inbox and Environment news: Issue 518

November 14 - 20, 2021: Issue 518

Flowering Now: Blueberry Ash

Happening Now: Spotted Gums Shedding Bark - Part Of An Endangered Ecological Community

- Acacia floribunda

- Acrotriche divaricata

- Adiantum aethiopicum

- Allocasuarina litoralis

- Allocasuarina torulosa

- Angophora costata

- Angophora floribunda

- Billardiera scandens

- Breynia oblongifolia

- Cassytha paniculata

- Cayratia clematidea

- Cissus hypoglauca

- Corymbia gummifera

- Corymbia maculata

- Dianella caerulea

- Dodonaea triquetra

- Doodia caudata

- Eleocarpus reticulatis

- Entolasia stricta

- Eucalyptus botryoides

- Eucalyptus paniculata

- Eucalytpus punctata

- Eucalyptus umbra

- Eustrephus latifolius

- Geitonoplesium cymosum

- Glochidion ferdinandi

- Gymnostachys anceps

- Hakea sericea

- Hydrocotyle peduncularis

- Livistona australis

- Lomandra longifolia

- Macrozamia communis

- Notelaea longifolia

- Oxylobium ilicifolium

- Pandorea pandorana

- Pittosporum undulatum

- Platylobium formosum

- Pseuderanthemum variabile

- Pteridium esculentum

- Pultenaea flexilis

- Syncarpia glomulifera

- Synoum glandulosum

- Themeda australis

- Xanthorrhoea macronema

- Benson, D. and Howell, J., 1990, Taken for Granted: The bushland of Sydney and its suburbs, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst.

- Benson, D. and Howell, J. (1994) The natural vegetation of the Sydney 1:100 000 Map Sheet. Cunninghamia 3(4):677-787.

- ANPS - Australian Native Plants society, Corymbia maculata, from: http://anpsa.org.au/c-mac.html

- Pittwater Spotted Gum Forest - endangered ecological community listing, NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment

Woolworths Installs Recycled Plastic Seats In Australian Stores

Careel Creek: Dusky Moorhen In Residence - Please Keep Your Dogs On Their Leads

Dusky Moorhen in Careel Creek, Saturday October 30, 2021 - photos by A J Guesdon

Dusky Moorhen in Careel Creek, Thursday November 30, 2021 - photos by A J Guesdon

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Pittwater Nature No:8

Pittwater Natural Heritage Association (PNHA): Pittwater Nature No:8

Councils Urged To Get Scrap Together To Turn Food Waste Into Compost

More food waste will be saved from landfill thanks to a tailored education campaign to help communities turn more of their food scraps into valuable compost.

More food waste will be saved from landfill thanks to a tailored education campaign to help communities turn more of their food scraps into valuable compost.Wild Pollinator Count: November 14-21

November 2021 Forum For Friends Of Narrabeen Lagoon Catchment: Fishing Bats And Water Rats (Rakali)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741816240)

.jpg?timestamp=1631741908384)

Draft Marine Park Management Plan Released

Home Gardeners In Sydney Basin To Help Protect Local Fruit And Vegetable Production: Get Your Free Sticky Trap

Migratory Bird Season

Baby Wildlife Season

Harry the ringtail possum. Sydney Wildlife photo

Blockade Australia Purpose Statement + Actions

“I’m sick of Australia destroying country and sacred sites to get their resources. That’s why I am here doing this action today to put a stop to it myself.” - Wilkarr Kurikutahr

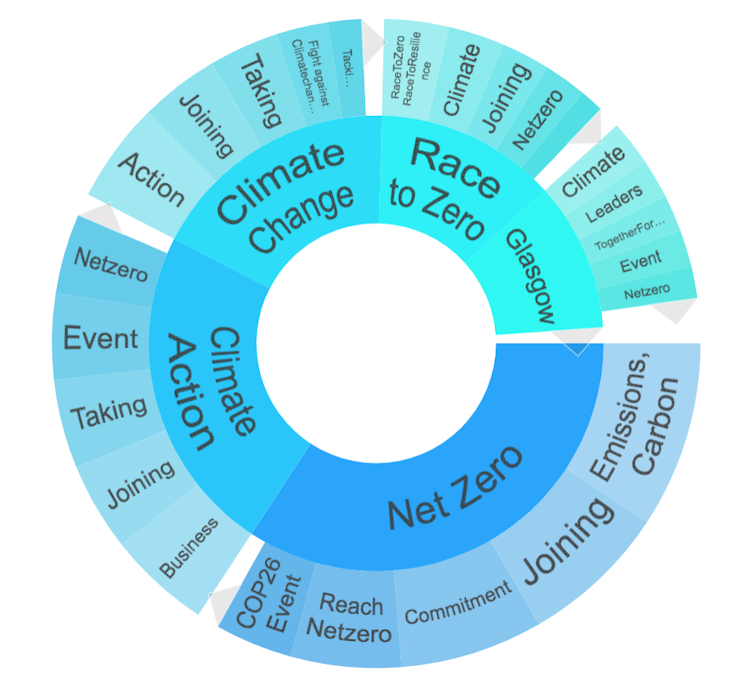

NSW, ACT And SA To Be Founding Members Of Net Zero Emissions Policy Forum At Glasgow

- provide a repository of existing policies and resources that can be accessed by participants

- facilitate collaboration between governments to design policies and to work together to solve the problems of achieving net zero emissions

- enable problem solving to address policy challenges and speed up the transition to net zero.

NSW National Parks Commits To Net Zero By 2028

Australia's First Renewable Energy Zone Declared

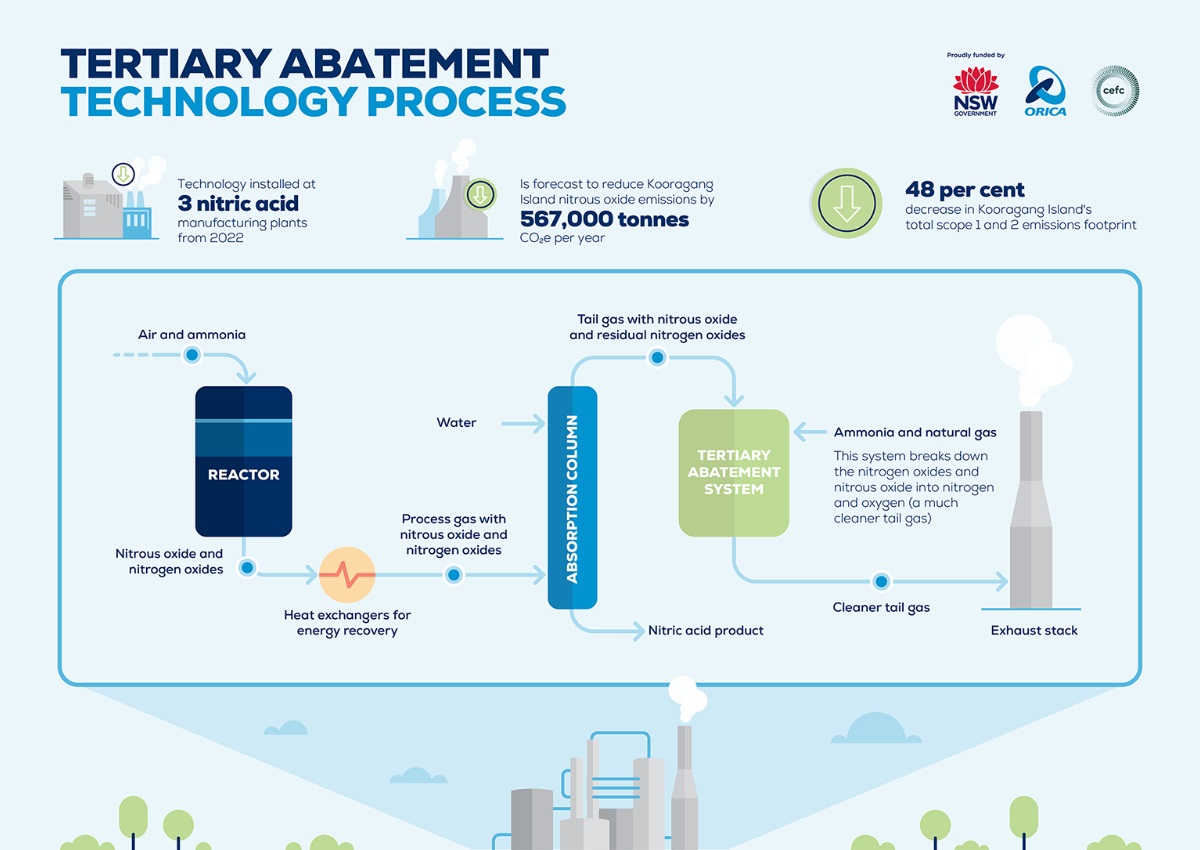

$13 Million To Halve Kooragang Island's Emissions And Support Jobs

ORICA PARTNERS WITH GOVERNMENT TO REDUCE KOORAGANG ISLAND SITE GHG EMISSIONS BY 48%

- The primary source of GHG emissions at the Kooragang Island facility is from the production of ammonia and nitric acid, both intermediaries in the production of ammonium nitrate. The production of nitric acid generates nitrous oxide as a by-product of catalytic oxidation of ammonia.

- In 2022, Orica will upgrade three nitric acid processing plants at its Kooragang Island site used in the production of ammonium nitrate, with technology designed to abate nitrous oxide emissions.

- This will be the first time the technology has been deployed in Australia, and is designed to deliver up to 95 per cent abatement efficiency from unabated levels. We expect to see a reduction in emissions by 567,000 tCO2e per year, and deliver a cumulative emissions reduction of at least 4.7 MtCO2e by 2030 based on forecast production.

- To facilitate the project, the New South Wales Government’s Net Zero Industry and Innovation Program will co-invest $13.06 million, together with Orica’s $24 million financed by a 5-year debt facility provided by the Federal Government’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation. The Clean Energy Regulator has also approved the project as eligible to generate Australian Carbon Credit Units.

- Kooragang Island employs 253 full time workers and contractors, and in 2019, $120 million was contributed to the New South Wales economy with over 1,500 additional jobs supported at state level. For every $1 million investment by Kooragang Island, an indicative $170,000 in additional activity occurs and 15 additional jobs are supported in the broader economy.

- Together with environmental outcomes, the project will ensure Orica’s domestic manufacturing operations remain competitive in a low carbon economy and continue to contribute to the local economy. Almost half of the $37 million project will be spent with local New South Wales suppliers. This builds on Orica’s history supporting local socio-economic development with two-thirds of suppliers to the site being located either in the Hunter Valley (38 per cent) or across New South Wales (28 per cent)

- Orica has recently announced a target to reduce scope 1 and 2 operational emissions by 40% (on FY19 levels), and an ambition to achieve net zero emissions by 2050iii.

New NSW Frog Species 'Hopping' Into Protection

.jpg?timestamp=1636656869806)

Fine Issued For Emissions From Liddell Power Station

Fines For Coal Mine For Dirty Water Discharge: Whitehaven's Tarrawonga Coal Mine

Whitehaven’s Tarrawonga Coal Mine has been fined and ordered to do an environmental audit after it allegedly discharged dirty water from a failed sediment dam at its mine near Boggabri, in north western NSW.

Whitehaven’s Tarrawonga Coal Mine has been fined and ordered to do an environmental audit after it allegedly discharged dirty water from a failed sediment dam at its mine near Boggabri, in north western NSW.$40 Million Clean Technology Grants Open

- electrification and energy systems

- primary industry and land management

- powerfuels, including hydrogen.

Green Hydrogen Feasibility Study Positions Port Of Newcastle To Drive A More Diverse Hunter Economy

NSW Government Plan To Revitalise Peat Island And Mooney Mooney Released

- Nearly 270 new homes at Mooney Mooney to deliver more housing supply,

- Retention of nine unlisted historical buildings on the island, and four on the mainland, to be restored and used for new community and commercial opportunities,

- New retail and café or restaurant opportunities,

- Approximately 9.65 hectares of open space, including opportunities for walking and cycling tracks, parklands and recreational facilities,

- Retention of the chapel and surrounding land for community use, and

- 10.4 hectares of bushland dedicated as a conservation area.

Grattan on Friday: Scott Morrison has a bingle or two on the campaign trail

Michelle Grattan, University of CanberraIt seemed remarkable chutzpah that Scott Morrison, back from Glasgow where Australia remains a criticised laggard despite its embrace of a 2050 target, would hit the trail to campaign on climate policy.

Alternatively, as some suggest, perhaps the prime minister just wanted to tick that box early, before moving onto more congenial issues.

Either way, it didn’t turn out well.

His policy to promote electric cars, which contained minimal substance, backfired. And he wedged himself with a too-smart-by-half attempt to wedge Labor on carbon capture and storage.

Morrison surely must have seen the dangers of exposing himself on electric cars, after all he’d said in denouncing Bill Shorten’s policy in 2019.

The quotes from then were grenades for the throwing. Shorten wanted to end the Aussie weekend, Morrison declared; such a vehicle “won’t tow your trailer. It’s not going to tow your boat. It’s not going to get you out to your favourite camping spot with your family.”

How did Morrison believe he could execute a turnaround in the harsh political spotlight without being called to account? Especially when his political honesty is under the most intense questioning.

Sean Kelly, columnist and former staffer for Julia Gillard and Kevin Rudd, writes in his just-published The Game: A Portrait of Scott Morrison that the PM, “never feels, in himself, insincere or untruthful, because he always means exactly what he says; it is just that he means it only in the moment he is saying it. Past and future disappear.”

Unfortunately for Morrison, the electronic clips don’t disappear. Those on electric cars were there to be played again and again.

Read more: Scott Morrison spruiks electric vehicles – but rules out subsidies and an end-date for petrol cars

Morrison himself explained his about-face by claiming it was a “Labor lie” that he had campaigned against EVs in 2019. “I didn’t. […] I was against Bill Shorten’s mandate policy, trying to tell people what to do with their lives, what cars they were supposed to drive and where they could drive.”

There was another problem with Morrison’s decision to climb into a hydrogen-fuelled car during his first visit to Melbourne in a very long time.

His policy – $178 million for charging and refuelling infrastructure and the like – lacked substance. It had no subsidies, with the government claiming they would not be a good use of taxpayers’ money.

Within hours of the announcement, a devastating critique of the policy came from his own side of politics, delivered by NSW Environment Minister Matt Kean.

Speaking to ABC 7.30, Kean contrasted Morrison’s weak policy with NSW’s robust approach and spelled out how Morrison should be acting.

“I would encourage the federal government to be looking at doing things like providing direct support for people who want to purchase an EV. There are a range of taxes and charges that could be waived,” Kean said.

“We want to see things like the federal government investing more heavily in electric vehicle charging infrastructure. The funding that they’ve put on the table doesn’t even match the funding that we’ve put here just for the state of New South Wales.

"But the biggest thing the federal government can do is deal with the issue of fuel standards. Australia has some of the worst fuel standards anywhere in the world”, which meant it “is becoming the dumping ground for the vehicles the rest of the world doesn’t want”.

The NSW government is forward-leaning on climate issues, and Kean and Morrison have some interesting history. The PM sledged him spectacularly last year after Kean said “some of the most senior members” of the Morrison government were concerned about its climate change policies.

Read more: Morrison to link $500 million for new technologies to easing way for carbon capture and storage

In one of those “in the moment” prime ministerial statements, Morrison responded that Kean “doesn’t know what he’s talking about” and declared “most of the federal cabinet wouldn’t even know who Matt Kean was”.

They certainly know now. Kean is treasurer as well as environment minister in the Perrottet government, and that government is willing to chivvy the Feds when it feels like it.

In another climate announcement this week, Morrison said the government would contribute $500 million for a new $1 billion fund, administered by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, to help small companies commercialise low-emissions technology.

The legislation will contain a provision widening the remit of the CEFC to allow it to invest in carbon capture and storage, which it is banned from doing at present.

Labor has consistently opposed such a widening, so the government briefed that this would put pressure on the opposition. But Labor took one look at the trap and seems determined to avoid it. It indicated it might support the change, given the $500 million would be “new money” for the CEFC rather than a redirection of existing funds. In the meantime, a couple of renegade Queensland Coalition senators, Matt Canavan and Gerard Rennick, flagged they’d vote against the fund.

More generally, Morrison this week sharpened the Coalition-Labor contrast he has set up on climate policy, between a government that encourages and supports and an opposition that would regulate and tax.

He encapsulated his desired dichotomy by saying that “we believe climate change will ultimately be solved by ‘can do’ capitalism, not ‘don’t do’ governments seeking to control people’s lives and tell them what to do, with interventionist regulation and taxes that just force up your cost of living and force businesses to close”.

Indeed, he seeks to use the contrast broadly. “I think that’s a good motto for us to follow not just in this area, but right across the spectrum of economic policy in this country,” he told a business audience. “We’ve got a bit used to governments telling us what to do over the last couple of years. I think we have to break that habit.”

This reverts to Liberal Party “free enterprise” ideology, which has had to take a battering in the pandemic as the government spent wildly to keep things afloat. It also taps into the post-lockdown sentiment of those exhausted by restrictions and orders and welcoming “freedom” again.

But in terms of climate policy, the reality is far from so simple.

Read more: Book review: Sean Kelly's The Game: A Portrait of Scott Morrison

The point has been made many times that “taxes” – taxpayers’ money – are financing the multiple billions the Morrison government has committed to encouraging “capitalist” solutions.

While expounding “can do capitalism”, the government is in fact pursuing an interventionist approach by putting all its eggs in the technology-support basket and not enough in the market-creation one.

“Scotty from Marketing” likes slogans, but “can do capitalism” doesn’t ring like one with a future. “Capitalism” works as an economic system (with more than a little help from governments), but it is beyond clunky as part of a sound bite.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

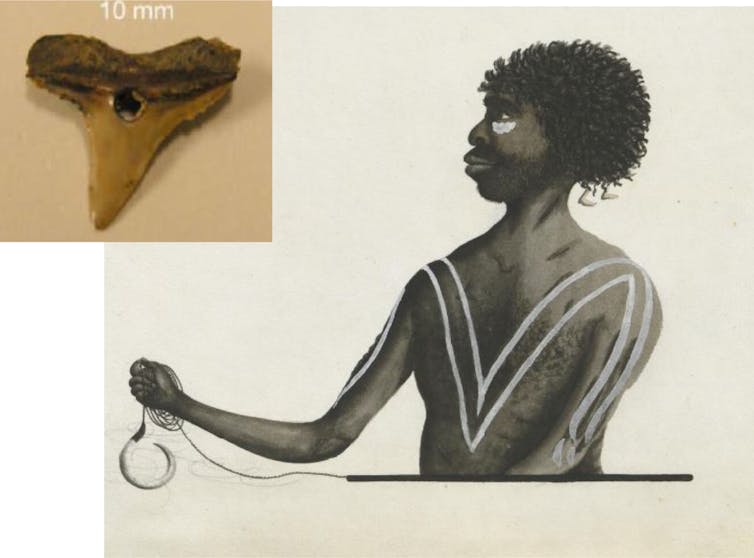

White sharks can easily mistake swimmers or surfers for seals. Our research aims to reduce the risk

The presumed death of 57-year-old Paul Millachip in an apparently fatal shark bite incident near Perth on November 6 is a traumatising reminder that while shark bites are rare, they can have tragic consequences.

Despite the understandably huge media attention these incidents generate, there has been little scientific insight into how and why they happen.

Sharks in general, and white sharks in particular, have long been described as “mindless killers” and “man-eaters”.

But our recent research confirms that some bites on humans may be the result of mistaken identity, whereby the sharks mistake humans for their natural prey based on visual similarities.

Sharks have an impressive array of senses, but vision is thought to be particularly important for prey detection in white sharks. For example, they can attack seal-shaped decoys at the surface of the water even though these decoys lack other sensory cues such as scent.

The visual world of a white shark varies substantially from that of our own. White sharks are likely colourblind and rely on brightness, essentially experiencing their world in shades of grey. Their eyesight is also much less acute than ours – in fact, it’s probably more akin to the blurry images a human would see underwater without a mask or goggles.

The Mistaken Identity Theory

Bites on surfers have often been explained by the fact that, seen from underneath, a paddling surfer looks a lot like a seal. But this presumed similarity has only previously been assessed based on human vision, using underwater photographs to compare their silhouettes.

Recent developments in our understanding of sharks’ vision have now made it possible to examine the mistaken identity theory from the shark’s perspective, using a virtual system that generates “shark’s-eye” images.

In our study, published last month, we and our colleagues in Australia, South Africa and the United Kingdom compared video footage of seals and of humans swimming and paddling surfboards, to predict what a young white shark sees when looking up from below.

We specifically studied juvenile white sharks – between of 2m and 2.5m in length – because data from New South Wales suggests they are more common in the surf zone and are disproportionately involved in bites on humans. This might be because juvenile sharks are more likely to make mistakes as they switch to hunting larger prey such as seals.

Our results showed it was impossible for the virtual visual system to distinguish swimming or paddling humans from seals. This suggests both activities pose a risk, and that the greater occurrence of bites on surfers might be linked to the times and locations of when and where people surf.

Our analysis suggests the “mistaken identity” theory is indeed plausible, from a visual perspective at least. But sharks can also detect prey using other sensory systems, such as smell, sound, touch and detection of electrical fields.

Read more: Why do shark bites seem to be more deadly in Australia than elsewhere?

While it seems unlikely every bite on a human by a white shark is a case of mistaken identity, it is certainly a possibility in cases where the human is on the surface and the shark approaches from below.

However, the mistaken identity theory cannot explain all shark bites and other factors, such as curiosity, hunger or aggression are likely to also explains some shark bites.

Can This Knowledge Help Protect Us?

As summer arrives and COVID restrictions lift, more Australians will head to the beach over the coming months, increasing the chances they might come into close proximity with a shark. Often, people may not even realise a shark is close by. But the past weekend gave us a reminder that shark encounters can also tragically result in serious injury or death.

Understanding why shark bites happen is a good first step towards helping reduce the risk. Our research has inspired the design of non-invasive, vision-based shark mitigation devices that are currently being tested, and which change the shape of the silhouette.

We still have a lot to learn about how sharks experience their world, and therefore what measures will most effectively reduce the risks of a shark bite. There is a plethora of devices being developed or commercially available, but only a few of them have been scientifically tested, and even fewer – such as the devices made by Ocean Guardian that create an electrical field to ward off sharks – have been found to genuinely reduce the risk of being bitten.![]()

Laura Ryan, Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University and Charlie Huveneers, Associate professor, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The ‘Ringo Starr’ of birds is now endangered – here’s how we can still save our drum-playing palm cockatoos

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do. In this series, we’ve invited them to share their unique photos from the field.

Australia’s largest parrot, the palm cockatoo, is justifiably famous as the only non-human animal to craft tools for sound. They create drumsticks to make a rhythmic beat. Sadly, the “Ringo Starr” of the bird world is now threatened with extinction – just as many other parrots are around the world.

This week, the Queensland government moved this species – also known as the goliath cockatoo – onto the endangered list, due to our research on palm cockatoo populations over more than 20 years.

Our analysis predicts a severe decline from 47% to as high as 95% over the next half-century. Given the current population is estimated at just 3,000 birds, it is likely to drop to as low as 150 birds. They could all but disappear from Australia in our lifetimes.

Is it too late? Not yet. There are concrete ways to protect these magnificent, elusive birds by conserving habitat and their all-important breeding hollow trees, by reintroducing cool burns (including unburnt areas), and finding out more about these special parrots.

So Why Are Palm Cockatoos In Trouble?

Palmies, as we call these charismatic birds, hail from an ancient lineage on the parrot evolutionary tree. In Australia they only live on the Cape York Peninsula in far north Queensland, where they face a perfect storm of threats and vulnerability.

They’re losing habitat due to poor fire management and ongoing land-clearing, but they also have extremely low breeding rates, with females laying a single egg every two years.

Of the offspring, only 23% of their chicks live until they fledge. On average, this means each breeding pair successfully raises just one chick every 10 years. And who knows if that fledgling will make it to sexual maturity at five or more years old?

Read more: Bird-brained and brilliant: Australia's avians are smarter than you think

One challenge in studying these birds is the difficulty in identifying individual birds over time. To date there has been no successful capture of palmies to mark them via leg bands or GPS trackers. Without knowing who’s who, major problems with breeding success could be masked by an ageing population, given their life expectancy is up to 60 years.

Our research on palm cockatoo genetics and vocal dialects reveals their three major populations on the peninsula are poorly connected, meaning little movement of birds between groups.

Each group has developed “cultural” traits which have not spread between the populations. For example, the famous drumming display mainly occurs in the eastern population, where the birds also make distinctive calls including a unique human-like “hello”.

The downside is that if one population is in trouble, the others are unable to pick up the slack and provide breeding reinforcements.

How Do We Save Them?

Palmies are in real trouble. Saving them from extinction will take a concerted effort.

We urgently need a better understanding of why they have such trouble breeding, to figure out if it’s similarly bad across all three populations, and to work out how palmies use the landscape.

At the same time, we have to get better at managing the landscape they need to survive. What does that look like? It means cool burns to prevent extreme bushfires burning down their ancient nesting trees – plus avoiding any further felling of these priceless trees.

These trees are a key part of the puzzle. Palmies are picky breeders. For these birds, not just any tree hollow will do. They require large, old hollow-bearing trees to breed in, which can be up to 300 years old.

The hollowing process typically starts with a small burn at the base, giving termites access to the insides of the trunk. Eventually, these trees resemble vertical hollow pipes. The palmies then spend months splintering sticks and bringing them to the hollow to make a nesting platform up to a metre deep – the only parrot to do in the entire world.

Unfortunately, these “piped” trees are especially vulnerable to big fires, which also lower termite populations and reduce the chances of future hollows being formed.

Protecting Their Habitat

We’ve found using a brush cutter and rake to clear the grass and debris for three metres around nesting trees is enough to save them from fires. This is of course labour intensive.

A longer-term strategy is to manage fire better. The frequency and intensity of bushfires in tropical Australia has changed for the worse since Europeans started managing the landscape. A return to the traditional cool burns employed by indigenous people from the Uutaalnganu, Kanthanampu and Kuuku Ya’u language groups could largely resolve this problem.

Land clearing also reduces habitat. Though long saved by distance, Cape York is now seeing strip-mining, road building, and quarrying, which all contribute to habitat loss. We can reduce the damage done if skilled ecologists survey proposed clearance areas ahead of time.

Another vital step towards keeping this species alive is to broadly assess and protect as much as possible of the remaining palm cockatoo breeding habitat on Cape York.

We also need better ways of detecting their nest hollows. We’ve researched these birds for over two decades, and can confidently say that birds don’t come any harder to study than palmies.

Hunting for their nests is time consuming and expensive because palmies can lay their egg any day in an eight month breeding season, with pairs often switching among several hollows on their territories. This spreads our survey teams thin.

We’ve also found that palmies go quiet during nesting and are super wary of humans, making finding their nesting hollows especially difficult.

Despite all the challenges in saving them, it is worthwhile. Even after watching them for 20 years, we have not tired of their company. They’re magnificent birds with unique behaviour and a surprising number of parallels with humans, such as drumming, blushing, tool-making, and their “Hello” call.

To bring them back from the edge, we must work quickly to figure out why and where their breeding survival rates are so low, improve how we use fire, and protect their habitat and the all-important old trees.![]()

Christina N. Zdenek, Lab Manager/Post-doc at the Venom Evolution Lab, The University of Queensland and Rob Heinsohn, Professor of Evolutionary and Conservation Biology, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Morrison to link $500 million for new technologies to easing way for carbon capture and storage

Prime Minister Scott Morrison will on Wednesday announce $500 million towards a new $1 billion fund to promote investment in Australian companies to develop low-emissions technologies.

But the government will use the legislation for the fund to try to wedge Labor.

The $500 million will be provided to the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, with the legislative package including the expansion of the remit of the CEFC to enable it to invest in carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The CEFC can invest in a broad range of low-emissions technologies, with the only exceptions being nuclear and CCS. The government has previously tried to remove the barrier to the CEFC investing in CCS but has been frustrated by the Senate.

By linking the $500 million to the expansion of the CEFC’s investment remit, the government believes it will put pressure on Labor, which opposed the wider brief for the corporation.

While the government’s legislation would remove the prohibition relating to CCS, there would be no change to the nuclear prohibition.

The government regards CCS, which is controversial and as yet unproven at scale, as a priority technology under its Technology Investment Roadmap.

The proposed fund is the latest in a round of announcements this week as Morrison campaigns on his technology-based energy policy for net-zero by 2050.

But Tuesday’s unveiling of his policy to encourage the take-up of electric vehicles – with $178 million for modest initiatives but no subsidies to assist purchasers – ran into immediate flak, with strong criticisms from experts and the opposition, who said it was totally inadequate.

NSW Environment Minister Matt Kean made it clear the Morrison government should be doing a great deal more.

He said he would like to see it directly support electric vehicles so they would be cheaper for families and businesses. A number of taxes and charges could be waived.

The federal government should also invest more heavily in in electric vehicle charging infrastructure, he told the ABC on Tuesday night.

But Kean said the biggest thing the federal government could do was deal with the issue of fuel standards – Australia had some of the worst fuel standards in the world, worse than China or India.

NSW on Wednesday will announce support for the fleet industry to purchase electric vehicles.

At a news conference on Tuesday Morrison was confronted by reporters over his 2019 trenchant attacks on Labor’s electric vehicle policy, which he said would “end the weekend”. Despite the quotes, Morrison denied he had campaigned against EVs at the election.

“I didn’t. That is just a Labor lie. I was against Bill Shorten’s mandate policy, trying to tell people what to do with their lives, what cars they were supposed to drive and where they could drive.”

The proposed “low emissions technology commercialisation fund” would include $500 million from private sector investors.

Morrison says in a statement the fund would back Australian early stage companies to develop new technologies.

Emissions reduction minister Angus Taylor says it would “address a gap in the Australian market, where currently small, complex, technology-focussed start-ups can be considered to be too risky to finance”.

The investments would be in the form of equity, not grants or loans.

The latest initiative brings the government’s public investment commitments to low emissions technologies by 2030 to more than $21 billion.

The government will introduce legislation to establish the fund – expected to earn a positive return for taxpayers – in this term of parliament.

The government’s list of example of potential areas for the fund’s investments include:![]()

- direct air capture of CO₂ and permanent storage underground

- materials or techniques with the potential to reduce emissions in the production in steel and aluminium

- soil carbon measurement technologies

- livestock feed technologies to reduce methane emissions from cattle

- improvements to solar panels

- lighter and smaller battery cases

- software developments to improve the operational efficiency of a variety of low-emissions technologies in all sectors of the economy.

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As the world surges ahead on electric vehicle policy, the Morrison government’s new strategy leaves Australia idling in the garage

The Morrison government will today announce its long-awaited electric vehicle strategy, coinciding with COP26 climate change talks underway in Glasgow. The new policy contains some welcome new funding, but is largely notable for what it omits.

In a welcome move, the government has allocated an additional A$250 million for electric vehicles, primarily aimed at charging infrastructure. But unlike every leading electric vehicle market globally, the plan delivers no financial or tax support to help Australian motorists make the switch to a cleaner car.

And the government has failed to explain how the policy will help Australia achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, just as it failed to do when releasing its economy-wide emissions reduction plan last month.

It’s encouraging to see the Morrison government move past its claim of a few years ago that electric vehicles would “end the weekend”. But the new plan is not the national electric vehicle strategy Australia deserves, and badly needs.

Falling Short

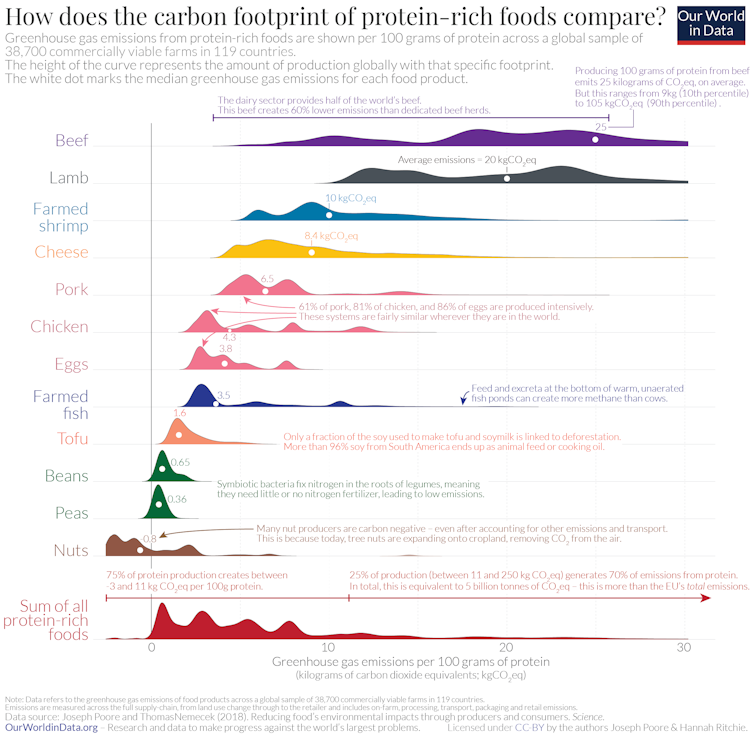

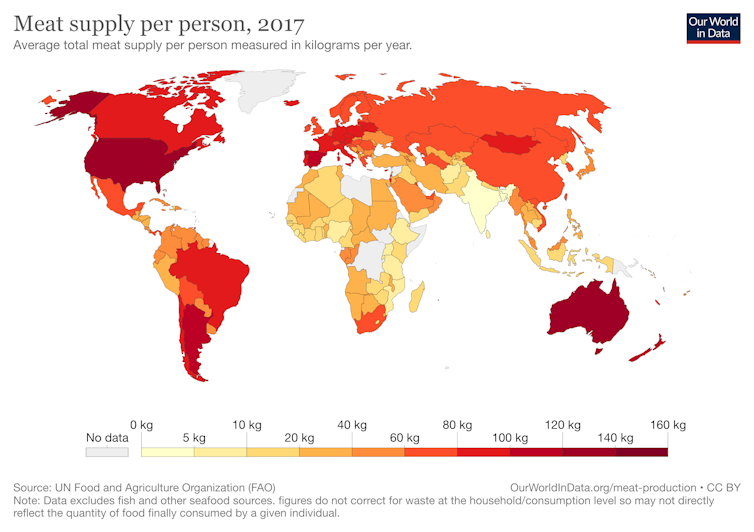

Transport produces almost 20% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions – 60% of which is from cars. And the rate of transport emissions is fast increasing.

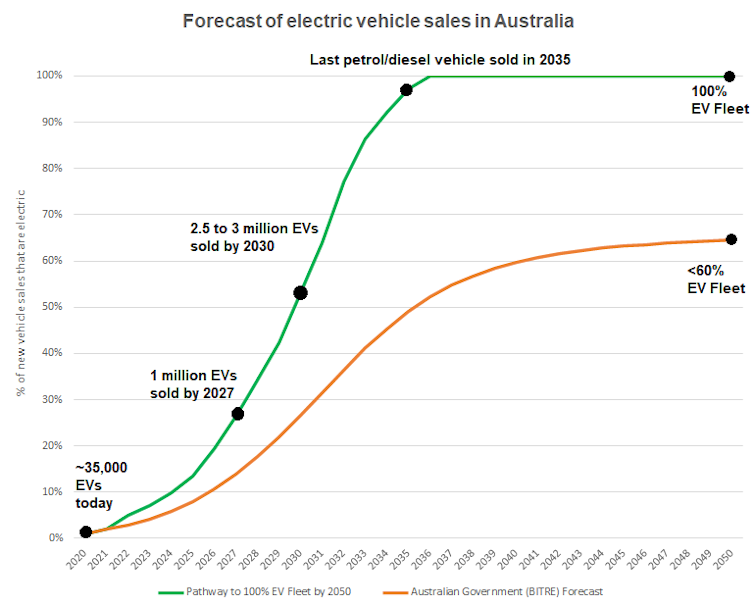

The government says the policy, titled the Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy, will lead to 30% of all new car sales being electric by 2030 – which would mean 1.7 million electric cars on Australian roads.

But in 2019, government modelling predicted electric vehicles would comprise 27% of new sales by 2030. So the new measures announced will lead only to a 3% increase in what would have happened anyway.

At COP26 last week, Australia signed a global agreement to make electric vehicles the “new normal” by 2030. One in three cars being electric vehicles hardly meets this goal.

Most concerningly, the government’s plan is inconsistent with global targets to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. The United States, for example, is aiming for at least 50% electric vehicle sales by 2030.

Oddly, it appears the government would prefer Australian motorists remain dependent on expensive, foreign fuel for transport. Its investment in July of $260 million to increase diesel reserves – notably more than the new electric vehicle funding – supports this theory.

Read more: Clean, green machines: the truth about electric vehicle emissions

Australia’s Token Effort

Globally, about 5% of all new cars sold are electric and this is rapidly increasing. Yet in Australia, the figure is about 1%.

So what measures does the new strategy contain to shift the needle? In two words, not much. It includes:

$250 million to support public charging infrastructure, fleet infrastructure, vehicle trials and smart charging infrastructure in households

continued low-interest financing support for fleets via the Clean Energy Finance Corporation

an overdue update to the Green Vehicle Guide.

It’s better than nothing. But the government has claimed electric vehicles will deliver around 15% of national emission reductions required by 2050. It’s hard to see how the measures released today will get us there.

The government has also claimed high international demand for electric vehicles could constrain global supply and slow deployment in Australia.

But as carmakers have pointed out, they have little reason to send new, cheaper electric models to Australia because it lacks the policies to stimulate electric vehicle demand.

Read more: The US jumps on board the electric vehicle revolution, leaving Australia in the dust

The Plan Australia Deserves

The Morrison government must go back to the drawing board and produce a national electric vehicle strategy consistent with global climate efforts.

That would mean aiming for at least half of new car sales being electric by 2030, and 100% by 2035. This translates to about one million electric vehicles sold in Australia by 2027 and at least 2.5 million by 2030.

It’s a massive increase from the 30,000 or so electric vehicles sold over the past five years, and at least 50% higher than what’s forecast under today’s strategy.

Australia can learn much from overseas jurisdictions on how to boost electric vehicle sales. Until electric vehicle targets are met, the following state and federal policies are needed:

increase supply by introducing a national sales mandate for electric vehicles, and penalise manufacturers that don’t meet them

reduce upfront costs by making electric vehicles exempt from GST, stamp duty and registration fees (as is done in Norway)

support fleet adoption by making electric vehicles exempt from fringe benefits tax

fund infrastructure by committing to support the rollout of 100,000 public charging points by 2027 (in line with the European Union’s target).

Penalise states that go it alone on taxing electric vehicle usage. Instead, focus on road charges that address Australia’s multi-billion dollar city congestion problem rather than unfairly taxing rural and regional electric vehicle drivers due to the longer distances they have to drive.

Read more: Here's why electric cars have plenty of grunt, oomph and torque

Why Australia Must Act

The benefits of electric vehicles go far beyond tackling climate change.

We estimate Australians spend more than $30 billion each year on imported fuel. This alone should be enough to spur governments to support electric vehicle adoption and keep this money in Australia.

Recent analysis by the Australian Conservation Foundation also found maintaining the current approach to transport emissions could cost Australia up to $865 billion between 2022 and 2050.

Aside from greenhouse gas emissions, the costs were attributed to air, noise and water pollution. But better zero-emission transport policies could enable Australia to reduce these costs by up to $492 billion.

Clearly, electric vehicles deliver a net economic benefit, even after accounting for the cost of incentives and loss of fuel tax revenue.

As the rest of the world charges ahead, the Morrison government’s new strategy looks ever more foolish.

Read more: Wrong way, go back: a proposed new tax on electric vehicles is a bad idea ![]()

Jake Whitehead, Tritum E-Mobility Fellow & Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellow, The University of Queensland; Jessica Whitehead, Industry Fellow, The University of Queensland, and Kai Li Lim, St Baker E-Mobility Fellow, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Scott Morrison spruiks electric vehicles – but rules out subsidies and an end-date for petrol cars

Michelle Grattan, University of CanberraAfter demonising Labor’s policy on electric cars before the 2019 election, the federal government has put electric vehicles at the centre of a new “Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy” to be released by Prime Minister Scott Morrison on Tuesday.

The policy puts another A$178 million into the government’s future fuels fund, bringing it to $250 million, for investment to encourage low emission vehicles.

The expanded fund will focus on four areas of investment: public electric vehicle charging and hydrogen refuelling infrastructure; heavy and long-distance vehicle technologies; commercial fleets, and household smart charging.

The government estimates its strategy will result in more than $500 million combined private and public co-investment for the uptake of future fuels and involve the creation of more than 2600 new jobs.

But the policy is minimalist, ruling out consumer subsidies and concessions or mandating a phase out of new petrol and diesel-powered vehicles.

In 2019 Morrison was scathing about the ALP electric vehicle policy – which set a target of 50% of all new car sales being electric vehicles by 2030.

While saying the government didn’t have a problem with electric vehicles per se, Morrison in 2019 claimed “Bill Shorten wants to end the weekend when it comes to his policy on electric vehicles where you’ve got Australians who love being out there in their four-wheel drives”.

Read more: COP26: here's what it would take to end coal power worldwide

Morrison says in his Tuesday announcement with emissions reduction minister Angus Taylor, “Australians love their family sedan, farmers rely on their trusted ute and our economy counts on trucks and trains to deliver goods from coast to coast.

"We will not be forcing Australians out of the car they want to drive or penalising those who can least afford it through bans or taxes. Instead, the strategy will work to drive down the cost of low and zero emission vehicles, and enhance consumer choice.

"We will do this by creating the right environment for industry co-investment.”

Sales of new technology vehicles are increasing quickly: battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles were a record 8,688 sales in the first half of this year, representing 1.57% of the total light vehicle market. This compared to 6,900 in 2020.

But the rise is coming off a low base. About 1% of new vehicles sold in Australia are electric – which lags behind the global average of 5%.

The government policy says by 2030 battery electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles are projected to make up 30% of annual new passenger and light commercial vehicle sales. This would translate into more than 1.7 million battery electric and plug-in vehicles on Australian roads by 2030.

The government says it will promote and bring forward priority market reforms to state and territory ministers “to ensure the electricity grid is EV-ready”.

The additional electric vehicle uptake enabled by the new investment will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 8 million tonnes by 2035, the government says.

Labor’s electric vehicle policy, released earlier this year, promised to deliver a discount to cut the cost of non-luxury electric cars. It would cost about $200 million over three years.

Read more: Scott Morrison is hiding behind future technologies, when we should just deploy what already exists

The government says during consultation for the new strategy, there were calls for subsidies or tax concessions to reduce the price difference between conventional and low emission vehicles.

But, it argues, “reducing the total cost of ownership through subsidies would not represent value for the taxpayer, particularly as industry is rapidly working through technological developments to make battery electric vehicles cheaper.

"The Australian Taxation Office will investigate issuing updated guidance for businesses on the tax measures of low emission vehicles to provide clarity for fleet purchasing.”

The government’s position on subsidies is at odds with industry experts, who say the measure is important to encourage motorists to make the switch to clean vehicles.

An exclusive poll of 62 of Australia’s preeminent economists, published by The Conversation in June, found they overwhelmingly backed subsidies for all-electric vehicles and for public charging stations.

The majority also backed setting a date to ban the import of traditionally-powered cars – a move adopted by many other nations including China, the United Kingdom and France.

Back from Glasgow and out on the campaign trail this week, Morrison is promoting aspects of his net zero by 2050 technology policy. On Monday he was in Newcastle announcing a $1.5 million grant through the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) as part of a study to assess the feasibility of a green hydrogen hub at the Port of Newcastle.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP26: cities create over 70% of energy-related emissions. Here’s what must change

Cities are responsible for 71-76% of energy-related CO₂ emissions. Today, the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow will convene to discuss this urgent global problem.

Carbon emissions in cities are generated through activities including the construction and operation of buildings, manufacture of building materials such as steel and concrete, and through the movement of people, goods and services.

The sector has been described as the “sleeping giant” of carbon emissions. This includes Australia, where a pre-COVID forecast estimated the population will reach 30 million by 2029 – requiring many more buildings to be constructed this decade and beyond.

Over the next 30 years, lifecycle emissions associated with new homes in Australia are expected to exceed the federal government’s economy-wide net-zero emissions targets. Where we locate new buildings and how they’re built is crucial to reducing emissions and managing our exposure to the impacts of climate change.

Australia’s cities are predominantly coastal, but development is underway in areas we know will face sea level rise. Homes and suburbs are not being built to withstand heatwaves and other climate change threats.

We must take significant and rapid action now to ensure cities play their part in limiting dangerous global warming, so they can cope with the climate challenges ahead.

Read more: The Great Australian Dream? New homes in planned estates may not be built to withstand heatwaves

What’s Happening At COP26?

At COP26 today, national, regional, local governments and the private sector will come together to work towards a zero-emission built environment.

A coalition known as #BuildingToCOP26 aims to halve the built environment’s emissions by 2030. Ahead of COP26, it outlined three goals for the sector. They cover targets to decarbonise buildings, committing to the United Nations’ Race to Zero campaign and adopting shared goals for emissions reductions.

Research consistently shows the clear need to act. Yet our study this year found city planning in Victoria does not sufficiently address climate change.

While Australian states have set goals for emission reductions, these are not yet activated through land use planning and development regulations. We found climate change impacts like sea level rise and urban heat were not sufficiently addressed.

Blind spots like these mean the implications of climate change on our built environment – and on property values – are being mispriced and underestimated.

Without significant, rapid change, society will be further exposed to climate risks.

All of us will bear the cost – through higher council rates to pay for infrastructure damage, rising home and contents insurance costs, and in some cases, being refused any insurance at all. This could devalue your property and put your mortgage at risk.

New Zealand recently made it mandatory for big banks, insurers and firms to disclose their climate risk. This leaves Australia increasingly isolated as a climate laggard and exposed to stranded climate assets (when buildings and properties are worthless due to their climate exposure or lack of insurability).

During extreme weather events, fuelled by climate change, there will be impacts to essential services such as water supply, power, and telecommunications.

These will affect all areas of life – schooling, livelihoods, commercial activities, and retirement plans and funding of them – and the damage is likely to be disproportionately felt by society’s most vulnerable.

Through our super funds, many Australians are investing in properties and businesses that may be exposed to a raft of climate risks, jeopardising our future financial security.

Measures to reduce emissions from the built environment should include a focus on design of buildings and suburbs and active transport options for walking and cycling.

More energy-efficient buildings can reduce emissions and help us adapt to higher temperatures.

Read more: The Great Australian Dream? New homes in planned estates may not be built to withstand heatwaves

Barriers To Climate Action In The Sector

Without urgent change, Australia’s 2050 goal of reaching net-zero emissions is at risk. Looking at the new homes required to house Australia’s population to 2050, for example, lifecycle emissions generated in construction and operation obliterates the net-zero target. And that doesn’t even account for emissions from the rest of the building sector.

We must rapidly change how we make and implement decisions around urban planning, property, construction and design. We developed a Built Environment Process Map to help with this task.

It describes the fundamental activities involved in producing the built environment. This can help ensure climate change goals are effectively implemented over a city’s life stages and integrated across sectors and actors.

Our research on the Australian property and construction sectors identified barriers to climate change action. They include:

a lack of clear, trustworthy information for key stakeholders about climate change

a perception among stakeholders that investing in climate change action when it’s not mandatory will threaten their economic competitiveness

a lack of a stable regulatory environment, which hampers investor certainty.

Frontrunners in the Australian property and construction sector are not waiting.

Some property and construction firms and local governments are taking progressively more sophisticated approaches to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

But a lack of government regulation is hampering broad-scale action on climate risks, adaptation and mitigation efforts.

Governments Must Act Now

Existing emissions reduction efforts in the industry now need to be supported and mainstreamed through regulatory change. We also urgently need change in the electricity sector to set us on the path of net-zero emissions.

We can’t afford decisions today that lock in further greenhouse gas emissions.

What happens this week in the COP26 is crucial if we are to work towards a zero-emissions built environment, and achieve the critical goal of limiting warming to 1.5℃ this century.

Anna Hurlimann, Associate Professor in Urban Planning, The University of Melbourne; Georgia Warren-Myers, Senior Lecturer in Property, The University of Melbourne, and Judy Bush, Lecturer in Urban Planning, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Big-business greenwash or a climate saviour? Carbon offsets raise tricky moral questions

Christian Barry, Australian National University and Garrett Cullity, Australian National UniversityMassive protests unfolded in Glasgow outside the United Nations climate summit last week, with some activists denouncing a proposal to expand the use of a controversial climate action measure to meet net-zero targets: carbon offsetting.

Offsetting refers to reducing emissions or removing carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere in one place to balance emissions made in another. So far, more than 130 countries have committed to the net zero by 2050 goal, but none is proposing to be completely emissions free by that date – all are relying on forms of offsetting.

The use of offsets in meeting climate obligations has been rejected by climate activists as a “scam”. Swedish climate campaigner Greta Thunberg, joining the protesters, claimed relying on buying offsets to cut emissions would give polluters “a free pass to keep polluting”.

Others, however, argue offsetting has a legitimate role to play in our transition to a low-carbon future. A recent report by Australia’s Grattan Institute, for example, claimed that done with integrity, carbon offsets will be crucial to reaching net zero in sectors such as agriculture and aviation, for which full elimination of emissions is infeasible.

So who’s in the right? We think the answer depends on the kind of offsetting that is being employed. Some forms of offsetting can be a legitimate way of helping to reach net zero, while others are morally dubious.

Climate Change As A Moral Issue

The debate over offsetting is part of a key agenda item for COP26 – establishing the rules for global carbon trading, known as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. The trading scheme will allow countries to purchase emissions reductions from overseas to count towards their own climate action.

To examine carbon offsetting in a moral context, we should first remember what makes our contributions to CO₂ emissions morally problematic.

The emissions from human activity increase the risks of climate change-related harms such as dangerous weather events – storms, fires, floods, heatwaves, and droughts – and the prevalence of serious diseases and malnutrition.

The more we humans emit, the more we contribute to global warming, and the greater the risks of harm to the most vulnerable people. Climate change is a moral issue because of the question this invites on behalf of those people:

Why are you adding to global warming, when it risks harming us severely?

Not having a good answer to that question is what makes our contribution to climate change seriously wrong.

The Two Ways To Offset Emissions

The moral case in favour of offsetting is it gives us an answer to that question. If we can match our emissions with a corresponding amount of offsetting, then can’t we say we’re making no net addition to global warming, and therefore imposing no risk of harm on anyone?

Well, that depends on what kind of offsetting we’re doing. Offsetting comes in two forms, which are morally quite different.

The first kind of offsetting involves removing CO₂ from the atmosphere. Planting trees or other vegetation is one way of doing this, provided the CO₂ that’s removed does not then re-enter the atmosphere later, for example as a result of deforestation.

Another way would be through the development of negative emissions technologies, which envisage ways to extract CO₂ from the atmosphere and store it permanently.

The second form is offsetting by paying for emissions reduction. This involves ensuring someone else puts less CO₂ into the atmosphere than they otherwise would have. For example, one company might pay another company to reduce its emissions, with the first claiming this reduction as an offset against its own emissions.

Australia’s Clean Energy Regulator issues Australian Carbon Credit Units for “eligible offsets projects”. These include for projects of offsetting by emissions reduction.

The regulator certifies that a company, for example, installing more efficient technology “deliver abatement that is additional to what would occur in the absence of the project”. Another company whose activities send CO₂ into the atmosphere, such as a coal-fired power station, can then buy these credits to offset its emissions.

So What’s The Problem?

There is a crucial difference between these two forms of offsetting. When you offset in the first way – taking as much CO₂ out of the atmosphere as you put in – you can indeed say you’re not adding to global warming.

That’s not to say even this form of offsetting is problem-free. It’s crucial such offsets are properly validated and are part of a transition plan to cleaner energy generation compatible with everyone reaching net zero together. Tree-planting cannot be a complete solution, because we could simply run out of places to plant them.

But when you offset in the second way, you cannot say you’re not adding to global warming at all. What you’re doing is paying someone else not to add to global warming, while adding to it yourself.

The difference between the two forms of offsetting is like the difference between a mining company releasing mercury into the groundwater while simultaneously cleaning the water to restore the mercury concentration to safe levels, and a mining company paying another not to release mercury into the groundwater and then doing so itself.

Read more: We can't stabilise the climate without carbon offsets – so how do we make them work?

The first can be a legitimate way of negating the risk you impose. The second is a way of imposing risk in someone else’s stead.

Let’s use a few simple analogies to illustrate this further. In morality and law, we cannot justify injuring someone by claiming we had previously paid someone who was about to injure that same person not to do so.

The same is true when it comes to the imposition of risk. If I take a high speed joyride through a heavily populated area, I cannot claim I pose no risk on people nearby simply because I had earlier paid my neighbour not to take a joyride along the same route.

Had I not induced my neighbour not to take the joyride, he would’ve had to answer for the risk he imposed. When I do so in his place, I am the one who must answer for that risk.

Read more: Take heart at what’s unfolded at COP26 in Glasgow – the world can still hold global heating to 1.5℃

In our desperate attempt to stop the world warming beyond the internationally agreed limit of 1.5℃, we need to encourage whatever reduces the climate impacts of human activity. If selling carbon credits is an effective way to achieve this, we should do it, creating incentives for emissions reductions as well as emissions removals.

What we cannot do is claim that inducing others to reduce emissions gives us a moral license to emit in their place.![]()

Christian Barry, Professor of Philosophy at the ANU, Australian National University and Garrett Cullity, Professor, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Take heart at what’s unfolded at COP26 in Glasgow – the world can still hold global heating to 1.5℃

Greta Thunberg has already pronounced the COP26 climate conference a failure. In important respects, the Swedish activist is correct.

The commitments made at the conference are insufficient to hold global heating to 1.5℃ this century. Leading producers and users of coal, including Australia, rejected a proposed agreement to end the use of coal in electricity generation by 2030. The Australian government went further and refused to commit to reducing methane emissions – a position endorsed by the Labor opposition.

And the rapid economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic has produced an equally rapid recovery in demand for all forms of energy, resulting in spikes in the prices of coal, oil and gas.

On the other hand, considered over a longer term, the outcomes of the Glasgow conference look rather better.

At the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009, participants agreed to aim at holding global heating below 2℃ this century, but did not deliver policy commitments to achieve this goal. The scenarios considered most plausible at the time yielded estimated heating of around 3℃.

The worst-case scenario, commonly described as “business as usual”, implied a catastrophic increase of up to 6℃ in global temperatures by 2100. As a result of all this, the Copenhagen talks were considered a spectacular failure.

But heading into the final days of the Glasgow summit, the goal of limiting heating below 2℃ looks attainable, and 1.5℃ is still possible. Despite the inevitable disappointments in the decade or so since Copenhagen, there is still room for hope.

1.5℃ To Stay Alive

Ahead of COP26, commitments by each nation had the world on track for 2.7℃ warming this century.

The ten days of the talks so far, however, have yielded new binding commitments. According to one analysis, the commitments put the world on a trajectory to 2.4℃ warming. This assessment is based on current submitted climate pledges by each country, known as nationally determined contributions or NDCs, together with legally binding net-zero commitments.

When we account for additional pledges announced – but not yet formalised – by the G20 countries, the projected temperature rise this century lowers to to 2.1℃, according to analysis by Climate Action Tracker released in September.

So that’s the good news. And of course, those optimistic trajectories assume all pledges are fully implemented.

It has become clear, however, that even 2℃ of global heating would be environmentally disastrous.

Even under the current 1.1℃ of warming since the beginning of large-scale greenhouse gas emissions, Earth has experienced severe impacts such as devastating bushfires, coral bleaching and extreme heatwaves resulting in thousands of human deaths. Such events will only become more frequent and intense as Earth warms further.

This underscores the vital importance of urgently pursuing the 1.5℃ goal. It is, quite literally, a matter of life and death for both vulnerable human populations and for natural ecosystems.

The idea of a target of 1.5℃, supported by many developing countries, was rejected out of hand by major countries at the Copenhagen conference.

The Paris conference in 2015 marked an important, but still partial move towards the 1.5℃ goal. There, nations agreed on a goal to hold global average temperature rise to well below 2℃ above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing efforts to limit the increase to 1.5℃.

We’re yet to see the final communique from Glasgow, and every word in it will doubtless be subject to lengthy negotiation. But it’s almost certain to include a strengthening of the language of the Paris Agreement, hopefully with a formal commitment that warming will be held to 1.5℃.

Reason For Hope

As with previous conferences, policy commitments at Glasgow will be insufficient to reach the 1.5℃ target. Most notably, the commitment to reduce methane emissions is, at this stage, merely an aspiration with no concrete policies attached.

And as analysis released on Tuesday found, real-world action is falling far short despite all the net-zero promises. If that “snail’s pace” continues, a temperature rise of 2.4℃, or even 2.7℃, remains a distinct possibility.

But the technologies and policies needed to hold warming to 1.5℃ are now available to us. And they can be implemented without condemning developing countries to poverty or requiring a reduction in living standards for wealthier countries.

The fact we have these options reflects both remarkable technological progress and the success of policies around the world, including emissions trading schemes and renewable energy mandates.

Thanks largely to government support, advances in solar and wind technology kicked off in the early 2000s. This ultimately pushed the cost of carbon-free electricity below that of new coal-fired and gas-fired plants.

The biggest impact was felt in the European Union, where carbon prices and emissions trading drove a rapid transition. The EU has a clear path to the goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

The most important requirement is to accelerate the transition to carbon-free electricity. This involves rapidly expanding solar and wind energy and replacing petrol- and diesel-powered vehicles with electric alternatives.

These changes would incur a one-off cost in scrapping existing power plants and vehicles before the end of their operational life, but would reduce energy and transport costs in the long run.

Other important steps are already beginning. They include reducing methane emissions, and adopting carbon-free production methods for steel, cement and other industrial products. Hydrogen produced from water by electrolysis will be crucial here.

There is no guarantee these outcomes will be achieved. The leading national emitters – China, India and the United States – have all been inconsistent in their pursuit of stabilising Earth’s climate.

China is currently wavering as economic difficulties mount. In the US, Donald Trump has not ruled out a presidential bid in 2024 which, if successful, would almost certainly reverse progress there.

Global action on climate change is still not nearly enough, but we’re undeniably moving in the right direction. By the time of the next major COP, presumably in 2026, Earth could finally be on a path to a stable climate.

Read more: Scott Morrison is hiding behind future technologies, when we should just deploy what already exists ![]()

John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

COP26: what the draft climate agreement says – and why it’s being criticised

Having led the delegates at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow to believe that the first draft of the final agreement would be published at midnight Tuesday, the UK presidency will not have made many friends by delaying it till 6am Wednesday morning. There will have been plenty of negotiators – not to mention journalists – who will have needlessly waited up all night.

In fact, COP26 president Alok Sharma will not have made many friends with the text itself either. As the host and chair of the summit, it is the UK’s responsibility to pull together all the negotiating texts which have been submitted and agreed over the last week into a coherent overall agreement.

But the widespread consensus among delegates I have spoken to is that the draft they have produced is not sufficiently “balanced” between the interests and positions of the various country groupings. And for the chair of such delicate negotiations, that is a dangerous sin.

Let’s recap. This COP (the conference of the parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) is the designated moment under the 2015 Paris Agreement when countries must come forward with strengthened commitments to act. There are two main areas for this. One is emissions cuts by 2030, the so-called “nationally determined contributions” or NDCs. The other, for the developed countries, is financial assistance to the least developed nations.

The problem facing the COP is that we know already that, when added together, countries’ emissions targets are not nearly enough to keep the world to a maximum warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial times, as the Paris Agreement aims for. And the financial promises don’t even reach the US$100 billion (£74.1 billion) a year that was meant to be achieved in 2020, let alone the much larger sums the most vulnerable countries need.

So what have the poorest countries – and the vociferous civil society organisations demonstrating in Glasgow – been demanding?

First, that NDCs should be strengthened before the scheduled date of 2025. And second, that at least US$500 billion should be provided in climate finance over the five years to 2025, with half of this going to help countries adapt to the climate change they are already experiencing.

Urging – Not Requiring

So what does the UK draft text say? It merely “urges” countries to strengthen their NDCs, proposing a meeting of ministers next year and a leaders’ summit in 2023. But “urges” is UN-speak for: “You may do this if you wish to, but you don’t have to if you don’t.” That is not enough to force countries to get onto a 1.5℃-compatible path. The text must require them to do so.

On finance, the text is even weaker. There is no mention of the US$500 billion demand, although it does call for adaptation funding to be doubled. There is no mention of using the special drawing rights (a kind of global money supply) which the IMF has recently issued for climate-compatible development. And there is insufficient recognition that the most vulnerable countries need much better access to the funds available.

Of course, developing countries do not expect to get all their own way in the negotiations. But commenting on the overall balance of the text between different countries’ positions, one European delegate said to me: “This looks like it could have been written by the Americans.”

It is of course true, as Alok Sharma emphasised in his afternoon press conference, that the text can still be changed. There are several issues on which negotiations are continuing and the text has yet to reflect their progress. Sharma has asked all parties to send in their suggested amendments to the draft and to meet him to discuss their reactions. He will find himself asked for a lot of meetings.

But it matters how this early text is drafted, for two reasons. First, the lack of balance means that it is the least developed countries which will have to do the most work to change it. In Paris the French presidency worked the other way round. They drafted an ambitious text and dared the biggest emitters to oppose it.

Second, the perceived imbalance could affect the trust in the British hosts. Sharma has built himself a strong reputation over the past couple of years preparing for the COP. He will not want to lose that in the crucial last days ahead.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage on COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

Amid a rising tide of climate news and stories, The Conversation is here to clear the air and make sure you get information you can trust. More. ![]()

Michael Jacobs, Professorial Fellow, Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI), University of Sheffield

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Can climate laggards change? Russia, like Australia, first needs to overcome significant domestic resistance

Ellie Martus, Griffith UniversityFormer US president Barack Obama took specific aim at Russia at the Glasgow COP26 climate talks this week. According to Obama, the fact Russian President Vladimir Putin (as well as Chinese President Xi Jinping) declined to attend the conference reflects “a dangerous absence of urgency, a willingness to maintain the status quo” on climate action.

As the world’s fourth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases and one of the world’s top coal, oil, and gas producers and exporters, Russia is a key player in international climate action. Decarbonisation of carbon-intensive economies like Russia is crucial to reaching global emissions targets.

But like Australia, Russia is seen as an international climate laggard, and must overcome significant resistance to genuine climate policy reform at home.

Despite vastly different political systems, we can draw interesting parallels between Russia and Australia on the climate front.

Read more: To reach net zero, we must decarbonise shipping. But two big problems are getting in the way

Russia’s International Participation On Climate

In a surprise announcement two weeks out from COP26, Putin said Russia will aim to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. But his decision not to attend COP26 dealt a blow to the summit’s prospects of success.

Russia has long been a reluctant participant in international climate change negotiations. It refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol until 2004, then failed to sign up for Kyoto’s second commitment period. Similarly, Russia signed the Paris Agreement in 2016, but delayed its final decision on ratification until late 2019.

That’s despite a long tradition of Russian climate science research dating back to the Soviet period.

In the end, ratifying the Paris Agreement was an easy political win, given how weak Russia’s commitments under the agreement are.

Russia’s updated NDC (nationally determined contribution, meaning the action it will take to meet its climate commitments) was submitted in November 2020. It sets an emissions reduction target of 70% relative to 1990 levels by 2030.

The target sounds ambitious but the nation’s economic decline in the 1990s, and subsequent fall in greenhouse gas emissions, means it’s easily achievable. This target also leverages the capacity of Russia’s forests to absorb CO₂, though many scientists dispute the extent of this.

So what explains Russia’s limited commitments to date? The domestic politics surrounding climate change offer clues.

Domestic Climate Politics And Obstacles To Reform

Domestic politics on climate change in Russia are fiercely contested, with key individuals and groups competing for influence. These debates occur mostly at an elite level, with little space given to civil society actors.

Attempts to strengthen domestic climate policy in the past have been met with strong opposition from powerful economic interests.

The coal industry remains one of the most significant obstacles to reform. At a time when a growing number of countries are committed to phasing out coal, Russia is actively seeking to expand its industry. The coal industry has close links with key government ministries, including the powerful ministry for energy. The industry has successfully lobbied for subsidies and state support.

Coal politics in Russia are made more complex by the heavy dependence on coal for employment and heating in certain regions, such as the Kuzbass in Siberia. Attempts to wind down the industry would meet significant opposition from locals and regional elites.

Oil and gas companies are moving ahead with their plans to expand into the Arctic, with a warming climate making the region more accessible. Revenues from oil and gas exports make up a significant portion of Russia’s budget, so its highly unlikely Russia will give this up anytime soon.

Putin’s own position on climate has been ambiguous. He and other members of the elite often portray Russia as a global climate leader and “ecological donor” due to its vast forest resources.

However, Russia’s limited policy commitments to date make such statements little more than symbolic.

Recent Political Shifts

More recently however, we’ve seen some important developments which suggest a shift may be occurring.

A pro-climate lobby is emerging around the ministry for economic development and other government actors. They take a pragmatic view of climate change and acknowledge the economic cost to Russia of doing nothing.

International pressures are also mounting.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (which puts a carbon price on certain imports) has many in the Russian government concerned, given the significant impact anticipated for key Russian exports. Some in government have also questioned the long-term viability of coal given global decarbonisation trends.

Two of Russia’s major state owned corporations, Rosatom and Gazprom, are at the forefront of an attempt to reposition Russia as a renewable energy superpower, centred on the expanding hydrogen and nuclear industries. Both provide Russia with potential to generate significant export revenues.

Support for a more active stance on climate has also come from some of Russia’s largest private companies. Groups such as EN+ and Rusal have made their own net-zero by 2050 commitments, keen to demonstrate their climate credentials to environmentally sensitive international markets.

This newfound momentum has led to a number of important policy developments, culminating in the net-zero by 2060 announcement. So while the obstacles remain huge, there has been a discernible shift in Russia’s approach to climate change.

What Can Australia Learn?

Both Australia and Russia are regarded as climate laggards and face increased international criticism over their lack of policy ambition.

Both have elements of strong resistance to climate action at a domestic level, particularly in the coal industry. But both also have corporate players acting to reduce emissions in spite of government policy inaction.

While much attention has been focused on net zero targets, little detail has been given by either country about how these will be achieved. And neither Russia nor Australia’s net zero commitments say anything about exported emissions.

Ambitious declarations mean nothing if they’re not backed by serious policy reform. Promises aside, significant work needs to be done in both nations to address the gap between vague, high-level commitments and concrete, implementable policies.

Read more: Scott Morrison is hiding behind future technologies, when we should just deploy what already exists ![]()

Ellie Martus, Lecturer in Public Policy, Centre for Governance and Public Policy, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Scott Morrison is hiding behind future technologies, when we should just deploy what already exists

At the United Nations climate summit in Glasgow last week, more than 40 countries pledged to phase out coal-fired power. Some were big coal-using countries such as Poland, Canada and Vietnam – however Australia was not among them. Australia was similarly absent for a methane reduction pledge.

Achieving the Paris Agreement — limiting global warming to well below 2℃ and preferably 1.5℃ — requires the rapid phase out of coal, oil and fossil gas. Failure to do so will spell the end of the Great Barrier Reef and make a large swathe of Australia virtually unlivable.

Yet the Morrison government’s technology-driven net-zero “plan” contains no concrete measures to end this fossil fuel addiction. It’s more a placeholder than a strategy, fulfilling the government’s need to have a document to wave around. Meanwhile, the government seems intent on sitting back and letting the future happen, rather than creating it.

I’ve spent 25 years working and investing in technology commercialisation, focusing over the past 15 years on clean technologies. I know Australia doesn’t need to wait for new technology before committing to and achieving deep emissions cuts. Most technologies we need already exist – they just need to be deployed, rapidly and at massive scale. And that requires an actual plan.

We Have The Technology

The Morrison government’s path to reach net-zero by 2050 relies primarily on technology, but fails to even remotely outline what that would mean in practice.

A total of 70% of the emissions cuts would purportedly be achieved by technology “investment”, “trends” and “breakthroughs”. But it’s not technology per se that reduces emissions, it’s deploying it.

The government missed the opportunity to explain decarbonisation at its simplest: electrify everything we can, and power it with renewables.

Some 84% of Australia’s emissions come from activities related to the energy sector. Recent overseas analysis shows electrification could replace 78% of energy emissions using established technologies. Add technologies being developed, and the figure rises to 99%.