Inbox and Environment News: Issue 502

July 18 - 24, 2021: Issue 502

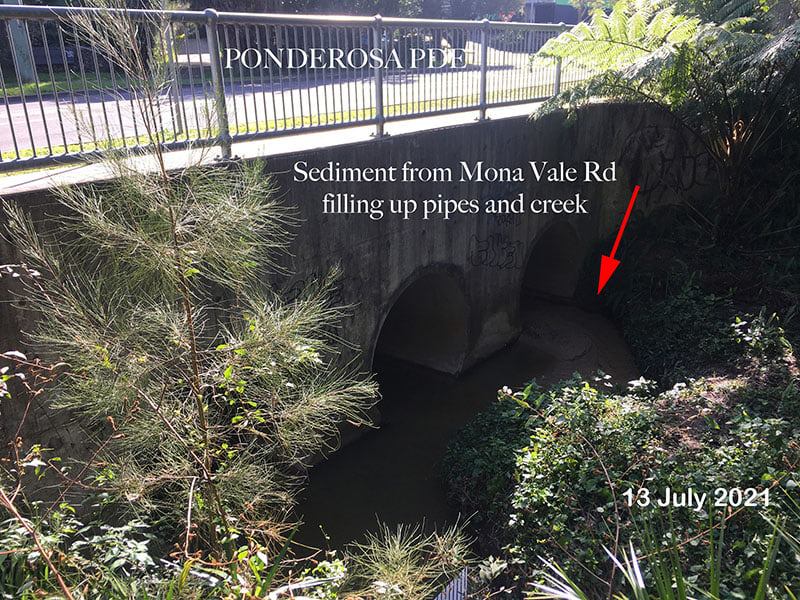

Sediment Flowing Into Warriewood Creek System Reported To EPA

More Education For Builders And Renovators Needed About The Impact Of Sediment Runoff On Sydney's Waterways

A Hidden Bias In Bubbly Flows

Air-water flows occur in a wide range of natural systems and technical applications. Flow velocities are typically measured with phase detection intrusive probes, comprising two needles which pierce bubbles and droplets. A recent study by an international team from ETH Zurich, IHE Delft and UNSW identified a significant bias in these measurements and have developed a correction scheme.

Air-water flows occur in a wide range of natural systems and technical applications. Flow velocities are typically measured with phase detection intrusive probes, comprising two needles which pierce bubbles and droplets. A recent study by an international team from ETH Zurich, IHE Delft and UNSW identified a significant bias in these measurements and have developed a correction scheme. Water Research Laboratory Successfully Co-Hosts World’s First Intermittent Estuaries Workshop

Beach Change At Turrimetta Beach, Sydney In 2020/21 - WRL Timelapse

AMA: Climate Emergency Must Not Be Ignored - Support For MP For Warringah's Zali Steggall Bill Called For

Fishers Fined For Illegal Rock Lobster Activity At Long Reef Aquatic Reserve

Wombat Displaced By Development Found In Oran Park Garage

More Time To Have Your Say On Ingleside Housing Development Proposal

Echidna Breeding Season Commences

Coastal Ecosystems Worldwide: Billion-Dollar Carbon Reservoirs

Coastal Wetlands Are Nature's Flood Defences; Especially Those Placed In Estuaries

Coastal wetlands -- such as salt marshes -- provide even more flood protection than previously thought, reducing the risk to lives and homes in estuaries, a new study has revealed. The researchers' simulations showed that wetlands that grow in estuaries, such as salt marshes, can reduce water levels by up to 2 metres and provide protection far inland up estuary channels.

Coastal wetlands -- such as salt marshes -- provide even more flood protection than previously thought, reducing the risk to lives and homes in estuaries, a new study has revealed. The researchers' simulations showed that wetlands that grow in estuaries, such as salt marshes, can reduce water levels by up to 2 metres and provide protection far inland up estuary channels.- Reduced flooding across all eight estuaries in the study

- Lowered storm water levels by as much as 2 metres in upstream areas

- Made the biggest difference when faced with the most powerful storms -- reducing average flood extents by 35% and damages caused by 37% ($8.4M).

Ramsar Treaty Offers Solid Ground For More Wetland Protections

A 50-year-old treaty could hold the key to better protecting our wetland ecosystems, while offering scientists a "how-to guide" for turning their research into action, according to an expert from The Australian National University (ANU).

A 50-year-old treaty could hold the key to better protecting our wetland ecosystems, while offering scientists a "how-to guide" for turning their research into action, according to an expert from The Australian National University (ANU).Every Spot Of Green Space Counts

When A Single Tree Makes A Difference: New Research Shows Individual Trees In Urban Areas Provide Cooling

A magnificent Grey Gum (E. punctata) example on the hill heading down Riviera Avenue, Avalon Beach, with a Spotted Gum (Eucalyptus maculata) grpwing alongside it.

Digital Mapping Of EPIs To Replace PDF Maps

- Enhance and integrate the ePlanning Spatial Viewer with the Online Planning Proposal (PP Online) Service on the NSW Planning Portal. This will enable EPI spatial data to be collected through the Planning Proposal service then presented digitally through the various stages of the plan-making process (agency consultation, public exhibition, post-gazettal). This was completed in May 2021.

- Work with an initial group of councils to ensure the solution meets the needs of stakeholders.

- Roll out to the remaining councils across NSW. This is planned to commence in the second half of 2021.

- Provide cost and time savings for all stakeholders

- Availability of GIS data to support evidence-based decision-making across the entire Planning Proposal process and multiple jurisdictions.

- Enable users to conduct more self-service transactions online, which will be cheaper and faster, reducing errors and the need for rework.

- Provide users with access to better, easier-to-find digital EPI maps with fewer errors.

- Enable users to get a better understanding of development opportunities and constraints.

- Better manage citizens’ demand for planning information, by enabling private providers to create new information services (e.g. third-party property intelligence tools and mapping platforms).

Draft National Recovery Plan For The Koala (Combined Populations Of Queensland, New South Wales And The Australian Capital Territory)

Federal Consultation On Endangered Listing For The Koala Now Open - Closes July 30, 2021

Koala Listing Strengthens Call For An Independent Environmental Compliance Agency

Gas-Fired Recovery Measures: Have Your Say - Closes August 2nd

- unlock supply

- deliver an efficient pipeline and transportation network

- empower gas customers.

- the National Gas Infrastructure Plan (NGIP)

- the Future Gas Infrastructure Investment Framework.

ARENA CEO And Board Update

Survey Finds Encouraging Platypus Numbers On Kangaroo Island

Banishing Fishing Bandits: Other Countries Bear The Cost

.jpg?timestamp=1626289454565)

Repeating mistakes: why the plan to protect the world’s wildlife falls short

It’s no secret the world’s wildlife is in dire straits. New data shows a heatwave in the Pacific Northwest killed more than 1 billion sea creatures in June, while Australia’s devastating bushfires of 2019-2020 killed or displaced 3 billion animals. Indeed, 1 million species face extinction worldwide.

These numbers are overwhelming, but a serious global commitment can help reverse current tragic rates of biodiversity loss.

This week the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity released a draft of its newest ten-year global plan. Often considered to be the Paris Agreement of biodiversity, the new plan aims to galvanise planetary scale action to achieve a world “living in harmony with nature” by 2050.

But if the plan goes ahead in its current form, it will fall short in safeguarding the wonder of our natural world. This is primarily because it doesn’t legally bind nations to it, risking the same mistakes made by the last ten-year plan, which didn’t stop biodiversity decline.

A Lack Of Binding Obligations

The Convention on Biological Diversity is a significant global agreement and almost all countries are parties to it. This includes Australia, which holds the unwanted record for the greatest number of mammal extinctions since European colonisation.

However, the convention is plagued by the lack of binding obligations. Self-reporting to the convention secretariat is the only thing the convention makes countries do under international law.

All other, otherwise sensible, provisions of the convention are limited by a series of get-out-of-jail clauses. Countries are only required to implement provisions “subject to national legislation” or “as far as possible and as appropriate”.

The convention has used non-binding targets since 2000 in its attempt to address global biodiversity loss. But this has not worked.

The ten-year term of the previous targets, the Aichi Targets, came to an end in 2020, and included halving habitat loss and preventing extinction. But these, alongside most other Aichi targets, were not met.

In the new draft targets, extinction is no longer specifically named — perhaps relegated to the too hard basket. Pollution appears again in the new targets, and now includes a specific mention of eliminating plastic pollution.

Is This Really A Paris-Style Agreement?

I wish. Calling the plan a Paris-style agreement suggests it has legal weight, when it doesn’t.

The fundamental difference between the biodiversity plan and the Paris Agreement is that binding commitments are a key component of the Paris Agreement. This is because the Paris Agreement is the successor of the legally binding Kyoto Protocol.

The final Paris Agreement legally compels countries to state how much they will reduce their emissions by. Nations are then expected to commit to increasingly ambitious reductions every five years.

Read more: Raze paradise to put in a biofuel crop? No, there are far better ways to tackle climate change

If they don’t fulfil these commitments, countries could be in breach of international law. This risks damage to countries’ reputation and international standing.

The door remains open for some form of binding commitment to emerge from the biodiversity convention. But negotiations to date have included almost no mention of this being a potential outcome.

So What Else Needs To Change?

Alongside binding agreements, there are many other aspects of the convention’s plan that must change. Here are three:

First, we need truly transformative measures to tackle the underlying economic and social causes of biodiversity loss.

The plan’s first eight targets are directed at minimising the threats to biodiversity, such as the harvesting and trade of wild species, area-based conservation, climate change and pollution.

While this is important, the plan also needs to call out and tackle dominant worldviews which equate continuous economic growth with human well-being. The first eight targets cannot realistically be met unless we address the economic causes driving these threats: materialism, unsustainable production and over-consumption.

Read more: 'Revolutionary change' needed to stop unprecedented global extinction crisis

Second, the plan needs to put Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, science, governance, rights and voices front and centre.

An abundance of evidence shows lands managed by Indigenous and local communities have significantly better biodiversity outcomes. But biodiversity on Indigenous lands is decreasing and with it the knowledge for continued sustainable management of these ecosystems.

Indigenous peoples and local communities have “observer status” within the convention’s discussions, but references to Indigenous “knowledges” and “participation” in the draft plan don’t go much further than in the Aichi Targets.

Third, there must be cross-scale collaborations as global economic, social and environmental systems are connected like never before.

The unprecedented movement of people and goods and the exchange of money, information and resources means actions in one part of the globe can have significant biodiversity impacts in faraway lands. The draft framework does not sufficiently appreciate this.

For example, global demand for palm oil contributes to deforestation of orangutan habitat in Borneo. At the same time, consumer awareness and social media campaigns in countries far from palm plantations enable distant people to help make a positive difference.

The Road To Kunming

The next round of preliminary negotiations of the draft framework will take place virtually from August 23 to September 3 2021. And it’s likely final in-person negotiations in Kunming, China will be postponed until 2022.

It’s not all bad news, there is still much to commend in the convention’s current draft plan.

For example, the plan facilitates connections with other global processes, such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. It recognises the contributions of biodiversity to, for instance, nutrition and food security, echoing Sustainable Development Goal 2 of “zero hunger”.

The plan also embraces more inclusive language, such as a shift from saying “ecosystem services” to “Nature’s Contribution to People” when discussing nature’s multiple values.

Read more: 'Existential threat to our survival': see the 19 Australian ecosystems already collapsing

But if non-binding targets didn’t work in the past, then why does the convention think this time will be any different?

A further set of unmet biodiversity goals and targets in 2030 is an unacceptable scenario. At the same time, there’s no point aiming at targets that merely maintain the status quo.

We can change the current path of mass extinction. This requires urgent, concerted and transformative action towards a thriving planet for people and nature.![]()

Michelle Lim, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Stopping Illegal Trade Of Australian Lizards

Raze paradise to put in a biofuel crop? No, there are far better ways to tackle climate change

We all know action on climate change is urgently needed. But that doesn’t mean a forest should be razed to build a wind farm. Nor should vast fields of a single crop be grown year after year – reducing the number of other species that can live there – even if the plant is used to produce renewable bio-fuel.

Climate change and biodiversity loss are the two greatest challenges to humanity and our planet. But they’re often dealt with by separate laws and policies, which can lead to perverse, unwanted outcomes.

Clearly, this siloed approach must change. This was recognised in a draft plan by the Convention on Biological Diversity, released overnight, which stated that biodiversity should not be harmed by efforts to tackle climate change.

But how do we ensure solutions to one of these wicked problems does not worsen the other? Some 50 of the world’s leading researchers on biodiversity and climate have released a report which sought to answer this question. Below, I outline the conundrums we tackled and the solutions we came up with.

A World-First Collaboration

Our report, released last month, represents the first ever collaboration between the world’s largest research and policy communities on biodiversity and climate – the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

IPBES is an independent intergovernmental body that synthesises evidence on the state of biodiversity, ecosystems and natures’ contributions to people. The IPCC is the United Nations body for assessing climate science.

The word “biodiversity” refers to the variety of living things: all the animals, plants and tiny micro-organisms on Earth, including the genetic information they contain and the ecosystems they form.

Biodiversity loss, then, is a reduction in the variety of species in an ecosystem, a geographic area or the planet as a whole. Biodiversity, including extinctions, is currently declining at rates unprecedented in human history.

There’s a growing recognition that climate, biodiversity and human well-being are inextricably linked.

To date, biodiversity loss has largely been caused by human actions which harm land, rivers and oceans. However, research suggests worsening climate change will be the main cause of global biodiversity loss this century.

For example, climate change is causing marine heatwaves which threaten the existence of the Great Barrier Reef. Climate change also makes bushfires more intense and frequent, pushing species closer to extinction.

Biodiversity loss can also make climate change worse. For example, forests store large amounts of carbon, and their destruction is a key source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Robbing Peter To Pay Paul

Bioenergy crops such as corn, canola and soybeans can be processed and used as a fuel for heat or energy. This can provide an alternative energy source to fossil fuels. And forest plantations storing carbon dioxide can be an effective way to reduce atmospheric carbon levels.

But these climate solutions can be bad for nature. Crop or forest monocultures greatly diminish the diversity of other plant and animal species the land can support. Such practices can also degrade ecosystems and damage native species.

Similarly, renewable energy technologies can harm biodiversity. For example, large-scale solar plants across vast areas of land can destroy animal habitat and disrupt wildlife movement.

Crucially, climate and biodiversity interventions can also be harmful to human well-being. Many communities in developing countries rely directly on nature for their everyday needs. Efforts to protect biodiversity by locking up natural areas in forest reserves can deprive local people of their lands and erode their food security.

What Must Be Done?

Our report sets out key steps to protecting the climate, biodiversity and human well-being in unison. I outline these below.

Protect and restore carbon-rich ecosystems

This is the number one priority for joint action on climate and biodiversity. It is critical, however, that such processes involve – and consider the needs of – local communities. They must also take future climate conditions into account.

Slash carbon emissions

By storing carbon in forests, wetlands and other ecosystems, nature can do a lot to tackle climate change. But it can’t do everything. Ambitious reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are needed across multiple sectors of the global economy. Without this, it will be virtually impossible to restore and protect natural ecosystems.

Increase sustainable agricultural and forestry practices

Food systems contribute up to one-third of total human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. The agricultural sector must urgently reduce waste. And if humans, particularly those in rich countries, eat less meat this will also help address emissions and biodiversity loss. In the forestry sector, careful species selection and management can mitigate climate while being good for biodiversity.

Eliminate harmful subsidies

Government subsidies for activities that harm the environment, such as burning fossil fuels, should be removed.

Delivering A Revolution

The above measures will not be easily achieved. And they are each contingent on revolutionary economic and societal shifts.

Unsustainable consumption and production are key causes of climate change and biodiversity loss. Our report calls for a shift in individual and societal values away from materialism. We must also challenge the dominant worldview which equates continuous economic growth with human well-being.

Justice and equity must be at the centre of our new ways of being. Indigenous and local communities should lead the stewardship of forest, lands and seas. And system-wide change should not disproportionately impact the already disadvantaged.

And all this will require coordinated action at local, national and global scales. This must integrate multiple knowledge systems and worldviews.

A bright future for people and nature is possible. But achieving win-wins across climate, biodiversity and society requires urgent, transformative and just action which addresses not only the symptoms, but the causes of our greatest problems.

Michelle Lim, Senior Lecturer, Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Are the Nationals now the party for mining, not farming? If so, Barnaby Joyce must tread carefully

The return of Barnaby Joyce to the federal National Party’s top job has highlighted tensions within, and dilemmas for, the broader party – particularly on climate change policy and coal.

Joyce and some of his Queensland colleagues unashamedly support the coal industry, and the federal party appears broadly opposed to Australia adopting a target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

These are positions at odds with progressive quarters of the party, particularly in Victoria. The divisions came to a head earlier this month when, in response to Joyce’s ascension, Victorian Nationals leader Peter Walsh and deputy Steph Ryan sought to split the state party from its federal counterpart.

The move was unsuccessful. But Walsh later called for the party to have “a constructive discussion about the transition of our energy supplies and how we reduce our impact on the Earth we live on”.

So are the federal Nationals the latter-day party for mining, not farming? If so, what does this mean for the party’s political positioning and prospects? To address this question, we must examine the Nationals’ evolution over the past century.

Coal As Nation-Builder

The National Party began federally in 1920 as the Australian Country Party, and traditionally represented farmers and rural communities. But over time, the party evolved to represent and advocate for the broader interests of regional Australia.

Economic nationalism has underpinned the party, especially since the 1950s. Under this ethos, farming, mining and basic manufacturing were considered key foundations for nation-building – a view which persists today. As the Nationals’ Senator Matt Canavan wrote in an opinion piece last month:

The restoration of Barnaby Joyce as deputy prime minister restores a strong advocate for the economically nationalist, Australia-first approach that has always served us well.

Most Nationals candidates come from rural small businesses, finance organisations and social and community services – though many have farming roots or some involvement in farming activities.

Rural communities are under pressure from dwindling populations and limited employment opportunities. In that sense, the mining industry is an important source of jobs and economic activity in Australia’s regions.

Read more: Net zero by 2050? Even if Scott Morrison gets the Nationals on board, hold the applause

The federal party’s vociferous support for mining and opposition to emissions reduction is, in part, values signalling. For many in the Nationals, coal helped build the nation, while climate change action and renewable energy represent a moral and material threat.

Regional differences also exist. Nationals’ support for mining is particularly strong in Queensland – traditionally a mining-dependent state where resource investment has long been considered a means of rural development. At both the Queensland and federal levels, strong political connections exist between mining companies and the Liberal-National Party.

In another sign of the federal party’s contemporary priorities, Joyce’s close party ally Matt Canavan recently told the Guardian:

About 5% of our voters are farmers. It’s about 2% of the overall population. So 95% of our voters don’t farm, aren’t farmers or don’t own farmland.

The Nationals’ apparent support for mining above farming exists partly because because they can get away with it. In many regions, farming and mining co-exist in reasonable harmony, both sectors enjoying the benefits of strong regional centres.

In some cases conflict does arise, such as with gas exploration in cropping country. But in those regions, disenfranchised Nationals voters typically direct their votes to micro-parties rather than Labor or the Greens. These votes often flow back to the Nationals via preferences.

A Questionable Strategy

The federal Nationals’ pro-mining, anti-renewables stance may not, however, benefit the party over the long term.

First, mining is at best a very patchy contributor to rural development. Overall, net employment in agriculture is still higher than for mining and is more evenly distributed across the regions. Mining investment can ebb and flow quickly with commodity prices and the stage of project development, leaving communities with falling real estate values and an altered social fabric.

The anti-emissions control stance could also trigger conflict with major farm organisations. Many, such as the National Farmers Federation and Meat and Livestock Association, want to see a strong national emissions reduction plan, under which landowners can benefit financially by participating in land carbon schemes.

Many farmers are also interested in renewable energy as both a source of income and cheaper power. Renewables projects are proliferating in regional areas and even Joyce has been known to turn up in a hard hat to get behind them. So we can look forward to some interesting management of that cognitive dissonance.

Read more: Renewables need land – and lots of it. That poses tricky questions for regional Australia

Trouble Ahead

Following Joyce’s return to the federal party leadership, Victorian Nationals leader Peter Walsh said he’s had “a very frank discussion with him about the policy differences on climate change”.

But discontent on climate policy is not confined to Victoria. Across the party, Young Nationals organisations are generally far more open to climate action than their older party colleagues.

And the hardline mining stance will not help the Nationals regain or even retain seats in areas such as Ballina in NSW, where demographic changes have eroded the party’s support.

But the biggest test of the Nationals’ farming-vs-mining rift is perhaps yet to come. The European Union and other jurisdictions are considering imposing tariffs on goods – including agricultural products – from nations such as Australia which lack strong emissions reduction policies.

While helping drive global climate action, such moves would partly be motivated by economic nationalism - boosting the international competitiveness of industries in the country/s applying the tariff. The sight of the Nationals impotently arguing for free trade in this instance will be fascinating political theatre.

Read more: No point complaining about it, Australia will face carbon levies unless it changes course ![]()

Geoff Cockfield, Professor of Government and Economics, and Deputy Dean, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Environmental accounting’ could revolutionise nature conservation, but Australia has squandered its potential

Let’s say a new irrigation scheme is proposed and all the land it’ll take up needs to be cleared — trees felled, soil upturned, and habitats destroyed. Water will also have to be allocated. Would the economic gain of the scheme outweigh the damage to the environment?

This is the kind of question so-called “land accounts” grapple with. Land accounts are a type of “environmental account”, which measures our interactions with the environment by recording them as transactions. They help us understand the environmental and economic outcomes of land use decisions.

Environmental accounting, for which Australia has a national strategy, seeks to integrate environmental and economic data to ensure sustainable decision making. Last month, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the country’s first national land account under the strategy, describing it as “experimental”.

Environmental accounting could be a game changer for conserving nature, but the account released by the ABS falls flat. It’s yet another example of Australia’s environmental policy culture: we develop or adopt good ideas, but then just tinker with them, or even discard them.

A (Really) Long Time Coming

Environmental accounting has been a long time coming and dates back to the 1980s. It’s closely related to sustainable development, and in fact, the two ideas developed in parallel.

In 1992, the Rio Earth Summit endorsed both, and nations agreed to develop an international system of environmental accounting.

But it took the UN 20 years to endorse the System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) — the rules for developing accounts — as an international statistical standard. This endorsement means they’re authoritative and compatible with national accounts.

Then, in March this year, the international standard was finally extended to cover ecosystem accounting.

So, how are environmental accounts used?

“National accounts” are a way to measure the economic activity of Australia and they tell us our gross domestic product (GDP). Linking existing national accounts to environmental accounts means important decisions can capture environmental and economic outcomes, obviously making for better decisions.

For example, the case for orienting a stimulus package towards investing in renewable energy and land restoration will be much stronger if it can quantify not only economic benefits, but gains to natural assets, such as through revegetation.

Stuck In ‘Experimental’ Mode

Australia, through the ABS, was an early mover in developing environmental accounting. It has produced experimental accounts since the mid-1990s.

Some countries are now taking significant steps to produce and apply accounts. And a communiqué issued by the G7 in May endorses the UN’s SEEA and encourages making nature a regular part of all decision-making – in other words, “mainstreaming nature”. This is something for which SEEA is ideal.

Read more: You probably missed the latest national environmental-economic accounts – but why?

It’s no accident this communiqué emerged from London. The UK is a leader in the field of applying accounting to environmental and economic management. It had a Natural Capital Committee for some years and its 25-year environmental plan provides for further account development, including for urban areas, fisheries and forestry.

Australian governments, on the other hand, have been slow to use environmental accounts. They took until 2018 to agree on an unambitious national strategy, which specified “intermediate” outcomes, only to 2023.

These targets include such policy basics as making environmental information for accounts “findable” and “accessible”. This is not far removed from what federal and state governments first signed up to in an agreement 30 years ago.

And the strategy places the holy grail of policy integration “into the future” beyond 2023 — for example, off into the never-never. As a result, we are on a slow track and seemingly stuck in “experimental” mode.

So, What’s The Problem With The New Land Account?

The new land account is a very small step. While it has gathered a lot of information in one place, it tells us little, and essentially repackages old information (the newest data is for 2016).

It’s also in a format that cannot be integrated with national accounts, or even with other environmental accounts so far produced in Australia, such as those covering waste, water, energy and greenhouse gas emissions.

Integration of environmental and economic information is the raison d'etre for the international system. So how did this happen?

For accounts produced outside the ABS (such as for greenhouse gas emissions), different accounting frameworks were used, so this is understandable, though unfortunate. For the land accounts, it is less understandable and we can only speculate.

Not being able to integrate the land, water and national accounts means the environmental-economic trade-offs cannot be assessed. It seems the government is struggling to integrate an exercise of integration!

Governments Fiddle While The Planet Burns

Australia’s 2021 intergenerational report, released last month, shows how far we are from producing good environmental information.

The environment section of the report acknowledges climate change and biodiversity loss as major problems, and the need to account for and maintain natural capital. But it goes on to do little more than make general observations and recite standard government talking points about existing policies.

Read more: Intergenerational reports ought to do more than scare us — they ought to spark action

If the report was informed by comprehensive environmental accounts, it could support the modelling of environmental trends going forward. This would give us a real sense of likely changes to natural capital and its impact on the economy.

But there are no plans for such an approach. In fact, this kind of “high potential, low ambition” approach to environmental policy is something of a trademark for this government. Another example is the recent cherry picking of recommendations from an independent review of Australia’s environment law.

While such an approach may deliver a successful political placebo, it is a formula for policy failure.

Just how loud will the wake-up call have to be? Recently, a climate-change-induced “heat dome” hit western North America. Lytton, Canada, which is closer to the North Pole than the equator, shattered temperature records with a staggering 49.6℃, before being decimated by wildfire.

If only such disasters, including our own Black Summer, would raise policy ambition more than the temperature.

Peter Burnett, Honorary Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, Australian National University and Michael Vardon, Associate Professor at the Fenner School, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW State Government's Plans To Open Western NSW To Coal Mining Open For Feedback

- Forty-five recorded Aboriginal heritage sites and an additional 13 sites that are restricted and location data not supplied in the proposed coal release areas.

- Twenty-two threatened fauna species and six threatened flora species including the koala, the critically endangered regent honeyeater and the endangered spotted-tailed quoll, as well as four plant species endemic to the Rylstone/western Wollemi area.

- One thousand, eight hundred and fifty-four hectares of groundwater dependant ecosystems.

- Six thousand, six hundred and thirty-four hectares of potential threatened ecological communities.

- Thirty-six water bores.

- One hundred and twenty kilometres of stream channels in good condition and 118 kilometres of stream channels classed as a high level of fragility.

New Plan To Revitalise NSW's Oldest Park By Installing Mountain Bike Trails

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park, Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Planning Considerations

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Plan of Management

- Royal National Park, Heathcote National Park and Garawarra State Conservation Area Draft Mountain Biking Plan

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

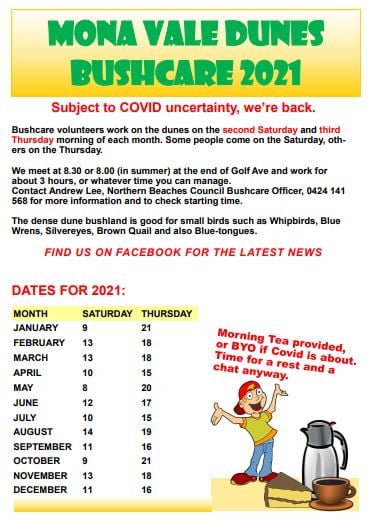

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

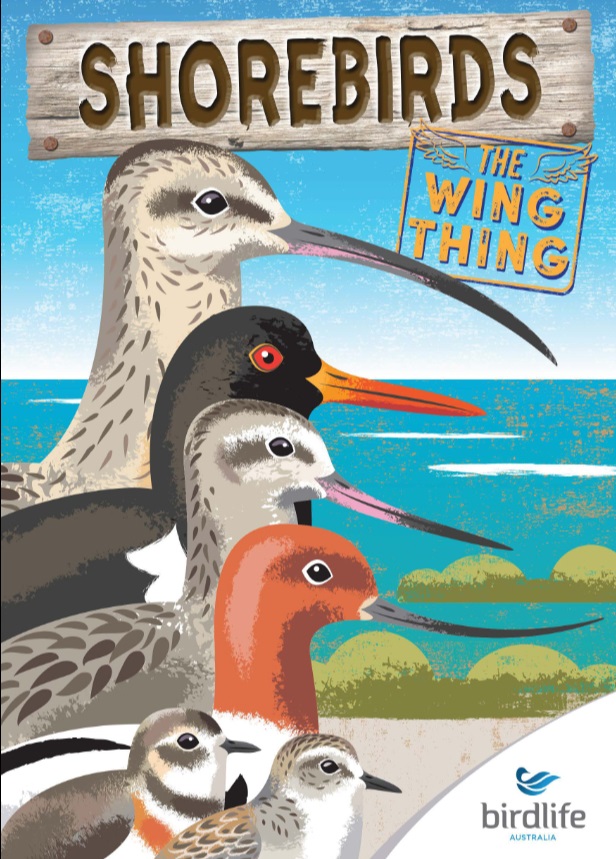

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Updated Advice For HSC Students

- Your school will advise you about arrangements for trial HSC exams.

- HSC students in Greater Sydney continue to be able to access school to prepare for the HSC where they cannot do so from home, including to use specialist equipment to work on major projects or rehearse for performance exams.

- As per broader NSW Health advice, HSC students in Greater Sydney are asked to learn from home where possible.

- All HSC students must follow COVID safe practices at school, including wearing a mask.

- The COVID illness/misadventure process is available for students whose ability to work on their major project or performance has been significantly impacted by COVID-19 restrictions.

After Dark Photo Competition: Northern Beaches

The Northern Beaches are one of the best places in Sydney to view the night sky and appreciate this wonderful asset.

The Northern Beaches are one of the best places in Sydney to view the night sky and appreciate this wonderful asset.Details

- Land – manmade and/or natural formations, wildlife, flora or fauna

- Sea – waterways, beaches, or marine areas, sea life

- Sky – aspects of the night sky, moon, starscapes, clouds or wildlife

- Junior – under 16 years featuring any one of these categories.

- Entry fees are $20 for the first category entered and $10 for each subsequent category entered.

- Up to six entries per category are permitted.

- Fees should be paid by the PayPal gateway on the entry website. Credit and debit cards can be used on this gateway.

- If entry payments are not received by the deadline, then the submitted entries will not be accepted for judging.

- Entries will be accepted only from Australian residents of the Commonwealth of Australia and its Territories.

- There will be two sections of entry – General and Junior (18 or younger)

- There will be three categories of entry for the General Section; Portraying the night time environment featuring Land, Sea or Sky.

- The Junior Section is for photographers 18 years old or younger and will have one open category.

- All entries must be taken within the Northern Beaches LGA and must be taken between sunset and sunrise.

- Images can be taken at any time of the year on or after 1 September 2019.

- The top 5 images of each category will be judged by the organising committee and will be hung at the Studio, Careel Bay Marina for general public display.

- Photographers represented in the top 5 images of each category will be notified that they are in the top 20 images (15 September 17:00 AEST).

- There is a limit of six (6) entries per category per photographer.

- In the case of images with multiple authors, the instigator of the image will be considered to be the principal author and the one who “owns” the image. The principal author MUST have performed the majority of the work to produce the image. All authors MUST be identified and named in the entry form along with their contributions to the production of the image.

- Entries must be in digital form and will be accepted ONLY through submission via the dedicated website at: afterdark.myphotoclub.com.au

- To preserve anonymity, the submitted image files should not contain identifying metadata.

- For judging purposes, still images must be submitted as JPG files with the longest side having a dimension no greater than 4,950 pixels in Adobe 1998 colour space.

- All photographs must have been taken no more than 2 years before the closing date of entry.

- Entry fees are $20 for the first entry and $10 each subsequent entry. Fees should be paid by the PayPal gateway on the entry website. Credit and debit cards can be used on this gateway.

- If entry payments are not received by the deadline, then the submitted entries will not be accepted for judging.

- Photographers of the top 20 images (5 in each category) will be notified 15 September and images printed, framed and hung by the organising. Artists may choose to pay $55 for this service to be undertaken on their part or undertake printing and framing at their own cost. Images must be ready for hanging 17:00 (AEST) 29 September 2021.

- Images will be listed on sale during the exhibition at the artist’s discretion. $100 of the sale will be donated to the charity the Australasian Dark Sky Alliance.

- Winners for the Land Scape, Sea Scape, Sky Scape and Youth entry will be announced Thursday 30th September 2021.

- People’s choice will confirmed by popular vote throughout the exhibition and will be announced on Saturday 30 October, 2021.

- Submissions close at 24:00 (AEST) on Wednesday, 1 September 2021. No entries will be accepted past this date.

- All winners should make an effort to attend the presentation of the awards on 30 September 2021

- The winning entries will be exhibited for the entire Exhibition After Dark, at the Studio, Careel Bay Marina between 30 September and 2 November, 2021.

- Permission to reproduce entries for publication to promote the competition and exhibitions and dark sky-related events and activities on the northern beaches will be assumed as a condition of entry. The copyright of the image remains with the author, and we will try to ensure that the author is credited where the image is used.

- All entries must be true images, faithfully reflecting and maintaining the integrity of the subject. Entries made up of composite images taken at different times and/or at different locations and/or with different cameras will not be accepted. Image manipulations that produce works that are more “digital art” than true astronomical images, will be deemed ineligible. If there is any doubt about the acceptability of an entry, then the competition organisers should be contacted, before the entry is submitted, for adjudication on the matter at the following email address: marnie@darkskytraveller.com.au

- If after the judging process, an image is subsequently determined to have violated the letter and/or the spirit of the rules, then that image will be disqualified. Any prizes consequently awarded for that image must be returned to the competition organisers.

- The competition judges reserve the right to reject any entry that, in the opinion of the judges, does not meet the conditions of entry or is unsuitable for public display. The judges’ decisions will be final.

- Submission of an entry implies acceptance of all the conditions of entry and the decisions of the competition judges.

- Entries Open: 24:00 (AEST) Sunday, 11 July 2021

- Entries Close: 24:00 (AEST) Wednesday, 1 September 2021

- Top 20 announced: 17:00 Wednesday, 15 September 2021

- Photography bump in: Midday Wednesday 29 September 2021

- Exhibition Launch and Presentation of Awards: Thursday 30 September 2021

- Bump out – 2 November 2021

- Category Winner: An image deemed to be the best in that category as judged by the judging panel.

- “The People’s Choice”: This will be judged by gathering votes obtained in the exhibition venue, and online.

- Category Winner: $200 – to each of the image deemed to be the best in each of the four (4) category.

- “The People’s Choice”: $200 – will be judged by gathering votes obtained in the exhibition venue, and online.

2021 Crikey! Magazine Photography Competition

Butcher Bird Sings Imagine In Duet With Irish Folk Singer Robbie Dunn

Enjoy The Louvre At Home; Take A Virtual Tour!

All Quiet On The Western Front

5 rocks any great Australian rock collection should have, and where to find them

Road tripping with a geologist is a little different. While you’re probably reading road signs and dodging roadkill, we’re reading road cuttings and deciphering the history of the area over the previous millions — or even billions — of years.

Geology has shaped the Australian landscape. In Victoria where I live, for example, the western plains are pockmarked by Australia’s youngest volcanoes, while the east of the state has been pushed up to form the mountains of the Great Dividing Range.

Along the southern margin of the state are fossilised braided rivers, relics of when Australia drifted away from Antarctica. Evidence of this event extends into Tasmania, where dolerite, a rock that signifies this rift, looms in enormous columns over Hobart from Mount Wellington.

This probably won’t surprise anyone who knows me, but I have rocks peppered around my house that I’ve collected on my travels. Every time I look at them, I not only think about how the rocks were formed, I’m also reminded of the trip when I collected them.

With international and even state borders set to remain closed for a while longer, this is the perfect time to take a great Australian road trip, become a rock detective, and build up your rock collection while you’re at it.

To help you get started, I’ve listed five rocks any great Australian rock collection should have.

1. Mantle Xenoliths

Western Victoria

The youngest rocks in Australia are those that erupted out of Australia’s youngest volcano in Mount Gambier, South Australia, 4,000 to 8,000 years ago. That volcano is the culmination of an enormous field of volcanoes that span central and western Victoria.

Read more: Photos from the field: the stunning crystals revealing deep secrets about Australian volcanoes

In western Victoria, the volcanoes were formed from magma that ascended from the Earth’s mantle — the layer between the Earth’s core and crust. While the magma was rising, it tore off chunks of the surrounding mantle rock and transported it to the surface. We can find these chunks of the mantle — or mantle xenoliths (xeno = foreign, lith = rock) — in cooled lava today in western Victoria.

At first, these rocks look like any other piece of black or brown basalt, but then you turn them over or crack them open and there’s a blob of bright green rock staring back at you. The mantle rock inside is comprised mainly of olivine, which is a green mineral, and some black/brown pyroxene.

Mantle xenoliths are a great place to start your rock collection because not only will they be your very own piece of Earth’s mantle, but you can find them yourself through a bit of fossicking around some of the volcanoes in western Victoria.

2. Meteorites

The Nullarbor Desert, South Australia and Western Australia

The Nullarbor is a desert plain region which straddles the border of South Australia and Western Australia.

The dry environment is ideal for preserving meteorites that fall to Earth, and the light colour of the limestone country rock and lack of vegetation means the black and brown meteorites are easier to see.

Even if you don’t have a great eye for spotting meteorites hiding in plain sight, you can do as the geologists do and use a magnet on a stick to help you. Most meteorites are iron-rich, so wandering around with a magnet hovering over the surface is a good way to pick them up.

Thousands of meteorites have been found in the Nullarbor, some up to 40,000 years old.

3. Metamorphic Rocks

Broken Hill, New South Wales

You’ve probably heard of Broken Hill because of the large silver, lead and zinc mine there. But the geological conditions that created the ore deposit around 1.7 billion years ago also made some beautiful rocks.

A visit to Broken Hill’s Albert Kersten Mining and Minerals Museum will demonstrate the vast array of unusual minerals found in the region, some of them described for the first time at this locality.

If you’re seeking your own chunk of Broken Hill’s geological history, Round Hill is the place for you. Just a short way out of the town centre, you’ll find beautiful red garnets surrounded by patches of white minerals (quartz and feldspar).

These rocks started out as sand and mud, and record the history of being buried and heated to over 700℃ deep below the Earth’s surface. This process caused the rock to start melting and created the striking stripey, garnet-rich rocks we find there today.

4. Banded Iron Formation

Western Australia

Banded iron formation is a layered sedimentary rock mainly comprised of alternating bands of chert (a sedimentary rock made of quartz) that’s often red in colour and silver to black iron oxide. It is the main host of iron ore, and can be found in several regions in Western Australia.

The Hamersley Province in the northwestern part of Western Australia has the thickest and most extensive banded iron formations in the world. They are about 2.45 to 2.78 billion years old.

Geologists believe they formed on a continental shelf, where thick continental crust extends out into the ocean and then drops away to oceanic crust.

Banded iron formation is exciting because it no longer forms on Earth today, meaning it records an ancient process that we no longer see happening.

It is thought to have formed in ancient oceans, which were starting to increase in oxygen content at the time. It records the chemical input of these oceans, as well as sediments from the continent and volcanoes on the ocean floor.

5. Dinosaur Fossils

Central and western Queensland

Oh to have been in Queensland 100 million years ago! Judging by the fossils found in parts of the state, it would have been a cornucopia of dinosaur activity.

From an unlikely duo of dinosaurs in a 98-million-year-old billabong in Winton, to fossilised evidence of a dinosaur herd at Lark Quarry, Queensland is the place to go to peer back in time to the Mesozoic Era between 252 and 66 million years ago.

And if you’re really lucky, you might even have dinosaur bones on your property, like the huge, long-necked sauropod discovered just this year on a Queensland cattle farm.

When building your Australian rock collection, remember to check first if fossicking is allowed in the area. When you find an interesting rock, your state or territory geological survey might be able to help with identifying it.

Happy hunting!

Read more: How to hunt fossils responsibly: 5 tips from a professional palaeontologist ![]()

Emily Finch, Beamline Scientist at ANSTO, and Research Affiliate, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

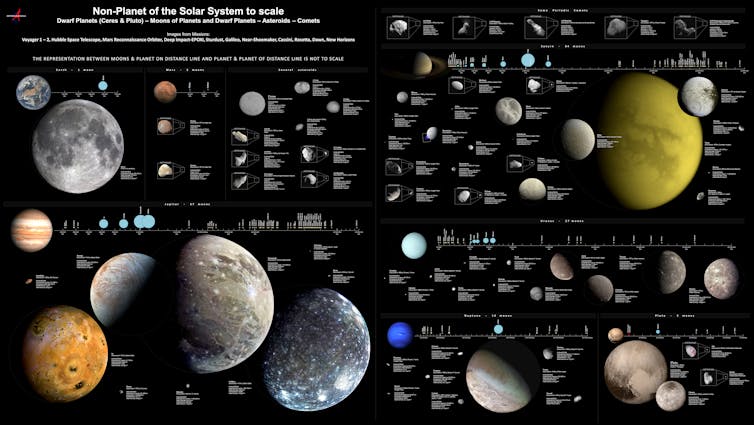

I’ve always wondered: why are the stars, planets and moons round, when comets and asteroids aren’t?

I’m puzzled as to why the planets, stars and moons are all round (when) other large and small objects such as asteroids and meteorites are irregular shapes?

— Lionel Young, age 74, Launceston, Tasmania

This is a fantastic question Lionel, and a really good observation!

When we look out at the Solar System, we see objects of all sizes — from tiny grains of dust, to giant planets and the Sun. A common theme among those objects is the big ones are (more or less) round, while the small ones are irregular. But why?

Gravity: The Key To Making Big Things Round …

The answer to why the bigger objects are round boils down to the influence of gravity. An object’s gravitational pull will always point towards the centre of its mass. The bigger something is, the more massive it is, and the larger its gravitational pull.

For solid objects, that force is opposed by the strength of the object itself. For instance, the downward force you experience due to Earth’s gravity doesn’t pull you into the centre of the Earth. That’s because the ground pushes back up at you; it has too much strength to let you sink through it.

However, Earth’s strength has limits. Think of a great mountain, such as Mount Everest, getting larger and larger as the planet’s plates push together. As Everest gets taller, its weight increases to the point at which it begins to sink. The extra weight will push the mountain down into Earth’s mantle, limiting how tall it can become.

If Earth were made entirely from ocean, Mount Everest would just sink down all the way to Earth’s centre (displacing any water it passed through). Any areas where the water was unusually high would sink, pulled down by Earth’s gravity. Areas where the water was unusually low would be filled up by water displaced from elsewhere, with the result that this imaginary ocean Earth would become perfectly spherical.

But the thing is, gravity is actually surprisingly weak. An object must be really big before it can exert a strong enough gravitational pull to overcome the strength of the material from which it’s made. Smaller solid objects (metres or kilometres in diameter) therefore have gravitational pulls that are too weak to pull them into a spherical shape.

This, incidentally, is why you don’t have to worry about collapsing into a spherical shape under your own gravitational pull — your body is far too strong for the tiny gravitational pull it exerts to do that.

Read more: Curious Kids: how and when did Mount Everest become the tallest mountain? And will it remain so?

Reaching Hydrostatic Equilibrium

When an object is big enough that gravity wins — overcoming the strength of the material from which the object is made — it will tend to pull all the object’s material into a spherical shape. Bits of the object that are too high will be pulled down, displacing material beneath them, which will cause areas that are too low to push outward.

When that spherical shape is reached, we say the object is in “hydrostatic equilibrium”. But how massive must an object be to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium? That depends on what it’s made of. An object made of just liquid water would manage it really easily, as it would essentially have no strength — as water’s molecules move around quite easily.

Meanwhile, an object made of of pure iron would need to be much more massive for its gravity to overcome the inherent strength of the iron. In the Solar System, the threshold diameter required for an icy object to become spherical is at least 400 kilometres — and for objects made primarily of stronger material, the threshold is even larger.

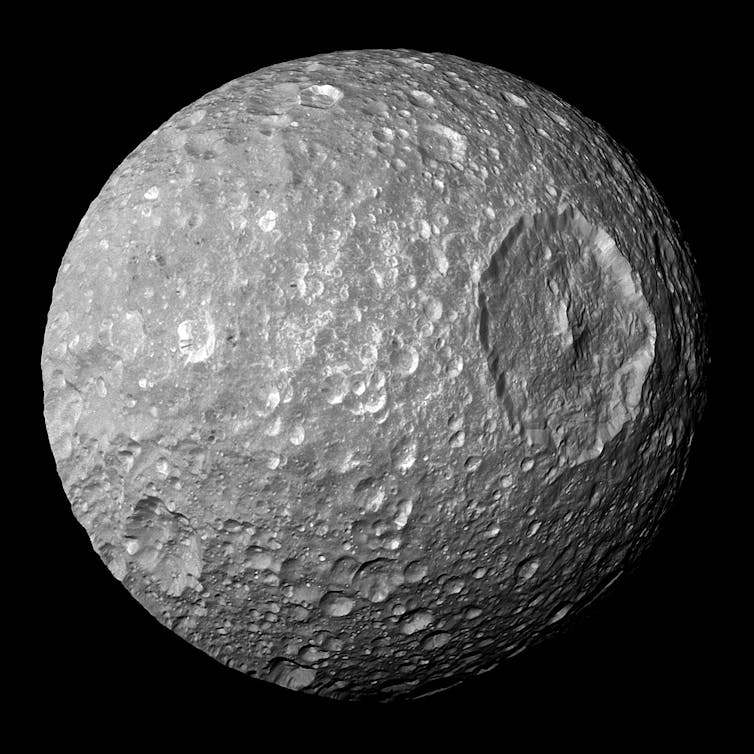

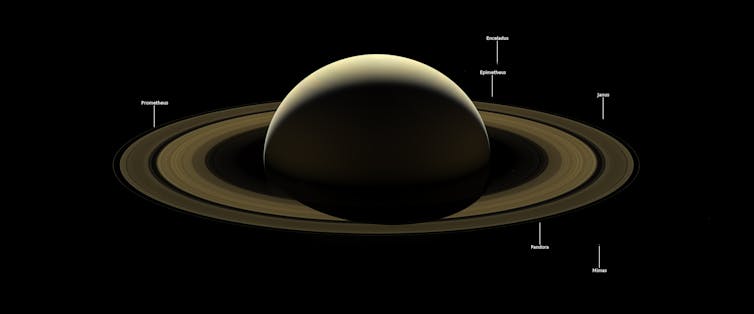

Saturn’s moon Mimas, which looks like the Death Star, is spherical and has a diameter of 396km. It’s currently the smallest object we know of that may meet the criterion.

Constantly In Motion

But things get more complicated when you think about the fact that all objects tend to spin or tumble through space. If an object is spinning, locations at its equator (the point halfway between the two poles) effectively feel a slightly reduced gravitational pull compared to locations near the pole.

Read more: Even planets have their (size) limits

The result of this is the perfectly spherical shape you’d expect in hydrostatic equilibrium is shifted to what we call an “oblate spheroid” — where the object is wider at its equator than its poles. This is true for our spinning Earth, which has an equatorial diameter of 12,756km and a pole-to-pole diameter of 12,712km.

The faster an object in space spins, the more dramatic this effect is. Saturn, which is less dense than water, spins on its axis every ten and a half hours (compared with Earth’s slower 24-hour cycle). As a result, it is much less spherical than Earth.

Saturn’s equatorial diameter is just above 120,500km — while its polar diameter is just over 108,600km. That’s a difference of almost 12,000km!

Some stars are even more extreme. The bright star Altair, visible in the northern sky from Australia in winter months, is one such oddity. It spins once every nine hours or so. That’s so fast that its equatorial diameter is 25% larger than the distance between its poles!

The Short Answer

The closer you look into a question like this, the more you learn. But to answer it simply, the reason big astronomical objects are spherical (or nearly spherical) is because they’re massive enough that their gravitational pull can overcome the strength of the material they’re made from.

This is an article from I’ve Always Wondered, a series where readers send in questions they’d like an expert to answer. Send your question to alwayswondered@theconversation.edu.au![]()

Jonti Horner, Professor (Astrophysics), University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why we need engineers who study ethics as much as maths

S. Travis Waller, UNSW; Kourosh Kayvani, UNSW; Lucy Marshall, UNSW, and Robert F. Care AM, UNSWThe recent apartment building collapse in Miami, Florida, is a tragic reminder of the huge impacts engineering can have on our lives. Disasters such as this force engineers to reflect on their practice and perhaps fundamentally change their approach. Specifically, we should give much greater weight to ethics when training engineers.

Engineers work in a vast range of fields that pose ethical concerns. These include artificial intelligence, data privacy, building construction, public health, and activity on shared environments (including Indigenous communities). The decisions engineers make, if not fully thought through, can have unintended consequences – including building failures and climate change.

Read more: Why did the Miami apartment building collapse? And are others in danger?

Engineers have ethical obligations (such as Engineers Australia’s code of ethics) that they must follow. However, as identified at UNSW, the complexity of emerging social concerns creates a need for engineers’ education to equip them with much deeper ethical skill sets.

Engineering is seen as a trusted and ethical profession. In a 2019 Gallup poll, 66% rated the honesty and ethical standards of engineers as high/very high, on a par with medical doctors (65%).

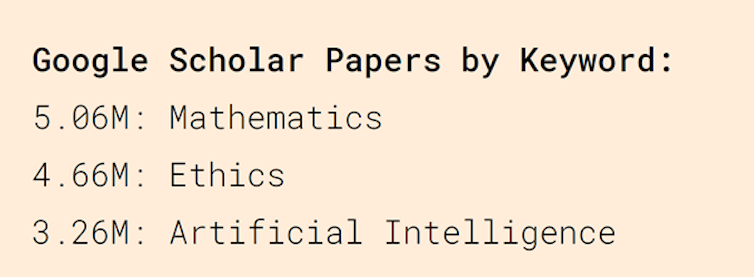

However, ethics as a body of knowledge is massive. There are nearly as many academic papers on ethics as mathematics, and clearly more than on artificial intelligence.

With such a rich backdrop of knowledge, engineers must embrace ethics in a way that previous generations embraced mathematics. Complex societal problems make much greater demands on engineering thinking than in the past. We need to consider whole and complex systems, not just issues as individual challenges.

Ethics And The Construction Industry

The construction industry provides a topical example of such complexity. Opal Tower in Sydney, Lacrosse building in Melbourne, Grenfell Tower in London and Torch Tower in Dubai became household names for all the wrong reasons.

Importantly, these issues of poor quality and performance don’t arise from new technology or know-how. They involve well-established technical domains of engineering: combustible cladding, fire safety, structural adequacy and so on. A fragmented design and delivery process with unclear responsibility and/or accountability has led to poor outcomes.

These issues prompted the Australian Building Ministers’ Forum to commission the Shergold Weir Report, followed by a task force to implement its recommendations across Australia.

There are real shortcomings in the legal and contractual processes for allocating and “commoditising” risk in the industry. However, ethics should do the heavy lifting when legal frameworks are lacking. One key question is whether erosion of professional ethics has played a part in this state of affairs. The answer is a likely “yes”.

Engineers face ethical dilemmas such as:

“Should I accept a narrow or inadequately framed design commission within a design and build delivery model when there is no certainty my design will be appropriately integrated with other parts of the project?”

“How can I accept a commission when my client provides no budget for my oversight of the construction to ensure the technical integrity of my design is maintained when built?”

“How do I play in a commercially competitive landscape with pressures to produce "leaner” designs to save cost without compromising safety and long-term performance of my design?“

"Do I hide behind the contractual clauses (or minimum requirements of codes of practice) when I know the overall process is flawed and does not deliver quality and/or value for money for the end user?”

Or worse: “Do I resort to phoenixing to avoid any accountability?”

Read more: Lacrosse fire ruling sends shudders through building industry consultants and governments

Engineering On Country

The enduring connection of Aboriginal Australians to Country requires engineers to navigate ethical considerations in Indigenous communities. Engineers must reconcile the legal, technical and regulatory requirements of their projects with Indigenous cultural values and needs. They might not be properly equipped to navigate ethical scenarios when they encounter unfamiliar cultural connections, or regulations are insufficient.

Consider, for example, the sacred sites of the McArthur River Mine. Traditional owners have raised concerns that current mining activities do not adequately protect sacred and cultural heritage sites. Evidence given by community leaders provides insight into the intimate and diverse relationship that traditional owners have with the land.

In considering such evidence, engineers must be able to evaluate both physical site risks (such as acidification of mine tailings and contamination of water bodies) and cultural risks (such as failing to identify all locations of cultural value).

How might we tackle such complicated projects? By properly engaging with traditional communities and by having diverse teams with multiple worldviews and experiences, along with strong technical skills. The broad field of ethical knowledge provides the skill sets to attempt to reconcile the diverse considerations.

Read more: Juukan Gorge inquiry puts Rio Tinto on notice, but without drastic reforms, it could happen again

What Should The Curriculum Look Like?

Engineering students’ ethical development requires a holistic approach. One assessment suggested:

“[…] that institutions integrate ethics instruction throughout the formal curriculum, support use of varied approaches that foster high‐quality experiences, and leverage both influences of co‐curricular experiences and students’ desires to engage in positive ethical behaviours.”

The curriculum should include:

skills/expertise – the underlying intellectual basis for discerning what is ethical and what is not, which is much more than codes of conduct or a prescriptive, formulaic approach

practice – practical know-how in terms of ethical solutions that engineers can apply

mindset – having an individual and group culture of acting ethically. The engineers’ problem-solving mindset must be supplemented by constant reflection on the decisions made and their ethical consequences.

Ethics is not an “add-on” subject. It must permeate all aspects of tertiary education – teaching, research and professional behaviour.

While the arguments for acting now are strong, market realities will also drive the process. The upcoming generation will likely displace those who are slow or reluctant to adapt.

For instance, engineering firms are under pressure from their own staff on the issue of climate change. More than 1,900 Australian engineers and nearly 180 engineering organisations have signed a declaration committing them to evaluate all new projects against the need to mitigate climate change.

Future engineers must transcend any remaining single-solution mindsets from the past. They’ll need to embrace a much more complex and socially minded ethics. And that begins with their university education.![]()

S. Travis Waller, Professor and Head of the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, UNSW; Kourosh Kayvani, Adjunct Professor of Engineering, UNSW; Lucy Marshall, Professor, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, UNSW, and Robert F. Care AM, Professor of Practice, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tokyo Olympiad, Kon Ichikawa’s documentary of the 1964 Games, is still a masterpiece

Of the countless documentaries about the Olympic Games, two have long held their place on the podium.

The first is Olympia (1938), Leni Riefenstahl’s landmark two-part film about the controversial 1936 Berlin Games. Funded by the Nazi regime and made with the backing of the International Olympic Committee, it is both a monumental propaganda piece and a majestic celebration of athletic strength and beauty.

The second is Kon Ichikawa’s far lesser known, but no less audacious, Tokyo Olympiad (1965).

Ichikawa was a prolific and renown director, best known for The Burmese Harp (1956) and Fires on the Plain (1959) — a pair of bleak, but humanistic, anti-war films — and the stylistically daring An Actor’s Revenge (1963).

Tokyo Olympiad was his first documentary. He held little interest in sport, let alone the Olympics, when he scored the gig.

For his homework, he studied Riefenstahl’s film exhaustively.

Like Riefenstahl, Ichikawa employed a vast array of techniques to showcase athletic feats with an abstract grandeur. And, like his predecessor, he was granted a wealth of access and resources: he had at his disposal more than 100 cameras, cutting-edge equipment and a small army of technicians.

Besides the historical and political context, there remains a crucial difference between the two documentaries. Fascism infused the Berlin Games and Riefenstahl’s film elevated the Olympics to mythic proportions, portraying athletes as something bordering on supernatural.

In Tokyo Olympiad, the athletes — like the spectators and officials given almost equal attention — come across as human. No more, and no less.

Read more: Leni Riefenstahl: both feminist icon and fascist film-maker

Moments Big And Small

Other than an occasional caption or narration, there is minimal effort to inform the viewer who won what at the 1964 Tokyo Games. While some key events receive their due coverage — Ethiopian Abebe Bikila’s marathon victory is given an epic treatment — others don’t get so much as a mention.

Tokyo Olympiad isn’t a film of facts and statistics. Ichikawa depicted events not necessarily as they happened, but as he saw them to be.

The wrestling is a claustrophobic tangling of limbs. The walking race a comical dance of bobbing heads and swaying butts. The rifle competition is reduced to a series of Sergio Leone-esque close-ups of eyes deep in concentration.

Despite the massive scope and scale of the production, Tokyo Olympiad is as committed to highlighting minutiae as to presenting spectacle.

There’s the fascinating, twitchy ritual of Soviet shot-putter Adolf Varanauskas before he makes the throw. The curious sight of Japanese hurdler Ikuko Yoda placing a lemon on the starting block. And the blistered and bleeding soles of marathon runners who collapse after they limp to the finish line.

When English runner Ann Packer wins the 800 metre final, Ichikawa replays the end of the race in slow motion with the soundtrack stripped almost bare, capturing the moment she smiles at her fiancé watching from the sidelines.

Ichikawa dedicates as many close-ups to spectators as he does to competitors. He delights in watching officials scrambling to ensure events run smoothly. He crafts impressionistic interludes: a frenzied montage of typewriters in the press room; a melancholic passage showing the rain beginning to fall.

Winners And Losers

The 1964 Tokyo Olympics embodied the optimism of Japan’s triumphant economic and social transformation in the two decades after the second world war. But there’s little flag-waving in Ichikawa’s film. The city is hardly shown. The Japanese team’s 16 gold medals (behind only the US and USSR) is underplayed.

The Japanese authorities who commissioned the film were expecting a straightforward documentary which faithfully recorded results and promoted the nation’s achievements. They were unimpressed by Ichikawa’s artistry.

Their disapproval did not affect audiences’ enthusiasm. Tokyo Olympiad was watched by 23 million people upon its release in Japan, holding the box-office attendance record until Hiyao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away in 2001.

Ichikawa’s refusal to bow to patriotic impulses wasn’t a simple act of defiance (ironically, Japanese leftists also criticised the film for being too nationalistic). His stance was consistent: he celebrated the underdogs and the losers as much as the winners; he privileged individuals over the nations they represented.

American Billy Mills won the 10,000 metre race, but in Tokyo Olympiad images of lesser athletes linger just as strongly. A runner’s surprise at getting lapped is captured in a freeze frame; a dejected participant is shown unable to finish. A competitor from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) comes dead last, but receives a rousing ovation as he runs the final lap alone.

Elsewhere, Ichikawa devotes a lengthy section to the middle-distance runner Ahmed Issa, one of just two representatives from the newly independent Chad. Issa doesn’t qualify for the final, but Ichikawa is drawn to his quiet dignity and resilience. He follows the athlete as he arrives in Tokyo, wanders the streets, runs his race, and eats alone in the mess hall after bowing out of the competition.

This emphasis on an unknown athlete from a little-known nation, whom history likely would’ve forgotten otherwise, speaks volumes about Ichikawa’s priorities.

Tokyo Olympiad Mark II

The celebrated Japanese director Naomi Kawase has been commissioned to make the official 2021 documentary. Her assignment may be the toughest yet.

The optimism that surrounded the 1964 Games is in short supply. Most in Japan oppose the Olympics going ahead. Medical experts continue to warn of the dangers of pressing on. If Kawase points her cameras at the stands, they will be empty.

Kawase has huge shoes to fill. She’ll be following in the footsteps of a fellow Japanese director who made one of the great sporting documentaries — if not simply one of the great documentaries.

But she will, no doubt, make the 2021 Games her own.

The restored Tokyo Olympiad can be streamed on the International Olympic Committee website.![]()

Kenta McGrath, Sessional Academic in Screen Arts, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tasmanian author Amanda Lohrey wins prestigious Miles Franklin Literary Award for The Labyrinth

And the winner of 2021’s Miles Franklin Literary Award is The Labyrinth, by Amanda Lohrey!

Two of Lohrey’s previous novels (Camille’s Bread in 1996 and The Philosopher’s Doll in 2005) have been shortlisted for the prestigious $60,000 prize. Her latest has been recognised as the literary volume that best presents Australian life now. She is the second Tasmanian author to ever win the prize.

As a long-time fan of Lohrey’s voice and eye, and someone with a lifetime of longing for more recognition of women’s achievements, I am thrilled to see her novel and her protagonist Erica achieve this standing.

Read more: The saddest of stories, beautifully told: your guide to the Miles Franklin 2021 shortlist

Prickly But Appealing

Erica is an often prickly but generous and appealing character. Though she grows up “in an asylum, a manicured madhouse”, her childhood is much happier than is the norm for characters in literary fiction. Her father, the chief medical officer of the hospital, trains his children in diversity. All of us are “lunatics”, he teaches them, in that “we are all affected by the moon”. “Evil,” he tells them, is no more than “a chemical malfunction in the brain”.

This is an excellent foundation for someone who, in later life, finds herself with a son whose “chemical malfunction” leads him to commit an inadvertent but terrible crime. The beach shack she purchases to be near him, and far from everyone else she knows, is as disorganised and disreputable as her child. But it gives her somewhere to review her life and re-imagine a future.

That future circles around the concept of the labyrinth. Much of the novel is a masterclass in types of these mazes and the meanings and feelings the various designs afford.

A Way Through

All this operates as a healing process following the agony of her son’s act, trial and imprisonment. She — or rather, her planned labyrinth — gradually draws the attention of other isolates who live in the same coastal community. Various people become closely connected to her and one, Jurko, happens to know about labyrinths and their construction.

The young man, “an illegal immigrant who has overstayed his visa”, is a stonemason (a master of that ancient art) and he gradually inserts himself into her home and her life to become her “surrogate son”.