inbox and environment news: Issue 498

June 13 - 19, 2021: Issue 498

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Mona Vale Dunes Planting Morning

Sydney Wildlife: Registrations For The Next Rescue And Care Course Are Now Open - Commences June 19, 2021

World Albatross Day Is June 19th

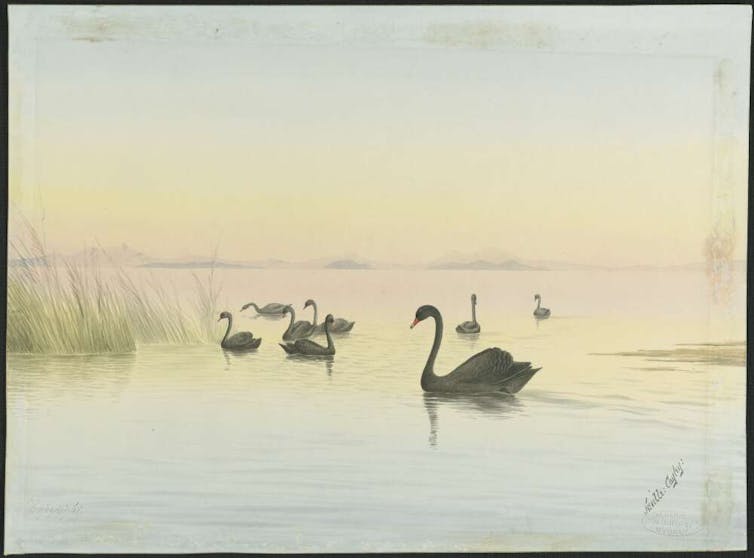

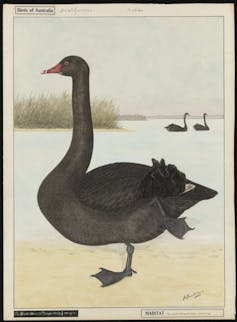

Black-browed Albatross (Thalassarche melanophrys) - pictures by A J Guesdon - taken while off the Pittwater shores

Why Fishing Club Has Been Wound Up.

The "curse” of an offended albatross is held responsible for the end of a deep-sea fishing club at Gosford, New South Wales. It began when the 24 men were fishing out at sea. One of them accidentally hooked a large albatross, the bird which is reputed to bring disaster if harmed as it did to the Ancient Mariner in Coleridge's poem. The bird fought savagely for half an hour before it could be brought aboard to have the hook extracted. Then it battled its way loose, and for three hours refused to leave the launch. Instead it viciously attacked first one and then another of the 24 men. At length it flew away, and the anglers sighed in relief. Their troubles, however, were only beginning.

An hour later, one of the men suffered agonies when a large fish hook became embedded deep in the palm of his hand. As the launch raced for the shore, the hook had to be prised out in an effort to reduce the man's suffering. Soon afterwards the launch grounded on a mudbank, and the men were marooned for three hours until the tide rose. Bad luck continued to dog every outing arranged by the club. Terrific storms prevented several trips. Club membership waned, and all efforts to revive interest failed. At the annual meeting the three remaining members of the original 120 have decided to wind up the club in an effort to avert the albatross “curse”. ALBATROSS “CURSE”. (1936, June 6). Shepparton Advertiser(Vic. : 1914 - 1953), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article176993041

The wise and lucky Black-browed Albatross (Thalassarche melanophrys) - Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds allied to the procellariids, storm petrelsand diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific. They are absent from the North Atlantic, although fossil remains show they once occurred there and occasional vagrants are found. Albatrosses are among the largest of flying birds, and the great albatrosses (genus Diomedea) have the largest wingspans of any extant birds, reaching up to 12 feet (3.7 m). The albatrosses are usually regarded as falling into four genera, but there is disagreement over the number of species.

The wise and lucky Black-browed Albatross (Thalassarche melanophrys) - Albatrosses, of the biological family Diomedeidae, are large seabirds allied to the procellariids, storm petrelsand diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific. They are absent from the North Atlantic, although fossil remains show they once occurred there and occasional vagrants are found. Albatrosses are among the largest of flying birds, and the great albatrosses (genus Diomedea) have the largest wingspans of any extant birds, reaching up to 12 feet (3.7 m). The albatrosses are usually regarded as falling into four genera, but there is disagreement over the number of species.Albatrosses are highly efficient in the air, using dynamic soaring and slope soaring to cover great distances with little exertion. They feed on squid, fish and krill by either scavenging, surface seizing or diving. Albatrosses are colonial, nesting for the most part on remote oceanic islands, often with several species nesting together. Pair bonds between males and females form over several years, with the use of "ritualised dances", and will last for the life of the pair. A breeding season can take over a year from laying to fledging, with a single egg laid in each breeding attempt. A Laysan albatross, named Wisdom, on Midway Island is recognised as the oldest wild bird in the world; she was first banded in 1956 by Chandler Robbins.

Of the 22 species of albatrosses recognised by the IUCN, all are listed as at some level of concern; 3 species are Critically Endangered, 5 species are Endangered, 7 species are Near Threatened, and 7 species are Vulnerable. Numbers of albatrosses have declined in the past due to harvesting for feathers, but today the albatrosses are threatened by introduced species, such as rats and feral cats that attack eggs, chicks and nesting adults; by pollution; by a serious decline in fish stocks in many regions largely due to overfishing; and bylongline fishing. Longline fisheries pose the greatest threat, as feeding birds are attracted to the bait, become hooked on the lines, and drown. Stakeholders such as governments, conservation organisations and people in the fishing industry are all working toward reducing this bycatch.

In culture Albatrosses have been described as "the most legendary of all birds". An albatross is a central emblem in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge; a captive albatross is also a metaphor for the poète maudit in a poem of Charles Baudelaire. It is from the Coleridge poem that the usage of albatross as a metaphor is derived; someone with a burden or obstacle is said to have "an albatross around their neck", the punishment given in the poem to the mariner who killed the albatross. In part due to the poem, there is a widespread myth that (all) sailors believe it disastrous to shoot or harm an albatross; in truth, sailors regularly killed and ate them, e.g., as reported by James Cook in 1772. On the other hand, it has been reported that sailors caught the birds, but supposedly let them free again; the possible reason is that albatrosses were often regarded as the souls of lost sailors, so that killing them was supposedly viewed as bringing bad luck.

Birdwatching

Albatrosses are popular birds for birdwatchers and their colonies are popular destinations for ecotourists. Regular birdwatching trips are taken out of many coastal towns and cities, like Monterey, Kaikoura, Wollongong, Sydney, Port Fairy, Hobart and Cape Town, to see pelagic seabirds. Albatrosses are easily attracted to these sightseeing boats by the deployment of fish oil and burley into the sea. Visits to colonies can be very popular; the northern royal albatross colony at Taiaroa Head in New Zealand attracts 40,000 visitors a year, and more isolated colonies are regular attractions on cruises to subantarctic islands.

The black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), also known as the black-browed mollymawk, is a large seabird of the albatross family Diomedeidae; it is the most widespread and common member of its family. The origin of the name melanophris comes from two Greek words melas or melanos, meaning "black", and ophris, meaning "eyebrow", referring to dark feathering around the eyes.

The word mollymawk dates to the late 17th century, comes from the Dutch mallemok, which means mal – foolish and mok – gull.

The black-browed albatross is a medium-sized albatross, at 80 to 95 cm (31–37 in) long with a 200 to 240 cm wingspan and an average weight of 2.9 to 4.7 kg (6.4–10.4 lb). They can have a natural lifespan of over 70 years. It has a dark grey saddle and upperwings that contrast with the white rump, and underparts. The underwing is predominantly white with broad, irregular, black margins. It has a dark eyebrow and a yellow-orange bill with a darker reddish-orange tip. Juveniles have dark horn-colored bills with dark tips, and a grey head and collar. They also have dark underwings. The features that distinguish it from other mollymawks (except the closely related Campbell albatross) are the dark eyestripe which gives it its name, a broad black edging to the white underside of its wings, white head and orange bill, tipped darker orange. The Campbell albatross is very similar but with a pale eye. Immature birds are similar to grey-headed albatrosses but the latter have wholly dark bills and more complete dark head markings.

WRITTEN AT SEA, ABOARD THE "ANNE MILNE," OF DUNDEE.

With an eye as sedate as the eye of a sage,

And quick to discern what is passing below ;

With a pinion to cope with the hurricanes rage,

See the Albatross come, with his bosom of snow.

He comes where the bark, o'er the blue wave is bounding,

All music below, and all beauty above,

The emigrant's song, o'er the bright waters sounding,

The sails all a-breast to the breeze which they love !

He comes with the dawn, when the emigrant dreaming.

Is still with the friends of his heart and his home,

He leaves with the sun, when his golden rays streaming

O'er ocean and sky, make it rapture to roam.

He glides with a motion, majestic and grand,

The air never stirr'd by the wave of his wing,

And looks as if, born each bird to command,

As he sits on the ocean, enthroned like a king.

But in doubling the Cape, should the winds in their might,

Make the waves in the strength of their terror appear,

How sublime in the storm is the Albatross flight,

Like the spirit of faith, in the region of fear !

Around and across, o'er the wild breaking wave,

Where the Petrel, in hollows, shoots under his wing,

He soars undismayed, while the hearts of the brave,

Grow faint, as to perishing objects they cling !

The whale bird, in vigour, in habits and size,

Comes nearest the Albatross, but in the gale,

He shrinks from the contest, resigning the skies,

To his mightier rival, the great leathered whale.

J. G.

Original Poetry. (1849, February 24). Bathurst Advocate (NSW : 1848 - 1849), p. 4. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62045380

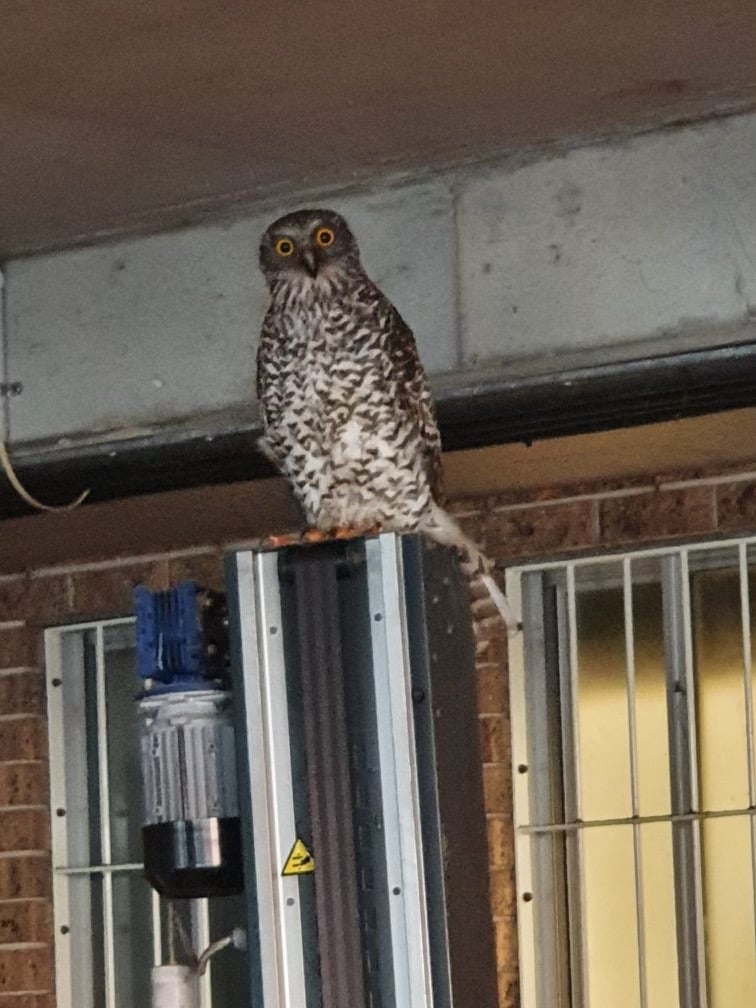

The Powerful Owl Project Update

ORRCA News: 2021 Census Day - Sunday June 27

- This is a FREE event for all to join in.

- From sun up to sun down.

- Record all your sightings from your favourite whale watching location using an ORRCA data sheet and sending it into the team at the end of the day.

- Email orrcacensusday@gmail.com for all the details as they unfold.

Koala Takes Up Residence In Partially Built House

Whitehaven Pleads Guilty To Stealing One Billion Litres Of Water During Drought

NSW Planning Department Refers Hume Coal Project To IPC For Second Time

EPA Fines Bluescope Steel For Alleged Water Pollution

Please, don't look away. The NSW flood recovery will take years and people still need our help

Extreme flooding in New South Wales in March triggered a two-week frenzy of media interest. But while the camera crews and journalists have since moved on, communities still face a long recovery.

Many flood-ravaged homes have not yet been repaired and others are infested with mould. Farmers are struggling to fix damaged infrastructure, while dealing with weed outbreaks and the memories of livestock killed in traumatic circumstances.

I’m a water scientist with a growing interest in post-flood recovery, and recently visited several flood-affected areas in NSW. In the Hawkesbury-Nepean River I found nutrient-heavy and contaminated water. In the Southern Highlands, minor flooding persists and many fallen trees and damaged fences remain. And near the Gwidyr River at Moree, as elsewhere, crops and roads remain damaged and weeds are thriving.

Some communities were grappling with the effects of bushfire, drought and COVID-19 before the floods hit. And some flood-affected areas are now also dealing with a mouse plague. In these most difficult circumstances, it’s worth looking at the practical recovery actions most likely to help and the long-term challenges ahead.

Yet Another Farming Crisis

Many farmers have months of work ahead to recover from the floods. Some lost livestock to flood waters; cattle were found washed up on beaches, in trees, on streets and in neighbours’ backyards. Farmers spoke of their trauma after hearing the helpless bellows of their drowning cows.

The loss of livestock is a major blow after years of drought. And booming stock prices means buying sheep and cattle to rebuild herds is expensive.

Adding to post-flood stress for farmers, they must be extra vigilant about protecting their livestock from disease. Flystrike, cattle ticks and internal parasites can thrive in wet conditions, and persist long after waters recede.

The floods ruined thousands of kilometres of fences and destroyed crops and pastures. In some cases, nutrient-rich flood waters transported weeds to new areas, or caused dormant seeds in the soil to sprout weeds.

When The Mould Takes Hold

The floods caused a wider range of damage to properties than many people realise. Common repairs needed include replacing floor coverings, fixing electrical wiring and plumbing, new insulation and extensive replacement of internal walls and house cladding.

Many homes, schools and businesses are still waiting for repairs. This is a common problem after floods. Six months after the disastrous 2019 Townsville floods, for example, a combination of slow insurance payouts and shortage of tradesmen meant only 1,400 of 3,300 damaged homes had been repaired.

In NSW, some flood-hit homes are currently battling mould . This microscopic fungi penetrates internal walls and ceilings as well as furnishings. In some cases, it is growing in wall cavities, posing an “invisible” health risk.

Mould can be wiped away from impenetrable surfaces such as glass, tiles and metal. But once absorbed by porous building materials, such as plywood, chipboard and plasterboard, mould can be nearly impossble to remove and the materials must be replaced.

Seek expert advice from your local council’s environmental health officers to deal with large areas of mould. It may be possible to clean up small areas of mould yourself, but use protective equipment. Mould can be a health hazard, and breathing it in can trigger asthma, even in people without an existing allergy.

Read more: Floods leave a legacy of mental health problems — and disadvantaged people are often hardest hit

Insurance Woes

By the end of March this year, some 11,700 insurance claims for flood damage had been submitted, and the number was expected to grow.

After natural disasters, people often find their insurance policy does not cover the damage, or their claim is rejected. If you’re struggling with an insurance claim, independent help is available.

The problem of under- or non-insurance is likely to worsen under climate change. Climate Council research shows one in every 19 property owners face the prospect of unaffordable insurance premiums by 2030. Flood-prone properties near rivers are particularly at risk.

Separate research has also linked insurance disputes and rejected claims to depression among disaster victims.

Insurance problems add to the financial stress of lost earnings and flood damage repairs. Flood-affected individuals and businesses currently requiring financial support can seek help from governments, local councils and charities.

Read more: 'We always come last': Deaf people are vulnerable to disaster risk but excluded from preparedness

Playing The Long Game

Six years after the 2011 Brisbane floods, a survey of 327 victims found they continued to suffer adverse physical and mental health effects. The impacts can be worse for people already suffering chronic diseases.

And many people – particularly those living in disadvantage before the floods – have barely begun the recovery process. Some are relying on food vouchers, or living without essential items such as fridges and washing machines.

Local councils are also struggling. In the Northern Rivers, roads remain damaged by floods, leaving multimillion-dollar repair bills.

After a string of catastrophic disasters in recent years, the Australian public may well be suffering from “compassion fatigue”. That’s understandable. But flood victims clearly still need our help.

If you can, donate to the ABC NSW Flood Appeal. And if you’re one of the people struggling, remember you’re not alone. Your fellow Australians do care and there are many avenues for assistance. Please don’t hesitate to ask for it.

This story is part of a series on the nexus between disaster, disadvantage and resilience. It is supported by a philanthropic grant from the Paul Ramsay Foundation. Read the rest of the coverage here.![]()

Ian Wright, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Science, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New Outback Reserve To Protect Diverse Western Wilderness

- Langidoon and Metford Stations lie in the far west of NSW, 65 km east of Broken Hill, within the Broken Hill Complex Bioregion. It lies along the Barrier Highway.

- The properties contain a diversity of broad ecosystems supporting Acacia shrublands on sandplains and on stony desert, gibber chenopod shrublands and floodplain woodland associated with ephemeral watercourses.

- Size: 60,468 hectares (Landgidoon at 35,554 ha and Metford at 24,914.19 ha).

- Bioregional significance: Langidoon and Metford make a significant contribution to a comprehensive, adequate and representative reserve system by:

- Increasing the level of protection for Broken Hill Complex Bioregion from 3.45% to 4.42%.

- Protecting an area of two subregions. The Barrier Ranges subregion, characterised by steep, low rocky ranges is not sampled in the national park estate; and the Barrier Range Outwash subregion has only 0.4% reserved in the national park estate. This subregion is characterised by stream channels and floodplains, low angle alluvial fans and floodouts, extending to extensive sandplains and dunefields with lakes and claypans.

- Protecting 7 landscape types. Three (Barrier Salt Lakes and Playas; Barrier Tablelands and Barrier Fresh Lakes and Swamps) are not protected in any other national park and one (Barrier Downs) is effectively unprotected at 0.02 per cent reserved.

- Ecosystems: The land contains a diversity of ecosystems – 33 Plant Community Types (PCTs) are mapped, of which 25 are effectively unreserved at the bioregional level.

- Over 30% of the land comprises Acacia loderi shrublands – an endangered TEC (Threatened ecological community). In New South Wales, the community is mainly confined to south western NSW with the major stands occurring between Broken Hill, Ivanhoe and Wilcannia, while only isolated stands occur beyond these areas.

- Threatened species: provides potential habitat for at least 14 threatened fauna species, mainly birds.

- Threatened species are likely to include the Australian Bustard, white-fronted chat, pink cockatoo, blue-billed duck and freckled duck

- Wetlands: includes Eckerboon Lake (160 ha) which during times of flooding provide habitat for migratory bird species.

- Aboriginal heritage: artefacts associated with ephemeral Eckerboon Lake.

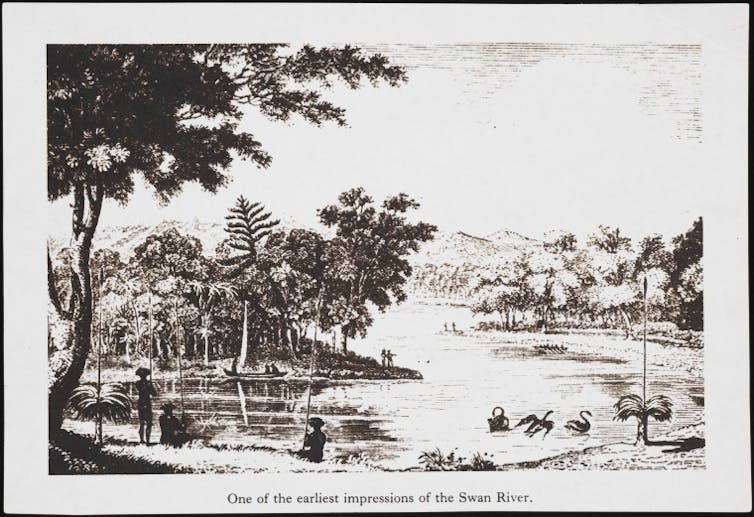

- Contemporary history: Little Topar on the Metford property hosted the 'roo shooting scene' for 1971 movie Wake in Fright starring Jack Thompson, Chips Rafferty and John Meillon (among others).

Australian First Keeps Waterways Clean

Bellinger Riverwatch To Count Waterbugs In Snapping Turtle River

Conserving Coastal Seaweed: A Must Have For Migrating Sea Birds

As Australia officially enters winter, UniSA ecologists are urging coastal communities to embrace all that the season brings, including the sometimes-unwelcome deposits of brown seaweed that can accumulate on the southern shores.

As Australia officially enters winter, UniSA ecologists are urging coastal communities to embrace all that the season brings, including the sometimes-unwelcome deposits of brown seaweed that can accumulate on the southern shores.Clean Bill Of Health For Macquarie Island Marine Life

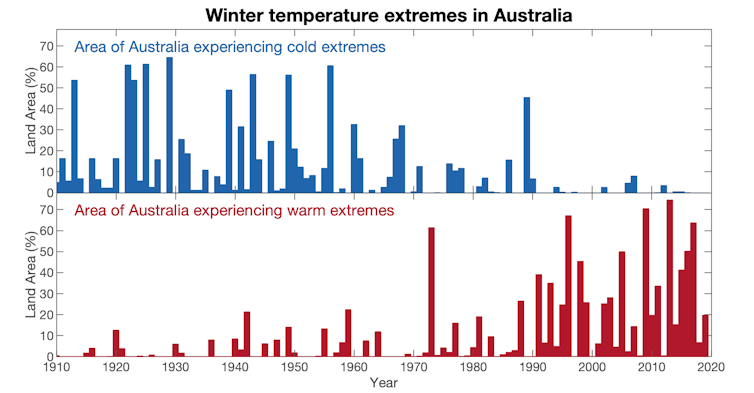

Matt Canavan suggested the cold snap means global warming isn't real. We bust this and 2 other climate myths

Senator Matt Canavan sent many eyeballs rolling yesterday when he tweeted photos of snowy scenes in regional New South Wales with a sardonic two-word caption: “climate change”.

Canavan, a renowned opponent of climate action and proponent of the coal industry, appeared to be suggesting that the existence of an isolated cold snap means global warming isn’t real.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has previously insisted there is “no dispute in this country about the issue of climate change, globally, and its effect on global weather patterns”. But Canavan’s tweet would suggest otherwise.

The reality is, as the climate warms, record-breaking cold weather is becoming less common. And one winter storm does not negate more than a century of human-caused global warming. Here, we take a closer look at the cold weather misconception and two other common climate change myths.

Myth #1: A Cold Snap Means Global Warming Isn’t Happening

Canavan’s tweet is an example of a common tactic used by climate change deniers that deliberately conflates weather and climate.

Parts of Australia are currently in the grip of a cold snap as icy air from Antarctica is funnelled up over the eastern states. This is part of a normal weather system, and is temporary.

Climate, on the other hand, refers to weather conditions over a much longer period, such as several decades. And as our climate warms, the probability of such weather systems bringing record-breaking cold temperatures reduces dramatically.

Just as average temperatures in Australia have risen markedly over the past century, so too have winter temperatures. That doesn’t mean climate change is not happening. In a warming world, extremely cold winter temperatures can still occur, but less often than they used to.

In fact, human-caused climate change means extreme winter warmth now occurs more often, and across larger parts of the country. Record-breaking hot events in Australia now far outweigh record breaking cold events.

Myth #2: Global Warming Is Good For Us

Yes, climate change may bring isolated benefits. For example, warmer global temperatures may mean fewer people die from extreme cold weather, or that shorter shipping routes open up across the Arctic as sea ice melts.

But the perverse benefits that may flow from climate change will be far outweighed by the damage caused.

Extreme heat can be fatal for humans. And a global study found 37% of heat-related deaths are a direct consequence of human-caused climate change. That means nearly 3,000 deaths in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne between 1991 and 2018 were due to climate change.

Extreme heat and humidity may make some parts of the world, especially those near the Equator, essentially uninhabitable by the end of this century.

Global warming also kills plants, animals and ecosystems. In 2018, an estimated one-third of Australia’s spectacled flying foxes died when temperatures around Cairns reached 42℃. And there is evidence many Australian plants will not cope well in a warmer world – and are already nearing their tipping point.

Heatwaves also damage oceans. The Great Barrier Reef has suffered three mass bleaching events in just five years. Within decades the natural wonder is unlikely to exist in is current form – badly hurting employment and tourism.

Read more: Climate change is making ocean waves more powerful, threatening to erode many coastlines

Myth #3: More CO₂ Means Earth Will Definitely Get Greener

In January last year, News Corp columnist Andrew Bolt caused a stir with an article that suggested rising carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions were “greening the planet” and were therefore “a good thing”.

During photosynthesis, plants absorb CO₂. So as the concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere increases, some researchers predict the planet will become greener and crop yields will increase.

Consistent with this hypothesis, there is indirect evidence of increased global photosynthesis and satellite-observed greening. There is also indirect evidence of increased “carbon sinks”, whereby CO₂ is drawn down from the atmosphere by plants, then stored in soil.

Rising temperatures lead to an earlier onset of spring, as well as prolonged summer plant growth – particularly in the Northern Hemisphere. Researchers think this has triggered an increase in the land carbon sink.

However, there’s also widespread evidence some trees are not growing as might be expected given the increased CO₂ levels in our atmosphere. For example, a study of how Australian eucalypts might respond to future CO₂ concentrations has so far found no increase in growth.

Increased plant growth may also cause them to use more water, causing significant reductions in streamflow that will compound water availability issues in dry regions.

Overall, attempts to reconcile the various lines of evidence of how climate change will alter Earth’s land vegetation have proved challenging.

So, Are We Doomed?

After all this bad news, you might be feeling a bit dejected. And true, the current outlook isn’t great.

Earth has already warmed by about 1℃, and current policies have the world on track for at least 3℃ warming this century. But there is still reason for hope. While every extra bit of warming matters, so too does every action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

And there are promising signs of increasing ambition to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on the global front – from the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Japan and others.

Unfortunately, Australia is far behind our international peers, instead pushing the burden of action onto future generations. We now need the political leadership to set our country, and the world, on a safer and more secure path. Ill-informed tweets by senior members of the government only set back the cause.

Nerilie Abram, Professor; ARC Future Fellow; Chief Investigator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes; Deputy Director for the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science, Australian National University; Martin De Kauwe, Senior lecturer, UNSW, and Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick, ARC Future Fellow, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Next 20 Are Years Crucial In Determining The Future Of Coal

New Population Of Pygmy Blue Whales Discovered With Help Of Bomb Detectors

Blue whales may be the biggest animals in the world, but they're also some of the hardest to find. Not only are they rare (it's estimated that less than 0.15 per cent of blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere survived whaling), they're also reclusive by nature and can cover vast areas of ocean. But now, a team of scientists led by UNSW Sydney are confident they've discovered a new population of pygmy blue whales, the smallest subspecies of blue whales, in the Indian Ocean.

Blue whales may be the biggest animals in the world, but they're also some of the hardest to find. Not only are they rare (it's estimated that less than 0.15 per cent of blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere survived whaling), they're also reclusive by nature and can cover vast areas of ocean. But now, a team of scientists led by UNSW Sydney are confident they've discovered a new population of pygmy blue whales, the smallest subspecies of blue whales, in the Indian Ocean.Ocean Microplastics: First Global View Shows Seasonal Changes And Sources

Maori Connections To Antarctica May Go As Far Back As 7th Century

Indigenous Maori people may have set eyes on Antarctic waters and perhaps the continent as early as the 7th century, new research published in the peer-reviewed Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand shows. Over the last 200 years, narratives about the Antarctic have been of those carried out by predominantly European male explorers.

Indigenous Maori people may have set eyes on Antarctic waters and perhaps the continent as early as the 7th century, new research published in the peer-reviewed Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand shows. Over the last 200 years, narratives about the Antarctic have been of those carried out by predominantly European male explorers.Tasmania's reached net-zero emissions and 100% renewables – but climate action doesn't stop there

Getting to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and 100% renewable energy might seem the end game for climate action. But what if, like Tasmania, you’ve already ticked both those goals off your list?

Net-zero means emissions are still being generated, but they’re offset by the same amount elsewhere. Tasmania reached net-zero in 2015, because its vast forests and other natural landscapes absorb and store more carbon each year than the state emits.

And in November last year, Tasmania became fully powered by renewable electricity, thanks to the island state’s wind and hydro-electricity projects.

The big question for Tasmania now is: what comes next? Rather than considering the job done, it should seize opportunities including more renewable energy, net-zero industrial exports and forest preservation – and show the world what the other side of net-zero should look like.

A Good Start

The Tasmanian experience shows emissions reduction is more straightforward in some places than others.

The state’s high rainfall and mountainous topography mean it has abundant hydro-electric resources. And the state’s windy north is well suited to wind energy projects.

What’s more, almost half the state’s 6.81 million hectares comprises forest, which acts as a giant carbon “sink” that sucks up dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere.

Given Tasmania’s natural assets, it makes sense for the state to go further on climate action, even if its goals have been met.

Read more: Net-zero, carbon-neutral, carbon-negative ... confused by all the carbon jargon? Then read this

The Tasmanian government has gone some way to recognising this, by legislating a target of 200% renewable electricity by 2040.

Under the target, Tasmania would produce twice its current electricity needs and export the surplus. It would be delivered to the mainland via the proposed A$3.5 billion Marinus Link cable to be built between Tasmania and Victoria. The 1,500 megawatt cable would bolster the existing 500 megawatt Basslink cable.

But Tasmania’s climate action should not stop there.

Other Opportunities Await

Tasmania can use its abundant renewable electricity to decarbonise existing industrial areas. It can also create new, greener industrial precincts – clusters of manufacturers powered by renewable electricity and other zero-emissions fuels such as green hydrogen.

Zero-emission hydrogen, aluminium and other goods produced in these precincts will become increasingly sought after by countries and other states with their own net-zero commitments.

Tasmania’s vast forests could be an additional source of economic value if they were preserved and expanded, rather than logged. As well as supporting tourism, preserving forests could enable Tasmania to sell carbon credits to other jurisdictions and businesses seeking to offset their emissions, such as through the federal government’s Emissions Reduction Fund.

The ocean surrounding Tasmania also presents net-zero economic opportunities. For example, local company Sea Forest is developing a seaweed product to be added to the feed of livestock, dramatically reducing the methane they emit.

Concrete Targets Are Needed

The Tasmanian government has commissioned a review of its climate change legislation, and is also revising its climate change action plan.

These updates give Tasmania a chance to be a global model for a post-net-zero world. But without firm action, Tasmania risks sliding backwards.

While having reached net-zero, the state has not legislated or set a requirement to maintain it. The state’s current legislated emission target is a 60% reduction by 2050 on 1990 levels – which, hypothetically, means Tasmania could increase its emissions in future.

Also, despite reaching net-zero emissions, Tasmania still emits more than 8.36 million tonnes of CO₂ each year from sources such as transport, natural gas use, industry and agriculture. Tasmania’s emissions from all sectors other than electricity and land use have increased by 4.5% since 2005.

Without a net-zero target set in law – and a plan to stay there – these emissions could overtake those drawn down by Tasmania’s forests. In fact, a background paper prepared for the Tasmanian government shows the state’s emissions may rise in the coming years and stay “positive” until 2040 or later.

The legislation update should also include a process to set emissions targets for each sector of the economy, as Victoria has done. It should also set ambitious targets for “negative” emissions – which means sequestering more CO₂ than is emitted.

Action On All Fronts

Under the Paris Agreement, the world is pursuing efforts to limit global warming to 1.5℃ this century. For Australia to be in line with this goal, it must reach net-zero by the mid-2030s.

Meeting this momentous task requires action on all fronts, in all jurisdictions. Bigger states and territories are aiming for substantial emissions reductions this decade. Tasmania must at least keep its emissions net-negative, and decrease them further.

Tasmania has a golden opportunity. With the right policies, the state can solidify its climate credentials and create a much-needed economic boost as the world transitions to a low-carbon future.![]()

Rupert Posner, Systems Lead - Sustainable Economies, ClimateWorks Australia and Simon Graham, Senior Analyst, ClimateWorks Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tracking the transition: the ‘forgotten’ emissions undoing the work of Australia's renewable energy boom

World leaders including Prime Minister Scott Morrison will gather in the UK this weekend for the G7 summit. In a speech on Wednesday ahead of the meeting, Morrison said Australia recognises the need to reach net-zero emissions in order to tackle climate change, and expects to achieve the goal by 2050.

So has Australia started the journey towards deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions?

In the electricity supply system, the answer is yes, as renewables form an ever-greater share of the electricity mix. But elsewhere in the energy sector – in transport, industry and buildings – there has been little or no progress.

This situation needs to change. These other parts of the energy system contribute nearly 40% of all national greenhouse gas emissions – and the share is growing. In a new working paper out today, we propose a way to track the low-carbon transition across the energy sector and check progress over the last decade.

A Stark Contrast

The energy sector can be separated into three major types of energy use in Australia:

- electricity generation

- transport and mobile equipment used in mining, farming, and construction

- all other segments, mainly fossil fuel combustion to provide heat in industry and buildings.

In 2018-19, energy sector emissions accounted for 72% of Australia’s national total. Transition from fossil fuels to zero-emissions sources is at the heart of any strategy to cut emissions deeply.

The transition is already happening in electricity generation, as wind and solar supplies increase and coal-fired power stations close or operate less.

But in stark contrast, elsewhere in the sector there is no evidence of a meaningful low-emissions transition or acceleration in energy efficiency improvement.

This matters greatly because in 2019, these other segments contributed 53% of total energy combustion emissions and 38% of national greenhouse gas emissions. Total energy sector emissions increased between 2005 (the reference year for Australia’s Paris target) and 2019.

As the below graphic shows, while the renewables transition often gets the credit for Australia’s emissions reductions, falls since 2005 are largely down to changes in land use and forestry.

Let’s take a closer look at the areas where Australia could do far better in future.

1. Transport And Mobile Equipment

Transport includes road and rail transport, domestic aviation and coastal shipping. Mobile equipment includes machinery such as excavators and dump trucks used in mining, as well as tractors, bulldozers and other equipment used in farming and construction. Petroleum supplies almost 99% of the energy consumed by these machines.

Road transport is responsible for more than two-thirds of all the energy consumed by transport and mobile equipment.

What’s more, prior to COVID, energy use by transport and mobile equipment was steadily growing – as were emissions. The absence of fuel efficiency standards in Australia, and a trend towards larger cars, has contributed to the problem.

Electric vehicles offer great hope for cutting emissions from the transport sector. As Australia’s electricity grid continues to decarbonise, emissions associated with electric vehicles charged from the grid will keep falling.

2. Other Energy Emissions

Emissions from all other parts of the energy system arise mainly from burning:

- gas to provide heat for buildings and manufacturing, and for the power needed to liquefy gas to make LNG

- coal, for a limited range of heavy manufacturing activities, such as steel and cement production

- petroleum products (mainly LPG) in much smaller quantities, where natural gas is unavailable or otherwise unsuitable.

Emissions from these sources, as a share of national emissions, rose from 13% in 2005 to 19% in 2019.

These types of emissions can be reduced through electrification – that is, using low- or zero-carbon electricity in industry and buildings. This might include using induction cooktops, and electric heat pumps to heat buildings and water.

However the data offer no evidence of such a shift. Fossil fuel use in this segment has declined, but mainly due to less manufacturing activity rather than cleaner energy supply.

And in 2018 and 2019, the expanding LNG industry drove further emissions growth, offsetting the decline in use of gas and coal in manufacturing.

How To Track Progress

Over the past decade or so, Australia’s emissions reduction policies – such as they are – have focused on an increasingly narrow range of emission sources and reduction opportunities, in particular electricity generation.

Only now are electric vehicles beginning to be taken seriously, while energy efficiency – a huge opportunity to cut emissions and costs – is typically ignored.

Our paper proposes a large set of new indicators, designed to show what’s happening (and not happening) across the energy sector.

The indicators fall into four groups:

greenhouse gas emissions from energy use

primary fuel mix including for electricity generation

final energy consumption including energy use efficiency

the fuel/technology mix used to deliver energy services to consumers.

Our datasets excludes the effects of 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns. They’re based on data contained in established government publications: The Australian Energy Statistics, the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory and the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ national accounts and population estimates.

By systematically tracking and analysing these indicators, and combining them with others, Australia’s energy transition can be monitored on an ongoing basis. This would complement the great level of detail already available for electricity generation. It would also create better public understanding and focus policy attention on areas that need it.

In some countries, government agencies monitor the energy transition in great detail. In some cases, such as Germany, independent experts also conduct systematic and substantial analysis as part of an annual process.

The Road Ahead

Australia has begun the journey to a zero-emissions energy sector. But we must get a move-on in transport, industry and buildings.

The technical opportunities are there. What’s now needed is government regulation and policy to encourage investment in zero-emissions technologies for both supplying and using all forms of energy.

And once available, the technology should be deployed now and in coming years, not in the distant future.

Read more: Check your mirrors: 3 things rooftop solar can teach us about Australia's electric car rollout ![]()

Hugh Saddler, Honorary Associate Professor, Centre for Climate Economics and Policy, Australian National University and Frank Jotzo, Director, Centre for Climate and Energy Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New Plan To Revitalise NSW's Oldest Park By Installing Mountain Bike Trails

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park, Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Planning Considerations

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Plan of Management

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Mountain Biking Plan

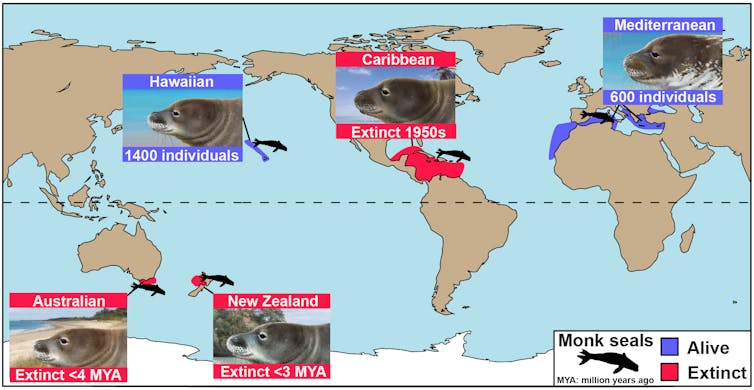

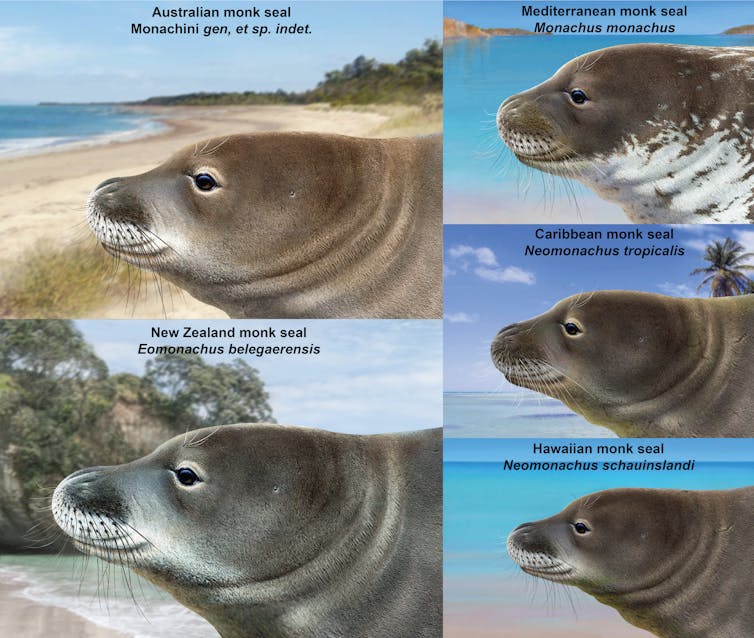

The most endangered seals in the world once called Australia home

Monk seals are one of the most endangered marine mammals alive today, with just over 2,000 individuals remaining in the wild. These seals live in warm waters, specifically the tropics and the Mediterranean.

Hunting by sailors in the past resulted in the extinction of the Caribbean monk seal by the end of the 1950s. It also heavily reduced the numbers of the two remaining populations, in Hawaii and the Mediterranean.

Given how rare monk seals are today, it is hard to imagine a time when they were abundant. However, fossils from Australia show monk seals used to be much more widespread.

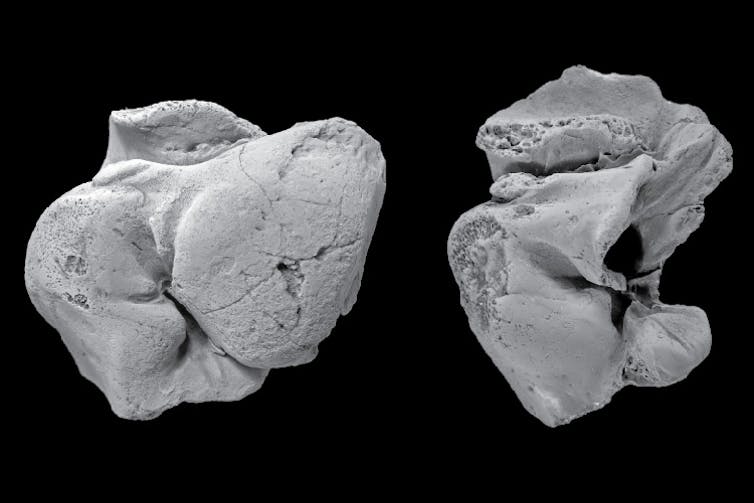

Two fossils from Beaumaris and Hamilton in Victoria have turned out to be the remains of ancient monk seals. This discovery, part of an ongoing effort to investigate Melbourne’s globally important marine fossils, was outlined by our team in a paper published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

How Are Monk Seals Different From Other Seals?

Monk seals are from a completely different group to the fur seals and sea lions that live in Australian waters today. Australia’s warm environment in the past made it an ideal habitat for true seals, the group to which monk seals belong.

These seals would have coexisted with Australia’s ancient megafauna, such as giant kangaroos and the oddball palorchestids.

Read more: In a land of ancient giants, these small oddball seals once called Australia home

This discovery was made when our team revisited two fossils from Museums Victoria’s collections, the identity of which has been a mystery for 40 years.

When we analysed them, they turned out to be the oldest evidence of monk seals found so far, at roughly 5 million years old. The fossils are earbones, the part of the skull that contains the structures needed for hearing. The anatomy of earbones means they are very useful for helping palaeontologists identify what animal fossils belong to.

Together with the recently discovered Eomonachus (a 3 million-year-old New Zealand monk seal), these fossils demonstrate that monk seals had a long history in Australasia. These discoveries have now almost doubled the number of geographic regions monk seals used to occupy in the past, and confirm they used to be a much larger group.

What Happened?

If monk seals were so widespread down under in the past, why are they no longer here? The short answer is climate change.

Around 2.5 million years ago, the onset of the ice ages changed the world’s oceans, making the waters colder and sea levels lower. This led to extinctions in many marine mammal groups, including the monk seals. In short, monk seals disappeared in the southern hemisphere, leaving them only present in the Mediterranean and the tropics.

Despite monk seals being protected from hunting today, these fossil discoveries suggest their troubles may be far from over. Their fossil relatives have now demonstrated they are susceptible to environmental change.

Rising sea levels are already threatening the Hawaiian species, and human-driven changes also endanger the Mediterranean species.

Without continued protection, the remaining monk seals may soon disappear along with their extinct relatives.![]()

James Patrick Rule, Research Fellow, Monash University; Erich Fitzgerald, Senior Curator, Vertebrate Palaeontology, Museums Victoria, and Justin W. Adams, Senior Lecturer, Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Local Opportunities: Youth Advisory Group + Plan And Run A Youth Event

NSW Young Environmental Citizens Of The Year

Council Among Those To Showcase Local Acts On Make Music Day

- Northern Beaches Council - 50 musicians performing 45-minute sets across four locations including the Manly Corso, Berry Markets at Narrabeen Lagoon and Mona Vale Village Park and Dee Why Town Centre.

- City of Parramatta Council and Sydney Olympic Park Authority - events in multiple public spaces including Parramatta Square, Cathy Freeman Park, Jacaranda Square, The Abattoir Heritage Precinct, Epping Railway Station and more, featuring 30 acts from Western Sydney’s live music scene;

- Yours and Owls Event - Wollongong’s Globe Lane will be transformed to present Full Set Fest, to showcase grassroots and promising artists in the Illawarra;

- Lisa Farrawell - in a First Nations-led initiative, local musicians will perform live on an outdoor stage for the Crescent Head community;

- Blacklight Collective - for a one-day pop-up program in Coffs Harbour featuring dozens of local artists performing electronica, contemporary, Indian classical, percussion, jazz and more; and

- Leeton Shire Council – for two acts including a soul, afrobeat and electronic artists to the Leeton Skate Park

Danica's Career Sets Sail Thanks To TAFE NSW

A Double Bay local, originally from Serbia, has credited TAFE NSW with helping her to land a dream job at a at an iconic local sailing club, with plans to open her own hospitality business one day.

A Double Bay local, originally from Serbia, has credited TAFE NSW with helping her to land a dream job at a at an iconic local sailing club, with plans to open her own hospitality business one day. Sound Education Leads To Blockbuster Career

After school, Mr Climpson wasn’t sure what he wanted to do but when his mum suggested he try the Certificate IV in Screen and Media (Television) at TAFE NSW he was keen to give it a go.

After school, Mr Climpson wasn’t sure what he wanted to do but when his mum suggested he try the Certificate IV in Screen and Media (Television) at TAFE NSW he was keen to give it a go.Helena's On Her Way To A Ferry Impressive Career

With Australia relying on sea transport for 99% of exports and Newcastle being the world's largest coal export port, it makes sense that TAFE NSW Newcastle offers a wide range of maritime courses.

With Australia relying on sea transport for 99% of exports and Newcastle being the world's largest coal export port, it makes sense that TAFE NSW Newcastle offers a wide range of maritime courses.Night Drive For Learners

Karuah Mother Tour

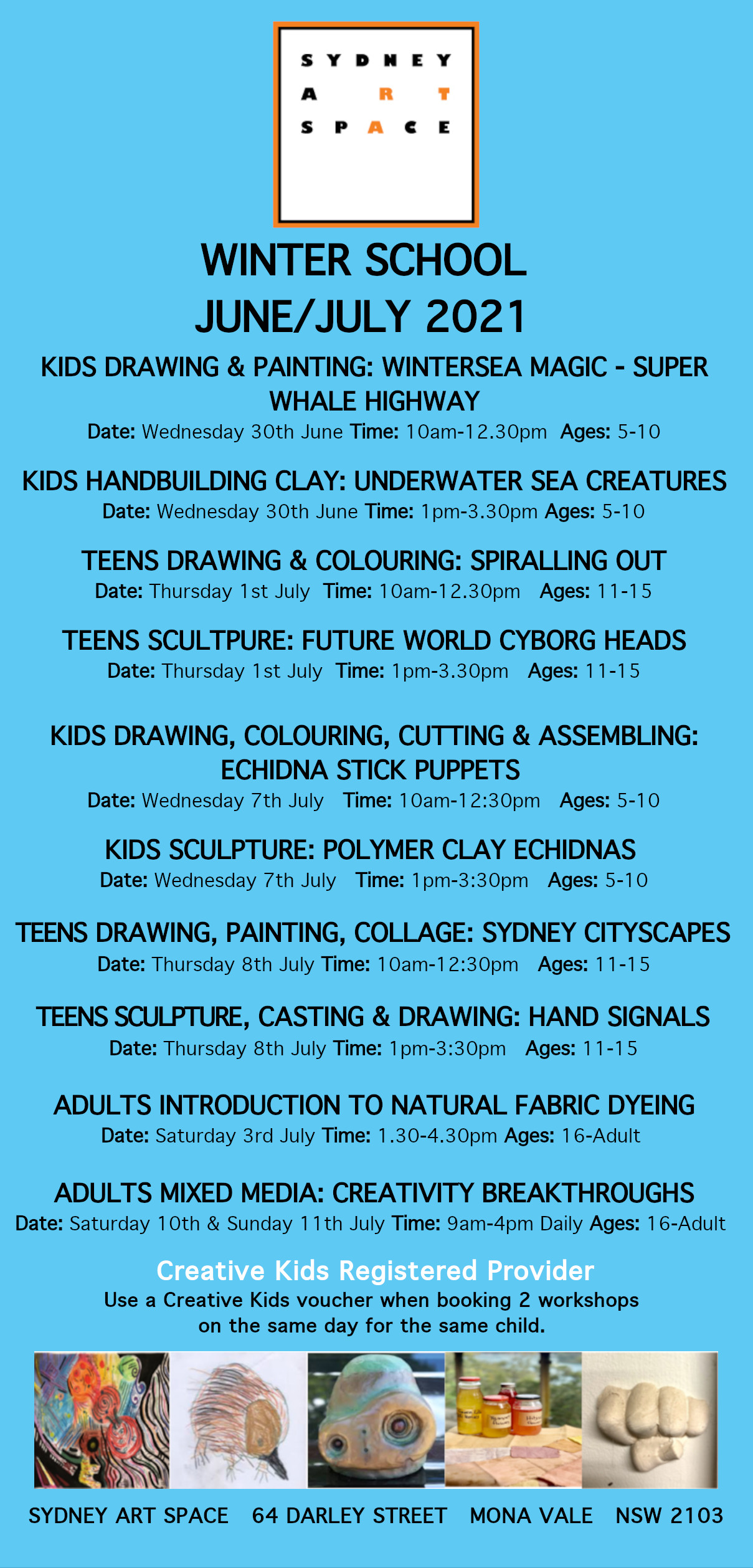

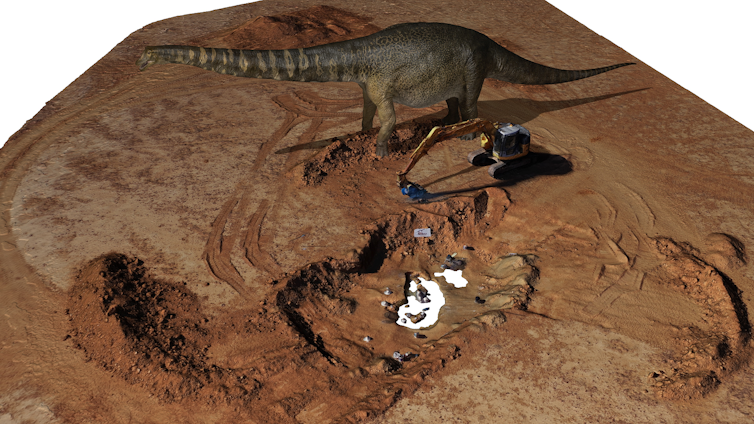

Dorothea Mackellar Poetry Competition 2021 Entries Now Open

2021 OPTIONAL THEME: "RICH AND RARE"

''Our poets are encouraged to take inspiration from wherever they may find it, however if they are looking for some direction, competition participants are invited to use this year's optional theme to inspire their entries."

In 2021, the Dorothea Mackellar Memorial Society has chosen the theme “Rich and Rare.” As always, it is an optional theme, so please write about whatever topic sparks your poetic genius.

For a copy of the wonderful theme poster, please click here.

HOW TO ENTER

*PLEASE NOTE: If you're registering as an individual student, put your HOME address in your personal details and not your SCHOOL'S address! The address you list is where your participation certificate will be posted!*

ONLINE SUBMISSION

(primary school and secondary school, anytime during the competition period)

Teacher/parent - registration completed online (invoice will be emailed within 2 weeks of registration)

Log in to your page.

Enter student details and submit poem(s) (cut and paste or type in poem content direct to the webpage) PLEASE DO NOT UPLOAD POEMS AS ATTACHMENTS AS THAT FUNCTION IS FOR POSTAL ENTRIES ONLY.

Repeat step 3 for every student/individual poem.

PLEASE SEE HERE FOR A DETAILED PDF ON ENTRY INSTRUCTIONS FOR TEACHERS AND PARENTS.

USEFUL TIPS

Have a read of the judges' reports from the previous year. They contain some very helpful advice for teachers and parents alike!

It is recommended for schools to appoint a coordinator for the competition.

Only a teacher/parent can complete the registration form on behalf of the student/child.

Log-in details: username is the email address and a password of your choice.

Log-in details can be given to other teachers/students for poem submission in class/at home.

Log-in as many times as necessary during the competition period.

Teachers can view progress by monitoring the number and content of entries.

Individual entries are accepted if the school is not participating or a child is home schooled. Parent needs to complete the registration form with their contact details. Please indicate 'individual entry' under school name and home postal address under school address.

Invoice for the entry fee will be sent to the registered email address within 2 weeks.

‘Participation certificate only’ option available for schools where pre-selection of entries has been carried out. Poems under this option will not be sent to judges, students will still receive participation certificate for their efforts.

Please read the Conditions of Entry before entering. Entries accepted: March 1 to June 30, results announced during early September.

Visit: https://www.dorothea.com.au/How-to-Enter-awards

Moved by words: how poetry helps us express our feelings

Poetry has made something of a comeback in popular culture, thanks to America’s Amanda Gorman, who read her performance poems at a presidential inauguration and this year’s Super Bowl. Gorman has been described as bringing poetry to the masses.

However, when it comes to the mainstream, poetry has long been hiding in plain sight. Gorman’s spoken-word performances, which have been compared to hip hop, drew attention to poetry in music lyrics. But poetry is also visible in movies and on TV.

These media representations are interesting because they show how poetry is popularly understood in connection with feelings. And that popular wisdom chimes with findings in cognitive neuroscience about how language and, by extension, poetry work.

Read more: Ode to the poem: why memorising poetry still matters for human connection

Aside from films or TV series about poets, such as Dickinson or Paterson, poetry makes a cameo in some of our most iconic films, where it is said to represent or intensify a range of emotions. These include love (Before Sunrise), mad ambition (Citizen Kane), nostalgic patriotism (Skyfall), pride (Invictus), nihilism (Apocalypse Now) and trauma (The Piano).

Poetry, representative of emotion, is also frequently used to symbolise humanity. This is particularly apparent in films about clones.

In the Tom Cruise blockbuster Oblivion, when the clone Jack Harper recites a poem from Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome this reinforces his legitimacy. In Blade Runner, Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty misquotes William Blake:

Fiery the angels fell; deep thunder rolled around their shores; burning with the fires of Orc.

What emerges from poetry’s onscreen appearances, then, is a popular understanding of it as an expression of human feeling and evidence of genuine humanity.

Cognitive Neuroscience

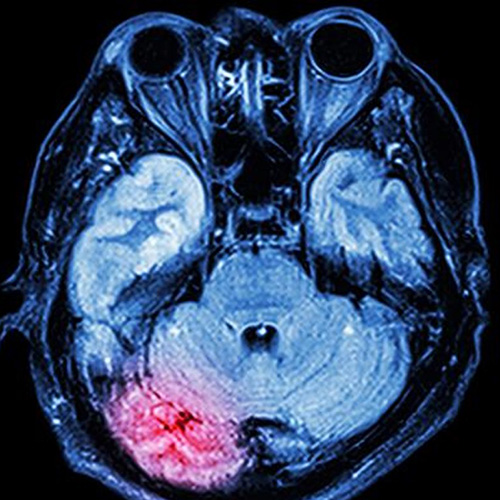

This intuitive understanding of poetry resonates with findings in cognitive neuroscience. Leaving behind theories of the brain that suggest it operates like a computer and theories of language that focus on “mental grammar”, many scientists now acknowledge the body and emotion as the foundations of both cognition and speech.

Of particular interest is the role of mirror neurons. These brain cells fire when an action is observed or performed, and they tell us a lot about how we understand the actions of others. They suggest understanding comes from a mirroring or imitation that takes place in the brain but is acted out or felt in the body.

An example is the contagious effect of a smile. When we observe someone smiling, we mirror that action to understand it.

Something similar happens when understanding language. Words contagiously move us. As neuroscientist Christian Keysers explains in The Empathic Brain, if you hear or read the word “lick”, the part of your brain that moves your mouth is activated to aid understanding. The same happens if you hear or read the word “kick”. As a result, we feel the meaning of these words in our bodies.

What about producing words? Speech is fundamentally a motor activity, which evolved from gesture. We are moved to speak, and we literally move — our lips, our tongue, our lungs, our stomach muscles, and often even our hands — to express ourselves.

As infants, we begin learning language in interaction with a caregiver, imitating the shapes of their mouth, and waving our arms and legs in excitement and frustration at the repetitive noises they make, until eventually we are able to imitate their sounds. Those sounds are accompanied by feelings, related most strongly to a desire to communicate beyond the boundaries of ourselves.

Of course, language develops into a more abstract system for communication. It can often remain a struggle, however, to give expression to feelings that are powerfully felt in the body, such as loneliness or grief or trauma. As John Hannah’s character says in Four Weddings and a Funeral, when trying to articulate his feelings about his dead partner, “Unfortunately there I run out of words”.

Read more: On poetry and pain

Rhymes And Rhythms

This is where poetry comes in, making use of the rhymes and rhythms that have helped us find speech from infancy, calling attention to the auditory qualities of language to convey meaning through feeling.

If we can’t do it ourselves, we quote someone else’s words, instinctively and ritualistically associating poetry with the expression of emotion.

This link to emotion, as well as child-like speech, undoubtedly goes some way to explaining another popular idea about poetry: that it signals “madness”. Biopics of poets feed this stereotype by overwhelmingly choosing poets with mental illnesses as their subjects — for instance, Sylvia and Pandaemonium, portraits of Sylvia Plath and Samuel Taylor Coleridge respectively.

However, cognitive neuroscience — and popular wisdom — suggest poetry actually exemplifies an important truth about language and human nature.

While poetry is regularly denounced for “not making sense”, our cognition and our language do not arise according to purely rational principles.

We are bodies wrought by feeling. Robin Williams’ character simplifies this truth in Dead Poets Society:

We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion.

Maria Takolander, Associate Professor in Creative Writing and Literary Studies, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

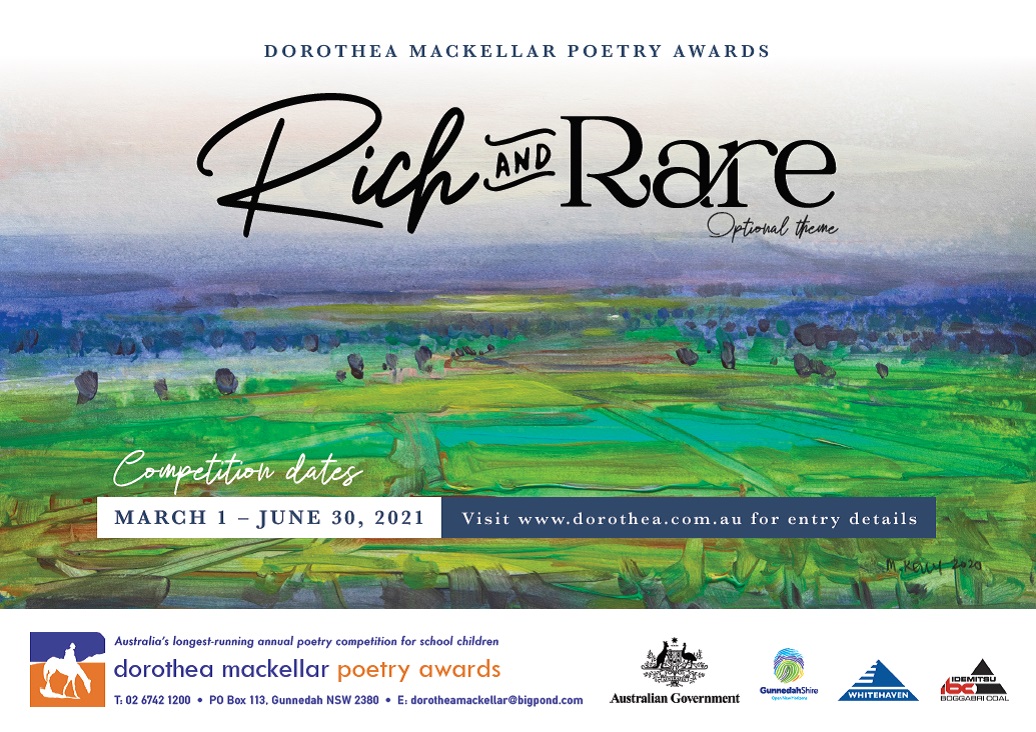

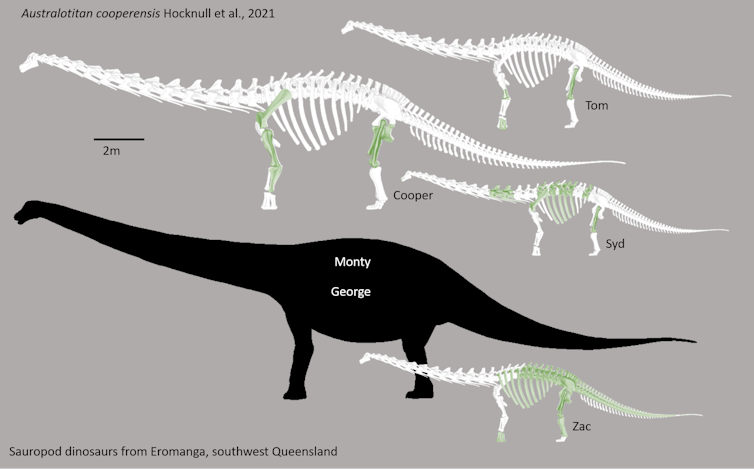

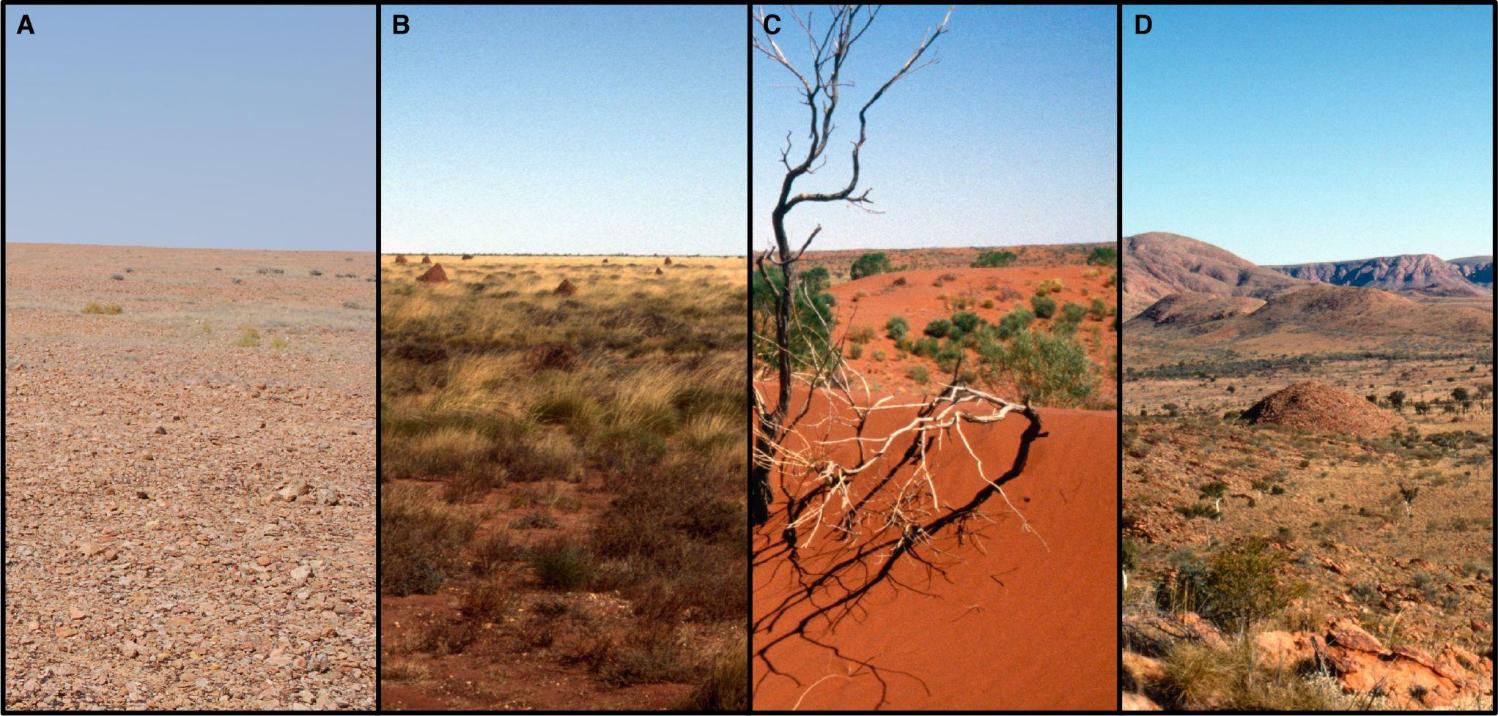

Introducing Australotitan: Australia's largest dinosaur yet spanned the length of 2 buses

Today, a new Aussie dinosaur is being welcomed into the fold. Our study published in the journal PeerJ documents Australotitan cooperensis – Australia’s largest dinosaur species ever discovered, and the largest land-dwelling species to have walked the outback.

Australotitan, or the “southern titan”, was a massive long-necked titanosaurian sauropod estimated to have reached 25–30 metres in length and 5–6.5m in height. It weighed the equivalent of 1,400 red kangaroos.

It lived in southwest Queensland between 92–96 million years ago, when Australia was attached to Antarctica, and the last vestiges of a once-great inland sea had disappeared.

The discovery of Australotitan is a major new addition to the “terrible lizards” of Oz.

Like Finding Needles In Haystack

Finding dinosaurs in Australia has been labelled an incredibly difficult task.

In outback Queensland, dinosaur sites are featureless plains. Compare that to many sites overseas, where mountain ranges, deep canyons or exposed badlands of heavily-eroded terrain can help reveal the ancient layers of preserved fossilised bones.

Today, the area where Australotitan lived is oil, gas and grazing country. Our study represents the first major step in documenting the dinosaurs from this fossil field.

The first bones of Australotitan were excavated in 2006 and 2007 by Queensland Museum and Eromanga Natural History Museum palaeontologists and volunteers. We nicknamed this individual “Cooper” after the nearby freshwater lifeline, Cooper Creek.

After the excavation, we embarked on the long and painstaking removal of the rock that entombed Cooper’s bones. This was necessary for us to properly identify and compare each bone.

Thousands Of Kilograms Bones In A Backpack

We needed to compare Cooper’s bones to all other species of sauropod dinosaur known from both Australia and overseas, to confirm our suspicions of a new species.

But travelling from collection to collection at various museums to compare hundreds of kilograms of fragile dinosaur bones was simply not possible. So instead, we used 3D digital scanning technology which allowed us to virtually carry thousands of kilograms of dinosaur bones in one seven kilogram laptop.

These kinds of research projects have created a new opportunity for museums and researchers to share their amazing collections globally, with researchers and the public.

And thanks to two decades of effort by palaeontologists, citizen scientists, regional not-for-profit museums and local landowners, there has been a recent boom in Australian dinosaur discoveries.

We Are Family

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we found all four of the sauropod dinosaurs that lived in Australia between 96-92 million years ago (including Australotitan) were more closely related to one another than they were to other dinosaurs found elsewhere.

However, we couldn’t conclusively place any of these four related species together in the same place at the same time. This means they could have evolved through time to occupy very different habitats. It’s even possible they never met.

The Aussie species share relations with titanosaurians from both South America and Asia, suggesting they dispersed from South America (via Antarctica) during periods of global warmth.

Or, they may have island-hopped across ancient island archipelagos, which would eventually make up the present-day terrains of Southeast Asia and the Philippines.

Trampling Through The Cretaceous

Digitally capturing gigantic sauropod bones and fossil sites in 3D has led to some remarkable discoveries. Several of Cooper’s bones were found to be crushed by the footsteps of other sauropod dinosaurs.

What’s more, during Cooper’s excavation we uncovered another smaller sauropod skeleton — possibly a smaller Australotitan — trampled into a nearly 100m-long rock feature. We interpreted this to be a trample zone: an area of mud compressed under foot by massive sauropods as they moved along a pathway, or at the edge of a waterhole.

Similar trampling features can be seen today around Australian billabongs, or waterholes in Africa where the largest plant-eaters, such as elephants and hippopotamuses, trample mud into a hard layer.

In the case of the hippopotamus, they cut channels through the mud to navigate between precious water and food sources. Life in Australia during the Cretaceous period can be pictured similarly, except super-sized.

In the present, out there in Australia’s dinosaur country, you might find yourself staring across a barren plain imagining what other secrets this world of long-lost giants will reveal.

Read more: Curious Kids: could dinosaurs evolve back into existence? ![]()

Scott Hocknull, Senior Curator of Geosciences, Queensland Museum, and Honorary Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How an app to decrypt criminal messages was born 'over a few beers' with the FBI

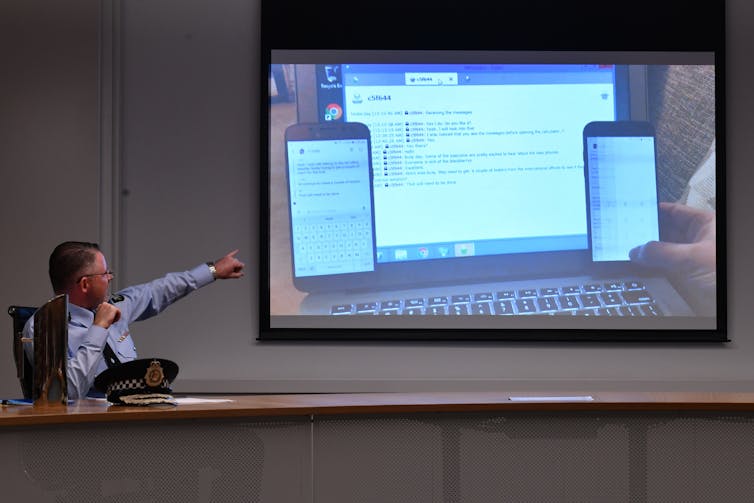

David Tuffley, Griffith UniversityAustralian and US law enforcement officials on Tuesday announced they’d sprung a trap three years in the making, catching major international crime figures using an encrypted app.

More than 200 underworld figures in Australia have been charged in what Australian Federal Police (AFP) say is their biggest-ever organised crime bust.

The operation, led by the US Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), spanned Australia and 17 other countries. In Australia alone, more than 4,000 police officers were involved.

At the heart of the sting, dubbed Operation Ironside, was a type of “trojan horse” malware called AN0M, which was secretly incorporated into a messaging app. After criminals used the encrypted app, police decrypted their messages, which included plots to kill, mass drug trafficking and gun distribution.

Millions Of Messages Unscrambled

AFP Commissioner Reece Kershaw said the idea for AN0M emerged from informal discussions “over a few beers” between the AFP and FBI in 2018.

Platform developers had worked on the AN0M app, along with modified mobile devices, before law enforcement acquired it legally and adapted it for their use. The AFP say the developers weren’t aware of the intended use.

Once appropriated by law enforcement, AN0M was reportedly programmed with a secret “back door”, enabling them to access and decrypt messages in real time.

A “back door” is a software agent that circumvents normal access authentication. It allows remote access to private information in an application, without the “owner” of the information being aware.

So the users — in this case the crime figures — believed communication conducted via the app and smartphones was secure. Meanwhile, law enforcement could reportedly unscramble up to 25 million encrypted messages simultaneously.

But without this back door, strongly encrypted messages would be almost impossible to decrypt. That’s because decryption generally requires a computer to run through trillions of possibilities before hitting on the right code to unscramble a message. Only the most powerful computers can do this within a reasonable time frame.

Read more: Cryptology from the crypt: how I cracked a 70-year-old coded message from beyond the grave

Providers Resist Pressure For ‘Back-Door’ Access

In the mainstream world of encrypted communication, the installation of “back-door” access by law enforcement has been strenuously resisted by app providers, including Facebook who owns WhatsApp.

In January 2020, Apple refused law enforcement’s request to unlock the Pensacola shooting suspect’s iPhone, following a deadly 2019 Florida attack which killed three people.

Apple, like Facebook, has long refused to allow back-door access, claiming it would undermine customer confidence. Such incidents highlight the struggle of balancing competing demands for user privacy with the imperative of preventing crime for the greater good.

Read more: Facebook is merging Messenger and Instagram chat features. It's for Zuckerberg's benefit, not yours

Getting Criminals To Use AN0M

Once AN0M was developed and ready for use, law enforcement had to get it into the hands of criminal “underworld” figures.

To do so, undercover agents reportedly persuaded fugitive Australian drug trafficker Hakan Ayik to unwittingly champion the app to his associates. These associates were then be sold mobile devices pre-loaded with AN0M on the black market.

Purchase was only possible if referred through an existing user of the app, or by a distributor who could vouch for the potential customer as not working for law enforcement.

The AN0M-loaded mobiles — likely Android-powered smartphones — came with reduced functionality. They could do just three things: send and receive messages, make distorted voice calls and record videos — all of which was presumed to be encrypted by the users.

With time the AN0M phone increasingly became the device of choice for a significant number of criminal networks.

Building Up A Network Picture

Since 2018, law enforcement agencies across 18 countries, including Australia, had been patiently listening to millions of conversations through their back-door control of the AN0M app.

Information was retrieved on all manner of illegal activities. This gradually enabled police to etch a detailed picture of various crime networks. Some of the footage and images retrieved have been cleared for public release.

One major challenge was for police to match overheard conversations with identities — as the AN0M phone could be purchased anonymously and paid for with Bitcoin (which allows secure transactions that can’t be traced). This may help explain why it took three years before police openly identified alleged perpetrators.

It’s likely the evidence obtained will be used in prosecutions now that a multitude of arrests have been made.

The Future Of Encryption

Encryption technology is improving fast. It needs to — because computing power is also growing rapidly.

This means hackers are becoming increasingly capable of breaking encryption. Moreover, when quantum computers become available this problem will be further exacerbated, since they are massively more powerful than conventional computers today.

These developments will likely weaken the security of encrypted messaging apps used by law abiding people, including popular apps such as WhatsApp, LINE and Signal.

Strong encryption is an essential weapon in the cybersecurity arsenal and there are thousands of legitimate situations where it’s needed. It’s ironic then, that the technology intended by some to keep the public safe can also be leveraged by those with criminal intent.

Networks of organised crime have used these “legitmate” tools to conduct their business, secure in the knowledge that law enforcement can’t access their communications. Until AN0M, that is.

And while Operation Ironside may have sent a shiver through criminal subcultures operating around the world, these syndicates will likely develop their own countermeasures in this ongoing game of cat and mouse.

Read more: Seven ways the government can make Australians safer – without compromising online privacy ![]()

David Tuffley, Senior Lecturer in Applied Ethics & CyberSecurity, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Proceed to your nearest (virtual) exit: gaming technology is teaching us how people respond to emergencies

Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) aren’t just for gaming anymore, they’re also proving to be useful tools for disaster safety research. In fact, they could save lives.

Around the world, natural and human-made disasters such as earthquakes, bushfires and terrorist attacks threaten substantial economic loss and human life.

My research review looked at 64 papers on the topic of using AR and VR-based experiments (mostly simulating emergency scenarios) to investigate human behaviour during disaster, provide disaster-related education and enhance the safety of built environments.

If we can investigate how certain factors influence people’s decisions about the best course of action during disaster, we can use this insight to further construct an array of VR and AR experiments.

Finding The Optimal Fire Desing

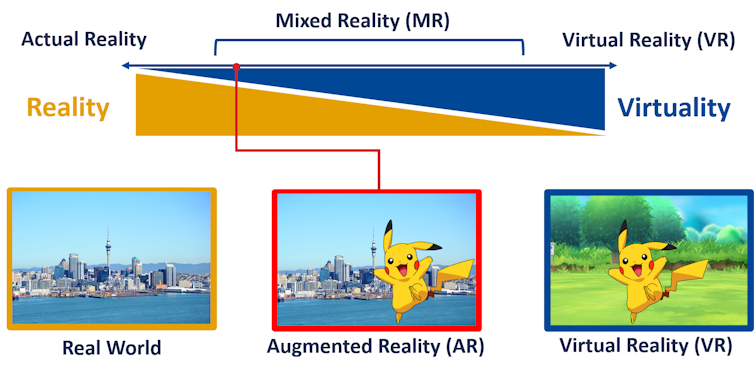

Research has shown the potential of AR and VR in myriad disaster contexts. Both of these technologies involve digital visualisation. VR involves the visualisation of a complete digital scene, whereas AR allows digital objects to be superimposed over a real-life background.

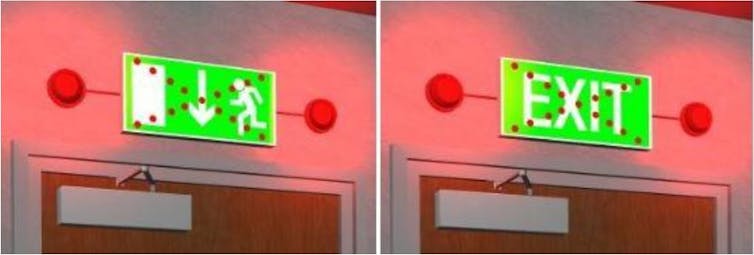

VR has already played a key role in designing safety evacuation systems for new buildings and infrastructure. For example, in past research my colleagues and I have used VR to identify which signage is the best to use in tunnels and buildings during emergency evacuations.

In these studies we asked participants to rank different signs using a questionnaire based on the “theory of affordances”, which looks at what the physical environment or a specific object offers an individual. In other words, we explored how different signs can be sensed, understood and used by different people during emergencies.

Before building expensive new infrastructure, we can simulate it in VR form and test how different evacuation signage performs for participants. In the case of signage for tunnel exits, research showed:

— green or white flashing lights performed better than blue lights

— a flashing rate of one flash per second or four flashes per second is recommended over a slower rate of, say, one flash per four seconds.

— LED light sources performed better than single and double-strobe lights.

In another non-immersive VR study, we observed participants’ behaviours and identified which sign was the best to direct people away from a specific exit in case of an emergency (as that exit might lead towards a fire, for instance).

The results showed red flashing lights helped evacuees identify the sign, and the sign itself was most effective with a green background marked with a red “X”.

VR and AR are uniquely positioned to let experts study how humans behave during disasters — and to do so without physically harming anyone.

Read more: What is augmented reality, anyway?

From Pokemon Go To Earthquake Drills

Research projects have tested how AR superimpositions can be used to guide people to safety during a tsunami warning or earthquake.

In theory, the same approach could be used in other contexts, such as during a terror attack. AR applications could be built to teach people how to act in case of terror attacks by following the rule of escape, hide and tell, as advised by the government.

Such virtual applications have great potential to educate thousands of people quickly and inexpensively. Our latest VR study indicated this may make them preferable to traditional training.

Read more: Antarctica without windchill, the Louvre without queues: how to travel the world from home