Inbox and Environment News: Issue 499

June 20 - 26, 2021: Issue 499

Consultations On Wakehurst Parkway + Ingleside Development Closing Soon

Proposals For Reducing Flooding On Wakehurst Parkway Now Open For Feedback - Closes Sunday June 27th

Revised South-Ingleside Precinct Housing Development Plan Now Open For Feedback - feedback closes July 6

Mona Vale Dunes Bushcare Group Planting-Out Installs 600 Natives

Bangalley Head Landcare Group Progress

Brookvale To Get Cooler And Greener With Installation Of 250 Trees

Federal Consultation On Endangered Listing For The Koala Now Open - Closes July 30, 2021

Koala Listing Strengthens Call For An Independent Environmental Compliance Agency

Draft National Recovery Plan For The Koala (Combined Populations Of Queensland, New South Wales And The Australian Capital Territory)

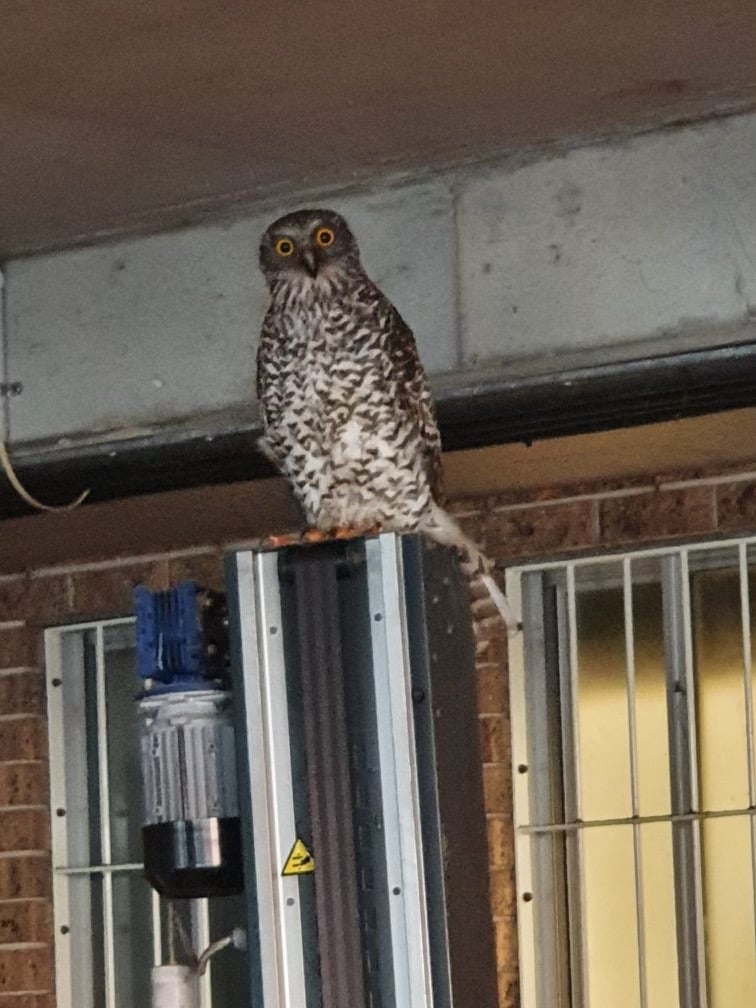

The Powerful Owl Project Update

ORRCA News: 2021 Census Day - Sunday June 27

- This is a FREE event for all to join in.

- From sun up to sun down.

- Record all your sightings from your favourite whale watching location using an ORRCA data sheet and sending it into the team at the end of the day.

- Email orrcacensusday@gmail.com for all the details as they unfold.

Heat Spells Doom For Australian Marsupials

Public Concern On Human Health Impact Of Plastic Pollution

NSW Government To Tackle Plastics And Waste

Prioritising The State's Coastline For Future Generations

- Delivering outcomes;

- Reviewing legislation and updating guidance;

- Supporting coordination, collaboration and engagement;

- Providing science and information; and

- Funding and financing.

Piece Of Foreshore History Secured

Fencing Riverbanks Program Cuts Off Access For Wildlife To Water

NSW State Government's Plans To Open Western NSW To Coal Mining Open For Feedback

- Forty-five recorded Aboriginal heritage sites and an additional 13 sites that are restricted and location data not supplied in the proposed coal release areas.

- Twenty-two threatened fauna species and six threatened flora species including the koala, the critically endangered regent honeyeater and the endangered spotted-tailed quoll, as well as four plant species endemic to the Rylstone/western Wollemi area.

- One thousand, eight hundred and fifty-four hectares of groundwater dependant ecosystems.

- Six thousand, six hundred and thirty-four hectares of potential threatened ecological communities.

- Thirty-six water bores.

- One hundred and twenty kilometres of stream channels in good condition and 118 kilometres of stream channels classed as a high level of fragility.

Keith Pitt’s Gas And Oil Basin “Release” Plans For Destruction Of Channel Country

Bin Trim App Helps Waste Industry And Councils Guide Business Recycling

Boris Johnson overstates Morrison’s climate ambition, as Australia-UK trade agreement reached

Michelle Grattan, University of CanberraBritish Prime Minister Boris Johnson put Scott Morrison on the spot when he told their joint news conference he thought the Australian PM had “declared for net zero by 2050”.

When Johnson made the statement a journalist interjected to point out Morrison’s policy was to get to net zero “preferably” by 2050.

Johnson pressed on to say this was “a great step forward when you consider[…] the situation Australia is in. It’s a massive coal producer. It’s having to change the way things are orientated, and everybody understands that.

"You can do it fast. In 2012 this country had 40% of its power from coal. It’s now less than 2%, going down the whole time. […] I’m impressed by the ambition of Australia. Obviously we’re going to be looking for more the whole time, as we go into COP26 in November.”

The net zero moment came as the two stood together to announce they had reached an in-principle agreement on a free trade deal between Britain and Australia – the first such deal the United Kingdom has done post Brexit.

Johnson had been asked whether he wanted Australia to go beyond its present 2030 emissions reduction target.

Morrison has been under strong pressure from both Johnson and United States President Joe Biden to embrace the 2050 target. But he has so far not done so, despite edging towards it. His position is to get to net zero “as soon as possible, preferably by 2050.”

Formally embracing the target would threaten a fight within the Nationals that could destabilise the party’s leader Michael McCormack.

Nationals Senate leader Bridget McKenzie warned this week:

“There is no agreement with the second party of this Coalition government on any target date for zero emissions. In fact it would fly in the face of the Nationals public policy commitment.”

The free trade agreement, which still has details to be finalised, would reduce barriers on the mobility of workers between the two countries as well on trade in goods and services.

The deal would promote more exchange of young people, allowing them to stay and work in each country for three years instead of two. This arrangement would apply to people up to age 35 rather than 30, as at present.

The federal government says Australian producers and farmers would “receive a significant boost by getting greater access to the UK market” while Australian consumers would “benefit from cheaper products, with all tariffs eliminated within five years, and tariffs on cars, whisky, and the UK’s other main exports eliminated immediately” the agreement started.

Australia would within five years place less onerous conditions on British backpackers, who presently have to spend a set time working in agriculture, or other sectors of labour shortage in regional Australia, to get an extension of their visa.

A separate agriculture visa would be established for UK and Australian visa holders, to get more two way traffic (for example, of shearers) in the agricultural sector.

Over 10 to 15 years the UK would liberalise Australian imports of beef and sheep meat, with shorter periods for sugar and dairy products.

The agricultural sectors in both Britain and Australia expressed concerns when the agreement was being negotiated. In Australia farmers have been worried about the possibility of losing labour if the conditions on backpackers were scrapped.

Johnson said the deal would be good for British car manufacturers and the export of British financial and other services, and he hoped for the agricultural sectors on both sides.

On agriculture “we’ve had to negotiate very hard. […] This is a sensitive sector for both sides, and we’ve got a deal that runs over 15 years and contains the strongest possible provisions for animal welfare.”

The removal of the farm work requirement would make it easier for British people and young people to go and work in Australia, he said.

Morrison said the deal would open the pathway to Britain’s entry into the The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

He also indicated it was “enormously helpful” in the context of the difficulties with China. “Where you have challenges with one trading partner from time to time, then the ability to be able to diversify your trade into more and more countries is incredibly important.”

Morrison and Johnson discussed the final points of the agreement in principle over a dinner meeting at 10 Downing Street. Their talks also included climate change.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia needs construction waste recycling plants — but locals first need to be won over

Strong community opposition to a proposed waste facility in regional New South Wales made headlines earlier this year. The A$3.9 million facility would occupy 2.7 hectares of Gunnedah’s industrial estate. It’s intended to process up to 250,000 tonnes a year of waste materials from Sydney.

Much of this is construction waste that can be used in road building after processing. Construction of the plant will employ 62 people and its operation will create 30 jobs. Yet every one of the 86 public submissions to the planning review objected to the project.

Residents raised various concerns, which received widespread local media coverage. They were concerned about water management, air quality, noise, the impact of hazardous waste, traffic and transport, fire safety and soil and water. For instance, a submission by a local businessman and veterinary surgeon stated:

“The proposed facility is too close to town, residences and other businesses […] Gunnedah is growing and this proposed development will be uncomfortably close to town in years to come.”

The general manager of the applicant said descriptions such as “toxic waste dump” were far from accurate.

“It’s not a dump […] Its prime focus is to reclaim, reuse and recycle.”

He added: “[At present] the majority of this stuff goes to landfill. What we’re proposing is very beneficial to the environment, which is taking these resources and putting them back into recirculation. The reality is the population is growing, more waste is going to get generated and the upside is we’re much better processing and claiming out of it than sending it to landfill.”

Read more: We create 20m tons of construction industry waste each year. Here's how to stop it going to landfill

Why Are These Facilities Needed?

According to the latest data in the National Waste Report 2020, Australia generated 27 million tonnes of waste (44% of all waste) from the construction and demolition (C&D) sector in 2018-19. That’s a 61% increase since 2006-07. This waste stream is the largest source of managed waste in Australia and 76% of it is recycled.

However, recycling rates and processing capacities still need to increase massively. The environmental impact statement for the Gunnedah project notes Sydney “is already facing pressure” to dispose of its growing construction waste. Most state and national policies – including the NSW Waste Avoidance and Resource Recovery Strategy 2014-2021, NSW Waste and Resource Recovery Infrastructure Strategy and 2018 National Waste Policy – highlight the need to develop infrastructure to effectively manage this waste.

Read more: The 20th century saw a 23-fold increase in natural resources used for building

Why, Then, Do People Oppose These Facilities?

Public opposition to new infrastructure in local neighbourhoods, the Not-in-My-Back-Yard (NIMBY) attitude, is a global phenomenon. Australia is no exception. We have seen previous public protests against waste facilities being established in local areas.

The academic literature reports the root causes of this resistance are stench and other air pollution, and concerns about impacts on property values and health. Factors that influence individuals’ perceptions include education level, past experience of stench and proximity to housing.

What Are The Other Challenges Of Recycling?

Our research team at RMIT University explore ways to effectively manage construction and demolition waste, with a focus on developing a circular economy. Our research shows this goal depends heavily on the development of end markets for recycled products. Operators then have the confidence to invest in recycling construction and demolition waste, knowing it will produce a reasonable return.

Read more: The planned national waste policy won't deliver a truly circular economy

A consistent supply of recycled material is needed too. We believe more recycling infrastructure needs to be developed all around Australia. Regional areas are the most suitable for this purpose because they have the space and a need for local job creation.

To achieve nationwide waste recycling, however, everyone must play their part. By everyone, we mean suppliers, waste producers, waste operators, governments and the community.

Today we are facing new challenges such as massive urbanisation, shortage of virgin materials, increasing greenhouse gas emissions and bans on the export of waste. These challenges warrant new solutions, which include sharing responsibility for the waste we all generate.

Read more: A crisis too big to waste: China's recycling ban calls for a long-term rethink in Australia

What Can Be Done To Resolve Public Concerns?

Government has a key role to play in educating the public about the many benefits of recycling construction and demolition waste. These benefits include environmental protection, more efficient resource use, reduced construction costs, and job creation.

Government must also ensure communities are adequately consulted. A local news report reflected Gunnedah residents’ concern that the recycling facility’s proponent had not contacted them. They initiated the contact. One local said:

“I do understand the short-term financial gains a development like this will bring to the community, but also know the financial and environmental burden they will cause.”

Feedback from residents triggered a series of consultation sessions involving all parties.

A robust framework for consulting the community, engaging stakeholders and providing information should be developed to accompany any such development. Community education programs should be based on research.

For instance, research indicates that, unlike municipal waste recycling facilities, construction and demolition waste management facilities have negligible to manageable impact on the environment and residents’ health and well-being. This is due to the non-combustible nature of most construction materials, such as masonrt.

Such evidence needs to be communicated effectively to change negative community attitudes towards construction and demolition waste recycling facilities. At RMIT, through our National Construction & Demolition Waste Research and Industry Portal, we continue to play our part in increasing public awareness of the benefits.

Read more: With the right tools, we can mine cities ![]()

Salman Shooshtarian, Research Fellow, RMIT University and Tayyab Maqsood, Associate Dean and Head of of Project Management, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

An act of God, or just bad management? Why trees fall and how to prevent it

The savage storms that swept Victoria last week sent trees crashing down, destroying homes and blocking roads. Under climate change, stronger winds and extreme storms will be more frequent. This will cause more trees to fall and, sadly, people may die.

These incidents are sometimes described as an act of God or Mother Nature’s fury. Such descriptions obscure the role of good management in minimising the chance a tree will fall. The fact is, much can be done to prevent these events.

Trees must be better managed for several reasons. The first, of course, is to prevent damage to life and property. The second is to avoid unnecessary tree removals. Following storms, councils typically see a spike in requests for tree removals – sometimes for perfectly healthy trees.

A better understanding of the science behind falling trees – followed by informed action – will help keep us safe and ensure trees continue to provide their many benefits.

Why Trees Fall Over

First, it’s important to note that fallen trees are the exception at any time, including storms. Most trees won’t topple over or shed major limbs. I estimate fewer than three trees in 100,000 fall during a storm.

Often, fallen trees near homes, suburbs and towns were mistreated or poorly managed in preceding years. In the rare event a tree does fall over, it’s usually due to one or more of these factors:

1. Soggy soil

In strong winds, tree roots are more likely to break free from wet soil than drier soil. In arboriculture, such events are called windthrow.

A root system may become waterlogged when landscaping alters drainage around trees, or when house foundations disrupt underground water movement. This can be overcome by improving soil drainage with pipes or surface contouring that redirects water away from trees.

You can also encourage a tree’s root growth by mulching around the tree under the “dripline” – the outer edge of the canopy from which water drips to the ground. Applying a mixed-particle-size organic mulch to a depth of 75-100 millimetres will help keep the soil friable, aerated and moist. But bear in mind, mulch can be a fire risk in some conditions.

Root systems can also become waterlogged after heavy rain. So when both heavy rain and strong winds are predicted, be alert to the possibility of falling trees.

Read more: Why there's a lot more to love about jacarandas than just their purple flowers

2. Direct root damage

Human-caused damage to root systems is a common cause of tree failure. Such damage can include roots being:

- cut when utility services are installed

- restricted by a new road, footpath or driveway

- compacted over time, such as when they extend under driveways.

Trees can take a long time to respond to disturbances. When a tree falls in a storm, it may be the result of damage inflicted 10-15 years ago.

3. Wind direction

Trees anchor themselves against prevailing winds by growing roots in a particular pattern. Most of the supporting root structure of large trees grows on the windward side of the trunk.

If winds come from an uncommon direction, and with a greater-than-usual speed, trees may be vulnerable to falling. Even if the winds come from the usual direction, if the roots on the windward side are damaged, the tree may topple over.

The risk of this happening is likely to worsen under climate change, when winds are more likely to come from new directions.

4. Dead limbs

Dead or dying tree limbs with little foliage are most at risk of falling during storms. The risk can be reduced by removing dead wood in the canopy.

Trees can also fall during strong winds when they have so-called “co-dominant” stems. These V-shaped stems are about the same diameter and emerge from the same place on the trunk.

If you think you might have such trees on your property, it’s well worth having them inspected. Arborists are trained to recognise these trees and assess their danger.

Read more: The years condemn: Australia is forgetting the sacred trees planted to remember our war dead

Trees Are Worth The Trouble

Even with the best tree management regime, there is no guarantee every tree will stay upright during a storm. Even a healthy, well managed tree can fall over in extremely high winds.

While falling trees are rare, there are steps we can take to minimise the damage they cause. For example, in densely populated areas, we should consider moving power and communications infrastructure underground.

By now, you may be thinking large trees are just too unsafe to grow in urban areas, and should be removed. But we need trees to help us cope with storms and other extreme weather.

Removing all trees around a building can cause wind speeds to double, which puts roofs, buildings and lives at greater risk. Removing trees from steep slopes can cause the land to become unstable and more prone to landslides. And of course, trees keep us cooler during summer heatwaves.

Victoria’s spate of fallen trees is a concern, but removing them is not the answer. Instead, we must learn how to better manage and live with them.

Read more: Here are 5 practical ways trees can help us survive climate change ![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Peatlands worldwide are drying out, threatening to release 860 million tonnes of carbon dioxide every year

Peatlands, such as fens, bogs, marshes and swamps, cover just 3% of the Earth’s total land surface, yet store over one-third of the planet’s soil carbon. That’s more than the carbon stored in all other vegetation combined, including the world’s forests.

But peatlands worldwide are running short of water, and the amount of greenhouse gases this could set loose would be devastating for our efforts to curb climate change.

Specifically, our new research in Nature Climate Change found drying peatlands could release an additional 860 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year, by around 2100. To put this into perspective, Australia emitted 539 million tonnes in 2019.

To stop this from happening, we need to urgently preserve and restore healthy, water-logged conditions in peatlands. These thirsty peatlands need water.

Peatlands Are Like Natural Archives

Peatlands are found across the world: the arctic tundra, coastal marshes, tropical swamp forests, mountainous fens and blanket bogs on subantarctic islands.

They’re characterised by having water-logged soil filled with very slowly decaying plant material (the “peat”) that accumulated over tens of thousands of years, preserved by the low-oxygen environment. This partially decomposed plant debris is locked up in the soils as organic carbon.

Read more: Peat bogs: restoring them could slow climate change – and revive a forgotten world

Peatlands can act like natural archives, letting scientists and archaeologists reconstruct past climate, vegetation, and even human lives. In fact, an estimated 20,500 archaeological sites are preserved under or within peat in the UK.

As unique habitats, peatlands are home for many native and endangered species of plants and animals that occur nowhere else, such as the white-bellied cinclodes (Cinclodes palliatus) in Peru and Australia’s giant dragonfly (Petalura gigantea), the world’s largest. They can also act as migration corridors for birds and other animals, and can purify water, regulate floods, retain sediments and so on.

But over the past several decades, humans have been draining global peatlands for a range of uses. This includes planting trees and crops, harvesting peat to burn for heat, and for other land developments.

For example, some peatlands rely on groundwater, such as portions of the Greater Everglades, the largest freshwater marsh in the United States. Over-pumping groundwater for drinking or irrigation has cut off the peatlands’ source of water.

Together with the regional drier climate due to global warming, our peatlands are drying out worldwide.

What Happens When Peatlands Dry Out?

When peat isn’t covered by water, it could be exposed to enough oxygen to fuel aerobic microbes living within. The oxygen allows the microbes to grow extremely fast, enjoy the feast of carbon-rich food, and release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Some peatlands are also a natural source of methane, a potent greenhouse gas with the warming potential up to 100 times stronger than carbon dioxide.

But generating methane actually requires the opposite conditions to generating carbon dioxide. Methane is more frequently released in water-saturated conditions, while carbon dioxide emissions are mostly in unsaturated conditions.

Read more: Emissions of methane – a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide – are rising dangerously

This means if our peatlands are getting drier, we would have an increase in emissions of carbon dioxide, but a reduction in methane emissions.

So What’s The Net Impact On Our Climate?

We were part of an international team of scientists across Australia, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, the US and China. Together, we collected and analysed a large dataset from carefully designed and controlled experiments across 130 peatlands all over the world.

In these experiments, we reduced water under different climate, soil and environmental conditions and, using machine learning algorithms, disentangled the different responses of greenhouse gases.

Our results were striking. Across the peatlands we studied, we found reduced water greatly enhanced the loss of peat as carbon dioxide, with only a mild reduction of methane emissions.

The net effect — carbon dioxide vs methane — would make our climate warmer. This will seriously hamper global efforts to keep temperature rise under 1.5℃.

This suggests if sustainable developments to restore these ecosystems aren’t implemented in future, drying peatlands would add the equivalent of 860 million tonnes of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere every year by 2100. This projection is for a “high emissions scenario”, which assumes global greenhouse gas emissions aren’t cut any further.

Protecting Our Peatlands

It’s not too late to stop this from happening. In fact, many countries are already establishing peatland restoration projects.

For example, the Central Kalimantan Peatlands Project in Indonesia aims to rehabilitate these ecosystems by, for instance, damming drainage canals, revegetating areas with native trees, and improving local socio-economic conditions and introducing more sustainable agricultural techniques.

Likewise, the Life Peat Restore project aims to restore 5,300 hectares of peatlands back to their natural function as carbon sinks across Poland, Germany and the Baltic states, over five years.

But protecting peatlands is a global issue. To effectively take care of our peatlands and our climate, we must work together urgently and efficiently.

Read more: People, palm oil, pulp and planet: four perspectives on Indonesia's fire-stricken peatlands ![]()

Yuanyuan Huang, Research Scientist , CSIRO and Yingping Wang, Chief research scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

'Unshackled' Palm-Destroying Beetles Could Soon Invade Australia

A destructive pest beetle is edging closer to Australia as biological controls fail, destroying home gardens, plantations and biodiversity as they surge through nearby Pacific islands. University of Queensland researcher Dr Kayvan Etebari has been studying how palm-loving coconut rhinoceros beetles have been accelerating their invasion.

A destructive pest beetle is edging closer to Australia as biological controls fail, destroying home gardens, plantations and biodiversity as they surge through nearby Pacific islands. University of Queensland researcher Dr Kayvan Etebari has been studying how palm-loving coconut rhinoceros beetles have been accelerating their invasion.New Plan To Revitalise NSW's Oldest Park By Installing Mountain Bike Trails

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park, Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Planning Considerations

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Plan of Management

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Mountain Biking Plan

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Seniors To Benefit From Regional Seniors Travel Card

- the Age Pension through Services Australia or the Department of Veterans’ Affairs

- a Disability Support Pension or a Carer Payment from Services Australia

- a Service Pension issued by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs

- a Disability Pension through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs under the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986

- a War Widow(er)’s Pension issued by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Launch Of State Of The (Older) Nation 2021

There are problems in aged care, but more competition isn’t the solution

The solution to most problems in most markets is more competition.

Whether it’s the market for hairdressers, for massage therapists or for general practitioners, usually, the more of them there are in any town or suburb, the greater is the range and quality they offer and the lower the price.

It’s part of the thinking behind a range of government legislation designed to increase competition and consumer choice in residential aged care.

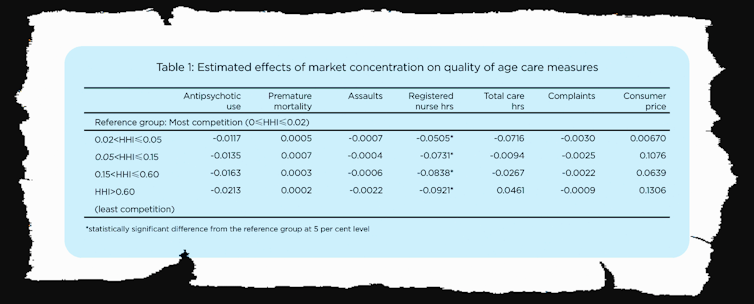

Yet in research just published by the Melbourne Institute using the de-identified records of 2,900 nursing homes provided to the aged care royal commission we found no such effect.

No matter how competition was measured, we found no statistically-significant differences in price or quality as indicated by a range of measures including nursing hours worked per resident, assaults per resident, complaints per resident, the use of antipsychotic drugs and avoidable early deaths.

We measured the amount of competition for each nursing home in three ways: by the number of competitors within a 10-kilometre radius, the distance in kilometres to the nearest competitor and a measure of market concentration known as the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index.

Read more: Aged care, death and taxes after the royal commission

We found great variation in competition (much more in cities, much less in regions) along with slight decreases in competition in urban and remote areas (notwithstanding government measures designed to promote it) and minor increases in competition in regional Australia.

But we found no evidence linking competition to measures of quality of care, with the possible exception of registered nurse hours, although this linkage wasn’t present in all measures of competition.

Competition was weakly associated with price if at all.

On the other hand, we found strong links between ownership and quality of care.

For most measures of quality, government-owned facilities provided much higher quality of care than for-profit providers and not-for-profit providers.

On prices, government-owned facilities charged by far the lowest price per resident per day — 23% lower than for-profits and 8% lower than not-for-profits.

In trying to think of the reasons why competition should not result in competition on prices or on the quality of service, a number of possibilities present themselves.

Residents Know Little About What They Are Getting

One reason is that demand for aged care places often arises suddenly due to significant changes in health conditions such as falls, dementia and loss of balance meaning they have little choice but to use the first facility that becomes available.

Another is that consumers have little information about quality with which to make decisions. Unlike the United States and the United Kingdom, Australian authorities do not yet provide a five-star system of ratings that can be easily understood.

Read more: 4 key takeaways from the aged care royal commission's final report

And prices are extremely hard to understand.

Demand often arises from consumers who experience sudden changes in their cognitive and physical conditions that make it difficult to search for information, and weigh options and exercise choice.

With users hamstrung, there are few market forces to discipline providers.

We Could Empower Users…

Measures that would help include publishing quality ratings (recommended by the royal commission), simplifying prices (not recommended, although the commission recommends an independent pricing authority) and providing consumer advocates to help people navigate through the system (recommended).

Given that most consumers transition from home care to residential care, it would help if advocacy services were integrated into home care services.

An alternative would be to abandon the pursuit of competition and set up a system of enforced standards, funded for different categories of care along the lines of the casemix system used in hospitals.

…Or Regulate More Strongly On Their Behalf

Although this was recommended in the commission’s final report it would be harder to implement than it is in hospitals.

Aged care is about making life comfortable whereas health care is about fixing problems, making consumer preferences much more important in aged care.

Harnessing the power of consumer preferences is a worthy goal, and there is a great deal we can do to move toward it, but there’s a long way to go.![]()

Ou Yang, Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Anthony Scott, Professor, The University of Melbourne; Jongsay Yong, Associate Professor of Economics, The University of Melbourne, and Yuting Zhang, Professor of Health Economics, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New Treatment Stops Progression Of Alzheimer's Disease In Monkey Brains

In neglecting the National Archives, the Morrison government turns its back on the future

Why didn’t the federal government increase funding for the National Archives of Australia in its recent budget?

We know it wasn’t because of budget discipline. Money was splashed around on all sorts of worthy causes. And the emergency funding to save film and magnetic tape recordings from disintegration was modest: A$67 million over seven years.

Nor was it because a scorn for history is in the Liberal Party’s DNA. The party’s founder, Robert Menzies, was a history buff. His library, which is the centrepiece of the newly established Robert Menzies Institute at the University of Melbourne, is full of books of history and biography.

Moreover, his government established the precursor of today’s institution, the Commonwealth Archives Office, in 1961 so the records of the past could help guide the future. Prominent Liberals like Paul Hasluck and David Kemp have written histories, as has John Howard in The Menzies Era.

There are plenty of distinguished Liberal-aligned historians, and historians across the political spectrum supported the open letter to the prime minister, spearheaded by journalist Gideon Haigh and academic Graeme Davison.

Read more: Our history up in flames? Why the crisis at the National Archives must be urgently addressed

Some commentators have seen the failure to provide the archives with emergency funds as a skirmish in the culture wars against an intellectual and cultural left purported to be obsessed with identity politics. This, the argument goes, is of a piece with the government’s apparent hostility to universities, its increase in fees for humanities degrees and its parsimonious treatment of the arts.

But was it that deliberate? Perhaps it was just careless philistinism in a budget designed for a forthcoming election. It was a budget addressed primarily to groups of voters rather than to national problems, and the users of archives will never swing a marginal electorate. Last week, The Australian ran an editorial on the issue, which concluded: “Failure to fund the NAA properly is an oversight that must be corrected.”

The government is wrong to think it is only professional and academic historians who use the archives. So do family historians, as the archives include personal records of hundreds of thousands of Australians. They are especially relevant to those of non-Anglo descent who had to apply to government authorities for various exemptions and entry permits. These include Indigenous Australians, Chinese living in Australia or displaced persons wanting to immigrate.

Haigh has pointed out that Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s defence last year of his eligibility to sit in parliament depended on a document in the archives – the certificate of exemption from the provisions of the Immigration Act for his mother, then a seven-year-old girl deemed to be “stateless”.

The National Archives sit in the attorney-general’s department. Queensland Senator Amanda Stoker, who is assistant minister to the attorney-general as well as assistant minister for women and industrial relations, defended the government’s failure to provide the recommended emergency funding with the facile claim that “time marches on and all sources degrade over time”.

The government had nothing to be embarrassed about, she said, even when she was reminded Prince Charles had expressed his alarm at the threatened loss of records. Judging from her silly remarks, she seems to have given the subject little thought. The aim of the letter is to bring the archive’s budgetary neglect to the attention of the prime minister and his senior ministers.

Read more: Jenny Hocking: why my battle for access to the 'Palace letters' should matter to all Australians

While I do not think the neglect of the archives is a deliberate move in the culture wars, it is evidence of the Coalition’s truncated temporal imagination. This is in part an occupational hazard of politicians with their eyes on the electoral cycle. But it is also evident in the difficulty too many of the Coalition have in understanding what climate scientists have been telling them about the future, so they focus on present costs as if future costs will never arrive.

To understand the value of archives, we have to think not just about the past but about the future, when the present will be well and truly over. As the open letter says, the National Archives’ “most important users have not yet been born”, and we do not know what questions they will want to ask.

Thinking about time is difficult, wrenching oneself out of the dramas and routines of the present to fully imagine worlds that were and will be different, confronting our transience and our mortality.

Historians are experts in temporal imagining. They spend their days reading the words and examining the objects of the men and women who walked the world before us. We hope the prime minister will heed our words on the future’s desire for a memory bank of Australian life as full and rich as it can be.![]()

Judith Brett, Emeritus Professor of Politics, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Is it worth selling my house if I’m going into aged care?

For senior Australians who cannot live independently at home, residential aged care can provide accommodation, personal care and general health care.

People usually think this is expensive. And many assume they need to sell their home to pay for a lump-sum deposit.

But that’s not necessarily the case. Here’s what you need to consider.

Read more: So you're thinking of going into a nursing home? Here's what you'll have to pay for

You May Get Some Financial Support

Fees for residential aged care are complex and can be confusing. Some are for your daily care, some are means-tested, some are for your accommodation and some pay for extras, such as cable TV.

But it’s easier to think of these fees as falling into two categories:

an “entry deposit”, which is usually more than $A300,000, and is refunded when you leave aged care

daily “ongoing fees”, which are $52.71-$300 a day, or more. These cover the basic daily fee, which everyone pays, and the means-tested care fee.

To find out how much government support you’ll receive for both these categories, you will have a “means test” to assess your income and assets. This means test is similar (but different) to the means test for the aged pension.

Generally speaking, the lower your aged-care means test amount, the more government support you’ll receive for aged care.

With full support, you don’t need to pay an “entry deposit”. But you still need to pay the basic daily fee (currently, $52.71 a day), equivalent to 85% of your aged pension. If you get partial support, you pay less for your “entry deposit” and ongoing fees.

Read more: How to check if your mum or dad's nursing home is up to scratch

You Don’t Need A Lump Sum

You don’t have to pay for your “entry deposit” as a lump sum. You can choose to pay a rental-style daily cost instead.

This is calculated as follows: you multiply the amount of the required “entry deposit” by the maximum permissible interest rate. This rate is set by government and is currently at 4.01% per year for new residents. Then you divide that sum by 365 to give a daily rate. This option is like borrowing money to pay for your “entry deposit” via an interest-only loan.

You can also pay for your “entry deposit” with a combination of a lump sum and a daily rental cost.

As it’s not compulsory to pay a lump sum for your “entry deposit”, you have different options for dealing with your family home.

Option 1: Keep Your House And Rent It Out

This allows you to use the rental-style daily cost to finance your “entry deposit”.

Pros

you could have more income from rent. This can help pay for the rental-style daily cost and “ongoing fees” of aged care

you might have a special sentimental attachment to your family house. So keeping it might be a less confronting option

keeping an expensive family house will not heavily impact your residential aged care cost. That’s because any value of your family house above $173,075.20 will be excluded from your means test

you can still access the capital gains of your house, as house prices rise.

Cons

your rental income needs to be included in the means test for your aged pension. So you might get less aged pension

you might need to pay income tax on the rental income

compared to the lump sum payment, choosing the rental-style daily cost means you will end up paying more

you are subject to a changing rental market.

Read more: Home-owning older Australians should pay more for residential aged care

Option 2: Keep Your House And Rent It Out, With A Twist

If you have some savings, you can use a combination of a lump sum and daily rental cost to pay for your “entry deposit”.

Pros

like option 1, you can keep your house and have a steady income

the amount of lump sum deposit will not be counted as an asset in the pension means test.

Cons

like option 1, you could have less pension income, higher age-care costs and need to pay more income tax

you have less liquid assets (assets you could quickly sell or access), which could be handy in an emergency.

Option 3: Sell Your House

If you sell your house, you can use all or part of the proceeds to pay for your “entry deposit”.

Pros

if you have any money left over after selling your house and paying for your “entry deposit”, you can invest the rest

as your “entry deposit” is exempt from your aged pension means test, it means more pension income.

Cons

- if you have money left over after selling your house, this will be included in the aged-care means test. So you can end up with less financial support for aged care.

Read more: What adds value to your house? How to decide between renovating and selling

In A Nutshell

Keeping your house and renting it out (option 1 or 2) can give you a better income stream, which you can use to cover other living costs. And if you’re not concerned about having access to liquid assets in an emergency, option 2 can be better for you than option 1.

But selling your house (option 3) avoids you being exposed to a changing rental market, particularly if the economy is going into recession. It also gives you more capital, and you don’t need to pay a rental-style daily cost.

This article is general in nature, and should not be considered financial advice. For advice tailored to your individual situation and your personal finances, please see a qualified financial planner.

Correction: this article previously stated the amount of lump sum deposit will not be counted as an asset in the aged-care means test, as a pro of option 2. In fact, the amount of lump sum deposit will not be counted as an asset in the pension means test.![]()

Colin Zhang, Lecturer, Department of Actuarial Studies and Business Analytics, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our own Nomadland: the Australians caught in a COVID blind spot

Australians have been told to stay home during lockdowns to prevent the spread of COVID-19. While evidence of the efficacy of this approach as a public health strategy during a pandemic is compelling, lockdowns and mobility restrictions are inevitably disruptive for many – virtually everyone. However, a group that has largely been overlooked is Australia’s nomadic population. Periods of lockdown are particularly challenging for these people, who live in vans, RVs, caravans and boats.

The impacts of restrictions on small businesses, travellers, people in low-paid and insecure jobs who cannot work from home, school children and homeless people have all been widely reported. But with little known about Australia’s nomads, this group has been largely left to their own devices to find secure accommodation and navigate through mobility and border restrictions.

Read more: Australia's mishmash of COVID border closures is confusing, inconsistent and counterproductive

While nomads do not have a conventional single residential address, or live in a brick and mortar home, they are not homeless. Their van, RV, caravan or boat enables them to be permanently mobile while living in their permanent home.

The viability of their nomadic lifestyle depends on being able to freely move from place to place. Free movement enables nomads to access work and social networks as well as minimise living costs.

With the focus now on vaccinating Australians and working out longer-term strategies for managing COVID-19, more attention must be given to this permanently mobile population.

Who Are Nomads?

The recently released US film Nomadland follows the travels of a middle-aged woman who lives permanently in van. The film has raised awareness about the growing nomadic population in the US, and the complex economic and social drivers of this growth.

In modern societies, nomads are best thought of as a diverse group of people who are consciously seeking an alternative housing solution that enables them to balance their social and economic resources, needs and aspirations. Their lives and lifestyles are closely connected to life on the road. For those still in the workforce, a nomadic lifestyle can enable them to find seasonal work year-round.

In Australia, the term nomad has been most often associated with “grey nomads”, a broad group of people who are typically retired or semi-retired. They travel seasonally to warmer areas for winter and to cooler areas for summer.

Read more: Grey nomad lifestyle provides a model for living remotely

How Many Nomads Live In Australia?

Our new research has revealed the exact size and characteristics of the Australian nomad population are unknown and challenging to determine. Estimates vary dramatically from between 2,500 to 40,000, depending on how the group is defined.

Our official population statistics struggle to “capture” the realities of a whole range of population subsets that do not have one permanent place of “usual residence”, which compounds the challenge. The Australian Census, for example, has only three categories for residents: being “at home”, “away from home”, or homeless on census night.

Without knowing the size of the nomad population, it is difficult to determine if the population is growing or by how much. However, recent reports from the UK and US suggest that, largely in response to financial pressures, those countries’ nomadic populations have grown.

As Australia’s property market tightens and housing affordability worsens, it is plausible that more people may opt to sell up their brick and mortar assets (or rent these out for an income) to live a more affordable nomadic lifestyle.

Read more: Soaring housing costs are pushing retirees into areas where disaster risks are high

Searching For A Place To Stay

The closure of national and state parks and informal camping grounds has caused problems for permanent grey nomads. While they are not homeless – their van, RV, caravan or boat is their home – the closure of parks and camping grounds forces them to find alternative safe locations.

For those who are working, travel is often planned to align with seasonal work needs in particular areas. Mobility restrictions and border closures are particularly problematic for those who rely on seasonal work.

An underpinning assumption of Australia’s public health measures to restrict the spread of COVID is that homes are generally not mobile and that people can remain within a location – albeit with disruption. Better information about the size, routes and characteristics of Australia’s nomad population may improve capacity to support them during periods of restrictions.

The Rise Of The Digital Nomad

While COVID-19 restrictions have thrown up many challenges, it appears opportunities are also emerging. Globally, many workplaces are moving work online and the digital nomad population has grown.

Digital nomads are people who work online to maintain a nomadic lifestyle.

So, while there is an urgent need to better ensure Australia’s nomads receive the supports and services they need during COVID-19 lockdowns and more broadly, it’s also worth keeping an eye on the growth of the digital nomad population. We need to consider what might be necessary to support this growing population into the future.![]()

Amanda Davies, Professor of Human Geography, The University of Western Australia and Sarah Prout Quicke, Senior Lecturer, School of Social Sciences, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW Government’s Cost Of Living Service

Kanlaya Turns Three!

On Monday 14 June, Asian Elephant calf Kanlaya at Taronga Western Plains Zoo celebrated her third birthday with a special enrichment feed.

Kanlaya has really blossomed over the past three years. In the beginning she was quite shy but now she is an engaged learner who is keen to interact with her keepers and is a very social and playful calf.

Kanlaya is always busy and enjoys playing with four-year-old Sabai. They can be found out in the paddock running around together, fishing for apples in the pool or rolling in the mud.

“We often see Kanlaya alongside her aunty Thong Dee having a swim in the pool when it is raining which is also very special,” said Elephant Keeper Jackie Cantrell.

Over the past 12 months Kanlaya has become more and more independent and playful. Guests to the Zoo would regularly see her on the other side of the paddock to her mum or aunty and she’ll be climbing or rubbing on logs, chasing birds or following Pathi Harn or Sabai around.

Kanlaya and four-year-old Sabai. Photo by Rick Stevens, Taronga Zoo media

There is so much development that happens for an elephant calf in the first few years of life. Some of these major milestones that Kanlaya has developed include learning to use her truck proficiently, being interested in the food mum is eating and beginning to consume solid food herself, slowly reducing milk intake from mum and learning how to behave around other elephants.

“One interesting aspect about Kanlaya’s growth and development is her weight gain. In the three years she has gained approximately 1100kgs, compared to Gung our adult bull elephant who has only put on 400kgs in the past three years,” said Jackie.

Kanlaya at one year of age. Photo: Taronga Zoo

Seeing Kanlaya be born and watching her grow over the past three years has been a very rewarding experience for many of the keepers.

“Being present to witness the birth of an elephant calf is pretty amazing and an opportunity very few people get to be a part of but it is even more special to be able to foster a relationship with Kanlaya and see her grow and develop.”

“Hopefully I will be present to see her eventually come full circle from calf to a mother of her own calf one day in the future, this would be an incredibly momentous occasion in my life as well as hers,” said Jackie.

Kanlaya was the second calf born here in Dubbo and our first female calf. A lot of planning and preparation goes in to any birth and Kanlaya’s was no exception.

Back track to September 2016, we were training Porntip for Artificial Insemination (AI) and taking regular blood samples from her to track her progesterone levels. By measuring her progesterone levels, we can actually determine the exact day that she will ovulate and time the AI for that day. This requires a lot of planning and preparation, particularly because Kanlaya’s dad does not live in Dubbo, he lives at Perth Zoo in Western Australia. So we organised all the logistics and then a team of specialist elephant reproductive vets flew to Perth to be ready. We took blood on the morning of the 7 September 2016 and the results confirmed ovulation. The team in Perth collected the semen sample straight away and then flew to Dubbo, via Sydney and arrived early that evening. We did the artificial insemination at 8.30pm and the vets were fairly confident because the semen sample was great, 90% motility, and they could see on ultrasound that Porntip had just ovulated. We did a second artificial insemination procedure the following morning to be sure.

We then had to wait approximately three months (the length of an elephant cycle) before we could confirm that Porntip was pregnant and it was at this point we found out it was a success! And then we started the long 22 months wait until our little calf would arrive.

Kanlaya was born on the 14th of June 2018 at 3.07am after a short and easy labour. Her name means ‘beautiful lady’. She is a very confident, playful and energetic calf. Kanlaya spends her the day with the herd and often leads the way out on to exhibit. She loves receiving attention and her training is coming along nicely.

Her Mum is Porntip and is 28 years old. She has a laid back and easy going personality and is very maternal. Porntip is a great mother and aunty to the other calves in the herd.

Kanlaya’s dad Putra Mas lives at Perth Zoo with two other female elephants. Kanlaya is the first calf he has sired. Putra Mas is exceptionally smart and seeks out attention from keepers to do activities, vocalizing to call them over. Keepers at Perth Zoo say he is a perfectionist and learns new behaviours quickly. Putra Mas is a big burley boy, is destructive and loves to play with his toys. If he can break it, he will.

As Kanlaya grows and develops it is nice to see her personality coming out and the different traits she gets from her parents. It is a real pleasure to watch her grow and develop.

By Elephant keeper, Bec O’Riordan and Taronga Zoo

Solid Plastering: Artisans Of Australia

Do You Want To Be A Radio Broadcaster?

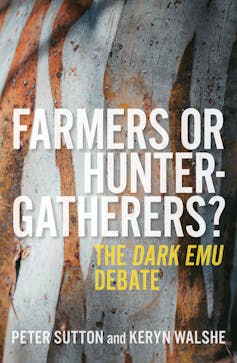

Book review: Farmers or Hunter-gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate rigorously critiques Bruce Pascoe’s argument

Eminent Australian anthropologist Peter Sutton and respected field archaeologist Keryn Walshe have co-authored a meticulously researched new book, Farmers or Hunter-gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate. It’s set to become the definitive critique of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu: Black Seeds — Agriculture or Accident?

First published in 2014, Pascoe’s Dark Emu has spawned numerous derivatives. Pascoe contends that in pre-contact times, Australian Aboriginal people weren’t “mere” hunter-gatherers, but agriculturalists. Descriptors like “simple” or “mere” are anathema to people like me who’ve lived long-term with hunter-gatherers.

For many Australians, Pascoe’s book is a “must-read”, speaking truth to power. For such readers, Dark Emu seems a breakthrough text. Not so, in Sutton and Walshe’s estimation. Nor mine.

Underpinning Dark Emu is the author’s rhetorical purpose. This proselytising is partly achieved by painstaking “massaging” of his sources, a practice forensically examined by Walshe and Sutton. It has led to converts to Pascoe’s dubious proposition. But this willingness to accept Pascoe’s argument reveals a systemic area of failure in the Australian education system.

On the basis of long-term research and observation, Sutton and Walshe portray classical Australian Aboriginal people as highly successful hunter-gatherers and fishers. They strongly repudiate racist notions of Aboriginal hunter-gatherers as living in a primitive state.

In their book, they assert there was and is nothing “simple” or “primitive” about hunter-gatherer-fishers’ labour practices. This complexity was, and in many cases, still is, underpinned by high levels of spiritual/cultural belief.

Not Agriculturalists

As Sutton attests, seeds were and are occasionally deliberately scattered. But in classical Aboriginal societies they were never planted nor watered for agricultural purposes. Such aforementioned rituals are collectively called “increase ceremonies”. Sutton’s alternative term, “maintenance ceremonies”, invokes spiritual propagation as opposed to oversupply.

Their objective was continuing subsistence. Australia’s hunter-gatherer-fishers left an extremely light carbon footprint — the diametric opposite of many contemporary agricultural/industrial practices. The photo below, taken in 1932 or earlier, shows Pilbara people throwing yelka (nutgrass) — not threshing or scattering seeds.

Pascoe’s Sources And Approach

Pascoe draws on records of explorers and early colonists, also citing recent works, including Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Dark Emu leans most heavily on the work of the late historian/ethnographer Rupert Gerritsen.

Read more: Friday essay: Dark Emu and the blindness of Australian agriculture

Counter-intuitively, Pascoe mainly cites non-Aboriginal sources. There is no real “voice” given to the few remaining people who lived traditional lives as youngsters, or are cited in books or articles.

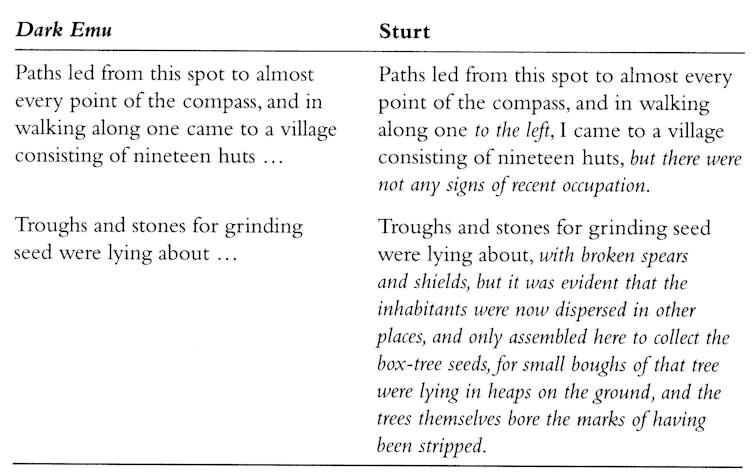

While some have described Dark Emu as fabrication, Sutton and Walshe are more measured. They methodically show that in Dark Emu, Pascoe has removed significant passages from publications that contradict his major objectives. This boosts his contention that all along Aboriginal people were farmers and/or aquaculturalists.

One example concerns Pascoe’s quoting of the journal entries of the explorer Charles Sturt. Sutton writes:

Sturt is quoted [by Pascoe] on his party’s discovery of a large well and ‘village’ of 19 huts somewhere north of Lake Torrens in South Australia.

This “village” concept arose from colonial records, and is still sometimes used in recent articles.

Pascoe’s edit of Sturt’s original 1849 text breathes oxygen into Dark Emu’s polemical edge. It’s misleading at best. For Sturt’s diary reveals Aboriginal people didn’t live in “houses” in any single site all year round.

Such accounts destabilise Pascoe’s argument, reinforced by ethnographic, colonial, and archaeological records.

Hunter-gatherers did alter the country in significant ways — most Australians know about the ancient practice of firing the country, recently discussed in depth owing to our increasingly devastating bush-fires. This involved ecological agency and prowess. But expert fire-burning isn’t an agricultural practice, as Pascoe avers.

Misidentification Of Implements

In a key chapter, Walshe homes in on Pascoe’s mis-interpretations of hunter-gatherer implements, which he labels “agricultural” tools. For instance, Pascoe misconstrues grooved “Bogan Picks” as heavy stones used for agricultural activity.

Walshe disputes Pascoe’s claim, stating that, “with their adze-shaped end and grooved midline for hafting, they were likely used in a similar way to stone axes.”

Wooden digging sticks were also used for breaking up the earth to extract yams when in season, among various other purposes — not for “tilling” or “ploughing” the soil in preparation for planting seeds.

Language used by early colonists and explorers — words like “village” and “picks” — befuddles readers. British colonists’ monolingualism meant they used English words, often imposed arbitrarily, to name never-before-seen hunter-gatherer implements. For example, “Bogan Pick” references the nearby Bogan River.

Hunter-Gatherer Mobility And Stasis

Sutton expertly summarises the experience of escaped convict, William Buckley, who spent 32 years travelling around country with the Wathawurrung people in Central Victoria.

Over time, Buckley became fluent in the language of his Wathawurrung hosts. Later, his oral account of the hunter-gatherer group’s approximate lengths of mobility and stasis at numerous sites was transcribed. It’s a unique document covering a significant timespan.

This account reinforces earlier chapters in Dark Emu Debate. Sutton and Walshe make it crystal clear that Aboriginal people weren’t “simple nomads” wandering around randomly, opportunistically searching for food and water. They knew their country intimately.

Rather, hunter-gatherers engaged in purposeful travel to sites with which they familiar and able to source seasonally available food, water and shelter at variable times of year.

Another conspicuous weakness in Dark Emu’s approach, pinpointed by Sutton and Walshe, is Pascoe’s penchant for choosing exceptions to the general rule, implying that these atypical practices were widespread or universal. It’s another strategy to consolidate his argument but involves eliding vital information.

Pre-Contact Aquaculture

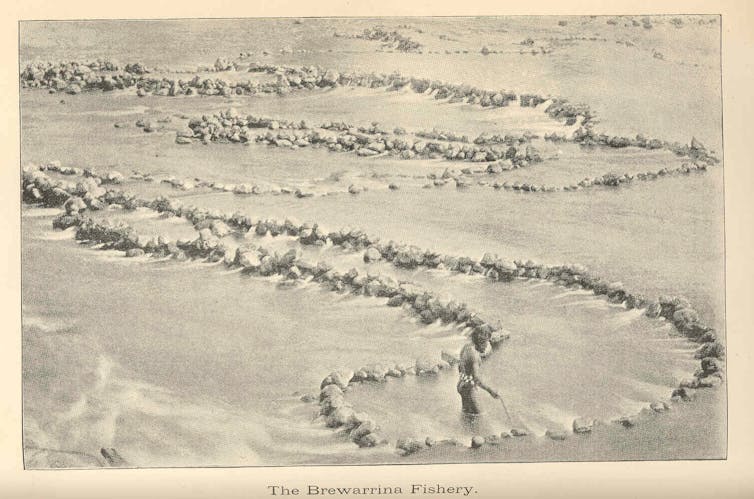

Pascoe offers two examples of “aquacultural” practice, one in Brewarrina (NSW) in the bed streams of the Barwon River, and the other in Lake Condah, in south-western Victoria.

He seizes on rock use in the Brewarrina fishery and Lake Condah’s fish and seasonal eel trapping as “proof” of Aboriginal people’s aqua/agricultural prowess — giving the impression they created these complex hydrological systems from scratch.

But Sutton writes, “The fish traps of Brewarrina … were not claimed as the ingenious works of human beings, but … regarded as having been put there in the Dreaming, by Dreamings.” Both he and Walshe readily acknowledge the fact that Aboriginal people use/d their human agency to create modifications. It’s not an either/or matter.

However, a chapter written by Walshe throws light on the seismic activity that forged Lake Condah’s unique terrain and waterways. This area, she writes, is part of

a volcanic system … last active … 9,000 years ago, with a major eruption much earlier, about 37,000 thousand years ago, causing a massive lava flow across the pre-existing drainage system.

The natural tilt southwards, she explains, facilitated “naturally formed ancient river channels … to reach the Southern Ocean”.

This enabled migratory fish to spawn. Fish, and at certain times of year, eels, swam through both fresh and salty water — making for ease of catching. Local Aboriginal people moved the heavy stones into semi-circular formations to enable netting, spearing or grabbing by hand, possibly creating further semi-captivity of these food staples.

In this way, hunter-gatherers consistently and constantly “value-added” to, or enhanced, nature’s creation.

Read more: The detective work behind the Budj Bim eel traps World Heritage bid

Not A Bunfight

Pascoe’s skilful editing of his sources involves conscious, deliberate intervention. Does he hope Dark Emu will convince people to change their belief in the noxious evolutionary ladder, once uniformly, but still sometimes, applied to different groups of homo sapiens?

Or was his book written to prove Aboriginal people were/are more like Europeans, which could perhaps lead to much needed progress on reconciliation? Perhaps that accounts for its rapturous reception by many Australians, especially the young.

Why not simply celebrate the long-term achievements of hunter-gatherers?

Hunter-gatherers worked in concert with the natural world, not against it as most humans do today, resulting in insoluble difficulties such as overcrowding, pandemics and toxic agricultural and aquacultural practices. Survival depends on this. For eons, it ensured the continuity and the continuing existence of Australia’s hunter-gatherer people and their culture.

Farmers or Hunter Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate needs to be read carefully, keeping an open mind. The book’s focus is on both material and spiritual economies and their misrepresentation. Despite racist commentary from some, this isn’t an exclusively right or left-wing issue or a bunfight.

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu will continue to be granted recognition, if not immortality. But Sutton and Walshe’s Dark Emu Debate will undoubtedly be acclaimed. As a critique of Pascoe’s book, it’s just about perfect — a volume with the twin virtues of rigour and readability.

Farmers or Hunter Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate is published by Melbourne University Press and will be released 16 June 2021.![]()

Christine Judith Nicholls, Honorary Senior Lecturer, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

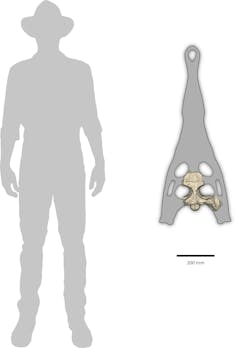

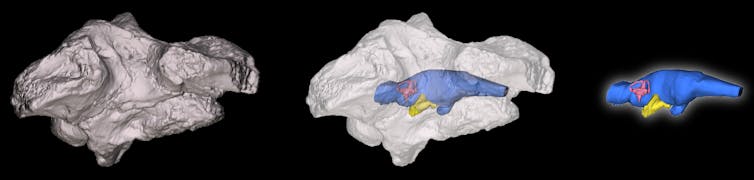

This deep-sea creature is long-armed, bristling with teeth, and the sole survivor of 180 million years of evolution

Let me introduce you to Ophiojura, a bizarre deep-sea animal found in 2011 by scientists from the French Natural History Museum, while trawling the summit of a secluded seamount called Banc Durand, 500 metres below the waves and 200 kilometres east of New Caledonia in the southwest Pacific Ocean.

Ophiojura is a type of brittle star, which are distant cousins of starfish, with snake-like arms radiating from their bodies, that live on sea floors around the globe.

Being an expert in deep-sea animals, I knew at a glance that this one was special when I first saw it in 2015. The eight arms, each 10 centimetres long and armed with rows of hooks and spines. And the teeth! A microscopic scan revealed bristling rows of sharp teeth lining every jaw, which I reckon are used to snare and shred its prey.

As my colleagues and I now report in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Ophiojura does indeed represent a totally unique and previously undescribed type of animal. It is one of a kind — the last known species of an ancient lineage, like the coelacanth or the tuatara.

We compared DNA from a range of different marine species, and concluded that Ophiojura is separated from its nearest living brittle star relatives by about 180 million years of evolution. This means their most recent common ancestor lived during the Triassic or early Jurassic period, when dinosaurs were just getting going.

Since then, Ophiojura‘s ancestors continued to evolve, leading ultimately to the situation today, in which it is the only known survivor from an evolutionary lineage stretching back 180 million years.

Amazingly, we have found small fossil bones that look similar to our new species in Jurassic (180 million-year-old) rocks from northern France, which is further evidence of their ancient origin.

Scientists used to call animals like Ophiojura “living fossils”, but this isn’t quite right. Living organisms don’t stay frozen in time for millions of years without changing at all. The ancestors of Ophiojura would have continued evolving, in admittedly very subtle ways, over the past 180 million years.

Perhaps a more accurate way to describe these evolutionary loners is with the term “paleo-endemics” — representatives of a formerly widespread branch of life that is now restricted to just a few small areas and maybe just a single solitary species.

For seafloor life, the centre of palaeo-endemism is on continental margins and seamounts in tropical waters between 200 metres and 1,000 metres deep. This is where we find the “relicts” of ancient marine life — species that have persisted in a relatively primitive form for millions of years.

Read more: Dancing brittle stars tell an ancient tale of life and death in brutal seas

Seamounts, like the one on which Ophiojura was found, are usually submerged volcanoes that were born millions of years ago. Lava oozes or belches from vents in the seafloor, continually adding layers of basalt rock to the volcano’s summit like layers of icing on a cake. The volcano can eventually rise above the sea surface, forming an island volcano such as those in Hawaii, sometimes with coral reefs circling its shoreline.

But eventually the volcano dies, the rock chills, and the heavy basalt causes the seamount to sink into the relatively soft oceanic crust. Given enough time, the seamount will subside hundreds or even thousands of metres below sea level and gradually become covered again in deep-sea fauna. Its sunlit past is remembered in rock as a layer of fossilised reef animals around the summit.

Voyage Of Discovery

While our new species is from the southwest Pacific, seamounts occur worldwide and we are just beginning to explore those in other oceans. In July and August, I will lead a 45-day voyage of exploration on Australia’s oceanic research vessel, the RV Investigator, to seamounts around Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the eastern Indian Ocean.

These seamounts are ancient - up to 100 million years old — and almost totally unexplored. We are truly excited at what we may find.

Seamounts are special places in the deep-sea world. Currents swirl around them, bringing nutrients from the depths or trapping plankton from above, which feeds the growth of spectacular fan corals, sea whips, and glass sponges. These in turn host numerous other deep-sea animals. But these fascinating communities are vulnerable to human activities such as deep-sea trawling and mining for precious minerals.

The Australian government recently announced a process to create new marine parks in the Christmas and Cocos (Keeling) regions. Our voyage will provide the data required to manage these parks into the future.

The New Caledonian government has also created a marine park in offshore areas around these islands, including the Durand seamount. These marine parks are beacons of progress in the global drive for better environmental stewardship of our oceans. Who knows what weird and wonderful treasures of the deep are yet to be discovered.

Read more: How we traced the underwater volcanic ancestry of Lord Howe Island ![]()

Tim O'Hara, Senior Curator of Marine Invertebrates, Museums Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

9 in 10 LGBTQ+ students say they hear homophobic language at school, and 1 in 3 hear it almost every day

Bills in the federal and New South Wales parliaments have sought to stop teachers talking about gender and sexuality diversity in the name of either religious freedom or parents’ rights.

If passed in its current form, the NSW Education Legislation Amendment (Parental Rights) Bill 2020 would prohibit teachers from discussing gender and sexuality diversity. It would also make offering targeted, requested support to gender and sexuality diverse (often known as LGBTQ+) students grounds for revoking teachers’ accreditation.

At NSW universities, the bill will mean programs that educate student teachers about the existence of LGBTQ+ students and how best to support them at school would be at risk of losing their accreditation. The same goes for registered professional development of NSW teachers.

Such bills fail to acknowledge the daily realities for many LGBTQ+ youth. These young people experience one of the highest rates of school bullying in the Asia-Pacific and are almost five times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers.