Inbox and Environment News: Issue 508

August 29 - September 4, 2021: Issue 508

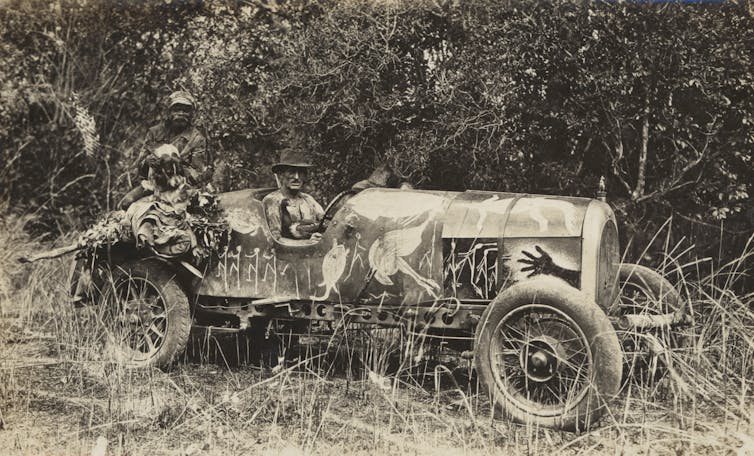

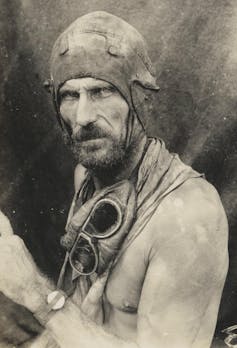

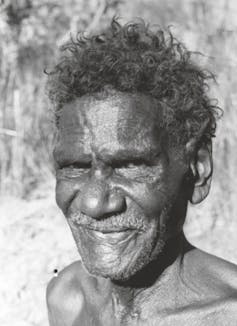

Time Of Ngoonungi

Local Environmental Plan And Development Control Plan: Feedback Closes September 4

- permitting seniors housing, boarding houses and dual occupancies within 400m of (the) identified local centres of Avalon Beach, Newport, Warriewood, Belrose and Freshwater

- prohibiting dual occupancies in the R2 Low Density Residential zone (currently permitted under Pittwater and Manly LEPs)

- prohibiting attached, semi-detached and multi-dwelling housing in the R2 zone (currently permitted in the Manly LEP)

- standardising the size and placement rules for granny flats

- removing the floor space ratio controls for houses (currently required under the Manly LEP).

- improved controls for development near waterways, foreshores, wetlands and riparian lands;

- more water sensitive urban design and greater tree canopy;

- performance standards for net-zero carbon emission buildings;

- which water-related structures residents think are suitable adjoining waterways (NB: as well as noting that Action 1.8 of 'Towards 2040' proposes to expand the W2 zone to permit marina expansion)

- provisions to restrict large scale retail in small retail centres.

Sick Turtles Coming Ashore

Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment August Newsletter, Forum & 2021 AGM

Australia has failed greater gliders: since they were listed as ‘vulnerable’ we’ve destroyed more of their habitat

In just five years, greater gliders — fluffy-eared, tree-dwelling marsupials — could go from vulnerable to endangered, because Australia’s environmental laws have failed to protect them and other threatened native species.

Our new research found that after the greater glider was listed as vulnerable to extinction under national environment law in 2016, habitat destruction actually increased in some states, driving the species closer to the brink. Now, they meet the criteria to be listed as endangered.

Despite this, the federal government has put forward a bill that would further weaken Australia’s environment laws.

If Australia wants to ditch its shameful reputation as a global extinction leader, our environmental laws must be significantly strengthened, not weakened.

Why Is The Greater Glider Losing Its Home?

At about the size of a cat, greater gliders are the largest gliding marsupial in the world, and can glide up to 100 metres through the forest canopy. They nest in the hollows of big old trees and, just like koalas, they mostly eat eucalypt leaves.

Greater gliders were once common throughout the forests of Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria. However, destructive practices, such as logging and urban development, have cut down the trees they call home. The rapidly warming climate and increasingly frequent and severe bushfires are also a major threat.

Together, these threats are causing the greater glider to rapidly disappear.

For our new study, we calculated the amount of greater glider habitat destroyed in the two years before the species was listed as vulnerable under Australia’s environment law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) Act. We then compared this to the amount of habitat destroyed in the two years after listing.

In Victoria, we measured the amount of habitat that was logged. In Queensland and NSW, we measured the amount of habitat cleared for all purposes, including logging, agriculture, and development projects.

What We Found

The amount of greater glider habitat logged in Victoria remained consistently high, with a total of 4,917 hectares logged before listing compared to 4,759 hectares after listing. And of all forest logged in Victoria after listing, more than 45% was mapped as greater glider habitat by the federal government, according to our research paper.

State-owned forestry company VicForests is responsible for the lion’s share of native forest logging in Victoria. The Conversation contacted VicForests to respond to the arguments in this article. A spokesperson said:

There are 3.7 million hectares of potential Greater Glider habitat in Victoria under the official habitat model. The most valuable areas of this habitat are set aside in conservation reserves that can never be harvested.

The total area harvested by VicForests in any year is around 0.04% of this total potential habitat.

In Queensland, habitat clearing increased by almost 300%, from a total of 3,002 hectares before listing compared to 11,838 hectares after listing. The amount of habitat cleared in NSW increased by about 5%, from a total of 15,204 hectares to 15,890 hectares.

We also quantified how much greater glider habitat was affected by the 2019-2020 Black Summer bushfires, and found approximately 29% of greater glider habitat was burnt. Almost 40% of this burnt at high severity, which means few gliders are likely to persist in, or rapidly return to, these areas.

As a result, earlier this year — just five years after listing — an assessment by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee found the greater glider is potentially eligible for up-listing from vulnerable to endangered.

Why Was Habitat Allowed To Be Cleared?

Development projects can take decades to be implemented after they’ve been approved under the EPBC Act. Therefore, a lot of the habitat cleared in NSW and Queensland was likely to have been approved before the greater glider was listed as vulnerable, and before the 2019-2020 bushfires.

Once a project is approved, it is not reassessed, even if a species becomes vulnerable and a wildfire burns much of its habitat.

This means the impact of clearing native vegetation can be far greater than when initially approved. It also means it can take many years after a species is listed until its habitat is finally safe.

In Victoria and parts of NSW, the forestry industry is allowed to log greater glider habitat under “regional forest agreements”. These agreements allow logging to operate under a special set of rules that bypasses federal environmental scrutiny under the EPBC Act.

The logging industry is required to comply only with state regulations for threatened species protection, which are are often inadequate.

Read more: A major report excoriated Australia's environment laws. Sussan Ley's response is confused and risky

In 2019, the Victorian government updated the protection measures for greater gliders in logged forests. However, these still allow logging of up to 60% of a forested area authorised for harvest, even when greater gliders are present at high densities.

The spokesperson for VicForests said the company prioritises live, hollow-bearing trees wherever there are five or more greater gliders per spotlight kilometre (a 1 kilometre stretch of forest surveyed with torches). But this level of protection is limited and is unlikely to halt greater glider decline, as the species is highly sensitive to disturbance.

In May 2020 the Federal Court found VicForests breached state environmental laws when they failed to implement protection measures and destroyed critically endangered Leadbeater’s possum and greater glider habitat.

Despite this, earlier this year, the Federal Court upheld an appeal by VicForests to retain their exemption from the EPBC Act. This ruling means VicForests will not be held accountable for destroying threatened species habitat, even when it is found in breach of state requirements.

The spokesperson for VicForests said the company takes sustainable harvesting seriously.

VicForests operations are subject to Victorian laws, and enforced by the Office of the Conservation Regulator (OCR) and Victorian courts when necessary. The recent federal court appeal decision has not changed that fact.

They add that VicForests surveys show greater gliders continue to persist in recently harvested areas, under its current practices.

VicForests has not seen any evidence that even a single Greater Glider has died as a result of our new harvesting approach.

The Government Isn’t Learning Its Lesson

The EPBC Act is currently undergoing a once in a decade assessment that considers how well it’s operating, with a recent independent review criticising the EPBC Act for no longer being fit for purpose. Our new research reinforces this, by showing the act has failed to protect one of Australia’s most iconic and unique animals.

And yet, the federal government wants to weaken the act further by implementing a streamlined model, which would rely on state governments to approve actions that would impact threatened species.

There’s a raft of reasons why this would be problematic.

Read more: Death by 775 cuts: how conservation law is failing the black-throated finch

For one, state environmental laws operate independently, and don’t consider what developments have been approved in other states. Cutting down trees may seem insignificant in certain areas, but without considering the broader impacts, many small losses can accumulate into massive declines, like a death by a thousand cuts.

As a case in point, despite the devastation of greater glider habitat from the Black Summer fires in NSW, the Queensland government have recently approved a new coal mine, which will destroy over 5,500 hectares of greater glider and koala habitat.

What Needs To Change?

The greater glider is edging towards extinction, but there is still no recovery plan for this iconic marsupial. Adding to this, new research suggests there are actually three species of greater glider we could be losing, rather than just one as was previously thought. Significant effort must be invested to create a clear plan for their recovery.

Because Australia has such a rich diversity of wildlife, we have a great responsibility to protect it. Australia must make important changes now to strengthen — not weaken — its environmental laws, before greater gliders, and many other species, are gone forever.![]()

Darcy Watchorn, PhD Candidate, Deakin University and Kita Ashman, Threatened Species & Climate Adaptation Ecologist, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As the world battles to slash carbon emissions, Australia considers paying dirty coal stations to stay open longer

A long-anticipated plan to reform Australia’s electricity system was released on Thursday. One of the most controversial proposals by the Energy Security Board (ESB) concerns subsidies which critics say will encourage dirty coal plants to stay open longer.

The subsidies, under a so-called “capacity mechanism”, would aim to ensure reliable energy supplies as old coal plants retire.

Major coal generators say the proposal will achieve this aim. But renewables operators and others oppose the plan, saying it will pay coal plants for simply existing and delay the clean energy transition.

So where does the truth lie? Unless carefully designed, the proposal may enable coal generators to keep polluting when they might otherwise have closed. This is clearly at odds with the need to rapidly cut greenhouse gas emissions and stabilise Earth’s climate.

Paying Coal Stations To Exist

The ESB provides advice to the nation’s energy ministers and comprises the heads of Australia’s major energy governing bodies.

Advice to the ministers on the electricity market redesign, released on Thursday, includes a recommendation for a mechanism formally known as the Physical Retailer Reliability Obligation (PRRO).

It would mean electricity generators are paid not only for the actual electricity they produce, which is the case now, but also for having the capacity to scale up electricity generation when needed.

Electricity prices on the wholesale market – where electricity is bought and sold – vary depending on the time of day. Prices are typically much higher when consumer demand peaks, such as in the evenings when we turn on heaters or air-conditioners. This provides a strong financial incentive for generators to provide reliable electricity at these times.

As a result of these incentives, Australia’s electricity system has been very reliable to date.

But the ESB says as more renewables projects come online, this reliability is not assured – due to investor uncertainty around when coal plants will close and how governments will intervene in the market.

Read more: IPCC report: how to make global emissions peak and fall – and what's stopping us

Under the proposed change, electricity retailers – the companies everyday consumers buy energy from – must enter into contracts with individual electricity generators to make capacity available to the market.

Energy authorities would decide what proportion of a generator’s capacity could be relied upon at critical times. Retailers would then pay generators regardless of whether or not they produce electricity when needed.

Submissions to the ESB show widespread opposition to the proposed change: from clean energy investors, battery manufacturers, major energy users and consumer groups. The ESB acknowledges the proposal has few supporters.

In fact, coal generators are virtually the only groups backing the proposed change. They say it would keep the electricity system reliable, because the rapid expansion of rooftop solar has lowered wholesale prices to the point coal plants struggle to stay profitable.

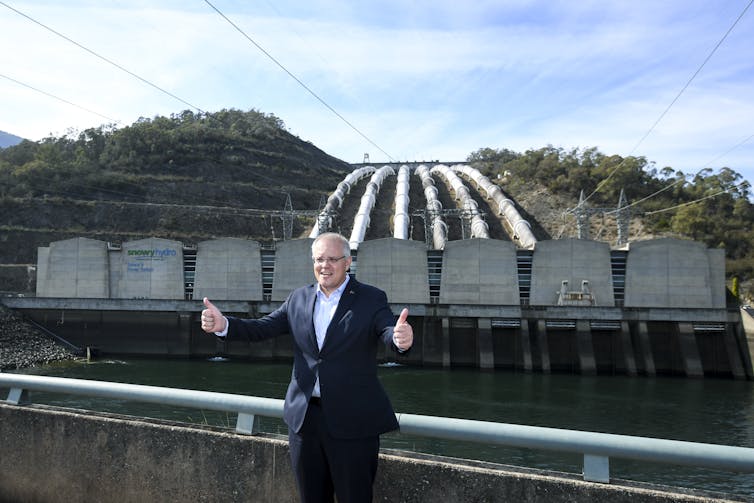

The ESB says the subsidy would also go to other producers of dispatchable energy such as batteries and pumped hydro. It says such businesses require guaranteed revenue streams if they’re to invest in new infrastructure.

A Questionable Plan

In our view, the arguments from coal generators and the ESB require greater scrutiny.

Firstly, the ESB’s suggestion that the existing market is not driving investment in new dispatchable generation is not supported by recent data. As the Australian Energy Market Operator recently noted, about 3.7 gigawatts of new gas, battery and hydro projects are set to enter the market in coming years. This is on top of 3.2 gigawatts of new wind and solar under construction. Together, this totals more than four times the operating capacity of AGL’s Liddell coal plant in New South Wales.

It’s also difficult to argue the system is made more reliable by paying dispatchable coal stations to stay around longer.

One in four Australian homes have rooftop solar panels, and installation continues to grow. This reduces demand for coal-fired power when the sun is shining.

The electricity market needs generators that can turn on and off quickly in response to this variable demand. Hydro, batteries and some gas plants can do this. Coal-fired power stations cannot – they are too slow and inflexible.

Coal stations are also becoming less reliable and prone to breakdowns as they age. Paying them to stay open can block investment in more flexible and reliable resources.

Critics of the proposed change argue coal generators can’t compete in a world of expanding rooftop solar, and when large corporate buyers are increasingly demanding zero-emissions electricity.

There is merit in these arguments. The recommended change may simply create a new revenue stream for coal plants enabling them to stay open when they might otherwise have exited the market.

Governments should also consider that up to A$5.5 billion in taxpayer assistance was allocated to coal-fired generators in 2012 to help them transition under the Gillard government’s (since repealed) climate policies. Asking consumers to again pay for coal stations to stay open doesn’t seem equitable.

The Ultimate Test

The nation’s energy ministers have not yet decided on the reforms. As usual, the devil will be in the detail.

For any new scheme to improve electricity reliability, it should solely reward new flexible generation such as hydro, batteries, and 100% clean hydrogen or biofuel-ready gas turbines.

For example, reliability could be improved by establishing a physical “reserve market” of new, flexible generators which would operate alongside the existing market. This generation could be seamlessly introduced as existing generation fails and exits.

The ESB has recommended such a measure, and pivoting the capacity mechanism policy to reward only new generators could be beneficial.

The Grattan Institute has also proposed a scheme to give businesses more certainty about when coal plant will close. Together, these options would address the ESB’s concerns.

This month’s troubling report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was yet another reminder of the need to dramatically slash emissions from burning fossil fuels.

Energy regulators, politicians and the energy industry owe it to our children and future generations to embrace a zero-emissions energy system. The reform of Australia’s electricity market will ultimately be assessed against this overriding obligation.

Tim Nelson, Associate Professor of Economics, Griffith University and Joel Gilmore, Associate Professor, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Drone Surveillance Leads To $270,000 In Penalties For Pollution Offences

Disbelief As Coal Mine Companies Issued Mere Cautions For Illegally Burying Hundreds Of Giant Tyres

“The investigation identified that all open-cut coal mines in this region had buried waste tyres that had been generated at each respective premises, without the necessary licence conditions, at various times between 2014-2020. The EPA has issued Official Cautions to all the open cut coal mines investigated.”

EPA Cautions Coal Mines For Burying Waste Tyres

Job Seekers Jump On The Header For A Record Harvest

Liberal And Labor Join Forces To Funnel Public Funds To Fracking Company

Whitehaven Wants More Coal But Isn’t Willing To Wait For Locals To Weigh In

Bushfire survivors just won a crucial case against the NSW environmental watchdog, putting other states on notice

This week was another big one in the land of climate litigation.

On Thursday, a New South Wales court compelled the state Environment Protection Authority (EPA) to take stronger action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It’s the first time an Australian court has ordered a government organisation to take more meaningful action on climate change.

The case challenging the EPA’s current failures was brought by a group of bushfire-affected Australians. The group’s president said the ruling means those impacted by bushfires can rebuild their homes, lives, and communities, with the confidence the EPA will also work to do its part by addressing emissions.

The group’s courtroom success shows citizens can play an important role in bringing about change. And it continues a recent trend of successful climate cases that have held government and private sector actors to account for their responsibility to help prevent climate-related harms.

Who Are The Bushfire Survivors?

Members of the group, the Bushfire Survivors for Climate Action, identify as survivors, firefighters and local councillors impacted by bushfires and the continued threat of bushfire posed by climate change.

Their stories paint a picture of devastating loss, and fear of what might be to come. One member, who lost her home, tells of harrowing hours looking for friends and family amid a dark, alien moonscape. Another, a volunteer firefighter, describes the smell of charred and burnt flesh and the silence of the incinerated forests that haunted him.

The group argues that because the NSW EPA is required, by law, to protect the environment through quality objectives, guidelines and policies, these instruments also need to cover greenhouse gas emissions.

Their reasoning is hard to fault: climate change is one of the environment’s most significant threats. In today’s world, you can’t protect the environment without addressing climate change.

To establish this point, the bushfire survivors presented the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was released while the trial was being heard. The report describes how the temperature rise in Australia could exceed the global average, and predicts increasingly hotter and drier conditions.

An Unperformed Duty

The EPA’s statutory duty to protect the environment was already known before the litigation began. That’s because the duty is contained within the EPA’s own legislation.

The EPA protects the environment from other types of pollutants by issuing environment protection licences, monitoring compliance, and imposing fines and clean-up orders. The bushfire survivors were seeking to force the EPA to address greenhouse gas emissions as well.

The EPA unsuccessfully tried to establish it is not required to address any specific environmental problem — i.e. climate change. And it argued that even if it is, it has already done enough.

But the court agreed with the bushfire survivors that the EPA’s instruments already in place aren’t sufficient, leaving the duty “unperformed”.

The court didn’t specify exactly how the EPA should remedy the fact it isn’t adequately addressing climate change, meaning the EPA can decide how it develops its own quality objectives, guidelines and policies, in a way that leads to fewer emissions. It is not the court’s job to make policy.

The EPA might, for example, target the highest-emitting industries and activities, via controls or caps on greenhouse gases.

Importantly, however, the court said the EPA doesn’t have to match its actions with a particular climate scenario, such as a global temperature rise of 1.5℃.

Other States On Notice

Although this ruling is specific to NSW, other state environment protection authorities also have legal objectives to protect the environment.

This case may cause other Australian environmental authorities to consider whether their regulatory approaches match what the law requires them to do. This might include a responsibility to protect the environment from climate change.

Another thing we know from the NSW case is that simply having policies and strategies isn’t enough.

The court made it clear aspirational and descriptive plans won’t cut the mustard if there’s nothing to “set any objectives or standards, impose any requirements, or prescribe any action to be taken to ensure the protection of the environment”.

The EPA tried to point to NSW’s Climate Change Framework and Net Zero Plan as a way of showing climate change action. But neither of these was developed by the EPA.

The EPA also presented documents it did develop, including a document about landfill guidelines, a fact sheet on methane, and a regulatory strategy highlighting climate change as a challenge for the EPA.

The court found these weren’t enough to address the threat of climate change and discharge the EPA’s duty, calling the regulatory strategy’s description of climate change “general and trite”.

An Australian First, But Not An Anomaly

Globally, climate litigation is playing a role in filling gaps in domestic climate governance. Cases in Europe, North and South America, and elsewhere have led to courts pushing governments to do more.

One of the world’s first major successful climate change cases, Massachusetts v EPA, was similar to the bushfire survivors’ case. Back in 2007, the state of Massachusetts, along with other US states, sued the federal US EPA. They were seeking to force regulatory action on greenhouse gas emissions, and a recognition of carbon dioxide as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act.

While the NSW case comes 14 years after the US case, there has been plenty of courtroom action in Australia in the meantime, with cases against the financial sector, government actors, and corporations.

In fact, on the same morning as the bushfire survivors’ case, a lawsuit was filed against oil and gas giant Santos in the Federal Court.

The Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility will argue statements made in Santos’s annual report are misleading and deceptive. These statements include that natural gas is a “clean fuel” and that it has a “clear and credible” plan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040.

Climate change is an inevitable problem, and one that will be costly. Lawsuits seeking to force action now aim to limit how great the costs will be down the track. By targeting those most responsible, they are a means of seeking justice.![]()

Laura Schuijers, Research Fellow in Environmental Law, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Judgment In Land And Environment Court 26 August 2021

NSW Sustainability Awards Now Open For Entry

- NSW Net Zero Action Award

- NSW Biodiversity Award

- NSW Circular Transition Award

- NSW Clean Technology Award

- NSW Large Business Transformation Award

- NSW Small to Medium Business Award

- NSW Youth as our Changemakers Award

- Minister's Young Climate Champion Award

- NSW Clean Technology Award: Recognises outstanding initiatives by an organisation or organisations in collaboration that show- case efficient resources through renewable energy, low emissions technology, and appreciable pollution reduction (beyond compliance) of Australia's water, air, and land.

- NSW Biodiversity Award: Recognises outstanding initiatives by an organisation or organisations in collaboration that protect our habitat, flora and/or fauna to ensure Australia's ecosystems are secured and flourish for future generations.

- NSW Circular Transition Award: Recognises outstanding achievements in innovative design in waste and pollution systems and products, through to regenerating strategies. The award will go to a company that has adopted a technology, initiative or project that is helping the business move from a linear to a circular model.

- NSW Large Business Transformation Award: Recognises outstanding achievements that demonstrate business and values alignment with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals and by integrating sustainability principles and practices across business activities.

- NSW Youth as our Changemakers Award: Recognises young innovators aged between 18-35 years, who bring fresh perspectives, bold ideas and compelling initiatives that align with any or the multiple UN SDG's.

- NSW Net Zero Action Award: Recognises organisations, (company, business association, NGOs) that can demonstrate a tangible program or initiative that evidences transition toward a 1.5-Degree goal, through a publicly communicated net zero commitment, plus data, disclosures and investments to support it.

- NSW Small to Medium Business Award: Recognises outstanding achievements that demonstrate business and values alignment with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals and by integrating sustainability principles and practices across business activities.

- Minister's Young Climate Champion Award: The Minister's Young Climate Champion Award recognises young innovators aged under 18 years who bring bold ideas for a safe and thriving climate future that align with any of the UN SDGs. Young and passionate minds who have taken outstanding actions that benefit the sustainability of their communities and help address climate change will be showcased in this award, which is a celebration of young people with drive, commitment and a passion for sustainability and the environment.

Green Light To More Batteries And Improved Internet Coverage

- The installation of household-scale solar battery systems;

- The installation of NBN cables, speeding up its delivery;

- The repair or upgrading of existing technology;

- The installation of solar panels to power telecommunications facilities; and

- Site inspections, providing the location is not unnecessarily disturbed.

Ordinary people, extraordinary change: addressing the climate emergency through ‘quiet activism’

Across the world, people worried about the impacts of climate change are seeking creative and meaningful ways to transform their urban environments. One such approach is known as “quiet activism”.

“Quiet activism” refers to the extraordinary measures taken by ordinary people as part of their everyday lives, to address the climate emergency at the local level.

In the absence of national leadership, local communities are forging new responses to the climate crisis in places where they live, work and play.

As we outline in a book released this month, these responses work best when they are collaborative, ongoing and tailored to local circumstances.

Here are three examples that show how it can be done.

Climate For Change: A Tupperware Party But Make It Climate

Climate for Change is a democratic project in citizen-led climate education and participation.

This group has engaged thousands of Australians about the need for climate action — not through public lectures or rallies, but via kitchen table-style local gatherings with family and friends.

As they put it:

We’ve taken the party-plan model made famous by Tupperware and adapted it to allow meaningful discussions about climate change to happen at scale.

Their website quotes “Jarrod”, who hosted one such party, saying:

I’ve been truly surprised by the lasting impact of my conversation amongst friends who were previously silent on the issue – we are still talking about it nine months on.

Climate for Change has published a “climate conversation guide” to help people tackle tricky talks with friends and family about climate change.

It has also produced a resource on how to engage your local MP on climate change.

EnviroHouse: Hands-On Community Education

EnviroHouse is a not-for-profit organisation based in Western Australia committed to local-scale climate action through hands-on community education and engagement projects, such as:

facilitating workshops on energy efficiency

visiting schools on request to provide sustainability services

collecting seeds to grow thousands of she-oaks, paperbarks and rushes along the eroded Maylands foreshore in Perth

teaching workshops on composting, worm farming and bokashi techniques to community members

giving talks on sustainable living

running a home and workplace energy and water auditing program.

Climarte: Arts For A Safe Climate

Climarte is a group that

collaborates with a wide range of artists, art professionals, and scientists to produce compelling programs for change. Through festivals, events and interventions, we invite those who live, work and play in the arts to join us.

This group aims to create a space which brings together artists and the public to work, think and talk through the implications of climate change.

Why Quiet?

Quiet activism raises questions around what it means to be an activist, or to “do activism”.

While loud, attention-grabbing and disruptive protests are important, local-scale activities are also challenging the “business as usual” model. These quiet approaches highlight how ordinary citizens can take action every day to generate transformative change.

There is a tendency within climate activism to dismiss “quiet” activities as merely a precursor to bigger, more effective (that is, “louder”) political action.

Everyday local-scale activities are sometimes seen as disempowering or conservative; they’re sometimes cast as privileging individual roles and responsibility over collective action.

However, a growing range of voices draws attention to the transformative potential of small, purposeful everyday action.

UK-based researcher Laura Pottinger emphasises that these everyday practices are acts of care and kindness to community — both human and non-human.

Her interest is a “dirt under the fingernails” kind of activism, which gains strength from a quiet commitment to practical action.

Climate Action, Here And How

The climate crisis has arrived and urgent action is required.

By creatively participating in local climate action, we can collectively reimagine our experience of, and responses to, the climate emergency.

In doing so, we lay the foundation for new possibilities.

Quiet activism is not a panacea. Like any other form of activism, it can be ineffective or, worse, damaging. Without an ethical framework, it risks enabling only short-lived action, or leading to only small pockets of localised activity.

But when done ethically and sustainably — with long-term impact in mind — quiet activism can make a profound difference to lives and communities.

Read more: From veggie gardening to op-shopping, migrants are the quiet environmentalists ![]()

Wendy Steele, Associate Professor, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University; Diana MacCallum, Adjunct research academic, Curtin University; Donna Houston, Associate Professor, School of Social Sciences, Macquarie University; Jason Byrne, Professor of Human Geography and Planning, University of Tasmania, and Jean Hillier, Professor Emerita, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cockatoos and rainbow lorikeets battle for nest space as the best old trees disappear

The housing market in most parts of Australia is notoriously competitive. You might be surprised to learn we humans are not the only ones facing such difficulties.

With spring rapidly approaching, and perhaps a little earlier due to climate change, many birds are currently on the hunt for the best nesting sites.

This can be hard enough for birds that construct nests from leaves and twigs in the canopies of shrubs and trees, but imagine how hard it must be for species that nest in tree hollows.

They are looking for hollows of just the right size, in just the right place. Competition for these prime locations is cut-throat.

Sulphur-Crested Cockatoos Battling For Spots

Sulphur-crested cockatoos, Cacatua galerita, are relatively large birds, so naturally the hollows they nest in need to be quite large.

Unfortunately, large hollows are only found in old trees.

It can take 150 years or more before the hollows in the eucalypts that many native parrot species nest in are large enough to accommodate nesting sulphur-crested cockatoos. Such old trees are becoming rarer as old trees on farms die and old trees in cities are cleared for urban growth.

In late winter, early spring you quite often find sulphur crested-cockatoos squabbling among themselves over hollows in trees.

These squabbles can be very loud and raucous. They can last from a few minutes to over an hour, if the site is good one. Once a pair of birds takes possession and begins nesting, they defend their spot and things tend to quieten down.

The stakes are high, because sulphur-crested cockatoos cannot breed if they don’t have a nesting hollow.

Read more: Don't disturb the cockatoos on your lawn, they're probably doing all your weeding for free

Enter The Rainbow Lorikeets

In parts of southeastern Australia, rainbow lorikeets, Trichoglossus moluccanus (and/or Trichoglossus haematodus), have expanded their range over the past couple of decades. It is not uncommon to see sulphur-crested cockatoos in dispute with them over a hollow.

The din can be deafening and if you watch you will see both comedy and drama unfold. The sulphur-crested cockatoos usually win and drive the lorikeets away, but all is not lost for the lorikeets.

Sometimes the hollows prove unsuitable — usually if they are too small for the cockatoos — and a few days later the lorikeets have taken up residence. Larger hollows are rarer and so more highly prized.

How Hollows Form

Many hollows begin at the stubs of branches that have been shed either as part of the tree’s growth cycle or after storm damage. The wood at the centre of the branch often lacks protective defences and so begins to decay while the healthy tree continues to grow over and around the hollow.

Other hollows develop after damage to the trunk or on a large branch, following lightning damage or insect attack. Parrots will often peck at the hollow to expand it or stop it growing over completely. Just a bit of regular home maintenance.

Sulphur-crested cockatoos can often be seen pecking at the top of large branches on old trees, where the branch meets the trunk. They can do considerable damage. When this area begins to decay, it can provide an ideal hollow for future nesting.

Sadly, for the cockatoo, it may take another century or so and the tree might shed the limb in the interim. Cockatoos apparently play a long game and take a very long term perspective on future nesting sites.

Which Trees Are Best For Hollows?

In watching the local battles for parrot nesting sites, some tree species are the scenes of many a conflict.

Sugar gums, Eucalyptus cladocalyx, were widely planted as wind breaks in southern Australia and they were often lopped to encourage a bushier habit that provided greater shade.

Poor pruning often leads to hollows and cavities, which are now proving ideal for nesting — but it also resulted in poor tree structure. Sugar gums are being removed and nesting sites lost in many country towns and peri-urban areas (usually the areas around the edges of suburbs with some remaining natural vegetation, or the areas around waterways).

Old river red gums, (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) growing along our creeks and rivers are also great nesting sites. They are so big they provide ideal sites for even the largest of birds.

These, too, are ageing and in many places are declining as riverine ecosystems suffer in general. Even the old elms, Ulmus, and London plane trees, Platanus x acerifolia — which were once lopped back to major branch stubs each year, leading hollows to develop — are disappearing as they age and old blocks are cleared for townhouses.

Read more: The river red gum is an icon of the driest continent

Protecting Tree Hollows

Cavities in trees are not that common. Large cavities are especially valuable assets. They are essential to maintaining biodiversity because it is not just birds, but mammals, reptiles, insects and arachnids that rely on them for nesting and refuge.

If you have a tree with a hollow, look after it. And while some trees with hollows might be hazardous, most are not. Every effort must be made to ensure old, hollow-forming trees are preserved. Just as importantly, we must allow hollow-forming trees to persist for long enough to from hollows.

We consider our homes to be our castles. Other species value their homes just as highly, so let’s make sure there are plenty of tree hollows in future.![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Coral, meet coral: how selective breeding may help the world’s reefs survive ocean heating

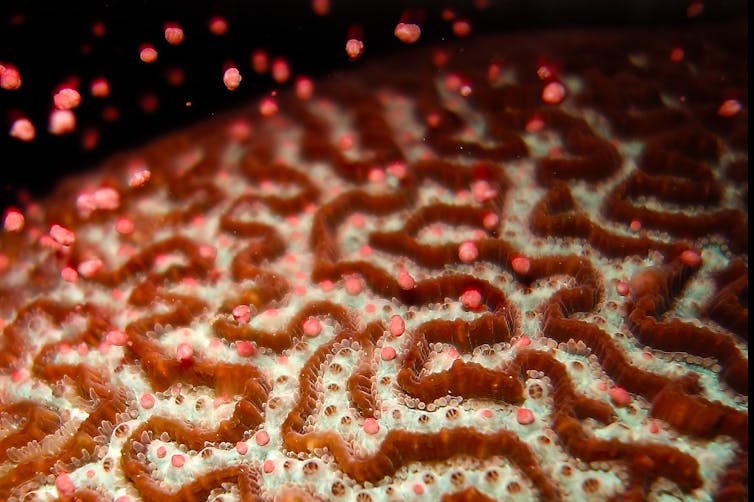

A single generation of selective breeding can make corals better able to withstand extreme temperatures, according to our new research. The discovery could offer a lifeline to reefs threatened by the warming of the world’s oceans.

Our research, published in Science Advances, shows corals from some of the world’s hottest seas can transfer beneficial genes associated with heat tolerance to their offspring, even when crossbred with corals that have never experienced such temperatures.

Across the world, corals vary widely, both in the temperatures they experience and their ability to withstand high temperatures without becoming stressed or dying. In the Persian Gulf, corals have genetically adapted to extreme water temperatures, tolerating summer conditions above 34℃ for weeks at a time, and withstanding daily averages up to 36℃.

These water temperatures are 2-4℃ higher than any other region where corals grow, and are on a par with end-of-century projections for reefs outside the Persian Gulf.

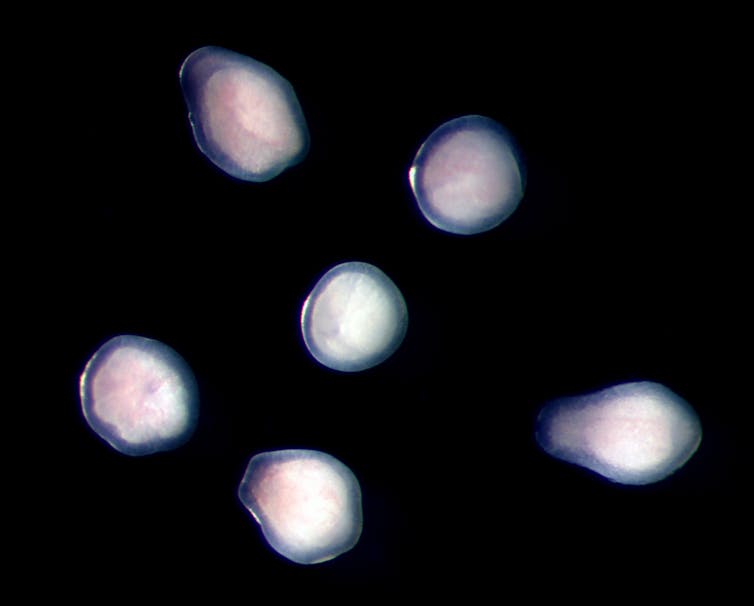

This led us to ask whether beneficial gene variants could be transferred to coral populations that are naïve to these temperature extremes. To find out, we collected fragments of Platygyra daedalea corals from the Persian Gulf, and cross-bred them with corals of the same species from the Indian Ocean, where summer temperatures are much cooler.

We then heat-stressed the resulting offspring (more than 12,000 individual coral larvae) to see whether they could withstand temperatures of 33°C and 36°C — the summer maximums of their parents’ respective locations.

Immediate Gains

We found an immediate transfer of heat tolerance when Indian Ocean mothers were crossed with Persian Gulf fathers. These corals showed an 84% increase in survival at high temperatures relative to purebred Indian Ocean corals, making them similarly resilient to purebred Persian Gulf corals.

Genome sequencing confirmed that gains in heat tolerance were due to the inheritance of beneficial gene variants from the Persian Gulf corals. Most Persian Gulf fathers produced offspring that were better able to withstand heat stress, and these fathers and their offspring had crucial variants associated with better heat tolerance.

Conversely, most Indian Ocean fathers produced offspring that were less able to survive heat stress, and were less likely to have gene variants associated with heat tolerance.

Survival Of The Fittest

Encouragingly, gene variants associated with heat tolerance were not exclusive to Persian Gulf corals. Two fathers from the Indian Ocean produced offspring with unexpectedly high survival under heat stress, and had some of the same tolerance-associated gene variants that are prevalent in Persian Gulf corals.

This suggests that some populations have genetic variation upon which natural selection can act as the world’s oceans grow hotter. Selective breeding might be able to accelerate this process.

Read more: Heat-tolerant corals can create nurseries that are resistant to bleaching

We are now assessing the genetic basis for heat tolerance in the same species of coral on the Great Barrier Reef and in Western Australia. We want to find out what gene variants are associated with heat tolerance, how these variants are distributed within and among reefs, and whether they are the same as those that allow corals in the Persian Gulf to survive such extreme temperatures.

This knowledge will help us understand the potential for Australian corals to adapt to rapid warming.

Although our study shows selective breeding can significantly improve the resilience of corals to ocean warming, we don’t yet know whether there are any trade-offs between thermal tolerance and other important traits, and whether there are significant genetic risks involved in such breeding.

Our study was done on coral larvae without the algae that live in close harmony with corals after they settle on reefs. So it will also be important to examine whether the genetic improvements to heat tolerance continue into the corals’ later life stages, when they team up with these algae.

Of course, saving corals from the perils of ocean warming will require action on multiple fronts — there is no silver bullet. Selective breeding might provide some respite to particular coral populations, but it won’t be enough to protect entire ecosystems, and nor is it a substitute for the urgent reduction of greenhouse emissions needed to limit the oceans’ warming.![]()

Emily Howells, Senior Research Fellow in Marine Biology, Southern Cross University and David Abrego, Lecturer, National Marine Science Centre, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

From jet fuel to clothes, microbes can help us recycle carbon dioxide into everyday products

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report released earlier this month sounded a “code red for humanity”. At such a crucial time, we should draw on all possible solutions to combating global warming.

About one-quarter of greenhouse gas emissions are associated with the manufacture of the products we use. While a small number of commercial uses for carbon dioxide exist — for instance in the beverage and chemical industries — the current demand isn’t enough to achieve meaningful carbon dioxide reduction.

As such, we need to find new ways to transform industrial manufacturing from being a carbon dioxide source to a carbon dioxide user.

The good news is that plastics, chemicals, cosmetics and many other products need a carbon source. If we could produce them using carbon dioxide instead of fossil hydrocarbons, we would be able to sequester billions of tonnes of greenhouse gases per year.

How, you may ask? Well, biology already has a solution.

Gas Fermentation

You may have heard of microscopic organisms, or microbes — we use them to make beer, spirits and bread. But we can also use them to create biofuels such as ethanol.

They typically need sugar as an input, which competes with human food consumption. However, there are other microbes called “acetogens” which can use carbon dioxide as their input to make several chemicals including ethanol.

Acetogens are thought to be one of the first life-forms on Earth. The ancient Earth’s atmosphere was very different to the atmosphere today — there was no oxygen, yet plentiful carbon dioxide.

Acetogens were able to recycle this carbon using chemical energy sources, such as hydrogen, in a process called gas fermentation. Today, acetogens are found in many anaerobic environments, such as in animals’ guts.

Not being able to use oxygen makes acetogens less efficient at building biomass; they are slow growers. But interestingly, it makes them more efficient producers.

For example, a typical food crop’s energy efficiency (where sunlight is turned into a product) may be around 1%. On the other hand, if solar energy was used to provide renewable hydrogen for use in gas fermentation (via acetogens), this process would have an overall energy efficiency closer to 10-15%.

This means acetogens are potentially up to twice as efficient as most current industrial processes — which makes them a cheaper and more environmentally friendly option. That is, if we can bring the technology to scale.

Sustainable Carbon Recycling

Gas fermentation is scaling up in China, the United States and Europe. Industrial emissions of carbon monoxide and hydrogen are being recycled into ethanol to commercially produce aviation fuel from 2022, plastic bottles from 2024 and even polyester clothes.

In the future this could be expanded to produce chemicals needed to make rubber, plastics, paints and cosmetics, too.

But gas fermentation currently isn’t done commercially with carbon dioxide, despite this being a much larger emission source than carbon monoxide. In part this is because it poses an engineering and bioengineering challenge, but also because it’s expensive.

We recently published an economic assessment in Water Research to help chart a pathway towards widespread acetogen-carbon dioxide recycling.

We found economic barriers in producing some products, but not all. For instance, it is viable today to use carbon dioxide-acetogen fermentation to produce chemicals required to make perspex.

But unlike current commercial operations, this would be enabled by renewable hydrogen production. Increasing the availability of green hydrogen will greatly increase what we can do with gas fermentation.

Looking Ahead

Australia has a competitive advantage and could be a leader in this technology. As host to the world’s largest green-hydrogen projects, we have the capacity to produce low-cost renewable hydrogen.

Underused renewable waste streams could also enable carbon recycling with acetogens. For instance, large amounts of biogas is produced at wastewater treatment plants and landfills. Currently it’s either burned as waste, or to generate heat and power.

Past research shows us biogas can be converted (or “reformed”) into renewable hydrogen and carbon in a carbon-neutral process.

And we found this carbon and hydrogen could then be used in gas fermentation to make carbon-neutral products. This would provide as much as 12 times more value than just burning biogas to generate heat and power.

The IPCC report shows carbon dioxide removal is required to limit global warming to less than 2℃.

Carbon capture and storage is on most governments’ agendas. But if we change our mindset from viewing carbon as a waste product, then we can change our economic incentive from carbon disposal to carbon reuse.

Carbon dioxide stored underground has no value. If we harness its full potential by using it to manufacture products, this could support myriad industries as they move to sustainable production.

Jamin Wood, PhD Candidate at the Australian Centre for Water and Environmental Biotechnology (formerly Advanced Water Management Centre), The University of Queensland; Bernardino Virdis, Senior Researcher at the Australian Centre for Water and Environmental Biotechnology (formerly Advanced Water Management Centre), The University of Queensland, and Shihu Hu, Senior Research fellow at the Australian Centre for Water and Environmental Biotechnology (formerly Advanced Water Management Centre), The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Today’s decisions lock in industry emissions for decades — here’s how to get them right

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has made clear there’s little time left to reach net zero emissions and hold the global temperature rise to 1.5C.

If Australia is to do its bit, emissions need to fall across the economy.

The states and territories all have net-zero targets for 2050, and the prime minister says the national target is also net zero emissions, preferably by 2050.

2050 feels a long way off. It’s ten election cycles for prime ministers, seven for state premiers. Does that mean there’s plenty of time to come up with mechanisms to get us there?

Unfortunately, no. Here’s why.

For Net Zero, 2050 Is Sooner Than You Think

Around 30% of Australia’s emissions come from the industrial sector — from facilities such as coal mines, liquefied natural gas platforms, steel smelters, and zinc processing plants.

These facilities have long operating lives — up to 30 to 40 years, sometimes more.

This means facilities that start up tomorrow will probably still be operating in 2050. Older facilities have only one replacement cycle between now and 2050.

Companies don’t have ten chances to get on the pathway right. They have one.

Planning to replace an ageing asset starts well before it is due to end its life, and companies can only consider realistic options.

They can’t assess costs and risks on technologies that are still in the lab.

If low-emissions technologies aren’t available or commercially feasible when decisions are made, what firms do install will lock in decades of future emissions.

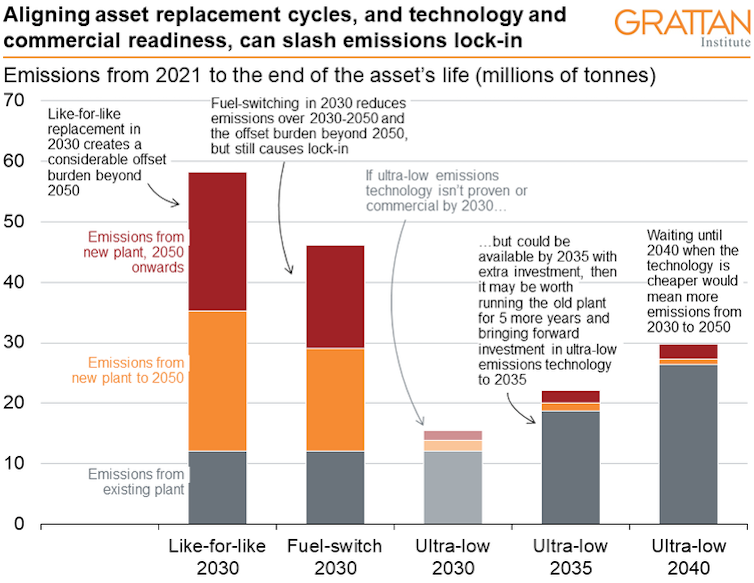

Decisions Made Today Will Extend Beyond 2050

Consider a coal-powered cement plant that will reach the end of its design life in 2030. The owner is considering three options

like-for-like replacement that still uses coal but is slightly more efficient, with costs and risks well understood

a new plant that uses gas as well as coal, whose costs and risks can be forecast with some certainty

an experimental ultra-low-emissions technology, expected to be commercially ready in 2040, with hard to quantify costs and risks, and bigger upfront cost

Taking the third option (waiting) might mean squeezing another 10 years out of an ageing plant, with a risk it might not make the distance.

This chart shows emissions between now and the end of the new plant’s life for each option.

Like-for-like replacement locks in considerable emissions between 2030 and 2050, and the risk of having to buy carbon offsets between 2050 (when Australia moves to net zero) and the end of the plant’s life in 2070.

A changed fuel mix reduces the lock-in and the likely burden of offsets, but they are still material.

Waiting until 2040 (and running the risk that the old plant might not have an extra 10 years life in it) will mean less emissions after 2040 and less liability for carbon offsets, but much more emissions before then.

Read more: Top economists call for measures to speed the switch to electric cars

From an emissions perspective, the best decision may be a halfway house — running the old plant for an extra five years, and installing the new technology before it is fully commercial, if someone else is willing to share the risk.

Without a signal from either a state or federal government the cement plant owner is likely to go with option one or two.

Government Can Help

Our report, Towards Net Zero: practical policies for the industrial sector, outlines three things the federal government can do now to tilt companies’ decisions in favour of something like option three.

First, it can signal that it expects all new facilities to avoid locking in long tails of emissions.

The best way to do this would be to fulfil its 2015 commitment to set best-practice benchmarks for new facilities. They were meant to be in place by 2020.

Second, it should set up an Industrial Transformation Future Fund in order to share the risk of new technologies with industry.

Read more: Australia's economy can withstand the proposed EU carbon tariff

Third, it should adjust its safeguard mechanism under which big emitters have to report and adhere to emissions intensity standards to require them to start cutting emissions immediately.

This would level the field between new and old facilities. It would mean some older facilities closed earlier than planned, but it would mean they would be replaced by cleaner facilities.

It is important these policies start now. Every decision we make from now on will affect our chance of reaching net zero and escaping catastrophic climate change.![]()

Alison Reeve, Deputy Program Director, Energy and Climate Change, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pacific Island bats are utterly fascinating, yet under threat and overlooked. Meet 4 species

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s new series introducing you to unloved animals that need our help.

A whopping 191 different bat species live in the Pacific Islands across Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia — but these are, collectively, the most imperilled in the world. In fact, five of the nine bat species that have gone extinct in the last 160 years have come from this region.

For too long, the conservation of Pacific Island bats has been largely overlooked in science. Of the 191 existing species, 25% are threatened with extinction, and we lack information to assess the status of a further 15%.

Just as these bats are rare and far-flung across the Pacific islands, so is the expertise and research needed to conserve them along with the vital ecosystem services they provide, such as pollination, seed dispersal, and insect control.

The first-ever Pacific Islands Bat Forum, held earlier this month, sought to change this, bringing together a new network of researchers, conservationists, and community members — 380 people from 40 countries and territories — dedicated to their survival.

So, Why Should We Care About These Bats Anyway?

Conserving Pacific Island bats is paramount for preserving the region’s diverse human cultures and for safeguarding the healthy functioning of island ecosystems.

In many Pacific Island nations, bats have great cultural significance as totems, food, and traditional currency.

Bats are the largest land animals on many of the Pacific islands, and are vital “keystone species”, maintaining the structure of ecological communities.

Yet, Pacific Island bats are increasingly under threat, including from intensifying land use (farming, housing, roads) invasive species (rats, cats, snakes, ants), and human harvesting. They’re also vulnerable to climate change, which heightens sea levels and increases the intensity of cyclones and heatwaves.

So let’s meet four fascinating — but threatened — Pacific Island bats that deserve more attention.

1. Pacific Sheath-Tailed Bat

Conservation status: endangered

Distribution: American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Samoa, Tonga

The Pacific sheath-tailed bat (Emballonura semicaudata) weighs just five-grams and has a weak, fluttering flight. Yet somehow, it has colonised some of the smaller and more isolated islands across the Pacific, from Samoa to Palau. That’s across 6,000 kilometres of ocean!

Over the past decade, this insect-eating, cave-roosting bat has disappeared from around 50% of islands where it has been recorded. The reasons for this are unclear. Disturbance of cave roosts, introduced species such as lantana and goats, and increasing use of pesticides, may all have played a part.

Unfortunately, the Pacific sheath-tailed bat is now presumed extinct in many former parts of its range, including American Samoa, Tonga, and several islands of the Northern Mariana Islands. This leaves Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Fiji as remaining strongholds for the species, though data is limited.

2. Montane Monkey-Faced Bat

Conservation status: critically endangered

Distribution: Solomon Islands

There are six species of monkey-faced bat — all are threatened, and all are limited to islands across the Solomon Islands, Bougainville, and Fiji.

The montane monkey-faced bat (Pteralopex pulchra) is one species, and weighs around 280 grams, eats fruit and nectar, and has incredibly robust teeth. But perhaps most startling is its ruby-red eyes and wing membranes that are marbled with white and black.

The montane monkey-faced bat has been recorded only once by scientists on a single mountain (Mt Makarakomburu) above the altitude of 1,250 metres, on Guadalcanal Island. This tiny range makes it vulnerable to rare, extreme events such as cyclones, which could wipe out a whole population in one swoop. And being limited to mountain-top cloud forests could place it at greater risk from climate change.

It’s an extreme example of both the endemism (species living in a small, defined area) and inadequacies of scientific knowledge that challenge Pacific island bat conservation.

3. Ornate Flying-Fox

Conservation status: vulnerable

Distribution: New Caledonia

Like many fruit bats across the Pacific, New Caledonia’s endemic ornate flying-fox (Pteropus ornatus) is an emblematic species. Flying-foxes are hunted for bush meat, used as part of cultural practices by the Kanaks (Melanesian first settlers), are totems for some clans, and feature as a side dish during the “New Yam celebration” each year. Their bones and hair are also used to make traditional money.

Because they’re so highly prized, flying-foxes can be subject to illegal trafficking. Despite the Northern and Southern Provinces of New Caledonia having regulated hunting, flying-fox populations continue to decline. Recent studies predict 80% of the population will be gone in the next 30 years if hunting continues at current levels.

On a positive note, earlier this year the Northern Province launched a conservation management program to protect flying-fox populations while incorporating cultural values and practices.

4. Fijian Free-Tailed Bat

Conservation status: endangered

Distribution: Fiji, Vanuatu

In many ways, the Fijian free-tailed bat (Chaerephon bregullae) has become the face of proactive bat conservation in the Pacific Islands. This insect-eating bat requires caves to roost during the day and is threatened when these caves are disturbed by humans as it interrupts their daytime roosting. The loss of foraging habitat is another major threat.

The only known colony of reproducing females lives in Nakanacagi Cave in Fiji, with around 7,000 bats. In 2014, an international consortium with Fijian conservationists and community members came together to protect Nakanacagi Cave. As a result, it became recognised as a protected area in 2018.

But this species shares many characteristics with three of the nine bat species that have gone extinct globally. This includes being a habitat specialist, its unknown cause of decline, and its potential exposure to chemicals through insect foraging. It’s important we continue to pay close attention to its well-being.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The perspectives of local knowledge from individual islands aren’t always captured in global scientific assessments of wildlife.

In many Pacific Islands, bats aren’t protected by national laws. Instead, in many countries, most land is under customary ownership, which means it’s owned by Indigenous peoples. This includes land in Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. Consequently, community landowners have the power to enact their own conservation actions.

The emerging Pacific Bat Network, inspired by the recent forum, aims to foster collaborative relationships between scientific conservationists and local leaders for species protection, while respecting cultural practices.

As the Baru Conservation Alliance — a locally-led, not-for-profit group from Malaita, Solomon Islands — put it in their talk at the forum:

conservation is not a new thing for Kwaio.

Now the forum has ended, the diverse network of people passionate about bat conservation is primed to work together to strengthen the conservation of these unique and treasured bats of the Pacific.![]()

John Martin, Research Scientist, Taronga Conservation Society Australia & Adjunct lecturer, University of Sydney; David L. Waldien, Adjunct assistant professor, Christopher Newport University; Junior Novera, PhD Candidate, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland; Justin A. Welbergen, President of the Australasian Bat Society | Associate Professor of Animal Ecology, Western Sydney University; Malik OEDIN, PhD Population Biology and Ecology, Université de Nouvelle Calédonie; Nicola Hanrahan, Terrestrial Ecologist, Department of Environment, Parks and Water Security, Northern Territory Government & Visiting Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Tigga Kingston, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech University, and Tyrone Lavery, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

Spring In Pittwater

The first Flying Duck Orchid of Spring 2021 - photo by Selena Griffith

Caleana major was first formally described in 1810 by Robert Brown from a specimen he collected at Port Jackson, Bennelong Point in September 1803. The description was published in Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van Diemen. The genus name (Caleana) honours George Caley, an early botanical collector and the specific epithet (major) is a Latin word meaning "large" or "great". Mr. Caley is also honoured in the also local critically endangered Grevillea Caleyi of Ingleside.

The flying duck orchid occurs in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania, growing in eucalyptus woodland, coastal or swampy shrubland and heathland. Mostly near the coast, but occasionally at higher altitudes.

HSC In November And All Students To Return To School In Term 4

August 27, 2021

There will be a staggered return to face-to-face learning from October, HSC exams will be delayed until November and vaccinations for school staff will be mandatory based on the return to school plan released by the NSW Government today.

The Department of Education has developed a plan to bring students back in a COVID-safe way while stay at home orders are still in place – ensuring continuity of education, and protecting student, teacher and community safety.

A staggered return of students to face-to-face learning will begin on Monday 25 October.

Students will return to face-to-face learning with NSW Health approved COVID safe settings on school sites in the following order:

- From 25 October – Kindergarten and Year 1

- From 1 November – Year 2, 6 and 11

- From 8 November – Year 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 and 10

Year 12 students are already able to return in a limited way and this will continue for the remainder of Term 3. From 25 October, Year 12 will have full time access to school campuses and their teachers.

If stay at home orders are lifted in an LGA or region before 25 October, all students living or learning in that area will return to face to face learning under the Department’s COVID-safe schools framework.

If cases in certain LGAs increase significantly, learning from home will resume for that LGA until case numbers drop.

HSC exams will be delayed until November 9th with a revised timetable and guidelines for a COVID-safe HSC to be released by NESA in early September. Importantly, the delay of the HSC exams will not disadvantage NSW students when applying to university.

Vaccinations for all school staff across all sectors will be mandatory from November 8th. NSW Health will be providing priority vaccinations at Qudos Bank Arena for school staff the week beginning September 6th.

Early childcare staff will also be able to participate in the priority vaccinations from 6 September. All school and early childcare staff are also encouraged to make use of the GP network to be vaccinated with whatever vaccine is available as soon as possible.

A recent survey of the public school workforce indicated the majority of staff already had at least one dose of a vaccine.

All students eligible for a vaccine will be strongly encouraged by the government to book an appointment.

Students aged 12-15 will also be a priority if they become eligible for a vaccine.

All parents who have not been vaccinated are strongly encouraged to get the vaccine as soon as possible.

Premier Gladys Berejiklian said the NSW Government is prioritising the safety and education of students through a sensible and managed return to school.

“The return to school plan provides parents, teachers and students with certainty and a path forward for the return to face-to-face learning,” Ms Berejiklian said.

“We know the last few months have been tough on the school community and we are deeply grateful to parents, teachers and students for the sacrifices you have made. Please continue to protect our students by getting vaccinated as quickly as possible.”

Minister for Education and Early Childhood Learning Sarah Mitchell said the education and safety of our students is essential.

“The classroom is where students learn best and I thank the entire community for playing their role in this return by getting vaccinated,” Ms Mitchell said.

After Dark Photo Competition: Northern Beaches

The Northern Beaches are one of the best places in Sydney to view the night sky and appreciate this wonderful asset.

The Northern Beaches are one of the best places in Sydney to view the night sky and appreciate this wonderful asset.Details

- Land – manmade and/or natural formations, wildlife, flora or fauna

- Sea – waterways, beaches, or marine areas, sea life

- Sky – aspects of the night sky, moon, starscapes, clouds or wildlife

- Junior – under 16 years featuring any one of these categories.

- Entry fees are $10 for the first category entered and $10 for each subsequent category entered.

- Up to six entries per category are permitted.

- Fees should be paid by the PayPal gateway on the entry website. Credit and debit cards can be used on this gateway.

- If entry payments are not received by the deadline, then the submitted entries will not be accepted for judging.

- Entries will be accepted only from Australian residents of the Commonwealth of Australia and its Territories.

- There will be two sections of entry – General and Junior (18 or younger)

- There will be three categories of entry for the General Section; Portraying the night time environment featuring Land, Sea or Sky.

- The Junior Section is for photographers 18 years old or younger and will have one open category.

- All entries must be taken within the Northern Beaches LGA and must be taken between sunset and sunrise.

- Images can be taken at any time of the year on or after 1 September 2019.

- The top 5 images of each category will be judged by the organising committee and will be hung at the Studio, Careel Bay Marina for general public display.

- Photographers represented in the top 5 images of each category will be notified that they are in the top 20 images (15 September 17:00 AEST).

- There is a limit of six (6) entries per category per photographer.

- In the case of images with multiple authors, the instigator of the image will be considered to be the principal author and the one who “owns” the image. The principal author MUST have performed the majority of the work to produce the image. All authors MUST be identified and named in the entry form along with their contributions to the production of the image.

- Entries must be in digital form and will be accepted ONLY through submission via the dedicated website at: afterdark.myphotoclub.com.au

- To preserve anonymity, the submitted image files should not contain identifying metadata.

- For judging purposes, still images must be submitted as JPG files with the longest side having a dimension no greater than 4,950 pixels in Adobe 1998 colour space.

- All photographs must have been taken no more than 2 years before the closing date of entry.

- Entry fees are $20 for the first entry and $10 each subsequent entry. Fees should be paid by the PayPal gateway on the entry website. Credit and debit cards can be used on this gateway.

- If entry payments are not received by the deadline, then the submitted entries will not be accepted for judging.

- Photographers of the top 20 images (5 in each category) will be notified 15 September and images printed, framed and hung by the organising. Artists may choose to pay $55 for this service to be undertaken on their part or undertake printing and framing at their own cost. Images must be ready for hanging 17:00 (AEST) 29 September 2021.

- Images will be listed on sale during the exhibition at the artist’s discretion. $100 of the sale will be donated to the charity the Australasian Dark Sky Alliance.

- Winners for the Land Scape, Sea Scape, Sky Scape and Youth entry will be announced Thursday 30th September 2021.

- People’s choice will confirmed by popular vote throughout the exhibition and will be announced on Saturday 30 October, 2021.

- Submissions close at 24:00 (AEST) on Wednesday, 1 September 2021. No entries will be accepted past this date.

- All winners should make an effort to attend the presentation of the awards on 30 September 2021