Inbox and Environment News: Issue 511

September 19 - October 2, 2021: Issue 511

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Pittwater Nature Issue 7

Aussie Backyard Bird Count 2021

Save the date – there’s only 1 MONTH TO GO until the 2021 Aussie Bird Count and we can’t wait!

The 2021 event will run from October 18‒24 during National Bird Week. Register as a counter today at: https://aussiebirdcount.org.au/

The Aussie Backyard Bird Count is one of Australia’s biggest citizen science events. This year is our eighth count, and we’re hoping it will be our biggest yet!

Join thousands of people around the country in exploring your backyard, local park or favourite outdoor space and help us learn more about the birds that live where people live.

Taking part in the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is a great way to connect with the birds in your backyard, no matter where your backyard happens to be. You can count in a suburban garden, a local park, a patch of forest, down by the beach, or the main street of town.

To take part, register on the website today, then during the count you can use the web form or the app to submit your counts. Just enter your location and get counting ‒ each count takes just 20 minutes!

Not only will you be contributing to BirdLife Australia's knowledge of Aussie birds, but there are also some incredible prizes on offer.

Head over to the Aussie Backyard Bird Count website to find out more.

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

September Is Koala Month & Biodiversity Month

Cockatoo Preening

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Managing Climate Risks To Assets And Services: New South Wales Auditor-General's Report - Performance Audit

- enhance the coordination of climate risk management across agencies

- implement climate risk management across their clusters.

- update information and strengthen education to agencies, and monitor progress

- review relevant land-use planning, development and building guidance

- deliver a climate change adaptation action plan for the state.

- strengthen climate risk-related guidance to agencies

- coordinate guidance on resilience in infrastructure planning

- review how climate risks have been assured in agencies’ asset management plans.

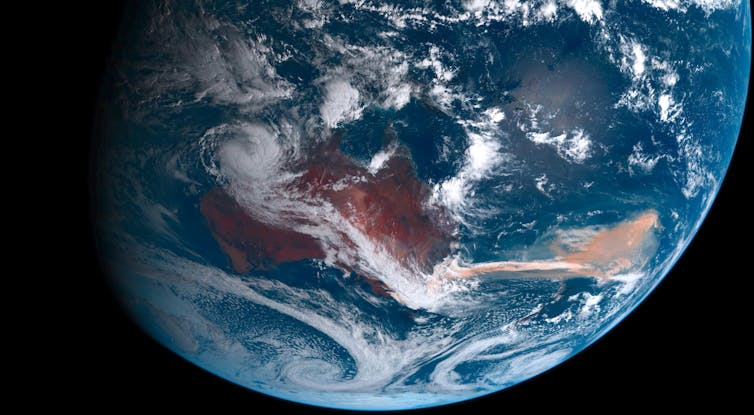

Smoke from the Black Summer fires created an algal bloom bigger than Australia in the Southern Ocean

In 2019 and 2020, bushfires razed more than 18 million hectares of land in Australia. For weeks, smoke choked major cities, leading to almost 450 deaths, and even circumnavigated the southern hemisphere.

As the aerosols billowed across the oceans many thousands of kilometres away from the fires, microscopic marine algae called phytoplankton had an unexpected windfall: they received a boost of iron.

Our research, published today in Nature, found this caused phytoplankton concentrations to double between New Zealand and South America, until the bloom area became bigger than Australia. And it lasted for four months.

This enormous, unprecedented algal bloom could have profound implications for carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and for the marine ecosystem. But so far, the impact is still unclear.

Meanwhile, in another paper published alongside ours in Nature today, researchers from The Netherlands found the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by the fires that summer was more than double previous estimates.

Absorbing 680 Million Tonnes Of Carbon Dioxide

Iron fertilises phytoplankton and helps them grow, in the same way nutrients added in soil help vegetables grow. And like plants on land, phytoplankton photosynthesise — they absorb CO₂ as they grow and produce oxygen for fish and other marine creatures.

We used satellite data to estimate that for phytoplankton to grow as much as they did in the Southern Ocean, they would have absorbed 680 million tonnes of CO₂. This means the phytoplankton absorbed roughly the same amount of CO₂ as released by the bushfires, according to the latest estimates released today.

The Dutch researchers found the bushfires released 715 million tonnes of CO₂ (or ranging 517–867 million tonnes) between November 2019 and January 2020. This surpasses Australia’s normal annual fire and fossil fuel emissions by 80%.

To put this into perspective, Australia’s anthropogenic CO₂ emissions in 2019 were much less, at 520 million tonnes.

Phytoplankton Can Have Dramatic Effects On Climate

But that doesn’t mean the phytoplankton growth absorbed the bushfire’s CO₂ emissions permanently. Whether phytoplankton growth extracts and keeps CO₂ from the atmosphere depends on their fate.

If they sink to the deep ocean, then this represents a carbon sink for decades or even centuries — or even longer if phytoplankton are stored in ocean sediments.

But if they’re mostly eaten and decomposed near the ocean’s surface, then all that CO₂ they consumed comes straight back out, with no net effect on the carbon balance in the atmosphere.

In fact, phytoplankton have very likely played a role on millennial time scales in keeping atmospheric CO₂ concentrations down, and can affect the global climate in the long term.

For example, a 2014 study suggests iron-containing dust billowing over the Southern Ocean caused increased phytoplankton productivity, which contributed to reducing atmospheric CO₂ by about 100 parts per million. And this helped transition the planet to ice ages.

Read more: Inside the world of tiny phytoplankton – microscopic algae that provide most of our oxygen

Phytoplankton blooms can also have a big impact on the marine ecosystem as they make excellent food for some marine creatures.

For example, more phytoplankton means more food for zooplankton that feed on phytoplankton, with effects up the food chain. It’s also worth noting this huge bloom occurred at a time of year when phytoplankton are usually in decline in this part of the ocean.

But whether there were any long-lasting effects from the bushfire-fuelled phytoplankton on the climate or ecosystem is unclear, because we still don’t know where they ended up.

Using Revolutionary Data

The link between fire aerosols and the increase in phytoplankton demonstrated in our study is particularly relevant given the intense fire activity around the globe.

Droughts and warming under global climate change are expected to increase the frequency and intensity of wildfires, and the impacts to land-based ecosystems, such as habitat loss and air pollution, will be dramatic. But as we now know, wildfires can also affect marine life thousands of kilometres away from land.

Previous models have predicted the iron-fertilising effect of bushfire aerosols, but this is the first time we’ve observed and demonstrated the connection at a large-scale.

Our study is mainly based on satellite data and observations from robotic floats that roam the oceans and collect data autonomously. These robotic floats are revolutionising our understanding of chemical cycling, oxygen variability and ocean acidification.

During the bushfire period, our smoke tracers reached concentrations at least 300% higher than what had ever been observed in the 22-year satellite record for the region.

Interestingly, you wouldn’t be able to observe the resulting phytoplankton growth in a true-colour satellite image. We instead used more sensitive ocean colour sensors on satellites to estimate phytoplankton concentrations.

Read more: Tiny plankton drive processes in the ocean that capture twice as much carbon as scientists thought

So What’s Next?

Of course, we need more research to determine the fate of the phytoplankton. But we also need more research to better predict when and where aerosol deposition (such as bushfire smoke) will boost phytoplankton growth.

For example, the Tasman Sea — between Australia and New Zealand — showed only mildly higher phytoplankton concentrations during the bushfire period, even though the smoke cloud was strongest there.

Was this because nutrients other than iron were lacking, or because there was less deposition? Or perhaps because the smoke didn’t stick around for as long?

Whatever the reason, it’s clear this is only the beginning of exciting new lines of research that link forests, wildfires, phytoplankton growth and Earth’s climate.

Christina Schallenberg, Research Fellow, University of Tasmania; Jakob Weis, Ph.D. student, University of Tasmania; Joan Llort, Oceanógrafo , Barcelona Supercomputing Center-Centro Nacional de Supercomputación (BSC-CNS); Peter Strutton, Professor, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, and Weiyi Tang, Postdoc in Biogeochemistry, Princeton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rural Boundary Clearing Code Opens Up More Bushland For Destruction

Destroying vegetation along fences and roads could worsen our extinction crisis — yet the NSW government just allowed it

What do koalas, barking owls, greater gliders, southern rainbow skinks, native bees, and regent honeyeaters all have in common? Like many native species, they can all be found in vegetation along fences and roadsides outside formal conservation areas.

They may be relatively small, but these patches and strips conserve critical remnant habitat and have disproportionate conservation value worldwide. They represent the last vestiges of once-expansive tracts of woodland and forests, long lost to the chainsaw or plough.

And yet, the NSW government last week made it legal for rural landholders to clear vegetation within 25 metres of their property boundaries, without approval. This radical measure is proposed to protect people and properties from fires, despite the lack of such an explicit recommendation from federal and state-based inquiries into the devastating 2019-20 bushfires.

This is poor environmental policy that lacks apparent consideration or justification of its potentially substantial ecological costs. It also gravely undermines the NSW government’s recent announcement of a plan for “zero extinction” within the state’s national parks, as the success of protected reserves for conservation is greatly enhanced by connection with surrounding “off-reserve” habitat.

Small Breaks In Habitat Can Have Big Impacts

A 25m firebreak might sound innocuous, but when multiplied by the length of property boundaries in NSW, the scale of potential clearing and impacts is alarming, and could run into the hundreds of thousands of kilometres.

Some plants, animals and fungi live in these strips of vegetation permanently. Others use them to travel between larger habitat patches. And for migratory species, the vegetation provides crucial refuelling stops on long distance journeys.

For example, the roadside area in Victoria’s Strathbogie Ranges shown below is home to nine species of tree-dwelling native mammals: two species of brushtail possums, three species of gliders (including threatened greater gliders), common ringtail possums, koalas, brush-tailed phascogales, and agile antenchinus (small marsupials).

Many of these species depend on tree hollows that can take a hundred years to form. If destroyed, they are effectively irreplaceable.

Creating breaks in largely continuous vegetation, or further fragmenting already disjointed vegetation, will not only directly destroy habitat, but can severely lower the quality of adjoining habitat.

This is because firebreaks of 25m (or 50m where neighbouring landholders both clear) could prevent the movement and dispersal of many plant and animal species, including critical pollinators such as native bees.

An entire suite of woodland birds, including the critically endangered regent honeyeater, are threatened because they depend on thin strips of vegetation communities that often occur inside fence-lines on private land.

For instance, scientific monitoring has shown five pairs of regent honeyeaters (50% of all birds located so far this season) are nesting or foraging within 25m of a single fence-line in the upper Hunter Valley. This highlights just how big an impact the loss of one small, private location could have on a species already on the brink of extinction.

Read more: Only the lonely: an endangered bird is forgetting its song as the species dies out

But it’s not just regent honeyeaters. The management plan for the vulnerable glossy black cockatoo makes specific recommendation that vegetation corridors be maintained, as they’re essential for the cockatoos to travel between suitable large patches.

Native bee conservation also relies on the protection of remnant habitat adjoining fields. Continued removal of habitat on private land will hinder chances of conserving these species.

Disastrous Clearing Laws

The new clearing code does have some regulations in place, albeit meagre. For example, on the Rural Fire Service website, it says the code allows “clearing only in identified areas, such as areas which are zoned as Rural, and which are considered bush fire prone”. And according to the RFS boundary clearing tool landowners aren’t allowed to clear vegetation near watercourses (riparian vegetation).

Even before introducing this new code, NSW’s clearing laws were an environmental disaster. In 2019, The NSW Audit Office found:

clearing of native vegetation on rural land is not effectively regulated [and] action is rarely taken against landholders who unlawfully clear native vegetation.

The data back this up. In 2019, over 54,500 hectares were cleared in NSW. Of this, 74% was “unexplained”, which means the clearing was either lawful (but didn’t require state government approval), unlawful or not fully compliant with approvals.

Landholders need to show they’ve complied with clearing laws only after they’ve already cleared the land. But this is too late for wildlife, including plant species, many of which are threatened.

Read more: The 50 beautiful Australian plants at greatest risk of extinction — and how to save them

Landholders follow self-assessable codes, but problems with these policies have been identified time and time again — they cumulatively allow a huge amount of clearing, and compliance and enforcement are ineffective.

We also know, thanks to various case studies, the policy of “offsetting” environmental damage by improving biodiversity elsewhere doesn’t work.

So, could the federal environment and biodiversity protection law step in if habitat clearing gets out of hand? Probably not. The problem is these 25m strips are unlikely to be referred in the first place, or be considered a “significant impact” to trigger the federal law.

The Code Should Be Amended

Nobody disputes the need to keep people and their assets safe against the risks of fire. The code should be amended to ensure clearing is only permitted where a genuinely clear and measurable fire risk reduction is demonstrated.

Granting permission to clear considerable amounts of native vegetation, hundreds if not thousands of metres away from homes and key infrastructure in large properties is hard to reconcile, and it seems that no attempt has been made to properly justify this legislation.

We should expect that a comprehensive assessment of the likely impacts of a significant change like this would inform public debate prior to decisions being made. But to our knowledge, no one has analysed, or at least revealed, how much land this rule change will affect, nor exactly what vegetation types and wildlife will likely be most affected.

A potentially devastating environmental precedent is being set, if other regions of Australia were to follow suit. The environment and Australians deserve better.

Read more: 'Existential threat to our survival': see the 19 Australian ecosystems already collapsing ![]()

Euan Ritchie, Professor in Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Centre for Integrative Ecology, School of Life & Environmental Sciences, Deakin University; Ben Moore, Senior Lecturer in Ecology, Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University; Jen Martin, Leader, Science Communication Teaching Program, The University of Melbourne; Mark Hall, Postdoctoral research fellow, Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University; Megan C Evans, Lecturer and ARC DECRA Fellow, UNSW, and Ross Crates, Postdoctoral fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Zero Extinctions Target Set For NSW National Parks

- The AIS initiative is a key pillar of the National Parks Threatened Species Framework, which will align NPWS with the global biodiversity agenda and position the agency as a world leader in threatened species conservation.

- AIS declarations for land containing important threatened species habitat, supported by Conservation Action Plans will ensure NPWS:

- has identified the most important on-park habitat for threatened species, has up-to-date data on populations in these areas, and can share this information with others, including firefighting agencies and conservation partners

- has action plans in place to reduce threats and improve the conservation status of threatened species in priority locations

- is regularly monitoring the health of these populations and publicly reporting outcomes.

- Other measures being implemented to protect threatened species on national parks include:

- Acquisition of key threatened species habitat for addition to the national park estate

- The establishment of a network of feral predator-free areas to support the return of more than 25 locally extinct species

- Delivery of the largest feral animal control program in national park history

- Establishment of a dedicated ecological risk unit to ensure threatened species are considered in new fire plans

- Rolling out a world class ecological health framework across national parks

- In total 66 plant species (Including the previously declared Wollemi Pine) and 27 animal species including 13 mammals, four birds, seven frogs and three reptiles

- 221 AIS sites across 110 national parks totalling 301,843 hectares (3.89% of the National Parks estate

- 92 new species of plants and animals to attain AIS status, including:

- Brush-tailed Rock-wallaby: 7 sites including a highly endangered population in the Warrumbungles, where the population is now < 10 individuals

- Koala: 15 of the most important koala strongholds on national parks such as Lake Innes, Port Macquarie and Upper Nepean SCA, south west of Sydney.

- Dwarf Mountain Pine: Less than 800 plants remain in the spray zones along cliff faces between Wentworth Falls and Katoomba in the upper Blue Mountains.

- Nightcap Oak: a small population of around 125 adult plants found only on the Nightcap Range, north of Lismore

Ocean Conservationists Welcome Australia’s Support For Global Plastics Treaty

What Is The 'Global Plastics Treaty'?

- There is no clear global ambition or target

- No common obligation for nations to develop action plans

- No agreed standards for monitoring and reporting of plastics discharge into the sea

- No standardised review of the effectiveness of different pollution reduction measures

- No specialised scientific body with a mandate to assess the global problem and give guidance to decision makers

- Global targets with deadlines for reducing plastic and cleaning up our oceans, with all nations working together to eliminate unnecessary or dangerous plastics and ensure all plastic is reused, recycled or composted in practice. This could include things like an international ban on dumping plastic in rivers and waterways, and global bans on plastics like bags and straws that are a high risk for ocean wildlife.

- Monitoring and reporting on plastics in the natural environment, with nations required to report on their efforts to cut plastic. Advocates are also calling for a specialised international scientific body with a mandate to investigate and track the scale and sources of plastic pollution, providing world class scientific knowledge for effective policy making.

- Financial and technical support, with a dedicated global body providing financial support and technical expertise for countries with limited capacity. This would be critical for helping badly affected nations at the edges of the worst plastic hotspots like the Great Pacific Garbage patch, many of whom lack the infrastructure and resources to deal with the waves of plastic washing up on their shores.

- Pew Charitable Trusts and Systemiq. (2020). Breaking the Plastic Wave.

Catch Alert Drumlines Set To Be Trialled On Queensland Beaches Will Reduce Marine Wildlife Deaths Conservationists Say

Western Sydney Breathes A Little Easier Thanks To Waste Incinerator Decisions

Bylong Valley Spared From Coal Mining Again

- Bylong Community Wins Again as Coal Mine Appeal is Dismissed, EDO, 14-9-21

- Huge legal win sees greenfield Bylong Coal Project refusal upheld, EDO, 18-12-2020

NSW Government Urged To Give Bylong Back To Farmers Following KEPCO’s Latest Legal Loss

NT 'Environment' Minister Lawler Signals Approval Of Fracking Plan

Consultation Opens For Mining Exploration Program

Public Consultation Opens For Greenhouse Gas Storage Areas

- Bonaparte Basin

- Browse Basin

- Northern Carnarvon Basin.

Minister Pitt States Coal To Continue Help Powering Australian Economy

Pitt States Will Continue Funding For Fracking Despite Court Challenge To Fracked Gas Cash Splash

Beetaloo Cooperative Drilling Program Will Continue

Tasmania’s salmon industry detonates underwater bombs to scare away seals – but at what cost?

Australians consume a lot of salmon – much of it farmed in Tasmania. But as Richard Flanagan’s new book Toxic shows, concern about the industry’s environmental damage is growing.

With the industry set to double in size by 2030, one dubious industry practice should be intensely scrutinised – the use of so-called “cracker bombs” or seal bombs.

The A$1 billion industry uses the technique to deter seals and protect fish farming operations. Cracker bombs are underwater explosive devices that emit sharp, extremely loud noise impulses. Combined, Tasmania’s three major salmon farm operators have detonated at least 77,000 crackers since 2018.

The industry says the deterrent is necessary, but international research shows the devices pose a significant threat to some marine life. Unless the salmon industry is more strictly controlled, native species will likely be killed or injured as the industry expands.

Protecting A Lucrative Industry

Marine farming has been growing rapidly in Tasmania since the 1990s, and Atlantic salmon is Tasmania’s most lucrative fishery‑related industry. The salmon industry comprises three major producers: Huon Aquaculture, Tassal and Petuna.

These companies go to great effort to protect their operations from fur seals, which are protected in Australia with an exemption for the salmon industry.

Seals may attack fish pens in search of food and injure salmon farm divers, though known incidents of harm to divers are extremely rare.

The industry uses a number of seal deterrent devices, the use of which is approved by the government. They include:

lead-filled projectiles known as “beanbags”, which are fired from a gun

sedation darts fired from a gun

explosive charges or “crackers” thrown into the water which detonate under the surface.

In June this year, the ABC reported on government documents showing the three major salmon producers had detonated more than 77,000 crackers since 2018. The documents showed how various seal deterrent methods had led to maiming, death and seal injuries resulting in euthanasia. Blunt-force trauma was a factor in half the reported seal deaths.

A response to this article by the salmon industry can be found below. The industry has previoulsy defended the use of cracker bombs, saying it has a responsibility to protect workers. It says the increased use of seal-proof infrastructure means the use of seal deterrents is declining. If this is true, it’s not yet strongly reflected in the data.

Read more: Here's the seafood Australians eat (and what we should be eating)

Piercing The Ocean Silence

Given the prevalence of seal bomb use by the salmon industry, it’s worth reviewing the evidence on how they affect seals and other marine life.

A study on the use of the devices in California showed they can cause horrific injuries to seals. The damage includes trauma to bones, soft tissue burns and prolapsed eye balls, as well as death.

And research suggests damage to marine life extends far beyond seals. For example, the devices can disturb porpoises which rely on echolocation to find food, avoid predators and navigate the ocean. Porpoises emit clicks and squeaks – sound which travels through the water and bounces off objects. In 2018, a study found seal bombs could disturb harbour porpoises in California at least 64 kilometres from the detonation site.

There is also a body of research showing how similar types of industrial noise affect marine life. A study in South Africa in 2017 showed how during seismic surveys in search of oil or gas, which produce intense ocean noise, penguins raising chicks often avoided their preferred foraging areas. Whales and fish have also shown similar avoidance behaviour.

The study showed underwater blasts can also kill and injure seabirds such as penguins. And there may be implications from leaving penguin nests unattended and vulnerable to predators, and leaving chicks hungry longer.

Research also shows underwater explosions damage to fish. One study on caged fish reported profound trauma to their ears, including blistering, holes and other damage. Another study cited official reports of dead fish in the vicinity of seal bomb explosions.

Shining A Light

Clearly, more scientific research is needed into how seal bombs affect marine life in the oceans off Tasmania. And regulators should impose far stricter limits on the salmon industry’s use of seal bombs – a call echoed by Tasmania’s Salmon Reform Alliance.

All this is unfolding as federal environment laws fail to protect Australian plant and animal species, including marine wildlife.

And the laws in Tasmania are far from perfect. In 2017, Tasmania’s Finfish Farming Environmental Regulation Act introduced opportunities for better oversight of commercial fisheries. However, as the Environmental Defenders Office (EDO) has noted, the director of Tasmania’s Environment Protection Authority can decide on license applications by salmon farms without the development necessarily undergoing a full environmental assessment.

Tasmania’s Marine Farming Planning Act covers salmon farm locations and leases. As the EDO has noted, the public is not notified of some key decisions under the law and has very limited public rights of appeal.

Two relevant public inquiries are underway – a federal inquiry into aquaculture expansion and a Tasmanian parliamentary probe into fin-fish sustainability. Both have heard evidence from community stakeholders, such as the Tasmanian Alliance for Marine Protection and the Tasmanian Conservation Trust, that the Tasmanian salmon industry lacks transparency and provides insufficient opportunities for public input into environmental governance.

The Tasmanian government has thrown its support behind rapid expansion of the salmon industry. But it’s essential that the industry is more tightly regulated, and far more accountable for any environmental damage it creates.

Read more: Why Indigenous knowledge should be an essential part of how we govern the world's oceans

In a statement in response to this article, the Tasmanian Salmonid Growers Association, which represents the three producers named above, said:

Around $500 million has been spent on innovative pens by the industry. These pens are designed to minimise risks to wildlife as well as to fish stocks and the employees. We believe that farms should be designed to minimise the threat of seals, but we also understand that non-lethal deterrents are a part of the measures approved by the government for the individual member companies to use. If these deterrents are used it is under strict guidelines, sparingly, and in emergency situations when staff are threatened by these animals, which can be very aggressive.

Tasmania has a strong, highly regulated, longstanding salmon industry of which we should all be proud. The salmon industry will continue its track record of operating at world’s best practice now and into future. Our local people have been working in regional communities for more than 30 years, to bring healthy, nutritious salmon to Australian dinner plates, through innovation and determination.

Benjamin J. Richardson, Professor of Environmental Law, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How much will our oceans warm and cause sea levels to rise this century? We’ve just improved our estimate

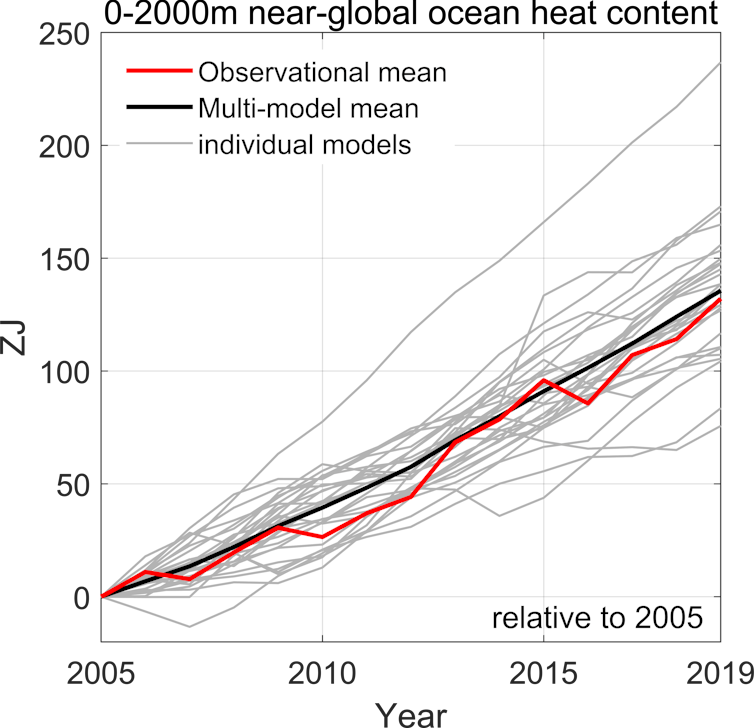

Knowing how much sea levels are likely to rise during this century is vital to our understanding of future climate change, but previous estimates have generated wide ranges of uncertainty. In our research, published today in Nature Climate Change, we provide an improved estimate of how much our oceans are going to warm and its contribution to sea level rise, with the help of 15 years’ worth of measurements collected by a global array of autonomous underwater sampling floats.

Our analysis shows that without dramatic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, by the end of this century the upper 2,000 metres of the ocean is likely to warm by 11-15 times the amount of warming observed during 2005-19. Water expands as it gets warmer, so this warming will cause sea levels to rise by 17-26 centimetres. This is about one-third of the total projected rise, alongside contributions from deep ocean warming, and melting of glaciers and polar ice sheets.

Ocean warming is a direct consequence of rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere as a result of our burning of fossil fuels. This results in an imbalance between the energy arriving from the Sun, and the energy radiated out into space. About 90% of the excess heat energy in the climate system over the past 50 years is stored in the ocean, and only about 1% in the warming atmosphere.

Warming oceans cause sea levels to rise, both directly via heat expansion, and indirectly through melting of ice shelves. Warming oceans also affect marine ecosystems, for example through coral bleaching, and play a role in weather events such as the formation of tropical cyclones.

Systematic observations of ocean temperatures began in the 19th century, but it was only in the second half of the 20th century that enough observations were made to measure ocean heat content consistently around the globe.

Since the 1970s these observations indicate an increase in ocean heat content. But these measurements have significant uncertainties because the observations have been relatively sparse, particularly in the southern hemisphere and at depths below 700m.

To improve this situation, the Argo project has deployed a fleet of autonomous profiling floats to collect data from around the world. Since the early 2000s, they have measured temperatures in the upper 2,000m of the oceans, and sent the data via satellite to analysis centres around the world.

These data are of uniform high quality and cover the vast majority of the open oceans. As a result, we have been able to calculate a much better estimate of the amount of heat accumulating in the world’s oceans.

The global ocean heat content continued to increase unabated during the temporary slowdown in global surface warming in the beginning of this century. This is because ocean warming is less affected than surface warming by natural yearly fluctuations in climate.

Read more: Ocean depths heating steadily despite global warming 'pause'

Current Observations, Future Warming

To estimate future ocean warming, we need to take the Argo observations as a basis and then use climate models to project them into the future. But to do that, we need to know which models are in closest agreement with new, more accurate direct measurements of ocean heat provided by the Argo data.

The latest climate models, used in last month’s landmark report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, all show ocean warming over the period of available Argo observations, and they project that warming will continue in the future, albeit with a wide range of uncertainties.

Read more: Explainer: what is climate sensitivity?

By comparing the Argo temperature data for 2005-19 with the simulations generated by models for that period, we used a statistical approach called “emergent constraint” to reduce uncertainties in model future projections, based on information about the ocean warming we know has already occurred. These constrained projections then provided an improved estimate of how much heat energy will accumulate in the oceans by the end of the century.

By 2081–2100, under a scenario in which global greenhouse emissions continue on their current high trajectory, we found the upper 2,000m of the ocean is likely to warm by 11-15 times the amount of warming observed during 2005-19. This corresponds to 17–26cm of sea level rise from ocean thermal expansion.

Climate models can also make predictions based on a range of different future greenhouse gas emissions. Strong emissions reductions, consistent with bringing surface global warming to within about 2℃ of pre-industrial temperatures, would reduce the projected warming in the upper 2,000m of the ocean by about half — that is, between five and nine times the ocean warming already seen in 2005-19.

This would equate to 8-14cm of sea level rise due to thermal expansion. Of course, reducing emissions so as to hit the more ambitious Paris target of 1.5℃ surface warming would reduce these impacts even further.

Other Factors Linked To Sea Levels

There are several other factors that will also drive up sea levels, besides the heat influx into the upper oceans investigated by our research. There is also warming of the deep ocean below 2,000m, which is still under-sampled in the current observing system, as well as the effects of melting from glaciers and polar ice sheets.

This indicates that even with strong policy action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the oceans will continue to warm and sea levels will continue to rise well after surface warming is stabilised, but at a much reduced rate, making it easier to adapt to the remaining changes. Cutting greenhouse gas emissions earlier rather than later will be more effective at slowing ocean warming and sea level rise.

Read more: If we stopped emitting greenhouse gases right now, would we stop climate change?

Our improved projection is founded on a network of ocean observations that are far more extensive and reliable than anything available before. Sustaining the ocean observing system into the future, and extending it to the deep ocean and to areas not covered by the present Argo program, will allow us to make more reliable climate projections in the future.![]()

Kewei Lyu, Postdoctoral Researcher in Ocean and Climate, CSIRO; John Church, Chair Professor, Climate Change Research Centre, UNSW, and Xuebin Zhang, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Bloody fool!’: why Ripper the musk duck, and many other talkative Aussie birds, are exciting biologists

Recently, two native Australian birds have stolen the limelight with their impressive vocal imitations.

A superb lyrebird called Echo at Sydney’s Taronga Zoo has produced a painfully realistic vocal rendition of a human baby crying. Lyrebirds are already world-famous for their astonishingly accurate vocal mimicry, but these new recordings show their abilities can still surprise.

Then a new paper announced the arrival of an unexpected newcomer to Australia’s vocal imitation scene. A male musk duck (Biziura lobata) named Ripper was recorded imitating two stereotypical Australian sounds: a loudly shutting gate and a person exclaiming “you bloody fool!”.

The gate sound, at least, proved a hit with one of Ripper’s male colleagues who also ended up mimicking the sound. Excitingly, these recordings — originally from the 1980s and dug out from archives — provide the first material evidence of any duck species copying a sound in its environment, disrupting current understandings of the evolution of vocal learning in birds.

So what’s the big fuss about crying and swearing birds?

Why Musk Ducks Are Odd

Vocal production learning is a highly specialised trait that’s rare among animals. It requires flexible and sophisticated control over vocal production, and can be associated with enlarged regions of the brain relative to non-vocal learners.

For a long time, the only other animals known to possess similar vocal learning abilities to humans were parrots and male songbirds. But today, the musk duck joins a broad, but relatively small, list of non-human animals capable of vocal learning, including some bats, elephants, dolphins, whales and seals. Belatedly, we can now add female songbirds to the list of vocal production learners.

The loquacious “Ripper” was a captive-reared male musk duck at the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve near Canberra. When he hatched, with the help of a foster bantam hen, he was the only musk duck there.

But even in the wild, musk ducks are odd. Male musk ducks are up to three times larger than females and have a distinctive bulbous lobe of skin hanging from their bills. Their name comes from the musky smell emitted by dominant males.

In the breeding season, males group together (in “leks”) and perform an exciting aquatic courtship displays for females, performing both day and night. Each male performs a structured, audio-visual display with his tail over his back, inflating his throat lobe, and splashing water while whistling loudly.

In the wild, male display whistles seem to form local dialects — a signature of vocal learning. But this doesn’t involve imitations of other species.

Ripper produced many elements of wild display, but would avidly display to people. His bizarre mimicry of anthropogenic sounds formed part of this display.

Mimicking In Captivity

The story of Ripper is part of a long scientific tradition. Captive-reared parrots and some songbirds mimicking human speech feature in ancient European writings, including the works of Aristotle and Pliny the Elder.

More recently, the possible complexities of parrot communication were explored in a pioneering study of “Alex”, the captive African grey parrot, who had a vocabulary of more than 100 words.

By and large, such accounts of human imitations involve a captive individual raised in isolation from others of its own kind, but in close association with a human caretaker. The human caretaker then becomes the social model for the captive bird’s vocal development.

So while these examples reveal an animal’s capacity for vocal production learning, they don’t show that wild animals imitate sounds from their environment. Indeed, very few of the animal species that mimic people in captivity produce anything other than their own, species-specific vocalisations in the wild.

However, this is not true of Australia’s lyrebirds and other avian vocal mimics.

Mimicry In Wild Australia

Two lyrebird species are famous for the diversity and accuracy of their vocal mimicry: the superb lyrebird of the wet eucalypt forests of southeast Australia, and the Albert’s lyrebird of Australia’s subtropical east.

In captivity, male superb lyrebirds have been recorded mimicking anthropogenic sounds ranging from chainsaws, emergency vehicle sirens to this new recording of a crying human baby.

In the wild, both males and females are proficient mimics of the vocalisations and wingbeats of other bird species — and occasionally mammals. A single individual male superb lyrebird can even mimic a flock of alarm-calling birds.

Despite many rumours, it remains a bit of a mystery when and how often wild lyrebirds mimic sounds of human origin.

Lyrebirds aren’t the only ones. Australia is the lucky home to a surprisingly large number of songbird species that regularly mimic in the wild, from tiny thornbills to the large enigmatic bowerbirds that, even in the wild, occasionally produce startlingly accurate renditions of humans.

Read more: The mimics among us — birds pirate songs for personal profit

But not all mimics are what they seem. In a heartbreaking example, the mimetic song of the Regent honeyeater is both a consequence and a cause of the species’ decline. Wild males copy other species because there aren’t enough males left to pass on their song to the next generation.

Threatened Archival Treasures

Ripper the swearing musk duck, Echo the bawling lyrebird, and the forgotten songs of the Regent honeyeater show us how much we still have to discover about Australia’s extraordinary birds. Far from being the biogeographical oddity, Australian birds are still destabilising biological theory.

Ripper was a bird of the 80s, and we only know of his bizarre mimicry because Rippers’ recordist, Dr Peter Fullagar, was on a mission to establish a natural history sound archive for Australia. Like all good 80s singers, Ripper was recorded on cassette tape before Peter digitised it.

It’s only from historical archives that researchers could discover that original song of the Regent honeyeater was unique to the species and more elaborate than the songs of contemporary males. Simply listening to captive-reared birds or the dwindling singers in the wild is no longer enough to reveal the Regent honeyeater’s natural song: the baseline has shifted.

What other treasures lie gathering dust in forgotten sheds or library stacks? We must be quick, before those cassette tapes degrade too far to be heard.

Read more: Only the lonely: an endangered bird is forgetting its song as the species dies out ![]()

Anastasia Dalziell, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Wollongong and Justin A. Welbergen, President of the Australasian Bat Society | Associate Professor in Animal Ecology, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We managed to toilet train cows (and they learned faster than a toddler). It could help combat climate change

Can we toilet train cattle? Would we want to?

The answer to both of these questions is yes — and doing so could help us address issues of water contamination and climate change. Cattle urine is high in nitrogen, and this contributes to a range of environmental problems.

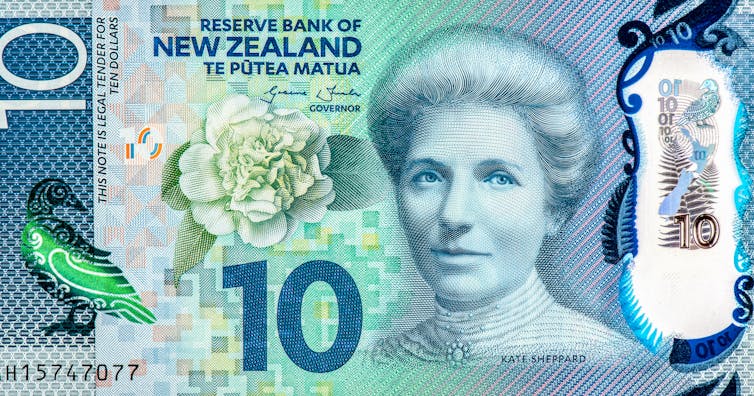

When cows are kept mainly outdoors, as they are in New Zealand and Australia, the nitrogen from their urine breaks down in the soil. This produces two problematic substances: nitrate and nitrous oxide.

Nitrate from urine patches leaches into lakes, rivers and aquifers (underground pools of water contained by rock) where it pollutes the water and contributes to the excessive growth of weeds and algae.

Nitrous oxide is a long-lasting greenhouse gas which is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. It accounts for about 12% of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions, and much of this comes from the agricultural sector.

When cows are kept mainly in barns, as is the case in Europe and North America, another polluting gas — ammonia — is produced when the nitrogen from urine mixes with faeces on the barn floor.

However, if some of the urine produced by cattle could be captured and treated, the nitrogen it contains could be diverted, and the environmental impacts reduced. But how might urine capture be achieved?

We worked on this problem with collaborators from Germany’s Federal Research Institute for Animal Health and Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology. Our research is published today in the journal Current Biology. It forms part of our colleague Neele Dirksen’s PhD thesis.

Read more: Feeding cows a few ounces of seaweed daily could sharply reduce their contribution to climate change

Toilet Training (But Without The Nappies)

In our research project, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation, we applied principles from behavioural psychology to train young cattle to urinate in a particular place — that is, to use the “toilet”

Behavioural psychology tells us a behaviour is likely to be repeated if followed by a reward, or “reinforcer”. That’s how we train a dog to come when called.

So if we want to encourage a particular behaviour, such as urinating in a particular place, we should reinforce that behaviour. For our project we applied this idea in much the same way as for toilet training children, using a procedure called “backward chaining”.

First, the calves were confined to the toilet area, a latrine pen, and reinforced with a preferred treat when they urinated. This established the pen as an ideal place to urinate.

The calves were then placed in an alley outside the pen, and once again reinforced for entering the pen and urinating there. If urination began in the alley, it was discouraged by a mildly unpleasant spray of water.

After optimising the training, seven out of the eight calves we trained learned to urinate in the latrine pen — and they learned about as quickly as human children do.

The calves received only 15 days of training and the majority learned the full set of skills within 20 to 25 urinations, which is quicker than the toilet-training time for three- and four-year-old children.

This showed us two things that weren’t known before.

- cattle can learn to attend to their own urination reflex, because they moved to the pen when ready to use it

- cattle will learn to withhold urination until they’re in the right place, if they’re rewarded for doing so.

The Next Stages

Our research is a proof of concept. Cattle can be toilet trained, and without much difficulty. But scaling up the method for practical application in agriculture involves two further challenges, which will be the focus in the next stage of our project.

First, we need a way both to detect urination in the latrine pen and deliver reinforcement automatically — without human intervention.

This is probably no more than a technical problem. An electronic sensor for urination wouldn’t be difficult to develop, and small amounts of attractive rewards could be provided in the pen.

Apart from this, we’ll also need to determine the optimal location and number of latrine pens needed. This is a particularly challenging issue in countries such as New Zealand, where cattle spend most of their time in open paddocks rather than barns.

Part of our future research will require understanding how far cattle are willing to walk to use a pen. And more needs to be done to understand how to best use this technique with animals in both indoor and outdoor farming contexts.

What we do know is that nitrogen from cattle urine contributes to both water pollution and climate change, and these effects can be reduced by toilet training cattle.

The more urine we can capture, the less we’ll need to reduce cattle numbers to meet emissions targets — and the less we’ll have to compromise on the availability of milk, butter, cheese and meat from cattle.

Read more: Virtual fences and cattle: how new tech could allow effective, sustainable land sharing ![]()

Douglas Elliffe, Professor of Psychology, University of Auckland, University of Auckland and Lindsay Matthews, Honorary Academic, Psychology Department, University of Auckland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Saving these family-focused lizards may mean moving them to new homes. But that’s not as simple as it sounds

Am I not pretty enough? This article is part of The Conversation’s series introducing you to unloved Australian animals that need our help.

Spiny-tailed skinks (Egernia stokesii badia), known as meelyu in the local Badimia language in Western Australia, are highly social lizards that live together in family groups — an uncommon trait among reptiles.

They’re culturally significant to the Badimia people but habitat degradation and mining has put them under threat of extinction.

These sturdy, mottled lizards — which live in colonies in the logs of fallen trees and branches — are a candidate for what researchers call “mitigation translocation”.

That’s where wildlife are relocated away from high-risk areas (such as those cleared for urban development or mining) to lower risk areas.

It might sound simple. But research shows these mitigation translocation decisions are often made on an ad hoc basis, without a long-term strategic plan in place.

Not Enough Pre-Planning Or Follow-Up

There has been much research into assisted relocation of larger, charismatic mammals and birds. But other animals, such as reptiles with a less positive social image, have been less widely studied.

Our recent research has found there is often little pre-planning or follow-up to monitor success of mitigation translocations, even though reptile mitigation translocations do take place, sometimes on a large scale.

In fact, fewer than 25% of mitigation translocations worldwide actually result in long-term self-sustaining populations.

Mitigation translocation methods are also not being improved. Fewer than half of published mitigation translocation studies have explicitly compared or tested different management techniques.

Mitigation translocation studies also rarely consider long-term implications such as how relocated animals can impact the site to which they are moved — for example, if the ecosystem has limited capacity to support the relocated animals.

But it’s not just about ecosystem benefits. Preservation of species such as meelyu also has cultural benefits — but mitigation translocation can only be part of the solution if it’s done strategically.

Read more: Hundreds of Australian lizard species are barely known to science. Many may face extinction

The Meelyu: A Totem Species

As part of Holly Bradley’s research into understanding how to protect meelyu from further loss in numbers, she had the privilege to meet with Badimia Indigenous elder, Darryl Fogarty, who identified meelyu as his family’s totem.

Totemic species can represent a person’s connection to their nation, clan or family group.

Unfortunately, Darryl Fogarty cannot remember the last time he saw the larger meelyu in the area. The introduction of European land management and feral species into Western Australia has upset the ecosystem balance — and this also has cultural consequences.

Preserving totemic fauna in their historic range can be a critical component of spiritual connection to the land for Indigenous groups in Australia.

In the past, this spiritual accountability for the stewardship of a totem has helped protect species over the long term, with this responsibility passed down between generations.

Before European colonisation, this traditional practice helped to preserve biodiversity and maintain an abundance of food supplies.

A strategic approach to future meelyu relocations from areas of active mining is crucial to prevent further population losses — for both ecological and cultural reasons.

Good Mitigation Translocation Design

If we are to use mitigation translocation to shore up their numbers, we need effective strategies in place to boost the chance it will actually help the meelyu.

Good mitigation translocation design includes factors such as:

selecting a good site and understanding properly whether it can support new wildlife populations

having a good understanding of the animal’s ecological needs and how they fit with the environment to which they’re moving

using the right methods of release for the circumstances. For example, is it better to use a soft release method, where an individual animal is gradually acclimatised to its new environs over time? Or a hard release method, where the animal is simply set free in its new area?

having a good understanding of the cultural factors involved.

A Holistic Approach

A holistic approach to land management and restoration practice considers both cultural and ecological significance.

It supports the protection and return of healthy, functioning ecosystems — as well as community well-being and connection to nature.

Mitigation translocation could have a role to play in protection of culturally significant wildlife like the meelyu, but only when it’s well planned, holistic and part of a long term strategy.

Read more: Photos from the field: Australia is full of lizards so I went bush to find out why ![]()

Holly Bradley, PhD candidate, Curtin University; Bill Bateman, Associate professor, Curtin University, and Darryl Fogarty, Badimia Elder, Indigenous Knowledge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Research reveals why pet owners keep their cats indoors – and it’s not to protect wildlife

Cat owners are urged to keep their pet indoors for a variety of reasons, including protecting wildlife and preventing the spread of disease. But our research has found an entirely different motivator for containing cats.

Concern for their cat’s safety is the primary reason people keep cats inside. And people who allow cats to roam are also motivated by concern for the animal’s well-being.

Keeping domestic cats properly contained is crucial to protecting wildlife. Cats are natural predators – even if they’re well fed. Research last year found each roaming pet cat kills 186 reptiles, birds and mammals per year.

If we want more domestic cats kept indoors, it’s important to understand what motivates cat owners. Our research suggests messages about protecting wildlife are, on their own, unlikely to change cat owners’ behaviour.

Why Keep Your Cat Indoors?

Cat containment involves confining the animals to their owners’ premises at all times.

In the Australian Capital Territory, cat containment is mandatory in several areas. From July next year, all new cats must be contained across the territory, unless on a leash.

In Victoria, about half of local councils have some form of cat containment legislation. Current revisions to Domestic Animal Management Plans could mean the practice becomes more widespread.

Read more: One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

Cats have long been part of human societies and play an important social role in their owners’ lives. But our affection for the animals means efforts to keep cats contained can be met with opposition.

Officials, conservation groups and others put forward a range of reasons for containing cats, including:

preventing cats from spreading diseases and parasites such as toxoplasmosis to both people and wildlife

reducing threats to wildlife, especially at night

reducing unwanted cat pregnancies

avoiding disputes with neighbours, including noise complaints, and cats defecating or spraying in garden beds and children’s sandpits

protecting cats from injury or death - such as being hit by a vehicle, attacked by dogs, snake bite and exposure to diseases and parasites.

So which argument is most persuasive? Our research suggests it’s the latter.

What We Found

We surveyed 1,024 people in Victoria – 220 of whom were cat owners.

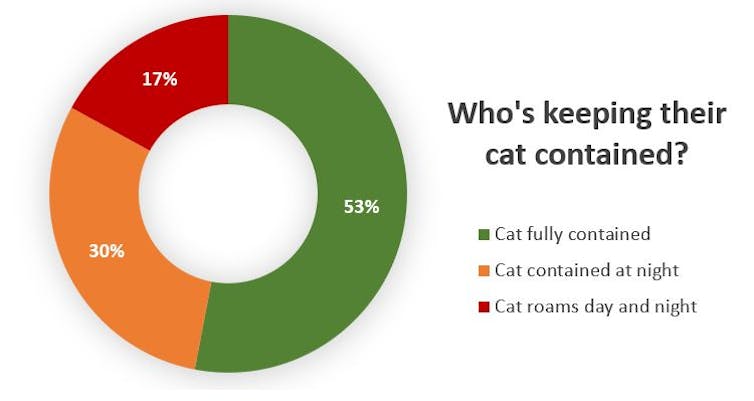

We found 53% of cat owners did not allow roaming. These people were more likely to hold concerns about risks to cats’ safety than cat owners who allowed roaming. They were also less likely to believe cats have a right to roam.

Some 17% of cat owners allowed their cats unrestricted access to the outdoors day and night, while 30% contained their cats at night but allowed some unrestricted outdoor access during the day.

Both cat owners and other respondents generally believed cat owners should manage their pet’s roaming behaviour. But for cat owners, concern about harm to wildlife was not a significant predictor of containment behaviour.

Instead, people who keep their cats contained were more likely to be worried that their cat might be lost, stolen, injured or killed.

It’s not that cat owners don’t care about native animals - only about one in ten cat owners said they’d never seriously considered how their cat affects wildlife. But our survey results show this isn’t a big motivation for keeping cats indoors.

Roaming Is Dangerous

A roaming lifestyle can be risky to cats. A 2019 study of more than 5,300 Australian cat owners found 66% had lost a cat to a roaming incident such as a car accident or dog attack, or the cat simply going missing.

Despite the risks, people who let their cats roam are more likely to think the practice is better for the animal’s well-being – for example, that hunting is normal cat behaviour.

Owners who let their cat roam were more likely than those who contained their cat to believe their cat did not often hunt. While not all cats kill wildlife, those that do typically only bring home a small proportion of their catch. That means owners can be unaware of their cats’ impact.

Cat owners must be made aware of the risks of roaming and equipped with the tools to keep their cats happy and safe at home. Unfortunately, research shows many Australian cat owners are not providing the safe environment and stimulation their cat needs when contained.

Cat containment doesn’t have to mean keeping the animal permanently in the house – nor does it require building them a Taj Mahal on the patio.

Cats can be outside while supervised or walked on leash. You can also cat-proof your backyard fence to keep them in.

Resources such as Safe Cat Safe Wildlife help owners meet their cat’s mental, physical and social needs while keeping them contained.

Changing Containment Behaviour

Our study shows cat containment campaigns can be more effective if messaging appeals to owners’ concern for their cats’ well-being. These messages could be delivered by trusted people such as vets.

Helping owners understand that cats’ needs can be met in containment, and giving them the tools to achieve this, may be the best way to protect wildlife.

Demonising cats is not the answer. The focus must shift to the benefits of containment for cats’ well-being if we hope to achieve a cat-safe and wildlife-safe future.

Read more: I've always wondered: can I flush cat poo down the toilet? ![]()

Lily van Eeden, Postdoctoral research fellow, Monash University; Emily McLeod, PhD Candidate, Queensland University of Technology; Fern Hames, Director, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, and Zoe Squires, Policy Officer, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change is coming for your snacks: why repeated drought threatens dried fruits and veggies

Potatoes can become more brittle, apples may be harder to dehydrate, and sultanas might be off the menu altogether — these are possible outcomes of recurring and intensifying droughts under climate change in Australia.

It might sound counter-intuitive, but drier conditions can affect the quality of fruit and vegetables at a cellular level, making them harder to process into dried foods. This has big implications for Australia’s food security and economy.

Dried foods account for a significant portion of our diet, and Australia exports around 70% of its produce, which is valued at close to A$49 billion per year. Dried produce make up an important part of this — for example, the export value of sultanas, currants and raisins alone in 2018-19 was $25.1 million.

If the taste, quality or availability of dried foods declines, we risk losing these lucrative markets. But my ongoing research on advanced drying methods aims to help overcome this challenge by carefully controlling how cells change their shape and structure.

Droughts Are Set To Get Worse

The most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned Australia will become more arid as the world warms, bringing more droughts, drier soils, mass tree deaths and more.

The recent droughts across much of eastern Australia have already shown how climate change can wreak havoc on plant produce, as well as society and economy. For example, due to climate change impacts, agricultural profits fell by 23% over the period 2001-2020, or around $29,200 per farm, compared to historical averages.

Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that uncertain environmental, social and economic conditions can lead to panic buying, highlighting the importance of food security and the stability of food supply.

It’s important to ensure our dried food supply is up to future stockpiling challenges, as chips and dried fruits are a staple of many diets in Australia. In 2019-2020, dried fruit such as sultanas, dried apple and apricots accounted for 12% of total fruit serves in the country.

How Drought Affects Dried Foods

Australian produce can be dried either in Australia or overseas, depending on the food type, manufacturer and the associated costs.

During the drying process, the cellular structure of fruit and vegetables go through significant changes. Cells and tissues can change their shape while shrinking into more compact forms.

If the drying process is not carefully controlled, it can lead to undesirable properties affecting the food’s taste and appearance, potentially reducing the market value and nutritional quality.

This is how drought makes things difficult. We know drought leads to water shortages in lakes and rivers, but research suggests it also dries out small plant cells and tissues.

If the absence of water in cells is ongoing — due to repeating droughts — the micro-properties of plants and their produce can change in the long term, whether the plants are grown in a large farm spanning hectares or in a small pot in your backyard.

Recurring droughts can make fruit and vegetables “fatigued” even before they’re harvested. This means the structure of the plant weakens with every drought, a bit like how bending a metal wire repeatedly eventually causes it to break.

For example, droughts can make plants, such as apples, more brittle and therefore un-processable. Droughts can also directly lead to smaller plants and respective harvests.

If the drought conditions are extreme, the moisture loss in the plants can be severe and the cells can naturally get damaged even without any further processing. In other words, if the recurring drought conditions are here to stay, dried foods such as potato chips, sultanas and dried apple as we know them could change for good.

Solving This Problem With Supercomputing

So, we know produce affected by drought is not as easy to process, often tastes different and is sometimes not usable at all. But what can we do about it?

Obviously, if climate change and subsequently recurring droughts could be avoided, the adverse effects on the dried food could also be dodged. First and foremost, global emissions must be rapidly and urgently cut.

Read more: Climate change means Australia may have to abandon much of its farming

But what if we can’t avoid it? In this case, we will need a sound Plan B.

One of the promising questions Australian researchers and engineers like me have asked is: can we modify the drying processes to match the changed properties of drought-affected produce? Doing so might enable the dried food processing industry to maintain the quality, taste, appearance and market value of its products.

But it won’t be easy. First, we need to correctly understand the exact nature of shape and size changes in plant cells, as affected by the lack of water. This is challenging, and requires computer simulations and supercomputing technologies.

Through these simulations, it’s possible to estimate if the cells are going to be damaged when they go through the drying process. If we find there’ll be serious damage, the simulations can provide information on the ideal drying conditions. This means we can optimise the temperature, pressure, humidity and drying time to minimise the adverse effects.

This approach can lead to significant savings of time, money and energy while leading to increased quality and shelf life of dried food. With more research, extended computer modelling and simulations can lead to advanced drying on an industrial scale, leading to stronger food security and stability.

So, even if we will have to deal with more frequent and more intense droughts in the near future, the taste of your potato chips might be as good as ever, after all.

Charith Rathnayaka, Lecturer in Mechanical Engineering, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham's Beach

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

What’s Age Got To Do With It? (2021)

September 14, 2021

A new report released today by the Australian Human Rights Commission has found most Australians (90%) agree ageism exists in Australia, with 83% agreeing ageism is a problem and 65% saying it affects people of all ages.

These findings were included in the Commission’s latest report, led by Age Discrimination Commissioner Dr Kay Patterson AO, What’s age got to do with it? A snapshot of ageism across the Australian lifespan.

The report found ageism remains the most accepted form of prejudice in Australia, with 63% having experienced ageism in the last five years.

“Ageism is arguably the least understood form of discriminatory prejudice, with evidence suggesting it is more pervasive and socially accepted than sexism or racism,” Dr Patterson said.

The research was undertaken by the Commission in 2020 and 2021 to explore what Australians think about age and ageism across the adult lifespan. It found ageism is experienced in different ways:

- Young adults (18-39) are most likely to experience ageism as being condescended to or ignored, particularly at work.

- Middle-aged people (40-61) are most likely to experience ageism as being turned down for a job.

- Older people (62+) are more likely to experience ageism as being ‘helped’ without being asked.

It also shows the generations have much in common – but that there are ongoing tensions, which arise from stereotypes held by one generation about another. When these were questioned, most Australians rejected the stereotype, with:

- 70% of Australians disagreeing that today’s older generation is leaving the world in a worse state than it was before, and

- fewer than 20% agreeing any age group was a burden on their family or a burden on society.