inbox and environment news: Issue 516

October 31 - November 6, 2021: Issue 516

Echidnas Are Out And About; Please Slow Down

Bioluminescence Seen This Week

Sparkling dolphins swim off our coast, but humans are threatening these natural light shows

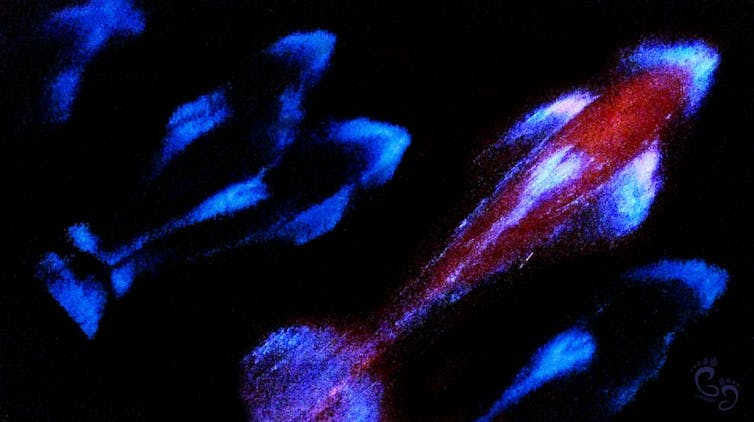

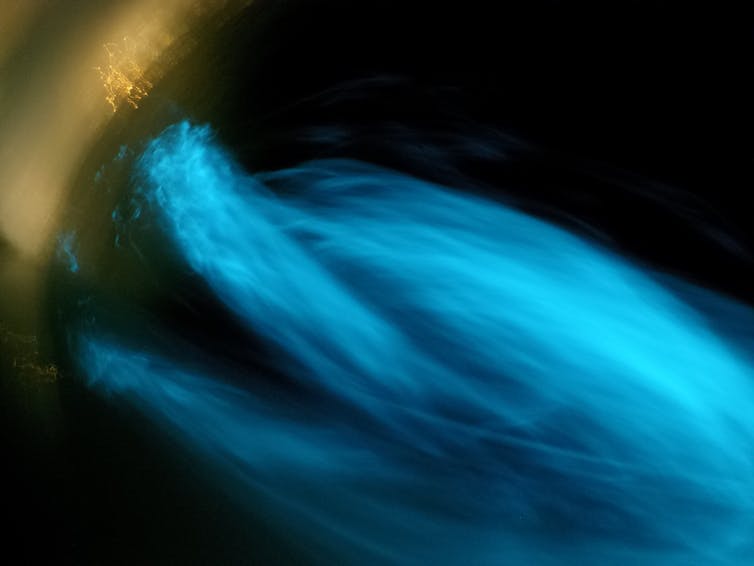

It was 2 am on a humid summer’s night on Sydney’s coast. Something in the distance caught my eye – a pod of glowing dolphins darted towards the bow of the boat. I had never seen anything like it before. They were electric blue, trailing swaths of light as they rode the bow wave.

It was a stunning example of “bioluminescence”. The phenomenon is the result of a chemical reaction in billions of single-celled organisms called dinoflagellates congregating at the sea surface. These organisms are a type of phytoplankton – tiny microscopic organisms many sea creatures eat.

Read more: Framing the fearful symmetry of nature: the year's best photos of landscapes and living things

Dinoflagellates switch on their bioluminescence as a warning signal to predators, but it can also be triggered when they’re disturbed in the water – in this case, by the dolphins.

You can see marine bioluminescence from land in Australia. Places like Jervis Bay and Tasmania are renowned for such spectacles.

But this dazzling night-time show is under threat. Light pollution creates brighter nights and disrupts ecological rhythms along the coast, such as breeding and feeding patterns. With so much human activity close to the shore and at sea, how much longer can we continue to enjoy this natural light show?

Lighting Up The World Has An Ecological Price

Light pollution is a well-known problem for inland ecosystems, particularly for nocturnal species.

In fact, a global study published earlier this year identified light pollution as an extinction threat to land bioluminescent species. The study surveyed firefly experts, who considered artificial light to be the second greatest threat to fireflies after habitat destruction.

At sea, artificial light pollution enters the marine environment temporarily (lights from ships and fishing activities) and permanently (coastal towns and offshore oil platforms). To make matters worse, light from cities can extend further offshore by scattering into the atmosphere and reflecting off clouds. This is known as artificial sky glow.

For organisms with circadian clocks (day-night sleep cycles), this loss of darkness can have damaging effects.

For example it can disrupt animal metabolism, which can lead to weight gain. Artificial light can also change sea turtle nesting behaviour and can disorientate turtle hatchlings when trying to get to sea, lowering their chances of survival.

Read more: Lights out! Clownfish can only hatch in the dark – which light pollution is taking away

It can also disorientate the foraging of fish communities; alter predatory fish behaviour (such as in Yellowfin Bream and Leatherjacks) leading to increased predation in artificial light at night; cause reproductive failure in clownfish; and change the structural composition of marine invertebrate communities.

For zooplankton – a vital species for a range of bigger animals – artificial light disrupts their “diel vertical migration”. This term refers to the movement of zooplankton from the depths of the ocean where they spend the day to reduce fish predation, rising to the surface at night to feed.

What Does This Mean For Bioluminescent Species?

Increased exposure to artificial light due to human activities, such as growing cities and increased global shipping movement, may disrupt when and where bioluminescent species hang out.

In turn, this may influence where predators move, leading to disruptions in the marine food web, potentially changing the dynamics of energy transfer efficiency between marine species.

Bioluminescence usually serves as a communication function, such as to warn off predators, attract a mate or lure prey. For many species, light pollution in the ocean may compromise this biological communication strategy.

And for light-producing organisms such as dinoflagellates, excess artificial light may reduce the effectiveness of their bioluminescence because they won’t shine as bright, potentially increasing their risk of being eaten.

A 2016 study in the Arctic revealed the critical depth where atmospheric light dims to darkness, and bioluminescence from organisms becomes dominant, was approximately 30 metres below the sea surface.

This means any change to light in the Arctic influences when marine organisms rise to the surface. If there is too much light, these organisms remain deeper for longer where it’s safe – reducing their potential feeding time.

Read more: Bright city lights are keeping ocean predators awake and hungry

What Can We Do?

Understanding the level at which artificial light penetrates the ocean is tricky, especially so when dealing with mobile sources of light pollution such as ships, which are becoming an almost permanent fixture in some areas of the ocean.

Pockets of darkness still remain in our oceans. But they are becoming rarer, making light pollution a serious global threat to marine life.

Read more: The glowing ghost mushroom looks like it comes from a fungal netherworld

The spectacle of glowing dolphins should serve as a timely reminder of our need to conserve the darkness we have left.

Simple steps at home such as switching off lights and reducing unnecessary outdoor lighting, especially if you live near the ocean, is a step in the right direction to doing your bit for nocturnal species.![]()

Vanessa Pirotta, Marine scientist and science communicator, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Careel Creek Birds: Aussie Backyard Bird Count 2021 Local Stats

Saturday afternoon, returning north after taking a few happy snaps was good to see a Dusky Moorhen, White-faced Heron and two lots of Pacific Black Ducks along the creek - which still smells putrid and looks rotten, but it was low tide. At least the jacaranda just past the high school is currently flowering, making it look nicer.

This is the first time in decades of walking beside the creek this bird-noticer has seen a Dusky Moorhen in the creek and it scuttled back under some nearby palm fronds on the western bank - possibly a nest may be under there - so please be careful not to scare this returnee to the creek if you're passing that way.

Did you know that our area is part of the ancient Pacific Black Duck songline? A recent Pittwater Online News article, Ellis Rowan's Adventures In Painting Birds, Flowers and Insects: 'This Meant That I Was Tapu - Sacred - Because I Painted The Birds', for Bird Week and the Aussie Backyard Bird Count inspirations shared as part of that an article, ‘Singing up Country’: reawakening the Black Duck Songline, across 300km in Australia’s southeast' by Robert S. Fuller, Western Sydney University; Graham Moore, Indigenous Knowledge, and Jodi Edwards, University of Sydney.

Almost 5 million birds were counted this year. In our area there were more counts submitted in some postcodes than 2020 while others were around the same, which may be reflected in the totals of birds counted overall.

The local statistics by postcode are:

2108: Checklists submitted: 53, Species sighted: 60, Birds sighted: 1,365

2107: Checklists submitted: 210, Species sighted: 76, Birds sighted: 5,320

2106: Checklists submitted: 76, Species sighted: 46, Birds sighted: 1,650

2105: Checklists submitted: 23, Species sighted: 43, Birds sighted: 565

2104: Checklists submitted: 38, Species sighted: 49, Birds sighted: 982

2103: Checklists submitted: 108, Species sighted: 56, Birds sighted: 2,970

2102: Checklists submitted: 64, Species sighted: 81, Birds sighted: 1,577

2101: Checklists submitted: 157, Species sighted: 106, Birds sighted: 2,844

2100: Checklists submitted: 171, Species sighted: 108, Birds sighted: 3,808

2099: Checklists submitted: 252, Species sighted: 91, Birds sighted: 5,192

2097: Checklists submitted: 79, Species sighted: 66, Birds sighted: 1,665

2096: Checklists submitted: 50, Species sighted: 51, Birds sighted: 1,077

2095: Checklists submitted: 99, Species sighted: 64, Birds sighted: 3,445

2094: Checklists submitted:, Species sighted: 27, Birds sighted: 470

2093: Checklists submitted: 101, Species sighted: 71, Birds sighted: 2,820

2092: Checklists submitted: 28, Species sighted: 43, Birds sighted: 569

Last year's statistics for our area are available in: Over 5 Million Birds Counted: Aussie Bird Count 2020 - Local By Postcode Statistics For Our Area

That Dusky Moorhen and the others spotted:

Boaties Be Aware As Whale Season Winds Down

Sydney Wildlife Mobile Care Unit: Meet Pteri.

Applications Open To Refresh The Face Of Fishing Environments

Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall has today opened applications for the Habitat Action Grants program, and encouraged passionate fishers to submit ideas to see local native fish habitats flourish.

Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall has today opened applications for the Habitat Action Grants program, and encouraged passionate fishers to submit ideas to see local native fish habitats flourish.Tuckeroo Becoming Troublesome In Pittwater

Avalon Preservation Association AGM 2021

Speaker: Angus Gordon OAM

“Global warming, is it real?”

The 2021 Annual General Meeting for Avalon Preservation Association (APA) will be held from 7.00pm on Thursday 11 November 2021 at the Avalon Beach surf life saving club.

Our special guest speaker is Angus Gordon OAM. Angus will talk on the controversial and very timely topic “Global Warming, Is it Real?”

Angus was General Manager of Pittwater Council from 1996 to 2005. He has a Master’s degree in Water and Coastal Engineering. In 2018 Angus received the Medal of the Order of Australia for “service to environmental management and planning, and to the community”.

Over the past 40 years he has undertaken projects in all states of Australia and in a number of overseas countries in coastal engineering, coastal zone management and flood management and engineering. Angus has served as a UN expert and was tasked with the development of the NSW Coastal Protection Act.

Angus Gordon OAM. AJG pic.

Speaker: Angus Gordon OAM

“Global warming, is it real?”

The 2021 Annual General Meeting for Avalon Preservation Association (APA) will be held from 7.00pm on Thursday 11 November 2021 at the Avalon Beach surf life saving club.

Our special guest speaker is Angus Gordon OAM. Angus will talk on the controversial and very timely topic “Global Warming, Is it Real?”

Angus was General Manager of Pittwater Council from 1996 to 2005. He has a Master’s degree in Water and Coastal Engineering. In 2018 Angus received the Medal of the Order of Australia for “service to environmental management and planning, and to the community”.

Over the past 40 years he has undertaken projects in all states of Australia and in a number of overseas countries in coastal engineering, coastal zone management and flood management and engineering. Angus has served as a UN expert and was tasked with the development of the NSW Coastal Protection Act.

Due to the current health situation, APA will hold the AGM strictly in line with the NSW Public Health Orders in force at the time. This may restrict the number of members and guests able to attend and guests may need to check in with a QR code, wear facemasks and show that they have been fully vaccinated.

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

Sweet Release For Critically Endangered Regent Honeyeaters

Big Boost To National Parks In Western NSW

- Once formally gazetted, Avenel, Koonaburra and other recently acquired properties will take the total addition to the national park estate to over 520,000 Hectares since 2019.

- This is an increase of almost 7.5% in the park estate in a little over 2 years.

- NPWS is currently delivering the biggest investment in visitor infrastructure in national park history and this program will be extended to Avenel and Koonaburra.

- At 121,390 hectares, Avenel is the second largest acquisition of land for a national park in NPWS history, after Narriearra that created Narriearra Caryapundy Swamp National Park.

- Avenel is special because it:

- straddles two bioregions – the Simpson Strzelecki Dune fields and the Broken Hill Complex

- protects three landscapes that are not protected in any other national park in the State and several other landscapes that are poorly reserved

- is diverse, protecting nearly 50 different ecosystems or plant community types – 21 of which are not reserved at the bioregional level.

- The property features an array of arid zone landforms transitioning from the rocky plateau of the Barrier Range – with floodplains, gilgais and drainage lines washing onto gibber plains – through to the spectacular dune fields of the Strzelecki Desert.

- Vegetation includes acacia and chenopod shrublands on the rocky ranges, Mitchell grass grasslands on the outwash plains, open woodlands dominated by white cypress pine and belah (a casuarina) across the dune fields and an extensive network of drainage channels that support riparian woodlands dominated by river red gum and coolabah.

- Habitat for an estimated 30 threatened species are likely to occur on the property including Australian bustard, dusky hopping-mouse, eastern fat-tailed gecko and yellow-keeled swainsona, a small forb with pea-like flowers.

- Lying on Ngurunta country to the west and the Maljangapa country to the east, the property has significant Aboriginal cultural heritage value, with significant artefacts and sites across the property including middens, quarries and burial sites.

- Avenel is set to become an exciting new visitor destination with campgrounds, 4WD circuits and walking trails. It is expected to open to the public in mid-2022.

- At 45,534 hectares, Koonaburra Station contains ecosystems unrepresented, or poorly protected in the national park system, as well as threatened ecological communities and species.

- It contains two threatened ecological communities: acacia melvillei shrubland in the Riverina and Murray-Darling Depression bioregions (endangered) which is distributed over the southern section of the property and Sandhill Pine Woodland in the Riverina, Murray-Darling Depression and NSW South Western Slopes Bioregions (endangered) which occurs extensively across the northern portion of the property.

- A comprehensive enhanced feral animal management program will be implemented across the Park, including upgraded, fit-for-purpose fencing infrastructure. This will assist in the regeneration of native vegetation and sequester significant volumes of carbon.

- The station is situated on The Wool Track, 100 kilometres north east of Ivanhoe and 140 kilometres south west of Cobar.

- The soils are a mixture of loam, light to heavy red clay, grey soil from light to heavy, self-mulching flats interspersed with millions of water depressions called crab or melon holes.

- Boasting 355mm rainfall, Koonaburra has dual frontage to over 20 kilometres of the Sandy Creek. The entire station is watered by massive flood out systems – a dozen lakes, box cowls and meandering waterways.

- Koonaburra Station once formed part of the giant pastoral lease Keewong Station established in the early 1800s which ran Merino sheep.

- Paroo Darling National Park is located approximately 50 kilometres to the north west, and Yathong Nature Reserve approximately 55 kilometres to the south-east.

- It features some of the holding's original buildings including the shearing shed, the original standalone and renovated meat house and the old harness and buggy shed.

NSW To Lead The Way On Net Zero Buildings

New RAA Board Members Appointed To Deliver For Rural NSW

- Chair: Mr Andrew Rice, a mixed farming operator from Parkes, and Director of Agricultural and Management Services at ASPIRE Agri, as well as non-executive director and chairperson of the not-for-profit company Field Applied Research Australia Pty Ltd, and non-executive director, Central West Local Land Services.

- Director: Ms Joanna Balcomb, a mixed farming operator from Cudal, and Chief Risk Officer for First Choice Credit Union in Orange, with experience as an independent RAA appeals panel member for both bushfires and floods.

Greater Sydney Water Strategy Open For Feedback

- Improving water recycling, leakage management and water efficiency programs, which could result in water savings of up to 49 gigalitres a year by 2040.

- Extending a water savings program, which has been piloted in over 1000 households and delivered around 20 per cent reduction in water use per household and almost $190 in savings per year for household water bills.

- Consideration of running the Sydney Desalination Plant full-time to add an extra 20 gigalitres of water per year.

- Expanding or building new desalination plants to be less dependent on rainfall.

- Investigating innovations in recycled water to improve sustainability.

- Making greater use of stormwater and recycled water to cool and green the city and support recreational activities.

Warragamba Dam Raising Project EIS On Public Exhibition

NSW Government Plan To Revitalise Peat Island And Mooney Mooney Released

- Nearly 270 new homes at Mooney Mooney to deliver more housing supply,

- Retention of nine unlisted historical buildings on the island, and four on the mainland, to be restored and used for new community and commercial opportunities,

- New retail and café or restaurant opportunities,

- Approximately 9.65 hectares of open space, including opportunities for walking and cycling tracks, parklands and recreational facilities,

- Retention of the chapel and surrounding land for community use, and

- 10.4 hectares of bushland dedicated as a conservation area.

Grattan on Friday: The weather gets choppy with Joyce and Morrison’s climate contradictions

Michelle Grattan, University of CanberraIn the press gallery at Parliament House, there’s a bell that years ago was rung regularly to alert journalists to press conferences and statements. Email has made it an anachronism.

But shortly before 8am on Thursday Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce appeared in the gallery, looking rather agitated, and personally rang the bell.

Joyce was there to lay an ownership claim to the exclusion of a methane reduction pledge from the 2050 net-zero climate plan Scott Morrison announced on Tuesday. “One of the key reasons that the Nationals went in to bat has become so clearly evident today,” Joyce declared.

This followed a report in The Australian, briefed by the office of Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor, rejecting the United States push for a 30% reduction by 2030 of methane emissions (produced by cows burping, gas extraction, and the like).

Taylor apparently had been onto the methane exclusion issue for some time. Later on Thursday Morrison said the government never had any intention of agreeing to the reduction. He also rejected Joyce’s confusing claim there was an agriculture carve out from the climate plan.

Who gets political “branding rights” on the treatment of methane was just the latest pinch point in the fallout from Tuesday’s announcement.

Much doubt has been created by the government’s failure to release the plan’s modelling, which Morrison says will be out in a few weeks – that is, after COP26 is well and truly behind him.

An industry department official told a Senate estimates committee the material was being put into digestible shape.

“As the plan was only finalised on Tuesday, we need to make sure we have written that technical work up. The actual modelling, of course, had been finalised at that point.

"But the write-up of that – we just need to take a little bit of extra time to make sure that it’s written clearly and able to be presented well to the Australian public,” Jo Evans, a deputy secretary in the department, said.

Meanwhile most of the trade-offs the Nationals have received for their reluctant support continue to remain a mystery.

Joyce, who became acting prime minister after Morrison departed on Thursday night for the G20 in Rome followed by COP26 in Glasgow, is likely to announce certain measures while he’s in the spotlight.

But others are to be in the budget update at the end of the year, presented as election commitments, or in next year’s budget if that occurs before the election.

Some of these unknown measures still have to be brought forward as cabinet submissions and go through the formal bureaucratic hoops, including being costed.

That shows how unsatisfactory the process has been – the government had months to deal with net-zero, settling things with the minor Coalition partner and finalising the trade-offs.

More importantly from the Nationals’ standpoint, they’re left exposed as they return to their electorates now parliament has risen for a three-week break. When they meet their constituents, they are not able to produce the suite of benefits they obtained in return for their policy sign-up.

Read more: View from The Hill: Morrison's net-zero plan is built more on politics than detailed policy

For Morrison the 2050 policy is an attempted barnacle-removing process, for both the Glasgow conference and the election. The Nationals, in contrast, see it adding to their barnacles.

The rejection of the requested methane cuts is another indication of the general weakness of the Australian plan. For all the struggle to land it, the plan is a bare minimum and will be seen as such in Glasgow.

Domestically, given the flaws and inadequacies, the plan is not likely to win votes for the government; rather, it is designed to stem the loss of them to Labor and independents in the “leafy” southern seats.

We’ve yet to see Labor’s alternative but one would think independent candidates will still have plenty of scope to stake out ground on the climate issue.

Earlier this week Morrison made some comments that set off speculation he planned a May poll, as opposed to a March-April one.

A May election would give the time for another budget, with the opportunities that brought.

Whether the election is in May or March, Morrison is already in campaign mode.

In this week’s Newspoll, the government is on the back foot, trailing 46-54% on the two-party vote. Regardless, both sides regard the battle as open.

Despite the election being so near, Labor hasn’t broken out of a trot. Albanese’s strategy is to leave the attention on the government and, more generally, to keep Labor a small target in policy terms. On the logic of its wider approach Labor could be expected to be cautious in the policy it issues on climate change, although it is still debating its position, expected to be released before Christmas.

Read more: With Labor gaining in polls, is too much Barnaby Joyce hurting the Coalition?

Albanese has been heavily influenced, negatively, by his predecessor Bill Shorten’s approach before the 2019 election, when Labor put forward an extensive and radical bag of policies.

The big target approach was seen to have scared off voters. Whether the small target will encourage people to vote Labor is hard to judge. The danger for the opposition is that, in the absence of a leader who is a drawcard, many people might be inclined to stick with the status quo.

Without the prospect of much substantive and highly differentiated policy being contested, the seat-by-seat campaigning will be especially significant at this election. Voters think local to a greater extent than they used to.

On Thursday the government introduced controversial legislation to require voters to produce ID at the polling booth. Labor and some in the welfare sector warn this will discourage the disadvantaged, including Indigenous people, from voting. The government says there would be plenty of protections – a range of identification could be used, including a Medicare card, and a person without identification would be allowed to cast a vote, with his or her identity checked later.

Given the widespread demand for identification for all sorts of things in our community, the requirement for ID when voting is not unreasonable. But it seems a solution in search of a problem, because voter fraud hasn’t been a feature of federal elections.

And it reflects distorted priorities that this legislation has been introduced before we see the bill for the long-awaited national integrity commission.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The ‘97% climate consensus’ is over. Now it’s well above 99% (and the evidence is even stronger than that)

Despite the overwhelming evidence, it’s still common to see politicians, media commentators or social media users cast doubt on the role of humans in driving climate change.

But this denialism is now almost nonexistent among climate scientists, as a study released this month confirms. US researchers examined the peer-reviewed literature and found more than 99% of climate scientists now endorse the evidence for human-induced climate change.

That’s even higher than the 97% reported by an influential 2013 study, which has become a widely cited statistic by both climate change deniers and those who accept the evidence.

Why has the needle evidently shifted even more firmly in favour of the evidence-based consensus? Or, to put it another way, what happened to the 3% of researchers who rejected the consensus of human caused climate change? Is this change purely because of the growing weight of evidence published over the past few years?

Unpicking The Polls

We must first ask whether the two studies are directly comparable. The answer is yes. The latest study has reexamined the literature published since 2012, and is based on the same methods as the 2013 study, albeit with some important refinements.

Read more: Consensus confirmed: over 90% of climate scientists believe we're causing global warming

Both studies searched the Web of Science database – an independent worldwide repository of scientific paper citations – using the keywords “global climate change” and “global warming”. However, the recent study added “climate change” to the other two keyword searches, because the authors found that most climate-contrarian papers would not have been returned with only the two original terms.

The 2013 study examined 11,944 climate research papers and found almost one-third of them expressed a position on the cause of global warming. Of these 4,014 papers, 97% endorsed the consensus position that humans are the cause, 1% were uncertain, and 2% explicitly rejected it.

A 2015 review examined 38 climate-contrarian papers published over the preceding decade, and identified a range of methodological flaws and sources of bias.

One of the reviewers commented that “every single one of those analyses had an error – in their assumptions, methodology, or analysis – that, when corrected, brought their results into line with the scientific consensus”.

For example, many of the contrarian papers had “cherrypicked” results that supported their conclusion, while ignoring important context and other data sources that contradicted it. Some of them simply ignored fundamental physics.

The 2015 reviewers also made the important point that “science is never settled and that both mainstream and contrarian papers must be subjected to sustained scrutiny”. This is the cornerstone of the scientific method, and few if any climate scientists would disagree with this statement.

Separating The Human Influence From The Natural

The recently published Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) Synthesis Report, says “it is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land”, and warns that the Paris Agreement goals of 1.5℃ and 2℃ above pre-industrial levels will be exceeded during this century without dramatic emissions reductions.

In reaching this conclusion, it is important to distinguish between changes caused by human activities altering the atmosphere’s chemistry, and climate variability caused by natural factors.

These natural variations include small changes in the Sun’s energy output due to sunspots and solar flares, infrequent volcanic eruptions, and the effects of El Niño weather patterns in the Pacific Ocean.

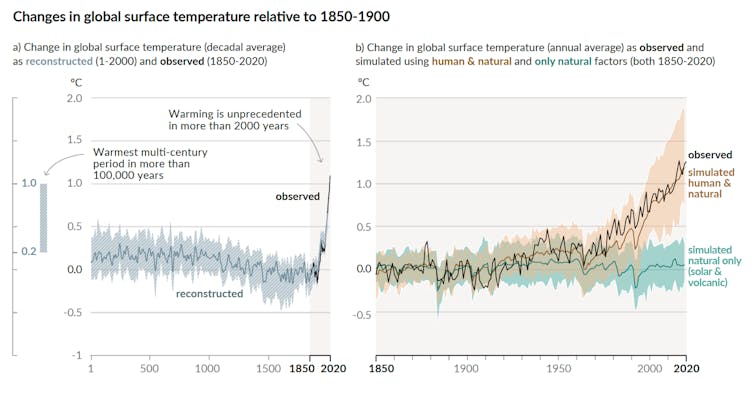

Excluding these natural variations, Earth’s surface temperature was generally stable from about 2,000 to 1,000 years ago. After that, the planet cooled by about 0.3℃ over several centuries, before the advent of fossil fuel-based industrialisation in the 1800s.

One study identified 12 major volcanic eruptions from 100 to 1200 CE, compared with 17 eruptions from 1200 to 1900 CE. Hence, heightened volcanic activity over roughly the past 800 years was associated with a general global cooling before the industrial revolution.

Current rates of global warming are unprecedented in more than 2,000 years and temperatures now exceed the warmest (multi-century) period in more than 100,000 years. Global average surface temperature for the decade from 2011-20 was about 1.1℃ higher than in 1850-1900. Each of the past four decades has been warmer than any preceding decade since 1850, when reliable weather observations began.

Read more: 99.999% certainty humans are driving global warming: new study

Researchers can separate human and natural factors in the modern global temperature record. This involves a process called hindcasting, in which a climate model is run backwards in time to simulate human and natural factors, and then compared with the observed data to see which combination of factors most accurately recreates the real world.

If human factors are removed from the data set and only volcanic and solar factors are included, then global average surface temperatures since 1950 should have remained similar to those over the preceding 100 years. But of course they haven’t.

The evidence, and the scientific consensus on it, are both clearer than ever.![]()

Steve Turton, Adjunct Professor of Environmental Geography, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Drying land and heating seas: why nature in Australia’s southwest is on the climate frontline

In a few days world leaders will descend on Glasgow for the United Nations climate change talks. Much depends on it. We know climate change is already happening, and nowhere is the damage more stark than in Australia’s southwest.

The southwest of Western Australia has been identified as a global drying hotspot. Since 1970, winter rainfall has declined up to 20%, river flows have plummeted and heatwaves spanning water and land have intensified.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns this will continue as emissions rise and the climate warms.

Discussion of Australian ecosystems vulnerable to climate change often focuses on the Great Barrier Reef, as well as our rainforests and alpine regions. But for southwest Western Australia, climate change is also an existential threat.

The region’s wildlife and plants are so distinctive and important, it was listed as Australia’s first global biodiversity hotspot. Species include thousands of endemic plant species and animals such as the quokka, numbat and honey possum. Most freshwater species and around 80% of marine species, including 24 shark species, live nowhere else on Earth.

They evolved in isolation over millions of years, walled off from the rest of Australia by desert. But climate heating means this remarkable biological richness is now imperilled – a threat that will only increase unless the world takes action.

Read more: Australia's south west: a hotspot for wildlife and plants that deserves World Heritage status

Hotter And Drier

Southwest WA runs roughly from Kalbarri to Esperance, and is known for its Mediterranean climate with very hot and dry summers and most rainfall in winter.

But every decade since the 1970s, the region’s summertime maximum temperatures have risen 0.1-0.3℃, and winter rainfall has fallen 10-20 millimetres.

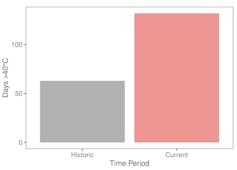

And remarkably, a 1℃ increase in the average global temperature over the last century has already more than doubled the days over 40℃ in Perth.

This trend is set to continue. Almost all climate models project a further drop in winter rainfall of up to 30% across most of the southwest by 2100, under a high emissions scenario.

The southwest already has very hot days in summer, thanks to heat brought from the desert’s easterly winds. As climate change worsens, these winds are projected to get more intense, bringing still more heat.

Drying Threatens Wildlife, Wine And Wheat

Annual rainfall in the southwest has fallen by a fifth since 1970. That might not sound dangerous, but the drop means river flows have already fallen by an alarming 70%.

It means many rivers and lakes now dry out through summer and autumn, causing major problems for freshwater biodiversity. For example, the number of invertebrate species in 17 lakes in WA’s wheatbelt fell from over 300 to just over 100 between 1998 and 2011.

The loss of water has even killed off common river invertebrates, such as the endemic Western Darner dragonfly, with most now found only in the last few streams that flow year round. The drying also makes it very hard for animals and birds to find water.

Most native freshwater fish in the southwest are now officially considered “threatened”. As river flow falls to a trickle, fish can no longer migrate to spawn, and it’s only a short march from there to extinction. To protect remaining freshwater species we must develop perennial water refuges in places such as farm dams.

The story on land is also alarming, with intensifying heatwaves and chronic drought. This was particularly dire in 2010/2011, when all ecosystems in the southwest suffered from a deadly drought and heatwave combination.

What does that look like on the ground? Think beetle swarms taking advantage of forest dieback, a sudden die off of endangered Carnaby’s Black Cockatoos, and the deaths of one in five shrubs and trees. Long term, the flowering rates of banksias have declined by 50%, which threatens their survival as well as the honey industry.

For agriculture, the picture is mixed. Aided by innovation and better varieties, wheat yields in the southwest have actually increased since the 1970s, despite the drop in rainfall.

Read more: Saving water in a drying climate: lessons from south-west Australia

But how long can farmers stay ahead of the drying? If global emissions aren’t drastically reduced, droughts in the region will keep getting worse.

Increased heating and drying will also likely threaten Margaret River’s famed wine region, although the state’s northern wine regions will be the first at risk.

Hotter Seas, Destructive Marine Heatwaves

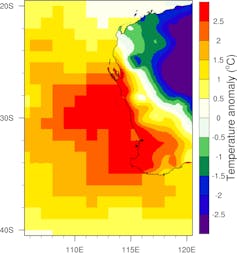

The seas around the southwest are another climate change hotspot, warming faster than 90% of the global ocean since the middle of last century. Ocean temperatures off Perth have risen by an average of 0.1-0.3℃ per decade, and are now almost 1℃ warmer than 40 years ago.

The waters off the southwest are part of the Great Southern Reef, a temperate marine biodiversity hotspot. Many species of seaweeds, seagrasses, invertebrates, reef fish, seabirds and mammals live nowhere else on the planet.

As the waters warm, species move south. Warm-water species move in and cool-water species flee to escape the heat. Once cool-water species reach the southern coast, there’s nowhere colder to go. They can’t survive in the deep sea, and are at risk of going extinct.

Marine heatwaves are now striking alongside this long-term warming trend. In 2011, a combination of weak winds, water absorbing the local heat from the air, and an unusually strong flow of the warm Leeuwin Current led to the infamous marine heatwave known as Ningaloo Nino.

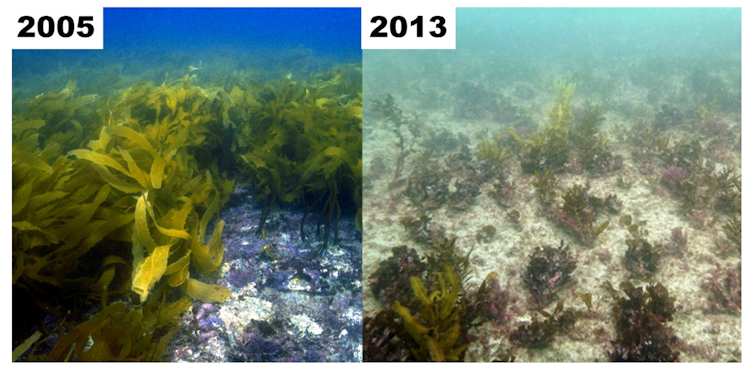

Over eight weeks, ocean temperatures soared by more than 5℃ above the long-term maximum. Coral bleached in the state’s north, fish died en masse, 34% of seagrass died in Shark Bay, and kelp forests along 100km of WA’s coast were wiped out.

Following the heatwave came sudden distribution changes for species like sharks, turtles and many reef fish. Little penguins starved to death because their usual food sources were no longer there.

Recreational and commercial fisheries were forced to close to protect ailing stocks. Some of these fisheries have not recovered 10 years later, while others are only now reopening.

This is just the start. Projections suggest the southwest could be in a permanent state of marine heatwave within 20-40 years, compared to the second half of the 20th century.

Read more: How much do marine heatwaves cost? The economic losses amount to billions and billions of dollars

Adaptation Has Limits

Nature in the southwest cannot adapt to these rapid changes. The only way to stem the damage to nature and humans is to stop greenhouse gas emissions.

Australia must take responsibility for its emissions and show ambition beyond the weak promise of net-zero by 2050, and commit to real 2030 targets consistent with the Paris climate treaty.

Otherwise, we will witness the collapse of one of Australia’s biological treasures in real time.![]()

Jatin Kala, Senior Lecturer and ARC DECRA felllow, Murdoch University; Belinda Robson, Associate Professor, Murdoch University; Joe Fontaine, Lecturer, Environmental and Conservation Science, Murdoch University; Stephen Beatty, Research Leader (Catchments to Coast), Centre for Sustainable Aquatic Ecosystems, Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University, and Thomas Wernberg, Professor, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Fewer than half of Australia’s 150 biggest companies have committed to zero emissions by 2050

Corporate Australia has of late become a strong voice for more action on climate change. Earlier this month the Business Council of Australia, which represents the nation’s 100 biggest companies, declared its support for the federal government committing to halving its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, and net zero emissions by 2050.

“Business is leading,” says the report arguing this case. “Domestic and international companies are rapidly adopting net zero and ambitious internal decarbonisation targets.”

That report goes on to say that among the top 200 companies listed on the Australian Stock Exchange – the ASX 200 – net-zero commitments in the past year have “more than tripled” to about 50 companies and that this represents about half the ASX200’s total market capitalisation.

Our research on Autralia’s 150 biggest public companies supports the Business Council’s claim that commitments are growing. But there’s still a long way to go in showing evidence of tangible progress.

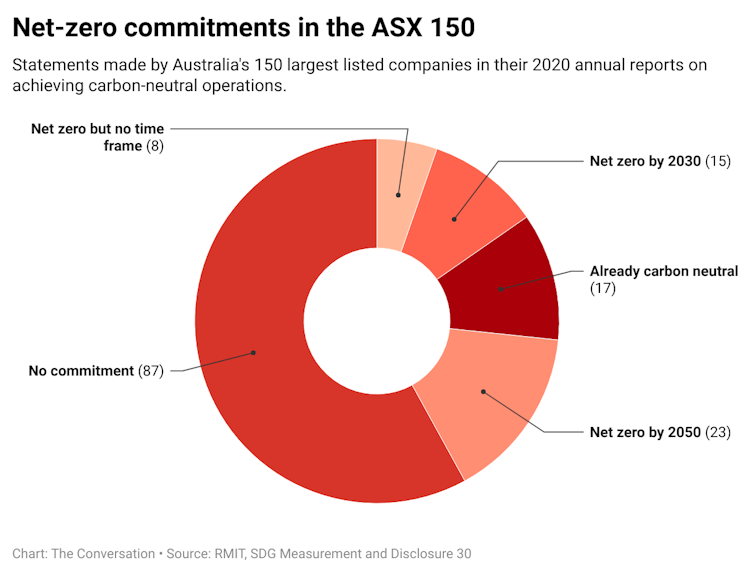

Based on disclosures made in companies’ 2020 annual reports, our research shows 17 reported having achieved carbon neutrality while 46 have either declared commitment or an intention to achieve net zero emissions.

Of those 46 companies aiming for net zero, 38 declared commitment to achieving net zero by 2050 and 15 of them disclosed their intention to become carbon neutral by 2030. Another eight companies did not set a time frame (which arguably makes the commitment meaningless).

That means just 55 have committed to zero emissions by 2050.

Measuring Sustainable Development Goals

These findings on corporate climate action are part of a broader research project by RMIT University and CPA Australia into action by Australian companies on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

This framework of 17 goals was adopted by the United Nations in 2015 to provide a uniform approach to defining and measuring progress on things such as eliminating poverty and discrimination, improving health and well-being, and achieving economic progress without harming the environment.

Each of the goals has a set of targets to measure achievement by 2030 (there are a total of 196 targets). On the goal of climate action (SDG13), one of the five targets is to integrate climate change measures into policies, strategies and planning.

The SDGs were originally intended for governments. But business committing and acting on them is fundamental for the transformational investments and new markets needed to promote more sustainable practices.

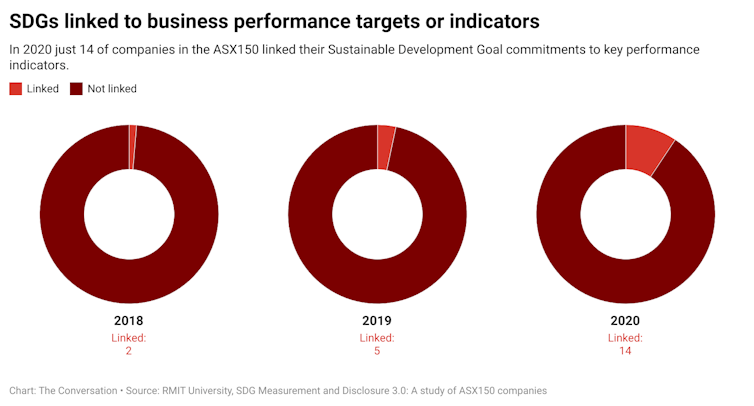

We have been monitoring the extent of corporate Australia’s commitment to the SDGs since 2018, based on disclosures in their annual reports. In particular we have been interested in evidence these commitments are meaningful, through companies having mechanisms to measure and report on what they have achieved.

Commitments Growing, But KPIs Lacking

The good news is that recognition and disclosure is growing. In 2018 just 56 of the ASX 150 (37%) mentioned the Sustainable Development Goals in their annual reports. In 2019 it was 72 (48%). In 2020 it was 94 (62%).

Statements on commitments, however, are not meaningful unless supported by evidence of actual progress. This requires having a plan to turn a commitment into an achievement, setting key performance indicators (KPIs), measuring success (or failure) and reporting on results.

On these things far less progress has been made. The number of companies aligning their KPIs with SDG targets has increased from two (1.3%) in 2018, to five (3.3%) in 2019, and 14 (9.3%) in 2020.

Including colourful SDG graphics in annual reports and having senior executives making public commitments is one thing. But without reporting on the actual measures to turn a commitment into actual progress, companies can easily be accused of lack of transparency or even green washing.

For corporate Australia to really claim the mantle of leading on climate action, our major companies must also lead in setting clear goals and timelines, defining measurements by which they will rate their success, and being fully transparent in reporting their progress.![]()

Renzo Mori Junior, Senior Advisor, Sustainable Development, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

What’s behind News Corp’s new spin on climate change?

Australia’s Murdoch-owned tabloid newspapers – including The Daily Telegraph, Herald Sun and Courier Mail – have embarked on a bold new climate change campaign.

This climate rebrand, dubbed “missionzero2050”, is billed by the company as “putting Australia on a path to a net zero future”.

The change has surprised Australian media observers and, no doubt, media consumers given News Corp’s long-held climate denialist stance, which is well documented in public commentary and research.

So why is this happening now? And what does it mean?

What Does The New Campaign Say?

Last Monday, News Corp’s tabloid mastheads began the new campaign with a 16-page wraparound supplement and a splashy online campaign championing the drive to cut climate warming emissions by 2050.

Read more: What is COP26 and why does the fate of Earth, and Australia's prosperity, depend on it?

News Corp must have done its climate communication research. It has assembled a collection of stories using best-practice climate communication techniques: telling a global story with a local face, visualising climate impacts and focusing on solutions, not creating fear.

Crucially, the campaign marks a change from News Corp’s long-held position on climate action. It’s moved from calling decarbonisation too expensive and bad for jobs (it tagged the cost at A$600 billion in 2015), to describing it now as a potential $2.1 trillion economic “windfall”, offering opportunities for 672,000 new jobs.

News Corp And Climate Change

What News Corp does matters, because it has extensive influence in Australia’s media market.

The company’s newspaper, radio, pay TV and online news portfolio gives it significant audience reach and huge political sway. In April, former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull labelled the Murdoch media “the most powerful political actor in Australia”.

Most people derive their understanding of climate change from the media. So News Corp’s audience reach (which included about 100 print and digital mastheads as of early 2021) has given it extensive influence over Australians’ knowledge of and opinions about climate change, profoundly shaping public debate.

Murdoch media outlets have denied the science of climate change and ridiculed climate action for more than a decade.

A 2013 study by the Australian Centre for Independent Journalism found climate denialist views in a third of Australian media coverage of climate change, and pointed to News Corp outlets as the key reason for this.

News Corp’s commentators have described those arguing for climate action as “alarmists” and “loons”, who are prone to “warming hysteria”. They have also said climate concern is a “cult of the elite” and the “effects of global warming have so far proved largely benign”.

Despite this, in 2019, Murdoch declared there were “no climate change deniers” in his company.

Signs Of A Mood Shift

This pivot on climate change was not entirely unexpected.

The company had been signalling a mood shift since early 2020, in the wake of its controversial reporting on the Black Summer bushfires, which saw it accused of downplaying the fires and fuelling misinformation about the cause.

At that time, Rupert Murdoch’s son James expressed his concerns about the “ongoing denial” of climate change at News Corp in the face of “obvious evidence to the contrary”.

He subsequently resigned his position on the company’s board. Early last month, the Nine newspapers flagged an imminent change of stance on climate at News Corp, noting, “Rupert Murdoch’s global media empire has faced growing international condemnation and pressure from advertisers over its editorial stance on climate change”.

The Fine Print

Despite the gloss of missionzero2050 (the newspapers say they are only focusing on “positive stories” about creating “a clean future while having fun and feeling good at the same time”), a deeper analysis shows the campaign has some quite specific agendas, signalling its climate epiphany may be limited.

In the stories that make up the campaign, it is still rolling out business-as-usual narratives like:

defending Australia’s emissions as small compared to other countries, especially China (therefore suggesting we do not need to take drastic action)

framing renewables as an unreliable source of energy (so not an adequate replacement for fossil fuels)

promoting Australia’s coal as cleaner than other countries’ (some of it may be, but the International Energy Agency says the world must start quitting coal now to stay within safer global warming limits)

promoting gas as having half the emissions of coal (burning gas does emit less carbon dioxide, but its extraction also causes fugitive emissions of methane, a gas that’s about 30 times more powerful as a heat-trapping greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over 100 years)

advocating carbon capture and storage (which is not yet a proven way to reduce emissions from burning fossil fuels)

criticising a carbon pollution price (economists widely agree this is the single most effective way to encourage polluters to reduce greenhouse gas emissons).

Read more: Australia's top economists back carbon price, say benefits of net-zero outweigh cost

Surprisingly, the campaign is making a big effort to spruik nuclear power. It states: “our aversion to nuclear energy defies logic” and advocates strongly for an Australian nuclear industry for “national security” purposes as well as energy.

Overall, the missionzero2050 agenda seems to be set on supporting new and existing extractive industries and Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s “gas-led recovery”.

Strangely, the campaign also emphasises “putting Australia first” – although efforts to deal with climate change must be inherently globally focused.

Loud Silences

What’s most perverse, perhaps, about missionzero2050 are the things it does not say or acknowledge. There has been no mention of News Corp’s years of intentionally undermining decarbonisation and helping to topple Australian leaders who advocated for climate action.

Oddly, News Corp has not muzzled its high-profile commentators. Columnist Andrew Bolt was quick to make it known that he thought the campaign was “rubbish”.

Nor has it aligned its advertising with the missionzero2050 message. For example, last Wednesday, the Herald Sun ran a half-page ad placed by the climate “sceptical” Climate Study Group about the “great climate change furphy,” discrediting climate science and advocating for more coal and nuclear power.

What Might It Mean?

The timing of the campaign, just as Morrison negotiates with the Nationals ahead of the COP26 climate conference, is likely to be no coincidence. It seems designed to provide cover for a potential shift on the part of the Coalition towards a mid-century net zero declaration.

Morrison is also under intense pressure from other world leaders to lift his ambitions on climate. He’ll be expected to bring new plans for emissions cuts to the table in Glasgow.

Some commentators have labelled the Murdoch pivot “greenwashing”. Others have called it a “desperate ploy to rehabilitate the public image of a leading climate villain”.

However perplexing the Murdoch papers’ climate U-turn may seem, at least Morrison will know Australia’s “most powerful political actor” is not likely to campaign against any 2050 net zero declaration.

Given News Corp’s power to subvert the national narrative on climate, that’s important if we want to see the action that’s so long overdue.![]()

Gabi Mocatta, Research Fellow in Climate Change Communication, Climate Futures Program, University of Tasmania, and Lecturer in Communication - Journalism, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s net-zero plan fails to tackle our biggest contribution to climate change: fossil fuel exports

The Morrison government’s eleventh hour commitment to net zero by 2050 is a monumental failure.

Critics rightly point out the government’s plan involves no increase to Australia’s 2030 climate target, no new funding or policies and few concrete details of how reductions will be achieved – except a heavy reliance on technological solutions not yet invented.

What we do know is not encouraging. The questionable focus on subsidising technologies such as carbon capture and storage seems designed to allow the fossil fuel industry to keep operating for decades to come. There is also no detail on how the promised jobs and economic growth will be achieved, nor any plan to legislate the projected reductions in emissions.

But the most glaring gap is a complete failure to tackle Australia’s biggest contribution to climate change: our coal, gas and oil exports. What’s more, the government’s “technology not taxes” mantra belies the fact taxpayers, not big business, will incur a multi-billion dollar bill for emissions reduction.

No Net-Zero Without Exports

The government’s plan contains no credible strategy to reduce the enormous emissions produced by Australia’s fossil fuel industry, especially the export industry.

Australia’s fossil fuel exports have more than doubled since 2005. We are the world’s largest exporter of metalurgical coal and the third largest exporter of fossil fuels overall.

Read more: Between the lines, Morrison's plan has coal on the way out, with the future bright

The emissions caused by other countries burning Australia’s exported fossil fuels are more than double Australia’s domestic emissions.

Annual domestic greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 were around 494 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. Yet the emissions from exported coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG) alone were 1,073 million tonnes, according to my calculations using standard conversion factors. This is more than the emissions caused by the 2019-2020 bushfires.

For a net-zero plan not to include a strategy to phase out this enormous contribution to climate change is an abrogation of responsibility.

Australia is not responsible for all of the emissions produced by exported fossil fuels – after all other countries consume them. Still, Australia must take a high degree of responsibility given the billions of dollars in subsidies and environmental approvals that allow the industry to exist.

The supply of cheap, subsidised fossil fuels to global markets significantly worsens climate change, even if not all of the emissions from those exported fuels are Australia’s responsibility.

The government is asking the wrong questions. Instead of asking how it can reduce domestic emissions, it should be asking: what is Australia’s contribution to climate change and how can it be reduced? Given the combined emissions from Australia’s exported fossil fuels and domestic emissions are around 3-4% of global emissions, this must be addressed.

And there is clear evidence Australia’s fossil fuel industry will continue to enjoy strong support.

The net zero plan includes directing the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency to fund technologies like carbon capture and storage – the process of capturing carbon emissions from the source and storing in the ground – which will channel more taxpayer dollars into the fossil fuel industry.

The federal government also continues to grant approvals for new fossil fuel developments that will create millions of tonnes of CO₂ equivalent. This includes three new coal mines and a new major gas power plant in Kurri Kurri in the Hunter Valley.

These actions are not consistent with a real commitment to reducing Australia’s contribution to climate change.

Technology Via Taxation

The support the fossil fuel industry will receive under the government’s plan also means the government mantra of “technology not taxes” is highly misleading.

The commitment in the government’s new plan to spend A$20 billion of taxpayer money on new technologies is using taxes to pay for climate action. Any subsidy for fossil fuel production, the development of new carbon capture and storage technologies or other low emissions technology, comes from taxation revenue.

There are many policies that would shift the burden of climate action away from taxpayers and onto the companies responsible for the pollution. This includes extracting the full historical social cost of carbon from big polluters or legislating a carbon price.

But as we all know, the Coalition scrapped the Gillard government’s carbon price in 2014 and such a policy is now considered political poison.

The bulk of federal tax revenue comes from individual taxpayers. The majority of the big fossil fuel exporters such as Shell or ExxonMobil, which have contributed huge volumes of greenhouse gases, pay little or no corporate tax. And under the Morrison plan they will not have to pay for their pollution.

The Plan Procrastinates On Climate Action

The timing of this plan is also deeply flawed. Even with Australia’s projected (not legislated) emissions reduction of 30-35% by 2030, this still leaves around 70% of the emissions reductions to happen after 2030. Given the urgency of the problem, the proportions ought to be the other way around.

In a briefing note released Monday by the ARC Centre of Excellence, Australian climate scientists say even if global emissions do reach net-zero by mid-century, temperatures are still likely to exceed 2℃ this century if short-term action doesn’t increase.

Read more: If all 2030 climate targets are met, the planet will heat by 2.7℃ this century. That's not OK

Australia’s weak targets are made worse by the fact our per capita emissions at 22 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent are double the OECD average. Australia’s long history of high domestic and exported emissions means we ought to be on top of the list of emission reducers, not at the bottom.

The position Australia finds itself in on the eve of the COP26 negotiations could not be more stark. We can either join the ranks of the climate ambitious and come up with a real plan with substantial interim targets. Or, we can join with the likes of Saudi Arabia and delay action further.

But we cannot claim to be taking climate action while simultaneously being one of the world’s largest coal exporters – and pretending it makes no contribution to climate change.![]()

Jeremy Moss, Professor of Political Philosophy, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

If all 2030 climate targets are met, the planet will heat by 2.7℃ this century. That’s not OK

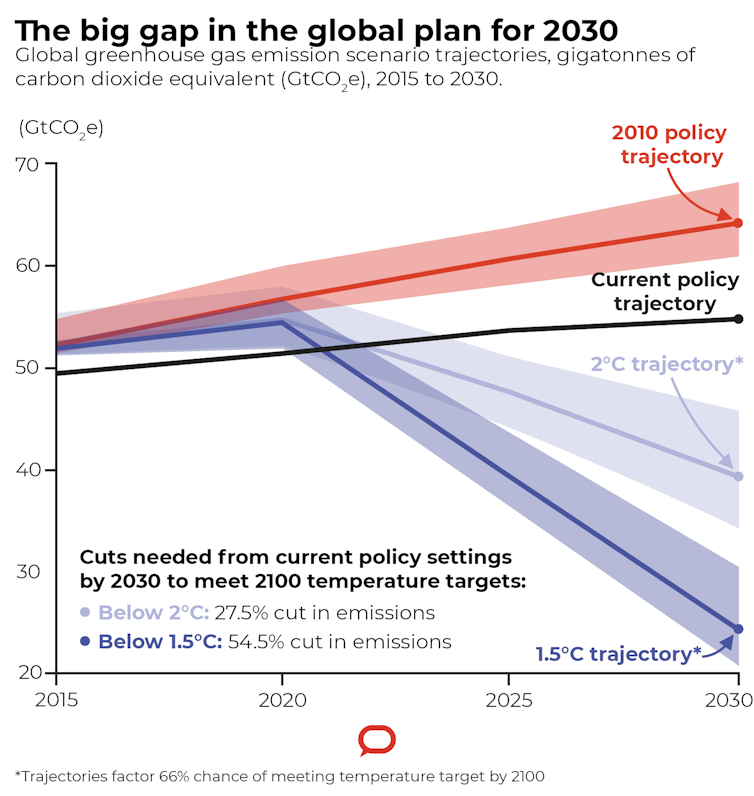

If nations make good on their latest promises to reduce emissions by 2030, the planet will warm by at least 2.7℃ this century, a report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has found. This overshoots the crucial internationally agreed temperature rise of 1.5℃.

Released today, just days before the international climate change summit in Glasgow begins, UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report works out the difference between where greenhouse emissions are projected to be in 2030 and where they should be to avoid the worst climate change impacts.

It comes as the Morrison government yesterday officially committed to a target of net-zero emissions by 2050. The government made no changes to its paltry 2030 target to reduce emissions by between 26% and 28% below 2005 levels, but announced that Australia is set to beat this, and reduce emissions by up to 35%.

The UNEP report was conducted before Australia’s new 2050 target was announced, but even with this new pledge, global pledges will undoubtedly still be short of what’s needed.

The report found global targets for net-zero emissions by mid-century could cut another 0.5℃ off global warming. While this is a big improvement, it will still see temperatures rise to 2.2℃ this century. If we don’t close the global emissions gap, what will Australia, and the rest of world, be forced to endure?

Pledges Are Falling Short

As of August 30 (the date the UNEP report reviewed to), 120 countries had made new or updated pledges and announcements to cut emissions.

The US, for example, has set an ambitious new target of reducing emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels in 2030. Similarly, the European Union will cut carbon emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared with 1990 levels.

But the UNEP report shows all these pledges are falling short. It finds we must take an extra 28 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent off annual emissions by 2030, over what’s already promised.

The UNEP also found that while effectively delivering on net-zero targets by mid-century could mitigate the predicted temperature rise, current plans are vague, with many delaying action until after 2030, which is too late. These net-zero targets, including Australia’s, are also based on technologies that don’t exist on a large-scale yet, such as carbon capture and storage.

UNEP’s findings echo a briefing note by Australian climate scientists on Monday, who say even if global emissions reach net-zero by mid-century, there’s still a high chance temperatures will exceed 2℃ this century if we neglect to increase short-term action.

When the UNEP report was conducted, 49 countries plus the EU had pledged a net-zero target, which accounts for a third of the global population and half of global emissions. Eleven of these targets are enshrined in law, which accounts for 12% of global emissions.

Did COVID-19 make a difference? While carbon emissions fell by 5-6% in 2020, this was due to widespread lockdowns and other restrictions worldwide, rather than long-lived changes in how society functions.

The report notes that as restrictions ease, emissions are expected to sharply rise again this year to a level only slightly lower than in 2019. To avoid the worst climate change effects, a sustainable year-on-year reduction in carbon emissions is required.

What Does This Mean For Australia?

To date, the world has warmed by about 1.2℃ since pre-industrial levels, and we’re already experiencing significant climate change impacts and worsening extreme weather events.

The western North America heatwave in late June this year saw temperature records and heat-related deaths spike. This event would have been virtually impossible without human-caused greenhouse gas emissions warming the planet.

Similarly, the extreme rainfall that led to recent floods in central Europe which tore through towns in July were very likely enhanced by global warming.

In Australia, we’ve seen our own share of extreme events in recent years that were intensified by climate change, including record hot summers and the devastating bushfires of 2019 and 2020.

Meeting the Paris Agreement and keeping global warming below 2℃ or even 1.5℃ would still lead to continued sea level rise and worsening heatwaves on land and in our oceans.

If we fail to meet the Paris Agreement and warm the world by closer to 3℃ by 2100, then the impacts of climate change worsen considerably.

Read more: Seriously ugly: here's how Australia will look if the world heats by 3°C this century

Warm water coral reefs, including the Great Barrier Reef, are already stressed by frequent bleaching events and might be on the brink already. Most coral reefs would likely not survive sustained 1.5℃ warming, much less likely 2℃ global warming, let alone 3℃ of warming. However, limiting warming to 1.5℃ rather 2℃ makes a huge difference for many other ecosystems.

Historically hot summers, such as the Angry Summer of 2012 and 2013 and the Black Summer of 2019 and 2020, would be cooler than most Australian summers in a 2-3℃ warmer world. Parts of Sydney and Melbourne would likely see 50℃ temperatures during heatwaves.

And at 2-3℃ global warming, most of the continent would experience more short bursts of extreme rainfall that causes flash flooding, Meanwhile, droughts are projected to worsen, especially in the southwest and southeast of the continent.

While Australia would experience major climate change impacts if the world fails to meet the Paris Agreement, the outlook is much worse and more devastating for less wealthy nations. Intensified heatwaves, more extreme rain events and droughts would make life harder for many, as developing nations don’t have the resources to adapt.

A Big Task For COP26

It is imperative we avoid the impacts of climate change that come with a 2 to 3℃ average temperature rise.

To have any chance at meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement, all countries will need to significantly increase their ambition and pledge much greater reductions in carbon emissions in Glasgow.

Wealthy, high-emitting countries should lead the way with stronger pledges, and agree on terms to finance climate mitigation and adaptation in developing countries.

Time is fast running out to avert more dangerous climate changes, and the world cannot afford a missed opportunity at COP26.

Read more: A successful COP26 is essential for Earth's future. Here's what needs to go right ![]()

Andrew King, ARC DECRA fellow, The University of Melbourne and Malte Meinshausen, A/Prof., School of Earth Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s stumbling, last-minute dash for climate respectability doesn’t negate a decade of abject failure

Prime Minister Scott Morrison is poised to announce Australia will adopt a target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The pledge is long overdue – but the science tells us 2050 is about a decade too late to reach net-zero.

If we want to meet the goals of Paris climate agreement and limit global warming to 1.5℃ this century, what actually matters is the action we take this decade.

No doubt the federal government will expect to be congratulated for finally succumbing to the extraordinary international and community pressure brought in the lead up to the COP26 meeting in Glasgow.

But after eight years without an effective policy to reduce emissions, it’s sadly too little, too late.

Balancing The Carbon Budget

The carbon budget approach is a useful way to assess whether climate targets are adequate.

Carbon budgets show the amount of carbon dioxide (CO₂) that can be emitted for a given level of global warming. It’s based on the (approximately linear) relationship between the amount of CO₂ emitted from all human sources since the beginning of industrialisation and the increase in global average surface temperature.

Once the carbon budget has been “spent”, or emitted, emissions must be at net-zero to avoid exceeding the corresponding temperature target. In a report released in April, the Climate Council used this approach to estimate Australia’s fair share of the global effort to meet the Paris targets.

To keep global temperatures below 1.5℃, and assuming humans emit CO₂ at the current rate of 43 billion tonnes a year, we have about 2.5 years of emissions still to spend. This pushes out to 5 years at a linear rate of emission reduction, achieving net-zero emissions by 2026.

Using the same logic, we also calculated when the world would exceed the Paris ambition of staying “well below 2℃” of warming, which we assume to be 1.8℃. Our remaining global carbon budget would be spent in about 9.5 years – so by about 2030. This pushes out to 19 years at a linear rate of emission reduction, so net-zero emissions would need to be achieved by about 2040.

Read more: Who's who in Glasgow: 5 countries that could make or break the planet's future under climate change

Australia’s Fair Share

These calculations relate to the global effort. So what is Australia’s fair contribution? In 2014 the Climate Change Authority, a panel of government-appointed experts, addressed this question.

The Climate Change Authority recommended Australia’s emissions be reduced by between 45% and 65% on 2005 levels by 2030. This approach generously allocated 0.97% of the remaining global carbon budget to Australia even though our population is about 0.33% of the global total.

Applying the same method today to estimate Australia’s share of the remaining carbon budget, we calculate Australia needs to achieve net-zero emissions within 16 years – around 2038 – and reduce emissions by 50% to 75% by 2030.

So any way you cut it, net-zero emissions by 2050 is too late.

And we must not forget, Australia is a wealthy country, with one of the highest per capita emission rates. That means doing our “fair share” should entail emissions reductions greater than the global average.

An emissions target for Australia of 75% below 2005 levels by 2030, and reaching net-zero emissions by 2035, is consistent with global efforts to limit warming to 1.8℃. There’s no doubt achieving a 75% reduction in Australia’s emissions by 2030 would be challenging, but this target is both scientifically robust and ethically responsible.

The World Is Watching

COP26 in Glasgow will be a defining moment in the global response to climate change. In the words of COP President-Designate Alok Sharma:

The choices we make in the year ahead will determine whether we unleash a tidal wave of climate catastrophe on generations to come. But the power to hold back that wave rests entirely with us.

More than 100 countries have pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, and the G7, consisting of the world’s largest developed economies, has committed to at least halving its emissions this decade. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that for all the ambition, a United Nations report released last month points to a 16% increase in emissions by 2030 compared to 2010. This would lead to about 2.7℃ warming by 2100.

Adding to the bad news, Australia is the worst-performing of all developed countries when it comes to meaningful climate action.

We ranked dead last in 2021 for action taken to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions in the UN Sustainable Development Report. The latest report from the Climate Council also ranks Australia last, compared to 30 other wealthy developed countries, for both climate policy/action, and fossil fuel dependence.

The list of poor rankings could go on, but there’s no doubt Australia is viewed as a global climate pariah.

Repairing The Damage

To turn this miserable position around, Australia should be going to Glasgow with a far stronger emissions-reduction target for 2030. This should be backed by a national plan to rapidly decarbonise our electricity and transport sectors, absorb more carbon in the landscape and support the transition of communities to new clean industries.

It goes without saying Australia must commit to ending public funding for coal, oil and gas – both their use and extraction. And we must say no to any new fossil fuel developments.

Australia must also make a new commitment to support climate action in developing countries because if poorer nations don’t also make the low-carbon transition, the whole world suffers. As a first step, Australia should follow the United States in doubling its current climate finance contribution, which would bring AUstralia’s contribution to least A$3 billion over 2021-2025.

A week before a major international meeting aimed at saving life on Earth, the Morrison government has apparently seen the light.

Granted, it’s a start. But the new targets are less than the bare minimum required. The government’s last-minute jump on the bandwagon is not quite the Damascene conversion it would have the public believe.

Will Australia’s stumbling, last-minute dash towards climate respectability be well-received in Glasgow? Don’t hold your breath.![]()

Lesley Hughes, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University and Will Steffen, Emeritus Professor, Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How much do marine heatwaves cost? The economic losses amount to billions and billions of dollars

Marine heatwaves are catastrophic impacts of climate change many of us are already familiar with. But how much do they cost society?

During marine heatwaves, ocean temperatures can become so high that many species become stressed, or die. Critical coastal habitats, such as seagrass meadows, corals and kelp forests, can die out, limiting their natural capacity to store carbon dioxide and disrupting fisheries and tourism.

Until now, we’ve not understood how much society loses during marine heatwaves. This is what our new research, published in Science, sought to find out.

We looked at 34 marine heatwaves worldwide, and found one event in 2016 in southern Chile cost more than US$800 million (A$1.07 billion) in direct losses to aquaculture (cultivating aquatic plants and animals for food). Another heatwave in Shark Bay, Western Australia, resulted in US$3.1 billion (A$4.14 billion) per year in indirect losses, as a result of lost carbon storage when seagrass beds were impacted.

As world leaders prepare to meet for COP26 in Glasgow, they must keep these intensifying marine heatwaves front of mind. They are not only a stress test for the ocean’s ecosystems, but also for millions of people who rely on them – and who are already suffering.

Marine Heatwaves Can Strike Anywhere

Marine heatwaves are defined as prolonged periods of very warm surface water temperatures that commonly last for weeks to months. Climate change has caused surface waters to warm at an average rate of 0.15℃ per decade over the past 40 years, leading to longer and more frequent heatwaves. Eight of the ten most severe events ever recorded took place in the past decade alone.

They can occur in any ocean for two reasons: heat entering the ocean via the atmosphere, or via ocean currents that bring warmer waters. When both processes occur together, they lead to heatwaves with even higher temperatures.

Heatwaves lead to major economic losses because they modify the ocean’s “ecosystem services” – the range of benefits healthy marine ecosystems provide to humans.

For example, fishers, aquaculturalists, and tourism operators all rely on “foundation” species – such as corals, kelps and seagrasses – because they provide habitat for a range of creatures.

When a marine heatwave destroys a foundation species, like we’ve seen in the recent, back-to-back coral bleaching events in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, then the whole ecosystem suffers, and the knock-on socio-economic consequences can run into billions of dollars.

Billions Of Dollars Of Damage

Fortunately, extreme events occur rarely in any single location. This, however, means learning about them can be slow.

So to gain insight into these increasingly frequent disasters, we collated information on 34 marine heatwaves across all major ocean basins over the past 25 years. We found most resulted in declines in fish catch, the destruction of kelp forests or seagrass meadows, or led to mass deaths of wildlife.

The longest-lived marine heatwave in the North Pacific, known as “the Blob”, persisted for over one year in 2015 and 2016, and raised average water temperatures along the United States west coast by 2-4℃.

It led to declines in fish catch, killed thousands of seabirds and marine mammals, and saw new species move toward the pole where the water was uncharacteristically warm. Harmful algal blooms led to the closure of the Dungess Crab Fishery – a US$97 million (A$130 million) loss for fishers.

Heatwaves also limit ecosystem services relating to carbon sequestration. Seagrass, kelp, coral and other habitat-forming species store carbon dioxide in the same way forests do on land. When they die, this carbon is released.

Shark Bay in Western Australia is home to one of the world’s largest seagrass meadows, at 4,000 square kilometres. In 2011, 34% of this seagrass died after a marine heatwave struck, releasing between 2 and 9 billion tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere over the following three years. The indirect economic loss from this event was estimated to be US$3.1 billion (A$4.14 billion) per year, based on the ecosystem service value of the seagrass’ capacity to store carbon.

This heatwave also wiped out kelp habitats along 100km of WA’s coast. Abalone, scallop and swimmer crab fisheries were forced to close, and fish species that relied on the kelp declined. Local businesses that supported fishers also lost revenue.

Read more: A marine heatwave has wiped out a swathe of WA's undersea kelp forest

While most impacts have been negative, we did note some short-term positive benefits from dramatically warmer waters. This is mainly due to new species following the warmer water to a region, resulting in more fishing opportunities.

For example, a 2012 marine heatwave in the Gulf of Maine, US, resulted in a US$38 million loss in a lobster fishery. This was due to an unexpected influx of lobsters that created a glut of product, and a rapid drop in the price lobster fishers received for their catches.

However, a second marine heatwave in 2016 saw the same lobster fishery earn an extra US$103 million, as a result of experience gained since the first, which allowed them to capitalise on the higher lobster catch rates.

We Must Learn To Cope

Our research makes conservative estimates – the true costs of marine heatwaves are likely to be much greater, because many socioeconomic effects likely remain unknown and under reported. This is particularly true for regions with limited scientific capacity, and where marine heatwaves have not been widely studied, such as in the Indian Ocean.

As with every climate-related threat, reducing greenhouse gases and a commitment to the Paris Agreement is the best, long-term solution. However, given we’ve already seen a 50% increase in marine heatwave days since 1925, we will undoubtedly see heatwaves intensify further, even if the world succeeds in holding average global warming to between 1.5 and 2℃.

So, we must find a way to prepare for more frequent and intense marine heatwaves to cope better when they hit.

Our current efforts are in forecasting extreme events. Currently, scientists who forecast these events can give only less than a week’s notice for when a heatwave is likely to strike.

Read more: We just spent two weeks surveying the Great Barrier Reef. What we saw was an utter tragedy

Hopefully, with enough notice, fishers may relocate or prepare for harvesting new species, aquaculture businesses can harvest early, and conservation managers may prepare for an influx of hungry animals. And perhaps, in future, coral reef managers may to deploy new technologies to shade and cool critical reefs.

Developing responses like these to help us live with marine heatwaves must be supported by awareness of current events. If climate change mitigation is slow and the planet heats beyond the crucial 2℃ temperature rise, adaptation will be even more important.![]()