inbox and environment news: Issue 512

October 3 - 9, 2021: Issue 512

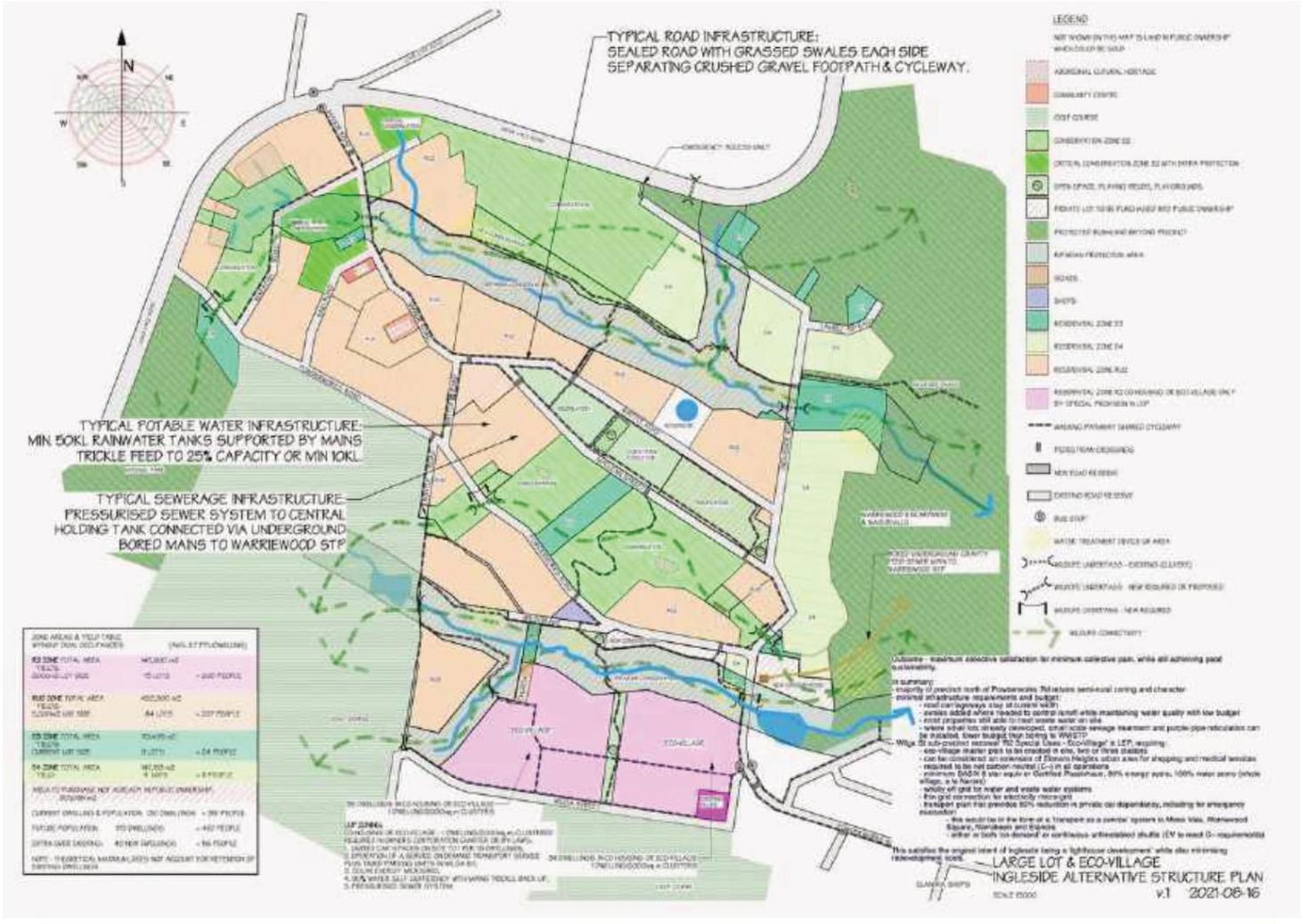

Ingleside Precinct Update: Alternative Proposed

Watch Out!: Baby Birds Are About In Warriewood Wetlands

Protected Pittwater Spotted Gum Poisoned In Palmgrove Road

Crescent Reserve Newport: Vandalism By Trail Bikers Destroys 24 Years Of Work By Volunteers

Trafalgar Park Newport: Erosion, Soil Runoff Post Concrete Path Installation

Avalon Preservation Association 2021 AGM

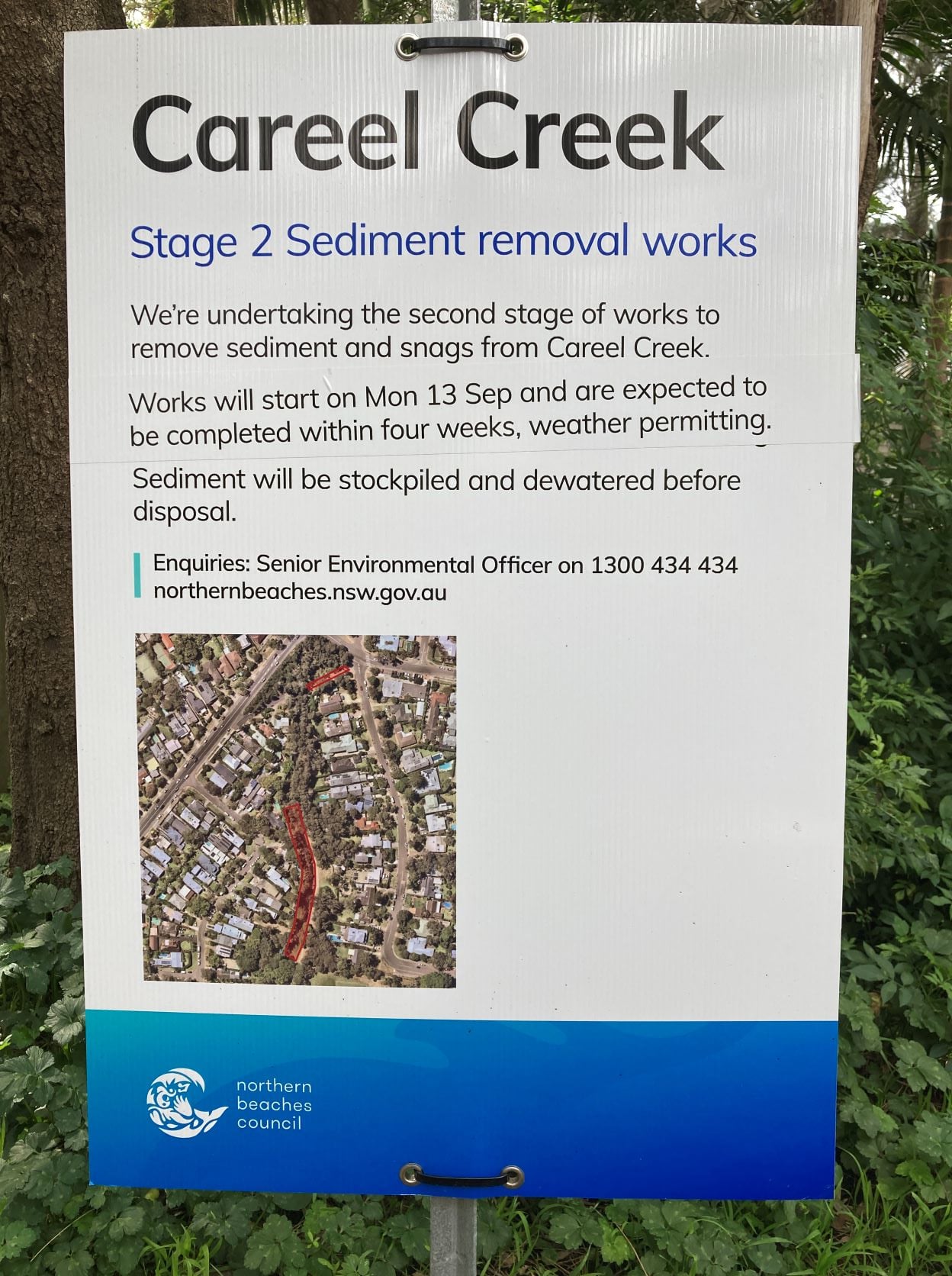

APA Careel Creek Sediment Removal Works Update

- - the removal of weeds, such as Phoenix palms with the need to reduce erosion of the banks of the creek; and,

- - the retention of mangroves with the need to permit adequate water flow.

- - stabilise the banks with indigenous planting;

- - replace weeds with indigenous planting; and

- - remove snags from the creek to enable water flow.

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

Save Sydney's Koala Update: Black Day For Sydney’s Last Koala Population

Point And Focus On Hawkesbury River For World Rivers Day

World’s Largest Shark Management Program Deployed To NSW Beaches

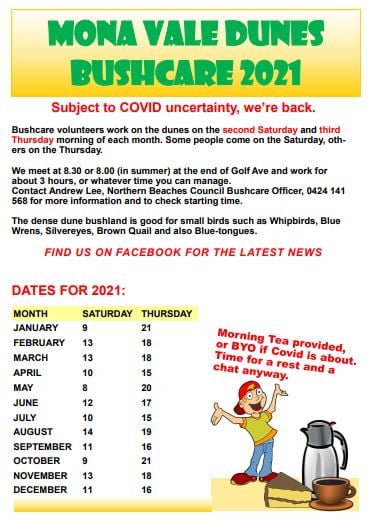

Aussie Backyard Bird Count 2021

The 2021 event will run from October 18‒24 during National Bird Week. Register as a counter today at: https://aussiebirdcount.org.au/

The Aussie Backyard Bird Count is one of Australia’s biggest citizen science events. This year is our eighth count, and we’re hoping it will be our biggest yet!

Join thousands of people around the country in exploring your backyard, local park or favourite outdoor space and help us learn more about the birds that live where people live.

Taking part in the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is a great way to connect with the birds in your backyard, no matter where your backyard happens to be. You can count in a suburban garden, a local park, a patch of forest, down by the beach, or the main street of town.

To take part, register on the website today, then during the count you can use the web form or the app to submit your counts. Just enter your location and get counting ‒ each count takes just 20 minutes!

Not only will you be contributing to BirdLife Australia's knowledge of Aussie birds, but there are also some incredible prizes on offer.

Head over to the Aussie Backyard Bird Count website to find out more.

NPWS Concerned Over Increased Dog Walking In National Parks

250 Million Dollar Allocated For Carbon Capture, Use And Storage Hubs And Technologies

- $100 million will support the design and construction of carbon capture hubs and shared infrastructure, and

- $150 million will support research and commercialisation of carbon capture technologies and identify viable carbon storage sites.

Hydrogen Industry 150 Million Dollar Boost

2 Billion Dollar Loan Facility For Australia's Minerals Sector

21 Million For Gas From North Bowen And Galilee Basins Developers

- $15.7 million for gas field trials including innovative drilling programs to prove the region’s potential; and

- $5 million for studies to support development of a new gas pipeline to the region, co-funded by the Queensland government.

- $14 million for Geoscience Australia and CSIRO to deliver better data about baseline conditions across each of the Government’s priority strategic basin regions;

- $13.7 million to continue research under the CSIRO’s GISERA (Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance); and

- More than $370 million for various road upgrades to support supply chains, trade and project construction, through the Northern Australia Roads program, Roads of Strategic Importance initiative and the Regional Economic Enabling Fund

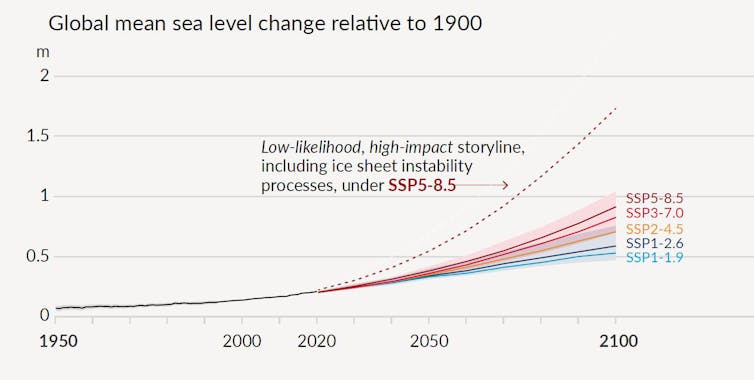

NSW Raises Climate Targets; Federal Government Keeps Announcing Billions Of Taxpayer Dollars To Be Used For Gas Fracking And Coal Mining Expansion

NSW Set To Halve Emissions By 2030

No Need For Narrabri Gas: New Report’s Roadmap Good News For Rural Communities If Acted On

- Gas demand within New South Wales could be 70 percent lower as soon as 2030, and eliminated altogether as soon as 2050, using readily available, commercially viable technologies.

- With the right policies in place to support technologies like electric resistance heating and renewable hydrogen, gas use can be reduced in emissions-intensive industries like iron and steel manufacturing.

- Homes and commercial buildings are responsible for almost half of New South Wales’ gas use and meeting their needs with electricity is readily achievable with existing, commercially available technologies.

- Putting common-sense measures in place to reduce gas demand in New South Wales, such as electrifying homes and upgrading commercial buildings, would make the expensive and polluting Narrabri Gas Project redundant.

- There is no shortage of gas anywhere in Australia with the growing demands of a swollen gas export industry driving supply issues, higher energy bills, and worsening climate change.

- It is critically important for our economy, health, and climate that every state and territory transitions away from fossil fuels like gas as quickly as possible.

NSW Government Plan To Revitalise Peat Island And Mooney Mooney Released

- Nearly 270 new homes at Mooney Mooney to deliver more housing supply,

- Retention of nine unlisted historical buildings on the island, and four on the mainland, to be restored and used for new community and commercial opportunities,

- New retail and café or restaurant opportunities,

- Approximately 9.65 hectares of open space, including opportunities for walking and cycling tracks, parklands and recreational facilities,

- Retention of the chapel and surrounding land for community use, and

- 10.4 hectares of bushland dedicated as a conservation area.

New Western Sydney National Park To Lead Fight Against Extinction

- brown antechinus

- eastern bettong

- eastern quoll

- southern long-nosed bandicoot

- New Holland mouse

- brush-tailed phascogale

- common dunnart

- bush rat

- emu

- koala

- bush stone-curlew

- green and golden bell frog

- Yathong Nature Reserve, near Cobar Central NSW, fenced area approximately 40,000 hectares

- Ngambaa Nature Reserve, near Macksville North-east NSW, fenced area approximately 3000 hectares

- South-east NSW (Eden Bombala Region), estimated fenced area approximately 1500 – 2000 hectares

- Pilliga State Conservation Area, near Baradine North-west NSW, fenced area 5800 hectares

- Sturt National Park, near Tibooburra Far North-west NSW, fenced area 4000 hectares

- Mallee Cliffs National Park, near Buronga South-west NSW, fenced area 9570 hectares

The Good, The Bad, The Ugly - Extinction Risk Report Can Inform Conservation Of Australia's Sharks And Rays

Ley Approves Vickery Coal Mine Until December 2051 Despite Supreme Court Appeal On Foot

New Fracking-Industry Influenced Report Toes Government Line On Gas

Pitt Wastes More Public Cash On QLD Gas While Tourism Misses Out

Precious Wildlife Habitat Is Still Woefully Vulnerable Despite New Conservation Scheme

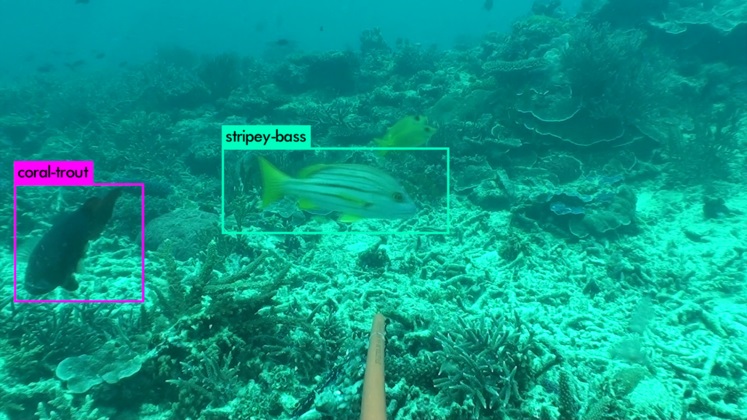

Automated Fish Counting System To Benefit Ecology And Fisheries Industry

Researchers from the Curtin Institute for Computation (CIC) will use the latest in data science to develop an automated fish detection and counting solution that offers exciting economic and ecological benefits. The CIC is part of a consortium that has been awarded $1 million in Federal funding to continue developing the AFID (Automated Fish Identification) system, which uses machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to automatically gather information about fish, including species and size.

Researchers from the Curtin Institute for Computation (CIC) will use the latest in data science to develop an automated fish detection and counting solution that offers exciting economic and ecological benefits. The CIC is part of a consortium that has been awarded $1 million in Federal funding to continue developing the AFID (Automated Fish Identification) system, which uses machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to automatically gather information about fish, including species and size.Want to reduce your food waste at home? Here are the 6 best evidence-based ways to do it

From the farm to the plate, the modern day food system has a waste problem. Each year, a third of all food produced around the world, or 1.3 billion tonnes, ends up as rubbish. Imagine that for a moment – it’s like buying three bags of groceries at the supermarket then throwing one away as you leave.

Wasting food feeds climate change. Food waste accounts for more than 5% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions. And this doesn’t include emissions from activities required to actually produce the food in the first place, such as farming and transport.

One of the largest sites of food waste is the home. In Australia, households throw out about 2.5 million tonnes of food each year. That equates to between A$2,000 and $2,500 worth of food per year per household.

But there’s some good news. Our Australian-first research, released today, identified the six most effective behaviours anyone can do to reduce food waste. Combined, these relatively small changes can make a big difference.

What We Did

Food waste by households is a complex problem influenced by many factors. Some, such as food type, package size and safety standards, are out of a consumer’s control. But some are insignificant daily behaviours we can easily change, such as buying too much, forgetting about food at the back of your fridge, not eating leftovers and cooking too much food.

We wanted to better understand the complex nature of household food waste. Together with Australia’s leading food rescue organisation OzHarvest, our research sought to identify and prioritise evidence-based actions to reduce the amount of food Australians throw away.

We reviewed Australian and international literature, and held online workshops with 30 experts, to collate a list of 36 actions to reduce food waste. These actions can be broadly grouped into: planning for shopping, shopping, storing food at home, cooking and eating.

We realised this might be an overwhelming number of behaviours to think about, and many people wouldn’t know where to start. So we then surveyed national and international food waste experts, asking them to rank behaviours based on their impact in reducing food waste.

We also surveyed more than 1,600 Australian households. For each behaviour, participants were asked about:

the amount of thinking and planning involved (mental effort)

how much it costs to undertake the behaviour (financial effort)

household “fit” (effort involved in adopting the behaviour based on different schedules and food preferences in the household).

Consumers identified mental effort as the most common barrier to reducing food waste.

Read more: What a simulated Mars mission taught me about food waste

What We Found

Our research identified the three top behaviours with the highest impact in reducing food waste, which are also relatively easy to implement:

Prepare a weekly meal at home that combines food needing to be used up

Designate a shelf in the fridge or pantry for foods that need to be used up

Before cooking a meal, check who in the household will be eating, to ensure the right amount is cooked.

Despite these actions being relatively easy, we found few Australian consumers had a “use it up” shelf in the fridge or pantry, or checked how many household members will be eating before cooking a meal.

Experts considered a weekly “use-it-up” meal to be the most effective behaviour in reducing food waste. Many consumers reported they already did this at home, but there is plenty of opportunity for others to adopt it.

Some consumers are more advanced players who have already included the above behaviours in their usual routines at home. So for those people, our research identified a further three behaviours requiring slightly more effort:

Conduct an audit of weekly food waste and set reduction goals

Make a shopping list and stick to it when shopping

Make a meal plan for the next three to four days.

Our research showed a number of actions which, while worthwhile for many reasons, experts considered less effective at reducing food waste. They were also less likely to be adopted by consumers. The actions included:

Preserving perishable foods by pickling, saucing or stewing for later use

Making a stock of any food remains (bones and peels) and freeze for future use

Buying food from local specialty stores (such as greengrocers and butchers) rather than large supermarkets.

Read more: Melbourne wastes 200 kg of food per person a year: it's time to get serious

Doing Our Bit

Today is the United Nations’ International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste. It seeks to increase awareness and prompt action in support of a key target in the global Sustainable Development Goals to halve food loss and waste by 2030.

Australia has signed up to this goal, and we hope this research helps fast-track those efforts.

OzHarvest is launching its national Use-It-Up food waste campaign today, aiming to support Australians with information, resources and tips. Based on our findings, we’ve also developed a decision-making tool to help policy makers target appropriate food waste behaviours.

Australia, and the world, can stop throwing away perfectly edible food – but everyone must play their part.

Read more: What can go in the compost bin? Tips to help your garden and keep away the pests ![]()

Mark Boulet, Research Fellow, BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No, Barnaby. The UK energy crisis has nothing to do with its net-zero target, and to suggest otherwise is outrageous

As debate heats up in Australia about adopting a net-zero emissions target, Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce and other key party figures have pointed to the UK energy crisis as a supposedly cautionary tale.

On the ABC’s Insiders program on Sunday, Joyce expressed reticence about the net-zero policy, and said he was “perplexed there’s not more discussion about what’s happening in the UK and Europe with energy prices”. He went on:

A 250% [price] increase since the start of the calendar year. A few days ago, 850,000 people losing their energy provider and a real concern over there about their capacity as they go into winter to keep themselves warm and even keep the food production processes going through.

Joyce was clearly seeking to link the UK energy crisis to its climate target of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. Pro-coal senator Matt Canavan this week echoed the sentiment:

So are they right? To find out, The Conversation approached Aimee Ambrose, Professor of Energy Policy at leading UK policy research centre The Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research, and an expert advisor to the International Energy Agency.

Here, she explains the reasons for the UK energy crisis. And a spoiler alert: the nation’s net-zero target is not to blame.

Comments by Aimee Ambrose, Professor in Energy Policy, Sheffield Hallam University

It’s outrageous to suggest the current UK energy situation is the result of a rapid transition away from fossil fuels. It is primarily a gas crisis, fuelled by the nation’s slow transition to lower carbon sources.

The origins of the crisis are complex, and date back many years. Here are the five main factors at play:

1. Heavy Reliance On Gas

Since the 1970s, the UK has become progressively more reliant on natural gas to heat our homes. Currently, 77% of households heat their homes using gas central heating, delivered to homes via underground pipes.

Until recently, gas (via central heating) has represented the most affordable way to heat homes. Before the crisis, electricity prices in the UK were consistently higher than gas, averaging 16p per kilowatt hour for electricity (versus 4p for gas). Gas is also used as a key fuel in UK electricity generation.

So gas was seen as affordable, reserves are plentiful in the North Sea and it’s a cleaner energy source than burning solid fuels such as coal. The UK put all its energy eggs in one basket, leaving us at the mercy of price shocks.

2. Lack Of Diversity Of Renewable Sources

Now let’s zoom out from home heating and look at the overall energy mix for the UK. The lack of diversity, and associated risks to energy security, are very clear.

Natural gas fairly consistently makes up about 40% of the energy mix, oil about the same, renewables (primarily wind) about 15% followed by a small amount of nuclear energy and an even smaller amount of coal-based generation (although these figures can fluctuate quite significantly).

These statistics lay bare the UK’s heavy dependency on gas and oil and tardy progress towards a shift to renewables.

The above figure for renewable energy production looks more rosy than it is, thanks to very high wind energy output in Scotland. In reality, total renewable energy generation in the UK lags behind many neighbours in Europe.

Greater renewable energy generation, from diverse technologies, would reduce the UK’s reliance on gas. But within the renewables sector, the UK has majored in wind power – again putting our eggs in one basket.

And even in relation to wind, our flagship renewable source, we lag far behind Europe in terms of output.

3. Brexit

The UK’s exit from Europe last year also appears to have played a part in the crisis.

Gas prices in Europe are at record highs, but the European Union’s internal energy market – of which the UK is no longer part – allows member states to trade with each other in a way that balances prices out.

This means EU countries can’t always take full advantage of very low energy prices, but at the same time means they’re protected from very high prices.

The UK, as an independent country outside the internal EU market, can take better advantage of low energy prices. But at times like these, when energy prices are very high, it left highly exposed to price shocks.

4. Regressive Approaches To Funding Low-Carbon Transitions

In the UK, as with much of the EU, energy transitions are funded by energy consumers via a levy on their energy bills. Around 63% of our energy bills are made up of charges to fund new energy infrastructure and other services provided by energy companies.

This means those who spend a higher proportion of their income on energy (such as lower income households) will contribute more to funding the transition away from fossil fuels than their wealthier counterparts.

This is not a reason for the gas price crisis. But it creates a double whammy where 250% increases in energy prices – which is what the UK is experiencing – meet hefty levies. If consumers can’t meet these costs then the transition to lower carbon sources stalls and our fossil fuel dependency deepens.

5. Ignored Warnings And Low Storage Capacity

The UK has around 2% gas storage capacity, compared to around 25% for most EU countries.

Back in March this year, the UK Office of Gas and Electricity Markets warned of the risk of a gas price surge. The UK government, apparently distracted by the COVID pandemic, took no action.

This inertia, combined with low gas storage capacity, has compounded the nation’s vulnerability to the sharp price rise predicted by the energy regulator.

So Could This Happen In Australia?

Australia is steadily transitioning to clean energy – last year, renewables were responsible for 27.7% of total electricity generation.

But Australia remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels. As the UK experience shows, a diversity of renewable sources offers the greatest scope for energy security and affordability – and avoiding the transition only increases the risks of plunging into crisis.

Nicole Hasham, Section Editor: Energy + Environment, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s threatened species protections are being rewritten. But what’s really needed is money and legal teeth

The federal government has proposed replacing almost 200 recovery plans to improve the plight of threatened species and habitat with “conservation advice”, which has less legal clout. While critics have lamented the move, in reality it’s no great loss.

Recovery plans are the central tool available to the federal government to prevent extinctions. They outline a species population and distribution, threats such as habitat loss and climate change, and actions needed to recover population numbers.

But many are so vague they do very little to protect threatened species from habitat destruction and other threats. And governments are not obliged to implement or fund the plans, rendering most virtually useless.

Until federal environment law is strengthened and conservation management is properly funded, the prospects of our most vulnerable species will continue to worsen – and some will be lost forever.

What’s Being Proposed?

All threatened species and ecological communities have a conservation advice, and some also have a recovery plan.

Recovery plans and conservation advices both set out the research and management needed to protect and restore species and ecological communities listed as threatened under federal environment law.

Both instruments are usually developed by state or federal environment departments. Recovery plans can be long, complex documents which take several years to draw up and get approved. Conservation advices are usually shorter and less detailed, and are approved when a species is listed as threatened.

The minister is legally bound to act consistently with a recovery plan – for example when considering a development application which would damage threatened species habitat. Conservation advices are not legally enforceable.

The government has been reviewing past recovery plan decisions, and has identified almost 200 threatened species and ecological communities for which it believes a conservation advice will suffice.

They include the spectacled flying fox, the Tasmanian devil and the ghost spider-orchid, as well as the giant kelp marine forests of southeast Australia and NSW’s Cumberland plain woodland.

The government says a conservation advice is a “more streamlined, nimble and cost-effective document” than a recovery plan for identifying conservation needs and actions.

A Broken System

On the surface, it may seem the federal government wants to replace a powerful conservation instrument with a weaker one. But in reality, most recovery plans have done little to protect threatened plants and animals – for several reasons.

First, the wording of recovery plans is often vague and non-prescriptive, which gives the minister flexibility to approve projects that will harm a threatened species.

One analysis in 2015 by environment and legal groups exposed weaknesses in the wording around habitat protection. Of the 120 most endangered animals covered by recovery plans, only 10% had plans where limits to habitat loss was clearly stated.

For example, North Queensland’s proserpine rock wallaby is threatened by land clearing for residential and tourism developments. The analysis found its recovery plan contained “no direct and clear requirement to avoid or halt land clearing or other destructive activities”.

The Carnaby’s black-cockatoo, of Western Australia, has lost much of its foraging and breeding habitat to land clearing. Yet its recovery plan also failed to specify limits to habitat loss, allowing substantial clearing to continue.

Second, many recovery plans never come to fruition. In October last year, plans were reportedly outstanding for 172 species and habitats, and the federal environment department had not finalised one in almost 18 months. The recovery plan for the Leadbeater’s possum, for example, was devised five years ago but has never progressed past draft form.

Third, conservation management in Australia is grossly underfunded. This means recovery plans are often just a piece of paper, without funding or a team to implement them.

So Will Conservation Advices Work?

A good recovery plan, such as that of the eastern barred bandicoot, includes all the relevant detail of biology, threats, budgets, timelines and targets to turn a population around.

In the next few years, hundreds of recovery plans will need updating – a huge bureaucratic task. Given so many recovery plans have been ineffective, one has to question whether that’s the best use of government conservation dollars.

So will the move to conservation advices do as good a job? Historically, they have contained such scant detail they were of little use. However, this has been changing. Conservation advice for the northern hopping-mouse, and Mahony’s toadlet, for example, provide precise details of habitat and threats.

The Threatened Species Scientific Committee is reportedly working with the federal environment department to ensure all conservation plans provide an efficient, best-practice method for conveying recovery needs. This work is crucial.

There’s some evidence to suggest conservation advices can have legal sway. Conservation advice on the Leadbeater’s possum last year helped persuade a Victorian court to stop logging in some habitat. (The decision was later overturned, for unrelated reasons).

And federal Environment Minister Sussan Ley last year directed A$18 million to koalas on the basis of a conservation advice. This shows they can successfully inform government investment decisions.

Read more: Australia's threatened species plan sends in the ambulances but ignores glaring dangers

Looking Ahead

Recovery plans will remain vital for species with complex planning needs, such as those that face multiple threats. Conservation advices can suffice in some instances, but also have failings.

Far better than both instruments would be to strengthen regulatory tools, such as critical habitat protection. This can happen independently of recovery plans or conservation advices.

Even better would be for the government to adopt the recommendations of Graeme Samuels’ recent review of federal environment law – particularly his recommendation for national, legally-binding environmental standards to guide development decisions.

But most importantly, the federal government must invest far more in threatened species protection. Without money, many threatened species will continue on the path to extinction.

Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Your household power bills could be 15% cheaper, if Australia’s energy regulator was doing its job

If you’re like most Australians, the single biggest chunk of your energy bill — about 40% — goes to a network services company, which owns and operates the transmission lines or pipes delivering electricity or gas to your home.

But evidence from takeover bids for Australia’s last two publicly listed electricity network services companies suggests you are paying more than you should.

These prices are set by the Australian Energy Regulator, because network services are monopolies: you can choose your energy retailer, but not the lines or pipes through which the electricity or gas flow.

It’s the regulator’s job to determine a fair price for these services — one that doesn’t shortchange the service provider or gouge consumers.

But the Australian Energy Regulator has not been getting these pricing decisions right, according to calculations that can be made using the bids by overseas investors for AusNet Services Ltd, the biggest energy network provider in Victoria, and Spark Infrastructure Group, whose assets include South Australia’s electricity distribution network.

Being listed on the stock exchange, they must disclose financial information. This information enables analysts to calculate how much investors value them compared to the Australian Energy Regulator.

This calculation — known as Regulated Asset Base (RAB) multiple — suggests the regulator has been allowing energy network companies to charge way more than necessary.

Read more: Energy prices are high because consumers are paying for useless, profit-boosting infrastructure

Valuing AusNet

AusNet owns and operates almost all of the electricity transmission system in Victoria, and also big gas and electricity distribution networks. It is the subject of a takeover battle between Brookfield Asset Management, a Canadian infrastructure fund, and APA Group, Australia’s largest natural gas infrastructure business.

On September 20, it was revealed that Brookfield offered to acquire AusNet for A$2.50 a share. The day after APA Group offered a mix of cash and equity that it said valued Ausnet at A$2.60 per share.

These bids provide a baseline to calculate the Regulated Asset Base multiple: the the ratio of investors’ valuation to the regulator’s valuation.

How much an investor is prepared to pay for a share indicates their expectation of the future dividend (or profits) those shares will return. How much the regulator’s allows a company to charge is based on what it sees as a fair return to shareholders.

From this information the Regulated Asset Base multiple can be calculated.

A multiple of 1 would mean the investors’ valuation equals the regulator’s valuation. A number lower than 1 would mean the regulator is setting prices too low. A number greater than 1 means it is setting prices too high.

Brookfield’s offer, according to The Australian Financial Review, gives Ausnet a multiple of 1.68. This suggests the Australian Energy Regulator is allowing AusNet to charge prices 68% higher than Brookfield would be happy to accept. APA’s bid suggests a RAB multiple even higher.

Of course, it is not entirely as simple as that. Not all of AusNet’s revenue come from regulated assets. This may slightly affect the valuation of AusNet. Assuming AusNet’s unregulated businesses are as profitable as its larger regulated businesses, we estimate the RAB multiple is 1.54.

Valuing Spark Infrastructure

Spark Infrastructure owns controlling interests in two Victorian electricity distributors (Citipower and Powercor), Transgrid in NSW, and South Australia’s main distribution network, SA Power Networks.

In August, Spark’s board approved a A$5.2 billion takeover offer from US private equity giant Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and the Ontario Teachers’ superannuation fund.

This offer gives Spark a RAB multiple of 1.5. This suggests the monopolies Spark has a share in are charging prices 53% higher than needed to adequately compensate investors

Read more: You're paying too much for electricity, but here's what the states can do about it

Vanishing Transparency

The impact on customers will vary, but these calculations suggests network services charges should be about two-thirds current levels. This would make household electricity bills about 15% lower than now.

I am not suggesting the regulator should set prices consistent with a RAB multiple of 1. But prices should not favour monopoly owners as much these takeover valuations suggest they do.

The underlying issue here is not new. Official inquiries over the past decade — the Garnaut Climate Change Review update in 2011, the Senate inquiry into energy bills in 2012 and the Productivity Commission’s review of electricity network regulation in 2013 — all concluded energy regulation erred excessively in favour of investors at the expense of consumers.

The Australian Energy Regulator and the Australian Energy Markets Commission (which oversees all energy markets) have responded to these inquiries with new rules, guidelines, committees and processes.

Yet the problem remains — and if these takeovers are successful then AusNet and Spark Infrastructure will almost certainly be delisted. We will then lose vital information on RAB multiples that allows objective assessment of the regulator’s decisions.![]()

Bruce Mountain, Director, Victoria Energy Policy Centre, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Celebrating K’gari: why the renaming of Fraser Island is about so much more than a name

Rose Barrowcliffe, University of the Sunshine CoastOn the 19th of September, Butchulla dancers and community representatives came together at Kingfisher Bay Resort to celebrate the renaming of Fraser Island to the K’gari (Fraser Island) World Heritage Area.

The renaming was the result of a decades-long campaign by Butchulla Elders and community members and was endorsed by the Queensland government and adopted by the World Heritage Committee.

This event is the latest in a growing number of Indigenous name repatriations across the nation. As a Butchulla person, and a researcher of the representation of Indigenous peoples in archives and historical narratives, I can appreciate the significance of something as seemingly small as a name change.

How Common Is It To Revert To The Indigenous Place Name?

The reversion to the name K’gari has happened in stages over a number of years. In 2011, the Bligh government added K’gari as an alternative to the place name Fraser Island in the Queensland Place Names Register.

The Fraser Island portion of the Great Sandy National Park was changed to K’gari (Fraser Island) National Park in 2017. This latest change is specifically in relation to the UNESCO World Heritage area.

K’gari is among a growing number of places around Australia that have returned to their Indigenous names. One of the most famous examples is Uluru.

In Queensland, the National Parks First Nations Naming Project has been assisting in reverting national park names to Indigenous names where possible as a part of the government’s commitment to the truth-telling process. North Stradbroke Island and Moreton Island National Parks have reverted to Minjerribah and Gheebulum Coonungai, respectively.

According to then-minister for environment and the Great Barrier Reef, Leanne Enoch

This project is a positive step in our truth telling around First Nations Peoples’ significant and ancient connection to country.

Not Renaming, Reclaiming

Changing a place name will not fix racism in one fell swoop. No one is claiming it will. But name repatriation speaks to the importance of language in both culture and sovereignty.

Indigenous place names link Traditional Country to the history, culture and people that have been a part of that land long before colonisation. Overwriting Indigenous names with colonist names is an attempt to deny this deep, pre-existing connection and the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples.

The renaming of Butchulla Country was one of the first things Captain James Cook did as he first sailed the east coast of Australia.

In 1770, as Cook’s ship sailed close to Tacky Waroo, a large basalt headland on the east side of K’gari, it was met by a party of Butchulla warriors standing on the headland. In the lexicon of the day, all dark-skinned people were called “Indians”, so Cook renamed Tacky Waroo “Indian Head”.

In other cases, colonial place names were, and still are, blunt reminders of colonial violence. Places like Murdering Creek, Massacre Bay, Skull Creek and many more litter the Australian landscape and indicate violent acts that occurred in those places.

The name Fraser Island is named after a Scottish woman, Eliza Fraser, who was shipwrecked on the island in 1836. Fraser lied about being mistreated by Butchulla people after being shipwrecked. Even in those days, her account of her time on K’gari was thrown into doubt.

Fraser was known to be a sensationalist who made her story more and more salacious as time went on, in efforts to garner more money from sympathetic supporters. Her accounts of her time on K’gari were syndicated as far as the Americas, and reinforced the narrative that Indigenous peoples were “savages” and “cannibals”. These classifications led to Indigenous peoples being vilified around the globe.

Colonial History Is Not Indigenous History

Language plays an important part in reinforcing the notion that history in Australia began with the arrival of Cook and his fleet.

Colonial place names are another subtle yet persistent reinforcement of the notion that this land only has a place in history once it intersects with the narratives of colonists.

K’gari was the name chosen by the Butchulla because that is the sky spirit the island was created from. The name goes back to the very creation of the island, and yet the name that stuck was the name of a woman who spent not more than two months on the island.

Re-adoption of Indigenous place names signifies the increased recognition of history and culture that predates colonisation. More importantly, these name repatriations recognise that history and culture continue today.

The history of colonisation is not Indigenous history. Indigenous history and the history of this continent predates, pre-exists and will eventually override colonial history. Indigenous place names are evidence of that.

Read more: Indigenous treaties are meaningless without addressing the issue of sovereignty

Bringing Our Past Into A Shared Future

Repatriation of Indigenous place names is a part of the process of reintroducing Indigenous perspectives into the narratives of our modern society.

Repatriation of Indigenous place names reaffirms that First Nations have always existed, and still exist in Australia today. Moreover, they are a source of distinction that sets Australia apart from the rest of the world for the one thing no other country in the world can come close to: being home to the oldest living cultures in the world. That should be a source of pride for all Australians.

Always was, always will be K’gari.![]()

Rose Barrowcliffe, Doctoral Candidate, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Nationals signing up to net-zero should be a no-brainer. Instead, they’re holding Australia to ransom

Prime Minister Scott Morrison is reportedly developing a plan for Australia to adopt a target of net-zero emissions by 2050. Climate change was a central focus of the Quad talks in Washington which Morrison attended in recent days, and he is under significant international pressure to adopt a net-zero target ahead of climate talks in Glasgow in November.

Morrison is very late to the party on issue of net-zero – and lagging far behind public opinion. A recent Lowy poll showed 78% of Australians support the target.

But standing firmly in Morrison’s way is the Coalition’s junior partner, the Nationals. The words of key Nationals figures including Resources Minister Keith Pitt and pro-coal senator Matt Canavan suggest net-zero is the hill they will die on. And Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce, not exactly a climate warrior, has indicated he’s yet to be convinced on the merits of the target.

Ultimately though, this is just bad strategy from the Nationals. It burns valuable political capital for no good reason, and abrogates responsibility to their own constituents.

Not Much Of A Target At All

First, a net-zero emissions target is a really obvious position of compromise for the Nationals specifically, and for a reluctant Australian government more generally.

Every state and territory in Australia has already adopted this target for 2050, or bettered it. And most of our international peers have a net-zero target including the United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, Germany, France and the United States.

Getting to net-zero by 2050 also doesn’t necessarily require immediate or significant emissions cuts. As critics including Greta Thunberg and former IPCC chair Bob Watson have argued, the targets can create the impression of action without requiring immediate change.

Research shows many jurisdictions with a net-zero target do not have robust measures in place to ensure they’re met, such as interim targets and a reporting mechanism.

And the timeframe for net-zero – whether 2050 like most nations, or 2060 as per China – is way beyond the political longevity of our current government MPs. That means those now in parliament will be spared much of the political pain of implementing policies required to meet the target.

Finally, pursuing net-zero emissions (rather than just zero-emissions in sectors where that is feasible) allows fossil fuel companies to offset their climate damage, by buying carbon credits, rather than stopping their polluting activity. It also potentially allows for fairly speculative efforts to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere via geoengineering.

For these reasons and more, the net-zero goal is in often criticised as a dangerous trap for doing very little on climate change – which appears to be the goal of many in the Nationals.

Read more: Betting on speculative geoengineering may risk an escalating ‘climate debt crisis’

Adapting To Change

In opposing the net-zero target, the Nationals often point to potential damage to the nation’s mining and farming sectors, primarily a loss of jobs and economic growth. Some Nationals have called for those sectors to be carved out of any net-zero target.

On the question of agriculture, research released by the Grattan Institute this week shows it’s getting increasingly hard to argue the sector should be exempt from the target – its emissions are simply too great.

And there is much that can be done right now to cut agriculture emissions, if the government does more to encourage farmers to adopt the right technologies and practices.

On mining, the Nationals are fighting a losing battle. Soon, the world will no longer want our coal. As others have noted, we must prepare for the change and diversify the economy, rather than lamenting what’s still left in the ground. And Australia can easily replace coal-fired electricity generation with renewable energy, backed by storage.

For Whom Do The Nationals Speak?

By refusing to compromise on a net-zero target, the Nationals are burning all sorts of political capital they could potentially wield with the Liberals on a range of issues. The Nationals would have held particular sway over Liberals concerned about holding on to their inner city seats in a 2022 election.

More importantly, the position of Keith Pitt, Matt Canavan and other intransigents in the Nationals isn’t just an abandonment of future generations. Nor is it only a rejection of our responsibilities to vulnerable people in all parts of Australia and the world, or our duty of care to other living beings.

It’s also a spectacular betrayal of their own constituencies. Rural Australia will be disproportionately affected by climate change, particularly in the form of higher temperatures, changing rainfall patterns and increasing disasters like drought and bushfires. And the long-term economic costs of inaction for rural constituencies will be potentially catastrophic.

It’s for these reasons that organisations like the National Farmers Federation have specifically called for a commitment to net zero emissions.

In the 2019 election, the Nationals received just 4.5% of the vote in the lower house, with the Liberal Nationals of Queensland achieving just 8.7% (as a proportion of the national total). In both cases, it was less still in the Senate.

Yet despite speaking on behalf of a small fraction of the country, the party is holding Australian climate policy to ransom.

Maybe we can’t get the intransigents in the National Party to suddenly recognise their obligations to the planet and its inhabitants. But surely they can be convinced to represent the interests of rural voters? Time – what little we have left – will tell.

Read more: Net zero by 2050? Even if Scott Morrison gets the Nationals on board, hold the applause ![]()

Matt McDonald, Associate Professor of International Relations, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The hydropower industry is talking the talk. But fine words won’t save our last wild rivers

Technologies to harness the power of water are touted as crucial for a low-emissions future. But over many decades, the hydropower industry has caused serious damage to the environment and people’s lives.

More than 500 new hydropower dams are currently planned or under construction in the world’s protected areas. And some 260,000 kilometres of the last wild rivers – including the Amazon, Congo, Irrawaddy and Salween rivers – are threatened by proposed dams.

The global hydropower industry says the technology’s installed capacity must increase by more than 60% by 2050 if the world hopes to limit climate change. And the World Hydropower Congress, held remotely from Costa Rica this month, proposed steps to expand with minimal harm.

But stringent oversight, and a commitment from banks and governments to support only sustainable pumped hydro developments, is urgently needed. Otherwise, the expanding industry could displace millions more people, irreparably damage rivers and drive species to extinction.

Old Technology Given New Life

Hydroelectricity is an old technology which involves passing water from a reservoir through a turbine, to generate electricity. One application, known as pumped storage, can store electricity generated by solar and wind. In the era of climate change, pumped storage has given new life to hydropower technology.

Pumped hydro uses excess renewable energy to pump water from a lower reservoir to a higher one. The water is then released downhill to produce electricity when needed, then pumped back up when electricity returns to surplus.

Technologies such as wind and solar can only produce electricity when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing. Pumped hydro can make such generators more reliable by storing renewable energy when it’s produced then releasing it as needed.

Three pumped hydro storage projects operate in Australia: two in New South Wales and one in Queensland. Two are under construction, including the massive Snowy 2.0, and about a dozen are at the scoping stage.

Pumped hydro storage can be added to existing reservoirs on rivers. It can also be located off rivers, which can often lead to better social and environmental outcomes. One such project in North Queensland, Kidston, involves redeveloping an old gold mine.

Australian National University research this year identified about 616,000 potential sites around the world for pumped hydro, including more than 3,000 in Australia. Developing fewer than 1% of these could support a fully renewable global energy system.

A Poor Record

Hydropower and associated dams have a long record of environmental and social damage. Aside from flooding ecosystems, farmlands and towns, hydropower projects significantly disrupt river flows. This, among other harms, can deny water to floodplain wetlands, block fish migration and breeding and reduce nutrient flows.

Globally, populations of freshwater species – including mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish – have declined by about 84% since 1970, in large part due to dams. In Tasmania, inundation of the unique Lake Pedder ecosystem in the 1970s led to several species extinctions.

And while hydropower is widely considered a “clean” energy, it can lead to significant amounts of greenhouse gases when flooded plants and trees decompose.

Emissions from most hydropower dams are comparable to the life-cycle emissions from solar and wind generators. But at warmer tropical sites where vegetation is more dense, reservoirs could have a higher emission rate than fossil-based electricity.

As far back as 20 years ago, dams were found to have displaced 40 to 80 million in the half century prior. And dams have damaged the livelihoods of hundreds of millions people downstream over the past century.

But new hydro projects are routinely proposed at sites where they will cause substantial damage. And social and environmental problems caused by hydropower dams continue in places as diverse as Colombia and Southeast Asia’s Mekong region.

The Snowy 2.0 pumped storage project in Kosciusko National Park highlights trade-offs involved in many hydropower developments.

It promises to improve the reliability of solar and wind power, helping mitigate climate change. But it also threatens two endangered fish species, and several thousand hectares of national park are being cleared for infrastructure.

Read more: NSW has approved Snowy 2.0. Here are six reasons why that's a bad move

An Industry Makeover

Clearly, the world hydropower industry has public relations work to do, if its global expansion is to be realised. The International Hydropower Association appears to have cottoned on to this, taking a sophisticated approach to improving the industry’s social licence.

The industry has actively engaged conservationists in preparing sustainability standards. Voluntary assessment tools outline steps to minimise damage to people and the environment, and a new sustainability certification scheme for hydropower was launched at this month’s congress.

The industry has pledged not to build hydropower dams in world heritage sites. It has also offered to “avoid, minimise, mitigate or compensate” for damage in protected areas (albeit falling short on offering full protection).

However, it’s hard to see the new standards being systematically applied unless governments of major dam building nations – especially China, India, Brazil and Turkey – adopt the standards in their planning and approval processes.

And how will rogue operators and irresponsible financiers be prevented from developing unsustainable projects – especially when some governments are fixated on enabling them?

It’s in the interests of the International Hydropower Association, as the progressive element of the hydropower industry, to advocate for governments and financiers to assess proposed hydropower projects against the new standards.

Read more: When dams cause more problems than they solve, removing them can pay off for people and nature

Causing The Least Harm

Pumped hydro has an important role to play in the renewable energy transition, but only where projects cause minimal harm to people and nature.

Ensuring a sustainable industry in future could be achieved by stopping damaging conventional hydropower projects on rivers. Instead, pumped storage projects should be developed when:

an assessment shows they meets the needs of an energy system

environmental and social conflicts are minimal, such as at off-river sites

for projects in tropical areas, shallow reservoirs and flooding of vegetation is avoided to minimise greenhouse gas emissions.

Pumped storage offers the hydropower industry a chance to reposition itself from villain to hero. The industry must now translate its words into practice. And financiers and government regulators must support only those hydropower projects which genuinely seek to minimise environmental and social harm.![]()

Jamie Pittock, Professor, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change is testing the resilience of native plants to fire, from ash forests to gymea lilies

Green shoots emerging from black tree trunks is an iconic image in the days following bushfires, thanks to the remarkable ability of many native plants to survive even the most intense flames.

But in recent years, the length, frequency and intensity of Australian bushfire seasons have increased, and will worsen further under climate change. Droughts and heatwaves are also projected to increase, and climate change may also affect the incidence of pest insect outbreaks, although this is difficult to predict.

How will our ecosystems cope with this combination of threats? In our recently published paper, we looked to answer this exact question — and the news isn’t good.

We found while many plants are really good at withstanding certain types of fire, the combination of drought, heatwaves and pest insects may push many fire-adapted plants to the brink in the future. The devastating Black Summer fires gave us a taste of this future.

What Happens When Fires Become More Frequent?

Ash forests are one of the most iconic in Australia, home to some of the tallest flowering plants on Earth. When severe fire occurs in these forests, the mature trees are killed and the forest regenerates entirely from the seed that falls from the dead canopy.

These regrowing trees, however, do not produce seed reliably until they’re 15 years old. This means if fire occurs again during this period, the trees will not regenerate, and the ash forest will collapse.

This would have serious consequences for the carbon stored in these trees, and the habitat these forests provide for animals.

Southeast Australia has experienced multiple fires since 2003, which means there’s a large area of regrowing ash forests across the landscape, especially in Victoria.

The Black Summer bushfires burned parts of these young forests, and nearly 10,000 football fields of ash forest was at risk of collapse. Thankfully, approximately half of this area was recovered through an artificial seeding program.

What Happens When Fire Seasons Get Longer?

Longer fire seasons means there’s a greater chance species will burn at a time of year that’s outside the historical norm. This can have devastating consequences for plant populations.

For example, out-of-season fires, such as in winter, can delay maturation of the Woronora beard-heath compared to summer fires, because of their seasonal requirements for releasing and germinating seeds. This means the species needs longer fire-free intervals when fires occur out of season.

Read more: Entire hillsides of trees turned brown this summer. Is it the start of ecosystem collapse?

The iconic gymea lily, a post-fire flowering species, is another plant under similar threat. New research showed when fires occur outside summer, the gymea lily didn’t flower as much and changed its seed chemistry.

While this resprouting species might persist in the short term, consistent out-of-season fires could have long-term impacts by reducing its reproduction and, therefore, population size.

When Drought And Heatwaves Get More Severe

In the lead up to the Black Summer fires, eastern Australia experienced the hottest and driest year on record. The drought and associated heatwaves triggered widespread canopy die-off.

Extremes of drought and heat can directly kill plants. And this increase in dead vegetation may increase the intensity of fires.

Another problem is that by coping with drought and heat stress, plants may deplete their stored energy reserves, which are vital for resprouting new leaves following fire. Depletion of energy reserves may result in a phenomenon called “resprouting exhaustion syndrome”, where fire-adapted plants no longer have the reserves to regenerate new leaves after fire.

Therefore, fire can deliver the final blow to resprouting plants already suffering from drought and heat stress.

Drought and heatwaves could also be a big problem for seeds. Many species rely on fire-triggered seed germination to survive following fire, such as many species of wattles, banksias and some eucalypts.

But drought and heat stress may reduce the number of seeds that get released, because they limit flowering and seed development in the lead up to bushfires, or trigger plants to release seeds prematurely.

For example, in Australian fire-prone ecosystems, temperatures between 40℃ and 100℃ are required to break the dormancy of seeds stored in soil and trigger germination. But during heatwaves, soil temperatures can be high enough to break these temperature thresholds. This means seeds could be released before the fire, and they won’t be available to germinate after the fire hits.

Heatwaves can also reduce the quality of seeds by deforming their DNA. This could reduce the success of seed germination after fire.

What about insects? The growth of new foliage following fire or drought is tasty to insects. If pest insect outbreaks occur after fire, they may remove all the leaves of recovering plants. This additional stress may push plants over their limit, resulting in their death.

This phenomenon has more typically been observed in eucalypts following drought, where repeated defoliation (leaf loss) by pest insects triggered dieback in recovering trees.

When Threats Pile Up

We expect many vegetation communities will remain resilient in the short-term, including most eucalpyt species.

But even in these resilient forests, we expect to see some changes in the types of species present in certain areas and changes to the structure of vegetation (such as the size of trees).

As climate change progresses, many fire-prone ecosystems will be pushed beyond their historical limits. Our new research is only the beginning — how plants will respond is still highly uncertain, and more research is needed to untangle the interacting effects of fire, drought, heatwaves and pest insects.

We need to rapidly reduce carbon emissions before testing the limits of our ecosystems to recover from fire.

Read more: 5 remarkable stories of flora and fauna in the aftermath of Australia’s horror bushfire season ![]()

Rachael Helene Nolan, Postdoctoral research fellow, Western Sydney University; Andrea Leigh, Associate Professor, Faculty of Science, University of Technology Sydney; Mark Ooi, Senior Research Fellow, UNSW; Ross Bradstock, Emeritus professor, University of Wollongong; Tim Curran, Associate Professor of Ecology, Lincoln University, New Zealand; Tom Fairman, Future Fire Risk Analyst, The University of Melbourne, and Víctor Resco de Dios, Profesor de Incendios y Cambio Global en PVCF-Agrotecnio, Universitat de Lleida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The sun’s shining and snakes are emerging, but they’re not out to get you. Here’s what they’re really up to

It’s early spring in southern Australia and the sun is, gloriously, out. You decide to head to your local patch of greenery – by the creek, lake, or foreshore – with the sun on your face, the breeze in your hair, and your dog’s tongue blissfully lolling.

Suddenly you see it. Paused on the path just a few meters in front of your feet, soaking up those same springtime rays — a snake.

Love them or loathe them, snakes have been co-existing with, and haunting us, since well before our ancestors called themselves “human”. From the subtle tempter of Genesis to the feathered serpent deities of Mesoamerica, snakes have always been potent symbols of otherness.

Today, to encounter a snake is to brush up against the wild and mysterious heart of the natural world. Snakes are important members of every terrestrial ecosystem across Australia. Even in the most populous parts of the country, snakes inhabit the remnant bushland dispersed throughout our major cities.

But what exactly influences human–snake interactions? Whether you’re hoping to maximise your chances of seeing one of these shy, fascinating critters or wanting to avoid them at all costs, this article is for you.

Snakes In Southern Springtime

In southern Australia, a flurry of animal activity occurs in spring. As resources start becoming plentiful after the relatively lean months of winter, spring is the reproductive season for many plants and animals.

One such resource is heat — a particularly crucial resource for organisms such as reptiles, which don’t make their own body heat (unlike mammals). It’s a common misconception, however, that snakes want as much heat as they can get. Like Goldilocks, snakes want the temperature to be just right.

Southern springs are the right temperature for snakes to bask during the times of day we humans are also out and about. In summer, snakes, including venomous species such as tiger snakes and brown snakes, are typically more active very early in the morning, late in the evening, or during the night when temperatures are not too high for them.

After a slow winter, snakes are both hungry (they may have been fasting for months!) and on the lookout for eligible members of the opposite sex. Basking, hunting, and searching for a mate brings snakes out into the open in spring a bit more than at other times of year, so we’re most likely to encounter them during this time.

Snake Activity In Northern Australia

Like all things, snake activity is a little different in the north. Spare a thought for those poor northern Australians who will never know the joys of a snake-filled springtime.

Still, the north has far more snake species than the south, including many species of non-venomous python — the farther south you go, the more our snake fauna is dominated by venomous species (check out Australian Reptile Online Database for distribution maps).

Because of the unforgiving year-round heat across northern Australia, temperature doesn’t drive snake activity as it does in the south. You will rarely see a basking snake in Australia’s Top End, they’re too busy avoiding the heat.

Instead, snake activity is driven by another important resource – rain. In the Top End, this means snakes are most often encountered following the wet season (April–June) when prey and water abound.

In other, more arid “boom and bust” systems, large rainfall events may only happen every five to ten years. When they do, they can trigger huge flurries of snake activity as the serpents emerge to take advantage of fleetingly available prey.

Snakes Indicate Ecosystem Health

From the moment of birth, all species of snake are predatory, although some, like shovel-nosed snakes, prey only upon eggs.

In some terrestrial Australian ecosystems, snakes are near the top of the food chain. After reaching a certain size, they have few predators of their own. A two-metre coastal taipan in the cane fields of northern Queensland, for example, has more to fear from harvesters than it does from any natural predator.

For large snakes to persist in an environment, they need an abundance of their prey (mice, frogs and lizards), as well as all the species their prey feed upon (invertebrates, even smaller animals, or plants).

Snakes often also have specific habitat requirements. In general, they need shelter and protection from bigger predators, which might include birds of prey, predatory mammals such as native marsupials or introduced cats and foxes, or other snakes. They also need opportunities for safely regulating their body temperature.

This means a snake will only call a place home if it has both a functioning food-web and the necessary habitat complexity. So remember, if you see snakes in your backyard or local park, it’s a sign the ecosystem is doing pretty well.

Snakes Don’t Want To Bite You

Snakes are awesome predators, but no Australian snake is interested in eating a human. In fact, they want as little to do with us giant hairless apes as possible.

Why? Because snakes are actually quite vulnerable animals. Compared to many other species, they are small, have no sharp claws or strong limbs, and limited energy to put up a fight — they are basically limbless lizards with different teeth.

For those that possess it, venom is a last resort and only a minority of species —such as taipans, brown snakes, tiger snakes, and death adders — can deliver a life-threatening bite to a person. But snakes would much rather use their venom to subdue prey (that’s what they have it for) than to defend themselves.

When snakes bite humans in Australia, it’s a defensive reaction to a large animal they view as a potential predator. Remember, they can’t understand your intentions, even if those intentions are good.

If you’re lucky enough to see a wild snake, and if you respect its boundaries and give it personal space, it’s sure to do the same for you. Keep dogs on the lead in snakey areas and educate your kids to be snake-smart from as young as possible.

Even though snakes don’t want to bite, snakebite envenoming can be a life-threatening emergency. Learn first aid, and when you go for a walk in one of those sanctuaries of greenery that snakes like as much as we do, carry a compression bandage (or three).

It’s almost certain you will never need it, but it could just save a life.

Read more: Does Australia really have the deadliest snakes? We debunk 6 common myths ![]()

Timothy N. W. Jackson, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Australian Venom Research Unit, The University of Melbourne; Chris J Jolly, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Charles Sturt University, and Damian Lettoof, PhD Candidate, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The clock is ticking on net-zero, and Australia’s farmers must not get a free pass

Political momentum is growing in Australia to cut greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050. On Friday, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was the latest member of the federal government to throw his weight behind the goal, and over the weekend, Prime Minister Scott Morrison acknowledged “the world is transitioning to a new energy economy”.

But for Australia to achieve net-zero across the economy, emissions from agriculture must fall dramatically. Agriculture contributed about 15% to Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 – most of it from cattle and sheep. If herd numbers recover from the recent drought, the sector’s emissions are projected to rise.

Cutting agriculture emissions will not be easy. The difficulties have reportedly triggered concern in the Nationals’ about the cost of the transition for farmers, including calls for agriculture to be carved out of any net-zero target.

But as our new Grattan Institute report today makes clear, agriculture must not be granted this exemption. Instead, the federal government should do more to encourage farmers to adopt low-emissions technologies and practices – some of which can be deployed now.

Read more: Nationals' push to carve farming from a net-zero target is misguided and dangerous

Three Good Reasons Farmers Must Go Net-Zero

Many farmers want to be part of the climate solution – and must be – for three main reasons.

First, the agriculture sector is uniquely vulnerable to a changing climate. Already, changes in rainfall have cut profits across the sector by 23% compared to what could have been achieved in pre-2000 conditions. The effect is even worse for cropping farmers.

Livestock farmers face risks, too. If global warming reaches 3℃, livestock in northern Australia are expected to suffer heat stress almost daily.

Second, parts of the sector are highly exposed to international markets – for example, about three-quarters of Australia’s red meat is exported.

There are fears Australian producers may face a border tax in some markets if they don’t cut emissions. The European Union, for instance, plans to introduce tariffs as early as 2023 on some products from countries without effective carbon pricing, though agriculture will not be included initially.

Third, the industry recognises action on climate change can often boost farm productivity, or help farmers secure resilient revenue streams. For example, trees provide shade for animals, while good soil management can preserve the land’s fertility. Both activities can store carbon and may generate carbon credits.

Carbon credits can be used to offset farm emissions, or sold to other emitters. In a net-zero future, farmers can maximise their carbon credit revenue by minimising their own emissions, leaving them more carbon credits to sell.

The agriculture sector itself is increasingly embracing the net-zero goal. The National Farmers Federation supports an economy-wide aspiration to be net-zero by 2050, with some conditions. The red meat and pork industries have gone further, committing to be carbon neutral by 2030 and 2025 respectively.

What Can Be Done?

Australian agricultural activities emitted about 76 million tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions in 2019. Of this, about 48 million tonnes were methane belched by cattle and sheep, and a further 11 million came from their excrement.

The sector’s non-animal emissions largely came from burning diesel, the use of fertiliser, and the breakdown of leftover plant material from cropping.

Unlike in, say, the electricity sector, it’s not possible to completely eliminate agricultural emissions, and deep emissions cuts look difficult in the near term. That’s because methane produced in the stomachs of cattle and sheep represents more than 60% of agricultural emissions; these cannot be captured, or eliminated through renewable energy technology.

Supplements added to stock feed - which reduce the amount of methane the animal produces - are the most promising options to reduce agricultural emissions. These supplements include red algae and the chemical 3-nitrooxypropanol, both of which may cut methane by up to 90% if used consistently at the right dose.

But it’s difficult to distribute these feed supplements to Australian grazing cattle and sheep every day. At any given time, only about 4% of Australia’s cattle are in feedlots where their diet can be easily controlled.

Diesel use can be reduced by electrifying farm machinery, but electric models are not yet widely available or affordable for all purposes.

These challenges slow the realistic rate at which the sector can cut emissions. Yet there are things that can be done today.

Many manure emissions can be avoided through smarter management. For example, on intensive livestock farms, manure is often stored in ponds where it releases methane. This methane can be captured and burnt, emitting the weaker greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, instead.

And better targeted fertiliser use is a clear win-win – it would save farmers money and reduce emissions of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas.

Governments Must Walk And Chew Gum

An economy-wide carbon price would be the best way for Australia to reduce emissions in an economically efficient manner. But the political reality is that carbon pricing is out of reach, at least for now. So Australia should pursue sector-specific policies – including in agriculture.

Governments must walk and chew gum. That means introducing policies to support emissions-reducing actions that farmers can take today, while investing alongside the industry in potential high-impact solutions for the longer term.

Accelerating near-term action will require improving the federal government’s Emissions Reduction Fund, to help more farmers generate Australian carbon credit units. It will also require more investment in outreach programs to give farmers the knowledge they need to reduce emissions.

Improving the long-term emissions outlook for the agriculture sector requires investment in high-impact research, development and deployment. Bringing down the cost of new technologies is possible with deployment at scale: all governments should consider what combination of subsidies, penalties and regulations will best drive this.

Agriculture must not become the missing piece in Australia’s net-zero puzzle. Without action today, the sector may become Australia’s largest source of emissions in coming decades. This would require hugely expensive carbon offsetting - paid for by taxpayers, consumers and farmers themselves.

James Ha, Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

When fire hits, do koalas flee or stick to their tree? Answering these and other questions is vital

Pablo Negret, The University of Queensland and Daniel Lunney, University of SydneyFigures released this week suggest Australia’s koala populations have plummeted by 30% in three years, and fewer than 58,000 now remain in the wild.

The statement from the Australian Koala Foundation has not been verified on the ground, giving it a high degree of uncertainty. But the claim aligns with a number of studies showing some koala populations are rapidly declining, particularly in Queensland and New South Whales.

Fire is an increasing threat to koalas; the 2019-20 megafires are estimated to have affected more than 60,000 koalas and reduced population numbers at multiple sites, including several areas of New South Wales. As bushfire risk increases under climate change, eucalyptus forest where koalas live are expected to suffer further impacts in the next 50-100 years.

So what’s the best way to protect these iconic animals from fires? Our new report for the National Environmental Science Program (NESP) sought to answer this question. We identified actions to reduce the risk of koalas being harmed by fires, and found gaps in scientific knowledge where more research is urgently needed.

A Few Big Unknowns

Our research found scientific understanding of the interaction between fire management and koala conservation is lacking in three areas.

First, more research is needed on koala movements and their activity patterns before, during and after fires. For example, do koalas move during fire or stay in the same trees?

Evidence shows koalas rapidly move to and use recently burnt habitat. But it’s not known whether koalas found in recently burnt areas are new to that part of the forest or inhabited it before the fire.

After bushfires and prescribed burns, koalas can be injured by smouldering bark or burning embers when moving between trees. They can also become dehydrated. But how this affects koala movement and survival is barely understood.

Second, we need better understanding of how prescribed burning affects koala populations, in both the short and long term. Prescribed burning may benefit koalas if it reduces the severity of bushfires, but it can also kill or injure individual koalas. Better understanding the positives and negatives is crucial.

This might be achieved through long-term GPS radio-tracking of individual koalas, or compiling information about injured or dead koalas after prescribed burns and reporting it to conservation authorities.

Third, we need to know more about links between habitat connectivity, bushfire characteristics and koala population dynamics.

For example, fire can cause koala habitat to fragment. This makes habitat drier, which in turn may increase fire frequency and severity. But increased fragmentation can also limit the spread of fire and make it easier to control, which ultimately benefits koalas. More research into these trade-offs is required.

Read more: Stopping koala extinction is agonisingly simple. But here's why I'm not optimistic

Fires And Koalas: A Roadmap

Koalas can be protected from fires in various ways, including managing fire risk or, when fires do occur, managing koala populations and habitat to increase the chance of recovery.

But to date, there’s been little guidance about how effective various management actions are, and how best to allocate resources.

Our framework, one of the first of its kind, sought to address these questions. It can be used by land managers, scientists, koala rehabilitation groups, the media and the general public.

The work involved reviewing existing literature on fire ecology and management, as well as koala ecology and conservation. We also gathered expert advice through individual discussions and workshops in Queensland and New South Wales.

We identified several goals that, if achieved, will help maintain koala populations in fire prone landscapes. They include:

improving or maintaining koala habitat and koala populations before and after fires. This might involve replanting, weed management, reforestation and pest control, long-term monitoring of koala populations and their habitat or minimising other threats, such as vehicle collisions, dog attacks, habitat loss and climate change

maintaining or restoring fire patterns suited to an ecosystem – for example, by conducting prescribed burning to make an area less flammable in the case of altered fire frequency, or so-called “mosaic” burning to create patches of burnt and unburnt areas

actions during bushfires, such as creating a low-intensity backburn that travels down a slope away from koala areas

exchanging knowledge between koala conservation organisations and Traditional Owners, Indigenous communities of the area and the various fire management authorities

effective post-fire management, such as quickly rescuing injured koalas for rehabilitation, and restoring key koala habitat.

Read more: Scientists find burnt, starving koalas weeks after the bushfires

Looking Ahead

Our proposed strategies and actions should also take into account other priorities, such as human safety, property protection and cultural values of Indigenous people and others.

Our framework requires further development. But it’s a first step in bringing together information previously scattered across different sources and branches of knowledge.