inbox and environment news: Issue 517

November 7 - 13, 2021: Issue 517

Manly Stormwater

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Pittwater Nature No:8

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Pittwater Nature No:8

Native Bees - Community Webinars

Avalon Preservation Association AGM 2021

Speaker: Angus Gordon OAM

“Global warming, is it real?”

The 2021 Annual General Meeting for Avalon Preservation Association (APA) will be held from 7.00pm on Thursday 11 November 2021 at the Avalon Beach surf life saving club.

Our special guest speaker is Angus Gordon OAM. Angus will talk on the controversial and very timely topic “Global Warming, Is it Real?”

Angus was General Manager of Pittwater Council from 1996 to 2005. He has a Master’s degree in Water and Coastal Engineering. In 2018 Angus received the Medal of the Order of Australia for “service to environmental management and planning, and to the community”.

Over the past 40 years he has undertaken projects in all states of Australia and in a number of overseas countries in coastal engineering, coastal zone management and flood management and engineering. Angus has served as a UN expert and was tasked with the development of the NSW Coastal Protection Act.

Angus Gordon OAM. AJG pic.

Speaker: Angus Gordon OAM

“Global warming, is it real?”

The 2021 Annual General Meeting for Avalon Preservation Association (APA) will be held from 7.00pm on Thursday 11 November 2021 at the Avalon Beach surf life saving club.

Our special guest speaker is Angus Gordon OAM. Angus will talk on the controversial and very timely topic “Global Warming, Is it Real?”

Angus was General Manager of Pittwater Council from 1996 to 2005. He has a Master’s degree in Water and Coastal Engineering. In 2018 Angus received the Medal of the Order of Australia for “service to environmental management and planning, and to the community”.

Over the past 40 years he has undertaken projects in all states of Australia and in a number of overseas countries in coastal engineering, coastal zone management and flood management and engineering. Angus has served as a UN expert and was tasked with the development of the NSW Coastal Protection Act.

Due to the current health situation, APA will hold the AGM strictly in line with the NSW Public Health Orders in force at the time. This may restrict the number of members and guests able to attend and guests may need to check in with a QR code, wear facemasks and show that they have been fully vaccinated.

Wild Pollinator Count: November 14-21

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Draft Marine Park Management Plan Released

Home Gardeners In Sydney Basin To Help Protect Local Fruit And Vegetable Production: Get Your Free Sticky Trap

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

Winning Hawkesbury Photos Make 2022 Calendar

Torres Strait Peoples Suing Australian Government Over Climate Change Inaction

Illegal Bike Track At Mount Keira To Be Closed And Rehabilitated

NSW Land Management Report 2018-2020

Land Clearing In NSW Must End For Australia To Meet Its New COP26 Deforestation Pledge

Return Of Indigenous Farming, Foods And Fire Could Help Regenerate Australia

- Ensure a seed or tree is planted on your behalf where it’s needed most through one of our on-ground projects. Trees/forests are being planted across NSW, QLD and Victoria.

- Help make a difference and restore vital homes for our wildlife and establish a network of habitat corridors.

- Support our advocacy work for stronger laws and protections for koalas and the places they call home.

- Get first access to stories straight from-the-field about how your support is helping to Regenerate Australia.

Billions Of Dollars From Overseas Is Helping Exploit Australian Fossil Fuels

One Year On: Royal Commission Recommendations Left Burning

PM Presented An Unbelieved Climate Con To COP26: Climate Council

Legislating Emissions Targets Would Be A Step Forward For NSW

$40 Million Clean Technology Grants Open

- electrification and energy systems

- primary industry and land management

- powerfuels, including hydrogen.

Wildlife First Response Training For Firefighters

‘Bunyip Bird’ Takes Centre Stage At 2022 Australian Bittern Summit

- Coleambally Irrigation Cooperative Limited

- Murray Irrigation Limited

- Murrumbidgee Irrigation Limited

- Commonwealth Environmental Water Office

- Murray Darling Basin Authority

- Agrifutures

- Rice Growers Association of Australia

- Murray Darling Wetlands Working Group

- Charles Sturt University

- Yenda Producers

- Department of Planning, Industry and Environment

- Leeton Shire Council.

.jpg?timestamp=1636193272929)

Western Sydney Wildlife Crossing A Success

“The most frequent visitors are a local population of Sugar Gliders, who are using the crossing to travel from Surveyors Creek into Mulgoa Nature Reserve.

“The most frequent visitors are a local population of Sugar Gliders, who are using the crossing to travel from Surveyors Creek into Mulgoa Nature Reserve.St John’s Wort Spreading In Warrumbungle Shire

ECNT And EDO Take Keith Pitt’s Fracking Grants To Federal Court

Fracking Companies Targeting Polluting Shale Oil On Lake Eyre Basin Floodplains

Early Decision Opposes Bundaberg Coal Mine Proposal

Rylstone Residents Celebrate Recommendation Against Releasing Their Backyard To New Coal Mining

Dial-A-Dump Fined For Tracking Sediment From Eastern Creek Site

Failure to stop dirt and sediment from allegedly being tracked from an industrial site out onto Western Sydney roadways has resulted in Dial-a-Dump (EC) Pty Ltd receiving $30,000 in fines from the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA).

Failure to stop dirt and sediment from allegedly being tracked from an industrial site out onto Western Sydney roadways has resulted in Dial-a-Dump (EC) Pty Ltd receiving $30,000 in fines from the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA).Warragamba Dam Raising Project EIS On Public Exhibition

NSW Government Plan To Revitalise Peat Island And Mooney Mooney Released

- Nearly 270 new homes at Mooney Mooney to deliver more housing supply,

- Retention of nine unlisted historical buildings on the island, and four on the mainland, to be restored and used for new community and commercial opportunities,

- New retail and café or restaurant opportunities,

- Approximately 9.65 hectares of open space, including opportunities for walking and cycling tracks, parklands and recreational facilities,

- Retention of the chapel and surrounding land for community use, and

- 10.4 hectares of bushland dedicated as a conservation area.

COP26: it’s half-time at the crucial Glasgow climate change summit – and here’s the score

The first week of the United Nations climate talks in Glasgow are drawing to a close. While there’s still a way to go, progress so far gives some hope the Paris climate agreement struck six years ago is working.

Major powers brought significant commitments to cut emissions this decade and pledged to shift toward net-zero emissions. New coalitions were also announced for decarbonising sectors of the global economy. These include phasing out coal-fired power, pledges to cut global methane emissions, ending deforestation and plans for net-zero emissions shipping.

The two-week summit, known as COP26, is a critical test of global cooperation to tackle the climate crisis. Under the Paris Agreement, countries are required, every five years, to produce more ambitious national plans to reduce emissions. Delayed one year by the COVID pandemic, this year is when new plans are due.

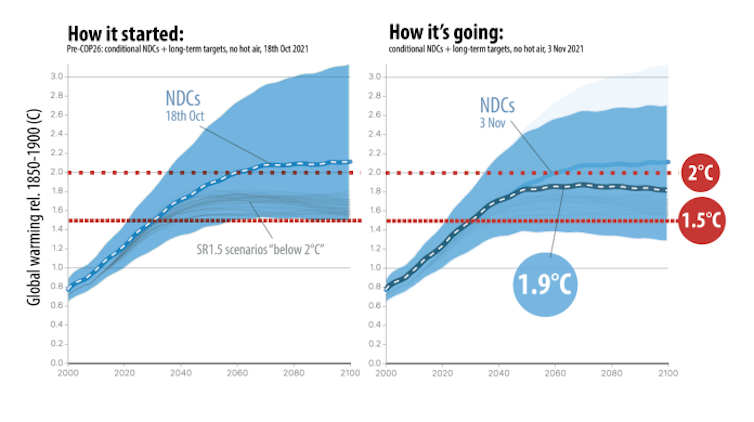

Pledges made at the summit so far could start to bend the global emissions curve downwards. Credible projections from an expert team, including Professor Malte Meinshausen at the University of Melbourne, suggest if new pledges are fully funded and met, global warming could be limited to to 1.9℃ this century. The International Energy Agency came to a similar conclusion.

This is real progress. But the Earth system reacts to what we put in the atmosphere, not promises made at summits. So pledges need to be backed by finance, and the necessary policies and actions across energy and land use.

A significant ambition gap on emissions reduction also remains, and more climate action is needed this decade to avoid catastrophic warming. Achieving necessary emissions reductions by 2030 will be a key focus of the second week of the Glasgow talks, especially as global emissions are projected to rebound strongly in 2021 (after the drop induced last year by COVID-19).

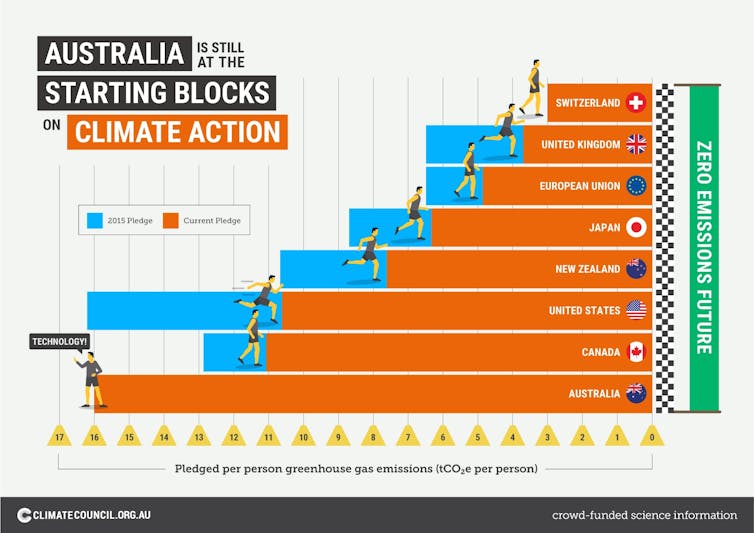

For its part, Australia contributed virtually nothing to global efforts in Glasgow. Alone among advanced economies, Australia set no new target to cut emissions this decade. If anything, this week added to Australia’s reputation as a member of a small and isolated group of countries - with the likes of Saudi Arabia and Russia - resisting climate action.

Global Momentum: What Did Major Powers Bring To Glasgow?

Since the last UN climate summit we’ve seen a worldwide surge in momentum toward climate action. More than 100 countries - accounting for more than two-thirds of the global economy - have set firm dates for achieving net-zero emissions.

Perhaps more importantly, in the lead up to the Glasgow summit the world’s advanced economies - including the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Japan, Canada, South Korea and New Zealand - all strengthened their 2030 targets. The G7 group of countries pledged to halve their collective emissions by 2030.

Major economies in the developing world also brought new commitments to COP26. China pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060 and strengthened its 2030 targets. It now plans to peak emissions by the end of the decade.

This week India also pledged to achieve net-zero by 2070 and ramp up installation of renewable energy. By 2030, half of India’s electricity will come from renewable sources.

The opening days of COP26 also saw a suite of new announcements for decarbonising sectors of the global economy. The UK declared the end of coal was in sight, as it launched a new global coalition to phase out coal-fired power.

More than 100 countries signed on to a new pledge to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030. More than 120 countries also promised to end deforestation by 2030.

The US also joined a coalition of countries that plans to achieve net-zero emissions in global shipping.

But this week the developed world fell short of fulfilling a decade-old promise - to deliver US$100 billion each year to help poorer nations deal with climate impacts.

Fulfilling commitments on climate finance will be critically important for building trust in the talks. For its part, Australia pledged an additional A$500 million in climate finance to countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific – a figure well short of Australia’s fair share of global efforts. Australia also refused to rejoin the Green Climate Fund.

Missing The Moment: The Australian Way

While the rest of the world is getting on with the race to a net-zero emissions economy, Australia is barely out of the starting blocks. Australia brought to Glasgow the same 2030 emissions target that it took to Paris six years ago - even as key allies pledged much stronger targets.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison arrived with scant plans to accompany his last-minute announcement on net-zero by 2050. The strategy titled The Australian Way, which comprised little more than a brochure, failed to provide a credible pathway to that target. It was met with derision across the world.

On the way to Glasgow, at the G20 leaders meeting in Rome, Australia blocked global momentum to reduce emissions by resisting calls for a phase out of coal power. Australia also refused to sign on to the global pledge on methane.

Worse still, Australia is using COP26 to actively promote fossil fuels. Federal Energy Minister Angus Taylor says the summit is a chance to promote investment in Australian gas projects, and Australian fossil fuel company Santos was prominently branded at the venue’s Australia Pavilion.

The federal government is promoting carbon capture and storage as a climate solution, despite it being widely regarded as a licence to prolong the use of fossil fuels. The technology is also eye-wateringly expensive and not yet proven at scale.

The Closing Stretch

Week one in Glasgow has delivered more climate action than the world promised in Paris six years ago. However, the summit outcomes still fall well short of what is required to limit warming to 1.5℃. Attention will now turn to negotiating an outcome to further increase climate ambition this decade.

Vulnerable countries have proposed countries yet to deliver enhanced 2030 targets be required to come back in 2022, well before COP27, with stronger targets to cut emissions.

This week, the United States rejoined the High Ambition Coalition, a group of countries from across traditional negotiating blocs in the UN climate talks. Led by the Marshall Islands, the group was crucial in securing the 2015 Paris Agreement.

In Glasgow, this coalition is pressing for an outcome that will keep the world on track to limiting warming to 1.5℃.

But significant differences persist between the US and China. Many developing countries want to see more commitment to climate finance from wealthy nations before they will pledge new targets. Can consensus be reached in Glasgow? We’ll be watching the negotiations closely next week to find out.

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute and Climate Council researcher, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

5 major heatwaves in 30 years have turned the Great Barrier Reef into a bleached checkerboard

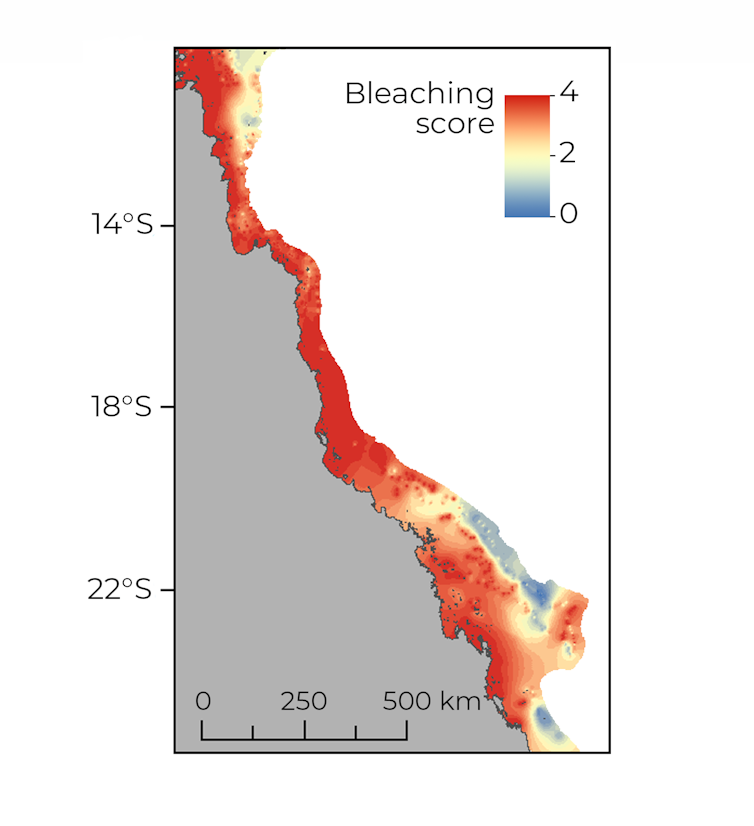

Terry Hughes, James Cook University and Sean Connolly, Smithsonian InstitutionJust 2% of the Great Barrier Reef remains untouched by bleaching since 1998 and 80% of individual reefs have bleached severely once, twice or three times since 2016, our new study reveals today.

We measured the impacts of five marine heatwaves on the Great Barrier Reef over the past three decades: in 1998, 2002, 2016, 2017 and 2020. We found these bouts of extreme temperatures have transformed it into a checkerboard of bleached reefs with very different recent histories.

Whether we still have a functioning Great Barrier Reef in the decades to come depends on how much higher we allow global temperatures to rise. The bleaching events we’ve already seen in recent years are a result of the world warming by 1.2℃ since pre-industrial times.

World leaders meeting at the climate summit in Glasgow must commit to more ambitious promises to drastically cut greenhouse gas emissions. It’s vital for the future of corals reefs, and for the hundreds of millions of people who depend on them for their livelihoods and food security.

Coral In A Hotter Climate

The Great Barrier Reef is comprised of more than 3,000 individual reefs stretching for 2,300 kilometres, and supports more than 60,000 jobs in reef tourism.

Under climate change, the frequency, intensity and scale of climate extremes is changing rapidly, including the record-breaking marine heatwaves that cause corals to bleach. Bleaching is a stress response by overheated corals, where they lose their colour and many struggle to survive.

If all new COP26 pledges by individual countries are actually met, then the projected increase in average global warming could be brought down to 1.9℃. In theory, this would put us in line with the goal of the Paris Agreement, which is to keep global warming below 2℃, but preferably 1.5℃, this century.

However, it is still not enough to prevent the ongoing degradation of the world’s coral reefs. The damage to coral reefs from anthropogenic heating so far is very clear, and further warming will continue to ratchet down reefs throughout the tropics.

Read more: Not declaring the Great Barrier Reef as 'in danger' only postpones the inevitable

Ecological Memories Of Heatwaves

Most reefs today are in early recovery mode, as coral populations begin to re-build since they last experienced bleaching in 2016, 2017 and 2020. It takes about a decade for a decent recovery of the fastest growing corals, and much longer for slow-growing species. Many coastal reefs that were severely bleached in 1998 have never fully recovered.

Each bleaching event so far has a different geographic footprint. Drawing upon satellite data, we measured the duration and intensity of heat stress that the Great Barrier Reef experienced each summer, to explain why different parts were affected during all five events.

The bleaching responses of corals differed greatly in each event, and was strongly influenced by the recent history of previous bleaching. For this reason, it’s important to measure the extent and severity of bleaching directly, where it actually occurs, and not rely exclusively on water temperature data from satellites as an indirect proxy.

We found the most vulnerable reefs each year were the ones that had not bleached for a decade or longer. On the other hand, when successive episodes were close together in time (one to four years apart), the heat threshold for severe bleaching increased. In other words, the earlier event had hardened regions of the Great Barrier Reef to subsequent impacts.

For example, in 2002 and 2017, it took much more heat to trigger similar levels of bleaching that were measured in 1998 and 2016. The threshold for bleaching was much higher on reefs that had experienced an earlier episode of heat stress.

Similarly, southern corals, which escaped bleaching in 2016 and 2017, were the most vulnerable in 2020, compared to central and northern reefs that had bleached severely in previous events.

Many different mechanisms could generate these historical effects, or ecological memories. One is heavy losses of the more heat-susceptible coral species during an earlier event – dead corals don’t re-bleach.

Read more: We just spent two weeks surveying the Great Barrier Reef. What we saw was an utter tragedy

Nowhere Left To Hide

Only a single cluster of reefs remains unbleached in the far south, downstream from the rest of the Great Barrier Reef, in a small region that has remained consistently cool through the summer months during all five mass bleaching events. These reefs lie at the outer edge of the Great Barrier Reef, where upwelling of cool water may offer some protection from heatwaves, at least so far.

In theory, a judiciously placed network of well-protected, climate-resistant reefs might help to repopulate the broader seascape, if greenhouse gas emissions are curtailed to stabilise temperatures later this century.

But the unbleached southern reefs are too few in number, and too far away from the rest of the Great Barrier Reef to produce and deliver sufficient coral larvae, to promote a long-distance recovery.

Instead, future replenishment of depleted coral populations is more likely to be local. It would come from the billions of larvae produced by recovering adults on nearby reefs that have not bleached for a while, or by corals inhabiting reef in deeper waters which tend to experience less heat stress than those living in shallow water.

Read more: 'This situation brings me to despair': two reef scientists share their climate grief

Future recovery of corals will increasingly be temporary and incomplete, before being interrupted again by the inevitable next bleaching event. Consequently, the patchiness of living coral on the Great Barrier Reef will increase further, and corals will continue to decline under climate change.

Our findings make it clear we no longer have the luxury of studying individual climate-related events that were once unprecedented, or very rare. Instead, as the world gets hotter, it’s increasingly important to understand the effects and combined outcomes of sequences of rapid-fire catastrophes.![]()

Terry Hughes, Distinguished Professor, James Cook University and Sean Connolly, Research Biologist, Smithsonian Institution

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia’s refusal to sign a global methane pledge exposes flaws in the term ‘net-zero’

At the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow, more than 90 nations signed a global pledge led by the United States and United Kingdom to cut methane emissions. However, Australia was not among them.

China, Russia, India and Iran also declined to sign the pledge, which aims to slash methane emissions by 30% before 2030.

Methane is emitted in coal and gas production, from livestock and other agricultural activity, and when organic waste breaks down in landfill.

Almost half of Australia’s annual methane emissions come from the agriculture sector. Defending the federal government’s decision, Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor said Australia had pledged net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and would not set specific targets for each sector.

Days out from COP26, National Party leader Barnaby Joyce had claimed signing the pledge would be a disaster for coal mining and agriculture, saying “the only way you can get your 30% by 2030 reduction in methane on 2020 levels would be to grab a rifle and go out and start shooting your cattle”.

Australia’s position on the pledge is inconsistent with methane reductions the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says are required to keep Earth below 1.5℃ warming this century.

The debate also highlights how the shorthand phrase “net-zero emissions” conceals and distorts the real challenges in avoiding dangerous climate change.

It focuses attention on the wrong time frame for action – the next decade is far more important for climate action than 2050. It also addresses the means of action – emissions reduction – rather than the desired goal, which is to avoid dangerous climate change.

And importantly, simply through delaying action, the world could feasibly reduce emissions to net-zero by 2050, but still fail to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement – keeping average global temperature rise below either 1.5℃ or 2℃ this century.

Read more: COP26: a global methane pledge is great – but only if it doesn't distract us from CO₂ cuts

Net-Zero Is Both Too Much, And Not Enough

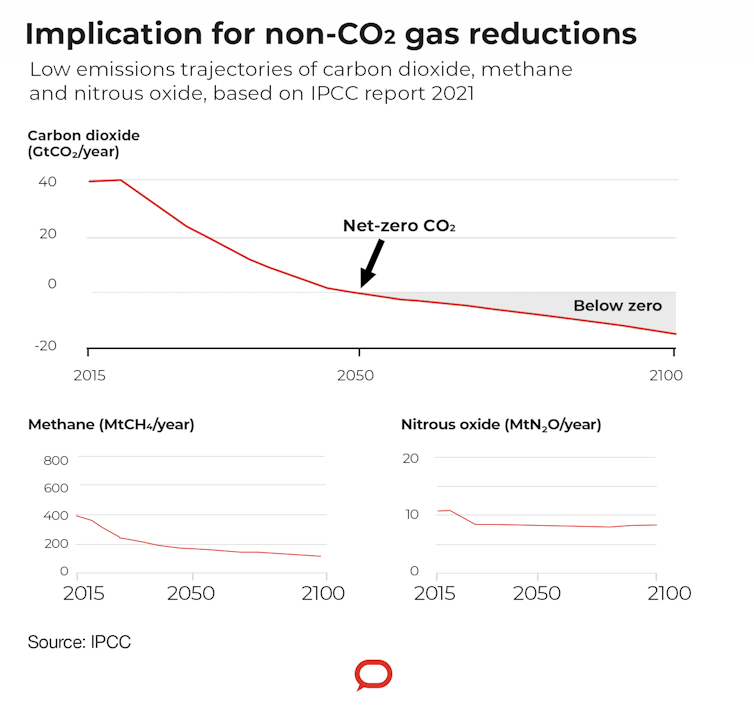

The IPCC report released in August painted a clear picture of how different trajectories for various greenhouse gases translate to global temperature increases.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions last a very long time in the atmosphere so they accumulate. Consequently, net CO₂ emissions need to decline sharply as soon as possible if we’re to limit temperatures to 1.5℃ or 2℃ above pre-industrial levels.

However, CO₂ emissions not only need to reach net-zero – the IPCC says CO₂ emissions need to go “net-negative”. This will require a massive scaling up of methods and technologies to remove existing CO₂ in the atmosphere.

In other words, when it comes to CO₂, net-zero is not enough. It is a way point, not the end point.

So how do we remove CO₂ from the atmosphere? Some methods, such as mass tree planting, are already widely implemented. Some are difficult to implement at scale, such as substantial increases in soil carbon.

Others are in the exploratory stages including incorporating captured CO₂ into building products and high-value materials or in the ocean.

Each option has advantages, disadvantages and limits. The “net-zero by 2050” terminology obscures this complexity. It also conceals the need for crucial discussions about feasibility, governance and support for research and development that’s needed now.

Meanwhile, the situation is quite different for shorter-lived gases such as methane and nitrous oxide. In those cases, going all the way to net-zero is not needed to meet the Paris goals.

According to the IPCC report, an illustrative scenario consistent with 1.5℃ warming would involve methane emission reductions of about 30% by 2030, 50% by 2050 and just over 60% by 2100.

This is consistent with the global methane pledge signed at COP26 overnight. For nitrous oxide, the illustrative reductions would be about 30% by 2050.

So, for methane and nitrous oxide, net-zero is too much.

Targets Based On Science

It should be noted, to keep temperature rise to 1.5℃, there are many possible combinations of emission-reduction trajectories for various greenhouse gases. The extent to which CO₂, methane or nitrous oxide is reduced is interchangeable and the final mix will be a function of political decisions.

A clear and integrated assessment of the economic, environmental and social consequences of different emission-reduction pathways is needed to inform those decisions. Without that, inefficient and inequitable economic responses may result.

For example, methane (from livestock) and nitrous oxide (from fertiliser use) make up a high proportion of agriculture emissions. But options for completely stopping these emissions are limited.

Farmers could offset their emissions by planting trees or rehabilitating vegetation on their properties to increase carbon stores. But this would prevent them from selling those emissions reductions on carbon markets, thus removing a potential source of farm income.

So an economy-wide target of net-zero for all key greenhouse gases might mean agriculture must make far more effort in emissions reduction, at much greater cost, than other sectors which largely emit CO₂ and where decarbonisation options are more readily available.

New Zealand has recognised this, and treats agricultural emissions separately.

Carving agriculture out of national emissions-reduction goals would place a greater requirement to act onto other sectors. For example, emission reductions in the transport sector may have to be greater than otherwise, to compensate for the lack of progress in agriculture.

But is isolating agriculture from emission reductions necessary? A recent study assessed new emission reduction options for livestock, including several approaches that together may reduce emissions at the rate required by the methane pledge. They involve more efficient production, technological advances, changes in demand for livestock-related products and land-based carbon storage.

These are approaches already being adopted by industry groups and farmers.

Towards ‘Paris-Aligned’

Targets for methane and nitrous oxide reductions should be set using the IPCC science – and don’t have to be set at net-zero. That would leave sectors emitting these gases with a feasible (but still challenging) pathway to reducing emissions in line with the Paris goals.

And where appropriate, we should start describing effective climate action as being “Paris-aligned”. Clearly, over-use of the term “net-zero emissions” misdirects attention from where it’s needed.

Read more: The clock is ticking on net-zero, farmers must not get a free pass ![]()

Mark Howden, Director, ANU Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP26: global deforestation deal will fail if countries like Australia don’t lift their game on land clearing

At the Glasgow COP26 climate talks overnight, Australia and 123 other countries signed an agreement promising to end deforestation by 2030.

The declaration’s signatories, which include global deforestation hotspots such as Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have committed to:

working collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 while delivering sustainable development and promoting an inclusive rural transformation.

This declaration should be welcomed for recognising how crucial forest loss and land degradation are to addressing climate change, biodiversity decline and sustainable development.

But there have been many such declarations before, and it’s hard to feel excited about yet another one.

What really matters is changing policy domestically; if countries don’t change what they are doing at home to bring emissions from fossil fuels to zero and restore degraded lands, declarations like this are meaningless.

Read more: Want to beat climate change? Protect our natural forests

The Good Parts

The declaration does a good job of joining up interrelated issues that for too long have been treated as separate problems.

Signatories say they will:

emphasise the critical and interdependent roles of forests of all types, biodiversity and sustainable land use in enabling the world to meet its sustainable development goals; to help achieve a balance between anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and removal by sinks; to adapt to climate change; and to maintain other ecosystem services.

Biodiversity is key to forest conservation and sustainable land use.

From there, the signatories promise to:

reaffirm our respective commitments, collective and individual, to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, the Sustainable Development Goals; and other relevant initiatives.

To see commitments under several UN declarations recognised in one place is somewhat of a breakthrough; forests, biodiversity and land-use are often siloed despite the critical links in dealing with these issues.

It is also promising to see recognition that conserving existing forests and other terrestrial ecosystems is the priority, and signatories committing to accelerate their restoration (as opposed to just planting new trees).

A vast body of research shows planting new trees as a climate action pales in comparison to protecting existing forests. As I have written before,

restoring degraded forests and expanding them by 350 million hectares will store a comparable amount of carbon as 900 million hectares of new trees […] Forest ecosystems (including the soil) store more carbon than the atmosphere. Their loss would trigger emissions that would exceed the remaining carbon budget for limiting global warming to less than the 2℃ above pre-industrial levels, let alone 1.5℃, threshold.

Once intact forests are gone, we can’t regain the carbon lost. It is known as “irrecoverable carbon”. So protecting existing forests is the top priority, especially given the critical time frame we are in now to keep climate change under the 1.5℃ or even 2℃ thresholds.

The declaration also mentions trade, promising to:

facilitate trade and development policies, internationally and domestically, that promote sustainable development, and sustainable commodity production and consumption, that work to countries’ mutual benefit, and that do not drive deforestation and land degradation

Here, we are starting to get to the real drivers of deforestation. For a long time, there has been too much focus on local drivers of deforestation including local communities. But research shows the leading drivers of deforestation are internationally traded agricultural commodities such as beef, soy, palm oil and timber.

The overall rate of commodity-driven deforestation has not declined since 2001. We can’t tackle forest loss without tackling the trade drivers behind it.

Read more: Deforestation: why COP26 agreement will struggle to reverse global forest loss by 2030

The Not-So-Good Parts

The main deficiency in the text is that not enough attention is paid to the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

It is mentioned the countries will “recognise” and “support” the rights of Indigenous peoples but many of these signatories do not have adequate – or, in some cases, any – legislation that actually recognises those rights.

Subjugation of these rights to national law has been a problem in previous international agreements.

The challenge in many countries is regulatory reform to bring national recognition of land, tenure and other collective rights into line with the internationally recognised rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The track records of some of these signatories bring into question what policy change they will be making back home to ensure this declaration isn’t just for show.

As a global land clearing hotspot, Australia will need to enact rapid policy change to bring its current practices in line with what it has signed on to. Australia remains the only developed nation on the list of global deforestation fronts. This is due to weakening land clearing legislation in New South Wales and Queensland, mostly for expansion of grazing lands.

As a signatory to this new declaration, Australia must strengthen land clearing laws, end native forest logging, and restore degraded ecosystems – just planting new trees will not get us there. Australia has the potential to restore large areas of degraded land. Experts have proposed how this could be done for relatively little investment.

The European Union has signed on too; it has been a global leader on developing trade policies designed to end illegal logging and reduce deforestation. But it recently backpedalled on its commitment to a program of forest governance and law enforcement in timber-producing countries that allow access to the EU timber market.

If they are serious about this declaration, the EU must reaffirm its commitment to partner countries to address illegal logging in traded timber.

In Brazil, the Bolsonaro government has been winding back previous legislation to recognise Indigenous peoples’ land rights. Deforestation rates have soared in the past few years. Perhaps the first action Brazil could take as a signatory to this declaration is to prioritise the landmark case (currently on hold) before Brazil’s Supreme Court to protect Indigenous land rights.

Ending Deforestation And Restoring Forests Is Not Enough

This is the latest in a series of similar declarations. A pledge made at COP24 in Katowice, the New York Declaration on Forests, and Sustainable Development Goal 15 (Life on Land) all include similar commitments to end deforestation by 2030 or earlier.

This week’s COP26 declaration ends with the importance of

pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5℃, noting that the science shows further acceleration of efforts is needed if we are to collectively keep 1.5℃ within reach.

The fact is, we won’t achieve this through ending deforestation and restoring forests. These efforts are critically needed to address biodiversity loss and rural sustainability, but for limiting warming to 1.5℃, fossil fuel emissions need to come down to zero – now.![]()

Kate Dooley, Research Fellow, Climate & Energy College, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Forests can’t handle all the net-zero emissions plans – companies and countries expect nature to offset too much carbon

Net-zero emissions pledges to protect the climate are coming fast and furious from companies, cities and countries. But declaring a net-zero target doesn’t mean they plan to stop their greenhouse gas emissions entirely – far from it. Most of these pledges rely heavily on planting trees or protecting forests or farmland to absorb some of their emissions.

That raises two questions: Can nature handle the expectations? And, more importantly, should it even be expected to?

We have been involved in international climate negotiations and land and forest climate research for years. Research and pledges from companies so far suggest that the answer to these questions is no.

What Is Net-Zero?

Net-zero is the point at which all the carbon dioxide still emitted by human activities, such as running fossil fuel power plants or driving gas-powered vehicles, is balanced by the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Since the world does not yet have technologies capable of removing carbon dioxide from air at any climate-relevant scale, that means relying on nature for carbon dioxide removal.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, global carbon dioxide emissions will need to reach net-zero by at least midcentury for the world to have even a small chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 F), an aim of the Paris climate agreement to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

The devil of net-zero, of course, lies in its apparent simplicity.

Nature’s Potential And Its Limits

Climate change is driven largely by cumulative emissions – carbon dioxide that accumulates in the atmosphere and stays there for hundreds to thousands of years, trapping heat near Earth’s surface.

Nature has received a great deal of attention for its ability to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in the biosphere, such as in soils, grasslands, trees and mangroves, via photosynthesis. It is also a source of carbon dioxide emissions through deforestation, land and ecosystem degradation and agricultural practices. However, the right kinds of changes to land management practices can reduce emissions and improve carbon storage.

Net-zero proposals count on finding ways for these systems to take up more carbon than they already absorb.

Researchers estimate that nature might annually be able to remove 5 gigatons of carbon dioxide from the air and avoid another 5 gigatons through stopping emissions from deforestation, agriculture and other sources.

This 10-gigaton figure has regularly been cited as “one-third of the global effort needed to stop climate change,” but that’s misleading. Avoided emissions and removals are not additive.

A new forests and land-use declaration announced at the UN climate conference in November also highlights the ongoing challenges in bringing deforestation emissions to zero, including illegal logging and protecting the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Stored Carbon Doesn’t Stay There Forever

Reaching the point at which nature can remove 5 gigatons of carbon dioxide each year would take time. And there’s another problem: High levels of removal might last for only a decade or so.

When growing trees and restoring ecosystems, the storage potential develops to a peak over decades. While this continues, it reduces over time as ecosystems become saturated, meaning large-scale carbon dioxide removal by natural ecosystems is a one-off opportunity to restore lost carbon stocks.

Carbon stored in the terrestrial biosphere – in forests and other ecosystems – doesn’t stay there forever, either. Trees and plants die, sometimes as a result of climate-related wildfires, droughts and warming, and fields are tilled and release carbon.

When taking these factors into consideration – the delay while nature-based removals scale up, saturation and the one-off and reversible nature of enhanced terrestrial carbon storage – another team of researchers found that restoration of forest and agricultural ecosystems could be expected to remove only about 3.7 gigatons of carbon dioxide annually.

Over the century, ecosystem restoration might reduce global average temperature by approximately 0.12 C (0.2 F). But the scale of removals the world can expect from ecosystem restoration will not happen in time to reduce the warming that is expected within the next two decades.

Nature In Net-Zero Pledges

Unfortunately there is not a great deal of useful information contained in net-zero pledges about the relative contributions of planned emissions reductions versus dependence on removals. There are, however, some indications of the magnitude of removals that major actors expect to have available for their use.

ActionAid reviewed the oil major Shell’s net-zero strategy and found that it includes offsetting 120 million tons of carbon dioxide per year through planting forests, estimated to require around 29.5 million acres (12 million hectares) of land. That’s roughly 45,000 square miles.

Oxfam reviewed the net-zero pledges for Shell and three other oil and gas producers – BP, TotalEnergies and ENI – and concluded that “their plans alone could require an area of land twice the size of the U.K. If the oil and gas sector as a whole adopted similar net zero targets, it could end up requiring land that is nearly half the size of the United States, or one-third of the world’s farmland.”

These numbers provide insight into how these companies, and perhaps many others, view net-zero.

Research indicates that net-zero strategies that rely on temporary removals to balance permanent emissions will fail. The temporary storage of nature-based removals, limited land availability and the time they take to scale up mean that, while they are a critical part of stabilizing the earth system, they cannot compensate for continued fossil fuel emissions.

This means that getting to net-zero will require rapid and dramatic reductions in emissions. Nature will be called upon to balance out what is left, mostly emissions from agriculture and land, but nature cannot balance out ongoing fossil emissions.

To actually reach net-zero will require reducing emissions close to zero.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage of COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

Amid a rising tide of climate news and stories, The Conversation is here to clear the air and make sure you get information you can trust. Read more of our U.S. and global coverage.![]()

Doreen Stabinsky, Professor of Global Environmental Politics, College of the Atlantic and Kate Dooley, Research Fellow, Climate & Energy College, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Can selective breeding of ‘super kelp’ save our cold water reefs from hotter seas?

Australia’s vital kelp forests are disappearing in many areas as our waters warm and our climate changes.

While we wait for rapid action to slash carbon emissions – including the United Nations climate talks now underway in Glasgow – we urgently need to buy time for these vital ecosystems.

How? By ‘future-proofing’ our kelp forests to be more resilient and adaptable to changing ocean conditions. Our recent trials have shown selectively bred kelp with higher heat tolerance can be successfully replanted and used in restoration.

This matters because these large seaweed species are the foundation of Australia’s Great Southern Reef, a vast but little-known temperate reef system and a global hotspot of biodiversity.

The reef’s kelp forests run along 8000 km of Australia’s southern coastline, from Geraldton in Western Australia to the Queensland border with New South Wales. These underwater forests support coastal food-webs and fisheries. Think of the famous mass-spawning of Australian Giant Cuttlefish off Whyalla, the rock lobster and abalone fisheries, or our iconic weedy and leafy seadragons.

Unfortunately, these seas are hotspots in the literal sense, with the nation’s southeast and southwest waters warming several times faster than the global average and suffering from some of the worst marine heatwaves recorded.

These increasing temperatures and other climate change impacts are devastating our kelp, including shrinking forests and permanent losses of golden kelp (Ecklonia radiata) on the east and west coasts, and staggering declines of the now-endangered giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) forests in Tasmania.

Read more: Australia's 'other' reef is worth more than $10 billion a year - but have you heard of it?

We Need Novel Measures To Buy Time For Climate Action

Australian researchers are leading the way to try to find ways of future-proofing our critical ocean ecosystems, such as kelp forests and coral reefs. In part, that’s because climate change is hitting our ecosystems early and hard.

Climate change is moving much faster than kelp species can adapt. In turn, that threatens all the species that rely on these forests, including us.

If climate change wasn’t happening, we could try to halt or reverse the losses of kelp forests by using traditional restoration methods. But in a world getting hotter and hotter, that is futile in many cases. Even if we slash carbon emissions soon, decades more warming are already locked in.

If we want to keep these forests of the sea alive, we must now consider cutting-edge methods to help kelp survive current and future ocean conditions while governments pursue the urgent goal of reducing emissions.

How To Future Proof An Underwater Forest

Together and separately, we’ve been exploring techniques to speed up the natural rate of evolution to boost kelp resilience. Along with other researchers, we’ve put several techniques to the test in the real world, with promising results. Others remain hypothetical.

At present, there are several broad approaches to future-proofing restoration work. These include:

Genetic rescue focuses on enhancing the genetic diversity of genetically compromised populations to boost their potential to adapt to future conditions. This involves planting and restoring a mix of kelp from disconnected populations of the same species. Improved genetic diversity can boost the ability of these forests to respond to change. We expect this approach to be especially useful in areas where climate change poses a limited threat at present.

Assisted gene flow strategies introduce naturally adapted or tolerant kelp individuals into threatened populations to increase their ability to survive specific threats, like hotter seas. This could help kelp forests in areas affected by climate change now or in the near future. In these situations, the genetic rescue technique could be counterproductive if the new genetic diversity introduced isn’t able to cope with the heat.

Selective breeding is a well-known agricultural technique, and can be used to identify the best kelp to use in these cases. In short, we try to identify kelp with naturally higher tolerance, and then use these as the basis for restoration efforts. These can be transplanted into ailing kelp forests. Trials are presently underway in Tasmania using giant kelp. Early results are exciting, with the largest ‘super kelp’ growing over 12 metres high a year after being planted.

In the future, we may have to explore more cutting-edge strategies to deal with the changing conditions. These include:

Genetic manipulation. This technique extends what is possible with selective breeding by directly manipulating genes to enhance the traits or characteristics that might further boost kelp’s ability to thrive in hotter waters.

Assisted expansion is when species with little chance of survival are relocated to better but novel locations, assuming these exist. This technique could also see new species of kelp being planted to replace existing species, guided by the need to protect the forest ecosystem as a whole, rather than save specific species.

Read more: Underwater health check shows kelp forests are declining around the world

Are These Approaches Ethical?

Each of these techniques – tested or untested – pose challenging ethical questions. That’s because we are not undertaking traditional conservation, where we work to restore a historic kelp ecosystem. Instead, we are modifying these ecosystems in the hope they can better cope with conditions at the extremes of their current survival limits.

That means we must move carefully, weighing potential downsides like genetic pollution and maladaptation (accidental poor adaptation to other stressors) against the probability of further kelp forest destruction from doing nothing.

Such future-proofing interventions could be well suited to areas already hit hard by severe kelp forest losses, those that will be threatened in the near future, or where kelp losses would be particularly damaging environmentally, socially, or economically.

What is certain is that communities that live and rely on our southern coasts must now talk about what they value from kelp forests, and how they want them to look and function into the future.

Our view is that traditional approaches focused on recreating previous ecosystems are likely to be increasingly challenging, given the rate and scale of ongoing disruption in our oceans.

It is crucial that we do not restore nostalgically for ocean conditions which are quickly changing, but instead, work to ensure the long-term survival of these spectacular underwater forests while we wait for rapid action to reduce carbon emissions.![]()

Cayne Layton, Postdoctoral fellow and lecturer, University of Tasmania and Melinda Coleman, Associate professor, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Global emissions almost back to pre-pandemic levels after unprecedented drop in 2020, new analysis shows

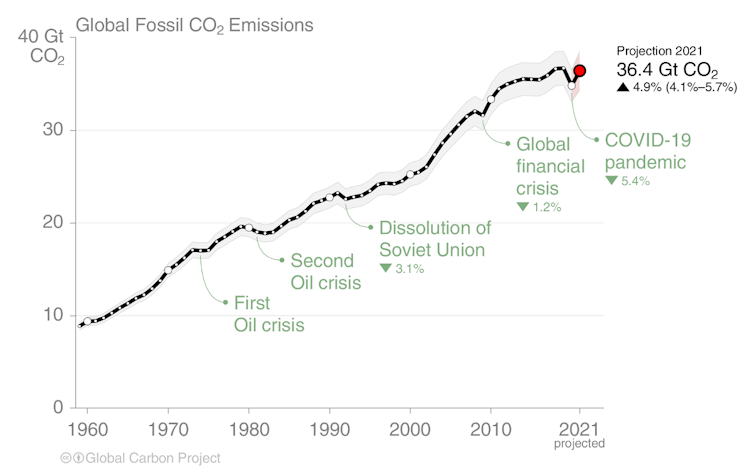

Global carbon dioxide emissions have bounced back after COVID-19 restrictions and are likely to reach close to pre-pandemic levels this year, our analysis released today has found.

The troubling finding comes as the COP26 climate talks continue in Glasgow in a last-ditch bid to keep dangerous global warming at bay. The analysis was undertaken by the Global Carbon Project, a consortium of scientists from around the world who produce, collect and analyse global greenhouse gas information.

The fast recovery in CO₂ emissions, following last year’s sharp drop, should come as no surprise. The world’s strong economic rebound has created a surge in demand for energy, and the global energy system is still heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

Most concerning is the long-term upward trends of CO₂ emissions from oil and gas, and this year’s growth in coal emissions, which together are far from trending towards net-zero by 2050.

The Global Emissions Picture

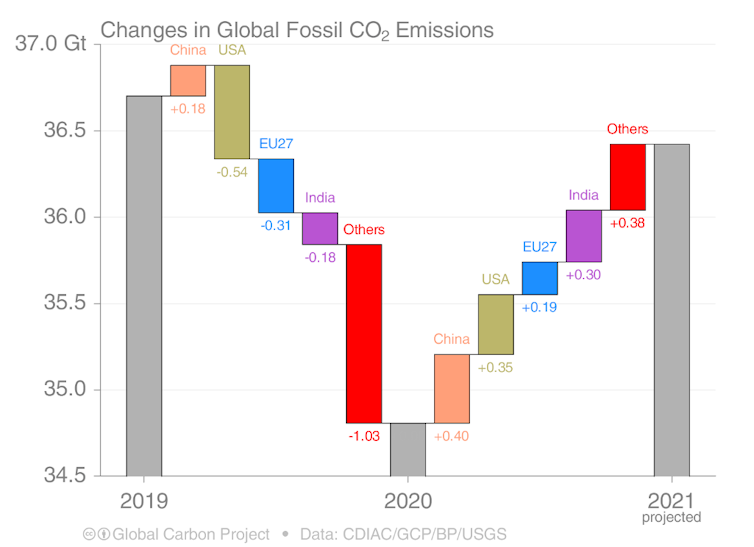

Global CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels dropped by 5.4% in 2020, compared to the previous year. But they are set to increase by about 4.9% above 2020 levels this year, reaching 36.4 billion tonnes. This brings them almost back to 2019 levels.

We can expect another 2.9 billion tonnes of CO₂ emissions this year from the net effect of everything we do to the land, including deforestation, degradation and re-vegetation.

This brings us to a total of 39.4 billion tonnes of CO₂ to be emitted by the end of this year.

The fast growth in emissions matches the corresponding large increase in energy demand as the global economy opens up, with the help of US$17.2 trillion in economic stimulus packages around the world.

CO₂ emissions from all fossil fuel types (coal, oil and natural gas) grew this year, with emissions from coal and natural gas set to grow more in 2021 than they fell in 2020.

Emissions from global coal use were declining before the pandemic hit in early 2020 but they surged back this year. Emissions from global gas use have returned to the rising trend seen before the pandemic.

CO₂ emissions from global oil use remain well below pre-pandemic levels but are expected to increase in coming years as road transport and aviation recover from COVID-related restrictions.

Nations Leading The Emissions Charge

Emissions from China have recovered faster than other countries. It’s among the few countries where emissions grew in 2020 (by 1.4%) followed by a projected growth of 4% this year.

Taking these two years together, CO₂ emissions from China in 2021 are projected to be 5.5% above 2019 levels, reaching 11.1 billion tonnes. China accounted for 31% of global emissions in 2020.

Coal emissions in China are estimated to grow by 2.4% this year. If realised, it would match what was thought to be China’s peak coal emissions in 2013.

India’s CO₂ emissions are projected to grow even faster than China’s this year at 12.6%, after a 7.3% fall last year. Emissions this year are set to be 4.4% above 2019 levels – reaching 2.7 billion tonnes. India accounted for 7% of global emissions in 2020.

Emissions from both the US and European Union are projected to rise 7.6% this year. It would lead to emissions that are, respectively, 3.7% and 4.2% below 2019 levels.

US and EU, respectively, accounted for 14% and 7% of global emissions in 2020.

Emissions in the rest of the world (including all international transport, particularly aviation) are projected to rise 2.9% this year, but remain 4.2% below 2019 levels. Together, these countries represent 59% of global emissions.

The Remaining Carbon Budget

The relatively large changes in annual emissions over the past two years have had no discernible effect in the speed at which CO₂ accumulates in the atmosphere.

CO₂ concentrations, and associated global warming, are driven by the accumulation of greenhouse gases – particularly CO₂ – since the beginning of the industrial era. This accumulation has accelerated in recent decades.

To stop further global warming, global CO₂ emissions must stop or reach net-zero – the latter meaning that any remaining CO₂ emissions would have to be compensated for by removing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere.

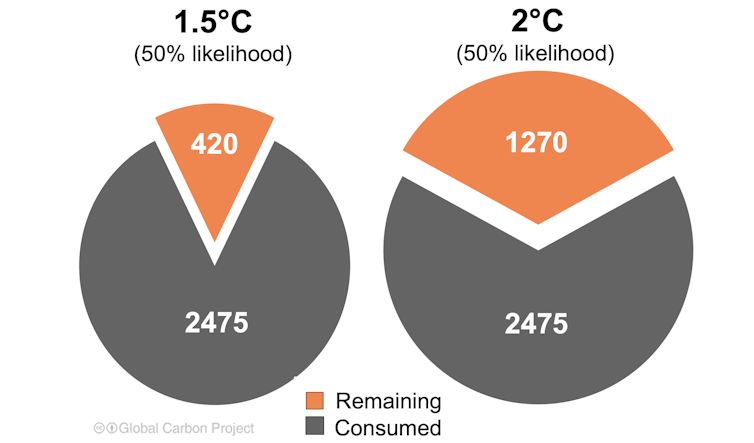

Carbon budgets are a useful way of measuring how much CO₂ can be emitted for a given level of global warming. In our latest analysis, we updated the carbon budget outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in August this year.

From the beginning of 2022, the world can emit an additional 420 billion tonnes of CO₂ to limit global warming to 1.5℃, or 11 years of emissions at this year’s rate.

To limit global warming to 2℃, the world can emit an additional 1,270 billion tonnes of CO₂ – or 32 years of emissions at the current rate.

These budgets are the compass to net-zero emissions. Consistent with the pledge by many countries to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, CO₂ emissions need to decline by 1.4 billion tonnes each year, on average.

This is an amount comparable to the drop during 2020, of 1.9 billion tonnes. This fact highlights the extraordinary challenge ahead and the need to increase short- and long-term commitments to drive down global emissions.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage on COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

Amid a rising tide of climate news and stories, The Conversation is here to clear the air and make sure you get information you can trust. More. ![]()

Pep Canadell, Chief research scientist, Climate Science Centre, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere; and Executive Director, Global Carbon Project, CSIRO; Corinne Le Quéré, Royal Society Research Professor of Climate Change Science, University of East Anglia; Glen Peters, Research Director, Center for International Climate and Environment Research - Oslo; Pierre Friedlingstein, Chair, Mathematical Modelling of Climate, University of Exeter; Robbie Andrew, Senior Researcher, Center for International Climate and Environment Research - Oslo, and Rob Jackson, Professor, Department of Earth System Science, and Chair of the Global Carbon Project, Stanford University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Australia is about to be hit by a carbon tax whether the prime minister likes it or not, except the proceeds will go overseas

Ten years ago, in the lead-up to Australia’s short-lived carbon price or “carbon tax” (either description is valid), the deepest fear on the part of businesses was that they would lose out to untaxed firms overseas.

Instead of buying Australian carbon-taxed products, Australian and export customers would buy untaxed (possibly dirtier) products from somewhere else.

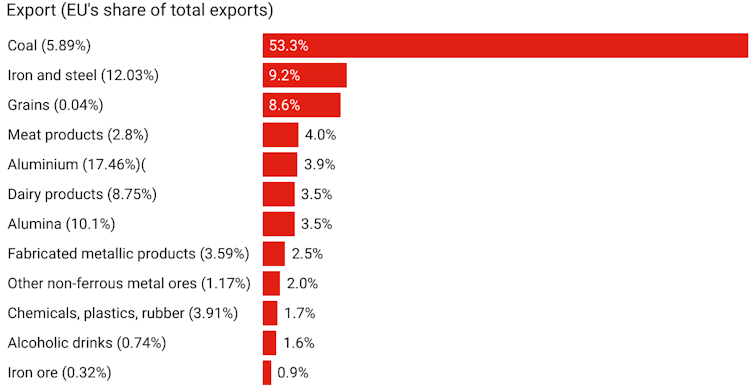

It would give late-movers (countries that hadn’t yet adopted a carbon tax) a “free kick” in industries from coal and steel to aluminium to liquefied natural gas to cement, to wine, to meat and dairy products, even to copy paper.

It’s why the Gillard government handed out free permits to so-called trade-exposed industries, so they wouldn’t face unfair competition.

As a band-aid, it sort of worked. The firms with the most to lose were bought off.

But it was hardly a solution. What if every country had done it? Then, wherever there was a carbon tax (and wherever there wasn’t), trade-exposed industries would be exempt. The tax wouldn’t do enough to bring down emissions.

We Are About To Face Carbon Tariffs

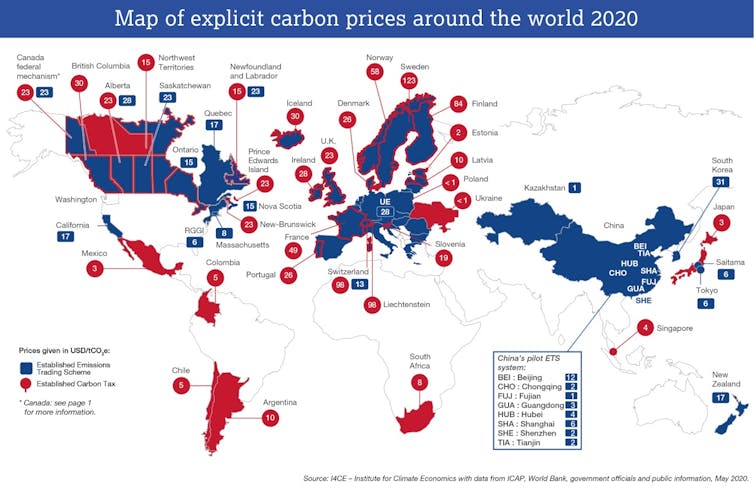

The European Union has cottoned on to the imperfect workarounds introduced by countries such as Australia, and is about to tackle things from the other direction.

Instead of treating foreign and local producers the same by letting them both off the hook, it’s going to place both on the hook.

It’s about to make sure producers in higher-emitting countries such as China (and Australia) can’t undercut producers who pay carbon prices.

Unless foreign producers pay a carbon price like the one in Europe, the EU will impose a carbon price on their goods as they come in — a so-called Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or “carbon tariff”.

Australia’s Energy Minister Angus Taylor says he is “dead against” carbon tariffs, a stance that isn’t likely to carry much weight in France or any of the other 26 EU nations.

Australia Is Familiar With The Arguments For Them

From 2026, Europe will apply the tariff to direct emissions from imported iron, steel, cement, fertiliser, aluminium and electricity, with other products (and possibly indirect emissions) to be added later.

That is, unless they come from a country with a carbon price.

Canada is also exploring the idea, as part of “levelling the playing field”. So is US President Joe Biden, who wants to stop polluting countries “undermining our workers and manufacturers”.

Their arguments line up with those heard in Australia in the lead-up to our carbon price: that unless there’s some sort of adjustment, a local carbon tax will push local employers towards “pollution havens” where emissions are untaxed.

Read more: The EU is considering carbon tariffs on Australian exports. Is that legal?

In practice, there’s little Australia can do to stop Europe and others imposing carbon tariffs.

As Australia discovered when China blocked its exports of wine and barley, there’s little a free trade agreement, or even the World Trade Organisation, can do. The WTO was neutered when former US President Donald Trump blocked every appointment to its appellate body, leaving it unstaffed, a stance Biden hasn’t reversed.

Even so, the EU believes such action would be allowed under trade rules, pointing to a precedent established by Australia, among other countries.

Legality Isn’t The Point

When Australia introduced the Goods and Services Tax in 2000, it passed laws allowing it to tax imports in the same way as locally produced products, a move it has recently extended to small parcels and services purchased online.

Trade expert and Nobel Prizewinning economist Paul Krugman says he is prepared to argue the toss with politicians such as Australia’s trade minister about what’s legal and whether carbon tariffs would be “protectionist”.

But he says that’s beside the point:

Yes, protectionism has costs, but these costs are often exaggerated, and they’re trivial compared with the risks of runaway climate change. I mean, the Pacific Northwest — the Pacific Northwest! — has been baking under triple-digit temperatures, and we’re going to worry about the interpretation of Article III of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade?

And some form of international sanctions against countries that don’t take steps to limit emissions is essential if we’re going to do anything about an existential environmental threat.

Victoria University calculations suggest Europe’s carbon tariffs will push up the price of imported Australian iron, steel and grains by about 9%, and drive up the price of every other Australian import by less, apart from coal whose imported price would soar by 53%.

The tariffs would be collected by Europe rather than Australia. They could be escaped if Australian makers of iron, steel and other products can find ways to cut emissions.

Increase in price of exports to EU under carbon border adjustment mechanism

The tariffs could also be avoided if Australia were to introduce a carbon price or something similar, and collected the money itself.

This makes a compelling case for another look at an Australian carbon price. If Australian emissions are on the way down anyway, as Prime Minister Scott Morrison contends, it needn’t be set particularly high. If he is wrong, it would need to be set higher.

Read more: No point protesting, Australia faces carbon levies unless it changes course

One thing the sad story of Australia’s on-again, off-again, now on-again (through carbon tariffs) history of carbon pricing has shown is that politicians aren’t the best people to set the rates.

In 2011, Prime Minister Julia Gillard set up an independent, Reserve Bank-like Climate Change Authority to advise on the carbon price and emissions targets, initially chaired by a former governor of the Reserve Bank.

Astoundingly, despite attempts to abolish it, it still exists. It might yet have work to do.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Closing the loophole: a minimum wage for Australia’s farm workers is long overdue

The Fair Work Commission’s ruling that Australian farm workers paid piece rates to pick fruit and vegetables must now get a base wage of $25.41 an hour is long overdue and absolutely necessary.

In theory, anyone working in Australia should be paid a minimum wage. But piecework payments, by which workers are paid solely on what they produce with no guarantee of a minimum rate, have lingered on as a common practice in the agricultural sector.

As the commission’s ruling notes: “A substantial proportion of the seasonal harvesting workforce are engaged on piece rates and more than half of the seasonal harvesting workforce are temporary migrant workers. These characteristics render the seasonal harvesting workforce vulnerable to exploitation.”

Piecework arrangements needn’t be exploitative. It depends on the rates – whether they’re enough to make a living in a bad season, when fruit is scarce. By law, they should be. In practice they haven’t been. The Fair Work Commission has acknowledged and sought to address this. It’s about time.

Underpayment Is An Open Secret

The Horticulture Award, which covers farm fruit and vegetable pickers, does set minimum weekly and hourly rates. But it also permits full-time, part-time or casual employees to make a piece-rate agreement with their employee.

Such agreements must be entered into “without coercion or duress”, and the agreed rate is meant to “enable the average competent employee to earn at least 15% more per hour than the minimum hourly rate” set in the award.

This has not been the reality for many.

Read more: We've let wage exploitation become the default experience of migrant workers

In 2017 the National Temporary Migrant Work Survey found wage theft common for migrant workers. Of 4,322 participants in the survey, 46% earned no more than $15 an hour, while 30% earned $12 a hour or less. Wage theft was prevalent across a range of industries, but the worst paid jobs were in farm work. Of the migrants working as fruit and vegetable pickers, 31% earned $10 per hour or less, while 15% earned $5 an hour or less.

A 2019 study by Unions NSW and the Migrant Worker Centre in Victoria found similarly grim results. Of 1,300 migrant workers surveyed, 78% reported being underpaid at some point, and 34% on piece rates had never signed an agreement. The lowest piece rates reported were from grape and zucchini farms, where respondents reported earning as little as $9 a day.

Just ask any backpacker working in the sector if they know anyone who has been ripped off. It’s not exactly a secret. I’ve picked fruit myself and experienced it firsthand.

A Particularly Vulnerable Workforce

It is worth noting that not all migrant farm workers have been equally vulnerable.

The Seasonal Worker Program, for workers from nine Pacific nations and Timor Leste, has been more tightly regulated, and generally successful in avoiding the sort of exploitation described above. In 2019 this program offered about 12,000 visas. Stephen Howes of the Development Policy Centre has argued the program could be expanded to more than 100,000 places.

Read more: Why closing our borders to foreign workers could see fruit and vegetable prices spike

Far more vulnerable to exploitation have been those on the more laissez-faire Working Holiday Maker Scheme – better known as the backpackers’ visa. This visa requires 88 days of farm work to stay in Australia for a year, and a further 180 days to stay for a second year. The evidence is that many accept being underpaid for those periods as a cost of staying in Australia.

Newly arrived Australian residents, particularly refugees, are also at risk, due to unfamiliarity with working rights and entitlements.

Read more: Why Australian unions should welcome the new Agricultural Visa

Closing A Loophole

If piece rates are set at a fair level, and the agreement is truly voluntary, such payment can be win-win – good for the farmer and an opportunity for a motivated worker to earn better money than just working for a flat minimum rate.

A lot of my career has involved working abroad in places where the poor and unconnected have no hope of getting ahead. Researching on Australian agriculture I’ve often been touched by the stories I’ve heard of experienced pickers, who plan to keep picking to save enough money to buy land of their own. They tend to be fierce and hard-working. You don’t want to get between them and the good fruit.

But not everyone is an experienced picker able to look out for their own interests. That is why a base rate is essential.

The problem with the piecemeal rate provisions in the the Horticulture Award was that clause 15.2(i) stated:

Nothing in this award guarantees an employee on a piecework rate will earn at least the minimum ordinary time weekly rate or hourly rate in this award for the type of employment and the classification level of the employee, as the employee’s earnings are contingent on their productivity.

The Australian Workers Union applied in December 2020 to have this clause struck out and replaced with a provision setting a minimum hourly rate for piecework. This application was supported by the United Workers’ Union, the Australian Council of Social Service, and the state governments of Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia.

Read more: How migrant workers are critical to the future of Australia's agricultural industry

The application was opposed by the Australian Fresh Produce Alliance, the Australian Industry Group and the National Farmer’s Federation.

In its decision on October 3, the Fair Work Commission said while some pieceworkers earn significantly more than the target rate for the “average competent employee”, the totality of the evidence “presents a picture of significant underpayment of pieceworkers”.

The best way to look at this is the Fair Work Commission closing a loophole.

It was already the responsibility of employers to pay piece rates high enough to allow competent workers make 15% more the minimum wage. Rather than thinking of this ruling as imposing an “extra cost” on farmers, it should been seen as putting in place a mechanism to ensure compliance with law.

A base rate takes the prospect of vulnerable workers getting paid $3 an hour off the table. That’s not asking for a lot.![]()

Michael Rose, Research fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

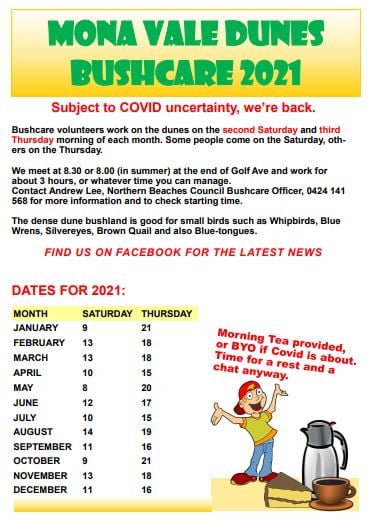

Bushcare In Pittwater

Where we work Which day What time

Avalon

Angophora Reserve 3rd Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Dunes 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Avalon Golf Course 2nd Wednesday 3 - 5:30pm

Careel Creek 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Toongari Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon (8 - 11am in summer)

Bangalley Headland 2nd Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bayview

Winnererremy Bay 4th Sunday 9 to 12noon

Bilgola

North Bilgola Beach 3rd Monday 9 - 12noon

Algona Reserve 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Plateau Park 1st Friday 8:30 - 11:30am

Church Point

Browns Bay Reserve 1st Tuesday 9 - 12noon

McCarrs Creek Reserve Contact Bushcare Officer To be confirmed

Clareville

Old Wharf Reserve 3rd Saturday 8 - 11am

Elanora

Kundibah Reserve 4th Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Mona Vale

Mona Vale Mona Vale Beach Basin 1st Saturday 8 - 11am

Mona Vale Dunes 2nd Saturday +3rd Thursday 8:30 - 11:30am

Newport

Bungan Beach 4th Sunday 9 - 12noon

Crescent Reserve 3rd Sunday 9 - 12noon

North Newport Beach 4th Saturday 8:30 - 11:30am

Porter Reserve 2nd Saturday 8 - 11am

North Narrabeen

Irrawong Reserve 2nd Saturday 2 - 5pm

Palm Beach

North Palm Beach Dunes 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Scotland Island

Catherine Park 2nd Sunday 10 - 12:30pm

Elizabeth Park 1st Saturday 9 - 12noon

Pathilda Reserve 3rd Saturday 9 - 12noon

Warriewood

Warriewood Wetlands 1st Sunday 8:30 - 11:30am

Whale Beach

Norma Park 1st Friday 9 - 12noon

Western Foreshores

Coopers Point, Elvina Bay 2nd Sunday 10 - 1pm

Rocky Point, Elvina Bay 1st Monday 9 - 12noon

Gardens And Environment Groups And Organisations In Pittwater

Avalon Golf Course Bushcare Needs You

Pittwater Reserves + Others

A History Of The Campaign For Preservation Of The Warriewood Escarpment by David Palmer OAM and Angus Gordon OAM

Angophora Reserve - Angophora Reserve Flowers

Annie Wyatt Reserve - A Pictorial

Avalon's Village Green: Avalon Park Becomes Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Bairne Walking Track Ku-Ring-Gai Chase NP by Kevin Murray

Bangalley Headland Bangalley Mid Winter

Banksias of Pittwater

Barrenjoey Headland: Spring flowers Barrenjoey Headland after fire

Bayview Baths

Bayview Wetlands

Beeby Park

Bilgola Beach

Botham's Beach

Bungan Beach Bush Care

Careel Bay Saltmarsh plants

Careel Bay Birds

Careel Bay Clean Up day

Careel Bay Playing Fields History and Current

Careel Creek

Careel Creek - If you rebuild it they will come

Centre trail in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park

Chiltern Track- Ingleside by Marita Macrae

Clareville Beach

Clareville/Long Beach Reserve + some History

Coastal Stability Series: Cabbage Tree Bay To Barrenjoey To Observation Point by John Illingsworth, Pittwater Pathways, and Dr. Peter Mitchell OAM

Cowan Track by Kevin Murray

Curl Curl To Freshwater Walk: October 2021 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Currawong State Park Currawong Beach + Currawong Creek

Deep Creek To Warriewood Walk photos by Joe Mills

Drone Gives A New View On Coastal Stability; Bungan: Bungan Headland To Newport Beach + Bilgola: North Newport Beach To Avalon + Bangalley: Avalon Headland To Palm Beach

Dunbar Park - Some History + Toongari Reserve and Catalpa Reserve

Dundundra Falls Reserve: August 2020 photos by Selena Griffith - Listed in 1935

Elsie Track, Scotland Island

Elvina Track in Late Winter 2019 by Penny Gleen

Elvina Bay Walking Track: Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Elvina Bay-Lovett Bay Loop Spring 2020 by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Fern Creek - Ingleside Escarpment To Warriewood Walk + Some History photos by Joe Mills

Ingleside

Ingleside Wildflowers August 2013

Irrawong - Ingleside Escarpment Trail Walk Spring 2020 photos by Joe Mills

Irrawong - Mullet Creek Restoration

Katandra Bushland Sanctuary - Ingleside

McCarrs Creek

McCarr's Creek to Church Point to Bayview Waterfront Path

McKay Reserve

Mona Vale Beach - A Stroll Along, Spring 2021 by Kevin Murray

Mona Vale Headland, Basin and Beach Restoration

Mount Murray Anderson Walking Track by Kevin Murray and Joe Mills

Mullet Creek

Narrabeen Creek

Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Past Notes Present Photos by Margaret Woods

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park

Narrabeen Lagoon State Park Expansion

Narrabeen Rockshelf Aquatic Reserve

Nerang Track, Terrey Hills by Bea Pierce

Newport Bushlink - the Crown of the Hill Linked Reserves

Newport Community Garden - Woolcott Reserve

Newport to Bilgola Bushlink 'From The Crown To The Sea' Paths: Founded In 1956 - A Tip and Quarry Becomes Green Space For People and Wildlife

Pittwater spring: waterbirds return to Wetlands

Pittwater's Lone Rangers - 120 Years of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase and the Men of Flowers Inspired by Eccleston Du Faur

Pittwater's Parallel Estuary - The Cowan 'Creek

Riddle Reserve, Bayview

Salvation Loop Trail, Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park- Spring 2020 - by Selena Griffith

Stapleton Reserve

Stapleton Park Reserve In Spring 2020: An Urban Ark Of Plants Found Nowhere Else

The Chiltern Track

The Resolute Beach Loop Track At West Head In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park by Kevin Murray

Towlers Bay Walking Track by Joe Mills

Trafalgar Square, Newport: A 'Commons' Park Dedicated By Private Landholders - The Green Heart Of This Community

Turimetta Beach Reserve by Joe Mills, Bea Pierce and Lesley

Turimetta Beach Reserve: Old & New Images (by Kevin Murray) + Some History

Turimetta Headland

Warriewood Wetlands and Irrawong Reserve

Whale Beach Ocean Reserve: 'The Strand' - Some History On Another Great Protected Pittwater Reserve

Winji Jimmi - Water Maze

New Shorebirds WingThing For Youngsters Available To Download

A Shorebirds WingThing educational brochure for kids (A5) helps children learn about shorebirds, their life and journey. The 2021 revised brochure version was published in February 2021 and is available now. You can download a file copy here.

If you would like a free print copy of this brochure, please send a self-addressed envelope with A$1.10 postage (or larger if you would like it unfolded) affixed to: BirdLife Australia, Shorebird WingThing Request, 2-05Shorebird WingThing/60 Leicester St, Carlton VIC 3053.

Shorebird Identification Booklet

Shorebird Identification Booklet

The Migratory Shorebird Program has just released the third edition of its hugely popular Shorebird Identification Booklet. The team has thoroughly revised and updated this pocket-sized companion for all shorebird counters and interested birders, with lots of useful information on our most common shorebirds, key identification features, sighting distribution maps and short articles on some of BirdLife’s shorebird activities.

The booklet can be downloaded here in PDF file format: http://www.birdlife.org.au/documents/Shorebird_ID_Booklet_V3.pdf

Paper copies can be ordered as well, see http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/shorebirds-2020/counter-resources for details.

Download BirdLife Australia's children’s education kit to help them learn more about our wading birdlife

Shorebirds are a group of wading birds that can be found feeding on swamps, tidal mudflats, estuaries, beaches and open country. For many people, shorebirds are just those brown birds feeding a long way out on the mud but they are actually a remarkably diverse collection of birds including stilts, sandpipers, snipe, curlews, godwits, plovers and oystercatchers. Each species is superbly adapted to suit its preferred habitat. The Red-necked Stint is as small as a sparrow, with relatively short legs and bill that it pecks food from the surface of the mud with, whereas the Eastern Curlew is over two feet long with a exceptionally long legs and a massively curved beak that it thrusts deep down into the mud to pull out crabs, worms and other creatures hidden below the surface.

Some shorebirds are fairly drab in plumage, especially when they are visiting Australia in their non-breeding season, but when they migrate to their Arctic nesting grounds, they develop a vibrant flush of bright colours to attract a mate. We have 37 types of shorebirds that annually migrate to Australia on some of the most lengthy and arduous journeys in the animal kingdom, but there are also 18 shorebirds that call Australia home all year round.

What all our shorebirds have in common—be they large or small, seasoned traveller or homebody, brightly coloured or in muted tones—is that each species needs adequate safe areas where they can successfully feed and breed.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is managed and supported by BirdLife Australia.

This project is supported by Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority and Hunter Local Land Services through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. Funding from Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and Port Phillip Bay Fund is acknowledged.

The National Shorebird Monitoring Program is made possible with the help of over 1,600 volunteers working in coastal and inland habitats all over Australia.