inbox and environment news: Issue 513

October 10 - 16, 2021: Issue 513

Life In The Treetops: Latest Episode Of The Coast

Palm Beach Shop Top Development Proposal Withdrawn

Australasian Figbirds: Spring 2021 Visitors

Birds In Your Garden: Wish You Had More?

Aussie Backyard Bird Count 2021

The 2021 event will run from October 18‒24 during National Bird Week. Register as a counter today at: https://aussiebirdcount.org.au/

The Aussie Backyard Bird Count is one of Australia’s biggest citizen science events. This year is our eighth count, and we’re hoping it will be our biggest yet!

Join thousands of people around the country in exploring your backyard, local park or favourite outdoor space and help us learn more about the birds that live where people live.

Taking part in the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is a great way to connect with the birds in your backyard, no matter where your backyard happens to be. You can count in a suburban garden, a local park, a patch of forest, down by the beach, or the main street of town.

To take part, register on the website today, then during the count you can use the web form or the app to submit your counts. Just enter your location and get counting ‒ each count takes just 20 minutes!

Not only will you be contributing to BirdLife Australia's knowledge of Aussie birds, but there are also some incredible prizes on offer.

Head over to the Aussie Backyard Bird Count website to find out more.

Avalon Preservation Association 2021 AGM

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

As far as the moon and back, twice: here’s a look at the most extraordinary journeys migrating birds make

Every year, millions of birds criss-cross the planet, soaring above our heads in search of food, warmth and mates. From pole to pole, here are some of the most remarkable journeys made by our feathered friends.

So-called “summer migrants”, like the common cuckoo, are bird species which spend roughly October to March in warmer climes than that of the UK, such as those of Portugal, Senegal and the Congo Basin.

In the UK’s summer months, there is such an abundance of airborne insects – their diet of choice – that these birds are not only able to feed themselves but can successfully raise a family too. But in the autumn, when it’s too cold for many insects to fly, the birds return south where the weather is warmer and there are flies available all year round.

Believe it or not, some birds come to Europe in winter for its milder weather. Species such as barnacle geese breed in the Arctic, where there are full days of sunlight and plenty of grass on which to feed during the spring and summer. When the cold weather sets in, they migrate south to take advantage of the warmer winters.

Long Distance

The Arctic tern, which holds the record for the longest migration of any bird, breeds in the very north of Europe and Asia during summer before migrating all the way to the Antarctic Ocean to spend another summer: this time in the southern hemisphere.

This journey across the entire globe covers a distance of about 35,000km. The oldest known Arctic tern survived for 31 years, which means it travelled over 1.6m kilometres in its lifetime – more than the equivalent of travelling to the moon and back twice.

Lots of species follow a section of the Arctic terns’ route by going from north to south and back: but the red-necked phalarope offers a twist on this classic journey. This bird, which weighs 27-48g – the same as between one and two small bags of crisps – flies west from Scotland to Peru and back each year.

A study has shown that one red-necked phalarope, which bred on the Shetland Isles, flew west to cross the Atlantic Ocean before stopping over at the border between the US and Canada. The bird then flew down the east coast of the US and crossed over onto the Pacific coast of Mexico. From there, it continued south until it reached the coast of Peru, where it spent October to April. This marathon flight is typical behaviour for individuals breeding in Scotland, Iceland or Greenland.

Top Speed

Although the peregrine falcon is known to be able to reach the fastest speed of any animal, reaching up to 322kmph during one of its steep dives or “stoops”, its average speed in level flight is between 65-95kmph: enough to comfortably keep up with a standard car. Now, imagine a bird able to keep that speed up for 6,760km.

That’s the feat achieved by tens of thousands of great snipes each year. This brown wading bird looks unassuming as it feeds at the edges of lakes and in soft mud, but when it’s time to migrate it can fly non-stop for almost seven thousand kilometres at an average speed of 97kmph. This extraordinary journey takes individuals from Sweden, where they breed, to sub-Saharan Africa, where they spend winter.

High Fliers

One of the more fascinating aspects of bird migration is the extreme heights at which birds often choose to travel. Cooler air is thinner, requiring less effort to fly through. The coolness also prevents birds from overheating whilst using their wing muscles so much. But the downside to this is the much lower oxygen levels in upper regions of the Earth’s atmosphere, resulting in increased risk of hypoxia: where the levels of oxygen reaching the body’s tissues are insufficient, potentially causing damage.

Birds counteract this by producing more red blood cells, which help carry more oxygen through their body. This is the same process that occurs in human athletes training at high altitudes. Astonishingly, there have been reports of bar-headed geese flying above the highest Himalayan peaks – which can reach over 8km. This species’ unique physiology, including larger lungs and brains able to tolerate low carbon dioxide levels in the blood, has long fascinated researchers.

Smaller birds, such as pied flycatchers, also use cooler air to travel, often flying at night so that they don’t have to fly as high to reach sufficiently cool areas. Because of this, they’re called nocturnal migrants. These birds navigate using the stars, only landing to refuel during the day. We know that they travel by night by recording their in-flight calls as they pass overhead during the hours of darkness.![]()

Jeremy Smith, Lecturer in Natural History, University of South Wales

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Ley Approves Another Two New Coal Mines

Koala Spotters Wanted

Greater Sydney Water Strategy Open For Feedback

- Improving water recycling, leakage management and water efficiency programs, which could result in water savings of up to 49 gigalitres a year by 2040.

- Extending a water savings program, which has been piloted in over 1000 households and delivered around 20 per cent reduction in water use per household and almost $190 in savings per year for household water bills.

- Consideration of running the Sydney Desalination Plant full-time to add an extra 20 gigalitres of water per year.

- Expanding or building new desalination plants to be less dependent on rainfall.

- Investigating innovations in recycled water to improve sustainability.

- Making greater use of stormwater and recycled water to cool and green the city and support recreational activities.

Warragamba Dam Raising Project EIS On Public Exhibition

$2 Million In Litter Prevention Grants Available To Help Keep NSW Litter Free

- Council Litter Prevention Grants Program

- Litter Regional Implementation Program (for Regional Waste Groups)

- Community Litter Prevention Grants Program

- Cigarette Butt Litter Prevention Grants Program (including for businesses and government organisations).

New Rules Put Carp In The Crosshairs Of Bowfishers

Climate-Based Legal Challenge To NSW Water-Sharing Plan

Reef 2050 Plan Must Be Strengthened Before It Is Released

- Take the lead on a climate policy that is compatible with ensuring the future of our most beloved natural icon;

- Invest more to accelerate action on water quality

Christmas And Cocos (Keeling) Islands Marine Park Plans A Major Step Forward For Global Conservation

NSW Government Plan To Revitalise Peat Island And Mooney Mooney Released

- Nearly 270 new homes at Mooney Mooney to deliver more housing supply,

- Retention of nine unlisted historical buildings on the island, and four on the mainland, to be restored and used for new community and commercial opportunities,

- New retail and café or restaurant opportunities,

- Approximately 9.65 hectares of open space, including opportunities for walking and cycling tracks, parklands and recreational facilities,

- Retention of the chapel and surrounding land for community use, and

- 10.4 hectares of bushland dedicated as a conservation area.

Community Voices Vital In Aerotropolis Exhibition

The final planning package to unlock the potential of the Western Sydney Aerotropolis is a step closer to completion, with proposed changes to the State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP) now on public exhibition.

The final planning package to unlock the potential of the Western Sydney Aerotropolis is a step closer to completion, with proposed changes to the State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP) now on public exhibition.Crown Land For Northern Rivers Wildlife Hospital

Plans for a wildlife hospital for the Northern Rivers are a step closer with approval for Crown land to be used for the project.

Plans for a wildlife hospital for the Northern Rivers are a step closer with approval for Crown land to be used for the project.Feral horses will rule one third of the fragile Kosciuszko National Park under a proposed NSW government plan

The New South Wales government has released a draft plan to deal with feral horses roaming the fragile Kosciuszko National Park. While the plan offers some improvements, it remains seriously inadequate.

Feral horses trample endangered plant communities, destroy threatened species’ habitat and damage Aboriginal cultural heritage — all the while increasing in numbers. The draft plan would keep many horses in the national park, locking in ongoing environmental and cultural degradation.

The number of horses has grown dramatically in recent years under the Wild Horse Heritage Protection Act, which became law in 2018 and was championed by then NSW Deputy Premier John Barilaro. He and others argued the horses were important to Australia’s history of pioneering, pastoralism and horse trapping, and were related to rural legends and literary works.

But the cultural heritage of an introduced species should not override the needs of a highly vulnerable alpine environment. Barilaro quit politics this week – and with the driving political force behind feral horse protection now gone, we have an 11th-hour chance to safeguard this significant national park.

What’s In The Draft Plan?

On the positive side, the draft plan aims to:

remove feral horses from 21% of the park

reduce feral horse numbers to 3,000 by 2027

prevent feral horses from invading new areas.

These are critical measures. As the draft plan notes, achieving them will need a set of carefully considered control methods, including ground shooting and putting down trapped horses.

Contrary to recent counter-productive management, reproductive-age females will no longer be released back into the park after being trapped.

But on the flip side, the plan will also:

allocate one third (32%) of the national park to feral horses

maintain 3,000 horses within the protected area in perpetuity

attempt to control horse numbers without using the most humane and cost-effective method: aerial shooting.

Aerial shooting is ruled out because of fears around losing social licence to remove horses from the park. But this may make it impossible to achieve effective horse control across rocky, difficult-to-access terrain.

It also means feral horse control will drag out over years. This will result in larger numbers of horses being culled, compared with completing a cull within one year. Maintaining 3,000 feral horses in this reserve means accepting the removal of at least 1,000 animals every two years in perpetuity, based on a conservative rate of population growth.

Over 14,000 Horses, And Rising

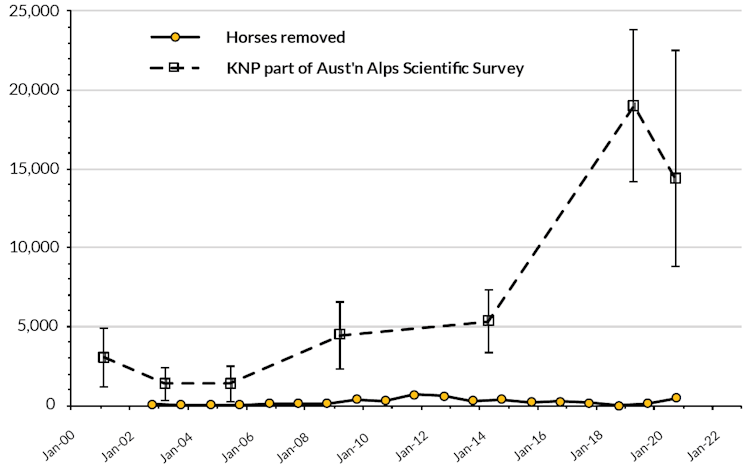

To understand the challenge, it’s important to understand the numbers. The chart below – using population data collected by ecologist Don Fletcher for a Reclaim Kosciuszko report – compares the number of feral horses in Kosciuszko National Park since 2000, with the number removed by trapping.

The number of horses in Kosciuszko was last measured in November 2020 at just over 14,000.

With an the ongoing rate of increase of 18% per year and two years of population growth, numbers will have increased by 5,500. This means there’ll likely be almost 20,000 feral horses before control can start in 2022, under this plan.

Compare this with the 3,350 horses trapping has removed between 2008 and 2020, and it’s clear culling, including via aerial shooting, is urgently needed.

The huge, growing number of horses roaming Kosciuszko combined with the likelihood of immigration from outside the park, is also the main reason fertility control cannot work. The draft report is therefore right to reject fertility control as a workable solution.

33 Threatened Species In Greater Peril

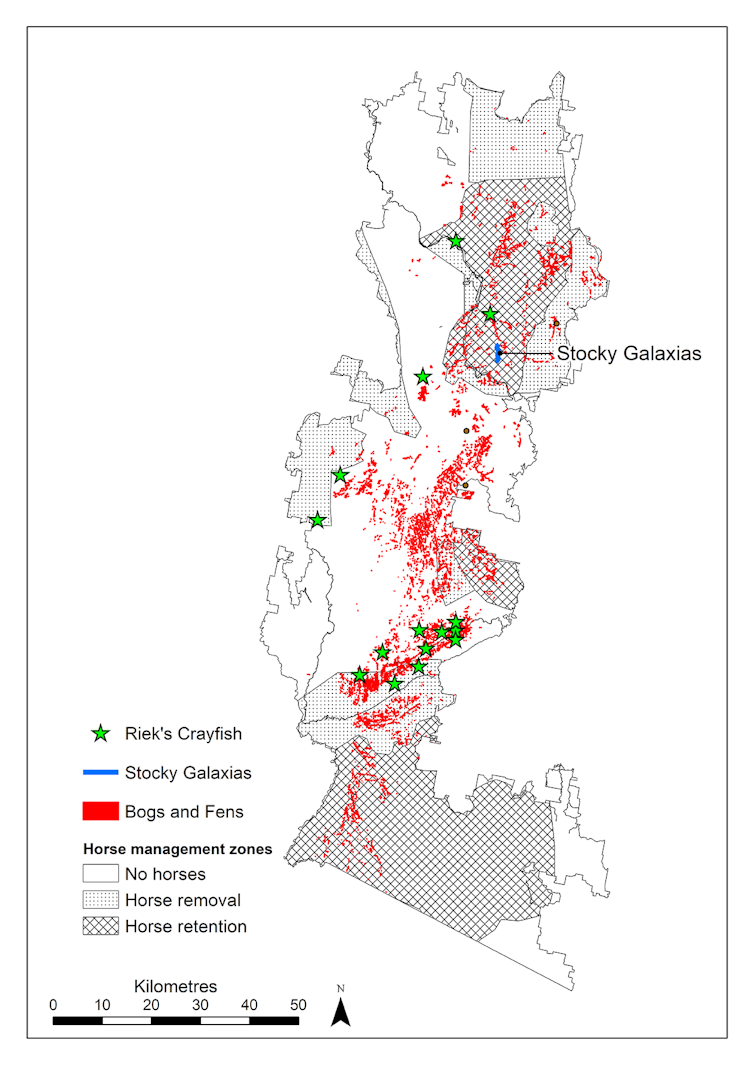

We are most concerned about the draft plan’s allocation of one third of the park to at least 3,000 feral horses, and likely many more given the limitations on control methods. These areas harbour important ecosystems and threatened species.

Using publicly accessible data from NSW Bionet and Atlas of Living Australia, we estimate at least 33 threatened species live within the horse retention zone. About half of these are either already known to be impacted by feral horses or we suggest will likely be impacted because they’re vulnerable to trampling, grazing or habitat damage.

For example, the only place the critically endangered stocky galaxias – Australia’s most alpine-adapted fish – occurs is within the horse-retention area.

This hardy fish was recently rescued from bushfires and faces grave risks associated with the Snowy 2.0 scheme. It’s currently protected from feral horses thanks to a stock-exclusion fence, and the draft plan notes fencing is only a short-term solution.

Read more: Double trouble: this plucky little fish survived Black Summer, but there's worse to come

The endangered Riek’s crayfish also has a restricted range within Kosciuszko. If horses are removed in the southern part of the park, as the draft plan outlines, then damage to their habitat will decline by 2027. But horses remain a threat to their habitats in the north.

Alpine sphagnum bogs and associated fens are a nationally threatened plant community with a stronghold in Kosciuszko. It is particularly vulnerable to impacts from feral horses, and we calculate 28% of its distribution in Kosciuszko will be inside the horse-retention zone.

Horses Heritage Value A Non-Sequitur

The draft plan’s main reason for keeping feral horses in the national park is to protect heritage values. However, the plan does not explain why heritage must be celebrated by keeping 3,000 feral horses in a national park.

In our view, while the horses have cultural heritage value to some, letting them continue to damage a fragile national park is an unacceptable trade-off.

Read more: The ethical and cultural case for culling Australia's mountain horses

Consider the recent Aboriginal cultural values report. It noted Indigenous Australians share similar heritage associations as skilled horse riders on farms since early colonial times. However, the report recommends acknowledging this heritage with information in a visitor centre.

Preservation of huts and interpretive signs are another way of acknowledging the heritage values of pastoralists past.

A Social License

Research released this month surveyed 2,430 Australians and found 71% accept that feral animals can be culled to protect threatened species. As the researchers write, this sentiment is not fully reflected in existing policy and legislation.

Barilaro’s exit may be an opportunity for NSW politicians to capitalise on this social licence.

This draft plan is one step towards protecting our native species, natural places and Indigenous heritage, and will be open for submissions until November 2.

But if aerial culling was also on the table, those goals could be achieved with fewer horses culled and at lower cost.

Don Driscoll, Professor in Terrestrial Ecology, Deakin University; David M Watson, Professor in Ecology, Charles Sturt University; Desley Whisson, Senior Lecturer in Wildlife and Conservation Biology, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University, and Maggie J. Watson, Lecturer in Ornithology, Ecology, Conservation and Parasitology, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia could ‘green’ its degraded landscapes for just 6% of what we spend on defence

The health of many Australian ecosystems is in steep decline. Replanting vast tracts of land with native vegetation will prevent species extinctions and help abate climate change – but which landscapes should be restored, and how much would it cost?

Our latest research sought answers to these questions. We devised a feasible plan to restore 30% of native vegetation cover across almost all degraded ecosystems on Australia’s marginal farming land.

By spending A$2 billion – about 0.1% of Australia’s gross domestic product – each year for about 30 years, we could restore 13 million hectares of degraded land without affecting food production or urban areas.

Such cost-effective solutions must be implemented now if we’re to pull our landscapes back from the brink. This bold vision would transform the way we manage our landscapes, help Australia become a net-zero nation and create jobs in regional communities.

An Ambitious Agenda

Since European settlement, large areas of Australia’s native vegetation have been progressively cleared for agriculture and urban settlements. Australia’s environment remains under mounting pressure from land clearing, altered fire regimes and invasive species.

Our research shows that about one-fifth of Australia’s ecosystems have less than 30% coverage of healthy native vegetation. Below 30%, ecosystem services and biodiversity sharply declines. We calculate that 13 million hectares of land must be restored to reach the 30% threshold.

Targeted restoration of degraded ecosystems on less profitable agricultural land has enormous potential to alleviate these problems. Farmers can continue to produce valuable crops on their prime land, while rebuilding habitat and sequestering carbon on more marginal land.

Read more: The clock is ticking on net-zero, and Australia's farmers must not get a free pass

Almost half of the land requiring restoration is Eucalypt woodlands and almost a fifth is Acacia forests and woodlands. Areas in most need are:

- the Wheatbelt region of Western Australia

- Central Queensland

- Central West, Tablelands and Riverina areas of New South Wales

- Western Victoria

- the Eyre Peninsula and southeast South Australia.

Restoring native vegetation at selected sites would involve actions such as fencing to keep livestock away, pest removal, soil preparation and planting.

As well as direct restoration costs, our costings also included compensation payments to farmers and other landholders, for the cost of retiring the land from farming.

We identified the sites across Australia where revegetation would be most cost-effective. These are the places where land requires the least revegetation work and returns the lowest profit to farmers, thus minimising stewardship payments.

In practice, we recommend restoration sites be secured through voluntary arrangements with land holders.

Cost-Effective Conservation Solutions

We estimate the required restoration would cost approximately A$2 billion annually for 30 years. To put this in perspective, it’s about 0.3% of the federal government’s annual spending last financial year and about 6% of what Australia spends annually on defence.

The restoration project would restore habitat and ecosystem services in our most degraded landscapes. It would expand threatened species’ habitat and re-establish ecosystem functions such as pollination and erosion control.

The revegetation would also help tackle climate change by drawing down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it. We estimate 913 million tonnes of greenhouse gases would be stored over 55 years.

After a decade of vegetation growth, 13 million tonnes would be stored annually – equal to 16% of the emissions reduction required under Australia’s Paris Agreement obligations.

We applied those figures to plausible carbon price scenarios where prices rise 5-10% per year from $15 per tonne, reaching $24-39 per tonne by 2030. If the carbon stored by the project was translated into carbon credits, the potential revenue could be between $12 billion and $46 billion.

The upper end of that estimate would more than cover the costs required to implement the plan. An intensive revegetation effort would also create jobs, mostly in rural areas.

Read more: Loved to death: Australian sandalwood is facing extinction in the wild

Success Is Possible

Australia’s environment laws have comprehensively failed to protect nature. This has been compounded by a lack of adequate funding for environmental management, threatened species protection and ecological restoration.

Without doubt, the national project we describe is ambitious. But existing projects are showing the way. In southwest Western Australia, for example, the Gondwana Link program has so far restored 13,500 hectares of marginal farmland, and also aims to connect 100,000 hectares of existing bushland.

Turning around the state of Australia’s environment requires big thinking and an even bigger government and public commitment. But as our research shows, restoring our degraded landscapes is both attainable and affordable.

Read more: Climate change is testing the resilience of native plants to fire, from ash forests to gymea lilies ![]()

Bonnie Mappin, PhD Candidate, Conservation Science, The University of Queensland; James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland, and Lesley Hughes, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How fussy eating and changing environments led to the diversity of sharks today (and spelled the end for megalodon)

Before humans and early primates, before dinosaurs, and even before trees, there were sharks. Sharks have been around for more than 400 million years (although how long exactly remains contested). They have survived five major mass extinctions.

But the sharks of long ago are not like the ones we see today. In fact, we still understand quite little about their long-term evolution. Our research, published today in the journal Current Biology, demonstrates how shark evolution over the past 83 million years has been driven by diet preference and climate change — leading to the diversity we see today.

As it turns out, being picky about your prey is a risky game for sharks to play.

When The Scales Tipped

One of the more peculiar patterns in biology is for very closely related orders of living animals to have greatly different numbers of species. A notable example is the difference in species number between mackerel sharks (the Lamniformes order) and ground sharks (the Carcharhiniformes order).

Both orders share nearly 170 million years of evolutionary history, and both have species found the world over. However, there are only 15 species of Lamniformes known today (including the great white shark), compared to more than 290 species of Carcharhiniformes (including hammerheads, tiger sharks and many species found on coral reefs).

But why do some orders of shark thrive, while others dwindle? To find out, we turned to the fossil record.

The fossil record reveals shark species in prehistoric times followed a very different pattern to species alive today. Before the “age of dinosaurs” ended some 66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous Period, Lamniformes were more diverse than Carcharhiniformes.

To investigate this shift, we looked at changes in the shapes of shark teeth over the past 83 million years.

Why Teeth?

Unlike their soft cartilaginous skeleton, shark teeth are made up of a substance called “enameloid”, making them very hard. Sharks also continuously grow new teeth, which means their teeth provide an almost continuous fossil record.

Luckily, the shapes of shark teeth also provide rich information on their diets. For instance, a fish-eating shark is likely to have pointy, narrow teeth — often with multiple cusps to increase its chances of catching slippery prey (see the image of the mako shark below, a predominately bony-fish specialist).

By comparison, a shark that specialises in hunting seals is more likely to have broad teeth, which may be serrated to help with cutting. It is precisely this variation in tooth shape which we focused on in our latest study.

By examining more than 3,000 teeth, we found a clear link between changes in tooth shape over time and changes in the environment that took place during and after the end-Cretaceous mass extinction — the same event that wiped-out non-bird dinosaurs about 66 million years ago.

Plenty Of Fish, Yet Sharks Can Be Choosy

During the Cretaceous, when Laminformes were more abundant, many shark species lived in inland seas that were common at the time. One example was the Western Interior Seaway, which divided North America into east and west “subcontinents”.

However, towards the end of the Cretaceous, these inland seas started disappearing. Sea levels lowered and exposed entire chunks of land. Inland seas are rare today (the Caspian Sea is one example, but it too is receding).

Read more: The Caspian Sea is set to fall by 9 metres or more this century – an ecocide is imminent

The reduction in these marine ecosystems led to a significant loss of wildlife, including marine reptiles and cephalopod ammonites (relatives of squid and octopus) upon which many Cretaceous Lamniformes preyed.

As a result, many Lamniformes suffered extinction. On the other hand, Lamniformes with more generalised diets survived the extinction event — as did Carcharhiniformes, which also tend to have more generalised diets.

Why The Meg Went Missing

A similar event may have occurred just a few million years ago to one of the most awe-inspiring lamniform sharks ever known: the meg (Otodus megalodon). The meg was the largest predatory shark species to have existed.

Megalodon was truly an imposing predator that lived during the Miocene and early Pliocene, roughly 4—23 million years ago. Based on its tooth shape, it likely specialised in eating whales, which were very diverse at that time.

Our results show the period in which it lived was also a turning point for Lamniformes, with record-low tooth disparity (a loss in the amount of shape variation).

Although it’s still difficult to know why exactly the meg went extinct, it’s likely its specialised diet, which might have included the giant sperm whale Leviathan melvillei, put it at a disadvantage as cooling climates during the Miocene and Pliocene led to changes in its preferred diet.

To generalise, it seems specialised diets, such as that of the megalodon and some Cretaceous Lamniformes, may have put these species at a greater risk of extinction.

Read more: Making a megalodon: the evolving science behind estimating the size of the largest ever killer shark

Today’s Species

So what does this mean for modern sharks?

By studying the stomach contents of modern Lamniformes, we found most species tend to feed on specific food groups. The thresher and mako sharks feed primarily on bony fish. The basking shark exclusively eats plankton, while adult great white sharks feed mainly on mammals.

Since Lamniformes were much more diverse in the past, our research indicates the low diversity of Lamniformes living today is likely the result of repeated extinction events.

By comparison, modern and past Carcharhiniformes are and were more flexible in their diets. They also benefited directly from the expansion of coral reefs over the past 50 million years.

Thanks to important biological insights offered by the fossil record, we now have evidence dietary specialisation and adaptability to environmental changes likely drove shark evolution over the past 83 million years — leading to the imbalance in Lamniformes and Carcharhiniformes species numbers today.

But what does the future hold? Although it’s hard to say for sure, the news isn’t great for Lamniformes. Of the 15 species remaining, five are classified as “endangered” or “critically endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Another five are considered “vulnerable”.

Lamniformes are also mostly oceanic species with specialised diets, and are therefore particularly vulnerable to chronic overfishing and habitat destruction.

And since our results indicate diet and prey availability underpinned much of the diversity among modern sharks, we think it will probably decide their survival in the future, too.![]()

Mohamad Bazzi, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of Zurich and Nicolas Campione, Senior lecturer, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Loved to death: Australian sandalwood is facing extinction in the wild

The sweet, earthy fragrance of sandalwood oil has made it immensely popular in incense sticks, candles and perfumes. But its beautiful scent may also be its downfall – Australian sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) is facing extinction in the wild.

Despite this, the iconic outback tree is still being harvested in the wild in Western Australia where it’s considered a “forest product”, all to satisfy incense-burners and perfumeries.

Our research, published today, reveals the WA government has known for more than a century that sandalwood is over-harvested and is declining in numbers, with no new trees regenerating. We estimate 175 years of commercial harvesting may have decreased the population of wild sandalwood by as much as 90%.

Today, walking into most sandalwood communities is like walking into a palliative care hospice. There are only old folk there, most of them in terminal decline. There are no youngsters and there are certainly no babies.

It’s time to list sandalwood as a threatened species nationally, and start harvesting only from plantations to give these wild, centuries-old trees a fighting chance at survival.

The Tree Behind The Fragrance

Australian sandalwood, one of about 15 different species of sandalwood that grows across Oceania, is a highly valued economic resource as one of the main types of sandalwood traded internationally. But it’s also immensely important ecologically and culturally.

Aboriginal people have revered it for thousands of years, using it, for example, in smoking ceremonies and bush medicine. These uses take only small portions of the tree and do not endanger the plant, compared to commercial harvesting which kills the tree.

Ecologically, it’s a keystone resource in the arid outback, often flowering and fruiting when other plants are not. It attaches its roots to host plants such as acacias, enabling it to derive some of its nutrients and water from nearby trees and shrubs.

Sandalwood trees can live an estimated 250–300 years, and are capable of withstanding extremely harsh conditions. And yet, the species is extremely fragile in the first few years after germination.

Sandalwood populations have been slowly collapsing for decades from commercial harvesting, land clearing, fire, and grazing (by introduced herbivores such as goats, sheep, cows, rabbits, and camels, and some native species such as kangaroos).

The biggest problems are its lack of regeneration and the rapidly changing climate. Studies suggest there have been virtually no new trees emerging in most sandalwood populations for 60–100 years.

Read more: One-third of the world's tree species are threatened with extinction – here are five of them

There are two main reasons for this. First, sandalwood has lost its seed dispersers, such as burrowing bettongs (small marsupials), which went extinct across most of their range about the same time sandalwood stopped recruiting.

Second, climate change. Sandalwood seeds will only germinate, establish, and survive as seedlings if they get three consecutive good years of rainfall. Under Australia’s increasingly variable rainfall conditions, that’s rarely happening.

Wooden Gold

Sandalwood is one of the most expensive timbers traded in Australia, making it “wooden gold” for the WA government’s forestry department, the Forest Products Commission.

The oil from this native plant is used in perfumes, soap, and moisturisers, and the heartwood “goes up in smoke” as incense in temples and homes, particularly throughout Asia.

Read more: Photos from the field: capturing the grandeur and heartbreak of Tasmania's giant trees

The WA government currently harvests old-growth sandalwood trees almost exclusively from the wild, where the oldest trees have the best oil quality. Plantations do exist, but they are not yet being fully utilised to replace wild-sourced timber.

Our research delved into more than 100 scientific papers, unpublished theses, parliamentary reports and historical documents, and found scientists have repeatedly warned the WA government of the tree’s dire situation.

For example, a century ago (in 1921), in a report to the head of the WA Forests Department, Charles Lane-Poole, Forests Department official Geoffrey Drake-Brockman expressed fears sandalwood harvesting was sending the species extinct in the wild. He recommended the industry start harvesting from plantations instead, writing:

The State Government’s profit (from better managed harvesting) would enable the Forests Department to establish large plantations of sandalwood so that when the natural supplies cut out, the plantations would supply the market requirements.

Years later, in 1958, another report for the WA Forests Department warned:

The sandalwood tree is approaching extinction. The story of the geographical movement of the (sandalwood) industry across WA is the story of the rise and decline of the industry. All too commonly extinction followed exploitation.

Early in the industry’s history, fears were expressed as to the possibility of the future exhaustion of supplies of sandalwood […] Today, the sandalwood tree is approaching extinction […] Little hope of conservation and regeneration remains.

These are just two of scores of examples of warnings documented in our research, all of which have been ignored by successive WA governments. Scientists and others are still putting these same recommendations to the WA government.

It’s Not Too Late To Save It

Fortunately, sandalwood will not completely disappear as there are thousands of hectares of sandalwood in plantations in WA’s agricultural zone. The industry should urgently transition to only harvest from plantations, taking over-harvesting pressure off wild populations.

We urge the WA government to make that transition. The government must list sandalwood as an endangered species now (as it is in South Australia), before it declines to extinction in the wild, and protect and restore surviving populations in innovative programs with Aboriginal rangers and Traditional Owners.

And we urge you, the consumer, to find out more about any sandalwood you purchase.

Plantation-grown products are readily available and just as sweet smelling. Your support will help the industry transition away from wild-harvested plants that need all the help they can get.

Read more: Climate change is testing the resilience of native plants to fire, from ash forests to gymea lilies ![]()

Richard McLellan, PhD candidate, Charles Sturt University; David M Watson, Professor in Ecology, Charles Sturt University, and Kingsley Dixon, John Curtin Distinguished Professor, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘Singing up Country’: reawakening the Black Duck Songline, across 300km in Australia’s southeast

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of people who have died.

Songlines criss-cross across Australia. They are one of the foundational spiritual features of the world’s oldest continuing culture.

Australian Aboriginal peoples had oral cultures: while there are no Bibles or Qurans to document their spirituality, the Dreaming stories of Ancestral creators who formed the land and the features were shared through song. By walking and singing the songlines, those creators are celebrated by the passing generations.

Most of our knowledge of songlines comes from Aboriginal peoples in central and northern Australia, a well-known example being the Seven Sisters Songline, which crosses much of Australia from the west coast to the east.

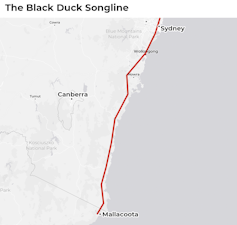

But, due to invasion and attempted cultural destruction since 1788, knowledge of songlines in southeast Australia has been limited. Now, new research has begun reawakening a dormant Black Duck Songline covering 300 km along the New South Wales South Coast.

Read more: Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is a must-visit exhibition for all Australians

Umbarra And Wumbarra

The Black Duck Songline, as current Aboriginal knowledge holders confirm, travels up the South Coast from over the Victorian border to the Hawkesbury River, north of Sydney, passing through many important cultural locations of the Yuin and Dharawal peoples of the region.

The name comes from the Pacific Black Duck (Anas superciliosa), known as Umbarra to the Yuin and Wumbarra to the Dharawal.

The Yuin story of Umbarra comes from Wallaga Lake near Narooma on the NSW far south coast. Umbarra is an animal hero, rather than a Creator, and is the totem and protector of the Yuin peoples from the Dreaming.

A Yuin man, Merriman, had Umbarra as his totem. When his people were in danger, Umbarra warned them so they could take refuge on what is now called Merriman’s Island in Wallaga Lake.

Umbarra became the Yuin protector, and, through kinship linkages, the bird is equally important to the Dharawal.

One of the authors of this piece, Robert Fuller, was exploring the astronomy and songline connections of the Saltwater Aboriginal peoples of the NSW coast. Through a yarning process, speaking to Yuin and Dharawal knowledge holders about the cultural astronomy of their communities, the importance of Umbarra to the Yuin peoples became clear, as did the route of the songline.

The Black Duck Songline has now been traced through multiple Aboriginal communities. Knowledge holders speak about how their people travelled along songlines for trade, to attend ceremonies and to access resources.

Read more: How ancient Aboriginal star maps have shaped Australia's highway network

How A Songline Is Reawakened

A songline is not just a map across Country.

It is a celebration of the stories which make up the songline, and these stories are encompassed in the form of song. The melody stays consistent as a songline passes through different language groups and dialects along the route.

A songline is never extinguished, although the Country through which it passes may be dying because it is not being sung. This has given rise to the Aboriginal expression to “sing up Country”: refreshing the songs and the Country to which the songs belong.

The Black Duck Songline was not unknown to the knowledge holders of the South Coast, but the details of the route had begun to be lost. Probably the last public walk of the songline was by Uncle Guboo Ted Thomas (1909-2002), coinciding with the Bicentennial in 1988.

Other knowledge holders who learned from Uncle Guboo have been able to confirm details of the songline, and members of the Yuin and Dharawal communities are keen to recover the full knowledge of the route of the songline.

After the Hawkesbury River, it is possible the Black Duck Songline may continue north, eventually turning west and south, via the Narran Lakes and the Snowy Mountains, connecting with its origin on the Gippsland Coast, forming a circle.

The major focus of the reawakening of the songline will be to find the songs that make up the story and try and connect them in the correct sequence and with the correct spiritual locations along its route.

If the Black Duck Songline can be awakened, this could be a model for the recovery and reawakening of other songlines in areas of Australia where Aboriginal knowledge has been suppressed.![]()

Robert S. Fuller, Adjunct fellow, Western Sydney University; Graham Moore, Yuin Elder, Indigenous Knowledge, and Jodi Edwards, Tutor, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Better building standards are good for the climate, your health, and your wallet. Here’s what the National Construction Code could do better

The recent IPCC report highlighted we must urgently transition to a low carbon future. One low hanging fruit is to improve the sustainability of new and existing housing.

Minimum performance and quality requirements for new housing in Australia are set via the National Construction Code. The last significant change was in 2010 with the introduction of the six-star requirements. These requirements are at least 40% less stringent than international best practice.

A suite of proposed changes to energy efficiency section of the National Construction Code are a good step forward. However, a lot more can be done.

And improving building quality requirements isn’t just good for the climate — it also delivers enormous health benefits, slashes energy bills and makes our homes more comfortable.

Read more: Low-energy homes don't just save money, they improve lives

Change Is Underway

Proposed energy efficiency changes for the National Construction Code 2022 include:

• an increase in the minimum thermal performance of homes from six stars to seven stars

• whole-of-home requirements for performance of heating, cooling, hot water, lighting and pool heating equipment

• new provisions designed to allow easy addition of on-site solar photovoltaic panels and electric vehicle charging equipment

• additional ventilation and wall vapour permeability requirements.

The Regulatory Impact Statement — a document aimed at helping government officials understand the cost-benefit impacts of a proposed regulatory change — has also been released.

Overall, it finds the costs for proposed more stringent requirements will outweigh the benefits for society.

In better news, it finds that for the majority of households, any increase in mortgage repayments from the additional costs of higher standards will be offset by a reduction in energy costs. In other words, you save so much on energy costs over time that it doesn’t matter you have to borrow more to pay for these building features.

There is critique of the Regulatory Impact Statement from stakeholders such as the Victorian government and the Green Building Council of Australia. Critics have pointed to the limited consideration of health and well-being, the impact to the energy network, and the climate emergency.

There are also issues with key economic assumptions which do not reflect environmental impacts of decisions and concerns delivery costs to households have been overestimated, potentially encouraging a “do nothing” policy position.

Public consultation is open until October 17.

What Do The Changes Mean?

The proposed changes are important steps towards reducing carbon emissions. Currently less than 5% of new housing in Australia is built to achieve seven or more stars. These changes will affect thousands of new dwellings every year.

The seven-star standard will reduce heating and cooling energy for new housing by about 24%, slashing energy bills. The changes future-proof housing by reducing costs to add renewables or electric car charging once the house is built.

And with issues of mould and condensation in Australian housing, changes will make our housing healthier.

Historically, higher standards have been met by boosting specifications like insulation and double glazing. These new standards will shift attention to cost-effective strategies like orientation and site-responsive design, as it becomes harder to achieve higher stars through specifications alone.

Research from Sustainability Victoria’s Zero Net Carbon Homes program show homes can increase performance by one star simply changing from their worst to best orientation.

There’s Room For Improvement

These proposed changes are a good step forward. However, more can be done.

A decade ago research and case studies showed that seven star housing was achievable for little additional costs.

YourHome and developments like The Cape make seven or more star house designs freely available, showing we don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

The recently announced Green Star Homes Standard will also help to drive innovation beyond minimum performance requirements.

Our energy regulations are still measured per square metre (rather than per dwelling/person) and are predominantly concerned with operational energy demand.

To further reduce carbon emissions, we need to acknowledge the influence of house size and materials usage on total energy consumption and factor in the carbon footprint of building materials.

Additionally, the code does not use future climate data when demonstrating compliance. This means that our housing may not be fit for purpose in our future climate.

We will need more focus on summer performance. This should include performance in late summer and autumn, when the sun is lower in the sky, but extreme heat will be more likely. This will require solutions like adjustable shading.

As-built verification is a critical inclusion in new schemes such as Green Star Homes; we need similar mechanisms in our construction code to ensure as-built compliance. There is no point improving regulations on paper if we can’t deliver it in practice.

While the focus of these changes is on new housing, we must not forget the millions of existing homes which need to undergo deep retrofits to improve sustainability and performance. The new standards will need careful adaptation to suit alteration and addition projects.

Tools like the National Scorecard Initiative aim to help homeowners in existing dwellings improve performance but more could be done with regulations to ensure existing housing is part of the push towards a sustainable housing future.

Read more: Sustainable housing's expensive, right? Not when you look at the whole equation ![]()

Trivess Moore, Senior Lecturer, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University; Alan Pears, Senior Industry Fellow, RMIT University; Erika Bartak, PhD Candidate (& ESD Consultant), Melbourne School of Design, The University of Melbourne, and Nicola Willand, Lecturer, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rosemary in roundabouts, lemons over the fence: how to go urban foraging safely, respectfully and cleverly

Does anything beat the experience of finding a wild mulberry tree and stuffing a handful of fresh juicy berries in your mouth? Have you ever roasted potatoes with a sprig of rosemary taken from an overgrown nature strip?

COVID lockdowns have encouraged more people to explore their neighbourhoods and appreciate their local green spaces, where edible plants are often growing freely. Alongside the joy in eating something freely harvested, foraging can help us learn about plants, become better environmental stewards, and bring together communities.

It can also help us notice changes in season, weather and climate. So with spring upon us, how do you forage safely, respectfully, and legally?

Wild, Edible Plants Thrive In Cities

The locations of Sydney and Melbourne were chosen by colonists, in part, because they’re within large food basins. Many edible species existed well before colonisation, thanks to the favourable climate, shape of the coastline and custodianship of Country.

Edible native plants, from ground covering warrigal greens to the huge canopies of Illawarra plum trees, are still naturally growing all over southeast Australian cities. Further north, macadamias, lemon myrtles and finger limes thrive, and pigface is common on sand dunes along coastal towns.

Today, edible plants thrive despite the disturbances of soils and water from urbanisation. Fruit trees, for example, emerge spontaneously on the edges of park lands, in vacant lots and in people’s gardens.

In some cases, urbanisation is actually responsible for the growth and distribution of edible plants.

Birds, rats, bats broaden the trajectories of mulberry, loquat, and papaya seeds by eating them and expelling the seeds somewhere else. This is also how mulberries, which European settlers introduced to Australia, now grow in most Australian cities.

Kumquat, citrus, and fig trees are also very common in tropical and temperate climates. And keep an eye out for blackberry vines. They’ve created an immense environmental problem, although the fruit is delicious, and grow best in NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.

Think Before You Pick

But foraging is not a free for all, and doing it safely and respectfully is important.

First and foremost, in Australia, wherever you walk, you are on Country. Take a moment to remember that although urban foraging may be new to you, Aboriginal people have always gathered native plants while caring for Country.

Foraging also carries possible risks to your own health. Some plants in urban areas are poisonous, such as the castor oil plant and many gum trees. Plants could also be contaminated from pollution in the air, water and soil, and by chemical sprays.

You can learn about some of the possible environmental contaminants in your neighbourhood here, and there are a few services like VegeSafe that test soil samples for metals.

Always start by considering the past and current uses of the land where you’re foraging. Was the land once industrially zoned? Do dogs urinate there? Make sure you always wash foraged food.

Legally, plants are the property of whoever owns the land on which they’re growing. That means foraging for food on private land is legal, as long as you either own the land or have the owner’s permission.

Read more: Our land abounds in nature strips – surely we can do more than mow a third of urban green space

But if food is accessible on public land — such as lemons or bananas hanging over a fence, or rosemary and parsley planted as ornamentals in a park or street shoulder — you can harvest them. Just take what you need, and leave plenty for others.

Foraging Respectfully

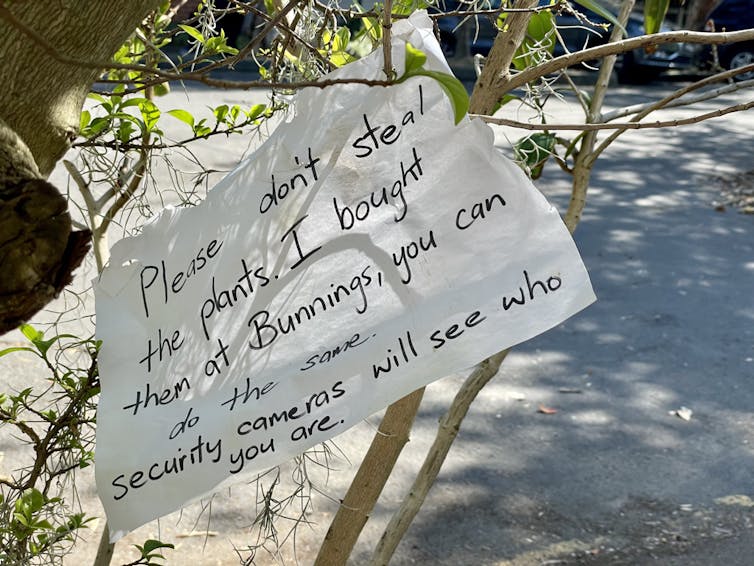

There are different cultures around growing and sharing food, depending on the local area. For example, many neighbourhood nature strips are technically owned by the council, but planted and tended by residents.

Community gardens and even streets with nature strips may have their own harvesting rules. Some groups like Green Square Growers encourage spontaneous harvesting. Others, such as Sydney City Farm, carefully document volunteer hours then allocate produce accordingly.

Since 2016, we have been working in various suburbs of Sydney to conduct research on urban gardening. We discovered people often work with plants to develop a sense of place that goes well beyond what’s visible in their gardens.

We found networks of neighbours grow together with plants on street edges, through exchanging cuttings, seeds, tips, stories and produce. Coming across a row of trees heavy with olives on a nature strip may feel like a lucky discovery, but these plants are probably watered, pruned, and whitewashed for winter by one or more gardeners.

For someone who has carefully netted a fruit tree to protect it from bats and cockatoos, or who has patiently tended a vine for three years before their first passionfruit appears, there’s nothing more infuriating than a stranger harvesting.

On the other hand, helping yourself to a fragrant feijoa tree weighed down by ripe fruit makes sense, when the fruits would otherwise fall, rot and go to waste.

When possible, ask residents about the plants growing on or around their properties. Conversations about what’s growing in neighbourhoods build so-called “civic ecologies” — actions that bring together environmental and civic values, building neighbourly connections around common interests and care for shared places.

Learn From Foraging Celebrities

In Australia, a hand full of “foraging” celebrities have brought attention to this age old practice. They see foraging as an opportunity to learn about what’s growing where, and why.

Read more: Supermarket shelves stripped bare? History can teach us to 'make do' with food

In Sydney, Randwick Council Sustainability Educator Julian Lee, has created a Scrumper’s Delight participatory map that records edible plants growing in public spaces. Sydney artist and activist Diego Bonetto — aka The Weedy One — brought a wealth of planty knowledge from Piedmont, Italy to Australia in the 1990s, and since then his passion has evolved to a public pedagogy about respectful foraging.

Milkwood Permaculture offer tips, even on foraging sea weed. The Melbourne Forager on Instagram makes urban foraging hip. And a growing number of Indigenous businesses, such as Indigigrow, share Indigenous knowledge by selling plants people can recognise outside their gardens.

Foraging in cities is fun, it helps us remember we’re part of ecosystems, and we have a responsibility to care for Country. So keep in mind principles of reciprocity, and go forth and learn what’s growing in your city.

Read more: Farming the suburbs – why can’t we grow food wherever we want? ![]()

Alexandra Crosby, Associate Professor, University of Technology Sydney and Ilaria Vanni, Associate Professor, International Studies and Global Societies, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Why sweet-toothed possums graze on stressed, sickly-looking trees

From time to time, I’m contacted by people who have a favourite garden tree that seems suddenly to be in serious decline and lacking healthy foliage. Often the decline has been occurring over many months, but when first noticed, the change seems to have been dramatic.

The symptoms described accord with grazing — where animals nibble at foliage until it’s quite degraded — so I ask if they have seen brushtail possums in the tree.

More often than not the answer is a firm, “No!”

However, just because you haven’t seen them, it doesn’t mean the possums aren’t there. One owner, who said they weren’t aware of any possums, checked at night with a torch; they counted 56 possums in a single, sick-looking river red gum.

It’s not uncommon for one tree within a group of the same species to be grazed while other trees are left alone.

In the early evening, a steady stream of possums can be seen coming from all directions and from nesting sites in other trees hundreds of metres away, all homing in on the one sickly specimen.

To the human eye, this seems very strange behaviour. Wouldn’t the possums be better off grazing on a healthy tree?

But possums are real tree experts and know exactly what they are doing.

Read more: Curious Kids: if trees are cut down in the city, where will possums live?

It’s All About The Sugar Content

The common brushtail possum, Trichosurus vulpecula, will eat both plants and small animals if given the chance, but plants form the bulk of their diet. Eucalypt leaves are a favourite, but they’ll nibble the leaves of other plants in our gardens.

So what is going on when one tree is grazed in preference to others? One of the main drivers revolves around sugar.

When plants photosynthesise, one of the first products of the process is sugar. Sugars are carbohydrates made up of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms and one of the most common is glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆), which is the common sugar used in coffee, tea and cooking.

Sugar may be copping a bit of stick at present for its role in human diets, but in terms of plant metabolism, glucose is a marvellous molecule.

It is made from simple and ready available ingredients. It is soluble in water and can be easily transported around inside the plant. And it stores significant energy.

This makes it a very accessible and desirable molecule within the plant, but too much glucose in solution can cause problems for the plant and attract grazers keen on an easy sugar hit.

The plant has evolved an elegant solution to these problems. It simply takes two or more glucose molecules and bonds them together to make starch‚ which is not very soluble in water, contains lots of energy and so is an ideal storage form of carbohydrate.

The plant converts any excess glucose that it has into starch for later use when things might be tougher.

What’s This Got To Do With Possums, Again?

When a plant is stressed, one of its first responses is to mobilise its resources. Among other things, it often converts its starch reserves back to sugar. As soon as this happens, the stressed plant becomes sweeter than its healthier neighbours — and brushtail possums know it.

Some stressed trees emit chemicals that can be picked up by grazers. In other cases, the grazers may come upon a stressed tree by chance.

In either case, the grazer gets an increased sugar hit and so will return to the tree when the opportunity presents; other grazers may follow.

In the case of brushtail possums, a possum may return to the same tree night after night and, despite territorial disputes, may be joined by other possums in a feeding feast.

A Stressed Tree Is A Grazer’s Delight

Initially, the tree may have been stressed by drought, poor nutrition or waterlogged soils. The increased grazing then adds to the level of stress.

And when lots of leaves are removed, many trees such as eucalypts, elms, oaks and even deciduous conifers will respond by producing new leaves and shoots. These lovely new leaves and shoots are soft and loaded with sugars — a grazer’s delight.

With more stress, the tree converts more and more starch into sugar and produces yet more new leaves and shoots — so the grazers get a sweet and nutritious reward for their efforts. They will keep returning to the same tree.

All of this extra grazing comes at a price to the tree, which is exhausting its starch reserves, but getting little or no reward from the sugar produced.

Eventually, the tree will succumb. It may die from starvation due to the loss of its reserves and the failure of new foliage to survive long enough to photosynthesise. Or it may die from another environmental stress or a pest or disease attack.

Grazing can be lethal to a tree, but you can see why the grazers keep coming back.

Stressed trees are an easy and rewarding energy source. Perhaps, like us, the possums become addicted to a high sugar diet and simply can’t resist returning to the tree — even if, in the end, the tree is grazed to death.

Read more: Hidden housemates: when possums go bump in the night ![]()

Gregory Moore, Doctor of Botany, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham's Beach

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.

The National Shorebird Monitoring program (started as the Shorebirds 2020 project initiated to re-invigorate monitoring around Australia) is raising awareness of how incredible shorebirds are, and actively engaging the community to participate in gathering information needed to conserve shorebirds.

In the short term, the destruction of tidal ecosystems will need to be stopped, and our program is designed to strengthen the case for protecting these important habitats.

In the long term, there will be a need to mitigate against the likely effects of climate change on a species that travels across the entire range of latitudes where impacts are likely.

The identification and protection of critical areas for shorebirds will need to continue in order to guard against the potential threats associated with habitats in close proximity to nearly half the human population.

Here in Australia, the place where these birds grow up and spend most of their lives, continued monitoring is necessary to inform the best management practice to maintain shorebird populations.

BirdLife Australia believe that we can help secure a brighter future for these remarkable birds by educating stakeholders, gathering information on how and why shorebird populations are changing, and working to grow the community of people who care about shorebirds.

To find out more visit: http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/shorebirds-2020-program

Aussie Bread Tags Collection Points

AMA Warns Against Privatising Aged Care Assessments

Aged Care Provider Reports To Strengthen Individual Care

Hip Fracture Care – Not All It’s Cracked Up To Be

- A partial hip replacement for the ball

- A total hip replacement for both the ball and socket

- Screws and possibly a plate to hold the fracture in place

- A metal rod through the thigh bone to secure the fracture

Nominations Open For Australia’s First Council Of Elders On Aged Care

The Historic Palm Grove At The Royal Botanic Garden Sydney

Aged Care Residents To Welcome Back Visitors

Only 3.8% of Australian aged care homes would meet new mandatory minimum staffing standards: new research

One of the most significant outcomes from the aged care royal commission was the federal government’s commitment this year to mandate minimum staffing levels in residential aged care homes by 2023.

Our study, published today, shows only a tiny fraction of aged care homes would already comply with the new requirements.

Substantial increases in staffing will be needed across the sector, placing even more pressure on an industry already struggling to meet the needs of a growing number of Australians.

Read more: 4 key takeaways from the aged care royal commission's final report

What Are Minimum Staffing Standards?

Minimum staffing standards are designed to ensure all aged care homes have sufficient staff to meet their residents’ care needs. This type of regulation already exists in several countries, including the United States, Japan and Germany.

Japan and Germany both prescribe minimum staff-to-resident ratios. In the United States, homes must have a certain number of staff on site each day and many states regulate the minimum time staff spend with residents. Also, while some countries mandate requirements for all care staff, others target specific roles, such as licensed nurses.

Read more: Want to improve care in nursing homes? Mandate minimum staffing levels

In Australia, licensed nurses include both registered nurses (RNs), who have at least a bachelor’s degree, and enrolled nurses who have completed a two-year diploma.

However, most aged care is provided by unlicensed personal care workers, who don’t need formal qualifications.

Australia’s new staffing standard has three requirements that will be mandatory from October 1, 2023:

providers must ensure residents receive at least 200 minutes of total care per day

at least 40 minutes of that care must be provided by an RN

an RN must be on site for morning and afternoon shifts each day.

These requirements are stated as industry averages with each home’s requirements adjusted based on the relative complexity of their residents’ care needs.

Why Are Minimum Standards Necessary?

The royal commission heard evidence that more than half of all Australian residents in aged care (57.6%) live in aged care homes with inadequate staff.

In the final report, it stated

all too often, and despite best intentions, aged care workers simply do not have the requisite time, knowledge, skill and support to deliver high quality care.

For example, the commission heard testimony from families of residents at an understaffed home in Victoria, where staff didn’t have time to help residents go to the toilet or eat meals, or attend to their clinical care.

The commission also heard about the dangers of not having enough trained nurses. One witness described a regional home where three nurses had to look after up to 80 residents on weekends.

The witness’ father, a resident living with dementia, had been neglected and hospitalised on several occasions due to falls that occurred while left unattended.

What Did We Find?

Our study of historical staffing levels found few aged care homes (3.8%) had staffing above all three requirements of the new standard.

While many homes (79.7%) would meet the requirement to have an RN on site, few had levels above daily requirements for total direct care (10.4%) or RN care (11.1%).

The homes that fell short of these two requirements will need to increase staff time by an average of 43 minutes of total care per day and 18 minutes of RN time per day.

Read more: Nearly 2 out of 3 nursing homes are understaffed. These 10 charts explain why aged care is in crisis

We also found evidence the new standard is likely to cause different pressures for homes across the sector. The homes most at risk of non-compliance are likely to be larger with more residents to care for, located outside metropolitan cities and run by small providers.

Interestingly, while smaller homes were more likely to meet the two requirements about daily minutes, they were much less likely to have an RN on site for two shifts.

So What Needs To Change?

The new minimum standards are a crucial piece of regulation to ensure Australian aged care homes provide sufficient staff to deliver quality care to residents.

However, this requires a substantial expansion of a workforce already under strain. Workforce shortages are already a problem due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with low immigration and additional work demands, such as infection control and handling family requests.

A report published in August by the Committee for Economic Development of Australia suggests even without the minimum standards, Australia’s aged care workforce needs to grow by an additional 17,000 workers per year between now and 2030.

Our study highlights areas requiring urgent action. For example, the new requirements will likely cause a dramatic increase in demand for RNs. While training and retention initiatives announced in the recent federal budget will help, much more will be required, such as improved working conditions and pay, to arrest the decline of RNs in the sector.

In addition, targeted government support will likely be required to help homes outside the major cities, and those smaller in size, to attract appropriate care workers to fill shortfalls.

Such measures will be required to enable a fair transition towards compliance with the minimum staffing standard within the sector.![]()

Nicole Sutton, Senior Lecturer in Accounting, University of Technology Sydney; Deborah Parker, Professor of Nursing Aged Care (Dementia), University of Technology Sydney, and Nelson Ma, Senior Lecturer, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

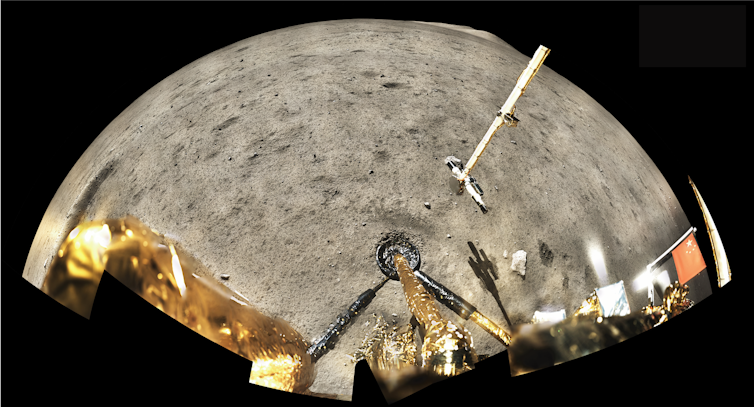

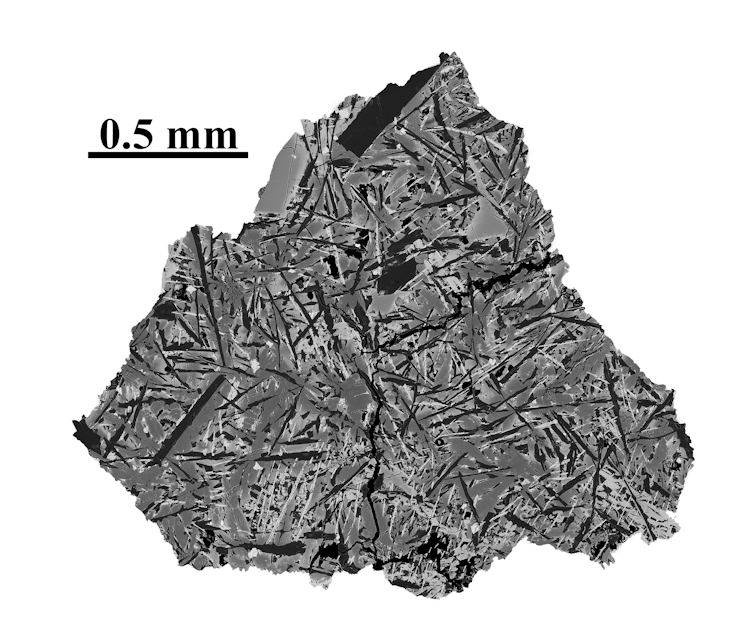

We shaved a billion years off the age of the youngest known Moon rocks, and rewrote lunar geological history