inbox and environment news: Issue 515

October 24 - 30, 2021: Issue 515

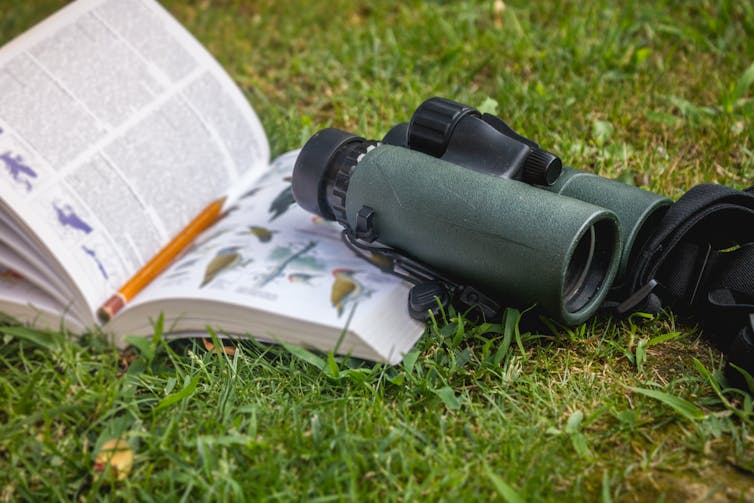

Aussie Backyard Bird Count 2021

The 2021 event will run from October 18‒24 during National Bird Week. Register as a counter today at: https://aussiebirdcount.org.au/

The Aussie Backyard Bird Count is one of Australia’s biggest citizen science events. This year is our eighth count, and we’re hoping it will be our biggest yet!

Join thousands of people around the country in exploring your backyard, local park or favourite outdoor space and help us learn more about the birds that live where people live.

Taking part in the Aussie Backyard Bird Count is a great way to connect with the birds in your backyard, no matter where your backyard happens to be. You can count in a suburban garden, a local park, a patch of forest, down by the beach, or the main street of town.

To take part, register on the website today, then during the count you can use the web form or the app to submit your counts. Just enter your location and get counting ‒ each count takes just 20 minutes!

Not only will you be contributing to BirdLife Australia's knowledge of Aussie birds, but there are also some incredible prizes on offer.

Head over to the Aussie Backyard Bird Count website to find out more.

Echidna At Mona Vale

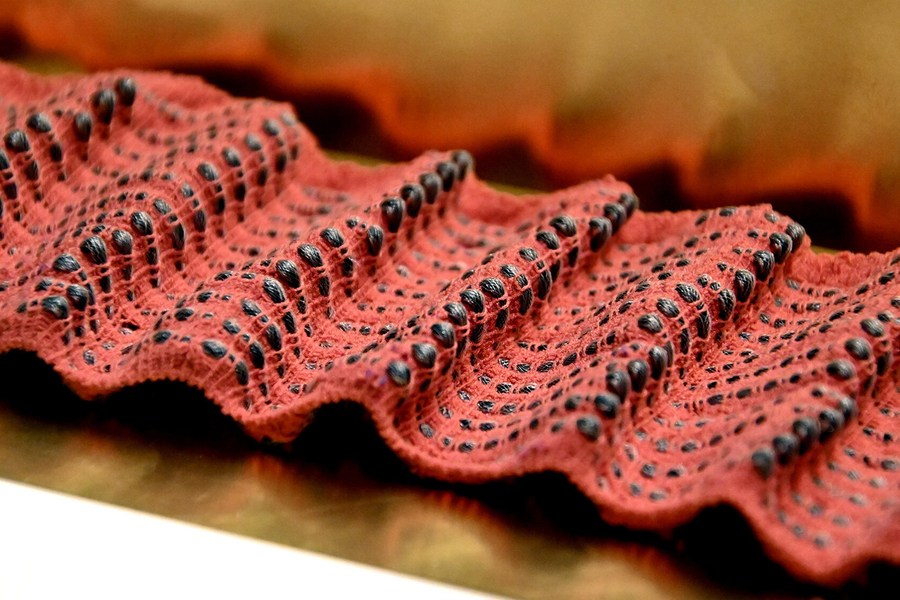

Cicada Shell

The Flannel Flower: Australia’s Symbol For Mental Health Awareness During Mental Health Month - October

Tuckeroo Becoming Troublesome In Pittwater

Waratahs: Look But Don't Steal

Birds In Your Garden: Wish You Had More?

Avalon Preservation Association AGM 2021

Speaker: Angus Gordon OAM

“Global warming, is it real?”

The 2021 Annual General Meeting for Avalon Preservation Association (APA) will be held from 7.00pm on Thursday 11 November 2021 at the Avalon Beach surf life saving club.

Our special guest speaker is Angus Gordon OAM. Angus will talk on the controversial and very timely topic “Global Warming, Is it Real?”

Angus was General Manager of Pittwater Council from 1996 to 2005. He has a Master’s degree in Water and Coastal Engineering. In 2018 Angus received the Medal of the Order of Australia for “service to environmental management and planning, and to the community”.

Over the past 40 years he has undertaken projects in all states of Australia and in a number of overseas countries in coastal engineering, coastal zone management and flood management and engineering. Angus has served as a UN expert and was tasked with the development of the NSW Coastal Protection Act.

Angus Gordon OAM. AJG pic.

Speaker: Angus Gordon OAM

“Global warming, is it real?”

The 2021 Annual General Meeting for Avalon Preservation Association (APA) will be held from 7.00pm on Thursday 11 November 2021 at the Avalon Beach surf life saving club.

Our special guest speaker is Angus Gordon OAM. Angus will talk on the controversial and very timely topic “Global Warming, Is it Real?”

Angus was General Manager of Pittwater Council from 1996 to 2005. He has a Master’s degree in Water and Coastal Engineering. In 2018 Angus received the Medal of the Order of Australia for “service to environmental management and planning, and to the community”.

Over the past 40 years he has undertaken projects in all states of Australia and in a number of overseas countries in coastal engineering, coastal zone management and flood management and engineering. Angus has served as a UN expert and was tasked with the development of the NSW Coastal Protection Act.

Due to the current health situation, APA will hold the AGM strictly in line with the NSW Public Health Orders in force at the time. This may restrict the number of members and guests able to attend and guests may need to check in with a QR code, wear facemasks and show that they have been fully vaccinated.

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

Broken Offsets System Driving Species To Extinction

Consultations Open On National Reforms To Support Clean Hydrogen And Biogas Blending

Greater Sydney Water Strategy Open For Feedback

- Improving water recycling, leakage management and water efficiency programs, which could result in water savings of up to 49 gigalitres a year by 2040.

- Extending a water savings program, which has been piloted in over 1000 households and delivered around 20 per cent reduction in water use per household and almost $190 in savings per year for household water bills.

- Consideration of running the Sydney Desalination Plant full-time to add an extra 20 gigalitres of water per year.

- Expanding or building new desalination plants to be less dependent on rainfall.

- Investigating innovations in recycled water to improve sustainability.

- Making greater use of stormwater and recycled water to cool and green the city and support recreational activities.

Warragamba Dam Raising Project EIS On Public Exhibition

NSW Government Plan To Revitalise Peat Island And Mooney Mooney Released

- Nearly 270 new homes at Mooney Mooney to deliver more housing supply,

- Retention of nine unlisted historical buildings on the island, and four on the mainland, to be restored and used for new community and commercial opportunities,

- New retail and café or restaurant opportunities,

- Approximately 9.65 hectares of open space, including opportunities for walking and cycling tracks, parklands and recreational facilities,

- Retention of the chapel and surrounding land for community use, and

- 10.4 hectares of bushland dedicated as a conservation area.

Government Supporting Australia's Biggest Electric Bus Fleet

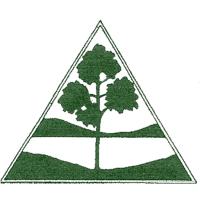

Australia's 100 Priority Species

Major Food Businesses Sign Up To Halve Food Waste In Australia

- Simplot Australia

- Woolworths Group

- Coles

- Mars Australia

- Mondelēz Australia

- Goodman Fielder

- ARECO Pacific

- McCain Foods

Australia ranks last out of 54 nations on its strategy to cope with climate change. The Glasgow summit is a chance to protect us all

The need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is widely discussed, but the other side of climate action is less often talked about: adapting to impacts already locked in. Even if we drastically reduce emissions, the cost of natural disasters in Australia will reach an estimated A$73 billion per year by 2060.

Intense heatwaves are Australia’s deadliest natural hazards. In the summer of 2019-2020, unprecedented bushfires devastated Australia’s southeast, and changes in seasonal conditions over the past two decades has seen average farm profits fall by 23%.

The Morrison government is developing a new National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy, to be released ahead of the United Nations climate change conference in Glasgow next month.

The strategy must ensure Australia does better to manage climate damage already happening, as well as prepare for future disasters. Australia once led the world in climate adaptation, but efforts have fallen by the wayside over the past decade or so. The longer we fail to act, the greater the costs and difficulty we will face.

Australia Was Once A Global Leader

According to the United Nations, adaptation refers to any change to processes, practices and structures in response to the climate change threat.

It can include anything from building flood defences, setting up early warning systems for cyclones and switching to drought-resistant crops, to redesigning communication systems, business operations and government policies.

In 2007, the newly elected Rudd government recognised the need for Australia to adapt to the climate changes ahead. For example, it established a federal Department of Climate Change and Water inside the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio, to coordinate emissions reduction, climate adaptation and international efforts.

Australia was one of the first countries to invest millions in adaptation, including establishing the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility in 2008.

But the growing politicisation of climate action over subsequent years meant funding waned at the federal level, and Australia’s national adaptation efforts slowly deteriorated.

The Abbott government dissolved the Department of Climate Change in 2013. Today, responsibility for emissions reduction, adaptation and climate diplomacy is split across various government departments.

Historically, Australia has chronically underinvested in disaster prevention. In 2014, the Productivity Commission examined the federal government’s initiative to provide disaster relief and recovery payments and found only 3 cents in every dollar are spent on mitigating risks, while 97 cents are spent on clean-up and recovery.

The absence of an overarching adaptation plan can lead to ad hoc, counter-productive policies. For example, the federal government recently announced a A$10 billion insurance guarantee in Northern Australia to protect residents from cyclone and flood damage. But this risks backing in residents to remain in disaster-prone areas.

Australia has also never conducted a national climate risk assessment. This leads to confusion at the local government level, especially around sea level rise. For example, in 2019 Shoalhaven city council in New South Wales reportedly voted to plan for unrealistically optimistic sea level rise projections that cannot be reached under current emissions scenarios.

Looking Ahead To COP26

This fragmented approach to climate policy has seen Australia fall behind other nations on climate action and resilience.

Under the Paris Agreement, each nation should have a National Adaptation Plan to sufficiently prepare for and manage climate change impacts. While at least 106 other countries have such policies and plans for adaptation, Australia does not.

Instead, we have the National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy. Unlike National Adaptation Plans abroad, this strategy lacks enforceable targets or policies. As such, it was ranked last out of 54 comparable strategies in a 2019 study.

Read more: Who's who in Glasgow: 5 countries that could make or break the planet's future under climate change

An updated strategy will be released prior to or at the Glasgow summit. The government says it will support governments, communities and businesses to better adapt to the physical impacts of climate change.

Australia needs a long-term and proactive approach to climate resilience, and the updated national strategy should commit to spending as much on prevention as it does on recovery. Important proactive measures include:

greater funding for First Nations cool burning programs to prevent catastrophic bushfires

more green spaces in urban centres to mitigate urban heat

partnerships with insurance providers to evaluate projected costs of climate risks and adaptation for all new infrastructure decisions.

The recent 2019-2020 bushfires were a brutal reminder of the need to adapt to climate change. In response to a recommendation by the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, the Morrison government established the National Recovery and Resilience Agency in May this year.

It includes A$600 million toward communities to help them prepare for future disasters. But as other experts have noted, the investment pales in comparison to the billions of dollars lost through disasters, and must become core funding.

Others have also questioned how the new agency will coordinate with the Emergency Management Australia and state recovery agencies, and how the agency’s success will be measured.

On top of business-as-usual management, climate change adaptation requires understanding how the disasters and other impacts will worsen in future, and how we can start preparing.

Preventative measures give you the most bang for your buck. Some studies estimate every dollar spent on disaster prevention saves as much as A$15 in recovery efforts.

It’s Not Too Late

The window of opportunity is still open to urgently reduce global emissions and help communities respond to the unfolding climate crisis.

The federal government must reinvest in climate adaptation science, carry out risk assessments and roll out policies that protect us from floods, fires, drought and increasing temperatures.

The Glasgow summit is shaping as a strong catalyst for more action on adaptation. For the first time, countries will submit “Adaptation Communications” that outline their progress, and these will be updated and assessed by the United Nations every five years.

Collectively, they’ll help track global progress on adaptation measures and investments, to ensure no country gets left behind.![]()

Johanna Nalau, Research Fellow, Climate Adaptation, Griffith University and Hannah Melville-Rea, Research fellow, New York University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

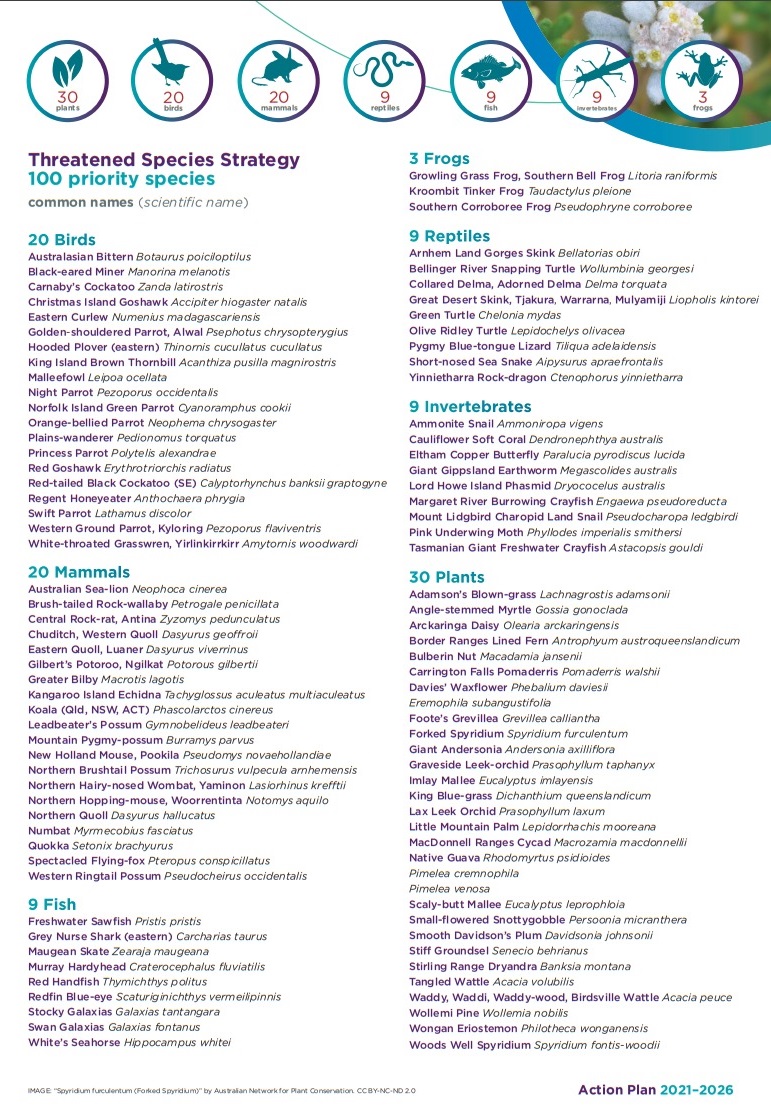

Widespread collapse of West Antarctica’s ice sheet is avoidable if we keep global warming below 2℃

Rising seas are already making storm damage more costly, adding to the impact on about 700 million people who live in low-lying coastal areas at risk of flooding.

Scientists expect sea-level rise will exacerbate the damage from storm surges and coastal floods during the coming decades. But predicting just how much and how fast the seas will rise this century is difficult, mainly because of uncertainties about how Antarctica’s ice sheet will behave.

The recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projections of Antarctica’s contribution to sea-level rise show considerable overlap between low and high-emissions scenarios.

But in our new research, we show the widespread collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is avoidable if we can keep global warming below the Paris target of 2℃.

In West Antarctica, the interior of the ice sheet sits atop bedrock that lies well below sea level. As the Southern Ocean warms, scientists are concerned the ice sheet will continue to retreat, potentially raising sea level by several meters.

When and how quickly this process could happen depends on a number of factors that are still uncertain.

Our research better quantifies these uncertainties and shows the full impact of different emissions trajectories on Antarctica may not become clear until after 2100. But the consequences of decisions we make this decade will be felt for centuries.

A New Approach To Projecting Change In Antarctica

Scientists have used numerical ice-sheet models for decades to understand how ice sheets evolve under different climate states. These models are based on mathematical equations that represent how ice sheets flow.

But despite advances in mapping the bed topography beneath the ice, significant uncertainty remains in terms of the internal ice structure and conditions of the bedrock and sediment below. Both affect ice flow.

This makes prediction difficult, because the models have to rely on a series of assumptions, which affect how sensitive a modelled ice sheet is to a changing climate. Given the number and complexity of the equations, running ice-sheet models can be time consuming, and it may be impossible to fully account for all of the uncertainty.

To overcome this limitation, researchers around the world are now frequently using statistical “emulators”. These mathematical models can be trained using results from more complex ice-sheet models and then used to run thousands of alternative scenarios.

Using hundreds of ice-sheet model simulations as training data, we developed such an emulator to project Antarctica’s sea-level contribution under a wide range of emissions scenarios. We then ran tens of thousands of statistical emulations to better quantify the uncertainties in the ice sheet’s response to warming.

Low Emissions Prevent Ice Shelf Thinning

To ensure our projections are realistic, we discounted any simulation that did not fit with satellite observations of Antarctic ice loss over the last four decades.

We considered a low-emissions scenario, in which global carbon emissions were reduced quickly over the next few decades, and a high-emissions scenario, in which emissions kept increasing to the end of the century. Under both scenarios, we observed continued ice loss in areas already losing ice mass, such as the Amundsen Sea region of West Antarctica.

For the ice sheet as a whole, we found no statistically significant difference between the ranges of plausible contributions to sea-level rise in the two emissions scenarios until the year 2116. However, the rate of sea-level rise towards the end of this century under high emissions was double that of the low-emissions scenario.

By 2300, under high emissions, the Antarctic ice sheet contributed more than 1.5m more to global sea level than in the low-emissions scenario. This is because the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapses.

The earliest warning sign of a future with a multi-metre Antarctic contribution to sea-level rise is widespread thinning of Antarctica’s two largest floating ice shelves, the Ross and Ronne-Filchner.

Read more: Antarctica's ice shelves are trembling as global temperatures rise – what happens next is up to us

These massive ice shelves hold back land-based ice, but as they thin and break off, this resistance weakens. The land-based ice flows more easily into the ocean, raising sea level.

In the high-emissions scenario, this widespread ice-shelf thinning happens within the next few decades. But importantly, these ice shelves show no thinning in a low-emissions scenario — most of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet remains intact.

Planning Our Future

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep warming well below 2℃. But current global government pledges commit us to 2.9℃ by 2100. Based on our emulator projections, we believe these pledges would lead to a 50% higher (70cm) Antarctic contribution to sea-level rise by the year 2300 than if warming remains at or under 2℃.

But even if we meet the Paris target, we are already committed to sea-level rise from the Antarctic ice sheet, as well as from Greenland and mountain glaciers around the world for centuries or millennia to come.

Continued warming will also raise sea levels because warmer ocean water expands and the amount of water stored on land (in soil, aquifers, wetlands, lakes, and reservoirs) changes.

To avoid the worst impacts on coastal communities around the world, planners and policymakers will need to develop meaningful adaptation strategies and mitigation options for the continued threat of sea-level rise.![]()

Dan Lowry, Ice Sheet & Climate Modeller, GNS Science; Mario Krapp, Environmental Data Scientist, GNS Science, and Nick Golledge, Professor of Glaciology, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia is undermining the Paris Agreement, no matter what Morrison says – we need new laws to stop this

Peter Christoff, The University of MelbournePrime Minister Scott Morrison is poised to take a 2050 net-zero emissions target to Glasgow. While this may seem like a milestone, Australia is still failing to abide by one of the core requirements of the Paris Agreement.

At Paris in 2015, Australia – like the rest of the world – signed up to toughening our emissions reduction targets every five years. We’ve now reached that point (factoring in a one-year COVID delay).

Yet Australia’s current 2030 targets remain no more ambitious than those we produced six years ago, and Morrison has all but ruled out increasing them ahead of the Glasgow summit.

This means Australia is undermining the international treaty central to combating climate change – and highlights yet again the need for Australia’s climate agreements to be written into domestic law.

What Is The Paris Agreement?

The 2015 Paris Agreement is a curious instrument, allowing countries to nominate their own emissions-reduction targets and related actions. This discretionary arrangement was the only option to ensure support and compliance by individual states, especially the United States and China.

In 2015, Australia’s first target was to reduce emissions by 26–28% below 2005 levels by 2030. It was well below the 45–65% reduction recommended by Australia’s Climate Change Authority.

In combination, the first emissions-reduction pledges made by the 195 signatories to the Paris Agreement was insufficient. They put the world on track for global warming of at least 3.5℃ above pre-industrial levels this century – far higher than the Paris Agreement goals of limiting warming to 2℃, while aiming for no more than 1.5℃ .

So the Agreement also requires nations to amend their targets every five years. These amendments are required to “represent a progression” beyond the last plan and “reflect a country’s highest possible ambition”.

Specifically, each country with a 2030 target – such as Australia – is expected to update its contribution by 2020 (a deadline pushed out by COVID to 2021).

Read more: What is COP26 and why does the fate of Earth, and Australia's prosperity, depend on it?

Breaking Our Legal Obligations

A fundamental principle of international law – and arguably the oldest – is “pacta sunt servanda”, which means “agreements must be kept”. It is essential to the functioning of the global treaty system.

Although the Paris Agreement does not include enforcement mechanisms, it is nonetheless a legally binding treaty and so, according to the “pacta sunt servanda” principle, must be implemented in good faith.

In practice, major developed countries have shown they understand “updating” to refer to toughening short-term targets, separate from a commitment to the longer term aim of net-zero by 2050.

For example, in December 2020 the United Kingdom lifted its 2030 target from 57% to 68% below 1990 levels. Germany has increased its target from 55% to 65% below 1990 levels. The United States will now aim for a 50-52% reduction below 2005 levels by 2030.

Australia, on the other hand, has not budged on its short-term ambition. Its 2020 formal communication to the United Nations lists a raft of policy initiatives. But there is no change to its old 2030 target.

This failure builds on Coalition’s record of undermining international climate agreements, stretching back to 1997 when the Howard government first negotiated extraordinarily favourable emissions targets but ultimately refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol.

Howard’s recalcitrance contributed to an eight-year delay before the protocol came into legal force, and slowed global efforts to reduce emissions. Australia finally ratified the Protocol in 2007, under the Rudd government.

Morrison adds to this record as he continues to dither. His failure is puzzling, given the absence of threats to his prime ministership, and the clear support for tougher emissions targets from business, farmers and in crucial rural seats.

What’s more, Australia is actually already tracking towards emissions reductions of 30-38% below 2005 levels by 2030.

National Climate Target Law

So how can we ensure Australia abides by international laws, both in terms of the letter and the spirit?

Under our Constitution, unless the substance of an international treaty signed by Australia is also enacted in Australian law, that treaty has no legal hold over domestic behaviour.

No federal government – Coalition or Labor – has embedded Australia’s emissions-reduction targets in law. Most recently, in 2018, then-Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull sought to do so as part of the proposed National Energy Guarantee. Internal party tensions forced him to dump that legislative plan – but not soon enough to prevent him being dropped as leader.

Those times have passed; parliamentary support for climate action is now overwhelming.

The absence of legislative teeth means no one can be held accountable if Australia misses its emissions goals. That means the Morrison government has been able to approve new coal mines and subsidise coal-fired power generation and gas expansion without fear of punishment or redress.

By contrast, many other countries - for instance, the UK, Austria, Denmark and Scotland - have established effective national climate laws, setting long-term and interim targets with associated mechanisms for reviewing and requiring progress.

Many include mechanisms for systematic review and are regularly amended to bring them into line with the targets and other provisions of the Paris Agreement.

The recognised gold standard for such climate legislation is the UK Climate Change Act 2008, which includes:

- interim and final targets, and related implementation mechanisms

- an independent committee with science-informed processes for reviewing progress

- mechanisms for setting and regularly increasing ambition over time

- parliamentary accountability mechanisms and the basis for whole-of-government planning and coordination.

Four Australian states and territories – Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and the ACT - have developed similar tough framework legislation. Indeed, recent research shows we were once global leaders: South Australia was the first jurisdiction in the world to enact such a law.

Overcoming Past Failures

Without a stringent and binding plan to minimise national emissions in the short term, a 2050 net-zero target is vacuous.

Without a national climate law, the problems of the past will persist. National policies and effort will remain uncoordinated, investors will face continued uncertainty and economic opportunities will continue to be lost.

If Australia is really serious about climate action, Morrison must announce a new, tougher 2030 goal and enshrine it in law. This law must also include clear processes for coordinating, reviewing and enhancing national climate action.

The urgency and scale of the climate crisis demands it.![]()

Peter Christoff, Senior Research Fellow and Associate Professor, Melbourne Climate Futures initiative, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

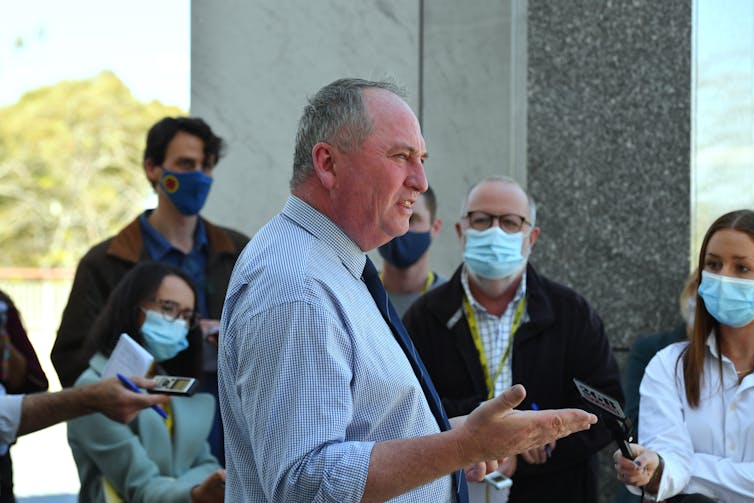

Barnaby Joyce has refused to support doubling Australia’s 2030 emissions reduction targets – but we could get there so cheaply and easily

As Prime Minister Scott Morrison tries to land a Coalition climate policy deal ahead of the international COP26 summit in Glasgow, Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce on Sunday ruled out supporting more ambitious 2030 targets.

The current 2030 target aims to cut emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels, and has been criticised by scientists and the international community as far too weak.

But ahead of a Nationals party room meeting on Sunday to discuss changes to national climate policy, Joyce declared it “highly unlikely” he would support a doubling of the 2030 target, according to ABC reports.

If Australia was to adopt the bolder target, it would bring us in line with our key ally and trading partner, the United States, and would be broadly in line with the targets of other allies, the European Union and the United Kingdom. It would see Australia become a valued and relevant party to the negotiations at Glasgow, rather than a resented freeloader.

As a professor of engineering and an author of many research papers considering what’s needed to reach 100% renewable energy, I believe Australia could halve its 2030 emissions with minimal cost and inconvenience. Here’s how it could be done.

By The Megatonnes

The top three sources of Australia’s emissions are electricity (34%), heating from burning fossil fuels in homes and factories (20%), and transport (18%).

Australia’s emissions baseline year is 2005, when the total emissions were 612 million tonnes (megatonnes) of carbon dioxide equivalent.

By 2020, emissions had fallen to 498 megatonnes, mostly because the rates of land clearing, another big source of emissions, are much lower now than in 2005.

This puts us well on track to meet and beat Australia’s current 2030 target, which equates to about 453 megatonnes. We will easily reach this soft target by continuing to displace coal generation of electricity with solar and wind at the current rate of 7 gigawatts per year, provided we avoid new sources of emissions.

Earlier this year, United States President Joe Biden announced his commitment to reduce US emissions 50-52% by 2030.

Australia should offer to match this at the Glasgow summit. Cutting, say, 51% of Australia’s 2005 levels would bring Australia’s emissions down to just 300 megatonnes in 2030.

OK, So How Do We Do It?

The task of reaching 300 megatonnes in 2030 is straightforward, and with around zero net cost. It would see:

90% of electricity generation coming from solar, wind and hydro in 2030 (three-quarters of the task)

90% of new sales of vehicles and heating equipment be electric from 2027 (one-quarter of the task)

no new emissions sources. For example, encouraging fossil gas companies to frack large new areas makes the task more onerous because of methane leakage.

Let’s look at transport first. Curtailing sales of petrol vehicles with a combination of incentives and regulation would see nearly all vehicles become electric by the mid-2030s, as old cars retire.

While the federal government has been famously unenthusiastic about electric vehicles, states and territories are already offering modest incentives.

Read more: Up to 90% of electricity from solar and wind the cheapest option by 2030: CSIRO analysis

The bulk of emissions cuts will come from the electricity sector, because the cost of solar and wind technology has fallen below coal and gas.

As of this month, Australia’s National Electricity Market derives 36% of its electricity demand from renewables (mostly solar and wind), and is tracking towards 50% in 2025. Coal burning makes up 60%, but is falling quickly because of growing competition from solar and wind. Gas generation has fallen to just 4%.

The wholesale market price has also fallen sharply from 2020, as a flood of new solar and wind farms entered the market. This means the faster we deploy solar and wind, the lower electricity prices will be and the faster we reduce emissions.

The biggest impediment to rapid deployment of solar and wind is a lack of new transmission cables to bring new solar and wind power from the regions to the cities. The government needs to facilitate a national transmission network to get rid of congestion when transmitting renewable electricity — then stand back as solar and wind farm companies rush to utilise it.

Australia’s Natural Advantage

Not only is the market for renewable energy dramatically improving, Australia also has a natural advantage. Compared with most other developed nations, Australia has excellent solar and wind resources where most people actually live, near the sea.

Australia also has a big head start on installing rooftop solar, solar farms and windfarms, helped along by strong Australian-developed solar technology and political support between 2007 and 2013.

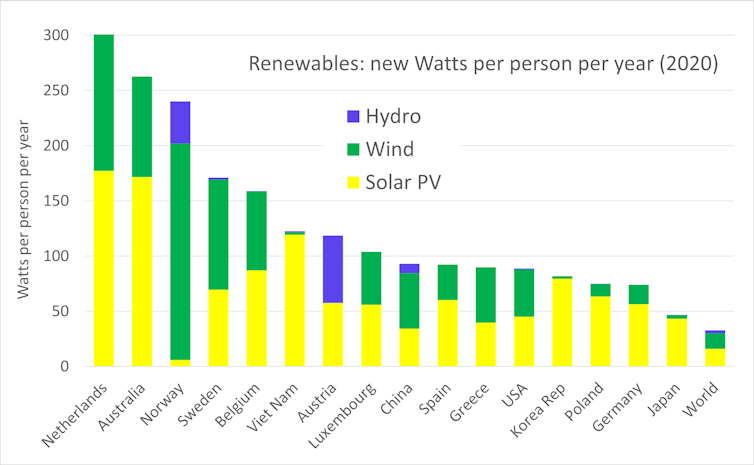

In fact, in 2020 Australia was among the top three global leaders in deploying new renewable energy capacity, alongside the Netherlands and Norway, as the chart below shows. These three nations deployed new renewables per capita at 10 times the global rate, and between three and five times faster than China, Japan, Europe and the USA.

The fastest change in global energy systems in history is underway. Due to their their compelling economic advantage, solar and wind provided three-quarters of new electricity generating capacity worldwide, and 99% of new capacity in Australia, in 2020.

Cutting Further To 100 Megatonnes

Reducing emissions to 300 megatonnes in 2030 would place Australia on track to just 100 megatonnes sometime in the 2030s, at low cost. We’d eventually see emissions fully removed from electricity, land transport and heating as, for example, electric vehicles replace retiring older cars and retiring gas heaters are replaced.

It’s also important to note that every year, coal and gas mining releases around 50 megatonnes of “fugitive” methane emissions — leaks from coal mining and gas fracking. But this, too, will vanish in Australia when other countries stop buying Australian coal and gas. Presumably, this will be before 2050 as other countries make good on their promises to decarbonise.

The technology we need to reach 100 megatonnes of emissions is already available at low cost from vast production runs: solar, wind, energy storage (via pumped hydro and batteries), transmission cables, electric vehicles, heat pumps and electric furnaces. Continued research and development will make these costs even lower.

So What’s Left Over To Get To Net-Zero?

Remaining emissions come from aviation, shipping, industry (cement, chemicals, metals), land clearing and agriculture. These sectors need plenty of research and industrial development to decarbonise, but we have time to do this over the next decade if we halve emissions by 2030.

Given Australia has plenty of land, good wind and much better solar than its rivals, it would be unconscionable for Australia to have a softer emissions target than the US, UK and EU at the Glasgow.

We don’t need new taxes, nor hydrogen, nor carbon capture and storage, nor a “gas-led recovery”. But we do need the federal government to either get involved or get out of the way.

Andrew Blakers, Professor of Engineering, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Millions of people were evacuated during disasters last year – another rising cost of climate change

As world leaders prepare for the COP26 climate talks next month, it’s worth recalling a sobering line from the royal commission’s report into the 2019-20 Australian bushfires: “what was unprecedented is now our future”.

The bushfires saw the largest peacetime evacuation of Australians from their homes, with at least 65,000 people displaced. As climate change amplifies the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, evacuations are likely to become increasingly common – and costly – in human and economic terms.

Numbers Of Displaced People On The Rise

Globally, the displacement of people due to the impacts of disasters and climate change is now at a record high.

In 2020, nearly 31 million people were displaced within their own countries because of disasters, at least a third of which resulted from government-led evacuations. And people in poorer countries are six times more likely to be evacuated than those in wealthier countries, according to some estimates.

Already, close to 90% of the world’s refugees come from countries that are the most affected by climate change – and the least able to adapt.

Evacuations are an important life-saving emergency response – a temporary measure to move people to safety in the face of imminent harm. Under human rights law, states are obligated to protect people from threats to life, including the adverse effects of disasters and climate change.

At times, this may include an obligation to evacuate people at risk.

However, without careful planning and oversight, evacuations can also constitute arbitrary displacement. They can uproot “significant numbers” of people for prolonged periods of time. And they can expose people to other types of risks and vulnerabilities, and erode human rights.

For example, in 2020, wildfires and flooding exacerbated the existing humanitarian crisis in Syria, prompting the evacuation of thousands of already internally displaced persons who were forced to move yet again.

Too Little Support After Disasters

Unfortunately, the “rescue” paradigm that characterises the way we typically think about evacuations means such risks are too often overlooked. As a result, national responses may fail to appreciate the scale of internal displacement triggered by evacuations, or to identify it at all.

In practice, this may mean there is insufficient support for those who are displaced, and little accountability by the relevant government authorities. Moving people out of harm’s way during a disaster may be one element of an effective government response. Ensuring people can return, safely and with dignity, however, is crucial to economic and social recovery.

Read more: In the face of chaos, why are we so nonchalant about climate change?

This is particularly prescient given that evacuations can create significant economic and social disruption.

For instance, the cost of a year’s temporary housing for Australia’s 2019–20 bushfire evacuees amounted to A$60–72 million. Each day of lost work cost A$705 per person.

Such costs are amplified in the Asia-Pacific region, which accounted for 80% of global disaster-related displacement from 2008–18.

Small island states are particularly affected by disasters and the impacts of climate change. For instance, large proportions of Vanuatu’s population were displaced by Cyclone Pam in 2015 and by Cyclone Harold just five years later.

According to a UN forecast, such countries could face average annual disaster-related losses equivalent to nearly 4% of their GDPs. The impact on the long-term prosperity, stability and security of individuals and communities cannot be overstated.

The point is that with greater investment in disaster risk reduction and planning, many of these outcomes could be avoided.

Currently, the amount of money allocated in development assistance to prepare for disaster risks is “miniscule” compared to aid funding for post-disaster responses.

This is clearly is the wrong way around – especially when the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction estimates each dollar spent on preparation could have a 60-fold return.

What Leaders At COP26 Need To Do

The ABC television’s miniseries Fires shows that people’s decisions about whether to stay or go in an emergency are not simple. People are influenced not only by their perceptions of the risk of harm, but also by the desire to protect relatives, property and animals, or a belief that they can withstand the disaster.

Well-planned, evidence-based strategies are important when an emergency requires rapid decision-making, often in changing conditions and with limited resources to hand. If lines of authority are unclear, or there is insufficient attention to detail during the planning process, evacuation efforts may be hampered further, putting lives and property at greater risk.

Read more: Rising seas will displace millions of people – and Australia must be ready

It is essential for policymakers to recognise that a government’s “life-saving” response to a disaster, such as an evacuation, can itself generate significant human and financial costs. Governments need to incorporate principles from human rights law into their response plans to help protect people from foreseeable risks and to enhance their rights, well-being and recovery.

Climate change is only going to exacerbate increasingly extreme weather events that force people from their homes. At next month’s climate talks, leaders must agree on climate change mitigation targets and adaptation policies that avert the need to evacuate people in the first place.

However, achieving change on the ground will require a far more linked-up and integrated approach to climate change, disaster risk reduction, sustainable development and mobility. This includes systematically implementing the recommendations not only of the Paris Agreement, but other international agreements focused on these goals.

The Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law at UNSW is holding a conference this week bringing together experts to share evidence, experiences and solutions for people at risk of displacement in due to climate change and disasters. A schedule of events and more information can be found here.![]()

Jane McAdam AO, Scientia Professor and Director of the Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Great Barrier Reef The Winner As Bid To Repeal Vital Water Laws Is Rejected

.jpg?timestamp=1635002659427)

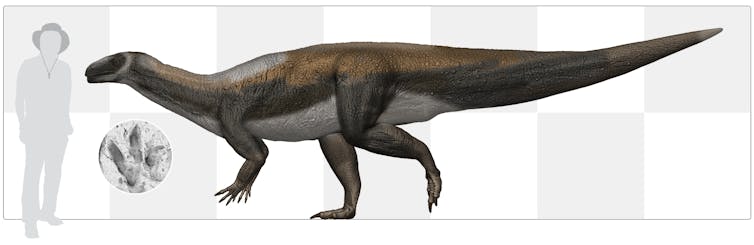

Fish Stocks Report Shows Urgent Reforms Needed To Counter Climate Crisis Impacts

NT Government Approves Empire Energy Fracking Project

Inland Rail Must Not Be Coal-Laden Bargaining Chip In LNP Climate Negotiations

When native title fails: First Nations people are turning to human rights law to keep access to cultural sites

In a shift from their usual conduct, Queensland police have recognised the cultural rights of Wangan and Jagalingou cultural custodians to conduct ceremony under provisions of the 2019 Queensland Human Rights Act.

Because of this act, the police were able to refuse to action a complaint from Adani to remove Wangan and Jagalingou cultural custodians camping on their ancestral lands adjacent to the Adani coal pit.

The police also issued a “statement of regret” for removing the group several months earlier.

The ceremonial grounds are on highly contested land that has been granted to Adani’s Carmichael coal mine by the state government.

In August 2019, Adani was granted freehold title over critical infrastructure areas of the Carmichael mine site by the Queensland government, without first notifying the Wangan and Jagalingou peoples.

This extinguished their native title over the site, affecting a number of peoples including the Juru, Jaang and Birrah, as well as the Wangan and Jagalingou.

Why Was Practising Cultural Ceremony So Controversial?

Over the past six weeks, Jagalingou cultural custodians have been conducting the Waddananggu ceremony, translated to English as “The Talking”. Describing the ceremony, Cultural Custodian Coedie McAvoy has said

We have set up a stone Bora ring and ceremonial ground opposite Adani’s mine and are asserting our human rights as Wangan and Jagalingou people to practice culture.

Since the leases were granted to Adani, police have repeatedly removed the Wangan and Jagalingou people from their traditional lands when conducting ceremonies. They have also been accused by journalists of acting as a “shield” to Adani’s corporate interests.

Adani’s proposed Carmichael open-cut and underground coal mine in the Galilee Basin in Central Queensland covers 200 square kilometres of land.

If built, it will be Australia’s largest and the world’s second largest coal mine. The project includes the construction of a 189-kilometre rail connection between the proposed mine and the Adani-operated Abbot Point Terminal adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef.

The proposed mining and railway developments encompass much of the Wangan and Jagalingou ancestral lands.

Read more: Protest art: rallying cry or elegy for the black-throated finch?

What Led To The Change In Police Attitudes?

Cultural Leader Adrian Burragubba brought a complaint to the Queensland Human Rights Commission after police broke up a Wangan and Jagalingou ceremonial campsite in August 2020. The complaint resulted in mediation between the police and Burragubba on behalf of his family and community over March to July of this year.

One outcome of the mediation was the Queensland police’s “statement of regret”, in which Assistant Commissioner Kev Guteridge said police recognise that Burragubba represents a group of traditional owners “aggrieved by Adani’s occupation of the land”, adding:

We acknowledge that the incident on 28 August, 2020, was traumatic for Mr Burragubba and his extended family, and caused embarrassment, hurt and humiliation.

According to The Guardian, Burragubba is thought to be the first Indigenous person to extract a public apology from a state agency since the enactment of the Queensland Human Rights Act.

Section 28 of the Act recognises Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples hold distinct cultural rights as Australia’s First Peoples:

They must not be denied the right, with other members of their community, to live life as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person who is free to practice their culture.

This is modelled on article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Articles 8, 25, 29 and 31 of the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The inclusion of this section is highly significant given Australia only endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2019. Australia is yet to implement the declaration into law, policy or practice at a federal level.

The Greens senator Lidia Thorpe said the inquiry’s recommendation of “free, prior and informed consent” did not go far enough to protect traditional owners.

Burragubba’s complaint under the Queensland Act was likely strengthened by the Wangan and Jagalingou peoples’ ongoing legal assertion of native title. 44b of the Native Title Act confers rights of access for traditional activities to a native title claim group.

This legal principle of “right of access” was bolstered by the findings in the case of Western Australia v Brown, 2014, which confirmed title was not wholly extinguished by the lease of land as long as native title is “not inconsistent with the lease”.

The Significance Of This Police Action Could Be Far Reaching

The new respect shown by Queensland police for the cultural rights of the Wangan and Jagalingou will not reinstate Wangan and Jagalingou native title. Nor will it stop the Adani mine.

But it means the Wangan and Jagalingou can continue to practice culture on Country, as they have for thousands of years, instead of being treated “like trespassers on their own land”. Their living connection to Country is not broken by the lease of land to Adani.

For Adani, it means the Wangan and Jagalingou people are an ongoing presence: a public reminder of cultural claim over the land where the mine is situated.

For the police, the significance goes beyond the struggle over the Adani mine. This change in police conduct could mark the end of police complicity in removing First Nations people from their ancestral land in the state of Queensland. Other state agencies will now also be forced to take the cultural rights of First Nations custodians seriously.

Read more: Australia listened to the science on coronavirus. Imagine if we did the same for coal mining

It is an important step on a national journey towards recognition of First Nations’ cultural rights. Like the Queensland Human Rights Act, Victoria and the ACT also enshrine human rights in state law, providing legal avenues validating cultural practice on Country against public authorities. If the federal government adopts the findings of the parliamentary inquiry into the destruction of the Juukan Gorge rock shelters, handed down earlier this week, First Nations’ cultural rights will be further protected.

The Inquiry committee recommended new Commonwealth legislation for stricter protection of sacred sites, and improvements to the Native Title Act. The committee has said new legislation should be underpinned by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The practice of Waddananggu is significant for the whole country. It is an opportunity for all of us to respectfully witness, talk and learn towards meaningful reconciliation.

McAvoy issued a broad invitation to the Waddananggu:

Stand with us to protect our human rights to practice ceremony and culture, and protect our homelands. ngali yinda banna, yumbaba-gi. We need you, to be heard.

Shelley Marshall, Associate Professor and Director of the RMIT Business and Human Rights Centre, RMIT University; Carla Chan Unger, Research Associate, RMIT University, and Suzi Hutchings, Associate Professor, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fixing Australia’s shocking record of Indigenous heritage destruction: Juukan inquiry offers a way forward

Deanna Kemp, The University of Queensland; Bronwyn Fredericks, The University of Queensland; Kado Muir, Indigenous Knowledge, and Rodger Barnes, The University of QueenslandOn May 24 last year, mining giant Rio Tinto legally destroyed ancient and sacred Aboriginal rock shelters at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia to expand an iron ore mine.

Public backlash prompted a parliamentary inquiry. After almost 18 months of submissions and hearings, the joint standing committee released its final report titled A Way Forward this week.

In tabling the report, committee chair and Liberal MP Warren Entsch said while the destruction was a disaster for traditional owners – the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples – it was “not unique”.

Rio Tinto’s actions form part of a broader discriminatory pattern of development in Australia. Traditional owners are denied the right to object and as a result, Aboriginal heritage is routinely destroyed.

The committee’s final report grapples with the complex issues of cultural heritage protection in Australia. It recommends major legislative reforms, including:

a new national Aboriginal cultural heritage act co-designed with Indigenous peoples

a new national council on heritage protection

a review of the Native Title Act 1993 to address power imbalances in negotiations on the basis of free prior and informed consent.

The report is strong on the need for change, although achieving this will be far from straightforward.

Hard-To-Resolve Issues

The committee’s interim report, was released in December last year. From it, we learned how Rio Tinto silenced traditional owners and prevented their cultural heritage specialists from raising concerns. Rio Tinto prioritised production over heritage protection.

A Way Forward places the tragedy of Juukan Gorge in a broader context. It shines a light on how the regulatory system empowered Rio Tinto to destroy the caves and prevented the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples from doing anything about it.

It also demonstrates how the system has run roughshod over Indigenous interests for decades. Governments have been able to make determinations about cultural heritage without proper consultation and consent.

The report focuses on getting the regulatory framework right. It succeeds in bringing a wide and complex set of controversial issues together in the one place. But many of these issues are highly contested, which has hindered previous attempts to solve them.

Already, two committee members, Senator Dean Smith and MP George Christensen, disagree with the rest of the committee on the need for the Commonwealth to set standards for states’ cultural heritage protection laws. They say this would constrain the mining industry and give anti-mining activists too much power.

In contrast, Greens Senator and Gunnai Gunditjmara and Djab Wurrung woman Lidia Thorpe supports traditional owners having a “right to veto” the destruction of their cultural heritage.

Read more: Juukan Gorge inquiry: a critical turning point in First Nations authority over land management

Western Australian Premier Mark McGowan and some industry organisations have dismissed the inquiry’s calls for a stronger federal government role in protecting cultural heritage across Australia. Western Australia is yet to pass its draft heritage law, which the premier says will address the issues raised in the final report.

Aboriginal groups disagree that ultimate control over the destruction of cultural heritage should rest with the minister. These groups have tabled their issues at the United Nations.

One of the most contentious matters addressed in the final report is the need to obtain free prior and informed consent of traditional owners under Australia’s federal and state laws, affording them the right to manage their own heritage sites.

Change Is Needed Despite Australia’s Economic Recovery Pressures

It is not an ideal time to be driving this type of major change. Australia is heading towards a federal election. The federal government is focused on COVID-19 vaccinations, opening borders and the nation’s economic recovery from the pandemic.

The mining sector sits at the centre of Australia’s economic recovery, with climate change driving demand for energy transition minerals. Australian states and territories are focused on mining these minerals for green and renewable technologies.

Green technologies will require more extraction of copper, nickel, lithium, cobalt, and other critical minerals, often located on Indigenous peoples’ lands and territories. This will put added pressure on the consent processes that A Way Forward recommends so strongly.

Read more: How Rio Tinto can ensure its Aboriginal heritage review is transparent and independent

Will Anything Actually Change?

So far, none of the big mining companies have come out in support of the committee’s recommendations for regulatory reform. But there are some positive prospects for change.

The inquiry has helped generate public awareness and a greater appreciation of Australia’s Indigenous heritage and the need to protect it. Australia’s commitments to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples have come under national and international scrutiny. This has added weight to the inquiry’s recommendations to elevate the importance of free prior and informed consent.

Institutional investors such as HESTA and Australian Council of Superannuation Investors have publicly supported the inquiry’s recommendations.

In the absence of regulatory reform to address systemic issues, Indigenous groups such as the National Native Title Council continue working with investor groups and peak industry bodies for change through developing voluntary guidelines and other formal commitments.

Indigenous Affairs Minister Ken Wyatt, along with the National Indigenous Australians Agency, has demonstrated capacity for co-design through their work on the Closing the Gap refresh.

Returning responsibility for cultural heritage to the Indigenous affairs minister’s portfolio, as recommended in the final report, could be a positive step.

Nothing short of the recommended reforms in the report will address the lessons learned from Juukan Gorge. The public must be vigilant in holding business, investors, and politicians to account by insisting on meaningful change.

Deanna Kemp, Professor and Director, Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, The University of Queensland; Bronwyn Fredericks, Pro Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Engagement), The University of Queensland; Kado Muir, Chair of National Native Title Council and Ngalia Cultural Leader, Indigenous Knowledge, and Rodger Barnes, Research Manager, Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Nature doesn’t recognise borders but countries can collaborate to save species. The Escazú Agreement shows how

Nature rarely recognises national borders. Many Australian birds, for example, are annual visitors, splitting their time between Southeast Asia, Russia, and Pacific Islands.

Yet, most efforts to protect ecological processes and habitats are designed and implemented by individual nations. Not only are these traditional approaches to conservation too geographically limited, they don’t address problems that seep across borders and drive ecosystem decline.

Our new research shows international collaboration and environmental management across national borders – a truly transboundary approach – is essential. We focused on an international environmental agreement that recently came into force across the Latin America and Caribbean region.

Known as the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean – or, more commonly, as the Escazú Agreement – it offers a hopeful example of new strategies to rise to this transboundary challenge.

What Is The Escazú Agreement?

In 2018, 33 Latin American and Caribbean countries were invited to sign and ratify the landmark Escazú Agreement, the first legally binding environmental agreement to explicitly integrate human rights with environmental matters.

It has so far been ratified by 12 signatory countries; 11 additional signatory countries have signed it but not yet ratified.

As we detail in our recent paper:

The agreement outlines an approach to enhance the protection of environmental defenders, increase public participation in environmental decision-making, and foster cooperation among countries for biodiversity conservation and human rights.

The Escazú Agreement And Human Rights

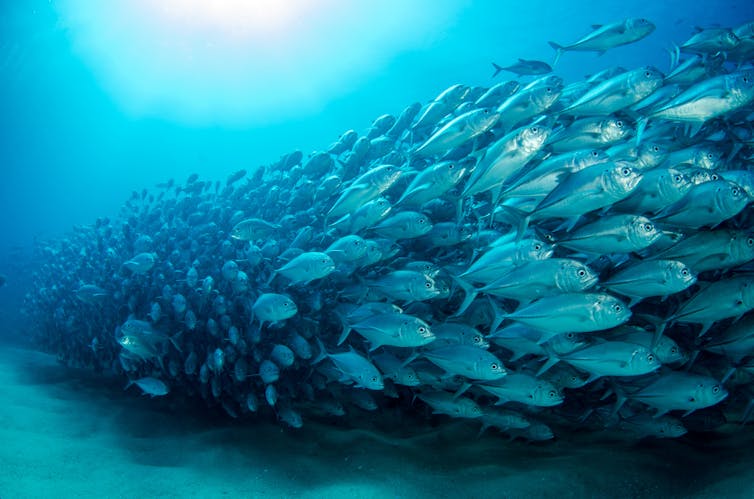

Countries from this region share transboundary species such as jaguars, as well as marine reserves containing immense biodiversity (including 1,577 endemic fish species).

But the Escazú Agreement isn’t just about flora and fauna. It also highlights the importance of human rights and public participation in environmental management – elements that are also vitally important for transboundary conservation.

Latin America and the Caribbean have a history of disputed maritime claims and a mismatch between management of terrestrial and marine jurisdictions.

Environmental protections and jurisdiction complexities have, in the past, curtailed the rights of Indigenous people who traditionally fish in these areas.

This is where the Escazú Agreement could have contributed. It sets out guidelines for public engagement and may have helped Indigenous people have their voices heard.

But Colombia and many island states are yet to ratify the Escazú Agreement. Doing so would help with these issues in future.

Many biodiverse countries with high levels of human rights violations and sharing multiple ecosystems and species have not yet ratified the agreement.

Marine Transboundary Conservation Needed

Ocean borders are extra messy. Some 90% of marine species compared to 53% of terrestrial species have habitat and migration ranges that cross national borders. Countries with large numbers of transboundary marine species include the US, Australia and Japan.

Many of Australia’s iconic ocean species – such as great white sharks, sea turtles, and humpback whales – are international migrants found in over 100 countries.

Even species that don’t move at all, like plants or corals, are often widely distributed. Take the slimy sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca), which grows along the coasts of almost 200 countries.

Marine species essentially share one ocean, making transboundary management extra challenging. Not only can threats such as pollution rapidly spread large distances over ocean currents, our traditional concept of sovereignty and borders makes even less sense on the ocean than it does on land.

Many countries must cooperate to protect species ranges across vast tracts of ocean.

Australia Plays A Key Role

Australia must step up as a leader of domestic and transboundary management. After the US, it has the most transboundary marine species in its ocean territory.

Most species are shared with Indonesia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and the high seas. As a well-resourced country, it is imperative Australia is part of international efforts to preserve this biodiversity.

Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case.

Australia has a poor record on protecting its terrestrial biodiversity, and is ranked among the top nations that import shark fins.

Our patchwork legislation leaves the door open for unsustainable and illegal shark finning.

Australian governments need to collaborate with other countries, industries, and socio-environmental NGOs, and local communities leading the way in best practice in environmental conservation.

The Escazú Agreement shows how this can be done.

A Beacon Of Hope

There’s no doubt international collaboration adds challenges to environmental management.

Yet the recent Escazú Agreement offers a beacon of hope in forming just international environmental agreements that protect both the environment and human rights.

Signing agreements like these is just the first step. Then, we must work to implement them consistently on land or sea, across countries and in a way that’s inclusive of local stakeholders.

The world’s nations have accepted the idea we must cooperate to combat climate change. We’ll also need international collaboration to protect the vast majority of Earth’s biodiversity and natural systems.

Read more: What is COP26 and why does the fate of Earth, and Australia's prosperity, depend on it? ![]()

Rebecca K. Runting, Lecturer in Spatial Sciences and ARC DECRA Fellow, The University of Melbourne; Leslie Roberson, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Queensland, and Sofía López-Cubillos, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Glasgow showdown: Pacific Islands demand global leaders bring action, not excuses, to UN summit

Wesley Morgan, Griffith UniversityThe Pacific Islands are at the frontline of climate change. But as rising seas threaten their very existence, these tiny nation states will not be submerged without a fight.

For decades this group has been the world’s moral conscience on climate change. Pacific leaders are not afraid to call out the climate policy failures of far bigger nations, including regional neighbour Australia. And they have a strong history of punching above their weight at United Nations climate talks – including at Paris, where they were credited with helping secure the first truly global climate agreement.

The momentum is with Pacific island countries at next month’s summit in Glasgow, and they have powerful friends. The United Kingdom, European Union and United States all want to see warming limited to 1.5℃.

This powerful alliance will turn the screws on countries dragging down the global effort to avert catastrophic climate change. And if history is a guide, the Pacific won’t let the actions of laggard nations go unnoticed.

A Long Fight For Survival

Pacific leaders’ agitation for climate action dates back to the late 1980s, when scientific consensus on the problem emerged. The leaders quickly realised the serious implications global warming and sea-level rise posed for island countries.

Some Pacific nations – such as Kiribati, Marshall Islands and Tuvalu – are predominantly low-lying atolls, rising just metres above the waves. In 1991, Pacific leaders declared “the cultural, economic and physical survival of Pacific nations is at great risk”.

Successive scientific assessments clarified the devastating threat climate change posed for Pacific nations: more intense cyclones, changing rainfall patterns, coral bleaching, ocean acidification, coastal inundation and sea-level rise.

Pacific states developed collective strategies to press the international community to take action. At past UN climate talks, they formed a diplomatic alliance with island nations in the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean, which swelled to more than 40 countries.

The first draft of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol – which required wealthy nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – was put forward by Nauru on behalf of this Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS).

Securing A Global Agreement In Paris

Pacific states were also crucial in negotiating a successor to the Kyoto Protocol in Paris in 2015.

By this time, UN climate talks were stalled by arguments between wealthy nations and developing countries about who was responsible for addressing climate change, and how much support should be provided to help poorer nations to deal with its impacts.

In the months before the Paris climate summit, then-Marshall Islands Foreign Minister, the late Tony De Brum, quietly coordinated a coalition of countries from across traditional negotiating divides at the UN.

This was genius strategy. During talks in Paris, membership of this “High Ambition Coalition” swelled to more than 100 countries, including the European Union and the United States, which proved vital for securing the first truly global climate agreement.

When then-US President Barack Obama met with island leaders in 2016, he noted “we could not have gotten a Paris Agreement without the incredible efforts and hard work of island nations”.

The High Ambition Coalition secured a shared temperature goal in the Paris Agreement, for countries to limit global warming to 1.5℃ above the long-term average. This was no arbitrary figure.

Scientific assessments have clarified 1.5℃ warming is a key threshold for the survival of vulnerable Pacific Island states and the ecosystems they depend on, such as coral reefs.

Read more: Who's who in Glasgow: 5 countries that could make or break the planet's future under climate change

De Brum took a powerful slogan to Paris: “1.5 to stay alive”.

The Glasgow summit is the last chance to keep 1.5℃ of warming within reach. But Australia – almost alone among advanced economies – is taking to Glasgow the same 2030 target it took to Paris six years ago. This is despite the Paris Agreement requirement that nations ratchet up their emissions-reduction ambition every five years.

Australia is the largest member of the Pacific Islands Forum (an intergovernmental group that aims to promote the interests of countries and territories in the Pacific). But it’s also a major fossil fuel producer, putting it at odds with other Pacific countries on climate.

When Australia announced its 2030 target, De Brum said if the rest of the world followed suit:

the Great Barrier Reef would disappear […] so would the Marshall Islands and other vulnerable nations.

Influence At Glasgow

So what can we expect from Pacific leaders at the Glasgow summit? The signs so far suggest they will demand COP26 deliver an outcome to once and for all limit global warming to 1.5℃.

At pre-COP discussions in Milan earlier this month, vulnerable nations proposed countries be required to set new 2030 targets each year until 2025 – a move intended to bring global ambition into alignment with a 1.5℃ pathway.

COP26 president Alok Sharma says he wants the decision text from the summit to include a new agreement to keep 1.5℃ within reach.

This sets the stage for a showdown. Major powers like the US and the EU are set to work with large negotiating blocs, like the High Ambition Coalition, to heap pressure on major emitters that have yet to commit to serious 2030 ambition – including China, India, Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Australia.

The chair of the Pacific Islands Forum, Fiji’s Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama, has warned Pacific island countries “refuse to be the canary in the world’s coal mine.”

According to Bainimarama:

by the time leaders come to Glasgow, it has to be with immediate and transformative action […] come with commitments for serious cuts in emissions by 2030 – 50% or more. Come with commitments to become net-zero before 2050. Do not come with excuses. That time is past.

Wesley Morgan, Researcher, Climate Council, and Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t underestimate rabbits: these powerful pests threaten more native wildlife than cats or foxes

In inland Australia, rabbits have taken a severe toll on native wildlife since they were introduced in 1859. They may be small, but today rabbits are a key threat to 322 species of Australia’s at-risk plants and animals — more than twice the number of species threatened by cats or foxes.

For example, research shows even just one rabbit in two hectares of land can solely destroy every regenerating sheoak seedling. Rabbits are also responsible for the historic declines of the iconic southern hairy-nosed wombat and red kangaroo.

Our latest research looked at the conservation benefits following the introduction of three separate biocontrols used to manage rabbits in Australia over the 20th Century — all three were stunningly successful and resulted in enormous benefits to conservation.

But today, rabbits are commonly ignored or underestimated, and aren’t given appropriate attention in conservation compared to introduced predators like cats and foxes. This needs to change.

Why Rabbits Are Such A Serious Problem

Simply put, rabbits are a major problem for Australian ecosystems because they destroy huge numbers of critical regenerating seedlings over more than half the continent.

Rabbits can prevent the long-term regeneration of trees and shrubs by continually eating young seedlings. This keeps ecosystems from ever reaching their natural, pre-rabbit forms. This has immense flow-on effects for the availability of food for plant-eating animals, for insect abundance, shelter and predation.

In some ecosystems, rabbits have prevented the regeneration of plant communities for 130 years, resulting in shrub populations of only old, scattered individuals. These prolonged impacts may undermine the long-term success of conservation programs to reintroduce mammals to the wild.

Things are particularly dire in arid Australia where, in drought years, rabbits can eat a high proportion of the vegetation that grows, leaving little food for native animals. Arid vegetation is slow growing and doesn’t regenerate often as rainfall is infrequent. This means rabbits can have a severe toll on wildlife by swiftly eating young trees and shrubs soon after they emerge from the ground.

Rabbits eat a high proportion of regenerating vegetation even when their population is at nearly undetectable levels. For example, it took the complete eradication of rabbits from the semi-arid TGB Osborn reserve in South Australia, before most tree and shrub species could regenerate.

Rabbits also spread weeds, cause soil erosion and reduce the ability of soil to absorb moisture and support vegetation growth.

If You Control Prey, You Control Predators

When restoring ecosystems, particularly in arid Australia, it’s common for land managers to heavily focus on managing predators such as cats and foxes, while ignoring rabbits. While predator management is important, neglecting rabbit control may mean Australia’s unique fauna is still destined to decline.

Cats and foxes eat a lot of rabbits in arid Australia and can limit their populations when rabbit numbers are low. A common argument against rabbit control is that cats and foxes will turn to eating native species in the absence of rabbits. But this argument is unfounded.

Cats and foxes may turn from rabbits to native species in the immediate short-term. But, research has also shown fewer rabbits ultimately lead to declines in cat and fox numbers, as the cats and foxes are starved of their major food source.

Regrowth Could Be Seen From Space

An effective way to deal with rabbits is to release biocontrol agents - natural enemies of rabbits, such as viruses or parasites. Our research reviewed the effects of rolling out three different biocontrols last century:

myxomatosis (an infectious rabbit disease), released in 1950

European rabbit fleas (as a vector of myxomatosis), released in 1968

rabbit haemorrhagic disease, released in 1995.

Each lead to unprecedented reductions in the number of rabbits across Australia.

Despite the minor interest in conservation at the time, the spread of myxomatosis led to widespread regeneration in sheoaks for over five years, before rabbit numbers built back up. Red kangaroo populations increased so much that landholders were suddenly “involved in a shooting war with hordes of kangaroos invading their properties”, according to a newspaper report at the time.

Following the introduction of the European rabbit flea, native grasses became prolific along the Mount Lofty Ranges, South Australia. Similarly, southern hairy-nosed wombats and swamp wallabies expanded their ranges.

By the time rabbit haemorrhagic disease was introduced in 1995, interest in conservation and the environment had grown and conservation benefits were better recorded.

Native vegetation regenerated over enormous spans of land, including native pine, needle bush, umbrella wattle, witchetty bush and twin-leaved emu bush. This regeneration was so significant across large parts of the Simpson and Strzelecki Deserts, it could be seen from space.

Red kangaroos became two to three times more abundant, and multiple species of desert rodent and a small marsupial carnivore (dusky hopping mouse, spinifex hopping mouse, plains rat, crest-tailed mulgara) all expanded their ranges.

But each time, after 10 to 20 years, the biocontrols stop working so well, as rabbits eventually built up a tolerance to the diseases.

So What Should We Do Today?

Today, there are an estimated 150-200 million rabbits in Australia, we need to be on the front foot to manage this crisis. This means researchers should continually develop new biocontrols — which are clearly astonishingly successful.

But this isn’t the only solution. The use of biocontrols must be integrated with conventional rabbit management techniques, including destroying warrens (burrow networks) and harbours (above-ground rabbit shelters), baiting, fumigation, shooting or trapping.

Land managers have a major part to play in restoring Australia’s arid ecosystems, too. Land managers are required by law to control invasive pests such as rabbits, and this must occur humanely using approved and recognised methods.

They, and researchers, must take rabbit management seriously and give it equal, if not more, attention than feral cats and foxes. It all starts with a greater awareness of the problem, so we stop underestimating these small, but powerful, pests.

The authors would like to acknowledge the significant contribution of Dr Graeme Finlayson from Bush Heritage Australia, who is the lead author of the published study.![]()

Pat Taggart, Adjunct Fellow, UNSW and Brian Cooke, Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham's Beach

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach