Inbox and Environment news: Issue 514

October 17 - 23, 2021: Issue 514

Aussie Backyard Bird Count 2021

The 2021 event will run from October 18‒24 during National Bird Week. Register as a counter today at: https://aussiebirdcount.org.au/

The Aussie Backyard Bird Count is one of Australia’s biggest citizen science events. This year is our eighth count, and we’re hoping it will be our biggest yet!

Join thousands of people around the country in exploring your backyard, local park or favourite outdoor space and help us learn more about the birds that live where people live.

Taking part in the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is a great way to connect with the birds in your backyard, no matter where your backyard happens to be. You can count in a suburban garden, a local park, a patch of forest, down by the beach, or the main street of town.

To take part, register on the website today, then during the count you can use the web form or the app to submit your counts. Just enter your location and get counting ‒ each count takes just 20 minutes!

Not only will you be contributing to BirdLife Australia's knowledge of Aussie birds, but there are also some incredible prizes on offer.

Head over to the Aussie Backyard Bird Count website to find out more.

Spotted Gums Go Bright Green When It's Raining

The Flannel Flower: Australia’s Symbol For Mental Health Awareness During Mental Health Month - October

Tuckeroo Becoming Troublesome In Pittwater

Waratahs: Look But Don't Steal

Broken Bay - Australian Long Nosed Fur Seals

Birds In Your Garden: Wish You Had More?

Avalon Preservation Association 2021 AGM

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

NSW Government Oversight Of Kangaroo Industry Lacks Transparency, Monitoring And Compliance Parliamentary Inquiry Finds

- the current methodology used by the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment to produce estimates of New South Wales' macropod populations lacks transparency

- the National Parks and Wildlife Service does not have adequate systems to monitor compliance with licence conditions for the non-commercial culling of kangaroos

- That there is a lack of monitoring and regulation at the point-of-kill during both commercial and non-commercial killing of kangaroos

- That the shooting of kangaroos has a profound impact on the mental health of some Aboriginal people, kangaroo carers and rescuers

- That the use of exclusion fencing has the potential to cause disruption to kangaroo migration as well as access to habitat, food and water.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment amend planning policies to require assessment of the impact on kangaroos located within peri-urban developments when assessing development applications;

- That the National Parks and Wildlife Service:

- work with relevant local councils to identify local nature reserves and corridors for resident kangaroo populations on the peri-urban fringe

- develop a plan for protecting further areas of kangaroo habitat in New South Wales through creation of reserves and national parks.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment investigate new technologies for counting kangaroo populations such as the use of infra-red and other camera drone technology.

- That the NSW Government:

- undertake extensive and genuine consultation with Aboriginal peoples to seek their views regarding the commercial and non-commercial culling of kangaroos, and ensure these views are given serious consideration in the development of all future kangaroo management plans

- incorporate the genuine involvement of Aboriginal peoples in the management of kangaroo populations.

- That the NSW Government conduct a review of the impact of exclusion fencing on macropod populations, and that the report be publicly released when complete.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment investigate new technologies for counting kangaroo populations such as the use of infra-red and other camera drone technology.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment use video imaging of kangaroo populations when surveying populations from aircrafts and make this footage publicly available on its website.

- That the Natural Resources Commission review the current methodology for estimating macropod populations in New South Wales.

- That the Natural Resources Commission establish an independent panel of ecologists to examine the scientific evidence for assumptions used in the Kangaroo Management Plan that refer to kangaroo 'abundance', annual population growth, the impact of migration on population counts and the attrition of kangaroos in drought.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment identify, and independently verify, the biological growth rate for each macropod species to better inform setting sustainable quotas under future Commercial Kangaroo Harvest Management Plans.

- That when setting population estimates and harvest quotas, the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment must take into consideration climatic factors such as drought. In times of declared drought, reassessment of quotas should be conducted based on changed conditions, rather than have quotas made on out of date population estimates.

- That the Minister for Energy and Environment not endorse the new Commercial Kangaroo Harvest Management Plan until the recommendations of this inquiry have been considered.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment collect and publicly release data on all joey deaths occurring in the commercial kangaroo industry, including in-pouch, at-foot, and joeys at-foot who have fled.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment include in the Commercial Kangaroo Harvest Management Plan 2022-2026 a requirement that commercial harvesters include the number of orphaned joeys when calculating the count for filling quotas.

- That the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment conduct a full review of the systems for issuing and compliance monitoring of licences to harm kangaroos. The review should aim to increase the rigour and transparency of the licensing and compliance monitoring processes, be conducted in consultation with stakeholders, and be made public.

- That the NSW Government review the 2018 changes to licences to harm kangaroos as a matter of urgency and provide a report to Parliament within 12 months.

- That the National Parks and Wildlife Service employ additional compliance officers to proactively monitor and investigate the non-commercial industry's compliance with the code of practice as well as specific cruelty allegations.

- That the National Parks and Wildlife Service work with RSPCA NSW to ensure the prompt reporting and investigation of breaches of regulatory compliance and cruelty allegations in regards to kangaroos and other wildlife.

- That the National Park and Wildlife Service make it mandatory for persons licensed to harm kangaroos to notify their neighbours, as far as is reasonably practicable, before they commence shooting.

- That the Department of Planning Industry and Environment, specifically including the National Parks and Wildlife Service, and the NSW Police Force, work together to:

- clarify the current investigation and enforcement framework in dealing with complaints concerning kangaroo shooting

- establish a central database to receive, handle or refer complaints to responsible government agencies

- ensure more satisfactory responses to complaints relating to kangaroo shooting.

Crown Land Award Finalists Announced

- Deep Water Land Manager Hall Committee of Glen Innes

- Byrangery Grass Reserve Land Manager

- Glen Innes & District Historical Society Inc.

- Old Bega Hospital Reserve Land Manager

- Patricia Jones of Bega

- Stephen Thatcher of Muswellbrook

- Louise Jenkins of Cooma

- William West of Balmoral

Reputex Report: NT Fracking Plans Will Cost Billions And Triple Australia's Greenhouse Emissions

- The Reputex Report - Analysis of Beetaloo Gas Basin Emissions & Carbon Costs - was commissioned by Lock the Gate Alliance. It calculates potential NT fracking industry growth and the climate mitigation required under three scenarios - low, mid, and high.

- Fracking expansion 2.5 times annual greenhouse emissions; Australia’s overall annual emissions are now around 520 Mt, meaning if the fracking industry expands in the NT as governments plan, it would be responsible for about two and a half times Australia’s annual greenhouse emissions. Based on government and industry gas resource estimates, the report finds Beetaloo GHG emissions would be up to 1.4 billion tonnes under a high production scenario over 20 years.

- Cost of offsetting will be $3-$22 Billion; Based on conservative emissions calculations for methane, the report then calculates the ‘carbon liability’, i.e. the cost of offsetting emissions using Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs), to range from $3 Billion (low scenario) to $22 Billion over 20 years.

- Gas will be commercially unviable; The Reputex Report concludes, “In line with NT policy and Recommendation 9.8 of the Pepper Inquiry, the inclusion of carbon costs is likely to have significant implications for the commercial viability of Northern Territory gas basin projects, with potential for emissions liabilities to add between $1 - $2.5 per GJ to the cost of Beetaloo basin gas, varying with the modelled production scenario.”

- In terms of Australia’s carbon budget in the event global warming is kept to Paris Agreement levels, the report notes: “The development of the Beetaloo Sub-basin under a mid to high scenario... is likely to have a significant impact on Australia’s remaining carbon budget, with modelled outcomes representing between 3 to 5 per cent of Australia’s remaining carbon budget remaining (2°C scenario). For a 1.5°C scenario Beetaloo Sub-basin gas could represent 10 to 27 per cent of Australia’s total carbon budget.”

- The report notes in its conclusion: “Beetaloo basin gas emissions represent a large source of additional GHG emissions entering the Australian economy at a time when rapid global emission reductions are necessary to limit the effects of global warming. To this end, new oil and gas fields from 2021 have been modelled by the IEA to be inconsistent with a net-zero pathway.”

Bylong Coal Mining Saga Set To Continue

Morrison set for Glasgow but has to finish packing his bag

Scott Morrison has declared he will attend next month’s Glasgow climate conference, as the Coalition parties prepare to consider the government’s revised climate policy.

Morrison, who delayed a final decision on whether to go to COP26, and at one stage seemed inclined not to, said on Friday he had confirmed his attendance overnight.

But he still has to land his new climate policy, including a net zero target for 2050, with the Nationals.

The Nationals meet on Sunday, and will be briefed by Energy Minister Angus Taylor. The Liberal parliamentary party will meet on Monday.

The indications on Friday were that a majority of the Nationals party room favoured backing the 2050 target. But a minority will not be for turning, and confusion and uncertainty remain about the plan’s detail and what is in it for regional communities.

After the party meetings there could be further work needed. The policy will then have to return to cabinet – which discussed it on Wednesday – for final approval.

Landing an unequivocal sign up to net zero has become the central yardstick for the policy. But the policy’s medium term ambition will be a key test for how Australia’s position is received internationally.

At present Australia is committed to reducing emissions by 26-28% on 2005 levels by 2030, and it is generally recognised this must be improved.

The government has repeatedly stressed Australia is projected to beat this target. Other countries, however, will be critical if the medium term ambition is too modest, or is put in the form of a “projection” rather than a concrete fresh target.

Nationals sources on Friday reported MPs are getting blowback from their conservative membership base in Queensland about the prospective turnaround on climate policy.

Apart from largesse for regional Australia, Nationals are looking for hard evidence in the policy that their constituents will be protected in the transition to a low emissions economy. The party’s Senate leader, Bridget McKenzie, has adopted a high profile in publicly prosecuting the case for strong protections.

The policy will be heavy on detail about the technology the government says will achieve the reduced emissions.

Morrison told a news conference on Friday “net zero was an outcome that I outlined at the beginning of this year, consistent with our Paris commitments.

"The challenge is not about the if and the when, the challenge is about the how.

"And I’m very focused on the how, because the global changes that are happening in our economy as a result of the response to climate change have a real impact, and they will have a real impact here in Australia.”

He said the plan he was taking forward “is about ensuring that our regions are strong, that our regions’ jobs are not only protected, but they have opportunities for the future.

"It’s not just about hitting net zero. That’s an important environmental goal. But what’s important is that Australia’s economy goes from strength to strength, and the livelihoods and the lives that Australians know, particularly in rural and regional areas, are able to go forward with hope and with confidence.”

The push to sign up to net zero has been boosted in the last week by the Business Council of Australia and a campaign by News Corp tabloids. The Reserve Bank has reiterated the importance of a climate policy that is credible in the eyes of investors.

The prime minister’s trip will include attending the G20 meeting in Rome before the climate conference.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Greater Sydney Water Strategy Open For Feedback

- Improving water recycling, leakage management and water efficiency programs, which could result in water savings of up to 49 gigalitres a year by 2040.

- Extending a water savings program, which has been piloted in over 1000 households and delivered around 20 per cent reduction in water use per household and almost $190 in savings per year for household water bills.

- Consideration of running the Sydney Desalination Plant full-time to add an extra 20 gigalitres of water per year.

- Expanding or building new desalination plants to be less dependent on rainfall.

- Investigating innovations in recycled water to improve sustainability.

- Making greater use of stormwater and recycled water to cool and green the city and support recreational activities.

Warragamba Dam Raising Project EIS On Public Exhibition

NSW Government Plan To Revitalise Peat Island And Mooney Mooney Released

- Nearly 270 new homes at Mooney Mooney to deliver more housing supply,

- Retention of nine unlisted historical buildings on the island, and four on the mainland, to be restored and used for new community and commercial opportunities,

- New retail and café or restaurant opportunities,

- Approximately 9.65 hectares of open space, including opportunities for walking and cycling tracks, parklands and recreational facilities,

- Retention of the chapel and surrounding land for community use, and

- 10.4 hectares of bushland dedicated as a conservation area.

Threatened Tasmanian Forests Gain Legal Protection

Widespread collapse of West Antarctica’s ice sheet is avoidable if we keep global warming below 2℃

Rising seas are already making storm damage more costly, adding to the impact on about 700 million people who live in low-lying coastal areas at risk of flooding.

Scientists expect sea-level rise will exacerbate the damage from storm surges and coastal floods during the coming decades. But predicting just how much and how fast the seas will rise this century is difficult, mainly because of uncertainties about how Antarctica’s ice sheet will behave.

The recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projections of Antarctica’s contribution to sea-level rise show considerable overlap between low and high-emissions scenarios.

But in our new research, we show the widespread collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is avoidable if we can keep global warming below the Paris target of 2℃.

In West Antarctica, the interior of the ice sheet sits atop bedrock that lies well below sea level. As the Southern Ocean warms, scientists are concerned the ice sheet will continue to retreat, potentially raising sea level by several meters.

When and how quickly this process could happen depends on a number of factors that are still uncertain.

Our research better quantifies these uncertainties and shows the full impact of different emissions trajectories on Antarctica may not become clear until after 2100. But the consequences of decisions we make this decade will be felt for centuries.

A New Approach To Projecting Change In Antarctica

Scientists have used numerical ice-sheet models for decades to understand how ice sheets evolve under different climate states. These models are based on mathematical equations that represent how ice sheets flow.

But despite advances in mapping the bed topography beneath the ice, significant uncertainty remains in terms of the internal ice structure and conditions of the bedrock and sediment below. Both affect ice flow.

This makes prediction difficult, because the models have to rely on a series of assumptions, which affect how sensitive a modelled ice sheet is to a changing climate. Given the number and complexity of the equations, running ice-sheet models can be time consuming, and it may be impossible to fully account for all of the uncertainty.

To overcome this limitation, researchers around the world are now frequently using statistical “emulators”. These mathematical models can be trained using results from more complex ice-sheet models and then used to run thousands of alternative scenarios.

Using hundreds of ice-sheet model simulations as training data, we developed such an emulator to project Antarctica’s sea-level contribution under a wide range of emissions scenarios. We then ran tens of thousands of statistical emulations to better quantify the uncertainties in the ice sheet’s response to warming.

Low Emissions Prevent Ice Shelf Thinning

To ensure our projections are realistic, we discounted any simulation that did not fit with satellite observations of Antarctic ice loss over the last four decades.

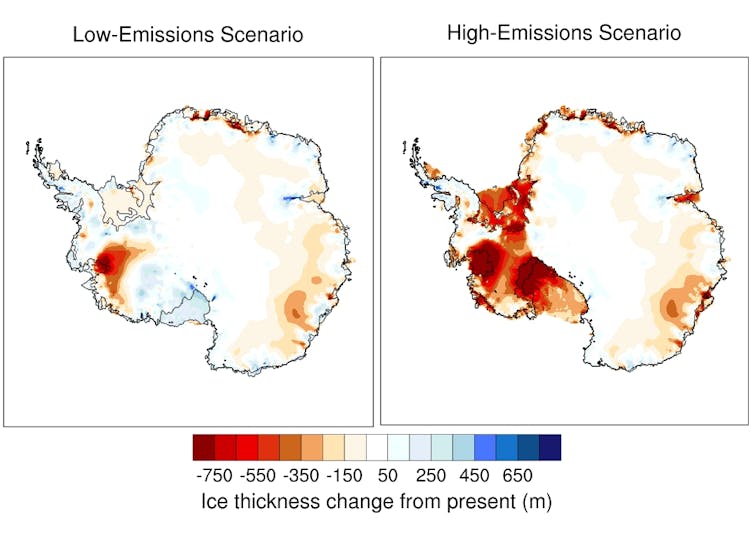

We considered a low-emissions scenario, in which global carbon emissions were reduced quickly over the next few decades, and a high-emissions scenario, in which emissions kept increasing to the end of the century. Under both scenarios, we observed continued ice loss in areas already losing ice mass, such as the Amundsen Sea region of West Antarctica.

For the ice sheet as a whole, we found no statistically significant difference between the ranges of plausible contributions to sea-level rise in the two emissions scenarios until the year 2116. However, the rate of sea-level rise towards the end of this century under high emissions was double that of the low-emissions scenario.

By 2300, under high emissions, the Antarctic ice sheet contributed more than 1.5m more to global sea level than in the low-emissions scenario. This is because the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapses.

The earliest warning sign of a future with a multi-metre Antarctic contribution to sea-level rise is widespread thinning of Antarctica’s two largest floating ice shelves, the Ross and Ronne-Filchner.

Read more: Antarctica's ice shelves are trembling as global temperatures rise – what happens next is up to us

These massive ice shelves hold back land-based ice, but as they thin and break off, this resistance weakens. The land-based ice flows more easily into the ocean, raising sea level.

In the high-emissions scenario, this widespread ice-shelf thinning happens within the next few decades. But importantly, these ice shelves show no thinning in a low-emissions scenario — most of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet remains intact.

Planning Our Future

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep warming well below 2℃. But current global government pledges commit us to 2.9℃ by 2100. Based on our emulator projections, we believe these pledges would lead to a 50% higher (70cm) Antarctic contribution to sea-level rise by the year 2300 than if warming remains at or under 2℃.

But even if we meet the Paris target, we are already committed to sea-level rise from the Antarctic ice sheet, as well as from Greenland and mountain glaciers around the world for centuries or millennia to come.

Continued warming will also raise sea levels because warmer ocean water expands and the amount of water stored on land (in soil, aquifers, wetlands, lakes, and reservoirs) changes.

To avoid the worst impacts on coastal communities around the world, planners and policymakers will need to develop meaningful adaptation strategies and mitigation options for the continued threat of sea-level rise.![]()

Dan Lowry, Ice Sheet & Climate Modeller, GNS Science; Mario Krapp, Environmental Data Scientist, GNS Science, and Nick Golledge, Professor of Glaciology, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What is COP26 and why does the fate of Earth, and Australia’s prosperity, depend on it?

In just over two weeks, more than 100 world leaders will gather in the Scottish industrial city of Glasgow for United Nations climate change negotiations known as COP26. Their task, no less, is to decide the fate of our planet.

This characterisation may sound dramatic. After all, UN climate talks are held every year, and they’re usually pretty staid affairs. But next month’s COP26 summit is, without doubt, vitally important.

In the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement, each nation pledged to ramp up their emissions reduction pledges every five years. We’ve reached that deadline – in fact, a one-year delay due to the COVID pandemic means six years have passed.

This five-yearly requirement set a framework for countries to reach net-zero emissions across the global economy by mid-century. The Glasgow summit is the first real stress test of whether the world can meet that goal.

Global Mega-Trend Toward A Clean Economy

The Paris Agreement was the world’s first truly global treaty to cut greenhouse gas emissions. It set a shared goal for countries to limit global warming to 1.5℃ above the long-term average.

The agreement has been signed and ratified by 191 of the world’s 195 countries, giving it near-universal legitimacy.

But the actual emissions-reduction commitments countries brought to Paris, known as “Nationally Determined Contributions”, left the world heading toward 3℃ of warming this century. This outcome would be cataclysmic for ecosystems and human societies.

That’s why, every five years, countries must bring progressively stronger pledges to reduce emissions.

The years since the Paris summit have seen a dramatic shift towards climate action. Today, countries representing more than two-thirds of the global economy have set a firm date for achieving net-zero emissions.

More importantly many jurisdictions – including the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, Japan and Canada – have substantially strengthened their 2030 targets. This constitutes a powerful market signal, driving a global reallocation of private and public investment from fossil fuels toward clean energy solutions.

Read more: 5 reasons why the Morrison government needs a net-zero target, not just a flimsy plan

What’s At Stake In Glasgow?

While the world is moving fast, there remains a crucial gap between current pledges and the goals of the Paris Agreement. Glasgow is seen as the last chance to close that gap and keep the 1.5℃ goal within reach.

Without stronger national commitments, we risk crossing irreversible “tipping points” in the Earth’s climate system, locking in uncontrollable global warming.

The Australian government has inched toward announcing net-zero emissions by 2050. But such a commitment will not be seen as particularly helpful in Glasgow.

Read more: The net-zero bandwagon is gathering steam, and resistant MPs are about to be run over

In reality, such announcements are merely the summit’s entry ticket. Discussions have moved on, to ensuring much deeper cuts this decade.

Barring Australia, almost all advanced economies have set new 2030 targets to slash carbon pollution. By 2030 the UK, the summit’s host nation, plans to cut emissions by 68% below 1990 levels. Meanwhile, the US will cut emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels.

The G7 countries have announced they will collectively halve emissions by 2030. There are clear expectations Australia will follow suit.

At present, Australia plans to take to Glasgow the same 2030 target it took to Paris six years ago – a 26-28% cut by 2030, from 2005 levels. Prime Minister Scott Morrison has hinted he will take an upgraded 2030 projection (rather than target), but this ruse won’t pass muster.

The Paris Agreement is about targets, and countries are required to set new targets representing “highest possible ambition”. If projections suggest we will outperform our target, a new 2030 target is clearly needed.

Global diplomatic pressure is driving a sea change in Australia’s climate politics. Just this month, the Business Council of Australia backed cuts to emissions by 46-50% by 2030. The Murdoch press has thrown its weight behind net-zero emissions. Even many conservative Nationals MPs appear to have dropped opposition to a net-zero target.

There is also dawning recognition within the Morrison government that the global energy transition is underway, and it will significantly boost Australia’s economy.

Thriving In A Net-Zero World

Australia’s economy is shaped by trends in the global marketplace. The international car market is switching rapidly to electric vehicles. And around the world, wind and solar energy are now cheaper than coal and gas.

Our export markets are changing too. As growing economies in Asia meet their climate targets, they will no longer want to buy coal and gas. Instead they’ll want renewable energy, delivered directly via undersea cable or stored as renewable hydrogen.

Such nations will still want Australian iron ore. But increasingly, they will want “green steel” made using hydrogen instead of coking coal.

Global demand for batteries, electric vehicles and renewable energy technologies will drive Australian exports of critical minerals – including lithium, cobalt and rare earths. Globally, these minerals will be worth A$17.6 trillion over the next two decades.

With the right policy settings, Australia could grow a clean export mix worth A$333 billion annually, almost triple the value of existing fossil fuel exports.

Getting to net-zero could also create 672,000 jobs, and generate A$2.1 trillion in economic activity by mid-century.

Commitments in Glasgow will spark a global race toward net-zero. But it is not a race we should be scared of. If we embrace the transition, Australia will prosper. It’s time to get started – we have a world to win.

Read more: Asia's energy pivot is a warning to Australia: clinging to coal is bad for the economy ![]()

Wesley Morgan, Researcher, Climate Council, and Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate wars, carbon taxes and toppled leaders: the 30-year history of Australia’s climate response, in brief

Kate Crowley, University of TasmaniaTime is rapidly running out for the Morrison government to announce a new climate policy before the United Nations COP26 climate talks in Glasgow next month. At the 11th hour, the government appears poised to announce a net-zero emissions target for 2050 and, possibly, stronger ambition to 2030.

Infamously, Australia has to date failed to sustain a meaningful climate policy regime. As my latest research has shown, inaction by the federal government has been a particularly effective handbrake on progress. So any new climate targets, and a robust plan to meet them, would be welcome.

The challenge now for the Morrison government is to consign Australia’s fractious climate politics divide to history. The mistakes of the past must be avoided. A new approach is needed, one that delivers on net-zero, with a 2030 target that signals Australia’s intent to join the world in taking climate change seriously.

There is much to learn from analysis of Australia’s poor record, in particular from the divisive “climate wars” which plagued federal politics over the last decade. But Australia’s policy recalcitrance stretches way back, at least 30 years.

To help us understand what’s at stake for Australia at Glasgow and beyond, here’s a quick refresher.

Cast Your Mind Back 30 Years

In her detailed history of climate awareness in Australia, academic and journalist Maria Taylor found, through document and interview-based analysis, that as far back as the late 1980s, the Australian public was the best informed on the planet of the urgent need to act on global warming.

She recalls the Hawke Labor government set a target of reducing emissions 20% below 1988 levels by 2005. However, the impetus was lost under the Keating Labor government as the economic recession hit, and concerns about the cost of climate action grew – in particular from the resources industry.

The late 1990s, under the Howard Coalition government, were also lost to inaction. At the 1997 Kyoto climate negotiations, Australia demanded a target that allowed emissions in 2012 to be 8% more than they were in 1990, while developed nations, other than Norway and Iceland, agreed to cut theirs. Australia threatened to walk away from the negotiations if that was not agreed to.

Despite Australia’s demands being met, the Howard government then failed to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, the only developed nation other than the United States to do so.

It did introduce a renewable energy target and propose a carbon tax, prior to losing the 2007 election, as an Australian public gripped by drought sought stronger action on climate change.

The Rudd Labor government ratified the Kyoto Protocol in 2007. It also attempted to set a carbon price, in the form of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CPRS). But the bill failed to pass Parliament after the Coalition and the Greens blocked it in the Senate.

In 2011, the Gillard Labor minority government passed the Clean Energy Act negotiated with her crossbench supporters. This established a carbon pricing mechanism, which critics wrongly branded a “carbon tax”.

Read more: 25 years ago the Australian government promised deep emissions cuts, and yet here we still are

The Abbott Years

The Coalition opposition, led by Tony Abbott, was circling. Ever the climate policy pugilist, Abbott pledged to “axe the tax” and repeal other climate policy advances. At the 2013 federal election, he rode those promises into office.

The Abbott government was the first in the world to repeal a carbon price. Gone also were other advances, such as the expert Climate Commission, support for wind and solar power, and policies to promote energy efficiency.

The new government’s dismantling closed Australia’s window of opportunity to act on climate change. But the world was moving on. By 2015 international leaders were calling for an end to coal and for steep policy action under the Paris Agreement.

Abbott was deposed as prime minister in 2015 after two years in office. But his dismantling efforts dramatically slowed the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy, which was progressing apace in other advanced industrial economies.

Abbott’s successor, Malcolm Turnbull, understood this. But his efforts to move on climate change were thwarted by internal party politics and dissent, and in 2018 he too was deposed.

It’s Up To Scott Morrison

Given this tumultuous history, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has been cautious not to signal abrupt climate policy change. But now, with the international summit just weeks away, he is staring down the Coalition’s naysayers in the National Party to pledge a target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

The political conversation on climate change is finally changing. Even the conservative federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg recently articulated the economic costs of not making the low-emissions transition.

But 30 years of inaction has left Australia lagging without a long-term target or an effective 2030 target to guide interim action, including a phase-out of coal. So Australia risks being left behind, missing out on the jobs and growth from a low-carbon transition.

Read more: What is COP26 and why does the fate of Earth, and Australia's prosperity, depend on it?

To see bone fide change in Australia’s climate response, the government must not repeat the mistakes of the past: politicising climate change, delaying the clean energy transition, persisting with ineffective policies, and offsetting rather than reducing emissions.

Instead, it should set partisanship aside and develop enduring economic and energy transition plans for affected communities, such as those vulnerable to drought, low-lying coastal communities, and coal workers set to lose their jobs. These plans mustn’t be reversed for political gain, as we’ve seen in the past.

Jurisdictions such as the European Union are planning or considering trade sanctions such as carbon border adjustments on nations that don’t reduce emissions. And stranded fossil fuel investments are inevitable as the market shifts towards renewables. Clearly, inaction on climate change will cost Australia dearly.![]()

Kate Crowley, Associate Professor, Public and Environmental Policy, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Yes, Australia can beat its 2030 emissions target. But the Morrison government barely lifted a finger

With just over a fortnight until world leaders gather in Glasgow at a make-or-break United Nations climate conference, all eyes are on the biggest climate laggards, including Australia.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison continues to claim Australia will “meet and beat” its current 2030 target of reducing emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels. But unlike many of his international counterparts, he has so far resisted increasing the 2030 target.

In a report released today, commissioned by the Australian Conservation Foundation, our team at Climate Analytics conclude Australia will indeed beat its current 2030 target. We project Australia’s emissions are likely to be around 30-38% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Our analysis shows almost all the emissions reductions will be the result of state government policies, and will have virtually nothing to do with the federal government. It also suggests that, given the almost total absence of substantial federal climate policies to date, Australia can do a lot more.

Crunching The Numbers

So how did we reach these figures?

First, before or by 2030, coal-fired power plants will close early. Victoria’s Yallourn plant in the LaTrobe Valley will close in 2028 and one unit at the Eraring coal plant in New South Wales will close in 2030.

These closures could bring 2030 emissions down by 1.2- 1.5% if they are replaced by renewables and storage, as appears to be the case.

The federal government, in its 2020 projections, said renewable energy will provide just over 50% of power supply nationally by 2030. Our projections show that figure to be more like 58-65%. This is due to state government action to encourage the continued record rollout of rooftop solar on homes and increase the amount of large-scale renewables entering the market.

At the state level, NSW, Victoria, the ACT and South Australia all have strong electric vehicle policies. Our analysis shows that by 2030, electric vehicles will make up 13-18.5% of light vehicles on the road.

To date, the Morrison government has no policy to promote electric vehicles, and Australia is one of only a few countries in the OECD with no emissions standards for cars.

Trends in Australia’s land use and forestry emissions are also pointing in the right direction. But the federal government projects a reduction in the carbon stored in our vegetation and forests, known as the carbon sink, compared with 2020 levels.

The federal government also assumes a continuing high level of land clearing through to 2030, which will lead to less natural carbon storage. But our work indicates land clearing rates are unlikely to be as high as the government expects. We project by 2030 the overall sink increases above 2020 levels – again, as a result of state policies, not federal.

The Federal Government Falsehood

All these reductions show state-based climate action is likely to reduce national emissions by around 28-33% by 2030, without a single move from the federal government. That’s most of the 30-38% emissions reduction we predict will occur by 2030.

The rest will come as our major trading partners tackle their domestic emissions by reducing coal and gas imports. We estimate that will lead to a reduction in Australian coal and LNG production, driving overall emissions down a further 2.6-3.4% by 2030.

The federal government’s claim it is “meeting and beating” its targets is a falsehood. It is doing little, but claiming credit from the hard work of Australia’s states and territories.

Federal policies remain firmly fixed on keeping fossil fuels in the energy mix and expanding coal and gas production. It recently approved several new coal mines and announced subsidised and expanded gas production. Gas is a fossil fuel that also needs to be phased out if we’re to have any chance of keeping warming to 1.5℃.

The Morrison government is also increasing funding for carbon capture and storage, a policy aimed at continuing the use of fossil fuels. This is despite the country’s largest such project, the Gorgon venture off Western Australia, failing to reduce and store carbon emissions at the rate originally promised.

The annual Climate Transparency analysis, released on Wednesday, shows Australia has some of the G20’s highest per capita emissions. It is the only developed country in the G20 with no price on carbon, yet ranks the fourth highest for risk of economic losses from climate impacts.

Read more: Asia's energy pivot is a warning to Australia: clinging to coal is bad for the economy

It Doesn’t Need To Be This Way

Our analysis shows that if the federal government weighed in, Australia could easily halve emissions by 2030, if not reduce them to 60%.

Our report outlines three ways the government could achieve this:

Emissions reach around 50% below 2005 levels by 2030. Decarbonisation efforts are made in the electricity, buildings and transport sectors. Under this scenario, renewables would generate 95% of the country’s electricity by 2030.

Emissions reach the same levels as the scenario above. This scenario would also involve some decarbonisation of the energy sector, but mitigation must also ramp up in agriculture, waste and industry.

Emissions reach around 60% below 2005 levels by 2030. Mitigation efforts are ramped up in Australia’s most emissions-intensive sectors - energy and industry.

Measures in these scenarios all involve:

- phasing out coal in the energy sector by 2030

- ensuring that by 2030, electric vehicles comprise 85% of all new cars sold and at least half of new trucks sold

- measure to avoid 85% of emissions in the LNG industry.

These scenarios still do not represent an emissions pathway in line with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5℃ warming limit. We also offer a 1.5℃-compatible pathway, involving domestic emissions reduction to at least 65-75% below 2005 levels by 2030, and substantial increases in international climate finance.

Our analysis from 2020 shows the large employment benefits such measures would bring just in the energy sector – many of them delivered well before before 2030. Other research into export opportunities also shows big employment benefits.

Australia is perfectly placed to capitalise on the clean, green global transition, but time is running away as other countries chase these opportunities. To drive this transformation, the federal government must set deep emissions targets for 2030, consistent with the Paris Agreement. A 50% emissions reduction by 2030 is the bare minimum needed.

Read more: What is COP26 and why does the fate of Earth, and Australia's prosperity, depend on it? ![]()

Bill Hare, Director, Climate Analytics, Adjunct Professor, Murdoch University (Perth), Visiting scientist, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Should we cull noisy miners? After decades of research, these aggressive honeyeaters are still outsmarting us

Noisy miners are familiar to many of us on Australia’s east coast as plucky grey birds relentlessly harassing other birds, dive-bombing dogs and people – even expertly opening sugar packets at your local café.

Noisy miners are native to Australia. Since colonisation their populations have boomed, and they’re now so abundant they pose a threat to other native birds in our cities, farmland and bush, such as robins, thornbills and other honeyeaters.

Culling noisy miners is often touted as a way to deal with the problem, but given the birds are native, it’s a controversial proposition. And so far, attempts to remove noisy miners have had mixed success.

To help land managers assess whether culls are likely to be effective and justified, our new research sought to understand how, and in what situations, culling helps small birds, such as the iconic superb fairy-wren, return to a site.

But what we found was unexpected, and counter-intuitive. Our results showed small birds do usually benefit from removing miners, even though neighbouring miners usually recolonise the area.

The Noisy Miner Problem

Human activity has caused many Australian species to decline dramatically, and 100 species have been listed as extinct since European colonisation. But for a very small number of species, these changes to the landscape have been beneficial. The noisy miner is one of them.

These native honeyeaters are common in dry woodland and forests, and adapt to the gardens in the cities and suburbs of eastern Australia extremely well. They thrive in habitats that are open with limited understorey, and along the edges of bigger woodland or forest patches.

As humans have altered the landscape – clearing treed landscapes, dividing it up, changing fire patterns, and grazing livestock — we have unintentionally created more and more of the noisy miners’ favourite type of habitat.

Noisy miners live in colonies as large as several hundred birds, and ferociously defend their territories, chasing and attacking intruders, no matter the species.

This aggression is so extreme, they’re one of the main contributors to the decline of dozens of native bird species of eastern Australia’s woodlands, such as regent honeyeaters, varied sittellas and diamond firetails. They’re recognised as a key threatening process under national and state environmental law.

This has had severe consequences for other Australian birds attempting to persist in such a human-altered landscape, especially birds smaller than the noisy miner. This includes a wealth of endangered birds such as brown treecreepers, speckled warblers, hooded robins and jacky winters.

In fact, research from 2012 found the density of noisy miners in an area consistently determines which bird species, and how many individuals of those species, are found there.

What Can We Do To Manage This Threat?

The threat noisy miners pose to other Australian bird life is one of our own making. It will require a commitment to multiple strategies to address it.

Planting shrubs and trees in the degraded areas that noisy miners favour is important, but it can take a long time to work, and it can be very costly.

Relocating noisy miners has also been tried, but researchers have found this is ineffective. The birds either return, are aggressively harassed by other miners in their new location, or both.

So, lethal control has been trialled as a potential alternative. Over the past three decades, scientists and land managers have removed noisy miners under permit in woodland areas, often to protect critically endangered species such as the regent honeyeater.

But Results Have Been Mixed

We looked at 45 instances of lethal control of noisy miners. In some cases, culling caused substantial reductions in the number of miners in an area, and the number of small birds increased. In others, neighbouring noisy miners rapidly recolonised the area.

For example, a 2018 study culled more than 3,000 noisy miners. And yet, researchers found the culls led to no significant reduction in the number of miners at the site, as neighbouring miners rapidly recolonised the site.

Read more: Only the lonely: an endangered bird is forgetting its song as the species dies out

Another series of noisy miner culls were conducted specifically to relieve pressure to critically endangered regent honeyeaters during their breeding season. These culls were reported as successful, and saw the broader community of songbirds increase.

To confuse things further still, even when removals were reported as “unsuccessful” in their attempts to reduce noisy miner numbers at a site, our researched revealed that the number of small birds almost always increased substantially.

This might be because the removal disrupts the social structure of the colony, causing the miners to focus on reasserting social roles rather than chasing other species. We’re not yet sure how long this relatively peaceful period lasts.

So what’s behind these counter-intuitive results? Frustratingly, there were no definitive environmental factors or methods that were more likely to result in significantly reduced noisy miner numbers, or significantly increased numbers of small birds across all the studies we looked at.

To work out what gives a removal the best chance of success, we need to collect more data and ensure all future attempts are monitored over time so we can see how long the benefits last.

Until we know more about why and when removals work, we’re limited in knowing when they should be recommended.

What If You Have Noisy Miners On Your Property?

We know noisy miners like open, grassy areas beneath eucalypts — think golf courses. So planting more shrubs and bushes to increase the complexity and diversity of native plants in your yard may help deter them, while providing new habitat for smaller birds to hide in.

Noisy miners are attracted to a variety of nectar sources too, so limit nectar-heavy species such as eucalypts and grevilleas — beautiful as they are.

Culling native species for conservation needs to be well justified - and legal. Leave lethal control to trained experts with permits; do not attempt such direct control yourself no matter how big of a nuisance they might be.

Read more: Stop the miners: you can help Australia's birds by planting native gardens ![]()

Courtney Melton, PhD Candidate in the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, and Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, The University of Queensland; April Reside, Researcher, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, The University of Queensland; Jeremy Simmonds, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Conservation Science, The University of Queensland; Martine Maron, ARC Future Fellow and Professor of Environmental Management, The University of Queensland; Michael Clarke, Emeritus professor, La Trobe University, and Paul McDonald, Associate professor, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Asia’s energy pivot is a warning to Australia: clinging to coal is bad for the economy

The COP26 climate negotiations are just weeks away, and the tide is now turning against international finance of coal-fired power generation. The implications for Australia cannot be ignored.

China, Japan and South Korea have been three of the largest public funders of overseas coal projects, pouring billions of dollars into new coal-fired power plants across the Asia-Pacific. This has enabled a wave of coal projects in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Vietnam.

But in recent months, the three funding nations have each made public statements about curtailing or ending taxpayer support for new international coal power. It follows a pledge in May this year by the G7 nations, which includes Japan, to stop financing unabated overseas coal power generation by the end of 2021.

For Australia, the writing is on the wall – the world is moving away from coal power, and we must follow suit.

Big Coal Funders

Between 2010 and 2019, Japan channelled around US$2.98 billion in overseas development finance to coal-fired generation in the Asia-Pacific.

For example, the Japan Bank for International Cooperation supported the development of Indonesia’s PLTU Tanjung Jati B power station, along with a consortuim of private lenders.

Governments that lend to overseas coal power generation projects say it helps alleviate energy poverty, or a lack of access to energy in developing nations.

Yet reaching global emissions-reduction targets partly depends on slowing the pipeline of coal power generation, including in Southeast Asia. So while investing in coal projects in developing nations might boost access to energy in the short term, the climate consequences are much worse.

What’s more, the risk these assets will become “stranded” appears not to have been systematically incorporated into project assessments in recipient countries, or by lending countries. That means the value or profitability of these assets may well plummet, especially as recipient countries implement stronger climate policies.

A second driver of overseas coal financing is to give companies from the financing country a competitive edge internationally.

State-backed financing bodies can provide direct loans, insurance and guarantees, known as export credits to foreign buyers. This can help improve the competitiveness of infrastructure exports, such as power plant technology, from companies in the financing country.

China’s aggressive use of export credits to support its companies abroad, including in the coal industry, has been one reason why countries like Japan and South Korea continued to do the same.

Read more: 5 reasons why the Morrison government needs a net-zero target, not just a flimsy plan

Leaving Coal Behind

But China, Japan and South Korea are now looking to move away from public support for financing new international coal projects.

China is the latest. Last month President Xi Jinping announced China would stop building coal-fired plants overseas, and will instead help developing countries to build low carbon energy projects. In part, the decision reflects growing international pressure for all nations to raise their climate ambitions.

The development also raises a tantalising possibility: countries like China, Japan, and South Korea may compete to finance large-scale renewable energy projects, such as offshore wind, in developing countries.

Such a development would be welcome, given the worrying signs that the deployment of renewable energy in developing countries is too slow to reach global climate targets. It would also help improve energy access in recipient countries.

What This Means For Australia

Australia is the world’s second-largest exporter of thermal coal, and China, Japan and South Korea are its top three export markets.

These three industrial powerhouses recently announced net-zero emissions targets, and Japan and South Korea have also ratcheted up their near-term ambitions for emissions reduction. This implies their imports of coal, including from Australia, have peaked.

But the move away from overseas coal financing also sends an important signal that international support for the coal power pipeline is coming to an end. Clearly, clinging to coal is now not just bad for our climate, but bad for our economy too. As our major trading partners in the Asia-Pacific move to compete in supporting the energy transition, so should we.

Australia must seize the opportunity to become a renewable energy exporter. There will be great benefits through Australia becoming a primary exporter of clean electricity, hydrogen and critical minerals to Asia and beyond.

COP26 is a chance to show the world Australia is embracing a low-emissions future. However, this will require Australia adopting a strong emissions target for 2030 and backing it up with policies for today, not for 2050.

The longer we wait, the more we will lose as other nations gain a competitive advantage in the industries, technologies, and markets that will drive a clean energy transition.

Christian Downie, Associate Professor, Australian National University and Llewelyn Hughes, Associate Professor of Public Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We can’t stabilise the climate without carbon offsets – so how do we make them work?

Carbon offsetting has been in the news lately after a report raised concerns about the integrity of the federal government’s offsetting scheme, the emissions reduction fund.

Offsetting refers to reducing emissions or removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere in one place to make up for emissions in another. Done well, it lowers the costs of reducing emissions. Done badly, it increases costs and gives us false confidence about our progress towards net zero emissions.

It’s a difficult part of the climate change conversation worldwide and, because of past problems, there’s understandable cynicism about its potential.

The Grattan Institute has just released a new report on the role of offsetting in achieving net zero targets. In it, we show even with strong policies to reduce emissions wherever possible, Australia is going to need offsetting — potentially lots of it — to reach a target of net zero emissions.

What Is Offsetting?

Offsetting is often done through a system of credits or offsets — units that represent one tonne of emissions reductions achieved, or one tonne of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere.

For example, a mining company with a net-zero target might be able to partially reduce its emissions through adjusting its operations, but could find it still has emissions that are too expensive or technically impossible to reduce.

In this case, it might buy an “offset” to cover these emissions. The offset could come from another company with plenty of options to reduce emissions (such as a landfill owner), or it might come from an activity like tree-planting.

Why Carbon Offsetting Is A Touchy Subject

Offsetting raises strong views. Some see it as an excuse for polluting companies to delay reducing emissions. Others say it destroys the fabric of rural communities because it encourages farmers to turn farming land into places for tree-planting and other carbon-storage activities.

Some international schemes have been criticised for crediting offsetting activities that aren’t “additional”. This refers to activity that would have happened anyway, such as rewarding a landholder for maintaining vegetation that was never going to be cleared, or rewarding a manufacturer for investing in low-emissions technology when that would have occurred regardless.

Australia’s emissions reduction fund has also been criticised on these grounds.

It has also been criticised for the baselines against which offsets are measured and projects receiving credit for activity that hasn’t yet occurred and may never.

Read more: Direct Action not giving us bang for our buck on climate change

All public policy that relies on incentives must grapple with the question of whether an activity is “additional”. It is a hard problem, and it may never be fully solved.

But when it comes to offsetting, it matters, because one of the roles of offsetting is to lower the cost of reducing emissions. In other words, if you can reduce your emissions more cheaply than I can using current technology, it makes sense for me to pay you to do so while I wait for technology costs to come down.

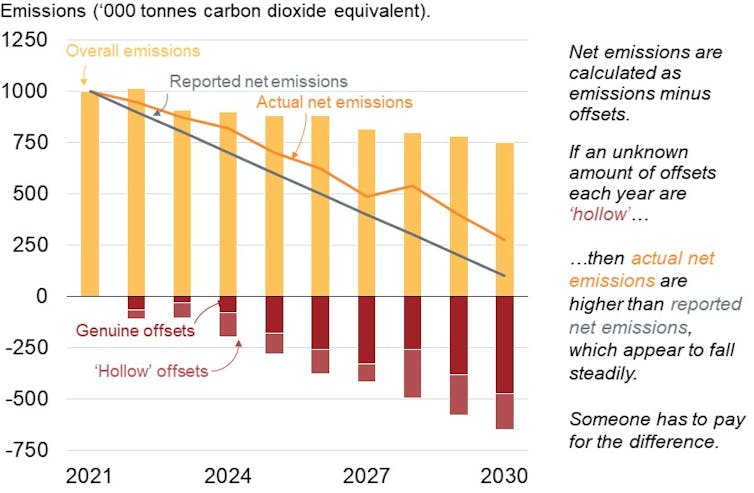

As the chart below shows, if there are too many emissions reduction or removal activities that are credited but didn’t actually happen (“hollow” offsets), then we get a false sense of progress towards net zero. Someone ends up overpaying, so the progress we do make costs more.

This limits the market’s effectiveness. If buyers aren’t sure they’re getting what they pay for, they won’t pay as much. This pushes prices down, which limits the number of producers willing to do offsetting, because they won’t be paid as much.

More profoundly, these hollow credits give a dangerous false sense of security that emissions are reducing at a particular rate, when in fact they aren’t.

Still, We Will Need More Carbon Offsets

Most offsetting in Australia is done by reducing emissions. But as we get closer to net zero, these offsetting options will disappear. There will literally be fewer emissions to reduce, and those that remain will be more difficult and more expensive to eliminate.

Read more: 5 reasons why the Morrison government needs a net-zero target, not just a flimsy plan

Even with strong policies to reach net-zero emissions in time, Australia will need offsets for hard-to-abate emissions sources, such as aviation, cement and beef cattle. The only option to deal with these emissions will be to offset them by deliberately removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Australia has plenty of land for planting trees to draw down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but we don’t have plenty of water or productive soil, and we’ll have even less as the climate warms.

Governments should invest in research and development and early-stage technology development, such as direct-air carbon capture and storage. While these technologies are very expensive and might not work at scale, it would be better to find that out now than in 2050.

Most importantly: governments should put in place stronger policies to reduce emissions. The earlier reports in the Grattan Institute’s Towards Net Zero series have recommendations for cutting emissions from transport, industry, and agriculture.

Every tonne of greenhouse gas going into the atmosphere is contributing to global warming and climate change. The tonne we don’t emit is the tonne we don’t have to offset.

Offsetting Needs Integrity

Clearly, we need offsetting to reduce emissions — but only if it’s done with integrity. In our latest report, we explain how to make this happen.

We recommend the federal government returns to its original commitment made in 2014 to review every method for creating offsetting units in the emissions reduction fund, every four years. It should allocate additional resources to do this, with independent experts.

International rules to underpin integrity and trade in offsetting units should be settled at the next month’s international conference on climate change (COP26) in Glasgow.

If negotiations drag on, we recommend the federal government put in place rules around the export of Australian offsetting units anyway, to stop potential integrity issues emerging.

Both these actions will show the government is serious about maintaining integrity in its offsetting units. Regular reviews may find problems are minimal – that would be a good outcome.

But if there’s widespread perception that offsetting is some sort of dodgy cheat, then the government will find it even more difficult to use it as a policy tool. So being transparent about problems and moving to fix them quickly is the best solution.![]()

Alison Reeve, Deputy Program Director, Energy and Climate Change, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

View from The Hill: Barnaby Joyce keeps his political hands clean on the road to net zero target

Michelle Grattan, University of CanberraThe line from Scott Morrison’s office that he’s “more likely than not” to attend what Prince Charles dubs a “last chance saloon” (Aka COP26) reflects the PM’s apparent confidence he’ll be able to secure an agreement from those pesky Nationals.

Despite there being several steps ahead to tie down that “net zero” deal, Morrison has been sounding like a man convinced he’s unstoppable.

“My government will come together on this issue,” he declared on Monday. One way or another, is the vibe.

As one Nationals source put it, either the Nationals agree, or they’ll be run over.

But “running over” the Coalition’s minor partner can be as risky as driving a car over a heap of nails. It doesn’t leave the tyres in the best of shape.

The climate policy is due to be discussed by cabinet on Wednesday, ahead of a Nationals party meeting on Sunday.

Nationals sources stress that whatever comes to the cabinet meeting is not something that is owned or authored by Joyce. At this moment there is not yet any “deal”.

The cabinet would not be making a final decision but having Joyce put something to his party, these sources say.

Victorian Nationals Darren Chester (who has been taking time out from the party room) told the ABC on Tuesday that three months ago “Barnaby Joyce said there was zero chance that the Nationals would support a net zero target – now I would say there’s about a 95% chance.

"I think there’s a lot of support and I know many colleagues in the room, who’ve spoken to me privately, [are] making the point that they understand we need a credible position on this issue,” Chester said.

“Despite all his other faults, Barnaby Joyce can count, and he can count the majority of the room is in favour of credible action on climate change.”

While Chester’s assessment of the numbers seems accurate, some Nationals are antsy.

This goes beyond the likes of Queensland senator Matt Canavan and resources minister Keith Pitt.

Canavan will never change his trenchant opposition to the net zero target. On Tuesday, appearing on Sky, he was condemning it as meaning “big government is put in charge” of individuals’ lives – what cars they drove, even what they ate.

Read more: Climate finance: rich countries aren't meeting aid targets – could legal action force them?

Pitt, who has been sceptical of a net zero commitment, faces being in an awkward position – as a minister (though not in cabinet) – if he has to sell a firm embrace of that target.

On Tuesday Pitt was visiting the Adani coal mine in Queensland.

Joyce is aware he must tread very carefully with his colleagues. While he appears to be leading his party to a place it never thought it would go, he casts himself as the follower.

Pressed on Tuesday night on whether he as Nationals leader supported a net zero by 2050 target, he resorted to a cute line, telling the ABC, “I don’t support it without the support of my colleagues”.

Read more: Politics with Michelle Grattan: A prime minister, a prince and the 'last chance saloon'.

Despite Joyce’s genuflecting to the party room, some Nationals feel they are being steamrolled, or are confused as various senior figures run positions in the media.

For example, what were they to make of the party’s Senate leader Bridget McKenzie’s opinion piece on Monday? In it she advocated a mechanism to enable Australia “to conditionally tie emissions reductions to positive regional socio-economic outcomes. If these were not being achieved, Australia would pause its climate plan rollout”.

Some Nationals wondered whether this was part of a government deal. McKenzie’s office quickly said it wasn’t Nationals policy, but insisted it was not a thought bubble either.

It’s clear a deal will be laden with sweeteners for the Nationals and protections too.

But if there are too many caveats, they will diminish the quality of the policy.

The deal the government reaches (assuming it gets there) needs to be strong enough in its ambition (including for the medium term) to be credible at Glasgow, and in the “leafy” electorates, but also able to be sold by the Nationals in their Queensland seats.

Morrison will be owning the climate part, while Joyce will be looking to the bag of benefits for the regions.

The deal has to work for both of them.

While Morrison is at the G20 and Glasgow – assuming he goes – Joyce will be acting prime minister. The last thing Morrison needs is a spooked Joyce putting his own distinctive spin on the climate policy.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The net-zero bandwagon is gathering steam, and resistant MPs are about to be run over

Prime Minister Scott Morrison appears to be moving towards securing Coalition agreement for a net-zero emissions by 2050. It comes weeks out from the crucial COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, where Australia’s record on global climate action will be heavily scrutinised.

Horse-trading between the Liberals and Nationals is under way, and the government is reportedly set to reveal its climate targets and technology roadmap early next week.

But first, Morrison must secure majority support from the National Party. A few vocal Nationals figures, including Matt Canavan, Keith Pitt and George Christensen, have sought to block or moderate a net-zero commitment.

Some of their concerns are valid – regional Australia will shoulder a big burden in the transition to a low-emissions economy. But the tides of international and domestic affairs are turning. Most government MPs have accepted the inevitable, and the issue will not break the bonds of an enduring Coalition.

Net-Zero And The Nationals

The Nationals do have legitimate economic and political reasons for being concerned about a net-zero target.

First, a move away from coal and gas would lead to job losses in regional areas. And the federal government’s policy playbook to support rural and remote areas is extremely thin, relying heavily on spillover economic benefits from agricultural development and mining.

This means the Nationals, as the self-proclaimed regional party, have few economic levers to pull. Retaining mining investment is both politically and, at regional and local scales, economically important.

Second, policy mechanisms such as a price on carbon or caps on greenhouse gas emissions could add to costs for people living in regions, and to agricultural industries such as beef production, where reducing emissions will not be straightforward or cheap.

Third, the Nationals’ opposition is somewhat in line with the party’s ideology and electoral positioning. It has historically pitched itself as a defender of national economic interests and “traditional” industries such as farming and mining.

At the same time, the party has long opposed, on economic and social grounds, post-materialist influences such as deep Green environmentalism.

Finally, the Nationals, along with the Liberals, have successfully used climate change policies to wedge the Labor Party and paint it as part of a supposed Labor-Green axis. This tactic worked well in central Queensland in the last federal election.

So for some Nats, conceding to net-zero might be seen as an ideological capitulation and yet more evidence of their ineffective efforts to stand up for the bush.

Net-Zero Gathers (Renewable) Steam

The problem for the Nationals resistance movement, however, is that it’s becoming increasingly isolated.

Both the Biden administration in Washington and the United Kingdom government are pressuring Australia to commit to the 2050 net-zero target.

And several jurisdictions, such as the European Union, are considering or planning carbon tariffs on imports from nations without strong climate policies.

In the context of recent shifts in the international policy landscape, railing against such tariffs looks anachronistic.

As National Farmers’ Federation (NFF) chief executive Tony Mahar said earlier this year, “as an industry dependent on exporting, Australian agriculture must be ready to adjust to a more carbon-conscious trading future”.

Domestically, state governments, including those with Coalition incumbents, have shifted to net-zero-type targets. So too have important lobby groups, such as the NFF and the Business Council of Australia.

Meanwhile, moderates in the federal Liberal Party are gearing up to argue for a net-zero plan and against large compensation for particular industries.

All this leaves the Nationals’ resistance movement rather short of influential allies.

Opponents could, of course, roll out the implied threat of breaking the Coalition. But moderate Nationals have hosed down suggestions a net-zero target is a make-or-break issue for the Coalition partners. And historically, Coalition breaks – especially in government – are extremely rare.

Read more: 5 reasons why the Morrison government needs a net-zero target, not just a flimsy plan

Sealing The Deal

Nonetheless, even Nationals in favour of a net-zero target want assurances for the regions and agricultural industries.

An obvious and relatively easy policy response is to ensure new renewable energy projects in the regions deliver local economic benefits, such as through favourable purchasing and employment strategies or even dividend sharing.

Second is to ensure these and other projects continue to drive down electricity costs. This is especially important for energy-intensive agricultural production such as irrigated crop and pasture production. Where possible, regional landholders could receive income from local energy ventures as hosts of, or even partners in, projects.

Third, funding for land-based carbon storage could be expanded.

Australian landholders have made a huge contribution to national emissions offsets over decades, largely through vegetation management which draws carbon from the atmosphere and stores it in plants and soil. Such management has largely been the result of state government regulation preventing land clearing and farmers have historically received little direct benefit in return.

The federal government is now contributing funding for landholders who create land-based carbon sinks under the Emissions Reduction Fund. But the resulting projects have caused local concerns and the carbon storage outcomes are uncertain.

So expanding such schemes will not be easy. It must be done in a way that meets integrity standards, and without alienating local people.

The Morrison government is understandably averse to direct carbon pricing, given the toxic climate politics of the last decade. It’s instead focused on low-emissions technological solutions.

This might lead to new low-emisisons technologies for the regions, such as conversion to renewable energy and innovative transport systems. But there’s no timeline yet for when such technology will materialise.

The Nationals are right to demand detail in the climate policy deal. But the net-zero bandwagon cannot be stopped – at best, the Nationals must settle for perhaps quite modest compensation for their constituents.

Read more: Australia could 'green' its degraded landscapes for just 6% of what we spend on defence ![]()

Geoff Cockfield, Honorary Professor in Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham's Beach

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve