Inbox and Environment News: Issue 504

August 1 - 7, 2021: Issue 504

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment August Newsletter, Forum & 2021 AGM

.jpg?timestamp=1627676810014)

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Newsletter No: 88

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA) Newsletter No: 88

Discussion Paper To Encourage Views On Proposed Planning Controls

- improved controls for development near waterways, foreshores, wetlands and riparian lands;

- more water sensitive urban design and greater tree canopy;

- performance standards for net-zero carbon emission buildings;

- reducing areas for permitted dual occupancy, boarding houses and seniors’ housing to reduce inappropriate development in sensitive locations;

- provisions to restrict large scale retail in small retail centres.

Echidna Breeding Season Commences

Reinstate The Marine Reserve From Rock Pool “Kiddies Corner” South Palm Beach: Petition

Repeat Offender Banned From Fishing For 5 Years

Fisheries Officers Crack Down On Illegal Fishing During Lockdown

New Expert Analysis Reveals NSW IPC Has “Comprehensively Failed” To Mitigate Greenhouse Emissions

“Even if it were considered acceptable to overlook the huge contribution to climate change of Scope 3 emissions from these projects, the Scope 1 and 2 emissions add up to 89 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent; that is nearly 20 per cent of Australia’s total national emissions last year. Reducing or, ideally, eliminating those emissions would be a significant contribution to our obligation to help slow climate change."

NSW Government Introduces New Mining Rehabilitation Rules

- prepare a management plan to identify and achieve rehabilitation outcomes

- carry out rehabilitation risk assessments

- develop a program to demonstrate an approach to progressive rehabilitation

- make information about rehabilitation publicly available

- report annually on rehabilitation performance.

Reckless Plans For Kosciuszko National Park Must Be Stopped

- Increasing overnight accommodation in the park from 10,000 to 14,000 beds.

- Allowing helicopters flights into the ski fields.

- Expanding carparks and building new ones.

- Allowing vehicles onto iconic walking tracks.

- Artificially heating the waters at Yarrangobilly thermal pools.

Drone Technology Keeping A Watchful Eye On Whales This Migration Season

- The Right Whale ID citizen science project will recruit skilled drone operators to take specific images of southern right whales (SRW) in NSW waters, to increase knowledge and understanding about this endangered species.

- This project will be run as a pilot in 2021.

- It will be managed by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- The Right Whale ID program is funded under the Marine Estate Management Strategy (MEMS).

- Images will become available in the coming months at Threatened and protected species

- This year the project aims to train 20 volunteer drone operators along the NSW coast.

- These drone operators are members of the public, usually enthusiastic amateurs, some of whom have taken drone vision for NPWS in the past.

- All drone operators involved in this project are CASA registered and accredited.

- All operators must undertake training with NPWS Marine Wildlife Officers before joining the volunteer program to ensure they comply with Biodiversity Conservation Regulations (2017).

- The South-eastern Australian population of SRW is estimated to be less than 300 individuals, with less than 30 mothers expected to give birth in either Victoria or NSW waters this year.

- Unlike humpback whales, the endangered SRW uses coastal bays and beaches to breed, give birth, mother and rest before heading back to Antarctic waters to feed.

- This closeness to the shore can make them more vulnerable to disturbance from on-lookers on or in the water.

- The project will record details about individual SRWs, now endangered in NSW waters.

- Understanding the patterns of habitual use at different locations along the NSW coast will lead to better management and planning for their benefit.

- If you see a stranded, entangled, or sick whale, or a sighting of a southern right whale please report it immediately to NPWS on 13000 PARKS or ORRCA Whale and Dolphin Rescue on (02) 9415 3333 (24 hours hotline).

Dead, shrivelled frogs are unexpectedly turning up across eastern Australia. We need your help to find out why

Over the past few weeks, we’ve received a flurry of emails from concerned people who’ve seen sick and dead frogs across eastern Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland.

One person wrote:

About a month ago, I noticed the Green Tree Frogs living around our home showing signs of lethargy & ill health. I was devastated to find about 7 of them dead.

Another wrote:

We previously had a very healthy population of green tree frogs and a couple of months ago I noticed a frog that had turned brown. I then noticed more of them and have found numerous dead frogs around our property.

And another said she’d seen so many dead frogs on her daily runs she had to “seriously wonder how many more are there”.

So what’s going on? The short answer is: we don’t really know. How many frogs have died and why is a mystery, and we’re relying on people across Australia to help us solve it.

Why Are Frogs Important?

Frogs are an integral part of healthy Australian ecosystems. While they are usually small and unseen, they’re an important thread in the food web, and a kind of environmental glue that keeps ecosystems functioning. Healthy frog populations are usually a good indication of a healthy environment.

They eat vast amounts of invertebrates, including pest species, and they’re a fundamental food source for a wide variety of other wildlife, including birds, mammals and reptiles. Tadpoles fill our creeks and dams, helping keep algae and mosquito larvae under control while they too become food for fish and other wildlife.

But many of Australia’s frog populations are imperilled from multiple, compounding threats, such as habitat loss and modification, climate change, invasive plants, animals and diseases.

Although we’re fortunate to have at least 242 native frog species in Australia, 35 are considered threatened with extinction. At least four are considered extinct: the southern and northern gastric-brooding frogs (Rheobatrachus silus and Rheobatrachus vitellinus), the sharp-snouted day frog (Taudactylus acutirostris) and the southern day frog (Taudactylus diurnus).

A Truly Unusual Outbreak

In most circumstances, it’s rare to see a dead frog. Most frogs are secretive in nature and, when they die, they decompose rapidly. So the growing reports of dead and dying frogs from across eastern Australia over the last few months are surprising, to say the least.

While the first cold snap of each year can be accompanied by a few localised frog deaths, this outbreak has affected more animals over a greater range than previously encountered.

This is truly an unusual amphibian mass mortality event.

In this outbreak, frogs appear to be either darker or lighter than normal, slow, out in the daytime (they’re usually nocturnal), and are thin. Some frogs have red bellies, red feet, and excessive sloughed skin.

The iconic green tree frog (Litoria caeulea) seems hardest hit in this event, with the often apple-green and plump frogs turning brown and shrivelled.

This frog is widespread and generally rather common. In fact, it’s the ninth most commonly recorded frog in the national citizen science project, FrogID. But it has disappeared from parts of its former range.

Other species reported as being among the sick and dying include Peron’s tree frog (Litoria peronii), the Stony Creek frog (Litoria lesueuri), and green stream frog (Litoria phyllochroa). These are all relatively common and widespread species, which is likely why they have been found in and around our gardens.

We simply don’t know the true impacts of this event on Australia’s frog species, particularly those that are rare, cryptic or living in remote places. Well over 100 species of frog live within the geographic range of this outbreak. Dozens of these are considered threatened, including the booroolong Frog (Litoria booroolongensis) and the giant barred frog (Mixophyes iteratus).

So What Might Be Going On?

Amphibians are susceptible to environmental toxins and a wide range of parasitic, bacterial, viral and fungal pathogens. Frogs globally have been battling it out with a pandemic of their own for decades — a potentially deadly fungus often called amphibian chytrid fungus.

This fungus attacks the skin, which frogs use to breathe, drink, and control electrolytes important for the heart to function. It’s also responsible for causing population declines in more than 500 amphibian species around the world, and 50 extinctions.

For example, in Australia the bright yellow and black southern corroboree frog (Pseudophryne corroboree) is just hanging on in the wild, thanks only to intensive management and captive breeding.

Curiously, some other frog species appear more tolerant to the amphibian chytrid fungus than others. Many now common frogs seem able to live with the fungus, such as the near-ubiquitous Australian common eastern froglet (Crinia signifera).

But if frogs have had this fungus affecting them for decades, why are we seeing so many dead frogs now?

Read more: A deadly fungus threatens to wipe out 100 frog species – here's how it can be stopped

Well, disease is the outcome of a battle between a pathogen (in this case a fungus), a host (in this case the frog) and the environment. The fungus doesn’t do well in warm, dry conditions. So during summer, frogs are more likely to have the upper hand.

In winter, the tables turn. As the frog’s immune system slows, the fungus may be able to take hold.

Of course, the amphibian chytrid fungus is just one possible culprit. Other less well-known diseases affect frogs.

To date, the Australian Registry of Wildlife Health has confirmed the presence of the amphibian chytrid fungus in a very small number of sick frogs they’ve examined from the recent outbreak. However, other diseases — such as ranavirus, myxosporean parasites and trypanosome parasites — have also been responsible for native frog mass mortality events in Australia.

It’s also possible a novel or exotic pathogen could be behind this. So the Australian Registry of Wildlife Health is working with the Australian Museum, government biosecurity and environment agencies as part of the investigation.

Here’s How You Can Help

While we suspect a combination of the amphibian chytrid fungus and the chilly temperatures, we simply don’t know what factors may be contributing to the outbreak.

We also aren’t sure how widespread it is, what impact it will have on our frog populations, or how long it will last.

While the temperatures stay low, we suspect our frogs will continue to succumb. If we don’t investigate quickly, we will lose the opportunity to achieve a diagnosis and understand what has transpired.

We need your help to solve this mystery.

Please send any reports of sick or dead frogs (and if possible, photos) to us, via the national citizen science project FrogID, or email calls@frogid.net.au.

Read more: Clicks, bonks and dripping taps: listen to the calls of 6 frogs out and about this summer ![]()

Jodi Rowley, Curator, Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Biology, UNSW, Australian Museum and Karrie Rose, Australian Registry of Wildlife Health - Taronga Conservation Society Australia, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

You may have heard the ‘moon wobble’ will intensify coastal floods. Well, here’s what that means for Australia

Extreme floods this month have been crippling cities worldwide. This week in China’s Henan province, a year’s worth of rain fell in just three days. Last week, catastrophic floods swept across western Germany and parts of Belgium. And at home, rain fell in Perth for 17 days straight, making it the city’s wettest July in 20 years.

But torrential rain isn’t the only cause of floods. Many coastal towns and cities in Australia would already be familiar with what are known as “nuisance” floods, which occur during some high tides.

A recent study from NASA and the University of Hawaii suggests even nuisance floods are set to get worse in the mid-2030s as the moon’s orbit begins another phase, combined with rising sea levels from climate change.

The study was conducted in the US. But what do its findings mean for the vast lengths of coastlines in Australia and the people who live there?

A Triple Whammy

We know average sea levels are rising from climate change, and we know small rises in average sea levels amplify flooding during storms. From the perspective of coastal communities, it’s not if a major flood will occur, it’s when the next one will arrive, and the next one after that.

But we know from historical and paleontological records of flooding events that in many, if not most, cases the coastal flooding we’ve directly experienced in our lifetimes are simply the entrée in terms of what will occur in future.

Flooding is especially severe when a storm coincides with a high tide. And this is where NASA and the University of Hawaii’s new research identified a further threat.

Researchers looked at the amplification phase of the natural 18.6-year cycle of the “wobble” in the moon’s orbit, first identified in 1728.

The orbit of the moon around the sun is not quite on a flat plane (planar); the actual orbit oscillates up and down a bit. Think of a spinning plate on a stick — the plate spins, but also wobbles up and down.

Read more: Predators, prey and moonlight singing: how phases of the Moon affect native wildlife

When the moon is at particular parts of its wobbling orbit, it pulls on the water in the oceans a bit more. This means for some years during the 18.6-year cycle, some high tides are higher than they would have otherwise been.

This results in increases to daily tidal rises, and this, in turn, will exacerbate coastal flooding, whether it be nuisance flooding in vulnerable areas, or magnified flooding during a storm.

A major wobble amplification phase will occur in the mid-2030s, when climate change will make the problem become severe in some cases.

The triple whammy of the wobble in the moon’s orbit, ongoing upwards creep in sea levels from ocean warming, and more intense storms associated with climate change, will bring the impacts of sea-level rise earlier than previously expected — in many locations around the world. This includes in Australia.

So What Will Happen In Australia?

The locations in Australia where tides have the largest range, and will be most impacted by the wobble, aren’t close to the major population centres. Australia’s largest tides are close to Broad Sound, near Hay Point in central Queensland, and Derby in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

However, many Australian cities host suburbs that routinely flood during larger high tides. Near my home in Meanjin (Brisbane), the ocean regularly backs up through the storm water drainage system during large high tides. At times, even getting from the front door to the street can be challenging.

Some bayside suburbs in Melbourne are also already exposed to nuisance flooding. But a number of others that are not presently exposed may also become more vulnerable from the combined influence of the moon wobble and climate change — even when the weather is calm. High tide during this lunar phase, occurring during a major rainfall event, will result in even greater risk.

Read more: High-tide flood risk is accelerating, putting coastal economies at risk

In high-income nations like Australia, sea-level rise means increasing unaffordability of insurance for coastal homes, followed by an inability to seek insurance cover at all and, ultimately, reductions in asset values for those unable or unwilling to adapt.

The prognosis for lower-income coastal communities that aren’t able to adapt to sea-level rise is clear: increasingly frequent and intense flooding will make many aspects of daily life difficult to sustain. In particular, movement around the community will be challenging, homes will often be inundated, unhealthy and untenable, and the provision of basic services problematic.

What Do We Do About It?

While our hearts and minds continue to be occupied by the pandemic, threats from climate change to our ongoing standard of living, or even future viability on this planet, haven’t slowed. We can pretend to ignore what is happening and what is increasingly unstoppable, or we can proactively manage the increasing threat.

Thankfully, approaches to adapting the built and natural environment to sea-level rise are increasingly being applied around the world. Many major cities have already embarked on major coastal adaptation programs – think London, New York, Rotterdam, and our own Gold Coast.

However, the uptake continues to lag behind the threat. And one of the big challenges is to incentivise coastal adaptation without overly impacting private property rights.

Read more: For flood-prone cities, seawalls raise as many questions as they answer

Perhaps the best approach to learning to live with water is led by the Netherlands. Rather than relocating entire communities or constructing large barriers like sea walls, this nation is finding ways to reduce the overall impact of flooding. This includes more resilient building design or reducing urban development in specific flood retention basins. This means flooding can occur without damaging infrastructure.

There are lessons here. Australia’s adaptation discussions have often focused on finding the least worst choice between constructing large seawalls or moving entire communities — neither of which are often palatable. This leads to inaction, as both options aren’t often politically acceptable.

The seas are inexorably creeping higher and higher. Once thought to be a problem for our grandchildren, it is becoming increasingly evident this is a challenge for the here and now. The recently released research confirms this conclusion.

Read more: King tides and rising seas are predictable, and we're not doing enough about it ![]()

Mark Gibbs, Principal Engineer: Reef Restoration, Australian Institute of Marine Science

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change is causing tuna to migrate, which could spell catastrophe for the small islands that depend on them

Katherine Seto, University of Wollongong; Johann Bell, University of Wollongong; Quentin Hanich, University of Wollongong, and Simon Nicol, University of CanberraSmall Pacific Island states depend on their commercial fisheries for food supplies and economic health. But our new research shows climate change will dramatically alter tuna stocks in the tropical Pacific, with potentially severe consequences for the people who depend on them.

As climate change warms the waters of the Pacific, some tuna will be forced to migrate to the open ocean of the high seas, away from the jurisdiction of any country. The changes will affect three key tuna species: skipjack, yellowfin, and bigeye.

Pacific Island nations such as the Cook Islands and territories such as Tokelau charge foreign fishing operators to access their waters, and heavily depend on this revenue. Our research estimates the movement of tuna stocks will cause a fall in annual government revenue to some of these small island states of up to 17%.

This loss will hurt these developing economies, which need fisheries revenue to maintain essential services such as hospitals, roads and schools. The experience of Pacific Island states also bodes poorly for global climate justice more broadly.

Island States At Risk

Catches from the Western and Central Pacific represent over half of all tuna produced globally. Much of this catch is taken from the waters of ten small developing island states, which are disproportionately dependent on tuna stocks for food security and economic development.

These states comprise:

- Cook Islands

- Federated States of Micronesia

- Kiribati

- Marshall Islands

- Nauru

- Palau

- Papua New Guinea

- Solomon Islands

- Tokelau

- Tuvalu

Their governments charge tuna fishing access fees to distant nations of between US$7.1 million (A$9.7 million) and $134 million (A$182 million), providing an average of 37% of total government revenue (ranging from 4-84%).

Tuna stocks are critical for these states’ current and future economic development, and have been sustainably managed by a cooperative agreement for decades. However, our analysis reveals this revenue, and other important benefits fisheries provide, are at risk.

Read more: Warming oceans are changing Australia's fishing industry

Climate Change And Migration

Tuna species are highly migratory – they move over large distances according to ocean conditions. The skipjack, yellowfin and bigeye tuna species are found largely within Pacific Island waters.

Concentrations of these stocks normally shift from year to year between areas further to the west in El Niño years, and those further east in La Niña years. However, under climate change, these stocks are projected to shift eastward – out of sovereign waters and into the high seas.

Under climate change, the tropical waters of the Pacific Ocean will warm further. This warming will result in a large eastward shift in the location of the edge of the Western Pacific Warm Pool (a mass of water in the western Pacific Ocean with consistently high water temperatures) and subsequently the prime fishing grounds for some tropical tuna.

This shift into areas beyond national jurisdiction would result in weaker regulation and monitoring, with parallel implications for the long-term sustainability of stocks.

What Our Research Found

Combining climate science, ecological models and economic data from the region, our research published today in Nature Sustainability shows that under strong projections of climate change, small island economies are poised to lose up to US$140 million annually by 2050, and up to 17% of annual government revenue in the case of some states.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provides scenarios of various greenhouse gas concentrations, called “representative concentration pathways” (RCP). We used a higher RCP of 8.5 and a more moderate RCP of 4.5 to understand tuna movement in different emissions scenarios.

Read more: Citizen scientist scuba divers shed light on the impact of warming oceans on marine life

In the RCP 8.5 scenario, by 2050, our model predicted the total biomass of the three species of tuna in the combined jurisdictions of the ten Pacific Island states would decrease by an average of 13%, and up to 20%.

But if emissions were kept to the lower RCP 4.5 scenario, the effects are expected to be far less pronounced, with an average decrease in biomass of just 1%.

While both climate scenarios result in average losses of both tuna catches and revenue, lower emissions scenarios lead to drastically smaller losses, highlighting the importance of climate action.

These projected losses compound the existing climate vulnerability of many Pacific Island people, who will endure some of the earliest and harshest climate realities, while being responsible for only a tiny fraction of global emissions.

What Can Be Done?

Capping greenhouse gas emissions, and reducing them to levels aligning with the Paris Agreement, would reduce multiple climate impacts for these states, including shifting tuna stocks.

In many parts of the world, the consequences of climate change compound upon one another to create complex injustices. Our study identifies new direct and indirect implications of climate change for some of the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Read more: The 2016 Great Barrier Reef heatwave caused widespread changes to fish populations ![]()

Katherine Seto, Research Fellow, University of Wollongong; Johann Bell, Visiting Professorial Fellow, University of Wollongong; Quentin Hanich, Associate Professor, University of Wollongong, and Simon Nicol, Adjunct professor, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

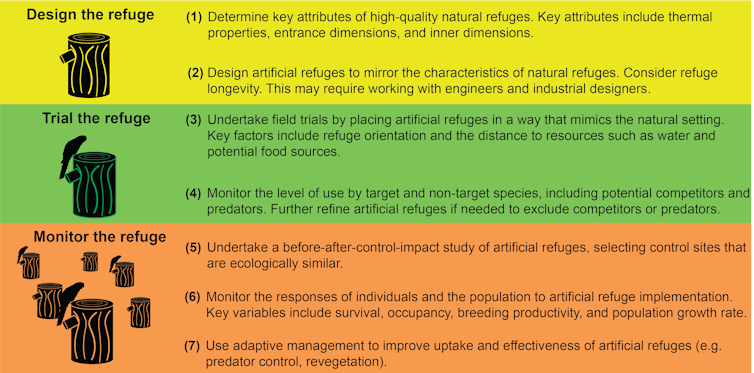

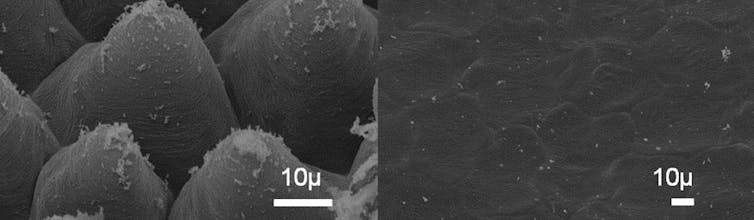

Artificial refuges are a popular stopgap for habitat destruction, but the science isn’t up to scratch

Wildlife worldwide is facing a housing crisis. When land is cleared for agriculture, mining, and urbanisation, habitats and natural refuges go with it, such as tree hollows, rock piles and large logs.

The ideal solution is to tackle the threats that cause habitat loss. But some refuges take hundreds of years to recover once destroyed, and some may never recover without help. Tree hollows, for example, can take 180 years to develop.

As a result, conservationists have increasingly looked to human-made solutions as a stopgap. That’s where artificial refuges come in.

If the goal of artificial refuges is to replace lost or degraded habitat, then it is important we have a good understanding of how well they perform. Our new research reviewed artificial refuges worldwide — and we found the science underpinning them is often not up to scratch.

What Are Artificial Refuges?

Artificial refuges provide wildlife places to shelter, breed, hibernate, or nest, helping them survive in disturbed environments, whether degraded forests, deserts or urban and agricultural landscapes.

You’re probably already familiar with some. Nest boxes for birds and mammals are one example found in many urban and rural areas. They provide a substitute for tree hollows when land is cleared.

Other examples include artificial stone cavities used in Norway to provide places for newts to hibernate in urban and agricultural environments, and artificial bark used in the USA to allow bats to roost in the absence of trees. And in France, artificial burrows provide refuge for lizards in lieu of their favoured rabbit burrows.

But Do We Know If They Work?

Artificial refuges can be highly effective. In central Europe, for example, nest boxes allowed isolated populations of a colourful bird, the hoopoe, to reconnect — boosting the local genetic diversity.

Still, they are far from a sure thing, having at times fallen short of their promise to provide suitable homes for wildlife.

One study from Catalonia found 42 soprano pipistrelles (a type of bat) had died from dehydration within wooden bat boxes, due to a lack of ventilation and high sun exposure.

Another study from Australia found artificial burrows for the endangered pygmy blue tongue lizard had a design flaw that forced lizards to enter backwards. This increased their risk of predation from snakes and birds.

And the video below from Czech conservation project Birds Online shows a pine marten (a forest-dwelling mammal) and tree sparrow infiltrating next boxes to steal the eggs of Tengmalm’s owls and common starlings.

So Why Is This Happening?

Our research investigated the state of the science regarding artificial refuges worldwide.

We looked at more than 220 studies, and we found they often lacked the rigour to justify their widespread use as a conservation tool. Important factors were often overlooked, such as how temperatures inside artifical refuges compare to natural refuges, and the local abundance of food or predators.

Alarmingly, just under 40% of studies compared artificial refuges to a control, making it impossible to determine the impacts artificial refuges have on the target species, positive or negative.

This is a big problem, because artificial refuges are increasingly incorporated into programs that seek to “offset” habitat destruction. Offsetting involves protecting or creating habitat to compensate for ecological harm caused by land clearing from, for instance, mining or urbanisation.

For example, one project in Australia relied heavily on nest boxes to offset the loss of old, hollow-bearing trees.

But a scientific review of the project showed it to be a failure, due to low rates of uptake by target species (such as the superb parrot) and the rapid deterioration of the nest boxes from falling trees.

Read more: The plan to protect wildlife displaced by the Hume Highway has failed

The Future Of Artificial Refuges

There is little doubt artificial refuges will continue to play a role in confronting Earth’s biodiversity crisis, but their limitations need to be recognised, and the science underpinning them must improve. Our new review points out areas of improvement that spans design, implementation, and monitoring, so take a look if you’re involved in these sorts of projects.

We also urge for more partnerships between ecologists, engineers, designers and the broader community. This is because interdisciplinary collaboration brings together different ways of thinking and helps to shed new light on complex problems.

It’s clear improving the science around artificial refuges is well worth the investment, as they can give struggling wildlife worldwide a fighting chance against further habitat destruction and climate change.

Read more: To save these threatened seahorses, we built them 5-star underwater hotels ![]()

Darcy Watchorn, PhD Candidate, Deakin University; Dale Nimmo, Associate Professor in Ecology, Charles Sturt University; Mitchell Cowan, PhD Candidate, Charles Sturt University, and Tim Doherty, ARC DECRA Fellow, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

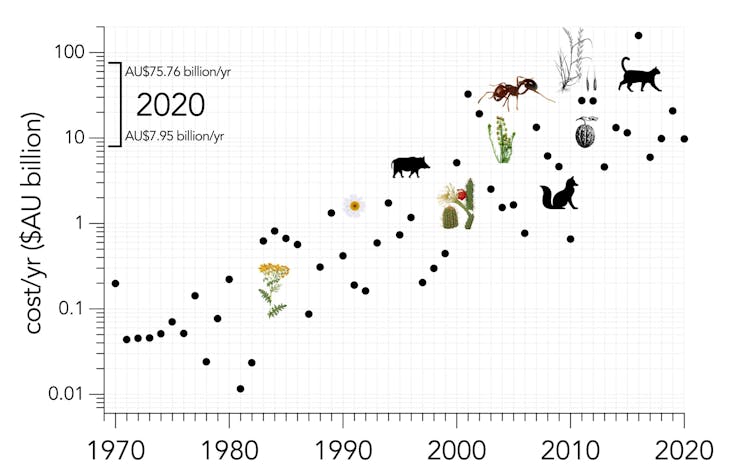

Pest plants and animals cost Australia around $25 billion a year – and it will get worse

Shamefully, Australia has one of the highest extinction rates in the world. And the number one threat to our species is invasive or “alien” plants and animals.

But invasive species don’t just cause extinctions and biodiversity loss – they also create a serious economic burden. Our research, published today, reveals invasive species have cost the Australian economy at least A$390 billion in the last 60 years alone.

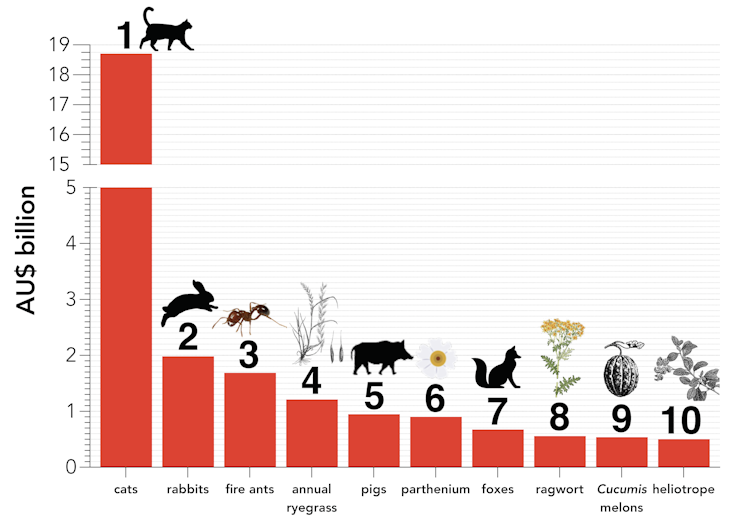

Our paper – the most detailed assessment of its type ever published in this country – also reveals feral cats are the worst invasive species in terms of total costs, followed by rabbits and fire ants.

Without urgent action, Australia will continue to lose billions of dollars every year on invasive species.

Huge Economic Burden

Invasive species are those not native to a particular ecosystem. They are introduced either by accident or on purpose and become pests.

Some costs involve direct damage to agriculture, such as insects or fungi destroying fruit. Other examples include measures to control invasive species like feral cats and cane toads, such as paying field staff and buying fuel, ammunition, traps and poisons.

Our previous research put the global cost of invasive species at A$1.7 trillion. But this is most certainly a gross underestimate because so many data are missing.

Read more: Attack of the alien invaders: pest plants and animals leave a frightening $1.7 trillion bill

As a wealthy nation, Australia has accumulated more reliable cost data than most other regions. These costs have increased exponentially over time – up to sixfold each decade since the 1970s.

We found invasive species now cost Australia around A$24.5 billion a year, or an average 1.26% of the nation’s gross domestic product. The costs total at least A$390 billion in the past 60 years.

Worst Of The Worst

Our analysis found feral cats have been the most economically costly species since 1960. Their A$18.7 billion bill is mainly associated with attempts to control their abundance and access, such as fencing, trapping, baiting and shooting.

Feral cats are a main driver of extinctions in Australia, and so perhaps investment to limit their damage is worth the price tag.

As a group, the management and control of invasive plants proved the worst of all, collectively costing about A$200 billion. Of these, annual ryegrass, parthenium and ragwort were the costliest culprits because of the great effort needed to eradicate them from croplands.

Invasive mammals were the next biggest burdens, costing Australia A$63 billion.

Variation Across Regions

For costs that can be attributed to particular states or territories, New South Wales had the highest costs, followed by Western Australia then Victoria.

Red imported fire ants are the costliest species in Queensland, and ragwort is the economic bane of Tasmania.

The common heliotrope is the costliest species in both South Australia and Victoria, and annual ryegrass tops the list in WA.

In the Northern Territory, the dothideomycete fungus that causes banana freckle disease brings the greatest economic burden, whereas cats and foxes are the costliest species in the ACT and NSW.

Better Assessments Needed

Our study is one of 19 region-specific analyses released today. Because the message about invasive species must get out to as many people as possible, our article’s abstract was translated into 24 languages.

This includes Pitjantjatjara, a widely spoken Indigenous language.

Even the massive costs we reported are an underestimate. This is because of we haven’t yet surveyed all the places these species occur, and there is a lack of standardised reporting by management authorities and other agencies.

For example, our database lists several fungal plant pathogens. But no cost data exist for some of the worst offenders, such as the widespread Phytophthora cinnamomi pathogen that causes major crop losses and damage to biodiversity.

Developing better methods to estimate the environmental impacts of invasive species, and the benefit of management actions, will allow us to use limited resources more efficiently.

A Constant Threat

Many species damaging to agriculture and the environment are yet to make it to our shores.

The recent arrival in Australia of fall armyworm, a major agriculture pest, reminds us how invasive species will continue their spread here and elsewhere.

As well as the economic damage, invasive species also bring intangible costs we have yet to measure adequately. These include the true extent of ecological damage, human health consequences, erosion of ecosystem services and the loss of cultural values.

Without better data, increased investment, a stronger biosecurity system and interventions such as animal culls, invasive species will continue to wreak havoc across Australia.

The authors acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which they did this research.

Ngadlu tampinthi yalaka ngadlu Kaurna yartangka inparrinthi. Ngadludlu tampinthi, parnaku tuwila yartangka.![]()

Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Professor of Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University and Andrew Hoskins, Research scientist CSIRO Health and Biosecurity, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

More livestock, more carbon dioxide, less ice: the world’s climate change progress since 2019 is (mostly) bad news

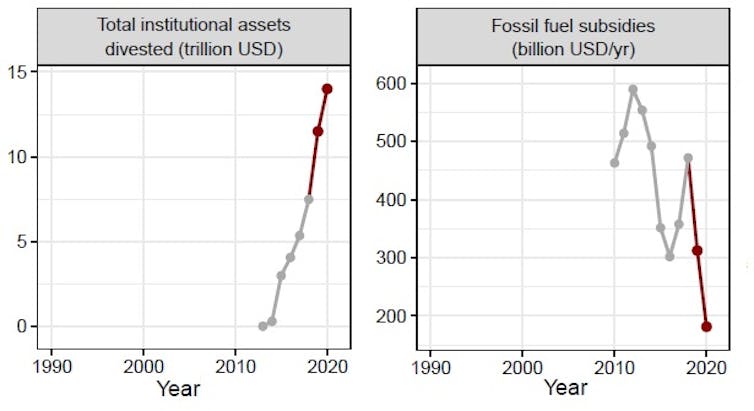

Thomas Newsome, University of Sydney; Christopher Wolf, Oregon State University, and William Ripple, Oregon State UniversityBack in 2019, more than 11,000 scientists declared a global climate emergency. They established a comprehensive set of vital signs that impact or reflect the planet’s health, such as forest loss, fossil fuel subsidies, glacier thickness, ocean acidity and surface temperature.

In a new paper published today, we show how these vital signs have changed since the original publication, including through the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, while we’ve seen lots of positive talk and commitments from some governments, our vital signs are mostly not trending in the right direction.

So, let’s look at how things have progressed since 2019, from the growing number of livestock to the meagre influence of the pandemic.

Is It All Bad News?

No, thankfully. Fossil fuel divestment and fossil fuel subsidies have improved in record-setting ways, potentially signalling an economic shift to a renewable energy future.

However, most of the other vital signs reflect the consequences of the so far unrelenting “business as usual” approach to climate change policy worldwide.

Especially troubling is the unprecedented surge in climate-related disasters since 2019. This includes devastating flash floods in the South Kalimantan province of Indonesia, record heatwaves in the southwestern United States, extraordinary storms in India and, of course, the 2019-2020 megafires in Australia.

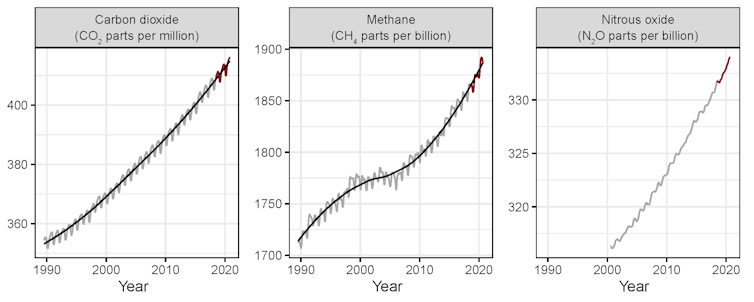

In addition, three main greenhouse gases — carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide — set records for atmospheric concentrations in 2020 and again in 2021. In April this year, carbon dioxide concentration reached 416 parts per million, the highest monthly global average concentration ever recorded.

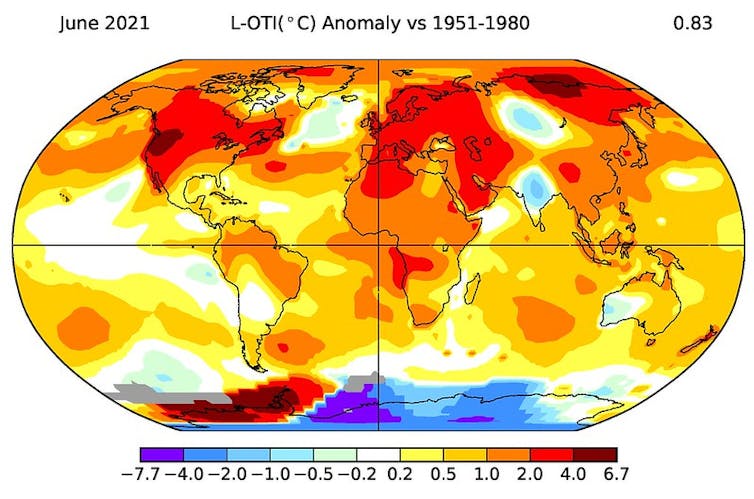

Last year was also the second hottest year in recorded history, with the five hottest years on record all occurring since 2015.

Ruminant livestock — cattle, buffalo, sheep, and goats — now number more than 4 billion, and their total mass is more than that of all humans and wild mammals combined. This is a problem because these animals are responsible for impacting biodiversity, releasing huge amounts of methane emissions, and land continues to be cleared to make room for them.

In better news, recent per capita meat production declined by about 5.7% (2.9 kilograms per person) between 2018 and 2020. But this is likely because of an outbreak of African swine fever in China that reduced the pork supply, and possibly also as one of the impacts of the pandemic.

Tragically, Brazilian Amazon annual forest loss rates increased in both 2019 and 2020. It reached a 12-year high of 1.11 million hectares deforested in 2020.

Ocean acidification is also near an all-time record. Together with heat stress from warming waters, acidification threatens the coral reefs that more than half a billion people depend on for food, tourism dollars and storm surge protection.

What About The Pandemic?

With its myriad economic interruptions, the COVID-19 pandemic had the side effect of providing some climate relief, but only of the ephemeral variety.

For example, fossil-fuel consumption has gone down since 2019 as did airline travel levels.

But all of these are expected to significantly rise as the economy reopens. While global gross domestic product dropped by 3.6% in 2020, it is projected to rebound to an all-time high.

So, a major lesson of the pandemic is that even when fossil-fuel consumption and transportation sharply decrease, it’s still insufficient to tackle climate change.

There is growing evidence we’re getting close to or have already gone beyond tipping points associated with important parts of the Earth system, including warm-water coral reefs, the Amazon rainforest and the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets.

OK, So What Do We Do About It?

In our 2019 paper, we urged six critical and interrelated steps governments — and the rest of humanity — can take to lessen the worst effects of climate change:

prioritise energy efficiency, and replace fossil fuels with low-carbon renewable energy

reduce emissions of short-lived pollutants such as methane and soot

curb land clearing to protect and restore the Earth’s ecosystems

reduce our meat consumption

move away from unsustainable ideas of ever-increasing economic and resource consumption

stabilise and, ideally, gradually reduce human populations while improving human well-being especially by educating girls and women globally.

These solutions still apply. But in our updated 2021 paper, we go further, highlighting the potential for a three-pronged approach for near-term policy:

a globally implemented carbon price

a phase-out and eventual ban of fossil fuels

strategic environmental reserves to safeguard and restore natural carbon sinks and biodiversity.

A global price for carbon needs to be high enough to induce decarbonisation across industry.

And our suggestion to create strategic environmental reserves, such as forests and wetlands, reflects the need to stop treating the climate emergency as a stand-alone issue.

By stopping the unsustainable exploitation of natural habitats through, for example, creeping urbanisation, and land degradation for mining, agriculture and forestry, we can reduce animal-borne disease risks, protect carbon stocks and conserve biodiversity — all at the same time.

Is This Actually Possible?

Yes, and many opportunities still exist to shift pandemic-related financial support measures into climate friendly activities. Currently, only 17% of such funds had been allocated that way worldwide, as of early March 2021. This percentage could be lifted with serious coordinated, global commitment.

Greening the economy could also address the longer term need for major transformative change to reduce emissions and, more broadly, the over-exploitation of the planet.

Our planetary vital signs make it clear we need urgent action to address climate change. With new commitments getting made by governments all over the world, we hope to see the curves in our graphs changing in the right directions soon.

Read more: 11,000 scientists warn: climate change isn't just about temperature ![]()

Thomas Newsome, Academic Fellow, University of Sydney; Christopher Wolf, Postdoctoral Scholar, Oregon State University, and William Ripple, Distinguished Professor and Director, Trophic Cascades Program, Oregon State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

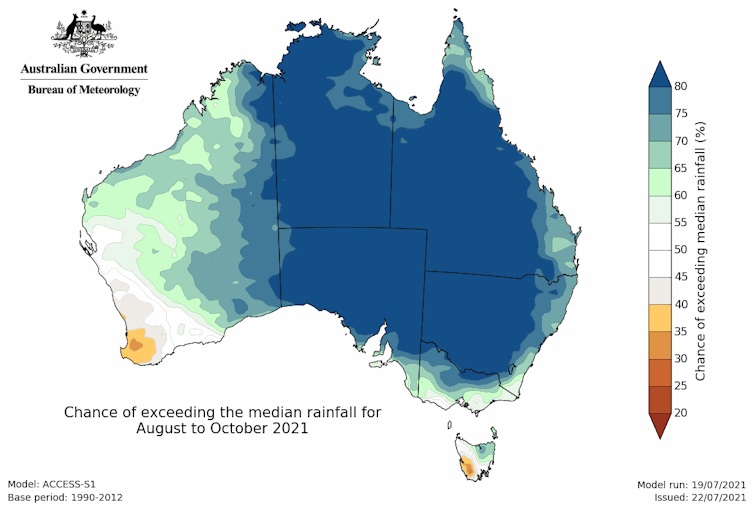

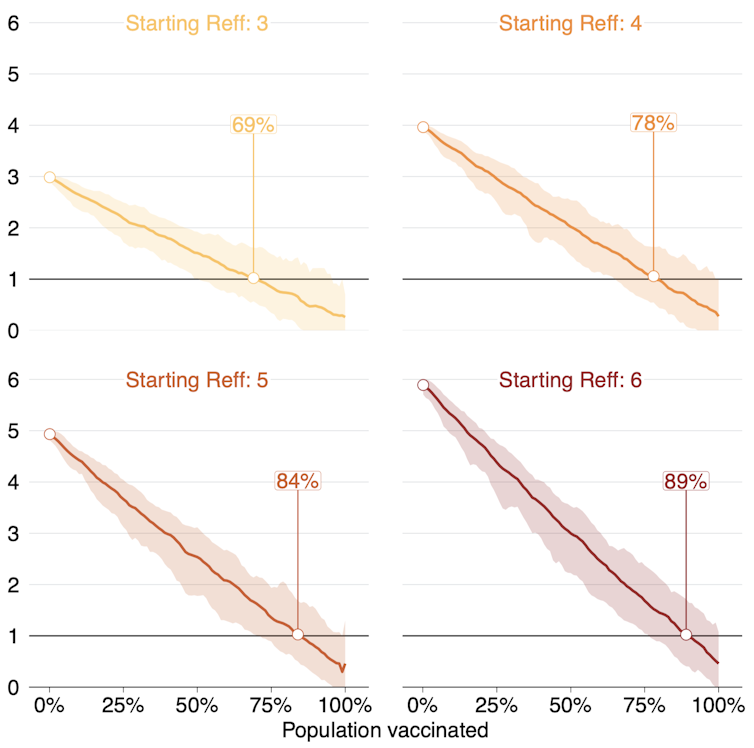

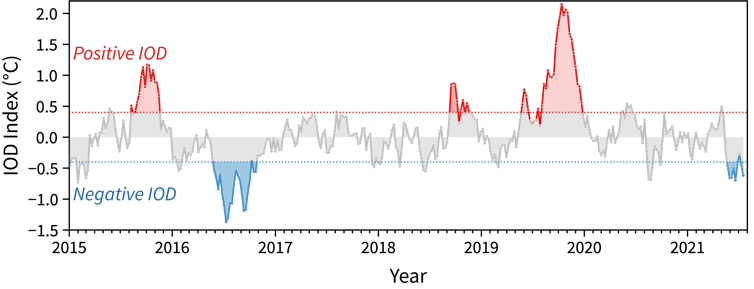

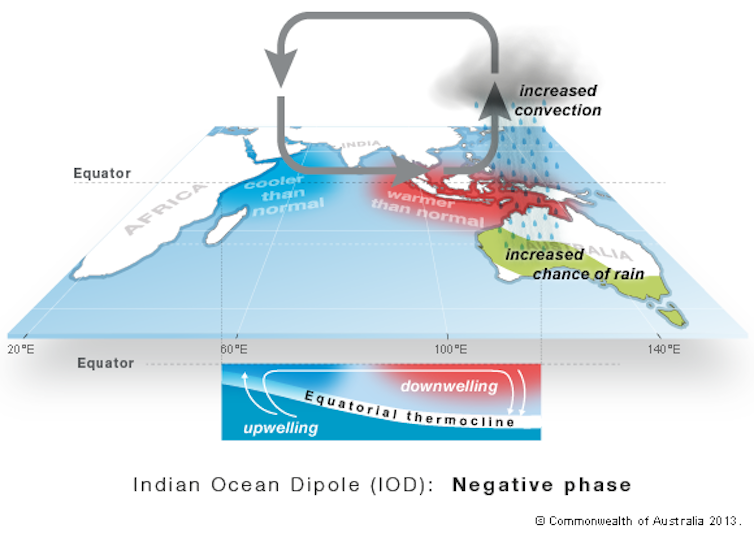

A wet winter, a soggy spring: what is the negative Indian Ocean Dipole, and why is it so important?

This month we’ve seen some crazy, devastating weather. Perth recorded its wettest July in decades, with 18 straight days of relentless rain. Overseas, parts of Europe and China have endured extensive flooding, with hundreds of lives lost and hundreds of thousands of people evacuated.

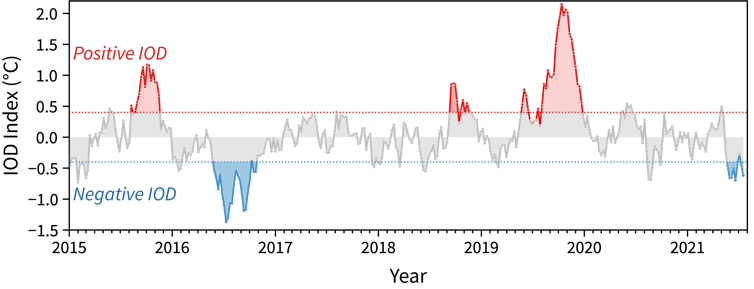

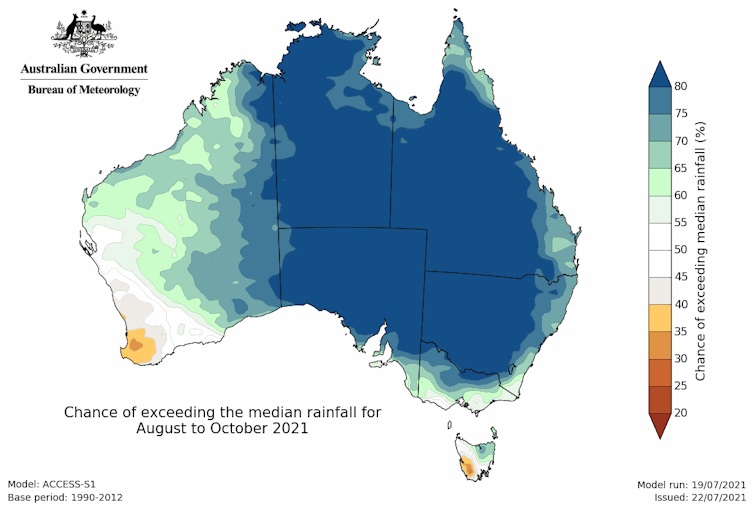

And last week, Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology officially declared there is a negative Indian Ocean Dipole — the first negative event in five years — known for bringing wet weather.

But what even is the Indian Ocean Dipole, and does it matter? Is it to blame for these events?

What Is The Indian Ocean Dipole?

The Indian Ocean Dipole, or IOD, is a natural climate phenomenon that influences rainfall patterns around the Indian Ocean, including Australia. It’s brought about by the interactions between the currents along the sea surface and atmospheric circulation.

It can be thought of as the Indian Ocean’s cousin of the better known El Niño and La Niña in the Pacific. Essentially, for most of Australia, El Niño brings dry weather, while La Niña brings wet weather. The IOD has the same impact through its positive and negative phases, respectively.

Positive IODs are associated with an increased chance for dry weather in southern and southeast Australia. The devastating Black Summer bushfires in 2019–20 were linked to an extreme positive IOD, as well as human-caused climate change which exacerbated these conditions.

Negative IODs tend to be less frequent and not as strong as positive IOD events, but can still bring severe climate conditions, such as heavy rainfall and flooding, to parts of Australia.

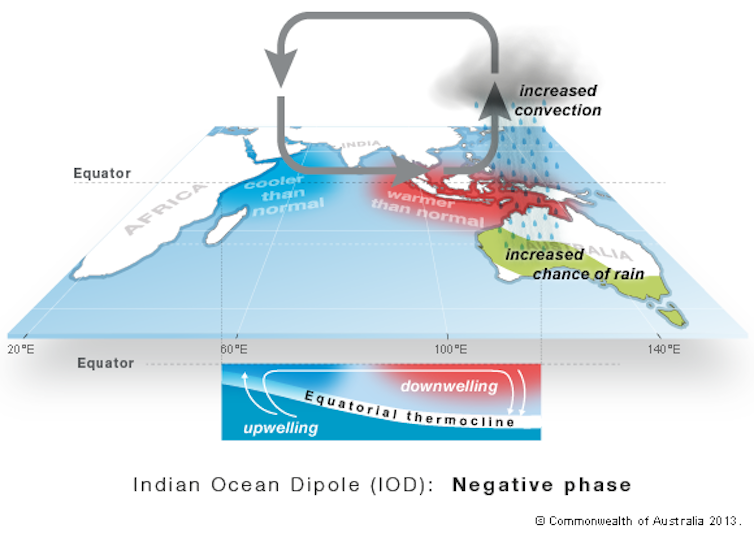

The IOD is determined by the differences in sea surface temperature on either side of the Indian Ocean.

During a negative phase, waters in the eastern Indian Ocean (near Indonesia) are warmer than normal, and the western Indian Ocean (near Africa) are cooler than normal.

Read more: Explainer: El Niño and La Niña

This causes more moisture-filled air to flow towards Australia, favouring wind pattern changes in a way that promotes more rainfall to southern parts of Australia. This includes parts of Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria, NSW and the ACT.

Generally, IOD events start in late autumn or winter, and can last until the end of spring — abruptly ending with the onset of the northern Australian monsoon.

Why Should We Care?

We probably have a wet few months ahead of us.

The negative IOD means the southern regions of Australia are likely to have a wet winter and spring. Indeed, the seasonal outlook indicates above average rainfall for much of the country in the next three months.

In southern Australia, a negative IOD also means we’re more likely to get cooler daytime temperatures and warmer nights. But just because we’re more likely to have a wetter few months doesn’t mean we necessarily will — every negative IOD event is different.

While the prospect of even more rain might dampen some spirits, there are reasons to be happy about this.

First of all, winter rainfall is typically good for farmers growing crops such as grain, and previous negative IOD years have come with record-breaking crop production.

In fact, negative IOD events are so important for Australia that their absence for prolonged periods has been blamed for historical multi-year droughts in the past century over southeast Australia.

Negative IOD years can also bring better snow seasons for Australians. However, the warming trend from human-caused climate change means this signal isn’t as clear as it was in the past.

It’s Not All Good News

This is the first official negative IOD event since 2016, a year that saw one of the strongest negative IOD events on record. It resulted in Australia’s second wettest winter on record and flooding in parts of NSW, Victoria, and South Australia.

The 2016 event was also linked to devastating drought in East Africa on the other side of the Indian Ocean, and heavy rainfall in Indonesia.

Thankfully, current forecasts indicate the negative IOD will be a little milder this time, so we hopefully won’t see any devastating events.

Is The Negative IOD Behind The Recent Wet Weather?

It’s too early to tell, but most likely not.

While Perth is experiencing one of its wettest Julys on record, the southwest WA region has historically been weakly influenced by negative IODs.

Negative IODs tend to be associated with moist air flow and lower atmospheric pressure further north and east than Perth, such as Geraldton to Port Hedland.

Outside of Australia, there has been extensive flooding in China and across Germany, Belgium, and The Netherlands.

It’s still early days and more research is needed, but these events look like they might be linked to the Northern Hemisphere’s atmospheric jet stream, rather than the negative IOD.

The jet stream is like a narrow river of strong winds high up in the atmosphere, formed when cool and hot air meet. Changes in this jet stream can lead to extreme weather.

What About Climate Change?

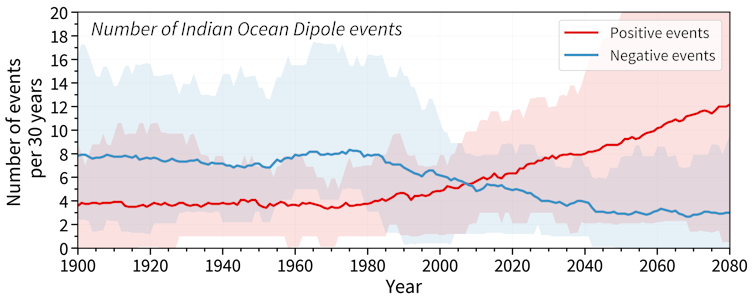

The IOD — as well as El Niño and La Niña — are natural climate phenomena, and have been occurring for thousands of years, before humans started burning fossil fuels. But that doesn’t mean climate change today isn’t having an effect on the IOD.

Read more: Why drought-busting rain depends on the tropical oceans

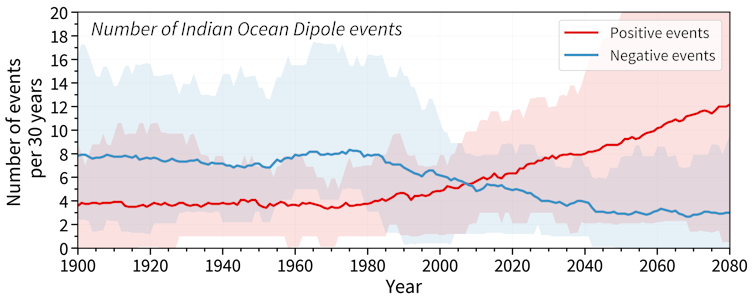

Scientific research is showing positive IODs — linked to drier conditions in eastern Australia — have become more common. And this is linked to human-caused climate change influencing ocean temperatures.

Climate models also suggest we may experience more positive IOD events in future, including increased chances of bushfires and drought in Australia, and fewer negative IOD events. This may mean we experience more droughts and less “drought-breaking” rains, but the jury’s still out.

When it comes to the recent, devastating floods overseas, scientists are still assessing how much of a role climate change played.

But in any case, we do know one thing for sure: rising global temperatures from climate change will cause more frequent and severe extreme events, including the short-duration heavy rainfalls associated with flooding, and heatwaves.

To avoid worse disasters in our future, we need to cut emissions drastically and urgently.

Nicky Wright, Research Fellow, University of Sydney; Andréa S. Taschetto, Associate Professor, UNSW, and Andrew King, ARC DECRA fellow, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Backflip Threatens National Standards

- A safe, continuous and step free path of travel from the street entrance and/or parking area to a dwelling entrance that is level.

- At least one, level (step-free) entrance into the dwelling.

- Internal doors and corridors that facilitate comfortable and unimpeded movement between spaces.

- A toilet on the ground (or entry) level that provides easy access.

- A bathroom that contains a hobless shower recess.

- Reinforced walls around the toilet, shower and bath to support the safe installation of grabrails at a later date.

- Stairways designed to reduce the likelihood of injury and also enable future adaptation.

Overcoming Adversity: Tess Lloyd's Insight For Year 12s

I'm reaching out because much like me trying to compete at the Tokyo Games, your year 12 is filled with uncertainty and unforeseen challenges due to Covid-19.Things just aren't going the way we planned, and while your teachers, families and the government are doing all they can to keep school as normal as possible, it doesn't stop us all from feeling a little wobbly at times and isolated from our friends and what is normal.Hey, I know what it's like. When I was your age, I was involved in a serious sailing accident, one which turned my life upside down and altered my plans for year 12.I'll save you the gory details, but in short: our boat was hit by a windsurfer, my crewmate pulled me from the water unconscious, I was taken to hospital – things were pretty dire – I underwent brain surgery, had nine screws and plates put in my head and was put into a medically induced coma.After the accident I had to learn to walk, talk and sail again. I ended up having to do my year 12 over two years, so while all my friends had graduated, I was still left studying. Not fun. As you can imagine, this brought with it great uncertainty.It was a tough time. So much uncertainty made me questions myself – it got me down from time to time.You are living through historic times, we are all, and while there is uncertainty, I know from my experiences that great things can come from adversity.Would I be the athlete I am today without the accident that changed my Year 12? Would I have achieved my childhood dream, and would it have been as special, if I hadn't gone through what I did?I don't know, but what I do know, is we all have greatness in us. We are all tougher than we imagined, and I want to encourage you to embrace adversity and adapt in times of uncertainty.I have no doubt you all will be incredibly successful in all you do, but as you live through the day to day, remember you are sharing the journey.Adversity adds to the triumph and brings out courage we never imagined we had.

More Time To Prepare For HSC

- Extend the hand in date for all major projects by two weeks. The hand-in date for Industrial Technology has been extended by four weeks

- Reschedule Drama performance exams to run from 6 to 17 September

- Music performance exam continue as scheduled, running from 30 August to 10 September

- Reschedule the written exams to begin one week later on 19 October with HSC results out on 17 December.

HSC Online Help

Stay Healthy - Stay Active: HSC 2021

Updated Advice For HSC Students

- Your school will advise you about arrangements for trial HSC exams.

- HSC students in Greater Sydney continue to be able to access school to prepare for the HSC where they cannot do so from home, including to use specialist equipment to work on major projects or rehearse for performance exams.

- As per broader NSW Health advice, HSC students in Greater Sydney are asked to learn from home where possible.

- All HSC students must follow COVID safe practices at school, including wearing a mask.

- The COVID illness/misadventure process is available for students whose ability to work on their major project or performance has been significantly impacted by COVID-19 restrictions.

After Dark Photo Competition: Northern Beaches

The Northern Beaches are one of the best places in Sydney to view the night sky and appreciate this wonderful asset.

The Northern Beaches are one of the best places in Sydney to view the night sky and appreciate this wonderful asset.Details

- Land – manmade and/or natural formations, wildlife, flora or fauna

- Sea – waterways, beaches, or marine areas, sea life

- Sky – aspects of the night sky, moon, starscapes, clouds or wildlife

- Junior – under 16 years featuring any one of these categories.

- Entry fees are $20 for the first category entered and $10 for each subsequent category entered.

- Up to six entries per category are permitted.

- Fees should be paid by the PayPal gateway on the entry website. Credit and debit cards can be used on this gateway.

- If entry payments are not received by the deadline, then the submitted entries will not be accepted for judging.

- Entries will be accepted only from Australian residents of the Commonwealth of Australia and its Territories.

- There will be two sections of entry – General and Junior (18 or younger)

- There will be three categories of entry for the General Section; Portraying the night time environment featuring Land, Sea or Sky.

- The Junior Section is for photographers 18 years old or younger and will have one open category.

- All entries must be taken within the Northern Beaches LGA and must be taken between sunset and sunrise.

- Images can be taken at any time of the year on or after 1 September 2019.

- The top 5 images of each category will be judged by the organising committee and will be hung at the Studio, Careel Bay Marina for general public display.

- Photographers represented in the top 5 images of each category will be notified that they are in the top 20 images (15 September 17:00 AEST).

- There is a limit of six (6) entries per category per photographer.

- In the case of images with multiple authors, the instigator of the image will be considered to be the principal author and the one who “owns” the image. The principal author MUST have performed the majority of the work to produce the image. All authors MUST be identified and named in the entry form along with their contributions to the production of the image.

- Entries must be in digital form and will be accepted ONLY through submission via the dedicated website at: afterdark.myphotoclub.com.au

- To preserve anonymity, the submitted image files should not contain identifying metadata.

- For judging purposes, still images must be submitted as JPG files with the longest side having a dimension no greater than 4,950 pixels in Adobe 1998 colour space.

- All photographs must have been taken no more than 2 years before the closing date of entry.

- Entry fees are $20 for the first entry and $10 each subsequent entry. Fees should be paid by the PayPal gateway on the entry website. Credit and debit cards can be used on this gateway.

- If entry payments are not received by the deadline, then the submitted entries will not be accepted for judging.

- Photographers of the top 20 images (5 in each category) will be notified 15 September and images printed, framed and hung by the organising. Artists may choose to pay $55 for this service to be undertaken on their part or undertake printing and framing at their own cost. Images must be ready for hanging 17:00 (AEST) 29 September 2021.

- Images will be listed on sale during the exhibition at the artist’s discretion. $100 of the sale will be donated to the charity the Australasian Dark Sky Alliance.

- Winners for the Land Scape, Sea Scape, Sky Scape and Youth entry will be announced Thursday 30th September 2021.

- People’s choice will confirmed by popular vote throughout the exhibition and will be announced on Saturday 30 October, 2021.

- Submissions close at 24:00 (AEST) on Wednesday, 1 September 2021. No entries will be accepted past this date.

- All winners should make an effort to attend the presentation of the awards on 30 September 2021

- The winning entries will be exhibited for the entire Exhibition After Dark, at the Studio, Careel Bay Marina between 30 September and 2 November, 2021.

- Permission to reproduce entries for publication to promote the competition and exhibitions and dark sky-related events and activities on the northern beaches will be assumed as a condition of entry. The copyright of the image remains with the author, and we will try to ensure that the author is credited where the image is used.

- All entries must be true images, faithfully reflecting and maintaining the integrity of the subject. Entries made up of composite images taken at different times and/or at different locations and/or with different cameras will not be accepted. Image manipulations that produce works that are more “digital art” than true astronomical images, will be deemed ineligible. If there is any doubt about the acceptability of an entry, then the competition organisers should be contacted, before the entry is submitted, for adjudication on the matter at the following email address: marnie@darkskytraveller.com.au

- If after the judging process, an image is subsequently determined to have violated the letter and/or the spirit of the rules, then that image will be disqualified. Any prizes consequently awarded for that image must be returned to the competition organisers.

- The competition judges reserve the right to reject any entry that, in the opinion of the judges, does not meet the conditions of entry or is unsuitable for public display. The judges’ decisions will be final.

- Submission of an entry implies acceptance of all the conditions of entry and the decisions of the competition judges.

- Entries Open: 24:00 (AEST) Sunday, 11 July 2021

- Entries Close: 24:00 (AEST) Wednesday, 1 September 2021

- Top 20 announced: 17:00 Wednesday, 15 September 2021

- Photography bump in: Midday Wednesday 29 September 2021

- Exhibition Launch and Presentation of Awards: Thursday 30 September 2021

- Bump out – 2 November 2021

- Category Winner: An image deemed to be the best in that category as judged by the judging panel.

- “The People’s Choice”: This will be judged by gathering votes obtained in the exhibition venue, and online.

- Category Winner: $200 – to each of the image deemed to be the best in each of the four (4) category.

- “The People’s Choice”: $200 – will be judged by gathering votes obtained in the exhibition venue, and online.

2021 Crikey! Magazine Photography Competition

Time To Dance!

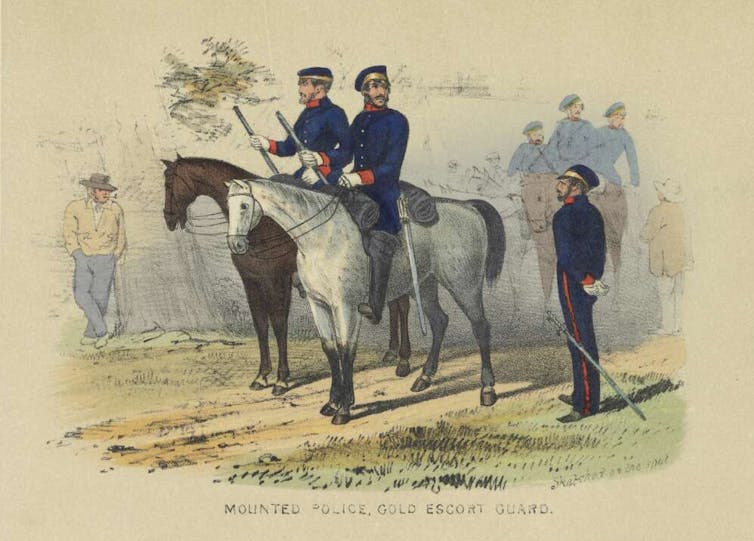

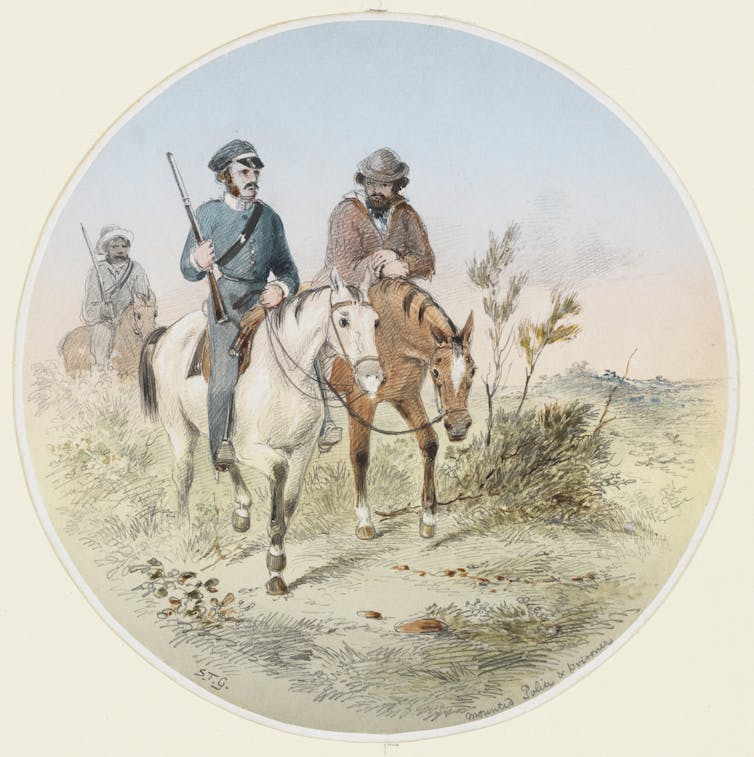

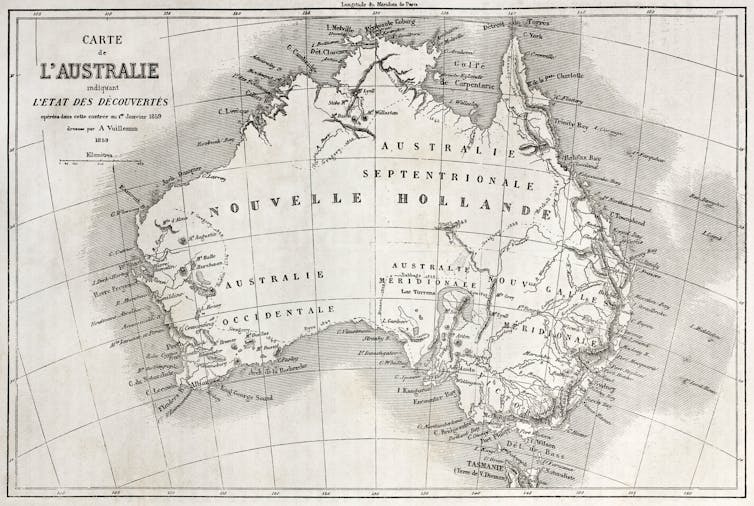

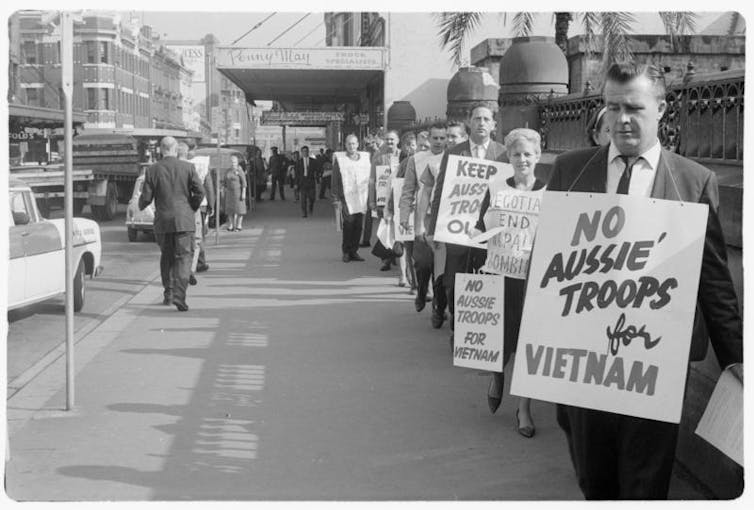

From colonial cavalry to mounted police: a short history of the Australian police horse

Stephen Gapps, University of Newcastle and Angus Murray, University of NewcastleAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and/or images of deceased people.

Images of mounted police contending with anti-lockdown protesters on the weekend have now gone viral around the world. In fact, mounted police have a long history in Australia.

They have certainly been used as a method of crowd control at countless demonstrations in living memory — from anti-war protests to pro-refugee rallies and everything in between.

But the history of mounted police in Australia goes much deeper.

Read more: Enforcing assimilation, dismantling Aboriginal families: a history of police violence in Australia

Mounted Reconnaissance And Messengers

In early colonial Australia, horses were at a premium. In the 1790s, policing of convicts and bushrangers in the confined region of the Sydney basin was conducted on foot by night watchmen, constables and the colonial military.

By 1801, the then Governor King formed a Body Guard of Light Horse for dispatching his messages to the interior and as a useful personal escort.

By 1816, at the height of the Sydney Wars of Aboriginal resistance, the numbers of horses in the colony had grown.

Their importance as mounted reconnaissance and for use by messengers was critical to Governor Macquarie’s infamous campaign, which ended in the Appin Massacre of April 17, 1816.

The Horse As A Key Element Of Occupation

Along with firearms and disease, the horse was a key element in occupying Aboriginal land and controlling the largely convict workforce on the frontier.

In the early 1820s, west of the Blue Mountains, the use of horses in the open terrain of the Bathurst Plains was critical in capturing escaped convicts and bushrangers, as well as defending remote outstations against attacks from Wiradjuri people.

Early intrusions into Wiradjuri land were not so much by British colonists, but by the animals they brought with them. In what is now recognised as “co-colonisation”, cattle and sheep did a lot of the hard yards for the British, often well before they arrived in Aboriginal lands.

In 1817, Surveyor General John Oxley thought he was well beyond the limits of settlement when, as he wrote:

to our great surprise we found the distinct marks of cattle tracks [that] must have strayed from Bathurst, from which place we were now distant in a direct line between eighty and ninety miles.

From A Colonial Cavalry To Mounted Police

During the first Wiradjuri War of Resistance between 1822 and 1824, calls were made to the colonial authorities for the formation of a civilian “colonial cavalry” to assist the beleaguered and overstretched military forces. My (Stephen Gapps) forthcoming book, developed in consultation with Wiradjuri community members in central west region of NSW, The Bathurst War, looks in deeper detail at this period.

It was hoped colonial farmers would be their own first line of defence against Aboriginal warrior raids on sheep and cattle stations.

Governor Brisbane wrote to London that in 1824 a mounted force was becoming “daily more essential [for the] vital interests of the of the Colony”.

But by August that year, heavily armed and mounted settlers, overseers and their armed convict workers had decimated Wiradjuri resistance before a formal cavalry militia was established.

After possibly hundreds of Wiradjuri people had been massacred by heavily armed and mounted settlers, a “Horse Patrol” was created in 1825, which soon formally became the Mounted Police.

The Mounted Police were critical during a spree of bushranging soon after — a largely unanticipated side-effect of arming of convict stockworkers to defend themselves against Wiradjuri attacks in 1824.

By the 1830s, the force had proved useful as a highly mobile quasi-military unit in combating Aboriginal resistance as well as bushranging.

As the colony continued to expand with an insatiable desire for running cattle and sheep on Aboriginal lands, three regional divisions were based at Bathurst, Goulburn and Maitland.

After conflict between colonists and Gamilaraay warriors on the Liverpool Plains, commander Major Nunn led a Mounted Police detachment on a two-month campaign around the Gwydir and Namoi Rivers, resulting in the Waterloo Creek Massacre on January 26, 1838. Armed colonists soon followed suit, ending in the Myall Creek Massacre in June that year, where colonists killed at least 28 Aboriginal people (possibly more).

The Mounted Police’s military functions came with heavy expenses, which included uniforms, equipment and barracks. During the 1840s, a Border Police force of ex-convicts equipped only with a horse, a gun and rations was created and attached to Commissioners of Crown Lands.

It was funded by a tax on squatters (whose interests they protected) and proved a much cheaper policing option for the frontier.

The Native Mounted Police

By 1850 the “Mounted Police” were disbanded. Another relatively cheap and what proved to be a tragic, if remarkably successful, option had been found — the creation of a “Native Mounted Police” force of Aboriginal men with British officers.

The troopers were provided with uniforms, guns and rations. By the 1860s, particularly in Queensland, the main problem on the frontier was not policing colonists but stopping Aboriginal resistance. So arming Aboriginal fighters was part of a tried and tested British method of exploiting existing hostilities by rewarding those who collaborated and punishing those who resisted.

As Bogaine Spearim, Gamilaraay and Kooma man, activist and creator of the podcast Frontier War Stories has noted, the Queensland Native Mounted Police (NMP) were not only feared by bushrangers such as Ned Kelly, but known for their violence toward the Aboriginal population of Queensland.

The NMP united incredible bush skills with military capability. Their legacy has been the focus of a recent project by Australian researchers Lynley Wallis, Heather Burke and colleagues.

The Role Of Animals In Colonisation And Policing

From 1850, the colonial police force (and then from 1862, the NSW Police force) incorporated mounted police as mobile units in mostly remote locations.

But they also found them useful in urban areas, especially with growing numbers of strikes, political disturbances, protests and riots in the rapidly industrialising cities in the late 19th century.

The use of horses in crowd control has a long history in policing, which itself has a long history in warfare. Among the other issues this presents, we might also consider horses’ long suffering histories of being placed in the front lines of conflict.

Like the inexorable march of sheep and cattle as part of the invasion of Aboriginal lands, understanding the role of animals in colonisation and policing is crucial to a broader understanding of Australian history.

Read more: Make no mistake: Cook’s voyages were part of a military mission to conquer and expand ![]()

Stephen Gapps, Conjoint Lecturer, University of Newcastle and Angus Murray, PhD student, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Choosing your senior school subjects doesn’t have to be scary. Here are 6 things to keep in mind

This is the first article in a series providing school students with evidence-based advice for choosing subjects in their senior years.

From about August each year, young people in year 10 go through a round of interviews to close in on their subject selections for years 11 and 12.

They’re given a portfolio full of reading materials. They may also attend vibrant careers markets to get helpful information. The principal and heads of the year give presentations, and occasionally a VIP guest speaker will arrive.

Somewhere at this point, my sobbing daughter had cried: “I’m growing up too quickly!” She’d been told a complex story about ATARs, prerequisites and options for her career path, all with the solemn authority about the importance of making wise decisions.

Studies have shown students experience anxiety around choosing subjects that relate to their desired career path. Nothing as serious as this will have happened in most children’s lives before now.

What if they don’t know what they want to do? Or worse, what if they make a mistake in their subject choices?

The good news is, there is not much need to worry. Choices you make now about your subjects don’t need to have a severe impact on your future.

There are some myths about senior schooling all kids and parents need to know. Here are six of them.

Myth 1: You Need An ATAR To Go To University

There are several pathways to university — an ATAR is only one of them.

The federal education department reports there are significant intakes for courses that don’t require an ATAR. A 2020 report says the share of university offers for applicants with no ATAR or who were non-year 12 applicants was 60.5% in 2020. This was up from 60.1% in 2019.

Some courses, like engineering, normally require an ATAR of somewhere around the mid 80s. But you could also get in through having done a VET certificate or diploma. RMIT, for instance, offers up to two years of credit to transfer from TAFE into an undergraduate degree.

Read more: Your ATAR isn't the only thing universities are looking at

There are many alternative pathways described by most institutions on their websites. Curtin University has a helpful journey finder for students without a competitive ATAR.

A year 12 student, expecting not to gain an ATAR, who is not studying English or doesn’t expect to gain a 50 scaled rank for English, has at least three pathways into Curtin — sitting the Special Tertiary Admissions Test, doing a course at Curtin College, and using a portfolio for assessment.

Curtin also has a UniReady Enabling Program. This is a short course of 17 weeks. Completing the course means you will fulfil Curtin’s minimum admission criteria of a 70 ATAR. Many universities have similar types of preparatory pathways.

Myth 2: Your Senior Subjects Majorly Influence Your Career

With all the disruption we’re experiencing, technical and social, we actually don’t have any idea what types of careers will be available in the future. Industry advice bodies, like the National Skills Commission, recommend students choose subjects that suit their interest and skill set, rather than to prepare for a specific future career.

Reports show today’s 15-year-olds will likely change employers 17 times and have five different careers through their working life. Many of their career may have very little, if any, connection to the senior subjects they took at school.

Read more: Can government actually predict the jobs of the future?

A 2018 report by industry body Deloitte Access Economics showed 72% of employers “demanded” communication skills when hiring and that transferable skills, such as as teamwork, communication, problem-solving, innovation and emotional judgement, “have become widely acknowledged as important in driving business success”.

This can include subjects like music, dance, debating and theatre will teach the exact skills employers value the most.

Myth 3: You Should Do ‘Hard’ Subjects To Get A High ATAR

All subjects are hard if you lack interest or ability. Students are unlikely to do well if they are unhappy and unmotivated.

Research shows being motivated will improve how well you do in something. But academic performance is better associated with internal motivation (such as liking something) than external (like the drive for an ATAR).