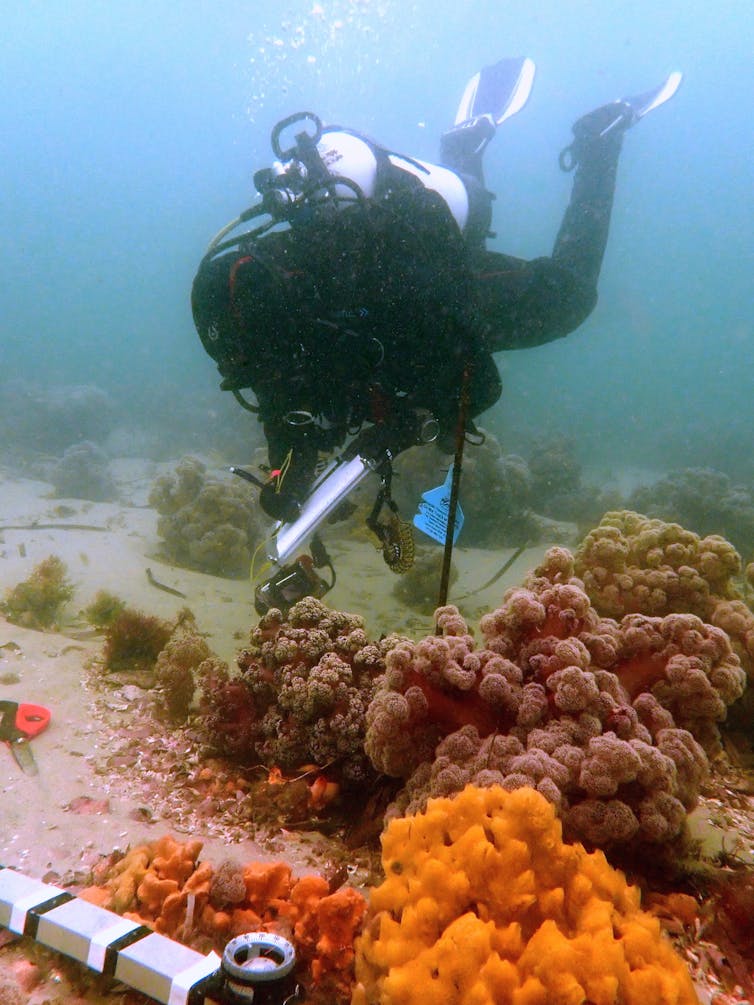

Beautiful, rare 'purple cauliflower' coral off NSW coast may be extinct within 10 years

When we think of Australia’s threatened corals, the Great Barrier Reef probably springs to mind. But elsewhere, coral species are also struggling – including a rare type known as “cauliflower soft coral” which is, sadly, on the brink of extinction.

This species, Dendronephthya australis, looks like a purple cauliflower due to its pink-lilac stems and branches, crowned with white polyps.

The coral primarily occurs at only a few sites in Port Stephens, New South Wales, and is a magnet for divers and underwater photographers. But sand movements, boating and fishing have reduced the species’ population dramatically.

Recent flooding in NSW compounded the problem – in fact, it may have reduced the remaining coral population by 90%. Our recent research found cauliflower soft coral may become extinct in the next decade unless we urgently protect and restore it.

Lilac Underwater Gardens

Cauliflower soft corals are predominantly found in estuarine environments on sandy seabeds with high current flow. They rely on tidal currents to transport plankton on which they feed.

The species is most commonly found in the Port Stephens estuary, about 200 kilometres north of Sydney. It’s also found in the Brisbane Water estuary in NSW, and has been found sporadically in other locations south to Jervis Bay.

The coral colonies form aggregations or “gardens”. At Port Stephens, these gardens are the preferred habitat for the endangered White’s seahorse and protected species of pipefish. They also support juvenile Australasian snapper, an important species for commercial and recreational fishers.

In recent months, the cauliflower soft coral has been listed as endangered in NSW and nationally.

An Alarming Decline

Scientists first mapped the distribution of the cauliflower soft coral in 2011. They found none of the biggest colonies in the Port Stephens estuary were protected by “no take” zones – areas where fishing and other extractive activities are banned.

In research in 2016, we found a sharp decline in the extent and distribution of cauliflower soft coral.

Our recent study examined the problem in more detail. It involved mapping the southern shoreline of Port Stephens, using an underwater camera towed by a vessel.

We found the cauliflower soft coral in the Port Stephens estuary has declined by almost 70% over just eight years. It now occurs over 9,300 square metres – down from 28,600 square metres in 2011.

Our subsequent modelling sought to identify what was driving the corals’ decline. We found a correlation between coral loss and sand movements over the last decade.

Human changes to shorelines, such as marina developments, have changed the dynamic of currents across the estuary. For example, previous research found a large influx of sand from the western end of Shoal Bay smothered cauliflower soft coral colonies at two nearby locations. As of 2018, those colonies had disappeared completely.

While diving as part of the project, we identified other causes of damage to the coral. Dropped boat anchors and the installation of moorings had damaged some colonies. Others were injured after becoming entangled in fishing line.

It is possible that disease, and pollution or other water quality issues, may also be contributing to the species’ decline.

Then The Floods Hit

Some 18 months after our most recent mapping, cauliflower soft corals suffered yet another blow. Major flooding in NSW in March this year caused a massive amount of fresh water to discharge from the Karuah River into the Port Stephens estuary, where sea water is dominant. Fresh water can kill cauliflower soft corals.

Following the floods, we conducted exploratory dives at locations where the cauliflower soft corals had been thriving at Port Stephens. We found much of the coral had disintegrated and disappeared. In fact, we estimated as much as 90% of the remaining cauliflower soft coral population was gone.

We plan to remap the estuary in the coming weeks, and feel confident our initial estimates will be close to the mark. If so, this means less than 5% of the species area mapped in 2011 now remains.

The floods also devastated kelp forests and other canopy-forming habitats in the estuary. Further work by scientists at the NSW Department of Primary Industries is underway to quantify these losses and monitor the recovery.

Urgent Work Required

The cauliflower soft coral urgently needs protecting. This will require ongoing, coordinated research and management.

Clearly, action must be taken to reduce threats such as anchoring, fishing, and development that may magnify sand movement.

Best-practice rehabilitation is also needed. This may involve rearing the coral off-site and transplanting it into suitable habitat. Such trials at Port Stephens have shown promising signs.

Human activities are causing species loss at an alarming rate. We must do everything in our power to prevent the extinction of the cauliflower soft coral, and other threatened species, to preserve the balance of nature and its ecosystems.

Read more: Australia's threatened species plan sends in the ambulances but ignores glaring dangers ![]()

Meryl Larkin, PhD Candidate, Southern Cross University; David Harasti, Adjunct assistant professor, Southern Cross University; Steve Smith, Professor of Marine Science, National Marine Science Centre, Southern Cross University, and Tom R Davis, Research Scientist - Marine Climate Change

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The APVMA’s Response To The Current Mouse Plague

- PER90579, issued 27 January 2021 to Cotton Australia Ltd for use on cotton (zinc phosphide).

- PER90846, issued 6 April 2021 to NSW DPI for use in fallow situations prior to sowing grain, legume, canola, safflower and nut crops, and use on pasture (zinc phosphide).

- PER90793, issued 9 April 2021 to Hoyle Trading Trust for use on grain, legume, canola, safflower and nut crops and use on pasture (zinc phosphide).

- PER90799, issued 7 May 2021 to Grain Producers Australia Ltd for use on grain, legume, canola, safflower and nut crops and use on pasture (zinc phosphide).

- PER91133, issued 26 May 2021 to Animal Control Technologies (Australia) Pty Ltd for use on grain crops, legume crops, canola, safflower, nut crops and pasture (zinc phosphide).

Hundreds Of Farmers Get In Early To Secure Free Mice-Killing Chemical

EPA Asks The Community To Use Pesticides Correctly When Baiting Mice

Mouse Plague Fuels Bird Deaths: Rodenticides Blamed For Avian Mortalities

Mouse Plague In Queensland And New South Wales: CSIRO

- Existing populations are increasing because they have access to good food and shelter.

- The cooler weather encourages mice to find shelter inside homes, making them more likely to be seen.

- Mouse numbers are in abundance following the breeding season and juvenile mice disperse to find other places to live.

- Try to reduce alternate food sources for mice and introduce livestock to eat excess food in the fields.

- Bait regularly and coordinate baiting with other farmers to avoid reinvasion. Bait on as broad a scale as possible.

- Lay bait when food source in the paddocks is at the lowest level, this will give mice the best chance to find the bait.

- Apply bait while sowing crops.

- Deny mice access to food sources. Clean up left-over pet food in bowls, bird aviaries and chicken runs.

- Keep grass mown and clean up around the garden. Remove anything that mice can shelter in. Move piles of wood and timber away from your house.

- Use snap traps, which takes away the need for chemicals.

Mouse plague: bromadiolone will obliterate mice, but it'll poison eagles, snakes and owls, too

It’s the smell that hits you first. The scent of urine and decomposing bodies. Then you notice other signs: scuttles and squeaks, small dead bodies leaking blood, tails sticking out of hubcaps.

If you’ve lived through a mouse plague, you’ve seen this, and smelled the stench of mice dying of poison baits.

As a desperate measure to help combat the mouse plague devastating rural communities across New South Wales, the state government yesterday secured 5,000 litres of bromadiolone. This is a bait that’s usually illegal to roll out at the proposed scale.

This is a bad idea. While bromadiolone effectively kills mice, it also travels up the food chain to poison predators who eat the mice, and other species. And these predators, from wedge-tailed eagles to goannas, are coming out in droves to feast on their abundant prey.

When Your Prey Is Everywhere

Animal plagues in Australia are fuelled by the “boom and bust” of rainfall.

We have natural, flood-driven population explosions of the native long-haired rat, with accompanying booms of letter-winged kites, their predator. We also have locust plagues when the conditions are right, leading to antechinus or mice plagues which eat the locusts.

Since at least the late 1800s, we’ve had terrible plagues of the introduced house mouse (Mus musculus). But rarely has it been this bad, with conditions currently seeming worse than the last plague in 2011, which caused over A$200 million in crop damage alone.

High numbers of birds of prey — nankeen kestrels, black-shouldered kites and barn owls — are often reported feasting on plague mice.

Snakes, goannas, native carnivores such as quolls, and feral cats and foxes, also take advantage of the abundant food. Pets, especially cats and some dogs, are highly likely to consume mice under these conditions, too.

Poisoning The Food Web

Laying out poison baits is one way people try to end mouse infestations and plagues. So-called “anticoagulant rodenticides” are divided into first and second generations, based on when they were first synthesised and the differences in potency.

Second generation anticoagulant rodenticides have higher toxicities than first generation, and are lethal after a single feed. First generation rodenticides, on the other hand, require rodents to feed on them for consecutive days to be lethal.

But mouse-eating predators are highly exposed to second generation rodenticides. For most animal species, the lethal doses of rodenticide aren’t yet known.

A scientific review from 2018 documented the poisoning of 31 bird, five mammal and one reptile species. Second generation aniticoaugulant rodenticides were implicated in the death of these animals.

Our research from 2020 found urban reptiles are highly exposed to second generation rodenticides, too. This includes mouse-eating snakes, called dugites, which had up to five different rodent poisons in them.

We also found poisons in frog-eating tiger snakes, and in omnivorous bobtail skinks which eat fruit, vegetation and snails. This is even more concerning because it shows how second generation rodenticides can saturate the entire foodweb, affecting everything from slugs to fish.

Bromadiolone Is Particularly Dangerous, Even To Humans

The NSW government secured bromadiolone baits as part of its $50 million mouse plague support package for regional communities.

Five thousand litres of the poison can treat around 95 tonnes of grain, and the government will provide it for free to primary producers once federal authorities approve its use.

Bromadiolone is usually restricted to use in and around buildings. But given the widespread impacts on wildlife, using bromadiolone at the proposed scale will do more harm than good.

Past research on bromadiolone has shown residues persist for up to 135 days in the carcasses of voles (another rodent species). In international studies, bromadiolone has been found in the livers of a host of birds of prey, including a range of owl species, red kites, sparrowhawks and golden eagles.

And it’s not just a problem for wildlife, humans are also at risk of exposure. For example, we can get exposed from eating eggs from chickens that feed on poisoned mice, or more directly from eating other animals that may have ingested poisoned mice.

A 2013 study looked at chicken eggs for human consumption, and detected bromadiolone in eggs between five and 14 days after the chicken ingested the poison. It’s not yet clear how many of these eggs we’d have to eat for us to get sick.

So What Are The Alternatives?

There are highly effective first generation rodenticides that provide viable solutions for managing mouse plagues. They may take a little longer to kill mice, but the upshot is they don’t stick around in the environment. A 2020 study found house mice in Perth didn’t have genetic resistance to first generation rodenticides, which suggests they’re effectively lethal.

Another approach has been to use zinc phosphide, a poison which is unlikely to secondarily poison other animals that eat the poisoned mice. However, zinc phosphide is still extremely toxic and will kill sheep, cows, pets and even humans if directly eaten.

Rolling out double-strength zinc phosphide may be the lesser of the evils in causing secondary poisoning, but only if used very carefully.

And another way to help control the mouse plague is to limit food resources for mice on farms. Farmers can minimise grain on ground, and Australia should invest in research for grain storage facilities that are less permeable to mice.

Mouse plagues are a regular cycle in Australia. Natural predators not only help create healthy, natural ecosystems, but also they help with mouse control. Second generation rodenticides will only destroy and weaken the predator populations we need to help us combat the next plague.![]()

Robert Davis, Senior Lecturer in Wildlife Ecology, Edith Cowan University; Bill Bateman, Associate professor, Curtin University; Damian Lettoof, PhD Candidate, Curtin University; Maggie J. Watson, Lecturer in Ornithology, Ecology, Conservation and Parasitology, Charles Sturt University, and Michael Lohr, Adjunct Lecturer, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sluggish Rehabilitation Rate At Upper Hunter Coal Mines Threatens Jobs And Environment

- Mount Arthur Independent Environmental Audit 2020 available here.

- Muswellbrook coal mine Independent Environmental Audit 2019 available here.

- Bengalla Independent Environmental Audit 2019 available here.

- Mount Pleasant Independent Environmental Audit 2020 available here.

Western Downs Farmers Call On Shell To Get Out Of Gas Following Dutch Ruling

ARENA Under Threat (Again): Federal Budget Against The Climate - Australian Conservation Foundation Analysis

- The government committed $100 million over four years to ocean sustainability initiatives, which ACF welcomes.

- $4.4 million over four years for a pilot biodiversity credit trading platform to encourage farmers to invest in biodiversity protection. ACF tentatively welcomes this but it’s critical that the program delivers genuine, long-term gains to biodiversity.

- $29.1m to protect native species from feral and invasive pests, but the budget projects a decline of 55% for on-ground biodiversity work from 2013 to 2025.

- $209.7m over four years was allocated to a new Australian Climate Service based in Townsville, Queensland that will bring together the Bureau of Meteorology, Geoscience Australia, CSIRO and Australian Bureau of Statistics to “anticipate and prepare for more extreme weather events”.

- $639m for “low emissions international technology partnerships” which may include developing a carbon offset scheme in the Indo-Pacific.

- They also allocated $302 million to major fuel refinery infrastructure upgrades to help bring forward, from 2027 to 2024, better quality fuels, including ultra-low sulfur levels.

- The budget papers include a commitment to the “full” rehabilitation of the former Rum Jungle uranium mine site near Batchelor, south of Darwin over the coming 11 years, but the funding amount was not revealed.

- Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation was allocated $59.8 million to ‘support the interim storage of intermediate level solid radioactive waste’. This funding aligns with the ACF’s call for Intermediary LW be kept in extended interim storage at ANSTO pending the outcome of a transparent review into the full range of long term management options.

- Hidden in the budget was $600 million for government-owned Snowy Hydro Limited to construct a 660 MW gas-fired power station at Kurri Kurri in NSW.

- Also not clear in the budget but revealed last week, two refineries will receive up to $2.047 billion to minimise the downside price risks of production by the government guaranteeing to step in and set a price.

- $29.3 million over four years to implement fast-tracked processes for the environmental assessments of development projects under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act which have not yet been agreed to by the parliament, and that ACF strongly opposes.

- A total of $58.6m was allocated to the gas industry (including $38.7m directly to gas infrastructure) including:

- a one-off grant of up to $30 million for billionaire Andrew Forrest's firm Australian Industrial Power to back its 635MW gas import and dual gas and hydrogen fuel processing project at Port Kembla in New South Wales;

- gas storage facilities at Golden Beach and Iona in Victoria;

- the expansion of the South West Victorian Pipeline;

- the Wallumbilla Gas Supply Hub in Queensland ($6.2 million over two years);

- a pipeline pre-feasibility study for the North Bowen Basin in Queensland.

- $539.2m was allocated to five hydrogen hubs ($275.5m) and carbon capture and storage ($263.7m).

- $217m to upgrade roads in the Northern Territory linked to gas in and around the Beetaloo Basin.

- $279.9m over a decade to establish a “below baseline crediting mechanism” to encourage major polluters to reduce their energy consumption and emissions. How this mechanism works in practice will be key to it actually reducing emissions.

- $100 million over four years to advance the flawed and contested plan for a Nuclear Waste Storage Facility at Kimba in rural South Australia.

- The budget revealed the fuel tax credit subsidy, which allows multinational mining companies like Rio Tinto, BHP and Glencore to pay zero tax on their off-road diesel use, will cost Australians $35.5 billion across the forward estimates.

Banks Must Respond To IEA Warning On Gas Financing

EPA Fines Liddell Power Station Operator For Alleged Air Pollution

New Plan To Revitalise NSW's Oldest Park By Installing Mountain Bike Trails

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park, Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Planning Considerations

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Plan of Management

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Mountain Biking Plan

Pumped Hydro Plan Will Help To Maintain Lithgow’s Place As An Energy Hub

- Big battery. Neon is building a big battery on the site of the decommissioned Wallerawang power station site. [1]

- Eco-precinct. An eco-precinct is also planned for the Wallerawang power station site. [2]

- Bus manufacturing. The Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils is lobbying to establish an electric bus manufacturing plant in Lithgow. [3]

- Pumped hydro. Energy Australia announces plans for pumped hydro. [4]

EnergyAustralia Excited About Pumped Hydro Possibility Near Mt Piper

Previously: Mt Piper Power Station Energy Recovery Feasibility

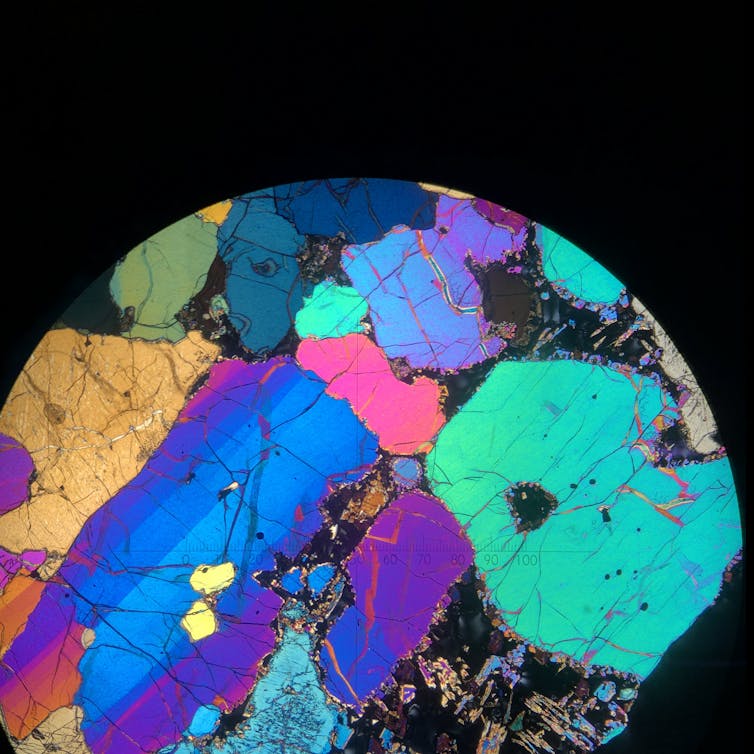

Hundreds of Australian lizard species are barely known to science. Many may face extinction

Most of the incredible diversity of life on Earth is yet to be discovered and documented. In some groups of organisms – terrestrial arthropods such as spiders and scorpions, marine invertebrates such as sponges and molluscs, and others – scientists have described fewer than 20% of species.

Even our knowledge of more familiar creatures such as fish and reptiles is far from complete. In our new research, we studied 1,034 known species of Australian lizards and snakes and found we know so little about 164 of them that not even the experts know whether they are fully described or not. Of the remaining 870, almost a third probably need some work to be described properly.

Documenting and naming what species are out there – the work of taxonomists – is crucial for conservation, but it can be difficult for researchers to decide where to focus their efforts. Alongside our lizard research, we have developed a new “return on investment” approach to identify priority species for our efforts.

We identified several hotspots across Australia where research is likely to be rewarded. More broadly, our approach can help target taxonomic research for conservation worldwide.

Why We Need To Look At Species More Closely

As more and more species are threatened by land clearing, climate change and other human activities, our research highlights that we are losing even more biodiversity than we know.

Conservation often relies on species-level assessments such as those conducted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, which lists threatened species. Although new species are being discovered all the time, a key problem is that already named “species” may harbour multiple undocumented and unnamed species. This hidden diversity remains invisible to conservation assessment.

One such example are the Grassland Earless Dragons (Tympanocryptis spp.) found in the temperate native grasslands of south-eastern Australia. These small secretive lizards were grouped within a single species (Tympanocryptis pinguicolla) and listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

But recent taxonomic research split this single species into four, each occurring in an isolated region of grasslands. One of these new species may represent the first extinction of a reptile on mainland Australia and the other three have a high probability of being threatened.

Read more: Why we're not giving up the search for mainland Australia's 'first extinct lizard'

Scientists call documenting and describing species “taxonomy”. Our research shows the importance of prioritising taxonomy in the effort to conserve and protect species.

Taxonomists At Work

Many government agencies do take some account of groups smaller than species in their conservation efforts, such as distinct populations. But these are often ambiguously defined and lack formal recognition, so they are not widely used. That’s where taxonomists come in, to identify species and describe them fully.

Our new research was a collaboration of 30 taxonomists and systematists, who teamed up to find a good way of working out which species should be a priority for taxonomic research for conservation outcomes. This new approach compares the amount of work needed with the likelihood of finding previously unknown species that are at risk of extinction.

The research team, who are experts on the taxonomy and systematics of Australia’s reptiles, implemented this new approach on Australian lizards and snakes. This group of reptiles is ideal as a test case because Australia is a global hotspot of lizard diversity – and we also have a strong community of taxonomic experts.

Australia’s Lizards And Snakes

Of the 1,034 Australian lizard and snake species, we were able to assess whether 870 of them may contain undescribed species. This means we know so little about the remaining 164 species that even the experts could not make an informed opinion on whether they contain hidden diversity. There is so much still to learn!

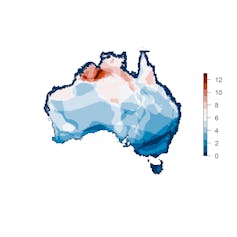

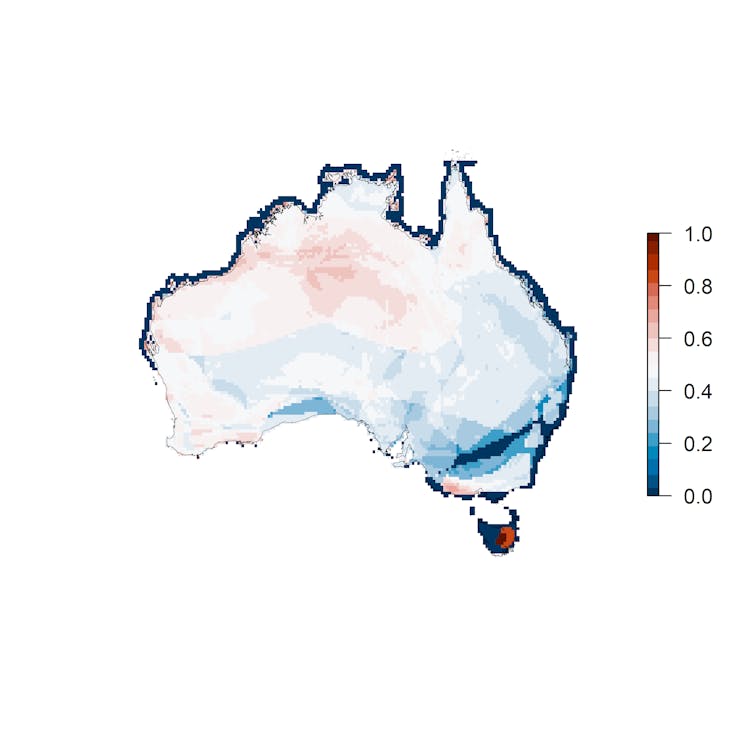

Of the 870 species experts could assess, they determined 282 probably or definitely needed more taxonomic research. Mapping the distributions of these species indicated hotspot regions for this taxonomic research, including the Kimberley, the Tanami Desert region, western Victoria and offshore islands (such as Tasmania, Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands). Some areas in the Kimberley region had more than 60 species that need further taxonomic research.

We found 17.6% of the 282 species that need more taxonomic research contained undescribed species that would probably be of conservation concern, and 24 had a high probability of being threatened with extinction. Taxonomists know that there are undescribed species because there is some data available already but the description of these species – the process of defining and naming – has not been done.

These high-priority species belong to a range of families including geckos, skinks and dragons found across Australia.

The high number of undescribed species, especially those with significant likelihood of being endangered, was a shock to even the experts. The IUCN currently estimates only 6.3% of Australian lizards and snakes require taxonomic revision, but this is obviously a significant underestimate.

A Race Against Extinction

Beyond lizards, there is a huge backlog of species awaiting description.

Recent projects have used genetic analyses to discover unknown species, including a $180 million global BIOSCAN effort aiming to identify millions of new species. However, genetics is only a first step in the formal recognition of species.

The taxonomic process of documenting, describing and naming species requires multiple further steps. These steps include a comprehensive diagnostic assessment using a combination of evidence, such as genetics and morphology, to uniquely distinguish each species from another. This process requires a high level of familiarity and scholarship of the group in question.

Among the Australian lizards and snakes alone, there is a backlog of 59 undescribed species for which only the final elements of taxonomic research are awaiting completion.

To work through these taxonomic backlogs – let alone species that are so far entirely unknown – resources need to be invested in taxonomy, including research funding and increased provision of viable career paths.

Without taxonomic research, the conservation assessment of these undocumented species will not proceed. There are untold numbers of species needing taxonomic research that are already under threat of extinction. If we don’t hurry, they may go extinct before we even know they exist.![]()

Jane Melville, Senior Curator, Terrestrial Vertebrates, Museums Victoria and Reid Tingley, Lecturer, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

About 500,000 Australian species are undiscovered – and scientists are on a 25-year mission to finish the job

Here are two quiz questions for you. How many species of animals, plants, fungi, fish, insects and other organisms live in Australia? And how many of these have been discovered and named?

To the first, the answer is we don’t really know. But the best guess of taxonomists – the scientists who discover, name, classify and document species – is that Australia’s lands, rivers, coasts and oceans probably house more than 700,000 distinct species.

On the second, taxonomists estimate almost 200,000 species have been scientifically named since Europeans first began exploring, collecting and classifying Australia’s remarkable fauna and flora.

Together, these estimates are disturbing. After more than 300 years of effort, scientists have documented fewer than one-third of Australia’s species. The remaining 70% are unknown, and essentially invisible, to science.

Taxonomists in Australia name an average 1,000 new species each year. At that rate, it will take at least 400 years to complete even a first-pass stocktake of Australia’s biodiversity.

This poor knowledge is a serious threat to Australia’s environment. And a first-of-its kind report released today shows it’s also a huge missed economic opportunity. That’s why today, Australia’s taxonomists are calling on governments, industry and the community to support an important mission: discovering and documenting all Australian species within 25 years.

Australia: A Biodiversity Hotspot

Biologically, Australia is one of the richest and most diverse nations on Earth – between 7% and 10% of all species on Earth occur here. It also has among the world’s highest rates of species discovery. But our understanding of biodiversity is still very, very incomplete.

Of course, First Nations peoples discovered, named and classified many species within their knowledge systems long before Europeans arrived. But we have no ready way yet to compare their knowledge with Western taxonomy.

Finding new species in Australia is not hard - there are almost certainly unnamed species of insects, spiders, mites and fungi in your backyard. Any time you take a bush holiday you’ll drive past hundreds of undiscovered species. The problem is recognising the species as new and finding the time and resources to deal with them all.

Taxonomists describe and name new species only after very careful due diligence. Every specimen must be compared with all known named species and with close relatives to ensure it is truly a new species. This often involves detailed microscopic studies and gene sequencing.

More fieldwork is often needed to collect specimens and study other species. Specimens in museums and herbaria all over the world sometimes need to be checked. After a great deal of work, new species are described in scientific papers for others to assess and review.

So why do so many species remain undiscovered? One reason is a shortage of taxonomists trained to the level needed. Another is that technologies to substantially speed up the task have only been developed in the past decade or so. And both these, of course, need appropriate levels of funding.

Of course, some groups of organisms are better known than others. In general, noticeable species – mammals, birds, plants, butterflies and the like – are fairly well documented. Most less noticeable groups - many insects, fungi, mites, spiders and marine invertebrates - remain poorly known. But even inconspicuous species are important.

Fungi, for example, are essential for maintaining our natural ecosystems and agriculture. They fertilise soils, control pests, break down litter and recycle nutrients. Without fungi, the world would literally grind to a halt. Yet, more than 90% of Australian fungi are believed to be unknown.

Read more: How we discovered a hidden world of fungi inside the world’s biggest seed bank

Mind The Knowledge Gap

So why does all this matter?

First, Australia’s biodiversity is under severe and increasing threat. To manage and conserve our living organisms, we must first discover and name them.

At present, it’s likely many undocumented species are becoming extinct, invisibly, before we know they exist. Or, perhaps worse, they will be discovered and named from dead specimens in our museums long after they have gone extinct in nature.

Second, many undiscovered species are crucial in maintaining a sustainable environment for us all. Others may emerge as pests and threats in future; most species are rarely noticed until something goes wrong. Knowing so little about them is a huge risk.

Third, enormous benefits are to be gained from these invisible species, once they are known and documented. A report released today by Deloitte Access Economics, commissioned by Taxonomy Australia, estimates a benefit to the national economy of between A$3.7 billion and A$28.9 billion if all remaining Australian species are documented.

Benefits will be greatest in biosecurity, medicine, conservation and agriculture. The report found every $1 invested in discovering all remaining Australian species will bring up to $35 of economic benefits. Such a cost-benefit analysis has never before been conducted in Australia.

The investment would cover, among other things, research infrastructure, an expanded grants program, a national effort to collect specimens of all species and new facilities for gene sequencing.

Read more: A few months ago, science gave this rare lizard a name – and it may already be headed for extinction

Mission Possible

Australian taxonomists – in museums, herbaria, universities, at the CSIRO and in government departments – have spent the last few years planning an ambitious mission to discover and document all remaining Australian species within a generation.

So, is this ambitious goal achievable, or even imaginable? Fortunately, yes.

It will involve deploying new and emerging technologies, including high-throughput robotic DNA sequencing, artificial intelligence and supercomputing. This will vastly speed up the process from collecting specimens to naming new species, while ensuring rigour and care in the science.

A national meeting of Australian taxonomists, including the young early career researchers needed to carry the mission through, was held last year. The meeting confirmed that with the right technologies and more keen and bright minds trained for the task, the rate of species discovery in Australia could be sped up by the necessary 16-fold – reducing 400 years of effort to 25 years.

With the right people, technologies and investment, we could discover all Australian species. By 2050 Australia could be the world’s first biologically mega-rich nation to have documented all our species, for the direct benefit of this and future generations.

Read more: Hundreds of Australian lizard species are barely known to science. Many may face extinction ![]()

Kevin Thiele, Adjunct Assoc. Professor, The University of Western Australia and Jane Melville, Senior Curator, Terrestrial Vertebrates, Museums Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

'Green steel' is hailed as the next big thing in Australian industry. Here's what the hype is all about

Steel is a major building block of our modern world, used to make everything from cutlery to bridges and wind turbines. But the way it’s made – using coal – is making climate change worse.

On average, almost two tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO₂) are emitted for every tonne of steel produced. This accounts for about 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Cleaning up steel production is clearly key to Earth’s low-carbon future.

Fortunately, a new path is emerging. So-called “green steel”, made using hydrogen rather than coal, represents a huge opportunity for Australia. It would boost our exports, help offset inevitable job losses in the fossil fuel industry and go a long way to tackling climate change.

Australia’s abundant and cheap wind and solar resources mean we’re well placed to produce the hydrogen a green steel industry needs. So let’s take a look at how green steel is made, and the challenges ahead.

Steeling For Change

Steel-making requires stripping oxygen from iron ore to produce pure iron metal. In traditional steel-making, this is done using coal or natural gas in a process that releases CO₂. In green steel production, hydrogen made from renewable energy replaces fossil fuels.

Australia exports almost 900 million tonnes of iron ore each year, but only makes 5.5 million tonnes of steel. This means we have great capacity to ramp up steel production.

A Grattan Institute report last year found if Australia captured about 6.5% of the global steel market, this could generate about A$65 billion in annual export revenue and create 25,000 manufacturing jobs in Queensland and New South Wales.

Steel-making is a complex process and is primarily achieved via one of three processes. Each of them, in theory, can be adapted to produce green steel. We examine each process below.

Read more: Australia could fall apart under climate change. But there's a way to avoid it

1. Blast Furnace

Globally, about 70% of steel is produced using the blast furnace method.

As part of this process, processed coal (also known as coke) is used in the main body of the furnace. It acts as a physical support structure for materials entering and leaving the furnace, among other functions. It’s also partially burnt at the bottom of the furnace to both produce heat and make carbon monoxide, which strips oxygen from iron ore leaving metallic iron.

This coal-driven process leads to CO₂ emissions. It’s feasible to replace a portion of the carbon monoxide with hydrogen. The hydrogen can strip oxygen away from the ore, generating water instead of CO₂. This requires renewable electricity to produce green hydrogen.

And hydrogen cannot replace carbon monoxide at a ratio of 1:1. If hydrogen is used, the blast furnace needs more externally added heat to keep the temperature high, compared with the coal method.

More importantly, solid coal in the main body of the furnace cannot be replaced with hydrogen. Some alternatives have been developed, involving biomass – a fuel developed from living organisms – blended with coal.

But sourcing biomass sustainably and at scale would be a challenge. And this process would still likely create some fossil-fuel derived emissions. So to ensure the process is “green”, these emissions would have to be captured and stored – a technology which is currently expensive and unproven at scale.

Read more: Australians want industry, and they'd like it green. Steel is the place to start

2. Recycled Steel

Around 30% of the world’s steel is made from recycled steel. Steel has one of the highest recycling rates of any material.

Steel recycling is mainly done in arc furnaces, driven by electricity. Each tonne of steel produced using this method produces about 0.4 tonnes of CO₂ – mostly due to emissions produced by burning fossil fuels for electricity generation. If the electricity was produced from renewable sources, the CO₂ output would be greatly reduced.

But steel cannot continuously be recycled. After a while, unwanted elements such as copper, nickel and tin begin to accumulate in the steel, reducing its quality. Also, steel has a long lifetime and low turnover rate. This means recycled steel cannot meet all steel demand, and some new steel must be produced.

3. Direct Reduced Iron

“Direct reduced iron” (DRI) technology often uses methane gas to produce hydrogen and carbon monoxide, which are then used to turn iron ore into iron. This method still creates CO₂ emissions, and requires more electricity than the blast furnace method. However its overall emission intensity can be substantially lower.

The method currently accounts for less than 5% of production, and offers the greatest opportunity for using green hydrogen.

Up to 70% of the hydrogen derived from methane could be replaced with green hydrogen without having to modify the production process too much. However work on using 100% green hydrogen in this method is ongoing.

Read more: For hydrogen to be truly 'clean' it must be made with renewables, not coal

Becoming A Green Steel Superpower

The green steel transition won’t happen overnight and significant challenges remain.

Cheap, large-scale green hydrogen and renewable electricity will be required. And even if green hydrogen is used, to achieve net-zero emissions the blast furnace method will still require carbon-capture and storage technologies – and so too will DRI, for the time being.

Private sector investment is needed to create a global-scale export industry. Australian governments also have a big role to play, in building skills and capability, helping workers retrain, funding research and coordinating land-use planning.

Revolutionising Australia’s steel industry is a daunting task. But if we play our cards right, Australia can be a major player in the green manufacturing revolution.![]()

Jessica Allen, Senior Lecturer and DECRA Fellow, University of Newcastle and Tom Honeyands, Director, Centre for Ironmaking Materials Research, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Peter Wegner’s portrait of Guy Warren at 100 wins the 100th Archibald Prize

The artist Guy Warren gave the best summary of this year’s centenary Archibald Prize, telling the crowd assembled for the official announcement: “It’s a lot of fun”.

Appropriately, as well as praising Peter Wegner, whose portrait of the centenarian won this year’s Archibald Prize, Warren congratulated the many artists whose works hang alongside his likeness.