inbox and environment news: Issue 500

June 27 - July 10, 2021: Issue 500

More Time To Have Your Say On Ingleside Housing Development Proposal

Funding For Careel Creek Improvements

Biodiversity Offsetting Should Only Be Used As A Last Resort And Adhere To International Best Practice

- The effectiveness of the scheme to halt or reverse the loss of biodiversity values, including threatened species and threatened habitat in NSW, the role of the Biodiversity Conservation Trust in administering the scheme and whether the Trust is subject to adequate transparency and oversight;

- The adequacy of the use of offsets by the NSW Government for major projects and strategic approvals;

- The impact of non-additional offsetting practices on biodiversity outcomes, offset prices and the opportunity for private landholders to engage in the scheme; and

- Any other related matters.

- That the committee report by March 1, 2021.

Whole Lot Closer To Keeping Bromadiolone Out Of Bird Food Chains

Platypus Numbers At Penrith

- Abide by NSW Government laws and use approved yabby fishing traps.

- Ensure you take your rubbish with you and dispose of your litter correctly and in a bin.

- Keep the vegetation surrounding the creeks in top condition by keeping it litter free and undisturbed.

Federal Consultation On Endangered Listing For The Koala Now Open - Closes July 30, 2021

Koala Listing Strengthens Call For An Independent Environmental Compliance Agency

Draft National Recovery Plan For The Koala (Combined Populations Of Queensland, New South Wales And The Australian Capital Territory)

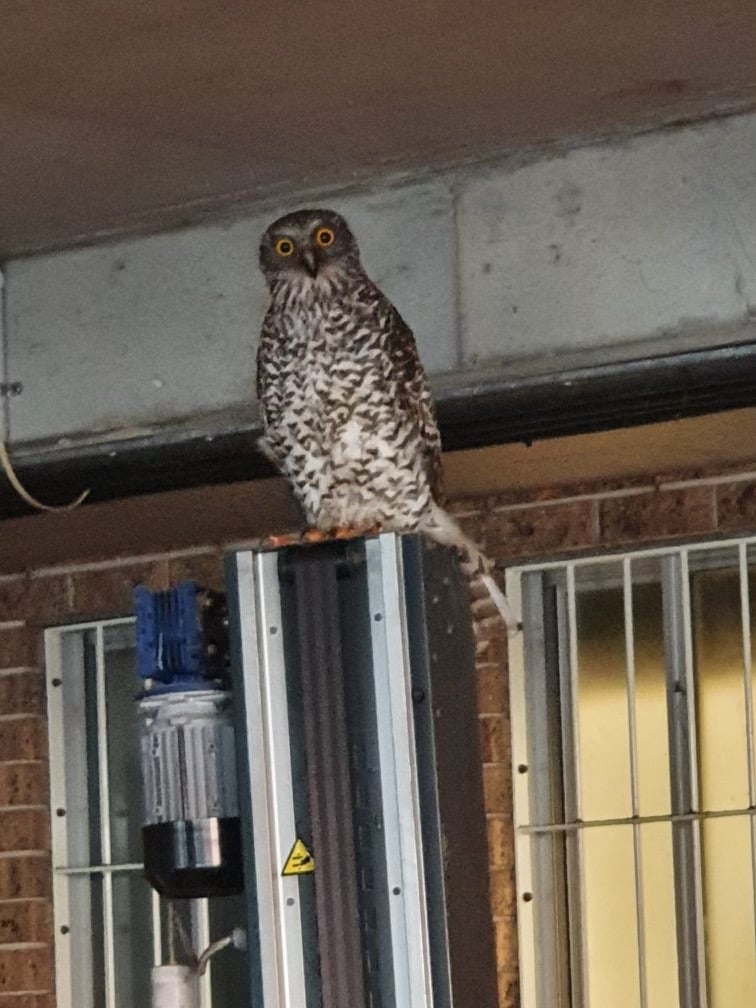

The Powerful Owl Project Update

NSW Budget For The State's Biodiversity

- More than $193 million over five years to deliver on our goal to double the number of koalas in New South Wales by 2050

- $75 million over five years to continue the Saving Our Species Program to maximise the number of ecological communities and threatened species that are secure in the wild in New South Wales

- More than $26 million over two years to implement key actions under the Land Management and Biodiversity Conservation framework including implementation of the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme, and biodiversity mapping, assessment and evaluation

- More than $140 million to manage waste, clean-up and ongoing recovery works as a result of bushfires and floods

- More than $80 million over three years to deliver new signature walking and tourism experiences in NSW national parks.

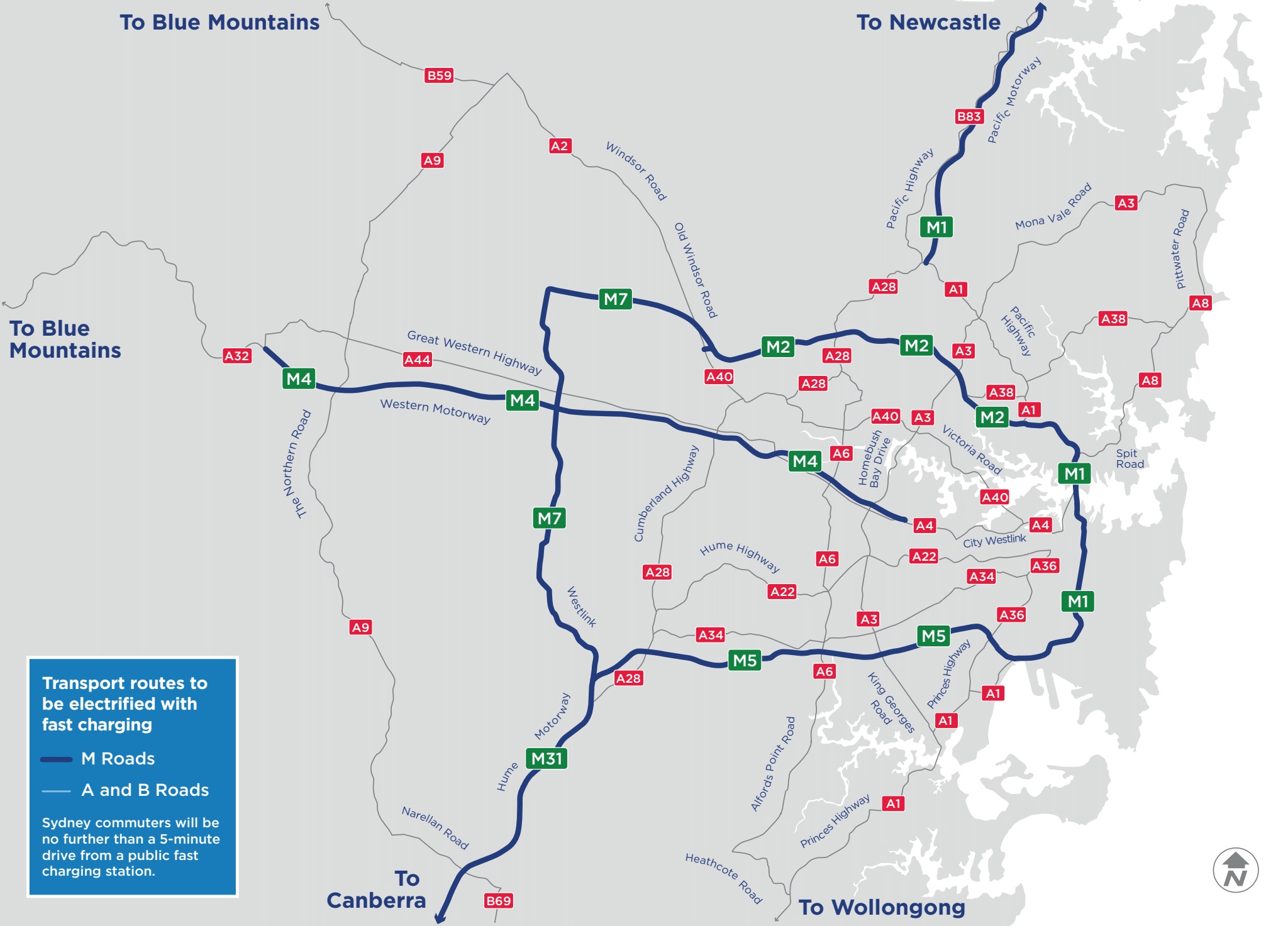

NSW Leading The Charge With Electric Vehicle Rev-Olution

- Stamp duty will be waived for eligible electric vehicles (battery and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles) priced under $78,000 purchased from 1 September 2021;

- Rebates of $3,000 will be offered on private purchases of the first 25,000 eligible EVs (battery and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles) under $68,750 sold in NSW from 1 September 2021;

- $171 million for new charging infrastructure across the State. This includes $131 million to spend on new ultra-fast vehicle chargers, $20 million in grants for destination chargers to assist regional tourism, and $20 million for charging infrastructure at public transport hubs on Transport for NSW owned land.

- $33 million to help transition the NSW Government passenger fleet to EVs where feasible, with the target of a fully electric fleet by 2030. These vehicles typically are onsold after three to five years, providing availability for private buyers in the second hand market.

Cramming cities full of electric vehicles means we’re still depending on cars — and that’s a huge problem

This week, the NSW government announced almost A$500 million towards boosting the uptake of electric vehicles. In its new electric vehicle strategy, the government will waive stamp duty for cars under $78,000, develop more charging infrastructure, offer rebates to 25,000 drivers, and more.

Given the transport sector is Australia’s second-largest polluter, it’s a good thing Australian governments are starting to plan for a transition to electric vehicles (EVs).

But transitioning from cities full of petrol-guzzling vehicles to cities full of electric ones won’t address all of the environmental and social problems associated with car dependence and mass manufacturing.

So, let’s look at these problems in more detail, and why public transport really is the best way forward.

Mounting Disadvantage And Health Issues

EVs do have environmental advantages over conventional vehicles. In particular, they generate less carbon emissions during their lifetime. Of course, much of the emissions reductions will depend on how much electricity comes from renewable sources.

But carbon emissions are only one of the many problems associated with the dominance of private cars as a form of mobility in cities.

Let’s start with a few of the social issues. This includes the huge amount of space devoted to car driving and parking in our neighbourhoods. This can crowd out other forms of land use, including other more sustainable forms of mobility such as walking and cycling.

There are the financial and mental health costs of congestion, as well, with Australian city workers spending, on average, 66 minutes getting to and from work each day. Injuries and fatalities on roads are also increasing, and inactivity and isolation associated with driving can impact our physical health.

Car-dependent cities also contribute to disadvantage for people who don’t have access to cars, and uneven financial vulnerability associated with the high costs of car ownership and use.

Indeed, some of these problems could be made worse — for instance, subsidies for EVs could end up favouring wealthier people who can afford new cars.

Read more: Top economists call for budget measures to speed the switch to electric cars

Mining For Resources

A mass global uptake of EVs will generate major environmental problems, too. Most concerning of these is the use of finite mineral resources required for their construction, and the environmental and labour conditions of their extraction.

This was recently highlighted in a recent report by the International Energy Agency. As the agency’s executive director Fatih Birol said, there’s a

looming mismatch between the world’s strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals that are essential to realising those ambitions.

Minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and copper are key ingredients required to make EVs.

As the report noted, EVs use double the amount of copper than conventional vehicles. EVs also require considerable amounts of lithium, cobalt and graphite that are hardly required at all for conventional vehicles. And it expects demand for lithium to grow 40-fold between 2020 and 2040, driven by EV production to meet climate targets.

There is considerable discussion of Australia’s natural advantage as a supplier of some of these minerals, as we have large reserves of lithium and rare-earth metals beneath parts of the continent.

But before governments and mining bodies rush to exploit these reserves, they need to ensure much more is done to avoid the injustices perpetrated against Traditional Owners and their lands and heritage. The recent appalling destruction at Juukan Gorge by Rio Tinto’s iron ore operation is just one example of this.

Read more: Rio Tinto just blasted away an ancient Aboriginal site. Here’s why that was allowed

Mining also has its own environmental problems, such as land clearing and associated biodiversity loss, the pollution and contaminants it produces, and intensive water use.

The conditions of extracting these critical minerals in other parts of the world are dire. There’s the oppressive working conditions in cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the conflict over Indigenous rights in Chile’s lithium mining areas, and environmental destruction associated with mining rare earth minerals in China.

Broadening Ideas About Transport

To focus on these problems is not to suggest the new policies on electric vehicles are unimportant, or that they don’t stand to have some positive environmental impact.

The point is private EVs are not a solution to the combined challenges of reducing our urban environmental footprints and making better cities for all, and that they have their own problems.

Instead, we should develop a good mass public transport system with extensive and frequent coverage. Alongside urban development with a more even distribution of jobs, services and opportunities, investing in better public transport could reduce car dependence in our cities.

This would have a range of environmental and social benefits: making more space available for people instead of machines, extending the benefits of mobility to people who can’t or don’t drive, and reducing demand for finite minerals.

Even fossil-fuelled public transport has fewer emissions than conventional car travel. Data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change shows the most fuel-efficient buses and trains generate less than half the carbon emissions per passenger kilometre of fuel-efficient cars. Of course, public transport powered by renewables will be even better.

But as things stand, we are far from having such a city. The benefits of good public transport and public services are unevenly distributed across our cities.

In Sydney, for example, there are significant investments in new public transport infrastructure in some parts of the city, such as Metro West and the recently completed North West Metro. There are welcome commitments to reduce emissions in that sector, too.

But we’re a long way from planning new developments and redevelopments to make public transport a viable alternative to cars. The lack of public transport infrastructure in newly constructed, master-planned estates on Sydney’s urban fringe is the most glaring example.

Read more: Climate explained: the environmental footprint of electric versus fossil cars

Ultimately, it’s important that a transition to electric vehicles doesn’t dominate the discussion we need to have about urban transport.

Our challenge is to simultaneously reduce the carbon footprint of different forms of transport, while also thinking much more broadly about the sustainability and justice of the system of mobility that’s so central to daily life in our cities.![]()

Kurt Iveson, Associate Professor of Urban Geography and Research Lead, Sydney Policy Lab, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UN World Heritage Committee Draft Report Finds Great Barrier Reef In Danger

Australian Government’s Climate Inaction To Blame For Reef World Heritage ‘In Danger’ Recommendation

Senate Must Reject Nationals' Attempts To Further Undermining The Basin Plan

Floodplain Harvesting Inquiry Is A Chance To Clear The Air After Government’s Failed Floodwater Giveaway

- the NSW Government’s management of floodplain harvesting, including:

- The legality of floodplain harvesting practices;

- The water regulations published on 30 April 2021;

- How floodplain harvesting can be licensed, regulated, metered and monitored so that it is sustainable and meets the objectives of the Water Management Act 2000 and the Murray-Darling Basin Plan; and

- Any other related matters.

Woodside’s Scarborough Gas Field Equivalent To 15 New Coal Power Plants; Risks Murujuga Rock Art

New Community Recycling Centre Opens On Central Coast

The Central Coast has its first Community Recycling Centre, with householders now able to drop off their problem wastes such as paints, oils, gas bottles, fluoro lights, smoke detectors and batteries for free at the Buttonderry Waste Management Facility in Jilliby, near Wyong.

The Central Coast has its first Community Recycling Centre, with householders now able to drop off their problem wastes such as paints, oils, gas bottles, fluoro lights, smoke detectors and batteries for free at the Buttonderry Waste Management Facility in Jilliby, near Wyong.- water-based and oil-based paints

- used motor oils and other oils

- lead-acid and hand-held batteries

- gas cylinders and fire extinguishers

- conventional tube and compact fluorescent lamps and

- smoke detectors

EPA Shows The Easy Way To Compost

Forget Nutbush - It's Mint-Bush City Limits As Royal Reveals Her Secrets

Mark Vaile Withdrawal Proof Whitehaven Coal Is Untouchably Toxic Environment Groups State

The government’s idea of ‘national environment standards’ would entrench Australia’s global pariah status

Martine Maron, The University of Queensland; Brendan Wintle, The University of Melbourne, and Craig Moritz, Australian National UniversityA growing global push to halt biodiversity decline, most recently agreed at the G7 on Sunday, leaves Australia out in the cold as the federal government walks away from critical reforms needed to protect threatened species.

The centrepiece recommendation in a landmark independent review of Australia’s national environment law was to establish effective National Environment Standards. These standards would have drawn clear lines beyond which no further environmental damage is acceptable, and established an independent Environment Assurance Commissioner to ensure compliance.

But the federal government has instead pushed ahead to propose its own, far weaker set of standards and establish a commissioner with very limited powers. The bill that paves the way for these standards is currently before parliament.

If passed, the changes would entrench, or even weaken, already inadequate protections for threatened species. They would also create more uncertainty for businesses affected by the laws.

Australia’s Ineffective Environment Law

Australia is one of only a handful of megadiverse countries. Most of our species occur nowhere else — 87% of our mammals, 93% of our reptiles, and 94% of our frogs are found only here in Australia.

Yet, Australia risks global pariah status on biodiversity. Last week, threatened species experts recommended the koala be listed as endangered, despite a decade of protection under national environmental law. And this week, a UNESCO World Heritage committee recommended the Great Barrier Reef be listed as “in danger”.

Indeed, Australia has one of the worst track records in the world for biodiversity loss and species extinctions.

Australia’s national environment law — the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act — was introduced 20 years ago, and has not slowed extinction rates. In fact, threatened species populations are declining even faster.

This isn’t surprising, given the lack of mandated funding for threatened species and ecosystems recovery, poor enforcement of the law, and the lack of outcome-based environmental standards. It has allowed for hit after hit on important habitats to be approved.

The independent review of the EPBC Act, led by former competition watchdog chair Professor Graeme Samuel, set out how Australia can turn this around.

Samuel concluded the EPBC Act is no longer fit for purpose, and set out a comprehensive list of recommended reforms, founded upon establishing new, strong national environmental standards.

And he included an explicit warning: do not cherrypick from these recommendations.

Double Standards

So how do the government’s proposed standards, released in March, compare to the Samuel review’s recommended version?

The Samuel review’s standards specified what environmental outcomes must be achieved by decisions made under the EPBC Act, such as whether a particular development can go ahead. For example, the standards would have required that any actions must cause no net reduction in the population of endangered and critically endangered species.

Read more: To fix Australia's environment laws, wildlife experts call for these 4 changes — all are crucial

Samuel developed these standards by consulting multiple sectors, and attracted general support. The government’s proposed standards bear no resemblance to these.

Instead, the government’s proposed standards repeat sections of the existing EPBC Act, adding zero clarity or specificity about the outcomes that should be achieved.

Standards like these risk significant and irreversible environmental harm being codified. They are the antithesis of the global push for outcomes-based, nature-positive standards.

The bill underpinning the standards would let actions be approved even if they caused substantial environmental harm, as long as the decision maker — currently the federal environment minister — believed other activities would render the overall outcome acceptable.

To help illustrate this, let’s say a mining operation would lead to significant destruction of koala habitat. The decision maker could consider this acceptable if they thought an unrelated tree-planting program would offset the risk to the koala — even if they had no say over whether the tree planting ever actually went ahead.

What about the responsibilities of the Environment Assurance Commissioner? Samuel recommended this commissioner would oversee the implementation of the standards, and ensure transparency.

But the government’s proposed Environment Assurance Commissioner would be prevented from scrutinising individual decisions made under the EPBC Act.

So, hypothetically, if a risky decision was being made — such as approving new dam that could send a turtle species extinct — checking if the decision complied with required standards would be beyond the commissioner’s remit. Instead, the commissioner would focus on checking processes and systems, not ensuring environmental outcomes are achieved.

Read more: A major report excoriated Australia's environment laws. Sussan Ley's response is confused and risky

The deficiencies in the proposed standards have caught the attention of Queensland environment minister Meaghan Scanlon. Last year, the federal government introduced a different bill that would allow it to hand its responsibility for approving actions under the EPBC Act to the states. But Scanlon says the state won’t partake in this re-alignment of responsibility, unless the federal government introduces stronger national environment standards.

They’ve also caught the attention of the key cross-bench senators, whose support will ultimately determine whether the government’s standards prevail.

Getting Left Behind

With such a rich diversity of wildlife, Australia has a disproportionate responsibility to protect the Earth’s natural heritage. And we owe future generations the opportunity to experience the amazing nature we’ve grown up with.

If we are to turn around Australia’s appalling track record on biodiversity, the government’s proposed standards are not a good place to start.

In October, nations worldwide will agree to a new global strategy for protecting biodiversity, under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The strategy looks set to include a roadmap to halt and reverse biodiversity decline by as early as 2030. Australia risks being left behind in this global push.

And last week, the G7 nations endorsed a plan to reverse the loss of biodiversity, and to conserve or protect at least 30% of land and oceans, by 2030.

These commitments are crucial – not only for wildlife, but for humans that depend on ecosystems that are now collapsing. When nature loses, we all suffer.

Read more: 'Existential threat to our survival': see the 19 Australian ecosystems already collapsing ![]()

Martine Maron, ARC Future Fellow and Professor of Environmental Management, The University of Queensland; Brendan Wintle, Professor in Conservation Ecology, School of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne, and Craig Moritz, Professor, Research School of Biology, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW State Government's Plans To Open Western NSW To Coal Mining Open For Feedback

- Forty-five recorded Aboriginal heritage sites and an additional 13 sites that are restricted and location data not supplied in the proposed coal release areas.

- Twenty-two threatened fauna species and six threatened flora species including the koala, the critically endangered regent honeyeater and the endangered spotted-tailed quoll, as well as four plant species endemic to the Rylstone/western Wollemi area.

- One thousand, eight hundred and fifty-four hectares of groundwater dependant ecosystems.

- Six thousand, six hundred and thirty-four hectares of potential threatened ecological communities.

- Thirty-six water bores.

- One hundred and twenty kilometres of stream channels in good condition and 118 kilometres of stream channels classed as a high level of fragility.

New Plan To Revitalise NSW's Oldest Park By Installing Mountain Bike Trails

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park, Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Planning Considerations

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Plan of Management

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Mountain Biking Plan

Senators Save Renewable Energy Agency

- Anything that is a ‘low-emission technology’ (with the ‘widest possible meaning’).

- Anything that is a priority in the government’s Technology Investment Roadmap (which includes carbon capture projects and hydrogen produced from coal and gas).

Dumped: Pitt’s Push To Dodge Legal Scrutiny Gets A Radioactive Rebuff

US scheme used by Australian farmers reveals the dangers of trading soil carbon to tackle climate change

Soil carbon is in the spotlight in Australia. A key plank in the Morrison government’s technology-led emissions reduction policy, it involves changing farming techniques so soils store more carbon from the atmosphere.

Farmers can encourage and accelerate this process through methods that increase plant production, such as improving nutrient management or sowing permanent pastures. For each unit of atmospheric carbon they remove in this way, farmers can earn “carbon credits” to be sold in emissions trading markets.

But not all carbon credits are created equal. In one high-profile deal in January, an Australian farm sold soil carbon credits to Microsoft under a scheme based in the United States. We analysed the methodology behind the trade, and found some increases in soil carbon claimed under the scheme were far too optimistic.

It’s just one of several problems raised by the sale of carbon credits offshore. If not addressed, the credibility of carbon trading will be undermined. Ultimately the climate - and the planet - will be the loser.

What Is Soil Carbon Trading?

Plants naturally remove carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the air through photosynthesis. As plants decompose, carbon-laden organic matter is added to the soil. If more organic matter is added than is lost, soil carbon levels increase.

Carbon trading schemes require the increase in soil carbon levels to be measured. The measurement methods are well-established, but can be costly and complex because they involve collecting and analysing large numbers of soil samples. And different carbon credit schemes measure the change in different ways - some more robust than others.

The Australian government’s Emissions Reduction Fund has a rigorous approach to soil sampling, laboratory analysis and calculation of credits. This ensures only genuine removals of atmospheric carbon are rewarded, in the form of “Australian Carbon Credit Units”.

Farmers can choose other schemes under which to earn carbon credits, such as the US-based carbon offset platform Regen Network.

Regen Network’s method for estimating soil carbon largely involves collecting data via satellite imagery. The extent of physical on-the-ground soil sampling is limited.

Regen Network issues “CarbonPlus credits” to farmers deemed to have increased soil carbon stores. Farmers then sell these credits on the Regen Network trading platform.

‘A Number Of Concerns’

It was Regen Network which sold Microsoft the soil carbon credits generated by an Australian farm, Wilmot Station. Wilmot is owned by the Macdoch Group, and other Macdoch properties have also claimed carbon credits under the Regen Scheme.

Regen Network should be applauded for making its methods and calculations available online. And we appreciate Regen’s open, collaborative approach to developing its methods.

However, we have reviewed their documents and have a number of concerns:

the dry weight of soil in a known volume, also known as “bulk density”, is a key factor in calculating soil carbon stocks. Rather than bulk density being measured from field samples, it was calculated using an equation. We examined this method and determined it was far less reliable than field sampling

Estimates of soil carbon were not adjusted for gravel content. Because gravel contains no carbon, carbon stock may have been overestimated

The remote sensing used by Regen Network involved assessment of vegetation cover via satellite imagery, from which soil carbon levels were estimated. However, vegetation cover obscures soil, and research has found predictions of soil carbon using this method are highly uncertain.

Read more: The Morrison government wants to suck CO₂ out of the atmosphere. Here are 7 ways to do it

Wilmot increased soil carbon, or “sequestration”, through changes to grazing and pasture management. The resulting rates of carbon storage calculated by Regen Network were extremely high – 7,660 tonnes of carbon over 1,094 hectares. This amounts to 7 tonnes of carbon per hectare from 2018 to 2019.

These results are not consistent with our experience of what is possible through pasture management. For example, the CSIRO has documented soil carbon increases of 0.1 to 0.3 tonnes of carbon per hectare per year in Australia from a range of methods to increase pasture production.

We believe inaccurate methods have led to the carbon increase being overestimated. Thus, it appears excess carbon credits may have been awarded.

Many carbon trading schemes apply rules to ensure integrity is maintained. These include:

an “additionality test” to ensure the extra carbon storage in the soil would not have happened anyway. It would prevent, for example, farmers claiming credits for practices they adopted in the past

ensuring sequestered carbon is maintained over time

disallowing double-counting of credits – for example, by preventing a country claiming credits that have been sold offshore.

The Emissions Reduction Fund and other well-recognised international schemes, such as Verra and Gold Standard, apply these rules stringently. Regen Network’s safeguards are less rigorous.

Responses to these claims from Regen Network and Macdoch Group can be found at the end of this article. A full response from Regen can also be found here.

Not In The National Interest?

Putting aside the problems noted above, the offshore sale of soil carbon credits generated by Australian farmers raises other concerns.

First, selling credits offshore means Australia loses out, by not being able to claim the abatement towards our own government and industry targets.

Second, soil carbon does not have unlimited emissions reduction potential. The quantum of carbon that can be stored in each hectare of soil is constrained, and limited by factors such as land availability and climate change. So measures to increase soil carbon should not detract from society’s efforts to reduce emissions from fossil fuel use.

And third, ensuring carbon remains in soil long after it’s deposited is a challenge because soil microbes break down organic matter. Carbon credit schemes commonly manage this by requiring a “buffer” of unsold credits. If stored carbon is lost, farmers must relinquish credits from the buffer.

If the loss is greater than the buffer, credits must be purchased to make up the difference. This exposes farmers to financial risk, especially if carbon prices rise.

Read more: We need more carbon in our soil to help Australian farmers through the drought

Getting It Right

Soil carbon is a promising way for Australia to substantially reduce its emissions. But methods used to measure gains in soil carbon must be accurate.

Carbon markets must be regulated to ensure credit is awarded for genuine abatement, and risks to farmers are limited. And the extent to which offshore carbon markets prevent Australia from meeting its own obligations to reduce emissions should be clarified and managed.

Improving the integrity of soil carbon trading will have benefits beyond emissions reduction. It will also improve soil health and farm productivity, helping agriculture become more resilient under climate change.

Regen Network Response

Regen Network provided The Conversation with a response to concerns raised in this article. The full nine-page statement provided by Regen Network is available here.

The following is a brief summary of Regen Network’s statement:

- Limited on-ground soil sampling: Regen Network said its usual minimum number of soil samples was not reached in the case of Wilmot Station, because historical soil samples - taken before the project began - were used. To compensate for this, relevant sample data from a different farm was combined with data from Wilmot.

“We understand the use of ancillary data does not follow best practice and our team is working hard to ensure future projects are run using a sufficient number of samples,” Regen Network said.

- Bulk density: Regen Network said the historical sample data from Wilmot did not include “bulk density” measurements needed to estimate carbon stocks, which required “deviations” from its usual methodology. However the company was taking steps to ensure such estimates in future projects “can be provided with higher degrees of accuracy”.

- Gravel content: Regen Network said lab reports for soil samples included only the weight, not volume, of gravel present. “Best sampling practice should include the gravel volume as an essential parameter for accurate bulk density measurements. We will make sure to address this in our next round of upgrades and appreciate the observation!” the statement said.

- Remote sensing of vegetation: Regen Network said it did not use vegetation assessment at Wilmot station. It tested a vegetation assessment index at another property and found it ineffective at estimating soil carbon. At Wilmot station Regen used so-called individual “spectral bands” to estimate soil carbon at locations where on-ground sampling was not undertaken.

- Sequestration rates at Wilmot: Regen Network said while it was difficult to directly compare local sequestration rates across climatic and geologic zones, the sequestration rates for the projects in question “fall within the relatively wide range of sequestration rates” reported in key scientific studies.

Regen Network said its methodology “provides a conservative estimate on the final number of credits issued”. Its statement outlines the steps taken to ensure soil carbon levels are not overestimated.

- Integrity safeguards: Regen Network said it employs standards “based both on existing standards of reputable programs […] and inputs from project developers, in order to come up with a standard that not only is rigorous but also practical”. Regen Network takes steps to ensure additionality and permanence of carbon stores, as well as avoid double counting of carbon credits generated through their platform.

A more detailed response from Regen Network can be found here.

Wilmot Station Response

Wilmot Station provided the following response from Alasdair Macleod, chairman of Macdoch Group. It has been edited for brevity:

We entered into the deals with Regen Network/Microsoft because we wanted to give a hint of the huge potential that we believe exists for farmers in Australia and globally to sequester soil carbon which can be sold through offset markets or via other methods of value creation.

Whilst we recognise that the soil carbon credits generated on the Macdoch Group properties in the Regen Network/Microsoft deal will not be included in Australia’s national carbon accounts, it is our hope that over time the regulated market will move towards including appropriately rigorous transactions such as these in some form.

At the same time we have also been working closely with the Australian government, industry organisations, academia and other interested parties on Macdoch Group properties to develop appropriate soil carbon methodologies under the government’s Climate Solutions Fund.

This is because carbon measurement methodologies are an evolving science. We have always acknowledged and will welcome improvements that will be made over the coming years to the methodologies utilised by both the voluntary and regulated markets.

In any event it has become clear that there is huge demand from the private sector for offset deals of this nature and we will continue to work towards ensuring that other farmers can take advantage of the opportunities that will become available to those that are farming in a carbon-friendly fashion.![]()

Aaron Simmons, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, University of New England; Annette Cowie, Adjunct Professor, University of New England; Brian Wilson, Associate Professor, University of New England; Mark Farrell, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO; Matthew Tom Harrison, Associate Professor of Sustainable Agriculture, University of Tasmania; Peter Grace, Professor of Global Change, Queensland University of Technology; Richard Eckard, Professor & Director, Primary Industries Climate Challenges Centre, The University of Melbourne; Vanessa Wong, Associate Professor, Monash University, and Warwick Badgery, Research Leader Pastures an Rangelands, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Cocoon

I found this discarded cocoon during one of Tilly's morning strolls around the block this week - showing whatever had been growing within this little made from sticks home has left. After looking around to see what may have lived here it seems this case is made by caterpillars and moths, a family of the Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), with the common name for the Psychidae "case moths". The name refers to the habit of caterpillars of these two families, which build small protective cases in which they can hide. The caterpillar larvae of the Psychidae construct cases out of silk and environmental materials such as sand, soil, lichen, or plant materials. These cases are attached to rocks, trees or fences while resting or during their pupa stage, but are otherwise mobile.

Bagworm cases range in size from less than 1 cm to 15 cm among some tropical species. This one was about 8 cm long. Each species makes a case particular to its species, making the case more useful to identify the species than the creature itself. Cases among the more primitive species are flat. More specialised species exhibit a greater variety of case size, shape, and composition, usually narrowing on both ends. The attachment substance used to affix the bag to host plant, or structure, can be very strong, and in some case require a great deal of force to remove given the relative size and weight of the actual "bag" structure itself.

Since bagworm cases are composed of silk and the materials from their habitat, they are naturally camouflaged from predators. Predators include birds and other insects. Birds often eat the egg-laden bodies of female bagworms after they have died. Since the eggs are very hard-shelled, they can pass through the bird's digestive system unharmed, promoting the spread of the species over wide areas.

A bagworm begins to build its case as soon as it hatches. Once the case is built, only adult males ever leave the case, never to return, when they take flight to find a mate.

Undescribed Iphierga sp., to MV light, Aranda, ACT, 20/21 November 2008. Photo by D Hobern

Bagworms add material to the front of the case as they grow, excreting waste materials through the opening in the back of the case. When satiated with leaves, a bagworm caterpillar secures its case and pupates. The adult female, which is wingless, either emerges from the case long enough for breeding or remains in the case while the male extends his abdomen into the female's case to breed. Females lay their eggs in their case and die. The female evergreen bagworm (Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis) dies without laying eggs, and the larval bagworm offspring emerge from the parent's body. Some bagworm species are parthenogenetic, meaning their eggs develop without male fertilisation. Each bagworm generation lives just long enough as adults to mate and reproduce in their annual cycle.

Bagworm species are found globally, with some, such as the snailcase bagworm (Apterona helicoidella), in modern times settling continents where they are not native.

Pretty amazing - I wonder what we'll find this week?

Bagworm extending its forequarters from its case in the act of locomotion. Photo by Benjamint444

Midwinter Feast

Phoenix Program Seeking Expressions Of Interest At Manly Warringah Kayak Club

Applications are invited for the second year of the MWKC Phoenix Programme on Narrabeen Lake. This Programme is designed to deliver athletes into State and National Pathway Programs.

At this stage the Club has set target dates for athlete testing as Wednesday 28 July and Sunday 01 August, but it may be subject to change (such as weather events) so please contact us to confirm.

If you are interested in applying for the Programme, please send an email to our Head Coach, Brett Worth at brettworth36@hotmail.com and provide the following details;

Athlete Name

Athlete DOB

Brief summary of paddling experience (if any)

Brief summary of other sporting interests / achievements.

If you would like to speak with someone prior to applying you can contact;

Brett Worth, MWKC Head Coach 0466 599 423 Peter Grimes, MWKC President 0418 221 042

Details are available at this link: www.mwkc.org.au

Do You Want To Be A Radio Broadcaster?

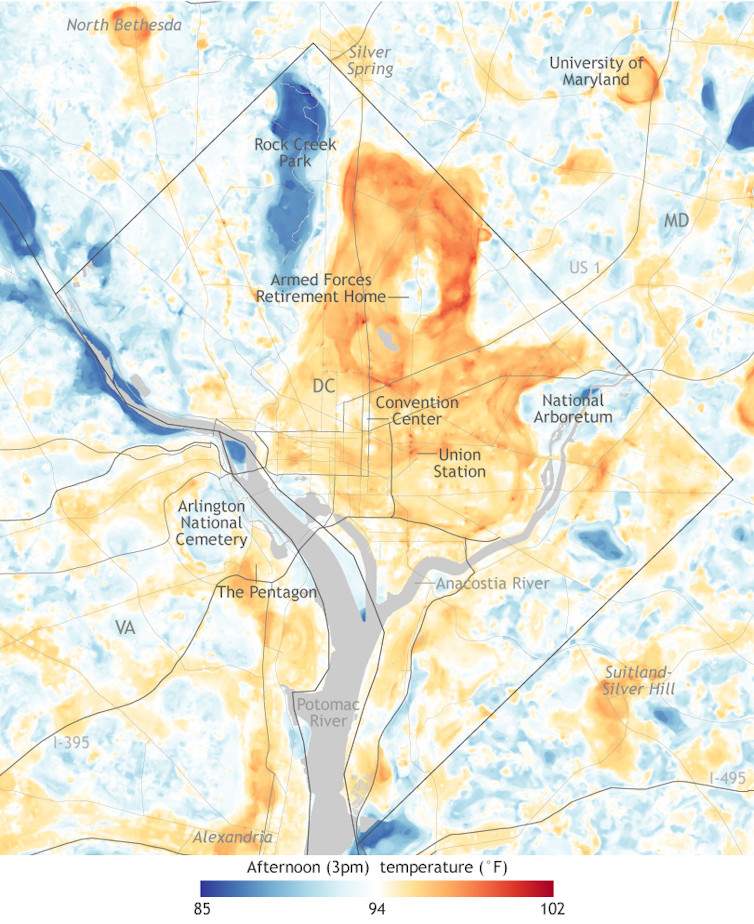

Lighter pavement really does cool cities when it’s done right

When heat waves hit, people start looking for anything that might lower the temperature. One solution is right beneath our feet: pavement.

Think about how hot the soles of your shoes can get when you’re walking on dark pavement or asphalt. A hot street isn’t just hot to touch – it also raises the surrounding air temperature.

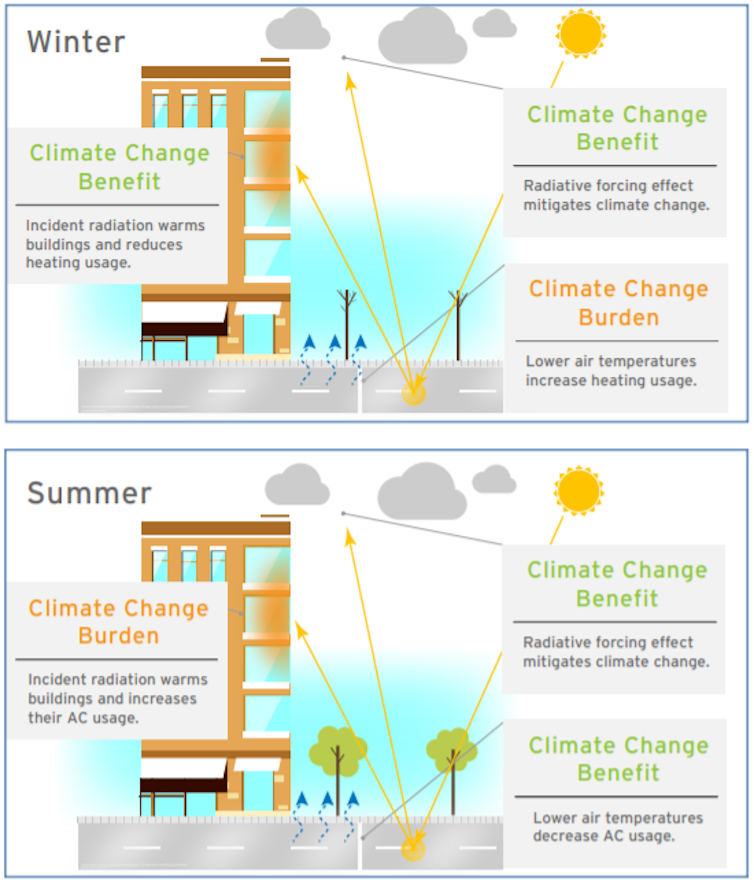

Research shows that building lighter-colored, more reflective roads has the potential to lower air temperatures by more than 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit (1.4 C) and, in the process, reduce the frequency of heat waves by 41% across U.S. cities. But reflective surfaces have to be used strategically – the wrong placement can actually heat up nearby buildings instead of cooling things down.

As researchers in MIT’s Concrete Sustainability Hub, we have been modeling these surfaces and determining the right balance for lowering the heat and helping cities reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Here’s how reflective pavement works and what cities need to think about.

Why Surfaces Heat Up

All surfaces, depending on the amount of radiation they absorb or reflect, can affect air temperatures in cities.

In urban areas, about 40% of the land is paved, and that pavement absorbs solar radiation. The absorbed heat in the pavement mass is released gradually, warming the surrounding environment. This can exacerbate urban heat islands and worsen the effects of heat waves. It’s part of the reason cities are regularly a few degrees warmer in summer than nearby rural areas and leafy suburbs.

Reflective materials on pavement can prevent that heat from building up and help counteract climate change by reflecting solar radiation back to the top of the atmosphere. White roofs can have the same effect.

To estimate a pavement’s reflectivity, we use a measure called albedo. Albedo refers to the proportion of light reflected by a surface. The lower a surface’s albedo, the more light it absorbs and, consequentially, the more heat it traps.

Typically, the darker the surface, the lower the albedo. Conventional pavements such as asphalt have a low albedo of around 0.05-0.1, meaning they reflect only 5% to 10% of the light they receive and absorb as much as 95%.

When pavements instead use brighter additives, reflective aggregates, light-reflective surface coatings or lighter paving materials like concrete, they can triple the albedo, sending more radiation back into space.

Though the benefits of reflective pavements can vary across the nation’s 4 million miles of roads, they are, on the whole, immense. An MIT CSHub model estimated that an increase in pavement albedo on all U.S. roads could lower energy use for cooling and reduce greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 4 million cars driven for one year. And when materials are locally sourced, such as light-colored binders or aggregates, the crushed stone, gravel or other hard materials in concrete, these roads can also save money.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]

Location Matters

But not all paved areas are ideal for cool roads. Within cities, and even within urban neighborhoods, the benefits differ.

When brighter pavements reflect radiation onto buildings – called incident radiation – they can warm nearby buildings in the summer, actually increasing the demand for air conditioning. That’s why attention to location matters.

Consider the differences between Boston and Phoenix.

Boston’s dense downtown of narrow streets has tall buildings that block light from directly hitting the pavement most hours of the day. Reflective pavement won’t help or harm much there. But Boston’s unobstructed freeways and its suburbs would see a net benefit from reflecting a large fraction of incoming sunlight to the top of the atmosphere. Using models, we found that doubling the traditional albedo of the city’s roads could cut peak summer temperatures by 1 to 2.7 F (0.3 to 1.7 C).

Phoenix could reduce its summer temperatures even more – by 2.5 to 3.6 F (1.4 to 2.1 C) – but the effects in some parts of its downtown are complicated. In a few low, sparse downtown neighborhoods, we found that reflective pavement could raise the demand for cooling because of increased incident radiation on the buildings.

In Los Angeles, where the city has been experimenting with a cooler coating over asphalt, researchers found another effect to consider. When the coating was used in areas where people walk, the ground itself was as much as 11 F (6.1 C) cooler, but a few feet off the ground, the temperature rose as the sun’s rays were reflected. The results suggest such coatings might be better for roads than for sidewalks or playgrounds.

An Elegant Solution, If Used With Care

Cities will need to consider all of these effects.

Reflective pavements are an elegant solution that can transform something we use every day to reduce urban warming. The full lifecycle emissions of roads, including the materials used in them, have to be factored in. But as cities consider ways to combat the effects of climate change, we believe strategically optimizing pavement is a smart option that can make urban cores more livable.![]()

Hessam AzariJafari, Postdoctoral Associate in Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Randolph E. Kirchain, Co-Director, MIT Concrete Sustainability Hub, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How Eleanor Roosevelt reshaped the role of First Lady and became a feminist icon

Zora Simic, UNSWThis piece is part of a new series in collaboration with the ABC’s Saturday Extra program. Each week, the show will have a “who am I” quiz for listeners about influential figures who helped shape the 20th century, and we will publish profiles for each one. You can read the first piece in the series here.

“Well-behaved women seldom make history” is a phrase frequently trotted out around International Women’s Day, and just as frequently attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt. It doesn’t matter that the former First Lady of the United States never actually said this – in fact, it was Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich in an obscure academic article in the 1970s – the misattributed quote endures, further cementing Roosevelt’s reputation as one of the most inspiring women of all time.

2021 has also seen the unveiling of the Eleanor Roosevelt Barbie Doll, another marker of her iconic status. In this she has joined the “Inspirational Women” series — following, among others, Maya Angelou, Florence Nightingale, Frida Kahlo and her friend, aviator Amelia Earhart. (Whether she would have approved is another matter.)

Despite her 1.8-metre fame, or perhaps because of it, ER – as she was colloquially known – was not one to draw extra attention to herself. However, she came to excel at using her platform to uplift others or promote her favourite causes, including women’s rights and racial equality.

Read more: Why politics today can't give us the heroes we need

Two days after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s inauguration as the 32nd president of the US in March 1933, the new First Lady held her first White House press conference for women reporters only. This was the first of 378 such events, offering unprecedented access for women journalists over the 12 years, or three terms, FDR was in power.

In another historic first, Eleanor Roosevelt twice invited African American contralto opera singer Marian Anderson to perform at the White House – including for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth during their US tour in 1939. In the same year, behind the scenes, she lobbied for Anderson to perform an open-air concert in front of the Lincoln Memorial in the then racially segregated capital – a performance since described as a “watershed moment in civil rights history”.

Against the backdrop of the Great Depression, the Democrats’ “New Deal” and the second world war, ER transformed the First Lady role from largely ceremonial to much more publicly and politically engaged one.

As well as opening the White House to new constituencies, she extended her duties far beyond the official residence. With the president’s mobility compromised by his paralysis, ER was frequently dispatched to gather evidence, inspect government works and assess public opinion within the US and sometimes internationally. Her extensive travel made her an easy target for media satire – “Mrs Roosevelt Spends Night at White House” ran one headline – and earned her the nickname “Eleanor Everywhere” (now the name of one of several children’s books about her).

Her most famous overseas trip was the five-week South Pacific tour of 1943. Travelling as an ambassador for the American Red Cross, she was flown 25,000 miles on a four-engine military plane, the Liberator, from San Francisco to Hawaii, on to the Pacific Islands, New Zealand and Australia, and back again.

In Australia, thousands lined the streets of Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane to greet her. In Canberra, she became the first woman ever to be an official guest at a luncheon at Parliament House. Prime Minister John Curtin toasted her by saying “you are one of the most distinguished figures of our age”.

The First Lady dutifully reported interesting observations about Australia in her widely syndicated My Day column. Privately, however, she found the official engagements exhausting and trivial compared with her core mission of visiting US service personnel. In her 1949 memoir This I Remember, it was the impact of meeting American GIs in military hospitals that lingered with her. She wrote:

The Pacific trip left a mark from which I think I shall never be free.

Roosevelt’s My Day column ran six days a week from 1935 to mere weeks before her death in 1962. In that time, she only ever missed four days - when her husband collapsed and died, just months into his historic fourth term in office in April 1945.

Not long after, the next phase of her life began when FDR’s successor Harry Truman appointed her US delegate to the United Nations, declaring her “First Lady of the World”. As Chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights (1946-51), she was a driving force in the drafting and adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 – although not the only one.

As First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt was admired, but controversial. Now, she frequently tops US polls as the most popular First Lady in history. Fascination with her life and character has only increased, indexed by a steady stream of books focused on her private life — her marriage to womaniser FDR, her passionate friendships with women and men, who may or may not have been lovers – as well her public achievements.

Amy Bloom’s 2018 novel White Houses, fictionalising Eleanor’s relationship with journalist Lorena “Hick” Hickock, was a bestseller, as is the most recent biography by David Michaelis, Eleanor, released late last year.

Read more: Remembering Pearl Harbor and America's entry into the theatre of war

In 1968, Eleanor Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the UN Human Rights Prize and in 1998, the United Nations Association of the USA inaugurated the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award.

For Hillary Clinton, the former First Lady most often compared to Roosevelt, Eleanor was so inspirational she is rumoured to have held imaginary conversations with her at crossroads in her political career.

Finally, inspirational quotes that Eleanor Roosevelt actually said or wrote continue to circulate. To end with one that captures how she herself redefined the possibilities of leadership:

A good leader inspires people to have confidence in the leader. A great leader inspires people to have confidence in themselves.

Zora Simic, Senior Lecturer, School of Humanities, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

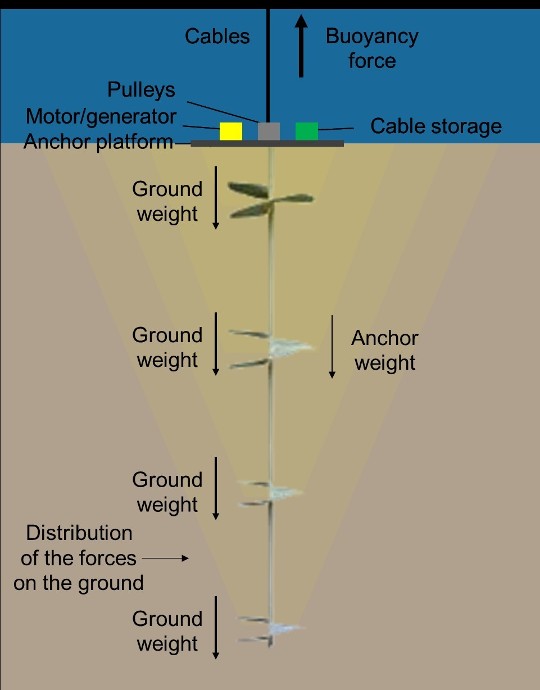

How shipping ports are being reinvented for the green energy transition

When it comes to launching the energy transition, maritime policy is one of the key battlegrounds. But many ports, aware of their ecological and economic vulnerability, have committed to sustainable development strategies.

According to the latest research, sea levels will rise considerably (from 1.1 to 2 metres, on average) by 2100, putting about 14 per cent of the world’s major maritime ports at risk of coastal flooding and erosion. Ports in France, including 66 that are used for maritime trade, are also under threat, and will have to adapt their infrastructure.

Maritime transport accounts for about 80 per cent of global merchandise trade by volume. Shipping is responsible for three per cent of global CO2 emissions, which have increased 32 per cent over the past 20 years. If nothing is done, shipping emissions could climb to 17 per cent of global emissions by 2050.

Enter the “ports of the future.” Ports govern globalized economic activity and are true “energy hubs,” bringing together all kinds of transport (maritime, land-based, waterway and aeronautic). Now, they’re aiming to cut back on real estate, be more respectful of the environment and better integrated into cities, particularly through the concept of “urban ports.”

Freedom From Oil

At least US$1 trillion will have to be invested between 2030 and 2050 to reduce shipping’s carbon footprint by 50 per cent by 2050. As of last year, oil-derived fuels accounted for 95 per cent energy consumption in transportation. Meanwhile, maritime traffic is predicted to increase by 35 to 40 per cent over the same period.

This dependence on hydrocarbons also represents an economic vulnerability for the maritime shipping sector due to new environmental standards.

In France, liquid bulk transport has been in decline since 2009 (decreasing three per cent on average since 2016), despite a slight uptick in 2017 (2.1 per cent). Fuel shipping (50 per cent of shipping by weight in major maritime ports) has also decreased by 25 per cent since 2008.

The golden age of oil cannot will not hold for much longer, given its environmental impact and increasing scarcity. As the consumption of hydrocarbons and coal drops, we should also see a steady decrease in fuel shipping.

The French government’s National Low-Carbon Strategy (“Stratégie nationale bas carbone,” or SNBC) aims to reduce emissions from the industrial sector by 35 per cent by 2030 and 81 per cent by 2050. This will mean a nearly complete decarbonization of maritime transport, creating a real technological challenge for the sector.

This story is part of Oceans 21

Our series on the global ocean opened with five in-depth profiles. Look out for new articles on the state of our oceans in the lead up to the UN’s next climate conference, COP26. The series is brought to you by The Conversation’s international network.

To meet these targets, ports are working to become carbon-neutral by redesigning their logistical operations (flow management) and means of production (value creation), as part of an industrial reconversion approach. They’re banking on new environmental technologies to generate a double dividend, both environmental and economic.

Three approaches could be used to achieve these goals: energy efficiency, renewable energy production and industrial ecology.

Building The Ships Of Tomorrow

A 2021 study by the Getting to Zero coalition found that zero-carbon fuels had to represent at least five per cent of the fuel mix by 2030 for international shipping to comply with the Paris Agreement. Around 100,000 commercial vessels will be affected by this energy transition, according to GTT, a company specializing in the transportation and storage of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

In this vein, an ambitious environmental certification program, Green Marine Europe, launched in 2020 in order to create the European maritime industry of tomorrow.

Read more: How shipping ports can become more sustainable

New fuels with smaller carbon footprints, such as liquefied natural gas, ammonia and ethanol, and the accelerated adoption of alternative propulsion systems will be needed for the sector to become greener.

Hydrogen fuel (initially “grey,” now increasingly “green”) represents another viable alternative in the medium-term for fleets subjected to heavy rotation. Although the project is currently in its early stages (involving small vessels of 60-80 seats), more ambitious initiatives have been launched, such as the Hydrotug boat in construction for the port of Antwerp.

The arrival of steam-powered engines put an end to the use of large wind-propelled clippers in the late 1800s. But technologies that harness the wind could make a major comeback, with ships using sails and kites to reduce fuel use.

Offshore Wind Turbines, A Promising Solution

Developing electric facilities and technology is also essential to the energy transition, whether through electrified wharfs, turning port seawalls into energy producers, or developing electric ferries that use solar power, bioenergy or marine power.

As the energy transition progresses, we will see ports go from consuming large quantities of a single energy source to using multiple energy sources and becoming electricity producers.

On that note, offshore wind turbines will profoundly change French coasts over the coming years. The first sites will be near ports (with the first French offshore 80-turbine wind farm due to launch in Saint-Nazaire in 2022). In the medium term, the objective is to reach a capacity of 5.2 to 6.5 Gigawatts of offshore wind energy in France by 2028.

This technology brings a new vibrancy to port areas in search of industrial diversification, optimized real estate revenue and local expertise (construction and maintenance operations).

The forthcoming offshore wind farm near Quai Hermann du Pasquier in the city of Le Havre, which will launch in 2022, is being presented as the “biggest industrial renewable energy project in France,” and symbolizes the port’s industrial and energetic transition. What’s more, after 53 years of service, the thermal power station in this area, which used 220 tonnes of coal daily, closed down on 31 March 2021.

Finally, it should be noted that offshore wind farms represent an opportunity for ports to produce their own hydrogen by electrolysing seawater.

Bringing City And Port Closer Together

The energy transition forces governments to reconsider the connections between city and port. Development projects based on an entirely oil-based economy and the globalized boom in shipping container transport in the second half of the 20th century disconnected city and port at every level. Ports were removed from urban settings due to a lack of space, with huge industrial port zones created on the city’s outskirts.

Now this separation is being questioned, marking the return of the port as a space that’s open to the rest of the city.

For port cities, where ships coexist with residents, industry, businesses and tourism, pollution has motivated citizens into action. Local environmentalism has pushed ports to become open to cities, by promoting the development of circular economies and industrial ecology.

Many ports have launched energy transition projects, aiming to transform city-port relations. The port area is turning out to be an excellent setting to try out new practices founded on greater co-operation between local players.

In La Rochelle, for example, environmental and energy-based issues provided an opportunity to start a shared, collaborative discussion about the future of the metropolitan area. The La Rochelle Zero Carbon Territory project, where the greater urban area aims to become carbon neutral by 2040, the energy transition is being undertaken through concerted planning between the city and its port. The port has committed to initiatives that limit its environmental and energy-related impact, while providing benefits to the local economy.

In Le Havre, as in Bordeaux and elsewhere, this city-port interconnection is being strengthened by combining energy-related challenges and digital opportunities.

In time, this should lead to the birth of “smart port cities” (connecting “smart cities” with the “ports of the future”), for a “new model for urban and industrial port areas, blended together by innovation.”

Making Ports The Site Of Modern Energy

Although the environmental challenge is clearly huge and complicated, this energy transition gives us the opportunity to reinterpret ports as laboratories, and to test new practices and technologies. Case in point: the Port of Rotterdam decreased its CO2 emissions by 27 per cent between 2016 and 2020.

Ports have always been showcases of industrial revolution, with the arrival of steam, propellers and then metal hulls. They often feature the most recent energy-related technology, as shown by the painting of the port of Le Havre, by Camille Pissarro.

Now it’s up to them to keep this legacy alive, as true gateways to a more durable and resilient economy.

Translated from French by Rosie Marsland for Fast ForWord.![]()

Sylvain Roche, Enseignement-chercheur associé, transition énergétique et territoriale, Sciences Po Bordeaux

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Smart street furniture in Australia: a public service or surveillance and advertising tool?

Smart street furniture – powered and digitally networked furniture that collects and generates data – is arriving in Australia. It comes in a variety of forms, including benches, kiosks, light poles and bus stops. Early examples in Australia include ChillOUT Hubs installed by Georges River Council in the Sydney suburbs of Kogarah, Hurstville and Mortdale, and information kiosks and smart light poles in the City of Newcastle as part of its Smart City Strategy.

The “smartness” of this street furniture comes from its new data and connectivity capabilities. The idea is that these can generate new products and services, and support real-time planning decisions in cities. Most offer free wi-fi in combination with other functions like advertising, wayfinding, emergency buttons, phone calling and device charging via USB.

Read more: Sensors in public spaces can help create cities that are both smart and sociable

Smart, But Controversial

The promise of smart street furniture is that it will enhance public spaces and revitalise ageing infrastructure. By providing vulnerable and disadvantaged citizens with access to free connectivity services it can also bridge digital barriers.

Despite these benefits, some aspects of smart street furniture are controversial. In particular, its data collection and impact on public space have created concerns.

In New York City, the replacement of phone booths by LinkNYC digital kiosks has given rise to protest about data ownership and sharing and surveillance through built-in security cameras. Other sources of tension are the kiosks’ physical footprint, visual impact and use for outdoor advertising with its double-sided 140cm digital displays.

In Australia, Telstra has been fighting a long court case against the cities of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane over plans to convert its phone booths into smart hubs equipped with digital advertising. Councils objected to these on the basis that they required local planning approval. Telstra argued the hubs were exempt as “low-impact facilities”, but has had to delay installation.

What Can We Learn From Early Adopters Overseas?

We don’t yet understand the public impact and value of smart street furniture, what service model is to be adopted at scale, or what kind of future it offers. To what extent are these facilities offering public services, or are they just enablers of more advertising and surveillance?

Australia can learn from the early examples of smart street furniture in other countries. Our Smart Publics research project investigated the design, use and governance of InLinkUK kiosks in Glasgow and Strawberry Energy smart benches in London with a research team at the University of Glasgow. (The final report is here.)

We found the main users were those who were living rough, young people, students and gig workers. Smart furniture enabled these groups to stay digitally connected. They used these facilities to charge their phones and make free calls, which were especially valuable for those who didn’t own phones or lacked the credit to use them. (The InLinkUK kiosks offered free calls to any mobile or landline in the UK.)

Read more: How do we stop people falling through the gaps in a digitally connected city?

Who Is Funding These Facilities?

Even though kiosks and smart benches could be used for community service information, we found it was commercial advertising that drove private investment in this infrastructure. Advertising revenue paid for the services offered by the InLinkUK kiosks and sponsorship for the Strawberry Energy benches. Advertising agency Primesight was one of the three main partners in InLinkUK (with British Telecom and Intersection, the company responsible for LinkNYC).

Because advertising was so prominent in their design, many people were unaware of their other functions. Asked if they’d noticed the InLinks, one person replied:

“Er no, I haven’t […] what’s it for? Is it to make free calls to anywhere in the UK? […] I just thought it was like an advertising board, I guess!”

People recognised the wide public value of free wi-fi, device charging and phone calls. But we found the public as a whole didn’t understand the data-collection aspects. The marginalised groups who relied on these services were more exposed to corporate advertising, data collection and surveillance in public spaces.

Read more: People-friendly furniture in public places matters more than ever in today's city

Councils were also limited in their ability to leverage the benefits that came from the data. The Strawberry Energy benches, for example, collected environmental data such as temperature, noise level and air quality from inbuilt sensors. However, these data weren’t being used to inform planning or policy.

Reliability of the data was another issue. We found inaccuracies when we tested the environmental data.

Where To Now In Australia?

These issues highlight some of the challenges councils encounter when embarking on smart street furniture initiatives with private companies. These include data-sharing contract arrangements as well as the need to upskill council staff to manage new kinds of data capabilities and systems.

The examples we studied in the UK had been rolled out in public-private partnerships. However, some of the models emerging suggest a different kind of civic implementation.

Local governments that have been early adopters of smart furniture in Australia have envisioned it as an extension of council services without added advertising or compromising heritage values. These have typically begun as experimental initiatives funded by federal and state government grants. The City of Newcastle, for example, is planning to integrate smart city technologies into regular council operations.

Smart street furniture is not going away. If anything, it will become pervasive as technology advances and becomes more integrated into our physical surroundings.

The issues raised by smart street furniture warrant close inspection and further research. It is crucial that governments and private actors are transparent about its use for advertising and data collection. To ensure the benefits of smart street furniture are realised, they need to:![]()

- emphasise the public value of smart street furniture, including its use for community-based information

- collaborate with the public on its design and placement

- in the case of councils, take a pro-active approach to access, ownership and stewardship of data

- ensure marginalised citizens are not exposed to increased risk of surveillance and data harms.

Justine Humphry, Senior Lecturer in Digital Cultures, University of Sydney; Chris Chesher, Senior Lecturer in Digital Cultures, University of Sydney, and Sophia Maalsen, ARC DECRA Fellow and Lecturer in Urbanism, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Senate has voted to reject critical race theory from the national curriculum. What is it, and why does it matter?

Leticia Anderson, Southern Cross University and Kathomi Gatwiri, Southern Cross UniversityThe Australian Senate yesterday voted in support of a motion calling on the federal government to reject critical race theory from the national curriculum.

The motion was moved by Senator Pauline Hanson. Critical race theory, or CRT, is an academic theory developed primarily by Black scholars and activists to highlight the systemic and institutional nature of racism.

The motion comes after concerns reported in some media, such as The Australian, that the proposed draft national curriculum’s is “preoccupied with the oppression, discrimination and struggles of Indigenous Australians”.

A draft of the proposed revised national curriculum was released at the end of April. New revisions include a more accurate reflection of the historical record of First Nations people’s experience with colonisation, with a commitment to “truth telling”. This means in part recognising that Australia’s First Nations peoples experienced the British arrival as an “invasion”. (It also classifies as an invasion according to international law at the time.)

After the release of the draft curriculum, a conservative think tank claimed there were signs critical race theory was creeping into schools.

Critical race theory is an academic framework that is not part of the Australian curriculum. Learning how, for example, First Nations Australians experienced colonisation is expanding knowledge and understanding about our history. It is not necessarily a direct influence of critical race theory.

Every time race is mentioned in an educational context, it does not mean CRT is being applied.

It’s important the historical and ongoing legacies of colonialism and racial disparities are discussed in the Australian curriculum. Seeking to restrict this discussion by misrepresenting critical race theory is a move copied from conservative United States playbooks.

What Is Critical Race Theory?

Critical race theory is a collection of theoretical frameworks, which provide lenses through which to examine structural and institutional racism.

Within critical race theory, racism is viewed as more than just individual prejudices. Instead, it is considered to include a wide range of social practices deeply embedded in policies, laws and institutions.

Critical race theory was developed from the 1960s and 1970s by legal scholars applying sociological critical theory in their work, although the term “CRT” did not emerge until the late 1980s.

Critical race theorists including Kimberlé Crenshaw, Derrick Bell and Patricia Williams investigated how and why racial disparities persisted in the United States. They did so through analysing these disparities in the legal and criminal justice system, as well as how education and employment opportunities (or lack theoreof) impacted generational wealth accumulation.

Interpretations of critical race theory are diverse as it is a growing body of scholarship. These are not formulated by theorists into specific doctrines, manifestos or sets of practices. But some general principles underpin CRT.

They include:

race is understood as a “social construct” rather than a biological reality. That is, supposed “racial” differences between groups of humans are founded in our social experience rather than our genetics (this is well supported by scientific evidence)

“systemic racism” means social institutions and practices unwittingly contribute to and maintain white supremacy. “Invisible” everyday practices perpetuate racial inequality and inequity in health, education and the law

everyone has multiple, overlapping aspects of their identity which may impact their life experiences. These include race, gender, age, class, sexual orientation, disability and nationality. This suggests many people understand or interpret their life experiences through this “intersectional” lens

critical race theory encourages reflection on normalised ways of doing things, especially to question who benefits from systemic privilege and why.