inbox and environment news:Issue 507

August 22 - 28, 2021: Issue 507

Time Of Ngoonungi

Powerful Owl Tree Hollow

Sick Turtles Coming Ashore

What's Happening To Our Frogs?: Attend Zoom Meeting To Find Out How You Can Help Out

Dead, shrivelled frogs are unexpectedly turning up across eastern Australia. We need your help to find out why

Over the past few weeks, we’ve received a flurry of emails from concerned people who’ve seen sick and dead frogs across eastern Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland.

One person wrote:

About a month ago, I noticed the Green Tree Frogs living around our home showing signs of lethargy & ill health. I was devastated to find about 7 of them dead.

Another wrote:

We previously had a very healthy population of green tree frogs and a couple of months ago I noticed a frog that had turned brown. I then noticed more of them and have found numerous dead frogs around our property.

And another said she’d seen so many dead frogs on her daily runs she had to “seriously wonder how many more are there”.

So what’s going on? The short answer is: we don’t really know. How many frogs have died and why is a mystery, and we’re relying on people across Australia to help us solve it.

Why Are Frogs Important?

Frogs are an integral part of healthy Australian ecosystems. While they are usually small and unseen, they’re an important thread in the food web, and a kind of environmental glue that keeps ecosystems functioning. Healthy frog populations are usually a good indication of a healthy environment.

They eat vast amounts of invertebrates, including pest species, and they’re a fundamental food source for a wide variety of other wildlife, including birds, mammals and reptiles. Tadpoles fill our creeks and dams, helping keep algae and mosquito larvae under control while they too become food for fish and other wildlife.

But many of Australia’s frog populations are imperilled from multiple, compounding threats, such as habitat loss and modification, climate change, invasive plants, animals and diseases.

Although we’re fortunate to have at least 242 native frog species in Australia, 35 are considered threatened with extinction. At least four are considered extinct: the southern and northern gastric-brooding frogs (Rheobatrachus silus and Rheobatrachus vitellinus), the sharp-snouted day frog (Taudactylus acutirostris) and the southern day frog (Taudactylus diurnus).

A Truly Unusual Outbreak

In most circumstances, it’s rare to see a dead frog. Most frogs are secretive in nature and, when they die, they decompose rapidly. So the growing reports of dead and dying frogs from across eastern Australia over the last few months are surprising, to say the least.

While the first cold snap of each year can be accompanied by a few localised frog deaths, this outbreak has affected more animals over a greater range than previously encountered.

This is truly an unusual amphibian mass mortality event.

In this outbreak, frogs appear to be either darker or lighter than normal, slow, out in the daytime (they’re usually nocturnal), and are thin. Some frogs have red bellies, red feet, and excessive sloughed skin.

The iconic green tree frog (Litoria caeulea) seems hardest hit in this event, with the often apple-green and plump frogs turning brown and shrivelled.

This frog is widespread and generally rather common. In fact, it’s the ninth most commonly recorded frog in the national citizen science project, FrogID. But it has disappeared from parts of its former range.

Other species reported as being among the sick and dying include Peron’s tree frog (Litoria peronii), the Stony Creek frog (Litoria lesueuri), and green stream frog (Litoria phyllochroa). These are all relatively common and widespread species, which is likely why they have been found in and around our gardens.

We simply don’t know the true impacts of this event on Australia’s frog species, particularly those that are rare, cryptic or living in remote places. Well over 100 species of frog live within the geographic range of this outbreak. Dozens of these are considered threatened, including the booroolong Frog (Litoria booroolongensis) and the giant barred frog (Mixophyes iteratus).

So What Might Be Going On?

Amphibians are susceptible to environmental toxins and a wide range of parasitic, bacterial, viral and fungal pathogens. Frogs globally have been battling it out with a pandemic of their own for decades — a potentially deadly fungus often called amphibian chytrid fungus.

This fungus attacks the skin, which frogs use to breathe, drink, and control electrolytes important for the heart to function. It’s also responsible for causing population declines in more than 500 amphibian species around the world, and 50 extinctions.

For example, in Australia the bright yellow and black southern corroboree frog (Pseudophryne corroboree) is just hanging on in the wild, thanks only to intensive management and captive breeding.

Curiously, some other frog species appear more tolerant to the amphibian chytrid fungus than others. Many now common frogs seem able to live with the fungus, such as the near-ubiquitous Australian common eastern froglet (Crinia signifera).

But if frogs have had this fungus affecting them for decades, why are we seeing so many dead frogs now?

Read more: A deadly fungus threatens to wipe out 100 frog species – here's how it can be stopped

Well, disease is the outcome of a battle between a pathogen (in this case a fungus), a host (in this case the frog) and the environment. The fungus doesn’t do well in warm, dry conditions. So during summer, frogs are more likely to have the upper hand.

In winter, the tables turn. As the frog’s immune system slows, the fungus may be able to take hold.

Of course, the amphibian chytrid fungus is just one possible culprit. Other less well-known diseases affect frogs.

To date, the Australian Registry of Wildlife Health has confirmed the presence of the amphibian chytrid fungus in a very small number of sick frogs they’ve examined from the recent outbreak. However, other diseases — such as ranavirus, myxosporean parasites and trypanosome parasites — have also been responsible for native frog mass mortality events in Australia.

It’s also possible a novel or exotic pathogen could be behind this. So the Australian Registry of Wildlife Health is working with the Australian Museum, government biosecurity and environment agencies as part of the investigation.

Here’s How You Can Help

While we suspect a combination of the amphibian chytrid fungus and the chilly temperatures, we simply don’t know what factors may be contributing to the outbreak.

We also aren’t sure how widespread it is, what impact it will have on our frog populations, or how long it will last.

While the temperatures stay low, we suspect our frogs will continue to succumb. If we don’t investigate quickly, we will lose the opportunity to achieve a diagnosis and understand what has transpired.

We need your help to solve this mystery.

Please send any reports of sick or dead frogs (and if possible, photos) to us, via the national citizen science project FrogID, or email calls@frogid.net.au.

Read more: Clicks, bonks and dripping taps: listen to the calls of 6 frogs out and about this summer ![]()

Jodi Rowley, Curator, Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Biology, UNSW, Australian Museum and Karrie Rose, Australian Registry of Wildlife Health - Taronga Conservation Society Australia, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We name the 26 Australian frogs at greatest risk of extinction by 2040 — and how to save them

Australia is home to more than 240 frog species, most of which occur nowhere else. Unfortunately, some frogs are beyond help, with four Australian species officially listed as extinct.

This includes two remarkable species of gastric-brooding frog. To reproduce, gastric-brooding frogs swallowed their fertilised eggs, and later regurgitated tiny baby frogs. Their reproduction was unique in the animal kingdom, and now they are gone.

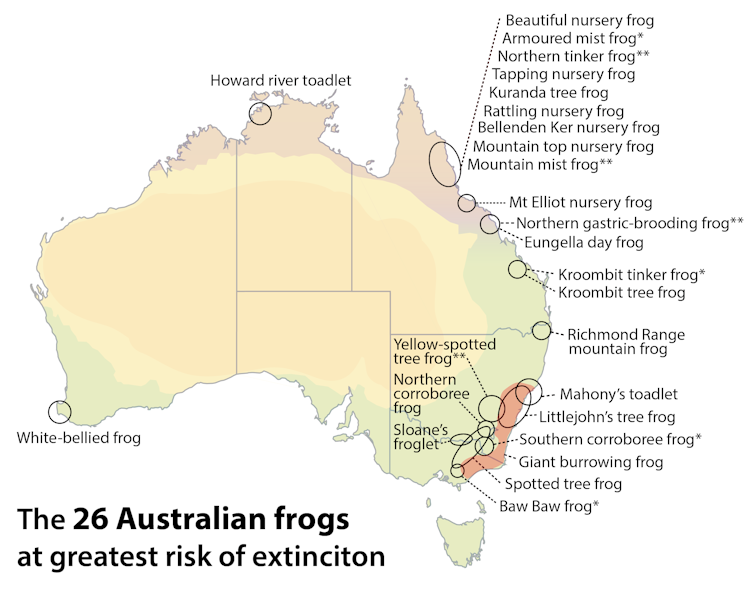

Our new study published today, identified the 26 Australian frogs at greatest risk, the likelihood of their extinctions by 2040 and the steps needed to save them.

Tragically, we have identified an additional three frog species that are very likely to be extinct. Another four species on our list are still surviving, but not likely to make it to 2040 without help.

The 26 Most Imperilled Frogs

The striking yellow-spotted tree frog (in southeast Australia), the northern tinker frog and the mountain mist frog (both in Far North Queensland) are not yet officially listed as extinct – but are very likely to be so. We estimated there is a greater than 90% chance they are already extinct.

The next four most imperilled species are hanging on in the wild by their little frog fingers: the southern corroboree frog and Baw Baw frog in the Australian Alps, and the Kroombit tinker frog and armoured mist frog in Queensland’s rainforests.

The southern corroboree frog, for example, was formerly found throughout Kosciuszko National Park in the Snowy Mountains. But today, there’s only one small wild population known to exist, due largely to an introduced disease.

Without action it is more likely than not (66% chance) the southern corroboree frog will become extinct by 2040.

What Are We Up Against?

Species are suffering from a range of threats. But for our most recent extinctions and those now at greatest risk, the biggest cause of declines is the amphibian chytrid fungus disease.

This introduced fungus is thought to have arrived in Australia in the 1970s and has taken a heavy toll on susceptible species ever since. Cool wet environments, such as rainforest-topped mountains in Queensland where frog diversity is particularly high, favour the pathogen.

The fungus feeds on the keratin in frogs’ skin — a major organ that plays a vital role in regulating moisture, exchanging respiratory gases, immunity, and producing sunscreen-like substances and chemicals to deter predators.

Another major emerging threat is climate change, which heats and dries out moist habitats. It’s affecting 19 of the imperilled species we identified, such as the white-bellied frog in Western Australia, which develops tadpoles in little depressions in waterlogged soil.

Climate change is also increasing the frequency, extent and intensity of fires, which have impacted half (13) of the identified species in recent years. The Black Summer fires ravaged swathes of habitat where fires should rarely occur, such as mossy alpine wetlands inhabited by the northern corroboree frog.

Invasive species impact ten frog species. For the spotted tree frog in southern Australia, introduced fish such as brown and rainbow trout are the main problem, as they’re aggressive predators of tadpoles. In northern Australia, feral pigs often wreak havoc on delicate habitats.

So What Can We Do About It?

We identified the key actions that can feasibly be implemented in time to save these species. This includes finding potential refuge sites from chytrid and from climate change, reducing bushfire risks and reducing impacts of introduced species.

But for many species, these actions alone aren’t enough. Given the perilous state of some species in the wild, captive conservation breeding programs are also needed. But they cannot be the end goal.

Captive breeding programs can not only establish insurance populations, they can also help a species persist in the wild by supplying frogs to establish populations at new suitable sites.

Boosting numbers in existing wild populations with captive bred frogs improves their chance of survival. Not only are there more frogs, but also greater genetic diversity. This means the frogs have a better chance of adapting to new conditions, including climate change and emerging diseases.

Our knowledge of how to breed frogs in captivity has improved dramatically in recent decades, but we need to invest in doing this for more frog species.

Finding And Creating Wild Refuges

Another vital way to help threatened frogs persist in the wild is by protecting, creating and expanding natural refuge areas. Refuges are places where major threats are eliminated or reduced enough to allow a population to survive long term.

For the spotted-tree frog, work is underway to prevent the destruction of frog breeding habitat by deer, and to prevent tadpoles being eaten by introduced predatory fish species. These actions will also help many other frog species as well.

The chytrid fungus can’t be controlled, but fortunately it does not thrive in all environments. For example, in the warmer parts of species’ range, pathogen virulence may be lower and frog resilience may be higher.

Chytrid fungus completely wiped out the armoured mist frog from its cool, wet heartland in the uplands of the Daintree Rainforest. But, a small population was found surviving at a warmer, more open site where the chytrid fungus is less virulent. Conservation for this species now focuses on these warmer sites.

This strategy is now being used to identify potential refuges from chytrid for other frog species, such as the northern corroboree frog.

No Time To Lose

We missed the window to save the gastric-brooding frogs, but we should heed their cautionary tale. We are on the cusp of losing many more unique species.

Decline can happen so rapidly that, for many species, there is no time to lose. Apart from the unknown ecological consequences of their extinctions, the intrinsic value of these frogs means their losses will diminish our natural legacy.

In raising awareness of these species we hope we will spark new action to save them. Unfortunately, despite persisting and evolving independently for millions of years, some species can now no longer survive without our help.

![]()

Graeme Gillespie, Honorary Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Conrad Hoskin, Lecturer/ABRS Postdoctoral Fellow, James Cook University; Hayley Geyle, Research Assistant, Charles Darwin University; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Nicola Mitchell, Associate Professor in Conservation Physiology, The University of Western Australia, and Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

It’s Magpie Swooping Season Once Again

- The most straightforward solution is to avoid locations where you know a magpie is swooping. Swooping only lasts a few weeks, so it is a minor inconvenience that could save you some blood (literally), sweat and tears.

- If you do get swooped, don’t panic and run away screaming (easier said than done, I know!). Instead, walk away quickly and calmly and maintain eye contact with them. They are less likely to swoop you if you are watching them. This also goes for cyclists—dismount and walk rather than continuing to ride

- Protect your eyes! Have a pair of sunglasses on hand any time you are going for a walk and especially in a park (same for kids as well).

- Pop an umbrella up if there is a swooping magpie around. Don’t wave it and antagonise the bird, but simply hold it above your head if a magpie is swooping.

- And of course, there are the old 'googly eyes on the ice cream container' and 'bike helmet with cable ties' tricks. Sometimes they work, sometimes they don’t.

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment August Newsletter, Forum & 2021 AGM

.jpg?timestamp=1627676810014)

Local Environmental Plan And Development Control Plan: Feedback Closes September 4

- permitting seniors housing, boarding houses and dual occupancies within 400m of (the) identified local centres of Avalon Beach, Newport, Warriewood, Belrose and Freshwater

- prohibiting dual occupancies in the R2 Low Density Residential zone (currently permitted under Pittwater and Manly LEPs)

- prohibiting attached, semi-detached and multi-dwelling housing in the R2 zone (currently permitted in the Manly LEP)

- standardising the size and placement rules for granny flats

- removing the floor space ratio controls for houses (currently required under the Manly LEP).

- improved controls for development near waterways, foreshores, wetlands and riparian lands;

- more water sensitive urban design and greater tree canopy;

- performance standards for net-zero carbon emission buildings;

- which water-related structures residents think are suitable adjoining waterways (NB: as well as noting that Action 1.8 of 'Towards 2040' proposes to expand the W2 zone to permit marina expansion)

- provisions to restrict large scale retail in small retail centres.

Echidna Breeding Season Commences

Reinstate The Marine Reserve From Rock Pool “Kiddies Corner” South Palm Beach: Petition

NSW Sustainability Awards Now Open For Entry

- NSW Net Zero Action Award

- NSW Biodiversity Award

- NSW Circular Transition Award

- NSW Clean Technology Award

- NSW Large Business Transformation Award

- NSW Small to Medium Business Award

- NSW Youth as our Changemakers Award

- Minister's Young Climate Champion Award

- NSW Clean Technology Award: Recognises outstanding initiatives by an organisation or organisations in collaboration that show- case efficient resources through renewable energy, low emissions technology, and appreciable pollution reduction (beyond compliance) of Australia's water, air, and land.

- NSW Biodiversity Award: Recognises outstanding initiatives by an organisation or organisations in collaboration that protect our habitat, flora and/or fauna to ensure Australia's ecosystems are secured and flourish for future generations.

- NSW Circular Transition Award: Recognises outstanding achievements in innovative design in waste and pollution systems and products, through to regenerating strategies. The award will go to a company that has adopted a technology, initiative or project that is helping the business move from a linear to a circular model.

- NSW Large Business Transformation Award: Recognises outstanding achievements that demonstrate business and values alignment with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals and by integrating sustainability principles and practices across business activities.

- NSW Youth as our Changemakers Award: Recognises young innovators aged between 18-35 years, who bring fresh perspectives, bold ideas and compelling initiatives that align with any or the multiple UN SDG's.

- NSW Net Zero Action Award: Recognises organisations, (company, business association, NGOs) that can demonstrate a tangible program or initiative that evidences transition toward a 1.5-Degree goal, through a publicly communicated net zero commitment, plus data, disclosures and investments to support it.

- NSW Small to Medium Business Award: Recognises outstanding achievements that demonstrate business and values alignment with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals and by integrating sustainability principles and practices across business activities.

- Minister's Young Climate Champion Award: The Minister's Young Climate Champion Award recognises young innovators aged under 18 years who bring bold ideas for a safe and thriving climate future that align with any of the UN SDGs. Young and passionate minds who have taken outstanding actions that benefit the sustainability of their communities and help address climate change will be showcased in this award, which is a celebration of young people with drive, commitment and a passion for sustainability and the environment.

Green Light To More Batteries And Improved Internet Coverage

- The installation of household-scale solar battery systems;

- The installation of NBN cables, speeding up its delivery;

- The repair or upgrading of existing technology;

- The installation of solar panels to power telecommunications facilities; and

- Site inspections, providing the location is not unnecessarily disturbed.

Empire Bay Marina Contamination Report Released

A detailed assessment of the former Empire Bay Marina site commissioned by the NSW Government has identified unacceptably high levels of contamination.

A detailed assessment of the former Empire Bay Marina site commissioned by the NSW Government has identified unacceptably high levels of contamination.Better Futures Forum August 17th

Logging Near Towns Must Stop To Mitigate Extreme Bushfire

- Mogo: Logging is active in Mogo State Forest 180A. There are plans to log Mogo State Forest 146A, which is only just over a kilometer from the town of Mogo itself. In the past few years, logging was completed in Mogo State Forest 144, 145 and 159 which directly border the town. The town was decimated during the Black Summer fires, and they have returned to logging surrounding forests.

- Brooman: Active logging is occurring in Shallow Crossing State Forest 212A and is proposed logging in South Brooman State Forest puts settlements in the Brooman area under threat.

- Eden: There are countless logging operations active or planned for forests south of Eden. During Black Summer bushfires, the fire burnt the Eden Chipmill and threatened the town. The intensity of these fires was extreme fire due to decades of logging.

- Nana Glen: This settlement was hard hit by the Black Summer fires. Logging is active nearby in Wedding Bells State Forest and Orara State Forest as well as Conglomerate State Forest. Logging has recently concluded in nearby Lower Bucca State Forest.

- Nambucca Heads: Compartments 12, 13 and 14 of Nambucca State Forest were logged last year, very close to the town.

Australia Must Slash Climate Pollution This Decade

Andrew Forrest Backs Away From Kimberley Frack Plan

Damming New Undertaking Reveals Extent Of Maules Creek Mine Illegality

Looming Gas Supply Shortfall For East Coast Market

BHP’s offloading of oil and gas assets shows the global market has turned on fossil fuels

John Quiggin, The University of QueenslandThe announcement by BHP, the world’s second-largest mining company, that it will shift its oil and gas assets into a joint venture with Australian outfit Woodside is a clear indication the “Big Australian” is getting out of the carbon-based fuel industry.

BHP has also been offloading thermal coal assets. It sold its share in the Cerrejon coal mine in Columbia to Glencore (the world’s biggest mining company) in June. It has written down the value of its Mt Arthur mine in Australia’s Hunter Valley while it looks for a buyer.

But if the oil wells, gas fields and coal mines are still there, what difference do these asset sales make? To answer this question, it is necessary to understand the broader logic of divestment, as championed by the divestment movement.

The Divestment Agenda

The immediate aim of the divestment movement is to end new investment in oil, gas and coal, with the ultimate aim of decarbonising the economy.

Over the past few years, with much prodding, financial institutions around the world have adopted divestment policies aiming to end or reduce their involvement in the carbon economy.

The initial focus has been on thermal coal, used in electricity generation. Coal mines and coal-fired power stations have been excluded almost entirely from global financial market. New developments now rely almost exclusively on finance from China, largely through the Belt and Road Initiative (and even this source is drying up).

In Australia, all the major banks and insurers, along with many superannuation funds, having now adopted policies to end their involvement with thermal coal. Now attention is turning to oil and gas.

Read more: BlackRock is the canary in the coalmine. Its decision to dump coal signals what's next

Divestment policies, like those of Westpac and the Commonwealth Bank, now commonly exclude new oil and gas projects (though there are often escape clauses for companies with policies “aligned with the Paris climate goals”).

The recognition that oil and gas has a limited future is reflected in the massive drop in “upstream” capital expenditure on exploration and development. Capital expenditure in 2020 fell below half the peak level of 2014, and only a modest recovery is expected after the pandemic.

BHP’s Choice

BHP and others therefore face a choice.

They can join the divestment movement, by selling carbon assets and focusing on other mining activities or on renewable energy.

Alternatively, they can become “pure play” coal, oil and gas businesses, profitable in the short run but increasingly excluded from investment portfolios and, ultimately, from normal financial transactions like banking and insurance.

This is the likely fate of the Woodside-BHP joint venture. The effect is similar to the “bad bank” structures created in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis to acquire non-performing loans and other dubious financial assets built up during the pre-2008 boom.

By offloading these assets, taking some losses in the process, the major global banks were able to recapitalise and resume their customary place at the centre of the financial universe.

Keeping Institutions Happy

The result will leave BHP shareholders with two separate holdings — one in BHP and one in the joint venture. The institutional shareholders who pushed for the divestment will now be able to dump these joint-venture shares and retain their holdings in BHP, which will (once the remaining coal assets are sold) now be safe from pressure for divestment.

Pressure didn’t come only from shareholders. Banks and other key institutional players were also key. Reports indicate the “all-stock” deal with Woodside was chosen precisely because it would have been impossible to arrange bank financing for the new venture.

Read more: How Bill McKibben's radical idea of fossil-fuel divestment transformed the climate debate

Banks will now be free to continue dealing with BHP, one of their biggest customers, while leaving the oil and gas venture to lower-tier lenders willing to take the financial and reputational risk.

A Justifiable Exit Strategy

It may be argued that, rather than disposing of its oil and gas assets, BHP should have taken action to shut them down.

This argument has been put forward both by environmentalists and Ivan Glasenberg, the chief executive of Glencore, the only major global miner to have chosen to stay in the coal business. Glasenberg has argued divestment is pointless because it simply makes fossil fuel assets “someone else’s issue”. Better to retain ownership of coal mines and phase them out gradually, he says.

Read more: Combating climate change – why investors should keep their shares in fossil fuel companies

Whether Glencore ever delivers on this strategy remains to be seen. But in light of the whole divestment agenda, BHP’s move is clearly more than a portfolio rearrangement.

For now, “pure play” oil, gas and coal companies can continue to generate profits. As global corporations, banks and insurers withdraw from the sector, however, the capacity of the remaining firms to resist regulatory and legal pressures to shut down will diminish.

Sooner or later, for example, it’s likely courts will find those responsible for carbon emissions liable for the damage caused by fires, sea level rise and other effects of climate change.

Without backing from banks and insurers, the costs of this litigation will fall directly on carbon-based corporations and their shareholders.

BHP, which was founded in 1885 and plans to be around for the long term, has seen the writing on the wall. It is getting out while it can.![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Some animals have excellent tricks to evade bushfire. But flames might be reaching more animals naive to the dangers

The new report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change paints a sobering picture of the warming climate in coming decades. Among the projections is an increase in fire weather, which will expose Earth’s landscapes to more large and intense megafires.

In our paper, published today in Global Change Biology, we considered what this fiery future might mean for the planet’s wildlife. We argue a lot can be learned by looking at how wildlife responds to a very different threat: predators.

Australia has seen the brutal consequences that occur when native wildlife is exposed to introduced predators. Australian animals have not evolved alongside introduced predators, such as cats and foxes, and some are what scientists call “predator naive” — they simply aren’t equipped with the evolutionary instincts to detect and respond to introduced predators before it’s too late.

Now, let’s take that idea and apply it to fires. Some animals have evolved excellent tricks to detect when a bushfire is nearby. But some areas where infernos were once rare are growing increasingly bushfire-prone, thanks to climate change. The wildlife in these spots may not have the evolutionary know-how to detect a fire before it’s too late.

Just as being “predator naive” has decimated Australian wildlife, will being “fire naive” wreak havoc on our native species?

Behaviour Forged In Fire

A growing list of studies show the tricks animals from fire-prone areas use to survive the flames.

Sleepy lizards have been shown to panic at the smell of burnt pastry, reed frogs leap away from the crackling sounds of fire, and bats and marsupials wake from torpor after smelling smoke.

And one study found that, when exposed to smoke, Mediterranean lizards from fire-prone areas reacted more strongly than Mediterranean lizards from areas where fire was rare.

These studies show some animals can recognise the threat of fire, and behave in a way that increases their chance of survival. Those that can are more likely to live through fire and pass on those abilities to their offspring.

That’s where the parallels between fire and predation become striking — and potentially worrying.

Reading The Cues

It’s well known predators and prey are in an ongoing evolutionary race to outmanoeuvre one another.

One tool prey draw upon to avoid becoming predator food is to recognise cues — such as smells, sights and sounds — that indicate a predator is lurking nearby. Once they do, prey can change their behaviour to minimise the risk of becoming dinner.

Decades of research has shown that when prey evolve alongside a predator, they can become highly adept at recognising their predator’s cues, such as a scent markings or territorial calls.

But what about animals that haven’t evolved alongside these lethal threats?

When a new predator enters an ecosystem, prey that have not evolved with it can be naive to its cues. They might fail to recognise the threat implied by the new predator’s scents, signs, or sounds, placing them at substantial risk.

This “predator naivety” helps explain why introduced predators are global drivers of extinction. Naive prey just don’t hear, smell, or see them coming.

Read more: There's no end to the damage humans can wreak on the climate. This is how bad it's likely to get

Which Species Are ‘Fire Naive’?

Research on how animals respond to fire cues has focused on animals from fire-prone regions, probably because that’s where you’d expect to find the strongest responses. But more research is needed about animals from regions that rarely burn.

Do these animals also recognise the cues of fire as an approaching lethal threat?

Do they have finely tuned behaviours that help them survive fire?

Are they “fire naive”?

We don’t know. And that’s a worry because recent changes in global fire activity, triggered by a warming and drying climate, are seeing fires enter ecosystems long regarded as “fire-free”.

If they are naive to fire, species in these ecosystems might be more at risk than previously thought.

The Search For Fire Naivety

We urge researchers around the world to assess fire naivety of animals, particularly in areas experiencing a change in their fire regimes, such as from rare to frequent fire or increased fire severity.

Evidence suggests recognition of predator cues is at least partly genetic. It will be important to determine whether the capacity to recognise and respond to fire also has a genetic basis.

If those behaviours can be passed on from one generation to the next, then perhaps we could take fire-savvy individuals from fire-prone areas and place them into fire naive populations, in the hope their favourable behaviours will spread rapidly via genes passed onto their offspring. Scientists call this “targeted gene flow”.

As the world continues to warm and megafires rage across the globe, we will need all the knowledge and tools at our disposal to help avoid an acceleration of Earth’s biodiversity crisis.

Dale Nimmo, Associate Professor in Ecology, Charles Sturt University; Alex Carthey, Macquarie University Research Fellow, Macquarie University; Chris J Jolly, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Charles Sturt University, and Daniel T. Blumstein, Professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Snorkellers discover rare, giant 400-year-old coral – one of the oldest on the Great Barrier Reef

Snorkellers on the Great Barrier Reef have discovered a huge coral more than 400 years old which is thought to have survived 80 major cyclones, numerous coral bleaching events and centuries of exposure to other threats. We describe the discovery in research published today.

Our team surveyed the hemispherical structure, which comprises small marine animals and calcium carbonate, and found it’s the Great Barrier Reef’s widest coral, and one of the oldest.

It was discovered off the coast of Goolboodi (Orpheus Island), part of Queensland’s Palm Island Group. Traditional custodians of the region, the Manbarra people, have called the structure Muga dhambi, meaning “big coral”.

For now, Muga dhambi is in relatively good health. But climate change, declining water quality and other threats are taking a toll on the Great Barrier Reef. Scientists, Traditional Owners and others must keep a close eye on this remarkable, resilient structure to ensure it is preserved for future generations.

Far Older Than European Settlement

Muga dhambi is located in a relatively remote, rarely visited and highly protected marine area. It was found during citizen science research in March this year, on a reef slope not far from shore.

We conducted a literature review and consulted other scientists to compare the size, age and health of the structure with others in the Great Barrier Reef and internationally.

We measured the structure at 5.3 metres tall and 10.4 metres wide. This makes it 2.4 metres wider than the widest Great Barrier Reef coral previously measured by scientists.

Muga dhambi is of the coral genus Porites and is one of a large group of corals known as “massive Porites”. It’s brown to cream in colour and made of small, stony polyps.

These polyps secrete layers of calcium carbonate beneath their bodies as they grow, forming the foundations upon which reefs are built.

Muga dhambi’s height suggests it is aged between 421 and 438 years old – far pre-dating European exploration and settlement of Australia. We made this calculation based on rock coral growth rates and annual sea surface temperatures.

The Australian Institute of Marine Science has investigated more than 328 colonies of massive Porites corals along the Great Barrier Reef and has aged the oldest at 436 years. The institute has not investigated the age of Muga dhambi, however the structure is probably one of the oldest on the Great Barrier Reef.

Other comparatively large massive Porites have previously been found throughout the Pacific. One exceptionally large colony in American Samoa measured 17m × 12m. Large Porites have also been found near Taiwan and Japan.

Resilient, But Under Threat

We reviewed environmental events over the past 450 years and found Muga dhambi is unusually resilient. It has survived up to 80 major cyclones, numerous coral bleaching events and centuries of exposure to invasive species, low tides and human activity.

About 70% of Muga dhambi consisted of live coral, but the remaining 30% was dead. This section, at the top of the structure, was covered with green boring sponge, turf algae and green algae.

Coral tissue can die from exposure to sun at low tides or warm water. Dead coral can be quickly colonised by opportunistic, fast growing organisms, as is the case with Muga dhambi.

Green boring sponge invades and excavates corals. The sponge’s advances will likely continue to compromise the structure’s size and health.

We found marine debris at the base of Muga dhambi, comprising rope and three concrete blocks. Such debris is a threat to the marine environment and species such as corals.

We found no evidence of disease or coral bleaching.

Read more: The Great Barrier Reef is in trouble. There are a whopping 45 reasons why

‘Old Man’ Of The Sea

A Traditional Owner from outside the region took part in our citizen science training which included surveys of corals, invertebrates and fish. We also consulted the Manbarra Traditional Owners about and an appropriate cultural name for the structure.

Before recommending Muga dhambi, the names the Traditional Owners considered included:

- Muga (big)

- Wanga (home)

- Muugar (coral reef)

- Dhambi (coral)

- Anki/Gurgu (old)

- Gulula (old man)

- Gurgurbu (old person).

Indigenous languages are an integral part of Indigenous culture, spirituality, and connection to country. Traditional Owners suggested calling the structure Muga dhambi would communicate traditional knowledge, language and culture to other Indigenous people, tourists, scientists and students.

Read more: How Traditional Owners and officials came together to protect a stunning stretch of WA coast

A Wonder For All Generations

No database exists for significant corals in Australia or globally. Cataloguing the location of massive and long-lived corals can be benefits.

For example from a scientific perspective, it can allow analyses which can help understand century-scale changes in ocean events and can be used to verify climate models. Social and economic benefits can include diving tourism and citizen science, as well as engaging with Indigenous culture and stewardship.

However, cataloguing the location of massive corals could lead to them being damaged by anchoring, research and pollution from visiting boats.

Looking to the future, there is real concern for all corals in the Great Barrier Reef due to threats such as climate change, declining water quality, overfishing and coastal development. We recommend monitoring of Muga dhambi in case restoration is needed in future.

We hope our research will mean current and future generations care for this wonder of nature, and respect the connections of Manbarra Traditional Owners to their Sea Country.

Read more: Not declaring the Great Barrier Reef as 'in danger' only postpones the inevitable ![]()

Adam Smith, Adjunct Associate Professor, James Cook University; Nathan Cook, Marine Scientist , James Cook University, and Vicki Saylor, Manbarra Traditional Owner, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

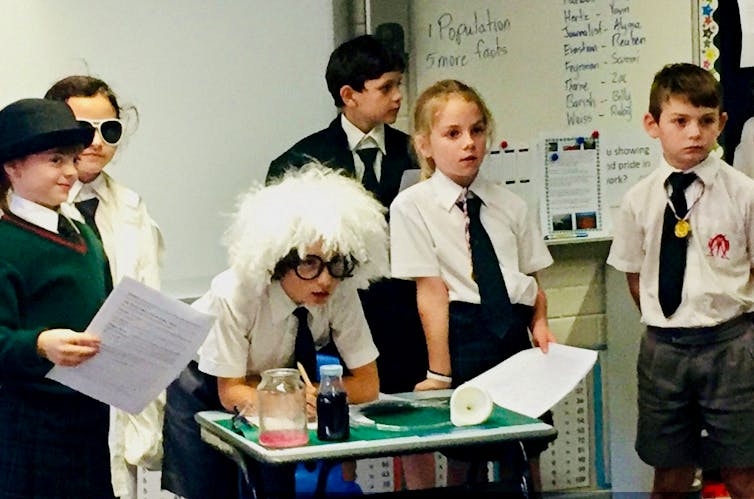

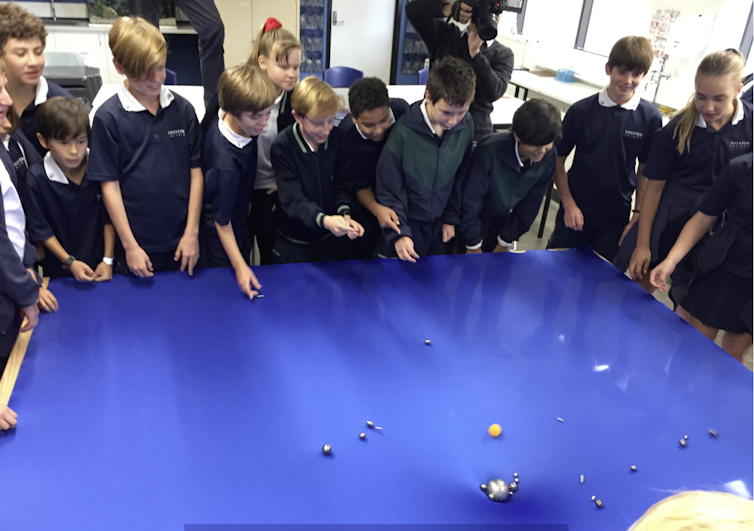

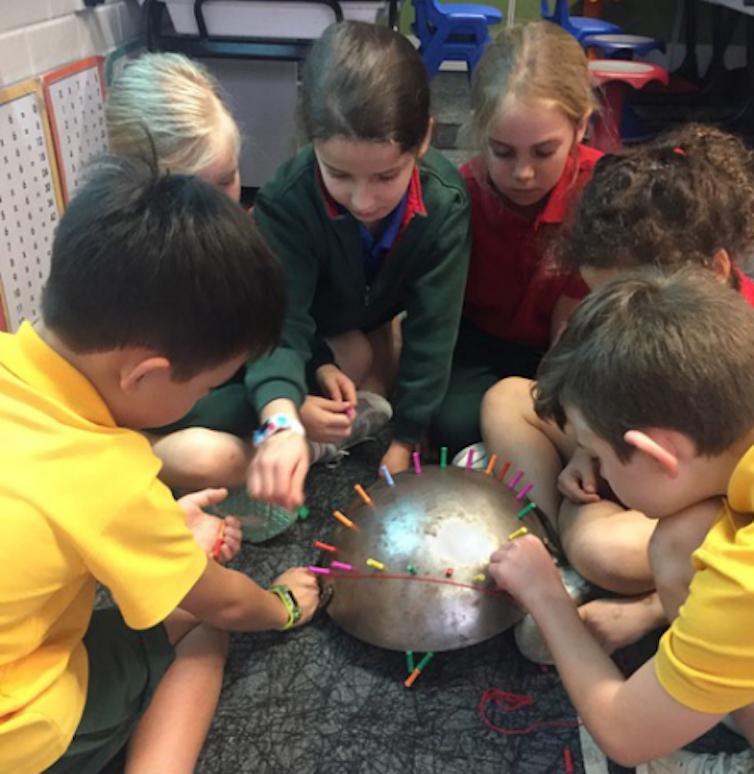

1 in 2 primary-aged kids have strong connections to nature, but this drops off in teenage years. Here’s how to reverse the trend

Parents and researchers have long suspected city kids are disconnecting from nature due to technological distractions, indoor lifestyles and increased urban density. Limited access to nature during COVID-19 lockdowns has heightened such fears.

In fact, “nature-deficit disorder” has become a buzzword, driving concerns about children’s well-being and their ability to understand and care for the natural world.

Yet, there’s been surprisingly little investigation to directly test whether a disconnect exists between children and nature – and if it does, how this might affect their environmental behaviours. Our recent research, focused on Australian children in urban areas, sought to address this knowledge gap.

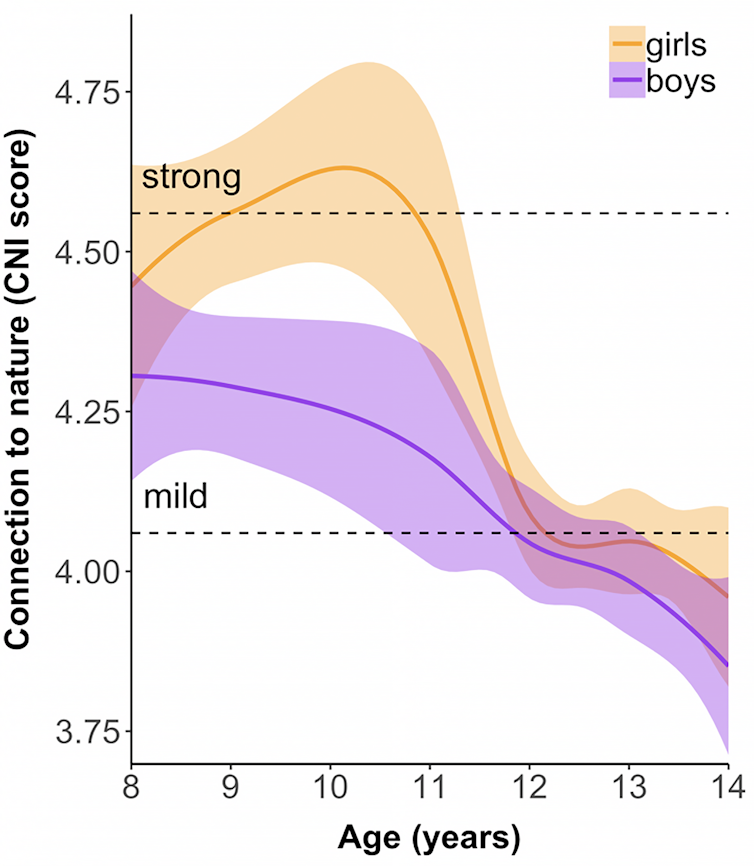

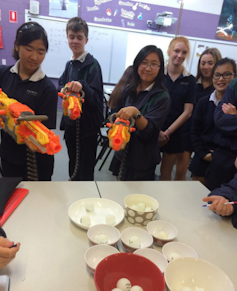

We found most younger children, especially girls, reported strong connections to nature and commitment to pro-environmental behaviours. But by their teenage years, many children have fallen out of love with nature. Understanding and reversing this trend is vital to tackling climate change, species loss and other grave environmental problems.

What We Did

Our research involved more than 1,000 students aged 8-14 years, attending 16 public schools across Sydney.

We measured the students’ connections to nature using a questionnaire which asked about their:

- enjoyment of nature

- empathy for creatures

- sense of oneness with nature

- sense of responsibility towards nature.

The survey also canvassed students’ current environmental behaviours, such as whether they recycled waste and conserved water and energy, as well as their willingness to:

- volunteer to help protect nature

- donate money to nature charities

- talk to friends and family about protecting nature.

Read more: Being in nature is good for learning, here's how to get kids off screens and outside

What We Found

Contrary to the conventional wisdom about nature-deficit disorder, we found one in two children aged 8 to 11 felt strongly connected to nature, despite living in the city. However, only one in five teens reported strong nature connections.

Children in the younger age group were also more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviours. For example, one in two were committed to saving water and energy on a daily basis, and two in three recycled each day.

Girls generally formed closer emotional connections to nature than boys did – a difference especially apparent in the final stage of primary school.

Importantly, girls differed from boys in their responses to questions about sensory stimulation. Girls particularly liked to see wildflowers, hear nature sounds and touch animals and plants. This finding echoes previous research which found motivation for sensory pleasure is greater in women than men.

Girls also felt greater empathy for nonhuman animals than did boys, even after accounting for differences in sensory experience.

Children with strong nature connections were much more likely to demonstrate pro-environmental behaviours. This helps explain why girls were more willing than boys to volunteer for nature conservation.

Read more: 'Nature doesn't judge you': how young people in cities feel about the natural world

What Does All This Mean?

These findings suggest parents, educators, and others seeking to “reconnect” youth with nature should focus on the transition between childhood and the teenage years.

Adolescence is a period of great change. Children move from primary to high school, switching peer groups and struggling through puberty. They gain independence and must adapt to a maturing brain.

Relationships with nature easily fall by the wayside when teens prioritise other aspects of their busy lives. In fact, evidence of the adolescent dip in nature connection is emerging across different cultures.

Educators and parents hoping to engage girls with nature might give them activities focused on sensory stimuli.

Girls’ greater empathy for nonhuman animals may result from societal norms that socialise girls to be more caring, cooperative, and empathetic than boys. Boys can be encouraged to have more empathy for nonhuman animals through activities focused on perspective-taking and role-playing.

Even when locked down at home, both girls and boys can cultivate empathy for animals and nourish their connections to nature by taking mindful note of their surroundings. Though cities can appear to be concrete jungles, they still contain urban wildlife, parks and other green elements.

Children Are The Future

Recent research has demonstrated that stronger nature connections are associated with improved health and wellbeing in children.

The benefits of connecting to nature should be distributed among youth in a just and equitable way. That means working with groups often marginalised in discussions about nature, such as ethnic minorities.

Conservation is increasingly reliant on young citizens forming meaningful connections with urban nature. Many environmental leaders, such as Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, are teenage girls.

Ensuring urban children maintain nature connections through adolescence is crucial to tackling Earth’s serious environmental problems. But it will also require more young people to confront the difficult realisation that the world’s climate is in crisis. For this, we need to develop better ways to help them cope.

Read more: How COVID-19 has affected overnight school trips, and why this matters ![]()

Ryan Keith, PhD Candidate, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney; Dieter Hochuli, Professor, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney; John Martin, Research Scientist, Taronga Conservation Society Australia & Adjunct lecturer, University of Sydney, and Lisa M. Given, Professor of Information Science, Centre for Design Innovation, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Meet the penis worm: don’t look away, these widespread yet understudied sea creatures deserve your love

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s new series introducing you to the unloved Australian animals that need our help.

Australia’s oceans are home to a startling array of biodiversity — whales, dolphins, dugongs and more. But not all components of Aussie marine life are the charismatic sort of animal that can feature in a tourism promotion, documentary, or conservation campaign.

The echiuran, or spoon worm, is one such animal. It is also called the penis worm.

There is no “Save the Echiuran Foundation” and no influencers selling merchandise to help save them. But these phallic invertebrates are certainly worth your time as integral and fascinating members — of Australia’s marine ecosystems.

What Makes Them So Interesting?

Taxonomists have classified echiurans in various different ways over the years, including as their own group of unique animals. Today, they’re considered a group of annelid worms that lost their segmentation. There is uncertainty about the exact number of species, but an estimate is 236.

The largest echiuran species reach over two metres in length! They have a sausage-shaped muscular trunk and an extensible proboscis (or tongue) at their front end. The trunk moves by wave like contractions.

Most echiurans live in marine sand and mud in long, U-shaped burrows, but some species also live between rocks. And they’re widespread, living up to 6,000 metres deep in the ocean all the way to the seashore, worldwide.

For example, one species, Ochetostoma australiense, is a common sight along sandy or muddy shorelines of Queensland and New South Wales, where it sweeps out of its burrow to collect and consume organic matter.

In fact, their feeding activities are something to behold, as they form a star-like pattern on the surface that extends from their burrow opening.

In another species, Bonella viridis, there is a striking difference between the males and females — the females are large (about 15 centimetres long) and the males are tiny (1-3 millimetres). Most larvae are sexually undifferentiated, and the sex they end up as depends on who’s around. The larvae metamorphose into dwarf males when they’re exposed to females, and into females when there are no other females present.

Males function as little more than a gonad and are reliant on females for all their needs.

Why They’re So Important

Echiurans perform a range of important ecological functions in the marine environment. They’re known as “ecosystem engineers” - organisms that directly or indirectly control the availability of resources, such as food and shelter, to other species. They do this mainly by changing the physical characteristics of habitats, for example, by creating and maintaining burrows, which can benefit other species.

Echiurans also have a variety of symbiotic animals, including crustaceans and bivalve molluscs, residing in their burrows. This means both animals have a mutually beneficial relationship. In fact, animals from at least eight different animal groups associate with echiuran burrows or rock-inhabiting echiurans — and this is probably an underestimate.

They’re beneficial for humans, too. Their burrowing and feeding habits aerate and rework sediments. Off the Californian coastline, for example, scientists noted how these activities reduced the impacts of wastewater on the seabed.

And they’re an important part of the diet of fish, including deepwater sharks such as the houndsharks, and species of commercial significance such as Alaskan plaice. Some mammals feast on them, too, such as the Pacific walrus in the Bering Sea, and the southern sea otter. In Queensland they also contribute to the diet of the critically endangered eastern curlew.

And many people eat them in East and Southeast Asia, where they’re chopped up and eaten raw, or used as a fermented product called gaebul-jeot. They (allegedly) taste slightly salty with sweet undertones.

The Unloved Billions

In Australia there is very little known about the biology and ecological roles of our echiuran fauna. This can also be said of many of Australia’s soft sediment marine invertebrates — the unloved billions.

We simply do not understand the population dynamics of even the large and relatively common echiuran species, and the human processes that threaten them. Given their role as ecosystem engineers, impacts to echiuran populations can flow on to other components of the seabed fauna, imperilling entire ecosystems.

We can, in general terms, predict that populations have suffered from the cumulative effects of urbanisation and coastal development. This includes loss and modification of habitats, and changes to water quality.

Populations may also be harmed by undersea seismic activities used in oil and gas exploration, but this is still poorly understood. Until recently, scientists knew only of the threats seismic activity posed to the hearing of whales and dolphins. It’s becoming clearer they can also affect the planet’s vital invertebrate species.

It is a dilemma for marine conservation when so little is known about a species that impacts cannot be reliably predicted, and where there is little or no impetus to improve this knowledge base.

We cannot simply presume an animal does not play an important role in an ecosystem because it lacks charisma.

In George Orwell’s novel Animal Farm, it was said “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others”. This remains abundantly true in terms of how humans view animals. But we must move away from this philosophy if we are to conserve and restore the planet’s fragile ecosystems.

Read more: Meet the broad-toothed rat: a chubby-cheeked and inquisitive Australian rodent that needs our help ![]()

Daryl McPhee, Associate Professor of Environmental Science, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Antarctic Flagship Nuyina On Her Way Here

Published August 20, 2021 by the Australian Antarctic Division

The Australian flag is flying on the nation’s new icebreaker RSV Nuyina (noy-yee-nah) for the first time after a ceremony in the Netherlands yesterday.

The event in Vlissingen was the official transfer of the ship from its European build team, marking the final stage of a 1900-day journey from contract signing to handover.

The design and build of the vessel has been a multi-national effort between the Australian Antarctic Division, the vessel operator Serco, Danish concept designers Knud E Hansen, Dutch engineering and detailed design team Damen, and the construction team at Damen Shipyards Galati in Romania.

RSV Nuyina will now undergo some final preparations ahead of its eight-week journey to its new home port of Hobart.

Nuyina is a Tasmanian Aboriginal word meaning ‘Southern Lights’. It is pronounced noy‑yee‑nah

The Southern Lights, also known as aurora australis, are an atmospheric phenomenon formed over Antarctica that reaches northwards to light up Australian – and particularly Tasmanian – skies. Australia’s current long serving icebreaker the RSV Aurora Australis bears the name of the Southern Lights, while the first Australian Antarctic ship, Sir Douglas Mawson’s SY Aurora was named after the same phenomenon.

The name RSV Nuyina continues this theme and forms another chapter in the story of connection between Australia and Antarctica, which has played out historically over the past century and geologically over a much longer time frame, continually watched over by the dancing green curtains of light.

RSV Nuyina recognises the long connection that Tasmanian Aboriginal people have with the evocative Southern Lights, to which they gave a name in their language. Tasmanian Aboriginal people were the most southerly on the planet during the last ice age. The adaptability and resilience of the Tasmanian Aborigines, who travelled in canoes to small islets in the Southern Ocean, are qualities emulated by our modern-day Antarctic expeditioners as they travel south.

The ship name was suggested by Australian schoolchildren through the ‘Name our Icebreaker’ competition, which was designed to engage Australian students and expand their understanding of Antarctica, its environment, climate, history and Australia’s role there.

Aboriginal language was the inspiration for a fifth of all the valid ship names submitted by Australian children. In many of the competition entries, students spoke of their desire for reconciliation and recognition of Australian Aborigines. Using an Aboriginal name for the new ship would acknowledge all the children who wanted to recognise the interwoven history of Aboriginal people and the great southern land – Antarctica.

Palawa kani is the language spoken by Tasmanian Aborigines today. It draws on extensive historical and linguistic research of written records and spoken recordings, and Aboriginal cultural knowledge. Not enough remains of any of the original six to 12 original languages to form a full language today, so palawa kani combines authentic elements from many of these languages. It flourishes in Aboriginal community life, with three generations of children having grown up learning it, and features increasingly in public life, including in gazetted Tasmanian place names.

Australia’s new Antarctic icebreaker RSV Nuyina was constructed in Damen Shipyards, Romania. Construction commenced in late May 2017, with a steel cutting ceremony, while a keel laying ceremony in August saw the first building-block of the ship consolidated in the drydock. Some earlier build images run here for you.

Siege Of The South 1931

Researchers Develop Real-Time Lyric Generation Technology To Inspire Song Writing: Have A Go!

NSW Sustainability Awards Now Open For Entry

- NSW Net Zero Action Award

- NSW Biodiversity Award

- NSW Circular Transition Award

- NSW Clean Technology Award

- NSW Large Business Transformation Award

- NSW Small to Medium Business Award

- NSW Youth as our Changemakers Award

- Minister's Young Climate Champion Award

- NSW Clean Technology Award: Recognises outstanding initiatives by an organisation or organisations in collaboration that show- case efficient resources through renewable energy, low emissions technology, and appreciable pollution reduction (beyond compliance) of Australia's water, air, and land.

- NSW Biodiversity Award: Recognises outstanding initiatives by an organisation or organisations in collaboration that protect our habitat, flora and/or fauna to ensure Australia's ecosystems are secured and flourish for future generations.

- NSW Circular Transition Award: Recognises outstanding achievements in innovative design in waste and pollution systems and products, through to regenerating strategies. The award will go to a company that has adopted a technology, initiative or project that is helping the business move from a linear to a circular model.

- NSW Large Business Transformation Award: Recognises outstanding achievements that demonstrate business and values alignment with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals and by integrating sustainability principles and practices across business activities.

- NSW Youth as our Changemakers Award: Recognises young innovators aged between 18-35 years, who bring fresh perspectives, bold ideas and compelling initiatives that align with any or the multiple UN SDG's.

- NSW Net Zero Action Award: Recognises organisations, (company, business association, NGOs) that can demonstrate a tangible program or initiative that evidences transition toward a 1.5-Degree goal, through a publicly communicated net zero commitment, plus data, disclosures and investments to support it.

- NSW Small to Medium Business Award: Recognises outstanding achievements that demonstrate business and values alignment with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals and by integrating sustainability principles and practices across business activities.

- Minister's Young Climate Champion Award: The Minister's Young Climate Champion Award recognises young innovators aged under 18 years who bring bold ideas for a safe and thriving climate future that align with any of the UN SDGs. Young and passionate minds who have taken outstanding actions that benefit the sustainability of their communities and help address climate change will be showcased in this award, which is a celebration of young people with drive, commitment and a passion for sustainability and the environment.

NESA Media Statement: HSC Major Projects

- Drama

- Textiles and Design

- Design and Technology

- Industrial Technology

- Visual Arts

- English Extension 2

- Music 1 (compositions)

- Music 2 and Extension (compositions and musicology)

- Society and Culture Personal Interest Project

More Time To Prepare For HSC

- Extend the hand in date for all major projects by two weeks. The hand-in date for Industrial Technology has been extended by four weeks

- Reschedule Drama performance exams to run from 6 to 17 September

- Music performance exam continue as scheduled, running from 30 August to 10 September

- Reschedule the written exams to begin one week later on 19 October with HSC results out on 17 December.

HSC Online Help Guide

Stay Healthy - Stay Active: HSC 2021

Star Trek And NASA: Celebrating The Connection

Aurora Australis Lights Up The Sky

UQ Leads Climate Action As First Australian University To Provide Carbon Literacy Training

Backing And Supporting Young Australians Through Our Youth Policy Framework

The Australian Government has today released the new Australian Youth Policy Framework, as part of ongoing and extensive consultation with young Australians.

The Australian Government has today released the new Australian Youth Policy Framework, as part of ongoing and extensive consultation with young Australians.Corinna's Career Head Start Thanks To TAFE NSW

TAFE Fee-Free Online Courses Available For 16-24 Year Olds

- live or work in NSW

- be an Australian Citizen, a permanent resident, a New Zealand citizen, or a humanitarian visa holder

- have left school

- aged from 16 - 24 inclusive, or

- in receipt of a Commonwealth Government benefit, or

- an unemployed person, or

- people expected to become unemployed

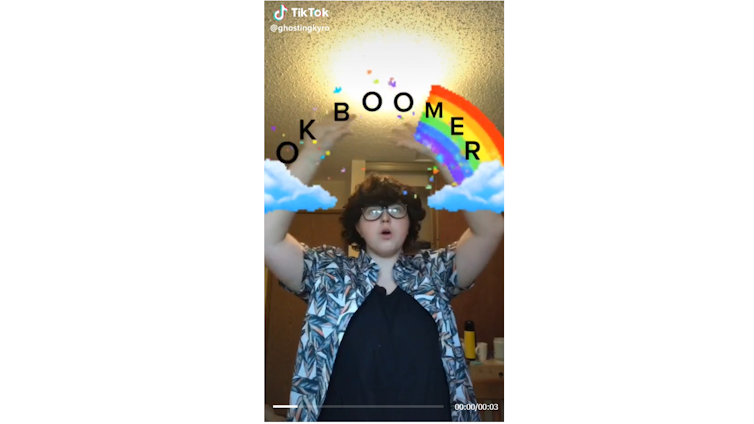

‘OK Boomer’: how a TikTok meme traces the rise of Gen Z political consciousness

The phrase “OK Boomer” has become popular over the past two years as an all-purpose retort with which young people dismiss their elders for being “old-fashioned”.

“OK Boomer” began as a meme in TikTok videos, but our research shows the catchphrase has become much more. The simple two-word phrase is used to express personal politics and at the same time consolidate an awareness of intergenerational politics, in which Gen Z are coming to see themselves as a cohort with shared interests.

What Does ‘OK Boomer’ Mean?

The viral growth of the “OK Boomer” meme on social media can be traced to Gen Z musician @peterkuli’s remix OK Boomer, which he uploaded to TikTok in October 2019. The song was widely adopted in meme creations by his Gen Z peers, who call themselves “Zoomers” (the Gen Z cohort born in 1997-2012).

In the two-minute sound clip @peterkuli distilled an already-popular sentiment into a two-word phrase, accusing “Boomers” (those born during the 1946–64 postwar baby boom) of being condescending, being racist and supporting Donald Trump, who was then US president.

Read more: How TikTok got political

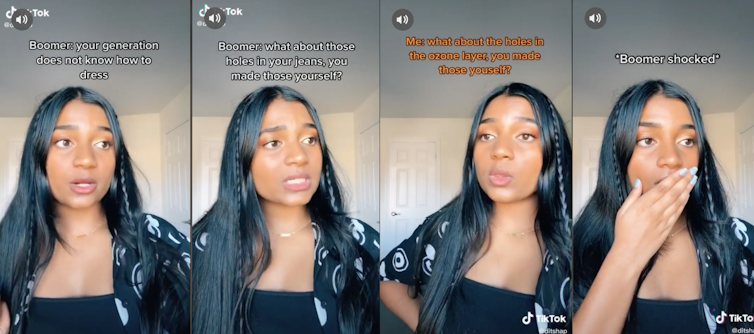

In essence, the “OK Boomer” meme emerged as a shorthand for Gen Z to push back against accusations of being a “fragile” generation unable to deal with hardship. But it has evolved into an all-purpose retort to older generations – but especially Boomers – when they dispense viewpoints perceived as presumptive, condescending or politically incorrect.

The meme arose in a wider context of “Boomer blaming”. In this view, the older generation has bequeathed Gen Z a host of societal issues, from Brexit and Trump to intergenerational economic inequality and climate change.

From ‘Big P’ Politics To ‘Everyday Politics’ And ‘Intergenerational Politics’

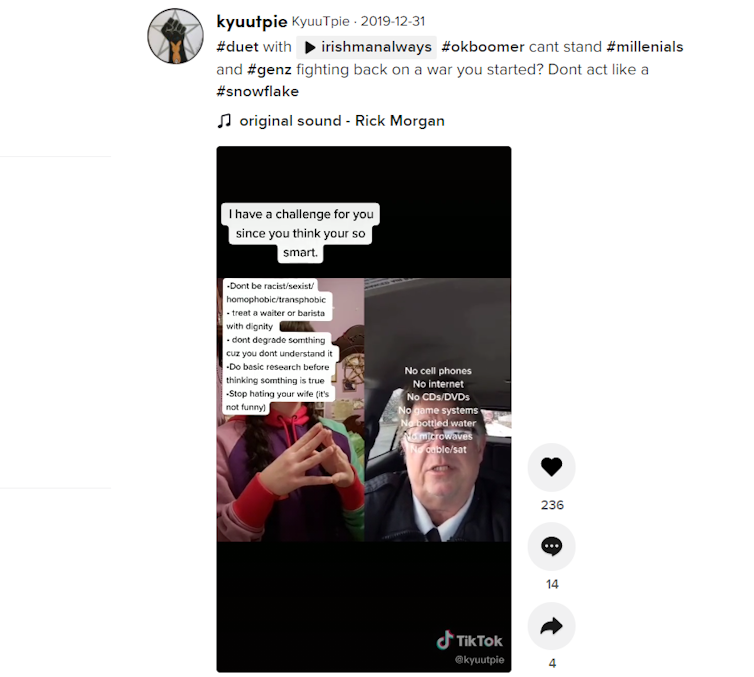

In our recent study on forms of online activism and advocacy on TikTok, we looked at 1,755 “OK Boomer” posts from 2019 and 2020 and found young people used the meme to engage in “everyday politics”.

Unlike “big P” politics – the work of governments, parliaments and politicians – “everyday politics” are political interests, pursuits and discussions framed through personal experiences.

On TikTok, young people construct and communicate their “everyday politics” by displaying their personal identities in highly personable ways, to demonstrate solidarity with or challenge beliefs and principles in society.

Read more: Baby boomers, Gen X, Millennials and Gen Z labels: Necessary or nonsense?

The “OK Boomer” meme and others like it allow young people to partake in a form of “intergenerational politics”. This is the tendency for people from a particular age cohort to form a shared political consciousness and behaviours, usually in opposition to the political attitudes of other groups. This is also reminiscent of when Boomers themselves encountered their own intergenerational politics in the countercultures of the 1960s and 1970s.

Doing ‘Politics’ On TikTok

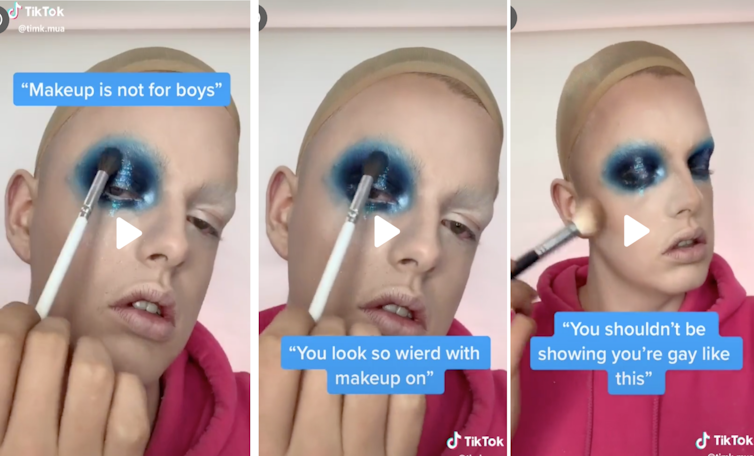

On TikTok, political expression can take the form of viral dances and audio memes. Young people use youthful parlance and lingo, pop cultural references and emojis to shape their collective political culture. In our study, we found three meme forms were especially popular:

- “Lip-sync activism” involved using lip-syncing to overlay one’s facial expressions and gestures over a soundtrack, either in agreement with or to challenge the lyrics and moral tone of a song.

- “Reacts via duets” made use of TikTok’s “duet” function for users to record their own original video clip alongside an original. This a compare-and-contrast style allows for juxtaposition (to oppose the original statement) or collaboration (to add to the original statement).

- “Craft activism” featured users displaying the creative processes and production of “OK Boomer”-themed objects and art, such as drawings, embroidery, and 3D printing.

Conveying Hardship And Tensions Through TikTok Memes

Memes have been used as collective symbols for community identification around specific political causes such as human rights advocacy, the #MeToo movement, and anti-racism campaigns during the pandemic.

Similarly, the “OK Boomer” meme has been deployed to discuss various controversial and contentious issues. This is often done in a reflexive way, using self-deprecating memes and ironic self-criticism to parody the excessively judgemental behaviour of others.

Around 40% of the posts we examined focused on young people’s lifestyles and well-being. These posts detailed how Gen Z are often criticised by Boomers for their lifestyle and appearance choices, such as unconventional career pathways and wearing ripped jeans.

Gen Z TikTokers also expressed frustration towards the dismissive attitude that Boomers adopted towards their mental health. These posts suggest Boomers blame depression or anxiety on stereotypical causes such as “spending too much time on the phone” or “not drinking enough water”.

About 10% of our sample demonstrated issues around gender and sexuality norms. In these cases, Gen Z felt their identity explorations and expressions were criticised by Boomers. Non-binary young people and those who did not follow gender norms for dress describe being “dress-coded” by Boomers, and queer and transgender young people report receiving rebukes for being open about their sexuality.

Why Do ‘OK Boomer’ Memes Matter?

Some scholars and commentators have criticised the “OK Boomer” meme as divisive and discriminatory against older people. However, as scholars of young people’s digital cultures we have found it more productive to understand the trend from the standpoint of Gen Z.

From this viewpoint, “OK Boomer” is a consequence of existing intergenerational discord, not its cause. Gen Z face growing threats such as climate change, political unrest, and generational economic hardship. Memes like “OK Boomer” are ways to express intergenerational everyday politics to consolidate a shared awareness of the perceived failure of the Boomers.

Read more: Generational war: a monster of our own making

Further, most of the personal stories told through “OK Boomer” TikToks were deployed by Gen Z when they felt under attack for their lifestyle choices, dress code, expressions of sexuality, or mental health struggles. Like many Boomers did in their own youths, members of Gen Z value freedom of expression and identity exploration.

The retort of “OK Boomer” offers a counter-reaction and expresses indignation. But at the same time it carries a sense of desperation for agency and personal space, as well as some attention and care.![]()

Crystal Abidin, Associate Professor & ARC DECRA Fellow, Internet Studies, Curtin University and Meg Jing Zeng, Senior research associate, University of Zurich

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Worth Noting: Get A Haircut & Get A Real Job - Boomers Vs. Gen. Z

‘The History of the Devil’ by Daniel Defoe; not quite the right book for a little girl,” said Mr. Riley, “How came it among your books, Tulliver?”Maggie looked hurt and discouraged, while her father said, “Why, it’s one o’ the books I bought at Partridge’s sale. They was all bound alike, it’s a good binding, you see, and I thought they’d be all good books. There’s Jeremy Taylor’s ‘Holy Living and Dying’ among ’em ; I read in it often of a Sunday.” (Mr. Tulliver felt somehow a familiarity with that great writer because his name was Jeremy); “and there ‘s a lot more of ’em, sermons mostly, I think ; but they ‘ve all got the same covers, and I thought they were all o’ one sample, as you may say. But it seems one mustn’t judge by th’ outside. This is a puzzlin’ world.

"We were at this place in Australia called the Black Marlin watching a couple of guys performing. We liked one of the songs and asked them who had written it. Birch and Avery were the guys who wrote it. This was at Lee Marvin's old hangout."Thorogood is a big fan of the late actor. "We dedicated a song to him. Some writer for the L.A. Times wrote a story that had some psychologist saying the song had a bad message. The writer called Lee about it, but Lee said the song was cool."

TikTok is partnering with a blockchain start-up. Here’s why this could be good news for artists

On August 17, TikTok announced it will partner with Audius, a streaming music platform, to manage its expansive internal audio library.

Audius was not the obvious choice for partnering with the short video giant. A digital music streaming start-up founded in 2018, it isn’t one of the major streaming services such as Apple Music or Spotify.

And, even more unusual, Audius is one of the first and only streaming platforms run on blockchain.

Remind Me, What Is Blockchain?

Blockchain is a technology that stores data records and transfers values with no centralised ownership.

Transaction data on these systems are stored as individual “blocks” that sequentially link together when connected by timestamps and unique identifiers to form “chains”.

For music, this means individual songs are assigned unique codes, and clear records are stored each time a song is played. It can also mean more streamlined and transparent payments.

Read more: Demystifying the blockchain: a basic user guide

Platforms like Spotify and Apple Music use a “pro-rata” model to pay artists. Under this system, artists get a cut of the platform’s overall monthly revenues generated from ads and subscription fees, as calculated by how many times their music was played.

The pro-rata model has been criticised by independent artists and analysts for maintaining a “superstar economy” in which the most popular artists claim a majority share of monthly revenue.

Facilitated by its blockchain system, Audius uses a “user-centric” model, where artists receive revenues generated by the individual users who stream their music directly.

That is, payments are generated for artists more directly from people streaming their songs.

While the biggest streaming players have refused to abandon pro-rata payments, Deezer — a French music streaming service with around 16 million monthly active users — has taken the first steps towards user-centric payments.

Now, it seems TikTok may be poised to follow.

And How Does TikTok Work?

At over 800 million monthly active users, TikTok is the world’s largest short video platform and has become a significant force in global music industries.

Once on TikTok, songs can be used as background for short videos — and can go viral.