Inbox and environment news: Issue 501

July 11 - 17, 2021: Issue 501

More Time To Have Your Say On Ingleside Housing Development Proposal

Sydney Man Sentenced For Waste Offences On The Hawkesbury River

EPA Fines Power Station Operator $15,000 For Alleged Water Pollution

150 Hectares Of Habitat Lost Each Day In NSW

Community Workshop Sheds Light On Microplastics In Hawkesbury-Nepean River

Western Sydney University researchers and students, in collaboration with Streamwatch and Greater Sydney Landcare, have joined community volunteers as part of a hands-on workshop to assess the number of microplastics present in the Hawkesbury-Nepean River.

Western Sydney University researchers and students, in collaboration with Streamwatch and Greater Sydney Landcare, have joined community volunteers as part of a hands-on workshop to assess the number of microplastics present in the Hawkesbury-Nepean River. Catherine Welsh was one of the students on hand to support the day. Catherine is studying the Master of Philosophy at Western Sydney University's Hawkesbury campus and aspires to work in conservation.

Catherine Welsh was one of the students on hand to support the day. Catherine is studying the Master of Philosophy at Western Sydney University's Hawkesbury campus and aspires to work in conservation.Draft National Recovery Plan For The Koala (Combined Populations Of Queensland, New South Wales And The Australian Capital Territory)

Federal Consultation On Endangered Listing For The Koala Now Open - Closes July 30, 2021

Koala Listing Strengthens Call For An Independent Environmental Compliance Agency

Gas-Fired Recovery Measures: Have Your Say - Closes August 2nd

- unlock supply

- deliver an efficient pipeline and transportation network

- empower gas customers.

- the National Gas Infrastructure Plan (NGIP)

- the Future Gas Infrastructure Investment Framework.

Australia’s threatened species plan has failed on several counts. Without change, more extinctions are assured

Euan Ritchie, Deakin University and Ayesha Tulloch, University of SydneyAustralia is globally renowned for its abysmal conservation record – in roughly 230 years we’ve overseen the extinction of more mammal species than any other nation. The federal government’s Threatened Species Strategy was meant to address this confronting situation.

The final report on the five-year strategy has just been published. In it, Threatened Species Commissioner Dr Sally Box acknowledges while the plan had some important wins, it fell short in several areas, writing:

…there is much more work to do to ensure our native plants and animals thrive into the future, and this will require an ongoing collective effort.

Clearly, Australia must urgently chart a course towards better environmental and biodiversity outcomes. That means reflecting honestly on our successes and failures so far.

How Did The Strategy Perform?

The strategy, announced in 2015, set 13 targets linked to three focus areas:

- feral cat management

- improving the population trajectories of 20 mammal, 21 bird and 30 plant species

- improving practices to recover threatened species populations.

Given the scale of the problem, five years was never enough time to turn things around. Indeed, as the chart below shows, the report card indicates five “red lights” (targets not met) and three “orange lights” (targets only partially met). It gave just five “green lights” for targets met.

Falling Short On Feral Cats

Feral cats were arguably the most prominent focus of the strategy, despite other threats requiring as much or more attention, such as habitat destruction via land clearing.

However, the strategy did help start a national conversation about the damage cats wreak on wildlife and ecosystems, and how this can be better managed.

In the five years to the end of 2020, an estimated 1.5 million feral cats were killed under the strategy – 500,000 short of the 2 million goal. But this estimate is uncertain due to a lack of systematic data collection. In particular, the number of cats culled by farmers, amateur hunters and shooters is under-reported. And more broadly, information is scattered across local councils, non-government conservation agencies and other sources.

Read more: One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

Australia’s feral cat population fluctuates according to rainfall, which determines the availability of prey – numbering between 2.1 million and 6.3 million. Limited investment in monitoring makes it impossible to know whether the average of 300,000 cats killed each year over the past five years will be enough for native wildlife to recover.

The government also failed in its goal to eradicate cats from five islands, only achieving this on Dirk Hartog Island off Western Australia. Importantly, that effort began in 2014, before the strategy was launched. And it was primarily funded by the WA government and an industry offset scheme, so the federal government can’t really claim this success.

On a positive note, ten mainland areas excluding feral cats have been established or are nearly complete. Such areas are a vital lifeline for some wildlife species and can enable native species reintroductions in the future.

Priority Species: How Did We Do?

The strategy met its target of ensuring recovery actions were underway for at least 50 threatened plant species and 60 ecological communities. It also made good headway into storing all Australia’s 1,400 threatened plant species in seed banks. This is good news.

The bad news is that, even with recovery actions, the population trajectories of most priority species failed to improve. For the 24 out of about 70 priority species where population numbers were deemed to have “improved” over five years, about 30% simply got worse at a slower rate than in the decade prior. This can hardly be deemed a success.

What’s more, the populations of at least eight priority species, including the eastern barred bandicoot, eastern bettong, Gilbert’s potoroo, mala, woylie, numbat and helmeted honeyeater, were increasing before the strategy began – and five of these deteriorated under the strategy.

The finding that more priority species recovery efforts failed than succeeded means either:

- the wrong actions were implemented

- the right actions were implemented but insufficient effort and funding were dedicated to recovery

- the trajectories of the species selected for action simply couldn’t be improved in a 5-year window.

All these problems are alarming but can be rectified. For example, the government’s new Threatened Species Strategy, released in May, contains a more evidence-based process for determining priority species.

For some species, it’s unclear whether success can be attributed to the strategy. Some species with improved trajectories, such as the helmeted honeyeater, would likely have improved regardless, thanks to many years of community and other organisation’s conservation efforts before the strategy began.

Read more: Australia-first research reveals staggering loss of threatened plants over 20 years

What Must Change

According to the report, habitat loss is a key threat to more than half the 71 priority species in the strategy. But the strategy does not directly address habitat loss or climate change, saying other government policies are addressing those threats.

We believe habitat loss and climate change must be addressed immediately.

Of the priority bird species threatened by land clearing and fragmentation, the trajectory of most – including the swift parrot and malleefowl – did not improve under the five years of the strategy. For several, such as the Australasian bittern and regent honeyeater, the trajectory worsened.

Preventing and reversing habitat loss will take years of dedicated restoration, stronger legislation and enforcement. It also requires community engagement, because much threatened species habitat is on private properties.

Effective conservation also requires raising public awareness of the dire predicament of Australia’s 1,900-plus threatened species and ecological communities. But successive governments have sought to sugarcoat our failings over many decades.

Bushfires and other extreme events hampered the strategy’s recovery efforts. But climate change means such events are likely to worsen. The risks of failure should form part of conservation planning – and of course, Australia requires an effective plan for emissions reduction.

The strategy helped increase awareness of the plight our unique species face. Dedicated community groups had already spent years volunteering to monitor and recover populations, and the strategy helped fund some of these actions.

However, proper investment in conservation – such as actions to reduce threats, and establish and maintain protected areas – is urgently needed. The strategy is merely one step on the long and challenging road to conserving Australia’s precious species and ecosystems.

Read more: 'Existential threat to our survival': see the 19 Australian ecosystems already collapsing ![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University and Ayesha Tulloch, DECRA Research Fellow, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NAIF Money For Central Queensland Coal Project

When Will Politicians Heed Farmers' Concerns About Climate Change?

Public Money For Olive Downs Coal Mine Is Deeply Irresponsible

Keith Pitt's Fracked Gas Cash Splash With Public Money

New NAIF Board To Steer The Next Phase Of Northern Investment

Santos Decision Shows What’s In Store For Farmers If Barilaro Refuses To Slay Zombies

- Removing a condition limiting indirect impacts to 181 hectares. Santos said indirect impacts, such as increased dust, weeds, and feral animal intrusion, “would be extensive across the project area”, but had already been addressed by offsets.

- Removal of specific reference to clearing limits and offset credit requirements for each protected matter.

- Revised groundwater conditions.

- Revised reporting requirements and definitions for the framework to categorise drilling fluid chemicals.

Be suspicious of claims the mining industry creates non-mining jobs

Emblematic of the sort of claims that put the “con” into economics was an assertion by the Queensland Resources Council last year that “the resources sector employs 372,000 Queenslanders”.

The number employed in mining was 66,000, but the council claimed to have used input-output tables in the Australian National Accounts to add to that a much larger of “indirect” jobs created by mining.

It led to the awkward conclusion that mining contributed almost 46,000 full-time jobs to the electorate of McConnel, which had 40,000 enrolled voters.

The credulous way some of the media report such claims partly explains why the public has an inflated idea of the importance of the mining sector.

Surveyed Australians think coal mining makes up 9.4% of the workforce. The true figure at the time was 0.4% — or around 48,200 workers nationally as of May 2020.

The claims derive from a lesser known part of the Australian National Accounts, the ones that tell us each quarter whether or the economy has grown or whether we are in recession.

It comes out once a year, almost two full years after the calender year to which it refers.

How Much Value Is Baked In?

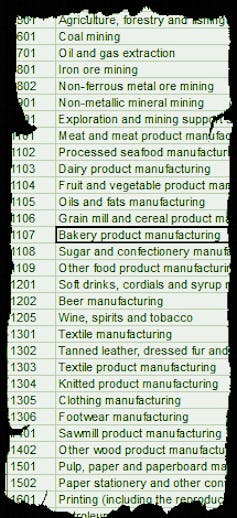

Known as the input-output tables, it’s a honeypot for consultants because it paints an incredibly detailed picture of the ways in which each part of the economy interacts with each other.

As an example, the most recent (which came out last month) tells us the value of bakery products manufactured was A$8.2 billion.

To make these baked goods, the industry used $900 million of grains and cereals, $700 million of meat (fillings for pies), and $500 million of sugar and confectionery (icing for cakes).

It paid $200 million to transport the goods, $100 million to clean the factories and so on.

This added up to $5.2 billion in payments to other industries.

The difference between the $8.2 billion and the $5.2 billion represents the “value added” by baking manufacturers.

Employees in the industry were paid $2.6 billion and there were $200 million in profits for the investors.

Australia also imported another $1.9 billion of bakery products.

The Input-Output Tables Reveal A Lot

The tables also show what happened to all these bakery products. $1 billion went to restaurants and $1.5 billion to other industries. $6.8 billion were bought by households, $800 million were exported.

Importantly, the input-output tables enable comparisons. The industries providing the most full-time equivalent jobs are retailing, professional services and health. The industries making the largest profits are finance and iron ore and oil and gas extraction.

In mining, the profits paid out are ten times what’s paid out in wages. In most manufacturing and service industries more is paid out in wages than profits.

What the tables cannot do is tell us how many jobs an industry has “created” outside of the industry itself.

Listen To The Statistician

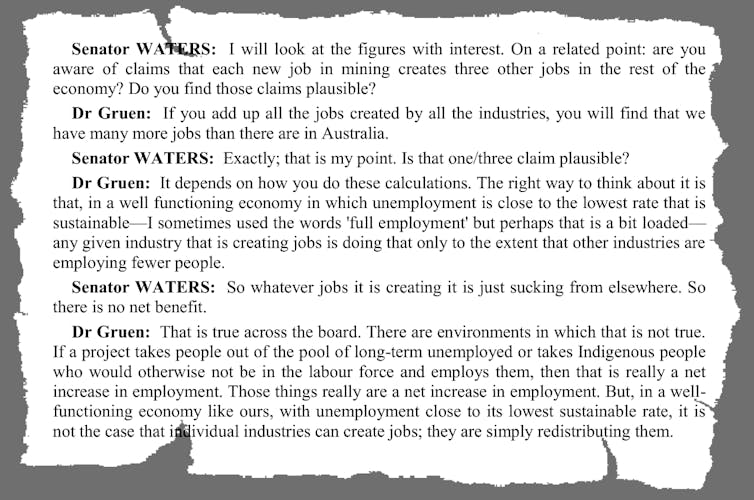

A few years back, a senior treasury official called out this practice, as the following extract from a Senate committee hearing shows:

If you add up all the jobs “created” by all the industries, you will find that we have many more jobs than there are in Australia […] In a well functioning economy any given industry that is creating jobs is doing that only to the extent that other industries are employing fewer people.

That official was David Gruen.

David Gruen is now head of the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Not only does the bureau no longer publish “multipliers” that allow spurious claims to jobs created to be easily calculated, under his leadership it now publishes a very prominent warning:

The most significant limitation of economic impact analysis using multipliers is the implicit assumption that the economy has no supply–side constraints. That is, it is assumed that extra output can be produced in one area without taking resources away from other activities, thus overstating economic impacts.

It concedes that users “can compile their own multipliers as they see fit”.

They shouldn’t, and we should be suspicious when they do.![]()

John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society and NATSEM, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

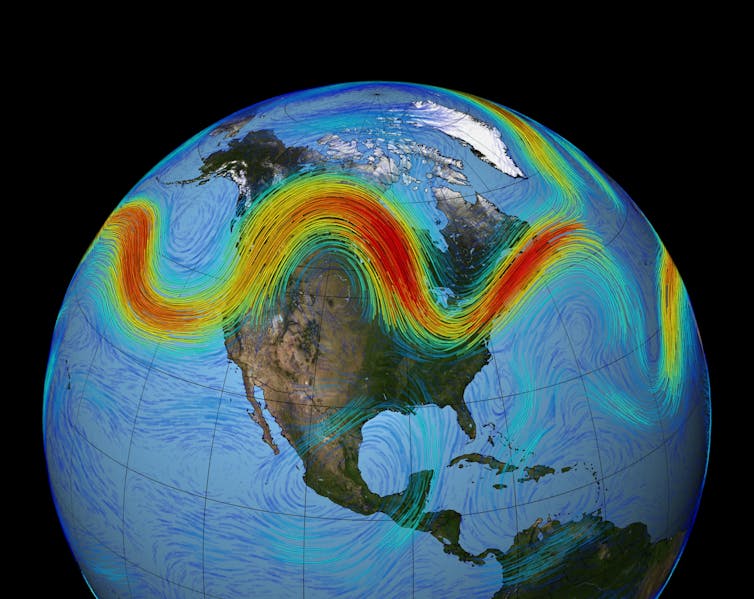

The North American heatwave shows we need to know how climate change will change our weather

Eight days ago, it rained over the western Pacific Ocean near Japan. There was nothing especially remarkable about this rain event, yet it made big waves twice.

First, it disturbed the atmosphere in just the right way to set off an undulation in the jet stream - a river of very strong winds in the upper atmosphere - that atmospheric scientists call a Rossby wave (or a planetary wave). Then the wave was guided eastwards by the jet stream towards North America.

Along the way the wave amplified, until it broke just like an ocean wave does when it approaches the shore. When the wave broke it created a region of high pressure that has remained stationary over the North American northwest for the past week.

This is where our innocuous rain event made waves again: the locked region of high pressure air set off one of the most extraordinary heatwaves we have ever seen, smashing temperature records in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and in Western Canada as far north as the Arctic. Lytton in British Columbia hit 49.6℃ this week before suffering a devastating wildfire.

What Makes A Heatwave?

While this heatwave has been extraordinary in many ways, its birth and evolution followed a well-known sequence of events that generate heatwaves.

Heatwaves occur when there is high air pressure at ground level. The high pressure is a result of air sinking through the atmosphere. As the air descends, the pressure increases, compressing the air and heating it up, just like in a bike pump.

Sinking air has a big warming effect: the temperature increases by 1 degree for every 100 metres the air is pushed downwards.

High-pressure systems are an intrinsic part of an atmospheric Rossby wave, and they travel along with the wave. Heatwaves occur when the high-pressure systems stop moving and affect a particular region for a considerable time.

When this happens, the warming of the air by sinking alone can be further intensified by the ground heating the air – which is especially powerful if the ground was already dry. In the northwestern US and western Canada, heatwaves are compounded by the warming produced by air sinking after it crosses the Rocky Mountains.

How Rossby Waves Drive Weather

This leaves two questions: what makes a high-pressure system, and why does it stop moving?

As we mentioned above, a high-pressure system is usually part of a specific type of wave in the atmosphere – a Rossby wave. These waves are very common, and they form when air is displaced north or south by mountains, other weather systems or large areas of rain.

Read more: We've learned a lot about heatwaves, but we're still just warming up

Rossby waves are the main drivers of weather outside the tropics, including the changeable weather in the southern half of Australia. Occasionally, the waves grow so large that they overturn on themselves and break. The breaking of the waves is intimately involved in making them stationary.

Importantly, just as for the recent event, the seeds for the Rossby waves that trigger heatwaves are located several thousands of kilometres to the west of their location. So for northwestern America, that’s the western Pacific. Australian heatwaves are typically triggered by events in the Atlantic to the west of Africa.

Another important feature of heatwaves is that they are often accompanied by high rainfall closer to the Equator. When southeast Australia experiences heatwaves, northern Australia often experiences rain. These rain events are not just side effects, but they actively enhance and prolong heatwaves.

What Will Climate Change Mean For Heatwaves?

Understanding the mechanics of what causes heatwaves is very important if we want to know how they might change as the planet gets hotter.

We know increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is increasing Earth’s average surface temperature. However, while this average warming is the background for heatwaves, the extremely high temperatures are produced by the movements of the atmosphere we talked about earlier.

So to know how heatwaves will change as our planet warms, we need to know how the changing climate affects the weather events that produce them. This is a much more difficult question than knowing the change in global average temperature.

How will events that seed Rossby waves change? How will the jet streams change? Will more waves get big enough to break? Will high-pressure systems stay in one place for longer? Will the associated rainfall become more intense, and how might that affect the heatwaves themselves?

Read more: Explainer: climate modelling

Our answers to these questions are so far somewhat rudimentary. This is largely because some of the key processes involved are too detailed to be explicitly included in current large-scale climate models.

Climate models agree that global warming will change the position and strength of the jet streams. However, the models disagree about what will happen to Rossby waves.

From Climate Change To Weather Change

There is one thing we do know for sure: we need to up our game in understanding how the weather is changing as our planet warms, because weather is what has the biggest impact on humans and natural systems.

To do this, we will need to build computer models of the world’s climate that explicitly include some of the fine detail of weather. (By fine detail, we mean anything about a kilometre in size.) This in turn will require investment in huge amounts of computing power for tools such as our national climate model, the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator (ACCESS), and the computing and modelling infrastructure projects of the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) that support it.

We will also need to break down the artificial boundaries between weather and climate which exist in our research, our education and our public conversation.![]()

Christian Jakob, Professor in Atmospheric Science, Monash University and Michael Reeder, Professor, School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The government is clamping down on charities — and it could have a chilling effect on peaceful protest

The Australian government introduced new regulations last week that could have a major chilling effect across Australia’s diverse charities sector.

The government’s aim was clear: the regulations are intended to target “activist organisations”, and specifically crack down on “unlawful behaviour”.

Despite this rhetoric, there is no evidence unlawful behaviour by charities is a problem of any significance. By clamping down on charities in this way, the government is not only curtailing their ability to organise peaceful protests, it is imposing more unnecessary red tape on an already highly-regulated sector.

What Would The Regulations Do?

The regulations would give the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC) new powers to take action against a charity if it commits, or fails to adequately ensure its resources aren’t used to commit, certain types of “summary offences”.

These are generally a less serious type of criminal offence, and can include acts such as trespassing, unlawful entry, malicious damage or vandalism.

If the ACNC commissioner believes a charity is not complying with the regulations, they would be able to take enforcement action, which may include deregistering the charity. This would lead to the charity losing tax concessions — one of the incentives for people to donate to them.

In effect, the regulations mean that if a charity organised a protest in front of a government department and initially refused to leave, this could be considered trespassing. And this could then be grounds to have the charity deregistered.

Are These Regulations Necessary?

There is little, if any, evidence of a need for the regulations.

First, a comprehensive review of the ACNC legislation commissioned by the government in 2018 did not identify any issues with unlawful behaviour by charities.

In fact, the review recommended removing the ACNC’s existing power to take action against charities that commit serious breaches of the law. It pointed out that charities must already comply with all laws that they are subject to, and it is not the ACNC’s responsibility to monitor compliance or impose sanctions for breaches.

Despite this, the new regulations would extend the reach of the ACNC and expand its existing powers even further.

Read more: Animal rights activists in Melbourne: green-collar criminals or civil 'disobedients'?

And importantly, there is no evidence charities — or their staffs or volunteers — are engaging in widespread unlawful activity. When questioned at a recent Senate Estimates hearing, ACNC Commissioner Gary Johns said the commission’s data did not indicate this was a problem.

Even the government’s own regulatory impact assessment asserts only a “small number” of charities have engaged in unlawful behaviour. However, even this claim is not backed up by solid evidence, with the assessment saying it is based on

media coverage in recent years in relation to protests on forestry, mining and farming lands.

Charities Are Already Highly Regulated

Charities in Australia are already highly regulated and subject to a broad range of obligations. They must also abide by any number of laws, for example, occupational health and safety and criminal laws.

And the ACNC already has extensive investigation and compliance powers. If charities breach any of the laws they are subject to, they can be sanctioned just like other organisations — and the same applies to their staff.

In addition, charities are already required to take steps to ensure their directors comply with duties, such as acting with reasonable care and diligence. This includes monitoring and managing risks arising from a charity’s activities.

Drafted In A Vague Way

Perhaps most concerningly, the proposed regulations are worded in a very vague manner, and although improvements were made in response to public consultation on a draft version, major problems remain.

First, they require a charity to “maintain reasonable internal control procedures” to prevent its resources from being used to promote unlawful activities.

According to the regulations, this could cover things such as who can access or use a charity’s funds, premises or social media accounts, and what kind of training charity directors and employees must undertake.

What is “reasonable” in this context involves making very subjective judgements. While the ACNC will provide guidance to charities on this, many organisations will still face considerable uncertainty.

Read more: Australian charities are well regulated, but changes are needed to cut red tape

Further, the regulations would not require a conviction, the laying of charges, or even a formal allegation of an offence being committed before the ACNC can take action. The wording only refers to “acts or omissions that may be dealt with” as a summary offence.

This is very open-ended language, but the crux of it is that a charity could be deregistered because it did something the ACNC commissioner thinks is a summary offence. The action itself, however, may not actually meet the criteria for a summary offence because that’s something only a court can determine.

The ACNC commissioner is the ultimate decision maker on these matters. The regulations do not include any factors or criteria that need to be considered when making a decision, other than saying the ACNC “may” (there’s that word again) consult with law enforcement or other relevant authorities.

The Chilling Effect Of The Regulations

Even if a charity is deregistered but then successfully appeals a decision, it may no longer have access to tax concessions, it may lose its donors and other supporters, and it may have its reputation tarnished within the community.

The ACNC seeks to implement the law as it understands it. Its focus is on providing guidance to charities rather than using strong enforcement powers straight away. But the vagueness and breadth of the regulations may lead to misunderstandings or regulatory overreach, and create a more uncertain environment for charities.

They will also impose yet another requirement that charity boards and management must consider. Given charities are already well-regulated, if anything, they need unnecessary red tape removed rather than having more of it imposed on them.

And the regulations will likely have a chilling effect. Charities will be more cautious when it comes to organising public advocacy activities such as peaceful protests — or steer clear of them altogether — in order to avoid falling afoul of the regulations. Such activities are an important part of Australia’s democracy.

Can The Regulations Be Stopped?

Although the regulations have been made, they cannot come into force until they have been tabled in both chambers of parliament, and the disallowance period has passed.

If a disallowance motion is successful in the House or Senate, then the regulations will be invalid and will not take effect. Given the government does not have a majority in the Senate, this is a possibility.

Much is riding on the crossbenchers — not just the impact the regulations would have on individual charities, but also the kind of society we want Australia to be.![]()

Krystian Seibert, Industry Fellow, Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Meet the broad-toothed rat: a chubby-cheeked and inquisitive Australian rodent that needs our help

Am I not pretty enough? This is the first article in The Conversation’s series introducing you to the unloved Australian animals that need our help

When people think of rodents, they usually think of introduced species such as the black rat and house mouse. But Australia actually has around 54 native rodent species, which live in a vast range of habitats across the continent, from the ocean to spinifex-dotted deserts.

My research focuses on the broad-toothed rat, a vulnerable, chubby-cheeked rodent that lives in parts of Tasmania and pockets of southern Victoria. It even thrives beneath the snow in the Australian Alps and in Barrington Tops in New South Wales.

You may have already heard of the broad-toothed rat from articles about the damage feral horses do in Kosciuszko National Park, or as one of the species living near the highly photogenic mountain pygmy possum.

But I don’t want to turn this into a debate about feral horses or a popularity contest with the pygmy possum. As the broad-toothed rat rarely, if ever, gets its own story, I want to introduce you properly to this fascinating, unique, and beautiful species, focusing on those that live in Kosciuszko National Park.

A Very Special Rodent

The broad-toothed rat (Mastacomys fuscus) is often referred to by wildlife scientists as Australia’s guinea pig. However, it belongs to a very different group of rodents.

Weighing approximately 150 grams — about the same size as the introduced black rat — the broad-toothed rat looks like any typical rodent at first glance.

But with its chocolate coloured coat, long, soft, almost luxurious fur, little to no musky smell, chubby face, and calm and inquisitive nature, it bears little resemblance to any introduced species.

The broad-toothed rat gets its name from its wider-than-usual molar teeth, which help it chew the stalks of sedges and grasses. It also nests in these grasses, and moves unseen through an elaborate network of tunnel-like runways. The broad-toothed rat shares these runways with other small mammal species, such as the bush rat and the dusky antechinus.

In winter, low shrubs hold the snow off the ground, creating a subnivean space (the area between snow and terrain). This creates a relatively cosy environment, keeping the temperature of the runways above zero, even when the air above this space is much colder.

When most of the snow has melted in October, the broad-toothed rat’s breeding season is triggered and generally lasts until March the next year. They have on average only two to three young, and these are unusual because they’re partially furry at birth.

Why Native Rodents Matter

Native rodents are essential in many ecosystems. They disperse seeds by forming seed caches. This is when rats keep seeds in storage to eat, and when they vacate their burrow, the uneaten seeds can germinate.

They often have the role of ecosystem engineers, providing burrows and runways for small mammals that cannot dig their own. This is particularly common for desert rodent species that dig burrows, which are then used by small marsupials.

Native rodents may also be early indicators of local environmental change, like furry canaries in a coal mine. When their populations decline, populations of other native species, such as small marsupials, also decline soon after because whatever affects the rodents, will affect other small mammals.

But Broad-Toothed Rats Are In Danger

Of the 54 species of native rodent, 16 are vulnerable or endangered. Their biggest threats include introduced rodents who compete for resources, predation by cats and foxes, and general human activity such as land clearing.

While the damage feral horses do to the vegetation in the Australian Alps is a well-known problem, the broad-toothed rat also has many other threats.

It’s currently classified as vulnerable or near threatened in much of its range. While the exact number of individuals is difficult to determine, it’s clear the rat’s range is getting smaller, in part due to climate change-induced reduction in snow cover.

Since their reproductive behaviours are triggered by the environment, changes in temperature and snow cover can be catastrophic. Reduced snow cover also means less protection during the colder months.

Another reason these rats are unusual among native Australian rodents is they’re entirely herbivorous. Any variation in temperature, rainfall, snow melt, or drainage alters the types of vegetation that grows. And changes in available grasses reduce the food and nesting material the rats have access to.

In the Australian Alps, broad-toothed rats have very few native predators. But a 2002 study found foxes, and perhaps feral cats, prefer eating broad-toothed rats over other small mammal species. Whether this is due to the rats being easier to catch or because they’re tastier is unclear.

Because the broad-toothed rat lives in Kosciuszko National Park, it also lives side-by-side with the ski industry, and will even inhabit the disturbed areas alongside ski runs. But ski resorts change drainage patterns, groundwater and surface water, changing the type of vegetation that grows.

With the continued reduction in natural snow from climate change, and heavier reliance on artificial snow for tourism, the impact on the fragile alpine ecosystem will need to be closely monitored so we can protect the broad-toothed rat.

Three Ways You Can Help

Unfortunately, just having “rat” in its name can turn people away from caring about this species, as rats are typically seen as destructive and diseased.

But does an animal have to be cute and endearing to gain public and political sympathy? Well, unfortunately, yes.

Research from 2016 shows native rodents are the least cared about and researched of all animals, and they gain the least amount of funding.

So, what can the average person do?

First and foremost, learn about what species live where you live, and make sure you can correctly identify a native rodent from an introduced species.

Second, when you hear people complain about all rodents, tell them about our natives, and even show them a photo. Most people have a change of heart once they see one.

Finally, appreciate that our native rodents are just as important as our marsupials, monotremes, bats, amphibians, reptiles and birds, and are just as affected by our activities as any other animal group.

Chris Wacker, Postdoctoral Research Fellow - School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW State Government's Plans To Open Western NSW To Coal Mining Open For Feedback

- Forty-five recorded Aboriginal heritage sites and an additional 13 sites that are restricted and location data not supplied in the proposed coal release areas.

- Twenty-two threatened fauna species and six threatened flora species including the koala, the critically endangered regent honeyeater and the endangered spotted-tailed quoll, as well as four plant species endemic to the Rylstone/western Wollemi area.

- One thousand, eight hundred and fifty-four hectares of groundwater dependant ecosystems.

- Six thousand, six hundred and thirty-four hectares of potential threatened ecological communities.

- Thirty-six water bores.

- One hundred and twenty kilometres of stream channels in good condition and 118 kilometres of stream channels classed as a high level of fragility.

New Plan To Revitalise NSW's Oldest Park By Installing Mountain Bike Trails

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park, Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Planning Considerations

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Plan of Management

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Mountain Biking Plan

Nature is a public good. A plan to save it using private markets doesn’t pass muster

As the health of Australia’s environment continues to decline, the federal government is wagering on the ability of private markets to help solve the problem. So is this a wise move? The evidence is not at all encouraging.

This year’s federal budget included A$32.1 million to promote so-called “biodiversity stewardship”, in which farmers who adopt more sustainable practices can earn money on private markets. The funding will be used to trial new programs to protect existing native vegetation, implement a certification scheme and set up a trading platform.

It all sounds very promising. But sadly, the experience of environmental markets and certification schemes to date suggests farmers may not embrace the opportunities. In fact, preliminary research funded by the government suggests the odds are well and truly stacked against this approach succeeding.

Environmental markets cannot adequately compensate for decades of diminished government funding for long term, reliable measures to promote better land management.

What’s The Plan All About?

Agriculture covers 58% of Australia’s land mass. This means farmers are crucial to maintaining a healthy environment upon which production, communities and the economy depend.

Federal Agriculture Minister David Littleproud said the new funding means farmers will be paid to undertake biodiversity projects – “a win-win for farmers and the environment”. In an interview with the ABC, Littleproud said “we want the market to come and pay our farmers for this, not the Australian taxpayer”.

The new funding will pay for:

a “carbon + biodiversity” pilot project to develop a market-based mechanism to reward farmers for increasing biodiversity

an “enhanced remnant vegetation” pilot that will pay farmers to protect remnant native vegetation with high conservation value

a proposed “Australian Farm Biodiversity Certification Scheme” to identify best-practice ways to sustain and build biodiversity.

So how do these markets work? Farmers and other land managers undertake environmental projects such as protecting endangered native species, increasing tree cover or reducing competition from invasive pest species. These projects have been assessed and accredited – usually by a government entity or independent third party – to ensure their integrity.

Farmers earn “credits” in exchange for the activity they undertake, which are then sold to “funders” such as corporations that want to improve their environmental credentials, philanthropic organisations and others.

The government has previously committed A$34 million to develop and trial biodiversity stewardship approaches. This included A$4 million to the National Farmers Federation (NFF) to start developing a certification scheme.

‘Workability’ Problems

In 2020, the NFF engaged the Australian Farm Institute (AFI) to evaluate the literature on existing certification schemes and to gauge landholders’ views. The report identified myriad problems.

The AFI noted several issues surrounding data collection and reporting. Certification schemes are data-hungry: they require baseline data (information collected before a project starts), measurable outcomes and a way to monitor progress and verify results. But diminished public spending means such data are often not readily available.

Also, biodiversity conservation can take decades. This can conflict with the interests of farmers, and of project funders that often operate within shorter planning horizons. This may limit the type, credibility and longevity of projects accredited for funding.

And many existing schemes are yet to demonstrate, on a cost-benefit analysis, any appreciable economic advantage to farmers. Under the Queensland Land Restoration Fund scheme, for example, the AFI said “farmers generally want more money than is offered for the carbon credits produced”. If that remains the case, widespread uptake seems unlikely.

Barriers To Participation

The time, energy and costs of applying to participate in a biodiversity stewardship scheme can limit participation. For instance, the AFI’s review of stakeholder views noted it took one Queensland farmer 18 months to navigate the application process under the state’s Land Restoration Fund. And the fund involves hefty startup costs, including A$15,000-20,000 for a baseline biodiversity report and A$10,000 for initial certification.

Some schemes have attempted to get around this. For example, the Land Restoration Fund now offers to pay the costs of third-party agents employed to prepare applications. But overall administrative costs remain substantial and are likely to remain a deterrent to smaller operators.

Rules governing certification schemes can also penalise early adopters of sustainable farming methods. The schemes often require “additionality”, which means farmers cannot be rewarded for undertaking activity that would have occurred had the scheme not existed. So those already using best-practice methods – such as minimum tillage, organic farming or retaining native vegetation – often cannot take part. This is a particularly sore point for many farmers.

And almost inevitably in environmental stewardship schemes, ongoing funding to farmers is premised on progress against pre-determined benchmarks, such as storing a specified amount of carbon in landscapes by planting trees. Unfortunately, life in the bush is far from pre-determined. Disruptive events – such as drought, fire, falling commodity prices or new trade barriers - are run of the mill.

It’s a big stretch for corporate funders and contract negotiators to accommodate these unknown variables in their benchmarks. This means farmers must insure themselves against natural events (to the extent available) adding again to the costs of participation.

Nature Belongs To All Of Us

Land managers are the primary stewards of Australia’s unique environment. Yet they receive the least government funding of any OECD country aside from New Zealand.

The environment needs immediate and sustained support. Whatever the lure and potential of environmental markets and certification schemes, the evidence strongly suggests private funding should not be relied on to preserve, restore and sustain our natural landscapes.

The environment is a public good, and requires adequate and substantial public funding.

Philippa England, Senior Lecturer, Griffith Law School, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Almost 60 coral species around Lizard Island are ‘missing’ – and a Great Barrier Reef extinction crisis could be next

The federal government has opposed a recommendation by a United Nations body that the Great Barrier Reef be listed as “in danger”. But there’s no doubt the natural wonder is in dire trouble. In new research, my colleagues and I provide fresh insight into the plight of many coral species.

Worsening climate change, and subsequent marine heatwaves, have led to mass coral deaths on tropical reefs. However, there are few estimates of how reduced overall coral cover is linked to declines in particular coral species.

Our research examined 44 years of coral distribution records around Lizard Island, at the northern end of the Great Barrier Reef. We found 16% of coral species have not been seen for many years and are at risk of either local extinction, or disappearing from parts of their local range.

This is alarming, because local extinctions often signal wider regional – and ultimately global – species extinction events.

Sobering Findings

The Lizard Island reef system is 270 kilometres north of Cairns. It has suffered major disturbances over the past four decades: repeated outbreaks of crown-of-thorns seastars, category 4 cyclones in 2014 and 2015, and coral bleaching events in 2016, 2017 and 2020.

Our research focused on “hermatypic” corals around Lizard Island. These corals deposit calcium carbonate and form the hard framework of the reef.

We undertook hard coral biodiversity surveys four times between 2011 and 2020, across 14 sites. We combined the results with published and photographic species records from 1976 to 2020.

Of 368 hard coral species recorded around Lizard Island, 28 (7.6%) have not been reliably recorded since before 2011 and may be at risk of local extinction. A further 31 species (8.4%) have not been recorded since 2015 and may be at risk of range reduction (disappearance from parts of its local range).

The “missing” coral species include:

Acropora abrotanoides, a robust branching shallow water coral that lives on the reef crest and reef flat has not been since since 2009

Micromussa lordhowensis, a low-growing coral with colourful fleshy polyps. Popular in the aquarium trade, it often grows on reef slopes but has not been seen since 2005

Acropora aspera, a branching coral which prefers very shallow water and has been recorded just once, at a single site, since 2011.

The finding that 59 coral species are at risk of local extinction or range reduction is significant. Local range reductions are often precursors to local species extinctions. And local species extinctions are often precursors to regional, and ultimately global, extinction events.

Each coral species on the reef has numerous vital functions. It might provide habitat or food to other reef species, or biochemicals which may benefit human health. One thing is clear: every coral species matters.

Read more: The outlook for coral reefs remains grim unless we cut emissions fast — new research

A Broader Extinction Crisis?

As human impacts and climate threats mount, there is growing concern about the resilience of coral biodiversity. Our research suggests such concerns are well-founded at Lizard Island.

Coral reef communities are dynamic, and so detecting species loss can be difficult. Our research found around Lizard Island, the diversity of coral species fluctuated over the past decade. Significant declines were recorded from 2011 to 2017, but diversity recovered somewhat in the three following years.

Local extinctions often happen incrementally and can therefore be “invisible”. To detect them, and to account for natural variability in coral communities, long-term biodiversity monitoring across multiple locations and time frames is needed.

In most locations however, data on the distribution and abundance of all coral species in a community is lacking. This means it can be hard to assess changes, and to understand the damage that climate change and other human-caused stressors are having on each species.

Only with this extra information can scientists conclusively say if the level of local extinction risk at Lizard Island indicates a risk that coral species may become extinct elsewhere – across the Great Barrier Reef and beyond.

Zoe Richards, Senior Research Fellow, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It takes more than words and ambition: here’s why your city isn’t a lush, green oasis yet

The idea of transforming cities from concrete jungles to urban forests is a popular one, and there have been some truly inspiring, exemplar projects in recent years. The transformation of a Seoul freeway to Cheonggyecheon parkland, exposing the historical river that once flowed there, is one celebrated example (pictured above).

Projects like this are commendable, as urban nature has considerable benefits including, for instance, improving mental health and boosting urban biodiversity.

But has your city actually turned into a lush oasis yet? No, neither has ours.

Our new research looked at what’s holding back greening in our cities. And we found the issue is often internal — cities just aren’t really set up to deliver their plans. Fortunately, this is a very fixable problem.

Cities Are Falling Short

The global experience is that greening a grey city isn’t as simple as setting a bold target and writing a glossy strategy. All over the world, we’re seeing that urban greening projects and plans run into significant barriers.

Results are slow, successful pilot projects aren’t scaled up, and in some cases the work simply doesn’t happen.

Read more: Thousands of city trees have been lost to development, when we need them more than ever

Many cities are still losing green infrastructure, especially trees on streets. A recent report commissioned by the Australian Conservation Foundation found canopy cover in all major Australian cities except for Hobart and Canberra had declined in the last decade.

So, what’s going on? Well, the simple answer is that, despite being ambitious and well-intentioned, cities rarely have the full set of skills and capabilities required to successfully implement their plans.

Here’s What It Takes

Dozens of studies of barriers to urban greening from across the planet have shown us where things go wrong.

One way to think about these barriers simply and constructively is to instead see them as a set of “success factors” cities need in place to avoid typical stumbling blocks. Here are a few that cities should keep in mind:

First, urban greening projects need strong leadership and support at the political and executive level, alongside a well-resourced project team.

Often greening teams assigned to deliver major plans have only one or two staff members, an inadequate budget, and unrealistic timeframes that don’t correspond to the project’s ambition.

Read more: People's odds of loneliness could fall by up to half if cities hit 30% green space targets

A positive, supportive organisational culture is also necessary, recognising new projects often have inherent risks and trade-offs.

Delivering major urban greening projects often means reclaiming road space, procuring private property, or replacing trees and plants that struggle to establish. These are normal teething difficulties, but they can lead to projects being labelled “failures” when organisations don’t have a healthy attitude to risk.

Access to skilled, supportive teams is key. Greening urban spaces requires smooth technical collaboration between engineers, designers, horticulturists and maintenance crews.

One of the classic problems is that one or more key collaborators isn’t on board, and as a result is either unhelpful or actively obstructive.

Finally, effective community engagement is needed. Many urban greening projects need public support or consent from property owners to be successful.

This can be as direct as forming a legal agreement with a major property owner to establish a green roof, or something broader like involving the public in selecting what tree species are planted in their street.

Testing The Success Factors

In our research paper, we built a simple self-assessment tool (you can download here) based on the above success factors. This tool can help cities identify whether they’re capable to “walk the talk”, and where to improve.

We used it to explore urban greening in a range of cities participating in Urban GreenUP — a research project aimed at re-naturing cities in the European Union to reduce heat and flooding impacts, improve air and water quality, and create urban habitat.

Through Urban GreenUP, we’ve seen a range of innovative nature-based projects begin. This includes a major streambank restoration project in Izmir, Turkey that delivered 26.5 hectares of new parkland, and floating gardens in Liverpool to enhance water quality and biodiversity.

But across the cities we studied, many struggled with the same three issues, even as some delivered strong results: not enough staff, no clear processes for actually delivering the greening, and risk-averse organisational culture that made doing new things difficult.

When we spoke to staff in these cities about their results, they often already knew these were barriers, but they didn’t have the power to really resolve them. The issues tend to be well above the pay grade of officers in greening teams.

Greening Depends On Leaders

These findings highlight the reforms required to get urban greening out of the starting blocks, at least in the cities we studied.

Many local governments are likely already familiar with the issues we observed, but our study suggested that, in addition to some of the big headline problems we listed above, individual cities will each face their own particular challenges.

Fixing these problems largely depends on getting executive and political leaders with clout involved to assign resources, streamline processes and modernise attitudes to risk. It’ll be a hard sell — these fiddly organisational reforms aren’t as fun as giving bold speeches or cutting ribbons.

Read more: 3 ways nature in the city can do you good, even in self-isolation

Still, if these these powerful leaders can roll up their sleeves and ensure their organisations have all the success factors in place, the rewards are clear.

Delivering urban greening at large scale will leave our cities not only more pleasant and attractive, but also healthier, and more resilient to heatwaves and flooding.

Correction: a previous version of this article said canopy cover in all major Australian cities except for Hobart had declined. This has been updated to include Canberra.![]()

Thami Croeser, Research Officer, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University; Georgia Garrard, Senior lecturer, School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, The University of Melbourne, The University of Melbourne, and Sarah Bekessy, Professor in Sustainability and Urban Planning, Leader, Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Research Group (ICON Science), RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Canopy Keepers Art Challenge For Pittwater's Youngsters

Did you know that trees communicate using underground fungal networks? Or that, like us, they survive best in communities?

There's lots to find out about the hidden life of trees and so Canopy Keepers are inviting Pittwater primary students to create an image that reveals an aspect of the hidden life of trees. Drawings, diagrams, painting, mixed media and photos are all welcome. Chosen artworks will be made into a calendar for 2022 for sale (to cover costs) in the local community.

Get busy youngsters! Now is a great time to engage in a fun art challenge exploring our beautiful trees.

Email your work to cobbmilly@gmail.com by September 6th.

Curious Kids: Why are leaves green?

This is an article from Curious Kids, a series for children. The Conversation is asking kids to send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. All questions are welcome – serious, weird or wacky!

Why are leaves green? – Indigo, age 6, Elwood.

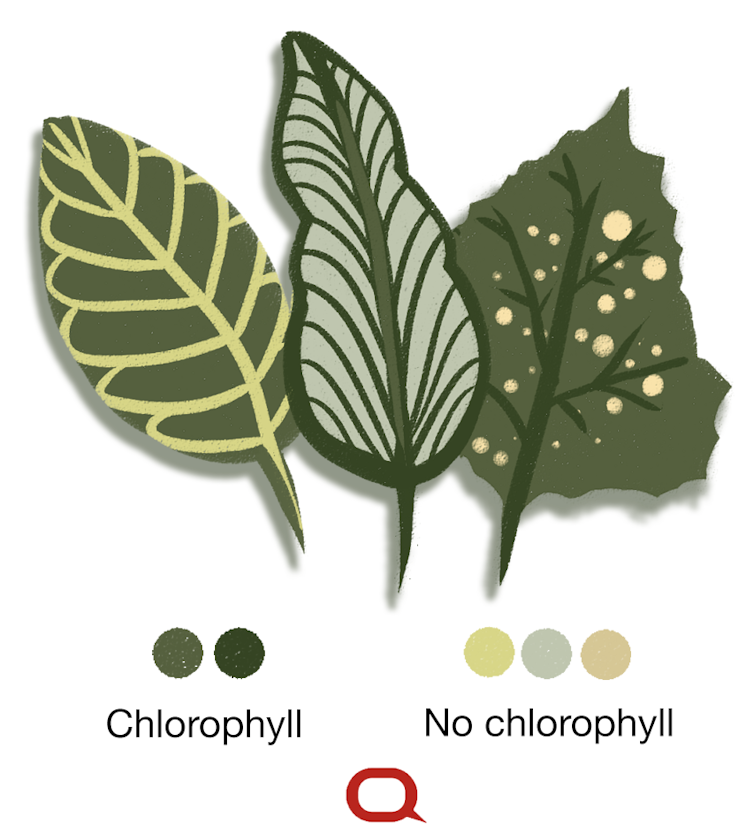

The leaves of most plants are green, because the leaves are full of chemicals that are green.

The most important of these chemicals is called “chlorophyll” and it allows plants to make food so they can grow using water, air and light from the sun.

This way that a plant makes food for itself is called “photosynthesis” and it is one of the most important processes taking place on the whole planet.

Without photosynthesis there would be no plants or people on Earth. Dinosaurs would not have been able to breathe and the air and oceans would be very different from those we have today. So the green chemical chlorophyll is really important.

All leaves contain chlorophyll, but sometimes not all of the leaf has chlorophyll in it. Some leaves have green and white or green and yellow stripes or spots. Only the green bits have chlorophyll and only those bits can make food by photosynthesis.

If you’re really good at noticing things, you might have seen plants and trees with red or purple leaves – and the leaves are that colour all year round, not just in autumn.

These leaves are still full of our important green chemical, chlorophyll, just like any other ordinary green leaf. However, they also have lots of other chemicals that are red or purple – so much of them that they no longer look green. But deep down inside the leaves the chlorophyll is still there and it’s still green.

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. You can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

* Tell us on Twitter by tagging @ConversationEDU with the hashtag #curiouskids, or

* Tell us on Facebook

Please tell us your name, age and which city you live in. You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Curious Kids: Why are fern leaves shaped the way they are, and are all ferns identical?

Curious Kids, is a series for children where kids send in questions and we ask an expert to answer them.

Dear Conversation, I am a curious kid and while I was bush walking I noticed these ferns. I wanted to know why fern leaves are shaped they way they are, and if they don’t have flowers does that mean all ferns are identical? Thank you for your help – Heather, age 8, Brisbane

You’ve asked two great questions, which I’ll answer one by one.

Read more: Curious Kids: Are zombies real?

Why Are Fern Leaves Shaped The Way They Are?

Ferns are a very old group of plants that came along more than 200 million years before the dinosaurs walked the Earth. They were food for the plant-eating dinosaurs and they’re really great survivors.

Fern leaves are shaped the way they are because each species has adapted or changed over time to better suit its particular environment. That’s all thanks to evolution.

Some ferns are small and grow on other plants in wet places, while others are tall and tough. There are thousands of types of ferns, which grow in different environments all over the world.

The leaves of ferns are called fronds and they all have different sizes, shapes and textures. There are the tiny, soft fronds of maidenhair ferns.

Then there are the tough, leathery fronds of bracken and the large fronds of tree ferns that may be more than 2 metres long.

The fronds of many ferns begin as small, curled balls. As they grow, they change shape and start to look like the neck of a violin. That’s why they’re called fiddleheads.

Many people think different tree ferns look the same, but if you look closely the various species are very different in size, shape and texture.

If They Don’t Have Flowers Does That Mean All Ferns Are Identical?

Since ferns are such an old group of plants, they don’t have flowers or cones. Ferns were around for about 200 million years before plants with flowers came along, so they make new ferns in a different way.

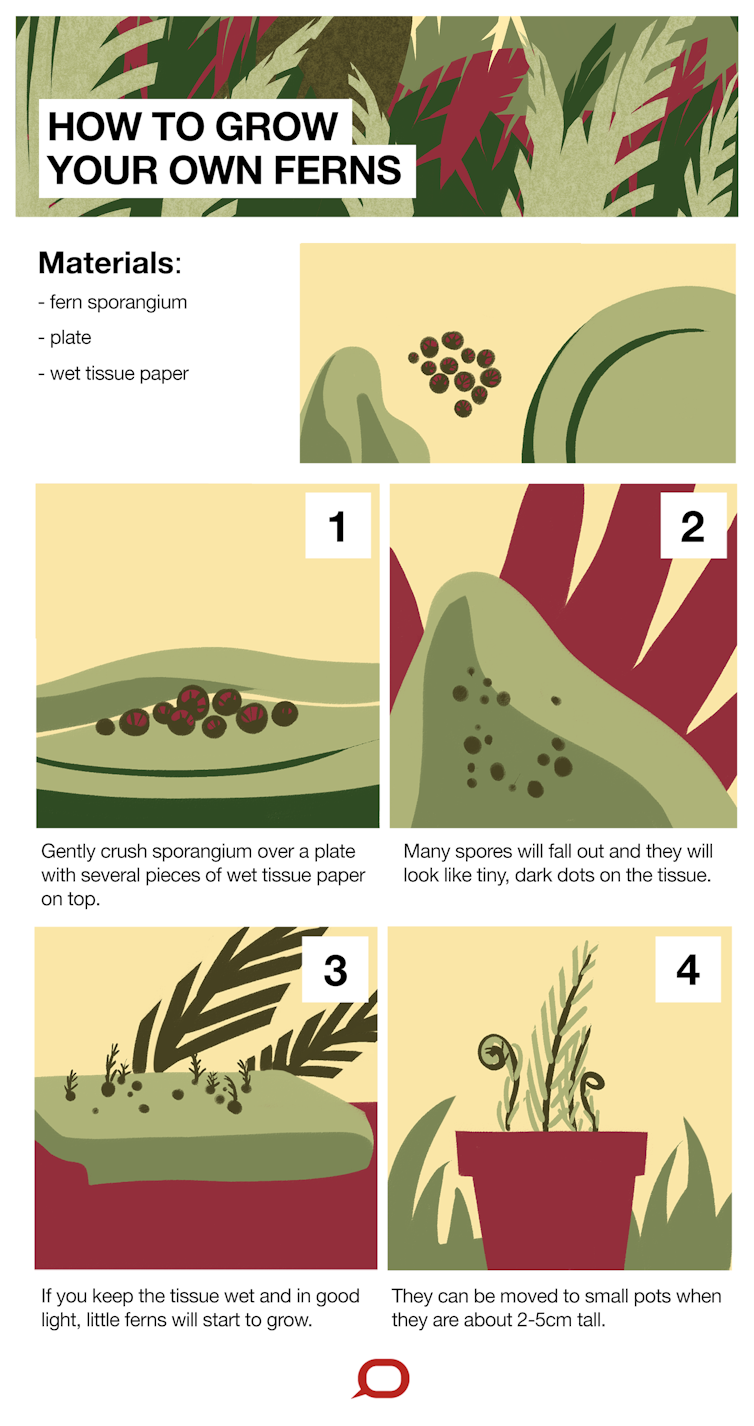

Most ferns use things called spores, which are tiny and look like pepper. They can travel long distances on the wind or by getting a lift from a passing animal.

During some times of the year, if you look underneath the fronds, you can see the sporangium (that’s the part of the leaf where the spores are made).

Some look like tiny bunches of grapes, some look like a little brown purse, and others like a dome. Often the sporangium starts out light green and as it ripens, turns dark brown.

Ferns spores develop into what scientists call “gametophytes”, which usually look flat, green and spongy. These gametophytes produce eggs and sperm.

The egg or sperm from one gametophyte can join up with the egg or sperm from a different gametophyte.

When that happens, the baby ferns produced this way are not genetically identical to the parent or to each other. It only works properly if there’s enough water around so that the sperm can swim to the eggs. You can read more about it here.

Some ferns, however, can sprout ferns from their underground stems or from special bulb-shaped bits on their fronts called “bulbils”. When that happens, the baby fern is genetically identical to its parent.

If you want to grow your own ferns, follow the instructions below. It is great fun to watch them grow.

Read more: Curious Kids: what started the Big Bang?

Hello, curious kids! Have you got a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to us. You can:

* Email your question to curiouskids@theconversation.edu.au

* Tell us on Twitter by tagging @ConversationEDU with the hashtag #curiouskids, or

* Tell us on Facebook

Please tell us your name, age and which city you live in. You can send an audio recording of your question too, if you want. Send as many questions as you like! We won’t be able to answer every question but we will do our best.![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Lighthouse Keeper

NSW State Archives Webinar - A Festival Of Film

Phoenix Program Seeking Expressions Of Interest At Manly Warringah Kayak Club

Applications are invited for the second year of the MWKC Phoenix Programme on Narrabeen Lake. This Programme is designed to deliver athletes into State and National Pathway Programs.

At this stage the Club has set target dates for athlete testing as Wednesday 28 July and Sunday 01 August, but it may be subject to change (such as weather events) so please contact us to confirm.

If you are interested in applying for the Programme, please send an email to our Head Coach, Brett Worth at brettworth36@hotmail.com and provide the following details;

Athlete Name

Athlete DOB

Brief summary of paddling experience (if any)

Brief summary of other sporting interests / achievements.

If you would like to speak with someone prior to applying you can contact;

Brett Worth, MWKC Head Coach 0466 599 423 Peter Grimes, MWKC President 0418 221 042

Details are available at this link: www.mwkc.org.au

Setting 'Personal Best' Goals Helps Students - Especially Those Academically At-Risk

How Learning Another Language Shapes The New You

If you’ve ever found yourself lost in a city overseas and needing directions or looking to spice up your bland resume, there are probably many times you wished you could call upon another language. In any case, there’s never been a better time to start learning another language than now, and there could be some unexpected upsides.

If you’ve ever found yourself lost in a city overseas and needing directions or looking to spice up your bland resume, there are probably many times you wished you could call upon another language. In any case, there’s never been a better time to start learning another language than now, and there could be some unexpected upsides.“It can be a really humbling experience to learn another language because you will find it’s not really easy to learn another language.”

“The more we engage with other languages, the more we may find that we are all human beings regardless of the different languages we speak.”

“I would encourage people to start learning the language they think they’re likely to find the most personal meaning in, whether that’s the language relevant to their family history, or hobbies, or for travel.”

Curious Kids: is light a wave or a particle?

Is light a wave or particle? — Ishan, age 15, Dubai

Hi Ishan! Thanks for your great question.

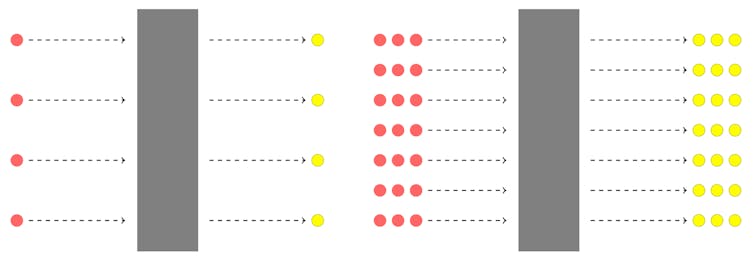

Light can be described both as a wave and as a particle. There are two experiments in particular that have revealed the dual nature of light.

When we’re thinking of light as being made of of particles, these particles are called “photons”. Photons have no mass, and each one carries a specific amount of energy. Meanwhile, when we think about light propagating as waves, these are waves of electromagnetic radiation. Other examples of electromagnetic radiation include X-rays and ultraviolet radiation.

It’s worth remembering light — regardless of whether it’s behaving like a wave or particles — will always travel at roughly 300,000 kilometres per second. The speed of light as it travels through space (or another vacuum) is the fastest phenomenon in the universe, as far as we know.

The Double-Slit Experiment

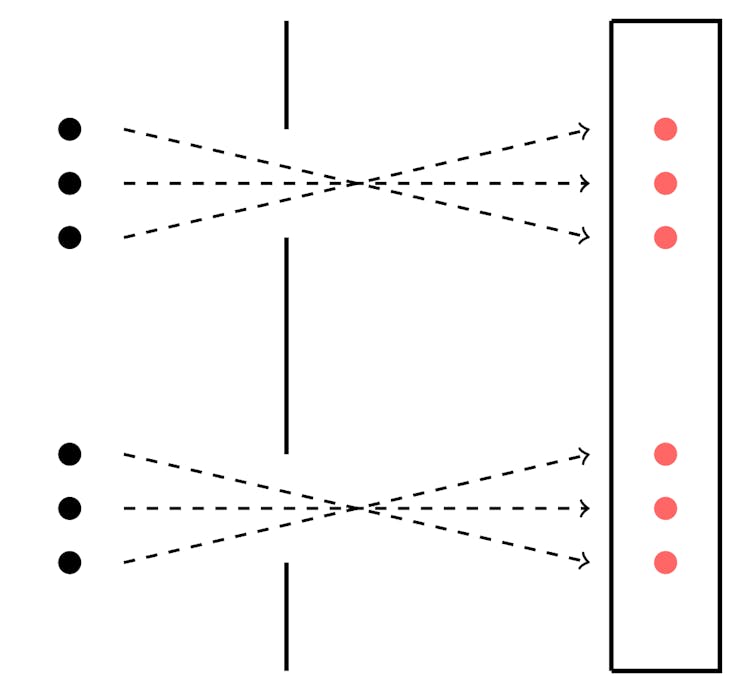

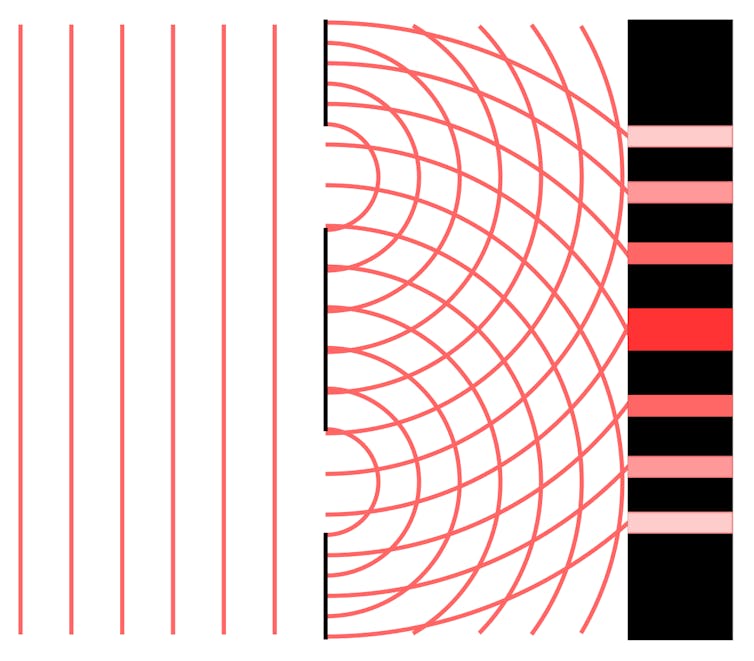

Imagine you have a bucket of tennis balls. Two metres in front of you is a solid panel with two holes in it. A metre behind that panel is a wall. You dip each ball in red paint and throw it at one hole, and then the other. A successful throw will leave a red mark on the wall behind, leaving a specific pattern of roundish dots.

Now, suppose you shoot a single beam of light at the same panel with holes in it, on the same trajectory as the tennis balls. If light is a beam of particles, or in other words a beam of photons, you would expect to see a similar pattern to that made by the tennis balls where the light particles strike the wall.

That, however, isn’t what you see. Instead, you see a complex pattern of stripes. Why?

This is because light, in this situation, acts like a wave. When we shoot a beam of light through the holes, it breaks into two beams. The two resulting waves then interfere with each other to become either stronger (constructive interference) or weaker (destructive interference).

The waves create a lattice pattern, which results in a series of stripes on the wall. In the above image, the stripes are larger and brighter at places where the waves join. The gaps between the stripes are the result of destructive interference, and the stripes are the result of constructive interference.

The Photoelectric Effect

The above experiment shows light behaving as a wave. But Albert Einstein showed us we can also describe light as being made up of individual particles of energy: photons. This is necessary to account for something called the “photoelectric effect”.

When you shoot light at a sheet of metal, the metal emits electrons: particles that are electrically charged. This is the photoelectric effect.

Prior to Einstein, scientists tried to explain the photoelectric effect by assuming light only takes the form of a wave. To understand their reasoning, imagine ripples in a pond. The ripples have peaks where the wave rises up, and troughs where it dips down.

Read more: Curious Kids: how do ripples form and why do they spread out across the water?

Now imagine there’s also a boat in the pond with Lego soldiers aboard. As the ripples reach the boat, they have the potential to throw the soldiers off. The more energy the ripples carry, the greater the force with which the soldiers will be thrown off.

And since each ripple can potentially throw off a soldier, the more ripples that reach the boat within a certain time limit, the more soldiers we can expect will be thrown off during that time.

Light waves also have peaks and troughs and therefore ripple in a similar manner. In the wave theory of light, these oscillations are linked to two properties of light: intensity and frequency.

Simply put, the frequency of a light wave is the number of peaks that pass a point in space in a given period (like when a certain number of ripples strike the boat within a specific time). The intensity corresponds to the energy of the wave (like the energy carried by each ripple in our pond).

Scientists in the 19th century pictured electrons on a sheet of metal as behaving similarly to the Lego soldiers on our raft. When light strikes the metal, the ripples should throw the electrons off.

The greater the intensity (the energy of the ripples) the faster the electrons will fly off, they thought. The higher the frequency within a specific time period, the greater the number of electrons that will get thrown off during that time — right?

What we actually see is the complete opposite! It’s the frequency of the light hitting the metal which determines the speed of the electrons as they shoot off. Meanwhile the intensity of the light, or how much energy it carries, actually determines the number of electrons flying away.

Einstein’s Explanation

Einstein had a great explanation for this peculiar observation. He hypothesised light is made of particles, and is in fact not a wave. He then linked the intensity of light to the number of photons in a beam, and the frequency of light to how much energy each photon carries.

When more photons are shot at the metal (greater intensity), there are more collisions between the photons and electrons, so a greater number of electrons are emitted. Thus, the intensity of the light determines the number of electrons emitted, rather than the speed with which they fly off.

When light’s frequency is increased and each photon carries more energy, then each electron also takes more energy from the collision — and will therefore fly off with more speed.

This explanation earned Einstein a Nobel Prize in 1921.

Wave Or Particle?

Considering all of the above, one question remains: is light a wave that sometimes looks like a particle, or a particle that sometimes looks like a wave? There is disagreement about this.

My money is on light being a wave that displays particle-like properties under certain conditions. But this remains a controversial issue — one that takes us into the exciting realm of quantum mechanics. I encourage you to dig deeper and make up your own mind!

Read more: Curious Kids: Why is the sky blue and where does it start? ![]()

Sam Baron, Associate professor, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Neanderthal Artists? Bones Decorated Over 50,000 Years Ago

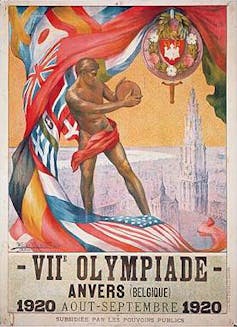

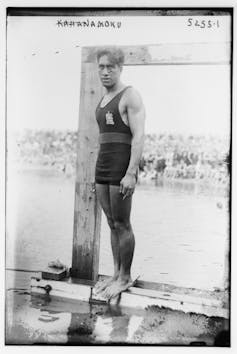

Sardines for breakfast, hypothermia rescues: the story of the cash-strapped, post-pandemic 1920 Olympics

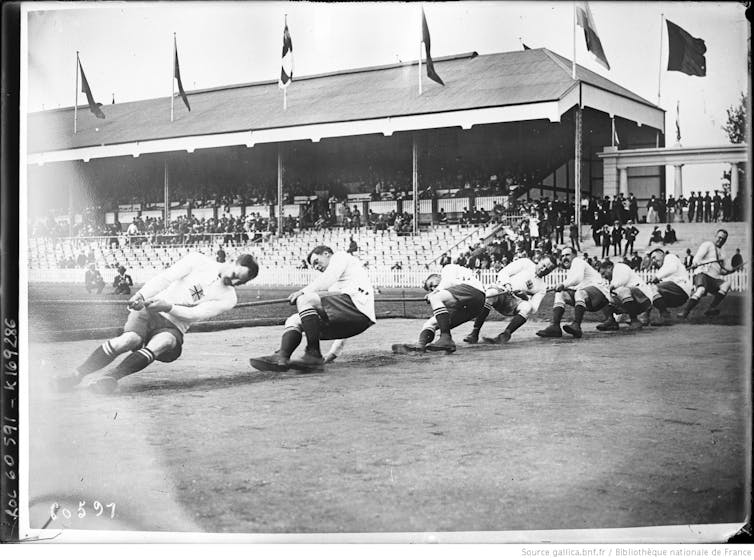

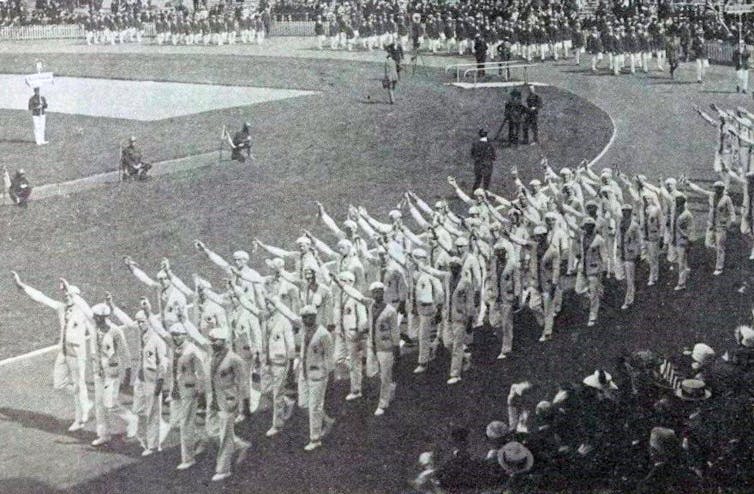

Since the global pandemic began, debate has raged over whether Tokyo should go ahead with the Olympic Games, now set to open on July 23.

The same heated debates were heard the last time an Olympic Games were staged following a global pandemic — the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) strongly believed the Olympics would help bring the world back together — not just after the devastating Spanish Flu pandemic that killed at least 50 million people, but also the tumult of the first world war.